Abstract

A total of 150 patients with pathologically confirmed unilateral invasive breast cancer who underwent preoperative 3.0T MRI (including SyMRI sequences) at our institution were enrolled in the development set, while an external validation cohort consisted of 98 patients from Yidu Central Hospital. Based on IHC/FISH results, patients were categorized into HER2-low, HER2-zero and HER2-over groups. Two radiologists independently measured T1, T2, PD, and ADC values of the lesions. Logistic regression analysis was employed to identify the most effective predictors of HER2 expression status, and ROC curve analysis was performed to evaluate their discriminative ability. Univariate logistic regression indicated that the T2 value was a significant predictor for differentiating HER2 expression status. In the development set, T2 values demonstrated moderate diagnostic performance, with AUC values of 0.813 for HER2-low vs. over, 0.816 for HER2-zero vs. over and 0.876 for HER2-zero vs. low. Similarly, in the external validation set, T2 values showed moderate diagnostic efficacy, with AUCs of 0.837, 0.808 and 0.835 for the respective comparisons. T2 quantification derived from SyMRI shows promise as a noninvasive biomarker for identifying HER2-low-expressing breast cancer, supporting its potential role in guiding individualized treatment strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most prevalent malignancy among women globally, accounting for approximately one-third of all female cancers and representing the leading cause of cancer-related mortality in women1. It is now widely recognized as a heterogeneous disease comprising distinct molecular and histological subtypes. Based on these classifications, breast cancer is broadly divided into three principal categories: hormone receptor-positive (estrogen receptor-positive [ER+] and/or progesterone receptor-positive [PR+]), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive (HER2+), and triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)2. HER2 is a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor that plays a crucial role in promoting tumor cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis. It is both a key oncogenic driver and an important biomarker for prognostication and therapeutic targeting in breast cancer3,4,5. Traditionally, breast cancers have been dichotomized into HER2-positive and HER2-negative groups based on the extent of HER2 expression. Standard treatment for HER2-positive breast cancer involves a combination of anti-HER2 monoclonal antibodies—such as trastuzumab and pertuzumab—with chemotherapy. In contrast, patients with HER2-negative tumors have historically derived no clinical benefit from anti-HER2 monoclonal antibodies6. However, the development of novel anti-HER2 antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) with demonstrated efficacy in HER2-low breast cancers has prompted the recognition of HER2-low as a potential new therapeutic subtype7. Approximately 45%–55% of breast cancers exhibit HER2-low expression, emphasizing the need for accurate identification of this subgroup4.

Currently, HER2 expression is assessed using immunohistochemistry (IHC) and in situ hybridization (ISH), typically performed on core needle biopsy specimens. These procedures are invasive and may fail to capture tumor heterogeneity, potentially leading to misclassification or underestimation of disease burden8. Moreover, HER2 expression is known to be biologically dynamic, with status changes observed during disease progression, possibly influenced by prior treatments9,10. Recent advances in imaging and radiomics have introduced non-invasive, dynamic frameworks for evaluating tumor biology. Radiomic analyses using ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have shown promise in HER2 status assessment11,12. Nonetheless, their clinical application remains limited due to variability in diagnostic accuracy and poor reproducibility. Consequently, there is a growing demand for rapid, reproducible, and standardized imaging-based methods to evaluate HER2 expression levels in breast cancer.

Synthetic magnetic resonance imaging (SyMRI) is an emerging quantitative MRI technique that employs a multi-dynamic, multi-echo (MDME) sequence within a single scan to acquire T1-weighted, T2-weighted, proton density (PD)-weighted, and inversion recovery images, along with generating quantitative T1, T2, and PD maps. This approach reduces scan time while producing measurements that reflect intrinsic tissue properties, independent of scanner model or imaging parameters at a given magnetic field strength5,13. SyMRI has been successfully applied in various oncologic contexts, including tumor grading, quantitative assessment of bone metastases in prostate cancer, and prediction of response to neoadjuvant therapy in locally advanced rectal cancer14,15,16,17. A prior study demonstrated that SyMRI-derived quantitative parameters could differentiate IHC expression profiles in breast cancer with greater accuracy than apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values18. However, the utility of SyMRI in identifying HER2-low breast cancer remains unconfirmed.

