Abstract

Industrial wastewater is one of the most widespread sources of water pollution that cause increasing problems with heavy metals and dyes, which at the same time implies the find of sustainable and cost-effective treatment solutions. The current research was centred on the use of activated sludge that is obtained from the natural wastewater to remove both methylene blue (MB) dye and lead (Pb) ions from contaminated water. The SEM, EDS, FTIR, BET, XRD, and TGA analysis were used to characterize the structure and function of the activated sludge. The effect of pH, contact time, initial concentration, and sludge dosage on the removal efficiency was studied using the batch experiments. The activated sludge was most efficient at pH 6, 120 min contact time with 2 g/L sludge dosage. The steps of adsorption process have been best described by the pseudo-second-order kinetic model, in which physical attachment was found to be the major route. The results of isotherm studies showed that the best fitting model for the adsorption data was the Langmuir model, with the maximum adsorption capacities of 78.6 mg/g for MB and 52.3 mg/g for Pb. The sludge also showed appreciable regeneration, with over 80% of the adsorption capacity left after it had completed the fifth cycle. The findings thus put forward the idea of using naturally occurring activated sludge from wastewater as a sustainable, low-cost, and efficient biosorbent for the treatment of water polluted with dyes and heavy metals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Water pollution from industrial effluents containing synthetic dyes and heavy metals has become a global environmental concern. Industries such as textile, printing, and metal processing are major sources of this pollution, releasing large quantities of contaminated wastewater into aquatic environments1. Synthetic dyes, such as methylene blue (MB), are persistent, toxic, and pose significant risks to both human health and aquatic life2. Likewise, heavy metals like lead (Pb) are non-biodegradable, accumulate in the food chain, and can cause severe ecological and health problems3. Traditional treatment methods like chemical precipitation, ion exchange, and membrane filtration are often costly, energy-intensive, and can produce secondary pollutants4. Consequently, there is a pressing need for sustainable, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly alternatives for water treatment. Previous studies have demonstrated the potential of activated sludge and its modified forms for removing various contaminants. For example, Wang and Wang (2019) reported efficient Pb(II) adsorption on modified biosorbents derived from activated sludge5, while Mohan et al. (2014) found that biochar prepared from agricultural residues exhibited strong affinity for Pb(II) and cationic dyes6. Similarly, Chen et al. (2020) and Zhang et al. (2021) emphasized that optimizing the physicochemical properties of biosorbents can significantly improve dye and metal uptake from industrial effluents10,11. Beyond technical performance considerations, the environmental sustainability of water treatment materials has become a critical factor in adsorbent selection and development. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), emphasize the need for environmentally benign and resource-efficient treatment technologies7. Conventional adsorbents such as activated carbon, while highly effective, require significant energy input for high-temperature activation (700–1000 °C), substantial chemical consumption, and often utilize non-renewable precursor materials, resulting in considerable carbon footprint and environmental impact8. Similarly, synthetic ion-exchange resins and engineered nanomaterials, though effective, involve complex synthesis procedures, hazardous chemicals, and generate problematic waste streams9. In this context, the utilization of naturally occurring waste materials as biosorbents represents a paradigm shift toward circular economy principles, whereby waste streams are valorized into functional materials, reducing both waste disposal burden and the need for energy-intensive adsorbent production10. Natural wetland-derived activated sludge, as a continuously regenerating byproduct of natural wastewater treatment processes, offers unique sustainability advantages including minimal processing requirements, low energy consumption, carbon neutrality, and alignment with nature-based solutions for water management11. Biosorption has emerged as a promising approach for removing contaminants from wastewater due to its low cost, high efficiency, and minimal environmental impact12. This process utilizes biomaterials, such as bacteria, fungi, algae, and agricultural waste, to bind and remove pollutants from aqueous solutions. Extensive research has been conducted on various biosorbents, such as chitosan, sawdust, and peanut hulls, demonstrating their potential for dye and metal sequestration13,14. Activated sludge, a byproduct of biological wastewater treatment processes, has gained attention as a potential biosorbent due to its abundance, renewability, and inherent microbial activity15. The complex structure of activated sludge, consisting of microbial flocs, extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), and various organic and inorganic components, provides numerous binding sites for pollutants16.However, a review of the literature reveals that the majority of studies on sludge-based biosorption have focused specifically on sludge from engineered systems, such as industrial or municipal wastewater treatment plants17,18. While effective, this sludge often requires additional pre-treatment (e.g., chemical activation, thermal modification) or is coupled with energy-intensive aeration processes to enhance its adsorption capacity and stability19. This reliance on processed sludge from artificial systems represents a significant knowledge gap, as it overlooks the potential of sludge formed in natural environments. In contrast, activated sludge derived from natural wastewater systems, such as wetlands or river sediments, offers a novel and underexplored resource for water treatment. These natural systems are rich in diverse microbial communities and organic matter, which can enhance the adsorption capacity and stability of the sludge20. The diverse microbial communities present in natural systems can contribute to the biodegradation of pollutants in addition to bio sorption, offering a synergistic approach for contaminant removal21. Previous studies on natural biofilms and sediments have highlighted their rich microbial diversity and complex matrix of organic matter, which contribute to natural attenuation processes22,23. We hypothesize that these intrinsic properties can enhance the adsorption capacity and stability of natural sludge without the need for energy-intensive modification. Furthermore, the diverse and adapted microbial communities present in these systems can contribute to the biodegradation of pollutants in addition to biosorption, offering a synergistic approach for contaminant removal24. Despite this understanding, the direct application of naturally occurring activated sludge as a primary biosorbent for targeted pollutants like MB and Pb2+ remains largely uninvestigated. Therefore, this study introduces a sustainable method for removing dyes and heavy metals using activated sludge derived directly from natural wastewater systems. Unlike synthetic adsorbents or processed sludge from treatment plants, this eco-friendly biosorbent exploits the intrinsic and evolved properties of natural sludge. The research systematically investigates its efficiency in eliminating methylene blue (MB) and Pb2+ through physicochemical characterization, optimization of adsorption parameters, kinetic and isotherm modeling, and regeneration assessment. The aim is to advance a novel, scalable, and low-cost water treatment technology for mitigating industrial pollution by leveraging an underexplored natural resource.

Experimental

Materials

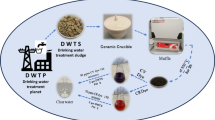

In this study, activated sludge was collected from a natural wastewater treatment facility situated within a wetland area near the Ismailia Canal. To remove impurities, the collected sludge underwent thorough washing with deionized water, followed by drying at 105 °C for 24 h. The dried sludge was then mechanically ground into a fine powder. Methylene blue (MB) dye (C16H18ClN3S, molecular weight 319.85 g/mol, purity ≥ 95%) and lead nitrate (Pb(NO3)2, molecular weight 331.21 g/mol, purity ≥ 99%), both acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (USA), were used as representative contaminants for the dye and heavy metal studies, respectively. All chemicals used were of analytical grade and used without further purification. Deionized water with a resistivity of 18.2 MΩ cm was obtained from a Milli-Q water purification system (Millipore, USA). pH adjustments were made using hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37% purity) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH, ≥ 98% purity), sourced from Merck (Germany).

