Abstract

Isolated, confined and extreme environments like Antarctic overwinterings present significant challenges to human psychophysiological adaptation. While previous evidence suggests that such conditions affect autonomic response, the extent to which human physiology adapts, in particular, the sleep-wake cycle and circadian rhythms, remains unclear. To assess the impact of prolonged isolation and the polar night on autonomic nervous system activity, we conducted an observational and longitudinal study at Belgrano II Argentine Antarctic station over a year-long campaign. Heart rate variability, a measure of cardiac autonomic modulation, was computed in 13 crewmembers over 24-hour periods every two months. Analysis revealed a decrease in parasympathetic regulation during wakefulness and an increase during sleep, in association with the increasing duration of isolation. At the same time, parasympathetic activity during sleep decreased during the polar night, suggesting a distinct seasonal effect. These findings offer novel insights into how isolation and the polar night influence autonomic regulation. Understanding these physiological adaptations is crucial for developing effective countermeasures to mitigate stress-related health issues in extreme environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antarctic overwinterings pose significant challenges for human psychophysiological adaptation1,2,3. The unique combination of isolation, confinement, and extreme (ICE) conditions4 has shown to significantly influence sleep and circadian rhythms5,6,7, hormonal responses8, mood9,10, and behavioral patterns11. Due to these characteristics, Antarctica is regarded as a space analogue, where some of the variables experienced during space flight can be ecologically studied12,13,14.

A primary concern in studying physiological adaptation is understanding autonomic regulation in extreme environments like Antarctic overwinterings. Evidence from annual campaigns indicates that prolonged isolation influences both physiological markers15 and subjective reports of stress16. Confinement has been associated with a progressive increase in the stress response17,18, while the absence of natural light during winter has been linked to sleep disturbances and heightened psychosocial strain19,20,21. Together, these conditions have been shown to modulate neuroendocrine15 and autonomic22 responses, highlighting the impact of Antarctic overwinterings on autonomic regulation.

Heart rate variability (HRV), a measure of cardiac autonomic modulation, has been proposed as a reliable tool to quantify the physiological and neurobehavioral effects of human adaptation to various stressors, such as those encountered during Antarctic overwintering23. However, few studies have investigated the adaptation of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) through HRV parameters in Antarctica, revealing distinct changes in sympathetic and parasympathetic activity across different timeframes16,24,25,26,27.

Short stays do not appear to significantly alter autonomic responses during diurnal assessments24,25. When day-night differences are compared during a summer campaign through brief five-minute recordings, an autonomic disparity appears, characterized by a reduced sympathetic response and a predominance of parasympathetic activity at night compared to daytime26. Another summer campaign, albeit only with nightly data, shows an altered ultradian rhythm of autonomic regulation throughout the night, corresponding to the alterations of sleep architecture28. In year-long missions, ten-minutes recordings show higher RR intervals in the middle of the campaign29 while continuous 24-hour HRV monitoring evidences a vagal predominance during summer with a modest association with depressive symptoms27. In summary, research either relies on short recording intervals, it does not distinguish between day and night differences, or focuses on brief stays in Antarctica during summer campaigns. To the best of our knowledge, no 24-hour investigation has analyzed autonomic differences between sleep and wake states or autonomic circadian rhythm during a full-year Antarctic campaign. Our previous study demonstrates reduced sleep duration during the polar night30, which confirms the consensus of available literature regarding sleep during Antarctic overwinterings7. It remains unclear how these conditions affect HRV. The reciprocal relationship between sleep architecture and autonomic regulation warrants investigating both wake and sleep autonomic tone to shed new light on this persistent maladaptive outcome.

In this context, the Belgrano II Argentine Antarctic station, one of the closest stations to the South Pole (at sea level and 77°S) with year-long campaigns under extreme isolation, provides a unique setting for studying human physiological adaptation to extreme environmental conditions. This study aims to explore this adaptation by assessing 24-hour ECG recordings, to examine changes in both sleep-wake HRV differences and circadian HRV rhythm during an Antarctic overwintering at Belgrano II. Our main hypothesis is that reduced natural light exposure will lead to a decrease in parasympathetic tone, along with a progressive decline associated with prolonged confinement.

Results

HRV and sleep-wake cycle

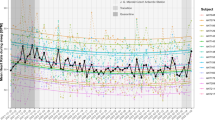

Figure 1 shows the temporal variations in sleep-wake HRV indices, while Tables 1 and 2 present the linear mixed models’ results that account for these changes. These models reveal a significant interaction effect of the isolation (linear term), and the sleep-wake period, in RRM, SDNN, RMSSD, VLF, HF and LF. During the wake period, these variables exhibit a significant linear decreasing trend, while during the sleep period, the trend is reversed, except for SDNN, which is non-significant. Only HFnu shows a significant decreasing linear effect independent of the sleep-wake cycle (Fig. 1). Overall, these findings indicate that parasympathetic tone decreases during wakefulness and increases during sleep in parallel with the duration of isolation.

