Abstract

As a common mental health problem among elderly women, depressive symptoms can lead to serious consequences. Consistent evidence has demonstrated that perceived stress, an individual’s subjective feelings and psychological responses to life events, is a stable risk factor for depressive symptoms in the elderly. However, little is known about the neurobiological correlates of perceived stress and the brain-stress mechanisms to predict depressive symptoms in the older population. In the research reported here, we used a voxel-based morphometry method based on structural magnetic resonance imaging to calculate grey matter volume (GMV) in the brain to study these issues in 120 older women. Whole-brain correlation analyses and predictive analyses showed that greater GMV in the right orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) was consistently associated with higher levels of perceived stress. Mediation analyses further indicated that perceived stress mediated the linkage of right OFC GMV to depressive symptoms. Importantly, these results remained even after adjusting for anxiety symptoms, showing a nature of specificity. Overall, our study may identify a new neuroanatomical marker of perceived stress in older women and suggest a potential neuropsychological pathway for the prediction of depressive symptoms in the elderly, in which the right OFC GMV is associated with depressive symptoms through perceived stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As one of the most important indicators of mental health in old age1 depressive symptoms refer to the negative emotional responses to internal and external environmental stimuli, accompanied by manifestations of reduced mental energy, low mood, sadness, and distress, which can interfere with an individual’s daily lives2,3. Evidence from the epidemiological studies has shown that the detection rate of depressive symptoms in older adults (aged ≥ 60 years) is as high as 37.52%4, with a higher detection rate in females than males5,6,7. It has been reported that persistent and excessive depressive symptoms would lead to depressive disorders8, a serious and prevalent disease that can impair one’s daily life and contribute to suicide in severe cases9, which has become a significant risk factor for all-cause death in the elderly10. Moreover, depressive symptoms in the elderly may also lead to other neuropsychiatric disorders (such as alzheimer’s disease11, anxiety disorder12 and many physical diseases (such as cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases13,14 and endocrine diseases15. Given the high prevalence of depressive symptoms in older people (particularly in older women) and their potentially serious adverse effects, research on the potential risk factors of depressive symptoms in this population is imperative.

As such a factor, perceived stress refers to the degree to which individuals assess external stressful events as stressful, uncontrollable, and unpredictable16. Older individuals’ perceived stress will largely cause mood changes: the more pressure they feel, the more likely they are to have a bad mood; and if the pressure is not effectively released for an extended period, then symptoms of depression may occur17. Numerous previous studies have shown that perceived stress is a significant predictor for the onset and development of depressive symptoms in older populations17,18,19,20. For instance, many cross-sectional studies have confirmed the positive association between perceived stress and depressive symptoms in different groups of older people18,19,20,21. In addition, some longitudinal studies have shown that the elderly’s perceived stress can predict their subsequent depressive symptoms17,22,23. Furthermore, several intervention studies have shown that stress intervention training not only reduces the levels of perceived stress but also has a favorable effect on depressive symptoms in older populations24,25,26,27. In sum, perceived stress might be a stable risk factor for depressive symptoms in older people.

Although the predictive effect of perceived stress on depressive symptoms in the elderly is well established, we know little about the neuroanatomical correlates of perceived stress in this population. With the development of neuroimaging techniques (especially magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) over the past two decades, more and more research has been devoted to exploring the relationship between brain structure and perceived stress28,29,30,31. Evidence from the extant literature has suggested that perceived stress is primarily associated with structural variability in brain regions in the prefrontal-limbic system loop, such as the whole prefrontal cortex32,33, dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex34,35, medial prefrontal cortex36, orbitofrontal cortex (OFC)37,38, hippocampus39,40,41, and amygdala36,42,43. However, most of these previous studies have been limited to adolescents35,36,39,40,43,44, and middle-aged adults33,45, leaving a knowledge gap regarding the neuroanatomical correlates of perceived stress in older people. To date, there is a paucity of research on the relationship between perceived stress and brain structure in older population, and these studies have been almost exclusively devoted to revealing the link of perceived stress with the structure of the hippocampus41,46,47, with little attention paid to changes in the structure of other brain regions in the prefrontal-limbic system loop. Therefore, far more work is necessary to obtain a better understanding of the brain structural correlates of perceived stress in the elderly population.

In light of the above, the current study was aimed to examine the structural brain correlates of perceived stress and explore the brain-stress mechanism in predicting depression symptoms in a sample of older adults. To this end, we scanned all participants using structural MRI and assessed their depressive symptoms and perceived stress levels using standard measures. Here, we used the voxel-based morphometry (VBM) method to measure brain grey matter volume (GMV)48,49 because the GMV assessed with VBM reflects the total volume of the grey matter compartment between the white matter boundary and the pial surface, which is roughly positively correlated with the number of neurons, and has become a major index for studying brain–behavior association50. We first performed whole-brain correlation and predictive analyses to identify brain regions whose GMV associated with perceived stress. Based on existing studies of structural neural correlates related to perceived stress, we hypothesized that GMV in prefrontal-limbic brain regions (e.g., the OFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, medial prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala) might be related to perceived stress. Next, we conducted mediation analyses to explore the relationship between perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and GMV. Based on the links of the elderly’s depressive symptoms with perceived stress17,19,20,22 and prefrontal-limbic system loop51,52,53,54, we further speculate that some brain regions related to perceived stress may also be related to depressive symptoms, and perceived stress may play an intermediary role in the relationship between GMV and depressive symptoms. Finally, to check the specificity of the findings, supplementary analyses were done to exclude the confounding effects of anxiety symptoms.

Particularly, the present study focused on a group of general old women population. Previous brain imaging studies have shown that males and females are inherently somewhat different in terms of brain structural and functional organization55, and that females can exhibit even greater differences in brain structure than males during brain aging56,57. On the other hand, older women are more prone than men to the perception of stress58 and depression symptoms5,7,59,60. Thus, focusing on a single sex alone may rule out the potentially confounding effects of sex on the results; and a better understanding of the sex-specific neural markers of perceived stress and their relations to depressive symptoms may help inform precision medicine in early identification, intervention, and improved health outcome.