We hypothesize that differences in HER2 expression among patients with invasive breast cancer are reflected in the quantitative parameters derived from SyMRI. This study aims to evaluate the diagnostic performance of SyMRI-based quantitative metrics in identifying HER2-low breast cancer. We present this article in accordance with the STARD reporting checklist.

Materials and methods

Ethics approval

Due to the retrospective nature of this study, the Ethics Committee of Weifang People’s Hospital waived the requirement for informed consent (Ethics Review No. KYLL20230526-9) and approved all experimental protocols, which adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study participants

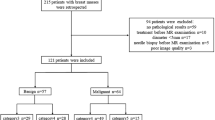

Data were collected from 248 female patients who underwent breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at Weifang People’s Hospital and Weifang Yidu Central Hospital between March 2023 and September 2024 for evaluation of breast mass lesions. All patients subsequently underwent surgical resection, and final diagnoses were confirmed via histopathological examination of the surgical specimens. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) histopathological confirmation of invasive breast cancer and (2) completion of breast MRI before surgery. Exclusion criteria included: (1) non-invasive breast cancer on postoperative pathology; (2) prior neoadjuvant therapy or biopsy before MRI; (3) suboptimal MRI image quality or significant artifacts that compromised image interpretation. A total of 201 patients met the eligibility criteria. All had unilateral lesions, although two patients exhibited multifocal tumors in the same breast; in these cases, the largest lesion was selected for analysis. HER2 expression status—categorized as HER2-zero, HER2-low, or HER2-overexpressing—was determined using immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization. A flowchart detailing the patient selection process is outlined in Fig. 1.

MRI examination

All MRI scans were performed using a 3.0T scanner equipped with a dedicated 16-channel phased-array breast coil. Patients were positioned prone, feet-first, with both breasts suspended within the coil and arms elevated above the head. Standard sequences included axial T1-weighted imaging (T1WI), T2-weighted imaging (T2WI), fat-suppressed T2WI, and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). This was followed by acquisition of the axial SyMRI sequence (Magnetic Resonance Image Compilation, MAGIC) and ultrafast dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging (DISCO). Prior to contrast administration, three baseline phases were obtained. In the course of standard magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the parameters for the conventional non-contrast scan utilizing the axial T1-weighted imaging (T1WI) sequence without fat saturation were established as follows: recovery time (TR) was set to 770 milliseconds, echo time (TE) to 7.56 milliseconds, field of view (FOV) to 512 mm × 512 mm, and slice thickness to 5 mm. For the axial T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) sequence with fat saturation, the parameters included a TR of 3000 milliseconds, a TE of 85.54 milliseconds, an FOV of 512 mm × 512 mm, and a slice thickness of 5 mm. In the case of the axial diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) sequence, the TR was 6530 milliseconds, TE was 77.20 milliseconds, slice thickness remained at 5 mm, and the b value was set at 0/1000 s/mm². Subsequently, an axial synthetic MRI (SyMRI) sequence was performed with parameters of TR at 4000 milliseconds, TE at 12 milliseconds, and an FOV of 512 mm × 512 mm. Following this, an axial dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) was executed with a TR of 5.43 milliseconds, TE of 1.67 milliseconds, FOV of 512 mm × 512 mm, and slice thickness of 3.2 mm. A gadolinium-based contrast agent (Gd-DTPA, 0.1 mmol/kg) was then injected via the antecubital vein at 2.0 mL/s, followed by an equal volume of saline flush at the same rate. Each of the 23 imaging phases was acquired at 5-second intervals.

