Abstract

“Assistive technology’’ (hereinafter AT) refers to equipment, products, and software designed or adapted to assist individuals to perform a specific task they might otherwise find difficult. AT is gradually becoming a fundamental human right across the globe. This is reinforced in international frameworks such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. However, the lack of empirical data on the prevalence and usage of AT in Ghana poses a significant barrier for policymakers to develop mainstream interventions for disability. The study used a quantitative cross-sectional survey design to examine the prevalence of AT and barriers to its use among 189 persons with mobility and visual impairments in four selected districts in the Ashanti region. The results indicated a relatively high AT utilisation rate of 66% among urban dwellers with disabilities. AT use is lower among women compared to men, with respective utilisation rates of 43.4% and 56.6%. About half of the mobility-impaired participants (50.4%) and 44% of the visually impaired participants identified high device costs as a major barrier. Difficulties in device use (21%) and stigma associated with AT (23.8%) further limited effective adoption. The study underscores the importance of enhancing the equitable distribution of assistive technologies in Ghana.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Disability is an evolving phenomenon, and it exists in every race, ethnicity, gender, age, and religion1. The patterns of disability are constantly influenced by trends in health conditions and contextual factors such as natural disasters, diet, traffic-related accidents, conflict, and substance abuse2. Globally, it is estimated that 1.3 billion people, representing 16% of the global population, suffer from disabilities, of which a good number, between 110 and 190 million, experience very significant difficulties in their day-to-day lives3,4. About 80% of the global disabled population is from developing countries. This is far higher than the global prevalence. The prevalence of disability is gradually increasing due to an increase in long-term illnesses and the ageing population. Many persons with disabilities or impairments depend on assistive technologies and devices to carry out their daily activities and participate fully in the community4.

‘’Assistive technology’’ (hereinafter AT) refers to equipment, products, and software designed or adapted to assist individuals to perform a specific task they might otherwise find difficult5. It helps compensate for a decline in functionality, improving persons with disabilities’ integration and their quality of life6,7. AT devices or products include wheelchairs, crutches, prosthetics, orthotics, eyeglasses, hearing aids, computer software, etc. These devices benefit a wide range of people, such as mobility-impaired and sensory-impaired individuals8. Without the devices, persons with disabilities would have remained unproductive and would depend solely on their caregivers9.

The global demand for AT is also growing gradually, driven by demographic shifts such as population ageing, an increasing prevalence of chronic health conditions, and disability-related functional limitations10. It is estimated that over 2.5 billion people worldwide need at least one form of AT; however, nearly one billion people, mainly from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), lack access to these essential products and services10,11,12. Recognising this challenge, the World Health Organisation (WHO) launched the Global Cooperation on Assistive Technology (GATE) initiative to enhance national capacity, service provision, and innovation ecosystems for AT13. Moreover, within the framework of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), AT is regarded as a key environmental facilitator that improves functioning and participation14. However, barriers such as limited availability of AT, affordability issues, stigma, policy gaps, and inadequate service delivery systems hinder access, particularly among persons with mobility and visual impairments15,16,17.

Additionally, within the last decade, large-scale surveys such as the WHO rapid Assistive Technology Assessment (rATA) have been conducted across thirty-five countries and have provided population-level data on AT needs and access. Findings consistently show low coverage rates, particularly for mobility, vision, and hearing-related technologies, with unmet needs exceeding about 50% in LMICs6,18,19.

Although the availability and use of AT are generally higher in high-income countries, some gaps exist. For instance, Berardi et al.20 used data from the 2012 Canadian survey on disability to describe the current use and unmet needs of AT among community-dwellers with activity limitation and participation restriction. The results showed that about 95% of the participants use AT such as vision aids, mobility aids, communication aids, a cane, crutches, and walking sticks, among other devices. Despite the high reported use of AT, the study reported 27% of unmet needs, particularly for hearing aids and bathroom supports. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, findings from the WHO’s rATA revealed that about 63% of persons with disabilities (PWDs) use mobility aids, hearing aids and other assistive products. This study also recorded 18.5% prevalence of unmet needs for AT, which rose to 37.5% among older adults due to financial constraints and systemic barriers7. Other studies also echoed that the majority of PWDs (mobility and visually impaired) in these advanced countries are very satisfied with their AT use; however, affordability remains a great challenge21,22,23.