Methods

Participants

The data for this study were derived from the baseline assessment of a larger project investigating the neural mechanisms of psychotherapy (ChiCTR2100041831). Participants were community-dwelling older women recruited from Chengdu, China, through poster and advertisement campaigns. The inclusion criteria are: (a) Women aged 60 and over; (b) communication is barrier-free, or communication is barrier-free after sight and hearing correction; (c) Chinese sharp-handed questionnaire61 rated right-handed people; (d) informed consent and voluntary participation in this study. Exclusion criteria include: (a)T1-weighted MRI shows a cerebral infarction (lacunar cerebral infarction > 15 mm) or other cerebrovascular diseases; (b) diseases that may lead to changes in brain tissue, such as metastasis tumor disease, severe hypertension, or diabetes; unstable physical conditions, such as severe asthma, epilepsy, brain tumors, and other neurodegenerative diseases; Physical diseases that may cause mood disorders, such as multiple sclerosis, thyroid diseases, chronic pain, etc.; (c) persons with a previous diagnosis or current mental disorder; (d) a history of psychotropic substances or alcohol abuse in the last 2 months; (e) people suffer from claustrophobia or contraindications to MRI(such as metal implants); (f) participants in other research projects during the study period; (g) participants who provided invalid questionnaires or withdrew from the study.

From October 2021 to August 2023, 132 older women agreed to participate in this study and were screened. Twelve participants were excluded according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, so 120 older women (ages ranging from 60 to 83 years, with a mean age of 68.46 ± 5.06 years) who met the criteria were finally included in the data analysis.

Ethics statement

The research has been approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the Clinical Hospital of Chengdu Institute of Brain Science, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, with a review number [2020], and an ethical examination number (37). All subjects were informed about the study and signed written informed consent before participation. This study meets the requirements of the Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association. Additionally, this study has been registered at the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry. The trial registration number is ChiCTR2100041831, and the date of first registration is 07/01/2021.

Behavioral measure

10-item perceived stress scale (PSS-10)

The PSS-10 is a widely used tool to evaluate the degree of stress people have felt in the past month62,63. The scale comprises 10 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = “Never” to 5 = “Always”). Items 4, 5, 7, and 8 are reverse-scored. The total score ranges from 10 to 50, with higher scores indicating greater perceived stress. The scale has been used to assess levels of stress perception in various Chinese populations (including community-dwelling older adults) and has demonstrated satisfactory internal reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.70–0.91) and retest reliability (r = 0.68–0.70), as well as external validity with relations to symptoms of depression and anxiety64,65,66,67,68. Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale in this study is 0.86, showing an adequate internal reliability.

Center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES-D)

To assess subjects’ depressive symptoms, we employed the CES-D, which consists of 20 questions and the subjects are required to rate the frequency of symptoms in the last week on a scale of 0 to 3, with a total score ranging from 0 to 60 and the higher the score, the more serious the depressive tendency of the subjects69,70. The scale has been widely used in the assessment of depression symptoms in different populations and has shown satisfactory psychometric properties71,72,73. In China, the CES-D has been repeatedly applied to different groups of older adults, such as elderly diabetics, rural older adults, elderly hypertensive patients, and elderly veterans in the community and has shown adequate reliability and validity74,75,76,77. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of this scale is 0.92 in this study, showing a satisfied internal reliability.

Self-Rating anxiety scale (SAS)

Since many existing studies have found that anxiety symptom is associated with depressed symptom78,79, perceived stress80,81, and brain structure82,83, we used the SAS84 to test whether anxiety symptom would influence the associations between GMV, perceived stress and depression symptoms. The scale comprises 20 items, each assessed on a 4-point Likert scale (from 0 = “Not at all” to 3 = “All the time”), yielding a total score from 0 to 60, where higher scores indicate increased anxiety levels84. The scale has been widely used with various groups of Chinese elderly, including those in nursing homes, communities, and empty nesters; and it has demonstrated good internal reliability and validity in these demographics85,86,87,88. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of SAS in this study was 0.77, showing an adequate internal reliability.

MRI image acquisition and pre-processing

MRI image acquisition was done with a Siemens 3.0T (MAGNETOM Skyra) MRI scanner and a 32-channel phased-array head coil in the Department of Radiology of the Fourth People’s Hospital of Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China. T1-weighted structural images of each subject were obtained using magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo sequence with acquisition parameters including: repetition time = 2300 ms, echo time = 2.32 ms, field of view = 240 × 240 mm3, matrix = 256 × 256, voxel size = 0.9 × 0.9 × 0.9 mm3, flip angle = 8°, slices = 192. To minimize head movement, we fixed the subjects’ heads with foam pads. To attenuate the noise of the machine scanning, we instructed all subjects to wear disposable professional earplugs.

S-MRI preprocessing was done using the Automated Computational Anatomy Toolbox (CAT12, https://www.dbm.neuro.uni-jena.de/cat12/), based on SPM12 software (https://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm12/ ). Preprocessing was performed using the following steps: first, to ensure data quality, all images were displayed in SPM12 to screen for artifacts or structural damage. For better image alignment, the anterior commissure-posterior commissure coordinates were manually adjusted so the origin coordinates were in the anterior commissure region. Next, the image is segmented into white matter, grey matter, and cerebrospinal fluid using the “New Segmentation” method in SPM12. In the third step, alignment, normalization, and modulation analyses were performed using the DARTEL (Diffeomorphic Anatomical Registration Through Exponential Lie algebra) method89. That is, all grey matter images were aligned and resampled to a spatial resolution of 1.5 mm3 and then normalized to Montreal Neurological Institute space (MIN). The segmented grey matter was modulated using the inverse Jacobi matrix of the local transforms to measure brain volume. Then, the image data is smoothly modulated (Gaussian kernel is 8 mm3) to reduce registration inaccuracy and improve the signal-to-noise ratio. Finally, to eliminate edge effects at the boundary between grey and white matter, we masked the generated image with an absolute threshold template of 0.290.

