Abstract

Accurate and efficient detection of landslide hazards is recognized as a critical requirement for both disaster emergency response and long-term land-use planning. However, conventional semantic segmentation models still present notable limitations when processing high-resolution remote sensing imagery, such as imprecise delineation of landslide boundaries and low performance in detecting small-scale landslides, often resulting in missed or false detections. To address these challenges, this study proposes FCA-DeepLab, a novel landslide detection model based on multimodal data fusion and an improved DeepLabv3 + architecture. The model integrates a multimodal fusion mechanism to achieve deep coupling of optical imagery and topographic features, thereby fully exploiting both visual and geomorphological contextual information related to landslides. Moreover, the conventional ResNet backbone is replaced with a ConvNeXt network employing 7 × 7 convolutional kernels, which substantially enlarges the receptive field and improves the ability to capture fine-grained features. A small‑object attention mechanism specifically designed for small targets is introduced to enhance sensitivity to subtle landslide characteristics and markedly reduce the missed detection rate. Comparative experiments on several public datasets demonstrate that FCA-DeepLab surpasses established semantic segmentation models such as UNet, Swin Transformer, SegFormer, and the original DeepLabv3 + in terms of overall accuracy, recall, and qualitative segmentation performance. Furthermore, additional evaluation on the Bijie landslide dataset confirms the model’s strong generalization capability, showing adaptability to diverse regions, complex terrains, and varied scenarios. These findings substantiate the proposed method’s significant advantages in improving detection accuracy, reducing false positives, and strengthening the identification of small-scale landslides, thereby providing a reliable technical reference for deep learning-based intelligent landslide detection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Landslides, as one of the most frequent natural disasters globally, exhibit high destructiveness to surrounding environments and predominantly occur in mountainous, hilly, and plateau regions1,2,3,4. Worldwide, landslide disasters cause substantial casualties and property losses each year5. Against the backdrop of ongoing global climate change and intensified human engineering activities. The steep terrain, complex geological conditions, and harsh environment of the upper Yellow River region in China further exacerbate the frequency and destructive impact of landslides in this area6. Consequently, there is an urgent need to develop rapid and intelligent landslide detection methods for the upper Yellow River region to enhance the intelligence and effectiveness of disaster prevention and mitigation strategies.

Traditional landslide detection methods primarily depend on field surveys, which are constrained by limited spatial coverage, high time consumption, labor intensity, and low efficiency, often failing to satisfy the demands of emergency response departments7,8. In recent years, the rapid advancement of remote sensing technologies and computer science has promoted the development of novel approaches for landslide detection9. Current methodologies can be broadly categorized into four types: visual interpretation, change detection, machine learning, and deep learning methods10,11.

The visual interpretation method relies on analyzing the texture and geometric features of landslides in remote sensing imagery to delineate landslide boundaries12. For instance, Lv et al. proposed an automatic adaptive region-growing algorithm based on very high-resolution (VHR) remote sensing images. Through experiments conducted at two distinct landslide sites on Lantau Island, Hong Kong, China, using VHR remote sensing imagery, the effectiveness and advantages of the proposed method were demonstrated13. Additionally, Lv et al. introduced a landslide inventory mapping method based on adaptive regional spatial–spectral similarity for automatically identifying landslide areas from bi-temporal remote sensing images. This approach begins by adaptively extracting spectrally homogeneous regions around each pixel to leverage spatial contextual information. Subsequently, a shape description algorithm is proposed to construct shape descriptor vectors for quantifying spatial structural differences between regions. Finally, by integrating shape vectors with regional brightness information, a spatial–spectral similarity measure is constructed to generate a change intensity map, which is then binarized using the Otsu threshold method to produce a landslide distribution map. Experimental results indicate that, compared with eight existing methods across four real-world landslide datasets, the proposed method achieves superior performance in both qualitative visualization and quantitative metrics (such as overall accuracy), demonstrating its suitability for practical landslide detection tasks14. Although change detection methods based on bi-temporal remote sensing imagery can capture landslide regions by analyzing pixel-level changes, their performance relies heavily on high-precision remote sensing data; for lower-resolution images, the results may exhibit substantial errors.

The change detection method compares multi-temporal remote sensing images of landslide-prone areas to extract information on surface morphological changes, thereby assessing landslide occurrence and evolution15,16. While this method enables long-term time-series monitoring and captures dynamic processes of landslides, it is prone to geometric distortions in areas with significant topographic relief, often causing inaccuracies in characterizing surface changes in complex mountainous terrain.

Machine learning methods utilize powerful feature extraction and pattern recognition capabilities to learn nonlinear landslide characteristics from training data, thereby enhancing the detection of landslides with subtle changes17,18. Commonly used machine learning algorithms in landslide identification include Decision Tree, Random Forest, Support Vector Machines, and Gradient Boosted Regression Tree19,20,21. By comprehensively analyzing topographic, morphological, spectral, and textural features of landslides in remote sensing imagery, machine learning algorithms markedly enhance identification capabilities and greatly improve efficiency compared to manual visual interpretation22,23. Nonetheless, these models require the automatic extraction of numerous salient features from training data and still encounter limitations when dealing with highly complex and heterogeneous characteristics, thus constraining their performance in landslide detection tasks24.

Deep learning, a subfield of machine learning, has achieved remarkable progress alongside the rapid rise of artificial intelligence25. Compared with traditional machine learning, deep learning models offer the advantage of deeper network architectures and eliminate the need for manual feature engineering, enabling them to process large-scale datasets and making them particularly suitable for wide-area landslide detection tasks26. Moreover, deep learning facilitates end-to-end extraction of semantic features from low-level to high-level representations, allowing it to automatically distill useful information from complex data. At present, deep learning methods for landslide detection can be grouped into two main approaches: object detection and semantic segmentation27,28.

