Abstract

Using gas-lubricated pistons in Stirling cryocooler can reduce wear between the piston and cylinder, enhancing equipment reliability. This paper proposes a locally porous media-type gas-lubricated piston and investigates the regulatory effects of porous media structural parameters, supply pressure, and gas film thickness on the piston’s static performance (flow rate and gas film load capacity).Aims to further improve the cooling performance of the Stirling cooler by optimizing the static characteristics of the piston.The results indicate that as the diameter of the porous media increases (2–5 mm), both the bearing capacity and the gas consumption curves continuously increase. Under the same diameter, a structure with a larger length-to-diameter ratio can reduce flow resistance losses and achieve greater bearing capacity. The gas supply pressure (0.2 MPa-0.6 MPa) shows a linear positive correlation with the static performance of the piston. The gas film thickness of 10–20 μm is the optimal range for energy efficiency, balancing both bearing capacity and processing feasibility. The experiment set up a piston control group (with piston flow rates of 6.78 × 10− 6m3/s, 1.02 × 10− 5m3/s, and 2.14 × 10− 5m3/s, respectively), and by monitoring the cooling performance of the same Stirling cryocooler, a quantitative mapping relationship between piston flow rate and the cooling performance of Stirling cryocooler was established. The results show that the cooling rate of Stirling cryocooler with a piston flow of 6.78 × 10− 6m3/s is significantly improved compared to the one of 2.14 × 10− 5m3/s. At 20 W@-152.6℃, the COP is 0.1; at 86 W@-88.0℃, the COP is 0.43, which is better than the cooling performance of the other two experimental groups. Therefore, it is considered feasible to optimize the efficiency of Stirling cryocooler by regulating the piston flow, providing a technical reference for the structural optimization and performance improvement of the Stirling cryocooler.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The free-piston Stirling cryocooler is widely used in aerospace, infrared detection and cryogenic medicine due to its compact structure and high efficiency1,2. However, with the establishment of the International Space Station, the requirements for its longevity and reliability are getting higher and higher. Mechanical wear, working fluid leakage, fatigue fracture, working fluid pollution and environmental stress damage are the main factors causing the failure of cryocooler, especially the wear between the piston and the cylinder, as well as the working fluid pollution and gas path blockage caused by abrasive debris3,4. Hydrostatic gas bearing technology enables non-contact operation between cylinder and piston, avoiding contamination and significantly increasing service life, making it ideal for high-reliability Stirling cryocooler5,6.

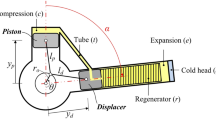

A structure of a gas-lubricated piston7. 1-Piston rod; 2-Guide piston; 3-Valve plate seat; 4-Valve plate; 5-Piston insert; 6-Push piston.

As shown in Fig. 1, it is a structure of a gas-lubricated piston. The direction of the gas flow is indicated by red arrows. Structure 3 and 4 are fixed onto structure 2. When the gas overcomes the spring force and friction along the inlet and pushes 4 open, it enters the high-pressure chamber inside the piston. The gas flow circulates through the tiny internal gaps, then flows out through the throttling and pressure-reducing effect of the throttle elements, forming a continuous film with a certain load-bearing capacity in the clearance between the piston and the cylinder. The piston is suspended by the support of the gas film, thereby avoiding contact between the cylinder and the piston8. Structurally, compared to leaf spring supports, it saves more internal space, which helps the Stirling cryocooler develop toward lightweight and low-cost directions. Research shows that the gas consumption of gas-lubricated pistons accounts for about 2% of the gas involved in the refrigeration cycle during the operation of the cryocooler. This can extend the cryocooler’s lifespan to over 10 years and greatly improve its stability2,9.

