Abstract

Early 2 factor (E2F) genes are transcription factors that interact with many DNAs and proteins. Studies have demonstrated that E2F genes can play an oncogenic role in different cancers, yet fewer have explored their effects on pan-cancers. In this study, E2F expression is systematically characterized in multiple types of cancer and its predictive value is determined. Several public databases (GEO, Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), cBioPortal, Kaplan–Meier Plotter and PrognoScan) were used to evaluate E2F genes differentially expressed between normal and tumor tissue in pan-cancer, we then investigated the correlation between expression levels of E2F and prognostic factors, clinicopathologic stage, gene mutation types, functional enrichment, drug sensitivity. This study also examined the relationship between microsatellite instability, tumor mutation burden, tumor microenvironment (TME), tumor-related immune checkpoint genes, and immunotherapy response as well as the expression of E2F. Then, we examined potential signaling pathways by analyzing gene set enrichment analyses (GSEAs). Finally, we performed the real-time PCR expression validation and in vitro functional experiments of E2F5. The expression of E2F was upregulated in most tumor tissues compared to adjacent normal tissues. The expression of E2F family genes was highest in E2F4 and lowest in E2F7 in 33 TCGA cancers. E2F gene expression correlates significantly with prognosis in multiple cancer types, as well as RNA-related stemness score and DNA-related stemness score, immune and stromal scores. The E2F genes expression also related with immune subtype in pan-cancer. There existed a positive correlation between E2F2 expression level and Dasatinib sensitivity, negatively related to drug sensitivity of Nelarabine, XK-469, Cyclophosphamide, etc. Pazopanib, Doxorubicin, and Paclitaxel sensitivity was all positively associated with E2F5 expression. E2F genes high expression group showed significant positive or negative enrichment in multiple tumor- and immune-related pathways. In addition, we also discovered that the expression level of nearly all E2F genes was positively or negatively correlated with objective responses to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 across multiple immunotherapy cohort. The immune infiltration analysis of specific bladder cancer further showed the significant relationships between E2Fs copy number variations or mutation status, and infiltration level of different immune cells. Furthermore, differential expression validation and in vitro phenotypic experiments indicated that E2F5 significantly promoted BCa cells proliferation and migration. According to these analysis and validation results, E2F genes are relevant to the occurrence and progression of various cancers, which may be biomarkers for tumor diagnostics and prognosis. The discovery of new therapeutic targets can lead to reshaping TME to promote tumor-suppressive metastasis rather than tumor-friendly metastasis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, cancer has become one of the greatest threats to the health of the public. In fact, the treatment of various cancers has been greatly improved. At present, cancer is treated primarily with surgical procedures, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and targeted therapies. The prognosis and survival rates of these therapies remain unsatisfactory despite some clinical success. In order to improve the outcome of cancers, further improvement is needed1. Pan-cancer targeted therapies, evidenced by Qiu et al.2, Lyu & Li3, and Zhang et al.4, not only elucidate core mechanisms of cancer initiation, maintenance, and progression but also pioneer precision medicine through decoding dynamic tumor microenvironment-driver gene network interactions. Identifying key tumor-associated genes is critical for developing prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets to advance precision oncology and improve patient outcomes. Contemporary multi-omics research integrates large-scale datasets—including immunohistochemistry, public gene expression repositories, and functional genomics—to robustly identify cancer driver genes and accelerate bladder cancer studies5,6. This framework is powerfully augmented by recent innovations: Singh and Malviya7 enhance cancer vaccine immunogenicity via DNA-based antigen delivery, revealing immune-related gene signatures; Paul8 establishes microRNA theranostics for integrated diagnosis and therapy, identifying non-coding RNA biomarkers; Li et al.9 links RNA m6A modification to tumor glycolytic reprogramming, exposing metabolic vulnerabilities; Dashtaki10 targets cancer stem cell-mediated drug resistance using CRISPR/Cas9, uncovering stemness-associated genes; and Qiong et al.11 delineates glycolytic enzyme alterations driving metastasis, highlighting prognostic indicators. Collectively, these advances synergize with multi-omics to decode complex gene networks, expediting clinically actionable target discovery for bladder cancer—where metabolic dysregulation and immune evasion are pivotal—and enabling combinatorial therapies against tumor heterogeneity and resistance.

During the 1980s, the early region 2-binding factor (E2F) transcription factor family was first identified as a transcription activator of adenoviral E2 gene promoter in adenoviruses, which consists of eight essential genes (E2F1, E2F2, E2F3, E2F4, E2F5, E2F6, E2F7, and E2F8), the DNA-binding domains of these proteins are highly similar, and they interact directly with consensus sequences12,13, apoptosis, cell proliferation, DNA repair, differentiation, and DNA replication are some of the processes it regulates. The E2F family is divided into activators (E2F1, E2F2 and E2F3A), canonical repressors (E2F3B, E2F4, E2F5 and E2F6) and atypical repressors (E2F7 and E2F8)14. It has been well established that members of the family regulate the cycle of cells. E2F family genes are implicated in the development and progression of multiple cancers due to mutations or functional changes, such as non-small cell lung carcinoma, urothelial carcinomas of the bladder, prostate cancer, glioma, ovarian cancer, breast cancer, colorectal cancer15,16,17. Nevertheless, the E2F gene has been extensively researched in only a few types of cancer15,18. Hence, it is urgent to examine E2F family genes across a wide variety of tumor types, there is still much to be learned about the biological functions and underlying molecular mechanisms of the E2F family genes as targets for therapeutic intervention in tumor progression. In this study, several E2F family genes was systematically analyzed and their prognostic impact on multiple cancer types was analyzed in-depth, the aim of this study is to investigate the relation between E2F family genes and pan-cancer immune cell infiltration, immune checkpoint genes, TMB, and MSI. Identification of new therapeutic biomarker may help to reshape TME, turning tumor activation into inhibition. Different tumor types were investigated for genetic mutations, immune microenvironment, functional enrichment, as well as immunotherapy response and drug sensitivity of the E2F family gene members. Analysis of these data could lead to the identification of a new biomarker and potential cancer-targeted therapies.

Materials and methods

Acquisition of data

Transcriptomes, mutations, and clinicopathological characteristics of 33 cancer types were acquired from the UCSC Xena database (http://xena.ucsc.edu). To ensure analytical reproducibility, we implemented rigorous data quality control: (1) RNA samples required an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) > 7.0; (2) Median sequencing depth was set at ≥ 30 million reads per sample; (3) Batch effects were corrected using the ComBat algorithm. During multi-database integration, all gene identifiers were standardized to the HGNC (HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee) symbol system to enable cross-platform comparability. We subsequently analyzed E2F expression differences between malignant tissues and adjacent normal counterparts through the TCGA pan-cancer dataset (https://www.cbioportal.org/). Prognostic associations of E2F family genes were validated using Kaplan–Meier Plotter (http://kmplot.com/analysis) and PrognoScan (http://www.prognoscan.org), with external validation datasets collated from GEO, ArrayExpress, and independent laboratory repositories.

