Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a major global health issue, yet current treatment strategies rarely consider patient age differences, leading to variable therapeutic efficacy and clinical outcomes. Although numerous biomarkers for CRC have been identified, their age-specific expression profiles and biological implications remain poorly understood. This knowledge gap limits the development and clinical deployment of age-tailored interventions. In this study, we applied an age-aware machine learning framework to uncover gene signatures stratified by age using the GSE44076 microarray dataset. We analyzed three CRC-relevant gene categories (Therapeutic, Immune, and Glycosylation) across three data versions: Original, WithAge (age as a feature), and Age Regressed (residual expression). Patient samples were stratified into younger (< 70 years) and older (≥ 70 years) cohorts to identify age-influenced molecular shifts. Random Forest (RF)-based feature selection yielded compact gene signatures that discriminated against tumor, normal, and mucosa. Under 5 × 10 nested cross-validation, Top-10 gene models achieved Balanced Accuracy ≈ 0.94—0.99 and macro-averaged OvR AUC ≈ 0.96—0.99, while Top-3 sets retained strong performance (Balanced Accuracy ≈ 0.87—0.95). We benchmarked RF against Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and k-Top Scoring Pairs (KTSP) classifiers. RF provided the best overall multivariate metrics under shallow-tree constraints (depth 1–2; min leaf 1–2), KTSP models consistently captured age-dependent gene ranking shifts with enhanced sensitivity, especially in external validation. KTSP’s robustness in identifying directional age effects was most evident in the Glycosylation category, where glycan-processing genes showed pronounced age-stratified performance. Permutation tests that replicated the full nested pipeline (N = 100) yielded p≈0.01, confirming that results are unlikely under the null. To uncover deeper regulatory mechanisms, we modeled gene-age interactions, revealing additional biomarkers. External validation using the GSE106582 cohort further supported our findings, although batch harmonization constrained gene coverage by removing platform-unique probes, highlighting a key limitation for microarray-based biomarker translation. Nonetheless, core signatures retained their predictive power, confirming generalizability. Altogether, our results establish age as a critical biological variable influencing CRC gene expression and classifier performance. This study provides a rigorous framework for integrating machine learning, statistical interaction modeling, and biological annotation to guide age-stratified biomarker discovery. Our findings support the development of precision oncology tools tailored to the distinct molecular landscapes of young-onset and late-onset CRC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer research has long been driven by the goal of understanding the molecular underpinnings of tumor initiation and progression, as well as identifying effective therapeutic targets. With the advent of high-throughput sequencing and advanced computation, it is now possible to interrogate gene expression patterns in large patient cohorts stratified by clinical and demographic factors (e.g., age, tissue type, disease status). Colon cancer remains a critical area of study, given its prevalence worldwide and the complexity of its progression from normal mucosa to adenomas and ultimately malignant tumors1,2.

One of the key challenges in analyzing large-scale gene expression data is the presence of high dimensionality, where tens of thousands of genes may be measured simultaneously. Traditional univariate approaches, such as ranking genes by fold change or by a single measure like area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), can be informative for identifying broad patterns. However, they often fail to capture the intricate multivariate interactions among genes3,4. We and others have shown that age-related dysregulation of intestinal epithelium fucosylation correlates with increased colon cancer risk5.

Many previous studies treat age as a continuous variable without thoroughly exploring how gene expression shifts in older vs. younger populations. To address how multigene programs jointly distinguish tissue types and how those programs vary with age, we developed an age-stratified machine-learning framework focused on biologically grounded gene categories.

In this study, we focused on three functional gene categories (Therapeutic, Immune, and Glycosylation) to classify samples (normal, tumor, or mucosa) in younger (< 70) versus older (≥ 70) patients. We chose these categories based on biological relevance: Therapeutic genes include those involved in oncogenic signaling, apoptosis, and drug targets6; Immune genes reflect the tumor immune microenvironment and the growing role of immunotherapy7; and Glycosylation genes influence cell to cell communication and immune recognition via post-translational modifications, which change during tumorigenesis and aging8.