At present, the research on gas-lubricated piston Stirling cryocoolers is usually based on the node analysis method of Sage software, the one-dimensional steady-state cycle model, and the experimental method is combined to obtain the performance of the cryocooler with gas-lubricated piston10. For example, Zhang et al.11 successfully developed and tested an aerospace-grade gas-bearing Stirling cryogenic cooler with a cooling capacity of 22.5 W @ -87℃ at a sine wave drive input power of 99.1 W. The reliability and life of the cryocooler were tested and estimated. The life calculated by the linear extrapolation method was more than 172 800 h, which met the requirements of the reliability and life of the Space Station(6.67years). However, this research method focuses on the analysis and calculation of the internal operation process and parameters of the cryocooler, and does not focus on the piston itself, and cannot study the joint mechanism of the gas-lubricated piston and the cryocooler. Therefore, many researchers propose to study only one component, the gas-lubricated piston, and analyze the factors affecting the static characteristics of the gas-lubricated piston by focusing on the flow characteristics of the fluid through fluid simulation software. Most researchers have used Fluent software to build small-hole throttled gas-lubricated piston models, and some have used COMSOL software to build their studies. The results show that increasing the diameter of the orifice and the inlet pressure can improve the bearing capacity of the gas bearing, so as to achieve a stronger piston automatic centering ability. However, due to the increase in the fluid flow rate of the gas gap, the gas consumption of the piston will be increased. Therefore, for the structural design of gas-lubricated piston, it is necessary to comprehensively consider the influencing factors12,13. It is also proposed that when the bearing capacity is insufficient, priority should be given to changing the gas film gap and the diameter of the orifice, and when the bearing capacity does not meet the demand after the optimal value appears, the inlet pressure and the number of orifice holes should be considered14. However, most of the above-mentioned theoretical studies are based on the type of small hole throttling, in which the required small holes and some matched step holes are difficult to process and easy to block. Considering the more uniform pressure distribution of porous media types, the use of the mounting process, the ease of operation and the low cost are of particular concern.

In this paper, the local porous media type gas-lubricated piston is taken as the research object, and the Fluent module in Ansys software is used to simulate the expansion model of the gas film, study the factors affecting its flow rate and bearing capacity, and determine the optimal geometric parameters of the gas-lubricated piston. Since the experimental method used by the predecessors focused more on the exploration of the performance of the whole machine, and did not specifically explore the influence of the static performance of the piston (bearing capacity and flow rate, etc.) on the cryocooler, so the experimental test was carried out in this paper. Since the piston flow rate is easier to obtain relative to the bearing capacity, the control variable method is used to replace the gas-lubricated piston with different flow rates on the same cryocooler to study the effect of the gas-lubricated piston on the cooling performance of the refrigeration machine. The purpose of this paper is to provide a reference for optimizing the piston structure and improving the cryocooler performance of the subsequent Stirling cryocooler.

Model construction and theoretical analysis

Structural model

This section focuses solely on the study of the gas-lubricated piston, primarily using fluid simulation to analyze the factors affecting the static characteristics of the gas-lubricated piston. In general, we should minimize flow consumption while achieving sufficient bearing capacity in order to reduce energy consumption and gas supply costs. For the convenience of calculation, this paper simplifies the gas-lubricated piston model as shown in Fig. 2, and establishes a coordinate system with point A as the origin. Figure (a) is a structure of the gas-lubricated piston, Figure (b) is its axial section view, and Figure (c) is the unfolded model of the film domain. In Figure (c), the green surface represents the outlet, and the gas flow direction is indicated by red arrows. The piston has four throttling holes evenly distributed around its circumference. By inserting porous cylindrical plugs into the throttling holes, a local porous media throttling is formed. The purpose of adopting a symmetrical structure is to ensure that the piston has the same characteristics when operating in both directions in the future. h0 represents the gap thickness between the piston and the cylinder. Inwall and outwall refer to the inner and outer walls of the gas film model, respectively. \(\:{P}_{in}\) indicates the supply pressure, while the pressure in the exhaust area is denoted as \(\:{P}_{\text{out}}\). The specific parameters of the piston model are shown in Table 1.

Governing equations

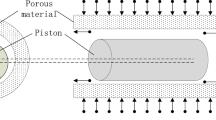

Figure 3 is a cross-sectional view of a single porous medium and its nearby region, corresponding to Fig. 2. The part circled in red represents the model’s fluid domain, while the black area is set as a porous media model. The positive direction of the z-axis corresponds to the direction of fluid flow through the porous media. Where Din represents the diameter of the gas inlet, h represents the thickness of the gas film, \(\:{D}_{p}\) is the diameter of the porous medium cylinder (m), \(\:{L}_{p}\) is the length of the porous medium cylinder (m), \(\:{P}_{in}\) and \(\:{P}_{0}\) represent the initial inlet pressure and the pressure after passing through the porous medium, respectively.