Sleep-wake HRV throughout one year of Antarctic isolation. Shown are observed means with 95% confidence intervals (vertical bars); lines connect the means across time. The curves show the model-predicted trends based on the linear mixed models (LMMs), with shaded areas representing 95% confidence intervals. The orange color shows the wake period, whereas dark blue represents the sleep period. RRM, average duration of RR intervals in milliseconds; SDNN, standard deviation of RR intervals in milliseconds; RMSSD, root mean square of successive RR interval differences; VLF, very low-frequency component; LF, low-frequency component; HF, high-frequency component; HFnu, normalized units of HF; LH, HF/LF ratio.

Additionally, the models also evidence a significant interaction of the polar night (quadratic term) and the sleep-wake period, in RRM, SDNN, RMSSD, HF, HFnu, and LH. During wakefulness, only SDNN changes exhibit a significant trend, with a minimum observed in July. During sleep, RRM, RMSSD, VLF, HF, HFNU, and LH changes are significant. RRM reaches its minimum in September and its maximum in November. RMSSD, VLF, HF, and HFNU reach their lowest values in July, while LH peaked during the same month (Fig. 1). Overall, results show that during sleep, HRV variables associated with parasympathetic activity decrease during the polar night.

Circadian Rhythm of HRV

Figure 2 shows the temporal variations in circadian rhythm HRV indices, while Table 3 presents the models’ results that account for these changes. The results indicate a linear increasing trend in the amplitude of RRM, SDNN, RMSSD, LF, HF and LH with increasing time spent in isolation (significant linear term). RRM, SDNN, LF, and HF also show a decrease in the amplitude of the circadian rhythm during the polar night (significant quadratic term) (Fig. 2).

Amplitude of the circadian HRV rhythm throughout one year of Antarctic isolation. Shown are observed means with 95% confidence intervals (vertical bars); lines connect the means across time. The curves show the model-predicted trends based on the linear mixed models (LMMs), with shaded areas representing 95% confidence intervals. ‘Amp’ stands for the amplitude of the cosinor curve fitted to each HRV variable. RRM, average duration of RR intervals in milliseconds; SDNN, standard deviation of RR intervals in milliseconds; RMSSD, root mean square of successive RR interval differences; VLF, very low-frequency component; LF, low-frequency component; HF, high-frequency component; HFnu, normalized units of HF; LH, HF/LF ratio.

On the one hand, the positive linear trend observed in almost all variables can be attributed to the temporal patterns of sleep-wake HRV differences described above, which are more pronounced at the end of confinement compared to the beginning, reflecting a progressive increase in the amplitude of parasympathetic circadian rhythm (Fig. 1). The concurrent linear increasing trends in the amplitude of the circadian rhythm for RRM, SDNN, RMSSD, LF, and HF (parasympathetic activity) and LH (typically associated with sympathetic activity) may seem contradictory. However, this is not the case, as by the end of confinement, even though all variables show increased sleep–wake differences, RRM, SDNN, RMSSD, LF, and HF exhibit higher values during the night, while LH show higher values during the day (Fig. 1).

On the other hand, the decrease in the amplitude of the circadian rhythm of HRV variables that reflect parasympathetic activity (Fig. 2), aligns with the decrease in sleep (but not wake) parasympathetic activity during the polar night (Fig. 1).

Finally, neither the Mesor nor the Acrophase showed significant variations throughout the campaign (See Supplementary Table 4).

Discussion

Antarctica´s extreme conditions including extreme photoperiod, confinement and isolation activate a human adaptive response15. While advances in equipment and technology ensure survival in this environment, the main question regarding human adaptation is the extent to which human physiology adjusts its balance to meet the demands of such extremes. In this context, this study aimed to examine human autonomic regulation through HRV variations throughout one year of an Antarctic campaign. Our results showed a decrease in parasympathetic tone during wakefulness and an increase during sleep in parallel with the duration of isolation, with a concurrent decrease in sleep parasympathetic activity during the polar night. In line with this, there was an increase in the amplitude of the parasympathetic circadian rhythm as isolation progressed, along with a decrease in its amplitude during the polar night.

Regarding the impact of isolation, the decreasing prevalence of parasympathetic activity during the day over the course of the mission highlights the influence of confined conditions on human autonomic regulation. Previous research has demonstrated that the lack of novelty and the sensory and social monotony can lead to multiple cognitive and emotional consequences13,21,31. Furthermore, the absence of clear boundaries between work and leisure, combined with constant interaction with the same individuals may amplify minor daily job-related or personal events, resulting in negative social dynamics32,33,34,35. Along the same line, our previous work evidenced a decline in psychological coping throughout the expedition, and a progressive reduction in social support, which was positively correlated to the ability to recover from stress36. Interestingly, a recent study showed that social support is related to the stress levels reported by crewmembers37. Additionally, prolonged separation from family and friends, combined with the psychological anticipation of the mission’s conclusion, likely increases anxiety and amplifies stress responses21. These changes may not always show clinical significance38, as seen in previous studies30,35,36.

