Abstract

Melon (Cucumis melo L.) is an essential dietary component in Iran and Iraq, making the understanding of its genetic diversity crucial for breeding and conservation efforts. However, limited studies have investigated the genetic diversity of melon populations in these regions. This study evaluated the genetic diversity and population structure of 80 melon genotypes collected from 20 regions across Iran and Iraq using Inter-Simple Sequence Repeat (ISSR) and Start Codon Targeted (SCoT) markers. A total of 11 ISSR and 14 SCoT primers generated 166 and 245 fragments, respectively. The mean percentage of polymorphism was higher for ISSR (77.67%) than SCoT (68.47%). However, SCoT markers exhibited a higher polymorphic information content (0.438) compared to ISSR markers (0.374), indicating superior discriminatory power. The resolving power of the primers was comparable between the two marker systems. Cluster analysis using the Jaccard similarity coefficient and UPGMA algorithm grouped the genotypes into two and four clusters based on ISSR and SCoT markers, respectively, a pattern further supported by principal component analysis. Analysis of molecular variance revealed greater intra-population variation than inter-population variation for both markers. A combined marker analysis classified the genotypes into three major groups. Overall, our findings indicate that SCoT markers are more effective than ISSR markers for assessing genetic diversity and population structure in melon genotypes. This study provides valuable insights for melon breeding and conservation programs in Iran and Iraq.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Genetic diversity is a cornerstone of biodiversity and a critical resource for the long-term survival of species in changing environments1. Understanding the genetic structure of populations provides insights into historical migration events, gene flow dynamics, and adaptive potential, while also enabling the identification of risks associated with genetic erosion2,3. Genetic erosion, defined as the reduction of genetic diversity in plant populations, is typically caused by habitat destruction, intensive agriculture with repeated use of commercial varieties, climate change, and other human pressures. This loss of diversity diminishes populations’ ability to adapt to environmental stresses and increases their vulnerability to diseases, ultimately threatening their long-term survival. In regions such as Iran and Iraq, which are significant centers of genetic diversity for certain species, genetic erosion has also been observed4. Therefore, a comprehensive assessment of genetic diversity and structure is essential for developing conservation strategies and breeding programs aimed at preserving valuable genetic resources.

High genetic diversity in plant populations enables breeders to develop improved cultivars with desirable traits such as stress tolerance and enhanced yield5,6,7,8. However, this diversity is not uniformly distributed; it is influenced by geographic isolation, breeding systems, and anthropogenic factors5. Thus, assessing genetic diversity in fragmented or isolated populations is crucial for conservation strategies, including targeted breeding programs and the introduction of genetically diverse germplasm.

In recent decades, DNA-based molecular markers have become essential for assessing genetic diversity, phylogenetics, breeding, and genome analysis in plants. Among these, ISSR (Inter-Simple Sequence Repeat) and SCoT (Start Codon Targeted) markers are widely used due to their specific advantages.

ISSR markers amplify genomic regions between microsatellite repeats using primers anchored to di- or trinucleotide motifs. They require no prior sequence data and detect high polymorphism with reproducible, stable banding patterns9,10. ISSRs are effective for biodiversity assessment, genetic mapping, and evolutionary studies11,12,13. They are technically simple, cost-effective, and more reliable than RAPD or costly AFLP markers, with high resolving power.

SCoT markers, a newer PCR-based method, target conserved regions flanking the ATG start codon of protein-coding genes14. Using single 18-mer primers, they offer higher reproducibility and stability than random markers like RAPD15,16. SCoT markers excel in identifying trait-linked genes, genetic mapping, population studies, and marker-assisted selection17. They also do not require complete genome sequences, making them useful in non-model species.

ISSR and SCoT markers were selected due to their complementary characteristics. ISSR markers do not require prior sequence information and provide high polymorphism and reproducibility, mainly targeting non-coding regions of the genome with random amplification, making them suitable for diversity assessment. In contrast, SCoT markers target gene-rich regions and, as a semi-targeted marker with higher discriminative power and greater functional relevance, provide more biologically meaningful information18. Combining these two markers offers a comprehensive view of genetic diversity and population structure.

Many studies have utilized ISSR and SCoT markers together to enhance genomic coverage and improve the accuracy of polymorphism detection. For instance, Xanthopoulou et al.19, studied Greek Genebank collection of summer squash (Cucurbita pepo) landraces, sponge gourd (Luffa cylindrica)25, Tyagi et al.20 detected genetic diversity and population structure in sponge gourd (Luffa cylindrica); Kumar, J., & Agrawal21 studied genetic diversity, population structure and sex identification in dioecious crop, Trichosanthes dioica; Gogoi et al.22 analyzed Clerodendrum species in Northeast India; Abouseada et al.23 assessed wheat cultivars; Jahangir and Nasernakhaei24 characterized Cressa cretica; Nasri et al.25 evaluated genetic fidelity of in vitro raised Chrysanthemum plantlets; Elgohary et al.26 authenticated Asteraceae species; Baghizadeh and Dehghan27 analyzed pistachio cultivars; and Keshavarzi et al.28 investigated rigid ryegrass. These examples illustrate the wide applicability of combined ISSR and SCoT markers in various plant genetic studies.

Cucumis melo L. (melon), a diploid species (2n = 24) within the Cucurbitaceae family, displays remarkable morphological diversity in fruit size, shape, flavor, and stress adaptability29,30. Originating in Central Asia, melon landraces have diversified across Mediterranean and Far Eastern regions, developing unique adaptations to local environmental conditions31. These landraces serve as a vital genetic reservoir for breeding programs aimed at addressing challenges like climate change and pest resistance. Despite the global agricultural importance of melon, the genetic diversity of its populations in Iran and Iraq—regions considered part of the species’ center of origin—has not been adequately studied. Most previous research has focused primarily on Mediterranean or commercial varieties, leaving a significant gap in understanding the genetic structure of native populations in West Asia31,32.

Numerous studies have been conducted in Iran and Iraq using various molecular and morphological markers, primarily covering the central and eastern regions of Iran (such as Khorasan, Semnan, Tehran, Isfahan, and Fars provinces)33,34,35,36,37,38 and parts of Iraq (including Baghdad, Basrah, Mosul, and Diyala)34,39,40. However, only limited research has been performed in the Kurdistan region of Iraq using URP, IRAP, SRAP, and CDDP markers41, and in Iran, only one study based on morphological traits has been conducted in this region38. Therefore, the present study represents the first genetic diversity assessment of native melon populations in the Kurdistan region of Iran and Iraq using ISSR and SCoT markers, providing valuable information for germplasm conservation and future breeding programs.

