Abstract

The recognition of mathematical expressions remains a challenging task, particularly due to the segmentation sub-stage, which plays a critical role in the overall recognition process. Despite significant advancements in mathematical expression recognition, existing research has primarily focused on the recognition phase, often overlooking the segmentation issues that arise in diverse domains such as computer vision and image processing. This study aims to address the segmentation problem in handwritten mathematical text and expression recognition through a comprehensive analysis and the development of an optimal solution. Classical segmentation methods were explored, classified, and tested on various datasets of mathematical expressions, with multiple comparative case analyses conducted. Based on these findings, an optimal neural network-based segmentation approach was proposed. The model demonstrated effective segmentation performance, achieving competitive mean Intersection over Union (IOU) scores of 79.4%, 83.5%, 81.3%, 74.6%, and 79.6% on the CROHME 2014, CROHME 2016, CROHME 2019, Aidapearson, and HasyV datasets, respectively. The results highlight the success of the proposed neural network-based solution in overcoming the limitations of traditional segmentation methods and affirm its potential in enhancing mathematical expression recognition systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Segmentation determines the many performance matrices, such as accuracy, error rate, loss, etc., in every complex and higher-level work in computer vision and image processing. The segmentation divides the image’s background or non-ROI portion from the foreground or Region of Interest (ROI)1. Segmentation is the factor that, at the initial stages, filters out the unnecessary information in the input image to perform tasks like object detection, object localization, and object recognition. So, the post-segmentation algorithms for the various tasks can produce the best results2. Segmentation is widely utilized in industries like security, self-driving automobiles, and medical imaging. SOTA models execute segmentation tasks at a highly granular and nuanced level in applications like medical imaging. Medical segmentation models operate on pictures that need to pay close attention to even the smallest details in the input image3. Attention to detail is also necessary for handwritten or digitally printed papers since textual material consists of several delicate and minute entities. Traditional techniques are available for segmenting the images in such a dataset4. Still, traditional techniques suffer from the problem of changing the attributes of the images. On the other hand, just a few neural network systems can handle the different qualities but are also vulnerable to other causes like noise. The suggested study addresses these problems, which are present in standard and deep learning-based methodologies, and suggests a novel model to carry out picture segmentation more accurately5.

With the evolving domain of deep learning in the past two decades, the fields dealing with images have seen major shifts in tasks such as segmentation, recognition, localization, generation, etc.6. From face recognition to self-driving cars and medical imaging, every field has seen tremendous interest from researchers and enthusiasts7. Among all other domains being juridically/fairly attended and researched, the field of handwriting recognition, especially handwritten mathematical expression recognition, has been devoid of interest and effort compared to other trending domains. Domains like medical imaging, autonomous driving vehicles, and GAN have been flooded with dedicated architectures and neural network models to perform the intended segmentation tasks8. The utility models and techniques in these domains are the integration of state-of-the-art technologies and algorithms. Dedicated models like inception, xception, mobilenet, VGG16, VGG19, etc., are already available for object detection tasks. The wide availability of such models proves the work that has been massively proposed and presented in these fields9.

In contrast to these trending fields, the domain of segmentation and recognition problems in the handwritten mathematical text seems less concentrated in segmentation issues10. The available methods and tools are insufficient to harness the field’s potential. In the past decade, progress in the segmentation and recognition of the HME has not been seen as meteoric as in other domains10. Thus, there is a need and call of the hour to specifically target and address the segmentation issues in handwritten mathematical expressions by considering the fortified and well-founded capabilities of emerging segmentation models and methodologies.

This article aims to objectively bring up challenges in the segmentation problem of HME and experiment with all varied segmentation methodologies. Though the machine learning and deep learning models are flourishing and prevailing in the current segmentation trends, the authors have decided to take up the whole experimental and observational voyage on their own, uninfluenced by just apparent trends of the time that are having persuasion in various other domains11,12. This experimental study on the segmentation of HME will be the first conjectural and substantially palpable article giving deep insights into segmentation problems while deploying all major conventional to emerging technologies and methods. This study also aims to highlight the role and importance of each segmentation methodology category. The whole article has a novelistic perspective, with the coherence of concepts and ideas providing a smart roadmap for reading and understanding. The roadmap of the article is presented in Fig. 1.

Preeminence of the study with state-of-the-art

The authors have reviewed multiple articles and studies on this domain for intense research on the existing state-of-the-art methodologies and subdomains of handwriting recognition and handwritten mathematical expression recognition. The recognition problem has been targeted and resolved using a transformer-based decoder trained in both directions. The improvements achieved by the approach lie in the range of 2–2.5% compared to the state-of-the-art model13. One of the recent works by Bian paid close attention to the recognition and translation of mathematical expressions, where they deployed a bi-directional network with an attention mechanism14. The decoder uses a CNN decoder instead of an RNN decoder to address the vanishing gradient issue15. The authors explored various traditional techniques for recognizing Arabic handwriting, and the challenges associated with such techniques are discussed in detail16. The research uses various line segmentation techniques in handwritten character techniques, and a specific set of segmentation techniques has been reviewed. The line segmentation techniques are prominently employed in character segmentation17. The study of handwritten character recognition in Gujarati characters by CNN, done by Patel, mentions the trending CNN classifier consisting of various layers, and the accuracy achieved by the neural Network is 90%18. The paper proposes a model to recognize the handwritten character individually.

Thus, by studying and reviewing many papers and articles on the recognition and segmentation of handwritten mathematical expressions, the authors have found that in the entire process of recognition of HME, the segmentation phase is crucial, and the following observations have been concluded.

-

Despite its significance, segmentation has lacked focus in most of the research. Though exploring the recognition phase field has benefits, it certainly cannot diminish the significance of the preceding phases involved in the recognition process. Having in-depth insight into the recognition phase substantiates and advances the progress of recognizing HME. Still, exploring the segmentation part of the process in-depth would also expose many aspects of the phase, which can then be explored and molded in a form to be utilized in the recognition process as an accelerating contribution component.

-

The intense and comprehensive research about the previous studies and research done by the authors validate that the recognition step in the entire process has been the center of prime attention. A very detailed and rich spectrum of varied research with different perspectives has been done on the single domain of recognition only. However, the segmentation phase does not feature such a wide and varied range of exploration and research. The articles and researchers discuss current and past techniques’ features, coverage, and shortcomings in the recognition phase. Still, the segmentation phase, on the other hand, remains untouched by such endeavors in comparison to its counterparts.

The authors of this presented article, having studied various available articles and research works about segmentation, have noticed the deficits of the domain. All the shortcomings mentioned and unmentioned in the previously done studies are categorized and discussed in detail as follows:

-

1.

Robustness The studies discuss methods like thresholding techniques that produce optimal and great results under specific conditions. If there is a subtle change in a parameter from the set, the proposed Technique and model will fail.

-

2.

Coverage The second persisting problem in the techniques is the convergence of the model. Discussed models and techniques would work on one type of image but may fail on another dataset type. A prime example of this can be attributed to global and local binarization, which requires the grayscaling and channel reduction of the candidate image before performing the segmentation task.

-

3.

Speed The time the segmentation process takes is the key factor determining whether the entire recognition process will fail or pass. Some techniques like Otsu Binriation and Adaptive mean thresholding are moderately fast. Still, for some image candidates, algorithms like KMeans and watersheds take too long to generate the single-segmented image.

-

4.