During sleep periods, however, parasympathetic influence increased as the mission progressed. This observation can be explained by several factors. Firstly, the autonomic nervous system may attempt to offset daytime stress by promoting restorative parasympathetic activity during sleep39. Elevated sympathetic activation during wakefulness could result in a compensatory rebound effect at night, facilitating recovery. In this regard, decreased heart rate during sleep has been previously reported in summer campaigns in Antarctica22. Secondly, sleep is crucial for emotional and physical recovery from stress. For instance, studies in mice have shown that stressful conditions increase both non-REM and REM sleep, underscoring the role of sleep in restoring homeostasis40,41,42,43. Finally, privacy deprivation is a major challenge in ICE environments44 so the role of sleep can be crucial in providing a natural boundary against external demands and stress. During the night, participants may have more sense of personal control over the environment, feeling less crowded45. The need to restore personal resources after a stressful day can be met through quality sleep and moments of solitude away from the group46,47. Consequently, sleep may serve as both a physical and emotional “privacy space”, acting as a retreat where individuals can recover from workplace stress and interpersonal conflicts.

With respect to the effects of the polar night, we observed that it was associated with a decreased parasympathetic prevalence, consistent with previous findings on its effects on sleep7,30 and mood10,48. Changes in nocturnal HRV can be interpretated in light of sleep architecture variations reported during Antarctic winter7. Previous research at sea- level stations, has shown a reduction in slow-wave sleep (SWS)49,50, likely reflecting a partial disruption of restorative processes. Since SWS is the stage most strongly associated with parasympathetic dominance and cardiovascular recovery, a decrease in its proportion could directly influence HRV profile. In this context, daytime napping could potentially play a compensatory role51, contributing to the restoration of sleep need and supporting parasympathetic regulation, although this remains to be investigated in detail. In line with this idea, our previous work has shown that participants used daytime naps to offset reduced nocturnal sleep during polar night30.

Our previous research has also demonstrated a delay in chronotype and an increase in social jetlag during the same period, associated with the length of the daylight at Belgrano II throughout a year6. The polar night presents two main challenges for human physiology: lack of exposure to natural light and the need to remain indoors due to harsh weather conditions. Light is a primary synchronizer of the central circadian clock52, and its disruption can impact both sympathetic and parasympathetic pathways, which play a crucial role in the synchronization of peripheral clocks and the stress response53. Light exposure has been demonstrated to influence heart rate54 and circadian rhythms55,56.

In addition to its role as a synchronizer, light has been linked to various mood disorders57,58. The absence of natural light appears to affect the dopaminergic and serotoninergic systems, promoting negative changes in mood59,60, which in turn may affect parasympathetic activity61,62. A well-known example, particularly relevant at extreme latitudes, is seasonal affective disorder (SAD), which is characterized by depressed mood, irritability, anxiety, and social withdrawal63. Although mood changes were not seen in this expedition, subclinical forms may also occur, also associated with changes in HRV38,64,65. Our previous research has reported a deterioration in social dynamics during the final period of the mission36, not specifically linked to the polar night. However, we can hypothesize that the psychological alterations mentioned above may also influence social interactions among crewmembers during this period, impacting partially on autonomic regulation.

Furthermore, it is well established that light is not the only factor responsible for synchronizing the master clock. Other variables, such as social routines, can also act as zeitgebers66,67. One study during an Antarctic summer even evidenced a decoupling of melatonin secretion, responding to constant daylight; and cortisol secretion, responding to the social schedule28. Remaining inside the station without a less clear differentiation between work and free time, weakens social cues that help regulate circadian rhythms6, which may also modulate the vagal response68.

Finally, the observed changes in the amplitude of HRV circadian rhythm, suggested its modulation by both the isolation and the polar night. These results go in line and support those discussed previously. On the one hand, the influence of the isolation was reflected on a higher amplitude of parasympathetic HRV circadian rhythm toward the end of the year. This variation is likely related to the increased parasympathetic predominance during sleep and its decline during wakefulness over the course of the campaign. As noted, this increase may be associated with an increased (though subclinical) stress response, that reflects in HRV measurements68,69. In this regard, it is important to note that, in the circadian rhythm literature, a greater amplitude is generally interpreted as a more robust rhythm70, which could suggest some degree of adaptation. However, considering our earlier interpretation of increased daytime stress and nighttime restoration, we view the increased amplitude not as an adaptive consolidation of circadian rhythmicity, but rather as an exaggerated separation between sleep and wake autonomic profiles, likely reflecting underlying stress-related compensation. On the other hand, the decreased amplitude of HRV circadian rhythm during the polar night indicates a deterioration of the circadian regulation29, confirming the idea that the absence of natural light impacts negatively on the strength of the rhythms64. These results are consistent with those reported by Steinach et al. (2016), who observed both linear and quadratic patterns in sleep parameters as a consequence of the combined effects of increasing overwintering time and local sunshine radiation on circadian rhythms71, a pattern also evident at Belgrano II station during polar night6,30.