To accurately classify gene expression profiles and identify biologically meaningful biomarkers, we implemented multiple machine-learning classifiers, including a k-Top Scoring Pairs (KTSP) method in addition to Support Vector Machines (SVM (linear)) and gradient boosting, alongside our primary Random Forest (RF) model. Each of these methods offers distinct advantages for high-dimensional genomic data: SVMs excel at finding complex nonlinear decision boundaries, boosting algorithms (such as Gradient Boosting Machine) iteratively combine weak learners for high accuracy, and the KTSP algorithm provides a simple, parameter-free classifier based on the relative expression ordering of top gene pairs9 yielding easily interpretable decision rules.

RF handles thousands of features with ease while mitigating overfitting via ensemble averaging of many decision trees, each trained on random subsets of samples and features10,11. Unlike linear classifiers, tree-based ensembles capture nonlinear and conditional gene–gene interactions. Random Forests also provide feature-importance measures that highlight discriminative genes12,13. In contrast, SVM and boosting models require careful tuning and do not inherently provide straightforward biological interpretability (e.g., SVM’s kernel decision function lacks direct feature importance scoring)14. Given these advantages, we used Random Forest as the primary tool for feature selection and classification. At the same time, we employed SVM, GBM, and KTSP classifiers in parallel to ensure our findings were not dependent on any single algorithm. This strategy ensures we leverage RF’s interpretability and robustness while confirming that alternative classifiers reach comparable performance, strengthening confidence in the identified age-stratified gene signatures.

We then identified the top 10 most important genes in each category that best distinguished tissue type and age group. To complement the multivariate approach, we examined the traditional volcano plots (log₂ fold-change vs. -log₁₀ p-value between young and old groups). This two-pronged strategy allowed us to detect genes with subtle but consistent expression shifts that might be missed by simpler univariate methods yet are captured by the multivariate RF model.

We also examined alternative modeling strategies to directly assess the influence of aging on our results. In particular, we applied an age-regressed approach (where gene expression values were adjusted to remove the baseline effect of chronological age) and built models with explicit age-interaction features (gene × age terms) to test for age-dependent effects. These analyses indicated that the classification performance and key predictive genes remained essentially unchanged (data not shown), confirming that our identified biomarkers reflect true differences between normal and tumor tissue that are modulated by age group, rather than being driven solely by age.

Finally, to ensure our findings are generalizable, we validated our models on an independent external dataset (GEO accession GSE10658215) comprising colorectal cancer tumors and matched normal mucosa from the ColoCare study. After performing batch effect correction, the external validation confirmed that our top gene classifiers maintained high accuracy (approximately 93–97% across models) on the independent cohort, reinforcing the robustness and real-world applicability of these age-stratified gene signatures.

Our study provides a multi-faceted analysis of gene expression data, bridging computational, biological, and clinical perspectives (Fig. 1). By homing in on Therapeutic, Immune, and Glycosylation gene sets across different ages and tissue types, and by leveraging a Random Forest alongside complementary classifiers (SVM, GBM, K-TSP), we reveal key age-related expression shifts in normal versus tumor colon tissues. This integrated machine-learning approach yields an actionable shortlist of top genes for potential therapeutic or diagnostic development, highlighting the value of incorporating age stratification when searching for biomarkers in cancer.

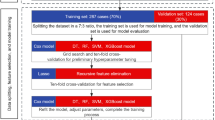

Flow chart. This flow chart illustrates the overall methodology. After loading and verifying the GSE44076 dataset, we stratified samples by age and filtered for specific functional gene sets (Therapeutic, Immune, Glycosylation). We then transformed the data for machine learning and trained Random Forest models as the primary classifier (with SVM and GBM models run in parallel for comparison), validating performance through cross-validation and permutation testing. Finally, we selected top genes based on RF feature importance and generated volcano plots to visualize age-related differential expression.

Methods

Our approach offers multiple advantages. By focusing on the Therapeutic, Immune, and Glycosylation categories, we integrate biological knowledge about pathways commonly implicated in tumor development and age-related tissue changes. Meanwhile, gene expression data were reformatted from long to wide format, where each row corresponded to a unique sample and each column to a specific probe ID. This transformation allowed the expression matrix to be merged with associated clinical metadata, including sample type (tumor, normal, mucosa) and age (as both a binary variable < 70 vs ≥ 70 and a continuous covariate)16.

