Abstract

Current mainstream methods for computing word similarity often struggle to precisely capture the fine-grained semantics of words across different contexts. Particularly, generative semantic representations typically suffer from issues such as part-of-speech bias, semantic ambiguity, redundant exemplars, and informational redundancy, all of which compromise the accuracy of similarity measurements. To address these problems, this paper proposes WSLE, a word similarity computation framework integrating the semantic generation capabilities of large language models (LLMs) with embedding-based vector representations. First, WSLE addresses four common challenges encountered in generating semantic representations using LLMs—part-of-speech bias, redundant exemplars, semantic ambiguity, and informational redundancy. By applying constraints to lexical items, grammatical categories, semantic descriptions, and prompt length, WSLE effectively mitigates these issues, thus enabling LLMs to generate coherent, precise, and contextually rich semantic representations. Second, these generated semantic representations are transformed into high-dimensional vector embeddings via a deep semantic embedding module, facilitating quantitative assessment of semantic similarity between words. Finally, the effectiveness of WSLE is rigorously evaluated through analyses based on Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (ρ). Experimental results on benchmark datasets, including RG65, MC30, YP130, and MED38, demonstrate that the proposed WSLE framework significantly outperforms existing similarity computation methods, exhibiting notable advantages in accuracy and robustness for word similarity measurement tasks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Word similarity computation has extensive applications across various natural language processing tasks, such as information retrieval, question-answering systems, and machine translation1. Traditional approaches to computing word similarity rely predominantly on word embedding models or rule-based methods. These techniques typically map words into lower-dimensional vector spaces to quantify their semantic similarity. However, due to their limited ability to fully capture contextual information and lexical polysemy, these conventional methods exhibit poor adaptability in complex linguistic scenarios, hindering their effectiveness in dynamically changing language environments and ultimately reducing the accuracy of similarity measurements. With recent rapid advancements in large language models (LLMs) and deep learning technologies, semantic representation methods based on LLMs have emerged as a prominent research focus2. Such models leverage extensive corpus data to effectively learn rich contextual information, allowing them to interpret word semantics at deeper semantic levels3. Consequently, semantic representations generated by large language models provide a promising new solution for word similarity computation. However, the effectiveness of LLM-generated semantic representations substantially depends on the model’s capability to accurately comprehend and process contextual information. An illustrative question arises (as shown in Fig. 1): Do longer textual explanations generated by LLMs positively influence subsequent word embedding processes by providing more comprehensive semantic representations, thereby improving embedding quality? Or do they introduce noise due to redundant information, diminishing model performance? Conversely, concise explanations, although succinct, may lack adequate context and detail, resulting in insufficient semantic expression. Exploring the optimal balance between verbosity and brevity in generated semantic explanations will contribute significantly to identifying the appropriate granularity that maximizes the downstream model’s performance.

Pre-trained language models (PLMs) have an inherent limitation regarding the maximum allowable input length of text4. When input texts exceed this length, truncation occurs, potentially leading to the loss of critical semantic information. Conversely, shorter texts typically require padding, which may result in semantic representations that are insufficiently clear or detailed. Moreover, the design of prompts for large language models is also crucial. Appropriately constructed prompts can significantly enhance computational accuracy by enabling models to better capture semantic relationships among words, particularly when dealing with synonyms, semantically related terms, and polysemous words.

To enhance the accuracy and robustness of large language models (LLMs) in generating semantic representations of words and to mitigate misinterpretations arising from inadequately designed prompts, this paper proposes a word similarity computation framework based on LLM-generated semantic representations (WSLE). Specifically, WSLE first introduces context-constrained prompts closely aligned with relevant lexical entities, effectively satisfying the semantic depth and precision requirements for similarity computation tasks. Subsequently, semantic representations capturing multidimensional and rich semantic features for each word are generated by the LLMs under these controlled prompts. Finally, a deep semantic embedding model transforms these generated representations into high-dimensional vectors, significantly improving the quality of word embeddings and enabling precise quantification of semantic similarity between words. The primary contributions of this study are as follows:

-

(1)

This study proposes a novel word similarity computation method (WSLE) that incorporates context constraints via prompt design and leverages large language models to generate semantic representations, thereby enhancing the authenticity and task adaptability of these representations.

-

(2)

Semantic representations generated by large language models are transformed into high-dimensional vectors, and the correlation between computed similarity scores and human judgments is comprehensively evaluated using Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlation coefficients, thus thoroughly assessing the model’s capability for similarity computation.

-

(3)

Extensive experiments were conducted on multiple standard benchmark datasets for similarity computation, systematically evaluating the performance of various large language models and word embedding models, and comparatively analyzing their differences in word similarity tasks. Experimental results reveal both the advantages and limitations of large language models compared to traditional embedding methods and further investigate intrinsic factors such as model temperature and stability, exploring their impact on word similarity computations.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section "Related work" reviews and analyzes existing research on word similarity computation. Section "Word similarity computation framework based on large language models and embedding vectors (WSLE)" presents the detailed design process of WSLE, the proposed word similarity computation framework that integrates large language models and embedding-based vectors. Section "Experiments" describes experimental evaluations and analyses of the WSLE framework. Finally, the paper concludes with a summary of the findings and directions for future research.

Related work

Traditional word similarity computation methods can be broadly categorized into four groups: dictionary-based semantic approaches5,6; distributional word embedding methods7,8,9; neural network-based models; and more recently, approaches based on pretrained language models and large language models.

Dictionary-based methods for semantic similarity computation rely on manually constructed knowledge bases such as WordNet. These approaches assess similarity by analyzing semantic paths or hierarchical relationships between lexical items. For example, Mititelu et al.10 conducted a semantic analysis of verb–noun derivations in Princeton WordNet. By performing morphological and semantic analysis on verb–noun pairs, their method automatically distinguished between zero-derivation and affixal derivation, while also identifying associated affixes. Song et al.11 proposed a hybrid framework that integrates a structurally transformed version of the Chinese thesaurus “CiLin” with a multi-inheritance conceptual network derived from HowNet. They employed information content–driven similarity algorithms and introduced a dynamic weighting strategy to combine results from both knowledge sources, thereby expanding the coverage of computable word pairs and improving the accuracy of similarity computation. Zhang et al.12 introduced a similarity computation approach for perceptual image design by incorporating the Chinese synonym forest (CiLin) into the evaluation of word similarity in the visual domain. Through the construction of a common distance and differential adjustment model, they achieved effective recognition and clustering of design-oriented target terms, validating the utility of thesaurus-based semantic dictionaries in image style mining. Although these dictionary-based approaches offer strong interpretability, they heavily depend on manually curated resources, which suffer from limited coverage, slow updates, and poor adaptability to context. As a result, such methods are less effective in open-domain or dynamically evolving semantic tasks where contextual nuance is crucial.

Distributional word embedding methods learn dense, low-dimensional vector representations of words by capturing their contextual co-occurrence patterns from large-scale corpora, enabling similarity measurement in vector space. For example, Chen et al.13 combined the hierarchical structure of WordNet with distributed vectors learned by Word2Vec from large corpora to enhance word similarity computation. S.M. et al.14 proposed a semantic document clustering method that integrates GloVe embeddings with the DBSCAN algorithm15.Wang et al.16 employed the fastText method to compute monolingual embeddings for Chinese and English, and further used the MUSE model to map these embeddings into a shared vector space. This allowed for a comparative analysis of supervised and unsupervised learning approaches using both parallel and non-parallel corpora. Jin et al.17 enhanced the HowNet and CiLin resources by incorporating Word2Vec embeddings as weighted parameters, computing word similarity through a weighted combination of the three knowledge sources. While these methods effectively capture distributional semantics, they are limited to static representations and cannot differentiate word senses across varying contexts. Furthermore, they lack reasoning capabilities and are therefore insufficient for handling semantic ambiguity or complex linguistic phenomena.

