Abstract

Frequent failures of roadway anchor bolts in the roof-dripping zones of the Tashan coal mine endanger roadway stability and safety. To clarify the stress-corrosion cracking (SCC) mechanism and identify mitigation strategies, we combined water-chemistry analysis, multi-scale fractography, slow strain-rate tensile (SSRT) testing, and on-site anti-corrosion trials. Mine water showed weak alkalinity (pH 7.06–7.82), high mineralization (970–1980 mg L− 1), and elevated Cl⁻/SO42− suggesting strong pitting tendencies. Failed field bolts displayed limited necking, step-like fracture sections, and dendritic crack networks initiated at pits. SSRT tests in simulated solution revealed marked reductions in plasticity and strength compared to air; the SCC susceptibility index (ISCC), based on elongation, rose from 15.76% at 10− 3 s− 1 to 59.23% at 10− 7 s− 1, demonstrating greater SCC sensitivity at lower strain rates. SEM confirmed reduced dimples, deep pits, and reticulated cracking. A four-stage mechanism was proposed: pit initiation, crack nucleation via anodic dissolution under stress, occluded-cell-assisted propagation, and unstable fracture, often intergranular. Field trials with hot-dip-galvanized bolts showed intact surfaces and stable axial-force responses for over 30 days in dripping zones, confirming both barrier and sacrificial-anode protection. These results provide mechanistic insights and may offer practical guidance for improving corrosion-resistant anchor bolt design in aggressive underground environments, while recognizing that long-term monitoring and broader protective strategies remain necessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bolt anchoring support, as one of the core engineering technologies for the stability control of surrounding rock in coal mine tunnels, is widely applied in underground engineering construction under various complex geological conditions. Its primary function is to effectively transfer the shallow surrounding rock loads caused by excavation disturbances to deep, stable rock layers, forming an “anchor-rock joint load system”, thereby enhancing the overall stability, rigidity, and disturbance resistance of tunnel structures1,2,3. However, as the deep mining of coal resources progresses, the underground environment is characterized by a complex state of high ground stress, high temperature, high humidity, and highly mineralized water. The long-term coupling effects of corrosive ions (such as Cl−, SO42−), dissolved oxygen, and microorganisms lead to frequent failures of the supporting anchors during their service life, with stress corrosion cracking (SCC) being particularly prevalent. SCC is characterized by its strong concealment, rapid damage, and weak early-warning signals, posing a severe threat to the safe and efficient mining of deep mines4,5,6.

To address this issue, many scholars have conducted extensive research from the perspectives of corrosive environment characteristics, anchor mechanical responses, and corrosion damage testing methods, providing an essential foundation for understanding the failure mechanisms of anchors. In terms of corrosive environment research, Xiao et al.7 pointed out that the high concentrations of Cl− and SO42− in coal mine water are key factors in initiating pitting corrosion, perforation, and a significant reduction in the elongation of anchor bolts. Hossein et al.8 and Jin et al.9 further discovered through electrochemical tests and corrosion rate measurements that Cl− has a strong penetration ability and deactivation effect, easily forming a local acidic microenvironment on the steel surface, which causes the breakdown of the passivation film and induces severe pitting corrosion. SO42−, on the other hand, weakens the corrosion resistance of the steel by generating loose corrosion products with metal ions, and the synergistic effect of both significantly amplifies the corrosion risk. Li et al.10 emphasized the continuous amplification effect of acidic pits caused by corrosion product hydrolysis and the migration of Cl− on the stability of the pitting corrosion electrochemical cell and the corrosion depth. Regarding material and structural response, Kang et al.11 revealed the three-stage crack evolution process (nucleation-propagation-fracture) at the thread end based on fracture morphology and stress analysis, while Wu et al.12 argued that material toughness and internal processing defects dominate the fracture mode and fracture morphology. He et al.13,14 pointed out that the combined effect of geometric stress concentration and hydrogen-induced cracking is the key mechanism leading to SCC failure, based on experiments with galvanized bolts. Sun et al.15 demonstrated, from an electrochemical corrosion perspective, that hydrogen evolution reactions in acidic environments can cause hydrogen embrittlement damage to anchors, accelerating the failure process. In terms of experimental methods, Wang et al.16 used SSRT to study the evolution of plasticity and strength parameters of anchors in a high-stress-corrosion environment and established a strength degradation model. Chu et al.17,18,19 conducted systematic SSRT and pitting corrosion experiments in simulated high-mineralized water environments, confirming that hydrogen-induced cracking is the main damage mechanism, and pointed out that strain rate is highly correlated with anchor cross-sectional reduction and elongation. Feng et al.20 provided a systematic review of the indoor research status of corrosion damage and protection of mining anchors from a technical system perspective, pointing out that current research is mostly limited to laboratory accelerated corrosion tests and macroscopic performance assessments. There is a common lack of multi-scale micro-damage mechanism elucidation and a lack of on-site validation, making it difficult to comprehensively reveal the real failure mechanisms and protection effects of anchors in complex environments.