The situation is not different in Sub-Saharan Africa. Access to AT remains profoundly inadequate. Only 5–25% of PWDs reportedly receive the necessary assistive products they need (24,18,17]. Common AT includes walking sticks, wheelchairs, crutches, spectacles, and magnifying glasses24. Numerous studies across LMICs have highlighted diverse patterns of AT use, alongside significant rates of abandonment, often attributed to financial barriers, stigma and poor alignment between devices and users’ functional needs15,17,25,26.

Furthermore, demographic factors such as age, sex, educational level, employment status, and socioeconomic background play a crucial role in shaping patterns of AT utilisation. Women with disabilities often face compounded barriers, leading to higher unmet AT needs compared to men26. For example, Kaye27, using a population-based survey to examine disparities in AT use among PWDs in California, reported that women were more likely to use AT than men. Conversely, in Italy, Desideri et al.28 found no gender-based differences in AT use but identified a strong link between the type of disability and AT adoption. Within the African context, evidence on AT access and utilisation shows nuanced patterns. For instance, Jamali-Phiri et al.25 reported significant unmet needs among children with disabilities in urban Malawi. However, other studies observed no significant connection between area of residence and overall AT use19. Visagie and colleagues further noted that specific types of AT varied according to both gender and setting. Mobility aids such as walking sticks were more often used by men in rural areas, while visual aids were predominantly used by women in urban environments. These contrasting findings may reflect contextual differences influenced by geographic, cultural, and socioeconomic factors.

There is limited empirical data on the number of persons with disabilities who lack access to specific AT in Ghana; however, data from the Ghana Statistical Service29 suggests that over 2.4 million, representing 8% of the country’s population, had some form of disability in 2021 as compared to 3% in 2010. The increase in the prevalence of disability in Ghana suggests a high demand for AT and devices, and it confirms the WHO’s prediction that the global demand for AT will increase significantly by 2050. AT is very important in the lives of individuals with disabilities and therefore should be readily available for persons with disabilities (PWDs) to enhance their participation and social inclusion, if the vision of the 2030 agenda of ‘leaving no one behind’ still holds. That notwithstanding, Ghana has made strides in committing to some international and local disability inclusion frameworks and policies. One such framework is the United Nations Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD). Article 20 and Article 26 of the UNCRPD mandate State Parties to ensure the affordability and accessibility of AT and devices to all users1. Moreover, Sect. 31 of the Ghana Disability Act (Act 715) seeks to provide free medical care and assistive devices for individuals with disabilities. Despite these legal provisions, the utilisation of AT and devices remains relatively low in Ghana30.

More so, existing evidence, primarily qualitative, has predominantly focused on children and students with mobility and visual impairments. These studies have identified critical barriers to AT access, including stigma, financial constraints, systemic neglect, limited device availability, and inadequate institutional adaptation16,31,32,33. However, there remains a significant research gap regarding the experiences of adults with disabilities, particularly in urban community settings. The current study aimed to address these gaps by conducting a quantitative cross-sectional survey to investigate the prevalence of AT utilisation, associated barriers, and potential strategies for improving access among adults with mobility and visual impairments in urban districts of the Ashanti region in Ghana.

The study’s contribution to the literature

The study makes a unique contribution to AT literature by addressing significant methodological, demographic, and geographic gaps. Existing empirical studies in Ghana have focused largely on children and students with disabilities, often in institutional settings, using qualitative approaches16,31,33. Very little is known about community-dwelling adults, particularly in urban settings, despite evidence that AT coverage in low-resource contexts can fall below even the minimal functional thresholds10,19. Evidence suggests that urban dwellers with disabilities have high unmet AT needs26, and they are an underexplored demographic and geographic group in the Ashanti region.