Furthermore, in our ongoing single-arm phase II clinical study of tislelizumab combined with low‐dose nab-paclitaxel (TRUCE-01, NCT04730219) for muscle-invasive urothelial bladder carcinoma, the mRNA transcriptome sequencing data and clinical information of 29 cases, which included baseline 15 cancer tissues and 15 paired cancer tissues after immunotherapy, were acquired to explored the changes of E2Fs expression, and the statistical significance of differential expression was evaluated using the paired Wilcoxon test. According to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria, responders were defined as patients who had complete or partial responses (CR/PR) after immunotherapy; non-responders were those who had stable disease or progressive disease (SD/PD).

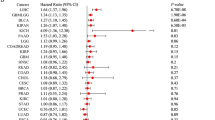

Survival analysis

Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan–Meier method to assess subgroup differences, while univariate Cox regression quantified associations between E2F gene expression and four clinical endpoints—overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), disease-specific survival (DSS), and disease-free survival (DFS)—across 33 pan-cancer cohorts. All Cox-derived p-values underwent Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction, with significance defined as FDR-adjusted q < 0.05. Significant associations were visualized using forest plots generated by the R package forest plot.

E2F mutation frequency, consequences on patient outcomes, and E2F expression correlations with CNV or SNV

The cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics (http://cbioportal.org) is a public database that stores many different kinds of data, such as somatic mutations, copy number variations, mRNA expression, DNA methylation, protein enrichment, and limited de-identified clinical data. The ICGC/TCGA Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes Consortium 2020 (2683 cases) from cBioPortal was used in this study to analyze the survival plots of patients with and without E2F alteration as well as the alteration frequency, mutation types, copy number variations (CNVs), and single nucleotide variations (SNVs) across TCGA cancer types.

Calculation of TMB, MSI, immune subtype and the expression of immune Checkpoints

We analyzed the correlation between E2F expression and MSI score, TMB score, TCGA immune subtype (i.e., C1 (wound healing), C2 (IFN-γ dominant), C3 (inflammatory), C4 (lymphocyte depleted), C5 (immunologically quiet), and C6 (TGF-β dominant)), expression levels of immune checkpoints (including PD-L1, PD-1, and CTLA4, etc.) using Spearman analysis.

Determination of immune microenvironment

To characterize the pan-cancer landscape of tumor immune microenvironments and E2F transcription factor activity, immune cell infiltration levels and E2F expression profiles were systematically quantified across all tumor cohorts. This analysis employed an integrated computational framework utilizing six established deconvolution algorithms: TIMER2.0 (v2.0; default marker gene sets from the Cistrome platform), CIBERSORTx, EPIC, MCP-counter, quanTIseq, and xCell. Each algorithm was executed strictly according to its published protocol and recommended parameter settings, as defined by the respective developers.

Drug sensitivity in pan-cancer

Drug sensitivity metrics were derived from dose–response curves fitted using nonlinear regression models (four-parameter logistic model) in GraphPad Prism, with a minimum coefficient of determination (R2) > 0.8 required for inclusion in downstream analyses. Gene expression and drug response data from the CellMiner database (https://discover.nci.nih.gov/cellminer) were preprocessed and normalized using Z-score transformation to enable cross-dataset comparability.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was performed to identify potential biological pathways and molecular functions associated with E2F family gene expression across pan-cancer datasets. A pre-ranked gene list was generated based on the log₂ fold change (log2FC) values derived from differential expression analysis between E2F-high and E2F-low expression groups, which served as the ranking metric for GSEA. The analysis was conducted using the GSEA software against the KEGG 2023 pathway database. The significance of enrichment was evaluated using false discovery rate (FDR) correction; FDR < 0.25 were considered significantly enriched, following the recommended guidelines from the Broad Institute.

E2Fs expression and clinical efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors

We picked IMvigor210, GSE111636, GSE78220, GSE67501, GSE176307 and our TRUCE-01 to analyze the correlation between E2F expression in bladder cancer, renal cell carcinoma, melanoma and the clinical efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors. The results were divided into Respond and Non-respond, statistically difference was set at p < 0.05.

RNA extraction and quantitative reverse transcription PCR

We used the E.Z.N.A.™ Hp total RNA Kit (OMEGA) for the extraction of total RNA from cell and tissue samples. cDNA was synthesized from RevertAid RT (Thermo). The qPCR was performed using SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (TaKaRa) with the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min; 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 10 s; annealing at 61 °C for 20 s and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. GAPDH served as endogenous control.For gene knockdown, cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 8 × 105 cells/well (70% confluency) 24 h prior to transfection. Transfection complexes were prepared by incubating 50 nM BMP8A-specific siRNA (Jima Gene, China) or negative control siRNA (NC) with Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher) in Opti-MEM (Gibco) for 15 min at RT. siRNA sequences were:E2F5-siRNA1, 5’- GGCUACAGCAAAGCAUCAATT-3’sense and 5’- UUGAUGCUUUGCUGUAGCCTT-3’ antisense; E2F5-siRNA2, 5’- GAGGUACCCAUUCCAGAAATT-3’sense and 5’—UUUCUGGAAUGGGUACCUCTT-3’ antisense; negative control (NC), 5’-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3’sense and 5’-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3’ antisense. After 6 h incubation, transfection medium was replaced with complete medium. Knockdown efficiency was confirmed 48 h post-transfection via RT-qPCR prior to functional assays19.

Cell proliferation assay

The cell lines were obtained from authenticated sources (ATCC), and their identities were verified based on morphology, growth rate, and consistent gene expression profiles during culture. Mycoplasma testing was routinely performed, and all experiments were carried out within 20 passages after revival. For the CCK-8 proliferation assay, BC cells were digested, resuspended to a concentration of 1.5 × 104 cells/mL, and seeded into 96-well plates at 100 μL/well (yielding 1.5 × 103 cells/well). Plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C under 5% CO₂ to ensure cell attachment. To assess proliferation kinetics, 10 μL of CCK-8 reagent (Boster Bio) was added directly to each well at designated time points (e.g., 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h post-seeding), followed by incubation at 37 °C for 2 h. Absorbance (OD) was quantified at 450 nm using a microplate reader. For the colony formation assay, approximately 800 transfected cells/well were seeded into 6-well plates and cultured for 8–14 days at 37 °C in 5% CO₂, with medium replenished every 2–3 days. Colonies were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at room temperature (RT) for 20 min, washed twice with PBS, stained with 0.5% (w/v) crystal violet in 25% methanol (RT, 20 min), and rinsed extensively with dH₂O. Colonies (> 50 cells) were manually counted or quantified using image analysis software (ImageJ)20.

