Abstract

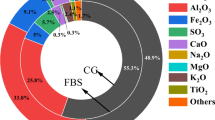

Aiming at the problems of easy settlement and insufficient durability of traditional materials under special backfilling conditions in the northwest loess area, this study prepared controllable low-strength ready-mixed flow solidified soil (CLSM) with solid waste and alkali activator (NaOH and water glass). Through multi-dimensional test and mechanism analysis, the collaborative optimization of material performance and economy was realized, and the durability mechanism of extreme environment was revealed. In this study, the original loess in Lanzhou was used as the matrix, and the L16(45) orthogonal test design was used to construct the ‘28d compressive strength-cost’ double-objective optimization model combined with the entropy weight method. The influence weights of coal gangue, carbide slag, blast furnace slag and alkali activator were quantified, and the optimal mix ratio was determined to be 15% of coal gangue, 3% of carbide slag, 15% of blast furnace slag and 60% of alkali activator. Under this ratio, the 28d compressive strength of CLSM reached 4.44 MPa, and the cost was controlled at 73.23 yuan/ton, taking into account both mechanical properties and economy. The extreme environmental durability test shows that compared with the traditional cement soil, the mass loss rate of the optimal ratio CLSM decreases by 44.83% and the strength increases by 34.89% after 25 freeze–thaw cycles. After 25 times of sulfate dry–wet cycles, the mass loss rate decreased by 55.56%, and the strength increased by 40.01%, especially the resistance to dry–wet cycles was better. The micro-mechanism study revealed that the formation of CLSM strength experienced five stages: ‘alkali-activated depolymerization-three-dimensional network construction exchange agglomeration-secondary hydration enhancement-structural densification’ and High content of solid waste and alkali activator synergistically promoted the formation of C–S–H gel and ettringite. The order of porosity inhibition effect was alkali activator > blast furnace slag > coal gangue > carbide slag, and it was significantly negatively correlated with macroscopic properties. Engineering application verification shows that CLSM has good fluidity in site pouring. Although there are adverse effects in the pouring process, it provides a new material paradigm for green backfilling in the cold and arid regions of Northwest China. In this study, “waste treatment by waste” is realized through the synergistic excitation of solid waste. The multi-objective optimization method improves the scientificity of the ratio. The systematic revelation of extreme environmental durability and micro-mechanism provides theoretical support for the engineering application of fluid solidified soil, which has both environmental protection value and engineering guiding significance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, with the deepening of China’s “The Belt and Road” strategy, the infrastructure construction in the collapsible loess area of Northwest China has also reached a peak period. However, due to the influence of special working conditions such as narrow working space, deep and narrow backfilling area and special-shaped confined space, it is difficult to realize dense filling by traditional backfilling technology in backfilling projects such as foundation pit fertilizer groove, kiln well periphery, gully filling, pipeline groove and underground cavity. At the same time, the unique engineering characteristics of loess, such as porous structure, weak cementation, collapsibility sensitivity and vertical joint development1,2,3, further aggravate the uneven settlement of the filling body and the risk of subsidence damage, which poses a great threat to the safety of the project. According to statistics, the economic loss caused by the uncompacted backfill in the northwest region reaches hundreds of millions of yuan every year. The traditional backfill materials and processes have been unable to meet the current engineering needs. Controlled Low-Strength Materials (CLSM)4 is a kind of green backfill material with high fluidity. Its 28d compressive strength is usually less than 8.3 MPa5, which has the advantages of self-compacting, water stability and economic cost. The material system originated from the “fluidized soil treatment” technology developed in Japan in the 1980s6. By adding cementitious materials to the slag and water to form a pumpable slurry, the full-section filling of the narrow space is realized. In 2017, the concept of “fluid solidified soil” was introduced for the first time in the foundation trench backfill project of utility tunnel in Beijing Sub-Center7, which promoted the large-scale application of this technology in domestic municipal engineering. Among them, the American Concrete Association (ACI) has defined the performance index of CLSM in the 229R-058 standard, and its high fluidity (expansion ≥ 500 mm) and controllable strength characteristics are especially suitable for complex backfill scenarios in the northwest loess area. It is worth noting that compared with traditional concrete, CLSM lacks a standardized ratio design process and specification. Although a lot of work has been done on the study of CLSM, most of them are aimed at the soil itself and the flow solidified soil9,10,11,12,13. It is still a great challenge to evaluate the performance between materials when different solid wastes are solidified. It is still a huge challenge to evaluate the properties of materials when different solid wastes are solidified. On the one hand, the traditional cement soil is prone to cracking and strength attenuation during long-term service14. Higher requirements are put forward for the deformation resistance and durability of materials. On the other hand, the existing engineering applications are mostly concentrated in the eastern humid areas, and there is a lack of systematic multi-objective optimization method for loess-based CLSM mix design, which is difficult to balance mechanical properties, economy and environmental adaptability15,16. Especially in the northwest region of China, through research, it is found that the average value of solid waste per unit of GDP accounts for the largest proportion in other regions of China, about 3.7417. Among them, the proportion of industrial solid waste (tailings, fly ash, coal gangue, slag) in the northwest region ranks third in China, but the comprehensive utilization rate is only 51.78%18. A large amount of solid waste has not been fully utilized. Under the action of subgrade engineering and dry–wet cycle in seasonal frozen soil area, loess engineering undergoes periodic cycle and causes many structural damages19,20,21,22,23. Therefore, it is urgent to use solid waste to improve its performance. The above different factors and the extreme climate under freeze–thaw and sulfate erosion environment pose serious challenges to the durability of materials. By systematically studying the erosion mechanism and performance regulation law of loess-based engineering materials under the action of sulfate dry–wet cycle and freeze–thaw cycle, it is not only the key to reveal the mechanism of environment-material interaction, but also for the anti-erosion design of engineering materials in loess area. Ensuring the long-term stability of infrastructure has important engineering practical value.

Therefore, considering the above background factors, this study takes the undisturbed loess in Qilihe District of Lanzhou as the matrix, through the L16(45) orthogonal test design, combined with the entropy weight method to construct a multi-objective optimization model, with 28d compressive strength and material cost as the evaluation index, to determine the optimal mix ratio; through the freeze–thaw cycle and sulfate dry–wet cycle test, the durability difference between the controllable low-strength ready-mixed fluid solidified loess and the traditional cement soil was systematically compared, and the environmental adaptability mechanism of the solid waste-alkali activator synergistic system was revealed. The research results not only provide a matching design paradigm for green backfill projects in loess areas, but also open up a new way for the large-scale application of industrial solid waste in harsh environments in the northwest region.

