Abstract

Biofortification of crops with beneficial micronutrients like selenium (Se) and iodine (I) is a promising strategy to enhance nutritional quality while addressing global dietary deficiencies. This study investigates the synergistic effects of foliar selenium and iodine application on basil, focusing on its nutritional composition and essential oil profile. A commercial greenhouse experiment was conducted using a factorial randomized complete block design with three replications. The experiment involved sixteen treatments including different combinations of selenium (as Na₂SeO₄) at 0, 0.5, 1.5, and 3 mg L−1 and iodine (as KI) at 0, 0.1, 0.2, and 0.4 µM. The combined biofortification, particularly the Se3-I0.4 treatment (3 mg L−1 Se + 0.4 µM I), was identified as the most effective. This optimal combination led to a 91% increase in leaf iodine content (332 vs. 174 µg kg−1.dw−1 in control) and increased the leaf selenium content to 17.72 µg kg⁻1, up from 12.70 µg kg⁻1 in the control. We observed significant increases in chlorophyll a (∼40%), chlorophyll b (∼43%), carotenoids (∼195%), and the activity of antioxidant enzymes superoxide dismutase and ascorbate peroxidase compared to the control. The treatment also altered the essential oil profile, increasing the concentration of the desirable aroma compound linalool by ∼58% while decreasing 1,8-cineole and eugenol. In conclusion, the combined foliar application, especially at the Se3-I0.4 level, effectively enhanced the nutritional and antioxidant quality of basil, presenting a promising strategy for micronutrient biofortification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global issue of inadequate iodine and selenium supply in food and animal feed affects billions of people and livestock1. A lack of these elements in daily diets can lead to various diseases and health concerns2. The root cause of this deficiency is the uneven distribution of iodine and selenium within the soil–plant-consumer system, primarily due to the limited availability of their usable forms in the soil3.

To date, the large-scale fortification of plants has primarily been implemented for selenium4. In Finland, the application of NPK fertilizers enriched with sodium selenate has led to a reduction in mortality rates from cancer and cardiovascular diseases without causing environmental contamination3. This phenomenon is largely attributed to factors such as the soil redox processes, selenium microbial reduction, and the creation of volatile methylated derivatives4.

The consumption of iodine-fortified tomatoes, carrots, and lettuce has been shown to enhance human iodine levels. The high lability of iodine, like selenium, is associated with the synthesis of volatile methylated forms microbiologically as well as its involvement in redox reactions2. These processes largely inhibit the buildup of toxic iodine concentrations in the soil, while the formation of complexes with inorganic and organic compounds significantly reduces the bioavailability of iodine to plants1.

The biological functions of selenium and iodine in animals, humans, and plants exhibit some similarities, indicating close interactions between these elements, even within plants5. Both selenium and iodine provide protection against heavy metals in biological systems6. When there are high levels of selenium and iodine absorption, plants and mammals produce volatile methylated derivatives. These similarities in the biological roles of selenium and iodine highlight the necessity of optimizing the combined selenium-iodine status in humans2. The use of agrotechnical methods for plant enrichment with different mineral elements such as Zn, Fe, selenium, and iodine, is considered an efficient and cost-effective strategy to combat deficiencies in humans and livestock4. In recent years, many research projects have focused on establishing agrotechnical guidelines for plant biofortification (fertilization)4,5,6,7. Mao, et al.8 conducted a year-long study involving the application of selenium, Zn, and iodine during the cultivation of crops such as maize, wheat, potato, soybean, cabbage, and canola. The biofortification effects of selenium, Zn, and iodine from both single and combined applications of micronutrient fertilizers were found to be similar8. Research on the photosynthetic activity of pumpkin and buckwheat sprouts found that the combined application of selenium and iodine during seed soaking had no effect9, but it did result in an increase in flavonoid content10. Landini, et al.11 found that foliar spray treatments increased the iodine uptake in nectarine, plum, and tomato fruits.

However, the limited information and inconsistent findings in some existing reports regarding plants make it challenging to obtain insights into the simultaneous enrichment of selenium and iodine4,5,6,7. A significant barrier to the advancement of agro-technical methods for applying selenium and iodine is the inadequate understanding of their interactions related to plant metabolism and growth6. Only a limited number of studies have explored this subject and confirmed the feasibility of simultaneously fertilizing plants with iodine and selenium1.

Basil is a widely used culinary herb with a high frequency of consumption across diverse cuisines and food products. Basil is valued not only for its flavor but also for its rich content of bioactive compounds, antioxidants, and essential oils, making it a functional food ingredient13. Recent research has highlighted the potential of using popular herbs and specialty crops as vehicles for micronutrient biofortification, especially for nutrients like selenium and iodine that are often deficient in human diets5. Increases in the intake of these micronutrients through commonly consumed herbs can contribute to improved dietary status, particularly when such herbs are used regularly or in processed food products (e.g., pesto, sauces, herbal teas)12. Furthermore, basil’s rapid growth cycle, high biomass yield per area, and suitability for controlled-environment agriculture make it an excellent model for testing biofortification strategies that could be adapted to other leafy or aromatic crops13.

We hypothesized that the combined foliar application of selenium and iodine would act synergistically to enhance the accumulation of both micronutrients and lead to a significant improvement in the plant’s nutritional quality, antioxidant capacity, and desirable essential oil profile compared to their individual applications. This study aims not only to enhance the nutritional value of basil itself but also to provide insights and methodologies that may be applicable to a broader range of edible plants and contribute to public health efforts addressing selenium and iodine deficiencies. Therefore, the objective of the current study was to evaluate the responses of the basil plant (Ocimum basilicum L.) to joint biofortification with selenium and iodine. Additionally, the characteristics of basil including its biochemical activity, and significant levels of biologically active compounds, were investigated.