Our study presents some limitations. Due to logistical constraints inherent to Antarctic expeditions, pre- and post-deployment measurements could not be obtained, which would have provided valuable insights into individual baseline variations and changes after the expedition. Additionally, only male participants were included, which limits the generalizability of our findings to female crew members.

In conclusion, our study of 24-hour HRV over the course of a one-year campaign at Belgrano II Argentine Antarctic Station is the first to reveal distinct patterns of parasympathetic variations, which we attribute to the extreme conditions of isolation and light deprivation. Our findings provide the first evidence of sleep-wake cycle variations in HRV evaluated through 24-hour recordings during an overwintering period. Future studies should compare the effects of photoperiod variations across other Antarctic stations, ideally offering the opportunity to include female participants. Identifying changes in autonomic activity due to extreme conditions can enhance our understanding of the mechanisms underlying the stress response in health and disease and, in turn, contribute to the development of countermeasures for Antarctic overwinterings and other prolonged exposures to isolation and confinement.

Materials and methods

Participants and design

This observational longitudinal study analyzed HRV data from 13 male military personnel who participated in an overwinter campaign at the Argentine Antarctic station Belgrano II (77° 51′ S, 34° 33′ W). Participants had a mean age of 34 ± 1 years and a mean body mass index (BMI) of 26 ± 1 kg/m². The crew of the station comprised 18 men, including the 13 Argentine army personnel that participated in our study, two members of the National Weather Service, and three scientists of the Argentine Antarctic Institute. All participants were healthy, according to the medical and psychological examinations performed before their selection as crewmembers30.

Located about 1300 km from the South Pole, Belgrano II Argentine Antarctic station is the third southernmost permanent station of the planet. Due to its location, it experiences an extreme photoperiod that consists of four months of constant daylight (polar day) and four months of constant darkness (polar night). The natural sunlight period (daylight + civil twilight) duration on the 15th day of each month was: March, 17:32 h; May, 00:00 h; July, 00:00 h; September, 14:01 h; and November, 24:00 h. Isolation and confinement are defining characteristics, communications beyond the station are limited to internet and satellite phone. In emergencies, assistance from another Antarctic station can take at least three days to arrive.

Activities were organized on a weekly basis, in which each crew member must follow a structured routine with specific responsibilities assigned depending on their expertise. A regular workday consisted of a 9:00 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. schedule with a 90-minute break in the afternoon. During the winter, the light–dark cycle is regulated by artificial lighting. Most areas, except for the medical room, have illumination levels below 500 lx30. Measurements were collected every other month from March to November (March, May, July, September and November).

Crewmembers remained physically healthy throughout the year. Mental health was also preserved during the campaign, as indicated by scores on the Spanish validated versions of the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II)72and the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)73, administered at each measurement point30.

Measurements

HRV

Electrocardiogram signal was continuously recorded (225 Hz) using a digital Holter device (Holtech, Servicios Computados S.A., Argentina) for 24 h every other month on measurement points. Ventricular depolarizations (R waves) were identified using the device’s software. The intervals between R waves (RR intervals) were subsequently calculated. HRV indices were determined for 30-minutes segments. An automated filter was used to detect premature and missing beats, which were then replaced with RR intervals obtained through linear interpolation74.

HRV Time Domain measures assess heart rate variation over time. Among these indicators, RRM (average duration of RR intervals in milliseconds) reflects the mean RR interval; SDNN (standard deviation of RR intervals in milliseconds) offers a broad assessment of overall variability; and RMSSD (root mean square of successive RR interval differences) evaluates short-term heart rate fluctuations, related to parasympathetic activity.

Frequency Domain measurements assess the power of different frequency components contributing to HRV. The high-frequency (HF) component (0.15–0.4 Hz) relates to respiratory sinus arrhythmia and is modulated by parasympathetic activity, while the low-frequency (LF) component (0.04–0.15 Hz) is linked to baroreflex regulation, involving both sympathetic and parasympathetic influences. A very low-frequency (VLF) component (< 0.04 Hz), of uncertain origin, has been associated with thermoregulatory changes in vasomotor tone and humoral factors like the renin-angiotensin system, with the dependence on the presence of parasympathetic outflow75,76.

To analyze HRV frequency components, the discrete wavelet transform (DWT) was preferred over the traditional fast Fourier transform due to its robustness against discontinuities and non-stationarities. Before applying the DWT, the signal’s linear trend and mean value were removed. The signal was then evenly sampled at a 2.4 Hz frequency through a spline interpolation algorithm and zero-padded to the next power of two. A six-level wavelet decomposition was conducted with a Daubechies four-wavelet function. In this setup, levels A6 and D1–D6 represented the total power (TP, 0–0.6 Hz), with levels A6 and D6 approximating the VLF band (0–0.0375 Hz), levels D4–D5 corresponding to the LF band (0.0375–0.15 Hz), and levels D2–D3 corresponding to the HF band (0.15–0.6 Hz). In DWT, the square of the standard deviation of wavelet coefficients at each level aligns with the spectral power of that level. Results are reported as the natural logarithm of TP, HF, LF, and VLF; normalized units of HF [HFNU: HF/(TP – VLF) × 100]; and the LF/HF ratio (LH)77,78.

