Abstract

To address the instability issues of distributed-drive electric vehicles (DDEV) operating on roads with abrupt changes in adhesion coefficients, a lateral stability control strategy and torque distribution method based on backpropagation (BP) neural network optimization were proposed. First, an Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF) estimation algorithm incorporating real-time variation detection of adhesion coefficients was developed. To ensure rapid response and accurate estimation of current adhesion coefficients during sudden road condition changes, threshold-based real-time detection of adhesion coefficient fluctuations was introduced. Second, a hierarchical stability control strategy specifically designed for varying adhesion coefficient conditions was established. The upper-layer controller employs a Bat Algorithm (BA) optimized BP neural network, which takes the sideslip angle and yaw rate as control targets to calculate the required yaw moment for vehicle stabilization, thereby enhancing real-time computational efficiency and solution accuracy. The lower-layer controller utilizes the estimated road adhesion coefficients to implement a quadratic programming algorithm, optimizing wheel torque distribution to minimizing tire load rate. Finally, a co-simulation platform was constructed using Carsim/Simulink for validation. The results demonstrate that the proposed estimation algorithm can precisely estimate road adhesion coefficients under extreme conditions of abrupt coefficient changes. The developed stability controller significantly enhances both handling stability and driving stability of DDEV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Compared with traditional centralized-drive systems, distributed-drive systems enable more precise control over the power output of individual wheels, thereby enhancing vehicle traction and handling performance across diverse road surfaces, which significantly improves safety and reliability1,2,3. However, when operating on surfaces with significant adhesion coefficient variations such as icy or snowy roads, the stability and controllability of vehicles face substantial challenges4,5.

These road conditions not only markedly compromise vehicle traction and road-holding capacity but may also induce loss of vehicular control or even hazardous accidents6,7.

Tire forces are significantly influenced by the adhesion state of the contact surface, which directly determines vehicular driving performance and handling stability. Therefore, accurate acquisition of road adhesion status is a critical aspect of active safety control system design. Current methods for adhesion coefficient estimation primarily fall into two categories: Cause-based and Effect-based approaches8. The former method employs specialized sensors to capture morphological and physical characteristics at the tire-road interface, analyzing their mechanisms to derive adhesion state information. While demonstrating superior estimation accuracy9,10, this approach exhibits notable environmental sensitivity, suffers from limited sensor robustness against interference, and incurs high costs for specialized sensors, thereby constraining engineering applications. The Effected-based methodology deduces adhesion coefficients by investigating variations in vehicle and tire dynamics parameters caused by adhesion coefficient changes11,12. Typical implementations include neural networks13, Kalman filter estimation14, and fuzzy logic estimation15. However, neural network methods require extensive training datasets, and fuzzy logic approaches heavily depend on engineering expertise, making Kalman filter estimation more prevalent in practice. Among Kalman filter variants, the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) is widely adopted16,17,18. Nevertheless, given vehicles’ inherently highly nonlinear nature, EKF’s reliance on first-order Taylor expansion with linear approximation inevitably introduces truncation errors, resulting in compromised estimation accuracy and potential divergence of results.

Regarding active safety control of Electric Vehicles, numerous scholars have conducted relevant research. Literature19 and Literature20 enhanced active driving safety of electric vehicles through vehicular network communication for environmental risk early-warning and IoT-based driver status monitoring respectively. Literature21 employed VISSIM microscopic traffic simulation and the SSAM safety assessment model to systematically evaluate the traffic performance of Connected and Automated Vehicles (CAVs) under different weather conditions, demonstrating that CAVs can significantly improve both road safety and operational efficiency during adverse weather conditions such as rain and fog. Literature22 develops a hierarchical control architecture based on finite state machine (FSM) that implements inter-axle torque transfer with Maximum Transmissible Torque Search (MTTS) in low-speed conditions to maximize adhesion utilization, while switching to PSO-tuned PID control for optimal slip ratio tracking in high-speed scenarios to ensure driving stability. Literature23 proposes a multilayer yaw moment stability control method based on robust sliding mode predictive control, incorporating varied sideslip conditions to improve trajectory tracking capability and handling stability under extreme scenarios. Literature24 introduces a strategy that calculates required additional yaw moment and steering angles through adaptive laws, with a lower-layer optimization algorithm rationally distributing yaw moments to individual wheels. This method is experimentally verified to outperform conventional adaptive control approaches. Literature25 develops a lateral stability control system employing optimal torque vectoring control, integrating approximate linear quadratic programming principles to design yaw torque control with gain adjustment based on lateral acceleration at the center of mass. Torque distribution is optimized considering constraints from motor peak torque and tire friction circles. Literature26 implements a control strategy incorporating slip ratio estimation, combining Active Disturbance Rejection Control (ADRC) with sliding mode controllers to adapt to diverse driving conditions. This approach effectively mitigates wheel slippage on low-adhesion roads while enhancing both dynamic performance and operational safety. However, although stability control for DDEVs has been extensively studied, existing methods still exhibit significant limitations when handling extreme scenarios involving abrupt changes in road adhesion coefficients. A primary shortcoming of many current research approaches lies in their insufficient adaptability to changing adhesion conditions. This deficiency is first evident in adhesion coefficient estimation: most strategies utilize the peak road adhesion coefficient or define it as a fixed value. Such static assumptions lead to poor estimation performance during rapid, large-magnitude step changes in adhesion coefficient. Some studies attempt real-time estimation; Especially noteworthy is that in previous research, most studies utilized variant Kalman filters (such as Strong Tracking SCKF, Adaptive Square-Root Cubature Kalman Filter ASRCKF, etc.) for road adhesion coefficient estimation, yet none have incorporated a threshold-triggered multi-sampling mechanism within the UKF specifically targeted at handling variations in the road adhesion coefficient. Secondly, at the stability control strategy level—whether traditional PID, sliding mode control (SMC), or model predictive control (MPC)—parameters and structures are typically designed for specific or average operating conditions, resulting in limited dynamic adaptive capability. When the adhesion coefficient changes suddenly or fluctuates substantially, these control strategies often fail to compute the required additional yaw moment for vehicle stability promptly and accurately. While some recent research employs neural network control algorithms, these also face challenges such as slow convergence speed or susceptibility to local optima, compromising control real-time performance and precision.

