Abstract

Control charts are widely used in manufacturing and quality management to monitor process variability. Although easy to implement, the Shewhart control chart lacks sensitivity to small process shifts. The exponentially weighted moving average (EWMA) control chart is effective in detecting minor shifts, but responds slowly to sudden changes. To enhance the detection capability, this study adopts the adaptive EWMA (AEWMA) control chart, which features dynamic adjustment mechanisms to improve the monitoring performance. This is applicable for skewed process data, particularly those following a Gamma distribution such as lifetime data, waiting times, and current stability indicators in semiconductor manufacturing. The Wilson-Hilferty transformation was applied to approximate the normality before constructing the AEWMA control chart. Monte Carlo simulations were employed to design and evaluate both the fixed sampling interval (FSI) and variable sampling interval (VSI) schemes under various combinations of shapes, scale parameters, and smoothing constants. To address the limitations of the traditional average run length (ARL) in reflecting the differences in sampling schemes, this study also adopted the average time-to-signal (ATS) as a performance metric. The simulation results demonstrated that the AEWMA VSI chart outperformed both the AEWMA FSI and EWMA charts in terms of sensitivity and stability when detecting small process shifts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Statistical process control (SPC) is a key methodology used to improve product quality and ensure process stability. Among the various SPC tools, control charts are most commonly used because of their effectiveness and simplicity in detecting process shifts. When a process quality characteristic exceeds the control limits, it indicates a potential out-of-control condition due to assignable causes. Prompt corrective action is necessary to maintain consistent quality.

Control charts can generally be classified into two categories based on usage of historical data: memory-less and memory-based. The Shewhart control chart is a typical memoryless chart that relies solely on the current sample data and is thus more suitable for detecting large shifts. In contrast, cumulative sum (CUSUM) and exponentially weighted moving average (EWMA) charts are memory-based because they incorporate both historical and current observations. These charts offer greater sensitivity for small shifts and improve early detection of abnormalities1.

The adaptive exponentially weighted moving average (AEWMA) control chart is an enhanced version of the traditional EWMA control chart. It introduces a dynamically adjustable smoothing constant that responds to process behavior and improves the sensitivity to shifts of various magnitudes. Capizzi and Masarotto2 first proposed the AEWMA control chart, which weights the past observations using a suitable function of the current error. This scheme can be viewed as a smooth combination of a Shewhart chart and an EWMA chart, helping overcome the initial inertia of a standard EWMA chart. Subsequently, Haq et al.3 developed an AEWMA chart that uses an unbiased mean-shift estimator to adaptively adjust the smoothing constant, which the outperformed traditional AEWMA and several CUSUM control charts in simulation studies. Owing to its high flexibility, the AEWMA control chart has been widely applied in various statistical monitoring strategies. Nonparametric AEWMA control charts4,5 are suitable for unknown or skewed distributions, whereas multivariate AEWMA control charts6,7,8 support the simultaneous monitoring of multiple quality characteristics. More recently, machine learning techniques have been used to extend the AEWMA control chart, as demonstrated by Kazmi and Noor-ul-Amin9 and Ahmadini, et al.10.

Control charts are mostly designed under a fixed sampling interval (FSI) scheme, in which samples are collected at predetermined intervals using constant control limits. Although FSI charts are simple and stable, they are less responsive to gradual or abrupt shifts, limiting their detection performance. To address this issue, adaptive control chart schemes that allow dynamic adjustments to sampling policies and control parameters based on historical process information have been proposed. Reynolds et al.11 first introduced the variable sampling interval (VSI) concept, followed by derivative strategies such as variable sample size (VSS), variable sampling interval and size (VSSI), and variable parameter (VP) schemes. The core idea of VSI is to extend the sampling interval when the control statistic is close to the center line (indicating a stable process) and shorten it when the statistic deviates, thereby enhancing sensitivity. Studies have shown that VSI control charts outperform their FSI counterparts, particularly in detecting small shifts. Saccucci et al.12 were the first to integrate EWMA control charts into VSI schemes. Subsequent studies expanded this approach to various monitoring contexts. For example, Leoni et al.13 proposed a control chart that adjusted both the sample size and sampling interval. Tang et al.14 further applied VSI to AEWMA control charts. Since then, the VSI framework has been extended to more complex scenarios, including multivariate processes15, measurement errors16, and nonparametric17, demonstrating its flexibility and adaptability. In terms of performance evaluation, the traditional average run length (ARL) is insufficient to fully reflect the benefits of adaptive sampling. Tagaras18 suggested using the average time-to-signal (ATS) as a more comprehensive metric under varying process conditions.

Most traditional control charts have been developed under the assumption of normally distributed data. However, real-world data often violates this assumption. Applying control charts designed for normality to skewed data may reduce the detection sensitivity, increase the risk of false alarms, and compromise the accuracy and reliability of process monitoring. Several studies have explored the robustness of EWMA control charts in non-normal settings. Maravelakis et al.19 and Liew et al.20 investigated the detection performance of EWMA control charts under skewed conditions, while Nawaz et al.21 and Hamasha et al.22 emphasized the impact of the smoothing constant on performance when monitoring skewed data.