This study aims to comprehensively assess the genetic diversity and population structure of 80 native melon genotypes from western Iran and eastern Iraq using ISSR and SCoT molecular markers. Specifically, the research seeks to (1) compare the efficiency and discriminatory power of ISSR and SCoT markers in detecting polymorphisms, (2) analyze the distribution and patterns of genetic diversity within and among populations, and (3) evaluate the correlation between genetic structure and geographic origin. The central hypothesis posits that the combined application of these two marker systems will offer a more comprehensive and accurate depiction of genetic diversity, revealing significant genetic variation influenced by geographic and environmental factors. Findings from this study are expected to provide valuable insights into the genetic resources of melon at its center of origin and inform effective conservation strategies and breeding programs aimed at crop improvement.

Methods and materials

Plant materials

A total of 80 melon (Cucumis melo L.) genotypes were analyzed in this study. Seeds were collected from 20 geographically distinct regions, including 7 regions in western Iran (Kurdistan and West Azerbaijan provinces) and 13 regions in eastern Iraq (primarily within the Kurdistan Region of Iraq) (Fig. 1). Four individual plants were sampled from each region to capture intra-regional genetic diversity, resulting in 80 genotypes (20 regions × 4 genotypes per region). Sampling was conducted during the 2022 growing season, with seeds collected from healthy, mature fruits of landrace accessions grown under local farming practices. To minimize sampling bias, plants were selected at random within each region, spaced at least 500 m apart to reduce clonal or familial redundancy.

Geographic locations and collection sites of Cucumis melo L. accessions from Iran and Iraq. CM1: Cm.Ban A, CM2: Cm.Ban B, CM3: Cm.Mah, CM4: Cm.Bok, CM5: Cm.Mar, CM6: Cm.Meh, CM7: Cm.Saq, CM8: Cm.Ko, CM9: Cm.Sul, CM10: Cm.Haw, CM11: Cm.Har, CM12: Cm.Kar, CM13: Cm.Pen, CM14: Cm.She, CM15: Cm.Kif, CM16: Cm.Qal, CM17: Cm.Zak, CM18: Cm.Duh, CM19: Cm.Hal, CM20: Cm.Akr.

Geographical coordinates (latitude, longitude, altitude) of collection sites, along with population codes and administrative details, are provided in Table 1. All collected materials were authenticated as Cucumis melo based on morphological descriptors (e.g., fruit shape, rind texture, and seed morphology) outlined by Kirkbride29.

The melon seeds were cultivated in the agricultural research greenhouses of the Kurdistan University. Seeds of each genotype were sown in 1-L pots containing a mixture of soil, sand, and manure in a ratio of 1:1:1. After seed germination, samples were taken from young leaves of each genotype at the 2–3 leaf stage and stored in a -50 °C freezer until DNA extraction.

Molecular experiments

DNA extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted using a modified CTAB protocol42, which incorporated 1% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) into the extraction buffer to eliminate polyphenolic compounds commonly found in melon leaves, along with sthe addition of saturated phenol to the washing buffer thereby improving DNA quality and yield. Fresh leaf tissue (0.2 g) was ground in liquid nitrogen until fully powdered. The powdered tissue was transferred to a 2 mL microtube, followed by the addition of 1 mL extraction buffer (comprising 2% CTAB, 100 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 20 mM EDTA, 1.4 M NaCl, and 1% PVP) and 10 μL β-mercaptoethanol. After vortexing, the samples were incubated in a water bath at 65 °C for 1 h, with gentle inversion every 15 min.

Subsequently, 1 mL of phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) was added, and the mixture was gently inverted for 15–20 min, followed by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 15 min to achieve phase separation. The aqueous phase was carefully transferred to a new 1.5 mL microtube, and DNA was precipitated by adding 60 μL of 3 M sodium acetate and 600 μL of cold isopropanol. Samples were incubated at − 20 °C for 24 h.

Following precipitation, the DNA was pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 5 min at 15 °C. The supernatant was discarded, leaving only the white DNA precipitate. The pellet was washed with 1 mL of 70% ethanol, incubated at room temperature for 15 min, and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 8 min. The ethanol was completely removed, and the DNA pellet was air-dried at 37 °C. Finally, the DNA was resuspended in 40 μL of TE buffer and stored at -20 °C. The quality and quantity of the extracted DNA were assessed using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer and 1% agarose gel electrophoresis.

PCR reactions and marker analyses

To optimize PCR amplification, two DNA samples from each population were selected for preliminary primer evaluation to identify those yielding clear band profiles while excluding primers that produced low-quality or weak bands. Out of the 19 SCoT and 15 ISSR primers tested, 14 SCoT primers and 11 ISSR primers generated distinct and consistent bands and were subsequently used for the final amplifications (Table 2). Polymerase chain reaction was performed using a thermocycler (Bio-Rad T100, USA) in a volume of 10 µl. Each reaction contained the following materials: 1 µL PCR buffer (10x), 0.5 µL MgCl2 (50 mM), 0.2 µL dNTPs (10 mM), 1 µL primer (10 pmol/ µL), 0.11 µL DNA Taq polymerase enzyme (10 u/ µL), 20 ng genomic DNA per reaction (1 µL of 20 ng/ µL stock) and 6.19 µL double-distilled water. The PCR thermal cycle was as follows: 1 cycle of initial denaturation at 94 °C for 4 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 45 s annealing at the primer-specific temperatures (Tm) as listed in Table 2 for 1 min, extension at 72 °C for 1.5 min, and 1 cycle of final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. A 1.7% agarose gel electrophoresis was used to determine the quality and analyze of PCR products.

Table 2 shows the sequences of SCoT and ISSR primers synthesized by CinnaGen Company, Tehran, Iran. The selection of primers was based on previous studies, focusing on those primers with the highest gene location and the highest number of polymorphic bands43,44,45.

Band scoring and data analysis

After PCR, bands appearing on the agarose gel were scored. Since the markers used were dominant, amplified bands were scored for the presence of a band (1) and the absence of a band (0). Scoring was done manually and only for clearly visible bands. For each marker, the total number of bands produced (TB), polymorphic bands (PB), the monomorphic bands (MB), and the percentage of polymorphism bands (PPB%) were determined using Excel 2016. Additionally, the polymorphic information content (PIC) (Roldan-Ruiz et al., 2000) was calculated online using the Gene Calc tool (https://gene-calc.pl/pic) based on the equation PIC = 2ƒi(1- ƒi).