Statistical analyses

Whole-brain correlation analysis

To identify the brain regions in which GMV is associated with perceived stress, we performed a whole-brain correlation analysis between perceived stress scores and voxel wise GMV values, with age, education level, income, and total GMV as control variables. Random field theory (RFT) was then used for multiple comparison corrections (voxel level: p < 0.001, cluster level: p < 0.05)91. This method has been shown to be useful in voxel-based GMV studies to determine significant results90,92,93.

Confirmatory cross-validation analysis

We then examined the robustness of the relationship between perceived stress and brain structure using a linear regression approach based on balanced cross-validation machine learning90,94,95. In the regression model, GMV, which is particularly related to perceived stress, was used as the independent variable (X) and PSS-10 scores as the dependent variable (Y). The data were first randomly divided equally into four portions to ensure that the distributions of both the X and Y were balanced in each portion. Next, any three of these were extracted to construct a linear regression model, which was used to make predictions on the remaining data. This training and testing process was performed four times to obtain the average of the correlation coefficients of the observed and predicted values (r (predicted, observation)), which represents how well the X can predict the Y. The significance of r (predicted, observation) was tested using a non-parametric test with 5000 iterations96,97. The analysis was done by controlling for age, education level, income, and total GMV.

Mediation analysis

We conducted mediation analyses using SPSS macro PROCESS98 to explore whether perceived stress plays a mediating role between GMV and depressive symptoms. In the analysis, GMV of brain regions associated with perceived stress was used as the X, perceived stress scores as the mediator variable (M), depression scores as the Y, and age, education level, income, and total GMV as control variables. The analysis has four paths, including path a (representing the relationship between X and M), path b (the relationship between M and Y after controlling for the effect of the X), path c (representing the relationship between X and Y) and path c’ (representing the relationship between X and Y after controlling for the effect of the M), as well as the indirect effect of being path c minus path c’ (or path a × path b)99. Statistical significance was determined using the bootstrapping method (5000 iterations), and estimates of indirect effects were considered significant when not spanning zero in the 95% confidence interval (CI)100. To explore the directionality of the links between GMV, perceived stress, and depressive symptoms, we conducted another mediation analysis with perceived stress scores as the X, GMV of brain regions associated with perceived stress as the M, depressive symptoms as the Y and age, education level, income, and total GMV as the control variables.

Results

Behavior results

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, ranges, and bivariate correlations of the behavioral variables measured in this study. As expected, perceived stress had a positive correlation with depressive symptoms (r = 0.51, p < 0.001). This correlation remained even after adjusting for age, education level and income (r = 0.53, p < 0.001). In addition, perceived stress had no significant correlations with age (r = -0.06, p = 0.526), education level (r = -0.01, p = 0.928), or income (r = -0.11, p = 0.218).

GMV correlates of perceived stress

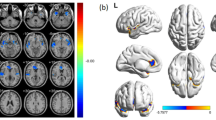

Whole brain correlation analysis based on age, education level, income, and total GMV as control variables showed a positive correlation between GMV in the right OFC and perceived stress (r = 0.36, p < 0.001; Table 2; Fig. 1). No brain area with a negative correlation between GMV and perceived stress was found in this analysis. To test the stability of the relationship between GMV and perceived stress identified in the whole-brain correlation analyses, we performed a confirmatory cross-validation analysis. The results showed that after adjusting for age, education, income, and total GMV, the GMV of the right OFC was reliably linked with the perceived stress scores. (r = 0.31, p < 0.001).

GMV correlates of perceived stress. Brain images show that GMV in the right OFC was positively correlated with perceived stress. The scatter plot shows the correlation between the GMV of the right OFC and the perceived stress scores. Scores on the x-axis represent raw perceived stress scores, and scores on the y-axis represent standard residuals of OFC volume after regression out age, education level, income and total GMV. OFC = orbitofrontal cortex; GMV = Grey Matter Volume.

GMV linking perceived stress to depressive symptoms

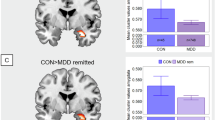

To test the hypothesis that GMV influences depressive symptoms in older women through perceived stress, we performed correlation and mediation analyses. First, correlation analysis with age, education level, income, and total GMV as control variables showed a positive correlation (r = 0.21, p = 0.022) between depressive symptoms and right OFC GMV that was linked with perceived stress. Then, mediation analysis with age, education level, income, and total GMV as control variables found that perceived stress had a significant indirect effect on the relationship between GMV in the right OFC and depressive symptoms (indirect effect = 0.18, 95% CI = [ 0.09, 0.30], p < 0.05, Fig. 2). In summary, perceived stress may mediate the relationship between GMV in the right OFC and depressive symptoms in older women.

To explore the directionality of the relationship among GMV, perceived stress, and depressive symptoms, we conducted another mediation analysis with perceived stress as the X, GMV in right OFC as the M, and depressive symptoms as the Y. The results showed that the indirect effect of this mediation model was not significant (indirect effect = 0.01, 95% CI= [-0.05, 0.08], p > 0.05). Thus, there may be only one valid neuropsychological pathway for predicting depressive symptoms in older women, in which GMV in the right OFC is linked to depressive symptoms via perceived stress.

Supplementary analyses

To examine the specificity of our main findings, we interrogated our results when controlling for anxiety scores as an additional confounding factor. In correlation analyses, perceived stress was still positively associated with depressive symptoms (r = 0.31, p < 0.001) and GMV of the right OFC (r = 0.33, p < 0.001) after adding SAS scores as another control variable. Subsequently, in the cross-validation analysis, the right OFC can still reliably predict the individual differences of perceived stress (r = 0.28, p = 0.002) after additionally adjusting SAS score. Importantly, after SAS score was included as a covariant, the mediating effect of perceived stress was still significant for the link of right OFC with depression symptoms (indirect effect = 0.10, 95% CI = [0.04, 0.19], p < 0.05). Therefore, although anxiety can affect the effect of the results, our research results have a specific nature to some degree.