The use of quantitative cross-sectional surveys moves beyond the predominantly qualitative and institution-based studies in Ghana to provide population-level data on AT prevalence, utilisation and barriers. This evidence will help inform policy alignment with WHO’s GATE priority and national disability and rehabilitation planning10,13. The study therefore provides actionable evidence to guide urban service delivery, financing strategies, and user-centred AT provision in the Ashanti region.

What is new about the study

This study represents the first multi-district quantitative investigation of AT access, use and barriers regarding their use among adults with mobility and visual impairments in urban communities within the Ashanti region of Ghana. Again, the current study offers a broader and more generalisable understanding of the challenges faced by adults with disabilities in accessing AT. Moreover, the study provides a more comprehensive estimate of the prevalence and barriers to AT use in urban Ghana, and it generates valuable baseline data on AT use that is tailored to the specific context, offering critical insights for evidence-based planning and intervention.

Methods

Participants and data collection

The study used a cross-sectional survey design to conduct a quantitative study in four urban districts in the Ashanti Region of Ghana. The four urban districts were Kumasi Metro, Asokwa, Oforikrom and Ejisu Municipalities. These were selected based on Ghana’s 2021 Population and Housing Census report, which puts the Ashanti Region as the region with the highest number of persons with disabilities, with these municipalities leading with the numbers. The respondents were selected using simple random sampling. The respondents were selected during their monthly union meetings. At each of their meetings, members present were assigned random numbers, and the numbers were put in a container and shuffled and randomly selected. The person whose corresponding number was selected was included in the study. This gave each person an equal chance of being selected to take part in the study. A structured questionnaire was used for the data collection. The inclusion criteria for selection were that the person should either have visual impairment or physical impairment, must be a registered member of the disability association and be 18 years of age or more and was required to be present at their meetings at the time of selection to take part in the study. A total of 210 persons with mobility and visual disabilities were selected using a simple random sampling technique. Out of this number, 189 participants completed the study. The sample size was calculated using the Yamane Formula with an estimated population of 1321, with a margin of error of 6.73% (0.0673).

N = 1321/1 + 1321*(0.0672)2

n = 189

The Sample size of 189 was used for the study.

Instrumentation and analysis

A structured questionnaire was developed by the team based on the study objectives and was pretested at the Bosomtwe district, which is a peri-urban district and shares almost the same features as the selected districts. Questions that were not clear during the pretest were revised and restructured to ensure reliability and validity. The questionnaire was administered by field data collectors who were trained on the specific questions contained in the questionnaire. Both self-administered and interviewer-administered techniques were adopted during data collection. For those who could read and write, they are made to do self-administration, while those who had difficulty in fully comprehending the questions independently were assisted by the field data collectors. The instrument was divided into two parts. The first part contained the respondents’ personal information, while the second part consisted of information on existing assistive devices, their frequency of use, and their effects, as measured using a 4-point Likert scale. A higher score indicated a higher usage of a particular assistive technology and device. The data were analysed using descriptive statistical tools in the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 27. The researchers initially developed a coding manual, after which the data were first coded into SPSS and cleaned for entry errors. Frequency distributions and percentages were used to analyse the data, and the results have been presented in frequency tables.

Ethical issues

The study obtained ethical approval from the Committee on Human Research Publication and Ethics (CHRPE) at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology with approval number CHRPE/AP/551/25, and the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki were followed. Prior to the data collection, all the participants were informed about the purpose, potential risks, and benefits of the study. Informed consent was obtained from all the respondents, with full respect for their autonomy, including their right to withdraw from the study at any time without consequences. The respondents were assured of the confidentiality of all information obtained, their privacy, and anonymity during the data collection, storage, and publication of the study materials.