To assess classification performance, we employed a nested cross-validation strategy using fivefold outer CV and 10 repeated stratified splits. Within each training fold, the top 10 (or top 3) features were identified using Random Forest feature importance scores, and models were rebuilt on the reduced feature set. This nested approach minimizes optimistic bias and provides an unbiased estimate of performance. In parallel, a K-TSP classifier was trained within each fold using the top 50 candidate genes (preselected via RF importance), from which 10 top gene-pairs were selected for pairwise rank-based classification. The complete pipeline was implemented separately for each age group (< 70 vs ≥ 70) and for three data scenarios: (i) original raw data, (ii) raw + Age feature (“WithAge”), and (iii) Age-regressed data (after removing linear age effects). In addition, we constructed gene × Age interaction features (e.g., CLDN1 × Age) and trained RF models on these augmented matrices to explicitly identify age-modulated biomarkers.

To evaluate generalizability, final age-stratified RF and K-TSP classifiers (trained on the GSE44076 training set after batch-effect harmonization) were applied to an independent, batch-corrected external dataset (GSE106582). Model performance was quantified using macro-averaged one-vs-rest AUC and accuracy, and permutation tests (n = 100) were conducted on the final RF models to assess statistical significance of observed accuracy relative to randomly permuted labels.

Permutation testing to confirm that our high accuracies did not arise by chance, an important safeguard in the absence of an independent external cohort17. Random Forest’s ensemble methodology provides a robust multivariate framework that captures complex gene–gene interactions, delivering a more comprehensive picture than single-metric or univariate methods10. By examining feature importances in Random Forest and mapping probe IDs to gene symbols18, we generated interpretable top-gene lists and bar plots that can serve as hypotheses for downstream validation. The “top 10” gene lists in each category thus function as testable hypotheses for functional experiments or targeted therapeutics, paving the way for translational follow-up. Finally, by evaluating classification accuracy through cross-validation and permutation tests13, we ensure that the identified gene signatures hold genuine predictive power rather than arising from random chance. Overall, this methodologically rigorous workflow complements our biological focus by providing a reproducible and statistically sound foundation for age-stratified analyses of colon tissue samples.

In this study, following the approach we considered an \(n x m\) data matrix \(X\), where each row \({X}_{i}\) represents a tissue sample (observation) and each column \({X}^{j}\) corresponds to a gene (feature) as previously published study19. Each observation \({X}_{i}\) is associated with a class label \({y}_{i} \in Y\), such as “sick” or “healthy,” forming a labeled dataset \(D= {\left\{\left({X}_{i}, {y}_{i}\right)\right\}}_{i=1}^{n}\). Our goal is to train a classification function \(f:X\to Y\) to predict labels for new samples17. To estimate prediction error during model evaluation, we used k-fold cross-validation with k = 5. For this, the dataset was partitioned into five equal parts. Each model was trained in four parts and validated on the fifth, iterating through all combinations. The cross-validation error was computed using the standard formula:

where \({f}^{-K(i)}\) denotes the fitted function with the \(K(i)-th\) fold removed, and \(L(\cdot )\) is a loss function comparing the true and predicted class labels. This formulation was adopted from previously published study cross-validation as a standard technique for reliable model assessment in high-dimensional settings20. We also used permutation testing as an additional safeguard against spurious findings17.

All data analysis, visualization, and machine learning modeling in this study were performed using Python (version 3.12.3). Core packages included pandas for data manipulation, numpy for numerical operations, scikit-learn for machine learning model development and evaluation, matplotlib and seaborn for plotting, and statsmodels for statistical testing. Gene expression matrices were processed and merged using customized Python scripts. Random Forest, Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM), and Support Vector Machine (SVM (linear)) models were built using the scikit-learn library, and performance metrics were derived from repeated cross-validation and permutation tests. All analyses were conducted in a JupyterLab environment to ensure reproducibility and interactive documentation.

Patient cohort and dataset

We analyzed the publicly available GSE44076 dataset, which includes gene expression profiles from 246 colorectal tissue samples comprising 98 colorectal cancer (CRC) tumors, their matched adjacent normal mucosa, and 50 healthy mucosal biopsies from individuals without colonic lesions (identified via colonoscopy). All samples were generated using Affymetrix GeneChip microarrays, and age and sample-type annotations were available for every patient.