With the advancement of deep learning, neural network–based approaches for similarity computation have gained increasing attention. Representative architectures include Siamese networks18, Transformer-based models19, and methods leveraging pretrained language models and large-scale foundation models. For example, N.A. et al.20 employed a Transformer-based pretrained model to capture deep semantic information within sentences. The generated embeddings were fed into a parameter-sharing Siamese network to process pairs of user queries in parallel, significantly improving similarity detection accuracy. N. Peinelt et al.21 proposed a hybrid approach that integrates topic modeling with BERT. By extracting global thematic information from text via topic models and combining it with BERT representations using three different fusion strategies, the model achieved enhanced text understanding capabilities. Gamallo et al.22 introduced a compositional semantic framework for context modeling, offering an interpretable alternative to black-box Transformer architectures. Their method focuses on linguistic structures such as semantic roles and dependency relations to improve contextual representation. These neural models demonstrate strong performance in capturing semantic relationships between words or sentences across various NLP tasks. However, despite their contextual modeling capabilities, many of these approaches rely heavily on task-specific training and exhibit limited generalizability. Furthermore, their complex architectures often lack interpretability, making it difficult to clearly trace the semantic reasoning process.

In recent years, methods based on pretrained language models and large language models (LLMs) have emerged as a prominent research focus. These approaches not only capture deep contextual semantics but also demonstrate certain reasoning capabilities. Xu et al.23 leveraged the inferential abilities of large language models to enhance semantic similarity computation. By deriving semantic representations through LLM-driven reasoning, they achieved similarity measures that closely aligned with expert judgments. Jin and Lin24 proposed SimLLM, a semantic similarity computation method built on autoregressive LLMs. By introducing task-specific pretraining and a pooling-based similarity mechanism, their approach effectively overcame the limitations of traditional metrics such as BLEU and BERTScore, particularly in handling fine-grained semantics and domain-specific terminology. Xu S.C. et al.25 developed a semantic similarity framework for radiology reports using GPT-4, focusing on zero-shot label generation. Instead of relying on keyword extraction, the framework utilizes GPT-4’s reasoning capabilities to generate semi-structured semantic labels, which are then used to assess inter-document similarity. Compared to the previous three categories of methods, LLM-based approaches offer significantly stronger contextual understanding, semantic representation, and generalization capabilities. They are better suited to handling semantic ambiguity and complex linguistic phenomena, and they consistently produce similarity assessments that more closely resemble human judgment across a range of tasks.

Word similarity computation framework based on large language models and embedding vectors (WSLE)

In the word similarity computation task, the initial step involves generating word descriptions from the original dataset using unconstrained prompts, as illustrated in Fig. 2a and b. An analysis of these unconstrained prompt-based descriptions reveals that, in the absence of prompt restrictions, the generated content is often affected by factors such as part-of-speech bias, redundant examples, semantic ambiguity, and informational redundancy. These issues can significantly compromise both the accuracy and the stability of the similarity computation.

First, the issue of part-of-speech (POS) bias arises when prompts are unconstrained, leading the large language model to default to a particular POS during generation, rather than adhering to the intended grammatical category of the target word. In the initial dataset used in this study, target words were intended to be interpreted as nouns for the purpose of similarity computation. However, in the absence of explicit prompt guidance, the model occasionally defaulted to generating verb-form interpretations, resulting in semantic deviations. Such bias undermines the reliability of similarity measurement, as a single word can convey entirely different meanings depending on its grammatical role. For example, the word “hill” may be interpreted differently depending on its part of speech. As a noun, “hill” typically refers to “a naturally raised area of land, smaller than a mountain”; whereas as a verb, it can mean “to cover plants with soil around the base for protection or growth”. If the model defaults to the verb interpretation due to prompt ambiguity, the resulting semantic representation will deviate significantly from the intended meaning, thereby reducing the accuracy and reliability of similarity computations.

Second, when generating semantic explanations for a given word, large language models often provide additional examples to illustrate its meaning. For instance, when prompted with the word “fruit,” the model may automatically include instances such as “apple” or “banana” to aid comprehension. While such exemplification can enhance semantic understanding in general contexts, it may introduce extraneous semantic information in the context of word similarity computation. As a result, the generated representation may become biased toward prototypical examples rather than capturing the core semantics of the word itself. This bias can lead the model to prioritize canonical category members during similarity assessment, potentially obscuring other valid semantic relationships.

Moreover, semantic ambiguity refers to the phenomenon whereby a word may have multiple meanings depending on its context. Without prompt constraints, large language models tend to generate interpretations covering several possible senses of the word. This can lead to semantic deviations when comparing the generated representation with that of another word in the dataset. Such ambiguity often distorts similarity measurements—particularly when the target word pairs require domain-specific interpretations, where even slight semantic drift can significantly impair accuracy.

Finally, informational redundancy refers to the tendency of large language models to generate extensive content that may include information irrelevant to the target word. Under unconstrained prompting conditions, the model often produces lengthy outputs containing background context, extended explanations, or unnecessary situational descriptions. Such additional content can obscure the core semantics of the target word, introducing noise that interferes with the accuracy of similarity computation.

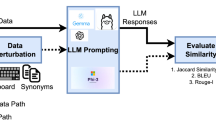

To address the four issues outlined above, we propose a word similarity computation framework that integrates large language models with context-aware word embeddings. The framework consists of several key components: LLM-driven semantic generation, a word embedding module for semantic representation, and a similarity evaluation mechanism. The overall architecture of the WSLE framework is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Vocabulary semantics generation driven by large language models

To enhance the stability and accuracy of word similarity computation, this study addresses four common issues: part-of-speech bias, redundant exemplars, semantic ambiguity, and informational redundancy. Accordingly, four key elements are selected for constraint in prompt design: the target word (w), its part of speech (posw), semantic description (descw), and token length (lendesc). These constraints ensure that the content generated by the model aligns more precisely with the intended semantic representation. Specifically, descw is used to enrich the semantic representation by prompting the model to generate word meaning descriptions, while lendesc serves to limit unnecessary verbosity, reducing the impact of redundant information on similarity computation.

First, to effectively address the issue of part-of-speech bias, the prompt design in this study explicitly incorporates the part of speech posw and introduces the following design strategy:

-

w = ‘word name’ ;

-

posw = ‘pos of the word’;

Prompt for POS misclassification

-

Please generate a description for the word ‘{w}’, which is a ‘{posw}’.

Part-of-speech (POS) serves as a strong prior constraint on semantic distribution. Conditioning on POS reduces semantic ambiguity: Let S denote the semantic meaning of the target word, W its lexical form, and POS its grammatical category. Then

This constrains the generation process from open-class interpretation to specified syntactic categories, preventing drift caused by default verb frames (e.g., misinterpreting “hill” as a verb). . In self-attention encoding, incorporating explicit part-of-speech prompts like “which is a {posw}” alters the prior distribution of attention. This encourages the model to retrieve syntactic-semantic substructures associated with nominal frameworks while reducing activation of irrelevant patterns like verbal argument structures. Consequently, it lowers intrasubclass variance for homophonic vectors, enhancing comparability and stability.

Second, to address the issue of redundant exemplification, this study introduces an explicit directive within the prompt design as follows:

Prompt for redundant exemplification

-

Do not include specific scenarios and application examples.

The prompt is explicitly constrained to elicit purely conceptual descriptions, prohibiting the inclusion of prototypical examples. This strategy effectively reduces interference from non-essential semantic content, ensuring that the generated representations remain general and abstract. As a result, the semantic outputs are more comparable across different word pairs, thereby improving the reliability of similarity computation.

