Abstract

Finding new drugs for adjuvant chemotherapy of colon cancer is of high priority. This study aimed to evaluate the antiproliferative properties and anticancer mechanisms of glucose (C) functionalized and juglone-conjugated zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles (NPs) [(ZnO@C-Juglone NPs)] on a colon cancer cell line (SW480). Physicochemical properties of the NPs were characterized by FT-IR, XRD, TEM, SEM-EDS, TGA, zeta potential and DLS analyses. MTT assay was used to explore the antiproliferative potential of the NPs. Cell cycle analysis and frequency of cell apoptosis and necrosis were determined by flow cytometry. Nuclear alteration and caspase-3 activity following treatment with ZnO@C-Juglone were determined and expression of the CASP8 and CASP9 genes as well as caspase-3 activity was evaluated to explore both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis pathways. The FT-IR and XRD analyses confirmed the successful synthesis and structural characteristics of ZnO@C-Juglone NPs, demonstrating the presence of juglone functional groups and the crystalline nature of ZnO. The particles were spherical with a diameter range of 10–90 nm, elemental constituents of C, O, and Zn atoms, a hydrodynamic size of 275.3 nm and a zeta potential of -50.3 mV. ZnO@C-Juglone NPs exhibited dose-dependent cytotoxicity and significantly reduced the viability of cancer cells (IC50 = 71 µg/mL). ZnO@C-Juglone NPs caused cell cycle blockage at the G2/M phase, elevated cell apoptosis and necrosis level, and considerable nuclear alterations. Treatment with NPs induced the CASP8 and CASP9 genes by 5.01 and 2.75-fold, respectively and enhanced caspase-3 activity by 6.18-fold. This work indicates promising anticancer properties of ZnO@C-Juglone, which could be employed in the development of innovative pharmaceuticals against colon cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With an estimated 20.0 million new cases and 9.7 million new deaths, cancer is the leading global health challenge. The prevalence of many types of cancer has been rising in recent years in the world1. Lifestyle choices, environmental influences and genetics are considered the major contributing factors for the upward trend of cancer2. Colorectal cancer remains the third most prevalent cancer in the world, causing more than 0.9 million deaths each year. The disease is also considered the second leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide1. Although early diagnosis and surgical removal of cancerous tissue are the primary therapeutic strategies in the treatment of colon cancer, and greatly affect the patient’s long-term outcomes, adjuvant chemotherapy is of particular importance, especially in advanced stages of the disease3. Despite its widespread use, adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer suffers from severe toxicity (e.g., hematologic, gastrointestinal, neurologic) that limits dosage and treatment duration. It is also undermined by the frequent emergence of drug resistance through mechanisms such as over-expression of ABC transporters, evasion of apoptosis, enhanced DNA repair, and changes in drug metabolism, which ultimately reduce efficacy and lead to treatment failure4. These limitations underscore the need for nanoparticle-based therapies that can improve targeting, reduce systemic side effects, and potentially overcome resistance.

Designing novel anticancer formulations derived from plants, herbs, and other biological sources may offer benefits such as enhanced therapeutic efficacy and improved safety. Therefore, exploring natural compounds may provide more effective and patient-friendly cancer therapies5. Juglone is a natural naphthoquinone, naturally found in the roots, leaves, bark, and wood of walnut trees. Many studies reported the antibacterial, antiviral, and antioxidant activities of juglone. Furthermore, the anticancer potential of juglone and its derivatives against various cancers such as cervical cancer, breast cancer, etc., has been reported in the literature. Previous studies revealed that juglone and its derivatives can inhibit the proliferation of cancer cells through inducing cell apoptosis and autophagy and inhibit tumor cell migration and invasion6,7,8. However, the low water solubility of juglone reduces its bioavailability and prevents achieving an effective therapeutic dose in the body, which limits the pharmaceutical applications of this substance. Therefore, many studies have focused on increasing the hydrophilicity and bioavailability of juglone to enhance its biomedical applications9.

Nanotechnology offers a new solution for efficient drug delivery to tumor tissues. Metal nanoparticles (NPs) are becoming effective tools in nanomedicine due to their relatively easy synthesis, low cost, long-term stability, and inherent anticancer properties10. Among various metal NPs, zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) have distinctive properties to be explored in pharmaceutical products. ZnO NPs were selected as the carrier system for juglone due to their distinctive combination of properties. ZnO is considered biocompatible and is FDA-approved for biomedical use, offering a safe platform for drug delivery. Having good biocompatibility, stability in the body, low toxicity, photocatalytic therapy potential, and inherent antimicrobial and anticancer properties, ZnO NPs are regarded as a promising platform for drug delivery. Recent studies have shown the efficiency of ZnO NPs for the delivery of bioactive compounds, particularly water-insoluble substances to cancer cells, offering improved bioavailability and more efficient anticancer efficacy. Additionally, due to the intrinsic anticancer feature of bare ZnO NPs, they may provide synergistic anticancer activity against cancer cells. Moreover, ZnO exhibits pH-sensitive dissolution, which enhances drug release in the acidic tumor microenvironment, further improving therapeutic selectivity. Moreover, ZnO exhibits pH-sensitive dissolution, which enhances drug release in the acidic tumor microenvironment, further improving therapeutic selectivity11,12,13.