The effective multiplex ratio (EMR) was calculated using the equation the EMR = NP × ß, where ß = NP/N, NP is the number of polymorphic bands, and N refers to the number of amplified bands. The marker index (MI), which represents the degree of polymorphism and serves as an indicator a marker efficiency in assessing unknown germplasms, was calculated using the formula MI = PIC × EMR. The resolving power (RP) of primers was calculated using the RP = ∑Ib formula. The value of Ib, which ranges from 0 to 1, is calculated as follows: Ib = 1-[2 × (0.5-p)].

Genetic diversity within and between populations was assessed using analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) for ISSR and SCoT markers using GenAlEx 6.5 software46. For cluster analysis, dendrograms were constructed using the Jaccard similarity coefficient and the UPGMA method, utilizing PAST software47. Additionally, principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was performed to identify relationships between populations and species, also using PAST software.

Population structure was inferred using a Bayesian clustering approach implemented in STRUCTURE v2.3.448,49. This method probabilistically assigns individuals to subpopulations (K) while estimating allele frequencies and admixture proportions. The analysis involved 10 independent runs for each K value (ranging from 1 to 10), with a burn-in period of 50,000 iterations followed by 500,000 Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) iterations under the admixture model with independent allele frequencies. Convergence of the MCMC chains was assessed by examining the stability of log-likelihood values across iterations and ensuring that multiple independent runs yielded consistent results. The optimal K value was determined using both the log probability of the data [LnP(D)] and the ΔK statistic50, calculated via the Structure Harvester web platform51.

Results

SCoT and ISSR banding profiles

Genetic diversity among 80 melon genotypes from 20 populations in western Iran and the Kurdistan Region of Iraq was assessed using 14 SCoT and 11 ISSR primers. Figure 2 shows representative banding profiles of SCoT17 and UBC812 primers. SCoT markers demonstrated superior amplification performance, generating 245 total fragments with 77.67% polymorphism. Band production varied considerably among primers, with SCoT4, SCoT14, and SCoT23 producing the highest number of total bands (22 each), while SCoT3 produced the fewest (13). For polymorphic bands, SCoT23 generated the highest number (22), followed by SCoT4 (19). Complete polymorphism (100%) was achieved by three primers (SCoT3, SCoT5, and SCoT23), whereas SCoT21 showed notably lower polymorphism at 40% (Table 3). ISSR primers generated 166 fragments with 68.67% polymorphism. Performance variation was evident, with UBC-876 producing the most bands and UBC-825 the fewest. Two primers (UBC-825 and UBC-853) achieved complete polymorphism, while UBC-812 and UBC-835 showed the lowest polymorphism rates at 50% (Table 4). The high overall polymorphism rates observed with both marker systems underscore substantial genetic diversity within the studied germplasm.

Genetic indices

Polymorphic information content (PIC) values served as a key measure of marker informativeness and discriminatory power. SCoT markers showed PIC values ranging from 0.198 to 0.498, with an average of 0.435, indicating high genetic informativeness across most primers. The lowest PIC value was observed for primer SCoT21 (0.198), reflecting its limited ability to detect polymorphisms, while primers SCoT11 and SCoT23 exhibited the highest PIC values (0.498), demonstrating maximum discriminatory power. ISSR markers displayed a similar pattern but with generally lower values, averaging 0.356 and ranging from 0.215 (UBC-841) to 0.484 (UBC-876). These PIC values indicate that both marker systems are highly informative, with SCoT markers showing slightly superior performance in genetic discrimination (Tables 3 and 4).

The effective multiplex ratio (EMR) and marker index (MI) provided additional insights into marker efficiency and overall informativeness. SCoT markers showed considerable variation in EMR, ranging from 2.4 (SCoT21) to 22 (SCoT23), with primer SCoT4 displaying the highest MI value (7.72) and SCoT21 the lowest (0.48). The average MI for SCoT markers was 4.57, reflecting their overall efficiency in detecting genetic variation. ISSR markers demonstrated more consistent performance, with EMR values averaging 7.38 and ranging from 2.88 (UBC-842) to 16 (UBC-853). The average MI for ISSR markers was notably higher at 2.71, with UBC-873 showing the highest MI value (6.39) and UBC-842 the lowest (0.85).

Resolving power (Rp) analysis revealed complementary strengths between the two studied marker systems. For SCoT markers, the mean Rp was 22.15 for, SCoT14 exhibiting the highest value (31.77) and SCoT3 the lowest (3.067). In contrast, ISSR markers showed a higher mean Rp 23.08, ranging from 12.77 (UBC-825) to 34.05 (UBC-876). This higher resolving power suggests that ISSR markers may be particularly effective for fine-scale genetic differentiation and phylogenetic analyses (Tables 3 and 4).

SCoT markers proved more effective overall for genetic diversity assessment, generating more total bands (245 vs. 166) with higher polymorphism rates (77.67% vs. 68.47%) and superior discriminatory power (average PIC = 0.435 vs. 0.356). The average number of polymorphic bands per primer was also higher for SCoT markers (13.5) compared to ISSR markers (10.36). Nevertheless, ISSR markers compensated with superior resolving power and higher MI values, indicating their utility for specific applications requiring enhanced resolution. These complementary characteristics highlight the value of combining both marker systems in comprehensive genetic diversity studies, with SCoT markers being particularly valuable for breeding programs and germplasm characterization due to their higher informativeness and polymorphism detection capacity.

Molecular variance

Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) revealed distinct patterns of genetic variation within and among melon populations using ISSR and SCoT markers (Table 5). For the ISSR marker, inter-population variation accounted for 40% of total genetic variance (SS = 514.738, Est. Var. = 4.928), while intra-population variation contributed 60% (SS = 442.750, Est. Var. = 7.379). The corresponding fixation index (PhiST = 0.40), equivalent to Fst for dominant markers, indicates high population differentiation according to Wright’s classification. Similarly, the SCoT marker showed that inter-population variation represented 38% of total variance (SS = 1091.800, Est. Var. = 10.265), with intra-population variation dominating at 62% (SS = 984.250, Est. Var. = 16.404). The corresponding FST value of 0.385 also reflects substantial genetic differentiation among populations. When data from both markers were pooled, inter-population variation decreased slightly to 39% (SS = 1606.538, Est. Var. = 15.193), while intra-population variation remained predominant at 61% (SS = 1427.000, Est. Var. = 23.783).

