Abstract

This paper proposes a novel distributed attack detection framework for large-scale systems (LSSs), with a specific focus on low-voltage direct current microgrids (DC MGs). The architecture integrates two complementary detection modules: an event-triggered (ET) observer for local subsystem monitoring and a set of distributed unknown input (UI) observers for assessing the states of neighboring subsystems. To enhance robustness against disturbances, an adaptive compensation mechanism is incorporated. The framework supports an ET control strategy designed to ensure consensus performance, prevent Zeno behavior, and reduce communication overhead. Additionally, a fault detection method based on the state observer is introduced to identify faults within subsystems in real time. The proposed detection method is validated through detailed simulations that consider process noise, model uncertainties, and multiple attack scenarios, including false data injection, stealth, and replay attacks. Results demonstrate that the integrated detection units significantly improve resilience by identifying attacks that would otherwise remain undetected by standalone modules. The study assumes ideal communication links and bounded model uncertainties. Future work aims to address non-ideal communication conditions, investigate time-varying topologies, and develop autonomous reconfiguration strategies based on plug-and-play control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Motivation

With the growing deployment of DC MGs in modern energy systems, ensuring their secure and reliable operation has become increasingly vital. These systems, characterized by decentralized control structures and extensive interconnectivity among distributed generation units (DGUs)1, are particularly vulnerable to cyber-attacks (CAs) that may compromise the stability and performance of the entire microgrid. The integration of communication networks into control architectures introduces new entry points for malicious interference, making cybersecurity a critical concern in the operation of LSSs, especially those relying on cooperative decision-making through information exchange2.

Among various cyber threats, false data injection attacks (FDIAs)3 and stealthy intrusions present considerable challenges due to their ability to subtly alter system behavior while evading detection. The development of effective detection mechanisms that can identify these sophisticated attacks in real-time and with minimal communication overhead is an urgent need. Moreover, external disturbances and faults that naturally occur in power systems further complicate the task of distinguishing malicious activities from benign anomalies4.

To address these challenges, this study introduces a novel distributed fault and attack detection architecture specifically designed for low-voltage islanded DC MGs. By employing a dual-module framework comprising an ET local observer and a set of distributed UI estimators the proposed strategy enables the accurate monitoring of both local and neighboring subsystems. This layered detection mechanism is particularly suited for identifying a wide range of cyber threats, including those that are typically undetectable by conventional single-module schemes.

Furthermore, the framework incorporates adaptive compensation for disturbances and leverages event-triggered communication to reduce unnecessary data exchange, thereby enhancing scalability and resource efficiency. A dedicated fault detection (FD) module based on observer residuals is also developed to ensure prompt identification of system faults. Simulation results based on realistic DC MG models validate the efficacy and robustness of the proposed approach under various attack and fault scenarios.

In light of the increasing complexity of energy networks and the evolving nature of cyber threats, this work represents a significant step toward resilient and intelligent monitoring solutions for critical infrastructure. Future developments will aim to extend the proposed strategy to networks with non-ideal communication conditions, dynamic topologies, and adaptive control requirements.

Literature review

The increasing digitization and decentralization of power systems, particularly in low-voltage DC microgrids (MGs)5, has led to the emergence of new security and stability challenges. Modern DC MGs rely heavily on distributed control strategies to coordinate DGUs, manage load sharing, and ensure voltage regulation. This reliance on inter-device communication introduces vulnerabilities to CAs, such as FDIAs, replay attacks, and stealthy intrusions, which can compromise system integrity and degrade performance without triggering traditional alarms6.

In response to these threats, a wide range of detection strategies have been explored. Centralized methods, though effective in some scenarios, often suffer from scalability limitations, high communication overhead, and a single point of failure. Consequently, research has shifted towards distributed detection mechanisms that align more naturally with the modular structure of MGs and offer improved fault tolerance and resilience7,8,9.

Early studies on cyber-attack detection in DC microgrids leveraged hierarchical control structures and unknown input observers (UIOs) to estimate system states and identify anomalies.10 demonstrated a UIO-based detection mechanism capable of identifying false data injection attacks (FDIAs), but highlighted the vulnerability to zero-trace stealth attacks, prompting the development of dynamic average consensus estimators to strengthen detection capabilities.

Kalman-filter-based UIO schemes have also been investigated11,12,13. Paper14 designed a robust cyber-attack detection algorithm for DC microgrids using Kalman filters integrated with UIOs, achieving high detection accuracy, especially for FDIAs, in realistic operating conditions.

While Observer-based approaches, particularly Unknown Input Observers (UIOs)15, are well-established for decoupling disturbances in state estimation, their application in distributed, resource-constrained settings like DC microgrids remains limited. Existing UIO frameworks often assume continuous communication16,17,18,19 and are not co-designed with event-triggered mechanisms to mitigate the impact of cyber-attacks on the triggering function itself. This work bridges this gap by developing a distributed ET-UI estimator that jointly estimates states and unknown inputs under a novel, attack-resilient event-triggering protocol.

ET strategies in microgrids aim to reduce communication overhead while retaining control performance20. Zhang21 proposed a publish subscribe ET framework using Kalman consensus filters, significantly reducing unnecessary data exchange. Habibi et al.22 Ghazaani et al.23 formulated a distributed ET control strategy for current sharing in DC microgrids, demonstrating Zeno-free performance under resilience requirements. Negahdar et al.24 further extended ET secondary control by introducing adaptive thresholds in directed communication topologies.

FD in microgrids often employs fuzzy logic or interval observers to identify faults under network disturbances or cyber threats25. Jin et al.26 introduced an interval observer with adaptive ET for fault diagnosis in cyber-physical DC microgrids, ensuring rapid detection with zero-threshold residuals. Additionally, study27 proposed a finite-frequency fuzzy-based ET fault detection method capable of handling Denial-of-Service (DoS) attacks, balancing detection sensitivity with communication efficiency.

Robust estimation under unknown inputs and stochastic attack models has been a pivotal research focus. Zhou et al.28, Gong et al.29 and Gong et al.30 introduced dynamic state estimation techniques to handle unknown inputs and cyber-attacks within power grids, laying foundational groundwork for robust observer design. Recent16 combined ET mechanisms with state estimation and fault-reconstruction methods, showcasing efficient ET-based UIOs that maintain system performance against false injections and actuator faults.

Recent works have investigated ET estimation and control mechanisms to improve resource efficiency in networked control systems31. These mechanisms reduce the need for continuous communication by transmitting data only when certain error thresholds are violated7,8,9,10,11. Although effective in reducing bandwidth usage, many existing ET methods rely on fixed thresholds or require global state information, making them less robust to cyber-attacks and less applicable in distributed environments32,33.

Efforts to integrate ET strategies with attack detection are relatively recent. Some studies have employed ET-based observers34,35,36 for fault diagnosis14, while others have introduced ET-triggered UIOs to manage communication in distributed networks15. However, few of these frameworks37 address simultaneous estimation of unknown inputs and system states under intermittent cyber-attacks38, and even fewer are tailored to the specific operational dynamics of low-voltage DC MGs.

Moreover, most prior work assumes static39 or undirected communication topologies40, which do not reflect the complexity of real-world MGs where communication is often dynamic41, directed, and affected by environmental disturbances42. The majority of studies also overlook the implications of limited attacker resources, which is a practical constraint in real-world scenarios. Modeling CAs using stochastic processes such as Bernoulli distributions, as done in more recent works43, provides a more realistic framework for designing robust detection systems.

Recent research on cyber-security in DC microgrids (MGs) has explored approaches based on centralized monitoring, distributed observers, and Kalman-type filters. Prior works either (i) employ Unknown Input Observers (UIOs) to decouple disturbances from estimation errors, or (ii) adopt nonlinear/unscented/cubature Kalman filters for robust state estimation in presence of process noise, or (iii) use event-triggered mechanisms to reduce communication load. However, few studies combine distributed UIOs, Cubature Kalman Filtering (CKF), and dynamic event-triggering in a unified framework that simultaneously addresses stealthy cyber-attacks, unknown inputs (e.g., loads, unmodeled dynamics), and communication-efficiency constraints. This gap motivates the current study.

This study builds upon and extends the existing literature by proposing a composite detection architecture comprising an ET-based state observer and a bank of distributed UIOs. The proposed method addresses key limitations in prior work by enabling both state and unknown input estimation, employing adaptive disturbance compensation, and integrating a dynamic ET mechanism that is robust to cyber-attacks. The use of residual analysis for both fault and attack detection under bounded uncertainties ensures improved reliability and scalability.

The comparative analysis provided in Table 1 delivers a comprehensive overview of the advantages and disadvantages of the different methods explored in the literature.

Research gaps and contributions

Despite significant progress in the fields of distributed control and cyber-attack detection for low-voltage DC MGs, several critical challenges remain unresolved. Most existing detection frameworks assume ideal communication conditions, such as negligible delays, uninterrupted connectivity, and attack-free transmission links. In reality, however, the communication infrastructure is often a major vulnerability, subject to a wide range of cyber threats, particularly in distributed LSSs.

Furthermore, although ET control has been explored as a method to reduce communication overhead, its integration with robust cyber-attack detection especially under bounded disturbances and unknown inputs has not been fully realized. Prior approaches either treat faults and cyber-attacks as equivalent, overlook the finite energy constraints of attackers, or fail to ensure resilience against stealthy and replay attacks. Additionally, many studies rely on fixed ET thresholds or centralized architectures, which limit scalability and fail to account for dynamic system behaviors under attack conditions.