Sample collection

Activated sludge was collected from a mature wastewater treatment wetland near the Ismailia Canal, Egypt (30° 35′ N, 32° 16′ E). The 15-ha wetland, operating for over 10 years, receives mixed agricultural and domestic wastewater and supports diverse microbial communities. Sampling was performed in October 2024 during the dry season. Ten sampling points were identified, focusing on the central treatment zone showing high microbial activity. Sediment samples were taken from a depth of 15–20 cm using sterilized core samplers. In-situ parameters were recorded: temperature 23.5 °C, pH 7.1–7.4, dissolved oxygen 3.2–3.8 mg/L, and conductivity 1.8–2.2 mS/cm. A 5-kg composite sample was obtained, cleaned of debris (> 5 mm), placed in sterile polypropylene containers, and transported to the laboratory at 4 °C within 4 h.

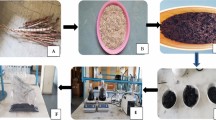

Synthesis

In the laboratory, the sample showed 78.5 ± 2.1% moisture, pH 7.2 ± 0.3, and bulk density 1.15 ± 0.08 g/cm3. After homogenization, coarse impurities were removed, and the sludge was wet-sieved (5 mm). Three washing cycles with deionized water (1:5 w/v, 200 rpm, 30 min) were conducted until the filtrate conductivity fell below 0.20 mS/cm. The washed sludge was vacuum-filtered and oven-dried at 105 °C for 24 h to constant weight (< 2% moisture). The dried material was ground (Retsch PM 100, 350 rpm, 2 h) and sieved to obtain the 75–125 μm fraction (68% yield). Laser diffraction confirmed a mean particle diameter (D₅₀) of 98.6 μm. The biosorbent was stored in amber glass bottles with PTFE-lined caps in a desiccator at 25 °C. Monthly quality checks ensured < 3% moisture and stable pH (± 0.5). Adsorption capacity using 100 mg/L methylene blue remained consistent (± 5%) over 12 months. From 5 kg of wet sludge, 850–950 g of dry biosorbent was obtained (17–19% yield). All experiments were performed using a single batch (AS-NW-2024-10) to ensure reproducibility. The baseline characteristics of the raw sludge are summarized in Table 1.

Batch equilibrium isotherm

A series of batch adsorption experiments were performed to assess the effectiveness of activated sludge in removing MB dye and Pb ions. Stock solutions (1000 mg/L each) of MB and Pb were prepared by dissolving appropriate quantities of MB dye and Pb(NO3)2 in deionized water and then diluted to the required experimental concentrations. The pH of the solutions was adjusted using 0.1 M HCl or 0.1 M NaOH and measured using a Hanna Instruments pH meter (Model pH211). For each experiment, a known quantity of activated sludge (0.5–3 g/L) was added to 100 mL of the prepared contaminant solution in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks. These flasks were then agitated at 150 rpm using a New Brunswick Scientific mechanical shaker (Model Innova 42) at room temperature (25 ± 2 °C) for varying time intervals (30–180 min). Following agitation, the samples were filtered through 0.45 μm membrane filters, and the residual concentrations of MB and Pb in the resulting filtrate were determined using a Shimadzu UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Model UV1800) at wavelengths of 664 nm and 283 nm, respectively. All experiments were conducted in triplicate to ensure accuracy, and the mean values were reported as the final results.

Characterization

Various analytical techniques were employed to comprehensively characterize the physicochemical properties of the natural wetland-derived activated sludge biosorbent. Scanning electron microscopy coupled with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM–EDX, JSM-IT500, JEOL, Japan) was used to examine the surface morphology and elemental composition at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV, working distance of 10 mm, and spot size of 5.0 nm under high vacuum. Samples were dried, mounted on aluminum stubs, and sputter-coated with a ~ 10 nm gold layer using a Q150R ES sputter coater (Quorum Technologies, UK) for 90 s at 30 mA. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Nicolet iS50, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was performed in the range of 4000–400 cm-1 with a 4 cm-1 resolution and 32 scans per sample in ATR mode to identify surface functional groups. Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms were obtained at 77 K using a Micromeritics ASAP 2460 analyzer after degassing at 150 °C for 6 h; surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution were determined using the BET and BJH models. X-ray diffraction (XRD, D8 Advance, Bruker, Germany) was conducted using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) at 40 kV and 40 mA over a 2θ range of 5°–80° with a step size of 0.02° and scan rate of 1°/min to identify crystalline phases. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA, TGA 4000, PerkinElmer, USA) was carried out under a nitrogen atmosphere (40 mL/min) from 25 to 800 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min using 10 ± 0.5 mg of sample to assess thermal stability. These analyses provided detailed insights into the structural, compositional, and thermal properties of the biosorbent.

Results and discussion

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis

The SEM analysis (Fig. 1) revealed that the activated sludge possesses a highly heterogeneous and porous morphology, characterized by irregular flakes, cavities, and a rough surface texture. This complex architecture is structurally advantageous for adsorption, as it provides a high specific surface area and numerous potential binding sites25. The presence of both micropores (< 2 nm) and mesopores (2–50 nm) within the sludge matrix provides abundant active sites for the adsorption of various contaminants, including methylene blue (MB) and lead (Pb2+) ions26. While micropores are well-suited for accommodating smaller molecules, mesopores effectively adsorb larger ones, significantly enhancing the overall adsorption capacity of the sludge27. Furthermore, the non-uniform surface morphology, characterized by cracks and protrusions, increases the available binding sites and facilitates surface interactions, thereby improving adsorption efficiency28. These morphological features work synergistically with the sludge’s chemical composition. The rough, fragmented surface exposes a multitude of functional groups (e.g., carboxyl, hydroxyl, amine), which were identified by FTIR analysis. This combination creates a highly effective adsorbent where the porous structure ensures pollutant access, and the surface chemistry drives strong binding via complexation, electrostatic attraction, and ion exchange29. Therefore, the sludge’s efficacy, as demonstrated by the high adsorption capacities for both MB and Pb2+, is not attributable to a single factor. Instead, it arises from this synergistic interplay: the mesoporous structure ensures optimal transport and access, while the heterogeneous surface and its inherent chemistry provide abundant, high-affinity binding sites for a diverse range of contaminants30. This structure–property relationship underscores the potential of using this minimally processed, natural sludge as a versatile and efficient biosorbent.

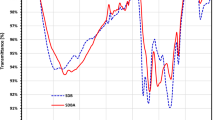

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis

FTIR spectroscopy revealed the presence of crucial functional groups on activated sludge, enhancing its ability to adsorb methylene blue (MB) dye and lead (Pb) ions. As shown in Fig. 2, the FTIR spectrum exhibited significant peaks indicating the presence of hydroxyl (–OH) groups at 3400 cm-1, carboxyl (–COOH) groups at 1650 cm-1, and polysaccharides at 1050 cm-131. This indicates the surface’s potential for forming hydrogen bonds with polar molecules like MB. The peak at ~ 1650 cm-1, attributable to C=O stretching in amide I groups and/or asymmetric stretching in carboxylate anions, is of critical importance1. For the cationic MB dye, this group facilitates strong electrostatic attraction. For Pb2+, it serves as a primary site for complexation, forming stable chelates. The presence of polysaccharides, indicated by the C–O–C/C–O–P stretching band at ~ 1050 cm-1, contributes to the overall anionic character of the biomass and provides additional sites for ion exchange and metal binding32. Furthermore, the peaks at ~ 2920 cm-1 (aliphatic C–H stretching) and ~ 1400 cm-1 (C–N stretching of amine groups) reveal the complex, heterogeneous nature of the biosorbent. The amine groups are particularly significant, as they can be protonated to attract anionic species or participate in complexation with metal ions. Synergistic Adsorption Mechanisms: The coexistence of these diverse functional groups is key to the sludge’s versatility. The simultaneous presence of carboxylate, hydroxyl, and amine groups allows it to effectively adsorb both the cationic MB dye primarily through electrostatic attraction and hydrogen bonding, and the Pb2+ ions through surface complexation and ion exchange. This multifaceted chemical composition, as confirmed by FTIR, directly underpins the robust and multi-mechanistic adsorption performance observed in this study, aligning with findings that highlight surface chemistry as a primary determinant of biosorbent efficacy1,33.

Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area analysis

The specific surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution of the activated sludge were analyzed using nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms and BET analysis, as presented in Fig. 3a, b. The isotherm exhibited a Type IV profile with a distinct hysteresis loop (P/Po: 0.4–0.9), characteristic of mesoporous materials that offer an optimal balance between surface area and pore accessibility34. The activated sludge displayed a BET surface area of 45.6 m2/g, a total pore volume of 0.12 cm3/g, and an average pore diameter of 3.8 nm as determined by BJH analysis, confirming its mesoporous structure27. Such a pore configuration enhances molecular diffusion and minimizes pore blockage, facilitating the adsorption of both small ions (Pb2+) and larger dye molecules (MB)28. Although the measured surface area is relatively low compared with conventional activated carbon (typically 500–3000 m2/g), the activated sludge exhibited competitive adsorption capacities—78.6 mg/g for MB and 52.3 mg/g for Pb2+ (Table 5). This strong adsorption performance can be attributed to the abundance of surface functional groups (carboxyl, hydroxyl, and amine), the favorable mesoporous structure, and biosorption mechanisms arising from residual microbial components. These features promote electrostatic attraction, ion exchange, and complexation, effectively compensating for the lower physical surface area. Similar trends have been reported for other natural and modified biosorbents with moderate surface areas (20–100 m2/g), where surface chemistry plays a more dominant role than total surface area in determining adsorption efficiency. These findings align with previous studies emphasizing the importance of surface functionality and porosity in biosorbent performance, confirming that activated sludge is a promising and sustainable material for water purification applications1.

Crystalline structure analysis

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis of the activated sludge (Fig. 4) revealed the coexistence of both amorphous and crystalline phases. The broad diffraction humps observed in the 2θ range of 15°–30° indicate the presence of amorphous organic matter such as cellulose, lignin, and polysaccharides32. These amorphous constituents play a critical role in adsorption by offering numerous accessible and chemically active sites capable of interacting with pollutant molecules.

In contrast, several sharp peaks were detected, corresponding mainly to crystalline phases of quartz (SiO2) and calcite (CaCO3). These minerals are commonly identified in sludge-derived materials and contribute to the overall structural integrity of the adsorbent. Their presence supports adsorption mechanisms such as ion exchange, surface complexation, and surface precipitation, particularly for heavy metal ions like Pb(II)26.

The predominance of the amorphous phase enhances the availability of functional groups (–OH, –COOH, –NH2), which are essential for the chemisorption of cationic pollutants such as methylene blue (MB) and Pb(II). Meanwhile, the crystalline components provide rigidity and stability, preventing structural collapse during adsorption cycles. This synergistic coexistence of amorphous and crystalline domains thus establishes an optimal balance between adsorption activity and mechanical strength1. These findings are consistent with previous studies reporting that a higher proportion of amorphous material in biosorbents significantly improves adsorption efficiency due to enhanced surface reactivity and pore accessibility28,35. Therefore, the hybrid structural nature of the activated sludge may explain its high performance in removing both organic dyes and heavy metal contaminants.

The thermo gravimetric analysis (TGA)

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of activated sludge (Fig. 5) revealed a three-stage weight loss profile, corresponding to the decomposition of moisture, organic matter, and inorganic fractions. The initial weight loss below 28.64 °C is attributed to the evaporation of physically adsorbed moisture and the release of weakly bound volatile compounds, indicating the presence of hydrophilic surface sites. The second and most significant stage, occurring between 28.64 and 393.43 °C, reflects the thermal degradation of organic constituents such as cellulose, lignin, and proteins, accompanied by the evolution of CO2 and volatile organic compounds. This substantial weight reduction confirms the high organic content of the sludge, providing abundant functional groups (–OH, –COOH, –NH2) that are crucial for adsorption of methylene blue and Pb(II) ions. The third stage, extending from 393.43 to 953 °C, corresponds to the decomposition of inorganic components, including carbonates, sulfates, and metal oxides, with a notable transformation of CaCO3 to CaO. The residual ash (approximately 20–25% at 800 °C) consists mainly of thermally stable inorganic minerals. Overall, the sludge exhibits a balanced composition of organic and inorganic matter, ensuring high adsorption efficiency, structural integrity, and thermal stability suitable for regeneration and reuse. These observations are consistent with previous studies on thermally stable biosorbents33.

Elemental composition of activated sludge for water treatment

Scanning electron microscopy coupled with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM–EDS) was utilized to determine the elemental composition of the activated sludge, providing insights into its adsorptive potential for water purification applications. The analysis revealed a heterogeneous composition comprising both major and minor elements that collectively contribute to the sludge’s adsorption efficiency (Table 2).

Major components

-

Carbon (C): Representing the predominant element (approximately 50–60%), carbon originates mainly from organic materials such as cellulose, lignin, and polysaccharides. It contributes numerous functional groups (–COOH, –OH) that serve as active binding sites, significantly enhancing adsorption capacity.

-

Oxygen (O): Accounting for about 30–35%, oxygen is associated with both organic and inorganic constituents. It plays a key role in adsorption through mechanisms such as hydrogen bonding, surface oxidation, and complexation with contaminants.

-

Nitrogen (N): Present in smaller quantities (5–10%), nitrogen arises from proteins and amino acids, introducing functional groups such as amine (–NH2) and amide (–CONH2) that exhibit strong affinity toward cationic pollutants including methylene blue (MB) and Pb(II) ions.

Minor components

-

Silicon (Si): Primarily existing as silica (SiO2), silicon contributes to the structural stability and rigidity of the sludge matrix while participating in surface adsorption interactions.

-

Calcium (Ca): Present as calcite (CaCO3) or calcium oxide (CaO), calcium enhances ion-exchange and surface precipitation mechanisms, particularly in the removal of heavy metals such as Pb2+.

Trace Elements (Mg, Al, Fe): Although detected in minor concentrations, these elements further support adsorption through mechanisms such as complexation, surface precipitation, and co-adsorption, thereby improving overall removal efficiency.The diverse elemental composition of the activated sludge demonstrates its dual organic–inorganic character, which synergistically enhances adsorption performance. The organic fraction provides abundant reactive sites for contaminant binding, whereas the inorganic minerals ensure structural integrity and contribute to ion exchange and surface complexation. These findings are consistent with previous EDS-based studies on biosorbents35, underscoring the suitability of activated sludge as a sustainable and versatile adsorbent for wastewater treatment.