Addressing these limitations, this study proposes an innovative hierarchical control strategy. Its core contribution lies in significantly enhancing active safety under high-risk conditions involving abrupt changes in the road adhesion coefficient. First, a dynamic change detection-based unscented Kalman filter algorithm is designed for road adhesion coefficient estimation. By introducing a scientifically justified critical threshold, this algorithm identifies significant changes in the road adhesion coefficient. This enables significantly improved real-time estimation accuracy of the road adhesion coefficient during abrupt changes. A hierarchical stability control architecture is further developed. The upper-layer controller utilizes a BA-optimized BP neural network to track ideal centroid sideslip angle and yaw rate. Compared to conventional BP neural network control, this integrated approach demonstrates improved convergence properties and global search capabilities, particularly effective for complex nonlinear optimization problems. The torque allocation strategy employs quadratic programming to dynamically distribute driving forces, optimizing tire load rates based on real-time wheel-specific adhesion coefficient estimates. Simulation results confirm the estimation algorithm’s precision and rapid response in detecting adhesion coefficient changes. The stability controller successfully tracks both yaw rate and centroid sideslip angle relative to their ideal references. Collectively, the proposed system significantly enhances handling stability and driving safety for DDEV.

The whole paper is presented as follows: “Dynamic Change Detection-Based Unscented Kalman Filter” develops a UKF-based estimation algorithm incorporating real-time adhesion coefficient variation detection. “Hierarchical Control Strategy” designs a hierarchical stability control system using BA-optimized neural networks. “Simulation Experiment Validation” conducts simulation experiments with comprehensive analysis and discussion. “Conclusion” concludes the study with a summary of contributions.

Vehicle dynamic model

A seven-degree-of-freedom vehicle model

The vehicle dynamics model establishes seven-degree-of-freedom (7-DOF) equations that govern longitudinal motion (x-direction), lateral motion (y-direction), yaw rotation (z-axis), and rotational dynamics of all four wheels27. The front-wheel steering configuration is shown in Fig. 1.

The equations for the longitudinal, lateral, and yaw motion of the DDEV are as follows:

Longitudinal Motion:

Lateral Motion:

Yaw Motion:

In the equation, m is the total vehicle mass,a, b are the distances from the front and rear axles to the center of mass, respectively. δ is front wheel steering angle; vx,vy represent the longitudinal and lateral velocities, respectively; β is the center of mass sideslip angle; γ is the yaw rate; Fxi, Fyi are the longitudinal and lateral tire forces, respectively; where i = 1,2,3,4 corresponds to the left front wheel, right front wheel, left rear wheel, and right rear wheel, respectively; d is the track width; Iz is the vehicle’s moment of inertia around the Z-axis.

Tire model

This study adopts the Dugoff tire model28 due to its reduced parameter requirements and simpler mathematics. This model calculates normalized tire forces for all four wheels and estimates the tire-road adhesion coefficient using readily measurable vehicle states. The force analysis schematic of the Dugoff tire model is illustrated in the Fig. 2.

For an individual wheel within the tire coordinate system, the longitudinal and lateral tire forces are formulated as follows:

where:

In the equations, µ denote the tire-road adhesion coefficient; Cx and Cy represent the tire’s longitudinal and lateral stiffness respectively; ε is the slip velocity influence factor quantifying slip ratio rate effects on tire forces; and L characterizes the nonlinear slip ratio dynamics.

The Dugoff tire model accepts three inputs: slip ratio λ, tire slip angle α, and vertical load Fz. To capture nonlinear force-slip relationships, the boundary parameter L is explicitly defined.

The normalized formulation of the Dugoff tire model is expressed as:

In the equations,\(\:{F}_{x}^{0}\),\(\:{F}_{y}^{0}\) denote the normalized longitudinal and lateral tire forces, respectively. These dimensionless forces are derived through Eqs. (9)– (11).

The calculation formula for the tire slip ratio is as follows:

In the above equation ,d denote the track width; ax and ay denote the longitudinal acceleration and lateral acceleration, respectively. ω denote the wheel angular velocity ;\(\:m\) denote the total vehicle mass; \(\:g\) denote the gravitational acceleration; \(\:{h}_{g}\) denote the height of the vehicle’s center of gravity; l denotes the wheelbase; l = a + b representing the distance between the front and rear axles ,\(\:{F}_{zi}\) denote the vertical force on each tire.

Linear two-degree-of-freedom vehicle reference model

The desired states for vehicle yaw and lateral motion are defined by a two-degree-of-freedom (2-DOF) bicycle model29 As illustrated in the Fig. 3. This simplified model neglects vertical, roll, and pitch dynamics while assuming constant longitudinal velocity. It thus provides a foundational framework for analyzing vehicle dynamics.

As shown in the figure, the forces and moments acting on the 2-DOF vehicle can be expressed as follows:

In the equation: m is the total vehicle mass, γ denotes the yaw rate, β denotes the center of mass sideslip angle,δ denotes the front wheel steering angle,a and b are the distances from the center of mass to the front and rear axles, \(\:{v}_{x}\) denotes the longitudinal vehicle speed,\(\:{F}_{yf}\) and\(\:\:{F}_{yr}\) are the lateral forces at the front and rear wheels, and \(\:{I}_{z}\) denote the vehicle’s moment of inertia.