In conclusion, stress corrosion cracking of anchors, as a typical multi-field coupling failure problem controlled by a combination of corrosive environment, electrochemical reactions, mechanical stress states, and material structure, still lacks systematic research from a “macroscopic mechanical behavior-mesoscopic structural evolution-microscopic damage mechanism” multi-scale perspective, combined with engineering practice validation. Therefore, the aim of this study is to investigate the stress-corrosion failure mechanism of anchor bolts in Tashan coal mine using a multi-scale approach. This includes a characterization of the mine water chemistry, fractographic analysis of failed anchor bolts, SSRT testing to measure SCC susceptibility, and on-site validation of hot-dip galvanized anti-corrosion bolts.

Experimental program

Analysis of mine water composition at Tashan coal mine

Mine water is the primary source of corrosion medium in coal mines, and the high-humidity and oxygen-rich underground environment easily induces corrosion damage to metal components. The Tashan coal mine is located in a region with complex geological structures, where the roof rock layers mainly consist of weak strata such as clayey sandstone and shale, and the groundwater system is well developed, resulting in widespread water infiltration into the roof. The long-term high-humidity environment not only causes corrosion damage to underground equipment but also severely threatens the service stability of support structures such as anchor bolts. As shown in Fig. 1, anchors and anchor cables affected by corrosion exhibit significant rusting, leading to a substantial decrease in their bearing capacity. In severe cases, this can lead to tunnel support failure, endangering production safety.

To fully understand the corrosive characteristics of the mine water at Tashan coal mine, two typical water infiltration points in the roof were selected: 170 m in the No. 2311 tunnel of the Second Section and 700 m in the No. 5220 tunnel of the Third Section. Water samples were collected on-site for component detection and analysis. The ion concentrations and pH values of the mine water are shown in Table 1.

The results indicate that the mine water in the Tashan coal mine has high concentrations of Cl−, SO42−, and Na+ ions, demonstrating significant corrosive potential. Among them, Cl−, the most corrosive anion, has the highest measured concentration of 182.72 mg L− 1. The concentration of SO42− can reach up to 954.77 mg L− 1, which has the potential to induce film rupture and accelerate corrosion. Notably, the water samples from the Third Section show significantly higher levels of Mg2+ and Ca2+ compared to other areas, which may promote the formation and adhesion of corrosion products. In terms of acidity, the mine water is near-neutral to slightly alkaline overall, with pH values ranging from 7.06 in the Third Section to 7.82 in the Second Section (pH 7.06–7.82, slightly alkaline overall). Regarding mineralization, the Second Section has a mineralization close to 1000 mg L− 1, while the Third Section is as high as 1980 mg L− 1, indicating highly mineralized water.

From the corrosion mechanism perspective, Cl− has small volume and extremely strong penetration properties. It can preferentially adsorb on defects or weak points of the passivation film on steel, such as dislocations or inclusions, or directly penetrate the loosely bound film layer to reach the metal substrate. Cl− accumulates at the metal/passivation film interface, forming a high-concentration acidic microenvironment (e.g., Fe2++2Cl−→FeCl2), which leads to local acidification, causing the passivation film to break down. The breakage point becomes the anode, while the areas with intact passivation film become the cathode, forming a “small anode-large cathode” corrosion cell, triggering severe pitting corrosion. Pitting corrosion is one of the most dangerous forms of corrosion for anchors, as it develops rapidly and covertly, easily weakening the local cross-section until fracture. Although the corrosion effect of SO42− is typically weaker than that of Cl−, at high concentrations, it can also participate in the breakdown of the passivation film, especially in the presence of Cl−, where both ions may synergistically accelerate the initiation and development of pitting corrosion. SO42− can be reduced at the cathode (especially under anoxic conditions, where sulfate-reducing bacteria can utilize it) to generate more corrosive sulfur compounds (such as H2S, S2-). These sulfur compounds not only corrode the steel but also destroy any existing protective film and significantly increase the risks of hydrogen embrittlement and pitting corrosion. The combination of SO42− and corrosion-generated Fe2+ forms soluble salts or iron rust (containing sulfate components), which may be loose and porous, with poor adhesion, offering no effective protection and potentially exacerbating the stress concentration effect on the steel surface. Furthermore, due to volume expansion, this can lead to the detachment of the protective layer, triggering the initiation and propagation of stress corrosion cracks. In summary, the mine water at Tashan Mine, with its high concentrations of Cl−, high levels of SO42−, weak alkalinity (especially the Second Section approaching 8), and high mineralization, constitutes a highly corrosive environment that is a critical external factor contributing to the stress corrosion failure of anchors.

