Abstract

Extreme climate events are increasingly recognized as important environmental determinants of health. However, their associations with stroke incidence remain unclear, particularly among aging populations in developing countries. We conducted a cross-sectional study to examine the associations between four types of extreme climate events—extreme low temperature (LTD), extreme high temperature (HTD), extreme rainfall (ERD), and extreme drought (EDD)—and stroke among Chinese adults aged over 45 years. Climate data were obtained from the Climate Physical Risk Index (CPRI), developed using NOAA meteorological records, while health and demographic data were drawn from the 2015 wave of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Multivariable logistic regression models were applied to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), adjusting for sociodemographic, behavioral, and clinical covariates. Subgroup analyses were conducted to explore potential effect modifications including sex, residence, education status, marital status, smoking status, drinking frequency, and regional category. Extreme climate events are increasingly recognized as important environmental determinants of health. However, their associations with stroke incidence remain unclear, particularly among aging populations in developing countries. We conducted a cross-sectional study to examine the associations between four types of extreme climate events—extreme low temperature (LTD), extreme high temperature (HTD), extreme rainfall (ERD), and extreme drought (EDD)—and stroke among Chinese adults aged over 45 years. Climate data were obtained from the Climate Physical Risk Index (CPRI), developed using NOAA meteorological records, while health and demographic data were drawn from the 2015 wave of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Multivariable logistic regression models were applied to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), adjusting for sociodemographic, behavioral, and clinical covariates. Subgroup analyses were conducted to explore potential effect modifications including sex, residence, education status, marital status, smoking status, drinking frequency, and regional category. LTD was significantly associated with a lower incidence of stroke in all models (fully adjusted OR = 0.98, 95% CI: 0.95–1.00, p = 0.007). In contrast, EDD was associated with a higher incidence of stroke in the fully adjusted model (OR = 1.02, 95% CI: 1.00–1.04, p = 0.035). No significant associations were found for HTD or ERD in the overall analysis. Subgroup analyses revealed stronger associations of LTD and EDD with stroke among females, non-smokers, non-drinkers, and residents in specific regions. Our findings suggest a potentially protective role of extreme low temperatures and a modest adverse effect of extreme drought on stroke incidence among middle-aged and older adults in China. These associations vary across population subgroups and underscore the nEDD for climate-adaptive public health strategies tailored to vulnerable populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stroke is a major global health concern and remains one of the leading causes of death and long-term disability worldwide1,2. According to the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study 2019, stroke is responsible for approximately 12 million deaths and over 143 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) annually, with a disproportionate impact in low- and middle-income countries3,4. Among these, China bears the heaviest stroke burden in the world, accounting for nearly one-third of global stroke-related deaths5. The prevalence of stroke among Chinese adults aged 40 years and above has significantly increased, and stroke has become the top cause of death and disability-adjusted life years lost in the country6,7. The rapid demographic transition, characterized by population aging and urbanization, further exacerbates the growing stroke burden.

The etiology of stroke is multifactorial, involving a wide range of both non-modifiable and modifiable risk factors8. Non-modifiable factors include advanced age, male sex, family history of stroke, and certain genetic predispositions. Modifiable risk factors, however, account for the majority of stroke events and represent critical targets for prevention. These include hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, atrial fibrillation, obesity, physical inactivity, smoking, unhealthy diet, and excessive alcohol consumption. Moreover, metabolic indicators such as elevated fasting blood glucose, high triglyceride levels, and increased waist circumference have also been independently associated with higher stroke risk9,10,11. In addition to these well-established individual-level risk factors, there is growing recognition of the role of environmental and contextual exposures in shaping cerebrovascular health outcomes.

Recent research has highlighted the potential influence of environmental factors such as air pollution and climate variability on stroke risk12,13,14. Among these, extreme weather events driven by climate change, including fluctuations in temperature and precipitation, have increasingly emerged as potential triggers or modifiers of stroke risk15,16,17. However, the evidence remains inconsistent, and the mechanisms underlying these associations are not fully understood. Investigating the relationship between extreme climate events and stroke, particularly in vulnerable populations such as middle-aged and older adults with reduced physiological resilience, is essential to better understand the impact of environmental stressors on stroke risk.