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the brain structural correlates of perceived stress in an older female population and to explore the potential brain-stress mechanisms that predict depressive symptoms. Two main results were found: firstly, greater GMV in the right OFC was associated with higher levels of perceived stress. Secondly, perceived stress served as an intermediary to explain the relationship between the right OFC GMV and depression symptoms. Notably, these results remained even after adjusting for anxiety symptoms, indicating the specificity of the results. Overall, the current research provides new evidence for the neuroanatomical correlates of perceived stress in older women and reveals a potential neuropsychological pathway for predicting depressive symptoms, namely that the right OFC GMV is associated with depressive symptoms through perceived stress.

Consistent with our first guess, the GMV in the right OFC was positively correlated with perceived stress levels. This finding aligns with the results reported by Wu et al. in an adolescent cohort101, thereby providing further evidence to support the structural role of the OFC in human stress perception. It is well established that the prefrontal cortex, particularly the right OFC, plays a key role in stress regulation and emotion management102,103. Alterations in its structure may directly influence an individual’s sensitivity to stress, thereby modulating their subjective perception of stress levels104,105,106. Second, studies have shown that neuronal dendritic morphology is a key factor influencing the GMV107. Increases in GMV may be associated with dendritic branching, synaptogenesis, and increased vascularisation108. Thus, an increase in GMV in the right OFC may be accompanied by dendritic expansion and enhanced synaptic input. Such structural changes could lead to increased anxiety and vigilance, subsequently elevating perceived stress109. Third, the OFC plays a crucial role in emotional processing and goal-directed behavior, regulating an individual’s socially adaptive behaviours that help individuals adapt to a dynamic and changing social environment101,110. When the OFC is volumetrically altered or damaged, people tend to make catastrophic life choices111; in addition to making poor decisions, they often engage in inappropriate, impulsive behaviors that result in their inability to adapt to the laws of social survival112,113. Given that perceived stress is characterized by the individuals’ subjective feelings to perceive changes in the surrounding environment, when the individuals are maladaptive to environmental and social changes, it may generate more stress perception114. Thus, there is a positive correlation between the change in right OFC GMV and the change in perceived stress levels.

The noteworthy fact is that we reveal that perceived stress mediates the relationship between right OFC GMV and depressive symptoms. At the behavioral level, the positive correlation between perceived stress and depressive symptoms has been well-established in different groups of older adults17,19,20,22. Even after adjusting for age, level of education, income, total GMV, and anxiety symptoms, this correlation is maintained in the current sample. Thus, our results provide new evidence that perceived stress is a significant predictor of depressive symptoms in older women. At the brain structural level, we observed a positive correlation between right OFC GMV and depressive symptoms. This is similar to the finding of a VBM study in 49 community boys that GMV of OFC was positively associated with the severity of depressive symptoms115. The increase in cortical thickness of OFC has also been reported to be positively correlated with the depressive symptoms in female adolescents116 and patients with temporal lobe epilepsy117. In addition, structural and functional variants of the OFC have been widely reported in depressed patients118,119,120,121. It is well known that the OFC is a typically emotionally connected region closely related to the processes of subjective experience, cognitive appraisal and control of emotions122, in which the right OFC is more involved in the cognitive processing of negative emotions123. Therefore, the increase in the GMV of the right OFC may lead to heightened proper OFC-amygdala neural communication in older women. This process is closely associated with greater susceptibility to negative emotions and more severe depressive symptoms124,125. The OFC is one of the core nodes of the reward system, a subcortical network in the brain region that focuses on delivering pleasure anticipation and experience-related services126,127. Increased GMV in the right OFC may imply right > left asymmetry of the OFC, and previous studies have shown that asymmetry of the OFC, particularly thickening of the right OFC, is highly positively correlated with anhedonia128. Anhedonia is a core symptom of depressive symptoms129. Therefore, an increase in the GMV of the right OFC is associated with more severe depressive symptoms. The current research results show that the increase in GMV in the right OFC may impair its ability to process stress and regulate behavior. These alterations are closely linked to higher levels of perceived stress, subsequently increasing negative emotions and ultimately exacerbating depressive symptoms. Overall, our findings suggest that perceived stress is a potential mechanism linking right OFC and depressive symptoms.

There are some limitations in current research. First, as the study participants were restricted to older women without a history of mental disorders, the generalizability of the findings may be limited. Consequently, future studies are needed to validate these results in other populations, such as older men and clinically depressed patients. Second, the behavioral measures were only assessed through self-rating scales, although these have been shown to have good reliability and validity65,77,88. In the future, researchers can adopt various testing methods (such as adding other evaluations or experimental designs) to reduce the interference of subjects’ subjective bias on variable measurement130. Third, the history of mental disorders was primarily ascertained through participant self-report. Consequently, this approach may have precluded the identification of undiagnosed cases and is potentially susceptible to recall or social desirability bias, which could have influenced the study outcomes. Fourth, this study only used VBM to analyze the relationship between brain GMV and perceived stress and found that only one brain region, the right OFC, was associated with perceived stress in older women, while other brain regions (e.g., dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex34,35 previously reported to be associated with perceived stress were not found. In the future, other methods, such as diffusion tensor imaging131 and surface-based morphological analysis132, can be used to provide a more comprehensive statistical analysis of the subtle changes in brain structure associated with perceived stress. Finally, this study was cross-sectional, and the intermediary analyses are statistical, so it is impossible to get the causal relationship between GMV, perceived stress, and depression symptoms. Future studies could use longitudinal design to determine the causal relationship between these variables.

In summary, the present study reveals a new neural correlate of perceived stress, i.e., GMV in the right OFC is positively associated with perceived stress, in an older female population. Furthermore, our study provides fresh evidence for the mediating role of perceived stress in the relationship between right OFC GMV and depressive symptoms. These findings together indicate that the right OFC GMV and perceived stress play a key role in the depressive symptoms of older women and provide a new perspective for studying how the brain structure affects depressive symptoms via individual psychological characteristics. Importantly, our findings may be helpful for future healthcare workers to formulate behavioral training courses133 or neural intervention measures134for target brain regions to reduce the perceived stress level of older women and reduce their depressive symptoms.

Data availability

Due to the privacy and ethical restrictions of the subjects, the data supporting the results of this study are not publicly provided, but can be obtained from the communication author on reasonable request.