Batch adsorption study

Effect of pH on adsorption

The pH of the solution significantly influences the adsorption performance of activated sludge toward methylene blue (MB) dye and lead (Pb(II)) ions. To assess this effect, adsorption experiments were conducted at 25.5 °C across a pH range of 2–10, with pH adjustments using 0.1 N NaOH and 0.1 N HCl. The goal was to determine the optimal pH that maximizes contaminant removal efficiency.

As presented in Fig. 6, the adsorption capacity of MB gradually increased from 45.2 mg/g at pH 3 to a maximum of 78.6 mg/g at pH 6, after which a slight decline was observed at higher pH values. Similarly, Pb(II) ions exhibited their highest adsorption capacity of 52.3 mg/g at pH 5. These variations can be attributed to the combined effects of changes in the surface charge of the sludge and the speciation behavior of the contaminants.

At lower pH values, excess hydrogen ions protonate the functional groups (–OH, –COOH, –NH2) on the sludge surface, leading to a net positive charge that repels cationic species such as MB⁺ and Pb2+, resulting in reduced adsorption. As the pH increases, deprotonation occurs, generating negatively charged sites that enhance electrostatic attraction toward these cations, thereby improving adsorption efficiency. Beyond the optimum pH, MB adsorption slightly decreases, possibly due to competition with hydroxide ions or dye aggregation, whereas Pb(II) removal declines due to the formation and precipitation of Pb(OH)2 under alkaline conditions.

Overall, these results indicate that near-neutral pH conditions favor the adsorption of both MB and Pb(II) onto activated sludge. The observed behavior highlights the importance of pH control in optimizing adsorption efficiency and supports previous studies reporting similar pH-dependent trends in biosorbent systems.

Effect of contact time

Figure 7 illustrates the effect of contact time (30–180 min) on the adsorption capacity and removal efficiency of methylene blue (MB) and lead (Pb(II)) ions at varying initial concentrations (50–300 mg/L). The adsorption process exhibited a distinct two-stage kinetic pattern: an initial rapid uptake phase followed by a slower equilibrium phase. The adsorption rate increased sharply within the first 60 min due to the high availability of active binding sites on the sludge surface, facilitating rapid attachment of MB and Pb(II) ions. Thereafter, the rate gradually declined, reaching equilibrium at approximately 120 min, with maximum adsorption capacities of 78.6 mg/g for MB and 52.3 mg/g for Pb(II). The slowing of adsorption beyond the initial stage indicates a transition from surface adsorption to intraparticle diffusion, as contaminants progressively migrate into the internal pores of the sludge. This behavior suggests that both external surface interactions and internal pore diffusion govern the overall adsorption process. The initial stage is dominated by chemisorption and electrostatic attraction, whereas the subsequent stage reflects diffusion-controlled transport within the porous structure. Such dual-stage kinetics are characteristic of heterogeneous biosorbent systems and have been widely reported in previous studies36,37.

Effect of initial concentration

The adsorption performance of activated sludge was strongly influenced by the initial concentration of methylene blue (MB) and lead (Pb(II)) ions. As presented in Fig. 8, the adsorption capacity increased progressively with rising initial concentrations, reaching peak values of 78.6 mg/g for MB at 200 mg/L and 52.3 mg/g for Pb(II) at 150 mg/L. Beyond these concentrations, the adsorption capacity tended to plateau, indicating the progressive saturation of active binding sites on the sludge surface.The initial enhancement in adsorption at higher concentrations is attributed to an increased driving force for mass transfer, which accelerates the diffusion of adsorbate molecules from the bulk solution to the adsorbent surface. However, once the available active sites become occupied, further adsorption is restricted by surface saturation and limited pore accessibility. This behavior suggests that while higher initial concentrations promote rapid surface coverage, the overall adsorption capacity is ultimately constrained by the finite number of reactive sites and the pore structure of the sludge. These findings highlight the importance of optimizing initial contaminant concentrations in wastewater treatment processes to achieve maximum adsorption efficiency without overloading the adsorbent. Similar trends have been reported in studies involving dye and metal ion adsorption on bio sorbents38,39

Effect of sludge dosage

Figure 9 illustrates the effect of sludge concentration on the removal efficiency of methylene blue (MB) and lead (Pb(II)) ions. The adsorption efficiency increased with rising sludge dosage, reaching a maximum at 2 g/L, after which no significant improvement was observed. This enhancement at lower dosages can be attributed to the increased availability of active binding sites, which promotes greater interaction between the contaminants and the sludge surface. Beyond the optimum dosage, however, adsorption capacity plateaued due to the saturation of available sites and possible particle aggregation, which can reduce the effective surface area. The maximum adsorption capacities achieved were 78.6 mg/g for MB and 52.3 mg/g for Pb(II), confirming the high affinity of activated sludge toward both contaminants. These results highlight the importance of optimizing adsorbent dosage to balance removal efficiency with material economy.

Adsorption isotherms

Adsorption isotherms are crucial tools for understanding the interactions between solutes (pollutants) and adsorbents (activated sludge) and for optimizing adsorption capacity in wastewater treatment. In this study, adsorption isotherms were employed to investigate the equilibrium interactions between activated sludge and two pollutants: methylene blue (MB) dye and lead (Pb(II)) ions. The Langmuir and Freundlich models were used to characterize the adsorption behavior, specifically the relationship between the amount of pollutant adsorbed (qe) and its equilibrium concentration in the solution (Ce). These experiments were conducted under pre-determined optimal conditions: pH 5, adsorbent dosage of 2 g/L, and a contact time of 120 min.

Langmuir isotherm

The Langmuir isotherm model posits that adsorption occurs on a limited number of identical sites on the adsorbent surface, forming a monolayer. Once a pollutant molecule occupies a site, further adsorption at that specific location is precluded. This model is frequently employed to describe monolayer adsorption and assumes a homogeneous distribution of adsorption sites across the adsorbent surface. In this investigation, the Langmuir isotherm was utilized to model the adsorption behaviour of Pb(II) ions and MB dye onto activated sludge. The original and linearized forms of the Langmuir adsorption equation are as follows:

Original Form

Linearized Form

where

-

Ce (mg/L) is the equilibrium concentration of the adsorbate.

-

qe (mg/g) is the amount of pollutant adsorbed per unit mass of adsorbent.

-

Qo (mg/g) represents the maximum adsorption capacity.

-

KL (L/mg) is the Langmuir constant, indicating the adsorption energy.

Figure 10 depicts a linear relationship between Ce/qe and Ce, derived from experimental data, which is characteristic of monolayer adsorption as predicted by the Langmuir isotherm model. The Langmuir constants, Qmax (maximum adsorption capacity) and KL (Langmuir constant related to the energy of adsorption), were determined from the slope and intercept of this linear plot, with the results summarized in Table 3. The calculated Qmax values for Pb(II) and MB dye were 52.3 mg/g and 78.6 mg/g, respectively, indicating a strong affinity of the activated sludge for these contaminants. This high adsorption capacity can be attributed to various factors, including electrostatic interactions and complexation processes between the pollutants and the functional groups present on the sludge surface. Furthermore, the comparatively high KL values (0.076 L/mg for Pb(II) and 0.054 L/mg for MB dye) further emphasize the strong tendency of the activated sludge to adsorb these pollutants, even at low concentrations. These findings suggest that activated sludge has significant potential as an effective adsorbent for the removal of these pollutants from aqueous solutions.