Image analysis

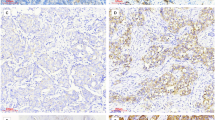

Post-processing was performed on a GE Healthcare workstation using proprietary SyMRI software to automatically generate quantitative T1, T2, and proton density (PD) maps. Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps were generated automatically during DWI acquisition (Figs. 2 and 3). Image analysis was independently conducted by two radiologists with over five years of experience in breast MRI, both blinded to clinical and pathological data. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Initially, the radiologists used DWI and contrast-enhanced T1WI to identify the slice with the largest tumor diameter. From this slice, the clearest corresponding quantitative parameter map was selected, and each radiologist manually delineated the region of interest (ROI). The ROIs were automatically propagated to the corresponding T1, T2, and PD maps. Each measurement was repeated three times, and the average values were recorded. During ROI placement, care was taken to exclude necrotic areas and peritumoral edema. In multifocal cases, only the largest lesion was evaluated. ADC values were obtained in a similar manner, with efforts made to maintain consistent ROI size across all parameter maps.

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-low-expressing breast cancer confirmed by surgical pathology in the right breast of a 62 -year-old woman. The ADC (a) showed a solid mass (red arrow). The SyMRI values of ADC (a), PD (b), T1 (c) and T2 (d) are 1.01 × 10-3mm2/s,75ms,1155ms and 80.6ms respectively.

Non human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-low-expressing breast cancer confirmed by surgical pathology in the left breast of a 64 -year-old woman. The ADC (a) showed a solid mass (red arrow). The ADC (a) showed a solid mass (red arrow). The SyMRI values of ADC (a), PD (b), T1(c) and T2 (d) are 1.03 × 10-3mm2/s,72ms,1135ms and 97.7ms respectively.

Pathological evaluation

Clinical and pathological data were extracted from the electronic medical record system. All pathological evaluations were based on surgical breast cancer specimens. Tumor size was determined using imaging-based measurements of maximum tumor diameter. Histological grade was classified as low grade (Grade I or II) or high grade (Grade III). HER2 status was categorized as HER2-zero (IHC score of 0), HER2-low (IHC score of 1 + or 2 + with negative FISH), or HER2-positive (IHC score of 3 + or 2 + with positive FISH). Estrogen and progesterone receptor (ER/PR) status was considered positive when expression exceeded 1%, and negative when ≤ 1%. The Ki-67 proliferation index was dichotomized using a 14% threshold, with values < 14% denoting low expression and ≥ 14% indicating high expression.

Statistical analysis

In our study, all statistical analyses were performed using the R software (version 4.2.2), along with MSTATA software (www.mstata.com). Comparisons of T1, T2, proton density (PD), and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values between HER2-low and non-HER2-low breast cancers were conducted using either independent sample t-tests or Mann–Whitney U tests, depending on data distribution and variance homogeneity. Inter-observer agreement between the two radiologists was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was employed to evaluate the diagnostic performance of quantitative parameters in distinguishing HER2-low expression, with the area under the curve (AUC) used to quantify discriminative ability.

Results

Patient characteristics

A cohort of 201 female patients diagnosed with invasive breast cancer was analyzed. Based on immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization, patients were stratified into three groups: HER2-low, HER2-zero and HER2-over expression. The clinicopathological characteristics of the cohort are summarized in Table 1. No statistically significant differences were detected among the groups for age, menstrual status, diameter, location, histologic grade, ER status, PR status, Ki-67 index and or ALN status, indicating balanced baseline characteristics between the groups.

Assessment of interobserver agreement

Interobserver agreement between the two radiologists was excellent, with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) of 0.994 (95% CI: 0.988–0.997) for T1, 0.991 (0.982–0.995) for T2, 0.995 (0.991–0.998) for PD, and 0.985 (0.970–0.993) for ADC.

Comparisons of quantitative values among Her2-zero, HER2-low and HER2-over breast cancer

Table 2 summarizes the differences in SyMRI-derived quantitative parameters and ADC values between HER2-low, HER2-zero and -HER2-over expression breast cancer. Notably, a variance analysis demonstrates significant group-wise variations in both ADC and T2 metrics. No significant differences were observed in T1and PD values in three groups.

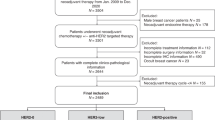

Table 3; Fig. 4 present the diagnostic performance of SyMRI-derived T2 and conventional ADC metrics in distinguishing HER2-subtyped breast cancers (BCs).