Materials and methods

Materials

Nitric acid, sodium selenite, potassium iodide, hydrogen peroxide, tetramethylammonium hydroxide, EDTA, Na-phosphate buffer, ascorbate, polyvinylpyrrolidone, hydrogen peroxide, Tris–Ca–codylic sodium salt, glutathione reductase, t-butyl hydroperoxide, nitroblue tetrazolium, sulfanilic acid, pyrogallol, Triton X-100, hydrochloric acid, naphthyl ethylenediamide, perchloric acid, thiobarbituric acid, and trichloroacetic acid, all were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany).

Preparation of plant treatments

The basil plant (Ocimum basilicum L.) was grown in an experimental greenhouse located in Yasuj, Iran, under controlled conditions: day/night temperatures of 24 ± 4 °C, relative humidity of 40–60%, and a 16/8 h light/dark cycle using supplemental LED lighting (PAR: 300 μmol m−2 s). The cultivation utilized the mixture of perlite/cocopeat with the ratio of 50:50 (Table 1). The plants were cultivated in 100 cm × 40 cm plastic pots, fertigated with a specially formulated nutrient solution five times a day, with a 2-h interval between each application. Chemical composition of the used water and nutrition solution is given in Tables 1 and 2.

Foliar sprays were applied twice: first at 3 weeks post-transplanting and again 5 weeks later, using a handheld sprayer calibrated to deliver 50 mL per plant. Control plants received deionized water with 0.1% Tween-20 as a surfactant. Sampling was done at the end of the vegetative growth phase (75 days after sowing). For enzyme and chemical analysis, fully expanded young leaves from the middle portion of the plant were harvested 75 days after sowing (at the end of the vegetative growth phase, just prior to flowering). The harvested plant leaves were washed with deionized water, then dried in an oven at 70 °C for 48 h to a constant weight. The dried leaves were ground into a fine powder using a commercial grinder and stored in airtight containers until further analysis.

Experimental design

A commercial greenhouse experiment was conducted using a factorial randomized complete block design (RCBD) with three replications. The experiment involved sixteen treatments (Table 3), which were combinations of selenium (as sodium selenate) at 0, 0.5, 1.5, and 3 mg L⁻1 and iodine (as potassium iodide) at 0, 0.1, 0.2, and 0.4 µM.

Iodine content

To determine the iodine content in plant leaves, a spectrometry method using tetramethylammonium hydroxide reagent was used according to Smolen, et al.12 on the ground leaf powder. Briefly, 0.5 g of ground leaf powder was accurately weighed into a porcelain crucible and mixed with 2 mL of a 25% tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH) solution. The mixture was incubated in an oven at 90 °C for 3 h. After cooling, the digestate was transferred to a 15 mL centrifuge tube and made up to volume with deionized water. The sample was then centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was used for analysis.

For the analysis, 0.5 mL of the supernatant was added to a test tube containing 1.0 mL of arsenious acid solution (1.25 g L⁻1 As₂O₃ in 0.025 M H₂SO₄). The reaction was initiated by adding 1.0 mL of ceric ammonium sulfate solution (5.0 g L⁻1 (NH₄)₄Ce(SO₄)₄·2H₂O in 0.025 M H₂SO₄). The mixture was incubated at 30 °C for 30 min, after which the absorbance was measured at 420 nm using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Jenway, Model 7315, UK). A calibration curve was constructed using potassium iodide (KI) standards in the range of 0 to 50 µg L⁻1, which showed excellent linearity (R2 > 0.999). The method’s accuracy was verified using a Certified Reference Material (CRM) for trace elements in tea leaves (NCS ZC73036, China National Analysis Center). The recovery rate for iodine was 94.5%. The Method Detection Limit (MDL) and Limit of Quantification (LOQ), calculated as 3.3 and 10 times the standard deviation of the blank (n = 10), respectively, were 2.1 µg kg⁻1 and 6.4 µg kg⁻1 on a dry weight basis.

Selenium content

To determine the selenium content in plant leaves, the dried tissue of the plant was digested by hydrogen peroxide (2 mL) and nitric acid (8 mL) and finally, the selenium content was determined using coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, NexION®, Perkin Elmer, USA)14.

Approximately 0.2 g of the ground leaf powder was accurately weighed into a Teflon digestion vessel. Then, 8 mL of concentrated nitric acid (HNO₃, 65%) and 2 mL of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂, 30%) were added. The digestion was performed using a microwave digestion system (Milestone, Ethos UP, Italy) with the following temperature program: ramped to 180 °C over 15 min and held for 20 min. After cooling, the digestate was transferred to a 25 mL volumetric flask and diluted to volume with deionized water. A reagent blank was prepared following the same procedure. The analysis was performed using an ICP-MS (NexION® 2000, PerkinElmer, USA) equipped with a SVDV torch, quartz cyclonic spray chamber, and a Meinhard nebulizer. The instrument was operated with the following parameters: RF Power: 1600 W; Plasma Gas Flow: 18 L min⁻1; Auxiliary Gas Flow: 1.8 L min⁻1; Nebulizer Gas Flow: 0.98 L min⁻1; Dwell Time: 100 ms; Acquisition Mode: Spectrum; Isotopes Monitored: ⁷⁷Se, ⁷⁸Se, ⁸2Se. The instrument was calibrated daily using a multi-element standard solution (PerkinElmer Pure Plus) in the range of 0 to 100 µg L⁻1. The correlation coefficient (R2) for the calibration curve was consistently > 0.999. To correct for potential polyatomic interferences, ⁸2Se was used for quantification, and an ORS4 collision/reaction cell with helium (He) gas was used in Kinetic Energy Discrimination (KED) mode.