Freundlich isotherm

The Freundlich isotherm model describes adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces with varying adsorption energies. Unlike the Langmuir model, which assumes monolayer adsorption on a homogeneous surface, the Freundlich model accounts for multilayer adsorption and interactions between adsorbed molecules.The Freundlich isotherm is represented by the following empirical equation:

In this equation: q e (mg/g) denotes the amount of pollutants adsorbed per unit mass of the adsorbent. C e (mg/L) represents the pollutant’s equilibrium concentration. K f (mg/g)(L/mg)ⁿ is the Freundlich constant, indicating adsorption capacity. n is a dimensionless constant that signifies adsorption intensity. Values ranging from 0.1 < 1/n < 1 indicate favorable adsorption, while 1/n > 1 suggests more challenging absorption, as noted by Treybal40.

The linearized version of the Freundlich equation is expressed as:

In this form, plotting ln(qe) versus ln(Ce) yields a linear relationship, where the slope represents 1/n and the intercept corresponds to ln(Kf). Figure 11 illustrates this linear relationship, demonstrating the influence of surface heterogeneity on adsorption as described by the Freundlich model. The parameter 'n' serves as an indicator of adsorption favorability. In this study, the calculated 'n' values for all pollutants were greater than 1, signifying favorable adsorption conditions. The superior fit of the Freundlich model to the experimental data, as evidenced by higher R2 values, confirms its suitability in describing the multilayer adsorption behaviour on the heterogeneous surface of activated sludge.

Implications and future directions

These findings underscore the efficacy of activated sludge in removing various contaminants, highlighting its potential for practical wastewater treatment applications. Furthermore, the study demonstrates that the Freundlich model provides a more accurate representation of adsorption behavior under the investigated conditions. Future research should delve into the impact of competing ions commonly found in actual wastewater on the adsorption process. Additionally, assessing the long-term stability and performance of activated sludge under operational conditions is crucial for its successful implementation in real-world scenarios. Table 3 presents the equilibrium concentrations of the pollutants measured during the study.

Adsorption kinetic study

This research explored how well activated sludge can remove pollutants like methylene blue (MB) dye and lead (Pb(II)) from water. The study focused on the speed at which these pollutants are absorbed by the sludge. Experiments were conducted under ideal conditions: pH 5, 2 g/L of sludge, and a contact time of 120 min. To understand the adsorption process, two common kinetic models were used: pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order. These models help determine how quickly pollutants are taken up by the sludge, the time required for pollutant accumulation, and the nature of the interactions between the sludge and the pollutants. By analyzing these models, researchers can understand whether the adsorption process primarily involves physical (physisorption) or chemical (chemisorption) interactions. Furthermore, these models help estimate rate constants and assess the overall efficiency of the adsorption process41. Understanding these kinetic models is crucial for gaining a deeper understanding of how pollutants interact with adsorbents. This knowledge is essential for improving water purification techniques and developing more effective adsorbent materials.

Pseudo-first-order kinetic model (PFO)

The Lagergren model, also known as the pseudo-first-order (PFO) kinetic model, is a widely used model to describe the adsorption of solutes by different adsorbents42. This model is based on the principle that the adsorption rate is directly proportional to the difference between the maximum adsorption capacity and the amount of solute adsorbed at a particular time. The Lagergren rate equation mathematically represents this pseudo-first-order kinetic model as follows:

In this context, qt signifies the quantity of adsorbate taken up at a given time t (mg/g), qe represents the adsorption capacity at equilibrium (mg/g), and k1 is the first-order reaction rate constant (min-1). The variable t indicates the duration of interaction (min). This equation demonstrates how adsorption capacity evolves over time, emphasizing the gap between the equilibrium capacity and the current adsorption amount.

The pseudo-first-order (PFO) model is effective in describing adsorption phenomena occurring between solids and liquids. It offers valuable insights into the mechanisms of adsorption and helps identify the rate-limiting step in the process. However, it’s important to acknowledge that the PFO model may not always accurately represent the entire adsorption process, particularly over prolonged periods or when other factors significantly impact the adsorption kinetics. To apply the PFO model, researchers typically plot log(qe–qt) against time to determine the rate constant (k1) and the theoretical equilibrium adsorption capacity (qe). As shown in Fig. 12, this method was used to calculate maximum adsorption capacities for Pb(II) (50.4 mg/g) and MB dye (76.8 mg/g). This approach facilitates a comparison between theoretical predictions and experimental results, allowing researchers to evaluate the model’s suitability for the specific adsorption system being studied, as summarized in Table 4.

The pseudo-second-order kinetic model is a prominent framework for analyzing adsorption, where the adsorption rate is hypothesized to be directly proportional to the square of available unoccupied sites on the adsorbent surface. This model is particularly well-suited for systems dominated by chemical interactions, as its predictions frequently show good agreement with experimental data. Equation 643, presents the linear form of this model.

The pseudo-second-order adsorption rate constant, k2, is measured in g/mg·h. Both k2 and the equilibrium adsorption capacity (qe) can be derived from the slope and intercept of a t/qt versus t graph, as shown in Fig. 13 for pollutant adsorption. By applying the experimental data to pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order models, parameters including k1, k2, qe, and the coefficient of determination (R2) are obtained. These results, presented in Table 4, enable a thorough evaluation of the kinetic models’ ability to describe the adsorption process.

The pseudo-second-order model demonstrated a superior fit to the experimental data, as evidenced by higher R2 values compared to the pseudo-first-order model. This suggests that the adsorption rate is primarily influenced by the availability of active sites on the adsorbent surface, rather than solely by the pollutant concentration in the solution. Notably, the calculated k2 values exhibited a significant increase in the adsorption rate with rising pollutant concentrations, consistent with the characteristics of chemical adsorption. Furthermore, the close agreement between the calculated and experimental qe values for the pseudo-second-order model further reinforces the efficacy of activated sludge in pollutant adsorption.

The composite material effectively and rapidly removes contaminants from water, showcasing its potential for water treatment applications. Notably, the observed maximum adsorption capacities of 52.3 mg/g for Pb(II) and 78.6 mg/g for MB dye further underscore its suitability for environmental remediation.

Reusability results

The reusability of the activated sludge was evaluated through five consecutive adsorption cycles (Fig. 14) to assess its potential for practical applications. After each cycle, the sludge was regenerated by washing with 0.1 M HCl for Pb ions and deionized water for MB dye, followed by drying at 105 °C for 24 h. The adsorption capacity was measured for each cycle. For MB dye, a slight decrease was observed (from 78.6 to 63.2 mg/g), retaining approximately 80.4% of its initial capacity. Similarly, for Pb ions, the capacity decreased from 52.3 to 41.8 mg/g, retaining about 79.9%. This minor reduction is likely attributed to partial loss of active sites or incomplete contaminant desorption during regeneration. These results demonstrate the excellent reusability and stability of the activated sludge, making it a promising material for repeated use in water treatment applications.

Adsorption mechanisms of methylene blue and lead ions by activated sludge

The removal of methylene blue (MB) dye and lead (Pb) ions by activated sludge involves a combination of physical and chemical interactions.