The combined Fst value of 0.39 confirms high genetic differentiation among melon populations, indicating limited gene flow and significant population structure. These Fst values (0.38–0.40) fall within the range considered indicative of very high genetic differentiation (Fst > 0.25), suggesting that geographic isolation and/or local adaptation have contributed to substantial population divergence in the studied melon germplasm.

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA)

The Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) revealed patterns of genetic relationships among melon accessions using different marker systems. However, though the first two axes captured relatively low proportions of total variance (20.65–25.50%), which is typical in high-dimensional genetic datasets and may limit the resolution of finer-scale structure (Fig. 3). In the SCoT-based analysis (Fig. 3A), the first two principal coordinates explained 22.104% of the total variation (PC1 = 14.289%, PC2 = 7.815%).

The plot suggested separation of the accessions into four main groups: Group 1 comprised populations from Sulaymaniyah, Akre, Dehglan, and part of Dohuk; Group 2 included populations from Harir, Saghez, Bukan, Baneh1, Hewlêr, and Koye; Group 3 contained populations from Penjwin, Bukan, Kerkük, Shekhan, and Marivan; while Group 4 consisted of Qaladze, Kifrî, Baneh2, Zakho, Mahabad, and Dohuk populations.

The ISSR marker analysis (Fig. 3B) accounted for 25.50% of the total variation in the first two coordinates (PC1 = 15.591%, PC2 = 9.909%). This analysis revealed two major clusters with suggested population structuring, demonstrating a different pattern of genetic relationships compared to the SCoT markers.

The combined SCoT + ISSR analysis (Fig. 3C) explained 20.65% of total variation (PC1 = 13.338%, PC2 = 7.3125%) and revealed three suggested groups. The first group comprised populations from Qaladze, Kifrî, Zakho, Baneh2, Mahabad, Akre, Dehglan, Dohuk, and Sulaymaniyah; the second group included Baneh1, Saghez, Koye, Helebce, Harir, and Hewlêr; and the third group contained populations from Shekhan, Kerkük, Penjwin, Bukan, and Marivan. This combined analysis provided a more comprehensive view of population structure, suggesting that the integration of both marker systems offered complementary information for understanding genetic relationships among the studied melon populations, consistent with patterns observed in cluster analysis despite the limited variance explained by the primary axes.

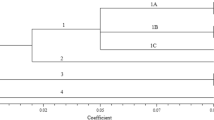

Cluster analysis

The hierarchical cluster analysis suggested distinct patterns of genetic relationships, with varying levels of genetic distance among melon populations. The SCoT-based dendrogram (Fig. 4A) demonstrated higher resolution, separating populations into five well-defined clusters with genetic distances ranging from approximately 0.525–0.975. The first and largest cluster showed the closest genetic relationships (distance ≈ 0.525–0.650) among populations from geographically proximate regions, including Helebce, Baneh1, Koye, Saghez, Harir, and Hewlêr, suggesting possible gene flow between these populations. This cluster also included populations from more distant locations (Kifrî, Qaladze, Zakho, Mahabad, Baneh2, Dohuk, Akre, Dehglan, and Sulaymaniyah), indicating potential historical connections or similar selection pressures.

The ISSR-based dendrogram (Fig. 4B) revealed five clusters with genetic distances ranging from 0.75 to 6.0, indicating broader genetic differentiation compared to SCoT markers. The clustering pattern partially aligned with geographical distribution, particularly evident in the first cluster, where populations from northern regions (Helebce, Baneh1, Koye, Saghez) grouped together. The second cluster predominantly included populations from central and eastern regions (Kifrî, Qaladze, Zakho, Dohuk).

The superior performance of SCoT markers in clustering analyses can be attributed to several factors: more consistent clustering patterns aligned with geographical distribution, better resolution of genetic relationships at both close and distant genetic distances, more stable clustering patterns with fewer singleton groups, and a higher correlation with known ecological and geographical boundaries. The clustering results revealed three main centers of genetic diversity: the northern region, dominated by closely related populations (e.g., Helebce, Baneh1, Koye); the central region, characterized by intermediate genetic distances and a mixed population structure; and the eastern region, which exhibited higher genetic differentiation and unique genetic profiles. This pattern of genetic structuring likely reflects a combination of historical population movements and current ecological adaptations, with SCoT markers proving particularly effective in capturing these relationships.

Population structure

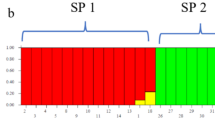

Model-based clustering analysis, based on the Bayesian statistical indices, seeks to elucidate the populations distance structure. It was assumed that the ancestry model is of admixture type and the allele frequency model is continuous, with k ranging from 1 to 10 (where k indicates the number of populations). The STRUCTURE analysis identified the optimal number of genetic clusters as K = 5 for SCoT, K = 3 for ISSR, and K = 6 for the combined dataset. These clusters did not show complete isolation according to the provinces or locations from which the genotypes were collected. The observing mixing in the germplasm suggest that the studied genotypes are of admixture type. Additionally, allelic frequencies may be similar across different populations due to migration or common ancestry. The results of grouping the studied genotypes into genetically distinct subgroups using STRUCTURE software are presented in Fig. 5. The ΔK values, calculated using the Evanno method50, exhibited distinct peaks indicating the optimal number of subpopulations (Fig. 5a). Specifically, for SCoT markers, ΔK reached its maximum at K = 5, supporting a division into five subpopulations. For ISSR markers, the highest ΔK occurred at K = 3, indicating three subpopulations. In the combined SCoT + ISSR dataset, the peak ΔK was observed at K = 6, suggesting six subpopulations. The corresponding ancestry proportions and subpopulation assignments for each optimal K are illustrated in the bar plots (Fig. 5b).

(a) Determining the structure of populations based on the K index with the aim of determining the appropriate number of groups based on markers of SCoT, ISSR, SCoT + ISSR. (b) Population structure of 80 genotypes of melon species based on SCoT, ISSR, SCoT + ISSR markers analyzed in Structure software and Bayesian statistical index. The numbers on the horizontal axis indicate the code of the 80 genotypes and the numbers on the vertical axis indicate the membership coefficient of each individual to the subpopulations. Each color indicates a subpopulation.