Extreme climate events—including extreme temperatures, prolonged droughts, heavy rainfall, and sudden weather fluctuations—are becoming more frequent and intense due to accelerating climate change. These events pose significant threats to public health, both directly and indirectly, and have been associated with increased morbidity and mortality from a wide range of diseases18,19,20. For example, extreme heat has been linked to elevated risks of cardiovascular diseases, heatstroke, kidney failure, and respiratory illnesses, particularly among older adults and individuals with pre-existing health conditions20. Conversely, extreme cold can exacerbate conditions such as hypertension, increase blood viscosity, and induce vasoconstriction, thereby elevating the risk of adverse cardiovascular events21. In addition to temperature-related exposures, extreme rainfall and droughts can disrupt food systems, increase the prevalence of waterborne and vector-borne diseases, and impair access to healthcare services22,23. These disruptions can disproportionately affect vulnerable populations, such as the elderly, rural residents, and individuals with limited socioeconomic resources. Furthermore, extreme weather conditions may influence health not only through physiological mechanisms but also via behavioral and psychosocial pathways, including reduced physical activity, poor mental health, and increased social isolation.

Given the growing concern about climate-related health impacts and the limited evidence on the relationship between extreme climate events and stroke, especially in middle-aged and older populations, there is an urgent need for population-based research to clarify these associations. Few studies have examined these relationships in large, nationally representative samples of aging individuals in developing countries, as well as potential variations by sociodemographic and lifestyle factors, where the burden of stroke is rapidly increasing and climate vulnerabilities are pronounced.

To address this gap, the present study aimed to investigate the associations between four major types of extreme climate events—extreme low temperature (LTD), extreme high temperature (HTD), extreme rainfall (ERD), and extreme drought (EDD)—and the incidence of stroke among Chinese adults aged over 45 years. We used data from the 2015 wave of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), a nationally representative survey of middle-aged and older adults, and linked it with meteorological data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). This study provides new evidence on the long-term health impacts of extreme climate events and may offer insights into targeted prevention strategies under the ongoing global climate crisis.

Methods

Definition of exposure

Data on extreme climate events, including LTD, HTD, ERD, and EDD, were derived from the Climate Physical Risk Index (CPRI) dataset, which was developed using daily meteorological observations from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. This dataset provides high-resolution, station-level climate risk indicators for multiple regions, including subnational areas in China, covering the period from 1993 to 2023.To identify extreme events, historical daily data from 1973 to 1992 were used to establish percentile-based thresholds for each climate variable: the 10th and 90th percentiles of temperature for LTD and HTD, the 95th percentile of precipitation for ERD, and the 5th percentile of humidity for EDD. Each extreme indicator was computed as the annual number of days in which observed values excEDDed these thresholds at each meteorological station. The values were then aggregated at the regional level using the arithmetic mean across stations. Finally, the indicators were standardized using a min-max normalization approach to ensure comparability across regions and years.

Definition of exposure

Individual-level data on stroke outcomes and covariates were obtained from the 2015 wave (Wave 3) of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, a nationally representative survey of Chinese residents aged 45 years and older. The primary outcome variable was self-reported history of physician-diagnosed stroke, defined by the response to the question “Have you ever been diagnosed with a stroke by a doctor?” Participants who answered “Yes” were coded as having experienced a stroke, while others were coded as non-stroke.

Definition of covariates

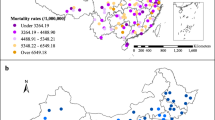

A range of demographic, socioeconomic, behavioral, and clinical covariates were included. Demographic variables comprised age, sex, and place of residence (urban or rural). Socioeconomic indicators included education level (categorized as “elementary school or below” and “middle school or above”) and marital status (categorized as “married and living with a spouse,” “married but not living with a spouse,” and “single, divorced, or widowed”). Behavioral factors included smoking status (ever smoked vs. never) and drinking frequency (categorized as non-drinker, drinks less than once a month, and drinks more than once a month). Clinical covariates included body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, fasting blood glucose, triglyceride level, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and C-reactive protein (CRP). To account for geographical differences, each participant was also assigned to one of three regional categories (East, Midland, or West) based on their province of residence (Fig. 1).