-

Electrostatic interactions: The negatively charged surface of the sludge at pH 6 attracts positively charged MB dye molecules and Pb2+ ions. This attraction is driven by electrostatic forces between the ions and negatively charged functional groups like carboxyl (COOH) and hydroxyl (OH) on the sludge surface44.

-

Ion exchange: Pb2+ ions can be exchanged with other cations like Ca2+ and Mg2+ present on the sludge surface. This is supported by increased concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ in the solution after adsorption45.

-

Complex formation: Functional groups on the sludge surface, such as COOH, OH, and NH2, can form chemical complexes with both MB dye and Pb ions. For MB, this involves interactions between the dye’s nitrogen atoms and these functional groups. For Pb, stable complexes form with COOH and OH groups46.

-

Physical adherence: The porous structure of activated sludge allows for physical adsorption of both pollutants. This includes van der Waals forces and pore filling. Isothermal adsorption studies and SEM/BET analysis confirm the role of physical adsorption 47.

Comparison with previous work

The observed adsorption mechanisms (electrostatic interactions, ion exchange, complexation, and physical adsorption) align with previous research utilizing activated sludge and other biosorbents for water treatment. Table 5 provides a comparative analysis of adsorption capacities for Pb(II) and MB dye across various adsorbents, demonstrating the competitive performance of the natural wastewater-derived activated sludge in this study. This performance advantage is attributed to its unique composition and structure, surpassing the capacities of many chemically modified or synthetic adsorbents. In conclusion, these findings underscore the multifaceted nature of the adsorption process and confirm the potential of natural activated sludge as an effective and sustainable biosorbent for water treatment applications.

Environmental sustainability assessment of natural wetland-derived activated sludge

A comprehensive environmental sustainability evaluation was performed to assess the viability of natural wetland-derived activated sludge as a biosorbent compared with conventional adsorbents.

Raw material sustainability

Activated sludge from treatment wetlands is a renewable and continuously regenerating resource formed by natural biological processes, with typical accumulation rates of 0.5–2.0 cm yr⁻121. Unlike mineral- or crop-based precursors, it requires no land cultivation and does not compete with food or fiber production59. Its utilization converts a waste management challenge into a value-added product, fully aligning with circular economy principles60. Responsible harvesting (15–20 cm depth) minimizes ecological disturbance and can even enhance wetland performance by preventing excessive sediment buildup61.

Energy and carbon footprint

Preparation of the biosorbent involves only washing, drying (105 °C), and grinding, consuming 4–6 MJ kg-1—about 80–85% less energy than activated carbon (25–41 MJ kg-1) 62,63. This results in a carbon footprint of 0.6–0.8 kg CO2-eq kg-1, compared to 3.5–5.7 kg CO2-eq kg-1 for activated carbon64. Moderate drying conditions allow solar-assisted drying, reducing energy use by up to 90%65,66. As its carbon is biogenic, the biosorbent is effectively carbon–neutral upon degradation67.

Chemical and water requirements

Only deionized water is used for washing, eliminating the need for corrosive activating agents and preventing hazardous waste generation typical of chemical adsorbents68,69. Water consumption (~ 70 L kg-1 product) can be minimized through wash-water recycling and use of treated wastewater, ensuring both water efficiency and environmental safety70,71.

Ecological and land-use impact

The use of wetland-derived activated sludge as a biosorbent requires no additional land, as the feedstock originates from existing treatment wetlands72. Controlled and periodic sludge harvesting not only supplies raw material but also sustains wetland functionality by preventing clogging, improving hydraulic flow, and enhancing oxygen transfer73. Managed removal (15–20 cm depth) restores nutrient balance, supports microbial regeneration, and prolongs wetland efficiency without disturbing vegetation or aquatic habitats74,75.When conducted during low-flow periods, the process minimizes ecological disruption and promotes ecosystem resilience. Furthermore, end-of-life biosorbent can be returned to the soil or used for composting, contributing to nutrient cycling and organic matter recovery76. This integrated approach combines pollution mitigation with wetland maintenance, aligning with circular economy and nature-based solutions for sustainable environmental management.

Circular economy and end-of-life

This process exemplifies circular economy principles by converting wetland sludge, a wastewater byproduct, into a reusable biosorbent with minimal waste generation77. The material retains over 80% of its adsorption efficiency after five regeneration cycles, reducing environmental impact per use78. Spent biosorbent can be repurposed for soil amendment, composting, or energy recovery through pyrolysis, contributing to nutrient recycling and offsetting the need for chemical fertilizers79. The regeneration process is simple, low-cost, and environmentally benign, aligning with sustainable waste management and closed-loop production systems.

Socioeconomic benefits

The low-cost and low-energy preparation (US$ 50–150 ton-1) supports decentralized production near wetlands, creating local employment and reducing dependence on imported adsorbents80. This accessible technology is particularly advantageous for developing regions, offering affordable and sustainable water treatment solutions81. By combining economic feasibility, community benefits, and environmental stewardship, wetland-derived biosorbents represent a scalable and socially responsible innovation for circular water management systems.

Quantitative sustainability metrics and comparative analysis

To enable a rigorous evaluation of environmental performance, Table 6 presents key sustainability indicators comparing the activated sludge biosorbent with conventional adsorbents such as activated carbon and synthetic resins. The results reveal that natural wetland-derived activated sludge exhibits substantial advantages across multiple sustainability dimensions—including energy consumption, carbon footprint, and waste valorization potential. The biosorbent’s production requires minimal external energy inputs, generates negligible greenhouse gas emissions, and utilizes naturally abundant, renewable biomass. These attributes collectively demonstrate its promise as a truly green and circular alternative for water treatment applications.

Limitations and areas for improvement

While the sustainability profile is highly favorable, several challenges and improvement opportunities should be acknowledged:

-

1.

Variability of Raw Material:

The physicochemical composition of natural sludge varies with wetland type, season, and local environmental conditions. This variability necessitates quality control measures and standardization protocols to ensure consistent adsorption performance.

-

2.

Contaminant Pre-screening:

Sludge collected from wetlands impacted by industrial discharges may contain elevated levels of heavy metals or organic pollutants, requiring comprehensive contaminant assessment and pre-treatment prior to use.

-

3.

Scale-up Challenges:

Transitioning from laboratory-scale to full-scale implementation demands optimized collection, transportation, and processing systems, ensuring efficiency and economic viability.

Optimization opportunities

Further research could enhance sustainability by exploring:

-

1.

Solar-assisted drying to fully eliminate fossil energy inputs

-

2.

Closed-loop water recycling systems to minimize freshwater use

-

3.

Integrated harvesting with wetland maintenance to reduce operational costs

-

4.