In development set, for differentiation between HER2-low and HER2-overexpressing tumors, T2 values exhibited excellent discriminative ability (AUC: 0.813; sensitivity: 85.40%; specificity: 69.00%; accuracy: 77.80%). ADC metrics demonstrated superior performance (AUC: 0.827; sensitivity: 93.80%; specificity: 76.20%; accuracy: 85.60%). For distinguishing HER2-zero from HER2-overexpressing cases, both T2 and ADC parameters showed high diagnostic efficacy, with AUCs of 0.816 and 0.877, respectively. In differentiating HER2-zero from HER2-low expression, T2 (AUC: 0.876) and ADC (AUC: 0.927) both exhibited exceptional discriminatory power, with ADC approaching near-perfect classification (AUC > 0.9). Similarly, in the external validation set, T2 values also demonstrated excellent discrimination for HER2-low versus HER2-overexpressing tumors (AUC: 0.837; sensitivity: 96.9%; specificity: 65.50%; accuracy: 82.0%), while ADC metrics performed comparably (AUC: 0.835; sensitivity: 89.7%; specificity: 56.2%; accuracy: 72.1%). For HER2-zero versus HER2-overexpressing classification, T2 and ADC achieved AUCs of 0.808 and 0.806, respectively. In distinguishing HER2-zero from HER2-low expression, T2 and ADC yielded AUCs of 0.835 and 0.867, respectively.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis evaluating the diagnostic efficacy of quantitative indices in HER2 expression classification in development (a, b,c) and external set (d, e,f). (a, d) HER2-zero vs. HER2-low discrimination, (b, e) HER2-zero vs. HER2-overexpression discrimination, (c, f) HER2-low vs. HER2-over expression discrimination.

Discussion

This study evaluated the clinical relevance of quantitative parameters derived from SyMRI in conjunction with ADC values for identifying HER2-low invasive breast cancer. Results revealed that the T2 relaxation time in HER2-low breast cancer was significantly lower than in non-HER2-low cases, with AUC values exceeding 0.80 in both the development and external validation sets, underscoring the diagnostic potential of T2 mapping for HER2-low identification. In contrast, T1 and proton density (PD) values did not demonstrate statistically significant differences in the three groups of development set.

Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease comprising distinct molecular subtypes that differ in prognosis and therapeutic responsiveness. The HER2 gene plays a central role in breast cancer pathophysiology, informing both treatment decisions and prognostic assessments. The advent of anti-HER2 monoclonal antibodies targeting HER2 overexpression has significantly improved outcomes for patients with HER2-positive breast cancer. However, only approximately 15% of breast cancers are classified as HER2-positive, leaving a substantial proportion of patients ineligible for HER2-targeted therapies19. Recently, a Phase III clinical trial demonstrated that trastuzumab deruxtecan—an antibody–drug conjugate—markedly improved progression-free and overall survival in patients with HER2-low metastatic breast cancer20. These findings have elevated HER2-low status to clinical prominence, prompting the adoption of a three-tier classification system based on HER2 expression levels: HER2-positive, HER2-low, and HER2-zero.

Current research efforts increasingly focus on the accurate identification of HER2-low breast cancer patients who may benefit from antibody–drug conjugate therapies. Bannier et al. developed a deep learning (DL) model to aid pathologists in diagnosing HER2-low cases, achieving identification rates as high as 97% for both HER2-low and HER2-positive breast cancer subtypes21. Zheng et al. reported that radiomics features derived from diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) could effectively differentiate HER2-low breast cancers from HER2-overexpressing and HER2-zero tumors, with AUC values ranging from 0.778 to 0.782 across multiple validation cohorts22. Similarly, Liu et al. proposed an integrated model that combines conventional MRI features with radiomics data to predict HER2 status in invasive breast cancer, outperforming a radiomics-only model (AUC:0.842vs.0.797), thereby enhancing noninvasive preoperative stratification for HER2-directed therapy23. Chen et al. demonstrated that radiomics features extracted from dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) could be leveraged to build a machine learning model capable of reliably distinguishing HER2-low from HER2-positive breast cancer cases24.