Under normal conditions, the front wheel steering angle is small, so we can assume \(\:\text{cos}\delta\:\approx\:1\:and\:\text{sin}\delta\:\approx\:0\).Additionally, by neglecting the dynamic response process of the 2-DOF reference model, set \(\:\dot{\gamma\:}=0,\dot{v}=0\), therefore, the differential equations of motion for the 2-DOF vehicle are derived as follows:

In the equation, \(\:{k}_{f}\) and \(\:{k}_{r}\) represent the lateral stiffness of the front and rear tires, respectively.

By combining the 2-DOF model with the influence of the road adhesion coefficient, the reference value for the yaw rate \(\:{\gamma\:}_{d}\) can be derived as:

In the equation,\(K=\frac{m}{{{L^2}}}(\frac{a}{{{k_r}}} - \frac{b}{{{k_f}}})\) represents the stability index, \(\:L\) denotes the wheelbase,\(\:\lambda\:\) is the stability coefficient,\(\:g\) denotes the gravitational acceleration, and \(\:{\mu\:}_{peak}\) denotes the peak road adhesion coefficient.

From the perspective of overall vehicle safety and stability, in order to minimize the likelihood of vehicle instability, the ideal center of mass sideslip angle is chosen to be zero, i.e.:

Dynamic change detection-based unscented Kalman filter

The UKF is a nonlinear filtering algorithm that extends the Kalman filter framework, particularly suited for dynamic systems with nonlinear characteristics30. Unlike the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF), which relies on Taylor series expansions of nonlinear functions, the UKF directly approximates probability distributions through deterministic sigma point sampling and weighted summation. Its measurement update phase preserves the Kalman optimal update. The state-space representation of the nonlinear system is formulated as:

In the equation, z(k) denotes the output vector; x(k + 1) denotes the state vector at the next time step; w(k) and v(k) are the process noise and measurement noise, respectively.

For an n-dimensional state vector, the state estimate \(\:\widehat{x}\) and covariance matrix \(\:{P}_{x}\) represent the mean and covariance of all sigma points. The unscented transform generates sigma points \(\:{x}_{i}\) as:

Then, the weights for each sampling point in the sigma point set are calculated as follows:

where, \(\:{w}_{i}^{\left(m\right)}\) denotes mean weights for estimating posterior state means, while \(\:{w}_{i}^{\left(c\right)}\) represents covariance weights for recovering covariance matrices. The parameters are defined as: state dimension n primary scaling factor, α governing sigma-point distribution spread, kurtosis control parameter β\(\:\ge\:\)0 adjusting prior distribution shape, secondary scaling factor κ compensating higher-order errors, and composite parameter \(\:\lambda\:={\alpha\:}^{2}\left(n+\kappa\:\right)-n\).

Within the UKF estimation framework, a critical threshold θ is introduced to activate multi-sampling when detecting significant adhesion coefficient variations. This adaptive mechanism accelerates trend capture while improving estimation accuracy and real-time responsiveness. The detailed implementation workflow proceeds as follows:

Assume that the state estimate and covariance matrix at the previous time step are \(\:\widehat{X}\left(k-1\right)\)、\(\:{P}_{x}\left(k-1\right)\);

-

(1)

Set the initial values

-

(2)

Time Update

When k > 1, construct 2n + 1 sample points according to Eq. (17), i.e.:

Calculate the predicted sample points, i.e.:

Finally, calculate the mean and covariance of the predicted sample points \(\:{X}_{i}^{-}\), i.e.:

-

(3)

Measurement update

After obtaining the new measurement value z(k), update the state mean and covariance, i.e.:

In the equation, K denotes the filter gain matrix;\(\hat {x}\) is the cross-covariance; and \(\:\widehat{y}\) denotes the predicted value.

-

(4)

Threshold Evaluation

Compute the absolute difference between the current estimated road adhesion coefficient and the prior time-step estimate, i.e.:

Compare the absolute difference Δx with the predefined critical value θ:

If Δx > θ, the sampling period of the estimation algorithm is dynamically adjusted; If Δx < θ, the estimation is performed using the standard sampling period.

Regarding the θ threshold setting, an excessively large θ reduces system sensitivity to road adhesion coefficient variations, failing to promptly increase sampling frequency during significant adhesion changes. This compromises estimation timeliness and accuracy, potentially affecting vehicle stability control. Furthermore, simulation experiments were conducted by testing multiple thresholds (e.g., 0.05, 0.1, 0.15) to observe the accuracy and real-time performance of the estimation algorithm under different threshold values. The simulation results demonstrate that when the road adhesion coefficient changes abruptly, a threshold of 0.15 fails to estimate the adhesion change rapidly and accurately. This leads to a significant deviation between the adhesion coefficient received by the stability controller and the actual value, consequently compromising the effectiveness of the stability control algorithm.

Conversely, an overly small θ causes hypersensitivity, potentially triggering frequent dynamic updates under noise interference, thus resulting in decreased estimation stability and real-time performance. Therefore, this study tested multiple thresholds and evaluated their effects on accuracy and real-time performance. Based on the preceding analysis and test results, the θ threshold was set to 0.1.Dynamic Change Detection-Based UKF can perform more frequent sampling when significant changes in the adhesion coefficient are detected, allowing for faster capture of the changing trend.

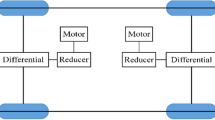

Hierarchical control strategy

Based on the stability requirements of DDEV, a hierarchical control architecture is designed using the center of mass sideslip angle and yaw rate deviation as inputs. The stability control strategy is shown in Fig. 4. The upper-level controller employs a neural network control algorithm based on the BA, to compute the additional yaw moment required for vehicle stability under the current state. The lower-level controller then takes the total driving torque of the vehicle and the additional yaw moment calculated by the upper-level controller as inputs. Using a quadratic programming algorithm, it optimizes the torque distribution across the four wheels.

This hierarchical control strategy effectively combines the vehicle’s stability requirements with the torque distribution problem. enhancing the stability and safety of the DDEV under complex road conditions by optimizing the torque output of each wheel.