Parameter dependency The majority of the techniques, static ones discussed in various studies, solely work on the parameters they are inputted with manually. This dependency is a shortcoming because the constant parameter is not ideal or optimized for various samples. The setup of a method with a certain set of parameters can perform segmentation with the best accuracy. Still, static parameters are not ideal for a generalized dataset containing various types of images with varying intrinsic properties.

-

5.

Dimensionality Problem Static methods like KMeans, Watershed segmentation, Otsu Binarization, and many more work on the various sizes of images. But, unexpectedly, more advanced models based on neural Networks do not work on various image sizes. The workaround for this issue may be attributed to the resizing. Still, the problem posed by resizing is that it distorts the image sample(s) if the resizing is done without keeping the aspect ratio in care. Though considering maintenance of the aspect ratio saves the image quality, again, the image produced post-resizing operation, with aspect ratio maintaining, produces an image of variable size across one dimension.

-

6.

Performance Metrics To get an insight into the accuracy or quality of the segmentation by the static method, there are not many criteria by which the performance of the algorithms can be evaluated.

The flaws and shortages diagnosed by the authors motivated them to develop a novelistic study with the following strengths and preeminence.

-

To develop a more robust and hybrid Technique to segment various handwritten mathematical expressions.

-

The approach in this presented study qualifies as a better approach than the other existing one. Expanding the coverage in the first stage considers using the dataset from varied sources to maintain the generalization.

-

Having the dataset from various sources provides samples of different qualities. The type of information also changes according to various factors like the mode of candidate dataset generation, demographics, range of the samples, and so on. A criterion judges the candidate dataset’s quality, compatibility, and need; hence, the authors’ agreement is required to include a dataset; consistency is ensured in the initial phases.

-

The second crucial step taken by the authors is selecting the state-of-the-art segmentation techniques to generate the best and most strongly segmented candidate for the final dataset. The comparison of various SOTA segmentation techniques in the HME domain is performed before finalizing the dataset on which the model will be trained.

-

The manual comparison by the manual visual interpretation technique ensures that the infused candidate mask with the corresponding input image remains the best-segmented image.

-

The preparation of the dataset for training encoder-decoder-based architecture, introduced in the paper, would ensure that the post-training segmentation done by this architecture model would be the best possible and optimized one.

Motivation of the research

-

Introduction of More Robust Segmentation Technology Techniques for segmenting handwritten mathematical texts and other comparable documents already exist. However, they frequently fail when the inherent image qualities are slightly altered. For instance, a straightforward three-step process may result in very different results for two photos with identical features other than brightness that has been adjusted slightly. Undoubtedly, we need an approach that is more resilient and unaffected by minute changes in the image’s attributes.

-

To curtail the dependency of the task on humans To handle the variety of input photographs and deliver the optimum target segmentation, several manual segmentation approaches and algorithms require the input of appropriate parameters. These techniques and procedures are effective when the dataset size is reasonable, and a human may actively or passively select the best value for segmentation. Physical intervention, however, becomes impossible as the dataset expands.

-

Extending the scope of existing technologies To detect anomalies and cancers in scanned pictures of limbs like the heart, liver, and kidney, the medical field uses such tailored models. The currently available technologies can be shaped to be used in textual texts, including handwritten and digitally printed ones. These models can be useful in textual data, such as scanned texts and pages since they operate with minute details and can distinguish between nuanced and minute levels.

Objective of the research

The motivation highlights the interest of the authors in the domain and the major concern associated with segmentation problems. Thus, the objective of the research has been finalized as follows:

-

To experimentally analyze and compare prominent segmentation techniques that belong to different segmentation classes.

-

To find the best suitable method for the segmentation of handwritten mathematical expressions.

-

To propose the optimal solution for the segmentation problem in mathematical expression recognition.

At the end of the current research study, the research outcomes will be an optimized solution for dealing with segmentation challenges. The study aims to highlight the case analysis of varied segmentation models and find the competitive performance of the proposed solution by testing on different datasets.

Background

Before a deeper dive into the experimental aspects of the domain, there is the need to analyze and comprehend the reasonable core points that need to be attended to and looked upon. The authors have endeavored to cover those basics briefly for readers’ clarity. These conceptual aspects are raised to justify the purpose of the experimentation carried out in this study.

What is segmentation, and why is it crucial for mathematical text?

Segmentation of an image is a way of breaking down a digital visual into various subsets or subdivisions known as Image segments, which aids in decreasing the complexity of the image and making subsequent processing or analysis smoother and easier19. In layman’s terms, segmentation is assigning labels to pixels. A common label is assigned to all picture parts or pixels in the same category. Take, for example, a case in which an image must be provided as input for object detection. Instead of processing the entire image, the detector can be fed a section chosen by segmentation. This keeps the detector from processing the entire image, lowering inference time.

The study focuses on performing segmentation on the image dataset, which has mathematical text, statements, and expressions as mathematical expression (ME) recognition has been a vibrant subject of research in recent years owing to the pacing rise of human interface devices and the increased interest in translating the scientific contents into electronic documents19. Three concerns must be addressed for any mathematical expressions to be recognized: segmenting the images, recognizing symbols, and assessing structural links. The entire recognition scenario provides a strong motivation for robust segmentation of the mathematical expression and its associated contents, as these characters are densely connected with typically complex signs and symbols. The depicted challenges call for accurately segmenting individual and constituent symbols hidden in mathematical expressions before accomplishing the recognition part. Thus, highlighting the role of effective segmentation in the successful recognition tasks.

Classification of segmentation techniques

A list of techniques can be extracted and stacked when deeper into the literature based on segmentation methods. Aside from generic terminologies like instance and semantic segmentation, it has been observed that many segmentation approaches work effectively with neural Network structures, thresholding-based techniques, clustering, and other region/edge methodologies20. Consequently, the various segmentation techniques may be classified under these significant classification headers, and a hierarchy chart of the compiled segmentation approaches has also been displayed. Because instance and semantic segmentation follow a general approach, they are arranged separately in the classification diagram10,21. All other individual segmentation approaches are inserted and categorized under the specified headers with broader coverage. Figure 2 represents the classification of segmentation techniques.

Instance segmentation

Instance segmentation aims to generate a representation of a class of objects separated into individual instances. To set digital technology to perform a process or processes to accomplish a workflow or function, the quantity of instances is unknown, and the assessment of the produced instances is not based on pixels22,

To define it in simpler words, image segmentation is a method in which a digital image is broken down into various subgroups called image segments, which helps reduce the complexity of the image and makes further processing or analysis of the image simpler23. The count of the extent of instances in an image, object detection of all objects in an image, categorization of individual objects, and object localization using bounding boxes are all integrants that build up instance segmentation.

Semantic segmentation

The major Intent of semantic image segmentation is to attribute a class to each pixel in an image. The key hurdle in this regard is dense prediction, which involves projecting and forecasting for each pixel in the image. The end purpose lies in determining the class labels for each pixel in the image. A point to ponder is that, unlike instance segmentation, semantic segmentation does not deal with separate instances of the same class. The prominence is in the category of each pixel24.

Thresholding-based segmentation

Thresholding is the Technique of revamping the pixels in an image to make it easier to examine. A binary image is only black and white, and the procedure of creating one is known as thresholding. This sort has three bifurcations: local, global, and multilevel thresholding25.

