Abstract

Barium bismuth borate sodium (BBBNDy) glasses doped with Dy2O3 (0–0.8 mol%, x = 0.2 mol%) were prepared via the melt quenching approach and examined under gamma irradiation. XRD confirmed the amorphous nature, while density measurements (4.3387–4.4743 g/cm3) revealed composition and irradiation-dependent variations. FTIR and Raman studies indicated Dy2O3-induced network modification through BO3/BO4 and BiO3/BiO6 units, with minimal structural degradation under irradiation. Optical studies revealed tunable band gaps and low Urbach energies (0.1752–0.2266 eV) reflecting good structural order. Photoluminescence spectra exhibited a strong yellow emission at 575 nm (4F9/2 → 6H13/2), with optimal intensity for BBBNDy3 glass. Gamma irradiation induced PL quenching at 575 nm, with intensity reduced by to 66.6% at 5 kGy and 87.2% at 15 kGy; still, Dy3+ emission remains detectable. These results highlight the dual role of Dy3+ ions as structural stabilisers and efficient luminescent activators, identifying BBBNDy3 glasses as a strong candidate for photonic devices operating in radiation environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Borate glasses, owing to the glass-forming ability of B2O3 (boric acid), offer structural flexibility, wide optical transparency, reduced melting temperatures, enhanced thermal/mechanical endurance, and strong rare-earth (RE) solubility1,2,3,4,5,6, making them attractive for solid-state lighting, fiber amplifiers, and radiation shielding applications1,2,3,7,8. Their high boron content provides a large neutron absorption cross section, and their effective atomic number (Zeff = 7.42) is close to that of human tissue, making them relevant for clinical radiation protection uses such as dosimeters and implants9. The borate glass structure comprises both trigonal (BO3) and tetrahedral (BO4) structural units, forming complex arrangements such as boroxyl rings and various cyclic units of borate groups, varying from diborate to pentaborate configurations4,8,10,11,12,13,14,15. However, the high phonon energy of B2O3 (~ 1300 cm−1) promotes non-radiative losses, which can be mitigated by incorporating heavy metal oxides (HMOs) like Bismuth oxide (Bi2O3) and Barium oxide (BaO), enhancing fluorescence efficiency4,7,16 and improving shielding performance due to their high atomic numbers and densities8,10. Bi2O3 contributes BiO3, and BiO6 units, enhancing chemical durability and optical density4,7,11, while BaO promotes NBO formation, restructures the network, and improves thermal and optical response8,17,18,19,20,21,22. Additionally, Sodium oxide (Na2O) serves as a flux to lower melting temperatures, encourages BO3 to BO4 transformation, improving chemical resistance and tunability of physical properties23,24,25,26. Borate glasses exhibit high rare-earth (RE) ion solubility, making them suitable hosts for photonic and radiation shielding applications27,28. Unlike conventional shielding materials like concrete and polymers, RE-doped borate glasses offer transparency, chemical stability, and radiation tolerance. Among them, Dysprosium oxide(Dy2O3)-doped glasses stand out for their characteristic emissions in the blue (4F9/2 → 6H15/2), yellow (4F9/2 → 6H13/2), and weak red (4F9/2 → 6H11/2) regions, as well as infrared emissions at 1.32 μm (6H9/2 → 6H15/2) making it suitable for energy-efficient lighting display panels and optical communication systems29,30,31,32,33. Additionally, Dy3+ luminescence is highly sensitive to local structural features, including symmetry distortions, coordination sites, and the NBO content, which can be tailored via compositional design and irradiation2,11,25,26,34,35.

Gamma irradiation, a powerful form of ionizing radiation, significantly alters the structural and optical properties of glass materials. When high-energy gamma photons penetrate a glass network, they excite and displace electrons from their ground state, create defects such as oxygen vacancies and non-bridging oxygen atoms (NBO), and multivalent cationic sites1,10, disrupting the network bonds, compaction, and the formation of color centers through electron or hole trapping1. Consequently, studies involving borate, silicate, and phosphate-based glasses have revealed that gamma irradiation impacts the structure, particularly in borate glasses, transformations between BO4 and BO3 groups, and increased NBO content1,36. Studies by Marzouk and Ghoneim16,37 have confirmed these changes, showing only mild alterations in the intensity, shifts in vibrational bands, and the emergence of new features of the FTIR bands following gamma irradiation of glass ceramic doped with REE (rare earth elements), mainly associated with the variations in the bond geometry, such as angles and lengths. Gamma ray exposure also affects the dielectric characteristics and mass density of lithium borate-based glasses due to enhanced polarizability introduced by NBO formation and compaction of the network1. Furthermore, gamma irradiation narrows the optical energy band gap in glass materials, resulting in defect levels within the band gap region and absorption centers decreasing transparency in the UV–visible region2,4. Despite these structural modifications, most glasses subjected to high-dose gamma irradiation (up to several Mrads) continue to exhibit an amorphous nature, demonstrating their structural resilience and potential for shielding against ionizing radiation, in nuclear reactors, space missions, and medical facilities1,38.

Unlike traditional shielding materials like concrete, polymers, or lead-based materials, glasses offer transparency, chemical stability, ease of fabrication, and tunable composition1,2,9, making them an attractive alternative for advanced shielding applications.

The current study focuses on barium bismuth sodium borate glasses (BBBNDy), wherein BaO is systematically replaced with varying concentrations of Dy2O3 (0–0.8 mol%). The aim is to comprehensively explore the influence of Dy2O3 incorporation on the glass systems physical parameters (e.g., density), structural features (via FTIR and Raman technique), and optical behavior (UV–Vis–NIR absorption, optical band gaps, and luminescence) of the glass system before and after gamma exposure (5, 10, and 15 kGy). Among all the prepared glass compositions, the one doped with 0.6 mol% Dy2O3 (BBBNDy3) demonstrated the most intense photoluminescence emission before gamma irradiation. Only this optimized sample, as doped and an undoped sample, was selected for gamma irradiation studies. This focused approach enables a clearer understanding of how gamma dose affects the structural, optical, and physical traits of BBBNDy glass systems.

Experimental techniques

Glass synthesis

A series of glasses with the formula 55B2O3–(20 − x) BaO–10Na2O–15Bi2O3–xDy2O3, (x = 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 mol%), was synthesized via the melt-quenching process. High-purity raw materials, including Boric acid (H3BO3, 99.5%), Barium carbonate (BaCO3, 99.9%), Sodium carbonate (Na2CO3, 99.9%), Bismuth oxide (Bi2O3, 99.9%), and Dysprosium oxide (Dy2O3, 99.9%), were precisely weighed according to the batch matrix using a digital balance. The weighed powders were then finely ground for 30 min to ensure uniform mixing.

Following homogenization, the powder mixture was loaded into a porcelain crucible and heated from room temperature to 1050 °C at 10 °C per minute in an electric furnace. Upon reaching 1050 °C, the melt was held for 20 min and stirred to enhance uniformity, followed by an additional 10-min hold to ensure complete homogenization before quenching. The melt was poured into steel rings placed on a brass plate to obtain pellet-shaped samples at room temperature. Immediately after pouring, a brass weight was placed over the melt within the rings to minimize the thermal stress, ensuring the formation of stable glass pellets. Before evaluating the properties, a thickness of approximately 1–2 mm was achieved by polishing the glass samples with graded emery papers of varying grit sizes (320, 600, 800, 1000, 1200, and 1500) to achieve a smooth and uniform surface. Table 1 provides details on sample codes, compositions, and molecular weight (Mw) of the BBBNDy series. The prepared glass samples exhibited a distinct yellow coloration and good transparency, as displayed in Fig. 1, along with the synthesis flowchart.

Material characterization methods

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was carried out using a Rigaku Miniflex 600 benchtop diffractometer confirmed the non-crystalline nature of the BBBNDy glasses. It operates at 40 kV, 15 mA copper X-ray tube, generating Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). It supports scanning speeds from 0.01 to 100°/min, making it suitable for the specified 2°/min scan rate for analysis of powder samples. To evaluate the density of the glass system, Archimedes’ principle was employed. Toluene was selected as the immersion medium, and each sample was weighed in air and then in toluene. Each Measurement was repeated, and an average was taken for improved accuracy. The density (\(\rho\), g/cm3) was determined using the following formula (1)39

where \(W_{a}\) and \(W_{l}\) represents the respective weights of the samples in air and when suspended in toluene, where \(\rho_{l} = 0.8669\) g/cm3.

Based on the experimentally determined density and molecular weight (\(M_{w}\), g/mol), the molar volume (\(V_{m}\)) of the BBBNDy glass samples was evaluated using the Eq. (2)40:

Utilizing the measured density and molar volume, the average boron–boron separation (\(D_{{\left\langle {B - B} \right\rangle }}\)) and oxygen packing density (OPD) of the BBBNDy glasses were computed from relations (3) and (4)41,42

where \(N_{A}\) denotes Avogadro number, \(X_{B}\) indicating the B2O3 molar fraction, and \(n\) refers to the number of oxygen atoms per glass formulation, respectively.