Wound healing assay

BC cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 5.0 × 105 cells/well and cultured in complete growth medium (1640 medium + 10% FBS) until a confluent monolayer (≥ 90% coverage) was achieved. The monolayer was gently rinsed once with sterile PBS to remove debris. Using a sterile 10 μL pipette tip, one linear wounds were uniformly scraped across the well diameter, maintaining consistent pressure and angle. Wells were immediately rinsed twice with PBS to remove dislodged cells. Cells were incubated in low-serum migration medium (1640 medium + 1% FBS) for 24 h at 37 °C under 5% CO₂. Wound margins were imaged at 0 h (immediately post-scratch) and 24 h using an inverted phase-contrast microscope (Leica, Germany) at 40 × magnification. The migration rate of the cells was computed by applying the formula: [(scratch width at 0 h—scratch width at 24 h) / scratch width 0 h] × 100%21,22.

Statistical analysis

All statistical computations and visualizations were executed in R v4.3.1 . Continuous variables with non-normal distribution (assessed by Shapiro–Wilk test, p < 0.05) were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (e.g., E2F expression in tumor vs. normal tissues). Pairwise correlations (including TMB,MSI) were evaluated with Pearson correlation coefficients. To control false discoveries, P-values were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure with a false discovery rate (FDR) threshold of < 0.05 for all multiple comparisons.

Results

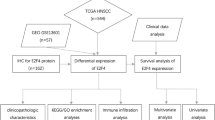

Expression of E2F family genes in pan-cancer

A detailed flow chart of this study is provided in Fig. 1. First, In comparison with normal tissues, a boxplot was used to describe the expression of E2F family genes across various cancers (Fig. 2A; Figure S1). According to Figure S2, each E2F family member is differentially expressed in cancerous tissues compared with noncancerous normal tissues. Pan-cancer analysis identified E2F1, E2F3, and E2F7-8 as consistently upregulated oncogenic drivers (elevated in 16–18 tumor types), while E2F4 showed broad but context-dependent activation. Tissue-specific suppression occurred in E2F2 and E2F6, with E2F5 alterations restricted to renal malignancies (Fig. 2B).

Gene expression levels and correlation of the E2F family in various cancer types from TCGA. (A) Expression of E2F family genes in various cancers. (B) Compared with expression in adjacent tissues, each E2F genes expression in different types of cancer based on TCGA data. In each small rectangle, red indicates significantly higher expression and green represents lower expression of the E2F family gene. (C) Correlation between E2F family genes. Blue dots represent positive correlation, while red dots represent negative correlation.

In pan-cancer patients, the E2F family genes show correlation or independence. According to further analysis, E2F1 is the most highly expressed in DLBC, E2F2 is the most highly expressed in THYM, and E2F3 is the most highly expressed in LAML, and E2F4 is the most highly expressed in READ, E2F5 is the most highly expressed in OV, E2F6 is the most highly expressed in GBM, E2F7 and E2F8 is the highest expressed in CESC. The present study also discussed the connection between E2F family genes (Fig. 2C). Correlations between E2F1 and E2F2 are most significant (correlation coefficient = 0.73); the correlation coefficients between E2F7 and E2F5 are the lowest (0.03).

Prognosis of E2F expression in pan-cancer

Elevated E2F expression correlated predominantly with adverse outcomes: in overall survival (OS), it predicted significantly poorer prognosis in 11 cancers (notably LIHC, KIRP, ACC, BRCA, LGG and LUAD; all log-rank p < 0.05) but unexpectedly better prognosis in THYM, READ, and UCS. This risk pattern extended to disease-specific survival (DSS), where high E2F levels were detrimental in 11 malignancies (including LIHC, KIRP, BRCA, and LUAD) yet protective uniquely in THYM. For recurrence-related endpoints, E2F overexpression consistently associated with reduced disease-free survival (DFS) in 8 cancers (LIHC, KIRP, PRAD, THCA, UCEC, SARC, LUAD, BRCA) and shorter progression-free survival (PFS) in 9 tumors (PRAD, LIHC, KIRP, ACC, LGG, KIRC, UVM, UCUE and LUAD). Strikingly, LIHC, KIRP and LUAD exhibited concordant hazard across all four endpoints (OS/DFS/PFS/DSS), suggesting E2F genes as core drivers of aggressiveness in epithelial tumors. (Supplementary File S1; Additional Data 1). It was shown in Fig. 3A that E2F expression correlated negatively with OS for most pan-cancers. There was a negative correlation between E2F1 upregulation and the survival rate in patients with ACC (p < 0.0001), KICH (p = 0.0001), and PCPG (p = 0.006), etc. Upregulation of E2F1 expression was associated with high survival rate in DLBC (p = 0.020), THCA (p = 0.007), and THYM (p = 0.039), etc. The DFS showed that E2F1 expression was significantly correlated with the prognosis of KIRP (HR = 0.19, p < 0.05), PAAD (HR = 0.65, p < 0.05), PRAD (HR = 3.90, p < 0.01), etc. (Fig. 3B). In Fig. 3C, it is shown that E2F expression is correlated with prognosis in pan-cancer patients, we can have the conclusion that E2F1 expression has a significant impact on ACC prognosis (HR = 2.35, p < 0.05), DLBC (HR = 0.14, p < 0.05), KICH (HR = 3.30, p < 0.05), etc. The PFS showed that E2F1 expression is significantly related to the therapeutic prognosis of KICH (HR = 2.67, p < 0.01), PCPG (HR = 2.98, p < 0.05), CHOL (HR = 2.07, p < 0.05), etc. (Fig. 3D).

The correlation between E2F expression and DSS, DFS, OS, and PFS. (A) Correlation between E2F expression and DSS in 33 tumors. (B) Correlation between E2F expression and DFS in 33 tumors. (C) Correlation between E2F expression and OS in 33 tumors. (D) The correlation between E2F expression and PFS in 33 tumors. Red: Overall Survival (OS), Yellow: Disease-Free Survival (DFS), Green: Disease-Specific Survival (DSS), Purple: Progression-Free Survival (PFS). HR > 1 indicates increased risk, HR < 1 indicates decreased risk. Non-significant results (p ≥ 0.05) remain uncolored.

The E2F family genes mutation analysis

This study is based on a whole genome sequencing of cancer (ICGC/TCGA, Nature 2020) (Fig. 4), The E2F gene family altered in 27.62% of 2683 cases in pan-cancer (Fig. 4A). It was found that 27 of 33 cancers had genetic changes affecting E2F family, and gene amplifications were the most common genetic modifications, Fig. 4B illustrate this. Additional mutations information of each E2F family member may be found in the Figure S3, respectively. Frequency of mutations in the E2F genes in Bladder Cancer (BLCA), Breast Cancer, Esophagogastric Cancer, melanoma (SKCM), Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, and Colorectal Cancer showed a relatively high mutation rate (more than 40%), and the other tumor types showed very low mutation rates (less than 40%). Overall, E2F family genes mutation rate ranges from 1.5% to 13% (Fig. 4C), with E2F5 having the highest frequency and E2F2 having the lowest frequency. Figure 4D indicates that wild-type patients had longer OS than Altered group (p = 0.0187). The Kruskal–Wallis test showed that E2F gene expression was positively correlated with copy number variation, it also suggests that shallow deletion of E2Fs are more prevalent. Additionally, pan-cancer patients were more likely to have amplifications and gains of E2F genes, as shown in Fig. 5A–H. We also observed that the non-mutated area accounted for a higher proportion than missense mutations and truncating mutations. A further analysis did not find any significant differences between SNPs and E2F expression levels (Figure S4).