Object detection primarily locates landslide areas by assigning class labels and generating bounding boxes, with the Faster R-CNN and YOLO series being the most widely adopted algorithms29,30. Numerous researchers have achieved notable results in landslide detection using these methods. For example, Yang et al. proposed a lightweight attention-guided YOLO with a horizontal scaling layer for landslide detection. Their approach replaces the original YOLO backbone with MobileNetv3 and employs a lightweight pyramidal feature reuse and fusion attention mechanism to improve detection performance31. Ding et al. introduced Deformable Adaptive Focusing YOLO (DAF-YOLO), which incorporates an Enhanced Deformable Convolutional Network (EDCN) to improve recognition of anomalous landslides, a lightweight sliding-window attention mechanism to enhance background discrimination, and an adaptive zooming loss framework to reduce missed detections and false alarms32. Chandra et al. applied YOLO series algorithms to satellite and UAV imagery, concluding that YOLOv7 achieved an F1-score of 0.995, outperforming other YOLO variants33. Jin et al. proposed an Efficient Residual Channel-wise Soft Threshold Attention (ERCA) mechanism, which employs adaptive soft thresholding via deep learning to suppress background noise, thereby enhancing the feature learning capacity of Faster R-CNN. Incorporating ERCA into the Faster R-CNN backbone improved feature extraction and boosted landslide detection performance34. Although these studies demonstrate the potential of object detection algorithms for landslide identification, a fundamental limitation is their inability to perform pixel-level annotation, thereby preventing precise delineation of landslide boundaries.

Semantic segmentation technology, which performs pixel-wise classification of images, is widely used in AI applications such as autonomous driving and facial recognition. In landslide detection, semantic segmentation models can accurately delineate boundaries and separate landslides from background areas35. To improve accuracy, researchers have mainly focused on dataset enhancement and model refinement. Wang et al. employed RGB and LAB color correction for preprocessing to improve image quality, constructed a dataset integrating normal and anomalous images with features such as trees, roads, buildings, rivers, riverbanks, farmland, and landslide anomalies, and trained their model using the GANomaly framework36. Liu et al. proposed a complex background enhancement method based on multi-scale samples to improve data quality and conducted a comparative analysis using the Mask R-CNN model. Their results indicated that training with background-enhanced samples yielded higher precision across all metrics37. Ren et al. introduced ResM-FusionNet, a detection method that uses ResNet-50 as the backbone for feature extraction and integrates a multilayer perceptron as the decoder. Comparative experiments with SegFormer, DeepLabv3, and UNet demonstrated that ResM-FusionNet surpassed these models across all evaluation metrics26. Li proposed a lightweight landslide detection method based on DeepLabv3 + and a dual-attention mechanism. This approach replaces the Xception backbone with MobileNetv2 and incorporates dual attention with a lightweight convolutional attention module to accelerate training and improve feature extraction. The improved model achieved higher accuracy than the original DeepLabv3 + and outperformed classical models such as UNet, PSPNet, HRNet, and Swin Transformer in landslide identification38. Lin et al. proposed CBAM-U-net, a U-net with progressive convolutional attention modules, by integrating spatial and channel attention into each down-sampling stage. Comparative analysis against U-net, FCN, and DeepLabv3 + showed that CBAM-U-net achieved superior performance across all precision metrics39. Ghorbanzadeh et al. explored the feasibility of integrating deep learning models with object-based image analysis for landslide detection, concluding that the overall accuracy within an integrated framework surpasses that achieved by either approach individually40. Furthermore, Ghorbanzadeh et al. proposed a self-supervised learning method for landslide detection. Comparative experiments revealed that their method, utilizing only 10% of labeled data, outperformed competing models trained with 100% of the labeled data41. Kariminejad et al. employed unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology to acquire high-precision maps of the semi-arid Golestan Province in Iran. They trained UAV-derived datasets using DeepLab-v3+, Link-Net, MA-Net, PSP-Net, ResU-Net, and SQ-Net architectures, achieving high-accuracy detection of landslides and sinkholes in challenging environments42. Shahabi et al. developed an unsupervised learning model using a convolutional autoencoder (CAE) to address the issue of limited training data. Experiments demonstrated that their model achieved optimal accuracy in landslide detection tasks by clustering CAE-extracted deep features alongside slope and NDVI data43. Piralilou et al. combined object-based image analysis with multilayer perceptron neural networks, logistic regression, and random forests for landslide detection. They found that the overall accuracy was optimized when multi-scale results from each machine learning method were merged using Dempster–Shafer theory44. Kumar et al. proposed a landslide detection model based on an ensemble deep learning classifier. The method begins by preprocessing GIS images with Gabor filters, followed by the extraction of multiple features including texture, vegetation indices, and brightness. Subsequently, a novel hybrid optimization algorithm—combining Teamwork Optimization Algorithm (TOA) and Poverty and Rich Optimization (PRO)—is employed to select the optimal feature subset from the fused features. These optimal features are then fed into an ensemble classifier composed of Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM), and Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (Bi-GRU) for training and detection. The final result is obtained by averaging the outputs of the three models. Experimental results indicated that the ensemble model achieved a training accuracy of 87%, outperforming other comparative models. However, the authors noted that the method faces challenges related to time-consuming training data preparation and computational complexity45. Zhang et al. demonstrated that fusing DEM data with optical imagery enhanced model robustness and improved prediction reliability46. Furthermore, feature fusion through a dual-branch network achieved slightly higher accuracy than early fusion of RGB and DEM channels. Moreover, Saha et al. systematically elaborated on the extensive applications of deep learning-based multi-sensor earth observation technologies across numerous domains. By integrating data from diverse sensors (e.g., optical, SAR, LiDAR, hyperspectral) and combining them with deep learning models, it becomes possible to understand and monitor Earth’s dynamics more accurately and comprehensively47. Although the aforementioned studies have made notable progress in landslide detection and offered novel approaches for automated landslide identification, certain limitations remain.

To overcome the limitations of existing methods, this study introduces a novel landslide detection approach based on multimodal data fusion and an improved DeepLabv3 + model. Without altering the core network architecture of the original model, the contributions are as follows: First, a Multimodal Fusion module based on a dual-branch network is designed to integrate visual and topographic features, enhancing the feature extraction capacity. Additionally, the original decoder is improved through dual convolution for stronger fusion capacity and hierarchical regularization for greater robustness. This strengthens feature representation in boundary-sensitive regions, provides a high-quality feature foundation for edge refinement, and markedly improves boundary segmentation accuracy in complex scenarios while maintaining computational efficiency. Second, the original ResNet backbone is replaced with a ConvNeXt network, which employs larger convolutional kernels to substantially expand the receptive field and strengthen feature extraction. Finally, a Small Target Head with an attention module combining spatial and channel attention mechanisms is incorporated. This suppresses background noise and increases model sensitivity to small target regions through simultaneous spatial and channel attention.