All variable transformations and categorizations followed established CHARLS documentation standards and were implemented using R. Participants younger than 45 years were excluded from the analytic sample to maintain population comparability with stroke incidence profiles in mid-to-late adulthood.

Statistical analysis

We employed multivariable logistic regression models to evaluate the associations between various types of extreme climate events and the incidence of stroke. The exposure variables included extreme low temperature, extreme high temperature, extreme rainfall, and extreme drought.

For each exposure, we fitted three generalized linear models with a binomial family and logit link. The first model included the exposure variable only, without adjustment for any covariates. The second model adjusted for a basic set of sociodemographic variables (Model 1), including age, sex, body mass index, place of residence, education level, and marital status. The third model (Model 2) additionally adjusted for behavioral and clinical covariates, including smoking status, drinking frequency, geographic region, waist circumference, triglyceride levels, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, fasting blood glucose, C-reactive protein, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure.

Given the hierarchical nature of the data, where participants within provinces may share the same climate exposure values, we extended our analysis by incorporating a generalized linear mixed-effects model (GLMM). In this approach, province was treated as a random effect to account for the non-independence of participants within the same geographical region. This adjustment was crucial for addressing potential correlations between individuals from the same province. Random intercepts for each province were included to capture the variability in stroke risk associated with unmeasured province-level factors, such as regional climate and health infrastructure, which might influence the associations between extreme climate exposures and stroke risk.

To assess the robustness of our results, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to examine the impact of missing covariates on the observed associations between extreme climate exposures and stroke risk. Missing data for covariates were handled using multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE), which generates several imputed datasets to account for uncertainty in missing values. This approach assumes that the missing data are missing at random (MAR) and provides more reliable estimates compared to complete case analysis. We imputed missing covariates in the models for each exposure-outcome relationship and performed the same set of analyses on the imputed datasets. The imputed datasets were combined using Rubin’s rules to produce pooled estimates of the associations and their respective confidence intervals. By comparing results from imputed datasets with the original complete case analysis, we assessed whether missing data influenced the robustness of our findings.

Prior to model fitting, variables with no variability in the analysis dataset were automatically excluded to prevent model convergence issues. Odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by exponentiating the estimated regression coefficients. P-values were derived to assess the statistical significance of associations. All models were fitted on participants aged over 45 years. Robustness of results was checked by comparing models with different covariate sets.

Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided p-value < 0.05 after adjustment for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) procedure.

Subgroup analysis

To assess potential effect modification and heterogeneity in the associations between extreme climate exposures and stroke incidence, we conducted subgroup analyses stratified by key demographic, socioeconomic, and behavioral variables. The stratification variables included sex, residence, education status, marital status, smoking status, drinking frequency, and regional category.

For each subgroup, we re-estimated the associations between extreme climate events and stroke using logistic regression models within the respective strata. As in the main analysis, three models were specified for each exposure-outcome relationship: (1) a crude model with no covariates; (2) a model adjusted for core sociodemographic factors (Model 1), excluding the stratification variable to avoid redundancy; and (3) a fully adjusted model (Model 2) that additionally included behavioral and clinical covariates, also excluding the stratification variable. Covariates with no variation within a given subgroup were automatically removed from the model to ensure stability and avoid convergence issues.

All subgroup-specific models were fitted independently, and ORs with 95% CIs were computed for each exposure variable within each stratum. To account for multiple comparisons in the subgroup analysis, we applied the Benjamini-Hochberg correction to control the false discovery rate (FDR). This adjustment helps to reduce the likelihood of Type I errors and ensures the robustness of the findings. This analysis allowed us to explore whether the relationship between extreme climate exposures and stroke differed by individual-level or regional characteristics, potentially highlighting vulnerable populations.

Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided p-value < 0.05 after adjustment for multiple comparisons using the BH procedure.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 8,396 participants aged over 45 years were included in the analysis, of whom 330 (3.9%) reported a history of physician-diagnosed stroke (Table 1). Compared with non-stroke participants, those with stroke were generally older and more likely to be male, have lower educational attainment, and be ever-smokers. They also exhibited higher prevalence of non-drinking status. Clinically, stroke participants had elevated waist circumference, fasting blood glucose, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and C-reactive protein, along with lower levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. In terms of climate exposures, the number of extreme low temperature days was significantly lower among individuals with stroke.

Association between extreme climate events and stroke

We assessed the associations between four types of extreme climate events and the incidence of stroke using logistic regression models with increasing levels of covariate adjustment (Table S1 and Fig. 2). Exposure to LTD was associated with a reduced incidence of stroke in the unadjusted and partially adjusted models. In the unadjusted model, each unit increase in LTD was significantly associated with lower odds of stroke (OR = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.95–0.99, p = 0.006). This inverse association remained significant after adjusting for basic demographic covariates (Model 1: OR = 0.96, 95% CI: 0.94–0.99, p = 0.002). However, in the fully adjusted model including behavioral and clinical covariates (Model 2), the association was attenuated and no longer statistically significant (OR = 0.98, 95% CI: 0.95–1.00, p = 0.072). No statistically significant associations were observed between HTD and stroke in any of the models. In the fully adjusted model, HTD was marginally associated with increased stroke incidence, but the association did not reach statistical significance (OR = 1.01, 95% CI: 1.00–1.02, p = 0.083). Similarly, ERD were not significantly associated with stroke incidence in any model. All estimated odds ratios were close to null, and p-values remained well above 0.05 in unadjusted and adjusted models. For EDD, we observed a statistically significant positive association with stroke only in the fully adjusted model (Model 2: OR = 1.02, 95% CI: 1.00–1.04, p = 0.035), suggesting a possible increased incidence with higher frequency of drought days. However, this association was not evident in the unadjusted or partially adjusted models (p > 0.05).

The robustness of the results was checked by comparing models with different covariate sets (Model 1, 2, and 3). The results of the GLMM analysis are presented in Table S2, where the odds ratios for LTD, HTD, ERD, and EED were estimated for each model. Importantly, the inclusion of province as a random effect did not alter the significance of the associations but provided a more accurate estimate of the uncertainty in the odds ratios. For LTD, the ORs remained consistent across the models, showing a significant inverse association with stroke risk, while for HTD and ERD, the results were more variable and less consistent across the models. EED showed a significant positive association with stroke in the fully adjusted model (Model 3), highlighting the potential impact of extreme climate events on stroke risk, particularly in vulnerable populations. The sensitivity analysis confirmed that the results were consistent across both imputed and non-imputed datasets, suggesting that the impact of missing covariates on the final conclusions is minimal (Table S3).

These findings indicate a potentially protective role of exposure to extreme low temperatures and suggest a modest association between extreme drought and increased stroke incidence after controlling for comprehensive covariates.

Subgroup analysis

Stratified analyses were conducted to explore potential effect modification of the associations between extreme climate exposures and stroke across demographic, behavioral, and regional subgroups (Figure S1). Notably, the protective association between LTD and stroke remained statistically significant in multiple subgroups.

Among females, higher LTD was consistently associated with lower stroke incidence across all models, including the fully adjusted model (OR = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.92–0.99, p = 0.012). Similarly, significant inverse associations were observed in both rural and urban residents, participants with elementary education or below, and those with middle school or above. The protective effect of LTD was also significant among single/divorced/widowed individuals, non-smokers, non-drinkers, and participants living in the East and Midland regions of China. In contrast, HTD showed a positive association with stroke incidence in certain subgroups. Specifically, among urban residents and married individuals living with a spouse, higher HTD was associated with increased stroke incidence in the fully adjusted model (urban: OR = 1.02, 95% CI: 1.00–1.03, p = 0.024; married: OR = 1.01, 95% CI: 1.00–1.02, p = 0.015). For EDD, positive associations with stroke were found predominantly in females, married individuals, non-smokers, non-drinkers, and those residing in the Midland region. These associations remained significant in both partially and fully adjusted models. For example, among non-drinkers, EDD was significantly associated with stroke in the fully adjusted model (OR = 1.03, 95% CI: 1.01–1.05, p = 0.015). No statistically significant subgroup-specific associations were identified for ERD.