HRV variables, assessed in 30-minutes windows, were averaged over the wake (typically between 06:30 and 22:30) and sleep periods (typically between 23:00 and 06:30)30,78. The sleep-wake periods were determined by actigraphy, as described below. Data corresponding to diurnal sleep periods (between 06:30 and 22:30) were excluded from the analysis.

HRV circadian rhythm was also studied. For each HRV index, a cosinor curve was fitted to 24-hour data, from which three principal variables were derived: Mesor (the mean value of the fitted curve), Amplitude (difference between the curve’s peak and the average baseline), and Acrophase (timing of the curve’s maximum value)78,79.

Sleep-wake cycle

Participants were asked to wear a wrist accelerometer (MicroMini Motionloggers Actigraphs, Ambulatory Monitoring Inc., Ardsley, NY, USA) during seven days on their non-dominant wrist every other month on measurement points. Sleep-wake cycle was analyzed using the software provided by the manufacturer (Action-W User’s Guide, Version 2.4; Ambulatory Monitoring, Inc., Ardsley, NY, USA)30,80. Additionally, participants completed sleep logs specifying nighttime and daytime sleep which served as a control measure for the actigraphy.

Statistical analyses

To explore changes in sleep-wake HRV differences over time, linear mixed-effects models (LMMs) were applied, with each participant´s 30-minute HRV indexes considered as the outcome. A second-degree polynomial predictor was included to account for the effects of isolation and polar night. Isolation was represented by the linear term, reflecting time spent in isolation (linear component: Time), while Polar Night was represented by the quadratic term, capturing the U-shaped variation in natural light exposure over time (quadratic component: Time²). The sleep-wake cycle was introduced as an interaction term with both the linear and quadratic components of time. To account for individual differences, a random intercept for subjects was included. Estimated marginal trends for both linear and quadratic time components were reported for each sleep-wake condition.

Linear mixed-effects models were also used to explore changes in circadian HRV rhythm, with the Mesor, Amplitude and Acrophase of each HRV index as the outcomes. Acrophases were linearized before performing statistical analyses, since their distribution did not cover the whole range of 360 degrees. As in the previous analyses, Isolation was introduced as a second-degree polynomial predictor to account for time spent in isolation (linear component: Time), while Polar Night was included to account for changes in photoperiod (quadratic component: Time2.

Estimates and standard errors reported for each model were calculated using raw polynomial terms to enhance interpretability of the linear and quadratic effects. Corresponding p-values were derived using orthogonal polynomial terms to reduce multicollinearity and improve the reliability of significance testing. The two model variations were identical in structure, differing only in the specification of the polynomial terms. To assess the models’ adequacy, residuals were visually examined. For the variables RMSSD, LH and HFnu the variance of the residuals was observed to increase with the fitted values, indicating heteroscedasticity. As a result, an exponential variance structure was incorporated into the model to account for this relationship.

Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

All analyses and plots were performed in RStudio. Mixed-effects models were fitted using the ‘lme’ package81, and cosinor analysis was conducted with the ‘cosinor2’ package82. Data visualization was performed using the ‘ggplot2’ package83.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee from Universidad Nacional de Quilmes (Argentina) and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments. Participants were informed about the nature and purpose of the study and then invited to participate in the study. All the participants provided written informed consent.

Data availability

The anonymized datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Palinkas, L. A., Johnson, J. C., Boster, J. S. & Houseal, M. Longitudinal studies of behavior and performance during a winter at the South pole. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 69, 73–77 (1998).

Palinkas, L. A. et al. Environmental influences on hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid function and behavior in Antarctica. Physiol. Behav. 92, 790–799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.06.008 (2007).

Spinelli, E. & Werner Junior, J. Human adaptative behavior to Antarctic conditions: A review of physiological aspects. WIREs Mech. Dis. 14, e1556. https://doi.org/10.1002/wsbm.1556 (2022).

Van Ombergen, A., Rossiter, A. & Ngo-Anh, T. J. White Mars’ - nearly two decades of biomedical research at the Antarctic Concordia station. Exp. Physiol. 106, 6–17. https://doi.org/10.1113/EP088352 (2021).

Arendt, J. & Middleton, B. Human seasonal and circadian studies in Antarctica (Halley, 75 degrees S). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 258, 250–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2017.05.010 (2018).

Tortello, C. et al. Chronotype delay and sleep disturbances shaped by the Antarctic Polar night. Sci. Rep. 13, 15957. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-43102-0 (2023).

Pattyn, N., Van Puyvelde, M., Fernandez-Tellez, H., Roelands, B. & Mairesse, O. From the midnight sun to the longest night: sleep in Antarctica. Sleep. Med. Rev. 37, 159–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2017.03.001 (2018).

Diak, D. M. et al. Palmer Station, antarctica: A ground-based spaceflight analog suitable for validation of biomedical countermeasures for deep space missions. Life Sci. Space Res. (Amst). 40, 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lssr.2023.08.001 (2024).