References

Lei, X., Sun, X., Strauss, J., Zhang, P. & Zhao, Y. Depressive symptoms and Ses among the Mid-Aged and elderly in china: evidence from the China health and retirement longitudinal study National baseline. Soc. Sci. Med. 120, 224–232 (2014).

Cheruvu, V. K. & Chiyaka, E. T. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among older adults who reported medical cost as a barrier to seeking health care: findings from a nationally representative sample. Bmc Geriatr 19, 142 (2019).

Dubovsky, S. L., Ghosh, B. M., Serotte, J. C. & Cranwell, V. Psychotic depression: diagnosis, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Psychother. Psychosom. 90, 160–177 (2021).

Xie, Y. et al. Factors associated with depressive symptoms among the elderly in china: structural equation model. Int. Psychogeriatr. 33, 157–167 (2021).

Hargrove, T. W. et al. Race/Ethnicity, Gender, and trajectories of depressive symptoms across Early- and Mid-Life among the add health cohort. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities. 4, 619–629 (2020).

Rivera Navarro, J., Benito-León, J. & Pazzi Olazarán, K. A. La depresión En La vejez: un importante problema de Salud En México. América Latina Hoy. 71, 103–118 (2015).

Tang, T., Jiang, J. & Tang, X. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among older adults in Mainland China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 293, 379–390 (2021).

Tengku Mohd, T. A. M., Yunus, R. M., Hairi, F., Hairi, N. N. & Choo, W. Y. Social support and depression among community dwelling older adults in Asia: a systematic review. Bmj Open. 9, e26667 (2019).

Hawton, K., Comabella, C. C. I., Haw, C. & Saunders, K. Risk factors for suicide in individuals with depression: a systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 1–3, 17–28 (2013).

Diniz, B. S. et al. The effect of Gender, Age, and symptom severity in Late-Life depression on the risk of All‐Cause mortality: the Bambuí cohort study of aging. Depress. Anxiety. 31, 787–795 (2014).

Dal Forno, G. et al. Depressive symptoms, sex, and risk for alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 57, 381–387 (2005).

Jacobson, N. C. & Newman, M. G. Anxiety and depression as bidirectional risk factors for one another: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Bull. 143, 1155–1200 (2017).

Harshfield, E. L. et al. Association between depressive symptoms and incident cardiovascular diseases. JAMA: J. Am. Med. Association. 324, 2396–2405 (2020).

Krishnan, K. R. R. Depression as a contributing factor in cerebrovascular disease. Am. Heart J. 140, S70–S76 (2000).

Hestad, K. A., Aukrust, P., Tønseth, S. & Reitan, S. K. Depression has a strong relationship to alterations in the Immune, endocrine and neural system. Curr. Psychiatry Rev. 5, 287–297 (2009).

Cohen, S. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 4, 385–396 (1983).

Tsai, A. C., Chi, S. & Wang, J. The association of perceived stress with depressive symptoms in older Taiwanese—Result of a longitudinal National cohort study. Prev. Med. 57, 646–651 (2013).

Brown, L. L., Abrams, L. R., Mitchell, U. A. & Ailshire, J. A. Measuring more than exposure: does stress appraisal matter for Black-White differences in anxiety and depressive symptoms among older adults? Innov. Aging. 4, a40 (2020).

Chen, Y., Peng, Y., Ma, X. & Dong, X. Conscientiousness moderates the relationship between perceived stress and depressive symptoms among U.S. Chinese older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. A-Biol Sci. Med. Sci. 72, S108–S112 (2017).

Deeken, F. et al. Psychometric properties of the perceived stress scale in a sample of German dementia patients and their caregivers. Int. Psychogeriatr. 30, 39–47 (2018).

Da Silva-Sauer, L. et al. Psychological resilience moderates the effect of perceived stress on Late-Life depression in Community-Dwelling older adults. Trends Psychol. 29, 670–683 (2021).

Chao, S. Functional disability and depressive symptoms:longitudinal effects of activity Restriction, perceived Stress, and social support. Aging Ment Health. 18, 767–776 (2014).

Dautovich, N. D., Dzierzewski, J. M. & Gum, A. M. Older adults display concurrent but not delayed associations between life stressors and depressive symptoms: a microlongitudinal study. Am. J. Geriatric Psychiatry. 22, 1131–1139 (2014).

Ernst, S. et al. Effects of Mindfulness-Based stress reduction on quality of life in nursing home residents: a feasibility study. Forsch. Komplementmed. 15, 74–81 (2008).

Kumar, S., Adiga, K. R. & George, A. Impact of Mindfulness-Based stress reduction (Mbsr) on depression among elderly residing in residential homes. Nurs. J. India. 6, 248–251 (2014).

Lindayani, L., Hendra, A., Juniarni, L. & Nurdina, G. Effectiveness of mindfulness based stress reduction on depression in elderly: a systematic review. J. Nurs. Pract. (Online). 4, 8–12 (2020).

Rasing, N. L. et al. The impact of music on stress biomarkers: protocol of a substudy of the Cluster-Randomized controlled trial music interventions for dementia and depression in elderly care (Middel). Brain Sci. 12, 485 (2022).

Cardoner, N. et al. Impact of stress on brain morphology: insights into structural biomarkers of stress-Related disorders. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 22, 935–962 (2024).

Katarina, D., D’Aguiar, C. & Pruessner, J. C. What stress does to your brain: a review of neuroimaging studies. Can. J. Psychiatry. 54, 6–15 (2009).

Pruessner, J. C. et al. Stress regulation in the central nervous system: evidence from structural and functional neuroimaging studies in human populations – 2008 Curt Richter award winner. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35, 179–191 (2010).

Zhang, L., Gu, J., Chen, Z., Wang, S. & Gong, Q. The neural mechanism underlying perceived stress: evidence from Psych-Magnetic resonance imaging. Chin. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 11, 66–70 (2020).

Moreno, G. L., Bruss, J. & Denburg, N. L. Increased perceived stress is related to decreased prefrontal cortex volumes among older adults. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 39, 313–325 (2017).