Clustering-based segmentation

It is a methodology for pixel-by-pixel image segmentation. This segmentation approach strives to group pixels that are close together. We just talked through two mechanisms of segmentation based on clustering26. Using clustering techniques, data points from variable groups that are more comparable to each other are gathered together. Using the flexible C-means (FCM) Technique, a single piece of data can feasibly belong to two or more clusters27. Fuzzy set theory sets off a rise of multivalued fuzzy logic. This fuzzy refers to clustering commonly used to produce soft segmentations, such as brain tissue models28.

Edge-based segmentation

This subcategory of the process of image seg methods is related to regions. A region is a collection of connected pixels with similar qualities, such as intensity, color, etc. In this type of segmentation, each pixel must follow a specific set of defined rules and constraints to be categorized into comparable pixel regions29. For instance, region segmentation approaches have edge-over-edge segmentation methods in a noisy image. Based on the approaches used, region-based strategies are further split into two subcategories: region growth and region splitting.

Neural network-based segmentation

Artificial intelligence and Machine learning segmentation methods are being applied, especially using the neural network approach. These methods are categorized as neural network-based headers. Several supervised and research communities have substantially explored unsupervised machine learning algorithms for segmentation-related tasks. Image recognition and processing features often used in our smartphones use a convolutional neural network (CNN), a type of artificial neural Network, to process the input pixels of a segmented image30. To summarize neural network-based segmentation, we can say that CNNs are vital in these two segmentation types.

Challenges in segmentation

Suitability of technique for essential tasks

The choice of the segmentation method and its extent presents the biggest hurdle in this category. No one method works well for all tasks. Every segmentation method and Technique, including SOTA, has a different approach and range of applications. No one segmentation method can be applied to all the tasks. Therefore, choosing the best approach for the job is seen as a significant challenge31.

Preparing dataset for segmentation

When there are many samples in the dataset, preparing the data for segmentation is also considered a difficult part of the segmentation process. The attributes of the image(s) must be regularly distributed, and the minimum number of outliers is required. The outliers not only require extra work, but they also lower the data’s quality. Thus, one of the challenges in the process is getting the dataset ready for the segmentation task32.

Right format or representation

Many data sources are available online, but it can be challenging to identify the right dataset for a segmentation or augmentation task. Finding the data in a format that is appropriate for usage takes a lot of work, and if the data is large or not in the format that is wanted, the work must be repeated numerous times33.

Deciding optimal technique from varied segmentation methods

Selecting a single segmentation technique from a large class of segmentation techniques presents another challenge. For instance, numerous segmentation approaches include fuzzy, k means, divisive, and merging available in clustering methods34. Choosing the appropriate segmentation from the range of options available for a given goal can be difficult.

Extensive efforts called for ground truth preparation in neural networks-based segmentation

Since the model would utilize this ground truth to modify its weight for the best accuracy, neural network-based techniques must generate the ground truth data or y label with the utmost care. The difficulty here comes from the wide range of values for the images’ attributes, such as contrast, brightness, noise, sharpness, resolution, etc.35. The dataset comprising the images with different resolutions must be handled by padding or scaling because the model only accepts images with a fixed resolution.

Research methodology

The research flow analysis for the conduction of the entire experimentation has been systematically and formalized before the onset of the experimentation which is shown in Fig. 3. A series of steps were used to formulate the entire research procedure. The research methodology has seven key steps described in detail in the succeeding sections of the article. The foremost step in beginning the experimentation revolves around the corpus or the dataset that is supposed to be subjected to segmentation experimentation. The first step of the research methodology is associated with corpus collection. The next and second important step in the process is the arrangement of the selected corpus and its preparation for the phase in succession. The third significant phase is experimenting with the segmentation strategies to be deployed. After the completion of the experiment and observation of the results of the case studies undertaken for experimentation, the workflow was directed to preparing ground truth for the neural Network-based model. Thus, the fourth step gravitates around ground truth model preparation, funneling down to model construction and development for the corpus. The sixth and seventh steps follow this stage, including the proportion of training and testing tasks. The seventh step also covers the analysis part after effective segmentation.

Experimentation

Every involved phase in the experimentation section is discussed in the following subsections in depth and their entirety:

Corpus collection

The segmentation model is projected to perform with acceptable accuracy on various samples. The authors decided to populate the dataset from various sources to maintain the generalization. The source variation also substantiates the variation in the individual image samples. Datasets from the various sources have various features associated with them. The dataset selection is a crucial step because it acts as a deterministic phase that can drastically alter the entire process of segmentation tasks and adversely impact the intermediate phases. The strong candidates for the final datasets are CROHME1436, CHROHME1636, CROHME1936, the custom dataset from AIDAPEARSON37 and HASYv238. All these datasets contain the tokens, i.e., individual symbols and expressions from various domains of mathematics like AP, GP, Integrals, Derivatives, Imaginary notations, trigonometry, etc.

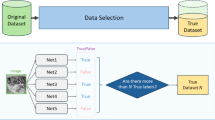

Dataset selection

Authors have employed the inter-rater-reliability criteria to select the most suitable dataset(s). The criteria act as the function determining whether a dataset qualifies to be counted as the final dataset. This criterion works on the agreement of the parties termed as raters or judges. In the experimentation presented, each author was asked to give a rating on a scale of 5 for a specific feature in the dataset for each dataset. The ratings collected from the authors are then populated, and the overlapping ratings are counted as 1; otherwise, they are 0. This process is done for each feature category and each dataset. The final score is then added, and percentage agreement is calculated. If the percentage agreement for each dataset is more than 50%, it is included in the final dataset and discarded otherwise which is shown in Table 1.

Table 1 represents that each row is one quality criterion: Sample Quality, Suitability, Sample Size, Expression Coverage, Variation. For each criterion the three authors gave scores for each dataset (scores run 1–5). These are the author score columns. For each criterion and dataset authors then recorded pairwise agreement between authors: A1 vs A2, A2 vs A3, A1 vs A3. If a pair gave the same score, that pair gets a 1. If they differed, it gets a 0.

The three pairwise agreement values for a single criterion add up to a small integer between 0 and 3. Those are the intersection columns. The TOTAL for a dataset is the sum of intersection points across all five criteria. The maximum possible total is 15 because 5 criteria × up to 3 agreement points per criterion = 15.

Look at the three author scores for that dataset under that criterion.

-

Compare A1 and A2. If equal, record 1; if not, record 0.

-

Compare A2 and A3. If equal, record 1; if not, record 0.

-

Compare A1 and A3. If equal, record 1; if not, record 0.

The three 1/0 values are the pairwise intersection entries. Their sum (0 to 3) is that criterion’s contribution to the dataset’s TOTAL.

-

Formula : Total intersection points for a dataset ÷ 15 × 100 = Percentage agreement.

E.g

-

D1 (CHROHME14–19) total intersection points = 13 → Percentage = (13 ÷ 15) × 100 = 86.7%.

-

D2 (HASYv2) total = 13 → 86.7%.

-

D3 (AidaPearson) total = 11 → 73.3%.

Threshold has been set to 70%. Any dataset with percentage agreement above 70% is selected. By this rule D1 and D2 (86.7%) and D3 (73.3%) are all retained. Pairwise intersection emphasizes exact agreement between authors. It is a conservative measure: only identical scores count as agreement. This reduces chance agreement that could occur from similar but not identical scores. Threshold 70% is reasonable. It requires clear agreement from authors across most criteria while allowing small differences. D1 and D2 are strongly agreed upon. Their 86.7% shows consistent judgments across all five criteria. D3 meets the cut-off but with less agreement. At 73.3% there is more disagreement among authors on some criteria. Consider noting which criteria had lower pairwise agreement if you want to justify keeping D3.