Glucose was employed as a natural, biocompatible carbon precursor to functionalize ZnO nanoparticles. The resulting carbonaceous layer improves nanoparticle stability, aqueous solubility, and provides abundant hydroxyl and carbonyl groups that facilitate juglone conjugation. In addition, glucose residues on the nanoparticle surface may enhance selective uptake by cancer cells via glucose transporters (GLUTs), which are typically overexpressed due to their high glycolytic activity. This dual function of glucose contributes both to improved physicochemical performance and to the targeted anticancer action of the ZnO@C–Juglone nanoconjugate14.

Therefore, in this study, we conjugated juglone to ZnO nanoparticles via glucose functionalization and characterized the physicochemical properties of the synthesized NPs. We then evaluated the effects of ZnO@C-Juglone NPs on cell viability, cell cycle progression, and the activation of key apoptotic mediators (caspase-8, caspase-9, and caspase-3) in a colon cancer cell line (SW480). This comprehensive approach aimed to elucidate the involvement of both the intrinsic (mitochondrial) and extrinsic (death receptor-mediated) apoptosis pathways in the anticancer activity of ZnO@C-Juglone NPs. We hypothesized that ZnO@C-Juglone NPs would exert synergistic antiproliferative effects through induction of oxidative stress, cell cycle arrest, and activation of caspase-dependent apoptotic cascades.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and cell lines

All chemicals, including Zinc nitrate, NaOH, juglone, etc., were of analytical grade and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The human normal cell line, HDF, and colon cancer cell line, SW480, were received from the cell bank of the Pasteur Institute of Iran and propagated in DMEM medium. The SW480 cell line, derived from a primary human colorectal adenocarcinoma, was selected as a representative model for colon cancer because it retains key molecular characteristics of colorectal tumors, including p53 mutation and KRAS activation. This cell line is extensively used for evaluating apoptosis, oxidative stress, and antiproliferative responses to anticancer agents.

Synthesis of ZnO NPs

Initially, 100 mL of a 5 mM solution of Zn(NO3)2 was prepared in distilled water, and the pH was adjusted to 11.0 using NaOH solution. Next, the mixture was heated at 80 °C for 120 min, after which it was centrifuged at 10,000 RPM for 10 min. The pellet was collected, and ZnO NPs were washed with distilled water and dried at 70 °C for 8 h15.

Conjugation with juglone

Before conjugation with juglone, ZnO NPs were subjected to glucose functionalization in order to improve conjugation efficiency. To functionalize with glucose, one gram of ZnO NPs and 0.5 g of D-glucose (C) were suspended in distilled water and sonicated for 30 min. Next, the suspension was heated at 180 °C for 180 min. Then, the suspension was centrifuged and the functionalized NPs were collected, washed, and dried at 60 °C for 5 h15. In the next step, one gram of the functionalized ZnO NPs and one gram of juglone were suspended in 50 mL of distilled water and subjected to ultrasonication for 20 min. After shaking for 24 h, the suspension was centrifuged and ZnO@C-Juglone NPs were collected and freeze-dried.

Physicochemical properties of the NPs

An FT-IR spectrophotometry analysis was done on ZnO NPs, juglone, and ZnO@C-Juglone NPs. The analysis was done using a Nicolet IR-100 FT-IR device and in a wavelength range of 500–4500 cm− 1. ZnO@C-Juglone NPs were subjected to an XRD analysis using the Co-Ka X-radiation at k = 1.79 Å to elucidate the crystalline nature of NPs. Transmission electron microscopy (Zeiss EM-900 TEM) and scanning electron microscopy (TESCAN Mira3 SEM) were used to determine the morphology and particle diameter of ZnO@C-Juglone NPs. An EDS-mapping analysis was applied to characterize the elemental constituents of ZnO@C-Juglone NPs. The zeta potential and DLS analyses were performed to determine the surface charge and particle size in an aqueous medium using a Zeta sizer device (Malvern Ltd, 6.32). Particle stability was also determined using the thermogravimetric assay (TGA) using a Rheometric Scientific STA 1500 (USA) device. The initial formation of ZnO NPs was measured by spectrophotometric analysis using UV/Vis spectrophotometer DR-5000 device manufactured by (JASCO Co. Japan).

Cell culture and viability assay

The HDF and SW480 cells were propagated in the DMEM medium at 37 °C and 5% CO2supplementation. After cell propagation, 100µL of cell suspension (1 × 104 cells/well) was prepared in a 96-well cell culture plate and treated with a gradient of Juglone, ZnO, ZnO@C and ZnO@C-Juglone NPs (12.5–400 µg/mL). Cisplatin was used as a standard drug and the untreated wells were regarded as the control group. The plate was incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, after which cell viability in each well was determined using the MTT assay. In brief, 100µL of 0.5 mg/mL 2-(4,5-dimethythiazol-2-yl) −2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) solution was added to the wells for 4 hours. Next, the medium was removed and 100µL of DMSO solution was added. After incubation for 30 min, the absorbance at 570 nm was measured. The assay was done in three replicates and the percentage of the viable cells was calculated as follows16,17:

Analysis of cell cycle

A flow cytometry analysis was conducted to evaluate the cell cycle phases of the colon cancer cells in the control and treated groups. In brief, SW480 cells (5 × 105 cells) were treated with ZnO@C-Juglone NPs at a concentration of IC50 (50% inhibitory concentration) for 24 h. Next, cell staining was performed using propidium iodide (PI) and RNase A (BioLegend, USA). Finally, the cells were subjected to a flow cytometry analysis (ZE5 cell analyzer, Bio-Rad, USA), and cell cycle phases were determined based on the quantity of their DNA. Untreated cells were considered the control group.