A cBioPortal database analysis of genetic alterations in E2F genes in pan-cancer. (A) The types and frequencies of alterations in E2F genes. (B) Rectangular graph of the general mutation counts of E2F family genes in the pan-cancer atlas. The X -axis represents the cancer type of E2F family genes, the Y-axis represents the mutation frequency of E2F family genes. (C) OncoPrint summary of alteration on E2F family genes in 2683 numbers of samples of the pan-cancer atlas. (D) OS of E2F genes in altered and unaltered groups of various cancers.

Correlation of E2F expression and clinicopathologic characteristics

It is generally believed that patients with late tumor stages have a poor prognosis. In this study, we examined how E2F expression is related to clinicopathologic stage (Fig. 6A–H). E2F mRNA levels were significantly different between tumor tissues at different clinical stages. In most malignancies, E2F expression escalates progressively with advancing pathological stage, particularly in KIRC and KIRP. Conversely, a subset of tumors demonstrates paradoxical downregulation at advanced stages (Table S1). We also analysis the correlation of E2F expression and the treatment outcome of first course (Figure S5), the result indicates that some cancer types showed a significant association between the expression of E2Fs and the outcome after first treatment, for example, E2F1 expression was positively associated with CR/PR in the treatment of first course in DLBC, while the expression of E2F1, E2F2, E2F3, E2F6, E2F8 was associated with PD/SD in the treatment of first course in ACC.

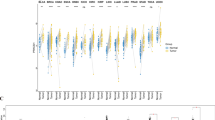

Relation between the expression of E2F family genes and immune subtype

The expression of E2F1-8 was associated with immune subtypes in 33 kinds of TCGA tumors (Fig. 7). E2F1, E2F2, E2F7 and E2F8 were upregulated in C2 immune subtype, E2F3 and E2F4 were upregulated in C1 immune subtype, E2F5 and E2F6 were upregulated in C5 immune subtype.

The correlation between E2F family genes expression and six immune subtypes across 33 cancer types from the TCGA. In this graph, the X axis indicates the immune subtype, and the Y axis indicates gene expression. C1, wound healing; C2, IFN-g dominant; C3, inflammatory; C4, lymphocyte depleted; C5, immunologically quiet; C6, TGF-β dominant. p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Correlation of E2F expression and stemness score, tumor immune microenvironment

Tumor microenvironment affects tumor occurrence and progression, which has been a pillar of tumor research for decades. It has great importance to understand tumor occurrence, development, and metastasis, Additionally, it also can be used to diagnose, prevent, and prognosis tumors. To investigate whether E2F gene expression correlates with immune infiltration, we investigated the TIMER2.0 database for correlations between E2F gene expression and three critical immune infiltration cells , including CD8 + T cells, T cell NK, and NK cells (Fig. 8A). The implication of these results is the expression of E2F genes was significantly associated with T-cell infiltration, NK infiltration, CD8 + T-cell infiltration, and NK cell infiltration in numerous cancers. The expression of E2F4 in BRCA is significantly correlated with the increase in immune cells, T cell NK, CD8 + T cells and NK cells inclued. The upregulation of E2F4 in HNSC-HPV + was correlated with a decrease in immune cells (T cells, NK cells, and CD8 + T cells). There was a significant correlation between the immune score and stromal score in pan-cancer tumor samples (Fig. 8B, C). Similarly, E2F family gene expression is significantly associated with RNAss and DNAss in pan-cancer (Fig. 8D, E).

Correlation of E2F genes expression with the infiltration level of immune cells and tumor microenvironment, Stemness score in pan-cancer. (A) Correlations of E2F expression with the infiltration level of immune cells across different cancer types. (B, C) Expression of E2F family genes in different cancers is associated with immune score and stromal score of TME. (D, E) The relation between the E2F family genes expression and RNAss and DNAss in various types of cancer. The red dots indicate that gene expression in the tumor correlates positively with the stromal score, while the blue dots indicate a negative correlation. DNAss, DNA stemness score; RNAss, RNA stemness score.

Correlation of E2F family genes expression and TMB, MSI as well as immune checkpoint genes

The use of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) may be beneficial for patients who with a high tumor mutation burden (TMB) or microsatellite instability (MSI)23,24,25. In the study, we explored the relation between TMB and MSI and E2F family genes expression. The result indicates that the expression of most E2F factors was positively correlated to TMB in pan-cancer (Fig. 9A, Figure S6), E2F1, E2F2, E2F3, E2F4, E2F5, E2F7 and E2F8 expression were negatively correlated with TMB in THCA. E2F family gene expression most positively correlated with MSI, while the expression of E2F2, E2F3, E2F5, E2F6, E2F7, E2F8 has a negative correlation with MSI in DLBC (Fig. 9B, Figure S7).

(A) Correlation between E2F expression and TMB in pan-cancer. (B) Correlation between E2F expression and MSI in pan-cancer. Red dots indicate a positive correlation, green dots indicate a negative correlation. *p < 0.05. (C) The Correlation heatmap of the E2F expression with immune checkpoint genes (PD-1,PD-L1, CTLA4) in pan-cancer. Red indicates a positive correlation, green indicates a negative correlation, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

In recent years, immunotherapy of tumors has gained significant attention as a crucial component of combined therapy. We extracted 3 important immune checkpoint genes to explore the relation of E2F expression and immune checkpoint genes. The result indicates that there is a positive correlation between E2F family genes expression and 47 common immunologic checkpoint genes (PD-1, CTLA4, PD-L1, ect.) in various TCGA cancers (Fig. 9C, Figure S8). The expression of E2F in BRCA, KIRC, and LIHC was positively correlated with the expression of various chemokines, the correlation was most significant in LIHC.

Drug sensitivity analyses of the E2F family genes

Our study was carried out using the CellMinerTM database to analyze the correlation of E2F family genes expression in diverse human cancer cell lines and drug sensitivity, Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to analyze the mRNA expression and drug activity of E2F family genes of 19 antitumor drugs in pan-cancer tissues (Fig. 10A). E2F1 expression was found to be associated with reduced sensitivity to Nelarabine, the high expression of E2F2 is positively associated with the drug sensitivity of Dasatinib but negatively related to the drug sensitivity of Nelarabine, XK-469, Cyclophosphamide, etc. And the sensitivity of XL-147, 5-fluoro deoxy uridine 10mer, Fludarabine, Karenitecin was found to be reduced by E2F4. The high expression of E2F5 enhanced the drug sensitivity of Pazopanib, the upregulation of E2F7 reduced the drug sensitivity of Simvastatin, the upregulation of E2F8 reduced the drug sensitivity of Nelarabine, indicating the increase of drug resistance. It can be seen from the Fig. 10B and Supplementary File S2 that E2F2 or E2F4 expression is separately positively associated with GI50 of carboplatin, oxaliplatin, and Gemcitabine (p < 0.05), while the E2F5 expression is negatively correlated with GI50 of paclitaxel and Doxorubicin (p < 0.05).