Among various skewed distributions, the Gamma distribution is particularly useful because of its flexibility and mathematical properties. It is widely used to model right-skewed, non-negative data in fields such as risk management, biomedical signal processing, and queuing theory. In SPC, Gamma distributions are often applied to model asymmetric quality characteristics such as product lifetime and service waiting time, and many authors have developed Gamma-based control charts23,24,25,26. These studies consistently indicate that Gamma-based control charts are more effective and useful for monitoring skewed data. However, most of them directly employ a Gamma-distributed random variable as the monitoring statistic.

The existing control chart designs for skewed data can be classified into three categories: (1) constructing statistics based on specific skewed distributions, (2) applying transformations to approximate normality in order to satisfy the classical chart assumptions, and (3) adopting nonparametric approaches to avoid explicit distributional assumptions. Among these approaches, an alternative and informative strategy is to apply a suitable transformation to map skewed data to an approximately normal scale and then construct control charts based on the resulting sample statistics, as in the works of Liu et al.27, Sukparungsee28, Scagliarini et al.29.

The Wilson-Hilferty transformation converts chi-square-distributed variables into approximately normal ones, which is useful because many parametric methods rely on normality. By making the data nearly normal, this transformation improves the robustness of hypothesis tests and simplifies the use and interpretation of standard statistical techniques. In recent years, the Wilson-Hilferty transformation has been increasingly adopted to address skewness in process data30,31,32,33, further highlighting its practical value in statistical process control. Building on this research direction, this study applies the Wilson-Hilferty transformation to Gamma-distributed data and develops an AEWMA control chart to evaluate its monitoring performance under both fixed sampling interval (FSI) and variable sampling interval (VSI) schemes. The aim is to enhance the sensitivity and overall effectiveness of monitoring skewed processes by incorporating variable sampling interval strategies.

The remainder of this paper is organized into six sections as follows: Gamma AEWMA control charts with FSI and VSI are introduced in Section “Gamma AEWMA FSI and VSI charts”. The performance evaluation of the Gamma AEWMA control chart and comparison between the Gamma EWMA and AEWMA control charts are provided in Sections “Performance of Gamma AEWMA FSI and AEWMA VSI charts” and “Comparison between Gamma EWMA and AEWMA control charts”, respectively. A numerical illustrative example is provided in Section “Examples”, and conclusions are presented in Section “Conclusion”.

Gamma AEWMA FSI and VSI charts

Gamma distribution

The Gamma distribution is a continuous probability distribution suitable for modeling positive-valued data. It is characterized by two positive parameters: the shape parameter \(\alpha\) and scale parameter \(\beta\). The shape parameter determines the form of the distribution over time, whereas the scale parameter represents the average time between events. Assuming that a random variable \(X\) follows a Gamma distribution, its probability density function (PDF) and cumulative distribution function (CDF) are expressed as:

and.

The Gamma distribution belongs to the exponential family, with the expected value and variance calculated as \(E(X) = \alpha \beta^{2}\) and \(Var(X) = \alpha \beta^{2}\), respectively. It is widely used in maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) and generalized linear models (GLM). For \(\alpha { = 1}\), the Gamma distribution is reduced to an exponential distribution, which is suitable for modeling the time until the first occurrence of random events such as failures. During \(\alpha { > 1}\), the distribution becomes less skewed and approaches normality, indicating more stable inter-event times. In contrast, when \(\alpha { < 1}\), the distribution exhibits strong right-skewed characteristics.

Gamma AEWMA FSI charts

Capizzi and Masarotto2 and Haq et al.3 improved the EWMA chart through a score function of the current error and an unbiased mean-shift estimator to adaptively adjust the smoothing constant. However, their studies were predominantly developed under the assumption of normal or approximately normal distributions, and there is still a lack of systematic investigation for Gamma processes, which are commonly encountered in practice and often exhibit pronounced right-skewness. Therefore, this study integrates the AEWMA framework with the cube-root transformation proposed by Wilson and Hilferty34 to construct AEWMA FSI and VSI charts for Gamma-distributed data, with the aim of improving the detection performance of EWMA-type charts in skewed processes.

According to the Wilson-Hilferty transformation, applying the cube root to the variable yields:

This transformation converts the skewed Gamma distribution into an approximately normal distribution. The chart is then based on the approximate mean and variance of the transformed data.

According to Sarwar et al.1, a properly transformed Weibull distribution approximates the standard normal distribution. As both the Weibull and Gamma distributions are skewed, this study transforms the Gamma random variable into a normal one prior to standardization. This approach improves the comparability of statistics under different distributional conditions. The standardization is as follows:

In traditional EWMA control charts, the smoothing constant \(\lambda\) plays a critical role in determining the sensitivity to shifts. A large \(\lambda\) enhances the response to large shifts, while a small \(\lambda\) improves sensitivity to small changes. However, a fixed algorithm makes it difficult to maintain consistent detection performance across various shift magnitudes, often resulting in suboptimal outcomes. To address this limitation, Haq et al.3 proposed the Adaptive EWMA (AEWMA) control chart, which introduces a dynamic adjustment mechanism. In this scheme, the EWMA statistics are initially treated as an estimator \(\delta\) of the process shift. Based on the magnitude of this estimated shift, an appropriate smoothing parameter \(0 < \phi \le 1\) is selected and applied to the EWMA statistics. The key idea is to dynamically adjust the smoothing parameter depending on the estimated shift size, rather than keep it fixed to better reflect potential process changes in real time. This approach improves the adaptability of the AEWMA control chart to both small and large shifts, overcoming the limitations of traditional EWMA control charts.