Cell apoptosis/necrosis levels

To quantify the cell apoptosis/necrosis level, colon cancer cells from the control and ZnO@C-Juglone treatment groups were subjected to a flow cytometry assay. An initial cell population of 5 × 105 cells/mL was treated with the NPs, as described above, and then, cell staining was applied using the propidium iodide (PI) and Annexin V (BioLegend, USA) dyes and followed by a flow cytometry analysis to determine the percentage of necrotic and apoptotic cells. Untreated cells were considered the control group.

Hoechst staining assay

To perform the assay, the SW480 cells (5 × 105 cells) were initially treated with IC50 of ZnO@C-Juglone NPs for 24 h, while the untreated group was the control. Next, the cells were subjected to Hoechst staining using the Hoechst dye (1.25 mg/mL in PBS) for 15 min. Finally, the nuclear alterations in the treated cell were evaluated under a fluorescent microscope18.

Gene expression analysis

The expression levels of the CASP8 and CASP9 genes in colon cancer cells after treatment with ZnO@C-Juglone NPs were studied using a real-time PCR assay. Initially, the SW480 cells were treated with ZnO@C-Juglone NPs at the IC50 concentration (71 µg/mL) for 24 h at 37 °C. The untreated group was considered the control. The untreated group was considered the control. After incubation, the RNA extraction was conducted using a commercial RNA extraction kit (AddBio, South Korea), followed by a DNase I treatment. Next, cDNA molecules were synthesized using the AddBio cDNA synthesis kit (South Korea) according to the manual. The GAPDH gene served as the housekeeping gene, and gene amplification was performed using a SYBR Green real-time PCR master mix (AddBio, South Korea). The relative expression levels of the CASP8 and CASP9 genes were determined using the 2−ΔΔct method19. The primer sequences are listed in Table 1.

Caspase-3 activity

A colorimetric detection assay was conducted to determine the activity of caspase-3 in the SW480 cells treated with ZnO@C-Juglone NPs and untreated cells, using a Sigma-Aldrich (CASP3C) commercial kit. Initially, in a 6-well plate, the cells (5 × 106 cells/well) were treated with ZnO@C-Juglone NPs at their IC50 concentration for 24 h. Then, the treated and control cells were lysed and centrifuged. The supernatant was collected and mixed with DEVD-pNA. Caspase-3 activity was then quantified by measuring the OD405 due to p-nitroaniline (µM) release.

Statistical analysis

The experiments were performed in three replicates. Statistical analysis was done by one-way ANOVA test using the GraphPad Prism software (version 9.0) and the p-values of < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Physicochemical characterization

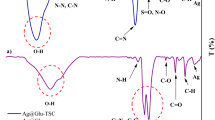

Figure 1(a) displays the FT-IR spectrogram of juglone, ZnO, and ZnO@C-Juglone NPs. The FT-IR spectrum of ZnO NPs indicates a peak at 489 cm− 1 that is related to the Zn-O band. The presence of the peaks at 2749–3720 cm− 1 is related to the O-H band, which is in agreement with previous reports20,21,22. The FT-IR spectrum of juglone displays two absorption peaks at 707.18 and 821.86 cm− 1, related to the C-H band, two additional peaks at 1133.12 and 1273 cm− 1, related to the C-O band, and also two peaks at 1587.66 and 1675.59 cm− 1 that are associated with the C = C and C = O bands, respectively23. ZnO@C-Juglone NPs showed a peak at 475.15 cm− 1, corresponding to the Zn-O band and two peaks at 7070.27 and 823.67 cm− 1 that are related to the C-H band. Additionally, the bands that are observed at 1134.43 and 1274.61 cm− 1 contribute to the C-O band and the observed peaks at 1559.97 and 1677.56 cm− 1 contribute to the C = C and C = O bands, respectively. The remaining peaks that are observed in the range of 2857–3422 cm− 1 contribute to the O-H band. The conjugation mechanism can be explained by two levels of interaction: (i) covalent Zn-O-C bands between ZnO NPs and glucose formed during functionalization, as evidenced by FT-IR shifts in O-H and C-O stretching vibrations, and (ii) hydrogen bonding between glucose hydroxyl groups and the carbonyl/hydroxyl groups of juglone, which accounts for the observed shifts in the C = O and O-H stretching regions. This hierarchical bonding model explains the stability of ZnO@C-Juglone NPs while preserving the biological activity of juglone. Considering reduced intensity and the shift of the peaks, the results indicate the functionalization of ZnO NPs and their conjugation with juglone.

The XRD analysis of ZnO, juglone and ZnO@C-Juglone NPs was displayed in Fig. 1(b). According to the results, the presence of intense peaks at 2θ of 31.79˚, 34.47˚, 36.32˚, 47.57˚, 56.62˚, 62.84˚, and 67.93˚ which corresponds to the (100), (002), (101), (102), (110), (103), and (112) plans, demonstrates that ZnO NPs were correctly synthesized and complies with the references24,25,26,27. The XRD spectrum of juglone displays the peaks at 2θ of 11.12˚, 22.25˚, and 26.72˚, suggesting the presence of juglone and agrees with a previous report23. In the XRD spectrum of ZnO@C-Juglone NPs, the peaks at 2θ of 11.04˚, 22.27˚, and 26.64˚ correspond to juglone, while the presence of low intensity peaks at 2θ of 35.19˚ and 45.54˚ indicates the presence of ZnO. Considering the high weight% of juglone and the overlapping of peaks related to ZnO and glucose, the successful synthesis of the NPs can be concluded.

The formation of ZnO NPs was initially confirmed by UV-vis spectroscopy within the range 200–600 nm (Fig. 1(c)). The ZnO solution shows the characteristic UV sharp peak absorption centered at 360 nm. According to the results, the results are consistent with previous references28,29.