Materials and methods

Test materials

Loess

The loess soil samples used in this study were taken from the 2 m deep soil layer of the Pengjiaping project site in Qilihe District, Lanzhou City, and the soil quality was tested to be uniform. According to the United States Unified Soil Classification System (USCS)24, the soil sample was determined to be a low-plastic silty clay (CL group), and it was pretreated according to the ‘Cement Soil Mix Design Specification’ (JGJ/T233-2011)25, and the particles were graded by a 1 mm standard sieve. The basic physical indexes of the soil samples were determined by the ‘Soil Test Method Standard’ (GB/T 50123-2019)26 and the chemical composition ratio was determined by X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF). The specific contents are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Coal gangue

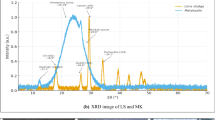

The raw materials of coal gangue are collected from a mining area in Baiyin City, Gansu Province. The appearance of coal gangue is a black-gray block structure. In order to make the material meet the test requirements and the corresponding particle size range, the original coal gangue is ground by a jaw crusher, and the particles are classified by a 1 mm standard sieve. In order to further explore the mechanism of coal gangue in solidified loess, X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) was used to detect its chemical composition and mineral phase characteristics (Table 3). The results show that the main chemical compositions of the coal gangue are SiO2 and Al2O3, while the content of CaO is relatively low. From the perspective of mineral phase, coal gangue is dominated by quartz and kaolinite. It is worth noting that the untreated coal gangue has low pozzolanic activity and is difficult to prepare high-performance building materials. Therefore, in order to improve its reactivity, RX2-30-13 box-type resistance furnace was used for thermal activation treatment in this paper. The specific process conditions were calcination at 700 °C for 2 h. After high temperature modification, the phase characteristics of coal gangue changed significantly (see Fig. 1). The phase characterization of the samples was carried out by X-ray diffraction (XRD) technique (see Fig. 2). The results show that the content of quartz in the calcined sample is significantly reduced, while the kaolinite is relatively increased. This phenomenon indicates that under high temperature conditions, the mineral lattice structure has been reorganized, and some quartz has been transformed into other mineral phases or participated in new chemical reaction processes.

Carbide slag

The carbide slag raw materials used in this experiment were collected from an industrial waste yard in Henan Province. The samples showed a typical gray-white powder shape with a fineness of 200 mesh. By X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) analysis, the chemical composition of the carbide slag is significantly different from the silicon-aluminum-based characteristics of coal gangue. The main component is CaO, with a content of up to 84.9%, while the secondary component includes a small amount of SiO2, as shown in Table 4.

Blast furnace slag

In this experiment, S95 grade slag powder was used, gray white powder, fineness of 200 mesh, specific surface area of 430m2/kg, bulk density of 3.1 g/cm3, 28d activity index of 98.3%. X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis shows that the material is mainly composed of CaO, SiO2 and Al2O3 (Table 5). This chemical characteristic makes it have obvious hydraulic cementing properties, but its activity is poor at room temperature. It is necessary to destroy the inert layer on the surface of the vitreous body by mechanical grinding and cooperate with chemical activators to fully release its pozzolanic activity27.

Test water

In this experiment, the water source used is tap water. Its main advantages are low cost and stable supply, which can meet the basic needs of most experiments.

Alkali activator

In this study, a mixed alkali activator was prepared by analyzing the pure level of solid NaOH and water glass. Among them, water glass is a transparent viscous alkaline liquid, and its chemical formula can be characterized as Na2O·mSiO2·nH2O. As a key parameter, the modulus m directly affects the viscosity of the solution and the depolymerization rate of the silicon-oxygen tetrahedron. The specific parameters of water glass are shown in Table 6.

Sample preparation

In the preparation process of controllable low-strength ready-mixed fluid-solidified loess, it is necessary to systematically pretreat the undisturbed loess samples taken from the engineering site. The collected loess samples are crushed to ensure that the particle size meets the uniformity requirements required for the test. Subsequently, the crushed loess samples were placed in an oven and dried at a suitable temperature (usually about 105 °C) to remove the moisture completely, so as to make dry soil samples. These dry soil samples will be used as basic materials for subsequent tests for further research and testing. Then, the thermal activation treatment of the original coal gangue was carried out. The specific steps include crushing and refining the coal gangue into powder, and calcining it at 700 °C for 2 h through the RX2-30-13 box type high temperature furnace, so as to obtain high activity coal gangue powder. According to DBJ51/T188-2022 Technical standard for engineering application of ready-mixed fluid solidified soil28, the liquid–solid ratio (mass ratio of liquid component to solid component) was designed to be 0.44 to meet the design requirements. Through previous research, the modulus of alkali activator used in the preparation of controllable low-strength ready-mixed fluidized solidified loess in this paper is 1.2 mol/L29. Subsequently, according to the test mix ratio in Table 7, during the preparation process, the alkali activator solution was first mixed with water, and continuously stirred for 10 min before standing for later use. CG, CS, GGBS and loess were fully dry mixed. Then, the mixed solid material is mixed with it, and the hand-held stirring instrument is used to stir for 15 min (stirring instrument speed 500 r/min) to obtain controllable low-strength ready-mixed liquid solidified loess. In the molding stage of the specimen, according to the JGJ/T233-2011 Design Specification for Cement Soil Mix Proportion30, a 70.7 mm3 cube test mold coated with mineral oil was used for molding. During the pouring process, layered pouring and layer-by-layer tamping were carried out, and combined with the shaking table for 1 min to ensure the compactness. After forming, the surface is scraped and sealed with a film to prevent moisture evaporation. After forming, the surface is scraped and sealed with a film to prevent moisture evaporation. After curing at room temperature for 48 h, the specimens were demoulded, and then three specimens in each group were cured to 3,7,14 and 28 d ages under the standard conditions of temperature (20 ± 2) °C and relative humidity 95%. The specific process is shown in Fig. 3.

Test method

In the design of controllable low-strength ready-mixed liquid solidified loess ratio, due to the contradiction between material cost and compressive strength, the traditional single index evaluation cannot fully reflect the comprehensive performance of the material. By constructing a comprehensive evaluation model of material cost and strength performance, the entropy weight method transforms multiple indicators into comprehensive evaluation values, and realizes the collaborative optimization of mechanical properties and economy. According to the entropy weight method, the optimal mix ratio of coal gangue, carbide slag, blast furnace slag and alkali activator is 15%: 3%: 15%: 60% from 16 sets of orthogonal test data. At the same time, the superiority of the screening scheme of this method is also verified in the durability test, which provides a scientific quantitative analysis method for the ratio optimization of complex multi-factor system. In this study, the entropy weight method is introduced to achieve objective weighting by quantifying the dispersion degree of multi-index data, and a comprehensive evaluation system including material cost and compressive strength is constructed. In this system, the key components such as coal gangue, carbide slag, blast furnace slag and alkali activator have a significant impact on the economy. Based on this, this study uses orthogonal test data to establish a bi-objective evaluation model including material cost and compressive strength, and quantitatively analyzes the influence weight of each dosage parameter in the comprehensive cost by entropy weight method. Finally, the optimal mix ratio scheme is determined in order to further verify the durability of the best mix ratio scheme.