The microstructure and surface morphological features and elemental analysis of the glass specimens were analyzed using a Carl Zeiss EVO 10 SEM equipped with secondary and backscatter electron detectors, offering a 3 nm resolution at 30 kV, 7 × 106× magnification, and joystick-controlled stage movement (X: 80 mm, Y: 100 mm, Z: 35 mm). Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) was employed to analyze the mass percentages of the elements present, as per the X-ray interactions that reveal unique atomic structures. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) measurements were carried out with a Bruker Alpha II spectrometer utilizing a diamond crystal attenuated reflectance (ATR) unit. The samples in the form of powder are directly used for analysis. Spectral acquisition covered the 400–4000 cm−1 region, employing a resolution of 4 cm−1, operating with OPUS version 7.8 software for data acquisition and analysis. Raman spectra were recorded using a Horiba Scientific Xplora plus confocal Raman spectrometer equipped with a 785 nm diode laser, across a 50–3000 cm−1 range. The spectral resolution was ≤ 1.4 cm−1/pixel equipped with a 2400 grooves/mm grating. All measurements are performed at room temperature.

The spectra of optical absorption about the investigated glasses in the 190–2500 nm range with a spectral resolution of 1 nm, utilizing a PerkinElmer Lambda 750S UV–VIS–NIR spectrophotometer. The absorption coefficient (α) was computed from absorbance (a) and sample thickness (d) as per Eq. (5)43,

The direct and indirect optical energy band gap, \(E_{opt}\) for the BBBNDy glasses were evaluated using the Mott and Davis relation44 outlined in Eq. (6), which links the absorption coefficient α(ν) and \(E_{opt}\).

Here \(h\nu\) represents the photon energy, \(D\) is a proportionality constant, and \(k\) defines the nature of the electronic transition, with values of 2 and 1/2 for direct and indirect allowed transitions, respectively.

Urbach energy (\(E_{U}\)) measures the degree of structural disorder or defects within amorphous materials. Transitions involving the localised tail states extending from the valence and conduction band edges into the forbidden energy region45, \(E_{U}\) characterises this behaviour and is evaluated using relation (7), where G is a constant.

Steepness parameter (\(S\)), indicating electron–phonon induced broadening of the absorption edge46, is obtained from Eq. (8),

where \(k_{B}\) and T stands for the Boltzmann constant, and temperature in Kelvin, respectively.

Refractive index (\(n\)), an important optical parameter that is influenced by the internal electric field and the polarizability of ions in the material, was evaluated using the relation (9)47:

The metallization criterion (\(M\)), which predicts whether the material exhibits metallic or insulator behaviour, was evaluated by applying the following expression (10)48:

where \(R_{m}\) and \(V_{m}\) are the molar refraction and the molar volume, respectively.

Numerical aperture (NA), calculated using the relation (11)49

\(n\) stands for the refractive index, and \(\delta\) signifies the fractional deviation in its value (0.01).

The surface reflection loss (\(R_{L}\)) from the glass was determined through the given formula (12)50:

An expression involving the refractive index (\(n\)) was employed to determine the optical transmission (\(T\)) (13)51:

Photoluminescence excitation and emission spectra were recorded using a JASCO FP-8500 spectrofluorometer, operating over the 200–800 nm wavelength range, equipped with a xenon flash lamp and a pulsed laser as excitation sources.

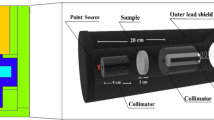

Glasses are irradiated with Gamma Chamber 5000 (BRIT, India) equipped with a Co-60 source, which ensures uniform gamma radiation exposure52. The samples underwent irradiation at a dose rate of 2.5 kGy/h for durations of 2, 4, and 6 h, corresponding to cumulative doses of 5, 10, and 15 kGy, respectively.

Results and discussions

Properties before irradiation

X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD)

The synthesized BBBNDy glasses exhibited an amorphous phase as evidenced by XRD patterns recorded between 10° and 80° range, as depicted in Fig. 2. The diffraction pattern for all BBBNDy glass samples exhibits broad and diffuse scattering at lower angles (~ 20° to ~ 35°). The absence of well-defined peaks indicates structural disorder in the glass network, thereby verifying the amorphous characteristics of the synthesized samples8,40.

Physical properties

Density (ρ) and molar volume (V m)

Table 2 and Fig. 3 reveal an inverse correlation between density and molar volume, resulting from the incorporation of Dy2O3 into the BBBNDy glasses, calculated using relations (1) and (2). The observed variations in the density of BBBNDy with increasing Dy2O3 content are primarily attributed to three factors: (1) The difference in molar mass between Dy2O3 and BaO, i.e., Dysprosium (162.5 u) is heavier than barium (137.3 u), generally increasing density. (2) The change in average molecular weight of the constituent oxides due to substitution of BaO with heavier Dy2O3, and (3) The influence of Dy3+ ions on the structural arrangement of the glass matrix. However, trivalent dysprosium ions possess an ionic radius (1.03 Å) smaller compared to Ba2+ ions (1.35 Å), resulting in structural rearrangements. Dysprosium, owing to its compact ionic size and higher atomic weight relative to barium, influences overall compactness and mass distribution within the network. Additionally, Dy2O3 serves to modify the glass network, facilitating the formation of NBOs, thereby altering the local structural configuration and density, hence affecting the density behavior across the BBBNDy glasses. Such behavior is consistent with findings from other RE-doped glasses40,43,53,54.

The density of the BBBNDy glasses shows a minor change with increasing Dy2O3 concentration. It decreases from 4.404 g/cm3 for BBBNDy0 to 4.339 g/cm3 for BBBNDy1, then increases to a peak of 4.474 g/cm3 for BBBNDy2, followed by a slight decline at higher concentrations. As shown in Fig. 3, this behavior can be linked to structural changes across the glass network. At certain Dy2O3 concentrations, tighter atomic packing resulting from enhanced BO connectivity elevates the density values. At others, Dy2O3 disrupts the network, causing depolymerization, void formation, and generation of NBOs, causing density to decrease. The molar volume trends similarly reflect these structural changes as depicted in Fig. 3. Initially, Dy2O3 incorporation expands the structure by reducing the BO bonds, but at higher concentrations, the network stabilizes, reducing fluctuations in the molar volume as mentioned in Table 2.

Average boron–boron distance and oxygen packing density

Average boron-boron distance (\(D_{{\left\langle {B - B} \right\rangle }}\)) calculated using the empirical relation (3) signifies the separation connecting a pair of boron atoms in the network and indicates structural compactness. As shown in Table 2 and Fig. 4, \(D_{{\left\langle {B - B} \right\rangle }}\) exhibits slight fluctuations with increasing Dy2O3 content. It initially increases from 4.286 Å for the undoped BBBNDy0 sample to a maximum of 4.310 Å at 0.2 mol% (BBBNDy1), then decreases and stabilizes around 4.296 Å (BBBNDy4). These subtle fluctuations suggest minor structural rearrangements within the borate glass network as modifier content increases.

Oxygen packing density (OPD), which measures how densely oxygen atoms are packed in the glass, was computed through the formula (4) and also shows compositional dependence as presented in Fig. 4, reflecting the tightness of the oxide network arrangement. It initially decreases, reaches a maximum value of 57.104 mol/L at 0.4 mol% of Dy2O3, and then stabilizes, as presented in Table 2. These variations reflect changes concerning the molar volume and packing density of the glass matrix, indicating alternating densification and modification induced by the incorporation of Dy2O3.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS)

When energetic electrons interact with atoms in borate glass samples, a range of signals is generated that reveal essential insights into the surface structure and elemental distribution of the material. SEM, in particular, plays a vital role in visualizing the surface morphology, while EDX provides a complementary compositional analysis. As each element has a distinct atomic structure, it results in a characteristic set of X-ray emission peaks.

SEM micrographs of the BBBNDy glasses revealed surfaces with dispersed grain-like features, with no evidence of long-range periodicity or crystalline phases55. At higher magnification of 5.00 KX, as shown in Fig. 5, irregular grain sizes, random distribution of surface particulates, and a continuous phase were observed in the range of a few hundred nanometers, which is characteristic of glass systems56. According to the EDS spectra in Fig. 6, the BBBNDy glasses contain key constituents including B, Ba, Na, Bi, Dy, and O and the corresponding EDS weight% values. A gradual increase in Dy peak intensity from BBBNDy1 to BBBNDy4 indicates successful Dy2O3 incorporation. The Dy content increased from 0.8 wt% (BBBNDy1) to 3.9 wt% (BBBNDy4), in agreement with the nominal doping levels. Minor variations in peak intensity indicate slight elemental inhomogeneity, a characteristic of amorphous systems. This non-uniform distribution may influence the structural arrangement of glass and related properties, as elaborated in subsequent sections. Lack of extraneous peaks confirms the chemical purity within the samples and indicates the absence of elements from porcelain crucibles43,57,58.

FTIR spectroscopic analysis

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy is a widely adopted and insightful method in materials research for analyzing structural modifications, enabling the differentiation of various functional groups present in glass materials. This technique relies on the principle that each molecule possesses distinct vibrational modes, which serve as a unique fingerprint for its identification. The glass networks’ vibrational modes are independent of those corresponding to other functional groups in other regions43. The region in the mid-infrared, i.e., (400–1600 cm−1), is of particular interest, as the vibrational modes in bismuth-borate glasses are primarily active within this range59. Figure 7 presents the FTIR spectra of BBBNDy glasses, while Fig. 8 illustrates their cation-related vibrational modes. Several studies60,61 report that Bi2O3 in B2O3 can participate in the glass structure in three distinct ways: (1) Oxygen donation to borate structure promotes the development of four-coordinated boron (BO4) units. (2) By forming BiO3 pyramidal structures, characterized by C3V symmetry, and (3) Through the addition of NBO atoms, the network connectivity is reduced60,61.