Results

A total of 210 individuals with mobility and visual impairments were approached for recruitment. Of these, 21 were excluded: 8 did meet the inclusion criteria and 13 declined to participate for several reasons. Individuals who declined were similar to participants in terms of age and sex, suggesting that the final sample of 189 respondents is broadly representative of the target population. The flow of participant selection throughout the study is illustrated below (Fig. 1).

Table 1 below shows the demographic variables of the participants.

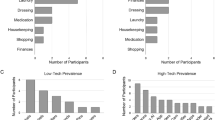

Existing assistive technology and factors associated with usage

The results suggest that the existing assistive technologies include white canes, smartphones, magnifiers, computers, and eyeglasses for the visually impaired, as well as callipers, crutches, wheelchairs, walking sticks, and prostheses for the mobility-impaired. The prevalence of assistive device usage was approximately 66%. The use of assistive devices among males was 55%, indicating that males were more likely to be exposed to the device than females. The usage of AT among mobility-impaired and visually impaired individuals with tertiary education was high (21.9% for mobility-impaired and 31% for visually impaired individuals) compared to those with primary or basic school qualifications (5.7% and 1.2% for mobility-impaired and visually impaired, respectively). As for employment status, the usage of assistive devices was higher among those who were employed (59% for mobility-impaired and 39.3% for visually impaired) than among unemployed participants. See Table 2 below for details.

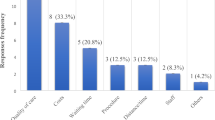

Barriers to the utilisation of assistive technology among respondents

A significant proportion of participants (91.4% of mobility-impaired and 87.9% of visually impaired) reported encountering barriers in using assistive technology and devices, while only a handful reported experiencing none. The predominant barrier to the use of AT was the high cost of devices, which was reported by 50% of mobility-impaired individuals and 46.5% of the visually impaired. Additionally, 20.9% of the mobility-impaired cited difficulty in using the devices, while 23.3% of the visually impaired individuals identified stigma associated with AT use as a deterrent. The participants highlighted the need for financial support and user training as key strategies to address the barriers. See Table 3 below for the details.

Discussion

The study examined the prevalence of assistive technology (AT) and device use as well as barriers to their use, among persons with mobility and visual impairments in some selected urban districts in the Ashanti region of Ghana. The study revealed a relatively high prevalence rate of 66% of AT usage, indicating that approximately two-thirds of the respondents were actively using some form of AT. This suggests a positive trend in AT availability and uptake in urban Ghana, specifically in the Ashanti region and may reflect a growing awareness, accessibility improvements, or better urban healthcare infrastructure. Compared to earlier studies in Ghana, this prevalence is notably higher. For instance, Osam et al.16 employed a qualitative approach to explore parents’ perceptions of their children’s use of assistive technology (AT) and found that the availability of the devices was a significant challenge. Similarly, Osei and Osei31 reported that AT were often mismatched with the specific needs of visually impaired students, which limited effective use. These prior studies used qualitative approaches and focused predominantly on children and students in institutional settings, where AT access may be more constrained or context-specific. Besides, the differences could also be attributed to the sample size and the study approaches. In contrast, the current study provides a broader community-based estimate among adults, filling a critical national gap.

Again, the WHO’s global estimates suggest that about 10% of people in need of AT in LMICs have access to it13, indicating that Ghana’s urban areas may be making better progress relative to global averages. The higher prevalence of AT use in urban Ghana may be partly attributed to the presence of active disability networks, non-governmental organisations, and donor-funded projects within urban centres, which enhance awareness, distribution, and training related to AT use24. These organisations frequently run urban-centred programmes due to ease of coordination and infrastructure availability. This may have contributed to increased exposure to AT and reduced affordability barriers among urban dwellers with visual and mobility impairments. Additionally, economic factors also play a role. Urban residents generally experience greater livelihood opportunities, higher income levels, and better access to social protection schemes. These structural advantages likely contribute to the higher AT uptake found among urban residents in this study. This contrasts with rural populations, where poverty and transport challenges can significantly restrict AT acquisition7,8.