Discussion

Molecular markers such as ISSR and SCoT are essential for elucidating genetic diversity in crops with complex population structures, such as melon (Cucumis melo L.). In this study, we comprehensively evaluated the utility of these markers in characterizing 80 genotypes from Iran and Iraq, regions that represent a critical yet understudied reservoir of melon diversity. Our findings indicate that SCoT markers demonstrate notable efficiency, exhibiting higher polymorphism (77.67% vs. 68.47%), polymorphic information content (PIC: 0.435 vs. 0.356), and marker index (MI: 4.57 vs. 2.71) compared to ISSR markers. However, further studies with a larger number of primers are needed to confirm the definitive superiority of these markers.

These results align with findings in summer squash (Cucurbita pepo)19, sponge gourd (Luffa cylindrica)20, and pointed gourd (Trichosanthes dioica)21, where SCoT’s gene-targeted primers provided enhanced resolution of genetic relationships. The higher MI and effective multiplex ratio (EMR) of SCoT markers (4.57–11.04 vs. ISSR’s 2.71–7.38) reflect their ability to amplify functional regions near start codons, capturing loci under selection pressure and thus offering greater relevance for breeding programs14,52. Recent reviews on marker systems emphasize SCoT’s reproducibility and functional relevance, particularly in non-model crops, due to its alignment with conserved gene regions involved in stress responses and developmental traits53,54. Conversely, while ISSR markers are cost-effective for preliminary screening, they exhibited slightly higher resolving power (Rp = 23.08 vs. SCoT’s 22.15), likely due to their reliance on hypervariable microsatellite regions, which may suffer from homoplasy or uneven genome coverage55,56.

Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) revealed that intra-population diversity (60–62%) significantly exceeded inter-population variation (38–40%) for both markers. This pattern is consistent with cross-pollinated species, where gene flow and local adaptation drive heterogeneity within populations57. This trend mirrors findings in Diospyros54 and Lasiurus sindicus58, where anthropogenic practices, such as seed mixing and ecological pressures (e.g., drought, soil variability), have amplified within-population diversity. The higher total estimated variance for SCoT (26.669) compared to ISSR’s (12.307) highlights its robustness in capturing subtle genetic subdivisions, likely due to its alignment with conserved gene regions54. A combined marker analysis reduced inter-population variation to 39%, suggesting complementary strengths: ISSR’s broad genome coverage and SCoT’s specificity for functional locus synergize to resolve complex population dynamics59,60. Similar integrative approaches in Cucurbita pepo61 and Citrullus lanatus62 have effectively captured both neutral and adaptive genetic variation, which is critical for breeding climate-resilient varieties.

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) and cluster analysis supporting evidence for the effectiveness of SCoT markers in grouping genotypes. SCoT suggested the grouping of genotypes into four clusters that partially corresponded with geographic origins—northern (e.g., Helebce, Baneh1), central (mixed structure), and eastern (unique profiles)—while ISSR produced overlapping groups. However, though interpretations are tempered by the relatively low variance explained by the primary PCoA axes (20.65–25.50%), with consistency observed across complementary cluster analyses.

These findings align with studies in Dendrocalamus manipureanus63 and Clerodendrum serratum22, where SCoT markers resolved ecogeographic patterns linked to historical migration and localized adaptation. The combined use of marker uses improved resolution, dividing genotypes into three groups, a strategy advocated for complex diversity studies64,65. The UPGMA dendrogram, supported by Jaccard similarity coefficients, corroborated these findings, with SCoT outperforming ISSR in grouping accuracy. Such precision is critical for breeding programs, particularly in cross-pollinated species like melon, where heterosis exploitation relies on selecting parents with maximal genetic distance66,67. In Cucumis sativus, similar clustering patterns using SCoT markers have been linked to fruit quality traits, demonstrating their utility in trait-assisted selection68.

Population structure analysis revealed significant admixture among Iranian and Iraqi genotypes, suggesting historical gene flow or shared ancestry. The delta K method50 identified three optimal subpopulations, while SCoT marker system detected finer subdivisions—a trend observed in Aegilops triuncialis69 and Andrographis paniculata64. The integration of STRUCTURE and UPGMA analyses provided complementary insights into population genetic structure. STRUCTURE bar plots (Fig. 5b) demonstrated extensive admixture, with many individuals showing ancestry from multiple subpopulations (average admixture coefficient > 0.3 across populations), whereas the UPGMA dendrogram (Fig. 4) identified three distinct genetic clusters. This apparent methodological inconsistency requires careful interpretation: UPGMA clustering, based on genetic distance matrices, emphasizes overall genetic similarity and creates discrete hierarchical separations, effectively “forcing” individuals into distinct groups regardless of admixture levels. In contrast, STRUCTURE employs a model-based Bayesian approach that probabilistically assigns individuals to populations while simultaneously estimating admixture proportions, thereby capturing the continuous nature of gene flow and shared ancestry.

To reconcile these contrasting patterns, we propose that the UPGMA dendrogram reflects the underlying population structure (three main genetic lineages), while STRUCTURE reveals the dynamic processes (gene flow and admixture) that have modified this basic structure over time. The extensive admixture detected by STRUCTURE (with many individuals showing less than 70% assignment to any single cluster) indicates that while distinct genetic lineages exist, they are not reproductively isolated. This pattern is particularly evident in genotypes from border regions between Iran and Iraq, which showed intermediate assignments in STRUCTURE but were placed in discrete clusters by UPGMA. Such patterns are common in outcrossing crops like melon, where human-mediated seed exchange may maintain gene flow while geographic or ecological barriers create partial structuring70. This methodological complementarity strengthens our interpretation: the populations exhibit hierarchical genetic structure with significant ongoing gene flow, a pattern consistent with melon’s breeding system and cultivation history in the region.

This admixture likely reflects human-mediated seed exchange or overlapping cultivation zones, as documented in bamboo59 and Juniperus71. Notably, the northern populations (e.g., Kurdistan, West Azerbaijan) exhibited closer genetic ties, possibly due to shared agroclimatic conditions or traditional farming practices that facilitate seed exchange. In contrast, eastern populations demonstrated higher differentiation, potentially due to isolation by mountain ranges or divergent selection pressures31,72.