Microscope electron imaging demonstrated that ZnO@C-Juglone NPs are almost spherical, arranged in small clusters and are in a size range of 10–90 nm in diameter (Figs. 2 (a&b)). Additionally, EDS mapping showed that the NPs contained C, O, and Zn atoms with a weight% of 70.6, 20.3, and 9.1%, respectively (Fig. 2©). The loading efficiency of Juglone on ZnO@C was calculated to be 90%. The hydrodynamic size of ZnO@C-Juglone NPs was 275.3 nm, indicating particle enlargement in an aqueous medium due to water absorption (Fig. 3(a)) and the zeta potential was − 50.3 mV (Fig. 3(b)). The high negative surface charge of the particles provides enough repulsive force between them to reduce particle agglomeration. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of ZnO@C-Juglone NPs (Fig. 3(c)) showed a three-step weight loss pattern. The first minor weight loss below ~ 120 °C is due to the release of adsorbed water and volatile molecules. A sharp weight reduction observed in the range of 180–300 °C corresponds to the thermal decomposition of organic moieties, including glucose functional groups and juglone molecules bound to the ZnO surface. A more gradual weight loss between 300 and 600 °C indicates further degradation of organic content and partial carbonization. Above 600 °C, the curve stabilized, suggesting that the ZnO crystalline core remained thermally stable. These findings confirm both the successful surface functionalization of ZnO NPs with juglone and the robust thermal stability of the synthesized hybrid NPs.

Results of cell viability

The viability of the SW480 and HDF cell lines treated with different quantities of ZnO@C-Juglone NPs was displayed in Fig. 4. The results revealed that the NPs had a dose-dependent toxicity for both cell lines; however, they showed considerably higher cytotoxicity in the cancer cells. In other words, ZnO@C-Juglone NPs caused a significant reduction in the viability of the normal cells at concentrations higher than 100 µg/mL and the IC50 (50% inhibitory concentration) was 200 µg/mL. In contrast, the minimum concentration of the NPs that caused a significant reduction in the viability of colon cancer cells was 25 µg/mL. The IC50 of ZnO@C-Juglone NPs for the cancer cells was 71 µg/mL. The selectivity index was ≈ 2.82. The results demonstrate the more intense cytotoxicity of the NPs for the colon cancer cells. Furthermore, treatment of SW480 cells with Juglone, ZnO@C and ZnO exhibited concentration-dependent cytotoxicity and resulted in an IC50 of 155, 197 and 217 µg/mL, respectively. The results indicate the boosted anticancer potential of ZnO@C-Juglone NPs compared to their constituent substances. The IC50 of Cisplatin in the SW480 cell line was 58 µg/mL.

Viability of the normal and colon cancer cells following the treatment with different concentrations of Cisplatin, Juglone, ZnO, ZnO@C and ZnO@C-Juglone NPs. The ZnO@C-Juglone NPs exhibited dose-dependent cytotoxicity which was more intense in the cancer cell line. (Data are normalized to untreated cells and reported as mean ± SD. Asterisks (*) indicate a significant difference with the control group (*= P < 0.05, **= P < 0.01, ***= P < 0.001).

Results of cell cycle

An analysis of the cell cycle phases of colon cancer cells revealed that treatment with ZnO@C-Juglone NPs resulted in 1.15% increase in cell cycle arrest during the subG1 phase. Additionally, a considerable blockage of the cell cycle was observed in the G2/M phase. The population of the cells at the G2/M in the untreated and treated groups was 13.56% and 54.57%, respectively. The results are displayed in Fig. 5.

Results of apoptosis induction

Flow cytometry analysis showed that treatment of the SW480 cells with ZnO@C-Juglone NPs increased cell necrosis from 0.90% in the control group to 7.42% in the treatment group. Primary apoptosis in the untreated and treated groups was 0.36% and 42.08%, respectively, and late apoptosis rose from 0.13% to 4.34% (Fig. 6). According to the results, ZnO@C-Juglone NPs increased cell necrosis and apoptosis in the cancer cells and the greatest increase was observed in early apoptosis.

Flow cytometry analysis of the control (a) and treated cells (b) demonstrates that ZnO@C-juglone NPs induces cells necrosis and apoptosis in colon cancer cell line. (c) Quantitative analysis of cell apoptosis/necrosis levels in the SW480 cell line. Q1: cell necrosis; Q2: late apoptosis; Q3: primary apoptosis, Q4: healthy cells.

Results of hoechst staining

In agreement with flow cytometry analysis, Hoechst staining of the colon cancer cells displayed characteristic nuclear alterations in the treated cells, including chromatin condensation and chromatin fragmentation, indicating the occurrence of apoptosis in the treated cells (Fig. 7).

Results of gene expression

The relative expression of the CASP8 and CASP9 genes in colon cancer cells after treatment with ZnO@C-Juglone NPs was investigated. According to the results, ZnO@C-Juglone NPs significantly elevated the expression of the CASP8 and CASP9 genes by 5.01 and 2.75-fold, respectively in the treated cells. The results were displayed in Fig. 8.

Expression of the CASP8 and CASP9 genes in the colon cancer cell line. Treatment with ZnO@C-juglone elevated the expression of the CASP8 and CASP9 genes by 5.01 and 2.75-fold, respectively. (Data are normalized to untreated cells and reported as mean ± SD. Asterisks (*) indicate a significant difference with the control group (***= P < 0.001).