Accordingly, based on Eq. (4), the EWMA statistic is defined as follows:

Let us denote the standardized observed value of the random variable at the i-th time, where \(i = 1,2, \ldots\), and the initial value is set as \(\hat{\delta }_{0}^{*} = 0\). Assuming that the process is in control, \(T_{i} \sim N(0,1)\). When the process shifts out-of-control, \(T_{i} \sim N(\delta ,1)\), where \(\delta \ne 0\) represents the mean shift from the in-control state. Haq et al.3 indicated that under in-control conditions, \(\hat{\delta }_{i}^{*}\) is an unbiased estimator of the process mean. However, under out-of-control conditions, when the smoothing parameter changes lead to process instability, the statistic \(\hat{\delta }_{i}^{*}\) may produce bias when calculating the process mean. To address this issue, Haq et al.3 proposed an adjustment to \(\hat{\delta }_{i}^{*}\) and defined a new statistic \(\hat{\delta }_{i}^{{**}}\) as follows:

It can be shown that the expected value of the adjusted statistic satisfies \(E(\hat{\delta }_{i}^{{**}} ) = {0}\) for an in-control process; whereas for an out-of-control process, \(E(\hat{\delta }_{i}^{{**}} ) = \delta \ne {0}\). This indicates that \(\hat{\delta }_{i}^{**}\) serves as an unbiased estimator of the process mean in both the in-control and out-of-control states. In other words, regardless of the process state, \(\hat{\delta }_{i}^{**}\) provides an unbiased estimate of the process mean. As the magnitude of \(\delta\) is usually unknown in practical applications, Haq et al.3 estimated \(\delta\) using \(\tilde{\delta }\), which is defined as.

Given the estimated value \(\tilde{\delta }_{i}\) at the i-th time, the degree of shift is used to select a corresponding weighting factor to replace the fixed smoothing constant used in traditional EWMA control charts. Through this adaptive mechanism, the control chart adjusts based on the magnitude of the process variation, thereby enhancing the chart’s sensitivity to various levels of process shifts.

Consequently, under the Gamma distribution assumption, the AEWMA FSI chart statistic is denoted as \(W_{i}\), which is designed to track the upward or downward shifts in the process mean. The statistic \(W_{i}\) is defined as:

where the initial values are set to \(W_{0} = 0\) and \(g\left( {\tilde{\delta }_{i} } \right) \in \left( {0,1} \right)\). Following the recommendation of Haq et al.3, the weight function \(g\left( {\tilde{\delta }_{i} } \right)\) is defined as:

The weight \(g\left( {\tilde{\delta }_{i} } \right)\) is treated as a random variable determined by the magnitude of the shift. The function is designed to enable the AEWMA control chart to maintain near-optimal detection capability within a specific range of shifts. When selecting an appropriate \(g\left( {\tilde{\delta }_{i} } \right)\) value based on the estimated shift size, the chart can improve the monitoring performance and sensitivity across a wide range of shift magnitudes. When the statistic \(W_{i}\) exceeds the control limits (\(\pm H\)) of the AEWMA FSI chart, the process is considered out- of-control. Conversely, if \(W_{i}\) remains within the limits, it is deemed to be in-control.

Gamma AEWMA VSI charts

In traditional control chart design, fixed sampling interval (FSI) charts are typically used to monitor process deviations. Reynolds et al.11 first introduced the variable sampling interval (VSI) chart. Studies have shown that adopting a VSI design can significantly improve the ability to detect abnormal fluctuations.

VSI charts are typically constructed using a pair of lower and upper control limits (LCL and UCL, respectively) and a pair of lower and upper warning limits (LWL and UWL, respectively). These boundaries divide the monitoring space into three regions: safe, warning, and out-of-control, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The control limits of VSI AEWMA chart are \(\left( {LCL,UCL} \right) = \pm H\) and the warning limits \(\left( {LWL,UWL} \right) = \pm K\). Denote the long and short sampling intervals by \(h_{1}\) and \(h_{2}\), respectively, with \(0 < h_{2} < h_{1}\).

In the AEWMA VSI chart, the sampling strategy is follows:

-

When \(W_{i} \in \left[ {LWL,UWL} \right]\), the process is regarded as in control, and the next sample is taken after a long sampling interval \(h_{1} > 1\).

-

When \(W_{i} \in \left[ {LCL,LWL} \right) \cup \left( {UWL,UCL} \right]\), the process is still considered in control,, but the next sample is taken after a shorter sampling interval \(h_{2} \in (0,1)\).

-

When \(W_{i} \in \left( { - \infty ,LCL} \right) \cup \left( {UCL,\infty } \right)\), the process is judged to be out of control, and stop the process and eliminate assignable causes.

The average run length (ARL) is a widely used indicator for measuring the performance of FSI charts. However, because the sampling interval varies in VSI charts, ARL is no longer appropriate for performance evaluation. Following Tagaras18, this study adopts the average time-to-signal (ATS) as the primary metric. When comparing FSI and VSI charts, ATS is used as the common basis for performance assessment.

For the FSI scheme, the ATS is the product of the ARL and fixed sampling interval \(h_{FSI}\) expressed as:

Regarding the VSI scheme, the ATS is affected by both the average run-time and the actual sampling interval. Therefore, it can be expressed as

where \(E(h)\) denotes the average sampling interval.