The study also found that men (56.6%) were more likely to use AT than women (43.4%). This suggests gender disparities in the uptake and usage of AT. This finding aligns with Visagie et al.19, who explored AT sources, services, and outcomes among PWDs in four Sub-Saharan African countries and reported that patterns of AT use differ by gender and setting. In their study, mobility aids such as walking sticks were more frequently used by men in rural areas, while visual aids were more common among women in urban settings. The current urban-based finding indicates a differentiated gender uptake, possibly influenced by the types of AT available, perceived needs, and gendered access to healthcare resources. Furthermore, the finding contrasts with findings from the United States, which reported higher AT use among women27. These discrepancies may be as a result of contextual and structural differences between high-income countries and LMICs. In Ghana and some African countries, gender norms, caregiver roles, lower socioeconomic status, and limited access to information may pose additional barriers for women8,34,35. These comparisons show that gender disparities in AT use are not universal, but rather shaped by socioeconomic, cultural and geographical contexts. The finding contributes new insights from an urban Ghanaian perspective, underscoring the importance of locally grounded, gender-sensitive strategies that address the structural and cultural barriers that hinder equitable access. This will go a long way in scaling AT adoption in Ghana.

Another significant finding was that the employment rate for mobility-impaired participants (59%) was considerably higher than that of the visually impaired participants (39.3%). The substantially lower employment rate for visually impaired individuals points to deeper structural inequities rather than individual limitations. This disparity reflects institutionalised labour-market discrimination, where employers may perceive visual impairment as a greater barrier to productivity, leading to fewer job offers, lower security, or informal dismissal practices [2, 36] . It also suggests unequal access to training, vocational preparation, and skills-development pathways, which disproportionately disadvantages visually impaired individuals who often encounter inaccessible training materials, limited workplace adjustments and fewer opportunities for career progression. This finding reinforces earlier arguments by Tebbutt et al.8 and the World Health Organisation4, who emphasise that while assistive technologies can enhance employability, they cannot by themselves dismantle discriminatory hiring norms, negative employer attitudes, and systemic exclusion. Although only a handful of the participants reported direct employment barriers, these cases are far from negligible. They signal persistent patterns of exclusion that echo broader social and structural inequalities.

The implications for Ghana are quite significant. Persistent employment barriers indicate a clear gap between policy intentions and lived realities, particularly concerning Sustainable Development Goal 8, which advocates for decent work and economic growth for all individuals irrespective of their differences, and Goal 10, which seeks to reduce inequalities. Moreover, the failure to guarantee inclusive labour-market participation challenges the implementation of global and national frameworks such as the United Nations Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the Ghana Disability Act, 2006 (Act 715). These frameworks mandate equal access to employment, yet structural constraints such as inaccessible workplaces, limited employer awareness, biased recruitment practices, and the absence of enforceable reasonable accommodation policies continue to undermine these commitments.

This finding underscores the urgent need for multi-level and systemic reforms, including stronger enforcement of anti-discrimination laws, employer sensitisation, investment in inclusive vocational training, and the expansion of AT-enabled work environments. Such interventions are essential for transforming disabling labour-market structures and promoting equitable employment outcomes for persons with disabilities.

Another finding that is worth discussing is the strong association between educational attainment and AT use, with higher adoption rates among participants with tertiary education (mobility-impaired, 21.9% and visually impaired, 31%) compared to those with primary education (5.7% and 1.2%, respectively). This disparity reflects not only greater awareness and knowledge of AT among more educated individuals but also underlying structural inequities. Higher education is linked to increased income, access to formal employment, and exposure to information networks, which facilitate AT acquisition, whereas individuals with lower educational levels face compounded barriers, including limited awareness, financial constraints, and reduced access to rehabilitation services7,36. Additionally, many participants reported difficulties using their devices, suggesting gaps in user training and participatory design, which are often more accessible to those with higher education. These findings highlight the need for inclusive, system-level interventions. Healthcare providers, rehabilitation specialists, and NGOs should ensure AT provision includes comprehensive training and user-centred design to enhance accessibility and effectiveness for all persons with disabilities, regardless of educational background.