Palinkas, L. A. & Houseal, M. Stages of change in mood and behavior during a winter in Antarctica. Environ. Behav. 32, 128–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/00139160021972469 (2000).

Kang, J. M. et al. Mood and sleep status and mental disorders during prolonged Winter-Over residence in two Korean Antarctic stations. Nat. Sci. Sleep. 14, 1387–1396. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S370659 (2022).

Tortello, C. et al. Subjective time Estimation in antarctica: the impact of extreme environments and isolation on a time production task. Neurosci. Lett. 725, 134893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2020.134893 (2020).

Lugg, D. & Shepanek, M. Space analogue studies in Antarctica. Acta Astronaut. 44, 693–699. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0094-5765(99)00068-5 (1999).

Suedfeld, P. & Weiss, K. Antarctica natural laboratory and space analogue for psychological research. Environ. Behav. 32, 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/00139160021972405 (2000).

Tortello, C. B., Cuiuli, M., Golombek, J. M., Vigo, D. A. & Plano, D. E. Psychological adaptation to extreme environments: Antarctica as a space analogue. Psychol. Behav. Sci. Int. J. 4 https://doi.org/10.19080/PBSIJ.2018.09.555768 (2018).

Strewe, C. et al. Sex differences in stress and immune responses during confinement in Antarctica. Biol. Sex. Differ. 10, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13293-019-0231-0 (2019).

Le Roy, B. M. K., Rabineau, C., Jacob, J., Dupin, S. & Trousselard, C. The right stuff: salutogenic and pathogenic responses over a year in Antarctica author links open overlay panel. Acta Astronaut. 219, 220–235 (2024).

Al-Shargie, F. et al. Detection of astronaut’s stress levels during 240-Day confinement using EEG signals and machine Learning(). Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2023, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/EMBC40787.2023.10340035 (2023).

Jacubowski, A. et al. The impact of long-term confinement and exercise on central and peripheral stress markers. Physiol. Behav. 152, 106–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.09.017 (2015).

Chen, N., Wu, Q., Li, H., Zhang, T. & Xu, C. Different adaptations of Chinese winter-over expeditioners during prolonged Antarctic and sub-Antarctic residence. Int. J. Biometeorol. 60, 737–747. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-015-1069-8 (2016).

Leon, G. R. S. & Larsen, G. M. Human performance in Polar environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 31, 353–360 (2011).

Palinkas, L. A. & Suedfeld, P. Psychological effects of Polar expeditions. Lancet 371, 153–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61056-3 (2008).

Rackova, L. et al. Physiological evidence of stress reduction during a summer Antarctic expedition with a significant influence of previous experience and Vigor. Sci. Rep. 14, 3981. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-54203-9 (2024).

Maggioni, M. A. et al. Reduced vagal modulations of heart rate during overwintering in Antarctica. Sci. Rep. 10, 21810. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-78722-3 (2020).

Çotuk, H. B. D. (ed Ş., D.) Monitoring autonomic and central nervous system activity by permutation entropy during short sojourn in Antarctica. Entropy 21 893 https://doi.org/10.3390/e21090893 (2019).

Moraes, M. M. et al. Hormonal, autonomic cardiac and mood States changes during an Antarctic expedition: from ship travel to camping in snow Island. Physiol. Behav. 224, 113069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2020.113069 (2020).

Farrace, S. et al. Reduced sympathetic outflow and adrenal secretory activity during a 40-day stay in the Antarctic. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 49, 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-8760(03)00074-6 (2003).

Liu, S. et al. Vagal predominance correlates with mood state changes of winter-over expeditioners during prolonged Antarctic residence. PLoS One. 19, e0298751. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0298751 (2024).

Pattyn, N. et al. Sleep during an Antarctic summer expedition: new light on Polar insomnia. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985). 122, 788–794. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00606.2016 (2017).

Dijk, D. J. et al. Amplitude reduction and phase shifts of melatonin, cortisol and other circadian rhythms after a gradual advance of sleep and light exposure in humans. PLoS One. 7, e30037. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0030037 (2012).

Folgueira, A. et al. Sleep, napping and alertness during an overwintering mission at Belgrano II Argentine Antarctic station. Sci. Rep. 9, 10875. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-46900-7 (2019).

Pattyn, N. C. & Manzey, S. D. Mental performance in extreme environments (space and Antarctica): findings and countermeasures. Handbook Mental Performance 296–315 (2024).

Driskell, T. S. & Driskell, E. Teams in extreme environments: alterations in team development and teamwork. Hum. Resource Manage. Rev. 28, 434–449 (2018).

Golden, S. J. C. & Kozlowski, C. H. Teams in isolated, confined, and extreme (ICE) environments: review and integration. J. Organizational Behav. 39, 701–715 (2018).

Somaraju, A. V., Griffin, D. J., Olenick, J., Chang, C. D. & Kozlowski, S. W. J. The dynamic nature of interpersonal conflict and psychological strain in extreme work settings. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 27, 53–73. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000290 (2022).