Research area and datasets

Research area

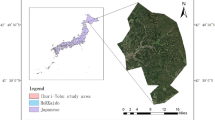

This study focuses on the upper Yellow River region, located at the border of Qinghai and Gansu Provinces (35°07′–36°42′ N, 99°59′–103°18′ E), as illustrated in Fig. 1. Situated on the southeastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau, the region is characterized by a typical alpine valley landform with an elevation range from 1,564 m to 4,951 m48. The pronounced topographic relief and steep slopes substantially influence slope stability. The area contains complex geological structures, active fault systems, and fragmented rock masses. These conditions, combined with sparse vegetation cover and extensive land desertification, intensify the instability of surface geomaterials49. Additionally, frequent human engineering activities in recent years have further disturbed natural slopes, increasing the likelihood of landslide hazards50,51.

Located within the intense tectonic zone of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, the complex geological structure exhibits high instability under the coupled effects of strong seismic activity and frequent freeze–thaw cycles. Furthermore, the harsh high-altitude, hypoxic environment and the vast, inaccessible terrain pose significant challenges for the deployment and maintenance of conventional monitoring equipment, while remote sensing techniques are often limited by vegetation and snow cover. Compounded by a scarcity of fundamental geological data and extreme logistical difficulties, field investigations and risk assessments are severely hampered. Consequently, this has led to the formation of a systemic problem—unique to the fragile plateau environment—that is far more complex, from genetic mechanisms to monitoring and early-warning, than those encountered in other regions worldwide. Given the limitations of field investigations, the development of efficient and accurate computer vision algorithms for automatic landslide identification and risk assessment is of significant scientific value and practical importance for strengthening regional geological disaster prevention and control.

Overview of research area. Map created using ArcGIS 10.8 (https://www.esri.com).

Datasets

This study utilized 2-m resolution Gaofen-6 (GF-6) satellite imagery and SRTM DEM data released by NASA to construct a landslide dataset for the study area through manual visual interpretation. Due to constraints in GF-6 acquisition timing, only single-temporal imagery from January 2025 was used, thus lacking seasonal variability in landslide information. Furthermore, limitations inherent to single-view imagery produced shadow occlusion on certain north-facing slopes, leading to the omission of a small number of landslides. Ultimately, 257 landslides were identified and mapped; their spatial distribution is shown in Fig. 1.

The remote sensing characteristics of representative landslides in the study area are depicted in Fig. 2. Landslides differ markedly from their surrounding environment in morphology, tone, texture, and vegetation cover. In vegetated areas, landslide features are particularly distinct (Fig. 2a-e). In sparsely vegetated regions, identification relies on subtle geomorphological features such as slip scars, tonal contrasts on slopes, and the presence of “twin gullies with a common source,” as shown in Fig. 2f-h. Additionally, small landslides in the study area often appear as targets smaller than 50 × 50 pixels in the 2 m GF-6 imagery, yet they typically exhibit a clear tonal contrast against the background. For identifying such small landslides, 3D topographic information from Google Earth was used as auxiliary verification, as demonstrated in Fig. 2i-j.

During data processing, the 30 m resolution SRTM DEM data were first upsampled to 2 m to match the GF-6 imagery. Images containing landslide areas were then cropped into 512 × 512 pixel samples, and landslide boundaries were annotated using the LabelMe tool. To overcome the limited number of landslide samples, data augmentation techniques—including rotation, flipping, and color enhancement—were applied to expand the dataset, ultimately yielding 2,672 landslide samples. Finally, the augmented dataset was randomly divided into training, validation, and test subsets in an 8:1:1 ratio. This resulted in 2,130 samples allocated to the training set, with the validation and test sets each containing 271 landslide samples.

Some landslides in the study area. a-e illustrate landslides with sparse vegetation cover; f-h show double-gullied homologous landslides; i-j depict small-scale landslides. Map created using ArcGIS 10.8 (https://www.esri.com).

Methods

DeepLabv3 + model

DeepLabv3+, introduced by Google in 2018, is a classical semantic segmentation model52. The architecture adopts an encoder-decoder structure, in which the encoder is strengthened by an Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) module for semantic enrichment, while the decoder is employed for pixel-wise prediction53.

In the DeepLabv3 + framework, the encoder typically integrates a backbone network, such as ResNet or Xception, with the ASPP module54. The backbone functions as a strong feature extractor, hierarchically capturing multi-scale semantic features from the input55. The ASPP module enlarges the receptive field by applying convolutions with different dilation rates, thereby acquiring multi-scale contextual information56. Moreover, multiple convolutional layers within the encoder progressively reduce the spatial resolution of feature maps through convolution and pooling while simultaneously increasing channel depth. This compresses image features and facilitates high-level semantic extraction57.

The decoder produces precise segmentation by fusing hierarchical features from the encoder58. First, a 1 × 1 convolution is used to adjust the channel depth of deep encoder features to match shallow features. The deep features are then upsampled via bilinear interpolation to align spatial resolution with shallow features, followed by channel-wise concatenation for integration. The fused features are refined through 3 × 3 convolutions to enhance feature representation and discriminative ability. Finally, features are upsampled to the input image resolution, and a 1 × 1 convolutional classifier performs per-pixel classification. This design, combining hierarchical feature fusion and progressive upsampling, leverages semantic guidance from deep features and spatial details from shallow features. It reduces spatial information loss caused by pooling and strides, thereby significantly improving segmentation accuracy, particularly along object boundaries59,60,61,62. The flowchart of the DeepLabv3 + model is shown in Fig. 3.

Improved DeepLabv3 + model

Multimodal fusion

Conventional approaches typically use only RGB imagery as input, or combine RGB with DEM through simple band stacking into a four-channel input. Such strategies often fail to fully capture critical topographic information embedded in the DEM. To better exploit multi-source characteristics, this study designs a dual-branch network to process RGB and DEM data separately. A spatial-channel attention fusion module is then employed to integrate spectral and topographic features effectively, with the fused features serving as input to the model.

The Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM), as a lightweight attention mechanism, is not only easily integrable into mainstream convolutional neural networks but also incurs nearly negligible computational overhead. It innovatively combines the outputs of both max pooling and average pooling operations to generate attention weights across two critical dimensions: channel and space. This enables the network to dynamically concentrate on more salient features. The detailed architecture of the CBAM module is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Within the CBAM framework, the input feature map \(\:F\) is first modulated by the channel attention mechanism, producing an intermediate feature representation \(\:{F}_{1}\). This output is subsequently processed by the spatial attention module to obtain further refined features, thereby forming a sequentially connected cascaded structure. The overall process can be formally expressed by Eq. 1 as follows63:

In Eq. (1), \(\:{M}_{c}\left(F\right)\) denotes the output weight matrix from the channel attention mechanism applied to the input feature map \(\:F\); \(\:{M}_{s}\left({F}_{1}\right)\) represents the output weight matrix generated by the spatial attention mechanism from the intermediate feature ma \(\:{F}_{1}\); and the operator \(\:\otimes\:\) indicates the element-wise multiplication—a weighting operation—between the corresponding feature maps.

