Abstract

Lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI) is a key prognostic factor influencing treatment decisions in endometrial cancer (EC). Here, we evaluate whether diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI)-based habitat imaging can noninvasively identify LVSI in EC. We retrospectively analyzed 101 EC patients who underwent preoperative multi-b-value DWI examination between December 2020 and October 2024. EC lesions were decoded into four habitats determined by unsupervised K-means clustering using true diffusion coefficient (D), perfusion fraction (f), and mean kurtosis (MK) maps, and the volume fractions of each habitat were quantified. LVSI-positive EC ( n = 22 ) exhibited significantly higher volume fractions of Habitat 1 ( H1 ) and lower volume fractions of Habitat 2 ( H2 ) compared to LVSI-negative cases ( p < 0.001 ). Logistic regression identified independent risk factors for LVSI, including H1, FIGO stage, and histologic grade. H1 demonstrated comparable diagnostic performance (AUC, 0.76 ; 95%CI: 0.67, 0.84 ) to pathological indicators, while achieving the highest sensitivity ( 81.82% ). Additionally, H1 correlated positively with tumor volume, while H2 correlated negatively with histologic grade. These findings suggest DWI-based habitat imaging could serve as a valuable preoperative tool for noninvasive LVSI assessment in EC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Endometrial cancer ( EC ) is the most common gynecologic malignancy in developed countries and the second most frequent among Chinese women1. Lymphovascular space invasion ( LVSI ), defined as tumor cell emboli within endothelial-lined channels at and beyond the invasive tumor margin, is an important prognostic factor associated with increased risks of lymph node metastasis, reduced progression-free survival, and overall survival2,3,4. As an independent risk factor for lymph node metastasis3, preoperative determination of LVSI status is crucial for surgical planning. It informs decisions on sentinel lymph node biopsy or sentinel lymphadenectomy for precise surgical staging and guiding adjuvant therapy, while avoiding unnecessary lymph node sampling to reduce intraoperative and postoperative complications5,6,7. However, in clinical practice, due to tumor heterogeneity and high sampling variability, LVSI status cannot be accurately assessed by preoperative biopsy; it can only be determined by pathological examination after hysterectomy8. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop preoperative strategies for accurately identifying LVSI.

Conventional preoperative MRI-based LVSI prediction utilizing morphological and quantitative features faces some limitations, including inconsistent reproducibility, low sensitivity, and substantial inter-observer variability9. Although recently developed MRI radiomics and deep learning models demonstrate promising diagnostic performance10,11, their whole-tumor analytical framework disregards intratumoral subregional phenotypic variations. Habitat imaging overcomes these constraints by identifying spatially distinct subregions ( known as “habitats” ) with similar pathophysiological characteristic, enabling precise quantification of tumor heterogeneity12. Recent studies have demonstrated the value of habitat imaging in predicting pathological risk factors, treatment response, and prognosis in various cancers, including breast cancer13,14, glioma15, and hepatocellular carcinoma16,17. However, no studies have explored the application of habitat imaging in the assessment of LVSI in EC.

Advanced diffusion-weighted imaging ( DWI ) models such as intravoxel incoherent motion ( IVIM ) provides information on microcirculation perfusion and water molecule diffusion within living tissues, while diffusion kurtosis imaging (DKI)offers insights into complexity of tissue microstructure18. We hypothesized that habitat imaging, constructed with quantitative parameters derived from IVIM and DKI (including the true diffusion coefficient, perfusion fraction and mean kurtosis), may hold promise for preoperative identification of LVSI. Therefore, the aim of this study is to evaluate the potential of DWI-based habitat imaging for preoperative noninvasive assessment of LVSI status in EC.

Methods

Patients

This single-center retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of China-Japan Union Hospital of Jilin University ( ID:2025031319 ). All procedures were conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Due to its retrospective nature, the requirement for obtaining written informed consent from patients was waived by the Ethics Committee of China-Japan Union Hospital of Jilin University.