The flow of gas in porous media follows Darcy’s law, and thus the velocity of gas in all directions within the porous medium under a Cartesian coordinate system is15,16:

Here, \(\:{u}_{x}\),\(\:{u}_{y}\) and \(\:{u}_{z}\)represent the flow velocities of the gas in the three directions within the porous medium (m/s). \(\:{\phi\:}_{x}\),\(\:{\phi\:}_{y}\) and \(\:{\phi\:}_{z}\) represent the permeability in different directions within the porous medium (m2). In this context, it is specified that \(\:{\phi\:}_{x}\)=\(\:{\phi\:}_{y}\)=\(\:{\phi\:}_{z}\)=\(\:{\upphi\:}\). \(\:\mu\:\) is the hydrodynamic viscosity coefficient (Pa·s). \(\:{P}_{i}\) is the gas pressure in a porous material (Pa), and the negative sign indicates that the fluid flows from the high-pressure region to the low-pressure region.

Since the system satisfies steady state, the equation for the conservation of mass per unit area in the direction is:

Combining the above two equations, the pressure gradient of the fluid in the z-direction in a porous medium is 0, so the flow rate through a single porous medium is:

\(\:{A}_{p}=\frac{\pi\:{D}_{p}^{2}}{4}\) is the effective cross-sectional area of the fluid passing through a porous medium. When setting up a porous media model in Fluent, you need to enter its viscous resistance coefficient \(\:\alpha\:\) and inertial drag coefficient \(\:{C}_{2}\) which are obtained from the following Ergun equations17:

where \(\:\varDelta\:P\) is the pressure drop caused by passing through the porous medium (Pa), \(\:\alpha\:\) is the viscous resistance coefficient (m− 2), \(\:{C}_{2}\) is the inertial resistance coefficient (m− 1), and ε is the porosity. \(\:{d}_{p}\)is the microscopic mean particle diameter of the porous medium (m).

The pressure distribution in the gas-inflated membrane can be described using the Navier-Stokes equations. By combining the equations of state and the continuity equation from fluid mechanics, and neglecting the effects of inertial forces and gravity, it can be concluded that the pressure distribution in the gas-inflated membrane conforms to the following dimensionless form of the Reynolds equation18:

Where \(\:{{\Lambda\:}}_{x}=\frac{6\mu\:{v}_{x}R}{{h}_{0}^{2}{P}_{a}}\), \(\:{{\Lambda\:}}_{y}=\frac{6\mu\:{v}_{y}R}{{h}_{0}^{2}{P}_{a}}\), \(\:\sigma\:=\frac{12\mu\:vR}{{h}_{0}^{2}{P}_{a}}\), \(\:\overline{x}=\frac{x}{R}\), \(\:\overline{y}=\frac{y}{R}\), \(\:\overline{h}=\frac{h}{{h}_{0}}\), \(\:\overline{P}=\frac{P}{{P}_{a}}\), \(\:\overline{t}=\frac{T}{\omega\:}\).

There, \(\:\text{R}\) is the gas constant, \(\:\text{T}\text{}\)is the absolute temperature, and \(\:\text{v}\) is the linear velocity of the particle in the circumferential direction. Here, \(\:\overline{\text{x}}\),\(\:\overline{\text{y}}\),\(\:\overline{\text{h}}\),\(\:\overline{\text{P}}\),\(\:\overline{\text{t}}\) are dimensionless forms of the variables \(\:\text{x}\),\(\:\text{y}\),\(\:\text{h}\),\(\:\text{P}\),\(\:\text{t}\) respectively. \(\:\overline{\text{h}}\) represents the gap between the piston and the cylinder, and \(\:{\text{h}}_{\text{0}}\) represents the average gas film gap. Since the bearing acts as \(\:{\varLambda\:}_{x}\)a piston, its circumferential velocity \(\:{\text{v}}_{\text{x}}\) and axial velocity \(\:{\text{v}}_{\text{y}}\) are much smaller than the gas flow velocity in the gas film, so it can be considered that \(\:{\varLambda\:}_{x}\) and \(\:{\varLambda\:}_{y}\) are 0.At steady state, the time-dependent term is zero. Therefore, Eqs. (2–7) is simplified as:

From the above equation, the gas pressure distribution \(\:P\) can be solved.

The pressure on the inwall and outwall surfaces of the gas film is integrated, and the supporting force of the air film on the piston is obtained through the force analysis, i.e. the bearing capacity of the piston.