The quality of the analysis was assured by analyzing a Certified Reference Material, NIST SRM 1547 Peach Leaves (National Institute of Standards and Technology, USA). The measured value for selenium (0.12 ± 0.02 mg kg⁻1) was in good agreement with the certified value (0.12 ± 0.01 mg kg⁻1), yielding a recovery of 100%. The Method Detection Limit (MDL) and Limit of Quantification (LOQ) for selenium, determined by processing 10 reagent blanks through the entire procedure, were 0.05 µg kg⁻1 and 0.15 µg kg⁻1 on a dry weight basis, respectively.

Enzyme assays

Preparation of enzyme extract

After grounding the basil leaves (0.3 g) and suspending them in 3 mL of 25 mM ice-cold Hepes buffer with pH 7.8, containing EDTA (0.2 mM), reduced ascorbate (2 mM), and 2% polyvinylpyrrolidone, the mixture was centrifuged (12,000 rpm-20 min-4 °C) and the supernatant was used for determining the enzyme activity15.

Ascorbate peroxidase (AP) activity

Ascorbate peroxidase (AP) activity was measured according to Nakano and Asada15 method relying on the decrease in absorbance at 290 nm along with the oxidation of ascorbic acid. The reaction mixture (1 mL) contained 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 0.5 mM ascorbic acid, 0.1 mM H₂O₂, and a suitable aliquot (typically 50 µL) of the enzyme extract. The reaction was initiated by adding H₂O₂. The decrease in absorbance at 290 nm was recorded for 3 min. Enzyme activity was calculated and expressed as µmol of ascorbate oxidized per minute per gram of fresh weight (µmol min⁻1 g⁻1 FW). A control was run without the enzyme extract to account for non-enzymatic oxidation.

Assay of superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity

The activity of SOD was measured according to Masayasu and Hiroshi16 method using Tris–Ca–codylic sodium salt buffer (pH 8.2, containing 0.1 mM EDTA). One unit of the enzyme was defined as the quantity needed to inhibit the reduction of NBT by 50% over one minute. The reaction mixture (3 mL) contained 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 8.2), 0.1 mM EDTA, 13 mM L-methionine, 75 µM NBT, 2 µM riboflavin, and an appropriate volume of enzyme extract (typically 20–50 µL). Tubes containing the reaction mixture were illuminated under a fluorescent lamp (30 W) for 15 min. A non-illuminated reaction mixture served as the blank. The absorbance was measured at 560 nm. One unit of SOD activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to cause 50% inhibition of the NBT reduction rate under the assay conditions. SOD activity was expressed as units per gram of fresh weight (U g⁻1 FW).

Element composition

Flame photometry (Model 18, Perkin-Elmer, USA) (for Mg, and potassium), Kjeldahl (for nitrogen), and colorimetry (for phosphate) methods were used to measure different mentioned elements17.

Nitrogen content was determined using the standard micro-Kjeldahl method17. Briefly, 0.5 g of plant powder was digested with concentrated H₂SO₄ in the presence of a catalyst (K₂SO₄:CuSO₄:Se, 100:10:1 w/w/w) until a clear digest was obtained. The digest was then distilled in the presence of 40% NaOH, and the liberated ammonia was trapped in a boric acid solution. The ammonium borate formed was titrated with a standardized 0.01 N H₂SO₄ solution to determine the nitrogen content.

Phosphorus was determined colorimetrically by the vanadomolybdate yellow method17. An aliquot of the same digest prepared for nitrogen analysis was used. The digest was diluted, and then vanadomolybdate reagent was added to form a yellow phosphovanadomolybdate complex. The absorbance was measured at 430 nm using a spectrophotometer. A standard curve was prepared using KH₂PO₄.

Potassium and Mg were measured using a flame photometer (Model 18, Perkin-Elmer, USA) and an atomic absorption spectrophotometer (AAS; Perkin-Elmer, USA), respectively17. For this, 0.5 g of plant powder was dry-ashed in a muffle furnace at 550 °C for 5 h. The ash was dissolved in 2 mL of 2 N HCl, filtered, and made up to a known volume with deionized water. The diluted solution was directly aspirated into the flame photometer for potassium analysis. For Mg analysis, the solution was further diluted and lanthanum chloride was added to a final concentration of 0.1% to prevent interference, before being analyzed by AAS. Standard solutions of potassium and Mg were used for calibration.

Chlorophyll a, b, and carotenoid measurement

After homogenizing and centrifugating (2500 rpm) of basil leaves in acetone (80%) solvent, the absorbance at 647, 663, and 470 nm was measured for chlorophyll b, chlorophyll a, and carotenoid, respectively. The following formula were used to measure the chlorophyll and carotenoid contents18:

Carotenoid content (g g−1) = A × V (mL) × 104/A1%1 cm × P (g) (where A is absorbance, V is the extract volume; P = the weight of sample; A1cm1% = 2592 (β-carotene extinction coefficient in petroleum ether).