This paper addresses these limitations by proposing a distributed, dual-module fault and cyber-attack detection architecture for LSSs and DC MGs, specifically designed to function under realistic constraints including bounded disturbances, limited attacker resources, and dynamic event-triggered communication. The key contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

-

Hybrid ET–UIO–CKF Design: A distributed two-layer detection framework is proposed, combining an ET observer for local subsystem monitoring with a bank of distributed UIOs that integrate CKF principles for global estimation under stochastic noise.

-

Dynamic Event-Triggered Mechanism: A novel dynamic event-triggering condition is developed to reduce communication load while avoiding Zeno behavior and maintaining estimation stability under bounded disturbances.

-

Robust Estimation under Attacks and Faults: The proposed framework effectively detects stealthy cyber-attacks, false data injection, and sensor/actuator faults in real time, providing resilience against unknown inputs and communication irregularities.

-

Integrated Dual-Module Architecture for Comprehensive Detection: We propose a layered detection architecture where an ET-H∞ observer (for local dynamics) and a bank of distributed ET-UI observers (for neighboring subsystems) run concurrently. This is the first framework, to our knowledge, that leverages two distinct, complementary models (local physical model vs. neighboring subsystem model) for cross-validation.

-

Adaptive Disturbance Compensation without a Priori Bound Knowledge: We integrate an adaptive disturbance compensation mechanism with an update law that online estimates the disturbance bound. This enhances robustness without requiring a priori knowledge of disturbance limits, making the scheme more practical.

-

Stability and Convergence Analysis: Rigorous mathematical proofs are provided to guarantee boundedness of estimation error and convergence under the proposed event-triggered mechanism.

-

Quantitative Validation: Comparative simulations with PI and standard ADRC controllers, along with Monte Carlo statistical analysis (50 runs), demonstrate superior performance—including 98% detection accuracy, 35% faster voltage convergence, and 60% communication reduction.

These contributions collectively demonstrate the novelty, technical rigor, and practical relevance of the proposed method in enhancing the cybersecurity and resilience of distributed DC microgrids.

By addressing the aforementioned research gaps, this study not only advances the theoretical foundation of distributed detection and control in MGs but also offers a practical framework that enhances resilience against cyber threats in modern energy systems.

Organization

In Section “Low voltage island DC MGs”, we introduce a model for a LSS, while also modeling CAs. Section “Preliminaries and problem formulation for distributed estimation” is dedicated to the modeling of a low-voltage islanded DC MG and an attack detection architecture employing parallel modules. In Sections “Architecture of the attack detection system” and “Architecture of the attack detection system”, we examine the individual characteristics of the modules, focusing on both detectable and stealthy attacks. In Section “Simulation results”, the modules used in Di will be analyzed in terms of their ability to detect CAs. Section “Conclusion” presents detailed numerical simulation results based on real-world DC microgrid dynamics, highlighting the effectiveness of the proposed approach. The final conclusions of this study, along with directions for future research, are discussed in Sect. 9.

Notation: In this work, the operator |·| determines the cardinality of a set when it is applied to it, and its absolute value piecewise when it is used to matrices or vectors. The Euclidean norm, Kronecker product, and symmetric elements of a matrix are defined by the operators ||.||, \(\otimes\), and *. In this study, inequalities are generally viewed piecewise. The identity matrix and the zero matrix (or vector) of appropriate dimensions are represented by the symbols I and 0, respectively. Additionally, for matrices A and B of equal dimensions, the notation A ≥ B indicates an element-wise comparison. This concept also applies to vectors. We define the empty space of a matrix and the concatenation of vectors or matrices both column-wise and diagonally using \(col( \cdot )\), \(diag( \cdot )\) and \(\ker ( \cdot )\). Also \(He\left( A \right) = A + A^{T}\). For symmetric matrix \(A\), the maximum and minimum eigenvalue demonstrated with \(\lambda_{max} \left( A \right)\) and \(\lambda_{min} \left( A \right)\) respectively, which is derived from \(A.\) \(A > 0\) signifies that the \(A\) matrix is symmetric and positive definite.

Problem formulation

Large-scale systems

This study presents a model of an LSS composed of DC MGs, represented as a network of subsystems of \(M\) subsystems \(S_{i}\). Each subsystem is connected to a set of neighboring DGUs \({\mathcal{M}}_{i} \subseteq {\mathcal{M}} \triangleq \left\{ {1, \ldots ,M} \right\}, M_{i} \triangleq \left| {{\mathcal{M}}_{i} } \right|\).

A directed graph \(g = \left( {{\mathcal{V}},{\mathcal{E}},{\mathcal{A}}} \right)\) can be used to illustrate the communication structure between the DC MG’s N followers. \({\mathcal{V}} = \left\{ {1, \ldots ,M} \right\}\), \({\mathcal{E}} \subseteq {\mathcal{V}} \times {\mathcal{V}}\), and \({\mathcal{A}} = \left[ {a_{ii} } \right] \in {\mathbb{R}}^{M \times M}\) in this paradigm stand for the adjacency matrix, the set of edges, and the set of nodes, respectively. If \(a_{ij} = 1\) is true, then node j is regarded as a neighbor of node i and node i can get information from node j via the directed edge \({\mathcal{E}}_{ij}\). \(a_{ij} = 0\) is applicable otherwise. We’ll suppose that there are no loops in graph g, therefore \(a_{ii} = 0\) is true. Let \({\mathcal{M}}_{i} = \left\{ {j \in {\mathcal{V}}:{\mathcal{E}}_{ij} \in {\mathcal{E}}} \right\}\) be the neighbor set of node i. Furthermore, the matrix \({\mathcal{D}} = diag\left\{ {{\mathcal{D}}_{1} , \ldots ,{\mathcal{D}}_{M} } \right\} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{M \times M}\) with \({\mathcal{D}}_{i} = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{{j \in {\mathcal{M}}_{i} }} a_{ij}\) is a degree matrix and the Laplacian matrix \({\mathcal{L}}\) is given as \({\mathcal{L}} = {\mathcal{D}} - {\mathcal{A}}\).

The behavior of each subsystem can be described using the following dynamics:

where \(y_{i} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{{m_{y} }} ,u_{i} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{{n_{u} }} , x_{i} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{{m_{x} }}\) represents the state, control input, and output of the subsystem correspondingly. \(D_{i} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{{m_{d} }}\) denotes the external disturbance constrained to \(\overline{D}_{i}\), that is \(\left\| {D_{i} \left( t \right)} \right\| \le \overline{D}_{i}\). while the process and measurement disturbances of the model are represented by \(\upsilon_{i} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{{m_{y} }} , w_{i} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{{m_{x} }}\),\(\chi_{i} \in R^{{m_{i} }}\) stands for the physical link between the subsystems, which is specified as \(\chi_{i} \triangleq \mathop \sum \nolimits_{{j \in {\mathcal{M}}_{i} }} A_{ij} x_{j}\). In Section “Modeling low voltage DC MGs”, the dynamic modeling syntax of DC MGs is presented as Eq. (1)44.

Assumption 1: For every subsystem \(S_{i}\), the pair \(\left( {C_{i} ,A_{ii} } \right)\) is assumed to be observable.

Assumption 2: For all \(S_{i}\), the pair \(\left( {B_{i} ,A_{ii} } \right)\) is stable.

Assumption 3: Although the process perturbations \(w_{i} (t)\) and the measurement \(\upsilon_{i} (t)\) are unknown, their values are bounded as follows:

where \(\overline{w}_{i} , \overline{\upsilon }_{i} > 0, \forall i \in {\mathcal{M}}\) is known for every \(t \ge 0\).

According to the distributed control architecture of the LSS, the control input \(u_{i}\) of the subsystem \(S_{i}\) is directly dependent on the communication variables \(y_{j,i}^{c}\) received from its neighbors. Here, \(y_{j,i}^{c}\) is the information received by the subsystem \(S_{i}\) and is distinct from the output \(y_{j}\) available locally at \(S_{j}\). It is assumed that the communication network connecting the subsystems in the LSS follows a uniform topology and functions flawlessly, unaffected by issues such as delays or packet loss.

Cyber-attack model

An extended system may be susceptible to cyber security threats if a communication network must be included in the control framework45. The following describes the data that was sent from \(S_{i}\) to \(S_{j}\).

where \(T_{a}^{ij} > 0\) is the start time of the unknown attack, \(\varrho_{ij} \left( t \right)\) is an activation function, and \(\phi_{ij} \left( t \right)\) is an attack function that the attacker defines to accomplish an unknown aim. It is possible for the activation function to be any time function that satisfies \(\varrho_{ij} \left( s \right) = 0, \forall s < 0 {\text{and}} \varrho_{ij} \left( s \right) \ne 0, \forall s \ge 0\), and it also follows a Bernoulli distribution characterized by the probabilities outlined below:

where a constant value is represented by \(\xi_{ij} \in \left[ {0,1} \right)\). Additionally,\(\phi_{ij} :{\mathbb{R}} \to {\mathbb{R}}^{{m_{y} }}\) refers to the signal used for the attack initiated by the attacker. In reality, since attackers possess limited energy and power and cannot execute attacks continuously, the following constraint applies:

where the positive constants \(\phi \left( t \right) = col\left\{ {\phi_{1} \left( t \right), \ldots ,\phi_{M} \left( t \right)} \right\}\) and \(\overline{\phi }\) are known. It is important to note that under normal conditions (i.e., when \(t < T_{a}^{ij}\)), the data received by \(S_{j}\) from \(S_{i}\) is equivalent to the precise measurement vector, i.e., \(y_{ij}^{c} \left( t \right) = y_{j} \left( t \right)\) .