Merging CHROHME14/16/19 into D1 is justified when those datasets are successive extensions. Treating them as one avoids artificial fragmentation and reflects their conceptual continuity. The authors have finalized five datasets, namely CHROHME14, CHROHME16, CHROHME19, HASYv2, and from AidaPearson. Upon deep and comprehensive inspection, the authors found that all the versions of CHROHME, in series, are extensions of the previous ones. Considering this fact, the authors merged all three versions of CHROHME into a single dataset that variable D1 represents. The second dataset, named D2, is the representation of the HASYv2. In the same manner, D3 is a representation of AidaPerson’s dataset.

The first column shows the criteria on which the authors perform the dataset agreement. The following three columns, having attributes as the author numbers, show the agreement points rewarded by the author for each dataset under a defined criterion. The criteria are the parameters based on which the dataset quality can be evaluated. After that, the three columns have the attributes as the representation of the intersection of scores provided by the three authors for a specific dataset correspondingly. If both the authors have the same score for a dataset, then their intersection would have a score of 1; otherwise, 0. Similarly, the intersection between each author’s points would be done under each dataset’s criteria. Then, for each criterion and each dataset, the intersection points would be added from each intersection column and put in the total columns under the sub-column named with each dataset in order. In the next step, each dataset’s points would be added, and the percentage would be calculated with the maximum possible score, i.e., 15. This percentage is attributed as Percentage Agreement. If the percentage agreement of a dataset is more than 70%, it is considered the dataset; otherwise, it is discarded.

By this method, the dataset D1(CHROHME14-19) and D2(HASYv2) have a percentage agreement of 86.6 each, and D3Aidapearson’s) has a score of 73.3%.

Dataset details

The CROHME2014 dataset contains 10,000 (approx.) images of handwritten mathematical expressions. This dataset is used so that 8750 images are used for training the neural network, and the remaining would be used for post-training testing.

CROHME 2016: Combining the data sets from four previous CROHME competitions and adding new resources, the dataset offers more than 12,000 handwritten expressions by hundreds of authors from various nations. From a corpus of phrases, writers were instructed to reproduce printed expressions. The corpus was selected from an existing math corpus, and terms were embedded in Wikipedia pages to cover the diversity suggested by the various challenges. Different scales and resolutions have been employed because different devices have been used (different digital pen technologies, white-board input devices, tablets with reasonable screens). Only the online signal is provided by the dataset. The CROHME 2016 test dataset uses 1147 new online handwritten expressions, whereas the training and validation sets employ data from the CROHME 2014 datasets. Additionally, this new bundle offers new math resources and updated versions of the following tools: Wikipedia contains more than 500 K LaTeX expressions that can be used to train language models.

CROHME 2019: The CROHME 2019 dataset is another addition to the CROHME dataset series series. It contains the expressions from CROHME 2014 and CROHME 2019, and in addition to these two, another 1199 expressions.

Another dataset from aidapearson contains more than 100 k raw images of handwritten mathematical expressions divided into ten directories. 10,000 images were selected from one directory for training and another 2000 for testing the model after the training.

The fifth dataset is the HASYv2 dataset, which contains handwritten mathematical symbols. The HASYv2 dataset contains 168,250 images from which various symbols and alphabets. A suitable number of images are selected from HASYv2 for training and testing.

Even though the experiments use benchmark datasets like CROHME and HASYv2, these are rather clean and standardized datasets. How the model will perform with other and more diverse and noisy real-world handwritten mathematical data, e.g. scan artifacts, blurred characters or different handwriting styles, has not been investigated. The proposed approach could be tested on such datasets, which would be more valuable to prove the generalization and practical applicability.

Implementation details

The experimentation is performed on the Google Colab environment with 16 GB of graphical memory, 320 Turing Tensor Cores, and 2560 CUDA Cores. The free environment has a memory of 13.6 GB, and the space storage space available can vary according to the drive space for different users. However, during experimentation, the free space varied from 45 to 25 GB. The Google Colab was run on Google Chrome Version 103.0.5060.53 (Official Build) (64-bit), and the GoogleChrome’s host OS is Ubuntu 22.04 LTS running on Intel® Core™ i5-8250U CPU @ 1.60 GHz octa-core processor and memory of 12.0 GB.

Segmentation technique selection

The core idea of this study is that no single segmentation method exists that can perform well in every case. Some techniques may perform well in a specific condition and may perform the worst in others. To prepare the dataset for the neural network model to train, various state-of-the-art segmentation techniques are employed on each image, and their corresponding results are then saved. The best results saved by the manual image segmentation are saved as the ground truth. The comparison and illustrations of each Technique are depicted in the following sections.

Case analysis

The authors have picked and deployed prominent segmentation techniques from existing segmentation classes to select the optimal segmentation technique. The authors have conducted rounds of brainstorming sessions from the major categories specified in the section to finalize five techniques of varied segmentation categories. The selected segmentation techniques for experimentation are global thresholding, adaptive thresholding, otsu binarization (belonging to threshold-based segmentation), k-means clustering (belonging to clustering-based segmentation), canny edge detection (belonging to the class of edge-based segmentation), and watershed segmentation (belonging to the class of region-based segmentation). Different segmentation classes have been extensively experimented with several techniques to reach the optimal segmentation method. Thus, every case has been experimented to discover the optimal solution.

Case -1 global thresholding

Global thresholding is the method of binarization or segmentation in which a user passes a threshold value as a parameter in the global thresholding function. The target image pixels are generated so that if the input pixel is more than or equal to the threshold, the corresponding target pixel would be set to the supplied high value. If the pixel intensity of the input pixel is less than the threshold, then it is set at 039. The global thresholding in this experiment is implemented using the OpenCVlibrary’s thresholding() function. The thresholding function has the following definition:

cv.threshold(src,thresh,max_val,thesholding_mode)

Where

src = grayscale image.

thresh = threshold value for segmentation.

max_val = maximum value of the pixel to be set in the target.

threshloding_mode = mode selection, which would impact the intermediate calculations in the segmentation process.

The mathematical interpretation of the global thresholding is given in (1):

Figure 4a and b show the post-application of global thresholding results. It is clear and visually interpretable that this method produces great results for a few image samples; for others, it just vanishes the entire image or turns it into an accumulation of useless black pixels. Figure 4a depicts the successful segmentation of the image sample using the global thresholding method. On the other hand, Fig. 4b shows the samples where the global thresholding method suffers and fails.

Case-2 adaptive thresholding

In the case of adaptive thresholding, unlike global thresholding, the thresholding value is calculated for smaller regions. The key difference between adaptive and global thresholding is the steps in which the threshold value is chosen in each method. In global thresholding, a global threshold value is selected manually. That selected value is applied to the entire input image to generate the target, the binary image39. However, in the case of adaptive thresholding, the threshold value is generated for the smaller regions of the images based on the following mathematical formula:

where.

DST(x,y) = pixel value of the target

maxValue = maximum value that can be assigned to a pixel

src(x,y) = pixel at position (x,y) in the source or input image

T(x,y) = threshold calculating algorithm

In the implementation phase, authors used the cv.adaptiveThreshold() method to apply this Technique. The method takes parameters as follows:

cv.adaptive threshold(src, maxValue, adaptive method, threshold type, blockSize, C).

where

src = grayscale input image.

maxValue = Maximum value that can be assigned to pixel in the target image.

adaptive method = Adaptive thresholding algorithm to be used from the pool.

threshold type = binary or inverted binary.

blockSize = size of the pixel neighborhood that is used to calculate the threshold value.