Reconciling these results suggests that while distinct genetic clusters exist, they are not isolated; rather, they are connected through moderate levels of admixture. This finding which has implications for conservation, highlighting the need to preserve gene flow corridors. A recent study on Neolitsea seicea landraces in Eastern Asia73 similarly identified geographic barriers as key drivers of population divergence, reinforcing the role of landscape features in shaping genetic structure.

While ISSR markers remain valuable for rapid, low-cost screening, SCoT’s stability, reproducibility, and functional relevance make it preferable for detailed germplasm characterization. This study, the first to integrate ISSR and SCoT markers for melon diversity in Iran and Iraq, provides a robust framework for conserving landraces and guiding marker-assisted breeding. Future efforts should prioritize on: 1) Trait-linked studies that associate marker-derived diversity with agronomic traits (e.g., drought tolerance, fruit quality) to identify adaptive alleles, as demonstrated in Cucumis melo by Dilipan and Nisha74, who linked SCoT markers to salinity tolerance; 2) Genomic expansion to develop additional SCoT primers that cover untapped genomic regions and improve linkage mapping, leveraging advances in functional genomics75; and 3) Conservation strategies that target eastern populations with unique genetic profiles for in situ preservation to mitigate genetic erosion, following successful models in Citrullus colocynthis76. By bridging the gap between molecular data and practical breeding, this work advances efforts to enhance melon resilience in the face of climate change and global food security challenges, aligning with global initiatives to conserve crop wild relatives.

Although 11 ISSR and 14 SCoT primers provided sufficient polymorphic and informative loci for robust diversity and population structure analyses, we acknowledge that the total number of primers limits the breadth of genome coverage. These primers were selected after preliminary screening for reproducibility and polymorphism from larger sets of 50 ISSR and 40 SCoT primers, ensuring high informativeness. Nevertheless, increasing the number of primers or integrating additional marker systems (e.g., SNP-based genotyping) could provide finer resolution and more comprehensive coverage of the melon genome in future studies. Moreover, combining the present marker data with morphological evaluations and their associations would enhance the utility of the results for breeding and conservation purposes. Such an integrative approach will yield a more comprehensive understanding of diversity patterns and facilitate the identification of marker–trait associations for targeted breeding and conservation strategies.

Conclusion

Molecular marker studies such as ISSR and SCoT play a pivotal role in identifying intra-specific genetic diversity and enabling precise differentiation among various genotypes. In this study, melon genotypes from Iran and Iraq—regions known as valuable reservoirs of indigenous landraces—were investigated. The obtained results elucidated the genetic structure and level of differentiation among these genotypes, highlighting the presence of unique genetic resources likely shaped by regional cultivation history and restricted gene flow across geographical borders. These findings may serve as a foundation for future research focused on selecting suitable parental lines for hybridization and breeding programs. However, to accurately evaluate the potential of local landraces in traits such as stress tolerance or high yield, phenotypic and field evaluations will be essential in subsequent stages. Moreover, integrating molecular data with farmers’ traditional knowledge can contribute to the conservation of genetic diversity and the advancement of sustainable agriculture under changing climatic conditions.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and/or its supplementary materials.

References

Ebadi, A., Ghaderi, N. & Vafaee, Y. Genetic diversity of Iranian and some European grapes as revealed by nuclear and chloroplast microsatellite and SNP molecular markers. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 94, 599–610 (2019).

Govindaraj, M., Vetriventhan, M. & Srinivasan, M. Importance of genetic diversity assessment in crop plants and its recent advances: An overview of its analytical perspectives. Genet. Res. Int. 2015, 431487 (2015).

Houmanat, K. et al. Molecular diversity of walnut (Juglans regia L) among two major areas in Morocco in contrast with foreign varieties. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 21, 180–192 (2021).

Rao, B. R. Genetic diversity, genetic erosion, conservation of genetic resources, and cultivation of medicinal plants. In: Genetic Diversity and Erosion in Plants: Case Histories Vol. 8 (ed Ahuja MR) 357–392 (Springer, 2015).

Huang, W. et al. Effects of environmental factors on genetic diversity of Caragana microphylla in Horqin Sandy Land, northeast China. Ecol. Evol. 6, 8256–8266 (2016).

Ghanbari Moheb Seraj, R. et al. Metabolomics analysis of milk thistle lipids to identify drought-tolerant genes. Sci. Rep. 12, 12827 (2022).

Hasanpour, K. et al. Identification of drought-tolerant hub genes in Iranian KC-2226 genotype of Aegilops tauschii using transcriptomic analysis. Sci. Rep. 13, 9499 (2023).

Azad, M. et al. Identification of responsive genes to multiple abiotic stresses in rice (Oryza sativa): A meta-analysis of transcriptomics data. Sci. Rep. 14, 5463 (2024).

Pradeep Reddy, M., Sarla, N. & Siddiq, E. A. Inter simple sequence repeat (ISSR) polymorphism and its application in plant breeding. Euphytica 128, 9–17 (2002).

Grover, A. & Sharma, P. C. Development and use of molecular markers: past and present. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 36, 290–302 (2016).

Coşkun, Ö. F., Toprak, S. & Mavi, K. Genetic diversity and association mapping for salinity tolerance in watermelon (Citrullus Lanatus L.). J. Crop Health 77(2), 73 (2025).

Erkek, B. et al. Natural diversity of Crataegus monogyna Jacq. in Northeastern Türkiye encompassing morphological, biochemical, and molecular features. Horticulturae 11(3), 238 (2025).

Toprak, S., Coşkun, Ö. F. & Mavi, K. Çerezlik karpuz genotiplerinin ISSR tekniği ile moleküler karakterizasyonu. Erciyes Tarım ve Hayvan Bilimleri Dergisi 6(1), 51–58 (2023).

Collard, B. C. Y. & Mackill, D. J. Start codon targeted (SCoT) polymorphism: a simple, novel DNA marker technique for generating gene-targeted markers in plants. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 27, 86–93 (2009).

Jedrzejczyk, I. Genome size and SCoT markers as tools for identification and genetic diversity assessment in Echinacea genus. Ind. Crops Prod. 144, 112055 (2020).

Abulela, H. A. et al. Evaluation of the morpho-physiological traits and the genetic diversity of some Egyptian bread wheat cultivars under salt stress conditions. Cereal Res. Commun. 50, 733–753 (2022).

Mulpuri, S., Muddanuru, T. & Francis, G. Start codon targeted (SCoT) polymorphism in toxic and non-toxic accessions of Jatropha curcas L. and development of a codominant SCAR marker. Plant Sci. 207, 117–127 (2013).