Orthogonal test

The purpose of this experiment is to systematically explore the influence of coal gangue, carbide slag, blast furnace slag and alkali activator on the properties of materials, and to provide key data support for subsequent multi-objective optimization. In the test, the undisturbed loess in Qilihe District of Lanzhou City was used as the matrix material, and its fixed content accounted for 70% of the total mass of the mixture.

Four factors and four levels tests were carried out by orthogonal test design method with four factors of coal gangue (A), carbide slag (B), blast furnace slag (C) and alkali activator (D). The specific levels of each factor are set as follows: the content of coal gangue (A) is 5%, 10%, 15% and 20%; carbide slag (B) content of 3%, 6%, 9%, 12%; the content of blast furnace slag (C) is 5%, 10%, 15% and 20%, and the content of the above three materials is calculated as a percentage of the loess mass. The dosage of alkali activator (D) is 0%, 20%, 40% and 60%, which is calculated based on the total mass percentage of A, B and C to ensure stoichiometric balance. The alkali activator was compounded by NaOH and water glass according to the modulus of 1.2. The orthogonal table L16(45) contains 4 factor columns and 1 error column. Through 16 groups of design test combinations, the influence law of each factor is comprehensively analyzed. The specific mix ratio design is detailed in Tables 8 and 9.

Unconfined compressive strength test

The specimens with 3, 7, 14 and 28 days of maintenance were placed in a WHY-3000 hydraulic testing machine for crushing test. In order to ensure the accuracy of the test data and reduce the error, during the test, the operation was strictly in accordance with the operation specifications and each experiment ensured that the press base was clean and the surface was free of impurities and oil pollution. The loading speed of the press is 1 ms/min, and the test instrument and some experimental figures are shown in Fig. 4. In order to improve the reliability and accuracy of the data, three parallel sample tests were set up in each group. The final test results were averaged after eliminating the abnormal values, and the final compressive strength was calculated according to formula 1.

where Qu—unconfined compressive strength of solidified soil (MPa); P—Failure load (kN); A—specimen cross-sectional area (m2).

Freeze–thaw cycle test

The DTR-11 concrete rapid freeze–thaw test chamber (Fig. 5) was used to test the freeze–thaw cycle of 70.7 mm3 cube specimens in a dry environment, and three parallel specimens were prepared in each group. After 28 days of curing, the freeze–thaw cycle test with a cycle of 24 h was carried out in a dry air circulation environment. The specific process was: freezing at-20 °C for 12 h and then switching to 20 °C for 12 h. A total of 6 groups were set up in the test, which were the reference sample (0 cycles) and the test group experiencing 1,5,10,15 and 25 freeze–thaw cycles. At the end of each cycle, the mass of the sample was measured and the mass loss rate was calculated, and the unconfined compressive strength was tested to calculate the strength loss rate.

Sulfate dry–wet cycle test

In the sulfate-dry–wet cycle test, the optimal ratio after 28 days of curing was selected to prepare a standard cube sample of 70.7 mm. The standard cube sample was subjected to 0, 1, 5, 15, and 25 cycles, respectively. The 5% Na2SO4 solution was added to the liquid storage tank. During the experiment, it was always satisfied that the liquid level of the solution exceeded the surface of the specimen by 20 mm. Each cycle was designed for 24 h. The single cycle was soaked in Na2SO4 solution for 16 h and dried at high temperature for 8 h. After the test, the mass loss rate and the strength change were measured by the pressure machine, and compared with the cement soil with the same solid waste content. The experimental instrument is shown in Fig. 6.

Micro-morphology test

In order to study the internal microstructure of the samples after erosion, the concrete specimens after sulfate dry–wet cycle and freeze–thaw cycle were crushed by a press machine. The Φ5 mm × 5 mm specimens were selected from the specimens, and ultrasonic cleaning was performed using acetone and anhydrous ethanol in turn (frequency 40 kHz, lasting 15 min), and then dried at room temperature for 12 h and dehydrated in a vacuum drying oven at 50 °C for 6 h. The surface of the sample was sprayed with gold. Then, the JSM-5600LV scanning electron microscope manufactured by Japan Electronic Optics Co., Ltd. was used for SEM test and combined with Image-Pro Plus (IPP) image analysis technology to quantify the porosity and analyze the pore distribution characteristics, particle cementation morphology and hydration product type of solidified soil under different ratios. When the porosity is calculated by Image-Pro Plus, the threshold is set to 106 by graying the image and adjusting the brightness, contrast and other parameters. The SEM test instrument is shown in Fig. 7 below.

Results

Analysis of orthogonal test results

According to the orthogonal test mix ratio parameters in Table 9, the samples were prepared and the unconfined compressive strength was measured. The specific data are shown in Table 10. In this study, the range analysis method was used to quantify the orthogonal test data. This method revealed the influence of factor level changes on the index by calculating the range (R-value) of the response values at different levels of each factor. In this study, the influence of coal gangue (A), carbide slag (B), blast furnace slag (C) and alkali activator (D) on 28 d unconfined compressive strength was quantitatively analyzed by this method. The traditional flow chart of range analysis is shown in Fig. 8.

In the range analysis of the orthogonal test, the sum of the response values corresponding to each level of factor A is recorded as K1, K2, K3, K4, and the mean value of the response value is expressed as k1, k2, k3, k4. After calculating the average value of each water by the formula ki = Ki/n (n is the number of horizontal repetitions, n = 4 in this experiment), the factor range RA = max (ki) − min (ki) is defined by the difference between the maximum mean and the minimum extreme value, which reflects the regulation range of the factor level change on the test index. The specific calculation results are shown in Table 11 and Fig. 9.

It can be seen from the Fig. 9 that with the increase of curing time, the compressive strength of each factor at different levels shows a slow upward trend. This shows that the extension of curing time is helpful to improve the compressive strength, probably because with the passage of time, the physical and chemical processes such as hydration reaction inside the material are more sufficient, forming more hydration products, enhancing its structural compactness and strength, thus improving the compressive performance31.

In the orthogonal test, the most influential factor on the strength of the controllable low-strength ready-mixed fluidized solidified loess sample is alkali activator (D), followed by blast furnace slag (C) and coal gangue (A), and calcium carbide slag (B) has the least influence. The optimal dosage combination is determined by the k value. The larger the k value is, the stronger the influence of the corresponding horizontal dosage on the factor is. By comparing the range size, it is found that the order of sensitivity is alkali activator > blast furnace slag > coal gangue > carbide slag at the curing age of 7, 14 and 28 d. Therefore, the sensitivity of each factor is not affected by the curing age. At each age, the alkali activator (D) has the most significant effect on the compressive strength.