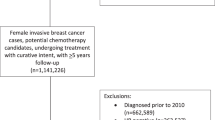

We initially enrolled 231 consecutive patients with histologically confirmed EC who underwent preoperative pelvic MRI, including multi-b-value DWI, within two weeks before surgery at our hospital between December 2020 and October 2024. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) maximum tumor diameter < 1 cm or no visible lesion on MRI; (2) poor image quality of multi-b-value DWI (e.g., severe motion artifacts or distortion caused by bowel gas artifacts); (3) incomplete histopathological information; (4) receipt of neoadjuvant therapy prior to surgery. Consequently, a total of 101 patients with EC were included in this study. The flowchart illustrating the inclusion and exclusion criteria is presented in Fig. 1. Clinical information and laboratory data for the included patients were retrospectively extracted from the hospital’s electronic medical records.

MRI acquisition

MRI examinations were performed using a 3.0T scanner ( Magnetom Skyra, Siemens Healthineers ) with an 18-channel phased-array surface coil covering the entire pelvic region. Prior to the examination, patients were instructed to empty their rectum and maintain a partially filled bladder. The MRI scanning protocol included the following sequences: sagittal and axial oblique (perpendicular to endometrial cavity) T2-weighted images(T2WI) without fat suppression; oblique axial T1-weighted images (T1WI); oblique axial T2WI with fat saturation; and oblique axial dynamic contrast-enhanced images.

The oblique axial multi-b-value DWI sequence was conducted using a spin-echo echo-planar imaging (SE-EPI) approach, enabling the simultaneous acquisition of IVIM and DKI data in a single scan. The acquisition parameters included TR/TE = 4700/96 ms, FOV = 228 × 228 mm2, slice thickness = 3.5 mm, matrix size = 114 × 114, and multiple b-values (0, 50, 100, 150, 200, 400, 800, 1200, and 1600 s/ mm2). The total scan time for the multi-b-value DWI sequence was 5 min and 45 s.

Image postprocessing

The multi-b-value DWI datasets were segmented into IVIM and DKI subsets using a custom MATLAB script (MathWorks, version R2021a), based on distinct b-value groupings. For IVIM analysis, seven b-values were utilized (0, 50, 100, 150, 200, 400, and 800 s/mm2), whereas DKI analysis incorporated five b-values (0, 400, 800, 1200, and 1600 s/mm2). Within the MITK-Diffusion software(v2014.10.02, http://mitk.org/wiki/MITK), all b-value images were rigidly registered to the b = 0 s/mm2 reference and denoised using a Non-local Means filter prior to parameter map fitting. Quantitative parameter maps for both IVIM and DKI were then generated.

The IVIM model employs a biexponential decay function to separate the contributions of diffusion and perfusion within each voxel. The model is mathematically defined as:

where S(b) denotes the signal intensity at a specific b-value, S0 represents the signal intensity at b = 0 s/mm2, f is the perfusion fraction, D is the true diffusion coefficient, and D* is the pseudodiffusion coefficient related to microcirculation.

The DKI model extends the conventional diffusion framework by accounting for non-Gaussian diffusion behavior, providing a more comprehensive characterization of tissue microstructure. The model is expressed as:

In this equation, S(b) represents the signal intensity at a given b-value, S0 is the signal intensity at b = 0 s/mm2, MD (mean diffusivity) quantifies the average diffusion rate, and MK (mean kurtosis) measures the degree of deviation from Gaussian diffusion, reflecting tissue microstructural complexity.

Lesion segmentation

Two radiologists, one with 3 years (J.L.L) and the other with 8 years (W.W) of experience in gynecological cancer MRI interpretation, independently performed freehand segmentation of the entire tumor volume on a slice-by-slice basis using DWI images (b = 800 s/mm2)in ITK-SNAP software (version 3.8.0, http://www.itksnap.org). By referencing T2-weighted and dynamic contrast-enhanced images, the radiologists meticulously avoided cystic, necrotic and hemorrhagic regions. The final volume of interest (VOI) was determined through consensus between the two radiologists and further validated by a senior radiologist with 15 years of experience (M.C.Z) in gynecological cancer MRI diagnosis.