The absorption band around ~ 450 cm−1 is associated with the vibration of metal cation Na2+, Ca2+ ions62,63. The absorption bands below ~ 650 cm−1 signify vibrations of the Bi–O bond, originating from both BiO6 octahedral and BiO3 pyramidal units64. BiO3 structural units are characterized by four primary vibrational modes: a symmetric vibration around ~ 840 cm−1, a two-fold degenerate stretching vibration within the ~ 540 to ~ 620 cm−1 range, a symmetrical bending mode near 470 cm−1, and a bending mode exhibiting double degeneracy approximately at ~ 350 cm−165,66,67. In the present investigation, the manifestation of these modes may vary, with only certain bands being detectable based on the local structural environment and specific glass composition.

To resolve overlapping peaks and extract detailed structural information, the FTIR spectra were deconvoluted using Gaussian peak fitting. As shown in Fig. 9, this analysis resolved vibrational modes in the 800–1100 cm−1 and 1200–1600 cm−1 regions, confirming the presence of BO4, BO3, and Bi–O structures. Deconvoluted results reinforce the assignments made from the raw spectra and provide deeper insight into the glass matrix. The absorption band observed ~ 699 cm−1 to ~ 702 cm−1 is attributed to the symmetric Bi–O stretching modes characteristic of BiO3 pyramidal units; thereafter, bending vibrations of O3B–O–BO3 may contribute to overlapping spectral features68,69,70. The region between ~ 709 and 751 cm−1 is attributed to stretching vibrations of B–O bonds in BO4 tetrahedral configurations71. The region between ~ 833 and 1059 cm−1 is attributed to BO4 stretching vibrations from B–O linkages. These units are likely connected via bismuth cations, implying the existence of B–O–Bi linkages incorporated into the glass network64,72.

The absorption band within ~ 1198 cm−1 to 1295 cm−1 corresponds to asymmetric B–O stretching vibrations in BO3 units, commonly linked to ortho and pyro-borate species71. ~ 1312 cm−1 to 1361 cm−1 ascribed to the asymmetric B–O stretching vibrations in BO3 groups within boroxyl rings, indicating the presence of three-membered borate ring structures71. ~ 1397–1443 cm−1, region corresponds to vibrational modes involving Bi–O bonds in BiO6 and BiO3 structural units, as well as stretching B–O vibrations in BO3 groups originating through various borate species71,73. The assigned vibrational bands and their peak positions are listed in Table 3. The band positions slightly shift with the dopant concentrations, showing the structural rearrangements.

As reported by Pascuta et al. and other studies74,75,76 and illustrated in Fig. 7, the IR spectra reveal that the introduction of RE ions induces minimal changes in the absorption features of the glasses owing to the rigidity of the RE-doped bismuth borate matrix.

Raman spectral analysis

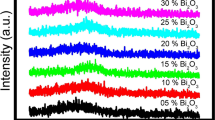

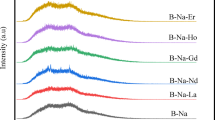

Raman spectroscopy was utilized to analyze the vibrational modes and structural network of the BBBNDy glasses. Spectra in Fig. 10 were recorded in the 50–2200 cm−1 range, where key vibrational features of borate and bismuth units are typically active. The broad and diffuse features in the spectra indicate the non-crystalline structure of the glasses. The corresponding Raman peak positions and their vibrational assignments are summarized in Table 4.

Low frequency band at ~ 65–98 cm−1 corresponds to vibrational modes of Bi3+ ions exhibiting Eg symmetry, typically associated with doubly degenerate bending modes within BiO6 octahedral units63,71. The range ~ 154–199 cm−1 is related to vibrational behavior of the Bi3+ ion coordinated in BiO3 pyramids and BiO6 octahedra structures, along with Bi–O stretching modes with these structural configurations in the glass matrix77,78. Bands observed at ~ 244–266 cm−1 correspond to Bi–O–Bi vibrations arising from both BiO6 octahedra and BiO3 pyramid structural units in the glass network79,80. Region ~ 339–450 cm−1 bands, attributed to linkages of Bi–O–Bi associated with BiO6 octahedra configurations, overlapping with the vibrational features of [BO3] and [BO4] coordination environments in the glass64,81. ~ 628 cm−1 peak is assigned to B–O vibrations due to stretching with [BO4] tetrahedral units and linkages of B–O–B, commonly observed due to meta and tetraborate groups71. The band ~ 754 cm−1 arises from the symmetric vibrational stretching of B–O bonds in BO4 tetrahedra, particularly associated with orthoborate groups, and is likely influenced by pyramidal modes of Bi2O371,82.

In general peak near 800 cm−1 evidences the existence of boroxyl units in the borate glass. However, the spectra of the investigated glasses exhibit no distinct features in this region, indicating the lack of boroxyl rings in the structure of the studied glasses. The peak observed at ~ 1195 cm−1 is assigned to the Asymmetric stretching of terminal B–O bonds in [BO3] units, specifically associated with the pyroborate structural units83. In the region ~ 1337–1387 cm−1, bands correspond to B–O stretching vibrations with tetrahedral [BO4] units, indicating the presence of well-defined tetrahedral borate configurations84. The peak at ~ 1657 cm−1 corresponds to the stretching vibrations of terminal B–O bonds associated with pyro-borate structural units, indicating their presence within the glass network85. Nonetheless, the Raman spectral features of BBBNDy glasses with varying Dy2O3 concentrations remain largely unchanged, indicating that the addition of Dy2O3 does not significantly alter the glass structure, likely due to the relatively low concentration compared to glass formers.

Optical properties

The absorption spectra of Dy2O3-doped glass samples recorded in the spectral range of 400–1800 nm are shown in Fig. 11. A series of absorption bands are observed, corresponding to the characteristic 4f–4f transition of Dy3+ ions starting from the 6H15/2 ground state to various higher energy levels. These transitions include: 4I15/2, 4F9/2, 4H7/2, 6F3/2, 6F5/2, 6F7/2, 6F9/2, 6F11/2, 6H11/2 at wavelengths 447 nm, 473 nm, 539 nm, 751 nm, 799 nm, 889 nm, 1086 nm, 1263 nm, and 1672 nm, respectively. These transitions are consistent with earlier reports86,87,88.

The spectra exhibit higher intensity and broader peaks in the NIR region compared to the UV–visible region. Such a response arises from the hypersensitive nature of the 6H15/2 → 6F11/2 transition near 1263 nm, which shows pronounced variation in intensity with the surrounding environment of Dy3+ ions. This transition follows the electric dipole selection rules \(\left| {\Delta S} \right|\)= 0, \(\left| {\Delta L} \right| \le 2,\) and \(\left| {\Delta J} \right| \le 2\), making Dy3+ ions hypersensitive to changes in the local glass structure89,90. Increasing Dy2O3 content from 0 to 0.8 mol%, a steady rise in absorption peak intensities is observed, indicating successful incorporation of Dy3+ ions into the glass matrix.

Optical energy band gaps (E opt), Urbach energy (E U) and steepness parameter (S)

The optical energy band gap (\(E_{opt}\)) plays a critical role in understanding the electronic transitions and bonding nature in oxide glasses. It denotes the minimum energy needed to transfer an electron across the band gap. In amorphous systems like Dy2O3-doped BBBNDy glasses, the evaluation of \(E_{opt}\) helps reveal variations in structural reorganisation and chemical bonds of the network owing to the non-crystalline nature of the material.

To determine \(E_{opt}\), UV–VIS–NIR spectral analysis was recorded for the as-prepared glasses. The absorption coefficient (α) was estimated based on the absorbance (a) and thickness (d) of the sample using the relation (6). Tauc plots were constructed by plotting \(\left( {\alpha h\nu } \right)^{k}\) versus \(h\nu\) to estimate the optical energy band gap, by linearly extrapolating the curves to the X-axis as depicted in Fig. 12.

For the BBBNDy glass system, the direct energy band gap (\(E_{opt} )\) values were found between 2.729 and 2.957 eV. Similarly, the indirect energy band gap (\(E_{opt} )\) values were found to be 2.589 to 2.807 eV. The non-linear variations in both direct and indirect energy band gaps were observed, which aligns well with the FTIR results. In glasses, the optical band gap is primarily influenced by two key factors: the distribution of anions and cations involved in the network, and the proportion of NBOs present in the structure. The band gap of the glass decreases with increasing average atomic number, and the presence of NBOs, as electrons associated with NBOs require less energy to make a transition to the conduction band compared to those from BOs. Variations in band gap can also arise from changes in symmetry and local field strength due to interactions between the rare earth (RE) ions and the glass matrix91,92. The observed increase in the band gap at specific Dy2O3 concentrations is attributed to the formation of BO units, which enhance the network compactness and lead to band widening91,92.

Urbach energy (\(E_{U}\)) was determined from the linear portion of the ln (α) vs. hν plot, followed by taking the inverse of the slope. Calculated EU values are tabulated in Table 5, ranging from 0.175 to 0.227 eV. A Lower Urbach energy suggests a reduced density of localized states in the band tails, and structural stability93,94, indicating that Dy2O3 doping introduces more defects into the glass matrix, thereby affecting its optical properties.