ConvNeXt network

Traditional DeepLabv3 + architectures usually employ ResNet or Xception as the backbone. In this study, the ConvNeXt network, characterized by a large-kernel design, is adopted as the backbone. Inspired by the Vision Transformer (ViT), ConvNeXt introduces Transformer design concepts into convolutional networks64. Its refinements include: (1) a stem layer using a 4 × 4 convolution with a large stride for efficient downsampling; (2) inverted bottleneck blocks with 7 × 7 depthwise separable convolutions, expanding the receptive field and strengthening feature extraction; (3) adoption of the Gaussian Error Linear Unit (GELU) activation, which provides smoothness, non-zero negative gradients, and input-dependent probabilistic gating, offering superior representational capacity over ReLU; and (4) the use of LayerNorm in place of BatchNorm, with one LayerNorm layer retained per residual block65. The overall ConvNeXt architecture is shown in Fig. 5.

Small-object attention mechanism

Some landslides in the study area are small targets (smaller than 50 × 50 pixels). To improve detection accuracy for such objects, a small‑object attention mechanism is introduced, equipped with a spatial-channel attention mechanism applied to low-level features of the backbone. This mechanism suppresses background noise and enhances feature representation of small objects, providing high-quality edge cues for boundary refinement.

In summary, compared to the conventional DeepLabv3+, the improved model introduces optimizations in three aspects: input data, backbone feature extraction, and boundary refinement. The overall workflow is presented in Fig. 6.

Model evaluation

To quantitatively assess the performance of the improved DeepLabv3 + model, five common metrics are used: Precision, Accuracy, Recall, F1-Score, and Intersection over Union (IoU).

Precision refers to the proportion of correctly identified landslide samples among all samples predicted as landslides66:

Accuracy is defined as the proportion of correctly predicted samples among all samples67:

Recall measures the proportion of correctly predicted landslide samples among all actual landslide samples68:

The F1-Score, the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, evaluates both precision and completeness69:

Intersection over Union (IoU) is calculated as the ratio of the intersection area between predicted and ground truth regions to the area of their union70:

In Eqs. (2)–(6), TP (True Positive) denotes cases where the model correctly predicts a sample as a landslide; TN (True Negative) refers to samples that are correctly predicted as non-landslide; FP (False Positive) indicates cases where the model incorrectly predicts a sample as a landslide; and FN (False Negative) represents samples that are incorrectly predicted as non-landslide.

Results

Experimental environment

The experimental configuration adopted in this study was as follows. The hardware platform comprised an Intel i9-13900HX CPU and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 GPU with 8 GB of RAM. The software environment was built on the Python programming language, with the PyTorch framework used to construct and train the deep neural network model. During training, the Adam optimizer was employed with a weight decay coefficient of 0.001. The initial learning rate was set to 0.0001 and decayed using a cosine annealing strategy. Owing to the memory limitations of the GPU, the batch size was determined to be 4 after testing, representing the maximum value sustainable for stable operation on the available hardware. Regarding the training duration, the maximum number of epochs was initially set to 500, providing ample redundancy for model convergence. To effectively mitigate overfitting and conserve computational resources, an early stopping strategy was implemented. Based on observed performance fluctuations on the validation set, training was terminated if the performance improvement remained below a threshold of 0.0001 for 30 consecutive epochs. This combination of “patience value” and threshold allows for the timely detection of convergence while preventing premature termination due to short-term fluctuations. Furthermore, a warm-up phase of 50 epochs was established, during which the early stopping mechanism was disabled, ensuring that the model could develop preliminary learning capacity without premature intervention.

The detailed configurations of the comparative models are described below. Specifically, the UNet model was configured with a four-layer deep encoder and optimized using the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.001. The DeepLabv3 + model utilized a ResNet101 backbone as its feature extraction network, also employed the Adam optimizer, and was set with an initial learning rate of 0.001. The Swin Transformer model was trained using the AdamW optimizer, with an initial learning rate of 0.0001 and a weight decay coefficient of 0.01. The SegFormer model, incorporating a MiT-B5 encoder structure, adopted the AdamW optimizer, an initial learning rate of 0.0001, and a weight decay of 0.001. The HRNet model utilized Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) as its optimization method, with an initial learning rate of 0.01. The Fast-SCNN model employed the Adam optimizer with its initial learning rate set to 0.001.

Comparative experiments

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed FCA-DeepLab model for landslide identification, comparative experiments were conducted against several widely used semantic segmentation models: UNet, Swin Transformer, SegFormer, HRNet, Fast-SCNN, and the original DeepLabv3+. As presented in Table 1, all seven models achieved landslide detection accuracy above 0.8, indicating competent recognition capability. Comparative results across seven evaluation metrics showed that the proposed model outperformed the others in landslide identification accuracy. Specifically, FCA-DeepLab achieved an Accuracy of 0.912 and an IoU of 81.8%, representing improvements of 0.057 and 5.3%, respectively, over the original DeepLabv3+, and surpassing the other models by at least 0.037 and 2.9%. Moreover, the model attained Precision, Recall, and F1-Score values of 0.865, 0.870, and 0.867, respectively—gains of 0.055, 0.055, and 0.054 over the baseline DeepLabv3+.

The superior performance of the proposed model is primarily attributed to the multimodal fusion mechanism introduced in the FCA-DeepLab architecture. By employing a dual-branch network to process DEM and RGB data in parallel and integrating a spatial-channel attention fusion module, the model effectively combines topographic and spectral features to derive more discriminative representations. These enhanced features are further processed by the ConvNeXt backbone, which applies 7 × 7 convolutional kernels to improve feature extraction. In addition, the incorporated small-target detection head leverages a spatial-channel attention mechanism to retain spatial details from low-level features—such as edges, textures, and the precise contours of small objects—thereby addressing the common problem of overlooked small targets.