Regional biosorbent production networks to improve logistics and reduce emissions

Despite these considerations, the overall environmental and economic sustainability of wetland-derived activated sludge remains exceptionally strong. Its low energy demand, waste valorization nature, and renewable origin position it as a viable, scalable, and environmentally responsible alternative to conventional adsorbents in wastewater treatment applications worldwide.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that natural wetland-derived activated sludge is a highly efficient, sustainable, and economically viable biosorbent for the removal of methylene blue (MB) dye and lead (Pb2+) ions from aqueous solutions. The biosorbent exhibited remarkable adsorption capacities of 78.6 mg/g for MB and 52.3 mg/g for Pb2+, attributed to its well-developed porosity, large surface area, and abundance of active functional groups. Adsorption behavior followed the pseudo-second-order kinetic model and the Langmuir isotherm, indicating that chemisorption and monolayer adsorption were the dominant mechanisms, primarily governed by electrostatic attraction, ion exchange, and surface complexation. The biosorbent retained over 80% of its adsorption efficiency after five regeneration cycles, confirming its excellent stability and reusability. Moreover, the preparation process requires 80–85% less energy and emits 75–85% less CO2 than commercial activated carbon, while generating no hazardous waste, requiring no additional land, and maintaining low production costs (US$ 50–150 per ton).By utilizing a renewable and naturally regenerating waste resource, this approach exemplifies circular economy principles and directly contributes to the achievement of UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs 6, 12, and 13). Overall, natural wetland-derived activated sludge presents a scalable, low-cost, and environmentally benign alternative for sustainable wastewater treatment applications.

Data availability

All data underlying the results are available as part of the article and no additional source date are required.

References

Crini, G. Non-conventional low-cost adsorbents for dye removal: A review. Biores. Technol. 97(9), 1061–1085 (2006).

Holkar, C. R. et al. A critical review on textile wastewater treatments: Possible approaches. J. Environ. Manage. 182, 351–366 (2016).

Abbas, S. H. et al. Biosorption of heavy metals: A review. J. Chem. Sci. Technol. 3(4), 74–102 (2014).

Fu, F. & Wang, Q. Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewaters: A review. J. Environ. Manage. 92(3), 407–418 (2011).

Wang, M.-H.S., Shammas, N.K., & Wang, L.K. Advances in removal of heavy metals from contaminated soil. In Control of heavy metals in the environment, 433–491. (CRC Press, 2025).

Sen, T. K. J. M. Agricultural solid wastes based adsorbent materials in the remediation of heavy metal ions from water and wastewater by adsorption: A review. Molecules 28(14), 5575 (2023).

Lee, B. X. et al. Transforming our world: Implementing the 2030 agenda through sustainable development goal indicators. J. Public Health Policy 37(Suppl 1), 13–31 (2016).

Ioannidou, O. & Zabaniotou, A. Agricultural residues as precursors for activated carbon production—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 11(9), 1966–2005 (2007).

Fu, F. & Wang, Q. Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewaters: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 92(3), 407–418 (2011).

Ghisellini, P., Cialani, C. & Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 114, 11–32 (2016).

Vymazal, J. J. W. Constructed wetlands for wastewater treatment. Water 2(3), 530–549 (2010).

Volesky, B. Biosorption process simulation tools. Hydrometallurgy 71(1–2), 179–190 (2003).

Gupta, V. K. Application of low-cost adsorbents for dye removal–a review. J. Environ. Manag. 90(8), 2313–2342 (2009).

Witek-Krowiak, A., Szafran, R. G. & Modelski, S. J. D. Biosorption of heavy metals from aqueous solutions onto peanut shell as a low-cost biosorbent. Desalination 265(1–3), 126–134 (2011).

Kanamarlapudi, S., Chintalpudi, V. K. & Muddada, S. Application of biosorption for removal of heavy metals from wastewater. Biosorption 18(69), 70–116 (2018).

Ateer, M. C., & Gerard, P. Linking microbial community structure and function to process performance and reactor configuration during high-rate low-temperature anaerobic treatment of dairy wastewater. In Diss. School of Natural Sciences, College of Science, National University of Ireland, Galway (2018).

Crini, G. Non-conventional low-cost adsorbents for dye removal: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 97(9), 1061–1085 (2006).

Azimi, A. et al. Removal of heavy metals from industrial wastewaters: A review. Chem. Bio Eng. Rev. 4(1), 37–59 (2017).

Ayangbenro, A. S. & Babalola, O. O. A new strategy for heavy metal polluted environments: A review of microbial biosorbents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14(1), 94 (2017).

Hammer, D. A. Constructed Wetlands for Wastewater Treatment 702–709 (Lewis Publishers, 1989).

Kadlec, R. H. & Wallace, S. Treatment Wetlands (CRC Press, 2008).

Flemming, H. C. & Wingender, J. The biofilm matrix. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8(9), 623–633 (2010).

Battin, T. J. et al. Microbial landscapes: New paths to biofilm research. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5(1), 76–81 (2007).

Singh, R., Paul, D. & Jain, R. K. Biofilms: implications in bioremediation. Trends Microbiol. 14(9), 389–397 (2006).

Goldstein, J. I. et al. Scanning Electron Microscopy and X-Ray Microanalysis 65–91 (Springer, 2017).

Rathi, B. S. et al. Recent research progress on modified activated carbon from biomass for the treatment of wastewater: A critical review. Environ. Quality Manag. 33(4), 907–928 (2024).

Rouquerol, J. et al. Adsorption by Powders and Porous Solids: Principles, Methodology and Applications (Academic Press, 2013).

Foo, K. Y. & Hameed, B. H. Insights into the modeling of adsorption isotherm systems. Chem. Eng. J. 156(1), 2–10 (2010).

Sun, X.-F. et al. Enhancement of acidic dye biosorption capacity on poly (ethylenimine) grafted anaerobic granular sludge. J. Hazard. Mater. 189(1–2), 27–33 (2011).

Choi, W. S. & Lee, H. J. Nanostructured materials for water purification: Adsorption of heavy metal ions and organic dyes. Polymers 14(11), 2183 (2022).

Silverstein, R. M. & Bassler, G. C. Spectrometric identification of organic compounds. J. Chem. Educ. 39(11), 546 (1962).

Li, W.-M. et al. New insights into filamentous sludge bulking: The potential role of extracellular polymeric substances in sludge bulking in the activated sludge process. Chemosphere 248, 126012 (2020).

Wang, F. et al. A luminous quasar at redshift 7642. Astrophys. J. Lett. 907(1), L1 (2021).

Thommes, M. et al. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 87, 1051 (2015).

Ramrakhiani, L., Ghosh, S. & Majumdar, S. Surface modification of naturally available biomass for enhancement of heavy metal removal efficiency, upscaling prospects, and management aspects of spent biosorbents: a review. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 180(1), 41–78 (2016).

Sabzehmeidani, M. M. et al. Carbon based materials: A review of adsorbents for inorganic and organic compounds. Mater. Adv. 2(2), 598–627 (2021).

Ho, Y. S. & McKay, G. Pseudo-second order model for sorption processes. Process Biochem. 34(5), 451–465 (1999).

Almeida-Naranjo, C.E., et al., Transforming waste into solutions: Raw and modified bioadsorbents for emerging contaminant removal. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 13(1) (2025).

Ahmad, R. & Kumar, R. Adsorptive removal of congo red dye from aqueous solution using bael shell carbon. Appl. Surface Sci. 257(5), 1628–1633 (2010).

Treybal, R. E. Mass transfer operations. N. Y. 466, 493–497 (1980).

Lima, E. C. et al. Is one performing the treatment data of adsorption kinetics correctly. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9(2), 104813 (2021).

Yuh-Shan, H. Citation review of Lagergren kinetic rate equation on adsorption reactions. Scientometrics 59(1), 171–177 (2004).