Moreover, financial assistance, policy advocacy and training programmes emerged as critical facilitators in addressing the barriers to the adoption of AT in Ghana. Both mobility and visually impaired individuals found financial assistance as a remedy to their challenges. It is possible that the high cost of AT can compel users to access fewer effective devices. These potential elements were acknowledged by even participants who do not experience barriers in using assistive devices. Financial support alone is not enough to resolve the barriers. It is important to couple that with awareness campaigns, sensitisation and sustainable policies. This underscores the importance of a multi-sectoral and system-based approach to AT policy and implementation. Proper coordination of financial, policy and capacity-building interventions can reduce physical barriers and enhance inclusive and equitable access.

Limitations

Despite providing important insights into AT use among adults with mobility and visual impairments in urban Ghana, this study is not without limitations. The study relied on self-reported data, which is subject to recall errors and social desirability effects. The respondents may have over- or under-reported their use due to memory lapses or the desire to present themselves in a socially acceptable manner. Again, the study was limited to selected urban districts in the Ashanti region. As a result, the findings may not be generalisable to populations in rural areas where access to healthcare may differ significantly. Future studies should consider including both rural and urban dwellers and incorporate objective measures to validate self-reported data.

Again, the study is subject to potential union-based sampling bias, as participants were recruited from a registered disability group. Membership in such associations may confer advantages which include increased awareness, stronger advocacy support, and better access to services that are not equally to non-members. Therefore, the findings may underrepresent the challenges faced by persons with disabilities who are not affiliated with organised groups. Future studies should include broader sampling strategies to capture a more diverse range of experiences.

Moreso, the current study lacks intersectional data, particularly across age, gender, disability type, and socioeconomic status. An intersectional approach would have made it possible to examine how multiple social identities interact to shape differentiated experiences of AT access and utilisation. This would likely have provided more nuanced insights into why certain subgroups experience greater barriers or lower adoption rates. Future studies should consider incorporating intersectional data to generate a more comprehensive and equity-sensitive understanding of AT access in Ghana.

Finally, despite the fact that the respondents were drawn from multiple urban districts, the analysis was limited by incomplete district-level data due to some respondents not specifying their district of residence. As a result, we could not compare the analysis of AT usage across districts. Future studies should consider a more comprehensive geographic data collection to explore district-level disparities and identify contributing factors. Addressing these limitations would enhance the robustness and generalisability of findings on AT utilisation in Ghana.

Conclusion

The current study used a quantitative and cross-sectional design to examine the prevalence and pattern of AT use and barriers that hinder access to AT among adults with mobility and visual impairments in selected urban districts in the Ashanti region of Ghana. The findings revealed a high prevalence of AT use. Educational level also has a significant influence on AT use, with participants having a tertiary education being frequent users. Employment status also influences AT usage, as the majority of AT users are employed. Most importantly, the study revealed gender-based disparities in AT adoption, reflecting broader patterns of social exclusion that call for an urgent and intersectional policy response. Addressing these inequalities is not only a matter of justice but a necessary tool for achieving the 2030 Sustainable Agenda and the United Nations Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Moreover, despite the high prevalence of AT usage, some users encounter barriers such as financial challenges. The participants identified financial assistance, policy advocacy and training programs as solutions to the barriers captured above. The study suggests that while AT significantly contributes to employability, mobility and independence, barriers regarding accessibility and technical support impede its full potential. It is therefore important to address the issues through policy interventions, collaboration among stakeholders, and user training to improve the effectiveness of AT in Ghana.

Data availability

Data that support the findings of this study is publicly available in a GitHub repository at: https://github.com/RAILADT/uptake-usage-dataset Any additional information will be shared upon request from the corresponding author.