A represents the surface area of the air film. From the fluid continuity, the volume flow rate of the gas film (volume flow rate of the piston) can be obtained as:

3D modeling and simulation environment setup

This article utilizes Ansys-student 2023 R1. In order to conveniently set up a porous media fluid model in Fluent, this paper adopts the unfolded model of the film domain. As shown in Fig. 2(c). Since the model has symmetrical properties, a symmetrical boundary is used to simplify the model to a quarter model, as shown in Fig. 4. The entire fluid domain is divided into three parts: the porous media domain, the inlet hole region, and the gas film region. The porous media is located at the center of the rectangular model. The red circular surface in the figure is set as the inlet, and the green boundary is set as the outlet. The left and right boundaries use symmetric boundary conditions.

Since the thickness of the air film is on the micron scale, generating accurate and efficient finite element meshes for such high aspect ratio geometrical models requires the use of swept meshing. And the block meshing method is adopted to use regular rectangular mesh. The grid division details are shown in Fig. 5. To verify grid independence, calculations were performed with a gap of 15 μm, an air supply pressure of 0.4 MPa, and no eccentricity. The results are shown in Fig. 6. It was found that when the number of mesh elements increased to 111,287, the calculated bearing capacity roughly increased to 4.94 N. Subsequently, the number of mesh elements was further increased to 3 × 10⁵, and the calculated bearing capacity was 4.93 N with a calculation error of approximately 0.2%, indicating that once the number of mesh elements reached 111,287, the calculation results had stabilized. Therefore, this mesh density scheme will be used in subsequent simulations.

Import the completed meshed model into Fluent software, set the solver parameters based on the characteristics of the film flow field, and follow the simulation procedure shown in Fig. 7, with specific parameter settings as listed in Table 2. It is important to note that the black porous media region in Fig. 4 needs to be set separately in the “Unit Region Conditions” in Fluent, and selecting the “Porous Media Model” option requires entering the viscous resistance coefficients \(\:\alpha\:\) and inertial resistance coefficients calculated \(\:{C}_{2}\) by Eqs. (2–4) and Eqs. (2–5). In this article, the inlet and outlet are set as pressure boundaries. In order to improve the convergence speed and make the operation stable and accurate, the SIMPLE algorithm is used in this paper. The calculation stops when the iterative residual reaches 10− 6, indicating that the model has converged. The lower the residual, the closer the previous calculation result is to the subsequent one, and the more accurate the obtained value is.

Results and discussion

Effect of supply pressure

Figure 8 shows the effect of supply pressure on the static performance of the piston. When only a single variable is \(\:{P}_{in}\), the gas film bearing capacity and gas flow rate increase linearly as their values increase. This is because the increase in inlet pressure increases the flow into the fluid domain, which in turn increases the load capacity of the gas film. Figure 9 is a pressure cloud map. It is evident that the color of the pressure center darkens as the \(\:{P}_{in}\) increases, especially when the \(\:{P}_{in}\) is greater than 0.4 MPa. According to the study19, when the \(\:{P}_{in}\) exceeds a certain range, the large pressure drop inside the gas film and the enhancement of the compressibility of the fluid will cause eddy currents in the area near the porous medium outlet hole, resulting in flow separation and deterioration of the static characteristics of the gas-lubricated piston.

Effect of film thickness

The key to non-contact gas-lubricated pistons lies in the size of the clearance. If the gap is too large, due to the large pressure difference between the pressure chamber and the back chamber, it will cause gas leakage to the back chamber and the sealing effect will deteriorate. The gap is too small and the piston does not have enough bearing capacity. We demonstrated the static performance of the piston with different clearance sizes, and the results are shown in Fig. 10. As can be seen from the figure, with the decrease of the thickness of the gas film, the bearing capacity increases nonlinearly, while the flow rate decreases, and the supply pressure has a blessing effect on this change.