These findings suggest that the effects of certain climate exposures on stroke incidence may vary by individual characteristics, particularly sex, lifestyle behaviors, and geographic region, highlighting the importance of considering population heterogeneity when assessing environmental health risks.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study based on a nationally representative sample of middle-aged and older adults in China, we investigated the associations between multiple types of extreme climate events and the incidence of stroke. By integrating meteorological data from the Climate Physical Risk Index (CPRI) and individual-level health data from the 2015 wave of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, we comprehensively assessed the impact of four major extreme climate exposures—LTD, HTD, ERD, and EDD—on stroke prevalence. Our main analysis revealed that LTD was significantly associated with a lower incidence of stroke, even after adjusting for a wide range of demographic, behavioral, and clinical covariates. In contrast, EDD showed a modest positive association with stroke in fully adjusted models, while HTD and ERD were not significantly associated with stroke in the overall sample. Subgroup analyses further demonstrated that the protective association of LTD and the adverse effect of EDD were more pronounced in specific population subgroups, such as females, non-smokers, non-drinkers, and residents in the East and Midland regions. These findings suggest that the health impacts of extreme climate events on cerebrovascular outcomes may vary across population characteristics and emphasize the nEDD to consider individual-level vulnerability in climate-related health research.

Several plausible biological and behavioral mechanisms may explain the observed associations between extreme climate events and stroke. The protective effect of extreme low temperatures observed in our study may reflect behavioral adaptations in colder regions, such as increased indoor time, use of protective clothing, or heating infrastructure that mitigates cold-related physiological stress24,25,26. Additionally, populations in regions with more frequent low-temperature days may develop greater resilience or acclimatization, both physiologically and behaviorally27,28. It is also possible that areas with higher LTD are generally located in less urbanized, lower-pollution environments, indirectly contributing to a reduced stroke burden.

The association between extreme drought and increased stroke incidence may operate through multiple pathways. Drought conditions can exacerbate air pollution (e.g., particulate matter from dry soil and wildfires), impair access to clean water and sanitation, and increase the risk of food insecurity and malnutrition—all of which are known risk factors for cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Moreover, the psychological stress and socioeconomic instability associated with prolonged drought may influence stroke incidence via neuroendocrine pathways and poor health behaviors (e.g., reduced medication adherence or increased sedentary behavior). These mechanisms may disproportionately affect individuals with fewer resources or coping strategies, as suggested by our subgroup findings.

Subgroup analyses revealed heterogeneous associations between climate exposures and stroke incidence. The inverse association between LTD and stroke remained significant in females, non-smokers, non-drinkers, and individuals living in the East and Midland regions, suggesting that individual characteristics and contextual factors may influence vulnerability to climate stressors. In contrast, HTD was positively associated with stroke incidence among urban residents and married individuals, while EDD showed stronger effects in females, non-drinkers, and residents in the Midland region. These patterns may reflect differences in exposure, physiological sensitivity, or behavioral and environmental adaptations. The findings highlight the need for stratified public health strategies that account for population-specific risk profiles under climate change.

Our study underscores the growing importance of incorporating climate-related environmental exposures into cerebrovascular disease prevention strategies. The identification of extreme low temperature as a potential protective factor and extreme drought as a possible risk factor for stroke highlights the nuanced and context-specific nature of climate-health interactions. These findings suggest that public health policies should not adopt a one-size-fits-all approach to climate adaptation, but rather consider regional climate patterns, infrastructure resilience, and population-specific vulnerabilities. For example, improving early warning systems, maintaining access to healthcare during environmental stress events, and ensuring equitable distribution of climate adaptation resources may help mitigate the health impacts of future climate extremes. Furthermore, public awareness campaigns and community-based interventions could target high-risk populations—such as older adults, women, or those living in drought-prone regions—with tailored guidance during extreme weather periods.