C = Constant that can be subtracted from the mean, which is the intermediate result of the process. It is optional.

The adaptive thresholding technique advances the global thresholding technique, which generates the optimized pixel value for each pixel in the target image. Though it is better than the global thresholding technique in various aspects (see Fig. 5a), it is also prone to shortcomings like varying lighting conditions. A little bit of shade of darker colors can ruin the entire image. The same is the case with the noise in the image. If the input image contains noise at a certain level, the output produced by this method would also contain noise as the patches of black pixels (see Fig. 5b).

Case-3 Otsu binarization

Otsu binarization is another extension of the global and adaptive thresholding implementation, but it differs from the former two on the grounds of the Threshold value calculation. The global thresholding and adaptive methods take arbitrary thresholding values that can be calculated based on the neighboring pixels. In the case of the Otsu method, the manual selection of the thresholding values is not required. The underlying algorithm in this method would automatically select the best and optimum thresholding value. The loose description of the Otsu Binarization can be explained as iterating through all the possible threshold values and calculating the spread for the pixel levels on each side of the threshold, i.e., the pixel that either falls in the foreground or background. The aim is to find the threshold value where the sum of foreground and background spreads is at its minimum40.

The algorithm generates Weights, Means, Variance, and class variance for each Threholding value and tries to minimize the within-class variance and the corresponding thresholding value for which the within-class variance is the minimum; that thresholding value is selected to generate the target output. The algorithm can be explained in the following steps:

During this implementation of authors have utilized python implementation of the Otsu binarization as :

cv.threshold(src,min_val,max_val,cv.THRESH_BINARY + cv.THRESH_OTSU).

Where,

src = input image

min_val = First thresholding value to start the algorithm with

max_val = Last thresholding value to use the algorithm with

cv.THRESH_BINARY+cv.THRESH_OTSU = flag to tell the thresholding method to use Otsu binarization and normal thresholding.

By analysis, the researchers have found out that though Otsu’s method is comparatively better in producing results and its applicability and robustness than the previously discussed two methods (see Fig. 6a), this method also suffers from the noise and variance in the lighting condition and a little bit of change in the lighting shade can produce bad results (see Fig. 6b).

Case-4 K- means clustering

K-means clustering is another prominent image segmentation technique the authors employ to generate candidate ground truth for the corresponding input image. It falls under the clustering-based segmentation method and is an unsupervised method for segmentation. In the K-Means clustering algorithm, the random number of clusters is initialized automatically. A manual approach can initiate a specific number of clusters. Then, Each Cluster would have a center called the centroid. The algorithm performs then two steps alternatively: in the first step or Reassigning Points step, in which every pixel is assigned to the nearest cluster based on the distance of this point to the cluster’s centroid. In other words, in this step, each point or pixel would be assigned a cluster whose centroid has the shortest distance from this pixel or data point41. In the second step, Update Centroid, each centroid from each cluster is updated based on the mean of the pixels or data points in the same cluster.

In this experimentation, the k-means algorithm is employed in Python, which follows the following workflow:

-

1.

Reshaping image into a 2D array

-

2.

Convert the reshaped image into the float data type

-

3.

Defining the criteria to run the algorithm, which will decide the number of iterations and target accuracy

-

4.

Then, the number of clusters is assigned. In this case, the source image is in grayscale or colored, so the number of clusters will be two or N. Random centers of the defined number of clusters are also initialized.

-

5.

After applying all the variables, the k-means function is called cv.kmeans().

-

6.

The output from the cv.kmeans() is converted into an 8-bit data type.

-

7.

The output is in 2D shape, but the image is 3D, so the output is reshaped according to the dimensions of the input image.

Among all the methods, this can be considered the most robust approach, but having results in proximity to the Otsu methods (see Fig. 7a), this also fails in a few cases of noise and varying light conditions. A few samples of better and worse sets (visually interpretable) are shown in Fig. 7b.

Case-5 canny edge detection (not suitable as it detects only edges)

As the name suggests, Canny edge detection attempts to perform the segmentation based on the edges present in the images42. The theory behind the entire process can be summarized in 4 steps:

-

1.

Noise Reduction Generally, the algorithms dealing with the edges are susceptible to noise, so the first step in this algorithm would be to reduce the noise by using a Gaussian filter of size 5 × 5. As this method is a prerequisite for denoising the image and has an in-built function to perform the blurring, it is not required for a user to blur the image explicitly.

-

2.

Gradient Intensity Calculation The Sobel operator is applied to detect horizontal and vertical lines on the deblurred input image. The resulting two output images are then used to find the edge gradient and angle.

-

3.

Removal of Unwanted Pixels In this phase, the unwanted pixels not in the direction of the gradient are removed.

-

4.

Thresholding After removing the pixels, the thresholding is applied using minVal and maxVal. Any pixel more than the value of maxVal is surely part of the edge; otherwise, it is not. The pixels between these two values are then assigned based on their connectivity.

As the canny edge detection method deals with the edges of the entities in the image, it can not be considered a true segmentation technique and serves the worst output among all the candidate techniques. A few samples are shown in Fig. 8.

Case-6 watershed segmentation

The watershed segmentation algorithm is the final algorithm the authors deployed in the experiment. The watershed algorithm considers a grayscale image a topographic surface in which the high intensity(brighter regions) denotes the peaks, and the lower intensity (darker regions) denotes the valleys. Then, the water-filling process(labeling) starts in every isolated valley (local minima). As the water rises or the labeling grows, water from different valleys starts to merge depending on the peaks(gradients) nearby43. To prevent this, barriers are built where the water emerges. The water-filling process and barrier-making are continued until all the peaks are underwater. The barriers created to stop mixing the water are the segmentation results. This is the loose depiction of the analogy followed by the watershed segmentation. Some successful results of the watershed segmentation are depicted in Fig. 9a. Taking too much time to process a single image, this method can be considered the laziest, and the correct segmentation is not guaranteed either, as depicted in Fig. 9b.

Comparative analysis of cases

The case study carried out in section "Case analysis" vividly depicts the experimentation process that has been carried out on varied dataset samples.

These samples have been tested for various categories of image segmentation techniques: region-based, edge-based, thresholding, and clustering-based. To find the most suitable approach from the list of segmentation approaches, the experimental design was portrayed in a format where every sample segmented through different segmentation techniques could be visualized and observed simultaneously. To better accomplish the task of comparative analysis, a set of data samples was tested for the best segmentation results while performing segmentation with varied popular segmentation techniques. The results after the experimentation have been appended in the Fig. 10.

After various iterations and the number of comparisons, the authors concluded from the comparison experiment that no universal or single method can bring the best segmentation results over a set of input images. In Fig. 10, it is obvious from the visual interpretation that except for the Otsu binarization method, every other segmentation algorithm suffers and produces worse results than Otsu binarization. While the Global method fades important parts of the image, resulting in a loss of ROI (see Fig. 10), the Adaptive method adds noise to the target image. K-Means returns the same image without any operation, and Watershed shows over-segmentation and repetitive patterns on individual entities. Figure 10 presents segmentation failures across multiple techniques for challenging HME samples. Otsu’s method preserves edge details more effectively, while other methods degrade image quality. Global thresholding fades key strokes, Adaptive thresholding introduces noise, K-Means produces no meaningful segmentation, and Watershed results in severe over-segmentation with repetitive patterns. These visual differences highlight why no single method performs reliably across all cases.