Observe Fig. 11, comparing the gas film pressure cloud at 4 × 10⁵Pa. When the air film gap h = 5 μm, the extremely thin gap space causes the fluid to rush out from the porous medium outlet without having enough buffer distance to achieve smooth pressure diffusion, resulting in a significant pressure discontinuity at the edge of the high-pressure region. This sudden pressure change can cause the high-speed airflow within the gap to be unable to flow smoothly along the wall, generating vortices that detach from the wall, with the vortex centers forming low-pressure zones due to the sparse gas. In the range of h ≤ 10 μm, it falls under high-precision machining, which demands extremely high standards for both machining instruments and the materials of the workpieces. Therefore, the clearance is generally designed to be above 10 μm. Due to practical requirements, the piston needs to have a load-bearing capacity of at least 3.67 N at 4 × 10⁵Pa to support the piston assembly and the mover assembly; therefore, the clearance must be less than 20 μm. The gas film thickness of 10–20 μm is the optimal range for energy efficiency, balancing both bearing capacity and processing feasibility. The clearance between the piston and cylinder used in subsequent experiments is 15 μm. When the pressure is 0.4 MPa, increasing the clearance from 5 μm to 15 μm results in a 27% loss in load-bearing capacity, which is within an acceptable range.

Effect of porous media parameters

The fixed gas film thickness \(\:h\) was 15 μm, the inlet pressure \(\:{P}_{in}\) was 4 × 105 Pa, and the influence of the structural parameters of porous media on the bearing capacity and flow rate of the gas film was studied. Figure 12 indicates that increasing \(\:{D}_{p}\) and the porosity of the porous medium leads to an upward trend in both gas film load-bearing capacity and volumetric flow rate. As \(\:{L}_{p}\) increases, the load-bearing capacity and flow rate of the air film show a decreasing trend. This is because increasing \(\:{D}_{p}\) and the porosity of the porous medium enlarges the effective cross-sectional area through which the fluid flows, thereby increasing the gas flow into the gas film and correspondingly enhancing the load-bearing capacity. If \(\:{L}_{p}\) increases, the flow resistance of the fluid within the porous medium will increase, meaning that the flow rate through the cross-section per unit time will decrease. Equations (2–3) shows that the volume flow rate is proportional to \(\:{{D}_{p}}^{2}\) and inversely proportional to \(\:{L}_{p}\). Comprehensive analysis suggests that when selecting porous media, structures with a higher length-to-diameter ratio should be preferred for the same diameter. When the porous medium has a diameter of 2 mm and a length of 2.8 mm, the piston bearing capacity is 4.93 N and the flow rate is 1.1 × 10⁻⁵m³/s, which meets the load requirements of the cryocooler and results in the lowest flow loss. Therefore, this structural parameter is used in subsequent experiments.

Figure 13 shows the gas film pressure distribution of the quarter model at different diameters of the porous media. It was observed that the pressure peak appears in the central area of gas emission in the porous medium, and the pressure gradient diffuses and decays from the center to the surrounding area. It more intuitively demonstrates that as the diameter of the porous medium increases, the area of the central high-pressure region also increases.

Experimental research

The high-pressure gas discharged from the compressor is partially used for the refrigeration cycle, while the other part is released through a throttling element into the gap between the piston and the cylinder, forming a gas film. To investigate the feasibility of optimizing the efficiency of a refrigeration machine in cryogenic regions by controlling the flow of the piston, this study conducted experimental tests. Three experimental groups were set up: a high flow group (piston flow of 2.14 × 10− 5m³/s), a medium flow group (piston flow of 1.02 × 10− 5m³/s), and a low flow group (piston flow of 6.78 × 10− 6m³/s).The main parameters of the pistons in the three groups are shown in Table 3.

Experimental steps: (1) Measure and record the flow rates of three sets of pistons (Fig. 14(a) shows the Flow Testing Platform of the Gas-lubricated piston). (2) Install the pistons sequentially on the same Stirling cryocooler. (3) Conduct cooling experiments and performance tests (Fig. 14(b) shows the Experimental Platform of Stirling Cryocooler). Figure 14(c) shows the physical picture of some parts. The experimental setup mainly includes: (1) gas-lubricated piston samples and flow meter ; (2) a Stirling cryocooler;3) Drive power supply and desktop multimeter. The driving power supply used in this paper is the ELA-5020 programmable AC and DC power supply of Taiwan Huayi EEC, which can realize the real-time measurement of the voltage, current, input power, apparent power, operating frequency, power factor, etc. of the cryocooler, and its voltage regulation accuracy is ± 0.1 V, and the frequency adjustment accuracy is ± 0.1 Hz. The PT-100 platinum resistance temperature sensor is used to measure the cold junction temperature with a measurement accuracy of ± 0.1℃. The resistance value of the platinum resistance is demonstrated by the GDM-9061 model 6-and-a-half-digit digital multimeter of Guwei, and the measurement accuracy is 100µΩ in the 100Ω range, and the cold junction temperature can be obtained by converting the resistance value of the platinum resistance. The charging pressure of the experimental Stirling cryocooler is 3.2 MPa, and the working fluid is helium.