Extraction and analyses of leaves essential oils

After cutting fresh leaves from the plants, hydrodistilling the essential oil by a standard Clevenger, and diluting the hydrodistilled essential oil to 0.5% with n-hexane having HPLC-grade, the essential oil was injected into a Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS) system using an Agilent 7890B gas chromatograph equipped with a capillary column (Agilent HP-5MS, 30 m × 0.25 mm, coating thickness 0.25 μm) and a mass detector (Agilent 5977B). The temperature of injector and transfer line was 220 and 240 °C, respectively. The temperature of oven increased from 60 to 240 °C at 3 °C per minute and the carrier gas was helium (with a flow rate of 1 mL min−1). A 1 μl injection was made with a split ratio of 1:2519.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) in SPSS (v21, IBM, Armonk, USA) to assess the effects of selenium, iodine, and their interaction within the 4 × 4 factorial framework. Treatment means were compared using Duncan’s multiple range test (p ≤ 0.05). Assumptions of normality (Shapiro–Wilk test) and homogeneity of variance (Levene’s test) were verified. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three biological replicates. Duncan’s test was chosen for its robustness in handling unequal sample sizes and its common use in agricultural studies for mean separation.

Results and discussion

The selenium and iodine content in the basil leaves

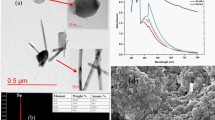

The application of selenium at concentrations ranging from 0 to 3 mg L−1 in the spray treatment of basil leaves increased the concentration of selenium from 12.70 µg kg⁻1 in the control to 17.72 µg kg⁻1 at the highest selenium dose (3 mg L⁻1) (P ≤ 0.05, Fig. 1). The highest selenium dose resulted in a ~ 40% increase in leaf selenium content compared to the control. Concurrently, iodine content rose from 174 µg kgdw−1 in the control to a maximum of 332 µg kgdw−1 with the combined Se₃-I₀.₄ treatment—a 91% increase (P ≤ 0.05). Interestingly, selenium application boosted iodine accumulation, but iodine had no significant effect on selenium uptake.

This indicates that the enrichment of basil leaves with selenium not only boosts its content but also promotes the iodine concentration. Interestingly, this effect was not observed regarding the selenium content in the plant. This implies that combining iodine biofortification with selenium enrichment did not impact the selenium levels in the plant. Consequently, the control sample exhibited the lowest selenium concentration (12.70 µg kg−1), while samples enriched with 3 mg L−1 of selenium showed the highest selenium levels (Se3-I0, Se3-I0.1, Se3-I0.2, and Se3-I0.4 with no significant differences among these samples, P > 0.05). This phenomenon can be explained by selenium’s role in plant redox homeostasis. Selenium, as a constituent of antioxidant enzymes like glutathione peroxidase, can mitigate oxidative stress20,21,22. A reduction in oxidative stress may improve membrane integrity and function in leaf cells, potentially facilitating the absorption and retention of foliar-applied iodine20. In contrast, the lack of a similar effect on selenium uptake by iodine suggests that selenium transport is governed by specific, efficient pathways (e.g., via sulfate transporters) that are not influenced by iodine status21. This unidirectional synergy aligns with findings in carrots, where simultaneous application boosted iodine but not selenium accumulation1,22. The positive effect of selenium in improving the absorption of iodine in the thyroid gland has also been reported. This effect is primarily attributed to selenium’s role in the function of selenoproteins, which are crucial for thyroid hormone metabolism. Thus, selenium aids in the efficient utilization of iodine within the thyroid. A similar effect may exist in the plant, too20.

While iodine biofortification of basil leaves increased the plant’s iodine content, it did not enhance selenium content. This asymmetry suggests selenium improves iodine bioavailability or retention within the leaf, possibly by mitigating oxidative stress at the leaf surface or within the apoplast, thereby improving membrane integrity for iodine uptake or reducing its volatilization [Mechanism 1: Oxidative stress mitigation]. In contrast, iodine likely lacks a specific role in the transport pathways utilized by selenate, explaining its null effect on selenium accumulation [Mechanism 2: Transport specificity]21. This finding aligns with studies in carrots, where simultaneous application boosted iodine but not selenium content1, and underscores the importance of element-specific transport mechanisms in biofortification strategies. Tangjaidee, et al.22 observed that the simultaneous application of iodine and selenium led to a significant increase in iodine levels within plant tissues, whereas selenium accumulation was less pronounced. This suggests a more intricate mechanism that may restrict selenium uptake despite the successful enrichment of iodine. Moldovan, et al.23 also reported similar findings. Lyons24 emphasized that foliar application of selenium and iodine in cereals including wheat, rice, and maize was very efficient for biofortifying these plants. Smoleń, et al.1 indicated that carrots biofortified with iodine and selenium exhibited increased nutrient content without negatively impacting their overall quality. The study found that consuming 100 g of these biofortified carrots could significantly cover the recommended daily intake for both iodine and selenium.

Biochemical evaluations of basil leaves

The application of iodine and selenium significantly influenced the activity levels of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and ascorbate peroxidase (AP) in basil leaves (P ≤ 0.05, Fig. 2). The activities of these enzymes increased with the application of iodine and selenium as well as with their concentration (P ≤ 0.05). The Se3-I0.4 treatment induced the most substantial increases, boosting SOD and AP activities by approximately 43% and 40%, respectively, over the control (P ≤ 0.05).

Superoxide dismutase is an essential enzyme that catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide radicals into hydrogen peroxide and molecular oxygen, thereby mitigating oxidative stress in cells. Oxidative stress arises from an imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the antioxidant defense capacity of the cell. In plants, ROS can be generated from various sources, including photosynthesis, respiration, and exposure to environmental stressors such as drought, salinity, and pathogens. The accumulation of ROS can lead to cellular damage, impaired photosynthetic efficiency, and ultimately, reduced crop yield. Therefore, enhancing SOD activity through biofortification can be a viable strategy to improve plant resilience against oxidative stress25.