To compare the performances of VSI and FSI charts, it is common to equalize the average run length under the in-control condition, denoted as \(ARL_{0}\) and \(E(h) = 1\), i.e.

where \(\rho_{1}\) and \(\rho_{2}\) represent the proportions of time for which the long sampling interval \(h_{1}\) and short sampling interval \(h_{2}\) are used, respectively. This setup ensures that the control charts under both schemes maintain the same ARL and ATS when the process is in-control, i.e., \(ATS_{FSI}\) = \(ATS_{VSI}\) = \(ARL_{0}\). Under this standard, a smaller out-of-control ATS (denoted as \(ATS_{1}\)) indicates better detection performance of the control chart.

According to Reynolds et al.11, the long and short sampling intervals \(h_{1}\) and \(h_{2}\) are generally selected within the ranges of \(1 \le h_{1} \le 5\) and \(0.1 \le h_{2} \le 1\). Among these,\(h_{2} \ge 0.1\) is considered a practical lower bound because it is generally infeasible to perform two or more samplings within a time unit in real-world applications. Moreover, if the sampling interval is too short, it may cause a high temporal correlation among samples, which violates the assumption of independence commonly required in control chart design.

Performance of Gamma AEWMA FSI and AEWMA VSI charts

This section provides a comparative discussion of the monitoring ability of Gamma AEWMA FSI charts and Gamma AEWMA VSI charts across deviations of varying magnitudes.

Gamma AEWMA FSI charts

To evaluate the performance of the Gamma AEWMA FSI chart under various parameter settings, we assume \(\beta_{{0}} { = 1}\) with the process shift defined as \(\beta_{1} = c \times \beta_{0}\), where \(c \in \left\{ {{0}{\text{.5,0}}{.6,0}{\text{.7,0}}{.8},{0}{\text{.9}},1.1,1.2,{1}{\text{.3,1}}{.4,1}{\text{.5}}} \right\}\) to represent different magnitudes of process shifts. In this study, numerical simulation is used to estimate the ARL values of the AEWMA FSI chart. To achieve the desired \(ARL_{0} \simeq 370\), the control limit \(H\) can be adjusted for each combination of \((\alpha ,\phi )\). Haq et al.3 indicated that the value of \(\phi\) significantly influences the in-control and out-of-control performance, particularly the ARL and SDRL. When \(\phi < 0.1\), although out-of-control ARL (denoted as \(ARL_{1}\)) tends to decrease, SDRL increases notably, indicating a higher variability in detection. Accordingly, a value of \(\phi \ge {0}{\text{.1}}\) is recommended for stability. This study further investigates the effect of \(\phi \in \left\{ {0.1,0.15,0.2} \right\}\) and shape parameters \(\alpha \in \left\{ {1,3,5,10} \right\}\) on the behavior of ARL.

From Table 1 and Fig. 2, when the shape parameter \(\alpha\) is large and \(\phi\) is small, the AEWMA FSI chart becomes more sensitive to detecting upward or downward shifts, as indicated by its relative small \(ARL_{1}\) value. When \(\phi\) is fixed, increasing \(\alpha\) leads to a rapid decrease in \(ARL_{1}\), indicating improved detection sensitivity. For example, for \(\phi = 0.{1}\), \(c = 1.1\), the \(\alpha\) values are 1, 3, 5, and 10, and the corresponding \(ARL_{1}\) values are 166.62, 57.88, 34.64, and 16.10, respectively. A similar trend is also observed for downward shifts (\(c = 0.9\)).

The smoothing parameter \(\phi\) significantly affects the detection sensitivity. For a given value of \(\alpha\), as \(\phi\) increases, \(ARL_{1}\) also increases, resulting in a reduced detection capability. That is, smaller \(\phi\) values yield faster responsiveness to shifts. This study adopts \(\phi { = 0}{\text{.1}}\) to ensure strong detection capability for both upward and downward process shifts. Moreover, the reduction in detection performance is more pronounced for downward shifts, indicating that the AEWMA FSI chart is more sensitive to downward shifts than upward shifts. For example, in Table 1 with \(\alpha = 1\) and \(\phi = 0.15\), the \(ARL_{1}\) for a downward shift of \(c = 0.8\) is 18.67, whereas the ARL for an upward shift of \(c = {1}{\text{.2}}\) is as large as 203.47; that is, the latter is about 11 times larger. This clearly indicates that the AEWMA FSI chart is more sensitive to downward shifts. As shape parameter \(\alpha\) increases and the Gamma distribution becomes closer to normal, the difference in detection performance between downward and upward shifts gradually diminishes, and this trend can be consistently observed across the other combinations of \(\alpha\) and \(\phi\) reported in Table 1.