From the perspective of prototype-exemplar theory, “exemplification” shifts representation from a word’s intension toward its extension (typical sub-words), introducing irrelevant category member information Z into the representation. If Z is an “example” noise variable, the ideal embedding Z* should maximize useful mutual information while minimizing irrelevant mutual information:

In mean pooling or MaxSim scoring, high-frequency words like “apple” or ‘banana’ dominate similarity scores, causing pseudo-similarity through thematic co-occurrence and obscuring target words’ core semantics. Prohibiting examples effectively suppresses irrelevant mutual information and thematic word dominance, reducing family resemblance contamination in cosine geometry and enhancing cross-word pair comparability. This paper’s prompt is specifically designed for this purpose, with its textual explanation emphasizing the mechanism of maintaining abstract, comparable representations.

To address the issue of semantic ambiguity, the prompt design in this study incorporates the following specific constraint:

Prompt for word sense ambiguity

-

If the word has multiple different meanings, provide the two most common meanings; otherwise, generate only the primary meaning.

The generation of polysemous words can be viewed as a probabilistic mixture of multiple semantic vector \(\{ ei\}\) representations:

The cosine similarity between two word vectors v and u includes cross-semantic terms, leading to overestimation or underestimation (e.g., misalignment with peripheral semantic items). Restricting the representation to “only the primary sense or at most two senses” effectively concentrates the distribution, increases the weight of dominant senses, reduces mixing variance and cross-term noise, and makes the similarity more closely aligned with the senses in the context being compared. This balances coverage and dilution: retaining two common senses avoids excessive narrowness, while suppressing long-tail senses prevents excessive breadth.

Finally, to mitigate informational redundancy, the design incorporates constraints on descw and lendesc, as described below:

-

w = ‘word name’ ;

-

descw = ‘ description of the word’;

Prompt for Information Redundancy

-

Ensure that the description ‘{descw}’ does not exceed ‘{lendes}’ tokens.

In semantic generation tasks, the length of generated outputs directly impacts information density and semantic focus. Without constraints, language models typically produce verbose descriptions laden with rhetorical embellishments, repetitive expressions, or low-value details. While these elements enhance textual richness on the surface, they dilute the prominence of core semantics, introducing noise unrelated to the target meaning into the embedded vectors. Within an information-theoretic framework, such redundancy increases the burden of ineffective information, making it difficult for model representations to remain compact and pure. By imposing length constraints, the model is compelled to prioritize extracting and expressing the most critical semantic elements within a limited space. This enhances the proportion of effective information in overall communication while reducing interference from redundant content.

From a linguistic perspective, effective language expression relies on accurately capturing core meaning, whereas redundant and verbose narratives often obscure significance. The Minimum Description Length principle indicates that concise, refined expressions more closely align with the essential semantics conveyed by language. Thus, limiting generation length is not merely a formal constraint but a semantic optimization method consistent with linguistic expression patterns.

Within the internal representation mechanisms of language models, excessively long texts can scatter focus in attention mechanisms, introducing excessive noise during alignment and aggregation of representations. For instance, during vector pooling, redundant functional words or low-relevance fragments can weaken key features, diminishing the distinctiveness of representations between different words. Imposing length constraints reduces the entropy of attention distributions, enabling the model to focus more intently on high-value semantic segments. This ultimately yields generated vectors with enhanced discriminative power and consistency.

Based on the above considerations, the final prompt template is defined as follows:

Prompt

-

Please generate a description for the word ‘{w}’, which is a ‘{posw}’. If the word has multiple different meanings, provide the two most common meanings; otherwise, generate only the primary meaning. Ensure that the description ‘{descw}’ does not exceed ‘{lendes}’ tokens. Do not include specific scenarios and application examples.

Since LLMs may generate text containing redundant elements—such as conversational phrasing, ambiguous expressions, or irrelevant elaborations—these outputs can compromise the accuracy of semantic representations. To further enhance precision and reduce redundancy, text cleaning techniques such as regular expression matching and keyword filtering are applied to optimize the LLM-generated semantic descriptions. This process is governed by a semantic compression function, defined as follows:

Here, \(P\) denotes the constrained prompt that guides the LLM to generate semantic descriptions aligned with the intended meaning. \(\Phi\) represents the application of regular expressions for pattern matching, which removes redundant punctuation, verbose semantic elaboration, and non-essential content. \(K\) refers to the keyword filtering step, which retains only the core definition of the target word. \(C(w)\) denotes the final cleaned semantic description obtained after applying prompt constraints, regular expression matching , and keyword filtering .

In addition, considering the length limitations of most pre-trained language models when processing text, a maximum token length \(L\max\) is defined. The target word is concatenated with its cleaned semantic description, forming a combined sequence with length L. If \(L\) > \(L\max\), the sequence is truncated accordingly.

Here, \(C^{\prime } (w)\) denotes the truncated version of the cleaned semantic description, which is used as the final input to the model and ensures that its length does not exceed \(L\max\). The processed descriptions for all target words are eventually stored in a JSON file format.

To clarify the specific rules of the semantic compression function—namely, the Regular Expression Cleaning (RE) step and the Keyword Filtering (KW) step. We provide the complete implementation in the form of pseudo-code in Algorithm 1 below. This list clearly shows each operation (prompt construction, noise removal based on regular expressions, keyword retention, and length control), thereby ensuring that this process is clear, transparent, and fully repeatable.

Word embedding module

The word embedding module is designed and implemented to transform each preprocessed word–description pair into a high-dimensional vector representation, enabling semantic similarity computation based on cosine similarity26. This module adopts the Sentence-BERT framework27 as the core encoder. Specifically, it constructs input sequences that combine the target word with its semantic description, and employs BERT28 for deep semantic modeling to generate context-rich word embeddings. A pooling strategy is applied to the encoded sequence in order to obtain a fixed-dimensional representation, ensuring consistency and comparability of the semantic vectors. Finally, cosine similarity is used to compute the semantic similarity between word embeddings, reflecting the model’s ability to assess semantic relatedness between words.

To ensure input format standardization and fully leverage the encoding capabilities of the model, this study adopts the structured input format of BERT:

Here, \([CLS]\) is a special token used to indicate the beginning of the input sequence, while \([SEP]\) serves as a separator token that distinguishes the target word from its semantic description. This structured input format enables the model to accurately interpret the relationship between the two components and generate appropriate semantic representations.

This structured input is then fed into a pre-trained encoder, where it is mapped into a high-dimensional vector representation.

Here, \(\varphi \theta\) denotes the nonlinear mapping function of the BERT encoder parameterized by \(\theta\), and \(H \in R^{d}\) represents the resulting \(d\)-dimensional vector. This vector captures the deep semantic features of the target word and its description, making it suitable for subsequent similarity computations.

Since BERT produces token-level contextual representations, a pooling operation is required to transform these into fixed-size vector representations suitable for subsequent semantic similarity computation. The average pooling operation is defined as follows:

After obtaining the word embeddings, cosine similarity is used to measure the semantic similarity between two words:

Here, \(vwi\) and \(vwj\) represent the vector embeddings of words \(wi\) and \(wj\), respectively. Cosine similarity measures the angle between the two vectors, with a value range of [− 1,1]; a value closer to 1 indicates a higher degree of semantic similarity between the two words. This similarity measure effectively evaluates the semantic relationship between words while mitigating the influence of scale differences caused by varying embedding magnitudes.