Analysis of optimal mix ratio

Combined with the raw material cost data in Fig. 10, the comprehensive cost of each ratio scheme is calculated. Using the orthogonal test data, a dual-objective evaluation model including material cost and compressive strength was constructed, and its weight was quantitatively analyzed by entropy weight method to determine the optimal mix ratio scheme. The specific implementation steps include data standardization, index proportion calculation, entropy value and difference coefficient calculation, weight distribution and comprehensive evaluation index construction.

The calculation results of the cost of preparing 1 ton of controllable low-strength ready-mixed liquid solidified loess with each ratio are as shown in Table 12. In this study, 16 groups of curing agent ratio schemes were constructed based on the orthogonal experimental design method (L16(45). The 28 d UCS data were obtained by standard curing specimen test, and the cost calculation model was established by combining the unit price and ratio parameters of raw materials, and a bi-objective optimization system including mechanical properties and economy was constructed. Through quantitative analysis of the performance of each ratio in strength (0.95–4.44 MPa) and cost (24.22–135.35 yuan/ton), it provides data support for the collaborative optimization of material performance and cost.

In order to ensure that each evaluation index can achieve a fair comparison in the comprehensive evaluation and ranking, this paper uses mathematical transformation to eliminate dimensional differences and convert the original data into dimensionless standardized values. In the constructed evaluation system, except that the strength index is the higher the better the positive index, the other indicators are the lower the better the negative index. According to the different mathematical characteristics of these two types of indicators, this paper uses formula 2 to preprocess the data.

In the process of standardization, in order to avoid the influence of zero value on the subsequent analysis, this paper needs to carry out the whole translation operation on the standardized data, and its mathematical expression is xij′ = xij + α. Conditions. In this study, in order to ensure that the number is in order to maintain the statistical characteristics of the original data set, the translation coefficient α needs to meet the stability of the minimum constraint value. This paper selects α = 0.0001, which is close to the minimum observation value of the standardized data. The index data matrix after standardization and translation processing is shown in Table 13, which not only eliminates the dimensional difference, but also completely retains the distribution law of the original data.

The entropy weight method is a method to assign weights to different indicators based on the information entropy theory. It determines the degree of dispersion by calculating the information entropy of each indicator, so as to determine how many components each indicator should occupy. This method can deeply analyze the hidden information in the data, establish a mathematical model for evaluation, avoid the influence of subjective factors, and make the actual importance of each index objectively reflected.

-

(1)

Data matrix.

The standardized data are organized into a data matrix Y = (yij), where i = 1, 2,…, 16 (representing 16 ratios), j = 1, 2 (j = 1 represents the compressive strength of 28d, j = 2 represents the cost).

-

(2)

Calculate the proportion pij of the i th sample value under the j th index.

The proportion of the index is calculated according to Formula 3, and the results are shown in Table 14

-

(3)

Calculate the entropy value of the jth index ej.

The index entropy is calculated according to Formula 4, and the results are shown in Table 15.

Calculate the difference coefficient gj of the j th index.

The difference coefficient of the index is calculated according to Formula 5, and the results are shown in Table 16.

-

(4)

Calculate the index weight wj of the j th index.

The index weight is calculated according to Formula 6, and the results are shown in Table 17.

According to Formula 7, the comprehensive index is calculated and sorted. The results are shown in Table 18.

The comprehensive evaluation value S reflects the overall performance of different ratio schemes. The higher the evaluation value, the better the comprehensive performance of the ratio in the two key factors of 28-day compressive strength and cost. According to the calculation results, the comprehensive evaluation value of L9 ratio (Coal gangue 5%, carbide slag 3%, slag 20%, alkali activator 40%) is the highest, reaching 0.8304, which shows that the ratio achieves the optimal balance between mechanical properties and economy, showing the best comprehensive performance.

When choosing the optimal mixing ratio, it is reasonable to regard the compressive strength and cost as factors with equal weight. This choice is not to deny the importance of mechanical properties in the construction process, but is determined by the particularity of the mixing ratio decision and the comprehensive needs of engineering practice. From the perspective of the whole life cycle of the project, a reasonable mixing ratio needs to take into account both short-term costs and long-term benefits. If only the compressive strength is given priority, although the mechanical properties can be improved, it will significantly increase the cost of material procurement; if the cost is simply emphasized, it may lead to insufficient strength due to the reduction of the proportion of key components, resulting in additional expenditures such as structural maintenance and reinforcement in the later stage, and even potential safety hazards. The comprehensive evaluation value of L9 ratio (coal gangue 5%, carbide slag 3%, slag 20%, alkali activator 40%) is the highest (0.8304), which just proves that it realizes cost optimization on the basis of 28-day compressive strength standard, avoiding the extreme situation of ‘too strong to be expensive’ or ‘too cheap to be weak’.

Analysis of frost resistance

Rate of quality-led loss

The mass change of the controlled low-strength ready-mixed fluid-solidified loess sample and cement soil under the action of freeze–thaw cycles is shown in Fig. 11, and both show two-stage changes. The first is the quality growth stage, and the quality reaches the peak at the fifth freeze–thaw cycle, which is 2.9% and 1.6% higher than the initial value. This is due to the fact that the soil sample is in the early stage of the test. On the one hand, the bonding effect of the cementitious product produced by the hydration reaction of the solid waste material can well resist the frost heave force. On the other hand, in the early stage of the test, the overall performance of the two is strong, and the cohesion is enough to eliminate the tensile stress caused by freeze–thaw, but the amount of hydration products in cement soil is limited by its own material. Therefore, it shows that the quality of CLSM in the first stage increases slightly.

As the frost heaving effect of the freeze–thaw cycle continues to occur, the internal pores and micro-cracks of the soil sample continue to extend and widen, so that the internal pores increase, and the overall performance of the soil sample decreases sharply until the damage is destroyed. The macroscopic performance is that the mass loss rate reaches 4.1% and 8.5%32,33,34. The overall average mass loss of CLSM is reduced by 50%. This is because the cement soil sample is looser than the CLSM pore structure and the tensile performance is relatively weak, and it is more vulnerable to damage during the freeze–thaw cycle. Secondly, cement soil is only solidified by C–S–H water generated by hydration reactions such as C2S and C3S, while CLSM can provide sufficient cementitious materials, resulting in less spalling of soil samples in the later stage of the test. The low-strength ready-mixed flow-solidified loess sample can also show stronger durability.