Macroscopic fracture characteristics of anchor bolts in service

During service, different parts of the anchor system are subjected to various external loads. The tail-threaded section of the anchor bears and transmits the circumferential load from the bearing plate, predominantly experiencing bending–tensile loads, whereas the free section is mainly subjected to axial tension or combined tension–shear loads induced by surrounding rock displacement. In a stress corrosion environment, the synergistic action of high stress and corrosive media significantly accelerates anchor bolt failure, resulting in fracture strengths far below the ultimate strength of the material, with the fracture surfaces exhibiting distinct features at failure.

To analyze the failure mechanism of anchor bolts under stress corrosion in the Tashan mining area, typical failed anchor samples were collected underground. Fracture sections from the tail-threaded and free sections were taken for macroscopic and microscopic morphology observations, as shown in Figs. 2 and 3. Figure 2 shows that neither type of fracture exhibited obvious necking; instead, the cross-sections displayed step-like morphologies with clearly visible shear lips at the edges, indicating a predominantly brittle fracture feature.

Using an ultra-depth optical microscope, the fracture surface morphology before and after rust removal was examined (Fig. 3). As shown in Fig. 3a and b, the fracture surfaces were uneven and irregular, with no evident necking. Mild oxidation corrosion was observed across the surfaces, accompanied by reddish-brown rust products. The rust on the thread-end fracture was relatively uniform and widespread, whereas in the free section the corrosion was concentrated along the ridge-like central area.

After removing surface rust, the fracture surfaces revealed typical stress corrosion features (Fig. 3c and d). In Fig. 3c, the right-hand edge of the thread-end fracture is identified as the crack initiation region, where corrosion pits induced by stress corrosion were present, reaching a depth of about one-quarter of the bolt diameter. The central part formed a radial zone with characteristic radial ridges; the crack propagation direction coincided with the radial lines and was perpendicular to the crack-source front edge. Shear lips were observed on the outer margin of the radial zone, opposite to the crack source. The asymmetric distribution of the three characteristic regions indicates that under the combined bending–tension load at the thread end, tensile stress concentration at the outer edge of the bolt initiated microcracks. Highly mineralized mine water in the crack channel continuously corroded and weakened the local metal microstructure. The crack gradually extended until the remaining cross-section could no longer sustain the applied load, at which point the crack propagated unstably, leading to fracture of the thread section with a typical stress corrosion fracture pattern.

Figure 3d shows the morphology of the free-section fracture. Multiple cracks extend from the outer edge toward the center, branching repeatedly during propagation to form a dendritic crack network. Corrosion pits on the outside of the crack convergence region mark the initiation sites of stress corrosion, while the central area constitutes the fibrous zone flanked by radial zones, giving the overall fracture a “radial-shear” pattern. This morphology indicates that the free section mainly endured pure tensile or combined tension–shear loads. Under high stress, the passive film on the metal surface was first destroyed, and the alkaline mine water further induced corrosion pit formation. Cracks propagated under tensile stress with increasing stress concentration, ultimately causing stress corrosion fracture failure of the anchor bolt.

SSRT test of anchor bolts under stress- corrosion environment

SSRT test method

To systematically evaluate the susceptibility of mining anchor bolts to stress corrosion cracking (SCC) in underground service environments of coal mines, SSRT were carried out in accordance with the requirements of “Corrosion of Metals and Alloys-Stress Corrosion Testing-Part 7: Slow Strain Rate Testing” (GB/T 15970.7–2017)21.

A precision electronic universal testing machine with servo-controlled loading and accurate strain-rate control was used as the loading device. A sealed corrosion cell containing the simulated mine-water solution was mounted at the machine center (Fig. 4a) to reproduce the near-neutral to slightly alkaline underground environment. The test specimens were machined from the base material of mining anchor bolts and strictly followed the geometric dimensions specified in Standard21, with a total length of 100 mm, a gauge length of 20 mm, and a rectangular cross-section of 3 mm × 2.5 mm (Fig. 4b). The anchor bolts were manufactured from a nominal 400 MPa yield-strength structural steel in accordance with the Chinese standard YB/T 4364 − 2014 Hot-rolled ribbed steel bars for rock bolts, where 400 MPa denotes the minimum specified yield strength of the grade. In this standard, the steel grade used in this study is designated MG400 and is required to satisfy yield strength ≥ 400 MPa, ultimate tensile strength ≥ 600 MPa, and elongation after fracture ≥ 16%. These properties are achieved in production through appropriate controlled rolling and/or heat treatment, which ensures a uniform internal microstructure and stable mechanical performance. The specified chemical composition (mass fraction, %) is C ≤ 0.25, Mn ≤ 1.60, Si ≤ 0.80, S ≤ 0.045, and P ≤ 0.045, with minor alloying additions permitted if necessary. Tensile tests on machined specimens taken from the production bolts yielded 0.2% proof strengths in the range 520–580 MPa, which is consistent with the manufacturer’s mill certificates and reflects the typical safety margin between the nominal strength class and the actual yield strength of production heats. Before testing, all specimen surfaces were sequentially ground with abrasive papers and cleaned with alcohol to remove surface defects, residual stresses, and contaminants.