Ascorbate peroxidase, another key enzyme in the plant antioxidant system, plays a vital role in detoxifying hydrogen peroxide, a byproduct of SOD activity. Ascorbate peroxidase utilizes ascorbate as a substrate to convert hydrogen peroxide into water, thereby preventing oxidative damage to cellular components. The interplay between SOD and AP is crucial for maintaining cellular redox homeostasis. Enhanced activity of these enzymes through biofortification can lead to a synergistic effect, resulting in improved overall antioxidant capacity in plants26.

This synergistic boost in antioxidant capacity can be explained by the distinct but complementary roles of selenium and iodine in plant redox biology. Selenium is incorporated into selenoproteins, such as glutathione peroxidase, which are highly efficient at scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS) like hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) and lipid hydroperoxides25. By mitigating overall oxidative stress, selenium likely prevents the inhibition of SOD and APX enzymes, allowing their activity to remain high. Furthermore, selenium application can trigger a mild “eustress” signal, upregulating the expression of genes encoding for these key antioxidant enzymes25,26.

Iodine, while not a cofactor for antioxidant enzymes like selenium, appears to modulate the plant’s stress signaling network. Iodine can influence phytohormone pathways involved in stress responses, such as those for auxins and abscisic acid. This hormonal modulation can, in turn, activate the transcription of genes for SOD and APX, preparing the plant’s defense system27,28.

The observed synergy in the Se3-I0.4 treatment likely arises from this complementary action that selenium directly quenches ROS and may upregulate enzyme expression, while iodine primes the plant’s defense system through hormonal signaling. This coordinated response results in a more robust antioxidant system than either element could induce alone, protecting cellular components from oxidative damage and contributing to the improved physiological performance observed in biofortified basil27,29.

Ahmad, et al.28 demonstrated that selenium biofortification enhanced crop plants’ defense mechanisms against oxidative stress by boosting the activity of enzymes such as CAT, AP, GPX, and SOD. Similarly, studies conducted by Lima, et al.29 and Sularz, et al.30 showed that iodine biofortification in soybean and lettuce resulted in increased activity of major antioxidant enzymes, including catalase, AP, and SOD.

Composition of P, Mg, N, and K

The foliar application of selenium and iodine also enhanced the macronutrient content of basil leaves. The concentrations of P, Mg, N, and K increased proportionally with the application levels of both elements (Fig. 3a–d). The optimal treatment, Se3-I0.4, increased the contents of P, Mg, N, and K by approximately 25%, 20%, 18%, and 22%, respectively, compared to the control (P ≤ 0.05). This improvement is likely an indirect effect of enhanced plant vigor and metabolic activity25.

Iodine and selenium are known to play significant roles in enhancing plant physiological processes. Iodine has been shown to improve photosynthesis, increase chlorophyll content, and enhance the overall growth rate of plants. These improvements can lead to enhanced root development, which is critical for the efficient uptake of essential nutrients, including P, Mg, K, and N4. Selenium, on the other hand, acts as an antioxidant and contributes to the regulation of various physiological processes within plants. It has been demonstrated that selenium promotes the development of root hairs, which are essential for nutrient absorption. The increased root surface area allows for greater contact with the soil and subsequently improves the uptake of macronutrients. Moreover, selenium can stimulate the activity of various enzymes involved in nutrient assimilation, further enhancing the plant’s ability to absorb and utilize these essential elements7. Moreover, the presence of iodine and selenium can modulate the synthesis of plant hormones, such as auxins and cytokinins, which are critical for root development and nutrient uptake. These hormones can influence the plant’s ability to absorb macronutrients by enhancing root growth and increasing the efficiency of nutrient transport mechanisms. It has been reported that the enhanced uptake of micronutrients due to biofortification can lead to improved plant metabolism and growth, which in turn can create a positive feedback loop, promoting further nutrient uptake31. Golubkina, et al.20 studies on potatoes showed an increase in potassium content when selenium and iodine were applied together with salicylic acid. However, the joint application of selenium and iodine had no significant impact on elemental composition but effectively increased Se and I concentrations in the carrot roots32. Research conducted by Duborska, et al.32 showed that the foliar application of selenate had a beneficial effect on the uptake of Ca, Mg, and K in crops. Additionally, Bialowas, et al.33 reported favorable outcomes when selenium and iodine were applied together, resulting in enhanced levels of S, Ca, K, P, and Mg.

Carotenoid, chlorophyll a, and chlorophyll b content

Biofortification significantly increased photosynthetic pigment concentrations26. Carotenoid content rose dramatically from 21.4 mg g⁻1 in the control to 63.2 mg g⁻1 in the Se₃-I₀.₄ treatment (Fig. 4a). Similarly, chlorophyll a increased from 4.40 to 6.18 mg g⁻1, and chlorophyll b from 2.17 to 3.10 mg g⁻1 (Fig. 4b).

The observed boost in carotenoid synthesis following selenium and iodine enrichment suggests a positive correlation between plant selenium/iodine levels and carotenoid content. Carotenoids have antioxidant properties related to the conjugated double bonds in their structure. It seems that the biofortification process activates genes that are key for making enzymes like dihydroflavonol reductase, chalcone synthase, and phenylalanine ammonia-lyase, leading to higher production of carotenoids and other pigments34. Golob, et al.35 reported that applying selenium (Se) can positively affect total chlorophyll and carotenoid levels in plants. Ramezani, et al.36 declared that under blue light conditions, higher carotenoid amounts were associated with iodine and selenium fortification.