Rubin, L. H. et al. Prefrontal cortical volume loss is associated with Stress-Related deficits in verbal learning and memory in Hiv-Infected women. Neurobiol. Dis. 92, 166–174 (2016).

Blix, E., Perski, A., Berglund, H. & Savic, I. Long-Term occupational stress is associated with regional reductions in brain tissue volumes. Plos One. 8, e64065 (2013).

Michalski, L. J. et al. Perceived stress is associated with increased rostral middle frontal gyrus cortical thickness: a family-based and discordant‐sibling investigation. Genes Brain Behav. 16, 781–789 (2017).

Savic, I. Structural changes of the brain in relation to occupational stress. Cereb. Cortex. 25, 1554–1564 (2015).

Gianaros, P. J. et al. Prospective reports of chronic life stress predict decreased grey matter volume in the hippocampus. NeuroImage (Orlando Fla). 35, 795–803 (2007).

Shang, Z. et al. Sex-Based differences in brain morphometry under chronic stress: a pilot mri study. Heliyon 10, e30354 (2024).

Burkert, N. T., Koschutnig, K., Ebner, F. & Freidl, W. Structural hippocampal alterations, perceived Stress, and coping deficiencies in patients with anorexia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 48, 670–676 (2015).

Piccolo, L. R. & Noble, K. G. Perceived stress is associated with smaller hippocampal volume in adolescence. Psychophysiology 55, 1452 (2018).

Zimmerman, M. E. et al. Perceived stress is differentially related to hippocampal subfield volumes among older adults. Plos One. 11, e154530 (2016).

Caetano, I. et al. Amygdala size varies with stress perception. Neurobiol. Stress. 14, 100334 (2021).

Holzel, B. K. et al. Stress reduction correlates with structural changes in the amygdala. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 5, 11–17 (2010).

Li, H. et al. Examining brain structures associated with perceived stress in a large sample of young adults via Voxel-Based morphometry. Neuroimage 92, 1–7 (2014).

Gianaros, P. J. et al. Prospective reports of chronic life stress predict decreased grey matter volume in the hippocampus. Neuroimage 35, 795–803 (2007).

De Looze, C. et al. Sleep duration, sleep problems, and perceived stress are associated with hippocampal subfield volumes in later life: findings from the Irish longitudinal study on ageing. Sleep. (New York N Y). 45, 1 (2022).

Zannas, A. S. et al. Negative life stress and longitudinal hippocampal volume changes in older adults with and without depression. J. Psychiatr Res. 47, 829–834 (2013).

Ashburner, J. & Friston, K. J. Voxel-based morphometry—the methods. Neuroimage 11, 805–821 (2000).

Ashburner, J. & Friston, K. J. Why voxel-based morphometry should be used. Neuroimage 14, 1238–1243 (2001).

Thomas, C. & Baker, C. I. Teaching an adult brain new tricks: A critical review of evidence for Training-Dependent structural plasticity in humans. NeuroImage (Orlando Fla). 73, 225–236 (2013).

Anna Pink, M. et al. Cortical thickness and depressive symptoms in cognitively normal individuals: the Mayo clinic study of aging. J. Alzheimers Dis. 58, 1273–1281 (2017).

Dotson, V. M. P., Davatzikos, C. P., Kraut, M. A. M. P. & Resnick, S. M. P. Depressive symptoms and brain volumes in older adults: a longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 34, 367–375 (2009).

Szymkowicz, S. M. et al. Associations between subclinical depressive symptoms and reduced brain volume in Middle-Aged to older adults. Aging Ment Health. 23, 819–830 (2018).

Taki, Y. et al. Male elderly subthreshold depression patients have smaller volume of medial part of prefrontal cortex and precentral gyrus compared with Age-Matched normal subjects: a voxel-based morphometry. J. Affect. Disord. 88, 313–320 (2005).

Ruigroka, A. N. V. et al. A Meta-Analysis of sex differences in human brain structure. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2014, 34–50 (2014).

Ritchie, S. J. et al. Sex differences in the adult human brain: evidence from 5216 Uk Biobank participants. Cerebral cortex (New York, NY:1991) 28, 2959–2975 (2018).

Wierenga, L. M., Sexton, J. A., Laake, P., Giedd, J. N. & Tamnes, C. K. A key characteristic of sex differences in the developing brain: greater variability in brain structure of boys than girls. Cereb. Cortex. 28, 2741–2751 (2018).

Badr, H. E. et al. Childhood maltreatment: a predictor of mental health problems among adolescents and young adults. Child. Abuse Negl. 80, 161–171 (2018).

Nianwei, W. et al. Analysis of the status of depression and the influencing factors in Middle-Aged and older adults in China. J. Sichuan Univ. (Med. Sci.) 52, 767–771 (2021).

Xianjin, X., Jian, W., Tian, G., Jinyang, L. & Jinmin, H. Analysis of the relationship between activities of daily living in old adults in China and chronic disease comorbidity and depressive symptoms. Med. Soc. 36, 123–128 (2023).

LI, X. Chinese People’s left-handed and right-handed distribution. Acta Psychol. Sin 1983, 268–276 (1983).

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T. & Mermelstein, R. A. Global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Social Behav. 24, 385–396 (1983).

Yan, H. et al. Measurement invariance of the perceived stress Scale(Pss-10) between groups with negative and positive depressive symptoms. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 27, 1196–1198 (2019).

Jin, Y., Brown, R., Bhattarai, M., Kuo, W. C. & Chen, Y. Psychometric properties of the Self-Care of chronic illness inventory in Chinese older adults with multiple chronic conditions. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 18, e12536 (2023).

Lu, W. et al. Chinese version of the perceived stress Scale-10: a psychometric study in Chinese university students. Plos One. 12, e189543 (2017).

Ng, S. M. Validation of the 10-Item Chinese perceived stress scale in elderly service workers: one-factor versus two-factor structure. Bmc Psychol. 1, 9 (2013).

Wang, Z. et al. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the perceived stress scale in policewomen. Plos One. 6, e28610 (2011).