In Fig. 11, among all the candidates of segmentation results, only the Global method produced results that can be considered usable; otherwise, other methods just failed because they distorted the entire image, causing a loss of information. It compares Global, Otsu, and Adaptive thresholding on various handwritten mathematical expressions. Otsu maintains symbol clarity and balanced contrast, Global thresholding causes loss of regions of interest in lighter areas, and Adaptive thresholding introduces scattered noise and uneven binarization. Pay attention to edge preservation, foreground–background separation, and noise patterns.

In Fig. 12, it is clear and visually interpretable that only the Adaptive method shows the best and most optimized results in this image case. Every other method suffers and produces a target image as half of the image is black or white-washed. Watershed segmentation also suffers and can’t detect other symbols. It illustrates the behavior of K-Means clustering on selected samples. It is observe that in most cases K-Means fails to differentiate foreground and background, producing outputs nearly identical to the input image. It demonstrates the method’s poor suitability for handwritten content, as it does not enhance symbol boundaries or segment meaningful regions.

A close inspection of candidate segmentation techniques in Fig. 13 clarifies that the Global and Otsu Methods show the same results, but KMeans produced the most accurate one. The watershed approach completely fails in this case. This shows results from region-based segmentation techniques. It examine how uneven stroke density and background variation cause inconsistent region formation. Some areas are merged incorrectly, while others remain under-segmented. This highlights the instability of region-based methods when applied to handwritten mathematical expressions.

However, in Fig. 14, which method produced the best result is unclear. Although global and Otsu methods look similar, they can not detect small characters. However, the Watershed segmentation method produces the best result in this case. It provides a side-by-side comparison of all segmentation methods evaluated. It provide differences in edge retention, noise levels, structural clarity, and stroke continuity across methods. The visual summary confirms that while Otsu performs relatively well, no single technique consistently produces optimal segmentation across diverse sample types.

The cases discussed in the comparison of various techniques provide conclusive insight. The conclusion can be explained as follows: no segmentation technique is the best performer for every case or every data sample from the dataset. Therefore, the best results from various cases are accumulated manually in the final dataset.

The comparative analysis is concentrated mainly on the classical and CNN-based segmentation techniques. Nonetheless, contemporary developments of transformer-based and attention-driven models have been very successful in segmentation and recognition tasks on cross-domain. The integration of such models as a comparative framework may be more of a holistic benchmark and legitimize the fact, that the offered CNN-based model performs at indeed the best of the best compared to the latest state-of-the-art methods.

Deploying segmentation using a neural network-based model

As none of the single segmentation techniques proved effective for all the dataset images, the authors must extend the boundaries for deploying and experimenting with the robust neural network-based segmentation model. This section has documented details for prerequisites for executing the neural Network based segmentation model, dataset preparation, splitting, training, testing and network architecture.

Prerequisites for model

The neural network model used for the segmentation requires specific steps and tasks to be done before the model’s training can be started. Each step and task is discussed in detail in the following subsections.

Preparing the ground data

The reason for trying out a neural network-based model is the observed fact in section "Experimentation" that no single segmentation technique stood out as the best fit for every image like that manually selected the best outcome with each of the experimented cases and labeled them as ground truth for the corresponding input images of data.

Padding and normalization

The raw images contained in the dataset are of varying sizes. For instance, some images can be size 256 × 300, and others can be size 400 × 400. However, the prepared model can take the image as fixed-size input. So, the authors used a technique called padding, in which we applied a border of fixed width around the input image in white or pixel value 255. The padding methodology works in a way that is similar to the given input image, which is of height 256 and width 300, and the network model accepts the input of dimension 512 × 512. The pixels to be padded are evaluated by deploying padding algorithm works as follows:

where IN_H represents the height of the input image.

IN_W denotes the width of the input image.

h denotes the number of pixels to be added around the y-axis of the image.

w denotes the number of pixels to be added around the x-axis of the image.

H is the height of the image compatible with the Network.

W is the width of the image compatible with the network.

fh_T denotes the final pixel values around the y-axis (height) of an image that would be added on the top.

fh_B denotes the final pixel values around the y-axis (height) of the image that would be added on the bottom.

fw_L denotes the final pixel values around the x-axis (width) of the image that would be added on the left.

fw_R denotes the final pixel values around the x-axis (width) of the image that would be added on the right.

Then the pixels are added by calling np.pad (a padding function) of numpy library.

np.pad(img, pad_width = [(fh_T, fh_B),(fw_L, fw_R)], constant_values = 255).

Thus, adding the white pixels around such non-compatible images would have uniformity and make them compatible for the network to process. The glimpse of the padded images are showcased in Fig. 15.

Normalization is a preprocessing technique used to standardize data. In other words, having different sources of data inside the same range. Not normalizing the data before training can cause problems in our Network, making it drastically harder to train and decreasing its learning speed. Thus, it becomes crucial to perform effective normalization. Thus, the conversion of the input images list into a numpy array is followed by the normalization, which would limit the value of each pixel in the range of (0,1). The normalization is needed as the pixels in the images have values that may behave as outliers. So, normalizing the loaded images would fix these issues and serve as a memory saver (in some memory-intensive computations).

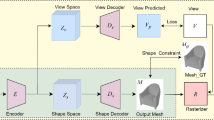

Model structure

The architecture of the proposed model depicts the arrangement of the persisting deep learning tools like the convolutional layer, max pooling layer, and activation in a form that could accomplish the segmentation task n. The architecture of the proposed neural Network-based model follows the encoder-decoder structure in major ways. The layered structure of the model will take an image as an input. This input would be converted into a high-dimensional vector containing the features from the input. Then, the decoder would extract those features and generate a new segmented image based on those extracted features. The main components of the model include the input block, encoder block, bridge layer, decoder block, and output block. Model structure is represented in Fig. 16.

Encoder Block The input block contains the layers Conv2d, BatchNormalization, Activation, Conv2D, and BatchNormalization. After the input block, the encoder part of the model consists of 3 blocks, and each block contains layers: MaxPooling, Conv2D, BatchNormalization, Activation, Conv2D, and BatchNormalization, in the given order. An activation layer maintains the connection between each encoder block.

Bridge Connection The encoder is connected to the decoder by a bridge that is a block that consists of MaxPooling, Conv2D, BatchNormalization, Activation, Conv2D, BatchNormalization, Activation, and Conv2DTranspose layers.

Decoder Block The succeeding decoder structure also consists of 3 blocks, each containing the layers Conv2D, BatchNormalization, Activation, Conv2D, BatchNormalization, Activation, and Conv2DTranspose. The kernel size in all the Conv2D layers of the entire Network is 3 × 3. All the Conv2DTranspose layers contain the kernel size of 2 × 2. The MaxPooling layers have a size of 2 × 2 in the entire Network. The activation function is RELU for the entire network except for the output layer, which has the activation function of Sigmoid. The number of filters produced by the first two convolutional layers of the input block is 16. Both the layers in the first block of the encoder produce 32 filters each. The subsequent blocks contain the Conv2D layers, which produce the number of filters as 64 128. The bridge contains the COnv2D layers, which have the number of filters as 256. All three blocks in the decoder contain the number of filters in their Conv2D layers in decreasing order as 128, 64, 32. The output block has the Conv2D layers with several filters, such as 16.