The increase in chlorophyll content indicates improved photosynthetic health, leading to better growth. The underlying mechanism may involve selenium and iodine’s role in nutrient uptake; for instance, the increased nitrogen and magnesium content is crucial for chlorophyll synthesis. Additionally, the general reduction in oxidative stress protects chloroplasts from damage, preserving and potentially enhancing chlorophyll synthesis and stability. Meanwhile, the antioxidant activity of selenium leads to reduced oxidative stress caused by environmental factors. This helps protect chloroplasts, where chlorophyll is synthesized, leading to increased chlorophyll stability and content. Biofortification with selenium and iodine can trigger stress response mechanisms in plants. In response, plants may increase chlorophyll production as part of their adaptive strategy to optimize photosynthesis under stress conditions. Ramezani, et al.36 reported that total chlorophyll values of lettuce and broccoli increased via selenium application. However, Golubkina, et al.20 observed a decrease in chlorophyll a due to the combined application of iodine and selenium in B. juncea.

Basil leaves essential oils analyses

Linalool and 1,8-cineole were the most abundant compounds in basil leaf essential oil (Table 4) which are classified as oxygenated monoterpenes. The biofortification protocol notably altered the essential oil profile, enhancing its sensory quality. Linalool, increased by ~ 58% in the Se3-I0.4 treatment compared to the control. Conversely, the concentrations of 1,8-cineole (camphoraceous) and eugenol (pungent, clove-like) decreased significantly by approximately 44% and 63%, respectively, in the optimal Se₃-I₀.₄ treatment compared to the control. The effect of selenium on shifting this profile was more pronounced than that of iodine.

Linalool is a key compound responsible for the characteristic sweet, floral, and slightly citrusy aroma of basil. An increase in linalool enhances the fresh, pleasant, and desirable fragrance and flavor notes, making the basil more appealing for culinary and aromatic uses. In contrast, 1,8-cineole imparts a sharp, camphoraceous, and slightly medicinal scent, while eugenol is associated with spicy, clove-like, and somewhat pungent notes37. This shift from pungent/spicy notes toward a sweeter, more floral aroma significantly improves the basil’s desirability for culinary use. The alteration in monoterpene and phenylpropanoid pathways indicates that selenium and iodine profoundly influence secondary metabolism. The specific mechanisms may involve the modulation of enzyme activities or gene expression related to the biosynthesis of these volatile compounds, steering metabolic flux toward linalool and away from 1,8-cineole and eugenol38.

These changes also point to a fundamental re-direction of secondary metabolic pathways. We hypothesize that the selenium-iodine-induced oxidative eustress acts as a signal that shunts metabolic precursors away from the phenylpropanoid pathway (which produces eugenol) and toward the methylerythritol phosphate pathway, which leads to linalool synthesis. Selenium’s role in altering the expression of genes involved in terpenoid biosynthesis could be a key driver of this shift37. From a sensory perspective, this means the biofortified basil possesses a refined aroma profile, with enhanced sweet and floral characteristics and reduced pungent and medicinal notes, increasing its potential value as a culinary ingredient.

Limonene, α-pinene, and methyl chavicol were other compounds found in basil leaf essential oil that increased with selenium and iodine concentration, while no significant change was observed in β-pinene and camphor concentration and an increase in 3-carene and β-phellandrene occurred with selenium and iodine concentration. This suggested that selenium and iodine concentration, especially selenium concentration, are supposed to be major issues able to alter the composition of the essential oils in the basil plant. This result showed that the biofortification protocol can significantly influence the typical overall plant aroma.

Overview of selenium × iodine Interactions

Selenium and iodine interactions in plant biofortification are of growing interest due to their potential to enhance both plant nutritional quality and human health. In our study, the factorial design allowed for a detailed assessment of how these two micronutrients interact when applied together to basil (Ocimum basilicum L.), with a focus on their effects on mineral accumulation, antioxidant enzyme activity, pigment synthesis, and essential oil composition. The key findings on selenium × iodine interactions were: 1) Synergistic effects on nutrient accumulation: The combined application of selenium and iodine led to a significant increase in leaf iodine content, especially at higher selenium concentrations. This suggests a synergistic effect, where selenium facilitates the uptake or retention of iodine in basil leaves. However, the reverse was not observed (iodine application did not significantly affect selenium accumulation in the plant). Meanwhile, no antagonism was detected. Unlike some reports in other species, where simultaneous application can reduce selenium or iodine uptake, our results indicate that in basil, selenium and iodine do not antagonize each other’s accumulation at the tested concentrations; 2) Synergistic enhancement of antioxidant enzyme activities: The highest activities of these key antioxidant enzymes were observed in treatments with both high selenium and iodine. This indicates a synergistic interaction, where the combined presence of both elements amplifies the plant’s antioxidant defense system beyond what is achieved by either element alone. Meanwhile, selenium is a cofactor for selenoproteins involved in redox regulation, while iodine can modulate redox signaling and phytohormone levels. Their combined application likely triggers overlapping and complementary pathways that boost antioxidant capacity (mechanistic insights); 3) Impact on pigment and essential oil composition: The selenium × iodine interaction significantly increased chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and carotenoid content. This suggests that the combined biofortification not only improves nutritional value but may also enhance photosynthetic efficiency and stress tolerance.