Habitat imaging

The D, f, and MK parameter maps, along with their corresponding VOI masks, were imported into the nn FeAture Explorer software (version 0.2.5)19,20. We configured the software to operate in cohort-based mode, allowing for the aggregation of voxel-level data across the entire patient cohort for unsupervised K-means clustering. Prior to clustering, the voxel-wise values for each parameter (D, f, MK) were Z-score normalized across the entire patient cohort. The clustering utilized the Euclidean distance metric and relied on the software’s standardized implementation, which incorporates robust default settings for cluster initialization and stability to ensure reproducible results. The number of candidate habitats was set to 2, 3, 4, and 5 clusters, balancing biological interpretability and computational complexity. Clustering quality was assessed using the silhouette coefficient, with higher values indicating better clustering performance. Following the determination of the optimal number of habitats, the volume fraction of different habitats was quantified for every patient and expressed as Hn(%). The total fraction of all habitats for each patient summed to 100%.

Tumor volume measurement

In this study, two radiologists (J.L.L. with 3 years of experience and W.W. with 8 years of experience in gynecological cancer MRI interpretation) independently measured the tumor diameter (in centimeters) in three orthogonal planes21. Specifically, the anteroposterior (AP) and transverse (TR) diameters were measured on the oblique axial T2WI, while the craniocaudal (CC) diameter was measured on the sagittal T2WI. The average values of the measurements from both radiologists were calculated, and the tumor volume was estimated using the following formula: Tumor Volume = (AP× TR ×CC) / 2.

Histological analysis

All patients underwent total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Surgical pathological staging was performed according to the 2009 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO)guidelines. A pathologist (X.M.W.) with 10 years of experience in gynecological oncology retrospectively reviewed all pathological specimens on H&E-stained sections to re-evaluate the following features: histologic subtype; histologic grade (low-grade: grade 1 or 2; high-grade: grade 3 or non-endometrioid subtype); depth of myometrial invasion; cervical stromal invasion; LVSI status; and lymph node metastasis. LVSI was defined as the presence of tumor emboli within endothelial-lined spaces in the myometrium, located beyond the invasive tumor margin.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using MedCalc (v22.0; MedCalc Software) and SPSS (v29.0; IBM Corporation). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normality of continuous variables. Group comparisons for quantitative data were performed using the independent samples t-test (for normally distributed data) or the Mann-Whitney U test (for non-normally distributed data). Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages, with group differences analyzed using the chi-square (χ²) test or Fisher’s exact Test. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses with backward stepwise selection were conducted to identify risk factors associated with LVSI. Variables with p < 0.05 in univariate analysis were entered into the multivariate

analysis. Multicollinearity among the variables included in the multivariate logistic regression model was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was conducted to evaluate the diagnostic performance of risk factors for LVSI, with sensitivity and specificity calculated. Comparisons of AUC values were performed using DeLong’s test. Additionally, Pearson correlation or Spearman correlation was used to assess relationships between habitat volume fractions and clinicopathological risk factors.

Results

Patient characteristics

Among 231 consecutive patients who underwent surgery with preoperative imaging, 101 were ultimately included after excluding 32 cases with severe motion artifacts (n = 26) or distortion (n = 6) on multi-b-value DWI, 52 with MRI-invisible tumors or maximum diameter < 1 cm, 20 receiving neoadjuvant therapy, and 26 lacking complete histopathological information.

The final cohort (mean age: 57.6 ± 9.5 years) consisted of 22 LVSI-positive (21.78%) and 79 LVSI-negative (78.22%) patients. Significant differences were observed between LVSI-positive and negative groups in tumor volume (p < 0.001), serum CA125 levels (p = 0.011), FIGO stage (p < 0.001), depth of myometrial invasion(p < 0.001), histologic grade (p < 0.001), and histologic subtype (p = 0.006), while age showed no statistical significance (p = 0.650). Clinicopathological characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

Habitat imaging construction and intergroup comparison of habitat volume fractions

Clustering performance was tested for candidate habitat numbers of 2, 3, 4, and 5, with corresponding silhouette coefficients of 0.276, 0.263, 0.311, and 0.272. When the habitat number was set to 4, the silhouette coefficient reached its largest value (0.311). Therefore, each EC lesion was divided into four distinct habitats in this study. The four habitats exhibited distinct parameter profiles(Fig. 2): Habitat1: D = 0.699 ± 0.231 × 10− 3 mm2/s, f = 0.062 ± 0.022, MK = 1.256 ± 0.443; Habitat 2: D = 1.118 ± 0.390 × 10− 3 mm2/s, f = 0.067 ± 0.032, MK = 0.838 ± 0.306; Habitat 3: D = 0.618 ± 0.234 × 10− 3 mm2/s, f = 0.037 ± 0.019, MK = 0.315 ± 0.146; Habitat 4: D = 0.694 ± 0.206 × 10− 3mm2/s, f = 0.221 ± 0.067, MK = 1.072 ± 0.299.