The corrosion solution was prepared with deionized water and adjusted to pH 8 with NaHCO3 to simulate the typical water-dripping conditions in Tashan coal mine; its detailed ionic composition is given in Table 2. Four test conditions were designed, with each condition repeated three times to ensure data stability and reproducibility. The control group (SK-3) was tested in air at a strain rate of 1 × 10− 3s− 1to evaluate the baseline properties of the substrate material. The other three groups were polished and then tested in simulated mine water at strain rates of 1 × 10− 3s− 1(SR-3), 1 × 10− 5s− 1(SR-5), 1 × 10− 7s− 1(SR-7), respectively.

All tests were performed under constant strain rate loading until fracture. By comparing the tensile curves, fracture times, and fracture morphologies under different conditions, the SCC susceptibility and fracture mechanisms of mining anchor bolts in corrosive environments at different strain rates were systematically elucidated.

After testing, the yield strength, ultimate tensile strength, elongation, and reduction of area of the specimens were calculated. Based on the load–elongation curves, the characteristic parameters obtained in the corrosive mine water were compared with those obtained in air. The stress corrosion susceptibility index ISCC was calculated using Eq. (1):

where ISCC is the stress corrosion susceptibility index, I0 is the strength or plasticity parameter measured in air, and If is the corresponding parameter measured in corrosive mine water. A larger ISCC value indicates a greater difference between the tensile properties in the corrosive environment and those in air, implying higher stress corrosion susceptibility.

Mechanical properties from SSRT tests

The stress–strain curves of the anchor bolt specimens under different strain rates and environmental conditions are shown in Fig. 5. As illustrated in Fig. 5, the overall shape of the stress–strain curves for specimens tested in the stress corrosion environment was broadly similar to that of specimens tested in air, undergoing successive stages of elasticity, yielding, work hardening, and necking. However, the strain ranges corresponding to each stage exhibited significant differences.

Comparing specimens SK-3 and SR-3 (both at a strain rate of 1 × 10− 3 s− 1) shows that the corrosive environment had a pronounced effect on the mechanical performance of the anchor bolts, mainly reflected in the reduction of plastic strain during the hardening stage and the decrease in ultimate strength, while changes in the elastic and yielding stages were relatively small. This indicates that corrosion primarily weakened the plastic deformation capacity and ultimate load-bearing capacity of the anchor bolts.

Further comparison of the stress–strain curves for SR-3, SR-5, and SR-7 specimens reveals that as the tensile strain rate decreased, the yield strength of the anchor bolt specimens gradually decreased, and the strain ranges of the hardening and necking stages were significantly reduced, showing a tendency toward reduced ductility and increased brittleness. This is mainly because at lower strain rates the contact time between the specimen and the corrosive medium was longer, allowing more corrosion pits to form on the surface, which intensified stress concentration effects, thereby suppressing plastic deformation and increasing the risk of brittle fracture.

Additional phenomena were also observed during testing: at the beginning of loading the environmental solution was clear, but as loading time increased the solution gradually became turbid, and yellow or brown deposits formed at the bottom of the container. Meanwhile, obvious rusting appeared on the specimen surface. When the specimens reached the ultimate strength, sudden brittle fracture occurred without significant necking or any obvious warning signs.

The mechanical property parameters of the anchor bolt specimens in each group are summarized in Table 3. The data show that the yield strength, tensile strength, elongation after fracture, and reduction of area of the anchor bolts under the stress corrosion environment were all lower than those of the control group tested in air, and the extent of degradation of each parameter further increased as the strain rate decreased. Among them, the change in elongation was the most significant: the elongation of the anchor bolt specimens in air was 31.10%, while under the same strain rate (1 × 10− 3 s− 1) in the corrosive environment the elongation decreased to 26.20%; when the strain rate was reduced to 1 × 10− 7 s− 1, the elongation was only 12.68%. Because elongation reflects the material’s plasticity and energy absorption capacity, in this study elongation after fracture was selected as the primary indicator for evaluating the stress corrosion susceptibility of the anchor bolts. According to Eq. (1), the calculated SCC susceptibility indices ISCC are listed in Table 3. The results show that as the tensile strain rate decreased from 1 × 10− 3 s− 1 to 1 × 10− 7 s− 1, ISCC values were 15.76%, 40.77%, and 59.23%, respectively. This indicates that the lower the tensile strain rate, the higher the stress corrosion susceptibility of the anchor bolts and the greater the risk of stress corrosion cracking.