The generalizability of our findings is primarily limited to middle-aged and older adults in China, and caution is warranted in extrapolating these associations to younger populations or to other countries with different climatic, socioeconomic, and healthcare conditions. Nonetheless, our use of a large, nationally representative sample strengthens the internal validity of the findings and provides important insights for countries undergoing similar demographic and environmental transitions. Although the observed effect sizes may appear modest, they are statistically significant and potentially meaningful at the population level, particularly given the high prevalence of both stroke and climate stressors in aging societies. Even small shifts in stroke risk associated with environmental exposures may translate into substantial public health impacts when applied across millions of individuals. These findings highlight the nEDD for climate-adaptive health policies, such as early warning systems, targeted resource allocation during extreme weather periods, and regional health planning that considers environmental vulnerability.

While we acknowledge that the observed ORs are modest, it is important to reconsider whether these values reflect clinically significant risk differences. Specifically, odds ratios close to 1.0, such as those observed for extreme HTD and ERD, suggest a weak association with stroke risk that may not translate into meaningful clinical impacts. Even though statistically significant associations were found, the effect sizes do not indicate substantial differences in stroke risk at the individual level. Thus, while our findings may be relevant for understanding broader trends in climate-related health risks, they may not warrant immediate public health interventions without further validation of their clinical significance. It is crucial to recognize that modest associations in epidemiological studies do not always equate to actionable changes in clinical practice, and future studies should focus on confirming these results in longitudinal or intervention-based settings before drawing conclusions about their clinical relevance.

Several limitations should be noted when interpreting our findings. First, the cross-sectional design of this study limits the ability to infer causality between climate exposures and stroke events. The temporal relationship between exposure and outcome cannot be definitively established, and reverse causation cannot be ruled out. Second, stroke status was based on self-reported physician diagnosis, which may introduce recall or reporting bias, although previous validation studies suggest acceptable reliability of such measures in large-scale surveys. The stroke outcome was based solely on self-reported physician diagnosis, without further clinical validation, information on stroke subtypes, severity, or timing. This may introduce misclassification bias. However, this approach has been widely used in epidemiological studies and is considered reliable in large population-based surveys. Nonetheless, the lack of detailed stroke characterization may limit the precision of our findings and warrants cautious interpretation. Third, while we adjusted for a wide range of potential confounders, residual confounding from unmeasured factors—such as dietary patterns, air pollution, physical activity, or genetic predisposition—remains possible. Additionally, the climate exposure data were aggregated at the regional level and may not fully capture individual-level exposures or intra-regional variability in environmental conditions and adaptive capacity. Although the CHARLS dataset is nationally representative, the findings may not be generalizable to younger populations or other countries with different climate and health system profiles. Finally, several potentially important confounders could not be accounted for in this study due to data limitations. These include regional air pollution levels, healthcare access and quality, community-level socioeconomic conditions, and population migration. The absence of these variables may introduce unmeasured confounding, which could bias the observed associations between extreme climate events and stroke incidence. Future studies integrating multi-source data, including environmental monitoring and health system indicators, are nEDDed to better isolate the independent effects of climate exposures on cerebrovascular outcomes.

Additionally, while we acknowledge the limitations associated with self-reported stroke diagnoses, it is important to note that differential misclassification across regions may further complicate the interpretation of our findings. Specifically, stroke reporting patterns could vary systematically across provinces due to differences in climate exposures, healthcare access, or socioeconomic characteristics. For instance, regions with better healthcare infrastructure may have higher rates of stroke diagnosis or more accurate reporting, whereas regions with limited access to healthcare might have lower reporting rates or delays in diagnosis. These regional variations in stroke reporting could lead to differential misclassification and introduce bias in the observed associations between climate exposures and stroke risk. Future studies should explore these potential regional differences and account for them in order to better understand how climate exposures interact with local healthcare systems and socioeconomic conditions to influence stroke incidence.

Moreover, the inverse association observed between extreme low temperature and stroke risk should be interpreted with caution, as it may reflect residual confounding rather than a true protective effect. While we previously mentioned potential behavioral or infrastructural adaptations to cold environments, it is important to emphasize that this finding contradicts much of the existing evidence on cold-induced cardiovascular stress and its detrimental effects. Given the biological implausibility of a protective effect from extreme cold, this result is likely a methodological artifact. We acknowledge that the observed association warrants further critical investigation, and additional studies are needed to explore alternative explanations and properly disentangle the effects of temperature from other confounding environmental and socioeconomic factors.