Figure 7 illustrates the detection results of the different models on the test set. While all models exhibit varying degrees of false positives and false negatives, each demonstrates the ability to delineate landslide boundaries when spectral contrast with the background is strong. However, UNet, Swin Transformer, SegFormer, HRNet, Fast-SCNN, and the original DeepLabv3 + showed relatively weaker extraction performance, with more pronounced misclassification and omission errors. In contrast, FCA-DeepLab produced fewer such errors, particularly excelling in small-target detection where it achieved clearer boundary delineation. This demonstrates that the specialized small-target detection head significantly improves sensitivity to subtle features, enhancing segmentation performance for small-scale landslides.

In summary, the proposed FCA-DeepLab model surpasses the other four models in both quantitative metrics and qualitative segmentation results. These findings confirm that the introduced modifications effectively enhance boundary processing capability, enabling more accurate delineation and prediction of landslide boundaries, which is vital for efficient and reliable landslide monitoring.

Ablation experiments

To systematically assess the contribution of each innovative component in the proposed FCA-DeepLab model, a comprehensive ablation study was conducted. This study aimed to isolate and evaluate the impact of individual modules on overall performance, thereby clarifying their functional significance. The experiments focused on three aspects: first, excluding the multimodal fusion mechanism to examine its role in integrating spectral and topographic information; second, replacing the ConvNeXt backbone with the original ResNet101 to compare their relative effectiveness; and third, removing the small‑object attention mechanism to assess its influence on the segmentation accuracy of small landslide boundaries.

Quantitative results, including Intersection over Union (IoU) and F1-Score, are summarized in Table 2. For more intuitive interpretation, visualizations of prediction outcomes on the test set are also provided, enabling direct comparison of model performance across different configurations, as shown in Fig. 8.

From the quantitative metrics presented in the table, a decline in all evaluation indicators is evident when the model operates without the multimodal fusion mechanism, resulting in performance that is slightly inferior to that of the complete improved model incorporating this module. This outcome preliminarily confirms the necessity of multimodal information fusion. More importantly, visual comparative analysis of the prediction maps reveals that the model lacking topographic feature assistance shows a strong tendency for confusion when processing non-landslide backgrounds with spectral characteristics similar to those of landslides (e.g., exposed rock or certain vegetation covers). This appears as a higher incidence of misclassifying such background pixels as landslides, thereby increasing the false positive rate. These observations clearly demonstrate that the introduced multimodal fusion mechanism effectively exploits topographic information (e.g., elevation, slope) as discriminative cues, significantly reducing the model’s over-reliance on spectral features alone and enabling more accurate distinction between landslides and confusing backgrounds in complex terrain.

For the backbone network comparison, ResNet101 was employed as a baseline. While the ResNet101-based model achieved acceptable overall accuracy, it did not demonstrate a distinct advantage over the improved model with the ConvNeXt backbone. Their recall rates, reflecting the ability to capture landslides, were generally comparable. However, qualitative analysis reveals clear differences: segmentation results from the ConvNeXt backbone produced more refined and accurate boundary extraction, with clearer and better-adhered contours. This suggests that the ConvNeXt network, through its larger kernel design and modernized architecture, enhances feature extraction and contextual representation, particularly in boundary determination. As a result, it delivers segmentation outcomes with superior boundary precision, even if the improvement is not fully reflected in overall pixel-level accuracy metrics.

The ablation experiment targeting the small‑object attention mechanism shows that its removal does not cause a dramatic decrease in overall accuracy metrics, similar to the trends observed in the other two ablation tests. Nevertheless, targeted case comparisons highlight its crucial role: the module significantly enhances sensitivity to small-scale landslides, improving the completeness and clarity of their boundary segmentation. For medium-to-large landslides, however, the addition of this module does not markedly alter boundary performance. This indicates that the small-target module functions as a specialized component, with its primary contribution being the optimization of segmentation detail for small-scale features. It compensates for the limitations of standard segmentation models in handling scale variation and improves the overall adaptability and fine-detail recognition capacity of the model across landslides of varying sizes.

The combined results of the three ablation experiments demonstrate that each innovative component contributes to performance enhancement and that they operate synergistically to improve comprehensive accuracy and robustness across diverse conditions. In summary, the core contributions of this study—the multimodal fusion mechanism, the ConvNeXt backbone, and the small-target detection module—complement one another by strengthening feature fusion, feature extraction, and detail optimization, respectively, thereby enhancing both accuracy and reliability in landslide identification.

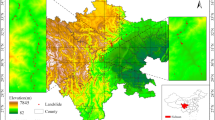

Generalization experiment

To further assess the generalization ability of the improved model, it was tested on a publicly available landslide dataset of Bijie City, Guizhou Province, China, released by Wuhan University71. A key distinction between the datasets lies in landslide types: those in the upper Yellow River region are predominantly loess landslides, while those in Bijie City are largely vegetation-covered. Their spectral characteristics in optical imagery, and their contrast with the background, differ considerably between the two regions. Thus, testing on the Bijie City dataset effectively validates the generalization performance of the improved model.

Table 3 presents the accuracy results of the improved model trained on the Bijie dataset. The extraction accuracy for Bijie landslides is comparable to that obtained in the primary study area, indicating strong generalization and promising potential for wider application.

Figure 9 illustrates the predictive performance of the model on selected Bijie City samples, highlighting results across three representative land cover types. In Fig. 9 (a), where the landslide is surrounded by man-made features such as roads and buildings, the model accurately distinguishes the landslide body from artificial structures, with no misclassification of urban features. This demonstrates strong resistance to interference in complex built environments. Figure 9 (b) displays detection results for a series of small landslides. Such targets are often difficult to identify due to their scale and inconspicuous features. The model nevertheless maintains high sensitivity, delineating their boundaries with relative completeness. Figure 9 (c) shows a vegetated area. Despite spectral convergence between landslides and vegetation, the model correctly captures the landslide distribution without major omissions, highlighting robustness under vegetation interference.

However, certain limitations remain in precise boundary reconstruction. Some delineated edges show serrated irregularities or localized blurring, suggesting that the model’s capacity for fine-grained edge restoration still requires improvement. Future research will focus on optimizing the boundary regression strategy to further enhance the geometric fidelity of segmentation results.

Discussions

Some extraction results of the Bijie landslide. (a) corresponds to landslides adjacent to buildings, roads, and bare rock edges; (b) corresponds to small-scale landslides; (c) corresponds to vegetation-covered landslides. Map created using Python 3.9 (https://www.python.org).