Fracture morphology observation of anchor bolts after SSRT

To further elucidate the fracture mechanism of anchor bolts under stress corrosion conditions at the microscopic level, the fractured specimens were retrieved after the SSRT tests, and the fracture sections were cut. The surfaces were cleaned using a hexamethylenetetramine-based rust remover. Subsequently, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed to observe and analyze the macro- and micro-morphologies of the fracture surfaces. Figure 6 compares the fracture morphologies of specimen SK-3 tested in air and specimen SR-7 tested in the stress corrosion environment.

As shown in Fig. 6a, specimen SK-3 fractured in air exhibited obvious cross-sectional contraction, displaying a typical ductile fracture morphology indicative of good plastic deformation capacity. The fracture surface was uneven with a distinct metallic luster, and the shear-lip, fibrous, and radial zones were clearly delineated, presenting the classic features of tensile fracture. Higher-magnification SEM images revealed a widespread distribution of equiaxed round dimples, characteristic of ductile microfracture.

In contrast, Fig. 6b shows that specimen SR-7 fractured under a weakly alkaline corrosive environment produced a generally flat fracture surface with a grayish appearance. The number of dimples decreased markedly, replaced by numerous corrosion pits with larger diameters and depths. The few remaining dimples were shallow and irregularly shaped, interspersed with the pits to form a “mud-crack” or reticulated pattern22-a typical feature of stress corrosion fracture morphology. This phenomenon indicates that at low strain rates the contact time between the anchor bolt and the corrosive mine water was extended, intensifying the corrosion effect, particularly around inclusions where corrosion tended to localize. This led to a rapid decline in the material’s plasticity and ultimately to sudden brittle fracture.

Failure mechanism of anchor bolts and anti-corrosion technologies

Failure mechanism of anchor bolts

By integrating the ionic composition and pH characteristics of the Tashan mine water with the preceding SSRT results and fracture morphology observations, a failure mechanism model of stress corrosion cracking (SCC) in anchor bolts is proposed. The process, illustrated in Fig. 7, can be divided into four stages:

-

(1)

Electrochemical Corrosion and Pitting Initiation Stage

The mine water in Tashan coal mine is weakly alkaline (pH 7.06–7.82) and contains high concentrations of Cl− and SO42−, creating a highly aggressive environment. Under long-term dripping conditions, the metal substrate of the anchor bolts undergoes the following electrochemical reactions:

Anodic reaction

$${\text{Fe}} → {\text{Fe}}^{2+} + 2{\text{e}}^{ - }$$(2)Cathodic reaction (oxygen reduction)

$${\text{O}}_{2} + 2{\text{H}}_{2} {\text{O}} + 4{\text{e}}^{ - } \to 4{\text{OH}}^{ - }$$(3)Chloride ions preferentially adsorb at defects in the passive film (γ-Fe2O3/Fe3O4) and penetrate the film via ionic migration, forming localized acidic microenvironments (Fe2+ + 2Cl− → FeCl2) that initiate pitting corrosion. The pits destroy the continuity of the passive layer and expose fresh metal substrate.

-

(2)

Crack Initiation Stage under the Synergistic Action of Stress and Corrosion

Under the combined effects of tensile stress and corrosion, anodic dissolution occurs at the bottoms of pits, which deepen progressively and form stress concentration zones. Axial tensile stresses induced by surrounding rock deformation mechanically rupture the metastable passive film, causing newly exposed metal to dissolve rapidly without re-passivation. With intensified localized corrosion, pits evolve into microcracks, forming crack initiation sites.

-

(3)

Crack Propagation Stage

Once microcracks are formed, corrosive mine water penetrates the crack channels and forms occluded cells. The crack tip region acts as an anode, where continuous Fe2+ anodic dissolution occurs, while the crack walls act as cathodes undergoing oxygen reduction reactions, together sustaining the corrosion current. Tensile stress accelerates the local dissolution rate at the crack tip, and the presence of Cl−and SO42− ions enhances the solution’s conductivity and ion migration rate, further speeding the process. Micrographs in Fig. 7 show: (a) the main crack penetrates deeply into the substrate in a wedge shape (depth > width); (b) secondary pits and branched cracks are distributed on both sides of the main crack; and (c) the branched cracks propagate approximately perpendicular to the main tensile stress direction, exhibiting typical SCC features.

-

(4)

Unstable Propagation Stage Dominated by Intergranular Fracture

Under the combined action of the corrosive medium (Cl−, SO42−, H+) and tensile stress, corrosive species infiltrate along grain boundaries, reducing grain boundary cohesion so that cracks preferentially grow along these paths. The connection of adjacent corrosion pits through branched cracks forms an expanding network, accelerating material fracture and ultimately leading to intergranular stress corrosion cracking (IGSCC).