Regarding the essential oil profile, the interaction led to increased linalool (a desirable aroma compound) and decreased 1,8-cineole and eugenol. The effect was more pronounced with higher seleniumconcentrations, but the presence of iodine further modulated these changes, indicating a complex interaction affecting secondary metabolism; 4) Statistical evidence of interaction: Statistical analysis (two-way ANOVA) revealed significant selenium × iodine interactions (p < 0.05) for several traits, including chlorophyll a, SOD activity, and linalool content. This confirms that the effects of selenium and iodine are not merely additive but interact in a way that produces unique outcomes when both are present.

Therefore, the 4 × 4 factorial approach demonstrated that the interactions between selenium and iodine in basil biofortification are predominantly synergistic, enhancing nutrient accumulation, antioxidant defense, pigment synthesis, and essential oil quality. These findings support the use of combined selenium and iodine biofortification as a promising strategy to improve both plant and human nutrition, with additional benefits for crop quality and resilience.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrates that the combined foliar biofortification of basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) with selenium and iodine is a highly effective strategy for enhancing its nutritional and biochemical quality. Our findings confirm the initial hypothesis that the two elements act synergistically, leading to a significant enhancement in the accumulation of iodine and a marked improvement in the plant’s antioxidant capacity and essential oil profile, surpassing the effects of their individual applications. The most effective treatment, Se3-I0.4, resulted in a 91% increase in leaf iodine content compared to the control. This synergistic effect on iodine uptake, facilitated by selenium, is a key physiological insight, potentially linked to selenium’s role in improving redox homeostasis and membrane integrity. Furthermore, this optimal treatment significantly boosted the activity of key antioxidant enzymes, SOD and AP, and increased the concentrations of essential pigments (chlorophyll a, b, and carotenoids) and macronutrients (phosphorus, magnesium, potassium, and nitrogen). These results provide a clearer physiological explanation, linking the improved antioxidant defense system to enhanced photosynthetic efficiency and overall plant vigor. A notable finding was the significant alteration of the essential oil composition, where the combined biofortification increased the concentration of the desirable compound linalool by ~ 58% while reducing the levels of 1,8-cineole and eugenol. This shift not only improves the aromatic quality of basil but also underscores the profound influence of selenium and iodine on secondary metabolism. In conclusion, the synergistic interaction between selenium and iodine identified in this work provides a robust, multi-faceted biofortification protocol. This approach successfully enhances the micronutrient density, antioxidant properties, and sensory quality of basil, offering a promising model for improving the nutritional value of culinary herbs and contributing to the addressing of global dietary deficiencies in these essential elements. Future research should focus on field-scale validation of this protocol, assess the bioavailability of the accumulated selenium and iodine in human trials, and explore the molecular mechanisms underlying their synergistic interaction in plants.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Smoleń, S., Baranski, R., Ledwożyw-Smoleń, I., Skoczylas, Ł & Sady, W. Combined biofortification of carrot with iodine and selenium. Food Chem. 300, 125202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125202 (2019).

Golubkina, N., Kekina, H. & Caruso, G. Yield, quality and antioxidant properties of indian mustard (Brassica juncea L.) in response to foliar biofortification with selenium and iodine. Plants 7, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants7040080 (2018).

Medrano-Macías, J., Leija-Martínez, P., González-Morales, S., Juárez-Maldonado, A. & Benavides-Mendoza, A. Use of iodine to biofortify and promote growth and stress tolerance in crops. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.01146 (2016).

Izydorczyk, G. et al. Biofortification of edible plants with selenium and iodine—A systematic literature review. Sci. Total Environ. 754, 141983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141983 (2021).

Germ, M. et al. Biofortification of common buckwheat microgreens and seeds with different forms of selenium and iodine. J. Sci. Food Agric. 99, 4353–4362. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.9669 (2019).

de Lima Gomes, F. T. et al. Agronomic biofortification with selenium and zinc in tomato plants (Solanum lycopersicum L.) and their effects on nutrient content and crop production. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutri. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42729-025-02281-7 (2025).

Eslamiparvar, A., Hosseinifarahi, M., Amiri, S. & Radi, M. Combined bio fortification of spinach plant through foliar spraying with iodine and selenium elements. Sci. Rep. 15, 6722 (2025).

Mao, H. et al. Using agronomic biofortification to boost zinc, selenium, and iodine concentrations of food crops grown on the loess plateau in China. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutri. 14, 459–470 (2014).

Germ, M. et al. The effect of different compounds of selenium and iodine on selected biochemical and physiological characteristics in common buckwheat and pumpkin sprouts. Acta Biol. Slov. 58, 35–44 (2015).

Germ, M. et al. Fagopyrin and rutin concentration in seeds of common buckwheat plants treated with Se and I/Vsebnost fagopirina in rutina v semenih navadne ajde tretirane s selenom in jodom. Folia Biol. Geol. 58, 45–51 (2017).

Landini, M., Gonzali, S. & Perata, P. Iodine biofortification in tomato. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 174, 480–486 (2011).

Smoleń, S. et al. Iodine and selenium biofortification with additional application of salicylic acid affects yield, selected molecular parameters and chemical composition of lettuce plants (Lactuca sativa L. var. capitata). Front Plant Sci 7, 1553. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.01553 (2016).

Puccinelli, M., Landi, M., Maggini, R., Pardossi, A. & Incrocci, L. Iodine biofortification of sweet basil and lettuce grown in two hydroponic systems. Sci. Hortic. 276, 109783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109783 (2021).

Montes-Bayón, M., Molet, M. J. D., González, E. B. & Sanz-Medel, A. Evaluation of different sample extraction strategies for selenium determination in selenium-enriched plants (Allium sativum and Brassica juncea) and Se speciation by HPLC-ICP-MS. Talanta 68, 1287–1293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2005.07.040 (2006).