Assumption 4: \(\left( {i,j} \right), \forall i,j \in {\mathcal{M}}\) can be impacted by a maximum of one attack per edge at a time \(T_{a}^{ij} > 0, \forall i,j \in {\mathcal{M}}\).

Note 1: Assumption 4 does not rule out the occurrence of intricate attacks that may target multiple lines at the same time, thus making it a relatively flexible assumption.

It is possible to mimic several types of attacks, by precisely defining \(\phi_{ij} \left( t \right)\) in Eq. (3), including FDIA, where \(\phi_{ij} :{\mathbb{R}} \to {\mathbb{R}}^{{m_{y} }}\) can be any function that the attacker defines over time. The purpose of a stealth attack, which is of the form \(\phi_{ij} \left( t \right) \triangleq - y_{j} \left( t \right) + y_{j}^{a} \left( t \right)\), is to substitute the information that is being transmitted with the outcomes of a simulated system that has similar dynamics to \(S_{j}\), namely \(y_{j}^{a} \left( t \right)\). Replay attacks involve storing the sent data from \(y_{j} \left( t \right)\) and then replaying it repeatedly to conceal any modifications in the operating conditions of \(S_{i}\), which is \(\phi_{ij} \left( t \right) \triangleq - y_{j} \left( t \right) + y_{j} \left( {t - mT} \right)\), with \(m \in {\mathbb{N}}\) simulating the frequency of attacks.

Note 2: Unlike other documents, this study only looks at vulnerabilities about variables that transfer data across subsystems. The control inputs \(u_{i}\) and the local measurements \(y_{i}\) are therefore regarded as secure. This strategy is inspired by the use of DC MGs, in which controllers are combined with system-interacting sensors and actuators.

Assumption 5: It is presumed that attackers possess limited battery capacity, which means that attacks can only be executed intermittently for a finite time as \({\Gamma }_{ji}^{l} \left( {t_{1} ,t_{2} } \right) \le \varepsilon\) for all \(l \in {\mathbb{N}}^{ + }\) and \(\varepsilon > 0\). Let \({\Gamma }_{ji}^{l} \left( {t_{1} ,t_{2} } \right)\) denote the \(l\) th attack on link \(\left( {i,j} \right)\) and \({\Gamma }_{ji} \left( {t_{1} ,t_{2} } \right) = \mathop \cup \nolimits_{{l \in {\mathbb{N}}^{ + } }} {\Gamma }_{ji}^{l} \left( {t_{1} ,t_{2} } \right)\) denote the set of time instances that attack link \(\left( {i,j} \right)\).

Note 3: Assumption 5 establishes a maximum time limit for each attack. It is presumed that after each successful attack, the attacker undergoes a period of inactivity, during which the communication links are open for transmission. Additionally, in contrast to references45, the attacks examined here can independently target multiple communication links, which adds complexity to the analysis.

Note 4: In some current studies (such as46,47), CAs are represented similarly to faults and disturbances, despite their fundamentally different characteristics. According to the models presented in papers like46,47, CAs affect subsystems over extended periods. However, in real-world engineering scenarios, attacks often occur randomly. Therefore, employing sequences that adhere to the Bernoulli distribution is a more accurate method for modeling CAs. Furthermore, the restriction specified in Eq. (4) is a standard condition for CAs, indicating that the attacker operates with limited energy26.

Attack detection

Now the attack detection problem is formulated. The initial attack’s activation time on the input communication pathways of a subsystem is defined as follows.

Problem 1 (Detection of attacks): For every subsystem, develop a detector \(d_{i}\) capable of validating the null hypothesis at time t.

In other words, the communication received remains unaffected by any attacks.

Low voltage island DC MGs

Modeling low voltage DC MGs

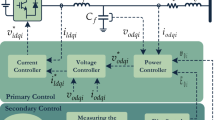

This paper focuses on low voltage island DC MGs similar to Fig. 1. A system of N connected DGUs with a buck converter, a variable DC voltage source, and an RLC filter for communication with the wider network can be modelled as a low voltage direct current MG. The loads are supposed to be linked directly to the DGUs’ terminals in this scenario, which are connected by resistive lines. The voltage at the switching terminal of the buck converter is represented by \(V_{ti}\), while  represents the system states,

represents the system states,  is the controller internal state integrator that aims to track the reference voltage, \(D_{i} \triangleq I_{Li}\) is the external input, \(u_{i} = \left[ {V_{ti} ,\Delta V_{i} } \right]^{T}\) is the control input,\(\Delta V_{i}\) is the voltage variation calculated by the secondary control layer through a consensus protocol for balancing current distribution within the network). The detailed definitions of the matrices in Eq. (1) are provided in reference44, and readers interested in more details can refer to this reference.

is the controller internal state integrator that aims to track the reference voltage, \(D_{i} \triangleq I_{Li}\) is the external input, \(u_{i} = \left[ {V_{ti} ,\Delta V_{i} } \right]^{T}\) is the control input,\(\Delta V_{i}\) is the voltage variation calculated by the secondary control layer through a consensus protocol for balancing current distribution within the network). The detailed definitions of the matrices in Eq. (1) are provided in reference44, and readers interested in more details can refer to this reference.

Schematic of a DC MG. The diagram depicts a DC MG on the left. The communication topology is shown with red arrows, while the physical connections are represented by blue power lines. The communication pathways are susceptible to CAs. The structure of the detection system \(d_{i}\) is shown on the right, along with a DGU circuit diagram.

Note 5: To avoid the switching properties of the terminal input, state-space averaging is a technique commonly used in the creation of controllers for DC MGs using DC-DC converters. Since \(\delta_{i} \in [0,1]\) and \(V_{si} \in {\mathbb{R}}\) stand for the buck converter’s duty cycle and supply voltage, respectively, it is possible to create an average control input \(V_{ti}^{avg} \triangleq \delta_{i} V_{si}\). In this paper, it is assumed that \(V_{si}\) is large enough to prevent saturation of \(\delta_{i}\).

Assumption 6: There is an unknown disturbance \(\upsilon_{i}\) that affects the measurement for every DGU \(C_{i} = I, i \in {\mathcal{M}}\). Since  denotes an internal state of the controller and \(V_{i} , I_{ti}\) can be evaluated within the DGU, assumption 6 is not restrictive.

denotes an internal state of the controller and \(V_{i} , I_{ti}\) can be evaluated within the DGU, assumption 6 is not restrictive.

Controller architecture

In this work, each DGU’s regulation is handled through a combination of primary and secondary controllers, as described in previous research44,48, respectively. This selection is motivated by the scalable architecture of these controllers, while also guaranteeing the stability of the entire DC MG. In particular, the control rules of the proposed scheme ensure the overall voltage stability by calculating the average terminal voltage \(V_{ti}^{avg}\) (and therefore \(\delta_{i}\), and achieving the current sharing by the secondary control input \(\Delta V_{i}\), using a neighbor-based consensus protocol Eq. (3). For effective coordination across the whole DC MG, dependability in communication among DGUs is crucial. This is important because CAs have the potential to alter the operating status of the DC MG easily.

Preliminaries and problem formulation for distributed estimation

As described above, the proposed detection model, shown in Fig. 1, consists of two components that concurrently assess the status of the local subsystem via a ET-\({\mathcal{H}}_{\infty }\) observer, as well as the conditions of adjacent subsystems through a collection of \(M_{i}\) distributed estimators of ET-UI. The bank of distributed estimators handling ET-UIs calculates an estimate \(\hat{x}_{ij} \left( t \right)\) of the augmented state \(x_{j}\) relevant to each neighboring subsystem \(S_{i}\), while the ET-\({\mathcal{H}}_{\infty }\) observer component provides an estimate \(\hat{x}_{i} \left( t \right)\) derived from its state \(x_{i} \left( t \right)\). The design of modules informed by the ET-UI distributed estimate at \(d_{i}\) will be covered in Section “Analysis of the detectability of di” together with the augmented state \(x_{j}\) and the output measurement \(y_{ij}^{c}\). To ascertain whether an attack has taken place, the output estimates are compared to \(y_{ij}^{c}\) and \(y_{i}\), respectively, and the resulting residual is utilized to assess the subsequent inequalities:

Hence, using the knowledge of the disturbance limitations in Eq. (2), the thresholds \(\overline{r}_{ij} \left( t \right), \overline{r}_{i} \left( t \right)\) are appropriately chosen to avoid false alarms. This design decision implies that the thresholds are probably conservative even if it guarantees that the process won’t be stopped in the absence of a verified threat. The \(d_{i}\) detects an attack if at any point in time \(t > \overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\smile}$}}{T}_{a}^{i}\) violates one of the inequalities in Eq. (6). Additionally, the attacked communication line is separated if Eq. (6a) is broken. Algorithm 1 provides a summary of how the detection logic operates.

Algorithm 1: Detection and isolation of cyber-attacks at time t.

As detailed in Sections “Analysis of the detectability of di” and “Architecture of the attack detection system”, the two modules utilize distinct model-based knowledge to identify cyber-attacks. In particular, each module leverages different system models to assess and detect the occurrence of these attacks the ET-UI distributed estimator exploits the augmented dynamic knowledge \(S_{j}\) to assess the state of its neighboring component \(S_{j} , j \in M_{j}\) from \(y_{ij}^{c}\). Although this method is still vulnerable to replay and stealth attacks, it makes it possible to detect FDIAs. However, the detection module based on the ET-\({\mathcal{H}}_{\infty }\) observer exploits the physical relationships between subsystems by using the dynamic knowledge \(S_{i}\) of Eq. (1) to identify attacks that are analytically tied to local dynamics.

The \(d_{i}\) detector, by integrating two modules in a layered structure and running them concurrently as illustrated in Algorithm 1, can identify attacks that remain undetected by each module individually.