Compared with the LVSI-negative group, the LVSI-positive group exhibited significantly higher volume fractions of Habitat 1 (H1) and significantly lower fractions of Habitat 2 (H2) and Habitat 4 (H4) (H1: median, 50.86%[IQR,43.87–55.79%] vs. 33.65%[IQR,13.42–46.59%];p < 0.001; H2: median, 7.06%[IQR, 4.30–11.70%] vs. 20.00%[IQR, 9.97–38.18%];p < 0.001; H4: median, 19.69%[IQR,15.59–25.42%] vs. 25.10%[IQR, 17.92–30.77%];p = 0.031). There was no significant difference observed in volume fractions of Habitat 3 (H3) ( p = 0.300) (Table 2). Representative habitat imaging was shown in Fig. 3.

Risk factors of LVSI and ROC analysis

Age, tumor volume, CA125 level, FIGO stage, depth of myometrial invasion, histologic subtype, histologic grade, H1, H2 and H4 were included in logistic regression analysis. Univariate analysis showed that tumor volume, FIGO stage, depth of myometrial invasion, histologic subtype, histologic grade, H1, and H2 were associated with LVSI (all p values < 0.05). Further multivariate analysis, adjusted for variables with p < 0.05 in the univariate analysis, revealed that FIGO stage (OR, 12.57;95%CI: 3.31,47.71; p < 0.001), histologic grade (OR,6.36; 95%CI: 1.50,26.96; p = 0.012) and H1 (OR, 1.05; 95%CI:1.02,1.09; p = 0.003) were independent risk factors for LVSI (Table 3). Multicollinearity assessment for this model confirmed the absence of significant collinearity, with all VIF values below 2.1 (range: 1.27–2.07).

ROC analysis demonstrated that H1 achieved an AUC of 0.76 (95% CI: 0.67, 0.84; cut-off, 42.32%) for identifying LVSI positivity, which was similar to the AUCs of FIGO stage (AUC, 0.78; 95% CI: 0.68, 0.85), histologic grade (AUC, 0.71; 95% CI: 0.61, 0.79), and the combined pathological indicators incorporating FIGO stage and histologic grade (AUC, 0.83; 95% CI: 0.74, 0.89). DeLong tests confirmed no significant differences between H1 and FIGO stage (p = 0.828), H1 and histologic grade (p = 0.471), or H1 and the combined pathological indicators (p = 0.396).

Furthermore, a comprehensive model that integrated FIGO stage, histologic grade, and H1 achieved a significantly higher AUC of 0.89 (95% CI: 0.81, 0.94). Its performance was superior to both the combined pathological indicators (AUC = 0.83; p = 0.022) and H1 alone (AUC = 0.76; p = 0.020).

Notably, H1 demonstrated the highest sensitivity (81.82% vs. 50-77.27%) in predicting LVSI positivity compared to individual risk factors and the combined pathological indicators. The diagnostic performance was summarized in Table 4; Fig. 4, with additional metrics for other individual habitats provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Comparison of ROC curves for various predictors of LVSI. The figure displays the predictive performance of the volume fraction of Habitat 1 (H1; AUC = 0.76), FIGO stage (AUC = 0.78), histologic grade (AUC = 0.71), the combination of FIGO stage and histologic grade (AUC = 0.83), and the comprehensive model incorporating all three factors (FIGO stage + histologic grade + H1; AUC = 0.89).

Exploratory analysis with a composite habitat score

Given the divergent trends of H1 and H2 observed between LVSI-positive and negative groups, a composite metric, the Habitat Risk Score (HRS), was calculated as H1(%) - H2(%). The HRS was significantly higher in LVSI-positive patients compared to LVSI-negative patients (median [IQR]: 43.79% [30.17–52.89] vs. 13.11% [– 21.95-31.32]; p < 0.001). In ROC analysis, HRS achieved an AUC of 0.78 (95% CI: 0.67–0.89) for predicting LVSI. However, its performance was not significantly superior to H1 alone (AUC = 0.76; p = 0.329).