Results of caspase-3 activity

Investigation of the activity of caspase-3 in the cancer cells indicated that exposure to the ZnO@C-Juglone NPs cause a significant activation of the enzyme activity. The activity of caspase-3 following treatment with ZnO@C-Juglone NPs was elevated by 6.18-fold (Fig. 9).

Discussion

Nanotechnology offers a promising approach for the delivery of therapeutic compounds to tumor tissues, particularly for drugs with poor water solubility and low bioavailability. This study represents a mechanistic view on the antiproliferative potential of ZnO NPs conjugated with juglone against colon cancer cells. Characterization of the antiproliferative effects of ZnO@C-Juglone NPs indicated that the NPs could reduce the viability of colon cancer cells more efficiently than normal cells, as they significantly reduced the viability of cancer cells at much lower doses compared to normal cells. A key novelty of this study lies in the use of glucose-mediated conjugation for juglone loading onto ZnO NPs. While nanoparticle functionalization with sugars has been reported for improving stability and biocompatibility, its application for juglone conjugation is scarcely documented. Our approach provides several advantages compared to direct juglone adsorption or chemical linker-based methods. First, glucose introduces abundant hydroxyl groups that act as anchoring sites, facilitating efficient juglone attachment through hydrogen bonding. Second, glucose acts as a natural, non-toxic capping agent, significantly improving colloidal stability, as evidenced by the highly negative zeta potential (− 50.3 mV). Third, glucose enhances the hydrophilicity and dispersibility of the NPs, which may increase juglone’s bioavailability and contribute to its selective anticancer activity. Taken together, these findings highlight glucose functionalization as a novel and biocompatible strategy for enhancing the physicochemical and biological performance of juglone-loaded ZnO NPs.

The anticancer activity of ZnO@C-Juglone NPs could be linked to the antiproliferative properties of juglone and zinc oxide. In this study, we observed that Juglone has concentration-dependent cytotoxicity in the cancer cell line. Studies have shown that juglone can exert its inhibitory effects on cancer cells through multiple mechanisms6. In a study, Maruo et al.30, discovered that juglone and its conjugated forms with fatty acid selectively inhibited the activity of human DNA polymerase γ, resulting in efficient suppression of human colon carcinoma cells, HCT116. Additionally, it has been reported that juglone can suppress the proliferation of various cancer cells through a modulation of AMP-activated protein kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin (AMPK/mTOR) pathway. Wang et al.31 found that juglone promotes generation of reactive oxygen species in cancer cells, such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and superoxide anion radical (O2• −), resulting in the activation of the AMPK/mTOR pathway, leading to induction of autophagy and cell death. In agreement with this finding, Zhong et al.32 reported that juglone treatment significantly increased intracellular ROS levels in lung cancer cell lines, causing activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway and ultimately leading to cell cycle arrest, activation of caspase-dependent proteolysis cascade and induction of cell apoptosis.

Similar to our finding, several reports also indicate the anticancer potential of ZnO NPs against various cancer cell lines, mainly through the induction of oxidative stress and apoptosis. Condello et al.33 reported that exposure of colon cancer cells to ZnO NPs significantly increased the intracellular ROS levels, ultimately leading to the activation of the apoptosis signaling pathway. The anticancer potential of ZnO NPs against various cancer cell lines has been documented in the literature34,35. Therefore, a synergistic anticancer activity of juglone and ZnO NPs, as observed in our study, can efficiently reduce the viability of the SW480 cells, primarily attributed to their complementary mechanisms of inducing oxidative stress, which plays a critical role in cancer cell apoptosis. The increased generation of ROS can disrupt redox homeostasis, leading to elevated levels of cellular damage, including lipid peroxidation, protein denaturation, and DNA damage, which finally results in triggering apoptotic pathways in cancer cells36.

Although the above mechanism is well-supported by previous literature, we acknowledge that intracellular ROS levels were not directly measured in the present study. Therefore, while ROS generation represents a plausible explanation for the observed cytotoxicity of ZnO@C–Juglone NPs, this interpretation remains hypothetical. Future studies incorporating quantitative ROS assays (e.g., DCFH-DA or MitoSOX staining) will be necessary to experimentally confirm this mechanism.

Cell cycle analysis of colon cancer cells demonstrated that exposure to ZnO@C-Juglone NPs remarkably increased cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase. Cell cycle blockage is an expected consequence of damage to vital parts of the cell, especially DNA, to repair the damage before entering mitosis. In agreement with our findings, previous studies reported that the exposure of cancer cells to juglone leads to the accumulation of the cells at the G2/M phase. Additionally, it was found that juglone can elevate protein levels of Chk2, phospho-Chk2, phospho-Cdc2, p21 and phospho-Cdc25C, but decrease Cdc2 levels6,37. In contrast, Fang et al.38 reported that juglone inhibits the proliferation of ovarian cancer cells by G0/G1 cell cycle blockage by the inactivation of cyclin D1 protein. In a recent study, Wang et al.39 reported that nano delivery of juglone to hepatocellular carcinoma cells could result in the upregulation of the p21 gene, and downregulation of Cyclin A and CDK2, leading to cell cycle arrest, which confirms the cell-blockage inhibitory effects of the synthesized NPs in our work. It has been reported that juglone can increase ROS levels in human cancer cells, which increases the mRNA and protein expression of p21 protein. The p21 is a Cdk inhibitor that is activated by p53 in response to DNA damage and effectively inhibits several Cdks, such as Cdk2, Cdk3, Cdk4, and Cdk640,41. Therefore, the induction of p21 in response to DNA damage due to exposure to ZnO@C-Juglone NPs can be a proposed underlying mechanism for cell cycle blockage in the treated cancer cells.