Cooling rate

The stationary cryocooler operates at a frequency of 60 Hz and an input power of 200 W to perform a cooling test at no load on the cryocooler. The results are shown in Fig. 15. Starting work under the same environmental conditions (17℃/40%), the cooling characteristic curves of the three experimental groups are similar. The temperature of the cold head can rapidly drop below − 100℃ within 10 min after startup, and then the cooling rate slows down until it reaches a stable state. The experimental group with a flow rate of 6.78 × 10⁻⁶m³/s can reach − 150 °C within 12 min after startup, and cryocooler reaches the final temperature in 20 min. The experimental group with a flow rate of 2.14 × 10⁻⁵ m³/s reaches − 150 °C 20 min after startup and only reaches the final temperature in 30 min, with a cooling rate 40% lower than the former. Furthermore, the experimental group with a piston flow rate of 6.78 × 10⁻⁶m³/s can reach an end temperature of -175.5 °C, showing a 3 °C temperature difference at the cold end compared to the experimental group with a flow rate of 2.14 × 10⁻⁵m³/s (-172.5 °C). The results indicate that using a small flow range for the piston in the three groups of experiments allows the cryocooler to reach the target temperature more quickly and achieve a lower final temperature.

The power factor of the cryocooler is a parameter that measures the ratio of the active power (actual work) to the apparent power (the product of voltage and current) in the AC circuit, which reflects the electrical energy utilization efficiency of the cryocooler. the cryocooler needs to overcome the mechanical resistance to do work at the moment of start-up, and the power factor is high; Then the cryocooler continues to run, the mechanical resistance decreases, the active power decreases, and the power factor decreases until it stabilizes. Its essence is a dynamic adjustment process in which the system operates in a steady state at no load. As shown in Fig. 16, the experimental group with a piston flow rate of 6.78 × 10− 6m³/s has higher electrical energy utilization efficiency, and the cryocooler operates more stably.

Cooling performance

To investigate whether the gas-lubricated piston flow affects the overall cooling performance of the equipment, a frequency sweep experiment was conducted first. Its purpose is to obtain the cold head temperature of the cryocooler at different frequencies by changing the excitation frequency, in order to find the operating frequency that maximizes cooling capacity and achieves the optimal coefficient of performance, at which point the temperature of the cryocooler cold head corresponds to the lowest point on the curve. The experimental results are shown in Fig. 17. The minimum temperature of the cryocooler’s cold head roughly shows a ‘V-shaped’ curve as the frequency increases. The optimal operating frequency of the experimental cryocooler with a piston flow rate of 6.78 × 10⁻⁶m³/s is 65 Hz, at which it can reach a minimum temperature of -180.6℃. The optimal operating frequency of the experimental group with a piston flow rate of 2.14 × 10⁻⁵m³/s is 69 Hz. Observing the curves in the figure, it is found that the optimal operating frequency of the cryocooler is less closely related to the flow rate of the gas-lubricated piston, which provides optimization flexibility for the flow control strategy.

Next, the cryocooler’s performance was tested using the thermal equilibrium method, comparing the results at the same operating frequency (Fig. 18) and at each unit’s optimal operating frequency (Fig. 19). The thermal equilibrium method involves heating the cooling head of the cryocooler with a heating piece (corresponding to test point B in Fig. 14(b)). Once the temperature of the cooling head (corresponding to test point A in Fig. 14(b)) stabilizes, this amount of heat represents the cooling capacity. Both Figs. 16 and 17 show that the experimental group with a piston flow rate of 6.78 × 10⁻⁶m³/s has better cooling performance than the other two groups, with a COP of 0.1 at 20 W@-152.6℃ and a COP of 0.43 at 86 W@-88.0℃. At the same operating frequency (Fig. 18), in the low temperature region, the difference in cooling performance between the experimental group with 1.02 × 10⁻⁵m³/s and the experimental group with 2.14 × 10⁻⁵m³/s is relatively small. However, as the temperature rises, this difference becomes more apparent, manifested by the fact that the cold head temperature in the high-flow experimental group rises faster under the same amount of heating. It indicates that the closer the temperature of the cryocooler’s cold head is to the ambient temperature range, the further the operating condition of a high-flow piston cryocooler deviates from its designed working state, leading to faster performance degradation20. In summary, it is believed that optimizing the cryocooler’s efficiency in the cryogenic region by controlling the flow of the piston is a feasible approach.