Quantitative MRI techniques offer objective and reproducible metrics that minimize inter-observer variability in disease characterization. DWI, in particular, provides the ADC as a quantitative measure that reflects tissue microstructure and histopathological features25,26,27. In clinical breast imaging, ADC values are widely used to discriminate between benign and malignant breast lesions and to evaluate prognostic biomarkers18,28,29,30. Several studies have explored associations between ADC values and HER2 expression, yielding inconsistent results. Park et al., in a study involving 110 invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) cases, found significantly higher ADC values in HER2-positive tumors compared to HER2-negative ones (p = 0.02)31. Similarly, Lee et al. reported a statistically significant correlation between HER2 status and ADC measurements32. However, Duc et al., in a cohort of 49 breast cancer patients, observed no significant relationship between HER2 expression and either mean ADC or minimum ADC values29. This lack of consensus is further reflected in additional studies reporting comparable null associations18,33. Previous investigations employed binary classifications of HER2 expression; however, the criteria for stratification varied across studies, potentially contributing to inconsistent findings. In the context of a ternary HER2 classification, we assessed the potential of ADC values to distinguish breast cancers exhibiting HER2-low expression. Our analysis revealed significant difference in ADC values in HER2-low, HER2 zero and HER2 over breast cancer subtypes. While earlier studies reported a significant inverse correlation between HER2 expression and ADC values, our results did not align with this trend. The established association between ADC values and tumor cell density—wherein high-grade tumors, due to increased cellularity, exhibit reduced ADC values—may not sufficiently explain the heterogeneity observed in HER2-low cases31. Whether HER2-low breast cancer constitutes a distinct biological or clinical entity remains unresolved. Prognostic studies on HER2-low expression have yielded inconsistent outcomes9,34, which may partly account for the lack of a significant correlation with ADC values observed in our study.

SyMRI is an emerging, single-sequence multiparametric imaging technique that quantifies intrinsic tissue magnetic properties, including longitudinal (T1) and transverse (T2) relaxation times, as well as PD35. This contrast-free, time-efficient, and scanner-independent modality is increasingly applied in breast MRI. Gao et al. demonstrated that SyMRI-derived quantitative parameters could serve as imaging biomarkers for stratifying breast cancers by receptor status and proliferation rate33. Notably, HER2-positive tumors exhibited significantly lower PD values compared to HER2-negative tumors (p = 0.048; AUC = 0.629 for predicting HER2 status). Similarly, Li et al. divided 56 patients with invasive ductal carcinoma into high and low HER2 expression groups, reporting that the standard deviations of pre-contrast PD and T1 values were significantly associated with HER2 status (AUC = 0.746)18. In our study, HER2-low breast cancers showed significantly lower T2 values than other subtypes (p < 0.001), although no significant differences were observed in T1 or PD values. The diagnostic performance of T2 values for identifying HER2-low expression yielded AUCs of 0.813 and 0.876 in development set. These differences in SyMRI parameters across molecular subtypes likely reflect variations in tumor microstructure and interstitial fluid content associated with receptor status. Variations in intrinsic tissue properties—specifically T1, T2, and PD—are ultimately influenced by these biological differences36,37. Although the precise mechanisms remain unclear, the significantly reduced T2 values observed in HER2-low breast cancers may reflect a combination of factors, including altered intracellular and extracellular water distribution, microvascular perfusion, and increased tumor cell density. The T2 value is predominantly sensitive to alterations in water content (e.g., edema) and serves as an indirect indicator of ECM remodeling linked to fibrosis (e.g., collagen degradation) or inflammatory processes involving cellular infiltration and necrosis38,39. While T2 mapping has a well-established relationship with water distribution, its correlation with tumor density remains understudied. Further investigations with larger cohorts are warranted to elucidate the variation in SyMRI-derived quantitative parameters across more refined subgroups, such as HER2-negative, HER2-low, and HER2-positive breast cancers. Such research could enhance our understanding of the pathological underpinnings driving the quantitative differences observed in HER2-low expression tumors relative to other subtypes.