Van Puyvelde, M. et al. Living on the edge: how to prepare for it? Front. Neuroergon. 3, 1007774. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnrgo.2022.1007774 (2022).

Tortello, C. et al. Coping with Antarctic demands: psychological implications of isolation and confinement. Stress Health. 37, 431–441. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.3006 (2021).

Bell, S. T., Anderson, S. R., Roma, P. G., Landon, L. B. & Dev, S. I. Social support from different sources and its relationship with stress in spaceflight analog environments. Front. Psychol. 15, 1350630. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1350630 (2024).

Palinkas, L. A., Houseal, M. & Rosenthal, N. E. Subsyndromal seasonal affective disorder in Antarctica. J. Nerv. Ment Dis. 184, 530–534. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199609000-00003 (1996).

Joubert, M. et al. Stress Reactivity, wellbeing and functioning in university students: A role for autonomic activity during sleep. Stress Health. 40, e3509. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.3509 (2024).

Palma, B. D., Suchecki, D. & Tufik, S. Differential effects of acute cold and footshock on the sleep of rats. Brain Res. 861, 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02024-2 (2000).

Meerlo, P., Pragt, B. J. & Daan, S. Social stress induces high intensity sleep in rats. Neurosci. Lett. 225, 41–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00180-8 (1997).

Meerlo, P., de Bruin, E. A., Strijkstra, A. M. & Daan, S. A social conflict increases EEG slow-wave activity during subsequent sleep. Physiol. Behav. 73, 331–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0031-9384(01)00451-6 (2001).

Kinn, A. M. et al. A double exposure to social defeat induces sub-chronic effects on sleep and open field behaviour in rats. Physiol. Behav. 95, 553–561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.07.031 (2008).

Palinkas, L. A. & Suedfeld, P. Psychosocial issues in isolated and confined extreme environments. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 126, 413–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.03.032 (2021).

Raybeck, D. Proxemics and privacy: managing the problems of life in confined environments. Springer-Verlag (1987).

Nirwan, M. Human psychophysiology in Antarctica. Sri Ramachandra J. Health Sci. 2, 12–18 (2022).

Harrison, A. A., Clearwater, Y. A. & McKay, C. P. The human experience in antarctica: applications to life in space. Behav. Sci. 34, 253–271. https://doi.org/10.1002/bs.3830340403 (1989).

Sandal, G. M., van deVijver, F. J. R. & Smith, N. Psychological hibernation in Antarctica. Front. Psychol. 9, 2235. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02235 (2018).

Paterson, R. A. & Letter Seasonal reduction of slow-wave sleep at an Antarctic coastal station. Lancet 1, 468–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(75)91552-4 (1975).

Bhattacharyya, M., Pal, M. S., Sharma, Y. K. & Majumdar, D. Changes in sleep patterns during prolonged stays in Antarctica. Int. J. Biometeorol. 52, 869–879. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-008-0183-2 (2008).

Faraut, B. et al. Napping reverses the salivary interleukin-6 and urinary norepinephrine changes induced by sleep restriction. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 100, E416–426. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2014-2566 (2015).

Czeisler, C. A. W., Turek, K. P. & Zee, F. W. Influence of light on circadian rhythmicity in humans. Lung Biology Health Dis.. 133, 149–149 (1999).

Schurhoff, N. & Toborek, M. Circadian rhythms in the blood-brain barrier: impact on neurological disorders and stress responses. Mol. Brain. 16, 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13041-023-00997-0 (2023).

Scheer, F. A., Van Doornen, L. J. & Buijs, R. M. Light and diurnal cycle affect autonomic cardiac balance in human; possible role for the biological clock. Auton. Neurosci. 110, 44–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2003.03.001 (2004).

Dijk, D. J. & Lockley, S. W. Integration of human sleep-wake regulation and circadian rhythmicity. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985). 92, 852–862. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00924.2001 (2002).

Zeitzer, J. M., Dijk, D. J., Kronauer, R., Brown, E. & Czeisler, C. Sensitivity of the human circadian pacemaker to nocturnal light: melatonin phase resetting and suppression. J. Physiol. 526 Pt 3, 695–702. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00695.x (2000).

Dollish, H. K., Tsyglakova, M. & McClung, C. A. Circadian rhythms and mood disorders: time to see the light. Neuron 112, 25–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2023.09.023 (2024).

Siraji, M. A., Spitschan, M., Kalavally, V. & Haque, S. Light exposure behaviors predict mood, memory and sleep quality. Sci. Rep. 13, 12425. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-39636-y (2023).

Bedrosian, T. A. & Nelson, R. J. Timing of light exposure affects mood and brain circuits. Transl Psychiatry. 7, e1017. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2016.262 (2017).

Cawley, E. I. et al. Dopamine and light: dissecting effects on mood and motivational States in women with subsyndromal seasonal affective disorder. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 38, 388–397. https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.120181 (2013).

Tan, Y. et al. Heart rate variability in subthreshold depression and major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 373, 306–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2025.01.003 (2025).