In the Fig. 4, s denotes accelerator pedal opening; δ denotes steering wheel angle ;βref denotes the ideal sideslip angle at the center of mass; γd denotes the desired yaw rate ;β is the actual sideslip angle ;γ denotes the actual yaw rate; Δβ denotes sideslip angle deviation; Δγ denotes yaw rate deviation; µ denotes road adhesion coefficient. Mzd denotes the required stability yaw moment; T denotes wheel torque with subscripts fl., fr, rl, and rr corresponding to front-left, front-right, rear-left, and rear-right wheels respectively; Fx denotes tire longitudinal force; Fy denotes tire lateral force; v denotes vehicle longitudinal speed.

Bat algorithm-optimized backpropagation neural network control strategy

Traditional Backpropagation Neural Networks (BPNNs) utilizes gradient descent to update network weights and biases. However, gradient descent tends to converge to local optima, especially for complex nonlinear optimization problems, and often suffers from issue like slow convergence rates and vanishing gradients. The architecture of a standard backpropagation (BP) neural network is depicted in Fig. 5.

Bat algorithm

The BA is a nature-inspired intelligent optimization algorithm. Its core idea is to evaluate the quality of solutions using a fitness function and continuously adjust the position and velocity of the bats to reach the global optimal solution. Due to its simple model, fast convergence, and fewer parameters, it has been effectively applied in engineering optimization, model identification, and other problems31.

Compared to other meta-heuristic algorithms, the Bat Algorithm possesses exceptional balance between global and local search capabilities32. During the initial optimization phase, the algorithm tends to explore extensively within the global space, effectively avoiding premature convergence to local optima. As iterations proceed, it gradually shifts focus towards intensive search near the current best solution, thereby achieving rapid convergence to a high-precision solution. This characteristic is crucial for optimizing complex, high-dimensional, non-convex loss functions like those in neural networks, effectively overcoming the tendency of traditional BP algorithms to become trapped in local extrema. Furthermore, compared to algorithms such as the Genetic Algorithm, which requires setting parameters like crossover rate and mutation rate, or Particle Swarm Optimization, which necessitates adjusting inertia weight, social and cognitive factors, the BA has fewer core parameters. This makes the algorithm more robust and easier to implement.

The mathematical formulas used to simulate the flight and hunting process of bats are as follows. In an M-dimensional space, N bats are flying. The position of the i-th individual at time t is \(\:{x}_{i}^{t}\).and the velocity at time t is\(\:\:{v}_{i}^{t}\),The position at time t + 1 is \(\:{x}_{i}^{t+1}\),and the velocity at time t + 1 is \(\:{v}_{i}^{t+1}\),The state update formulas are given by Eqs. (25)–(27):

In the equations, \(\:{f}_{i}\) is the acoustic frequency of the bat at time t; \(\:{f}_{min}\) is the minimum acoustic frequency of bats at time t; β is a random number uniformly distributed in [0, 1]; \(\:{x}_{*}\) denotes the current optimal solution among all bats; \(\:{f}_{max}\) is the maximum acoustic frequency of bats at time t.

A random number rand is generated. If rand>\(\:{r}_{i}\), a random disturbance is applied to the current best solution \(\:{x}_{\text{*}}\),generating a new solution as follows:

A random number rand is generated again. If rand<\(\:{A}_{i}\) and \(\:f\left({x}_{i}\right)\le\:f\left({x}_{\text{*}}\right)\), then \(\:{A}_{i}\) and \(\:{r}_{i}\) are updated according to the following Eqs. (29) and (30):

In the equations, \(\:{R}_{0}\) denotes the initial pulse emission rate; \(\:{r}_{i}^{t+1}\) denotes the pulse rate of the i-th bat at time t + 1; α and γ are the pulse loudness attenuation coefficient and pulse emission rate increment coefficient, respectively, with 0 < α < 1 and γ > 0.

The fitness values of bats are sorted to identify the current optimal solution. Iterative updates are according to the BA’s workflow until predefined termination criteria are met, ultimately determining the globally optimal solution.

Bat algorithm-optimized backpropagation neural network model

The BA effectively addresses the limitations of traditional BPNN algorithms, such as susceptibility to local optima and slow convergence rates. The operational principle of the BA-optimized BPNN algorithm is as follows: The positional updates of bats in BA’s iterative optimization process correspond to adjustments in the BPNN’s weights and biases. The optimal bat position represents the optimal initial configuration of weights and biases, thereby preventing it from converging to local optima and enhancing both its learning capacity and computational efficiency. The fitness function employed in this BA optimization process is defined as:

In the equation, n denotes the number of learning samples, and \(\:{O}_{ih}\) and \(\:{T}_{ih}\) denotes the network output and the desired output respectively, for the h-th learning sample under the network structure determined by the bat i.

The specific implementation is as follows: the position of each bat is treated as the weights and biases of the BP neural network. The objective function of the BA is the sum of the absolute differences between the actual values and the network outputs. The best bat position found corresponds to the optimal initial weights and biases of the neural network.

-

(1)

Initialize the BP neural network by setting the number of layers, the number of neurons in the hidden layer and input layer, and establishing the corresponding neural network model. Then, initialize the parameters of the BA algorithm, including determining the bat population size m, the number of iterations N, the bat positions \(\:{x}_{i}\) and velocities \(\:{v}_{i}\), the sound wave frequency \(\:{f}_{i}\), the pulse loudness \(\:{A}_{i}\), and the pulse frequency ri.

-

(2)

Evaluate the current population using the fitness function Fitness(i), and record the individual best and global best solutions.

-

(3)

Update the velocity, echo frequency \(\:{f}_{i}\), and position \(\:{x}_{i}^{t}\) of the bat individual i using equations (25) to (27).

-

(4)

If the random number rand>\(\:{r}_{i}\), generate a new solution around the current global best position Then, use Eq. (28) to randomly generate a new individual and obtain the new individual position \(\:{x}_{new}\).