Analysis of the correlation between expression of E2F family genes and clinical immunotherapy efficacy in different data sets

Based on E2F expression levels, the patients were divided into two groups, high expression group and low expression group. A correlation between E2F family genes expression and immunotherapy responses of several independent cohorts (including IMvigor210 (n = 298), GSE111636 (n = 11), GSE78220 (n = 28), GSE67501 (n = 11), GSE176307 (n = 89) and our TRUCE-01 (n = 29)) (Fig. 11). Analysis of IMvigor_BC and GSE176307_BC dataset showed that the high expression of almost all E2F genes, particularly E2F1/3/8, was associated with good immunotherapy efficacy. Results from GSE111636_BC dataset revealed that E2F1 overexpression is critical positive with immunotherapy, as this data set with low sample size, it may suggest that high expression of E2F1 may be response for immunotherapy in pan-cancer. Upregulation of E2F6 has poor response to immunotherapy. Analysis of GSE67501_RCC data set indicates that the upregulation of E2F8 was positively related to the immunotherapy efficacy of RCC. Analysis of GSE78220_Melanoma dataset suggested that the expression of E2F gene family members had no correlation with Melanoma immunotherapy efficacy. For our TRUCE-01 dataset, the upregulation of E2F4 was positively related to resistance to immunotherapy of BC.

Apart from this, we also investigated the potential mechanism behind the expression of E2F genes and immunotherapy response. Our sequencing TRUCE01 results found that the expression level of E2F1/5/6/8 in bladder cancer cases with response to tislelizumab combined with nab-paclitaxel therapy significantly decreased after treatment (p < 0.05) (Fig. 12A–F). Interestingly, these results indicated that the molecular mechanism underlying these responses was significantly associated with the expression of E2F-familiy genes. This is also the part that we will continue to study in depth in the follow-up work.

GSEA analysis for investigating the potential mechanism of E2F family genes in bladder cancer

Aiming to understand how E2F family genes may influence tumor progression and prognosis, we divided all specimens into high and low expression groups according to their median gene expression levels, then used GSEA to identify the KEGG pathways enriched in each group (Figure S9, Supplementary File S3). The results show that a variety of immune-related and tumor-related pathways were enriched in each group. Regarding the KEGG terms, the top 5 pathways influenced by high expression of E2F genes were the neuroactive ligand receptor interaction, taste transduction, olfactory transduction, maturity-onset diabetes of the young, systemic lupus erythematosus, low expression of E2F1 activate the largest number of pathways (Valine Leucine and Isoleucine Biosynthesis, glucuronate interconversions and pentose, linoleic acid metabolism, ascorbate and aldarate metabolism) while low expression of E2F2, E2F4 and E2F6 did not activate any pathway.

Correlation among gene expression of the E2F family, Immune subtypes and clinicopathologic characteristics in BLCA

Analyses were conducted the correlation between E2F expression and clinicopathologic characteristics in BLCA (Fig. 13A). Among different age groups, there were no significant differences in E2F expression (age > 65, age ≤ 65). E2F3 and E2F8 expression levels were higher in male patients compared to female patients, the differences were statistically significant. The expression level of E2F4 in female tissue was higher than that in male BLCA tissue, and the difference was statistically significant. The expression of E2F1, E2F2, E2F6, E2F7, and E2F8 was higher in high-grade than in low-grade BLCA. Patients with lymph node metastasis had higher expression of E2F1, and the expression of E2F4 was higher in patients without lymph node metastasis, suggesting that E2F4 might be related to inhibiting lymph node metastasis. The expression of E2F4 in low-stage BLCA was higher than that in high-stage BLCA, suggesting that E2F4 may be related to the inhibition of tumor malignancy. E2F5 and E2F8 were upregulated in papillary tumors, the expression levels of E2F1 and E2F2 were upregulated in non-papillary tumors.

Relationship between expression of E2F family genes and the clinicopathological features of bladder carcinoma and molecular typing. (A) Correlation of E2F expression and Clinicopathologic Characteristics in Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma. (B) Expression levels of the E2F family genes in the BLCA. The X-axis and Y-axis represent immune subtypes and E2F expression levels, respectively. C1, wound healing; C2, IFN-g dominant; C3, inflammatory; C4, lymphocyte depleted; C5, immunologically quiet; C6, TGF-b dominant. p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Additionally, the relationship between E2F family gene expression and BLCA immune subtypes has also been studied (Fig. 13B). Our data suggest that the expression of E2F1-3 and E2F5-8 was correlated with immune subtypes in BLCA. E2F1, E2F2, E2F7 is upregulated in C2 immune subtype, E2F3 and E2F5 is upregulated in C4 immune subtype, E2F6 is upregulated in C1 immune subtype and C2 immune subtype, E2F8 is upregulated in C1 immune subtype.

Correlation between expression of E2F family genes and tumour stemness, immunological indicators in BLCA

Spearman correlation analysis shows that the high expression of E2F1, E2F2, E2F3, E2F5, E2F6 and E2F8 was associated with the increase of TMB in BLCA. E2F1, E2F5 and E2F6 were related to the increase of MSI in BLCA (Fig. 14). Upregulation of E2F1-8 was positively correlated with RNAss score, the upregulation of E2F1, E2F2 was negatively associated with the DNAss score, a positive correlation was found between E2F5 and E2F8 expression and DNAss scores. We also analyzed the Stromal score, Immune score, and ESTIMATE score of E2F family gene in BLCA, the upregulation of E2F3, E2F5, E2F6 and E2F8 was negatively associated with Stromal score, immune score and ESTIMATE score, and there was a negative association between Stromal score and E2F7 in BLCA.

Correlation between E2F family genes expression and immune infiltration in BLCA

We found that the expression levels of E2F family genes was positively associated with the increase of CD8 + T cell in BLCA (Fig. 15). To further clarify the potential mechanisms by which ANXA expression affects immunotherapy, we investigated the correlation between AXNA family gene copy numbers and common immune cells content. We found that E2F1 copy number variation had no effect on CD8 + T cell content in bladder cancer, Deep deletion of E2F4 results in decreased expression of CD8 + T cell, Arm-level Gain of E2F6 results in increased CD8 + Tcell expression, high amplification of E2F7 has a negative association with expression of CD8 + T cell, Arm-level Gain of E2F8 is negatively associated with expression of CD8 + T cell (Fig. 16A). The mutation of E2F6 is positively associated with the infiltration levels of NK cells resting in BLCA (Fig. 16B).

Immune cell infiltration of the E2F family genes in BLCA. (A) Correlation coefficient between E2F family gene expression and Immune cell (B-Cell, CD8 + TCell, CD4 + TCell, Macrophage, Neutrophil, Dendritic Cell). (B) Relationship between high and low E2F expression and immune cell infiltration, with a higher level in red (p < 0.05, log2FC > 1) and a lower level in blue (p < 0.05, log2FC > 1).