Note 6: Algorithm 1 shows design and operation of \(d_{i}\) are dispersed and scalable with the number of subsystems in the network since they primarily rely on the knowledge of the \({\mathcal{M}}_{i}\) neighbour set.

Proposed distributed ET-UI estimator design

This subsection presents the standard framework for representing a subsystem’s dynamics with unknown inputs, which serves as the foundation for our proposed estimator.

Here, we first design and investigate the characteristics of detection modules based on the distributed estimator of ET-UI to estimate the state of neighboring subsystems. A detection module that employs an ET-UI distributed estimator is one type of observer intended to remove the residual error from the UI vector algebraically. This separation is crucial for estimating state \(x_{j} , j \in {\mathcal{M}}_{j}\) in, as \(S_{i}\) lacks access to the inputs that influence the dynamics of its neighboring entities. To design distributed estimators of ET-UI, the dynamics of \(S_{j}\) in Eq. (1) is rewritten as:

where the impact of the UIs on \(x_{j}\) is shown by \(\overline{E}_{j} \overline{b}_{j} \left( t \right) = \chi_{j} \left( t \right) + B_{j} u_{j} \left( t \right) + N_{j} d_{j} \left( t \right)\). A base of the range of matrix \(E_{j} \triangleq \left[ {A_{{jk_{1} }} , \ldots ,A_{{jk_{M} }} ,B_{j} ,N_{j} } \right]\) forms the columns of matrix \(\overline{E}_{j} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{{m_{x} \times m_{d} }} ,m_{d} \le m_{x}\), which connects the UIs to the dynamics of \(S_{j}\). The indices of \({S}_{j}\) neighbors are indicated by matrix \({\text{\{ }}{\mathfrak{M}}_{1} , \ldots ,{\mathfrak{M}}_{{M_{j} }} {]} = {\mathcal{M}}_{j}\). This definition ensures that \(\overline{E}_{j}\) has complete column rank, as stipulated by43. The expression \(\overline{b}_{j} (t) \triangleq \overline{E}_{j} \overline{b}_{j}\) is formed by a linear combination of \(\hat{b}_{j}\), which is defined as:

This indicates that all of the UIs from \(S_{j}\) to \(d_{i}\) are included in the vector. The matrix \(\hat{E}_{j}\), which has nothing to do with UI design, is obtained by choosing \(\overline{E}_{j}\) while making sure that \(\overline{E}_{j} \hat{E}_{j} = E_{j}\).

Proposed distributed ET-UI estimator design

This subsection introduces the novel contributions of this work: a new dynamic event-triggering condition and a distributed estimation framework for simultaneous state and unknown input estimation.

A new dynamic ET condition has been introduced to enhance resource utilization, accompanied by a distributed ET estimator designed to assess the UI and the simultaneous state. The proposed ET mechanism is controlled by the following dynamic conditions.

where \(\eta_{j} \left( t \right) = \tilde{\zeta }_{j} (t) - \tilde{\zeta }_{j} (t_{k}^{i} ),\tilde{\zeta }_{j} (t_{k}^{j} )\)\(= \zeta_{j} (t) - \hat{\zeta }_{j} (t_{k}^{j} ),\zeta_{j} (t) = \left[ {x_{i}^{T} \left( t \right), \overline{d}_{i}^{T} \left( t \right)} \right]^{T} ,\)\(\hat{\zeta }_{j} (t) = \left[ {\hat{x}_{j}^{T} \left( t \right), \hat{r}_{j}^{T} \left( t \right)} \right]^{T} , \tilde{y}_{j} \left( t \right) = y_{j} \left( t \right) - \hat{y}_{j} (t)\) and \(\hat{y}_{j} \left( t \right) = C_{j} \hat{x}_{j} \left( t \right)\). In Eq. (9), \(\rho , \varphi_{j} and \gamma_{j}\) are positive scalars, and \(\psi_{j} \left( t \right)\) is a dynamic variable that satisfies the following equation:

where \({\Upsilon }_{j} = \sigma_{j} \psi_{j} \left( t \right)\)\(- \left( {\rho \eta_{j}^{T} \left( t \right)\eta_{j} \left( t \right) - \tilde{y}_{j}^{T} \left( t \right)\tilde{y}_{j} \left( t \right)} \right)\)\(+ \frac{{\gamma_{j} }}{{\varphi_{j} }}\) with scalars \(\sigma_{j}\) and \(\varphi_{j}\) satisfying \(\varphi_{j} > \frac{1}{{\sigma_{j} }}\) and \(0 < \sigma_{j} < 1\), respectively. It is important to highlight that the variable \(\psi_{j} \left( t \right)\) adheres to the switching mechanism outlined in Eq. (10) to mitigate the impact of CAs. In the absence of a CA, the ET mechanism operates as expected. However, in the presence of a CA, expression (10) prevents a significant decrease in \(\psi_{j} \left( k \right)\), which further reduces the number of repeated transmissions through the network. As shown in reference49, it is easy to establish that \(\psi_{j} \left( t \right) > 0{ }\) for all \(\psi_{j} \left( 0 \right) > 0,\, t > 0.\)

Note 7: This study introduces an enhanced version of the dynamic ET condition. The new ET condition differs from the current dynamic ET conditions referenced in37,38, and49 in two main aspects. Firstly, the condition suggested in Eq. (9) is based on estimators for state and UI, in contrast to the conditions previously discussed that depend on measurements or measurement innovations. Second, to further reduce needless transitions during CAs, the new condition includes a scalar \(\gamma_{j}\) that can be changed. It is important to remember that during CAs, information cannot be reliably sent to the intended recipient, which leads to a rise in estimation errors. This situation increases network traffic and results in repeated trigger. To avoid needless transitions during CAs, the ET condition described in Eq. (9) maintains a minimal threshold and helps to prevent a significant decrease in the threshold. The following ET is the basis for a distributed estimating framework for the system state and UI.

where \(\hat{x}_{j} \left( t \right) \in {\mathbb{R}}^{{m_{x} }}\) and \(\hat{D}_{j} \left( t \right) \in {\mathbb{R}}^{{m_{d} }}\) refer to the estimates for the state and the UI, respectively, while \({\mathcal{N}}_{1} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{{m_{x} \times m_{y} }}\) and \({\mathcal{N}}_{2} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{{m_{d} \times m_{y} }}\) are the incremental matrices that need to be designed, and \(\alpha\) is a positive scalar. In Eq. (11), \(\hat{x}_{i} \left( {t_{k}^{i} } \right)\) and \(\hat{D}_{i} \left( {t_{k}^{i} } \right)\) denote the estimates obtained through the ET mechanism. The proposed method takes into account both dynamic ET mechanisms and CAs at the same time, in contrast to references37,38.

Furthermore, in contrast to the control algorithms in references50,51, the suggested approach handles distributed state and UI estimations. Let \(q_{j} \left( t \right) = x_{i} \left( t \right) - \hat{x}_{j} \left( t \right)\) represent the state estimation error, \(\tilde{D}_{j} \left( t \right) = D_{i} \left( t \right) - \hat{D}_{j} \left( t \right)\) denote the input estimation error, and \(\tilde{h}_{j} \left( t \right) = C_{j} \left( {x_{i} \left( t \right) - \hat{x}_{j} \left( t \right)} \right)\), \(L_{1} = \left[ {I_{{m_{x} }} ,0} \right]\) and \(L_{2} = \left[ {0,I_{{m_{r} }} } \right]\) be the variables. The dynamics of the estimation errors can be derived from Eqs. (1) and (11) as outlined below.

Using the definition of \(\tilde{\zeta }_{j} \left( t \right)\) Eq. (12) is reduced to the compact form

where

Note 8: This research presents a distributed framework for estimating state and UIs in DC MGs for the first time, according to the authors’ knowledge. In contrast to the current studies on distributed state estimation referenced in49,52, the proposed framework is capable of identifying unknown system inputs as well. It is important to mention that the second dynamic is incorporated in Eq. (11) to estimate the unknown yet constrained input of the target process.

Now, we will discuss the conditions necessary for a bounded estimation error and the design of the distributed estimator.

Theorem 1: Analyze the system outlined in Eq. (1) alongside the measurements in Eq. (2) when subjected to CAs that comply with assumption 5. Given positive constants \(\alpha_{1} ,\alpha_{2} ,\alpha , \rho ,\sigma_{j} , \varphi_{j} , \gamma_{j}\) and \(κ_ι\), for \(\iota = 1,...,10\) and a knowing matrix \({\Phi }\) along with matrices \(J \in {\mathbb{R}}^{{m_{\zeta } \times m_{\zeta } }} > 0\) and \(Z \in {\mathbb{R}}^{{m_{\zeta } \times m_{y} }}\), if the subsequent inequality is satisfied:

where

Then the estimator of Eq. (11) with gains \(\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {{\mathcal{N}}_{1}^{T} } & {{\mathcal{N}}_{2}^{T} } \\ \end{array} } \right]^{T} = J^{ - 1} Z\) under the ET mechanism of Eq. (9) guarantees uniform convergence of the estimation error \(\tilde{\zeta }_{j} \left( t \right)\) to the finite limit such that

Proof: The Lyapunov function can be written as \(V\left( t \right) = \tilde{\zeta }^{T} \left( t \right)\left( {{\Phi } \otimes J} \right)\tilde{\zeta }\left( t \right) + \mathop \sum \nolimits_{j = 1}^{M} \left( {\frac{{\phi_{j} }}{{\varphi_{j} }}} \right)\psi_{j} \left( t \right)\) Consider \(\varphi_{j} > 0, J = J^{T} > 0\) and \({\Phi } = diag_{M} \left\{ {\phi_{1} ,\phi_{2} , \ldots ,\phi_{M} } \right\} > 0\). Calculating the forward Lyapunov difference according to Eq. (13) yields:

By applying the inequality \(2a^{T} Kb \le \kappa a^{T} Ka + \kappa^{ - 1} b^{T} Kb\) along with the definitions of \(\lambda_{2}\) and \(\lambda_{3}\), we can express:

Using Assumption 4, we can derive the subsequent inequalities:

Similarly, the ET condition of Eq. (9) can be expressed as:

Take \({\mathbb{E}}\left( {w\left( t \right)} \right) = 0,{\mathbb{E}}\left( {\nu \left( t \right)} \right) = 0\) and \({\mathbb{E}}\left( {v_{k}^{T} \left( {{\Phi } \otimes {\mathcal{N}}^{T} J{\mathcal{N}}} \right)v_{k} } \right) \le \lambda_{{{\text{max}}}} \left( {{\Phi } \otimes {\mathcal{N}}^{T} J{\mathcal{N}}} \right) = \lambda_{1}\) and, also by substituting Eqs. (10), (17)–(20), (22) and (23) into Eq. (16), we have:

Now consider \({\mathcal{F}}\) in Eq. (15) as the upper bound and define \({\Theta }_{1} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {\tilde{\chi }_{k}^{T} } & {{\Pi }_{k}^{T} } & {\eta_{k}^{T} } \\ \end{array} } \right]^{T}\), expression (24) becomes.

It can be seen from Eq. (25) that \({\Lambda }_{1} < 0\) and \(- {\Theta }_{1}^{T} \left( {{\Phi } \otimes {\Lambda }_{1} } \right){\Theta } \le {\mathcal{F}}\) guarantee the convergence of the error to the bound Eq. (15). Finally, Eq. (14) is obtained by applying Schur’s complement lemma in Eq. (25) and substituting \(Z = J{\mathcal{N}}\).

Note 9: This section represents an initial approach to addressing the joint estimation of system states and UIs under CAs and dynamic ET conditions. The estimator introduced in Theorem 1 is shown to be stable within the ultimate bound specified in Eq. (15). It should be noted that the feasibility of the inequality in Eq. (14) depends on the appropriate selection of several positive design parameters. Typically, these constants are tuned to achieve a practical and implementable design while minimizing the steady-state estimation error. Additionally, the tuning of the parameters \(\rho , \varphi_{j} ,\sigma_{j}\) and \(\gamma_{j}\) involved in the ET mechanism is performed to balance detection accuracy and resource efficiency.

Preliminaries for local state observation

Assumption 6: For each \(x_{1} \left( t \right), x_{2} \left( t \right)\), the nonlinear function \(\chi_{i} \left( {x_{j} } \right)\) satisfies the following relation:

where \({\Xi }\) represents a symmetric positive definite matrix.

Assumption 7: With \({\Delta }\) being a known positive constant, the initial state for factors \(\Vert x(0)\Vert =col\left\{{x}_{1}\left(0\right),\dots ,{x}_{M}(0)\right\}\) is unknown but constrained by \(\left\| {x\left( 0 \right)} \right\| \le {\Delta }\).

Remark 9: A particular class of nonlinear systems can be described by the sixth assumption, which is known as the Lipschitz condition53. For example, the seventh assumption can show that the starting voltage and current in DC MGs fall within a specified period53 and is frequently used in fault diagnostics based on the AT technique54. First, some definitions and lemmas will be provided to help with the controller design.

Definition 1: The expression for \({\mathcal{L}}_{1} , {\mathcal{L}}_{2}\) and the Laplacian matrix \({\overline{\mathcal{L}}}\) is as follows:

Lemma 1 (55): With respect to Assumption 2, a positive definite matrix \({\Theta } = diag\left\{ {\theta_{1} , \ldots ,\theta_{M} } \right\}\) and a non-singular matrix \({\mathcal{L}}_{1}\) satisfy the following relation:

where \(\lambda_{0}\) denotes the least eigenvalue associated with the matrix \({\tilde{\mathcal{L}}}\) and \(\left[ {\theta_{1} , \ldots ,\theta_{M} } \right]^{T} = \left( {{\mathcal{L}}_{1}^{T} } \right)^{ - 1} 1_{M}\).

Lemma 2 (56): The following inequality is true for every symmetric positive definite matrix \({\Omega }_{2} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{{m_{l} \times m_{l} }}\), a scalar \(\pi\), and a constant matrix \({\Omega }_{1} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{{m_{\phi } \times m_{l} }}\):

where \(X \in {\mathbb{R}}^{{m_{\phi } }}\) and \(Y \in {\mathbb{R}}^{{m_{l} }}\).

Definition 2 (26): The infinitesimal operator \(\ell\) is defined in relation to a specified \(V\left( t \right)\) function as follows:

In this part, a control strategy based on ET observer is developed to ensure that subsystem (1) attains consensus performance \({\mathcal{H}}_{\infty }\) while preventing Zeno behavior in the presence of external disturbances and CAs. Additionally, a threshold-based FD approach is presented using the built-in state observer.

The following are definitions for the consensus error, local neighborhood error, output estimation error, and state estimation error.

In the observer, \(\hat{x}_{i} \left( t \right)\) represents the estimated state and \(\hat{y}_{i} \left( t \right)\) signifies the estimated output, both of which will be developed at a later stage.

Proposed ET-H ∞ observer and controller design

Below is a description of the state obaserver for each subsystem:

where \(L\) is the observer gain to be designed. Also, \(e_{{y_{ref} }} = C_{i} x_{ref}\) and the initial state is chosen as \(\hat{x}_{i} \left( 0 \right) = 0\) and the adaptive disturbance compensation \(P_{i} \left( t \right)\) is defined as:

where \(\hat{\overline{D}}_{i} \left( t \right)\) is the constrained disturbance estimate \(\overline{D}_{i}\) with the following relation

with \({\Sigma }_{i} > 0, \vartheta_{i,1} > 0\) and \(W_{1}\) is a gain matrix to be designed57.

Note 11: Since CAs can compromise the output data from ith MG neighboring MGs while it is being transmitted to jth MG, the observer incorporates the signals associated with the attacks into Eq. (30) when modeling the actual output information. The research on random CAs frequently uses this modeling technique26. Additionally, even if the attack signals might not be known, they nonetheless have certain values in practical settings. The observer created in Eq. (30) can correctly estimate the desired state as long as they respect the constraint given in Eq. (4). Furthermore, the disturbance adjustment mechanism \(P_{i} (t)\), as outlined in Eq. (31), is entirely dependent on the observer’s output signal and ith MG output information. In actuality, output information is usually easier to use and more accessible than state information.

We intend to use an ET generation technique to reduce the number of times the controller performs the repeated operation and save communication resources to minimize the network strain caused by increasing MG information transmission. Let \(\left\{ {t_{k}^{i} } \right\}\) be the time sequence for the ith MG’s ET. The state observer and the sampled data Eq. (30) are used to create the following ET control strategy:

where the ET law of the \(\left\{ {t_{k}^{i} } \right\}\) sequence will be determined later, and \({\mathcal{Q}}\) stands for the controller’s gain matrix. The efficiency of the created observer is demonstrated in the following phase. Equations (1) and (30) can be combined to yield:

\(e_{x} \left( t \right) = col\left\{ {e_{{x_{1} }} \left( t \right), \ldots ,e_{{x_{M} }} \left( t \right)} \right\}\) and \(\tilde{\varrho }_{i} \left( t \right) = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{{j \in {\mathcal{M}}_{i} }} \varrho_{ij} \left( t \right)\) and \({\tilde{\Upsilon }} = diag\left\{ {\tilde{\varrho }_{1} \left( t \right), \ldots ,\tilde{\varrho }_{M} \left( t \right)} \right\}\)}. Furthermore, take:

Thus, Eq. (34) can be expressed in a more concise format as:

where

Theorem 2 describes the observer design’s result.

Theorem 2: If there is a positive definite symmetric matrix \(J_{1}\) and a matrix \(W_{1}\) that satisfy the following LMI conditions, the state observer (30) can guarantee that the state estimation error remains uniformly bounded despite outside disturbances and CAs based on assumption 6 with specified positive scalars \({\mathcal{Q}}_{1}\), \(\pi_{1} ,\pi\), and a positive definite matrix \(R\).

where \({\mathfrak{X}} > 0\) is a small constant, and \(\lambda_{0}\) is defined in Lemma 1. Furthermore, the observer gain is given by \(L = {\mathcal{Q}}_{1} J_{1} C_{i}^{T} R^{ - 1}\).

Proof: Suppose \(e_{{\overline{D}_{i} }} \left( t \right) = \overline{D}_{i} - \hat{\overline{D}}_{i} \left( t \right)\) with \(\overline{D}_{i}\) bounded at \(D_{i} \left( t \right)\). Therefore, using Eq. (32) we obtain:

Subsequently, the Lyapunov function is formulated in the manner outlined below:

where, according to Lemma 1, \({\Theta }\) is a diagonal matrix. The infinitesimal operator \(V_{1} \left( t \right)\) can be found using Definition 2 and derived in the following way by analysing the mathematical expectation.