-

(5)

If rand<\(\:{A}_{i}^{t}\) and \(\:f\left({x}_{new}\right)<f\left({x}_{i}^{t}\right)\) (i.e., the new solution has a better fitness value), then accept the new solution. Then, adjust \(\:{A}_{i}^{t}\) and \(\:{r}_{i}^{t}\) according to Eqs. (29) and (30).

-

(6)

Determine if the maximum iteration count has been reached or if the termination conditions are satisfied. If so, proceed to the next step; otherwise, repeat steps (3) to (6).

-

(7)

Assign the global optimal position vector to represent the weights connecting the input layer to the hidden layer and the biases of the hidden layer neurons, as well as the weights connecting the hidden layer to the output layer and the bias of the output neuron.

-

(8)

Using the network with weights and biases set from global optimal position vector, perform standard BP training iterations on the training data. If the network’s accuracy meets the requirement, stop; otherwise, continue the BP training iterations until the target accuracy is achieved.

The implementation process of the BA-BP algorithm is shown in Fig. 6.

The article employs a standard single-hidden-layer BPNN architecture. According to Kolmogorov’s theorem, a single-hidden-layer neural network possesses the capability to approximate any continuous function. To determine the optimal number of hidden layer nodes, this paper conducted systematic sensitivity analysis experiments varying the node count. To prevent insufficient representation of the vehicle’s nonlinear dynamics characteristics and overfitting, while balancing prediction accuracy and computational efficiency, the hidden layer node number was ultimately selected as 10. The ReLU activation function was chosen due to its higher computational efficiency and better suitability for vehicle stability control.

To ensure controller effectiveness, the BA-BPNN model in this study was trained using extensive and diverse driving condition data (As shown in Table 1). The training data utilized systematically encompasses key variables affecting vehicle lateral stability. Firstly, in terms of driving maneuvers, it includes both sinusoidal and step steering inputs to simulate typical and extreme operations ranging from smooth cornering to emergency obstacle avoidance. Secondly, the road adhesion coefficient covers a continuous spectrum from low adhesion (µ = 0.2, simulating icy/snowy surfaces) to high adhesion (µ = 1.0, simulating dry asphalt), ensuring the controller’s adaptability to scenarios such as abrupt adhesion changes and split-µ roads. Furthermore, the vehicle speed range is extensive (35–125 km/h) to cover vehicle behaviors under different tire dynamics characteristics. Consequently, the dataset comprising 12,000 samples, collected via the Carsim/Simulink co-simulation platform, ensures the BA-BPNN learns fundamental vehicle dynamics principles rather than scenario-specific patterns.

The training data utilized the sideslip angle and yaw rate deviation as network inputs, with the additional yaw moment serving as the target output. A total of 12,000 effective sample data points were collected. Following standard machine learning practice, the dataset was partitioned into: a training set (8,400 samples), a validation set (1,800 samples), and a test set (1,800 samples).

Based on this dataset, Fig. 7 illustrates the variation of the Mean Squared Error (MSE) during the BA-BPNN training process, alongside a comparison with the classic Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm under identical conditions. Analysis indicates that the MSE of the Bat Algorithm decreases rapidly within the first 100 training epochs, with the rate of decrease slowing between epochs 100 and 180. Through multiple independent trials, the network was verified to converge on average around the 187th epoch (mean convergence epoch: 180 ± 30). In contrast, the PSO algorithm exhibits a rapid MSE decrease in the first 50 epochs, although the absolute MSE value remains relatively high at this stage, followed by a slow decline from epochs 50 to 250; it ultimately converges on average around the 250th epoch (mean convergence epoch: 250 ± 35, verified by multiple independent experiments). These comparative experimental results demonstrate that for the BP neural network training used in vehicle stability control in this study, the Bat Algorithm (BA) significantly outperforms the Particle Swarm Optimization algorithm in terms of both convergence speed and optimization efficiency. Although PSO shows a rapid error reduction trend in the early stages of training, its subsequent convergence speed plateaus, leading to lower optimization efficiency later on. Conversely, BA demonstrates more robust and efficient global search capability, enabling the network to achieve a superior performance state with fewer iterations.

Based on this convergence characteristic analysis and to ensure robust training under extreme conditions, the maximum number of training epochs in this study was set to 500. Concurrently, to optimize computational efficiency, an early stopping mechanism based on validation set performance was adopted (i.e., training was terminated prematurely if validation set performance ceased to improve). All subsequent simulation validations were conducted using an independent test dataset (i.e., non-training samples).

Torque distribution controller design

By applying quadratic programming theory, a torque distribution method based on optimization of tire load rates is adopted, integrated with the estimated road adhesion coefficient. The total longitudinal torque \(\:{T}_{cmd}\) and yaw moment \(\:{M}_{z}\), calculated by the upper-layer controller, are then distributed to individual wheels via electric motors. Quadratic programming typically addresses optimization problems with linear constraints, whose general formulation is as follows:

In the equation, H and f are the coefficient matrices, A, \(\:{A}_{eq}\), and b are the constraint coefficients, and UB and LB represent the upper and lower bounds of the variable x.

Optimization objective function

As established by tire dynamics principles29: a lower tire adhesion utilization rate corresponds to a higher reserve adhesion coefficient (i.e., a greater stability margin), which expands the wheel’s operational control range. During unstable vehicle operation, this increased margin enhances the system’s capacity to maintain stability. The tire adhesion utilization rate is mathematically expressed as:

In the equation, \(\:{\gamma\:}_{i}\) represents the tire utilization rate for each wheel; \(\:{F}_{xi}\),\(\:{F}_{yi}\), \(\:{F}_{zi}\) are the longitudinal force, lateral force, and vertical load applied to each wheel, respectively; and \(\:{\mu\:}_{i}\) is the road adhesion coefficient at each wheel.