Relation of tumor volume, FIGO stage, histologic subtype, histologic grade and habitat volume fraction

H1 showed statistically significant positive correlation with tumor volume (rho = 0.36, p < 0.001). H2 exhibited a weak negative correlation with histologic grade (rho = -0.20, p = 0.048), but no significant correlation with tumor volume (rho = -0.19, p = 0.059). No significant correlations were observed between H1 or H2 and FIGO stage or histologic subtype (Table 5).

Discussion

This study innovatively proposes a preoperative noninvasive approach for assessing LVSI in EC using DWI-based habitat imaging. Multivariate analysis revealed that an increased volume fraction of Habitat 1 (characterized by low diffusion, low perfusion, and high microstructural heterogeneity), advanced FIGO stage, and high histologic grade were independently associated with LVSI positivity. The volume fraction of Habitat 1 demonstrated high performance for identifying LVSI(AUC,0.76;95%CI:0.67,0.84), comparable to the diagnostic efficacy of FIGO stage, histologic grade, and the combined pathological indicators integrating FIGO stage and histologic grade. Critically, a comprehensive model integrating H1 with these clinicopathological factors achieved a significantly higher AUC of 0.89, confirming its additive predictive value. Importantly, the sensitivity of H1(81.82%) outperforms clinicopathological markers, highlighting its potential as a reliable and sensitive preoperative diagnostic marker for LVSI. This advancement aids in identifying high-risk patients who may benefit from sentinel lymph node biopsy, ensuring comprehensive surgical staging to guide adjuvant therapy and ultimately improving patient prognosis.

The selection of D, f, and MK parametric maps for decoding habitats was based on three critical considerations. First, the “one-stop” IVIM-DKI acquisition protocol ensures identical spatial resolution across all parametric maps. This approach avoids registration errors and voxel value distortions that may occur during multi-sequence co-registration, thereby enhancing the accuracy of habitat mapping. Second, these parameters provide distinct pathophysiological information, allowing for a comprehensive assessment of tumor heterogeneity in terms of cell density22, microcirculatory perfusion23, and microstructural complexity24. Third, prior studies have demonstrated the clinical value of these parameters in identifying histologic subtypes, grades, and risk stratification of EC25,26,27. These findings highlight their potential as biomarkers for tumor invasiveness, thereby supporting their application in habitat-based tumor analysis.

Based on silhouette coefficient analysis, this study ultimately decoded EC into four habitats with distinct pathophysiological characteristics. Univariate analysis revealed that an increased H1 (volume fraction of Habitat 1) and a decreased H2(volume fraction of Habitat 2) were associated with an elevated risk of LVSI. Specifically, a higher proportion of Habitat 1 with low diffusion, low perfusion, and high microstructural heterogeneity, and a lower proportion of Habitat 2 with high diffusion, moderate perfusion, and moderate microstructural heterogeneity, are linked to increased LVSI risk. This spatial association suggests that Habitat 1 may represent an invasive subregion associated with higher LVSI risk, while Habitat 2 may function as a protective subregion. Moreover, correlation analysis with clinicopathological factors showed that H1 was significantly positively correlated with tumor volume, while H2 was significantly negatively correlated with histologic grade. These results support the hypothesis that Habitat 1, as an invasive subregion, is linked to aggressive growth that leads to larger tumor size; whereas Habitat 2, as a protective subregion, is associated with well-differentiated tumors exhibiting indolent biological behavior. Similar conclusions have been drawn in previous studies, which found that LVSI-positive, high-grade and high-risk EC exhibit significantly lower D28, f29, and higher MK25. The presence of LVSI leads to dense tumor cell emboli within vascular channels, resulting in reduced perfusion. This compressed extracellular space restricts the free diffusion of water, leading to a lower diffusion coefficient. Additionally, reduced perfusion causes tumor cell hypoxic, necrosis, and extracellular matrix remodeling30, which could explain the observed increase in microstructural heterogeneity.