Steepness parameter (\(S\)) computed from relation (8) and tabulated in Table 5, demonstrated an inverse proportionality to the EU values, ranging from 0.114 to 0.148. BBBNDy glass samples increased disordering results in the development of defect-induced states in the band gap41 and hence a decrease in the optical band gap.

Refractive index (n), metallization criteria (M), and numerical aperture (NA)

The refractive index of a material shows a direct correlation with its density; an increase in density generally results in a higher refractive index. Glass with a higher refractive index indicates that light travels more slowly through the medium, signifying greater optical density. The refractive index calculated using Eq. (9) was found to vary between 2.409 and 2.474 with the inclusion of Dy2O3 content in BBBNDy glasses, and it is highest for BBBNDy2 glass with a value of 2.474. Here, the increase in the value of n is attributed to structural compactness and denser packing of atoms or ions within the network, and vice versa. As glass becomes denser, its ability to polarize in response to an electromagnetic field also increases, leading to an enhanced optical response. The values of n in BBBNDy glasses are calculated using the direct energy band gap.

The insulating characteristics of the synthesized BBBNDy glass samples were evaluated using the metallization criteria, by Eq. (10). The calculated M values for Dy2O3-doped BBBNDy glasses were found between 0.369 and 0.385, well below the critical threshold of 1(one)42. This confirms the insulating behavior of the glasses. The lower values of M with Dy2O3 addition suggest a more pronounced non-metallic nature, likely due to enhanced structural compactness in the network.

The numerical aperture (NA), which measures the light-gathering capability of the material and is also linked to the refractive index (n) via Eq. (11), varied between 0.341 and 0.345. The NA follows a similar trend with refractive index, increasing with Dy2O3 content up to a certain level, then stabilizing at higher concentrations. This trend signifies good light collection efficiency, which is advantageous for optical applications95. The refractive index, metallization criteria, and the numerical aperture values of the BBBNDy glass system with increasing Dy2O3 content are tabulated in Table 5.

Reflection loss (R L) and optical transmission (T)

The reflection loss (\(R_{L}\)), which quantifies the amount of light reflected from the material’s surface influenced by its refractive index48, is described by the Eq. (12). The \(R_{L}\) values in the BBBNDy glass system vary slightly from 0.171 to 0.180, which correlates with the refractive index behavior. The increase in refractive index with Dy2O3 content results in a marginal rise in reflection loss, peaking for BBBNDy2 glass at 0.180 before stabilizing.

The optical transmission (T) values varied from 0.695 to 0.708, calculated from the relation (13). A lower \(R_{L}\) or high T is preferred for optimal optical transmission, and the observed values suggest satisfactory optical clarity in the glasses. \(R_{L}\) and T findings are tabulated in Table 5.

Photoluminescence (PL) analysis

The emission profiles obtained from PL analysis of Dy2O3-doped BBBNDy glasses were examined under an excitation wavelength of 389 nm and are depicted in Fig. 13. The spectra reveal four distinct emission bands in the range of 450–750 nm, corresponding to the characteristic 4f–4f transitions of Dy3+ ions. The key emission peaks observed at approximately 483 nm (blue), 575 nm (yellow), 665 nm (red), and 753 nm are associated with the electronic transitions 4F9/2 → 6H15/2; 6H13/2; 6H11/2 and 6H9/2, respectively96,97.

Among these, the transition 4F9/2 → 6H13/2, exhibiting electric dipole behavior and following the selection rules ∆J = 0 or ± 2, is hypersensitive, with the highest intensity. This hypersensitivity renders it highly sensitive to the asymmetry and the surrounding environment around the Dy3+ site. Conversely, a magnetic dipole transition with low intensity 4F9/2 → 6H15/2, follows the selection rules ∆J = 0 or ± 1, and is minimally influenced by such factors98,99. Figure 13 demonstrates that emission intensity increased with Dy2O3 content up to 0.6 mol%; however, a further increase results in a decline, which can be ascribed to concentration quenching effects, primarily resulting from RET (resonance energy transfer) and CRC (cross relaxation channels) mechanisms among Dy3+ ions. From Fig. 14, the observed energy transfer pathways include the following:

(a) 4F9/2:6H15/2 → 6H15/2:4F9/2, (b) 4F9/2:6H15/2 → 6F3/2:6F11/2, (c) 4F9/2:6H15/2 → 6F5/2:6F9/2, and

(d) 4F9/2:6H15/2 → 6F11/2:6F3/296.

Yellow to blue (Y/B) intensity ratio and CCT diagram

The Y/B intensity ratio is a useful indicator of the asymmetry in the Dy3+ ion environment and is calculated for the BBBNDy glasses, as presented in Table 6. A higher Y/B ratio suggests enhanced asymmetry around Dy3+ ionic sites, suggesting enhanced polarizability, higher covalency, and the dominance of the transition of electric dipole in the glass network100,101. The observed trend in the values of the Y/B ratio shows that the maximum asymmetry is achieved at an intermediate doping level (BBBNDy3). Beyond this point (BBBNDy4), a decrease in the Y/B ratio suggests the onset of concentration quenching, which diminishes the effective asymmetry contribution.

The luminescent output of glasses activated by RE ions, particularly Dy3+-doped glasses, is critical for achieving white light emission in solid-state lighting applications. One of the key parameters, the Y/B intensity ratio, indicates the color balance between yellow and blue emissions, excited at a wavelength of 389 nm. An ideal white light is achieved when the Y/B ratio is close to unity3. In the present study, the Y/B values of BBBNDy glasses span from 1.88 to 2.05, indicating a yellow-dominant emission with strong potential for white light generation.

The CIE 1931 chromaticity coordinates (x, y) derived from the emission spectra using the color matching functions are listed in Table 6. These values fall within or near the white light region of the CIE diagram, as shown in Fig. 15, supporting the white light-emitting nature of the BBBNDy glasses. Additionally, the correlated color temperature (CCT) values are computed using McCamy’s empirical formula102, found to range from 3948 to 4192 K for the BBBNDy glasses. The high CCT values, particularly for BBBNDy4, indicate the emission of cool white light, which is ideal for LED lighting applications. Conversely, BBBNDy1, with a higher Y/B ratio and relatively lower CCT, corresponds to warmer white light emissions. Thus, Dy3+-doped BBBNDy glasses with a Y/B ratio nearly equal to one and high CCT values emerge as promising candidates for WLEDs applications, luminescent coatings, table lamps, and indoor lighting solutions86,101.

Properties after gamma irradiation

Following irradiation, the samples BBBNDy0 and BBBNDy3 underwent a brown discoloration that deepened with the dose rate as depicted in Fig. 16. The observed discoloration is ascribed to the creation of color centers formed under radiation exposure and defects such as non-bridging oxygen hole centers (NBOHCs), boron electron centers (BECs), boron oxygen hole centers (BOHCs), and metal ion interstitials103,104,105. NBOHCs typically form from O–H bond radiolysis, where a hole is trapped in NBO. BECs result from unpaired electrons localized on boron atoms, while BOHCs arise from disrupted BO3–BO4 or BO4–BO4 linkages. These defect centers absorb visible light, causing the observed darkening. After the gamma irradiation, the changes in physical, structural, optical, and photoluminescence responses were assessed to determine how these defects influence the glass material behaviour16.

X-ray diffraction analysis

The XRD patterns of BBBNDy0 and BBBNDy3 glasses after exposure to the gamma irradiation doses exhibit negligible changes, confirming the retention of their amorphous nature. However, a slight shift in the broad diffraction band from approximately 27° to 28° suggests the presence of radiation-induced lattice stress. Furthermore, a noticeable band broadening in the 40°–50° range is observed, which is attributed to structural rearrangements within the borate network, particularly modifications in boron coordination units, as illustrated in Fig. 17. Similar observations have been reported in previous studies1,106.

Physical properties

Density and molar volume

The density was measured using Eq. (1) and presented in Table 7 to evaluate the alterations in the glasses after exposure to gamma radiation. From the values observed from Table 7, the density of undoped (BBBNDy0) glasses decreases slightly from 4.4039 g/cm3 for the gamma irradiation dose of 5 and 10 kGy, respectively, likely due to the formation of irradiation induced defects such as electron–hole pairs and the breaking of B–O bonds in BO4 units, leading to glass network loosening, hence structure open up107,108. However, at 15 kGy, the density increased, suggesting a compaction or densification effect due to the rearrangement of the disrupted structural units (BO3 → BO4) under higher irradiation energy109. The density of unirradiated BBBNDy3 is 4.4258 g/cm3, showing a consistent increase in density with increasing dose (5, 10, and 15 kGy) of gamma irradiation. As it alters the boron–oxygen network through the disruption of trivalent bonds and promotes the formation of tetrahedral bonds within the glass matrix, indicating enhanced structural stability and tighter packing facilitated by Dy3+ ions in BBBNDy glasses1, as depicted in Fig. 18.

Average boron–boron distance and oxygen packing density

To evaluate the structural compaction of BBBNDy0 and BBBNDy3 glasses under gamma irradiation, parameters such as \(D_{{\left\langle {B - B} \right\rangle }}\) and OPD were examined. As shown in Fig. 19 and Table 7, BBBNDy0 glasses exhibited an increase in \(D_{{\left\langle {B - B} \right\rangle }}\) and a decrease in OPD values at lower doses, while the opposite trend at 15 kGy suggests structural compaction. In contrast, BBBNDy3 glasses showed a consistent decrease in \(D_{{\left\langle {B - B} \right\rangle }}\) and an increase in OPD with increasing dose of gamma irradiation, implying reduced spacing between boron atoms and enhanced structural packing due to radiation-induced structural rearrangement.