From the above equation, the optimization objective function is formulated as minimizing the tire adhesion utilization rate. Its expression is given as:

To fully utilize the advantage of a distributed drive electric vehicles, which can directly measure drive unit parameters, and to neglect the effect of tire lateral forces on torque optimization, the optimization is performed by directly adjusting the tire longitudinal force This approach increases the lateral force margin while reducing the tire adhesion utilization rate, thus expanding the vehicle’s controllable range. The optimization objective function in this case can be simplified as:

Constraints

During tire force distribution, constraints ensuring normal vehicle operation must be considered. These include vehicle dynamics constraints, friction ellipse constraints, and actuator limitations. Consequently, the resultant tire forces must satisfy the vehicle’s operational demands, the constraint condition for the additional yaw moment and the vehicle’s maximum longitudinal driving force is as follows:

Furthermore, the maximum instantaneous torque that each wheel motor can output must be considered, leading to the following constraint:

Finally, the tire forces must satisfy the friction circle constraint, expressed as:

In the above equation,\(\:t=\frac{d}{2}\), where d denotes the track width, Rw denotes wheel effective rolling radius, Tmax denotes drive motor maximum torque,\(\:{\mu\:}_{i}\) is the road adhesion coefficient at each wheel.

Simulation experiment validation

Adhesion coefficient estimation algorithm simulation validation

To validate the effectiveness of the road adhesion coefficient estimation algorithm proposed in this study, a mixed scenario combining split-µ and alternating-µ road surfaces was selected for simulation. The algorithm’s efficacy was evaluated by comparing the estimated adhesion coefficients with the ground-truth road adhesion values. Vehicle parameters used in the simulation are summarized in Table 2.

For the dynamically varying road adhesion coefficient scenario, the vehicle speed is set to 80 km/h. At 5 s, the road adhesion coefficient for the left-side wheels changes from 0.4 to 0.85, while the right-side wheels transition from 0.85 to 0.4. At 3 s, a sinusoidal steering wheel input with an amplitude of 25° and a period of 4 s is applied to simulate cornering conditions. The simulation results of the four-wheel adhesion coefficient estimation are shown below:

A comparative analysis of the estimated adhesion coefficients of the left-front, right-front, left-rear, and right-rear wheels is presented in Fig. 8a–d, respectively.

The simulation results demonstrate that during variations in individual wheel adhesion coefficients, the estimated values exhibit minor transient fluctuations that do not compromise subsequent convergence stability or estimation speed. During the initial simulation phase, the front-left and rear-left wheels exhibit rapid convergence of adhesion coefficient estimates to 0.4, and subsequently converge to 0.85 within 0.5 s at t = 5s. Similarly, the right-front and right-rear wheels converge to 0.85 and 0.4, respectively, within the same timeframe. These observations confirm that the proposed Dynamic Change Detection-Based UKF effectively estimates the four-wheel road adhesion coefficients under dynamic adhesion variation, thereby strongly validating the algorithm’s reliability.

Simulation validation of vehicle stability control

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed stability controller under variable adhesion conditions, a Carsim-Matlab/Simulink co-simulation platform was established for comprehensive analysis. Comparative simulations were conducted between the average torque allocation strategy and the optimized torque allocation strategy developed in this study, with vehicle parameters consistent with those specified in preceding sections.

Steer-angle sinusoidal steady-state response simulation and analysis

The simulation employs a sinusoidal steering input to primarily analyze the vehicle’s steady-state response characteristics, evaluating stability performance during cornering on surfaces with dynamically varying adhesion coefficients. at t = 5s, the road adhesion coefficient for the left-side wheels changes from 0.4 to 0.85 while the right-side coefficient changes from 0.85 to 0.4. At t = 3s, a 45° sinusoidal steering input is applied. Comparative simulation results between the average and optimized allocation strategies are detailed in Figs. 9 and 10.

Figure 9a compares the vehicle sideslip angle curves under the optimized and average torque allocation strategies. At t = 3s (steering initiation), the sideslip angle increases significantly. At t = 5s (road adhesion coefficient transition), the amplitude variation under optimized allocation is significantly reduced compared to the average allocation. At t = 7s (steering wheel angle reset to zero), the sideslip angle under optimized allocation recovers to baseline within 0.3s, whereas recovery under average allocation requires 0.7s, The RMSE of the sideslip angle estimation was reduced by 12.4%.demonstrating the proposed strategy’s faster stabilization capability. Figure 9b illustrates the yaw rate tracking performance. The optimized allocation strategy accurately tracks the ideal yaw rate trajectory, achieving superior tracking accuracy compared to the average allocation. This confirms that optimized torque allocation significantly enhances stability during cornering under dynamic adhesion coefficient conditions.

Figure 10a shows the wheel output torque distribution under BA-BP stability control. At t = 5s, when the road adhesion coefficient changes, the system rapidly adjusts torque based on estimated adhesion conditions, ensuring enhanced stability during variable adhesion scenarios.

Figure 10b presents the vehicle speed curve under stability control with a target speed of 60 km/h. At t = 3s (steering input), the optimized allocation strategy demonstrates superior target speed tracking with smaller fluctuations, maintaining consistent speed during cornering under varying adhesion conditions.

Steer-angle step transient response simulation and analysis

The simulation under step steering input conditions primarily analyzes the vehicle’s transient response and testing its reaction capability when the driver applies a sudden large steering input in an extreme situation. The simulation conditions are defined as follows: the vehicle’s initial speed is 80 km/h, at t = 5s, the road adhesion coefficient for the left-side wheels changes from 0.4 to 0.85 while the right-side changes from 0.85 to 0.4. At t = 2s, a 60° steering wheel step input is applied. Simulations were performed for both the average allocation strategy and optimized allocation strategy. The results are shown in Figs. 11 and 12.