References

United Nations. Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. New York, (2006). www.un.org/disabilities/convention/optprotocol.shtml, accessed 19th December, 2024.

World Health Organisation. World Report on Disability. (2013).

World Health Organisation. WHO Global Disability Action Plan 2014–2021: Better Health for all People with Disability (World Health Organisation, 2015).

World Health Organisation. Priority Assistive Products List: Improving Access To Assistive Technology for everyone, Everywhere (No (World Health Organisation, 2016).

Cieza, A. et al. Framing rehabilitation through health policy and systems research: priorities for strengthening rehabilitation. Health Res. Policy Syst. 20 (1), 101 (2022).

Layton, N. et al. Opening the GATE: systems thinking from the global assistive technology alliance. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 15(5), 484 (2020).

World Health Organisation. Global Report on Assistive Technology. (2022).

Tebbutt, E. et al. Assistive products and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Globalization and Health, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-016-0220-6 (2016).

Pilegaard, M. S. et al. Assistive devices among people living at home with advanced cancer: Use, non-use, and those who have unmet needs for assistive devices? Eur. J. Cancer Care. 31 (4), e13572 (2022).

Meyers, L. Policy gaps in assistive technology access. J. Disabil. Stud. 18 (1), 45–56 (2022).

Joundi, R. A. et al. Activity limitations, use of assistive devices, and mortality and clinical events in 25 high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries: an analysis of the PURE study. Lancet (London, England), 404(10452), 554–569. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01050-X

ATScale. Promoting Access to Assistive Technology in Africa — ATscale. (2024). Available at: https://atscalepartnership.org/events/2024/7/31/promoting-access-to-assistive-technology-in-africa (Accessed: 1 May 2025).

World Health Organization (WHO). Global Cooperation on Assistive Technology (GATE) Initiative: 5Ps Strategy (WHO, 2018).

Organisation World Health. ‘Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health: ICF’, International Classification, 1149, 1–22. Available at: http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/training/icfbeginnersguide.pdf (2002).

Okonji, P. E. & Ogwezzy, D. C. ‘Awareness and barriers to adoption of assistive technologies among visually impaired people in Nigeria’, Assistive Technology, 31(4), 209–219. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10400435.2017.1421594 (2019).

Osam, J. A., Opoku, M. P., Dogbe, J. A., Nketsia, W. & Hammond, C. The use of assistive technologies among children with disabilities: the perception of parents of children with disabilities in Ghana. Disabil. Rehabilitation: Assist. Technol. 16 (3), 301–308 (2021).

Walker, J., Ossul-Vermehren, I. & Carew, M. ‘Assistive Technology in urban low-income communities in Sierra Leone and Indonesia: Rapid Assistive Technology Assessment (rATA) survey results’, UCL (University College London): London, UK. [Preprint], (January). (2022).

Matter, R. et al. Assistive technology in resource-limited environments: a scoping review. Disabil. Rehabilitation: Assist. Technol. 12 (2), 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2016.1188170 (2017). Available at.

Visagie, S. et al. ‘A description of assistive technology sources, services and outcomes of use in a number of African settings’, Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 12(7), pp. 705–712. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2016.1244293 (2017).

Berardi, A. et al. ‘Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology Assistive technology use and unmet need in Canada’, Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 16(8), 851–856. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2020.1741703 (2021).

Boggs, D. et al. ‘Measuring Access to Assistive Technology using the WHO rapid Assistive Technology Assessment (rATA) questionnaire in Guatemala: Results from a Population-based Survey’, Disability, CBR and Inclusive Development, 33(1), 108–130. Available at: https://doi.org/10.47985/dcidj.573 (2022).

Mishra, S. et al. ‘Assistive technology needs, access and coverage, and related barriers and facilitators in the WHO European region: a scoping review’, Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 19(2), 474–485. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2022.2099021 (2024).