Experiments

Dataset

To comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method, several classical word similarity datasets are utilized, including both general-purpose and domain-specific data covering various parts of speech, thereby ensuring the robustness of the experiments. Table 1 summarizes the detailed characteristics of the four benchmark datasets employed in this study, including dataset names, years of publication, number of word pairs(Pairs), parts of speech (POS), and scoring ranges(Scores). Among these, RG65 contains similarity ratings for 65 noun pairs and is widely adopted as a validation benchmark in word similarity tasks. MC30, a subset of RG65 comprising 30 noun pairs, also plays an important role in lexical semantic research.

To further enhance the robustness of the experiments, the YP130 and MED38 datasets were incorporated. YP130 focuses on verb semantic similarity and includes 130 verb pairs, allowing the evaluation to extend beyond noun similarity to cover different parts of speech. MED38 is a domain-specific dataset in the medical field, consisting of 38 pairs of medical terms with similarity scores. It serves as a valuable benchmark for evaluating semantic similarity in medical text processing tasks.

All selected datasets adopt a unified scoring scale ranging from 0 to 4, where 0 indicates complete irrelevance and 4 denotes high semantic similarity. This consistent scoring range facilitates a standardized evaluation framework across datasets involving different parts of speech and domains, enabling a more accurate comparison of the performance of various methods in word similarity computation tasks.

Evaluation metrics

To evaluate the effectiveness of the word similarity computation methods, two evaluation metrics are adopted: the Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC)32 and the Spearman Rank Correlation Coefficient (SCC)33. PCC measures the linear correlation between the computed similarity scores and human-annotated scores, while SCC assesses the consistency in ranking between the two, reflecting the ordinal relationship.

PCC is a statistical measure used to assess the linear correlation between two variables, with values ranging from − 1 to 1. A coefficient close to 1 indicates a strong positive correlation, while a value near − 1 suggests a strong negative correlation. A coefficient around 0 implies little to no linear relationship.In this study, PCC is employed to evaluate the linear consistency between the similarity scores predicted by the model and the human-annotated ground truth. The formula for PCC is as follows:

Here, \(xi\) and \(yi\) denote the predicted similarity score and the human-annotated similarity score for the.

i-th word pair, respectively. \(\overline{x}\) and \(\overline{y}\) represent the mean values of \(x\) and \(y\), and \(n\) is the total number of word pairs in the dataset.

SCC is a non-parametric statistical measure based on ranks, used to assess the monotonic relationship between two variables without requiring a strict linear correlation. Its values also range from − 1 to 1, where 1 indicates a perfect monotonically increasing relationship, − 1 indicates a perfect monotonically decreasing relationship, and 0 suggests no correlation. In word similarity tasks, SCC is primarily used to evaluate whether the ranking of similarity scores predicted by the model is consistent with that of the human annotations. The formula for computing SCC is as follows:

Here, \(di\) denotes the difference between the predicted rank and the human-annotated rank for the i-th word pair, and \(n\) is the total number of word pairs in the dataset.

Experiment and result analysis

Prompt optimization experiments

This experiment initially employed SBERT in combination with Qwen-7B-Chat to perform word similarity computation on the RG65 dataset, with a focus on investigating the impact of prompt optimization on model performance.The experimental results, as shown in Fig. 4, clearly demonstrate a significant improvement in model performance as different prompt strategies are sequentially introduced. Starting with the LLM-Original model, which has no prompt restrictions, the Pcc value is 0.6604. Following the addition of a part-of-speech bias prompt, the performance increases to 0.7408, marking an improvement of 10.67%. Subsequently, the incorporation of an informational redundancy prompt further enhances the Pcc value to 0.7947, with a 7.28% increase. With the inclusion of a redundant exemplification strategy, the Pcc value rises to 0.8831, showing a 4.61% improvement. Finally, the introduction of a semantic ambiguity handling prompt leads to a modest increase in the Pcc value to 0.8374, with a 0.73% improvement.These optimization steps indicate that the careful design and introduction of prompt strategies can effectively enhance model performance, particularly in areas such as part-of-speech bias adjustment, informational redundancy, and redundant exemplification, where the improvements are most pronounced.

Comparative experiments on word similarity computation across different methods

The experiments compared the performance of various methods on four word similarity datasets: RG65, MC30, YP130, and MED38. Among them, RG65 and MC30 are primarily used to assess the semantic similarity of general-domain nouns, while YP130 focuses on modeling the semantic relationships of verbs. MED38, as a domain-specific dataset in the medical field, is designed to evaluate each method’s capability to understand the semantics of specialized terms. The overall results, as presented in Table 2 and illustrated in Fig. 5, demonstrate that the proposed WSLE framework consistently outperforms the majority of existing approaches across all four datasets. This combined tabular and visual evidence substantiates the effectiveness and robustness of the WSLE framework in addressing diverse word similarity computation tasks.

To enhance the persuasiveness of the experimental results, the comparative experiments in this paper also incorporate two relatively recent, LLM-based text similarity measurement methods from the past three years. We adapted Alnajem et al.’s twin metric learning paradigm for demand-oriented text similarity, applying it to the scenario of word similarity. This involved replacing the original task’s sentence-level inputs with refined semantic descriptions generated by large models without prompt words. Initial representations were obtained using a pre-trained Transformer, supplemented by shared BiLSTM and concatenation-difference-interaction features, in order to construct fine-grained comparative encodings for word pairs. A regression head was then fitted to the manually annotated scores. We also adapted the STS-SBERT method proposed by Sornlertlamvanich for word similarity computation. Specifically: First, the key information extraction step from FAQ answers was analogised to generating core definitions for words, constructing a concise, representative single-sentence semantic description for each target word. Secondly, whereas the original method uses T5 to generate diverse questions to expand query expressions, this method generates three semantic extension descriptions per word to enhance semantic coverage. The core discriminative mechanism of STS-SBERT remains unchanged: Sentence-BERT, which is fine-tuned for semantic text similarity tasks, performs a pairwise comparison of the definitions and the expanded sets of two words. The maximum similarity score is then used as the final word similarity score.

In the process of calculating the similarity between generic terms, the RG65 and MC30 datasets are frequently utilised to assess the efficacy of a method in modelling semantics, particularly in relation to everyday vocabulary. The experimental results demonstrate that WSLE attains a correlation coefficient of 0.87 on the RG65 dataset, thus achieving a tie with Sornlertlamvanich’s STS-SBERT method for the optimal performance, and surpassing Alnajem (0.86) and alternative methods. On the MC30 dataset, the GV method achieved the best result at 0.88, followed by Sornlertlamvanich’s method (0.87). It is evident that WSLE obtained a value of 0.84, thus demonstrating a level of performance that is comparable to methods employed by Aouicha and Alnajem. This outcome is attributable to STS-SBERT leveraging generated definitions and expanded descriptions to cover core noun semantics during task transfer, yielding more balanced performance on smaller datasets like MC30. In contrast, the WSLE demonstrates notable proficiency in the large-scale RG65 dataset, leveraging prompt-guided large-model representations to discern subtle semantic nuances between nouns.

In order to surmount the impact of part-of-speech bias and to evaluate the modelling capability of verb semantics, this study appraised a variety of methods on the YP130 dataset. Verbs demonstrate greater semantic variability, thus rendering this task more challenging. The findings indicate that the Sornlertlamvanich method exhibits a correlation coefficient of 0.83 on this particular dataset, closely followed by the Liu-based methods with coefficients of 0.80 and 0.79, respectively. The WSLE method achieves a coefficient of 0.78, marginally surpassing Alnajem’s result of 0.76. This outcome is attributable to the capacity of STS-SBERT to more effectively capture verb polysemy across diverse contexts through its large-model-generated expanded descriptions, yielding substantial gains. In contrast, the Alnajem method relies on BiLSTM concatenation and interaction feature modelling, which performs well at the sentence level but proves insufficient for fully characterising complex dependencies in the highly semantically variable verb domain. It is evident that WSLE guarantees stability through the provision of prompt-generated single-sentence semantic definitions. However, it should be noted that its coverage is marginally inferior to that of STS-SBERT.