Conclusion

The use of gas bearing technology on the piston allows for non-contact operation, which reduces contamination and significantly increases service life. Compared with the traditional small-hole throttling type, the gas-flotation piston of the porous medium throttling type is simpler and less costly. Therefore, in this paper, the local porous media type piston assembly is taken as the research object, and the gas film expansion model is simulated, and the influence of porous media structure parameters, gas supply pressure and gas film gap on piston flow and gas film bearing capacity is studied. In order to explore the influence of the static performance (volume flow) of the piston on the performance of the cryocooler, a test platform for the gas-floating piston Stirling cryocooler was built. Now the conclusion is summarized as follows:

-

1.

The gas supply pressure is linearly positively correlated with the piston flow rate and the bearing capacity of the gas film. Therefore, to a certain extent, increasing the gas supply pressure is an effective way to improve the bearing capacity.

-

2.

The thickness of the gas film has a nonlinear regulation effect on the bearing capacity and piston flow. Reducing the thickness of the gas film can increase the bearing capacity and reduce the gas consumption, and the increase of the gas supply pressure has a blessing effect on this phenomenon. Based on the comprehensive consideration of theory and practical needs, it is recommended that the gap between the piston and the cylinder should be controlled between 12 μm and 20 μm.

-

3.

3.Increasing \(\:{D}_{p}\) and the porosity of the porous medium, as well as decreasing \(\:{L}_{p}\), can enhance the bearing capacity and volumetric flow rate of the gas film. Using a porous medium structure with a larger aspect ratio helps reduce flow resistance losses, resulting in better overall performance of the piston.

-

4.

This paper selects pistons with three flow rates—high flow group (2.14 × 10⁻⁵m³/s), medium flow group (1.02 × 10⁻⁵m³/s), and low flow group (6.78 × 10⁻⁶m³/s)—as the control groups for Stirling cryocooler experiment. The experimental results show that the cryocooler equipped with a low-flow piston cools down faster and reaches a lower refrigeration temperature (a difference of 3 °C compared to the large-flow experimental group). The experimental group with a piston flow rate of 6.78 × 10⁻⁶m³/s has better cooling performance than the other two groups, with a COP of 0.1 at 20 W@-152.6℃ and a COP of 0.43 at 86 W@-88.0℃. Therefore, it is considered feasible to optimize the efficiency of Stirling cryocooler by regulating the piston flow.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- A :

-

Area [m2]

- \({C}_{2}\) :

-

Inertial drag coefficient [m− 1]

- D :

-

Diameter [mm]

- \({d}_{p}\) :

-

Average particle diameter [μm]

- \(F\) :

-

Bearing capacity [N]

- h :

-

Thickness of the gas film [μm]

- L :

-

Length [mm]

- \(P\) :

-

Pressure [Pa]

- \({Q}_{v}\) :

-

Volumetric flow rate [m3/s]

- \(U\) :

-

Velocity of the piston [m/s]

- \({u}_{z}\) :

-

Velocity of fluid [m/s]

- α :

-

Viscous resistance coefficient [m− 2]

- \(\varepsilon\) :

-

Porosity of porous media

- \(\mu\) :

-

Hydrodynamic viscosity coefficient [Pa·s]

- \(\rho\) :

-

Density of the fluid [kg/m3]

- \(\varphi\) :

-

Viscous permeability [m2]

- in :

-

Inlet

- out :

-

Outlet

- \(p\) :

-

porous medium

- x :

-

X-direction

- y:

-

Y-direction

- z :

-

Z-direction

References

Wu & Yinong Stirling Refrigeration Technology for Aerospace 12–01 (Shanghai, Shanghai Institute of Technical Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences,, 2023).

Kuo, D. T., Loc, A. S. & Hanes, M. Gas Bearing lmplementation of Small Cryocooler Compressor[C].Advances in Cryogenic Engineering.Keystone,Colorado:2005:687–695.

LI Haining. Numerical Study on Gas Bearing and Gap Sealing Characteristics of Linear compressor[D] (Huazhong University of Science and Technology, 2013).