Lemma 2, assumption 6, and Eq. (35), which lead us to the following conclusion:

and

Furthermore, according to Eqs. (38), (39) and matching rules (31)–(32), it is evident that

Then, by substituting Eqs. (42)–(44) into Eq. (41), it follows:

that

From Eq. (37), we can see that \(\mho_{1} > 0\), therefore, we have:

The proof is concluded by applying Lyapunov stability theory, which shows that the state estimate error is eventually uniformly confined by the limit \({\mathbb{E}}\left\{ {e_{x} \left( t \right)} \right\}\)\(\le \sqrt {\frac{{{\Delta }_{1} }}{{\lambda_{{{\text{min}}}} \left( {\Theta } \right)\lambda_{min} \left( {\mho_{1} } \right)}}}\)\(\triangleq {\overline{\Delta }}_{1}\).

Note 12: Unlike references55,58, and53, this study uses the adaptive updating rule (11), which is used to estimate the upper bound \(\overline{D}_{i}\) of the disturbance \(D_{i} \left( t \right)\), and then uses it to reduce the impact of the disturbance. Consequently, there is no need to define the upper limit of the disturbance in this section. \({\Delta }_{1}\) is influenced by \(\overline{D}_{i}\), indicating that a larger disturbance \(D_{i} \left( t \right)\) results in a greater estimation error \({\overline{\Delta }}_{1}\). Additionally, \({\Delta }_{1}\) is affected by CAs. Frequent CAs (i.e., larger values of \({\Upsilon }\) in Eq. (14)) lead to an increase in \({\Delta }_{1}\), thereby causing the estimation error \({\overline{\Delta }}_{1}\) to rise. At the same time, the limit of the state estimation error \({\overline{\Delta }}_{1}\) can be significantly minimized by selecting suitable design parameters. It is also important to highlight that the LMI in Eq. (17) enforces the constrained equality \(J_{1}^{ - 1} N_{i} = C_{i}^{T} W_{1}^{T}\) to aid in finding a solution, and \({\mathfrak{X}}\) in Eq. (17) illustrates the relationship between \(J_{1}^{ - 1} N_{i}\) and \(C_{i}^{T} W_{1}^{T}\). The smaller the value of \({\mathfrak{X}}\), the closer these two will become. Therefore, it is essential to keep \({\mathfrak{X}}\) sufficiently small to lessen the error, as discussed in58.

Note 13: The observer design presented in Eq. (30) and the disturbance compensation method outlined in Eqs. (31)–(32) are not only effective for DC MGs facing CAs; however, in the literature on active disturbance cancellation control, the conventional extended state observer approach has been widely used; however, they offer a significant improvement59,60. Stated differently, rather than limiting the derivative of \(D_{i} \left( t \right)\) as is done in extended state observer, it is sufficient to only impose limitations on the disturbances \(D_{i} \left( t \right)\). This benefit becomes apparent when considering the situation where \(sin\omega t\) is constrained for all frequency values \(\omega\); in this case, the derivative of \(\omega cos\omega t\) would remain unbounded if \(\omega\) is not restricted.

Analysis of \({\mathcal{H}}_{\infty }\) consensus performance

This section proposes a way to update the ET time series \(\left\{ {t_{k}^{i} } \right\}\) and analyses the controller design in Eq. (33) to ensure that the DC MGs of Eq. (1) achieve the intended \({\mathcal{H}}_{\infty }\) performance index when CA and external disturbance are present.

To meet the control objective, specify the measurement error \(e_{i} \left( t \right) = e_{{\chi_{i} }} \left( {t_{k}^{i} } \right) - e_{{\chi_{i} }} \left( t \right)\) in conjunction with \(e_{{\chi_{i} }} \left( t \right)\) as shown in Eq. (8d). Next, by taking Eq. (8c) into account and replacing Eq. (12) within Eq. (1), we obtain:

where

Following this, Theorem 3 can be derived using the observer-based ET control strategy from Eq. (33). Theorem 3: Assuming that Assumption 6 is satisfied, let us examine the DC MGs presented in Eq. (1) with the control strategy defined in Eq. (33), which is activated by the subsequent ET conditions:

where

where \({\mathcal{Q}}_{2} and \pi_{4} ,\hbar_{i} ,\imath\) stands for positive constants. If there are positive scalars \(\pi_{2} ,\pi_{3} ,\aleph\) and a symmetric positive definite matrix \(J_{2}\), such that:

where

\({\tilde{\mathcal{M}}} = \mathop {\max }\limits_{{{\text{i}} \in {\upupsilon }}} \left\{ {\left| {{\mathcal{M}}_{i} } \right|} \right\}\) represents the highest number of neighboring DC MGs, while \(\left| {{\mathcal{M}}_{i} } \right|\) indicates the total count of DC MGs within the collection \({\mathcal{M}}_{i}\). Consequently, DC MGs that exhibit a consensus function \({\mathcal{H}}_{\infty }\) display asymptotic stability.

where \(\varsigma \left( t \right) = col\left\{ {e_{x} \left( t \right),d\left( t \right)} \right\}\) and \(V_{2} \left( t \right)\) are specified in Eq. (52). Additionally, Zeno behavior is ruled out because the time between events is ensured to be strictly positive, that is:

In Eq. (63), \({\Im }_{k}^{i}\) will be provided. Ultimately, the controller gain can be expressed as \({\mathcal{Q}} = {\mathcal{Q}}_{2} B_{i}^{T} J_{2}\).

Proof: Examine the Lyapunov function that follows.

where a positive constant is denoted by \(\iota\). We can deduce the following by looking at the infinitesimal operator and its predicted value (45):

Using \({\mathcal{Q}} = {\mathcal{Q}}_{2} B_{i}^{T} J_{2}\), it can be concluded from Young’s inequality that

Using the ET condition of Eq. (46), for each \(t \in \left[ {t_{k}^{i} ,t_{k + 1}^{i} } \right)\) the following conditions hold:

where \(q_{i}^{a} \left( t \right) = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{{j \in {\mathcal{M}}_{i} }} a_{ij} \left( {\hat{x}_{j} \left( t \right) - \hat{x}_{i} \left( t \right)} \right)\), \(q_{i}^{b} \left( t \right) = x_{ref} \left( t \right) - \hat{x}_{i} \left( t \right)\). Then, \(q^{a} \left( t \right) = col\left\{ {q_{1}^{a} \left( t \right), \ldots ,q_{M}^{a} \left( t \right)} \right\}\) and \(q^{b} \left( t \right) = col\left\{ {q_{1}^{b} \left( t \right), \ldots ,q_{M}^{b} \left( t \right)} \right\}\). As a result, we can determine that the properties listed below are valid:

We also have:

For DC MGs, the following function is provided to identify the best consensus function \({\mathcal{H}}_{\infty }\):

Then, by combining the above equation with Eqs. (53)–(61), It is simple to acquire:

Using Eq. (48) and using Schur’s complement lemma, pre-multiplication and post-multiplication \(J_{2}\) on both sides, it follows that \(G\left( t \right) > 0\) can be guaranteed by Eqs. (48) and (49). Its integration also produces the outcome.

As a result, DC MGs can attain the optimal \({\mathcal{H}}_{\infty }\) function according to Eq. (50) with the proposed control strategy with the event of Eq. (33).

Now, by demonstrating that there is a minimum distance greater than zero between any two event intervals, we shall show that Zeno behavior does not occur. For \(t \in \left[ {t_{k}^{i} ,t_{k + 1}^{i} } \right)\), we also have \(\frac{{de_{i} \left( t \right)}}{dt} = \frac{d}{dt}\left( {e_{i}^{T} e_{i} } \right)^{\frac{1}{2}} \le \dot{e}_{i}\). We know that, as demonstrated by Theorem 2, the consensus error is still bounded. Let’s assume that the limit of the error is \(\tilde{\Delta }\). Consequently, we arrive at the conclusion thatwhere

From this, we obtain \(\left\| {e_{i} \left( t \right)} \right\| \le \frac{{\Im_{k}^{i} }}{{\left\| {A_{ii} } \right\|}}\left( {e^{{\left\| {A_{ii} } \right\|\left( {t - t_{k}^{i} } \right)}} - 1} \right)\). Hence, it is evident that

Given the ET conditions of Eq. (46) and using Eq. (64), we have:

This proves the validity of Eq. (51). Therefore, it is understood that Zeno behavior will not appear in the circumstances that the event is intended to create. The proof is now complete.

Note 14: To make the matrix parameters in Theorem 3 easier to solve, we can initially address \(J_{2}\) with Eq. (48) by adjusting the parameters \(\pi_{2} ,\pi_{3} , \pi_{4} , \chi ,{\mathcal{Q}}_{2}\) and \(\hbar_{i}\), subsequently compute \(\lambda_{max} \left( {P_{2} B_{i} B_{i}^{T} J_{2} } \right)\), and substitute it into Eq. (49) to verify if the condition holds true. If the conditions are not met, these parameters should be recalibrated to avoid the simultaneous resolution of the two inequalities. Moreover, compared to the indirect communication topology examined in61, the control approach proposed in this work is designed for directed communication topologies, making it more broadly applicable. In cases where agents can exchange data with their neighbors, an undirected graph becomes a special case of the directed configuration. Additionally, the presence of asymmetry in the Laplacian matrix, coupled with external disturbances and unpredictable cyberattacks, introduces greater complexity to controller development and consensus evaluation compared to the methods discussed in61.