Furthermore, while we have identified potential unmeasured confounders such as air pollution levels, healthcare access, community-level socioeconomic conditions, and population migration, it is important to consider how these factors might specifically bias the observed associations. For instance, air pollution may exacerbate the effects of extreme climate events on stroke risk, particularly in regions with high pollution levels, potentially inflating the observed association between climate exposures and stroke outcomes. Conversely, better healthcare access could lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment of stroke, possibly reducing the observed stroke risk in regions with more robust healthcare systems, thereby underestimating the true impact of extreme climate events. Additionally, socioeconomic disparities could also create spurious associations, where individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds may be more vulnerable to both climate-related stressors and poor health outcomes, leading to an overestimation of the effect of climate exposures on stroke incidence. These factors could confound the relationship between extreme climate events and stroke risk, either strengthening or weakening the observed associations, and must be considered in future research to more accurately isolate the effects of climate exposures.

In conclusion, this study provides new evidence on the associations between extreme climate events and stroke incidence among middle-aged and older adults in China. Our results suggest that exposure to extreme low temperatures may be inversely associated with stroke incidence, while extreme drought may contribute to increased vulnerability, particularly in specific population subgroups. These findings highlight the complex interplay between environmental conditions and cerebrovascular health and emphasize the nEDD for regionally tailored, climate-sensitive public health strategies. Future research should aim to validate these findings using longitudinal study designs and more precise exposure measurements, including personal-level environmental monitoring. Investigating potential mediating mechanisms—such as inflammation, vascular function, or behavioral adaptation—could further elucidate causal pathways. Moreover, exploring interactions between climate exposures and other environmental or social determinants (e.g., air quality, socioeconomic status) may help identify high-risk populations and inform more targeted prevention and adaptation strategies in the context of a changing climate.

Data availability

The CHARLS data used in this work are publicly available; they are unrestricted use data that any researcher can obtain from the CHARLS website. Data can be accessed via http://opendata.pku.edu.cn/dataverse/CHARLS.

References

Feigin, V. L., Norrving, B. & Mensah, G. A. Global burden of stroke. Circ. Res. 120 (3), 439–448. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308413 (2017).

Schlogl, M., Quinn, T. J. & International Stroke, R. Rehabilitation alliance frailty stroke G. Pragmatic solutions for the global burden of stroke. Lancet Neurol. 23 (4), 333–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(24)00040-1 (2024).

He, Q. et al. Global, Regional, and National burden of Stroke, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for global burden of disease 2021. Stroke 55 (12), 2815–2824. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.124.048033 (2024).

Collaborators, G. B. D. S. Global, regional, and National burden of stroke, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 18 (5), 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30034-1 (2019).

Tu, W. J. et al. Estimated burden of stroke in China in 2020. JAMA Netw. Open. 6 (3), e231455. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.1455 (2023).

Ning, X. et al. Increased stroke burdens among the Low-Income young and middle aged in rural China. Stroke 48 (1), 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.014897 (2017).

Li, Z., Jiang, Y., Li, H., Xian, Y. & Wang, Y. China’s response to the rising stroke burden. BMJ 364, l879. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l879 (2019).

Debette, S. & Markus, H. S. Stroke genetics: Discovery, insight into Mechanisms, and clinical perspectives. Circ. Res. 130 (8), 1095–1111. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.122.319950 (2022).

Shi, H. et al. Fasting blood glucose and risk of stroke: A Dose-Response meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 40 (5), 3296–3304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2020.10.054 (2021).

Kim, J. Y. et al. Abstract TP184: impact on ischemic stroke subtypes of fasting and Non-fasting triglycerides. Stroke 48 (suppl_1). https://doi.org/10.1161/str.48.suppl_1.tp184 (2017).

Cho, J. H. et al. The risk of myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke according to waist circumference in 21,749,261 Korean adults: A nationwide Population-Based study. Diabetes Metab. J. 43 (2), 206–221. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2018.0039 (2019).