Figure 11a displays the sideslip angle variation curve under the following conditions: high-speed driving (80 km/h) on a surface with dynamically varying adhesion coefficients and a 60° step steering input. The results show that, within 0.7s of the steering input, under the optimized allocation strategy, the sideslip angle reaches a steady state within 0.7s, achieving a steady-state value of approximately 0.07 rad. When the road adhesion coefficient changes at the 5th second, the sideslip angle exhibits only minor transient fluctuations and promptly returns to its steady state. The RMSE of the sideslip angle estimation was optimized by 45.7%.In contrast, under the average allocation strategy, the sideslip angle begins to decrease gradually only after 1.5 s following steering angle variation, and fails to achieve steady-state throughout the simulation duration.

Figure 11b presents the yaw rate variation curve under the same conditions. Comparative analysis demonstrates that the optimized allocation strategy achieves superior vehicle stability. Specifically, the vehicle controlled by the optimized strategy exhibits faster transient response and enhanced disturbance rejection capability during adhesion coefficient transitions.

Figure 12a shows the four-wheel torque variation curves during a high-speed driving scenario at 80 km/h on a road surface with varying adhesion coefficients and a sudden 60-degree steering input. as shown, under this transient condition, the stability control system can rapidly calculates the required stabilizing torque for each wheel based on the estimated road adhesion coefficient, enabling stable vehicle operation under extreme conditions. Figure 12b presents the vehicle speed variation curve. The results demonstrate that compared to the average torque allocation strategy, the optimized allocation strategy exhibits smaller speed fluctuation amplitudes and enables faster tracking of the target vehicle speed.

Steady-state response simulation analysis of double lane change maneuver

The double lane change simulation primarily analyzes the vehicle’s dynamic stability and emergency obstacle avoidance capability. It is used to test the vehicle’s trajectory tracking ability and body attitude stability when the driver executes rapid, consecutive steering inputs (such as left-right or right-left) to simulate avoiding obstacles under extreme conditions. Therefore, the simulation scenario is defined with an initial vehicle speed of 80 km/h on a road with varying adhesion coefficients: the left-side road adhesion coefficient changes from 0.4 to 0.85 at the 5th second, while the right-side changes from 0.85 to 0.4 at the same time. Simulations were conducted for both the average allocation strategy and the optimized allocation strategy, with the results shown in Figs. 13 and 14.

Figure 13a shows the curves of the vehicle sideslip angle under the optimized allocation control and the average allocation control. At the beginning of the simulation, the vehicle initiates steering, and the road adhesion coefficient changes at the 5th second. The variation amplitude of the sideslip angle under the optimized allocation is significantly smaller than that under the average allocation. Around the 6th second, when the double lane change maneuver concludes, the sideslip angle under the optimized allocation control returns to a normal level more rapidly. Furthermore, the RMSE of the sideslip angle estimate is optimized by 31.9%. Therefore, the optimized allocation strategy stabilizes the vehicle faster than the average allocation strategy. In the yaw rate curve shown in Fig. 13b, the optimized allocation strategy almost perfectly tracks the ideal yaw rate, demonstrating a marked improvement compared to the average allocation. This capability significantly enhances vehicle stability during extreme continuous steering maneuvers.

Figure 14a represents the output torque of the vehicle under the designed stability control strategy. When the vehicle undergoes continuous steering and the adhesion coefficient changes, the system can rapidly adjust the torque based on the estimated road adhesion coefficient, thereby providing enhanced stability during continuous turning under dynamic adhesion conditions. Figure 14b shows the vehicle speed curves under both optimized and average allocation strategies, with a target speed of 80 km/h. During continuous steering maneuvers, the optimized allocation strategy demonstrates superior tracking of the target speed with minimal speed fluctuation, ensuring vehicle stability while cornering under varying adhesion coefficient conditions.

Conclusion

-

(1)

For scenarios involving changes in the road adhesion coefficient, a UKF estimation algorithm incorporating dynamic change detection was designed. When the adhesion coefficient varies, a critical threshold is implemented to rapidly estimate its change. This allows the vehicle to obtain accurate adhesion coefficient values promptly, enabling the stability control system to dynamically adjust torque distribution and enhance driving stability.

-

(2)

For the upper-level control system, a BP neural network-based stability controller and a speed tracking controller were designed utilizing the Bat Algorithm These controllers compute the total required driving torque and the direct yaw moment needed for vehicle stability. The lower-level controller then allocates torque to the four wheels based on the estimated road adhesion coefficient.

-

(3)

Simulations and experimental validations were conducted under normal steering and high-speed extreme steering conditions. The results confirm the effectiveness of the proposed road adhesion coefficient estimation algorithm and stability controller on roads with varying adhesion coefficients. The estimation algorithm quickly and accurately captures changes in the adhesion coefficient, while the stability controller significantly improves vehicle stability during extreme maneuvers on such surfaces.

-

(4)

The favorable modular design and adaptability of the stability control strategy and torque distribution method designed in the article suggest their potential for extension to different vehicle types and a wider range of road conditions. The stability control strategy developed in this study is applicable to most DDEVs. Furthermore, the designed UKF estimation algorithm primarily adjusts according to the real-time detected road surface attachment coefficient, and it is not inherently limited to a specific vehicle model. If the necessary vehicle dynamic signals can be acquired, this algorithm could be adapted to different vehicle platforms or different road conditions.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sun, X. et al. DYC design for autonomous distributed drive electric vehicle considering tire nonlinear mechanical characteristics in the PWA form. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 24 (10), 11030–11046 (2023).

Shen, T. et al. Stability analysis and control validation of DDEV in handling limit via SOSP: A strategy based on stability region. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. (2023).

Shen, T. et al. Stability and maneuverability guaranteed torque distribution strategy of DDEV in handling limit: A novel LSTM-LMI approach. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 27 (6), 5647–5658 (2022).

Liang, J. et al. A distributed integrated control architecture of AFS and DYC based on MAS for distributed drive electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 70 (6), 5565–5577 (2021).