Gamma AEWMA VSI charts

We also focused on examining the impact of the sampling intervals \(h_{1}\) (long sampling interval) and \(h_{2}\) (short sampling interval) on the detection performance of the Gamma AEWMA VSI chart. With the control limit \(H\) fixed from the AEWMA FSI chart, the warning limit \(K\) is adjusted for each \((\alpha ,h_{1} ,h_{2} )\) combination so that the AEWMA VSI chart achieves the same in-control \(ATS_{0}\) as its FSI counterpart. The process is assumed to have an initial value \(\beta_{0} = 1\), with the process shift defined as \(\beta_{1} = c \times \beta_{0}\), where \(c \in \left\{ {{0}{\text{.5,0}}{.6,0}{\text{.7,0}}{.8},{0}{\text{.9}}} \right.{,1}{\text{.1,1}}{.2,1}{\text{.3,}}\)\(\left. {{1}{\text{.4,1}}{.5}} \right\}\). According to Table 1, with \(\phi = 0.1\) and \(\alpha \in \left\{ {1,3,5,10} \right\}\) fixed, the effects of varying \(h_{1} \in \left\{ {1.25,1.5,1.75,2,2.5,3,4} \right\}\) and \(h_{2} \in \left\{ {0.1,0.2,0.5,0.8} \right\}\) on \(ATS_{1}\) are evaluated, as summarized in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

The effect of \(h_{2}\) on ATS

Table 2 and Fig. 3 show that as the shape parameter \(\alpha\) increases, \(ATS_{1}\) tends to decrease, indicating that the AEWMA VSI chart becomes more sensitive to process changes. When the shift magnitude \(c\) indicates an upward or downward shift, \(ATS_{1}\) also decreases, particularly for downward shifts. This reflects a greater responsiveness to small downward changes.

In addition, the choice of the short sampling interval \(h_{2}\) has a significant effect on \(ATS_{1}\). For example, in Table 2 with \(\alpha = 1\),\(\phi = 0.1\) and a moderate downward shift \(c = 0.{8}\), the \(ATS_{1}\) increases from 13.94 when \(h_{2} = 0.1\) to 16.72 when \(h_{2} = 0.{8}\). A similar pattern is observed for \(\alpha = {3}\), where the corresponding \(ATS_{1}\) values under the same shift condition increase from 5.17 (\(h_{2} = 0.1\)) to 6.33 (\(h_{2} = 0.{8}\)). These examples illustrate that a shorter sampling interval consistently leads to a reduction in \(ATS_{1}\), whereas a longer sampling interval results in larger \(ATS_{1}\) values, making it more difficult to detect process shifts promptly under infrequent sampling.

Consequently, when the prompt detection of slight process shifts is of primary concern, it is recommended to adopt a smaller \(h_{2}\). The short sampling interval \(h_{2} = 0.1\) is recommended because it provides better detection performance, as shown by the lower ATS values across all parameter combinations. Our numerical results also show that processes with a larger shape parameter \(\alpha\)(i.e., less skewness) tend to exhibit better sensitivity. However, in practical applications, it is essential to balance detection sensitivity, sampling cost, and the risk of false alarms or missed detections in order to achieve an overall satisfactory control performance.

The effect of \(h_{1}\) on ATS

From Table 3 and Fig. 4, it is evident that as the shape parameter \(\alpha\) increases, the overall \(ATS_{1}\) shows a clear decreasing trend, indicating that the AEWMA VSI chart is highly sensitive to process changes. This trend is consistent with the results of the AEWMA FSI chart discussed above, further demonstrating that AEWMA control charts improve the detection capability with increasing \(\alpha\), regardless of the sampling strategy.

When \(c\) either shifts upward or downward, \(ATS_{1}\) generally decreases. Moreover, the reduction in \(ATS_{1}\) caused by downward shift is usually greater than that caused by upward shift, suggesting that the AEWMA control chart is more sensitive to detecting downward anomalies. This phenomenon is also consistent with the results presented in Section “The effect of on ATS” for the AEWMA VSI chart.

From Tables 2 and 3, as \(\alpha\) increases, the control limit \(H\) rises slightly while warning limit \(K\) remains nearly stable. Larger \(h_{1}\) or \(h_{{2}}\) values lead to a marked reduction in \(K\). Overall, the simulations indicate that for detecting small shifts, the proposed AEWMA VSI chart performs best with a short sampling interval of \(h_{{2}} = 0.1\) and long sampling intervals \(h_{1}\) of 2.5–4, 2–3, 1.75–2.5, and 1.75–2 for \(\alpha\) = 1, 3, 5, and 10, respectively.

Comparison between Gamma EWMA and AEWMA control charts

In the previous section, we investigated the performance of AEWMA charts under both the FSI and VSI schemes in detecting process shifts. In this section, we further compare the detection abilities of the EWMA FSI and AEWMA FSI charts, as well as the corresponding VSI charts.

FSI scheme

According to Section “Gamma AEWMA FSI charts”, a smaller smoothing parameter \(\phi\) value yields better detection ability for small process shifts. Hence, the AEWMA FSI chart with the smoothing parameter \(\phi { = }0.1\) is compared with the EWMA FSI chart with shape parameters \(\alpha \in \left\{ {1,3,5,10} \right\}\) and smoothing constants \(\lambda \in \left\{ {0.05,0.1,0.2} \right\}\). The ARL and SDRL values are presented in Table 4.

Table 4 shows that for the large-shape parameter \(\alpha\), regardless of the upward or downward shift of the scale parameter \(\beta\), the AEWMA FSI chart always performs better than the EWMA FSI chart, particularly in scenarios involving small shifts. However, for the small-shape parameter \(\alpha\), the EWMA FSI chart has a better ability to detect upward shifts than the AEWMA FSI chart only when \(\lambda = 0.05\). For example, under a specific shift \(c = 1.1\), the \(ARL_{{1}}\) value of the EWMA FSI chart is 145.69, which is less than that of the AEWMA FSI chart (166.62), indicating that the EWMA FSI chart responds more quickly to the shift magnitude. In addition, the proposed AEWMA FSI chart always demonstrates stable and sensitive detection capability under most shift conditions.