In summary, the failure of anchor bolts in Tashan coal mine is essentially a typical “pitting–stress coupling” stress corrosion process, progressing through the four stages of “pitting initiation-crack initiation-propagation-brittle fracture.” This mechanism clearly reveals the root cause of sudden anchor bolt fracture in a high-mineralization, weakly alkaline environment, and provides a theoretical basis for the future optimization of anti-corrosion anchor bolt materials and the development of protective technologies.

Application of anti-corrosion technology for anchor bolts

Field test conditions

In response to the widespread stress corrosion problem of support materials in the roof-dripping areas of Tashan coal mine, which leads to anchor bolt failure and reduced bearing capacity of the surrounding rock, hot-dip galvanizing technology was introduced into typical roadways of the mine to provide anti-corrosion treatment for the existing support materials. This method operates on a sacrificial anode protection mechanism: a zinc layer is coated on the anchor bolt surface, and the zinc preferentially dissolves during electrochemical corrosion, thereby protecting the steel substrate. At the same time, the galvanized layer forms a dense and stable protective film on the anchor bolt surface, effectively isolating the corrosive mine water from direct contact with the steel, which significantly improves the service life and safety performance of the anchor bolts.

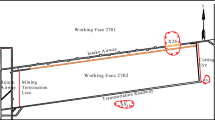

This anti-corrosion technology was deployed for field testing in two roadways (No. 2320 and No. 5320) of the 8320 working face in Tashan coal mine (see Fig. 8). The designed length of the 5320 roadway is 1760.819 m. The roadway adopts a rectangular cross-section and is driven along the coal seam floor, with a cross-section width × height of 5,500 × 3,800 mm and a net width × net height of 500 × 3,60 mm. The designed length of the 2320 roadway is 1576.314 m. This roadway also adopts a rectangular cross-section and is driven along the coal seam floor, with a gross cross-section width × height of 5800 × 300 mm and a net cross-section width × height of 5,800 × 3500 mm. The middle section of the roadway is overlain by the Kouquan River channel, where roof infiltration and dripping water are severe, representing a typical highly corrosive environment.

The roof support system was designed as follows: left-hand-thread ribless steel anchor bolts with a diameter of 22 mm, length of 2500 mm, and row spacing of 800 mm × 1000/2000 mm. Supporting SKP22-1/1860(F) anchor cables were used, consisting of Φ21.8 mm, 1 × 19-strand high-strength low-relaxation prestressed steel strands with a total elongation at maximum load of not less than 5.0%, and a cable length of 8300 mm. This combined scheme was implemented in the high-corrosion area for on-site comparative testing to verify the anti-corrosion effect of the hot-dip galvanizing process under actual mine conditions and its role in enhancing the stability of support performance.

Performance of anti-corrosion anchor bolts

In the 8320 working face, when the roadway advanced into the severely roof-dripping zone, the conventional anchor bolts specified in the original design were replaced with hot-dip galvanized anti-corrosion bolts, and their in situ support performance in the corrosive environment was evaluated by field monitoring. Axial forces in selected roof bolts and anchor cables were recorded over a two-month period from 1 May 2025 to 30 June 2025. Monitoring was conducted in two roadway sections: in the 2320 roadway, the test section extended from steel-strip No. 1270 to No. 1440, corresponding to a length of approximately 170 m, and in the 5320 roadway, from steel-strip No. 1036 to No. 1174, corresponding to a length of approximately 140 m. A GMY400W intrinsically safe anchor-bolt load sensor was installed on each instrumented support between the bearing plate and the nut, so that the measured load corresponded to the axial force transmitted through the plate–nut interface. The sensors were factory-calibrated in accordance with the relevant metrology standards; before installation, all units were checked and zeroed under unloaded conditions. During underground operation, axial-force data were automatically acquired at a sampling interval of one reading every 3 min. In total, axial forces were monitored on 10 roof bolts and 12 anchor cables in the monitored roadways of the 8320 working face. The resulting support performance after approximately 60 days of exposure is illustrated in Fig. 9.

A comparison of the apparent condition of the support components in Figs. 1 and 9 shows that the surfaces of the hot-dip galvanized anchor bolts exhibited virtually no rust and retained their metallic luster, whereas the adjacent ordinary steel straps had already developed obvious corrosion. This demonstrates that the hot-dip galvanizing technology was highly effective in isolating the corrosive medium and suppressing corrosion development, thereby ensuring the integrity and stability of the roof support system and preventing the adverse effects of the stress corrosion environment.