This retrospective, single-center study is subject to inherent limitations, including potential selection bias and a relatively modest sample size (excluding patients with HER2 zero), which may limit the generalizability and statistical power of the findings. Therefore, multicenter, large-scale prospective studies are essential to validate and extend these preliminary results. Moreover, our analysis was confined to mean values of SyMRI-derived quantitative parameters. Future work should consider incorporating texture analysis, which may offer a more nuanced assessment of tumor heterogeneity and provide deeper insights into the phenotypic characterization of breast cancer.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that quantitative T2 values obtained via SyMRI hold promise for identifying patients with HER2-low expression breast cancer. This technique may serve as a non-invasive, dynamic imaging biomarker for monitoring HER2-low status, thereby contributing to the advancement of personalized and precision-based treatment strategies.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

AKRAM, M. et al. Awareness and current knowledge of breast cancer. Biol. Res. 50 (1), 33 (2017).

BARZAMAN, K. et al. Breast cancer: Biology, biomarkers, and treatments. Int. Immunopharmacol. 84, 106535 (2020).

HAMILTON, E. et al. Targeting HER2 heterogeneity in breast cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 100, 102286 (2021).

HONG, B. et al. Consensus on clinical diagnosis and medical treatment of HER2-low breast cancer (2022 edition). J. Natl. Cancer Cent. 3 (4), 266–272 (2023).

LI, Q. et al. Histogram analysis of quantitative parameters from synthetic MRI: correlations with prognostic factors and molecular subtypes in invasive ductal breast cancer. Eur. J. Radiol. 139, 109697 (2021).

CORTI, C. et al. HER2-Low breast cancer: A new Subtype?. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 24 (5), 468–478 (2023).

TARANTINO, P. et al. ESMO expert consensus statements (ECS) on the definition, diagnosis, and management of HER2-low breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 34 (8), 645–659 (2023).

ZHANG, L. et al. Predicting of Ki-67 expression level using Diffusion-Weighted and synthetic magnetic resonance imaging in invasive ductal breast Cancer. Breast J. 2023, 6746326 (2023).

TARANTINO, P. et al. Evolution of low HER2 expression between early and advanced-stage breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer. 163, 35–43 (2022).

YAN, S. et al. Unveiling the mysteries of HER2-low expression in breast cancer: Pathological response, prognosis, and expression level alterations. World J. Surg. Oncol. 22 (1), 248 (2024).

CUI, H. et al. Radiogenomic analysis of prediction HER2 status in breast cancer by linking ultrasound radiomic feature module with biological functions. J. Transl Med. 21 (1), 44 (2023).

RAMTOHUL, T. et al. Multiparametric MRI and radiomics for the prediction of HER2-Zero, -Low, and -Positive breast Cancers. Radiology 308 (2), e222646 (2023).

HAGIWARA, A. et al. SyMRI of the brain: rapid quantification of relaxation rates and proton Density, with synthetic MRI, automatic brain Segmentation, and Myelin Measurement. Invest. Radiol. 52 (10), 647–657 (2017).

ARITA, Y. et al. Quantitative assessment of bone metastasis in prostate cancer using synthetic magnetic resonance Imaging. Invest. Radiol. 54 (10), 638–644 (2019).

CAI, Q. et al. Investigation of synthetic magnetic resonance imaging applied in the evaluation of the tumor grade of bladder Cancer. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 54 (6), 1989–1997 (2021).

CUI, Y. et al. Diagnosis and grading of prostate cancer by relaxation maps from synthetic MRI. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 52 (2), 552–564 (2020).

LIAN, S. et al. Quantitative synthetic MRI for predicting locally advanced rectal cancer response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Eur. Radiol. 33 (3), 1737–1745 (2023).

LI, X. et al. Synthetic MRI in breast cancer: differentiating benign from malignant lesions and predicting immunohistochemical expression status. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 17978 (2023).

TARANTINO, P. et al. HER2-Low breast cancer: pathological and clinical Landscape. J. Clin. Oncol. 38 (17), 1951–1962 (2020).

MODI, S. et al. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-Low advanced breast Cancer. N Engl. J. Med. 387 (1), 9–20 (2022).