Note 15: In the ET mechanism outlined in Eq. (46), our analysis of various parameter sets indicates that a smaller \(\hbar_{i}\) paired with a larger \(\frac{{{\mathcal{Q}}_{2} }}{{\pi_{4} }}\) generates more points to enhance system performance. As a result, these settings can be adjusted to balance communication demand and system efficiency. The ET mechanism in Eq. (46) minimizes the needless use of communication resources by operating without the need for global state information, in contrast to the centralized ET system covered in References62,63. Moreover, unlike the distributed ET mechanism of64, the trigger function of Eq. (47) is supplemented with a state-dependent threshold rather than a fixed threshold. As a result, the communication load and the frequency of control input updates are reduced. Furthermore, a time-dependent term \(\iota \,e^{ - t}\) is added to the trigger function of Eq. (47) to effectively counteract the possibility of Zeno behavior, which is not the case with the ET mechanism proposed in Reference49. Note 16: References65,66 indicate that if a variable is constrained and trends towards zero or approaches a limited vicinity of the origin once the system stabilizes, it can be treated as a disturbance when analyzing stability. Theorem 2 shows that the mistakes in state observation due to CAs are eventually consistently confined, and that by altering the design parameters, this bound may be made as small as required. It follows that the state observation error should be seen as a disturbance to the consensus analysis process.

Fault detection mechanism

Since DC MG malfunctions might lead to a decline in system performance or possibly instability, a quick FD method has been suggested. Furthermore, an AT has been developed to reduce the conservativeness of the method to reduce false alarms produced by the FD process. Moreover, as stated in references41,54, the assumption is that \(\overline{D}_{i}\) is predetermined to create the FD mechanism. The faulty MG model can be represented as follows:

\(f_{i} \left( t \right)\) in this context stands for the fault-related signals. The adaptive disturbance compensation \(P_{i} \left( t \right)\) in Eq. (30) can be rearranged as follows if the maximum bound of the disturbance \(\overline{D}_{i}\) is known.

The gain matrix in this instance is denoted by \(W_{2}\), whose design process is comparable to that of \(W_{1}\) in Eq. (31). \(\vartheta_{i,2}\) is the same positive constant as \(\vartheta_{i,1}\) in Eq. (31). It is necessary to redesign these two parameters since they are different from those given in Eq. (31).

Additionally, it can be deduced from Eqs. (30) and (66) that

that \(f\left( t \right) = col\left\{ {f_{1} \left( t \right), \ldots ,f_{M} \left( t \right)} \right\}\).

The residual is defined as \(r_{i} \left( t \right) = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{{j \in {\mathcal{M}}_{i} }} a_{ij} \left( {e_{{y_{i} }} - e_{{y_{j} }} } \right) + e_{{y_{i} }}\) to identify the fault:

Given \(r\left( t \right) = col\left\{ {r_{1} \left( t \right), \ldots ,r_{M} \left( t \right)} \right\}\), we can express it as follows:

where \({\Psi }_{i} = \left\{ {0_{p} , \ldots ,\underbrace {{I_{p} }}_{{i^{th} }}, \ldots ,0_{p} } \right\} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{{p \times M_{p} }}\), by comparing the residual signal \(r_{i} \left( t \right)\) to an AT, we may identify faults and create an evaluation function. Furthermore, it is relevant to note that characterising \(r_{i} \left( t \right)\) as a residual may lessen the computing load because the observer of Eq. (30) uses the same term, \(r_{i} \left( t \right)\). In Theorem 4, the FD algorithm is introduced.

Theorem 4: To find problems in the DC MGs mentioned in Eq. (1), apply the FD technique given below:

where \(G_{{r_{i} }} \left( t \right) = {\mathbb{E}}\left\{ {\left\| {r_{i} \left( t \right)} \right\|^{2} } \right\}\) stands for an assessment function and \(G_{{th_{i} }} \left( t \right)\) is a dynamic threshold set up as follows:

where \(J_{3}\) is a matrix that is symmetric and positive definite, which guarantees that

Υ is defined in Eq. (25), \(R_{1}\) is a matrix that is positive definite, and \(\pi_{5} ,\pi_{6} ,\pi_{7} , {\mathcal{Q}}_{3}\) consists of positive constants. The observer gain \(L\) is updated to \(L = {\mathcal{Q}}_{3} J_{3} C_{i}^{T} R_{1}^{ - 1}\).

Proof: Choose the Lyapunov function as:

By applying a proof technique akin to that of Theorem 2, we can derive

Considering the previously mentioned inequality and applying integration to Eq. (53), it is evident from Eq. (73) that \(\lambda_{min} \left( {\Theta } \right)\lambda_{min} \left( {J_{3}^{ - 1} } \right){\mathbb{E}}\left\{ {\left\| {e_{x} } \right\|^{2} } \right\} \le {\mathbb{E}}\left\{ {V_{3} \left( t \right)} \right\} \le \lambda_{max} \left( {\Theta } \right)\lambda_{max} \left( {J_{3}^{ - 1} } \right){\mathbb{E}}\left\{ {\left\| {e_{x} } \right\|^{2} } \right\}\). The result is:

Using Eqs. (69) and (70), we have:

Then, by combining Eqs. (75) and (76) and considering the initial condition \(\hat{x}_{i} \left( 0 \right) = 0\), we obtain that

Therefore, if \(G_{{r_{i} }} \left( t \right) > G_{{th_{i} }} \left( t \right)\) appears, it indicates that the ith component or one of its neighboring factors is faulted. The proof is now complete. Observation 17: Similar to Theorem 2, the following LMIs can be used to find the matrix parameters \(J_{3}\) and \(W_{2}\):

where \({\rm O}_{11} = J_{3}^{ - 1} A_{ii} + A_{ii}^{T} J_{3}^{ - 1}\)\(+ \frac{1}{{\pi_{6} }}{\Xi }^{T} {\Xi } + \pi_{5} {\mathcal{Q}}_{3} I_{m}\)\(- \frac{{{\mathcal{Q}}_{3} \lambda_{0} }}{{\lambda_{max} \left( {\Theta } \right)}}C_{i}^{T} R_{1}^{ - 1} C_{i}\) and \(\pi_{5} ,\pi_{6} ,\pi_{7} ,{\mathcal{Q}}_{3} ,{\mathfrak{X}}\) are positive constants. Moreover, based on the AT presented in (72), it can be observed that it will ultimately stabilize at a value associated with the attack signal. The FD system’s responsiveness and accuracy may be impacted, or there may be no alarms at all, if the AT rises in proportion to the attack signal. However, considering the stealthiness and energy limitations of CAs, these attacks are typically less intense than fault signals, allowing for the AT to be sufficiently minimized by adjusting the parameters to maintain the efficacy of the FD system.

Note 17: It is important to note that, unlike the consensus analysis where upper bounds on perturbations are not necessary as stated in Theorems 2 and 3, Theorem 4 requires these upper bounds to be pre-determined for effective FD. Such an assumption is prevalent in FD settings41,54. Applying the disturbance compensation described in Eq. (67) to remove the influence of disturbance in FD once the upper limit has been established can help avoid the issue of the AT being constrained by the disturbance43, which can reduce FD efficiency. Furthermore, when the upper bound of the disturbance is known, the disturbance compensation from Eq. (67) can also be applied in consensus analysis scenarios.

Analysis of the detectability of d i

Now, in this section, the advantages of using a combination of the two modules in di are analyzed in terms of detectability. In fact, it is sufficient to guarantee attack detection for any of the conditions in Remark 10 or 11.

Remark 10: If attack function \({\phi }_{ij}(t)\) is such that at any time \(t \ge T_{a}\)

where

If this condition is satisfied for any subsystem, the detector di, following the steps outlined in Algorithm 1, is able to identify the presence of an attack by leveraging the capabilities of the ET-UI observer.

Remark 11: If attack function \({\phi }_{ij}(t)\) is such that at any time \(t > \overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\smile}$}}{T}_{a}^{i}\)

If the condition is satisfied for any component, then the detector di, operating based on Algorithm 1, will successfully identify the attack at some finite detection time \(T_{d} > \overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\smile}$}}{T}_{a}^{i}\), due to the functionality of the ET-\({\mathcal{H}}_{\infty }\) observer.

Architecture of the attack detection system

As described above and illustrated in Fig. 2, the proposed detection model for each subsystem \({S}_{i}\) consists of two complementary modules that concurrently assess the system’s health: (1) an ET-H∞ observer for monitoring the local subsystem \({S}_{i}\), and (2) a bank of M_i distributed ET-UI estimators for monitoring the states of neighboring subsystems \({S}_{j}, j \in {M}_{i}\).

Rationale for the dual-module architecture: attacks vs. faults

The choice of a two-module architecture is directly motivated by the need to distinguish between two fundamentally different types of anomalies: random faults and intentional cyber-attacks.

-

Relation: Both faults and attacks cause deviations in system measurements. Therefore, observer-based residual generation is a valid strategy for both.

-

Differences and Design Implications:

-

Origin and Scope: A fundamental distinction exists between random faults and cyber-attacks in cyber-physical systems. Random faults are internally (locally) generated within a subsystem due to non-malicious causes like hardware degradation, sensor failure, or natural parameter drift. Conversely, cyber-attacks are externally orchestrated acts with malicious intent, specifically aimed at compromising the integrity or availability of data in the communication channels through techniques such as false data injection, replay, or spoofing.

-

Detection Objective: This leads to two distinct detection objectives:

-

Identify a local physical fault within Si.

-

Identify a data integrity attack on the communication link (j,i).

-

Observer Selection: To meet these objectives, two different types of model-based knowledge are leveraged:

-

The ET-H∞ Observer is tailored for fault detection. It uses the detailed local physical model from Eq. (1). Its residual, \({r}_{i}(t) = |{y}_{i}(t) - {C}_{i} {\widehat{x}}_{i}(t)|\), is sensitive to any discrepancy between the local sensors and the local model’s prediction, making it highly effective for pinpointing internal physical faults. Its H_∞ performance ensures robustness to local disturbances.