Strength loss rate

The quality changes of CLSM and cement soil were observed through experiments, and the durability of the samples under freeze–thaw action was preliminarily judged. However, its strength still needs to be determined by analysis. It can be clearly observed from the data in Fig. 12 that the addition of solid waste makes the controllable low-strength ready-mixed fluid-solidified loess sample show significant performance advantages in the freeze–thaw cycle stage. After 25 freeze–thaw cycles, the strength of CLSM only decreased by 30.6%, which was 34.89% higher than that of cement-soil slurry. From the overall analysis, CLSM is used to improve the overall strength of cement soil by more than 35%. This difference is mainly due to the combination of solid waste and alkali activator to improve the pore structure of the sample, reduce the porosity and enhance the internal connectivity, effectively reducing water penetration. The optimized pore structure also reduces the possibility of ice crystal formation, reduces the damage of the material caused by the freeze–thaw cycle, and delays the micro-crack propagation35.

Compressive strength loss rate

Cement soil foundation and subgrade are prone to settlement and deformation under load. As shown in Fig. 13, the unconfined compressive strength of CLSM and cement soil under different freeze–thaw cycles shows a downward trend. When the number of freeze–thaw cycles is 0 times, the unconfined compressive strength of the controllable low-strength ready-mixed fluidized solidified loess is 4.44 MPa and 2.72 MPa. With the number of freeze–thaw cycles to 25 times, the strength is slowly reduced to 3.33 MPa and 1.89 MPa, respectively. The strength of the two is 25% and 30.51% lower than that of the initial state. The overall analysis shows that the strength of CLSM is more than 66.29% higher than that of cement soil, which can meet the strength requirements of most projects29, showing that the degree of structural damage under freeze–thaw action is low.

In summary, through different analysis results, it is concluded that the frost resistance of controllable low-strength ready-mixed flow solidified loess after adding solid waste is better than that of traditional cement soil. This result fully proves the importance of the synergistic effect of solid waste and alkali activator, and also provides an important reference for future related research and practical application.

Sulfate dry–wet cycle analysis

Rate of quality-led loss

The effects of two different solidified materials on the number of dry–wet cycles of solidified soil were studied. Figure 14 shows that under the condition of sulfate-dry–wet cycle, the mass loss rate of controllable low-strength ready-mixed flow solidified loess and cement soil samples increased slowly with the increase of cycle times. Specifically, the mass loss rates of CLSM were 0.35% and 1.6 after 1–5 cycles, while the mass loss rates of cement soil were 0.82% and 3.95%, respectively. As the number of dry–wet cycles increases, the negative effects of shrinkage strain continue to accumulate, resulting in the gradual formation of cracks inside the solidified soil36. After 25 cycles, the mass loss rate of CLSM reached 6.80%, while that of cement soil was 2.25 times that of CLSM. In the whole test process, the performance of CLSM is due to cement soil, and the mass loss improvement rate is above 55.26%, which is similar to the research law of37.

Strength loss rate

Compared with ordinary cement soil samples, the controllable low-strength ready-mixed flow-solidified loess samples with solid waste showed better performance under sulfate-dry–wet cycle conditions, and the strength loss was significantly smaller. Figure 15 shows that after 25 sulfate-dry–wet cycles, the strength of the controlled low-strength ready-mixed flow solidified loess sample decreased by 22%, while the strength of the ordinary cement soil sample decreased by 38%, which was 72.73% lower than that of CLSM. This is mainly because the synergistic effect between solid waste and alkali activator optimizes the pore structure of the sample, reduces the space for the formation of hydration products, effectively prevents the internal micro-cracks caused by the extrusion of hydration products, and further reduces the shrinkage and the damage caused by sulfate. On the whole, the strength of CLSM is increased by more than 40, and it can be seen that the resistance to sulfate erosion is better than that of cement soil.

Micro performance

SEM test

The micro-morphology of the controllable low-strength ready-mixed flow-solidified loess sample and cement soil after 5, 15, 25 freeze–thaw and sulfate dry–wet cycle tests is shown in Figs. 16, 17, 18 and 19. The overall observation shows that CLSM has better frost resistance and resistance to dry–wet cycle than cement soil. From Figs. 17 and 18, it is observed that a small number of small voids and cracks and a large number of unhydrated particles appear inside the effluent soil during the fifth cycle, while CLSM has a higher surface integrity. At this time, its internal hydration reaction has both advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand, the hydration product fills its pores to enhance the overall stability. On the other hand, due to the gradual increase of its products with the number of cycles during the hydration reaction, tiny cracks will be generated after the pore extrusion, which will cause hidden dangers in the later stage. When the number of cycles reaches 15 times, the cement soil and CLSM are damaged to varying degrees under salt erosion and dry–wet action. The internal pores of the cement soil are further developed and expanded to make the internal overall structure loose, while the CLSM still has a certain degree of compactness. As the ions invade the interior, the hydration reaction occurs, and the internal pore wall is subjected to extrusion stress, resulting in cracks on the surface, which shows the phenomenon of first becoming crisp. However, compared with cement soil, CLSM can provide more active components such as SiO2 and Al2O3 to fully react with Ca (OH)2, which provides favorable conditions for the formation of C–S–H gel. With the continuous accumulation of erosion, when the test was carried out to 25 times, pores appeared inside the CLSM, and the overall performance was greatly reduced compared with the initial state. This is due to the increasing internal erosion, and the cohesive force of the cementitious products produced by the active components provided by CLSM is not enough to resist the tensile stress generated by the corrosion products produced by the erosion, so that its performance is greatly reduced. The macroscopic performance is that the mass loss rate increases first and then decreases, and the strength change also has similar changes.

It is observed from Figs. 18 and 19 that after the 5th cycle, defects appear on the surface of CLSM, while the pores and cracks on the surface of cement soil are more obvious. As the test continued, tiny holes gradually appeared on the surface of CLSM until the pores were connected and developed into cracks, while the surface of cement soil evolved from holes to partial shedding and large defects appeared. This is because the expansion stress caused by free water freezing in the freezing stage of freeze–thaw cycle changed from less than internal cohesion to greater than cohesion, which gradually aggravated its internal damage. However, compared with cement soil, CLSM has better frost resistance. This is because cement soil only provides a small amount of hydration products, so that its overall structural strength to resist frost heaving stress is not enough to support the complete test cycle, while CLSM can provide more hydration products to resist frost heaving stress. The deterioration process of CLSM and cement soil is similar to that of sulfate dry–wet cycle, but the frost resistance of CLSM is slightly lower than that of sulfate dry–wet cycle from the changes of macroscopic mass loss and microscopic morphology.

SEM image binarization processing

In the microstructure analysis of scanning electron microscope (SEM) images, binarization processing is a key technical means. Since the microscopic morphology in SEM imaging contains macroscopic visible pores and particles, as well as fine pores and particle interfaces that are difficult to distinguish by the naked eye (Fig. 20a), it is necessary to use image processing technology to enhance the recognition of structural boundaries to meet the needs of computer software for quantitative analysis. In this process, the pore area is usually set to black, while the particle and interface area are retained as white, so that the pore distribution characteristics are clearly presented in the binarized results (Fig. 20b).