BANNIER, P. A. et al. Development of a deep-learning model tailored for HER2 detection in breast cancer to aid pathologists in interpreting HER2-low cases. Histopathology 85 (3), 478–488 (2024).

ZHENG, S. et al. Discrimination between HER2-overexpressing, -low-expressing, and -zero-expressing statuses in breast cancer using multiparametric MRI-based radiomics. Eur. Radiol. 34 (9), 6132–6144 (2024).

LIU, W. et al. A comprehensive model outperformed the single radiomics model in noninvasively predicting the HER2 status in patients with breast cancer. Acad Radiol. (2024).

CHEN, X. et al. Machine learning models for differential diagnosing HER2-low breast cancer: A radiomics approach. Med. (Baltim). 103 (33), e39343 (2024).

IIMA, M. et al. Diffusion-Weighted MRI for the assessment of molecular prognostic biomarkers in breast Cancer. Korean J. Radiol. 25 (7), 623–633 (2024).

MARTINCICH, L. et al. Correlations between diffusion-weighted imaging and breast cancer biomarkers. Eur. Radiol. 22 (7), 1519–1528 (2012).

PARTRIDGE, S. C. et al. Diffusion-weighted breast MRI: Clinical applications and emerging techniques. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 45 (2), 337–355 (2017).

KIM, J. Y. et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging of invasive breast cancer: Relationship to distant Metastasis-free Survival. Radiology 291 (2), 300–307 (2019).

TUAN LINH, L. et al. Correlations between apparent diffusion coefficient values and histopathologic factors in breast cancer. Clin. Ter. 172 (3), 218–224 (2021).

XING, H. et al. Meta analysis of lymph node metastasis of breast cancer patients: Clinical value of DWI and ADC value. Eur. J. Radiol. 85 (6), 1132–1137 (2016).

PARK, S. H. et al. Correlations between apparent diffusion coefficient values of invasive ductal carcinoma and pathologic factors on diffusion-weighted MRI at 3.0 Tesla. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 41 (1), 175–182 (2015).

LEE, H. S. et al. Perfusion parameters in dynamic Contrast-enhanced MRI and apparent diffusion coefficient value in diffusion-weighted MRI: Association with prognostic factors in breast Cancer. Acad. Radiol. 23 (4), 446–456 (2016).

GAO, W. et al. Synthetic MRI with quantitative mappings for identifying receptor status, proliferation rate, and molecular subtypes of breast cancer. Eur. J. Radiol. 148, 110168 (2022).

DENKERT, C. et al. Clinical and molecular characteristics of HER2-low-positive breast cancer: Pooled analysis of individual patient data from four prospective, neoadjuvant clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 22 (8), 1151–1161 (2021).

QU, M. et al. Investigation of synthetic MRI with quantitative parameters for discriminating axillary lymph nodes status in invasive breast cancer. Eur. J. Radiol. 175, 111452 (2024).

BECK, K. S. et al. T1 and T2 mapping for characterization of mediastinal masses: A feasibility study. Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 74 (4), 723–736 (2023).

QU, J. et al. T1 and T2 mapping for identifying malignant lymph nodes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Imaging. 23 (1), 125 (2023).

O’BRIEN et al. T2 mapping in myocardial disease: A comprehensive review. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 24 (1), 33 (2022).

KOYUN, M. et al. Diagnostic value of T2 mapping in sacroiliitis associated with Spondyloarthropathy. Diagnostics (Basel) 15(13) (2025).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Weifang Science and Technology Development Plan project (NO.2023YX008).

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Weifang People’s Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Junzhong Liu, Zhaofeng Zheng, Yujing Chu, Mingyuan Pang, Qi Wang, Wenjuan Wang, Linkun Li, Longjiang Fang, Huanlei Zhang and Shiying Ju. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Junzhong Liu, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the Ethics Committee of Weifang people’s hospital waived the need of obtaining informed consent (Ethics Review No.KYLL20230526-9).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Zheng, Z., Chu, Y. et al. A novel biomarker for identifying HER2-low breast cancer using synthetic MRI. Sci Rep 16, 1512 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31322-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31322-5