The biological function of E2F5 in bladder cancer cell lines

E2F5 expression was knocked down in T24 and 253 J-BV cells using specific siRNAs targeting E2F5. Due to the effectiveness of siRNA, the sequence was selected to silence E2F5 in this study; achieving knockdown efficiencies of 75% and 70% respectively (Fig. 17A). CCK-8 assay, clone formation assay and wound healing assay results revealed that E2F5 knockdown suppressed the cell proliferation, migration and invasion of T24 and 253 J-BV (Fig. 17B–D). Overall, these results indicated that E2F5 played a crucial function in BCa cell proliferation and migration.

The biological function of E2F5 in bladder cancer cell lines. (A) Verification of knockdown efficiency of E2F5 in T24 and 253 J-BV cells. (B) CCK-8 proliferation assay. (C) Clone formation assays for E2F5 knockdown in T24 and 253 J-BV cells. (D) Wound healing assays for E2F5 knockdown in T24 and 253 J-BV cells. NC, negative control vector; CCK-8, cell counting kit-8. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

Discussion

Numerous biomarkers and mechanisms related to ICI therapy sensitivity have been identified in the era of cancer immunotherapy, including biomarkers for prognosis. In recent years, more and more immunotherapy treatments have been applied to clinical practice. How to choose the patients who may benefit from immunotherapy has become a difficult clinical challenge. Some specific mutations have been proved to influence the response to immunotherapy26,27. For ICI therapy of cancers, TMB, MSI, and PD-L1 expression are known to be important biomarkers. As a result of the limitations of regular biomarkers, novel biomarkers still need to be explored further. E2F expression has been proved to be related to tumorigenesis and tumor progression, as well as tumor immunotherapy, in recent studies28,29,30,31,32,33. Consequently, this study investigated whether E2F family genes can be used as prognostic indicators and their role to play in tumor immunity, tumorigenesis.

We systematically analyzed the E2F family gene across 33 tumor types. We concluded that E2F genes play a universal and important role in the development and progression of cancers. We compared the expression levels of E2F genes in pan-cancers and their related normal tissues, found E2F gene was differentially expressed in different tumor tissues, with most genes being upregulated compared to normal tissues. Previous studies have shown that the E2F family orchestrates multifaceted oncogenic programs through paradoxical duality: E2F7 drives tumor progression by simultaneously repressing cell cycle inhibitors and accelerating G1/S transition34, while activating pro-metastatic cascades such as the SP1/SOX4/Anillin axis in hepatocellular carcinoma35 and EZH2-mediated PTEN silencing that hyperactivates AKT/mTOR signaling in glioblastoma36. This transcriptional reprogramming converges with E2F1’s distinct oncogenic functions, wherein E2F1 directly transactivates downstream effectors like MYBL2 and RAD54L to fuel DNA repair dysregulation and mitotic infidelity in ovarian cancer37, while concurrently reprogramming cancer metabolism via PDK1/PDK3-mediated inhibition of pyruvate dehydrogenase—inducing Warburg effect in colorectal cancer38. Mounting evidence indicates that elevated expression of E2F family genes generally correlates with adverse clinical outcomes across malignancies, as demonstrated by Wang et al.39 showing consistent associations between E2F upregulation and poor prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC). Specifically, multi-cancer cohort analyses reveal that E2F1 overexpression portends diminished overall survival (OS), disease-specific survival (DSS), and progression-free survival (PFS) in adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC), kidney chromophobe (KICH), and pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma (PCPG), while E2F3 elevation predicts inferior survival in seven tumor types including LIHC and PAAD. Paradoxically, despite their opposing transcriptional roles—E2F1 as a canonical activator versus E2F7 as a repressor—both exhibit significant negative correlations with OS/DSS/PFS in ACC, KICH, and PCPG. Such coordinated cooperation establishes an amplified oncogenic nexus: E2F7-mediated cell cycle deregulation creates proliferative advantage, whereas E2F1’s dual targeting of genomic stability and metabolic adaptation synergistically promotes tumor plasticity and therapy resistance, ultimately defining a high-risk transcriptional phenotype across epithelial malignancies.

Study proves that activation or expression of E2F1 in superficial bladder tumors indicates progression to invasive bladder tumors40. We found that the upregulation of E2F family members was significantly associated with late stage in multiple tumors. The expression of E2F1, E2F2, E2F6, E2F7 and E2F8 in high-grade BLCA was higher than in low-grade BLCA, suggesting that the upregulation of them was related to the increased degree of malignancy. Patients with lymph node metastasis had higher E2F1 expression, suggesting that E2F1 may be involved in lymph node metastasis. According to reports in the literature, mutations or abnormal expression of E2F4 result in cell-cycle control malfunctions and malignant tumors41, E2F4 overexpression causes tumors in transgenic mice, suggesting that it is an oncogene42, additionally, E2F4 program can be used to predict the progression of bladder cancer and the outcome of intravesical immunotherapy43. Our results support that the expression of E2F4 was upregulated in patients without lymph node metastasis, suggesting that E2F4 might be related to inhibiting lymph node metastasis. Compared to high-stage BLCA, the upregulation of E2F4 in low-stage BLCA suggesting that E2F4 may be related to the inhibition of tumor malignancy.

Tumor heterogeneity is a big challenge in the field of tumor therapy, which either directly affects the therapeutic target or influences drug resistance by defining transcriptome and phenotypic characteristics, thus shaping the tumor microenvironment (TME)44. Technological advancements have enabled us to gain a more profound understanding of the immune context of the tumor microenvironment, as well as its impact on treating it effectively. The reestablishment of the proinflammatory and immunogenic tumor microenvironment has become an increasingly attractive strategy for cancer treatment in recent years. The development of combined immunotherapies based on regulation mechanisms of the tumor immune microenvironment has broad potential. Studies have confirmed the potential predictive value of TMB and MSI as immunotherapy biomarkers45,46,47. Immune infiltration has been shown to determine therapeutic responsiveness and prognosis in cancer48—as evidenced by previous findings49: CD8 + T cells serve as core effectors of anti-tumor immunity, whose infiltration correlates with positive prognosis but function is suppressed by inhibitory pathways; NK cells directly eliminate tumors via NKG2D recognition of stress molecules under IL-15 regulation; and NKT cells contribute to innate immune regulation—all representing functional pillars of the TME landscape. Therefore, we examined the correlation of E2F expression and TME, MSI and TMB. We found strong relation between E2F expression and immune invasion, stromal score, MSI, and TMB in many tumors. For instance, the expression of most E2F genes was positively correlated with TMB in pan-cancer, while the expression of E2F1, E2F2, E2F3, E2F4, E2F5, E2F7 and E2F8 had negative correlation with TMB in THCA. E2F family gene expression most positively correlated with MSI, while the expression of E2F2, E2F3, E2F5, E2F6, E2F7, E2F8 was negatively correlate with MSI in DLBC.