This study addresses major challenges in landslide detection under complex environments, including the omission of small targets and limitations in feature extraction, by proposing a method that fuses topographic data and optical imagery with an improved DeepLabv3 + model. Through systematic integration of three key modules—multimodal feature fusion, backbone optimization, and small-target detection—the approach achieves significant performance gains. A comprehensive discussion of the findings is presented below.

Innovation and effectiveness of the method

The core innovations of this research are reflected in three aspects. First, the dual-branch multimodal feature fusion module effectively bridges the modality gap between optical imagery and topographic characteristics. By applying deep feature fusion instead of simple input-level stacking, the model learns stronger correlations between visual and terrain features. This substantially enhances discrimination between spectrally similar surfaces. In the loess landslide zones of the upper Yellow River region, where landslides often occur among exposed rock and soil, visual features alone are insufficient. Experiments confirm that the multimodal module significantly improves accuracy in confusion-prone bare rock areas.

Second, replacing the original ResNet backbone with the ConvNeXt network provides a critical enhancement. Its use of 7 × 7 convolutional kernels and redesigned architecture expands the receptive field and captures broader contextual information. This is particularly important for landslide detection, where spatially extensive features require context-rich representation.

Finally, the added small-target detection head with a spatial-channel attention mechanism enables the model to adaptively focus on small-scale regions. This considerably improves detection of small landslides and enhances precision in boundary segmentation.

Compared with existing research

The findings are consistent with existing research trends while offering measurable improvements. While existing studies generally recognize the importance of integrating optical imagery and topographic data for enhancing landslide identification accuracy, conventional methods predominantly rely on input-level fusion—such as simply combining DEM with RGB imagery—which often fails to adequately capture deep inter-modal correlations. For instance, Lu et al. proposed a dual-encoder U-Net model that incorporates a hierarchical design to integrate optical and DEM-derived deep features, successfully detecting specific landslides. However, the reported landslide detection accuracy of this method was only 0.78410. Similarly, Li et al. introduced a DemDet network, which employs an attention-based neural network to integrate DEM, hillshade, and optical imagery for identifying forested landslides in the Jiuzhaigou earthquake-affected area. Their results indicated a detection accuracy of only 0.800 in specific regions72. By contrast, the dual-branch fusion mechanism in this study achieves feature-level integration. The spatial-channel attention modules strengthen interaction between spectral and topographic features, effectively reducing false positives caused by spectrally similar surfaces like bare soil or roads. This underscores the advantage of deep fusion over basic stacking. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method achieved a landslide detection accuracy exceeding 0.830 across multiple datasets, including both our proprietary dataset and the external Bijie City landslide validation set, thereby confirming its effectiveness and reliability.

In addition, improvements targeting small-scale detection address a known weakness in existing semantic segmentation models. Methods such as DeepLabv3 + often prioritize large-scale feature extraction and neglect detailed representation of small targets, leading to omissions. While some studies introduced attention mechanisms, they are usually applied globally without a specialized focus. The dedicated small-target detection head in this study autonomously suppresses background noise and enhances feature responses in small regions. Ablation results confirm that this module markedly improves recall for small landslides, highlighting the value of modular designs tailored to specific challenges over general global adjustments.

Limitations and prospects

This study has limitations mainly linked to image acquisition and computational complexity. Regarding imagery, only single-temporal data from January 2025 were available, limiting representation of seasonal variations. In the upper Yellow River region, summer vegetation significantly alters landslide signatures compared to winter scenes. Furthermore, although experimental results demonstrate the improved model’s generalizability, it still exhibits insufficient temporal generalization. Consequently, subsequent work should prioritize acquiring images from other seasons (such as summer and autumn) to enable the model to fully learn from landslides with diverse visual features, thereby enhancing its adaptability to seasonal variations and different surface cover conditions.

Regarding the model, ConvNeXt with large kernels improves feature extraction but increases training time by about 75% compared with the original version. Model performance is also partly dependent on image resolution. While 2 m GF-6 imagery was used here, statistical analysis indicates that small landslides account for about 35% of events in the study area, and their reliable detection may require even finer-resolution data. Therefore, to address challenges such as extended training times, future work should explore the adoption of mixed-precision training and multi-GPU data parallelism techniques. These approaches would fully leverage the computational capabilities of modern hardware, significantly reducing the training cycle. Furthermore, efforts should be directed toward employing higher-resolution optical remote sensing imagery to investigate its impact on model performance and to further validate and extend the findings of this study.

Conclusions

This study proposes and validates an enhanced landslide detection method (FCA-DeepLab) based on an improved DeepLabv3 + architecture. The method achieves refined delineation of landslide boundaries and reliable identification of small-scale landslides in high-resolution remote sensing imagery. The principal conclusions are as follows:

(1) Multimodal Feature Fusion Module: A dual-branch network was used to process DEM and optical imagery in parallel. By leveraging spatial-channel attention for deep feature interaction, the module significantly enhances discrimination between spectrally similar surface features.

(2) ConvNeXt Backbone Network: Replacing the conventional ResNet with ConvNeXt, which employs large 7 × 7 kernels, expands the receptive field and strengthens contextual awareness, thereby improving the characterization of large-scale landslides.

(3) Small‑object attention mechanism: A specialized component with spatial-channel attention preserves low-level details, markedly improving recall for small-scale landslides and addressing omission problems common in conventional segmentation models.

The framework developed in this study provides a reliable tool for rapid and accurate landslide hazard monitoring while offering transferable insights for other remote sensing segmentation tasks. Future work should focus on integrating multi-temporal and multi-resolution datasets to capture seasonal variations and on optimizing efficiency through lightweight architectures, thereby enhancing practical deployment.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ge, X., Zhao, Q., Wang, B., Chen, M. & Lightweight landslide detection network for emergency scenarios. Remote Sens. 15, 1085 (2023).

Li, D., Tang, X., Tu, Z., Fang, C. & Ju, Y. Automatic detection of forested landslides: A case study in Jiuzhaigou County, China. Remote Sens. 15, 3850 (2023).

Fu, Y. et al. Conditional attention lightweight network for In-Orbit landslide detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 61, 4408515 (2023).

Li, B. & Li, J. Methods for landslide detection based on lightweight YOLOv4 convolutional neural network. Earth Sci. Inf. 15, 765–775 (2022).

He, L., Zhou, Y., Liu, Y., Zhang, Y. & Ma, J. Application of the YOLOv11-seg algorithm for AI-based landslide detection and recognition. Sci. Rep. 15, 12421 (2025).