Spencer, R. et al. AT satisfaction and barriers in Australia. Australian J. Social Issues. 56 (3), 394–410 (2021).

Borg, J. & Östergren, P. O. Users’ perspectives on the provision of assistive technologies in bangladesh: awareness, providers, costs and barriers. Disabil. Rehabilitation: Assist. Technol. 10 (4), 301–308 (2015).

Jamali-phiri, M. et al. ‘Socio-Demographic Factors Influencing the Use of Assistive Technology among Children with Disabilities in Malawi’. (2021).

Senjam, S. S. et al. ‘Assistive technology usage, unmet needs and barriers to access: a sub-population-based study in India’, The Lancet Regional Health - Southeast Asia, 15, 100213. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lansea.2023.100213 (2023).

Kaye, H. S. ‘Disparities in Usage of Assistive Technology Among People With Disabilities’, (February 2008). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10400435.2008.10131946 (2014).

Desideri, L. et al. ‘Need and access to assistive technology in Italy: results from the rATA survey’, Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 0(0), 1–12. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2025.2503905 (2025).

Ghana Statistical Services. Ghana Statistical Services. Population and Housing Census 2021: Disability Report (Ghana Statistical Service, 2021).

Ward-Sutton, C. Assistive Technology Access and Usage Barriers Among African Americans With Disabilities: A Review of the Literature and Policy. March 2021. (2020).

Osei, S. & Osei, J. The impact of adaptive computer technologies on educational access for students with disabilities in Ghana. Disabil. Stud. Q. 37 (2), 122–134 (2017).

Asamoah, E. et al. ‘Inclusive Education: Perception of Visually Impaired Students, Students Without Disability, and Teachers in Ghana’, SAGE Open, 8(4). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018807791 (2018).

Kyeremeh, S. & Mashige, K. P. ‘Availability of low vision services and barriers to their provision and uptake in Ghana: practitioners ’ perspectives’, (February). Available at: https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v21i2.51 (2022).

Brief, P. ‘Policy Brief: The Impact of on Women’, Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/3310322 (2020).

Boahen, E. A., Frimpong, Y., Owusu, I. & Dadzie–Dennis, A. Factors that influence the usage of prostheses among persons with lower limb amputation in the Kumasi metropolis. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research Review. 8. . (2022).https://doi.org/10.36713/epra9317

Mitra, S. The human development model of Disability, health and Well-being. In Disability, Health and Human Development. Palgrave Studies in Disability and International Development (Palgrave Pivot, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-53638-9_2World.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Responsible Artificial Intelligence Lab – KNUST, for sponsoring this research through the following funders: International Development Research Centre 110469-001 Foreign, Commonwealth and Development OfficeThe French Embassy.

Funding

The authors are grateful to the Responsible Artificial Intelligence Lab – KNUST, for sponsoring this research through the following funders: International Development Research Centre 110469-001. Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. The French Embassy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Enoch Acheampong: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Investigation, Review & EditingVida Kasore: Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original draft, Review & EditingBetty Agyei Kponyo: Visualisation, Investigation, Review & Editing, ResourcesRos Yaw Owusu -Ansah: Investigation, Validation, Formal Analysis, Data CurationJeffrey Kwame Owusu Ansah: Investigation, Writing – Review and editing, Data CurationElizabeth Owusu Ansah: Investigation, Writing – Review and editing, Resources, Formal Analysis, Data CurationJustice Owusu Agyemang: Review and Editing, Resources, Formal Analysis, Data CurationRose-Mary Owusuaa Mensah Gyening: Validation, Review and EditingEmmanuel Ahene: Validation, Review and Editing, Data collectionJerry John Kponyo: Conceptualisation, Supervision, Funding Acquisition, Resources, reviewing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Acheampong, E., Kasore, V., Kponyo, B.A. et al. Barriers to assistive technology uptake among persons with disabilities in selected urban districts in Ghana. Sci Rep 16, 1838 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31466-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31466-4