Model initialization

The Initialization of the model with acquired parameters is a task of significance, where the model has been initialized with structure, dimensions, and parameters. The units and objects involved in model initialization are discussed in detail in the following sections.

Input–output parameters initialization

The build_model function was called at the onset and had two parameters (input_shape and n_classes). The input shape parameters hold the values for the height of the input image, the width of the input image, and number of channels in the image.

Hyperparameters initialization

Hyperparameters are one of the most crucial entities defining the model’s performance during training and post-training phases. These parameters do not change during the training phase, and they determine the various important characteristics like learning rate, error function, epochs, etc. These parameters are the foundation for training the model. The model’s hyperparameters have been initialized, and the learning rate for the model has been initialized at 0.001. The optimizer Adam has been predefined with the learning rate of 1e-3). In this phase, the Adam optimizer is used to modify the weight and learning rate to reduce the overall loss and improve the accuracy. Loss is categorical_crossentropy, and mEtrics is ['‘accuracy’']. The metrics accuracy’' is used to evaluate the performance of the model. The metrics used in the model are similar to the error functions. Still, they differ only in that the values of the error functions are used to adjust the weights by the optimizer function. Still, the values produced by the metrics are used to visualize the model’s performance. So, the values of the metrics do not contribute to manipulating the model’s internal parameters, which determine the accuracy and performance but are used as abstract functions that give insights about the various aspects of the model, like accuracy, loss, etc.

Callbacks initialization

The callback function EarlyStopping, from the Tensorflow library, has been initialized with the parameters named min_delta, which indicates the minimum change in the metrics that must occur in the training phase to keep training on, patience, which defines the number of epoch to wait even their is not change defined according to min_delta, restore_best_weigths is set as True to save the model from the epoch it achieved the best accuracy.

EarlyStopping function comes in handy in scenarios like when there is the possibility of potential overfitting, and the dataset contains a lot of noise. This callback function saves time by saving the best weights of the best-performing epoch, even if those epochs have been passed.

Tensorboard callback is also used to save the log from visualizing the training trends after completing the training phase. This callback saves each log with associated values of the properties like accuracy, loss, time, date, etc. These saved logs are then utilized to plot the interactive graphs to get deeper insights into the training trends of the model.

Though the results of segmentation in the study are promising and resource efficiency and processing speed are essential in such a situation as digital education platforms or OCR applications. It should be profiled in the future to determine the training time, inference latency, and hardware usage of the model to determine its appropriateness to be deployed in time-sensitive or resource-constrained systems.

Training and testing model on validation set

The entire dataset is split into two parts named train_split and test_split. The data is divided between both splits in the ratio of 80/20, i.e., 80% of the data belongs to the training set, and 20% belongs to the validation split.

Training After splitting data in the mentioned ratio, the entire dataset, training, and testing split are sent for training by using the model.fit() function. The batch size is kept at 5, meaning the number of images in each batch would be 5. The batch size, number of batches, and size of the dataset follow the relation:

Verbosity is set as 1, which indicates that model training will print the logs during the training phase of the model. Number of epochs is set as 5. Validation data, i.e., 20% of the entire data, is also passed as validation_data parameter. Callback functions are initialized as the EalyStopping and tensorboard_callback.

MEAN IOU SCORE: Mean IoU = 0.79753053

Training Logs analysis The logs generated during the training phase are plotted in a graph, as shown in Figs. 17, 18, 19 and 20. It shows the graph of the model performance with the loss function as the parameter under consideration for the training and testing split. As shown in the graph, the training curve of the model falls drastically from the beginning of Epoch 1 to Epoch four completion. After epoch four, the model’s loss decreased moderately on the training set. However, in the case of a validation split, the losses decrease sharply for the first epoch, but the slope decreases between the first and second epochs. The losses again increase slightly between the third epoch and the fourth one. After that, the degradation is moderate and gradual. The loss curve of the validation split then follows the path of loss on the training split and coincides with the loss curve of the training split.

Figure 17, 18 and 19 represents the model’s accuracy trends over the training and validation split. The accuracy curve on the training split is shown in red, following the steep growth from the first epoch to the 4th one. The learning after the 4th epoch moderates, and the growth is less steep. The growth in the achieved accuracy between the first and 4th epoch is exponential, but after epoch four, the model’s accuracy over training split grows moderately. However, such is not the case with the validation split.

In the validation split, the model already maintains the lead, shown by the blue curve, on the accuracy of the training set. The lead made by the accuracy on the validation split is retained till epoch nine, as at around epoch ten, the curves intersect, and the accuracy over the validation split starts declining. As the early stopping constrains the model’s training, the model stops training with attained saturated accuracy of 96.9%.

Figure 19a shows the model’s loss on the validation set against each iteration. A single iteration is entirely the processing of a single batch. The model’s losses dip sharply after 100 iterations. The trend continues till the 2200 iteration. However, following 2200 iterations, the model’s loss decreases sharply till the 3000th iteration, and then the losses dip again with a huge steep. The decrease in losses indicates that the model’s prediction of the unseen data is getting closer to the ground truth of the corresponding input image. Nevertheless, till the 6500th iteration, the curve gets more aligned with the horizontal axis, which means the losses get stable, and hence, training stops to avoid the potential case of overtraining.

The accuracy trend of the model on the validation split can be analyzed similarly. Figure 19b demonstrates the model’s accuracy metrics on the validation split. Though the model’s training projectile is inconsistent with the increasing number of iterations, the model achieves an accuracy of 96.9% at the end of the training. Around 6.5 K on the x-axis, it can be interpreted that as the model’s accuracy starts declining with the higher negative inclination, the model’s training stops by invoking early stopping, saving the model from the case of learning noise or overfitting.

Testing the model

At the beginning of the experimentation, the authors split the entire data into two parts: training set and testing set viz. The training set is then further split into two parts: training split and validation split. The first part, or training set, is to train the model. The model is trained on the training split and then validated on the validation split. The second or testing split is the data utilized for the post-training or deployment phases. This data consists of images unseen to the model, and now, the model will attempt to segment this unseen data. This dataset has 5000 images from the Aidapearson dataset that are unseen to the model.

The unseen images are read from the directory by iterating over it. Each image is read in grayscale mode using the library, cv2, and then, as the model is trained on the images by normalizing the input image, it is normalized to bring each pixel in the range [0,1]. The original read image has pixel intensities between 0 and 255. Still, after normalizing or dividing each pixel by 255, the corresponding result would have the images in which each pixel would have an intensity between 0 and 1, inclusive. Then, the normalized image or numpy array is sent to the model to be predicted, and then the output from the model would be a numpy array in which each pixel would be in the range of 0 and 1. The normalized outcomes would not be interpretable, so each pixel must be multiplied by 255 so the image can be displayed and interpreted. After performing the operations, the outputs would be visible as shown in Fig. 20.

Result analysis

After the training, the meanIoU method checks the model’s accuracy on the test split. In this method, the input image from the test split is passed through the Network, and then the output is superimposed on the ground truth of the corresponding input image. The superimposition of the predicted image and ground truth determines how close the predicted output is to the expected one. If the ground truth image is superimposed completely by the predicted image and the predicted image’s foreground covers the foreground of the ground truth image perfectly, it is considered to have high accuracy. The MeanIoU is defined as the Mean of Intersection over Union, or it can be attributed to the ratio of the intersection of the two sets and their union. Considering both the images as different sets and if the ratio of their intersection and union is 1, they are perfectly overlapping and can be considered the same image. Anything below one is considered to have some difference between both the sets and images represented in Fig. 21a–d.