FTIR analysis

Figure 20 presents the FTIR spectra of BBBNDy0 and BBBNDy3 glass samples subjected to 10 kGy of gamma irradiation. A spectral comparison highlights significant structural modifications in the glass network induced by irradiation. Upon irradiation, notable modifications are observed in the intensities and relative areas of vibrational bands corresponding to various borate units, particularly the triangular (BO3) and tetrahedral (BO4) units. These variations stem from the effect of high-energy photon irradiation on the glass matrix, which initiates the electronic excitations, generates electron–hole pairs, and subsequently alters the local structure through defect formation and bond rearrangement110,111.

In BBBNDy0 and BBBNDy3 glasses, after irradiation, FTIR spectra show notable variations in the peak intensity and area associated with vibrations of B–O stretching of BO3 and BO4 units, evident from Fig. 21. Studies from Shafi et al., these variations are attributed to bond breaking, displacements, or knock-on effects caused by high-energy gamma photons112. Additionally, the main absorption bands’ positions remain largely unchanged in either glass sample, implying that the fundamental structural units remain largely intact. However, slight variations in the intensities are observed. These observations support that gamma irradiation does not completely disrupt the glass network but introduces moderate local distortions, indicating the shielding behavior of these glasses as a result of Bi3+ ions within the glass matrix, which prevents extensive defect formation or structural deformation. Numerous researchers113,114,115 have reported similar findings, attributing this shielding effect to the substantial mass of Bi3+ ions, which impede the free movement of electrons released during irradiation, thereby minimizing the creation of defects and ensuring the stability of the structural units.

Optical properties

Figure 22 exhibits clear evidence of radiation-induced optical absorption in BBBNDy0 glass, upon exposure to gamma irradiation dose levels ranging from 5 to 15 kGy. A marked enhanced absorption across the spectra with increasing gamma dose is attributed to the creation of radiation-induced defect centers, such as non-bridging oxygen hole centers (NBOHCs) and boron oxygen hole centers (BOHCs), which introduce localized states within the forbidden band gap of the glass matrix. These defects trap charges, thereby facilitating the absorption process and effectively increasing the total absorption, which shifts the absorption edge towards longer wavelengths97.

In the BBBNDy3 sample, the presence of Dy3+ ions stabilizes the structure and reduces the formation of these defects as described above, leading to a decrease in absorbance116. Thus, the BBBNDy3 sample shows improved structural stability against radiation damage, by healing defects in the glass matrix by repairing the flaws10. No additional peaks were detected following gamma irradiation at doses ranging from 5 to 15 kGy in both BBBNDy0 and BBBNDy3 glasses. However, slight variations in the intensity of existing peaks were observed, suggesting that the glass structure remains largely unaffected and demonstrates good resistance to radiation-induced change.

The optical energy band gap, which is sensitive to changes in bonding environments, reflects structural modifications within the glass network. Hence, optical band gap measurement values after gamma irradiation are helpful. From Figs. 23 and 24, and Table 8, the optical energy band values (direct and indirect) show dose-dependent changes. In BBBNDy0, the direct band gap fluctuates slightly (2.859 eV → 2.771 eV → 2.939 eV) while the indirect band gap also shows a non-monotonic change (2.726 eV → 2.652 eV → 2.806 eV), but in both cases the net effect is a increase at higher dose (15 kGy). These changes can be attributed to the formation of charge distribution defects induced by gamma irradiation, which increases the degree of localization and NBO states, thereby resulting in a narrower band gap11. Additionally, in BBBNDy3 glasses, \(E_{opt}\) increases monotonically with increasing gamma irradiation dose. The direct band gap varies from 2.824 to 2.892 eV, and the indirect band gap from 2.665 to 2.719 eV with the increase in the gamma irradiation dose from 5 to 15 kGy, suggesting the conversion of NBO into BO, contributing to a tighter and more cohesive glass structure, and indicating enhanced structural stability. The healing of intrinsic defects in the glass matrix becomes more prominent, contributing further to the network densification10. Upon gamma irradiation, the samples’ color gradually deepens, likely due to lattice atom displacement or the formation of electronic defects, which can be attributed to valence state modifications in constituent foreign atoms. Gamma rays further enhance the formation of color centers such as NBO. This is evident from the observed color change in the samples with an increasing dose, as shown in Fig. 16.

As presented in Table 8, both BBBNDy0 and BBBNDy3 glasses exhibit an increase in EU values with rising gamma irradiation dose, varying from 0.256 eV → 0.285 eV → 0.247 eV in BBBNDy0 and from 0.298 to 0.288 eV in BBBNDy3. This trend indicates reduced structural disorder and localization of electronic states within the band gap due to irradiation. According to Dow and Redfield117 such band-tailing results from internal disorder, a characteristic feature of amorphous solids. The steepness parameter, which is inversely related to the EU, also reflects this disorder and is listed in Table 8.

As shown in Table 8, the refractive index (n) values of both BBBNDy0 and BBBNDy3 glasses increase with gamma irradiation, aligning with the trends observed in \(E_{opt}\) and density. Metallization criteria (M), remains below 1 across all doses, indicating the glasses maintain their insulating behavior and exhibit structural stability under gamma irradiation. Additionally, the calculated Numerical aperture (NA) values typically fall within the typical range of 0.13–0.5 used for the cores in optical fibers, confirming the suitability of these glasses for optical applications.

As presented in Table 8, the reflection loss (\(R_{L}\)) values for BBBNDy0 remain nearly constant with increasing gamma irradiation, whereas BBBNDy3 show a slight increase, indicating a marginal reduction in back-reflected energy16. The optical transmission (T), values exhibit a slight decrease for both BBBNDy0 and BBBNDy3 glass with increasing gamma irradiation dose, suggesting a gradual decrease in optical transmittance.

Photoluminescence analysis (PL)

The emission spectra of BBBNDy3 glasses subjected to gamma irradiation doses of 5, 10, and 15 kGy (Fig. 25) exhibit four prominent bands corresponding to the Dy3+ ions, as discussed in Sect. 3.1.6.4. Notably, the band shapes and peak positions remain unaltered after irradiation2. However, with increasing radiation dose, a notable decline in the intensity of the emission bands is evident, maintaining the highest intensity for the yellow band, likely due to migration of excitation or emission energy towards the charges trapped/defect centers, modifications in the local coordination environment of Dy3+ ions29,118. From Table 9, elevated Y/B intensity ratio values of the gamma irradiated samples specify that the Dy3+ local environment resides in a lower symmetry site lacking an inversion center, and the Dy–O bond’s strong covalency3.

The CIE 1931 (x,y) chromaticity values extracted from the emission spectra at 389 nm excitation further confirm the impact of gamma exposure. The coordinates, as mentioned in Table 9, fall within the yellowish-white zone of the CIE diagram (Fig. 25). These coordinates exhibit slight shifts towards the yellow region with increasing radiation dose, attributed to the elevated Y/B ratio and narrowing of emission bands. Similar trends are recorded in Dy2O3-doped borosilicate glasses119 and Dy3+, Eu3+ co-doped fluoroaluminoborate glasses3.

Furthermore, the CCT values range between 3401 and 3611 K, corresponding to warm to cool white emissions. These findings demonstrate that 0.6 mol% Dy2O3-doped BBBNDy3 glasses maintain their white light-emitting characteristics after gamma irradiation, highlighting their potential for WLEDs and photonic applications even under radiation-rich environments120.

Summary of key parameters of BBBNDy3 glasses before and after irradiation

To demonstrate the effect of Dy2O3 incorporation and to evaluate the radiation stability of BBBNDy3 glass, the key physical, optical, and luminescence parameters before and after irradiation are summarized in Table 10.

Conclusion

Dy2O3-incorporation enhanced network compactness at 0.4 mol% (BBBNDy2) with the highest density of 4.4743 g/cm3 and molar volume minimizing at cc/mol. Gamma irradiation of BBBNDy0 and BBBNDy3 glasses showed dose-dependent structural reorganization, increasing BO linkages and reducing defects, especially at 15 kGy. The FTIR and Raman analyses confirmed the evidence of functional group vibrations related to BO3, BO4, and BiO3 and BiO6 units, with minimal spectral shifts under doping of Dy2O3 and gamma irradiation, suggesting good structural stability. Optical studies showed a tunable band gap (2.729–2.957 eV) with low Urbach energy (0.175–0.227 eV), confirming the defect tolerance and insulating behavior, while refractive index values (2.409–2.474) correlated well with density. Irradiation-induced variations in Eu values, showed increased disorder at low doses, followed by defect recovery at higher doses. Transmission coefficient and NA values (0.341–0.398) further indicate suitability for fiber core applications, even under the radiation environment. Photoluminescence analysis confirmed a pronounced yellow emission at 575 nm (4F9/2 → 6H13/2), most intense for BBBNDy3 glass, and although irradiation caused up to 87% quenching, the emission band remained observable. Together, these findings demonstrate the dual role of Dy3+ ions by improving glass network stability under irradiation while sustaining efficient luminescence, positioning BBBNDy3 glass a promising candidate for radiation-resistant photonic devices, white-light applications.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Karthika, S. et al. Gamma irradiation-induced changes in the structural, optical, electrical and radiation shielding properties of lithium borate glasses. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 202, 110560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radphyschem.2022.110560 (2023).