In medical domain-specific term similarity tasks, vocabulary often exhibits finer semantic distinctions and higher discriminative power, placing greater demands on methods’ semantic capture capabilities. The experimental results demonstrate that WSLE attains the optimal performance of 0.76 on the MED38 dataset, thereby exceeding the performance of Sornlertlamvanich (0.72) and Alnajem (0.70). The primary reasons for this outcome are as follows: Despite the Alnajem method’s employment of a twin metric learning paradigm, its reliance on BiLSTM concatenation and interaction features renders it optimal for modelling general text pairs, thus exposing limitations when processing medical terminology that necessitates domain knowledge support. Sornlertlamvanich’s approach has been shown to enhance coverage in general scenarios through the use of diverse expansion descriptions. However, the generated expansions have been found to lack semantic constraints, which has resulted in difficulties in capturing subtle distinctions between proper nouns. In contrast, WSLE employs prompt-guided large models to generate concise and focused definition descriptions, thus avoiding redundancy and deviation in semantic expansion. This approach facilitates the creation of more effective models of medical terminology, resulting in significantly superior performance in specialised domains when compared to alternative methods.

In terms of average ranking, Sornlertlamvanich’s STS-SBERT method leads with an average rank of 1.5, demonstrating its overall balance across various datasets through diversified expansion descriptions. WSLE achieved an average ranking of 2.25, placing second, with strengths in cross-domain stability and outstanding performance in specialized domains. Alnajem’s method recorded an average ranking of 3.75, indicating competitiveness on specific datasets like MC30 and RG65 but lacking overall stability. A comprehensive analysis reveals that STS-SBERT’s strength lies in leveraging large models to generate expanded descriptions that address polysemy. WSLE excels through prompt-driven refined definitions that ensure cross-domain generalization. Alnajem’s advantage stems from its fine-grained interaction feature modeling, though it remains constrained to scenarios with minimal semantic variation. Consequently, the three approaches form a complementary landscape, with WSLE demonstrating superior robustness and adaptability across cross-domain tasks and specialized vocabulary.

Comparative performance analysis of different large language models on word similarity datasets

To evaluate the impact of different large language models on word semantic generation, six models—Bloom-7b144, Qwen-7B-Chat-int4, Qwen-7B-Chat45, DeepSeek-7B46, GPT-3.5-turbo, and GPT-447 were tested on four benchmark datasets. The Pearson correlation coefficient and Spearman rank correlation coefficient were calculated for each model, and the results are summarized in Table 3.

Overall, ChatGPT-4 achieved the highest Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients across all datasets, demonstrating the strongest capability in semantic similarity computation. On the RG65 dataset, the values of r and ρ reached 0.8723 and 0.8469, respectively; on MC30, they were 0.8444 and 0.8340. Its performance on the YP130 and MED38 datasets also surpassed that of all other models, indicating its superior ability to capture and reason about semantic similarity. ChatGPT-3.5-turbo ranked second in performance, with correlation scores on all four datasets close to those of ChatGPT-4. This suggests that it retains strong generalization ability in semantic understanding. However, it still shows limitations in datasets that require finer-grained semantic discrimination or heightened sensitivity to contextual variation. DeepSeek-7B, as a relatively new and powerful model, performed slightly below ChatGPT-3.5-turbo across the four datasets. Nonetheless, it demonstrated reasonable semantic alignment capabilities overall. The results suggest that, compared to the GPT series, DeepSeek may be somewhat less effective in generating semantically accurate English representations, which could lead to embedding discrepancies in word-level similarity tasks.

In contrast, the Qwen series exhibited comparatively lower performance than the ChatGPT models and DeepSeek-7B. Specifically, Qwen-7B-Chat achieved Pearson correlation coefficients of 0.8374, 0.8297, 0.7599, and 0.7421 on the RG65, MC30, YP130 and MED38 datasets, respectively. The corresponding Spearman correlation coefficients were 0.8089, 0.8429, 0.7259 and 0.7428. Although slightly lower than the top-performing models, Qwen-7B-Chat still maintained relatively strong capability in semantic similarity computation. However, its quantized version, Qwen-7B-Chat-Int4, exhibited a consistent drop in both r and ρ values across all datasets. The decline was particularly notable on the YP130 and MED38 benchmarks, suggesting that low-precision quantization compromises the model’s ability to yield high-quality semantic representations, especially in context-sensitive or domain-specific scenarios48. A layer-wise inspection of the Int4 checkpoints reveals two intertwined mechanisms driving this degradation. Firstly, uniform 4-bit rounding compresses key–query dot products into a narrow integer range, flattening the softmax distribution and blurring attention maps, so the fine-grained verb semantics in YP130 and the morphemic cues in MED38 become attenuated. Secondly, clipping and rounding in the embedding and MLP blocks push activations toward the origin, and collapsing the cosine geometry that underpins correlation-based similarity metrics. Compared with the FP16 baseline, the average activation norm of the penultimate Transformer block decreased by approximately 21%, and its variance was almost halved, which made it difficult to form detailed representations49,50. The findings show that the performance loss stems not from a generic capacity shortage but from a structural distortion of the attention distribution and embedding topology, implying that quantization-aware fine-tuning or selectively retaining higher precision at attention and embedding bottlenecks would be more effective than simply increasing bit-width across all layers.

Among all models tested, Bloom-7B1 demonstrated the weakest overall performance. On RG65, it achieved a Pearson correlation of only 0.7947 and a Spearman correlation of 0.7724, with even lower scores observed on YP130 and MED38. These results indicate that Bloom-7B1, within the WSLE framework, is less effective for semantic similarity computation tasks. The limitations may stem from factors such as smaller parameter scale, lower-quality pretraining data, or architectural constraints, all of which could hinder its generalization ability across diverse semantic contexts.

With respect to the datasets, the Pearson and Spearman correlation scores on RG65 and MC30 were generally higher, suggesting that large language models are effective in generating semantic representations that are well aligned with the part-of-speech and contextual properties of general-domain nouns. In contrast, the correlations on the YP130 and MED38 datasets were overall lower, particularly for models such as Bloom-7B1 and Qwen-7B-Chat-Int4, which showed a more pronounced performance decline. This suggests that datasets involving specific domains or other parts of speech impose higher demands on the model’s semantic precision and context sensitivity. As a result, lower-performing models struggle to accurately capture the nuanced semantic relationships required in these tasks.

To further assess the fine-grained differences in performance across datasets, a residual heatmap analysis was conducted for various large language models on the four semantic similarity benchmark datasets. This visualization intuitively reveals the prediction bias of each model at the individual sample level. In the heatmap, the horizontal axis represents the sample index, while the vertical axis lists the names of the different language models. The color spectrum ranges from blue (negative residuals, where the predicted value is lower than the ground truth) to red (positive residuals, where the predicted value is higher than the ground truth). Darker colors indicate larger prediction errors.