Zhang, X., Zhang, X., Lv, Z. & Yang, J. Physical activity, stress and quality of life among community-dwelling older adults in shenzhen during the post-Covid-19 pandemic period. Stress and Quality of Life Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults in Shenzhen During the Post-COVID-19 Pandemic Period(3/21/2022) (2022).

Eaton, W. W., Smith, C., Ybarra, M. & Carles, M. Center for epidemiologic studies depression scale: review and revision. The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment (2004).

Radloff, L. S. & The Ces, D. Scale A Self-Report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1, 385–401 (1977).

Fountoulakis, K. et al. Reliability, validity and psychometric properties of the Greek translation of the center for epidemiological Studies-Depression (Ces-D) scale. Bmc Psychiatry 1, 3 (2001).

Jiang, L. et al. The reliability and validity of the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (Ces-D) for Chinese university students. Front. Psychiatry 10, 1422 (2019).

Natamba, B. K. et al. Reliability and validity of the center for epidemiologic studies-depression scale in screening for depression among Hiv-Infected and -Uninfected pregnant women attending antenatal services in Northern uganda: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 16, 1–11 (2016).

Du, W. et al. Physical activity as a protective factor against depressive symptoms in older Chinese veterans in the community: result from a National Cross-Sectional study. Neuropsychiatric Disease Treatment 2015, 803–813 (2015).

Ma, L. et al. Original Article risk factors for depression among elderly subjects with hypertension living at home in China. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 8, 2923–2928 (2015).

Yang, J. J. et al. The prevalence of depressive and insomnia Symptoms, and their association with quality of life among older adults in rural areas in China. Front. Psychiatry. 12, 727939 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Measuring depression with Ces-D in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes: the validity and its comparison to Phq-9. Bmc Psychiatry. 15, 198 (2015).

Zhang, X. et al. Emotional intelligence mediates the protective role of the orbitofrontal cortex spontaneous activity measured by Falff against depressive and anxious symptoms in late adolescence. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psych. 32, 1957–1967 (2023).

Zhao, W. et al. Depression mediates the association between Insula-Frontal functional connectivity and social interaction anxiety. Hum. Brain Mapp. 43, 4266–4273 (2022).

Lu, W., Chunxiu, F., Qingqing, L. & Quanhui, L. Correlation between perceived stress and Depression/Anxiety in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Int. PSYCHIATRY. 48, 697–699 (2021).

Ying-ying, J., Dan-xiang, H. U., Wu-min, X. U. & Jing, Z. Study on pressure perception and anxiety of Hemodialysis patients during Covid-19 epidemic. Hosp. Manage. Forum. 39, 52–57 (2022).

Etkin, A., Prater, K. E., Schatzberg, A. F., Menon, V. & Greicius, M. D. Disrupted amygdalar subregion functional connectivity and evidence of a compensatory network in generalized anxiety disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 66, 1361–1372 (2009).

Schienle, A., Ebner, F. & Schafer, A. Localized Gray matter volume abnormalities in generalized anxiety disorder. Eur. Arch. Psych Clin. Neurosci. 261, 303–307 (2011).

Zung, W. W. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosom. J. Consult. Liaison Psychiatr 12, 371–379 (1971).

Shi, J., Huang, A., Jia, Y. & Yang, X. Perceived stress and social support influence anxiety symptoms of Chinese family caregivers of Community-Dwelling older adults: A Cross‐Sectional study. Psychogeriatrics 20, 377–384 (2020).

Wang, Z., Shu, D., Dong, B., Luo, L. & Hao, Q. Anxiety disorders and its risk factors among the Sichuan Empty-Nest older adults: a cross-sectional study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 56, 298–302 (2013).

Xiangli, D., Weiming, S. & Yefeng, Y. Status and influencing factors of anxiety among the community elderly in Jiangxi. Mod. Prev. Med. 43, 2378–2381 (2016).

Yang, H. The analysis of the psychological health status of senior citizens from nursing homes in Luoyang, a third line City of China. Malaysian J. Nurs. 11, 63–67 (2020).

Ashburner, J. A. A fast diffeomorphic image registration algorithm. Neuroimage 38, 95–113 (2007).

Wang, S. et al. Neuroanatomical correlates of grit: growth mindset mediates the association between Gray matter structure and trait grit in late adolescence. Hum. Brain Mapp. 39, 1688–1699 (2018).

Hayasaka, S., Phan, K. L., Liberzon, I., Worsley, K. J. & Nichols, T. E. Nonstationary Cluster-Size inference with random field and permutation methods. Neuroimage 22, 676–687 (2004).

Takeuchi, H. et al. A Voxel-Based morphometry study of Gray and white matter correlates of a need for uniqueness. Neuroimage 63, 1119–1126 (2012).

Wang, S. et al. Neurostructural correlates of hope: dispositional hope mediates the impact of the Sma Gray matter volume on subjective Well-Being in late adolescence. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 15, 395–404 (2020).

Wang, S. et al. Stress and the brain: perceived stress mediates the impact of the superior frontal gyrus spontaneous activity on depressive symptoms in late adolescence. Hum. Brain Mapp. 40, 4982–4993 (2019).

Zhang, F. The neuro-mechanism of exercise addiction: a neuroimaging study based on multimodal magnetic resonance imaging: Sichuan University (2021).

Kong, F., Wang, X., Hu, S. & Liu, J. Neural correlates of psychological resilience and their relation to life satisfaction in a sample of healthy young adults. Neuroimage 123, 165–172 (2015).

Supekar, K. et al. Neural predictors of individual differences in response to math tutoring in primary-grade school children. Proc. Natil. Acade. Sci. 110, 8230–8235 (2013).

Hayes, A. F. Introduction To Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis (Guilford Press, 2013).

WEN, Z. & YE, B. Mediation effects analysis: methodological and modelling developments. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 22, 731–745 (2014).

Hayes, A. F. & Scharkow, M. The relative trustworthiness of Inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: does method really matter? Psychol. Sci. 24, 1918–1927 (2013).

Wu, J. et al. Neurobiological effects of perceived stress are different between adolescents and Middle-Aged adults. Brain Imaging Behav. 15, 846–854 (2021).