Kaur, S., Pandey, O. P., Jayasankar, C. K. & Verma, N. Exploring thermal, optical, structural and luminescent properties of gamma irradiated Dy3+ doped tellurite glasses: Photon shielding properties. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 199, 110375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radphyschem.2022.110375 (2022).

Hari Babu, B. & Ravi Kanth Kumar, V. V. Photoluminescence properties and energy transfer in γ-irradiated Dy3+, Eu3+-codoped fluoroaluminoborate glasses. J. Mater. Sci. 49, 7959–7969. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-014-8486-7 (2014).

Ruamnikhom, R., Yasaka, P. & Kaewkhao, J. Physical and optical properties of Dy3+ bismuth barium borate glasses. J. Thai Interdiscip. Res. 12, 1–4 (2017).

Taha, E. O. & Saeed, A. The effect of cobalt/copper ions on the structural, thermal, optical, and emission properties of erbium zinc lead borate glasses. Sci. Rep. 13, 12260. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-39256-6 (2023).

Helmy, A. K. et al. Influence of vanadium oxide on the structural, optical, mechanical and dielectric properties of cadmium borate glasses. Sci. Rep. 15, 27430. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09064-1 (2025).

Naseer, K. A., Marimuthu, K., Al-Buriahi, M. S., Alalawi, A. & Tekin, H. O. Influence of Bi2O3 concentration on barium-telluro-borate glasses: Physical, structural and radiation-shielding properties. Ceram. Int. 47, 329–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.08.138 (2021).

Saber, I. et al. Impact of barium oxide on the structural, thermal, and chemical properties of bismuth borate glasses for optical and thermal applications. Ceram. Int. 51, 7775–7789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.12.215 (2024).

Taj, S. M., Devaraja, C. & Deka, U. A review of boron oxide glasses infused with individual oxides of lanthanide elements: For their physical, structural, optical, and gamma shielding properties. J. Alloys Compd. 1010, 178279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2024.178279 (2025).

Sallam, O. I., Rammah, Y. S., Nabil, I. M. & El-Seidy, A. M. A. Enhanced optical and structural traits of irradiated lead borate glasses via Ce3+ and Dy3+ ions with studying radiation shielding performance. Sci. Rep. 14, 24478. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73892-w (2024).

Marzouk, M. A. Optical characterization of some rare earth ions doped bismuth borate glasses and effect of gamma irradiation. J. Mol. Struct. 1019, 80–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2012.03.041 (2012).

Mohaymen Taha, T. A. et al. Melt-quenched zinc sodium borate glasses: Understanding the role of ZnO/Na2O ratio in density, band gap, and radiation attenuation. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 222, 111791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radphyschem.2024.111791 (2024).

Ibrahim, A., Farag, M. A. & Sadeq, M. S. Towards highly transparent tungsten zinc sodium borate glasses for radiation shielding purposes. Ceram. Int. 48, 12079–12090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.01.068 (2022).

Aqeel, N., Hassan, A. K., Moustafa, Y. M. & El-, D. G. Role of CsBr in structure and properties of new cesium bromo-borate glasses. Ceram. Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.08.485 (2024).

Al-Baradi, A. M., El-Rehim, A. F. A., Alrowaili, Z. A., Al-Buriahi, M. S. & Shaaban, K. S. FT-IR and gamma shielding characteristics of 22SiO2–23Bi2O3–37B2O3–13TiO2-(5−x) LiF-xBaO glasses. SILICON 14, 7043–7051. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12633-021-01481-x (2022).

Alshamari, A. et al. Gamma-ray-induced changes in the radiation shielding, structural, mechanical, and optical properties of borate, tellurite, and borotellurite glass systems modified with barium and bismuth oxide. Optik (Stuttg) 281, 170829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijleo.2023.170829 (2023).

Shaaban, K. S., Al-Baradi, A. M. & Ali, A. M. Investigation of BaO reinforced TiO2–P2O5–Li2O glasses for optical and neutron shielding applications. RSC Adv. 12, 3036–3043. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2ra00171c (2022).

Boonin, K. et al. Effect of BaO on lead free zinc barium tellurite glass for radiation shielding materials in nuclear application. J. Non Cryst. Solids 550, 120386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2020.120386 (2020).

Kilic, G. et al. Ta2O5 reinforced Bi2O3–TeO2–ZnO glasses: Fabrication, physical, structural characterization, and radiation shielding efficacy. Opt. Mater. (Amst.) 112, 110757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2020.110757 (2021).

Ba, K., Chahine, A., Ebn Touhami, M., Jermoumi, T. & Shaim, A. Elaboration and characterization of new glasses with high chemical durability in the system (70−x)TiO2–xNiO–30P2O5. Mater. Res. Innov. 26, 100–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/14328917.2021.1885578 (2022).

Sayyed, M. I., Tekin, H. O. & Agar, O. Gamma photon and neutron attenuation properties of MgO–BaO–B2O3–TeO2–Cr2O3 glasses: The role of TeO2. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 163, 58–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radphyschem.2019.05.012 (2019).

Sayyed, M. I. et al. Evaluation of gamma-ray and neutron shielding features of heavy metals doped Bi2O3–BaO–Na2O–MgO–B2O3 glass systems. Prog. Nucl. Energy 118, 103118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnucene.2019.103118 (2020).

Pavai, R. E. & Dharsini, P. S. P. Effect of Na2O on structural and thermal properties of cadmium borate glasses. IOSR J. Appl. Phys. 09, 67–70. https://doi.org/10.9790/4861-0903026770 (2017).

Tijaria, M., Sharma, Y., Kumar, V., Dahiya, S. & Dalal, J. Effect of Na2O on physical, structural and electrical properties of borate glasses. Mater. Today Proc. 45, 3722–3725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.12.688 (2020).

El-Daly, A. A., Abdo, M. A., Bakr, H. A. & Sadeq, M. S. Impact of cobalt ions on the phonon energy and ligand field parameters of some borate glasses. J. Non Cryst. Solids 555, 120535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2020.120535 (2021).

Farouk, M., Samir, A., Ibrahim, A., Farag, M. A. & Solieman, A. Raman, FTIR studies and optical absorption of zinc borate glasses containing WO3. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 126, 696. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-020-03890-y (2020).

Kaur, P., Kaur, S., Singh, G. P. & Singh, D. P. Cerium and samarium codoped lithium aluminoborate glasses for white light emitting devices. J. Alloys Compd. 588, 394–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2013.10.181 (2014).

Liu, S., Zhao, G., Ying, H., Wang, J. & Han, G. Eu/Dy ions co-doped white light luminescence zinc-aluminoborosilicate glasses for white LED. Opt. Mater. (Amst.) 31, 47–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2008.01.007 (2008).

Kesavulu, C. R. & Jayasankar, C. K. White light emission in Dy3+-doped lead fluorophosphate glasses. Mater. Chem. Phys. 130, 1078–1085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2011.08.037 (2011).

Wu, L. et al. Luminescence and energy transfer of a color tunable phosphor: Dy3+-, Tm3+-, and Eu3+-coactivated KSr 4(BO3)3 for warm white UV LEDs. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 6463–6470. https://doi.org/10.1039/c2jm15506k (2012).

Zhu, G., Ci, Z., Xin, S., Wen, Y. & Wang, Y. Warm white light generation from Dy3+ doped NaSr2Nb5O15 for white LEDs. Mater. Lett. 91, 304–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2012.09.072 (2013).

Babu, A. M., Jamalaiah, B. C., Kumar, J. S., Sasikala, T. & Moorthy, L. R. Spectroscopic and photoluminescence properties of Dy3+-doped lead tungsten tellurite glasses for laser materials. J. Alloys Compd. 509, 457–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2010.09.0582 (2011).

Jayasimhadri, M. et al. Optical properties of Dy3+ ions in alkali tellurofluorophosphate glasses for laser materials. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 39, 635. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/39/4/007 (2006).

Reddy, A. A., Sekhar, M. C., Pradeesh, K., Babu, S. S. & Prakash, G. V. Optical properties of Dy3+-doped sodium–aluminum–phosphate glasses. J. Mater. Sci. 46, 2018–2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-010-4851-3 (2011).

Dwivedi, Y., Thakur, S. N. & Rai, S. B. Study of frequency upconversion in Yb3+/Eu3+ by cooperative energy transfer in oxyfluoroborate glass matrix. Appl. Phys. B 89, 45–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00340-007-2747-y (2007).

Elbatal, H. A., Abdelghany, A. M., Ghoneim, N. A. & Elbatal, F. H. Effect of 3d-transition metal doping on the shielding behavior of barium borate glasses: A spectroscopic study. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 133, 534–541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2014.06.044 (2014).

Marzouk, M. A. & Ghoneim, N. A. Gamma irradiation and crystallization effects on the photoluminescence properties of soda lime fluorophosphates host glass activated with Ce4+, Dy3+ or Pr3+ ions. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 174, 108893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radphyschem.2020.108893 (2020).

Hegde, V. et al. Effects of high dose gamma irradiation on the optical properties of Eu3+ doped zinc sodium bismuth borate glasses for red LEDs. J. Lumin. 207, 288–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlumin.2018.11.023 (2019).

Berwal, N. et al. Physical, structural and optical characterization of silicate modified bismuth-borate-tellurite glasses. J. Mol. Struct. 1127, 636–644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2016.08.033 (2017).