VSI scheme

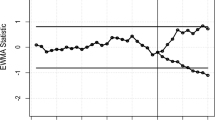

This section considers different settings of the shape parameter \(\alpha\) and scale parameter \(\beta\) with small upward shift \(c = 1.1\) and downward shift \(c = {0}{\text{.9}}\). The goal is to compare the detection capabilities of the EWMA VSI and AEWMA VSI charts under various long sampling intervals \(h_{1}\). Similar to the FSI scheme, the AEWMA VSI chart with smoothing parameter \(\phi { = }0.1\) is also considered for comparison with the EWMA VSI chart with shape parameters \(\alpha \in \left\{ {1,3,5,10} \right\}\) and smoothing constants \(\lambda \in \left\{ {0.05,0.1,0.2} \right\}\). Tables 5 and 6 present the ATS values of the charts with \(h_{{2}} { = 0}{\text{.1}}\), \(c = 0.9\) and \(h_{{2}} { = 0}{\text{.1}}\), \(c = 1.1\), respectively.

Table 5 indicates that regardless of the various shape parameters at small-scale parameter downward shifts, the \(ATS_{1}\) values of both charts decrease gradually as the long sampling interval \(h_{1}\) increases. Moreover, the AEWMA VSI chart always yields a lower \(ATS_{1}\) value, indicating that it outperforms the traditional EWMA VSI chart in detecting small-scale parameter downward shifts.

From Table 6, the \(ATS_{1}\) values of both charts decrease gradually as the long sampling interval \(h_{1}\) increases. This trend is consistent with the downward movement of the scale parameter. For the large shape parameter \(\alpha\), the AEWMA VSI chart always yields a lower \(ATS_{1}\) in detecting small scale parameter upward shifts, indicating superior detection capability compared to the traditional EWMA VSI chart. However, for the small shape parameter \(\alpha\), the EWMA VSI chart with \(h_{1} \le 1.5\) has a better ability to detect upward shift than the AEWMA VSI chart only for \(\lambda = 0.05\).

Examples

This section provides two examples to illustrate the detection capabilities of the AEWMA FSI and AEWMA VSI charts. One is for the downward-scale parameter shift at \(c = {0}{\text{.9}}\) and the other is for the upward-scale parameter shift at \(c = {1}{\text{.1}}\). To ensure a fair comparison, both charts adopt the same parameter settings: the shape parameter \(\alpha = 5\) and smoothing parameter \(\phi = 0.1\). For the AEWMA FSI chart, the fixed sampling intervals are set as \(h_{1} = h_{2} = 1\), while for the AEWMA VSI chart, the short and long sampling intervals are set as \(h_{2} = 0.1\) and \(h_{1} = 1.25\), respectively. The control limits are determined from Tables 1 and 2 with the control limit \(\pm H = 0.711\) and warning limit \(\pm K = 0.374\) to determine whether the process remains under control.

In the simulation, 50 random observations were generated from the Gamma distribution. These values \(X\) were then transformed using the Wilson-Hilferty transformation into approximately normal variables \(Y\) and further standardized to obtain normalized values \(T\). According to Eq. (5), the EWMA statistic \(\hat{\delta }^{*}\) was calculated and adjusted using Eq. (6) to obtain \(\hat{\delta }_{i}^{**}\). Accordingly, we calculated the estimated shift \(\tilde{\delta }_{i}\), which reflects the degree of deviation. Next, Eq. (9) was used to compute the weighting function \(g\left( {\tilde{\delta }_{i} } \right)\), and finally the AEWMA statistic \(W_{i}\) was computed to determine whether the statistic was within the control limits. Tables 7 and 8 list all random variables and plotting statistics. Moreover, the variable \(h\) represents the sampling time at each point, and \(h_{FSI}\), \(h_{VSI}\) are the cumulative sampling times used to determine the out-of-control signals for the AEWMA FSI and AEWMA VSI charts, respectively. They are also presented in the last three columns of Tables 7 and 8. If the AEWMA statistic is within the control limits, the process is in an in-control state; otherwise, the process is in an out-of-control state and appropriate actions must be taken.

For the downward shift example, Fig. 5 presents the histogram and normal probability plot of \(Y\), generated using Minitab. The histogram shows a reasonably symmetric, bell-shaped distribution, and the points in the normal probability plot lie approximately along a straight line, indicating no obvious departures from normality. Moreover, the p-value of 0.106 exceeds the significance level of 0.05, thus, there is no statistical evidence that the transformed data deviate from a normal distribution.

Minitab histogram and normal probability plot for data \(Y\) in Table 7.