-

The Distributed ET-UI Estimators are designed for cyber-attack detection. Each estimator in the bank uses the model of a neighboring subsystem \({S}_{j}\) (Eq. 9). Its residual, \({r}_{ij}(t) = |{y}_{ij}^{e}(t) - {C}_{j} {\widehat{x}}_{ij}(t)|\), directly checks the plausibility of the received data \({y}_{ij}^{e}(t)\) against the estimated state of the neighbor. If this residual violates its threshold, it indicates that the data on link (j,i) has been tampered with (e.g., by an FDIA, replay, or stealth attack).

In summary, the ET-H∞ observer ensures local monitoring for physical faults, while the distributed ET-UI observers ensure network-wide monitoring for cyber-attacks. Their concurrent operation, as coordinated in Algorithm 1, creates a layered defense that is resilient to a wider range of anomalies than a single observer could achieve. This is empirically validated in Scenarios 1 and 2 of the Simulation Results.

Simulation results

In this research, Simulink /Matlab simulations using the specialised power systems toolbox are used to realise the MG topology shown in Fig. 1 and the recommended design. Furthermore, in these simulations, the power lines that allow the physical connection of the DGUs are treated as resistive-inductive, the source voltage \(V_{si} = 90V, \forall i \in {\mathcal{M}}\) is set to 10 kHz, and the frequency of operation for the bidirectional buck converters—which make use of non-ideal insulated gate bipolar transistor (IGBT) switches—is set to 10 kHz. Reference48 is the source of the parameter values for the principal controllers and electrical components. Currents are measured in amperes, and voltages are measured in volts. It should be noted that, in compliance with Assumption 3, the values of the process and measurement noises are limited by upper bounds \(\overline{w}_{i} = \left[ {0.05,0.05,0.01} \right]^{T} ,\)\(\overline{\upsilon }_{i} = \left[ {0.01, 0.01,0} \right]^{T} , \forall i \in {\mathcal{M}}\), and that model mismatch is likewise expressed as process noise \(w_{i} , \forall i \in {\mathcal{M}}\).

In this section, three attack scenarios will be discussed to illustrate the interaction between the two modules \(d_{i}\). In the first scenario, the implementation of CAs on \(y_{45}^{c} , y_{43}^{c}\) is such that it is not detectable to the observer of the ET-\({\mathcal{H}}_{\infty }\). Also, in the second scenario, a stealthy CA on \(y_{45}^{c}\) occurs. In the third scenario, an FDIA occurs with the occurrence of a fault in the LSS system.

For the first and second scenarios, the simulation unfolds in the following way. At time \(t = 0s\), all DGUs are activated as standalone systems with a constant voltage reference \(V_{ref} = 60V\) for the primary controllers, while the secondary controllers remain dormant. As shown in Fig. 1, at time \(t = 3s\), the DGUs are connected to the secondary controllers by RL power lines and operational communication links (i.e., untouched by CAs). Therefore, at this stage, the LSS subsystems share current and balance voltage with the secondary controllers activated. Finally, the corresponding communication channels are cyber-attacked at \(t = 10s\).

Scenario 1: secret FDIA to \({{\varvec{O}}}^{{\varvec{E}}{\varvec{T}}-{\mathcal{H}}_{\boldsymbol{\infty }}}\)

In the initial scenario, constant bias injection attacks are launched against specific communication links \(y_{43}^{c} \left( t \right)\) and \(y_{45}^{c} \left( t \right)\), with the elements of the attack vector \(\phi_{42}^{bi}\) and \(\phi_{45}^{bi}\) (excluding the fourth element \(\phi_{{43_{4} }}^{bi}\)) being randomly drawn from a uniform distribution within a specified interval, while the fourth element of the attack vector \(\phi_{43}^{bi}\) is selected to remain confidential as \(\phi_{{43_{4} }}^{bi} = - \frac{{R_{34} }}{{R_{54} }}\phi_{45}^{bi}\). In particular, the fixed attack vectors

For the ET-\({\mathcal{H}}_{\infty }\) on DGU 4, Fig. 3 shows the residuals and thresholds associated with the observer-based module, and for the \(y_{4j}^{c} \left( t \right), j \in \left\{ {5,3} \right\}\) relationship, Figs. 4 and 5 show the ET-UI estimator-based modules. Furthermore, the attack’s start is indicated by the black vertical dashed lines in both figures. i.e. \(T_{a}^{45} = T_{a}^{43} = 10s\), while the green lines indicate the detection time for the corresponding module. As shown in Fig. 3, by appropriately choosing the attack vectors \(\varphi_{45}^{bi}\) and \(\varphi_{43}^{bi}\), the attacker can make the impact of the attack on the residual observer of the ET-\({\mathcal{H}}_{\infty }\) very insignificant, so that it remains hidden from the observer and is not detected. The residuals from the estimator that monitors ET-UI across both communication links are influenced by the attack, resulting in a breach of Eq. (6) for \(\left( {j, i} \right) = (5,4)\) and \(\left( {j, i} \right) = \left( {3,4} \right)\). This, in turn, triggers the identification of CAs in both modules at the times marked as \(T_{d}^{45} = 10.47s, T_{d}^{43} = 10.03s\).

Scenario 2—stealthy attack

In the second scenario, a stealthy attack \(\phi_{45}^{c}\) initiated against \(y_{45}^{c} (t)\), featuring the subsequent dynamics.

By choosing the appropriate inputs \(D_{2}^{a}\), the attacker can change the state dynamics of the impacted system so that it acts as though DGU 5 were isolated from the rest of the MG. This means that dynamics of \(x_{2}\) are independent of both its neighboring states and the secondary consensus input \(\Delta V_{5}\). Additionally, by changing the operating point \(x_{2}^{a}\) as opposed to \(x_{2}\), this choice causes a change in the load current \(I_{L5}^{a}\) (more precisely, \({\Delta }I_{L5} = 2A\)). Figure 6 shows the ET-UI distributed estimator modules for the \(y_{45}^{c} \left( t \right)\) connection as well as the ET-\({\mathcal{H}}_{\infty }\) observer module’s residuals and thresholds associated with the second attack scenario with respect to DGU 4.

The ET-UI distributed estimator-based detection module is not capable of detecting the attack designed in this scenario due to the compliance with Eq. (80). This is illustrated in Fig. 6 (images on the right), where the module’s residual remains consistent when the attack begins. However, the impact of the CA is rapidly revealed and identified at time \(T_{d}^{4} = 10.01s\) by the residue of the ET-\({\mathcal{H}}_{\infty }\) observer module.

Scenario three—FDIA occurrence and fault in LSS system

At each edge, the attack characteristic is set to \(\overline{\phi } = 0.1\), and the likelihood of FDIA occurrence is selected as \(\xi_{12} = \xi_{24} = \xi_{34} = \xi_{56} = 0.02\), \(\xi_{16} = \xi_{45} = \xi_{13} = 0.03\).

Initially, it will be shown that the consensus control mechanism of Eqs. (30), (31) and (32) is functional.

According to Theorems 2 and 3, the parameters \({\mathcal{Q}}_{1} = 200,\,\pi = 0.08,\)\(\pi_{1} = 0.1, \pi_{2} = 60, \pi_{3} = 0.85,\)\(R = I_{2} ,{\mathfrak{X}} = 0.00005,\) \(\aleph = 0.387\) and the initiator parameters \({\mathcal{Q}}_{2} = 0.0034, \pi_{4} = 1,\)\(\hbar_{i} = 0.003, \imath = 0.00001\) are chosen.

Equations (37)–(38) and (48)–(49) are solved, and the weight matrix \(J_{2}\), controller gain \({\mathcal{Q}}\), disturbance bound estimation gain matrix \(W_{1}\), and observer gain L are determined.

Figure 7 illustrates the instances when the information transmitted across various edges is subjected to FDIA attacks. The moments created by the event and the information transmission intervals by various MGs are displayed in Fig. 8, which demonstrates how the suggested ETM of Eq. (46) can prevent Zeno behavior and conserve communication resources. Overall, the proposed approach has a small number of trigger points, leading to a reduction in communication load while maintaining system performance without detrimental effects.

The effectiveness of the suggested FD method, which is provided by Eqs. (71) and (72) in the following, is examined. The parameter matrix \(F\) is chosen as \(F = \left[ {1,0.3, - 1.4} \right]^{T}\) in Eq. (66). In addition, choose \(\pi_{5} = 0.1, \pi_{6} = 0.2,\pi_{7} = 0.004,R_{1} = I_{2} ,{\mathcal{Q}}_{3} = 120\). Then the parameter matrices \(J_{3}\) and \(W_{2}\) are calculated by solving the LMIs of Eqs. (78)–(79).

As shown below, it is assumed that faults \(f_{1} \left( t \right)\) and \(f_{5} \left( t \right)\) occur in MGs 1 and 5, respectively, for the purposes of fault identification.

Figure 9 shows the AT \(G_{{th_{i} }} \left( t \right)\) and residual functions \(G_{{r_{i} }} \left( t \right)\) for different MGs. It is evident that a fault in MG 1 is identified at 8.0556 s, while no faults are noted in the remaining MGs of the LSS system, allowing us to conclude that the fault originated in MG 1. Additionally, for \(t>15.0032 s\), the residual function falls below the AT, indicating that MG 1 is free of faults. Likewise, a fault in MG 5 is detected at 18.045 s, with no faults reported in the other LSS subsystems. This figure demonstrates how well the ET-based FD mechanism, which employs the AT design method, has performed in detecting fault occurrences with high accuracy even when there are external disturbances and FDIA present. As a result, the suggested defect detection mechanism’s efficiency and speed are verified.

Monte Carlo analysis for robustness validation