Gene expression values were derived from log₂-RMA normalized intensities provided in the original series matrix file15,21. Probes with missing values or near-zero variance across samples were removed prior to analysis. No additional filtering based on absolute expression intensity was applied, as downstream models rely primarily on relative differences between groups rather than absolute levels.

Preliminary exploration of age distribution revealed that tumor samples tended to cluster among older individuals, whereas mucosa samples spanned a broader age range. There was no evidence of systematic age imbalance within the Normal versus Mucosa samples, indicating the dataset was suitable for age-stratified analyses. Patients were stratified into younger (< 70 years) and older (≥ 70 years) groups, in line with epidemiologic studies of age-related CRC biology. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) confirmed that expression profiles cluster primarily by tissue type, with secondary variance corresponding to age-related transcriptional shifts22.

To assess external reproducibility, we additionally incorporated the GSE106582 dataset (ColoCare cohort), which contains gene expression profiles of 77 colorectal tumors and 117 matches normal mucosa. Gene expression matrices from GSE44076 (training) and GSE106582 (validation) were log₂-transformed, quantile normalized and harmonized using a stratified ComBat batch-effect correction approach prior to external model validation. This ensured that technical differences between studies did not obscure true biological variation.

Batch harmonization

Because the expression data in this study were obtained from two distinct GEO datasets (GSE44076 and GSE106582), we performed batch-effect harmonization to mitigate study-specific technical variation prior to downstream analyses. To avoid the inadvertent removal of genuine biological signal (particularly age-related transcriptional effects, which were unevenly distributed across studies) we adopted a stratified ComBat framework, as originally proposed by Johnson et al.23 and later refined by Nygaard et al.24for preservation of covariate effects.

Briefly, Mucosa samples were excluded from the harmonization step so that only Normal and Tumor samples were considered. Samples were stratified into Young (< 70 years) and Old (≥ 70 years) groups, and ComBat was applied separately within each stratum, using the variable Batch (i.e., study ID: GSE44076 vs. GSE106582) as the adjustment covariate and Condition (Tumor vs. Normal) as a protected biological variable (via the mod parameter in ComBat). This stratification strategy preserves age-dependent differences while avoiding rank-deficiency issues that arise when covariates are unequally distributed across datasets.

The two age-stratified batch-corrected matrices were then concatenated and used for all subsequent analyses (PCA in Fig. 2, classifier training and external validation). Prior to applying ComBat, we removed probes exhibiting missing values or near-zero variance within a stratum, in accordance with the best-practice recommendations of Leek et al.25. All harmonization steps were implemented in Python using the pycombat implementation of the ComBat algorithm.

Age distribution and PCA analysis of colorectal cancer datasets (GSE44076 and GSE106582). (A) Age distribution of samples in raw GSE44076 stratified by sample type (Mucosa, Normal, Tumor). (B) Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of raw GSE44076 expression matrix, colored by sample condition. PC1 (16.1%) clearly separates mucosa/normal samples from tumor samples, while PC2 (8.0%) shows minor age-associated variation (point size reflects age in years). (C) PCA of raw GSE106582 dataset demonstrates a similar separation pattern between tumor and mucosa conditions along PC1 (16.1%), with slight dispersion across PC2 (8.0%) and a modest age gradient. (D) Age distribution in raw GSE106582, stratified by sample type, again revealing comparable age distributions between mucosa (normal) and tumor groups, centered around the seventh decade of life. (E) PCA of the merged, batch‐corrected dataset (GSE44076 + GSE106582) colored by sample condition. The batch effect has been successfully removed, as indicated by clear clustering by biological condition rather than by dataset of origin. (F) PCA of the merged batch‐corrected dataset colored by batch (GSE44076 vs. GSE106582). Samples from both datasets are interspersed across the PCA space, confirming that ComBat effectively mitigated batch effects. Point size in all PCA plots reflects sample age (smaller = younger, larger = older).

Gene category selection and feature extraction

To focus the analysis on biologically meaningful pathways that are plausibly modulated by aging, we restricted our investigations to three functional gene categories: Therapeutic, Immune, and Glycosylation. These categories were selected based on prior evidence of their involvement in colorectal tumor development and age-associated molecular alterations. Probe-to-gene mappings were obtained from the Affymetrix Human Genome U219 Array platform (GPL13667), and functional annotations were derived from the Gene Ontology (GO) Biological Process database.