Protopopescu, X. et al. Orbitofrontal cortex activity related to emotional processing changes across the menstrual cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 102, 16060–16065 (2005).

Wang, J. et al. Gender difference in neural response to psychological stress. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2, 227–239 (2007).

Liston, C. et al. Stress-Induced alterations in prefrontal cortical dendritic morphology predict selective impairments in perceptual attentional Set-Shifting. J. Neurosci. 26, 7870–7874 (2006).

McEwen, B. S. & Morrison, J. H. The brain on stress: vulnerability and plasticity of the prefrontal cortex over the life course. Neuron 79, 16–29 (2013).

McEwen, B. S., Nasca, C. & Gray, J. D. Stress effects on neuronal structure: hippocampus, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacol. (New York N Y). 41, 3–23 (2016).

Zatorre, R. J., Fields, R. D. & Johansen-Berg, H. Plasticity in Gray and white: neuroimaging changes in brain structure during learning. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 528–536 (2012).

Anderson, B. J. Plasticity of Gray matter volume: the cellular and synaptic plasticity that underlies volumetric change. Dev. Psychobiol. 53, 456–465 (2011).

Hunter, R. G. & McEwen, B. S. Stress and anxiety across the lifespan: structural plasticity and epigenetic regulation. Epigenomics 5, 177–194 (2013).

Drevets, W. C. Neuroimaging and neuropathological studies of depression: implications for the Cognitive-Emotional features of mood disorders. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 11, 240–249 (2001).

Yang, X. Effect of orbitofrontal cortex on reward value coding: university of electronic science and technology of China (2020).

Hanson, J. L. et al. Early stress is associated with alterations in the orbitofrontal cortex: a Tensor-Based morphometry investigation of brain structure and behavioral risk. J. Neurosci. 30, 7466–7472 (2010).

Huang, M. & Jia, J. The role of orbital prefrontal cortex in executive function. J. JINING Med. Coll. 28, 66–67 (2005).

Liu, M. The role and molecular mechanism of orbitofrontal cortex-dorsal striatum neural circuit in memory retrieval of methamphetamine addiction: ShangDong university (2023).

Vandermeer, M. R. J. et al. Orbitofrontal cortex grey matter volume is related to children’s depressive symptoms. NeuroImage: Clin. 28, 102395 (2020).

Nielsen, J. D. et al. Trajectories of depressive symptoms through adolescence as predictors of cortical thickness in the orbitofrontal cortex: an examination of sex differences. Psychiatry Res.: Neuroimaging. 303, 111132 (2020).

Butler, T. et al. Cortical thickness abnormalities associated with depressive symptoms in Temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 23, 64–67 (2012).

Eddington, K. M. et al. Neural correlates of idiographic goal priming in depression: goal-Specific dysfunctions in the orbitofrontal cortex. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 4, 238–246 (2009).

Koenig, J. et al. Brain structural thickness and resting state autonomic function in adolescents with major depression. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 13, 741–753 (2018).

Qiu, L. et al. Regional increases of cortical thickness in Untreated, First-Episode major depressive disorder. Transl. Psychiatr. 4, e378 (2014).

Zaremba, D. et al. Association of brain cortical changes with relapse in patients with major depressive disorder. JAMA Psychiatry (Chicago Ill). 75, 484–492 (2018).

Bechara, A., Damasio, H. & Damasio, A. R. Emotion decision making and the orbitofrontal cortex. Cereb. Cortex. 10, 295–307 (2000).

Davidson, R. J. Affective style and affective disorders: perspectives from affective neuroscience. Cogn. Emot. 12, 307–330 (1998).

Ruigrok, A. N. V. et al. A Meta-Analysis of sex differences in human brain structure. Neurosci. Biobehavioral Reviews. 39, 34–50 (2014).

Xiaoquan, W., Yurui, B. & Zusen, W. Research progress on risk factors of female depression. China J. Health Psychol. 23, 1750–1753 (2015).

Bray, S., Shimojo, S. & O’Doherty, J. P. Human medial orbitofrontal cortex is recruited during experience of imagined and real rewards. J. Neurophysiol. 103, 2506–2512 (2010).

Rolls, E. T., Cheng, W. & Feng, J. The orbitofrontal cortex: reward, emotion and depression. Brain Commun. 2, a196 (2020).

Dotson, V. M., Taiwo, Z., Minto, L. R., Bogoian, H. R. & Gradone, A. M. Orbitofrontal and cingulate thickness asymmetry associated with depressive symptom dimensions. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 21, 1297–1305 (2021).

Cooper, J. A., Arulpragasam, A. R. & Treadway, M. T. Anhedonia in depression: biological mechanisms and computational models. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 22, 128–135 (2017).

Hanita, M. Self-Report measures of patient utility: should we trust them? J. Clin. Epidemiol. 53, 469–476 (2000).

LI, D. et al. Application of diffusion tensor imaging in Cns. Int. J. Biomed. Eng. 26, 197–202 (2003).

Goto, M. et al. Advantages of using both Voxel- and Surface-Based morphometry in cortical morphology analysis: A review of various applications. Magn. Reson. Med. Sci. 21, 41–57 (2022).

HUO, L., ZHENG, Z., LI, J. & LI, J. Brain plasticity in the elderly: evidence from cognitive training. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 26, 846–858 (2018).

Nejati, V., Salehinejad, M. A., Nitsche, M. A., Najian, A. & Javadi, A. Transcranial direct current stimulation improves executive dysfunctions in adhd: implications for inhibitory control, interference control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility. J. Atten. Disord. 24, 1928–1943 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant number 82001444]. We are also grateful to all the elderly women who participated in the study, and the heads of relevant community hospitals, who worked closely with our team to ensure the smooth progress of the investigation.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant number 82001444].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the concept and design of the study. Dongmei WU, Xiucheng MA, carried out material preparation, data collection. Song Wang carried out data analysis. Xiucheng MA, wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, X., Wang, S. & Wu, D. Perceived stress mediates the association between orbitofrontal cortex grey matter volume and depressive symptoms in older women. Sci Rep 16, 1473 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31127-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31127-6