Porosity analysis

Porosity is a key parameter to characterize the compactness of materials, which has a significant effect on the mechanical properties and permeability of solidified loess. The area ratio of pores in the sample can reflect its compactness at the macro level and directly affect the mechanical properties. In this study, based on the results obtained from the previous single factor test (see Table 7), through rigorous screening, eight representative mix ratios (numbered 1, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 13, respectively) were determined. After curing to 28 d age and achieving a stable performance state, the microscopic mechanism research was carried out in depth on this basis. Based on the Image-Pro Plus (IPP) image analysis technology, the SEM images of 8 groups of typical ratios after the test were quantitatively analyzed to reveal the change rule of the surface porosity of the sample.

From Fig. 21, it can be seen that with the increase of the content of coal gangue, carbide slag, blast furnace slag and alkali activator, the surface porosity of the controlled low-strength ready-mixed fluidized solidified loess sample gradually decreases. There are significant differences in the inhibition effect of different materials on porosity. According to the intensity of action, the order is: alkali activator > blast furnace slag > coal gangue > carbide slag. This result is highly consistent with the conclusion of the previous macroscopic mechanical properties test, indicating that there is a significant negative correlation between porosity and material strength, that is, the larger the porosity, the lower the material strength. From the analysis of the mechanism of action, the main reasons for the decrease of porosity can be attributed to the following two aspects: on the one hand, fine particles in solid waste materials and alkali activators can fill the initial pores between soil particles to achieve physical densification; on the other hand, hydration reactions occur between materials to form cementitious products (such as C–S–H gel and ettringite), which further fill pores and strengthen the interfacial bonding between particles through chemical cementation. The synergistic effect of the above two mechanisms makes the internal structure of the controllable low-strength ready-mixed flow solidified loess tend to be denser, and finally the strength is improved in the macroscopic mechanical properties.

Combined with the porosity data and the characteristics of the mix ratio in Fig. 21, the analysis is as follows: Group 7 (alkali activator 0%) has a weak hydration reaction due to the absence of alkali activator, the formation of cementitious products is very small, the pores between loess particles are difficult to fill, the porosity is as high as 39.62%, and the structure is loose. Group 8 (alkali activator 60%) activates active components such as coal gangue and blast furnace slag with high content of alkali activator, generates a large number of C–S–H gel and Aft, fills the pores closely, the porosity is as low as 11.23%, and the structure is dense. Group 6 blast furnace slag 20%) provides sufficient active ingredients (such as SiO2, Al2O3) due to high content of blast furnace slag, which strengthens the hydration reaction and reduces the porosity to 15.45%. Group 2 (coal gangue 20%) has a high content of coal gangue, but lacks the synergistic effect of alkali activator and other components. The activity of coal gangue alone is limited, and the porosity is 22.45%. The porosity of other groups (such as group 1, 3, 4, 5) is between 15.45 and 34.52% because the proportion of solid waste or alkali activator does not reach the optimal ratio.

The whole shows that when the content of high active components such as alkali activator and blast furnace slag is sufficient, the porosity can be effectively reduced and the structural compactness can be optimized by enhancing the hydration reaction and promoting the formation of cementitious products, which reflects the key regulation effect of each component on the microscopic pore structure, and then affects the mechanical and durability properties of controllable low-strength ready-mixed flow solidified loess.

Analysis of CLSM strength formation mechanism

Based on the strength development mechanism of controllable low-strength ready-mixed flow solidified loess, this paper deeply discusses its strength formation mechanism. The strength development of the material is a complex process involving multi-scale and multi-stage, and its core lies in the physical and chemical synergy between geopolymer and soil particles under the alkali-activated system. Figure 22 shows a brief process of the formation of controllable low-strength ready-mixed fluid-solidified loess.

After analysis, the strength formation of controllable low-strength ready-mixed flow solidified loess is a complex process of multi-scale synergy, involving multiple mechanisms such as chemical cementation, physical compaction and particle recombination. Based on microscopic experiments and theoretical analysis, the strength formation mechanism can be condensed into the following five key stages:

Alkali-excited depolymerization stage

The strong alkaline environment provided by alkali activator (NaOH and water glass) realizes the depolymerization of silicon-aluminum raw materials through multiple chemical interactions. Firstly, the OH generated by the dissociation of NaOH attacks the Si–O-Si bond in coal gangue and slag, causing it to break to form [SiO4(OH)4]4−. At the same time, the SiO32- generated by the hydrolysis of water glass further promotes the depolymerization reaction and releases more active silicon monomers. The dissolution of carbide slag to form Ca2+and OH- not only provides a high calcium source, but also maintains a strong alkaline environment with NaOH. Under this condition, the Al–O–Al bond breaks to form [Al (OH)4]− and combines with Na to form NaAl (OH)4, which significantly improves the activity of aluminum. This process converts the originally inert silicon-aluminum raw materials into active monomers, providing sufficient material basis and reaction sites for subsequent polymerization reactions. Figure 23 is a brief chemical reaction flow chart for the alkaline excitation depolymerization stage.

Three-dimensional network construction phase

In the three-dimensional network construction stage, the active silicon-aluminum monomer forms a three-dimensional network structure with high strength characteristics through polycondensation reaction. The N–A–S–H geopolymer gel was synthesized by polycondensation of active monomers, and its chemical formula was Na2O·Al2O3·4SiO2·nH2O. The gel has a tetrahedral-octahedral alternating three-dimensional network structure, forming a high-strength skeleton through Si–O–Al covalent bonds. The incorporation of Ca2+ promoted the conversion of partial N–A–S–H to C–A–S–H, improved the calcium-silicon ratio of the gel, and enhanced the structural stability. In this process, the gel not only filled the pores between the soil particles, but also tightly connected the particles by chemical bonding, which significantly improved the overall strength of the material.

Ion exchange and particle agglomeration

In this stage, the flocculation and agglomeration of soil particles are realized by cation exchange and electric double layer compression mechanism. The core process is as follows: in alkaline environment, Na+, K+ ions exchange with Ca2+ and Mg2+ adsorbed on the surface of clay minerals, and the thickness of electric double layer is compressed to less than 2 nm. The repulsive force between the particles is weakened, and the van der Waals force dominates the formation of a flocculation structure. The soil particles change from a dispersed state to a cluster accumulation, which significantly improves the compactness. The flocculation structure formed at this stage provides early skeleton support for the solidified soil. The degree of particle agglomeration directly affects the spatial distribution of the subsequent secondary hydration reaction. The micropores between the aggregates provide a reaction site for the formation of C–S–H gel. Figure 24 shows the geometric diagram of the diffusion double layer structure38.