Jiho, P. et al. Free-Piston Stirling cryocooler (FPSC) for Low-Temperature applications down to 110 K[J]. Int. J. Refrig. 2020, 117(prepublish):218–229 .

Lane, N. W. Commercialization status of free-piston Stirling machines[C]//12th International stirling engine conference, Durham, UK. : 95–114. (2005).

Weifeng, D. et al. Development of the double two-phase thermosyphon loops used in low temperature Stirling cryocooler[J].International Journal of Refrigeration,2023,155173-183.

Shanghai Chaolian Technology Co. Ltd. A push-piston assembly for Stirling cryocooler:202510127828.1[P].2025-04-15.

Wang Jianzhong, C. & Xi, Z. Hua. Discussion on hydrostatic gas bearings in free-piston Stirling cryocooler[J].Fluid Machinery,2011,39(11):62–66 49.

Unger, R. Z. M. Gas bearing and method of making a gas bearing for a free piston machine. U S Patent 6,293,184[P]. 2001-9-25.

Qi Yun, S. et al. Design and experimental study of 10 W@77 K free piston Stirling cryocooler[J].Cryogenic Engineering,2021,(04):35–3964 .

Zhang Yin, W. et al. Research and development on an aerospace gas-bearing Stirling cryocooler[J],Cryogenic Engineering,2023,(02):50–60 .DOI:CNKI:SUN:DWGC.0.2023-02-007.

Zhang Xiaoqing, W. Weiwei. Performance analysis of linear compressor gas bearing[J].Journal of Huazhong university of science and Technology(Natural science Edition),2012,40(01):108–112 .https://doi.org/10.13245/j.hust.2012.01.017

Wang Qingfeng, Q. et al. Numerical simulation of gas bearings for linear Compressors[J].Refrigeration Technology,2019,39(02):29–33 .

Changpei, Z. et al. Analysis of hydrostatic gas bearing Performa-nce based on COMSOL&MATLAB Platform[J].Vacuum & low Temperature,2018,24(06):405–409 .DOI:CNKI:SUN:ZKDW.0.2018-06-013.

Awise, M. U. H. A. M. M. A. D. P. U. N. H. A. L. et al. Influence of airflow parameters on static characteristics and performance of porous aerostatic bearings[J].Journal of Ningbo University(Science and technology Edition),2023,36(05):1–10 .https://doi.org/10.20098/j.cnki.1001-5132.2023.0505

Yan, R. Z., Wang, L. Y. & Wang, S. Z. Performance comparison between aerostatic bearings with orifice and porous restrictors based on parameter optimization[J]. Australian J. Mech. Eng. 19 (4), 378–389 (2021).

Li, W-L. et al. CFD analysis on the intensified mechanism of gas-liquid mass transfer in a microporous tube-in-tube microchannel reactor[J]. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 182, 121914 (2022).

Zhu, X. et al. Simulation of air flotation frictionless cylinder and air flotation characteristics[J].Journal of Zhejiang University(Engineering and technology Edition),2014,48(02):214–220 .DOI:CNKI:SUN:ZDZC.0.2014-02-005.

Yu, P. et al. Theoretical predictions and experimental measurements of novel aerostatic bearing with multi-inclined-orifice restrictors for the improvement of stability[J].Precision Engineering,2024,88266-278.

Wang, B. et al. 15 W@77K Research and development of gas bearing Stirling cryocooler[J].Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology(Natural Science Edition),2018,46(05):106–109 .https://doi.org/10.13245/j.hust.180519

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Shanghai Science and Technology Plan Project (230H1103200) and Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai, China (No. 24ZR1428800).

Funding

This work was supported by Shanghai Science and Technology Plan Project (230H1103200) and Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai, China (No. 24ZR1428800).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ankuo Zhang: Propose research topics and design research plans. Dandan Lei: Designing Thesis Frameworks; Implementing the research process; drafting papers; Revised paper. Xiaoli Gong: Research and organize literature and participate in the experimental research process. Wenhui Yu: Guided help. Chao Xiong & Haitao Chen: Provide an experimental platform and thesis guidance.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lei, D., Zhang, A., Gong, X. et al. Effect of gas flow rate on the gas-lubricated piston in a stirling cryocooler. Sci Rep 16, 1382 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31249-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31249-x