Zhao, J. et al. Typical characteristics and causes of giant landslides in the upper reaches of the yellow River, China. Landslides 22, 313–334 (2025).

Liu, H., Duan, P., Li, J., Zhao, K. & Yu, X. Earthquake landslide detection method combining post-earthquake coherence increase and polarized vegetation damage. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk. 16 (1), 2492329 (2025).

Chen, Y. et al. Susceptibility-Guided landslide detection using fully convolutional neural network. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ Remote Sens. 16, 998–1018 (2022).

Wang, K., Han, L. & Liao, J. A study of high-resolution remote sensing image landslide detection with optimized anchor boxes and edge enhancement. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 57 (1), 2289616 (2023).

Lu, W., Hu, Y., Zhang, Z. & Cao, W. A dual-encoder U-Net for landslide detection using Sentinel-2 and DEM data. Landslides 20, 1975–1987 (2023).

Gao, S. et al. Optimal and Multi-View strategic hybrid deep learning for old landslide detection in the loess Plateau, Northwest China. Remote Sens. 16, 1362 (2024).

Fiorucci, F., Ardizzone, F., Mondini, A. C., Viero, A. & Guzzetti, F. Visual interpretation of stereoscopic NDVI satellite images to map rainfall-induced landslides. Landslides 16, 165–174 (2019).

Lv, Z., Liu, T., Wang, R. Y., Benediktsson, J. A. & Saha, S. Automatic landslide inventory mapping approach based on change detection technique with Very-High-Resolution images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 19, 6000805 (2022).

Lv, Z. et al. Spatial–Spectral similarity based on adaptive region for landslide inventory mapping with Remote-Sensed images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 62, 4405111 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. Identifying potential landslides by Stacking-InSAR in Southwestern China and its performance comparison with SBAS-InSAR. Remote Sens. 13, 3662 (2021).

Yao, J., Yao, X. & Liu, X. Landslide detection and mapping based on SBAS-InSAR and PS-InSAR: A case study in Gongjue County, Tibet, China. Remote Sens. 14, 4728 (2022).

Wang, H., Zhang, L., Yin, K., Luo, H. & Li, J. Landslide identification using machine learning. Geosci. Front. 12 (1), 351–364 (2021).

Wang, Z. & Brenning, A. Active-Learning approaches for landslide mapping using support vector machines. Remote Sens. 13, 2588 (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. Modelling of shallow landslides with machine learning algorithms. Geosci. Front. 12 (1), 385–393 (2021).

Meena, S. R. et al. Landslide detection in the Himalayas using machine learning algorithms and U-Net. Landslides 19, 1209–1229 (2022).

Zheng, X. et al. Comparison of machine learning methods for potential active landslide hazards identification with Multi-Source data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 10, 253 (2021).

Amatya, P., Kirschbaum, D., Stanley, T. & Tanyas, H. Landslide mapping using object-based image analysis and open source tools. Eng. Geol. 282, 106000 (2021).

Chen, F., Yu, B. & Li, B. A practical trial of landslide detection from single-temporal Landsat8 images using contour-based proposals and random forest: a case study of National Nepal. Landslides 15, 453–464 (2018).

Tang, X. et al. Federated learning for Privacy-Preserving collaborative landslide detection. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 21, 8003105 (2024).

Li, H. et al. Detection and segmentation of loess landslides via satellite images: a two-phase framework. Landslides 19, 673–686 (2022).

Ren, X. et al. ResM-FusionNet for efficient landslide detection algorithm with a hybrid architecture. Sci. Rep. 15, 13080 (2025).

Cheng, L., Li, J., Duan, P. & Wang, M. A small attentional YOLO model for landslide detection from satellite remote sensing images. Landslides 18, 2751–2765 (2021).

Fan, S., Fu, Y., Li, W., Bai, H. & Jiang, Y. ETGC2-net: an enhanced transformer and graph Convolution combined network for landslide detection. Nat. Hazards. 121, 135–160 (2025).

Cai, J. et al. Automatic identification of active landslides over wide areas from time-series InSAR measurements using faster RCNN. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs Geoinf. 124, 103516 (2023).

Hou, H., Chen, M., Tie, Y. & Li, W. A. Universal landslide detection method in optical remote sensing images based on improved YOLOX. Remote Sens. 14, 4939 (2022).

Yang, Y., Miao, Z., Zhang, H., Wang, B. & Wu, L. Lightweight Attention-Guided YOLO with level set layer for landslide detection from optical satellite images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ Remote Sens. 17, 3543–3559 (2024).

Ding, Z., Ning, J., Zhou, Y., Kong, A. & Duo, B. Detecting landslides with deformable adaptive focal YOLO: enhanced performance with reduced false detection. PFG-J Photogramm Remote Sens. Geoinf. Sci. 92, 115–130 (2024).

Chandra, N. & Vaidya, H. Automated detection of landslide events from multi-source remote sensing imagery: performance evaluation and analysis of YOLO algorithms. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 133, 127 (2024).

Jin, Y. et al. Landslide detection based on efficient residual channel attention mechanism network and faster R-CNN. Comput. Sci. Inf. Syst. 20 (3), 893–910 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Landslide deformation prediction based on a GNSS time series analysis and recurrent neural network model. Remote Sens. 13, 1055 (2021).

Wang, C., Fang, L. & Hu, C. Applying deep learning model to aerial image for landslide anomaly detection through optimizing process. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk. 16 (1), 2453072 (2025).

Liu, X., Xu, L. & Zhang, J. Landslide detection with mask R-CNN using complex background enhancement based on multi-scale samples. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk. 15 (1), 2300823 (2024).

Li, Y. The research on landslide detection in remote sensing images based on improved DeepLabv3 + method. Sci. Rep. 15, 7957 (2025).

Lin, H. et al. A method for landslide identification and detection in high-precision aerial imagery: progressive CBAM-U-net model. Earth Sci. Inf. 17, 5487–5498 (2024).

Ghorbanzadeh, O. et al. Landslide detection using deep learning and object-based image analysis. Landslides 19, 929–939 (2022).

Ghorbanzadeh, O. et al. Contrastive Self-Supervised learning for globally distributed landslide detection. IEEE Access. 12, 118453–118466 (2024).

Kariminejad, N. et al. Evaluation of various deep learning algorithms for landslide and sinkhole detection from UAV imagery in a Semi-arid environment. Earth Syst. Environ. 8, 1387–1398 (2024).