As shown in Fig. 6a and b, the largest errors are linked to the five word pairs that show the highest absolute residuals in each benchmark. On RG-65, the five highlighted pairs grin–smile, journey–voyage, cushion–pillow, midday–noon and gem–jewel are near-perfect synonyms whose human ratings sit close to the upper bound. Bloom-7B1 and Qwen-7B-Chat-Int4 markedly over-estimate these already high scores, revealing a tendency to compress the similarity scale and overlook subtle pragmatic distinctions. In contrast, Qwen-7B-Chat and DeepSeek-7B show flatter residual profiles, while ChatGPT-3.5-turbo and ChatGPT-4 keep all five residuals within ± 0.5, confirming their finer sensitivity to synonymy. A complementary pattern appears on MC-30, and the outliers coast–forest (co-hyponyms), brother–monk (hyponym–hypernym), tool–implement (synonyms), asylum–madhouse (synonyms) and coast–shore (near synonyms) expose two failure modes: Bloom-7B1 under-predicts for coordinate pairs such as coast–forest, whereas Qwen-7B-Chat-Int4 and the base Qwen variant over-predict highly similar pairs like tool–implement and asylum–madhouse. The GPT series again shows muted residuals across all five cases, reflecting more accurate modelling of both synonymy and taxonomic distance.

Figure 6c and d reveal a different landscape for the verb-dominated YP-130 and domain-specific MED-38 benchmarks. In YP-130, the starred pairs hail–acclaim, resolve–settle and submit–yield are near synonyms that differ mainly in register or argument structure. The uniformly negative residuals show that most models, especially Bloom-7B1 and Qwen-7B-Chat-Int4, systematically under-estimate their similarity, indicating difficulty in capturing verb entailment. ChatGPT-4 again limits its error to about 0.4 or less, underscoring better verb-sense alignment. On MED-38, the dominant error pair hypothyroidism–hyperthyroidism (antonyms within the same medical axis) produces large positive residuals for every model except ChatGPT-4, which approaches the human rating. The other models confuse antonymy with topical relatedness when faced with morphologically similar medical terms, inflating the predicted similarity. By tying each residual hotspot to a specific word pair, we can see exactly where a model struggles, whether through scale compression, gaps in verb entailment, or confusion between antonyms in specialized domains, and at the same time confirm the GPT family’s superior robustness in both general-language and domain-specific semantics.

In order to further evaluate the quality of semantic descriptions generated by large language models, this study incorporates an assessment of the outputs from the best-performing model (ChatGPT-4) and the lowest-performing model (Bloom-7B1), and examines the relationship between description quality and the resulting similarity scores, thereby clarifying the respective contributions of generative descriptions and embedding-based methods within the framework. Specifically, for each generated description, the model was further prompted to identify the most similar word to word1 in each dataset pair, and pairs with human ratings above 3.0 were extracted as supporting evidence. In addition, the word pairs that the lower-performing model failed to recognize correctly, as well as the confused cases, were collected and analyzed in detail. The results of this evaluation are presented in Fig. 7.

For the cushion–pillow pair, the two systems diverge both in definitional form and semantic content. Bloom-7B1 renders cushion in a genus-like pattern but shifts to a narrative style for pillow, which lacks a stable genus head and introduces context-dependent phrasing. This inconsistency in definitional form prevents the embeddings of the two terms from aligning structurally. Moreover, while cushion is additionally associated with decoration, pillow is characterized mainly through the sleep context. These differences project the embeddings into partially distinct subspaces—one oriented toward decorative objects, the other toward sleep-related items—thereby weakening their functional overlap. Since embedding-based similarity depends on shared semantic anchors, the absence of a unifying attribute reduces the measured similarity. By contrast, ChatGPT-4 maintains a consistent definitional template across both terms and repeatedly foregrounds the common attributes of support and comfort. This structural parallelism and semantic convergence produce embeddings with overlapping foci, yielding vectors that cluster more closely together and align with human similarity ratings.

For the hill–mound pair, Bloom-7B1 produces a colloquial and vague description of hill, which lacks explicit geomorphological anchors such as landform or earth. More critically, the inclusion of anthropocentric terms like people introduces features that overlap with the description of wizard, which also emphasizes human-related attributes. As a result, the embeddings of hill and wizard converge spuriously in vector space, leading to misidentification. ChatGPT-4, in contrast, generates a formal and taxonomically precise definition of hill, thereby introducing strong topographic anchors such as land and mountain. Its definition of mound likewise stresses a raised area of earth, providing an explicit semantic bridge between the two. This consistent genus-and-differentia structure and cross-term anchoring align both terms within the same geomorphological cluster, while clearly separating them from anthropocentric concepts. Consequently, ChatGPT-4 successfully recovers the correct similarity relation consistent with human judgments.

Comparative performance analysis of different word embedding models

To further investigate the impact of different word embedding models on similarity computation performance, several embedding approaches were tested and analyzed. While large language models offer strong semantic understanding capabilities, the choice of word embedding model, which serves as the foundation for semantic representation, remains a critical factor influencing the final similarity scores. By comparing different embedding methods experimentally, the relative strengths and weaknesses of various word representation techniques in semantic similarity tasks can be quantified. These insights can contribute to the refinement of similarity computation strategies. Table 4 reports the Pearson correlation coefficient (r) and Spearman rank correlation coefficient (ρ) obtained by different pre-trained embedding models, evaluated under the semantic enhancement guidance provided by ChatGPT-4.

As shown in Table 4, ColBERT51 employs a late interaction mechanism that retains fine-grained token-level representations while enabling efficient similarity scoring via maximum similarity aggregation. E552, in contrast, is an instruction-tuned embedding model designed to produce semantically rich sentence-level vectors across diverse NLP tasks. ColBERT + ChatGPT-4 achieves strong results across general benchmarks, with Pearson/Spearman correlations of 0.9235/0.8997 on RG65, 0.8900/0.8931 on MC30, and 0.8666/0.8196 on YP130—outperforming all baselines including Sentence-BERT. On the specialized MED38 dataset, it reaches 0.7433/0.7717, and shows good generalization to technical terms. E5 + ChatGPT-4 yields the best overall performance, ranking first on all four datasets. It records 0.9426/0.9140 on RG65, 0.9571/0.9490 on MC30, 0.8443/0.8306 on YP130, and 0.8134/0.8492 on MED38—indicating both semantic precision and cross-domain robustness.

The combination of Sentence-BERT and ChatGPT-4 achieves consistently high Pearson (r) and Spearman (ρ) correlation coefficients on all datasets, with scores of 0.8723 on RG65 and 0.8444 on MC30, outperforming earlier BERT-series models. These results indicate that Sentence-BERT exhibits the strongest fitting ability in semantic similarity computation tasks. Its consistently high Spearman correlation also demonstrates that the combination of Sentence-BERT and a large language model not only closely approximates human annotations in absolute similarity scores, but also maintains high accuracy in relative ranking. In contrast, the experimental results reveal that neither BERT nor RoBERTa holds an across-the-board advantage; their relative performance is strongly dataset-dependent. On RG65, which consists mainly of high-frequency common nouns with relatively homogeneous semantics, RoBERTa—benefiting from a larger pre-training corpus and its dynamic span-masking strategy—surpasses BERT in both Pearson and Spearman correlations. Conversely, in MC30, where polysemy is more prevalent and accurate cross-sentence consistency is required, BERT leverages its Next Sentence Prediction (NSP) objective to achieve a higher Pearson correlation, although it still trails RoBERTa slightly in Spearman correlation. YP130, composed largely of verbs whose meanings hinge on event structure and intra-sentence dependencies, instead favors BERT, whose WordPiece tokenization and NSP objective appear to model such event-level semantics more effectively. In the specialized MED38 benchmark, which includes compound medical terms, BERT’s finer-grained WordPiece tokenization can decompose morphemes such as osteo- and -itis, providing additional semantic cues for rare terms and yielding stronger overall correlations than RoBERTa. In summary, BERT and RoBERTa exhibit comparable overall representational capacity, yet each displays distinct advantages depending on lexical distribution, domain-specific vocabulary, and evaluation criteria.