Wang, Z., Li, G., Huang, J., Wang, Z. & Pan, X. Impact of air pollution waves on the burden of stroke in a megacity in China. Atmos. Environ. 202, 142–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2019.01.031 (2019).

Timsit, S., Nowak, E., Grimaud, O. & Padilla, C. Neighborhood disparities in stroke and socioeconomic, urban-rural factors using stroke registry. Eur. J. Pub. Health. 29 (Supplement_4). https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz187.132 (2019).

Ranta, A. et al. Climate change and stroke: A topical narrative review. Stroke 55 (4), 1118–1128. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.123.043826 (2024).

Cottle, R. M., Fisher, K. G., Wolf, S. T. & Kenney, W. L. Onset of cardiovascular drift during progressive heat stress in young adults (PSU HEAT project). J. Appl. Physiol. (1985). 135 (2), 292–299. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00222.2023 (2023).

Wu, Y. et al. Exposure to high-temperature and high-humidity environments associated with cardiovascular mortality. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 290, 117746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2025.117746 (2025).

Zheng, C. et al. Relationship of ambient humidity with cardiovascular diseases: A prospective study of 24,510 adults in a general population. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 37 (12), 1352–1361. https://doi.org/10.3967/bes2024.156 (2024).

Burbank, A. J., Espaillat, A. E. & Hernandez, M. L. Community- and neighborhood-level disparities in extreme climate exposure: implications for asthma and atopic disease outcomes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 152 (5), 1084–1086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2023.09.015 (2023).

Alcayna, T. et al. Climate-sensitive disease outbreaks in the aftermath of extreme Climatic events: A scoping review. One Earth. 5 (4), 336–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2022.03.011 (2022).

Khraishah, H. et al. Climate change and cardiovascular disease: implications for global health. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 19 (12), 798–812. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-022-00720-x (2022).

Du, J. et al. Extreme cold weather and circulatory diseases of older adults: A time-stratified case-crossover study in jinan, China. Environ. Res. 214 (Pt 3), 114073. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.114073 (2022).

Meisner, A. & de Boer, W. Strategies to maintain natural biocontrol of Soil-Borne crop diseases during severe drought and rainfall events. Front. Microbiol. 9, 2279. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.02279 (2018).

Benitez-Cano, D., Gonzalez-Marin, P., Gomez-Gutierrez, A., Mari-Dell’Olmo, M. & Oliveras, L. Association of drought conditions and heavy rainfalls with the quality of drinking water in Barcelona (2010–2022). J. Expo Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 34 (1), 175–183. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-023-00611-4 (2024).

Hanna, E. G. & Tait, P. W. Limitations to thermoregulation and acclimatization challenge human adaptation to global warming. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 12 (7), 8034–8074. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120708034 (2015).

Castellani, J. W. & Young, A. J. Human physiological responses to cold exposure: acute responses and acclimatization to prolonged exposure. Auton. Neurosci. 196, 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2016.02.009 (2016).

Price, E. R., Brun, A., Caviedes-Vidal, E. & Karasov, W. H. Digestive adaptations of aerial lifestyles. Physiol. (Bethesda). 30 (1), 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1152/physiol.00020.2014 (2015).

Gasparrini, A. et al. Mortality risk attributable to high and low ambient temperature: a multicountry observational study. Lancet 386 (9991), 369–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62114-0 (2015).

Wang, X. et al. Ambient temperature and stroke occurrence: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 13 (7). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13070698 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study team for providing data and training in using the datasets. We thank the students who participated in the survey for their cooperation. We thank all volunteers and staff involved in this research. The authors certify that they comply with the ethical guidelines for authorship and publishing of BMC Geriatrics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors solely contributed to this paper; X.J, W.C wrote this manuscript; X.J, S.C analyzed the data; S.C, W.C, P.R acquisition of data; J.J designed this study and reviewed this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Medical Ethics Board Committee of Peking University granted the study an exemption from review.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, X., Chen, S., Chen, W. et al. Cross sectional analysis of the association between extreme climate events and stroke incidence in middle aged and older Chinese adults. Sci Rep 16, 892 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31151-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31151-6