LIU C. Stability control of distributed drive electric vehicles based on tire force prediction under ice-snow conditions. https://doi.org/10.27162/d.cnki.gjlin.2022.002481 (Jilin University, 2022).

Huang, Y. & Chen, Y. Vehicle lateral stability control based on shiftable stability regions and dynamic margins[J]. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 69 (12), 14727–14738 (2020).

Lin, F. et al. Coordinated longitudinal and lateral motion control for distributed drive electric vehicles with mechanical elastic wheels. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrification. 10 (1), 523–539 (2023).

Khaleghian, S., Emami, A. & Taheri, S. A technical survey on tire-road friction Estimation. Friction 5, 123–146 (2017).

Leng, B. et al. Estimation of tire-road peak adhesion coefficient for intelligent electric vehicles based on camera and tire dynamics information fusion. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 150, 107275 (2021).

Leng, B. et al. Tire-road peak adhesion coefficient Estimation method based on fusion of vehicle dynamics and machine vision. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23 (11), 21740–21752 (2022).

Li, C. et al. Road adhesion coefficient Estimation based on Vehicle-Road coordination and deep learning. J. Adv. Transp. 2023 (1), 3633058 (2023).

Wang, Q. et al. Estimation of road adhesion coefficient based on Sage-Husa adaptive filtering improved square root Cubature Kalman filter algorithm. Int. J. Heavy Veh. Syst. 31 (5), 641–664 (2024).

Wang, G. et al. Road adhesion coefficient Estimation by multi-sensors with LM-MMSOFNN algorithm. Adv. Mech. Eng. 15 (6), 16878132231183232 (2023).

Rongyun, Z. et al. Estimation of state parameters and road adhesion coefficients for distributed drive electric vehicles based on a strong tracking SCKF. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 238 (6), 1571–1588 (2024).

Zhang, G. et al. Tire–Road friction Estimation for Four-Wheel independent steering and driving EVs using improved CKF and FNN. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrification. 10 (1), 823–834 (2023).

Zhang, Z. Y. et al. State Estimation of distributed drive electric vehicles based on adaptive extended Kalman filter. J. Mech. Eng. 55 (6), 156–165 (2019).

Chen, X. et al. Longitudinal-lateral-cooperative Estimation algorithm for vehicle dynamics States based on adaptive-square-root-cubature-Kalman-filter and similarity-principle. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 176, 109162 (2022).

Su, L. et al. Platoon joint EKF for improved road friction estimation in autonomous platoons. IEEE Access (2024).

Kwang, C. S., Abdul Razak, S. F. & Yogarayan, S. Vehicle safety application through the integration of flood detection and safe overtaking in vehicular Communication. Civil Eng. J. 10 (9), 2997–3010 (2024).

Abdul Razak, S. F., Yogarayan, S. & Ullah, A. Preventing impaired driving using IoT on steering wheels approach. HighTech Innov. J. 5 (2), 400–409 (2024).

Abuzwidah, M. et al. Assessing the impact of adverse weather on performance and safety of connected and autonomous vehicles. Civil Eng. J. 10 (9), 3070–3089 (2024).

Zhang Z H. Research on anti-slip control for dual-motor four-wheel-drive electric vehicles. https://doi.org/10.27162/d.cnki.gjlin.2024.001394 (Jilin University, 2024).

Liu, C. et al. Multi-level coordinated Yaw stability control based on sliding mode predictive control for distributed drive electric vehicles under extreme conditions. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 72 (1), 280–296 (2022).

Gopinath, G. R. & Das, S. P. An extended Kalman filter based sensorless permanent magnet synchronous motor drive with improved dynamic performance. In IEEE International Conference on Power Electronics, Drives and Energy Systems (PEDES). 1–6, (IEEE, 2018).

Hongbo, W. et al. Road surface recognition based slip rate and stability control of distributed drive electric vehicles under different conditions. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 237 (10–11), 2511–2526 (2023).

LIANG X T. Key technologies for Longitudinal-Lateral motion coordinated control of distributed drive electric vehicles. Hefei Univ. Technol. 10.27 (2021).

Song T. Research on road adhesion coefficient estimation for hub-motor-driven electric vehicles. Harbin Inst. Technol. (2017).

Zhang, H. et al. Stability research of distributed drive electric vehicle by adaptive direct Yaw moment control. IEEE Access. 7, 106225–106237 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Estimation of road adhesion coefficient for four-wheel independent drive electric vehicle. 2020 5th International Conference on Mechanical, Control and Computer Engineering (ICMCCE). 2020 45–49 (IEEE, 2020).

Yang, X. S. A new metaheuristic bat-inspired algorithm. Nature Inspired Cooperative Strategies for Optimization (NICSO 2010). 2010 65–74. (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2010).

Esfandiari, A., Khaloozadeh, H. & Farivar, F. A scalable memory-enhanced swarm intelligence optimization method: fractional-order Bat-inspired algorithm. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybernet. 15 (6), 2179–2197 (2024).

Masood, M., Fouad, M. & Glesk, I. Proposing Bat inspired heuristic algorithm for the optimization of GMPLS networks 2017 25th telecommunication forum (TELFOR). IEEE 2017, 1–4 (2017).

Funding

Henan Provincial Department of Science and Technology, Key R&D Program of Henan Province, “Intelligent Electric Steering System for Pure Electric Commercial Vehicles: Key Technology Development and Industrialization”, 241111241800.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Z. and R.Y. designed the study, R.Y. and W.S. conceived the simulation, R.Y. and F.X analyzed the simulation results, R.Y drafted the paper, R.Y. and Z.Z. provided insights on the draft, F.X and Z.Z. revised the draft, all authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Z., Yang, R., Xu, F. et al. Real time dynamic adhesion coefficient estimation and BP neural network optimized lateral stability control for distributed drive electric vehicles. Sci Rep 16, 1265 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31029-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31029-7