Shiva Kumar, B. N. et al. Implications of silver nitrate doping on the physical, structural, and optical attributes of Na2O−ZnO−Borate glasses. J. Mol. Struct. 1325, 140985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2024.140985 (2025).

Vinay, D. et al. Silver oxide embedded alkali zinc boro tellurite glasses: Physical, structural and optical properties for possible optical switching applications. J. Mol. Struct. 1339, 142388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2025.142388 (2025).

Usman, A., Halimah, M. K., Latif, A. A., Muhammad, F. D. & Abubakar, A. I. Influence of Ho3+ ions on structural and optical properties of zinc borotellurite glass system. J. Non Cryst. Solids 483, 18–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2017.12.040 (2018).

Vinay, D. et al. Investigation of physical, structural, optical, and luminescence properties of nickel oxide doped alkali zinco-borate glasses. Sci. Rep. 15, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91852-w (2025).

Gowda, G. V. J., Reddy, G. V. A., Eraiah, B. & Devaraja, C. R. Investigations of structural modifications, physical and optical properties of lead boro-tellurite glasses doped with europium trioxide for possible optical switching applications. J. Met. Mater. Miner. 33, 65–74. https://doi.org/10.55713/jmmm.v33i2.1610 (2023).

Devaraja, C., Gowda, G. V. J., Eraiah, B. & Keshavamurthy, K. Optical properties of bismuth tellurite glasses doped with holmium oxide. Ceram. Int 47, 7602–7607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.11.099 (2021).

Farag, H. K. & Marzouk, M. A. Preparation and characterization of nanostructured nickel oxide and its influence on the optical properties of sodium zinc borate glasses. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 28, 15480–15487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-017-7435-z (2017).

Abdel Wahab, E. A. & Shaaban, K. S. Structural and optical features of aluminum lead borate glass doped with Fe2O3. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 127, 956. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-021-05062-y (2021).

Umar, S. A., Halimah, M. K., Chan, K. T. & Latif, A. A. Polarizability, optical basicity and electric susceptibility of Er3+ doped silicate borotellurite glasses. J. Non Cryst. Solids 471, 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2017.05.018 (2017).

Abdel-Baki, M., Mostafa, A. M., Fayad, A. M., El-Bassyouni, G. T. & Turky, G. M. Improving the optical, electrical, and dielectric characteristics of MgO doped borate glass for optoelectronic applications. J. Appl. Phys. 133, 065102. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0136730 (2023).

Roopa, E. B. Experimental and theoretical approach on the physical, structural and optical properties of ZrO2–Na2O–B2O3 glasses doped with Dy2O3. J. Non Cryst. Solids 551, 120394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2020.120394 (2021).

Sayyed, M. I. et al. The influence of MgO on the physical, structural, mechanical, optical, and radiation absorption properties of the boro-germanate glass system. Ceram. Int. 50, 33618–33629. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CERAMINT.2024.06.178 (2024).

Chou, J. W., Skornicki, M. & Cohen, J. T. Unintended consequences of the potential phase-out of gamma irradiation. F1000Res 7, 348. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.14090.1 (2018).

Patwari, D. R. & Eraiah, B. Enhanced luminescence of silver nano-particles doped Na2O-BaO-borate glasses. J. Mater. Appl. 9, 107–119. https://doi.org/10.32732/jma.2020.9.2.107 (2020).

Devaraja, C. et al. Physical, structural and photo luminescence properties of lead boro-tellurite glasses doped with Eu3+ ions. Vacuum 177, 109426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vacuum.2020.109426 (2020).

Ghazy, A. R. et al. Structural, optical, and cytotoxicity studies of laser irradiated ZnO doped borate bioactive glasses. Sci. Rep. 13, 7292. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34458-4 (2023).

Keshavamurthy, K. et al. Low concentration Sm3+ ions loaded zinc sodium borate glasses for solid state lighting devices. Opt. Mater. (Amst.) 148, 114829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2024.114829 (2024).

Lomon, J. et al. Nickel and manganese on lithium borate glass cathode for energy storage materials. Materialia (Oxford) 26, 101583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtla.2022.101583 (2022).

Parandamaiah, M., Kumar, K. N., Babu, S., Reddy, S. V. & Ratnakaram, Y. C. Dy3+ doped lithium sodium bismuth borate glasses for yellow luminescent photonic applications. J. Eng. Res. Appl. 5, 126–131 (2015).

Narwal, P., Dahiya, M. S., Agarwal, A., Hooda, A. & Khasa, S. Compositional dependence of white light emission in Dy3+ doped NaCl−BaO bismuth borate glasses. J. Lumin. 209, 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlumin.2019.01.042 (2019).

ElBatal, F. H., Marzouk, S. Y., Nada, N. & Desouky, S. M. Gamma-ray interaction with copper-doped bismuth-borate glasses. Physica B Condens. Matter 391, 88–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physb.2006.09.001 (2007).

El Batal, F. H., Marzouk, S. Y., Nada, N. & Desouky, S. A. Optical properties of vanadium-doped bismuth borate glasses before and after gamma-ray irradiation. Philos. Mag. 90, 675–697. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786430903222974 (2010).

Farouk, M., Ahmad, F. & Samir, A. Ligand field and spectroscopic investigations of cobalt doped erbium–zinc borate glasses. Opt. Quantum Electron. 51, 292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11082-019-2009-3 (2019).

Haritha, L. et al. Effect of metal fluorides on chromium ions doped bismuth borate glasses for optical applications. Chin. Phys. B 28, 038101. https://doi.org/10.1088/1674-1056/28/3/038101 (2019).

Kaur, P., Singh, K. J., Thakur, S., Kurudirek, M. & Rafiei, M. M. Structural investigations and nuclear radiation shielding ability of bismuth lithium antimony borate glasses. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 150, 109812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpcs.2020.109812 (2021).

Karthikeyan, B. & Mohan, S. Structural, optical and glass transition studies on Nd3+-doped lead bismuth borate glasses. Physica B Condens. Matter 334, 298–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-4526(03)00080-2 (2003).

Pascuta, P., Pop, L., Rada, S., Bosca, M. & Culea, E. The local structure of bismuth borate glasses doped with europium ions evidenced by FT-IR spectroscopy. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 19, 424–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-007-9359-5 (2008).

Karthikeyan, B., Philip, R. & Mohan, S. Optical and non-linear optical properties of Nd3+-doped heavy metal borate glasses. Opt. Commun. 246, 153–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optcom.2004.10.051 (2005).

Abo-Naf, S. M. FTIR and UV-VIS optical absorption spectra of gamma-irradiated MoO3-doped lead borate glasses. J. Non Cryst. Solids 358, 406–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2011.10.013 (2012).

Saddeek, Y. B. & Gaafar, M. S. Physical and structural properties of some bismuth borate glasses. Mater. Chem. Phys. 115, 280–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2008.12.004 (2009).

Maalegoundla, C., Sekhar, K. C., Hameed, A., Srinivas, B. & Shareefuddin, M. Physical and spectroscopic studies of CaF2–Al2O3–Bi2O3–B2O3–CuO glasses. J. Aust. Ceram. Soc. 58, 1137–1146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41779-022-00737-y (2022).

Maan, D., Nain, D. & Meenakshi,. Investigating structure and physical properties of chromium oxide doped bismuth borate glasses. Indian J. Pure Appl. Phys. 62, 429–440. https://doi.org/10.56042/ijpap.v62i6.8667 (2024).

Limkitjaroenporn, P., Kaewkhao, J., Limsuwan, P. & Chewpraditkul, W. Physical, optical, structural and gamma-ray shielding properties of lead sodium borate glasses. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 72, 245–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpcs.2011.01.007 (2011).

Nain, D., Maan, D., Ahlawat, J. & Meenakshi,. Physical and structural properties of yttrium dopped multicomponent bismuth silicate glasses. SILICON 16, 2205–2218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12633-023-02832-6 (2024).

Pascuta, P., Borodi, G. & Culea, E. Influence of europium ions on structure and crystallization properties of bismuth borate glasses and glass ceramics. J. Non Cryst. Solids 354, 5475–5479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2008.09.010 (2008).

Simon, V., Spinu, M. & Stefan, R. Structure and dissolution investigation of calcium-bismuth-borate glasses and vitroceramics containing silver. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 18, 507–512. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10856-007-2011-3 (2007).

Baia, L., Stefan, R., Popp, J., Simon, S. & Kiefer, W. Vibrational spectroscopy of highly iron doped B2O3–Bi2O3 glass systems. J. Non Cryst. Solids 324, 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3093(03)00227-8 (2003).

Abid, M. et al. Structure–properties study of sodium bismuth borate glasses. Moroc. J. Chem. 11, 566–578 (2023).

Lan, S. H., Lee, C. T., Lai, Y. S., Chen, C. C. & Yang, H. W. The relationship between the structure and thermal properties of Bi2O3–ZnO–B2O3 glass system. Adv. Condens. Matter Phys. 2021, 2321558. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/2321558 (2021).

Vikas, Dahiya, M. S., Hooda, A. & Khasa, S. Structural analysis of mixed transition metal ion doped barium-boro-bismuthate glass system. J. Mol. Struct. 1264, 133291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2022.133291 (2022).

Ardelean, I., Cora, S. & Ioncu, V. Structural investigation of CuO–Bi2O3–B2O3 glasses by FT-IR, Raman and UV–VIS spectroscopies. J. Optoelectron. Adv. Mater. 8, 1843–1847 (2006).