In this experiment, word semantics are not represented as isolated lexical items, but are conveyed through generated semantic description sentences. As a result, the model’s ability to capture inter-sentential coherence becomes especially critical. The BERT model, through its incorporation of the Next Sentence Prediction (NSP) objective, enhances its capacity to model relationships between sentences and maintain contextual coherence. This enables BERT to better understand the overall semantic connections across multiple sentences, providing it with a certain advantage in tasks that rely on sentence-level semantic reasoning. In contrast, while RoBERTa has demonstrated superior performance on various NLP benchmarks, it removes the NSP objective during pretraining. Consequently, its ability to capture semantic coherence across sentences is relatively weaker, which may hinder its performance in tasks where word meanings are presented through multi-sentence structures, such as in this study. This could explain why RoBERTa underperforms BERT in the current word similarity computation task.

Compared to BERT and RoBERTa, ALBERT shows a slight decline in overall performance, though it still significantly outperforms XLNet. Results on the RG65 and MC30 datasets suggest that ALBERT maintains relatively stable performance on certain general-domain datasets. However, on YP130 and MED38, its performance declines noticeably, with Pearson correlation coefficients of 0.5727 on YP130 and 0.5075 on MED38, indicating potential limitations in generalization when handling complex or infrequent vocabulary in semantic similarity tasks. ALBERT’s parameter-sharing mechanism, while reducing computational cost, limits representational capacity, making it more difficult for the model to capture fine-grained semantic distinctions. Its pretraining objective, Sentence Order Prediction (SOP), primarily emphasizes intra-sentence coherence rather than the modeling of cross-sentence semantic relationships, which may limit its effectiveness in tasks involving phrase-level or rare-word similarity. In addition, the factorized embedding parameterization, which compresses the dimensionality of word embeddings, further restricts the model’s ability to represent low-frequency words. This likely contributes to its degraded performance on long-tail vocabulary, particularly evident in specialized or syntactically complex datasets such as YP130 and MED38.

XLNet demonstrated the lowest Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients across all datasets. In particular, it achieved only 0.3318 and 0.3065 in Pearson correlation on the MC30 and MED38 datasets, respectively, and 0.2061 and 0.2814 in Spearman correlation on the same datasets. These results indicate that even when combined with ChatGPT-4, XLNet fails to significantly improve its performance in semantic similarity computation tasks. The weak performance of XLNet can largely be attributed to its permutation-based autoregressive architecture. While this design provides advantages in text generation tasks, it presents limitations when it comes to capturing precise semantic similarity. Unlike bidirectional Transformers such as BERT and RoBERTa, XLNet models sequences by predicting missing tokens based on various permutations, focusing more on token prediction than on modeling global semantic coherence. Moreover, XLNet’s mask-free training objective leads to unstable token dependency patterns across different permutations, which may hinder its ability to model fixed semantic relationships between word pairs. As a result, in short-text or pairwise similarity tasks, XLNet is less effective at capturing bidirectional contextual semantics, making it inferior to BERT-based models in semantic matching tasks.

To assess the robustness in the absence of information, four low-frequency medical terms from the MED38 benchmark dataset—roseola, osteoarthritis, thiopental and glucagonoma—were selected. Using the WSLE framework, six consecutive descriptions were generated in each round. Figure 8 shows the average intra-word Jaccard similarity of these descriptions, which serves as an indicator of lexical diversity. The similarity for roseola and osteoarthritis was 0.36 and 0.37 respectively, indicating that even with only a small amount of contextual cues, the model can generate relatively diverse synonymous expressions. In contrast, the similarity for thiopental sodium (0.47) and glucagonoma (0.53) was much higher, suggesting that the WSLE framework, even when almost no external evidence is available, tends to reuse fixed templates to preserve the key medical content.

The qualitative analysis in Fig. 9 corroborates this tendency: colour-highlighted segments show that all six glucagonoma definitions converge on the chain “rare tumour → pancreas → excess glucagon → hyperglycaemia,” whereas the roseola set displays richer syntactic and lexical variation across viral aetiology, cutaneous rash, and paediatric prevalence. These findings indicate that, for rare terms, WSLE safeguards semantic accuracy at the expense of surface-level diversity; nevertheless, the essential clinical facts are consistently retained, underscoring the framework’s resilience when contextual information is scarce.

To further verify the semantic discriminative capability of the word embeddings obtained by applying Sentence-BERT to word descriptions generated by a large language model, a two-dimensional visualization was conducted using the t-SNE method. The embeddings of ten word categories were projected into a 2D space, and the results are shown in Fig. 10.

The figure presents the embedding samples of ten target words (e.g., automobile, cemetery, pillow, etc.) generated through the proposed method. From the t-SNE visualization results, several observations can be made: First, semantically similar words exhibit clear clustering behavior. For example, automobile and car, cemetery and graveyard, noon and midday are located in close proximity, indicating that the embedding space effectively captures semantic similarity. Second, there is a clear separation between semantically unrelated words, such as pillow versus cemetery or gem, which are well-distinguished in the embedding space. This demonstrates that the embedding model possesses strong discriminative capability in representing semantic differences across categories. In summary, the visualization results validate the effectiveness of combining large language model–generated word descriptions with Sentence-BERT embeddings. The approach not only ensures strong intra-class cohesion for semantically similar words, but also maintains clear inter-class boundaries, providing a solid foundation for accurate word similarity computation in downstream tasks.

Investigation of temperature coefficient and output stability in large language models

To further explore the internal factors influencing large language models in semantic similarity computation tasks, two experiments were designed: one focusing on the temperature coefficient, and the other on model output stability. The results of these experiments are presented in Tables 5 and 6, respectively corresponding to each experimental setting.

Table 5 presents an analysis of the performance of the large language model in semantic similarity computation under varying temperature coefficients (t), with t set to 0.5, 0.7 and 1.0. The evaluation was performed using r and ρ on the RG65 and MC30 datasets. The experimental results show that the temperature coefficient has a significant impact on performance. When t = 0.5, the model achieved the best results, with Pearson correlations of 0.8374 on RG65 and 0.8297 on MC30, and Spearman correlations of 0.8089 and 0.8429, respectively. As the temperature increased, the correlation values gradually declined. When t = 1, the Pearson correlations dropped to 0.7151 (RG65) and 0.7240 (MC30), while the Spearman correlations declined to 0.6974 and 0.6613, respectively. These findings suggest that lower temperature coefficients help reduce randomness during the generation process, leading to more consistent semantic representations under identical input conditions. This is particularly critical in semantic similarity tasks, where stable vector representations are essential for ensuring consistent and reliable similarity measurements. In contrast, higher temperatures increase the sampling probability of lower-likelihood tokens, introducing more diversity in the generated output. While such diversity may benefit generative tasks, it increases variability in similarity scoring across inference runs, thereby reducing consistency in word pair evaluations.

Table 6 analyzes the response stability of different large language models in semantic similarity computation tasks, measured by their effective response rate. To ensure the reliability of the evaluation, a multi-round response mechanism was employed to assess model consistency in generating valid outputs for word pair similarity tasks. During the initial round of experiments, directly inputting all word pairs from the dataset into the models resulted in a considerable number of invalid or unreasonable responses. For example, some models failed to return appropriate word-level outputs, or generated results that did not conform to the expected format—cases that are unacceptable in real-world applications. To address this issue and ensure a fairer assessment, a fallback inference mechanism was introduced. This allowed the model to regenerate outputs in subsequent rounds when the initial response was deemed invalid, thereby improving the robustness and reliability of the effective response rate metric.