Geometric diagram of diffusion electric double layer structure38.

Secondary hydration enhancement stage

In the secondary hydration enhancement stage, the unreacted aluminosilicate particles continue to undergo pozzolanic reaction, and their vitreous components are dissolved in alkaline medium and combined with Ca2+ in the system to form C–A–S–H gel. At the same time, Al3+ in the system reacts with Ca2+ and SO42- to form needle-like ettringite crystals. The ettringite is interspersed in the geopolymer network in a needle-like shape to form a ‘micro-aggregate-gel’ interpenetrating structure. In addition, the secondary hydration products strengthen the particle interface by mechanical interlocking (ettringite and geopolymer interlocking), chemical bonding (≡Si–O–Ca bond) and micro-pore filling (nano-C–A–S–H filling micro-pores).

Structure densification stage

The nano-scale geopolymer gel preferentially fills the micropores, and the micron-scale C–S–H gel encapsulates the soil particles to form a dense shell. Construct a continuous three-dimensional network structure. In this process, the geopolymer network provides initial strength, the ettringite crystal enhances toughness, and the C–S–H gel optimizes compactness. The three achieve strength improvement through the triple mechanism of ‘chemical cementation-physical filling-structural synergy’, as shown in Fig. 25.

CLSM engineering application

CLSM is widely used in backfill engineering as a high-quality backfill material with high heat at present. However, most of the studies are indoor studies that cannot reflect the performance of CLSM in real environments. Therefore, in order to further explore the application performance of CLSM, this paper relies on a project in Lanzhou, Gansu Province. In this project, CLSM is mainly prepared by coal gangue, carbide slag, blast furnace slag and alkali activator and applied to trench backfilling and indoor bottom paving, which verifies its feasibility for this paper. The specific construction process is as follows: the prepared loess and water are mixed and stirred, and the curing agent is added to stir for about 15 min after it is uniform. After the naked eye observes that it is uniform without caking, it is poured through the pipeline. The specific construction process is shown in Fig. 26.

Analysis of pouring and forming process

Both the groove and the room are poured after mixing the mixture on site, as shown in Fig. 26. The groove size is about 12 m × 1 m, and the narrowest width is about 0.3 m, which can accommodate 18 m3. Through practical engineering application, it is found that during the process of CLSM pouring, the phenomenon of blocking pipeline, bleeding and micro accumulation occurs (see Fig. 28). When the CLSM is mixed and poured through the pipeline, the slurry in the upper layer of the mixing box is precipitated due to the gravity of the particles over time, which increases the density of the lower layer during the subsequent pouring, and the pipeline is lack of fluidity and blockage and accumulation occur. However, through the initial setting and fluidity test of the on-site construction materials, both of them meet the requirements of the specification. The initial setting time is 8.5 h and the expansion degree is 320 mm (see Fig. 27), indicating that the CLSM fluidity meets the requirements. When the groove is poured, a small amount of deposits can still be lifted by the buoyancy of the slurry and flow to a distance, and the whole process can still maintain its uniformity. After the pouring is completed, there is a bleeding phenomenon on the surface, which is caused by precipitation. The surface is smooth and crack-free after natural curing for 12 h, which shows good stability and can carry people standing, which indicates that CLSM can provide sufficient bearing capacity. However, there are still some limitations in the construction process. Due to the phenomenon of precipitation accumulation, secondary mixing and dredging of pipelines are likely to cause negative effects such as affecting the construction period and increasing the construction cost. Therefore, for such phenomena, automatic mixing equipment can be set up or the length of the pipeline can be reduced.

Conclusions

The CLSM was developed by using different solid wastes, and the optimal mix ratio under the multi-objective optimization model of CLSM was studied based on the combination of orthogonal test design and entropy weight method. The strength change rule of CLSM under freeze–thaw and dry–wet cycles was characterized by comparing the sample with cement soil. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

The multi-objective optimization model was constructed by the orthogonal test design and the entropy weight method. The optimal ratio of CLSM was determined as coal gangue 15%, carbide slag 3%, blast furnace slag 15% and alkali activator 6%. This method realizes the collaborative optimization of material performance and economy by quantifying the influence weight of each factor on strength (28d compressive strength 4.44 MPa) and cost (73.23 yuan/ton).

-

(2)

The range analysis of orthogonal test shows that the order of influence of curing age (7d, 14d, 28d) on CLSM strength is: alkali activator > blast furnace slag > coal gangue > calcium carbide slag. Among them, the alkali activator dominates the strength development by activating the solid waste activity, while the carbide slag mainly plays an alkaline environmental regulation role due to its high CaO content, and its contribution to the strength is relatively low.

-

(3)

Under the optimal mix ratio, the strength of CLSM is greatly improved compared with that of cement soil in frost resistance and dry–wet cycle performance. The overall mass loss is reduced by more than 44.83% and 55.56% respectively, and the strength is increased by more than 34.89% and 40.01% respectively. Among them, the resistance of CLSM to dry–wet cycle is higher than that of frost resistance. This is mainly because CLSM provides sufficient cementitious material, which increases the internal bonding performance of soil samples and makes the overall performance of soil samples better in the later stage of the test.

-

(4)

Through SEM and IPP image analysis, it is revealed that the microstructure of controllable low-strength ready-mixed fluid-solidified loess undergoes the evolution process of loose particle accumulation, flocculent gel encapsulation to dense three-dimensional network with the increase of coal gangue (5–20%), carbide slag (3–12%), slag (5–20%) and alkali activator (0–60%). The synergistic effect of high content solid waste and alkali activator significantly promotes the formation of C–S–H gel and ettringite crystals. The order of porosity inhibition effect is: alkali activator > slag > coal gangue > carbide slag, and its inhibition effect is significantly negatively correlated with macroscopic mechanical properties. In addition, the strength formation process of controlled low-strength ready-mixed fluid-solidified loess includes five key stages: alkaline excitation depolymerization, three-dimensional network construction, ion exchange agglomeration, secondary hydration enhancement and structural densification.

-

(5)

Through engineering application, it is concluded that CLSM has good fluidity and stability from pouring to forming. Although it is slightly different from the ideal indoor state, it all meets the requirements of trench backfill bearing capacity. However, due to the limitations of construction technology, it is easy to produce bleeding, accumulation and other phenomena after on-site mixing, which needs to be further optimized.

Data availability

All data supporting this study are included in this article.

References

Wentong, T. et al. Research progress of loess dynamics and frontier scientific problems. J. Geotech. Eng. 37(11), 2119–2127 (2015).

Peng, J. et al. Preface to the special issue on “Loess engineering properties and loess geohazards”. Eng. Geol. 236, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2017.11.017 (2018).

Li, P. & Qian, H. Water resource development and protection in loess areas of the world: A summary to the thematic issue of water in loess. Environ. Earth Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-018-7984-3 (2018).