Gupta, P. K. & Rustgi, S. Molecular markers from the transcribed/expressed region of the genome in higher plants. Funct. Integr. Genomics 4, 139–162 (2004).

Xanthopoulou, A. et al. Comparative analysis of genetic diversity in Greek Genebank collection of summer squash (Cucurbita pepo) landraces using start codon targeted (SCoT) polymorphism and ISSR markers. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 9, 14–21 (2015).

Tyagi, R. et al. Genetic diversity and population structure detection in sponge gourd (Luffa cylindrica) using ISSR, SCoT and morphological markers. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 26, 119–131 (2020).

Kumar, J. & Agrawal, V. Assessment of genetic diversity, population structure and sex identification in dioecious crop, Trichosanthes dioica employing ISSR SCoT and SRAP markers. Heliyon 5, e01346 (2019).

Gogoi, B., Wann, S. B. & Saikia, S. P. Comparative assessment of ISSR, RAPD, and SCoT markers for genetic diversity in Clerodendrum species of North East India. Mol. Biol. Rep. 47, 7365–7377 (2020).

Abouseada, H. H. et al. Genetic diversity analysis in wheat cultivars using SCoT and ISSR markers, chloroplast DNA barcoding and grain SEM. BMC Plant Biol. 23, 193 (2023).

Jahangir, M. & Nasernakhaei, F. Molecular characterization of Cressa cretica L. Using SCoT and ISSR markers. J. Genet. Resour. 11, 126–131 (2025).

Nasri, F., Zakizadeh, H., Vafaee, Y. & Mozafari, A. A. Callus induction and plant regeneration of Chrysanthemum morifolium and C coccineum via direct and indirect organogenesis and genetic fidelity analysis using IRAP, ISSR and SCoT molecular markers. J. Ornam. Plants 8, 265–284 (2018).

Elgohary, M. E. et al. Integrating SCoT, CBDP, and ISSR molecular markers for genetic diversity assessment and taxonomic authentication of some Asteraceae species in Egypt. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. (2025).

Baghizadeh, A. & Dehghan, E. Efficacy of SCoT and ISSR markers in assessment of genetic diversity in some Iranian pistachio (Pistacia vera L) cultivars. Pistachio Health J. 1, 37–43 (2018).

Keshavarzi, M., Tabaripour, R. & Ullah, F. Assessment of SCoT and ISSR molecular markers in genetic diversity of rigid ryegrass (Lolium rigidum Gaud) in Iran. BMC Genet. 23, 12 (2022).

Kirkbride, J. H. Biosystematic Monograph of the Genus Cucumis (Cucurbitaceae): Botanical Identification of Cucumbers and Melons (Parkway Publishers, 1993).

Bates, D., Merrick, L. & Robinson, R. Minor cucurbits: Benincasa, Lagenaria, Luffa, Sechium, and other genera (Cucurbitaceae). in Evolution of Crop Plants (eds. Smartt, J. & Simmonds, N. W.) 105–111 (Longman, 1995).

Mccreight, J. D., Nerson, H. & Grumet, R. Melon: Cucumis melo L. In: Genetic Improvement of Vegetable Crops (eds. Kalloo, G. & Bergh, B. O.) 267–294 (Pergamon Press, 1993).

Sabato, D., Esteras, C., Grillo, O., Pico, B. & Bacchetta, G. Seeds morpho-colourimetric analysis as complementary method to molecular characterization of melon diversity. Sci. Hortic. 192, 441–452 (2015).

Rad, N. Assessment of genetic diversity among melon accessions using graphical principal component and cluster analysis. Iraqi J. Agric. Sci. 49, 1–12 (2018).

Ghorbani, E., Motallebi-Azar, A. & Bolandnazar, S. Agro-Morphological Variation in Some Iranian Melon (Cucumis melo L) genotypes revealed by multivariate analysis. Indian J. Agric. Res. 54, 161–167 (2020).

Danesh, M., Lotfi, M. & Azizinia, S. Genetic diversity of Iranian melon cultigens revealed by AFLP markers. Biharean Biol. 9, 1–6 (2015).

Dastranji, N. et al. Assessment of genetic diversity of some of Iranian snake melon (Cucumis melo var. flexuosus) accessions using morphological markers. Plant Prod. 39, 15–26 (2016).

Al-Juboori, A. W. A., Ismail, E. N. & Alwan, K. A. Molecular and morphological indicators (Qutha) Cucumis melo planted in Iraq. Iraqi J. Agric. Sci. 50, 835–841 (2018).

Maleki, M., Shojaeiyan, A. & Monfared, S. R. Population structure, morphological and genetic diversity within and among melon (Cucumis melo L) landraces in Iran. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 16, 599–606 (2018).

Al Khazraji, H. A., Abd, A. M. & Abdulla, A. A. The determination of the genetic distance of various snake melon Cucumis melo var flexuosus cultivars using inter simple sequence repeat technique (ISSR). Basrah J. Agric. Sci. 34, 111–123 (2021).

Al-Juboori, A. W. A. & Ismail, E. N. Genetic diversity and morphological markers of Cucumis melo L. in Iraq. Iraqi J. Agric. Sci. 50, 835–841 (2018).

Aziz, R. R. & Tahir, N. A. R. Genetic diversity and structure analysis of melon (Cucumis melo L.) genotypes using URP, SRAP, and CDDP markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 70, 799–813 (2023).

Murray, M. G. & Thompson, W. F. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 8, 4321–4325 (1980).

Gholami, S. et al. Molecular characterization of endangered Iranian terrestrial orchids using ISSR markers and association with floral and tuber-related phenotypic traits. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 27, 53–68 (2021).

Gholami, S. et al. Exploring genetic variations in threatened medicinal orchids using start codon targeted (SCoT) polymorphism and marker-association with seed morphometric traits. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 27, 769–785 (2021).

Rahmani, M.-S. et al. Genetic differentiation in Quercus infectoria from northwest of Iran revealed by different nuclear markers. Tree Genet. Genomes 11, 1–9 (2015).

Peakall, R. & Smouse, P. E. GENALEX 6: Genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Mol. Ecol. Notes 6, 288–295 (2006).

Hammer, Ø., Harper, D. A. T. & Ryan, P. D. PAST: Paleontological Statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 4, 1–9 (2001).

Pritchard, J. K., Stephens, M. & Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155, 945–959 (2000).