First, all word pairs were sequentially input into the language model, and the valid response rate from the first inference round was recorded. For word pairs that failed to yield a reasonable semantic representation in the initial round, they were not immediately classified as invalid. Instead, these cases were extracted for further evaluation through up to five rounds of supplementary inference. During this process, the same input was re-submitted to the model to observe whether it could eventually produce a semantically appropriate output. If a valid semantic response was generated within the five attempts, it was still counted toward the effective response rate. Otherwise, the word pair was considered an invalid response and excluded from the final statistics. This multi-round inference strategy enhances the objectivity and robustness of the evaluation by reducing the influence of incidental generation errors or random initialization artifacts. By repeatedly verifying outputs across multiple rounds, it ensures that isolated failures are distinguished from systematic weaknesses, thereby preventing transient errors from disproportionately lowering a model’s performance. At the same time, this mechanism improves cross-model comparability by providing each model with equivalent opportunities to recover from initial failures, resulting in a fairer and more reliable assessment of their true capabilities.

As shown in Table 6, all large language models achieved an effective response rate above 98.6%, indicating a generally high level of stability in semantic similarity tasks. However, some differences among models can still be observed. ChatGPT-4 achieved the highest response stability with 99.8%, followed closely by ChatGPT-3.5-turbo (99.7%) and DeepSeek-7B (99.6%). In contrast, Bloom-7B1 recorded the lowest response rate, at only 98.6%. These results suggest that more advanced models tend to exhibit better robustness and stability in handling semantic tasks, whereas earlier-generation or computationally constrained models (e.g., Bloom-7B1) are more prone to inference failures or instability. Notably, these findings are consistent with the performance trends observed in Table 3, where stronger models such as the ChatGPT series and DeepSeek-7B achieved significantly higher r and ρ correlations in semantic similarity computation tasks than models like Bloom-7B1 and the Qwen series. This indicates that models with superior semantic understanding and matching capabilities also demonstrate higher inference reliability. Overall, the analysis of effective response rates further validates that higher-performing models not only excel in similarity scoring metrics, but also maintain greater consistency and reliability across multiple inference rounds, reducing the likelihood of producing unreasonable outputs.

Limitations

This section analyses the WSLE framework on a single RTX-4090 GPU from three perspectives—computational complexity, resource consumption, and hallucination-induced redundancy in cold-start scenarios—using Qwen-7B-Chat as the representative large language model and Sentence-BERT as the embedding model, thereby delineating the framework’s operational bounds and proposing avenues for subsequent optimisation.

Computational complexity

From a theoretical standpoint, the inference overhead is dominated by the number of model parameters and the cost of self-attention. The decoder-style large language model Qwen-7B-Chat contains approximately 7 B parameters (≈ 7721 MiB) and, for a sequence of length L, performs O(L2dmodel) global attention operations for every layer while generating tokens sequentially, limiting parallelism. In contrast, the encoder-style Sentence-BERT has only 110 M parameters (≈ 109 MiB); although it also incurs O(L2) attention, the substantially smaller constant factors and its fully parallel computation yield far lower time and memory requirements. Consequently, Qwen-7B-Chat is expected to exhibit markedly higher latency and peak memory usage during inference.

The experimental results confirmed this analysis. Table 7 shows that, on an RTX-4090 GPU, Qwen-7B-Chat requires 5980–6226 ms to process sequences of 128–512 tokens, whereas Sentence-BERT completes the same inputs in 2.2–2.7 ms—three orders of magnitude faster. Although Qwen-7B-Chat possesses roughly 70 × more parameters, its sequential decoding further amplifies the latency gap. Figure 11 illustrates that the latency of Qwen-7B-Chat increases slightly with sequence length, while Sentence-BERT remains virtually unchanged, indicating that the quadratic attention term is effectively masked by GPU parallelism for the smaller model.

Both the theoretical complexity assessment and the empirical results demonstrate that parameter scale and decoding parallelism determine the asymptotic inference efficiency. Within the proposed framework, the semantic generation and reasoning executed by the large language model constitute the principal contributor to overall computational complexity and runtime, whereas the impact of lightweight encoders such as Sentence-BERT on total latency is negligible.

Resource requirements

From the perspective of the WSLE framework, peak GPU memory arises from the combined footprint of the two sequential stages that run on a single card. During the semantic-generation stage, Qwen-7B-Chat must keep all 7.7 billion parameters resident; in FP16 this alone accounts for roughly 14.3 GiB. Intermediate activations add only a few hundred MiB because they scale with O(L d × layers) and L never exceeds 512. When the pipeline hands control to the lightweight encoding stage, Qwen-7B-Chat is unloaded and Sentence-BERT is loaded, whose 110 million parameters occupy merely 0.21 GiB; however, PyTorch’s CUDA allocator and flash-attention work-spaces reserve about 13 GiB irrespective of model size. Consequently, theory predicts a dual-plateau behaviour: During the LLM stage the memory footprint is expected to stabilise in the vicinity of 15 GiB, because the parameters dominate any other contribution; once the encoder alone is active, it drops to roughly the 13–14 GiB range, where framework-level buffers become the primary factor. Across the tested sequence lengths (128 – 512 tokens) the curve should vary by no more than about one per cent, leaving it effectively flat for practical purposes.

Table 7 and Fig. 12 jointly substantiate the theoretical prediction: while the WSLE pipeline runs Qwen-7B-Chat, peak GPU memory remains effectively constant at 14,821 MiB for input lengths of 128, 256, and 512 tokens, with deviations below half a percent—clear evidence that the model’s weight matrix dominates and sequence-dependent activations add only a negligible increment. Once the LLM is unloaded and Sentence-BERT takes over, the peak settles in the 13,618–13,624 MiB band, a rise of just 6 MiB (0.04%) as the input length quadruples, showing that PyTorch’s allocator and kernel work-spaces now set the floor and that activations remain inconsequential. The nearly horizontal orange and blue traces in Fig. 11 mirror these figures, decisively confirming that, within the WSLE framework, model scale—not sequence length—determines peak GPU memory in both stages.

In summary, the WSLE pipeline’s peak GPU memory is determined first by the LLM’s parameter bulk and subsequently by the runtime buffer reservation that remains when the encoder takes over; across the tested range of 128–512 tokens, sequence length introduces less than one per-cent overhead. Thus, within this framework, module scale rather than input length is the decisive factor that governs resource requirements.

Hallucination‐induced redundancy in cold-start

Cold-start generation arises when the language model must reply without dialogue history or retrieved context. Deprived of external cues, it defaults to the safest high-probability phrases embedded in its parameters, recycling a compact lexical nucleus across successive outputs. Using the rare biomedical term “ambidextrous” as the prompt, we generated six independent continuations; Fig. 13 visualizes their pair-wise Jaccard overlap: more than half of the off-diagonal coefficients exceed 0.45 and several climb above 0.80, indicating that different runs share a large fraction of their unique tokens. Figure 14 complements the results—output length drops from forty-five to about thirty tokens after the first pass and then stabilizes between eighteen and twenty-one. The pattern extends to specialized vocabulary: the Fig. 6d MED38 residual heat-map is dominated by cool tones, showing that every evaluated model under-predicts human similarity scores for rare biomedical terms; the same recycling tendency leaves domain-specific language poorly represented.

The WSLE framework acts on two fronts. Its length gate enforces the narrow 18 to 21 token band, keeping runtime and memory predictable, and its mild repetition penalty trims some lexical reuse. The controls reduce computational waste, however, the consistently high Jaccard coefficient and the negative MED38 value indicate that relying solely on WSLE is not sufficient to ensure true novelty or domain consistency. More diverse decoding or context retrieval operations are needed to completely eliminate the redundant phenomena during the cold-start stage.

Conclusion