Wang, C. et al. A comprehensive review on mechanical properties of green controlled low strength materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 363, 129611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.129611 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Research progress on controlled low-strength materials: Metallurgical waste slag as cementitious materials. Materials 15(3), 727. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15030727 (2022).

Wooden flag, line macro. Fluidized treatment of soil’s mechanical properties. Civ. Eng. Soc. 62, 618–627. https://doi.org/10.2208/62.618 (2006).

Zhang, X. Research on composite foundation of long spiral pressure grouting ready-mixed flow solidified soil in Beijing Sub-Center. Build. Technol. Dev. 45(02), 59–62 (2018).

ACI 229R-05, Controlled Low Strength Materials (CLSM) (2005).

Aggarwal, J., Goyal, S. & Kumar, M. Sustainable utilization of industrial by-products spent foundry sand and cement kiln dust in controlled low strength materials (CLSM). Constr. Build. Mater. 404, 133315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.133315 (2023).

Devaraj, V., Mangottiri, V. & Balu, S. Prospects of sustainable geotechnical applications of manufactured sand slurry as controlled low strength material. Constr. Build. Mater. 400, 132747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132747 (2023).

Du, J. et al. Characterization of controlled low-strength materials from waste expansive soils. Constr. Build. Mater. 411, 134690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134690 (2024).

Etxeberria, M. et al. Use of recycled fine aggregates for Control Low Strength Materials (CLSMs) production. Constr. Build. Mater. 44, 142–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.02.059 (2013).

Tan, H. et al. Experimental study on the influence of fiber characteristics on the working property of underwater flowable solidified soil: Flowability, anti-dispersion, strength and anti-scour resistance. Ocean Eng. 312, 119230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2024.119230 (2024).

Zhou, Y. et al. Research status and prospect of low strength fluid filling materials. Materials 38(15), 130–138 (2024).

Lu, J. et al. Mix design and performance of lightweight ultra high-performance concrete. Mater. Des. 216, 110553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2022.110553 (2022).

Zhou, Min et al. Mixture design methods for ultra-high-performance concrete—A review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 124, 104242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2021.104242 (2021).

Chen, C. Analysis of regional GDP and major pollutants in China. Econ. Res. Guid. 20, 8–10 (2015).

Wei, T., Feng, L., Fen, B. et al. Research on the current situation and countermeasures of comprehensive utilization of general industrial solid waste in China. Environ. Prot. Sci. 1–10.

Liuyang, G. et al. Effect of sulfate on the aggregation of clay particles in loess. Front. Earth Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2022.790882 (2022).

Qingsong, D. et al. Simulation of hydrothermal field difference and anti-frost heaving of highway subgrade with sunny-shady slopes in seasonally frozen regions. J. Central South Univ. (Sci. Technol.) 53(8), 3113–3128 (2022).

Jian, Xu. et al. Comparative test study on deterioration mechanism of undisturbed and remolded loess during the freeze–thaw process. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 14(03), 643–649 (2018).

Jian, Xu. et al. Experimental study on deterioration behavior of saline undisturbed loess with sodium sulphate under freeze–thaw Action. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 42(09), 1642–1650 (2020).

Qian, W. et al. Liquefaction behaviors of the saturated loess in Lanzhou City under freezing-thawing conditions. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 39(S1), 2986–2994 (2020).

ASTM. Standard Practice for Classification of Soils for Engineering Purposes (Unified Soil Classification System). ASTM D2487-17e1 (ASTM, West Conshohocken, 2017).

Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China. Specification for design of cement-soil mixture ratio: JGJ/T 233-2011 (China Construction Industry Press, Beijing, 2011).

Ministry of Water Resources of the People’s Republic of China. Geotechnical test method standard: GB/T 50123-2019 (China Plan Publishing House, Beijing, 2019).

Ustabaş, İ & Kaya, A. Comparing the pozzolanic activity properties of obsidian to those of fly ash and blast furnace slag. Constr. Build. Mater. 164, 297–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.12.185 (2018).

DBJ51/T188-2022 technical standard for engineering application of ready-mixed fluidized solidified soil.2024.

Yu, Yu. et al. Mechanical characteristics and mechanism analysis of geopolymer solidified soft clay. J. Build. Mater. 23(2), 364–371 (2020).

Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China. Specification for design of cement-soil mixture ratio: JGJ/T 233-2011 (China Construction Industry Press, Beijing).

Rovnanik, P. Effect of curing temperature on the development of hard structure of metakaolin-based geopolymer. Constr. Build. Mater. 24(7), 1176–1183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2009.12.023 (2010).

Chamberlain, E. J. & Gow, A. J. Effect of freezing and thawing on the permeability and structure of soils. Dev. Geotech. Eng. 26, 73–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-41782-4.50012-9 (1979).

Hou, C., Cui, Z. & Li, Y. Accumulated deformation and microstructure of deep silty clay subjected to two freezing-thawing cycles under cyclic loading. Arab. J. Geosci. 13, 452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-020-05427-2 (2022).

Wang, M. et al. Shear strength of frozen clay under freezing-thawing cycles using triaxial tests. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 17, 761–769. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11803-018-0474-5 (2018).

Liu, Qi. et al. Effect of freeze–thaw cycles on the shear strength of root-soil composite. Materials 17, 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17020285 (2024).

Shu, B. et al. Carbon emission, durability and application of solid waste based solidification material solidification soil. Mater. Today Sustain. 31, 101135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtsust.2025.101135 (2025).

Zhang, X. et al. Durability of solidified sludge with composite rapid soil stabilizer under wetting–drying cycles. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 17, e01374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01374 (2022).

Shang, F. et al. Analysis of influencing factors of clay particle diffusion electric double layer. Glacier Permafrost 44(02), 495–505 (2022).

Funding

The key research and development transformation plan project of Qinghai Province (Batch Number 2024-0204-SFC-0069); Lanzhou Technology and Business College (service local) school-level industry-university-research cooperation project in 2025 (LSCXY2025-003); Lanzhou Science and Technology Plan Project (2024-4-5); Gansu province science and technology plan project (key research and development plan-industry) (Approval Number: 23YFGA0083);

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Bingjie Liu: Formal analysis, methodology, resources, supervision, conceptualization. Shuaihua Ye: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, data curation, validation, investigation, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, software, supervision, visualization, formal analysis. Hongzhuang Shi: Project administration, methodology, resources, software. Changliu Chen: Investigation, supervision, validation, visualization. Zhao Long: Investigation, validation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. Laping He: Formal analysis, investigation, software, validation. Can Li: Formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing—original draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, B., Ye, S., Shi, H. et al. Multi-objective optimal control and application of solid waste synergistically excited fluidized solidified soil. Sci Rep 16, 1270 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31014-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31014-0