The predictive performance of H1 for LVSI was comparable to that of FIGO stage, histologic grade, and the combined pathological indicators of FIGO stage and histologic grade. Furthermore, a comprehensive model integrating H1 with these clinicopathological factors achieved a significantly higher AUC (0.89 vs. 0.83, p = 0.022), confirming its additive value. An exploratory Habitat Risk Score did not outperform H1 alone, reinforcing H1 as the most parsimonious predictor. Importantly, H1 achieved the highest sensitivity (81.82%), which is crucial for identifying high-risk patients for appropriate sentinel lymph node biopsy, thereby avoiding inadequate surgical staging and influencing adjuvant treatment decisions. Moreover, while high histologic grade is associated with increased LVSI risk31, accurate preoperative histologic grading via biopsy is challenging, with only 67% agreement between preoperative and postoperative histologic grading32. Therefore, our proposed preoperative noninvasive assessment of LVSI using habitat imaging holds substantial clinical value for optimizing treatment decisions and improving patient outcomes.

Additionally, in our study, the tumor volume in the LVSI-positive group was significantly larger than that in the LVSI-negative group, consistent with previous findings. Prior studies have also confirmed that tumor volume is an independent risk factor for LVSI and recurrence-free survival33. However, after incorporating habitat volume fractions into our analysis, tumor volume was no longer an independent risk factor. A possible explanation is that Habitat 1 represents a highly invasive subregion, and its volume fraction directly determines the invasive potential, rather than the overall tumor burden. The impact of tumor volume on LVSI may be an accumulated effect of Habitat 1. Therefore, habitat imaging, which quantifies high-invasive subregions, may help avoid the underdiagnosis of small but highly invasive tumors or reduce overtreatment of large but low-invasive tumors.

The development of diverse preoperative predictive models for the aggressive and pathological risk factors of EC represents a significant advance in personalized medicine. Valuable strategies have been established, including MRI-based radiomics models34 and clinically useful nomograms that integrate imaging signs with clinicopathological factors35. The field is further enriched by exploratory multi-modal approaches utilizing CT- 36and ultrasound-based radiomics37, which broaden the applications of quantitative imaging. While these methods provide crucial global risk assessments, their whole-tumor design overlooks the prognostic role of intratumoral spatial heterogeneity. Our study builds upon these important efforts by introducing a DWI-based habitat imaging framework designed to address this specific limitation. By mapping the voxel-wise heterogeneity of pathophysiological parameters (D, f, MK), our method allows for the identification of specific subregions that may be linked to aggressive behavior and LVSI, thereby complementing existing models by adding a layer of potential mechanistic insight into the spatial drivers of tumor aggressiveness.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the single-center, retrospective design and relatively small sample size, particularly the low number of LVSI-positive cases (n = 22), constitute a primary limitation. This resulted in a low events per variable (EPV) ratio in the multivariate model, increasing the risk of overfitting; thus, future validation in a larger cohort is essential. Second, the retrospective design may introduce selection bias. Particularly, the exclusion of MRI-invisible or small tumors (< 1 cm) could limit the generalizability of our findings, as the biological features and habitat profiles of these smaller lesions remain unexplored. Third, manual segmentation, though conducted via a rigorous multi-observer consensus approach, may introduce variability. Future integration of AI-based auto-segmentation is critical to mitigate this limitation. Fourth, our habitat imaging analysis employed a cohort-based rather than a per-patient clustering approach. While this method was necessary to establish a consistent definition of habitats across all patients for group comparisons, it may overlook individual variations in absolute parameter values. Therefore, exploring the value of patient-specific habitat definitions remains an important goal for future studies.

In conclusion, the DWI-based habitat imaging proposed in this study enables the quantification of different subregions within tumors. Its quantitative metrics can serve as potential noninvasive diagnostic biomarkers for preoperative identification of LVSI, demonstrating comparable accuracy and superior sensitivity to clinicopathological indicator. This highlights their substantial clinical application value in preoperative risk stratification for patients with EC, thereby facilitating more informed clinical decision-making.

Data availability

In order to protect the privacy of participants, the data sets generated and analyzed in this study cannot be made public, but are available from the corresponding authors if there is a reasonable request.

References

Crosbie, E. J. et al. Endometrial cancer. Lancet 399, 1412–1428. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(22)00323-3 (2022).

Han, L., Chen, Y., Zheng, A., Tan, X. & Chen, H. Prognostic value of three-tiered scoring system for lymph-vascular space invasion in endometrial cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol. Oncol. 184, 198–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2024.01.046 (2024).