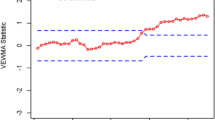

The AEWMA FSI and AEWMA VSI charts are shown in Fig. 6 and the results are listed in Table 7. Both the AEWMA FSI and AEWMA VSI charts signal an out-of-control condition when the statistic \(W{ = }0.765\) exceeds the upper control limit \(H = 0.711\). Although both charts detect the process shift, there is a significant difference in \(ATS_{1}\). Specifically, the AEWMA FSI chart needs 32 time units to detect the shift, while the AEWMA VSI chart triggers a signal at 19.3 time unit. This result is consistent with Tables 1 and 2, where the average \(ATS_{1}\) obtained from 50,000 simulations is 18.65 for the AEWMA FSI chart and only 13.61 for the AEWMA VSI chart.

The Gamma AEWMA FSI and AEWMA VSI charts corresponding to the data in Table 7 for downward shift \(c = 0.9\).

For the upward shift example, similar to Fig. 5, the histogram of the transformed data in Fig. 7 exhibits a bell-shaped distribution, and the points in the normal probability plot fall closely along the reference line. In addition, the p-value of 0.938 exceeds the significance level of 0.05. Consequently, the transformed data appear to satisfy the assumption of normality.

Minitab histogram and normal probability plot for data \(Y\) in Table 8.

The AEWMA FSI and AEWMA VSI chart results are provided in Table 8 and shown in Fig. 8. Both the AEWMA FSI and AEWMA VSI charts signal an out-of-control condition once the control statistic \(W{ = - }0.807\) exceeds the lower control limit \(H = { - }0.711\). Although both charts successfully detect the process shift, their detection speed differs noticeably. The AEWMA FSI chart issues a signal at the 42nd time unit, whereas the AEWMA VSI chart is significantly faster at 20.3 time unit. Consistently, across 50,000 simulated datasets, the average detection times are 34.64 for the AEWMA FSI chart and only 23.16 for the AEWMA-VSI chart.

The Gamma AEWMA FSI and AEWMA VSI charts corresponding to the data in Table 8 for upward shift \(c = {1}{\text{.1}}\).

Under identical parameter settings, the AEWMA VSI chart consistently achieves detection with a smaller \(ATS_{1}\), demonstrating superior detection efficiency. Its ability to identify abnormalities more rapidly can enable timely corrective actions, thereby reducing process losses and risks. These results align with earlier simulation findings and further confirm that the AEWMA VSI chart with dynamic sampling intervals offers greater efficiency and practicality for real-world applications than the traditional AEWMA FSI chart.

Conclusion

This study focuses on process data following a Gamma distribution. By applying the Wilson-Hilferty transformation to approximate skewed data to a normal distribution, AEWMA control charts with fixed sampling intervals (FSI) and variable sampling intervals (VSI) were developed. Simulation were conducted to evaluate the detection performance of the proposed charts under various shape parameters and shift conditions. The results indicated that the detection sensitivity was effectively enhanced by increasing the shape parameter. Between the AEWMA FSI and VSI charts, the downward shifts were generally detected faster than the upward shifts. Such Gamma-type processes are common in reliability, lifetime, and waiting-time applications, where the monitored quality characteristics are strictly positive and right-skewed. In these settings, the AEWMA framework offers improved sensitivity to small and moderate shifts in the transformed mean compared with conventional EWMA-type charts.

In practice, a short sampling interval in the AEWMA VSI chart improve responsiveness at the expense of higher sampling costs and more false alarms. A long sampling interval between 1.75 and 4, combined with suitable smoothing parameter adjusting, is therefore recommended to achieve a reasonable trade-off between detection performance and resource efficiency. Moreover, the comparison between the FSI and VSI schemes confirms that the VSI design can reallocate inspection effort more efficiently than FSI without reducing detection performance.

Future research can be extended in the following directions: (1) incorporating other skewed distributions such as Weibull or Log-normal to improve the robustness of the AEWMA control chart across different data structures; (2) integrating economic design principles to jointly consider the detection accuracy and cost-effectiveness, thereby enhancing the practical value; and (3) expanding to multivariate process monitoring to accommodate real-world scenarios involving multiple variables.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Sarwar, M. A. et al. A Weibull process monitoring with AEWMA control chart: An application to breaking strength of the fibrous composite. Sci. Rep. 13, 19873 (2023).

Capizzi, G. & Masarotto, G. An adaptive exponentially weighted moving average control chart. Technometrics 45(3), 199–207 (2003).

Haq, A., Gulzar, R. & Khoo, M. B. C. An efficient adaptive EWMA control chart for monitoring the process mean. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 34(6), 563–571 (2018).

Tang, A., Sun, J., Hu, X. & Castagliola, P. A new nonparametric adaptive EWMA control chart with exact run length properties. Comput. Ind. Eng. 130, 404–419 (2019).

Tang, A., Hu, X., Xie, F. & Zhou, X. Nonparametric adaptive EWMA-type control chart with variable sampling intervals. Commun. Statist. Simul. Comput. 53(8), 4001–4017 (2024).

Haq, A. & Khoo, M. B. C. An adaptive multivariate EWMA chart. Comput. Ind. Eng. 127, 549–557 (2019).

Noor-ul-Amin, M., & Sarwar, M. A. (2022). Function based adaptive EWMA control chart to monitor multivariate process dispersion. SSRN.1–23

Riaz, M. et al. An adaptive EWMA control chart based on principal component method to monitor process mean vector. Mathematics 10, 2025 (2022).

Kazmi, M. W. & Noor-ul-Amin, M. Adaptive EWMA control chart by using support vector regression. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 40(7), 3831–3843 (2024).