It should be noted that the involvement of specific regulatory proteins such as p21, Chk2, and Cdc2 is proposed based on previous literature and was not directly evaluated in this study. Further analyses at the protein and transcriptional levels will be necessary to validate these proposed pathways.

Flow cytometry analysis revealed that upon exposure of cancer cells to ZnO@C-Juglone NPs, the percentage of cell necrosis and apoptosis considerably increased compared to the untreated cells, favoring the primary apoptosis, which increased from 0.36% to 42.08%. In agreement with flow cytometry analysis, Hoechst staining confirmed apoptosis-associated nuclear alterations, such as chromatin condensation and fragmentation in the treated cells. Apoptosis induction in cancer cells through the generation of oxidative stress has been well documented. Increased ROS generation causes oxidative damage of cell components such as cell membranes, proteins, and mainly DNA damage, which are the initiator signals for the activation of apoptotic pathways. Some studies proved that juglone activates the P38 and P53 proteins in various cancer cells, leading to apoptosis induction, which is in agreement with our work. However, these signaling molecules were not examined experimentally in this study, and their role is suggested only as a possible mechanism supported by earlier reports31,32,42,43.

Although ZnO@C-Juglone treatment produced a measurable increase in necrosis (0.90% → 7.42%), the predominant cell-death signature was early apoptosis, with a smaller increase in late apoptosis. This pattern suggests that apoptosis is the primary mode of cell death under our experimental conditions, while necrosis could be either a secondary consequence of apoptotic progression or a direct cytotoxic effect of NPs. We therefore refrain from concluding that necrosis represents a separate dominant mechanism. Future mechanistic work (time-course Annexin V/PI, LDH release, caspase inhibition, ROS scavengers, and necroptosis markers) is required to resolve whether the observed necrotic cells result from late-stage apoptosis or from direct nanoparticle-induced necrotic pathways.

Characterization of the expression of the CASP8 and CASP9 in the treated cells revealed that exposure to the ZnO@C-Juglone NPs induced gene expression, which was followed by an activation in caspase-3 activity. Caspase-8 and − 9 are considered the initiators of the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis pathways, respectively, which are responsible for the subsequent activation of the executive caspases, such as caspase-3. The overexpression of CASP8 and CASP9, followed by the activation of caspase-3, indicates the activation of the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis in the treated cells. In agreement with our findings, previous studies reported that juglone can initiate both extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis in various cancer cell lines6. Juglone can induce proapoptotic proteins, including Bax, Fas, FasL, Caspase-3, p-JNK and p-c-Jun in cancer cells, which in turn, lead to activation of the apoptosis pathway44,45,46. In agreement with previous studies, we found that the expression of the CASP8 and CASP9 genes significantly increased in colon cancer cells treated with ZnO@C-juglon NPs. Caspase-8 and − 9 are the main initiator caspases responsible for the activation of the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis. Caspase-8, which is also related to the intrinsic apoptosis, is activated following the formation of the death-inducing signal complex (DISC), made of the cell surface death receptor (Fas) and ligand FasL. As observed in our study, the increased expression of CASP8 and CASP9 leads to the activation of caspase-3 and the progression of the apoptosis pathway. Furthermore, caspase-3 is related to boosting the activation of the intrinsic apoptosis through the activation of the Bid protein47.

In this work, we also observed that colon cancer cells were considerably more susceptible to ZnO@C-Juglone NPs, compared with normal cells. The higher susceptibility of cancer cells to the synthesized NPs seems to be mainly related to their lower resistance to exogenous ROS induction. Due to the higher energy consumption and rapid cell proliferation, cancer cells naturally produce higher levels of ROS than normal cells and are exposed to higher oxidative stress levels. This characteristic reduces their tolerance to the excess production of oxidative molecules caused by exogenous factors48. Furthermore, due to their higher nutritional requirements to provide sufficient nutrients and energy for high cell proliferation, cancer cells exhibit higher permeability to the extracellular matrix compared to normal cells49. This feature may also make them more susceptible to damage from exposure to antiproliferative agents, including the ZnO@C-Juglone NPs. However, further studies are needed to accurately identify the underlying mechanisms of this observation.

Conclusion

This work evaluates the antiproliferative and apoptosis induction potentials of ZnO@C-Juglone NPs in a colon cancer cell line. Our results show that the NPs have significant antiproliferative effects on cancer cells, and are more potent against cancer cells than against normal cells. Furthermore, the NPs induced cell cycle arrest primarily at the G2/M phase and triggered both extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis pathways by generating oxidative stress and activating initiator and executioner caspases. The current research demonstrates the promising anticancer effects of ZnO@C-Juglone NPs against colon cancer cells, representing a potential initial step in developing innovative treatments for this disease. While the synergistic activity of ZnO and juglone may involve ROS-mediated pathways, this mechanism was not directly evaluated in this work and warrants further investigation. Also, further characterizations using in vivo experiments are suggested to evaluate the safety and possibility of clinical application of ZnO@C-Juglone NPs.

Data availability

For the current study, “Targeted Anticancer Effects of Juglone-ZnO Nanoparticles via Cell Cycle Arrest and Caspase-8-Mediated Apoptosis in Colon Cancer Cells,” all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer J. Clin. 71 (3), 209–249 (2021).

Marino, P. et al. Healthy lifestyle and cancer risk: modifiable risk factors to prevent cancer. Nutrients 16 (6), 800. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660 (2024).