Kaur, P., Singh, K. J., Kurudirek, M. & Thakur, S. Study of environment friendly bismuth incorporated lithium borate glass system for structural, gamma-ray and fast neutron shielding properties. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 223, 117309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2019.117309 (2019).

Madhu, A., Eraiah, B. & Srinatha, N. Gamma irradiation effects on the structural, thermal and optical properties of samarium doped lanthanum–lead-boro-tellurite glasses. J. Lumin. 221, 117080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlumin.2020.117080 (2020).

Bala, M. et al. Effect of replacement of Bi2O3 by Li2O on structural, thermal, optical and other physical properties of zinc borate glasses. J. Mol. Struct. 1219, 128589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.128589 (2020).

Kundu, R. S., Dhankhar, S., Punia, R., Nanda, K. & Kishore, N. Bismuth modified physical, structural and optical properties of mid-IR transparent zinc boro-tellurite glasses. J. Alloys Compd. 587, 66–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2013.10.141 (2014).

Seshadri, M. et al. Near-infrared quantum cutting luminescence in Pr3+/Yb3+ doped lead bismuth borate glass. Sci. Rep. 12, 19311. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-23808-3 (2022).

Manjeet, et al. Structural, thermal, optical and luminescence properties of Dy3+ ions doped zinc potassium alumino borate glasses for optoelectronics applications. J. Non Cryst. Solids 588, 121613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2022.121613 (2022).

Pravallika, C. et al. Structural investigation and optical properties of dysprosium (Dy3+) ions doped oxyfluoro antimony borate glasses for photonics applications. J. Fluoresc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10895-023-03553-0 (2023).

Carnall, W. T., Fields, P. R. & Rajnak, K. Electronic energy levels in the trivalent lanthanide aquo ions. I. Pr3+, Nd3+, Pm3+, Sm3+, Dy3+, Ho3+, Er3+, and Tm3+. J. Chem. Phys. 49, 4424–4442. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1669893 (1968).

Thulasiramudu, A. & Buddhudu, S. Optical characterization of Sm3+ and Dy3+:ZnO–PbO–B2O3 glasses. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 67, 802–8074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2006.08.036 (2007).

Jørgensen, C. K. & Judd, B. R. Hypersensitive pseudoquadrupole transitions in lanthanides. Mol. Phys. 8, 281–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/00268976400100321 (1964).

Liu, R. et al. Luminescence, energy transfer properties of Dy3+/Eu3+ coactivated neutral and warm white emissions GSBG glasses. J. Lumin. 237, 118180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlumin.2021.118180 (2021).

Liu, R. et al. Luminescent properties and structure of Dy3+ doped germanosilicate glass. J. Lumin. 226, 117378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlumin.2020.117378 (2020).

Urbach, F. The long-wavelength edge of photographic sensitivity and of the electronic absorption of solids[8]. Phys. Rev. 92, 1324. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.92.1324 (1953).

Narwal, P. et al. Dy3+ doped LiCl–CaO–Bi2O3–B2O3 glasses for WLED applications. Ceram. Int. 43, 1324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.05.160 (2017).

Sangeetha, G., Chandra Sekhar, K., Narasimha Chary, M. & Shareefuddin, M. Influence of magnesium oxide on the physical and spectroscopic properties of manganese doped sodium tetra borate glasses. Optik (Stuttg) 259, 168952. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJLEO.2022.168952 (2022).

Zaman, F. et al. Comparative study of Dy3+ doped borate glasses on the basis of luminescence and lasing properties for white-light generation. Opt. Mater. (Amst) 119, 111308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2021.111308 (2021).

Thabit, H. A., Jagannath, G., Hashim, S. & Sayyed, M. I. Physical, optical and spectroscopic characteristics investigation for doped Dy3+ borate glass matrix. J. Non Cryst. Solids 608, 122258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2023.122258 (2023).

Suresh, A. A., Murugasen, P. & Dhavamurthy, M. Luminescence properties of Tm3+/Dy3+ co-activated borate and borophosphate glasses for near daylight w-LED and dosimetry application. Emergent. Mater. 7, 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42247-023-00595-9 (2024).

Deopa, N. & Rao, A. S. Photoluminescence and energy transfer studies of Dy3+ ions doped lithium lead alumino borate glasses for w-LED and laser applications. J. Lumin. 192, 832–841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlumin.2017.07.052 (2017).

Seeta Rama Raju, G. et al. Synthesis and luminescent properties of Dy3+:GAG nanophosphors. J. Alloys Compd. 481, 832–841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2009.03.095 (2009).

Zaman, F. et al. Investigation of luminescence and lasing properties of Dy3+-doped-borate glasses for white light generation. Solid State Sci. 90, 68–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2019.02.006 (2019).

McCamy, C. S. Correlated color temperature as an explicit function of chromaticity coordinates. Color Res. Appl. 17, 142–144. https://doi.org/10.1002/col.5080170211 (1992).

Rao, G. V., Reddy, P. Y. & Veeraiah, N. Thermoluminescence studies on Li2O–CaF2–B2O3 glasses doped with manganese ions. Mater. Lett. 57, 403–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-577X(02)00800-5 (2002).

El-Batal, H. A., Azooz, M. A., Ezz-El-Din, F. M. & El-Alaily, N. A. Interaction of gamma rays with calcium aluminoborate glasses containing holmium or erbium. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 84, 2065–2072. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1151-2916.2001.tb00959.x (2001).

Liu, Y. et al. Femtosecond laser induced coordination transformation and migration of ions in sodium borate glasses. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 121113. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2903710 (2008).

El-Alaily, N. A., Sallam, O. I. & Ezz-Eldin, F. M. Effect of gamma irradiation on some spectroscopic properties of phosphate glass containing samarium ions. J. Non Cryst. Solids 523, 119604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2019.119604 (2019).

Ezz El-Din, F. M., El-Alaily, N. A. & El-Batal, H. A. Density and refractive index of some γ-irradiated alkali silicate glasses. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 163, 267–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02034800 (1992).

Ezz-Eldin, F. M., Kashif, I. & El-Batal, H. A. Some physical properties of gamma-irradiated alkali-silicate glasses. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 44, 39–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/0969-806X(94)90100-7 (1994).

El-Alaily, N. A. & Mohamed, R. M. Effect of irradiation on some optical properties and density of lithium borate glass. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 98, 193–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-5107(02)00587-1 (2003).

Eberhard, J. E. NJK and RH. In Progress in Ceramic Science, vol. 4. 1st edn. (Pergamon Press, 1996).

Ruller, J. A. & Friebele, E. J. The effect of gamma-irradiation on the density of various types of silica. J. Non Cryst. Solids 136, 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3093(91)90131-O (1991).

Shafi, N. A., El Batal, H. A., El Din, F. M. E., Gharib, S. & Halawa, M. M. Thermal conductivity of gamma-irradiated ternary borate glasses. Thermochim. Acta 96, 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-6031(85)80014-9 (1985).

El Batal, H. A., Abou Hussein, E. M., El Alaily, N. A. & EzzEldin, F. M. Effect of different 3d transition metal oxides on some physical properties of γ-Irradiated Bi2O3–B2O3 glasses: A comparative study. J. Non Cryst. Solids 528, 119733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2019.119733 (2020).

Kaur, R., Singh, S. & Pandey, O. P. FTIR structural investigation of gamma irradiated BaO-Na2O–B2O3–SiO2 glasses. Physica B Condens. Matter 407, 4765–4769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physb.2012.08.031 (2012).

Singh, D., Thind, K. S., Mudahar, G. S. & Bajwa, B. S. Optical absorption and infrared spectroscopic analysis of γ-irradiated ZnO–BaO–B2O3 glasses. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 268, 3340–3343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2010.07.007 (2010).

Toumi, S., Farah, K. & Adawy, A. Embedding crystalline Cu and Cu2O nanoparticles in silicate glasses through an ion-exchange process followed by gamma irradiation and annealing: An optical absorption spectroscopy assessment. CrystEngComm https://doi.org/10.1039/d4ce01225a (2025).

Marzouk, S. Y., Elalaily, N. A., Ezz-Eldin, F. M. & Abd-Allah, W. M. Optical absorption of gamma-irradiated lithium-borate glasses doped with different transition metal oxides. Physica B Condens. Matter 382, 340–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physb.2006.03.014 (2006).

Rao, M. S. et al. De-quenching influence of aluminum ions on Y/B ratio of Dy3+ ions in lead silicate glass matrix. J. Alloys Compd. 575, 375–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2013.05.098 (2013).

Selim, Y., Sallam, O. I. & Elalaily, N. A. Investigation of some optical, conducting and radiation shielding properties of Dy3+ ions doped boro-silicate glass systems. Ceram. Int. 50, 13336–13346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.01.2464 (2024).

Hari Babu, B. & Ravi Kanth Kumar, V. V. Photoluminescence and color tunability of γ-irradiated Tb3+–Sm3+-codoped oxyfluoride aluminoborate glasses. J. Mater. Sci. 49, 415–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-013-7720-z (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank and acknowledge Manipal Institute of Technology Bengaluru, and Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, for their great encouragement and support towards research. Authors express thanks to the Centre for Nano and Soft Matter Sciences (CeNS), Bengaluru, for providing Raman Spectroscopy characterizations.

Funding