Vigo, D. E., Siri, N. & Cardinali, D. P. L. C.Springer Nature, in Psychiatry and neuroscience update: from translational research to a humanistic approach : Volumen III. Vol. III (eds P. A. Gargiulo & H. L. Mesones Arroyo) 113–126 (2019).

Melrose, S. Seasonal Affective Disorder: An Overview of Assessment and Treatment Approaches. Depress Res. Treat 178564. (2015). https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/178564

Arendt, J. Biological rhythms during residence in Polar regions. Chronobiol Int. 29, 379–394. https://doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2012.668997 (2012).

Ruggiero, V., Dell’Acqua, C., Cremonese, E., Giraldo, M. & Patron, E. Under the surface: low cardiac vagal tone and poor interoception in young adults with subclinical depressive symptoms. J. Affect. Disord.. 375, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2025.01.057 (2025).

Roenneberg, T. et al. Epidemiology of the human circadian clock. Sleep. Med. Rev. 11, 429–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2007.07.005 (2007).

Ujma, P. P., Horvath, C. G. & Bodizs, R. Daily rhythms, light exposure and social jetlag correlate with demographic characteristics and health in a nationally representative survey. Sci. Rep. 13, 12287. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-39011-x (2023).

Deng, S. et al. Correlation of circadian rhythms of heart rate variability indices with Stress, Mood, and sleep status in female medical workers with night shifts. Nat. Sci. Sleep. 14, 1769–1781. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S377762 (2022).

Tonhajzerova, I., Mestanikova, M. M. & Jurko, A. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia as a non-invasive index of ‘brain-heart’ interaction in stress. Indian J. Med. Res. 144, 815–822. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1447_14 (2016).

Leloup, J. C. & Goldbeter, A. Modeling the circadian clock: from molecular mechanism to physiological disorders. Bioessays 30, 590–600. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.20762 (2008).

Steinach, M. et al. Sleep quality changes during overwintering at the German Antarctic stations neumayer II and III: the gender factor. PLoS One. 11, e0150099. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150099 (2016).

Brenlla, M. E. R. C. M. Manual de inventario de Depresión de Beck BDI II. Adaptación Argentina. Editorial Paidos, 11–37 (2006).

Magan, I., Sanz, J. & Garcia-Vera, M. P. Psychometric properties of a Spanish version of the Beck anxiety inventory (BAI) in general population. Span. J. Psychol. 11, 626–640 (2008).

Camm, A. et al. Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Task force of the European society of cardiology and the North American society of pacing and electrophysiology. Circulation 93, 1043–1065 (1996).

Seely, A. J. & Macklem, P. T. Complex systems and the technology of variability analysis. Crit. Care. 8, R367–384. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc2948 (2004).

Vigo, D. E., Siri, N., Cardinali, D. & L. & P. In Psychiatry and Neuroscience Update: from Translational Research To a Humanistic Approach Vol., 113–126 (Springer, 2019).

Pichot, V. et al. Wavelet transform to quantify heart rate variability and to assess its instantaneous changes. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985). 86, 1081–1091. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1999.86.3.1081 (1999).

Vigo, D. E. et al. Circadian rhythm of autonomic cardiovascular control during Mars500 simulated mission to Mars. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 84, 1023–1028. https://doi.org/10.3357/asem.3612.2013 (2013).

Refinetti, R., Cornelissen, G. & Halberg, F. Procedures for numerical analysis of circadian rhythms. Biol. Rhythm Res. 38, 275–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/09291010600903692 (2007).

Bellone, G. J. et al. Comparative analysis of actigraphy performance in healthy young subjects. Sleep. Sci. 9, 272–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.slsci.2016.05.004 (2016).

Pinheiro, J., Bates, D., DebRoy, S., Sarkar, D. & R Core Team nlme. & : Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. R package version 3.1–162. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme (2023).

Mutak, R. cosinor2: Extended Tools for Cosinor Analysis. R package version 0.2.1.c https://cran.r-project.org/package=cosinor2 (2023).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer-, 2016). https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the cooperation of Belgrano II Antarctic station crewmembers.

Funding

This work was supported by the Office of Naval Research Global, Grant Number N62909-22–1-2008; the Ministry of Defense grant PIDDEF Nº 06/14; the Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Técnica (ANPCyT) grant PICTO 2017–0068; the Canadian Space Agency (CSA) [25HLSDM10]; The Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) [RGPIN-2025-06688]; and the Research Scholar Program of the Fonds de Recherche du Québec - Santé (FRQS) [#297725].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.T. study conception and design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, drafting the manuscript; A.F. data collection and data interpretation; B.C. and G.L.E. data collection; E. S. L. data collection and study conception; G.S. and N.P. data interpretation and drafting the manuscript; S. A. P. study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, drafting of the manuscript; D.E.V. study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, drafting of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tortello, C., Folgueira, A., Cauda, B. et al. Autonomic regulation across sleep and wake during an Antarctic overwintering. Sci Rep 16, 1771 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31009-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31009-x