Ahmadini, A. A., Abbas, T. & AlQadi, H. Adaptive EWMA control chart by adjusting the risk factors through artificial neural network. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 41, 992–1001 (2024).

Reynolds, M. R. Jr., Amin, R. W., Arnold, J. C. & Nachlas, J. A. X bar charts with variable sampling intervals. Technometrics 30(2), 181–192 (1988).

Saccucci, M. S., Amin, R. W. & Lucas, J. M. Exponentially weighted moving average control schemes with variable sampling intervals. Commun. Statist. Simul. Comput. 21(3), 627–657 (1992).

Leoni, R. C., Sampaio, N. A. S., Tavora, R. C. M., Silva, J. W. J. & Ribeiro, R. B. Statistical project of control chart with variable sample size and interval. Am. J. Math. Statist. 4(4), 195–203 (2014).

Tang, A., Castagliola, P., Sun, J. & Hu, X. An adaptive exponentially weighted moving average chart for the mean with variable sampling intervals. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 33(8), 2023–2034 (2017).

Xuelong , H., Jiening, Z., Suying Z., & Liu, W. (2023). Variable sampling interval one-sided CUSUM control charts for monitoring the multivariate coefficient of variation. 35th Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC), 3194–3200.

Cheng, X.-B. & Wang, F. K. VSSI median control chart with estimated parameters and measurement errors. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 34(5), 867–881 (2018).

Haq, A., Sadia, H. & Khoo, M. B. C. A parameter-free adaptive EWMA chart with variable sample sizes and variable sampling intervals for the process mean. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 92(14), 2802–2828 (2022).

Tagaras, G. An integrated cost model for the joint optimization of process control and maintenance. J. Op. Res. Soc. 39, 757–766 (1988).

Maravelakis, P. E., Panaretos, J. & Psarakis, S. An examination of the robustness to non-normality of the EWMA control charts for the dispersion. Commun. Statist. Simul. Comput. 34(4), 1069–1079 (2005).

Liew, J. Y., Khoo, M. B. C. & Neoh, S. G. A study on the effects of a skewed distribution on the EWMA and MA charts. AIP Conf. Proc. 1605, 1034–1039 (2014).

Nawaz, M. S., Azam, M. & Aslam, M. EWMA and DEWMA repetitive control charts under non-normal processes. J. Appl. Statist. 48(1), 440 (2021).

Hamasha, M. M. et al. Symmetry of gamma distribution data about the mean after processing with EWMA function. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–12 (2023).

Derya, K. & Canan, H. Control charts for skewed distributions: Weibull, gamma, and lognormal. Metodoloski Zvezki 9(2), 95–106 (2012).

Goh, K. L., Teoh, W. L., Teoh, J. W., Chong, Z. L. & Chew, X. The one sided variable sampling interval exponentially weighted moving average X charts under the Gamma distribution. Sains Malaysiana 53(12), 3437–3462 (2024).

Gonzalez, I. M. & Viles, E. Design of R control chart assuming gamma distribution. Stochastic Qual. Contr. 16(2), 199–204 (2012).

Zhang, C., Xie, M., Liu, J. & Goh, T. A control chart for the gamma distribution as a model of time between events. Int. J. Prod. Res. 45(23), 5649–5666 (2007).

Liu, J. Y., Xie, M., Goh, T. N. & Chan, L. Y. A study of EWMA chart with transformed exponential data. Int. J. Prod. Res. 45(3), 743–763 (2007).

Sukparungsee, S. An EWMA p chart based on improved square root transformation. World Acad. Sci. Eng. Technol. Int. J. Phys. Math. Sci. 8(7), 1045–1047 (2014).

Scagliarini, M., Apreda, M., Wien, U. & Valpiani, G. Exponentially weighted moving average control schemes for assessing hospital organizational performance. Statistica (Bologna) 76(2), 127–139 (2016).

Aslam, M., Arif, O. H. & Jun, C. H. A control chart for gamma distribution using multiple dependent state sampling. Indus. Eng. Manag. Sys. 16(1), 109–117 (2017).

Aslam, M., Khan, N. & Jun, C. H. A control chart using belief information for a gamma distribution. Op. Res. Decis. 26(4), 5–19 (2016).

Khan, N., Aslam, M., Ahmad, L. & Jun, C. H. A control chart for gamma distributed var iables using repetitive sampling scheme. Pak. J. Stat. Oper. Res. 13(1), 47–61 (2017).

Saghir, A., Ahmad, L. & Aslam, M. Modified EWMA control chart for transformed gamma data. Commun. Statist. Simul. Comput. 50(10), 3046–3059 (2021).

Wilson, E. B. & Hilferty, M. M. The distribution of chi-square. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 17, 684–688 (1931).

Funding

This work was supported by National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, Grant Number: NSTC 113-2221-E-033-022.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shin-Li Lu, Meng-Chiao Chen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Writing—Original Draft. Jen-Hsiang Chen,Su-Fen Yang,Kashinath Chatterjee: Validation, Investigation, Data Curation, Visualization, Writing—Review & Editing. Shin-Li Lu: Resources, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, SL., Chen, MC., Chen, JH. et al. Considering AEWMA control chart applied to Gamma-distributed data with fixed and variable sampling intervals. Sci Rep 16, 1684 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31174-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31174-z