Guntupalli, S. R. et al. Lymphovascular space invasion is an independent risk factor for nodal disease and poor outcomes in endometrioid endometrial cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 124, 31–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.09.017 (2012).

Tortorella, L. et al. Substantial lymph-vascular space invasion (LVSI) as predictor of distant relapse and poor prognosis in low-risk early-stage endometrial cancer. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 32, e11. https://doi.org/10.3802/jgo.2021.32.e11 (2021).

Solmaz, U. et al. Lymphovascular space invasion and positive pelvic lymph nodes are independent risk factors for para-aortic nodal metastasis in endometrioid endometrial cancer. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 186, 63–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.01.006 (2015).

Harris, K. L., Maurer, K. A., Jarboe, E., Werner, T. L. & Gaffney, D. LVSI positive and NX in early endometrial cancer: surgical restaging (and no further treatment if N0), or adjuvant ERT? Gynecol. Oncol. 156, 243–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.09.016 (2020).

Oaknin, A. et al. Endometrial cancer: ESMO clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 33, 860–877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2022.05.009 (2022).

Volpi, L. et al. Long term complications following pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer, incidence and potential risk factors: a single institution experience. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 29, 312–319. https://doi.org/10.1136/ijgc-2018-000084 (2019).

Meng, X. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of MRI for assessing lymphovascular space invasion in endometrial carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Acta Radiol. 65, 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/02841851231165671 (2024).

Gao, Y., Liang, F., Tian, X., Zhang, G. & Zhang, H. Preoperative risk assessment of invasive endometrial cancer using MRI-based radiomics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Abdom. Radiol. (NY). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-025-05005-8 (2025).

Wang, Y. et al. Fully automated identification of lymph node metastases and lymphovascular invasion in endometrial cancer from Multi-Parametric MRI by deep learning. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 60, 2730–2742. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.29344 (2024).

Li, S., Dai, Y., Chen, J., Yan, F. & Yang, Y. MRI-based habitat imaging in cancer treatment: current technology, applications, and challenges. Cancer Imaging. 24, 107. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40644-024-00758-9 (2024).

Chen, H. et al. Quantification of intratumoral heterogeneity using habitat-based MRI radiomics to identify HER2-positive, -low and -zero breast cancers: a multicenter study. Breast Cancer Res. 26, 160. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-024-01921-7 (2024).

Wu, J. et al. Intratumoral Spatial heterogeneity at perfusion MR imaging predicts Recurrence-free survival in locally advanced breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Radiology 288, 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2018172462 (2018).

Moon, H. H. et al. Prospective longitudinal analysis of physiologic MRI-based tumor habitat predicts short-term patient outcomes in IDH-wildtype glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 27, 841–853. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noae227 (2025).

Zhang, Y., Chen, J., Yang, C., Dai, Y. & Zeng, M. Preoperative prediction of microvascular invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma using diffusion-weighted imaging-based habitat imaging. Eur. Radiol. 34, 3215–3225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-023-10339-2 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Yang, C., Qian, X., Dai, Y. & Zeng, M. Evaluate the microvascular invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma (≤ 5 cm) and recurrence free survival with gadoxetate Disodium-Enhanced MRI-Based habitat imaging. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 60, 1664–1675. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.29207 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. Added value of histogram analysis of intravoxel incoherent motion and diffusion kurtosis imaging for the evaluation of complete response to neoadjuvant therapy in locally advanced rectal cancer. Eur. Radiol. 35, 1669–1678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-024-11081-z (2025).

Liu, Y. et al. Heterogeneity matching and IDH prediction in adult-type diffuse gliomas: a DKI-based habitat analysis. Front. Oncol. 13, 1202170. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1202170 (2023).

Zhang, H. et al. Breast cancer: habitat imaging based on intravoxel incoherent motion for predicting pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Med. Phys. 52, 3711–3722. https://doi.org/10.1002/mp.17813 (2025).

Long, L. et al. Tumor stiffness measurement at multifrequency MR elastography to predict lymphovascular space invasion in endometrial cancer. Radiology 311, e232242. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.232242 (2024).

Fang, S. et al. Intratumoral heterogeneity of fibrosarcoma xenograft models: Whole-Tumor histogram analysis of DWI and IVIM. Acad. Radiol. 30, 2299–2308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acra.2022.11.016 (2023).