Falush, D., Stephens, M. & Pritchard, J. K. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: Dominant markers and null alleles. Mol. Ecol. Notes 7, 574–578 (2007).

Evanno, G., Regnaut, S. & Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 14, 2611–2620 (2005).

Earl, D. A. & VonHoldt, B. M. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 4, 359–361 (2012).

Gorji, A. M., Poczai, P., Polgar, Z. & Taller, J. Efficiency of arbitrarily amplified dominant markers (SCoT, ISSR and RAPD) for diagnostic fingerprinting in tetraploid potato. Am. J. Potato Res. 88, 226–237 (2011).

Tahir, N. et al. Assessment of genetic variation and population structure in Iraqi barley accessions using ISSR, CDDP, and SCoT markers. Biol. Life Sci. Forum 11, 4 (2023).

Jing, Z. et al. Genetic diversity and relationships between and within persimmon (Diospyros L) wild species and cultivated varieties by SRAP markers. Plant Syst. Evol. 299, 1485–1492 (2013).

Agarwal, A. et al. Assessment of genetic diversity in 29 rose germplasms using SCoT marker. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 31, 780–788 (2019).

Gupta, P. et al. DNA fingerprinting and genetic relationships similarities among the accessions/species of Ocimum using SCoT and ISSR markers system. Mol. Biotechnol. 63, 446–457 (2021).

Kumar, A. et al. Estimation of genetic diversity utilizing gene-targeted SCoT markers and morpho-chemotypic analyses in Senna alexandrina Mill. (Senna). Ecol. Genet. Genom. 31, 100252 (2024).

Goswami, B., Gadi, B. & Rao, S. R. Morphological and molecular markers based assessment of genetic diversity of a valuable endemic plant Lasiurus sindicus Henr in the arid region of Rajasthan India. Arid Land Res. Manag. 36, 298–313 (2022).

Amom, T. et al. Efficiency of RAPD, ISSR, iPBS, SCoT and phytochemical markers in the genetic relationship study of five native and economical important bamboos of North-East India. Phytochemistry 174, 112330 (2020).

Bidyananda, N. et al. Plant genetic diversity studies: Insights from DNA marker analyses. Int. J. Plant Biol. 15, 607–640 (2024).

Paris, H. S. et al. Genetic relationships in Cucurbita pepo (pumpkin, squash, gourd) as viewed with high frequency oligonucleotide–targeting active gene (HFO–TAG) markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 62, 1095–1111 (2015).

Pandey, A. et al. Genetic diversity and population structure of watermelon (Citrullus sp) genotypes. 3 Biotech 9, 1–14 (2019).

Amom, T. et al. Conservation strategies for endemic Dendrocalamus manipureanus: A study on genetic diversity and population structure based on molecular and phytochemical markers. S. Afr. J. Bot. 152, 106–123 (2023).

Tiwari, G. et al. Study of arbitrarily amplified (RAPD and ISSR) and gene targeted (SCoT and CBDP) markers for genetic diversity and population structure in Kalmegh [Andrographis paniculata (Burm f) Nees]. Ind. Crops Prod. 86, 1–11 (2016).

Hromadová, Z. et al. Efficiency of RAPD and SCoT markers in the genetic diversity assessment of the common bean. Plants 12, 2763 (2023).

Dadras, A. Evaluation of genetic diversity of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) cultivars using AFLP molecular marker. MSc Thesis, Shahid Bahonar University of Kerman (2012).

Mansoory, A. et al. Evaluation of genetic diversity in three Diospyros species, collected from different regions in Iran, using ISSR and SCoT molecular markers. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 22, 235–248 (2022).

Sayed Ibrahim, A. et al. Physiological, biochemical, and molecular characterization of some cucumber (Cucumis sativus L) genotypes. Int. J. Veg. Sci. 30, 673–694 (2024).

Khodaee, L. et al. Assessment of genetic diversity among Iranian Aegilops triuncialis accessions using ISSR, SCoT, and CBDP markers. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 19, 5 (2021).

Tanaka, K. et al. Melon diversity on the silk road by molecular phylogenetic analysis in Kazakhstan melons. Breed. Sci. 73, 219–229 (2023).

Yermagambetova, M. et al. Conspectus of the genus Juniperus L growing in Kazakhstan. Proc. Appl. Bot. Genet. Breed. 183, 161–170 (2022).

Whitaker, T. W. & Davis, G. N. Cucurbits: Botany, Cultivation and Utilization (Leonard Hill Books Limited, 1962).

Cao, Y.-N. et al. Inferring spatial patterns and drivers of population divergence of Neolitsea sericea (Lauraceae), based on molecular phylogeography and landscape genomics. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 126, 162–172 (2018).

Dilipan, E. & Nisha, A. J. Assessing salinity tolerance and genetic variation in mung bean (Vigna radiata) through CAAT box and SCoT marker analysis. Ecol. Genet. Genom. 32, 100266 (2024).

Patel, S. et al. Deciphering the genetic architecture of resistance to Corynespora cassiicola in soybean (Glycine max L.) by integrating genome-wide association mapping and RNA-Seq analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1255763 (2023).

Jahantigh, M. & Jahantigh, M. Effect of clay-pot irrigation on Citrullus colocynthis plant growth for arid land restoration (A case study: Southeast of Iran). Sustainability 15, 16267 (2023).

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dara Omar Mohammad 30%- Material preparation, data collection and analysis Yavar Vafaee 20%- contributed to the study conception and design, read and approved the final manuscript Rahele Ghanbari Moheb Seraj 15%- Writing the paper, edit and scientific corrections of the paper. Ali Akbar Mozafari 20%- contributed to the study conception, read and approved the final manuscript. Nawroz Abdul-razzak Tahir 15%- Advice on data collection and analysis.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was not required for this study. The manuscript has been read and approved by all named authors and that there are no other persons who satisfied the criteria for authorship but are not listed. This study, including the collection and use of plant materials (cultivated and wild accessions of Cucumis melo L.), was conducted in strict accordance with institutional, national, and international guidelines and relevant legislation. No endangered or protected species were involved, and all experimental procedures complied with the ethical standards and regulations applicable to plant research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohammad, D.O., Vafaee, Y., Seraj, R.G.M. et al. Genetic diversity of native Cucumis melo L. accessions from Iran and Iraq revealed by SCoT and ISSR markers. Sci Rep 16, 1715 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31312-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31312-7