Baxter, N. N. et al. Adjuvant therapy for stage II colon cancer: ASCO guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 40 (8), 892–910. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.21.02538 (2022).

Hu, T., Li, Z., Gao, C. Y. & Cho, C. H. Mechanisms of drug resistance in colon cancer and its therapeutic strategies. World J. Gastroenterol. 22 (30), 6876. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i30.6876 (2016).

Asma, S. T. et al. Natural products/bioactive compounds as a source of anticancer drugs. Cancers 14 (24), 6203. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14246203 (2022).

Tang, Y. T. et al. Molecular biological mechanism of action in cancer therapies: juglone and its derivatives, the future of development. Biomed. Pharmacother. 148, 112785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2022.112785 (2022).

Zhang, W. et al. Anticancer activity and mechanism of juglone on human cervical carcinoma HeLa cells. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 90 (11), 1553–1558. https://doi.org/10.1139/y2012-134 (2012).

Bayram, D., Armagan, İ., Özgöcmen, M., Senol, N. & Calapoglu, M. Determination of apoptotic effect of juglone on human bladder cancer TCC-SUP and RT-4 cells: an in vitro study. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 37 (2). https://doi.org/10.1615/JEnvironPatholToxicolOncol.2018025226 (2018).

Hu, C. et al. Juglone promotes antitumor activity against prostate cancer via suppressing Glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation. Phytother. Res. 37 (2), 515–526. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.7631 (2023).

Radulescu, D. M. et al. Green synthesis of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles: a review of the principles and biomedical applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (20), 15397. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242015397 (2023).

Anjum, S. et al. Recent advances in zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) for cancer diagnosis, target drug delivery, and treatment. Cancers 13 (18), 4570. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13184570 (2021).

Batool, M., Khurshid, S., Daoush, W. M., Siddique, S. A. & Nadeem, T. Green synthesis and biomedical applications of ZnO nanoparticles: role of PEGylated-ZnO nanoparticles as doxorubicin drug carrier against MDA-MB-231 (TNBC) cells line. Crystals 11 (4), 344. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst11040344 (2021).

Swidan, M. M., Marzook, F. & Sakr, T. M. pH-Sensitive doxorubicin delivery using zinc oxide nanoparticles as a rectified theranostic platform: in vitro anti-proliferative, apoptotic, cell cycle arrest and in vivo radio-distribution studies. J. Mater. Chem. B. 12 (25), 6257–6274. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4TB00615A (2024).

Morais, M. et al. Glucose-functionalized silver nanoparticles as a potential new therapy agent targeting hormone-resistant prostate cancer cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 17, 4321. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S364862 (2022).

Mokhtari, H., Alkinani, A., Ataei-e jaliseh, T., Shafighi, S., Salehzadeh, A. & T., & Synergic antibiofilm effect of thymol and zinc oxide nanoparticles conjugated with thiosemicarbazone on pathogenic Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 49 (7), 9089–9097. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-023-08701-z (2024).

Hosseinkhah, M. et al. Cytotoxic potential of nickel oxide nanoparticles functionalized with glutamic acid and conjugated with Thiosemicarbazide (NiO@ Glu/TSC) against human gastric cancer cells. J. Cluster Sci. 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10876-021-02124-2 (2021).

Kumari, R., Saini, A. K., Kumar, A. & Saini, R. V. Apoptosis induction in lung and prostate cancer cells through silver nanoparticles synthesized from Pinus Roxburghii bioactive fraction. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 25 (1), 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00775-019-01729-3 (2020).

Abdulrahman, N. H. et al. The cytotoxic effect of conjugated iron oxide nanoparticle by Papaverine on colon cancer cell line (HT29) and evaluation the expression of CASP8 and GAS6-AS1 genes. Results Chem. 7, 101323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rechem.2024.101323 (2024).

Pfaffl, M. W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, e45. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/29.9.e45 (2001).

Vivek, C., Balraj, B. & Thangavel, S. Structural, optical and electrical behavior of ZnO@ ag core–shell nanocomposite synthesized via novel plasmon-green mediated approach. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 30 (12), 11220–11230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-019-01467-x (2019).

Dulta, K., Koşarsoy Ağçeli, G., Chauhan, P., Jasrotia, R. & Chauhan, P. K. Ecofriendly synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles by carica Papaya leaf extract and their applications. J. Cluster Sci. 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10876-020-01962-w (2022).

Hamdy, D. A. et al. New. Fabricated Zinc Oxide Nanopart. Loaded Mater. Therapeutic Nano Delivery Experimental Cryptosporidiosis Sci. Rep. ; 1319650. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46260-3 (2023).

Arayıcı, P. P., Acar, T., Özbek, T. & Acar, S. Enhanced antimicrobial potency and stability of juglone/β-cyclodextrin inclusion complexes: a comparative study of formulation methods. Mater. Res. Express. 11 (7), 075004. https://doi.org/10.1088/2053-1591/ad5e61 (2024).

Al-darwesh, M. Y., Ibrahim, S. S. & Hamid, L. L. Ficus carica latex mediated biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles and assessment of their antibacterial activity and biological safety. Nano-Structures Nano-Objects. 38, 101163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoso.2024.101163 (2024).

Perumal, P. et al. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Shilajit and their anticancer activity against HeLa cells. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 2204. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52217-x (2024).

Chemingui, H., Moulahi, A., Missaoui, T., Al-Marri, A. H. & Hafiane, A. A novel green Preparation of zinc oxide nanoparticles with hibiscus Sabdariffa L.: photocatalytic performance, evaluation of antioxidant and antibacterial activity. Environ. Technol. 45 (5), 926–944. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593330.2022.2130108 (2024).