Iima, M. Perfusion-driven intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) MRI in oncology: Applications, Challenges, and future trends. Magn. Reson. Med. Sci. 20, 125–138. https://doi.org/10.2463/mrms.rev.2019-0124 (2021).

Rosenkrantz, A. B. et al. Body diffusion kurtosis imaging: basic principles, applications, and considerations for clinical practice. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 42, 1190–1202. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.24985 (2015).

Jin, X. et al. Evaluation of amide proton Transfer-Weighted imaging for risk factors in stage I endometrial cancer: A comparison with diffusion-Weighted imaging and diffusion kurtosis imaging. Front. Oncol. 12, 876120. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.876120 (2022).

Yue, W. et al. Comparative analysis of the value of diffusion kurtosis imaging and diffusion-weighted imaging in evaluating the histological features of endometrial cancer. Cancer Imaging. 19, 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40644-019-0196-6 (2019).

Ou, R. & Peng, Y. Preoperative risk stratification of early-stage endometrial cancer assessed by multimodal magnetic resonance functional imaging. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 117, 110283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2024.110283 (2025).

Zhang, Q. et al. Multi-b-value diffusion weighted imaging for preoperative evaluation of risk stratification in early-stage endometrial cancer. Eur. J. Radiol. 119 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2019.08.006 (2019).

Satta, S. et al. Quantitative diffusion and perfusion MRI in the evaluation of endometrial cancer: validation with histopathological parameters. Br. J. Radiol. 94, 20210054. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20210054 (2021).

Wei, X. et al. Mechanisms of vasculogenic mimicry in hypoxic tumor microenvironments. Mol. Cancer. 20 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-020-01288-1 (2021).

Wang, J., Li, X., Yang, X. & Wang, J. Development and validation of a nomogram based on metabolic risk score for assessing lymphovascular space invasion in patients with endometrial cancer. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315654 (2022).

Visser, N. C. M. et al. Accuracy of endometrial sampling in endometrial carcinoma: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 130, 803–813. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000002261 (2017).

López-González, E. et al. Role of tumor volume in endometrial cancer: an imaging analysis and prognosis significance. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 163, 840–846. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.14954 (2023).

Celli, V. et al. MRI- and Histologic-Molecular-Based Radio-Genomics nomogram for preoperative assessment of risk classes in endometrial cancer. Cancers (Basel). 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14235881 (2022).

Valletta, R. et al. A nomogram for preoperative prediction of tumor aggressiveness and lymphovascular space involvement in patients with endometrial cancer. J. Clin. Med. 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113914 (2025).

Coada, C. A. et al. A radiomic-Based machine learning model predicts endometrial cancer recurrence using preoperative CT radiomic features: A pilot study. Cancers (Basel). 15 https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15184534 (2023).

Arezzo, F. et al. A Radiomic-based model to predict the depth of myometrial invasion in endometrial cancer on ultrasound images. Sci. Rep. 15, 15901. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00906-6 (2025).

Funding

This research received funding from the green seedling support projects of China-Japan Union Hospital of Jilin University(No. 2024QM03).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WW and JLL were responsible for data analysis and writing original manuscript; XMW was responsible for pathological information review; KMX, YHM and WCW were responsible for validation and writing-review; YM and YLJ were responsible for functional MRI image acquisition guidance; YS was responsible for nnFAE software analysis guidance; MCZ was responsible for investigation design and supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Y.M., Y.L.J. and Y.S. from a commercial company, Siemens Healthineers Ltd., were MR collaboration scientists doing technical support in this study under Siemens collaboration regulation without any payment and personal concern regarding to this study. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics declarations

All procedures were conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. This retrospective study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of China-Japan Union Hospital of Jilin University, approval number: 2025031319. Due to its retrospective nature, the requirement for obtaining written informed consent from patients was waived by the Ethics Committee of China-Japan Union Hospital of Jilin University. This waiver is consistent with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, which allows for such exemptions when obtaining informed consent is not feasible or practical.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, W., Lang, J., Xue, K. et al. Evaluate lymphovascular space invasion in endometrial cancer using diffusion-weighted imaging-based habitat imaging. Sci Rep 16, 1626 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31101-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31101-2