Load response monitoring results

To evaluate the actual effect of the anti-corrosion coating on the long-term service performance of anchor bolts, continuous mine-pressure monitoring was conducted for more than one month on both the anti-corrosion anchor bolts installed underground and uncoated anchor bolts of the same specifications. The variations in axial force of the anti-corrosion and uncoated anchors under identical operating conditions were compared (Fig. 10).

Load data of anchor-bolt/cables in the test section. a Load response of ordinary anchor bolts/cables in 2320 roadway, b Load response of anti-corrosion anchor bolts/cables in 2320 roadway, c Load response of ordinary anchor bolts/cables in 5320 roadway, d Load response of anti-corrosion anchor bolts/cables in 5320 roadway.

The monitoring data show that during this period the axial forces of both types of anchor bolts exhibited no significant differences and no obvious trend of mechanical performance deterioration. This phenomenon indicates that, within the current monitoring timescale (approximately one month after installation), although the uncoated anchor bolts had already begun to develop surface rust (e.g., flash rust or localized rust spots), the corrosion remained at an initial stage, mainly confined to the surface layer of the bolts. It had not yet penetrated deeply into the steel strands or caused substantial cross-sectional loss, and therefore had not materially weakened the overall load-bearing capacity, stiffness, or other core mechanical properties of the bolts.

By contrast, the hot-dip galvanized anti-corrosion anchor bolts showed no visible rusting during the monitoring period, demonstrating excellent corrosion resistance. Their load-bearing stability was superior to that of the ordinary products, further confirming their advantages and engineering applicability in corrosive environments.

Conclusions

-

(1)

The mine water at Tashan coal mine is weakly alkaline (pH 7.06–7.82) with high concentrations of Cl- and SO42- (up to 182.72 mg L-1 and 954.77 mg L-1, respectively) and a mineralization of 970–1980 mg/L, creating an aggressive environment prone to stress corrosion initiation.

-

(2)

SSRT tests demonstrated that anchor bolts in corrosive environments show significant reductions in plasticity and strength, with fracture modes shifting from ductile to brittle. As the tensile strain rate decreased from 1 × 10-3s-1 to 1 × 10-7s-1, elongation fell from 31.10% to 12.68% and ISCC increased from 15.76% to 59.23%, highlighting the pronounced enhancement of SCC susceptibility at lower strain rates.

-

(3)

Fracture morphologies revealed typical SCC features, including shallow dimples interspersed with deep corrosion pits, mud-crack-like microstructures, and intergranular propagation, supporting the four-stage mechanism of pitting initiation, crack initiation, crack propagation, and unstable brittle fracture.

-

(4)

Field tests with hot-dip galvanizing showed promising short-term protective effectiveness. After more than 30 days of monitoring in highly corrosive dripping zones, galvanized bolts exhibited no visible rusting and retained stable axial-force responses, suggesting their potential application in underground support systems.

-

(5)

Despite these insights, the study has limitations. The SSRT experiments were performed in laboratory-prepared simulated mine water, which cannot fully reproduce the complex underground environment including microbiological activity, fluctuating hydrochemistry, and variable stress states. The field trial monitoring period was relatively short (30–60 days), and thus the long-term durability of galvanized bolts remains to be verified. Moreover, only one anti-corrosion technology—hot-dip galvanizing—was examined, while alternative approaches such as alloy modification, composite coatings, or cathodic protection were not compared. Future research should address these aspects to establish a more comprehensive understanding of anchor bolt corrosion behavior and to evaluate diversified protection strategies for deep mining environments.

Limitations

While the present study provides useful insights into the SCC behaviour of anchor bolts under the investigated conditions, some limitations should be recognized when interpreting and generalizing the conclusions. The SSRT experiments were conducted in a laboratory-prepared simulated mine-water solution formulated to approximate the major ionic composition of the Tashan mine water, which cannot fully reproduce the spatial and temporal variability, microbiological activity, flow and renewal conditions, temperature fluctuations, and complex stress histories present in actual underground workings. The field trial was restricted to a single working face, a relatively short monitoring window (about 30–60 days), and a limited number of instrumented supports, so the long-term durability of the galvanized coating, potential cross-sectional loss of the steel core, and the coupled evolution of rock deformation and support performance remain unresolved. Moreover, only one anti-corrosion technology (hot-dip galvanizing) was evaluated, without comparison to alternative strategies such as alloy modification, composite or duplex coatings, or cathodic protection. Consequently, the quantitative results reported here should be regarded as indicative for the specific conditions investigated, and future research should extend monitoring to longer time scales and multiple sites under natural mine-water environments, while systematically comparing different corrosion-mitigation schemes to develop more general design guidance for corrosion-resistant support systems in deep mining environments.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. All key data supporting the findings are also included in this article and its supplementary information files.

References

Kang, H. P. & Gao, F. Q. Stress evolution and surrounding rock control in coal mines. Rock. Soil. Mech. Eng. J. 43 (1), 1–40 (2024). (in Chinese).