To evaluate the trained model on unseen data, an approach is employed in which 2000 images are taken from each dataset. The taken images are split into 10 batches, each containing 200 images. Then, each batch is passed on to the model individually, and the mean IoU score is calculated for each batch. The pattern made by the line in the graph indicates the achieved mean IoU score on the dataset.

Plotting the graph for various batches against the accuracy, the average Mean IoU score for the CROHME14 dataset is 79.4%. Similarly, the interpretation of the graph on the CROHME16 dataset indicates the average mean IoU score of 83.5%. The average mean IoU score for the CROHME19 dataset is 81.3%, the third highest of all the scores. HASYv2dataset’s mean IoU score got the highest average percentage of mean IoU score, i.e. 89.6%. The mean IoU score achieved on AidaPearson’s dataset is 74.6%, the lowest.

The calculated mean IoU score values for the CROHME14 dataset are plotted in a graph as shown in Fig. 21a. The average Mean IoU score for this dataset is 79.4%. Figure 21b shows the trend of the mean IoU score of the model on the CROHME16 dataset. From the pattern, it can be inferred that the score evaluation on the batches does not follow an increasing or decreasing pattern. The rise and dip in the subsequent batches put constraints on generalizing the trend. Though this curve is inconclusive, the distribution of the images over the batches greatly impacts the trend—the average mean IoU score achieved on this is 83.5%. In the case of the CROHME19 dataset, the fluctuations in the graph of mean IoU scores are quite high, attributed to the uneven dividing of the image samples over the batches. The sample variations in each batch can also be counted as a factor for this variance in the curve. Among all the datasets, HASYv2dataset’s mean IoU score got the highest average percentage of mean IoU score, i.e., 89.6%. Though the pattern shown in Fig N does not give any specific insight into the model’s accuracy, redistribution of the image samples over the batches can alter the achieved mean IoU percentage score. Among the member datasets, AidaPearson’s dataset achieved the lowest Mean IoU score over the batches of distributed images. The mean IoU score achieved on this dataset was 74.6%. As with other datasets, the curve of the mean IoU score does not give any specific insight into predicting the projectile, but redistribution of the image samples can rearrange the generated graph. The difference in the reported mean scores of the IoU between the datasets (around 74 percent on AidaPearson and 83 percent on CROHME 2016) may indicate certain dependence of the proposed method on the dataset. This variability could be a sign that the model is more adaptable to the dataset-specific aspects like the resolution, diversity of symbols and the quality of annotations. The experiment on cross-dataset testing or transfer learning might also help establish the strength of the segmentation model in terms of unseen or heterogeneous data sources.

The key performance measures that were used to make a comprehensive comparison between the current methods of segmentation and the proposed method of segmentation like the Mean Intersection over Union (IoU), accuracy and visual quality assessment were used. Classical algorithms such as Global Thresholding, Adaptive Thresholding, Otsu Binarization, K-Means, Canny Edge Detection and Watershed Segmentation were tested on various benchmark datasets such as CROHME14, CROHME16, CROHME19, HASYv2 and AidaPearson. Among them, Otsu and K-Means showed moderate scores in the range of 61–70 in terms of the IoU and the proposed CNN-based segmentation model performed well in each of the datasets with the Mean IoU in the range of 74.6–89.6. This enhancement goes to show that the model is better in generalizing with diverse data, illumination changes, and fine-grained symbol edges. Moreover, the precision of 96.9%, obtained in training and validation, justifies efficiency of the offered strategy in comparison with classical methods of segmentation, which were ineffective in case of noise and contrast change. The comparison confirms that the proposed neural model has more consistent and accurate segmentation and is a more reliable option when it comes to handwritten mathematical expression segmentation.

Whereas the suggested neural network-based segmentation methodology has shown a high level of performance in the isolation of handwritten mathematical symbols, its usage in a full-fleet end-to-end handwritten mathematical expression recognition (HMER) pipeline has not been studied in depth. The future researches should aim at integrating the segmentation process with symbol recognition and structural analysis modules to determine how effective the method is in a holistic recognition framework. This kind of integration would assist in finding out how practical the proposed model is in automated mathematical understanding systems. To get the failure instances of the model, it is important to analyze the errors of the model in a detailed way and notably when dealing with overlapping symbols, ambiguous strokes or multi-level structures of mathematics. A set of mis-segmented outputs and the heatmaps could be visually examined to identify systematic vulnerabilities in the perception of the model on the boundaries of symbols. A combination of interpretability analyses would not only assist in the refinement of the segmentation network, but would also contribute to the transparency of the segmentation network and its increased reliability in practical educational or OCR-based applications.

Conclusion and future recommendation

The authors attempt to resolve the various issues associated with a wide range of segmentation techniques in the entire research procedure. From the basic techniques like Global Thresholding to the more advanced techniques like K-Means clustering, which is unsupervised, the authors ascertained that there does not exist any single method that can be attributed as the most optimized and the best method to perform and produce the best results. While basic methods struggle with subtle change, more advanced methods like KMeans clustering may seem immune to such changes. Still, the higher degree of lightning condition variations also renders such methods obsolete and inefficient. On the other hand, the method introduced by the authors, which employs an end-to-end learning approach, is immune to such changes as it learns from the best ground truth prepared. The subtle changes in the lighting condition do not affect the introduced method, which is self-explanatory from the achieved Mean IoU score on various datasets likeAidaPearson’s dataset, HASYv2, etc. The introduced robust model is insensitive to various intricate problems, such as varying contrast, brightness, sharpness, etc., to a certain degree of change. The authors also introduce the concept of the customized padding method at a preprocessing level, which deals with the problems related to the dimensionality of the input samples from the dataset. The visual representations in the testing section of the article indicate the accuracy achieved by the model on a few samples. Though the model is robust and unique in its approach to handwritten mathematical expression segmentation, it also depends on pre-assumed conditions like the quality of the data it is being trained on, the depth of the Network, and outliers of the intricate values of the image properties. Extreme variance in the input image samples may reduce the accuracy by a great value. This can be addressed by increasing the depth of the Network and training the model on high-end systems mounted with larger capacity modules. The data quality also can be monitored manually to enhance the model’s accuracy. Currently, the model works only on single-channel images, but serious efforts can be put into extending this model to support multi-channel images.

Data availability

Data will be available on request from the corresponding author

References

Wang, Z., Wang, E. & Zhu, Y. Image segmentation evaluation: A survey of methods. Artif. Intell. Rev. 53(8), 5637–5674 (2020).

Hoeser, T. & Kuenzer, C. Object detection and image segmentation with deep learning on earth observation data: A review-part i: Evolution and recent trends. Remote Sens. 12(10), 1667 (2020).

Wang, R. et al. Medical image segmentation using deep learning: A survey. IET Image Process. 16(5), 1243–1267 (2022).

Sharma, R. & Kukreja, V. Image segmentation, classification and recognition methods for comics: A decade systematic literature review. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 131, 107715 (2024).

Song, Y., Ren, S., Lu, Y., Fu, X. & Wong, K. K. L. Deep learning-based automatic segmentation of images in cardiac radiography: A promising challenge. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 220, 106821 (2022).

Hassan, E., Saber, A., El-Sappagh, S. & El-Rashidy, N. Optimized ensemble deep learning approach for accurate breast cancer diagnosis using transfer learning and grey wolf optimization. Evol. Syst. 16(2), 59 (2025).