There are several molecular mechanisms that regulate the expression levels of E2F family genes. In bladder cancer research, our analysis has revealed distinct regulatory mechanisms of E2F family members on immune checkpoint molecules: E2F1/E2F2/E2F6/E2F7 act as immune checkpoint activators showing significant positive correlations with PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA4 at varying degrees. Validation in immunotherapy cohorts further supports the E2F family’s role: Elevated expression of E2F1, E2F2, E2F6, and E2F7 was consistently observed in IMvigor210 responders (p < 0.01). Paradoxically, E2F8 functions as an inhibitory regulator, negatively correlated with PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA4. Notably, increased E2F8 levels were also detected in IMvigor210 responders. Current research lacks explanations for this contradictory role of E2F8.This demonstrates the the complexity of E2F8’s role. Further spatial transcriptomics and in vivo lineage tracing are warranted to resolve cell-type-specific functions.

Overall, these results suggested that by influencing TMB and MSI, E2F may play an important part in tumorigenesis, enhancement of T cell recruitment and infiltration into tumors as well as the regulation of immune checkpoints, affecting the prognosis of the patient in the end. In summary, we draw the conclusion that E2F can serve as a biomarker for assessing cancer prognosis. At last, the potential pathway activated by E2F genes in pan-cancer was evaluated by Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA), we were surprised to find that a variety of tumor or immune-related pathways were enriched.

Thus, a further investigation of this finding was performed in BLCA and the relationship between mutations in E2F family members and the abundance of TILs in BLCA was analyzed. The mutated E2F6 group had significantly higher abundances of NK cells. Additionally, a significant upregulation of PD-L1 expression was observed in patients harboring mutations in E2F6. Besides, the expression of E2F6 in high-grade and low-grade bladder cancer was significantly different, suggesting that the upregulation of E2F6 was related to the increased degree of malignancy. E2F1 promotes BLCA progression and poor prognosis through its modulation of the homologous recombination repair enzyme RAD54L, the expression level of E2F1 was significantly higher in the samples of patients with T3/T4 (late T stage) than in patients with T1/T2 (early T stage)50, it demonstrated that the E2F family genes play an critical role in the modulation of the TIME, Meanwhile, mutations in these members might affect ICI therapy outcomes by remodeling tumor immune microenvironment into the ICI-sensitive phenotype. Although this study leverages bulk tissue multi-omics data, emerging spatial and single-cell technologies could dissect E2F’s spatial context relative to genomic and epigenetic alterations. Future integration of these approaches may directly visualize E2F activation in tumor niches and determine whether it stems from local gene amplification or demethylation.

Overall, through our study, we were able to gain a better understanding of how E2F genes function in pan-cancer. Real time PCR verification and in vitro experiments confirmed that E2F5 functioned as an oncogene in bladder cancer. Nevertheless, the results need to be verified in a clinical setting. Building upon the synergistic potential of E2F family in modulating tumor-immune interactions, their combinatorial signature significantly enhances patient stratification for immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) response. To clinically validate this mechanism, we will initiate a multicenter phase II trial enrolling 120 bladder cancer patients. The trial employs a prospectively validated E2F Triad Classifier (E2F1/E2F2/E2F5)—integrating mRNA expression, protein levels, and epigenetic states —to predict ICI therapy response, with 1-year progression-free survival (PFS) as the primary endpoint. Herein, we convert descriptive biomarker correlates into an actionable molecular compass that identifies immunotherapy beneficiaries with the highest likelihood of profound clinical response.

Conclusion

Our study on the expression of the E2F family genes, from a systems-wide perspective of multi-omics and multi-datasets, suggested that most E2F genes were significantly upregulated in the various tumor tissues and were associated with clinicopathological features, clinical prognosis, TME, tumor drug sensitivity and stemness score in pan-cancer, including BLCA. Moreover, E2F genes, especially E2F1/3/4/8, has prognostic value in both standard treatment and immune checkpoint blockade therapy settings. Overall, E2F family genes may be further investigated considering these findings as important biomarkers and therapeutic targets in pan-cancer and may provide the basis for the development of predictive biomarkers.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Datasets supporting results of our paper are available in public database from TCGA and NCBI-GEO (GSE111636, GSE78220, GSE67501, GSE176307, IMvigor210). The raw sequence data of TRUCE01 are being uploaded to Genome Sequence Archive (GSA) database (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/search/?dbId=&q=PRJCA014405, accession number, ‘PRJCA014405’or ‘HRA005054’). The RNA-seq data for TRUCE01 are not currently publicly available. Data produced in research is possibly requested from corresponding author.

References

Chen, F. et al. Pan-cancer analysis of the prognostic and immunological role of HSF1: A potential target for survival and immunotherapy. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 1–21 (2021).

Qiu, J. et al. Pan-cancer analysis identifies AIMP2 as a potential biomarker for breast cancer. Curr Genomics. 24(5), 307–329 (2023).

Lyu, G. & Li, D. ZNF165: A pan-cancer biomarker with prognostic and therapeutic potential. Protein Pept Lett. 32(3), 206–223 (2025).

Zhang, Y. et al. Pan-cancer single-cell analysis revealing the heterogeneity of cancer-associated fibroblasts in skin tumors. Curr. Gene. Ther. 25(5), 793–821 (2024).

Loomans-Kropp, H. A. & Umar, A. Cancer prevention and screening: the next step in the era of precision medicine. NPJ. Precis. Oncol. 3, 3 (2019).

Xiao, Q. et al. High-throughput proteomics and AI for cancer biomarker discovery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 176, 113844 (2021).

Singh, A. K. & Malviya, R. DNA vaccines to improve immunogenicity and effectiveness in cancer vaccinations: advancement and developments. Curr. Gene Ther. 23(3), 170–183 (2023).

Paul, S. MicroRNA theranostics in cancer. Curr. Gene Ther. 23(5), 329 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. The role of rna m6a modification in cancer glycolytic reprogramming. Curr. Gene Ther. 23(1), 51–59 (2023).

Dashtaki, M. E. & Ghasemi, S. CRISPR/Cas9-based gene therapies for fighting drug resistance mediated by cancer stem cells. Curr. Gene Ther. 23(1), 41–50 (2023).

Qiong, L. et al. Recent advances in the glycolytic processes linked to tumor metastasis. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 17, e18761429308361 (2024).

Kent, L. N. & Leone, G. The broken cycle: E2F dysfunction in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 19(6), 326–338 (2019).

Chen, H. Z., Tsai, S. Y. & Leone, G. Emerging roles of E2Fs in cancer: an exit from cell cycle control. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9(11), 785–797 (2009).

Chen, H. Z. et al. Emerging roles of E2Fs in cancer: an exit from cell cycle control. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9(11), 785–797 (2009).

Oshi, M. et al. The E2F pathway score as a predictive biomarker of response to neoadjuvant therapy in ER+/HER2− breast cancer. Cells 9(7), 1643 (2020).