Shahabi, H. et al. Unsupervised deep learning for landslide detection from multispectral Sentinel-2 imagery. Remote Sens. 13 (22), 4698 (2021).

Piralilou, S. T. et al. Landslide detection using Multi-Scale image segmentation and different machine learning models in the higher Himalayas. Remote Sens. 11 (21), 2575 (2021).

Kumar, K., Misra, R., Singh, T. N. & Singh, V. Landslide detection with Ensemble-of-Deep learning classifiers trained with optimal features. Adv. Data Sci. Artif. Intell. 403, 313–322 (2023).

Zhang, R., Lv, J., Yang, Y., Wang, T. & Liu, G. Analysis of the impact of terrain factors and data fusion methods on uncertainty in intelligent landslide detection. Landslides 21, 1849–1864 (2024).

Saha, S., Ahmad, T. & Yadav, A. Chapter 15 - Miscellaneous applications of deep learning based multi-sensor Earth observation. Deep Learning for Multi-Sensor Earth Observation (ed. Saha, S.). 381–407 (2025).

Li, Z. et al. Study on Temporal and Spatial distribution of landslides in the upper reaches of the yellow river. Appl. Sci. 14, 5488 (2024).

Tu, K., Ye, S., Zou, J., Hua, C. & Guo, J. InSAR displacement with High-Resolution optical remote sensing for the early detection and deformation analysis of active landslides in the upper yellow river. Water 15, 769 (2023).

Du, J. et al. InSAR-Based active landslide detection and characterization along the upper reaches of the yellow river. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ Remote Sens. 16, 3819–3830 (2023).

Tian, H. et al. Analysis of landslide deformation in Eastern Qinghai Province, Northwest China, using SBAS-InSAR. Nat. Hazards. 120, 5763–5784 (2024).

Chen, X. et al. Landslide recognition based on DeepLabv3 + Framework fusing ResNet101 and ECA attention mechanism. Appl. Sci. 15, 2613 (2025).

Liu, H., Chen, Y., Wang, R., Li, M. & Li, Z. MFA-Deeplabv3+: an improved lightweight semantic segmentation algorithm based on Deeplabv3+. COMPLEX. INTELL. SYST. 11, 424 (2025).

Peng, H., Xiang, S., Chen, M., Li, H. & Su, Q. DCN-Deeplabv3+: A novel road segmentation algorithm based on improved Deeplabv3+. IEEE Access. 12, 87397–87406 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. GCF-DeepLabv3+: an improved segmentation network for maize straw plot classification. Agronomy 15, 1011 (2025).

Chen, H., Qin, Y., Liu, X., Wang, H. & Zhao, J. An improved DeepLabv3 + lightweight network for remote-sensing image semantic segmentation. Complex. Intell. Syst. 10, 2839–2849 (2024).

Zhu, F., Li, D., Li, H., Liu, Y. & Zhu, B. Person re-identification based on an improved DeepLabv3 + semantic segmentation network. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 157, 111384 (2025).

Wang, Y. et al. Improved DeepLabV3 + for UAV-Based highway lane line segmentation. Sustainability 17, 7317 (2025).

Lai, P. et al. Improved lightweight DeepLabV3 + for bare rock extraction from high-resolution UAV imagery. Ecol. Inf. 89, 103204 (2025).

Hou, X., Chen, P. & Gu, H. LM-DeeplabV3+: a lightweight image segmentation algorithm based on Multi-Scale feature interaction. Appl. Sci. 14, 1558 (2024).

Shi, L., Lian, X., Duan, X. & Liu, X. FV-DLV3+: a light-weight flooded vegetation extraction method with attention-based DeepLabv3+. Int. J. Remote Sens. 46 (1), 366–391 (2024).

Li, R., Zhao, J. & Fan, Y. Research on CTSA-DeepLabV3 + Urban green space classification model based on GF-2 images. Sensors 25, 3862 (2025).

Ma, R. et al. Identification of maize seed varieties using MobileNetV2 with improved attention mechanism CBAM. Agriculture 13 (1), 11 (2023).

Zhu, Y., Yuan, K., Zhong, W. & Xu, L. Spatial-Spectral ConvNeXt for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ Remote Sens. 16, 5453–5463 (2023).

Zhu, H., Cao, G., Zhao, M., Tian, H. & Lin, W. Effective image tampering localization with multi-scale ConvNeXt feature fusion. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 98, 103981 (2024).

Li, C. et al. Valuable clues for DCNN-Based landslide detection from a comparative assessment in the Wenchuan earthquake area. Sensors 21, 5191 (2021).

Tang, M., He, Y., Aslam, M., Akpokodje, E. & Jilani, S. F. Enhanced U-Net + + for improved semantic segmentation in landslide detection. Sensors 25, 2670 (2025).

Lei, T. et al. Unsupervised change detection using fast fuzzy clustering for landslide mapping from very High-Resolution images. Remote Sens. 10, 1381 (2018).

Chen, X. et al. Conv-trans dual network for landslide detection of multi-channel optical remote sensing images. Front. Earth Sci. 11, 1182145 (2023).

Jiang, W. et al. Deep learning for landslide detection and segmentation in High-Resolution optical images along the Sichuan-Tibet transportation corridor. Remote Sens. 14, 5490 (2022).

Ji, S., Yu, D., Shen, C., Li, W. & Xu, Q. Landslide detection from an open satellite imagery and digital elevation model dataset using attention boosted convolutional neural networks. Landslides 17, 1337–1352 (2022).

Li, D., Tang, X., Tu, Z., Fang, C. & Ju, Y. Automatic detection of forested landslides: A case study in Jiuzhaigou County, China. Remote Sens. 15 (15), 3850 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Gaofen-6 satellite imagery provided by the Qinghai Provincial Remote Sensing Center of Natural Resources.

Funding

This research was funded by This work was funded by Qinghai Institute of Technology “Kunlun Talent” Talent Introduction Research Project (2023-QLGKLYCZX-25).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, W.T. and J.Z.; methodology, J.Z.; software, J.Z.; validation, W.T. and J.Z.; formal analysis, W.T. and J.Z.; investigation, F.W. and W.W.; resources, X.W.; data curation, X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Z.; writing—review and editing, W.T. and J.Z.; project administration, W.T.; funding acquisition, W.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tuo, W., Zeng, J., Wu, F. et al. Landslide detection using multimodal data fusion and an improved Deeplabv3+ model. Sci Rep 16, 1383 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31208-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31208-6