Ho, Y.-S. Review of second-order models for adsorption systems. J. Hazard. Mater. 136(3), 681–689 (2006).

Shahib, I. I. et al. Influences of chemical treatment on sludge derived biochar; physicochemical properties and potential sorption mechanisms of lead (II) and methylene blue. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10(3), 107725 (2022).

Lu, H. et al. Relative distribution of Pb2+ sorption mechanisms by sludge-derived biochar. Water Res. 46(3), 854–862 (2012).

Fan, X. et al. Efficient capture of lead ion and methylene blue by functionalized biomass carbon-based adsorbent for wastewater treatment. Ind. Crops Prod. 183, 114966 (2022).

Sari, A. A. et al. Mechanism, adsorption kinetics and applications of carbonaceous adsorbents derived from black liquor sludge. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 77, 236–243 (2017).

Yu, X., Lee, K. & Ulrich, A. C. Model naphthenic acids removal by microalgae and Base Mine Lake cap water microbial inoculum. Chemosphere 234, 796–805 (2019).

Hu, R. et al. Chemical characteristics and sources of water-soluble organic aerosol in southwest suburb of Beijing. J. Environ. Sci. 95, 99–110 (2020).

Parameshwar, K., & Samal, H.B. Nano carrier-mediated ocular therapeutic delivery: A comprehensive review. Current Nanomed. (2024).

Esmaeili, E. et al. Modified single-phase hematite nanoparticles via a facile approach for large-scale synthesis. Chem. Eng. J. 170(1), 278–285 (2011).

El-Arish, N. et al. Adsorption of Pb (II) from aqueous solution using alkaline-treated natural zeolite: Process optimization analysis. Total Environ. Res. Themes 3, 100015 (2022).

Rinaudo, M. Chitin and chitosan: Properties and applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 31(7), 603–632 (2006).

Verma, M. et al. Adsorptive removal of Pb (II) ions from aqueous solution using CuO nanoparticles synthesized by sputtering method. J. Mol. Liq. 225, 936–944 (2017).

Kgabi, D. P. & Ambushe, A. A. Removal of Pb (II) ions from aqueous solutions using natural and HDTMA-modified bentonite and kaolin clays. Heliyon 10(18), e38136 (2024).

Wang, F. A novel magnetic activated carbon produced via hydrochloric acid pickling water activation for methylene blue removal. J. Porous Mater. 25(2), 611–619 (2018).

Mohan, D. et al. Organic and inorganic contaminants removal from water with biochar, a renewable, low cost and sustainable adsorbent–A critical review. Biores. Technol. 160, 191–202 (2014).

Jadaa, W. Wastewater treatment utilizing industrial waste fly ash as a low-cost adsorbent for heavy metal removal: Literature review. Clean Technol. 6(1), 221–279 (2024).

Spiertz, J. H. J. & Ewert, F. Crop production and resource use to meet the growing demand for food, feed and fuel: Opportunities and constraints. NJAS-Wagening. J. Life Sci. 56(4), 281–300 (2009).

Fytili, D. & Zabaniotou, A. Utilization of sewage sludge in EU application of old and new methods—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 12(1), 116–140 (2008).

Garcia, J. et al. Contaminant removal processes in subsurface-flow constructed wetlands: A review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40(7), 561–661 (2010).

Sardar, R. I. et al. Review on production of activated carbon from agricultural biomass waste. Int. J. Renew. Energy Commer. 7(2), 26–37 (2021).

Arena, N., Lee, J. & Clift, R. Life Cycle Assessment of activated carbon production from coconut shells. J. Clean. Prod. 125, 68–77 (2016).

Hammond, G. P. & Jones, C. I. Embodied energy and carbon in construction materials. Proc. Inst. Civil Eng. Energy 161(2), 87–98 (2008).

Ekechukwu, O. V. Review of solar-energy drying systems I: An overview of drying principles and theory. Energy Convers. Manag. 40(6), 593–613 (1999).

El-Sebaii, A., Shalaby, S. J. R. & Reviews, S. E. Solar drying of agricultural products: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 16(1), 37–43 (2012).

Lehmann, J., & Joseph, S. Biochar for environmental management: an introduction. In Biochar for Environmental Management, 1–13. (Routledge, 2015).

Onigemo, M. T. et al. Production and characterization of activated carbon from coconut shell for adsorption of lead (II) ion from waste water. Adv. J. Chem. B: Nat. Prod. Med. Chem 6, 269–283 (2024).

Tan, I. A. W., Ahmad, A. L. & Hameed, B. H. Adsorption of basic dye on high-surface-area activated carbon prepared from coconut husk: Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. J. Hazard. Mater. 154(1–3), 337–346 (2008).

Shannon, M. A. et al. Science and technology for water purification in the coming decades. Nature 452(7185), 301–310 (2008).

Wang, S. & Peng, Y. Natural zeolites as effective adsorbents in water and wastewater treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 156(1), 11–24 (2010).

Bhatnagar, A. & Sillanpää, M. Utilization of agro-industrial and municipal waste materials as potential adsorbents for water treatment—A review. Chem. Eng. J. 157(2–3), 277–296 (2010).

Langergraber, G. et al. Recent developments in numerical modelling of subsurface flow constructed wetlands. Sci. Total Environ. 407(13), 3931–3943 (2009).

Reddy, K. R., DeLaune, R. D. & Inglett, P. W. Biogeochemistry of Wetlands: Science and Applications (CRC Press, 2022).

Vymazal, J. Removal of nutrients in various types of constructed wetlands. Sci. Total Environ. 380(1–3), 48–65 (2007).

Jain, H. & Dhupper, R. Holistic strategies for sustainable buildings and their impacts on soil and environmental health. J. Build. Pathol. Rehabil. 11(1), 10 (2026).

Saralegui, A.B., et al., Lignocellulosic waste as adsorbent for water pollutants a step towards sustainability and circular economy. In Bioremediation of Toxic Metal (loid) s, 168–182. (CRC Press, 2022).

El Messaoudi, N. et al. Regeneration and reusability of non-conventional low-cost adsorbents to remove dyes from wastewaters in multiple consecutive adsorption–desorption cycles: A review. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 14(11), 11739–11756 (2024).

Ahmed, M. et al. Innovative processes and technologies for nutrient recovery from wastes: A comprehensive review. Sustainability 11(18), 4938 (2019).

Sha, C. et al. A review of strategies and technologies for sustainable decentralized wastewater treatment. Water 16(20), 3003 (2024).

Schäfer, A. I. et al. Renewable energy powered membrane technology: A leapfrog approach to rural water treatment in developing countries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 40, 542–556 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R155), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia and the authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through the Large Research Project under grant number RGP2/298/46.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R155), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, and the authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through the Large Research Project under grant number RGP2/298/46.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.F.,M.A.S., D.N.B., H.I.E., O.H.A., H.S.A. and M.F.M., contributed to the rewriting and discussion of the results. Reviewed and revised the manuscript. Conceived and designed the research study and H.S.A made writing-review and editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fayad, E., Shuheil, M.A., Nasser Binjawhar, D. et al. Activated sludge recovered from wastewater provides a sustainable approach for removing dyes and heavy metals from effluents. Sci Rep 15, 43225 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30904-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30904-7