Marczok, S. et al. Comprehensive analysis of genome rearrangements in eight human malignant tumor tissues. PLoS ONE 11(7), e0158995 (2016).

Luo, H. et al. Early 2 factor (E2F) transcription factors contribute to malignant progression and have clinical prognostic value in lower-grade glioma. Bioengineered 12(1), 7765–7779 (2021).

Wang, J. P. et al. Rb knockdown accelerates bladder cancer progression through E2F3 activation. Int. J. Oncol. 50(1), 149–160 (2017).

Zhang, L. et al. Metabolomics-based approach to analyze the therapeutic targets and metabolites of a synovitis ointment for knee osteoarthritis. Curr. Pharm. Anal. 19(3), 222–234 (2023).

Ma, Z. et al. E2F1 reduces sorafenib’s sensitivity of esophageal carcinoma cells via modulating the miR-29c-3p/COL11A1 signaling axis. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 17, e060323214360 (2024).

Zeng, Q. et al. Hsa_Circ_0000021 sponges miR-3940-3p/KPNA2 expression to promote cervical cancer progression. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 17, e170223213775 (2024).

Peng, X. et al. MiR-129-2-3p inhibits esophageal carcinoma cell proliferation, migration, and invasion via targeting DNMT3B. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 16(1), 116–123 (2023).

Yu, G. et al. Tumor mutation burden, expressed neoantigens and the immune microenvironment in diffuse gliomas. Cancers (Basel) 13(23), 6092 (2021).

Scheiner, B. et al. Prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with immunotherapy - development and validation of the CRAFITY score. J. Hepatol. 76(2), 353–363 (2022).

Phillips, D. et al. Immune cell topography predicts response to PD-1 blockade in cutaneous T cell lymphoma. Nat. Commun. 12(1), 6726 (2021).

Hakimi, A. A. et al. A pan-cancer analysis of PBAF complex mutations and their association with immunotherapy response. Nat. Commun. 11(1), 4168 (2020).

Li, M. et al. KALRN mutations promote antitumor immunity and immunotherapy response in cancer. J. Immunother Cancer 8(2), e000293 (2020).

Luo, L. et al. Prognostic value of E2F transcription factor expression in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Med. Sci. Monit. 27, e933443 (2021).

Roelofs, P. A. et al. Characterization of the mechanism by which the RB/E2F pathway controls expression of the cancer genomic DNA deaminase APOBEC3B. Elife 9, e61287 (2020).

Liu, X. S. et al. Comprehensive analysis of prognostic and immune infiltrates for E2F transcription factors in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Front. Oncol. 10, 606735 (2020).

Jung, Y. D. et al. Lactate activates the E2F pathway to promote cell motility by up-regulating microtubule modulating genes. Cancers (Basel) 11(3), 274 (2019).

Julian, L. M. et al. Tissue-specific targeting of cell fate regulatory genes by E2f factors. Cell Death Differ. 23(4), 565–575 (2015).

Hollern, D. P. et al. The E2F transcription factors regulate tumor development and metastasis in a mouse model of metastatic breast cancer. Mol. Cell. Biol. 34(17), 3229–3243 (2014).

Zhao, Y. et al. MiR-424-5p regulates cell cycle and inhibits proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by targeting E2F7. PLoS ONE 15(11), e0242179 (2020).

Hao, F. et al. E2F7 enhances hepatocellular carcinoma growth by preserving the SP1/SOX4/Anillin axis via repressing miRNA-383-5p transcription. Mol. Carcinog. 61(11), 975–988 (2022).

Yang R, et al. E2F7-EZH2 axis regulates PTEN/AKT/mTOR signalling and glioblastoma progression. British Journal of Cancer, 2020. 123(9): p. 1445–1455. (Erratum in: British Journal of Cancer, 2025. 133(2): p. 272–273.)

Liu, X. et al. RNA m5C modification upregulates E2F1 expression in a manner dependent on YBX1 phase separation and promotes tumor progression in ovarian cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 56(3), 600–615 (2024).

Jing, Z. et al. NCAPD3 enhances Warburg effect through c-myc and E2F1 and promotes the occurrence and progression of colorectal cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 41(1), 198 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Integrated analysis of the E2F transcription factors across cancer types. Oncol. Rep. 43(4), 1133–1146 (2020).

Lee, J. S. et al. Expression signature of E2F1 and its associated genes predict superficial to invasive progression of bladder tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 28(16), 2660–2667 (2010).

Souza, R. F. et al. Frequent mutation of the E2F–4 cell cycle gene in primary human gastrointestinal tumors. Cancer Res. 57(12), 2350–2353 (1997).

Wang, D., Russell, J. L. & Johnson, D. G. E2F4 and E2F1 have similar proliferative properties but different apoptotic and oncogenic properties in vivo. Mol. Cell Biol. 20(10), 3417–3424 (2000).

Cheng, C., Varn, F. S. & Marsit, C. J. E2F4 program is predictive of progression and intravesical immunotherapy efficacy in bladder cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 13(9), 1316–1324 (2015).

Zhang, A. et al. Tumor heterogeneity reshapes the tumor microenvironment to influence drug resistance. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 18(7), 3019–3033 (2022).

Tang, Y. et al. PIK3CA gene mutations in the helical domain correlate with high tumor mutation burden and poor prognosis in metastatic breast carcinomas with late-line therapies. Aging (Albany NY) 12(2), 1577 (2020).

Zhang, C. M. et al. Role of deficient mismatch repair in the personalized management of colorectal cancer. Int. J. Environ Res. Public Health 13(9), 892 (2016).

Samstein, R. M. et al. Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat. Genet. 51(2), 202–206 (2019).

McGranahan, N. et al. Clonal neoantigens elicit T cell immunoreactivity and sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade. Science 351(6280), 1463–1469 (2016).

Gajewski, T. F., Schreiber, H. & Fu, Y. X. Innate and adaptive immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Nat. Immunol. 14(10), 1014–1022 (2013).

Mun, J. Y. et al. E2F1 promotes progression of bladder cancer by modulating RAD54L involved in homologous recombination repair. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21(23), 9025 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank all participants in the study.

Funding

This study was supported by Scientific Research Project of Tianjin Municipal Education Commission (grant no. 2022ZD069).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception/design: H Hu, and C Shen. Manuscript writing: S Yang, K Li, and Y Suo. Screening of the database and data collection: Z Zhang, H Chen, Y Lin, and C Fu. The bioinformatic analysis: C Shen, and Y Lin. Revision for this manuscript: H Hu, C Shen, Y Qie, and Z Zhang. Provision of critical comments: H Hu, and C Shen.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in strict compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The research protocol received formal approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Second Hospital of Tianjin Medical University (Approval No. KY2021K003). Written informed consent was obtained from all participating subjects prior to enrollment, and documentation is retained in the hospital’s ethics archives.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, S., Li, K., Suo, Y. et al. E2F transcription factors as multimodal biomarkers for pan-cancer management. Sci Rep 16, 1581 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31042-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31042-w