Xing, L. et al. Fabrication of HKUST-1/ZnO/SA nanocomposite for Doxycycline and Naproxen adsorption from contaminated water. Sustainable Chem. Pharm. 29, 100757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scp.2022.100757 (2022).

Selva Arasu, K. A., Raja, A. G. & Rajaram, R. Photocatalysis and antimicrobial activity of ZnO@ TiO2 core-shell nanoparticles. Inorg. Nano-Metal Chem. 55 (5), 565–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/24701556.2024.2353742 (2025).

Manimaran, K. et al. Mycosynthesis and biochemical characterization of hypsizygusulmarius derived ZnO nanoparticles and test its biomedical applications. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. 14 (21), 27393–27405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-022-03582-y (2024).

Maruo, S. et al. Inhibitory effect of novel 5-O-acyl juglones on mammalian DNA polymerase activity, cancer cell growth and inflammatory response. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 19 (19), 5803–5812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2011.08.023 (2011).

Wang, P. et al. ROS-mediated p53 activation by juglone enhances apoptosis and autophagy in vivo and in vitro. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmcol. 379, 114647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2019.114647 (2019).

Zhong, J., Hua, Y., Zou, S. & Wang, B. Juglone triggers apoptosis of non-small cell lung cancer through the reactive oxygen species-mediated PI3K/Akt pathway. Plos One. 19 (5), e0299921. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0299921 (2024).

Condello, M. et al. ZnO nanoparticle tracking from uptake to genotoxic damage in human colon carcinoma cells. Toxicol. In Vitro. 35, 169–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tiv.2016.06.005 (2016).

Bai, D. P., Zhang, X. F., Zhang, G. L., Huang, Y. F. & Gurunathan, S. Zinc oxide nanoparticles induce apoptosis and autophagy in human ovarian cancer cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 6521–6535. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S140071 (2017).

Wahab, R. et al. ZnO nanoparticles induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in HepG2 and MCF-7 cancer cells and their antibacterial activity. Colloids Surf., B. 117, 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2014.02.038 (2014).

Zhao, Y. et al. Cancer metabolism: the role of ROS in DNA damage and induction of apoptosis in cancer cells. Metabolites 13 (7), 796. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo13070796 (2023).

Wang, P. et al. Juglone induces apoptosis and autophagy via modulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 116, 40–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2018.04.004 (2018).

Fang, F. et al. Juglone exerts antitumor effect in ovarian cancer cells. Iran. J. basic. Med. Sci. 18 (6), 544 (2015). MID: 26221477; PMCID: PMC4509948.

Wang, L. et al. Nano delivery of juglone causes cell cycle arrest and apoptosis for hepatocellular carcinoma therapy. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 93, 105431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jddst.2024.105431 (2024).

Zhang, Y. Y. et al. Mechanism of juglone-induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in Ishikawa human endometrial cancer cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 67 (26), 7378–7389. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.9b02759 (2019).

Harper, J. W. et al. Inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases by p21. Mol. Biol. Cell. 6 (4), 387–400. https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.6.4.387 (1995).

Wu, J. et al. Juglone induces apoptosis of tumor stem-like cells through ROS-p38 pathway in glioblastoma. BMC Neurol. 17, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-017-0843-0 (2017).

Hou, Y. Q. et al. Juglanthraquinone C induces intracellular ROS increase and apoptosis by activating the Akt/Foxo signal pathway in HCC cells. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2016 (1), 4941623. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/4941623 (2016).

Lu, Z., Chen, H., Zheng, X. M. & Chen, M. L. Experimental study on the apoptosis of cervical cancer Hela cells induced by juglone through c-Jun N-terminal kinase/c-Jun pathway. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 10 (6), 572–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apjtm.2017.06.005 (2017).

Catanzaro, E., Greco, G., Potenza, L., Calcabrini, C. & Fimognari, C. Natural products to fight cancer: A focus on juglans regia. Toxins 10 (11), 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins10110469 (2018).

Xu, H. L. et al. Anti-proliferative effect of juglone from juglans Mandshurica Maxim on human leukemia cell HL-60 by inducing apoptosis through the mitochondria-dependent pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 645 (1–3), 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.06.072 (2010).

Mandal, R., Barrón, J. C., Kostova, I., Becker, S. & Strebhardt, K. Caspase-8: the double-edged sword. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Reviews Cancer. 1873 (2), 188357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2020.188357 (2020).

Raza, M. H. et al. ROS-modulated therapeutic approaches in cancer treatment. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 143, 1789–1809. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-017-2464-9 (2017).

Papalazarou, V. & Maddocks, O. D. Supply and demand: cellular nutrient uptake and exchange in cancer. Mol. Cell. 81 (18), 3731–3748. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2021.08.026 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.S. and A.S.: Conceptualization. A.S. and A.S.: Methodology. M.SH., A.N.S., A.N.R., F.GH., M. K., R.M., Z.M.M., M.E.V., and Z.F.: Formal analysis and investigation. A.S. and A.S.: Writing Original Draft Preparation. M.SH., A.N.S., A.N.R., F. GH., M.K., R. M., Z.M.M., M.E. V. and Z.F.: Resources. A.S. and A.S.: Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Safa, A., Shafiei, M., Sangari, A.N. et al. Targeted anticancer effects of Juglone-ZnO nanoparticles via cell cycle arrest and caspase-mediated apoptosis in colon cancer cells. Sci Rep 16, 1513 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31183-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31183-y