Nakano, Y. & Asada, K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physio. 22, 867–880. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a076232 (1981).

Masayasu, M. & Hiroshi, Y. A simplified assay method of superoxide dismutase activity for clinical use. Clin. Chim. Acta 92, 337–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-8981(79)90211-0 (1979).

Chapman, H. D. & Pratt, P. F. Methods of Analysis for Soils, Plants and Waters. . 60–61, 150–179. (University of California, Los Angeles, 1961).

Porra, R. J., Thompson, W. A. & Kriedemann, P. E. Determination of accurate extinction coefficients and simultaneous equations for assaying chlorophylls a and b extracted with four different solvents: Verification of the concentration of chlorophyll standards by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 975, 384–394 (1989).

Kiferle, C. et al. Effect of Iodine treatments on Ocimum basilicum L.: Biofortification, phenolics production and essential oil composition. PLoS ONE 14, e0226559 (2019).

Golubkina, N. et al. Joint biofortification of plants with selenium and iodine: new field of discoveries. Plant 10, 1352 (2021).

Puccinelli, M., Malorgio, F., Pintimalli, L., Rosellini, I. & Pezzarossa, B. Biofortification of lettuce and basil seedlings to produce selenium enriched leafy vegetables. Horticulturae 8, 801 (2022).

Tangjaidee, P., Swedlund, P., Xiang, J., Yin, H. & Quek, S. Y. Selenium-enriched plant foods: Selenium accumulation, speciation, and health functionality. Front. Nutri. 9, 962312 (2023).

Moldovan, A., Kharchenko, V., Golubkina, N., Kekina, E. D. & Caruso, G. Foliar biofortification of chervil with selenium and iodine under silicon containing fertilizer supply. Veg. Crop Russia 2, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.18619/2072-9146-2022-2-57-64 (2022).

Lyons, G. Biofortification of cereals with foliar selenium and iodine could reduce hypothyroidism. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 730 (2018).

de Oliveira, V. C. et al. Physiological and physicochemical responses of potato to selenium biofortification in tropical soil. Potato Res. 62, 315–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11540-019-9413-8 (2019).

Blasco, B. et al. Does iodine biofortification affect oxidative metabolism in lettuce plants?. Biol. Trace Element Res. 142, 831–842. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-010-8816-9 (2011).

Mittler, R. Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 7, 405–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1360-1385(02)02312-9 (2002).

Ahmad, R., Waraich, E. A., Nawaz, F., Ashraf, M. Y. & Khalid, M. Selenium (Se) improves drought tolerance in crop plants-a myth or fact?. J. Sci. Food Agric. 96, 372–380. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.7231 (2016).

Lima, J. D. S. et al. Soybean plants exposed to low concentrations of potassium iodide have better tolerance to water deficit through the antioxidant enzymatic system and photosynthesis modulation. Plant 12, 2555 (2023).

Sularz, O. et al. Anti-and pro-oxidant potential of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) biofortified with iodine by KIO 3, 5-iodo-and 3, 5-diiodosalicylic acid in human gastrointestinal cancer cell lines. RSC Adv. 11, 27547–27560 (2021).

Szerement, J., Szatanik-Kloc, A., Mokrzycki, J. & Mierzwa-Hersztek, M. Agronomic biofortification with Se, Zn, and Fe: An effective strategy to enhance crop nutritional quality and stress defense—A review. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutri. 22, 1129–1159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42729-021-00719-2 (2022).

Duborska, E., Sebesta, M., Matulova, M., Zverina, O. & Urik, M. Current strategies for selenium and iodine biofortification in crop plants. Nutrient 14, 4717. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14224717 (2022).

Bialowas, W., Blicharska, E. & Drabik, K. Biofortification of plant- and animal-based foods in limiting the problem of microelement deficiencies-A narrative review. Nutrient https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16101481 (2024).

Golubkina, N. A. et al. Comparative evaluation of spinach biofortification with selenium nanoparticles and ionic forms of the element. Nanotech Russia 12, 569–576. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1995078017050032 (2017).

Golob, A. et al. Biofortification with selenium and iodine changes morphological properties of Brassica oleracea L. var. gongylodes) and increases their contents in tubers. Plant Physio. Biochem. 150, 234–243 (2020).

Ramezani, S. et al. Selenium and iodine biofortification interacting with supplementary blue light to enhance the growth characteristics, pigments, trigonelline and seed yield of Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-gracum L.). Agron 13, 2070 (2023).

Grayer, R. J. et al. Infraspecific taxonomy and essential oil chemotypes in sweet basil Ocimum basilicum. Phytochemistry 43, 1033–1039. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9422(96)00429-3 (1996).

Koba, K., Poutouli, P., Raynaud, C., Chaumont, J.-P. & Sanda, K. Chemical composition and antimicrobial properties of different basil essential oils chemotypes from Togo. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. 4, 1–8 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was a part of a Ph.D. research project carried out at Islamic Azad University Yasuj Branch, Iran.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Rahman Farzadi : Investigation and experiment, Mehdi Hosseinifarahi, Supervision, Conceptualization; Bijan Kavoosi: Methodology; Mohsen Radi: Validation; Moslem Abdipour, Software, Formal analysis; Sedegheh Mohammadi, Review and edit. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All authors have read, approved the manuscript and provided their consent for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Farzadifar, R., Hosseinifarahi, M., Kavoosi, B. et al. Effects of iodine and selenium biofortification on Ocimum basilicum L. nutritional quality. Sci Rep 16, 1541 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31412-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31412-4