Li, Y. L., Dai, X. L. & Yang, R. S. Failure mechanism and support technology of weakly cemented soft rock roadway in water-rich environment. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 43, 213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-025-03163-6 (2025).

Hou, C. J. et al. Fundamental theory and technology of surrounding rock stability control in deep roadways. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 50 (1), 1–12 (2021). (in Chinese).

He, M. C. et al. Advances in rock mechanics for deep mining. J. China Coal Soc. 49 (1), 75–99 (2024). (in Chinese).

Guo, Q. F., Liu, H. L. & Xi, X. Experimental investigation of corrosion-induced degradation of Rockbolt considering natural fracture and continuous load. J. Cent. South. Univ. 30 (3), 947–961. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11771-023-5269-9 (2023).

Liu, S. W., Niu, S. & He, D. Y. Numerical simulation study on the effect of corrosion degree on the mechanical properties of mining anchor cables. J. Min. Strata Control Eng. 6 (5), 053020 (2024). (in Chinese).

Xiao, L., Li, S. M. & Zeng, X. M. Investigation of corrosion condition and mechanical performance of underground roadway support bolts. Rock. Soil. Mech. Eng. J. 2008 (S2), 3791–3797 (2008). (in Chinese).

Hossein, D. et al. Investigation of chloride-induced depassivation of iron in alkaline media by reactive force field molecular dynamics. Npj Mater. Degrad. 3, 19 (2019).

Jin, L. B., Liang, X. Y. & Wang, Z. Q. Corrosion rate of carbon steel under different chloride concentrations. Hot Working Technol. 50 (6), 39–42 (2021). (in Chinese).

Li, S. Q. & Du, Z. W. Review on corrosion of mine anchor bolts: factors, mechanisms and anti-corrosion technologies. Chem. Minerals Process. 53 (8), 62–72 (2024). (in Chinese).

Kang, H., Wu, Y. & Gao, F. Fracture characteristics in rock bolts in underground coal mine roadways. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 62, 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2013.04.006 (2013).

Wu, Y. Z., Chu, X. W. & Wu, J. X. Micro- and meso-scale experimental study on fracture failure of high-strength anchor bolts. J. China Coal Soc. 42 (3), 574–581 (2017). (in Chinese).

He, Z., Zhang, N. & Xie, Z. Z. Study on stress corrosion behavior and failure mechanism of galvanized bolts in complex coal mine environments. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 34, 1759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2024.12.173 (2024).

He, Z., Zhang, N. & Xie, Z. Z. Multi-scale experimental study on the failure mechanism of high-strength bolts under highly mineralized environment. Geomechanics and geophysics for Geo-Energy and Geo-Resources 10, 111 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40948-024-00824-3

Sun, J. F., Zheng, X. H. & Li, K. Scalable production of hydrogen evolution corrosion-resistant Zn–Al alloy anode for electrolytic MnO2/Zn batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 54, 570–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2022.10.059 (2023).

Wang, M., Zhu, S. T. & Li, S. D. Strength degradation mechanism and prediction of anchor bolts under deep high-stress corrosion environment. J. China Coal Soc. 49 (10), 4295–4310 (2024). (in Chinese).

Chu, X. W. Experimental study on corrosion rate of anchor bolts and anchor cables in simulated mine water. Coal Eng. 54 (12), 128–134 (2022). (in Chinese).

Chu, X. W., Ju, W. J. & Fu, Y. K. Study on pitting mechanism of threaded steel anchor bolts in highly mineralized mine water. J. Min. Sci. 6 (3), 305–313 (2021). (in Chinese).

Chu, X. W. et al. Experimental study on stress corrosion behavior of anchor bolts in highly mineralized mine water. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 52 (2), 255–266 (2023). (in Chinese).

Feng, F., Li, Y. P. & Wei, D. F. Current status and prospects of corrosion and anti-corrosion tests on underground mine anchor bolts. Nonferrous Metal Mines (4), 1–11 (2025). (in Chinese).

General Administration of Quality Supervision. Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China & Standardization Administration of China. Corrosion of Metals and alloys—Stress Corrosion testing—Part 7: Slow Strain Rate Testing: GB/T 15970.7–2017 (China Standards, 2017). (in Chinese).

Zhong, Q. P., Zhao, Z. H. & Fractography Higher Education Press, Beijing (2006). (in Chinese).

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

**All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by [Lei Wang], [Zhongwei Li] and [Xiang Xu]. The first draft of the manuscript was written by [Yukai Fu] and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, L., Li, Z., Fu, Y. et al. Multi-scale analysis of stress-corrosion failure and anti-corrosion strategies for anchor bolts in Tashan coal mine. Sci Rep 16, 1593 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31064-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31064-4