Specifically, we queried ontology terms corresponding to key biological functions relevant to each category (e.g., “immune system process,” “protein glycosylation,” “response to drug,” etc.) and extracted the associated gene symbols. These symbols were matched to probe IDs in the GPL13667 platform annotation file to produce curated gene lists for the Therapeutic, Immune, and Glycosylation categories. This ontology-guided keyword strategy ensured that the analyses were focused on pathways known to be relevant to tumor biology and age-related regulation7,8,26.

For Therapeutic genes, GO terms such as therapeutic, apoptosis, signal transduction, and immune checkpoint were used, reflecting pathways involved in oncogenic signaling, therapeutic resistance, and drug responsiveness. Immune-related genes were identified via terms including immune, cytokine, T cell, macrophage and inflammatory response, consistent with the key role of the tumor-immune microenvironment in CRC. Glycosylation-associated terms included glycosylation, fucosylation, sialylation, glycan processing, and N-acetylglucosamine, reflecting the growing recognition of glycosylation as a modulator of immune recognition and metastatic behavior in CRC, particularly in aging tissues.

To verify the coverage of these curated lists, we identified overlaps between the GO-based gene symbols, and the gene expression probes present in GSE44076. This resulted in 13,893 Therapeutic probes, 4286 Immune probes, and 702 Glycosylation probes, providing broad coverage and ensuring that downstream modeling captured both core age-independent tumor signatures and age-modulated expression effects.

The same functional probe sets were maintained across all complementary analyses (age‐stratified RF and KTSP, age‐regressed modeling, and gene × age interaction analysis) to ensure comparability and to allow direct attribution of classification performance and age effects to known biological pathways.

For the external validation step, however, the probe lists were first intersected between GSE44076 (Affymetrix Human Genome U219 Array) and GSE106582 (Illumina HumanHT-12 V4.0 expression beadchip, GPL10558) after batch‐effect harmonization. This resulted in a reduced set of common genes, due to platform differences and the removal of duplicated gene symbols (i.e., instances where the same gene appeared under multiple probe IDs). Specifically, the validation models were trained on 4974 Therapeutic genes, 1464 Immune genes, and 249 Glycosylation genes, using gene symbols rather than probe IDs to define the common feature space (to ensure that equivalent molecular entities are compared across datasets regardless of platform-specific probe annotations).

Data processing and transformation

The original long-format expression matrices (probe IDs as rows and samples as columns) were transformed into wide-format tables, in which each row represents an individual sample and each column corresponds to the expression value of a specific probe16. This reshaping allowed direct merging with sample-level clinical metadata (including age, age group, and sample type), ensuring that both molecular and clinical attributes were available within a single unified dataset for downstream analysis.

Prior to modeling, the expression data were log₂-transformed and quantile normalized, and probes with near-zero variance or missing values were removed. For the age-regressed analysis, we fitted a linear regression model of the form Expression = β₀ + β₁·Age + ε, where β₀ is the age-independent intercept and β₁ represents the linear effect of age on gene expression. Residuals (ε) were retained as age-adjusted expression values27,28.

For the age-interaction analysis, new features of the form Gene × Age were created by multiplying each gene’s expression value with the corresponding age value, thereby enabling the detection of genes whose association with tissue type changes with age29.

In order to perform external validation, the GSE44076 and GSE106582 expression matrices were log₂-transformed, quantile normalized, and subsequently batch-harmonized using the stratified ComBat approach described above23,24. Only common gene symbols between the two datasets were retained (4974 Therapeutic, 1464 Immune, and 249 Glycosylation genes), to ensure meaningful cross-platform comparison (Affymetrix vs. Illumina).

All preprocessed datasets (original, age-regressed, age-interaction augmented, and batch-corrected) were subsequently used as input to the nested cross-validation and external validation procedures described in the preceding sections.

Two distinct data-handling strategies were employed depending on the analysis stage. For internal discovery analyses, including age-stratified classification, regression of age, volcano plots, and RF/GBM/SVM/KTSP comparisons, we used the raw GSE44076 dataset to preserve age-dependent variation. For external validation, GSE44076 was harmonized with GSE106582 using ComBat, and only genes common to both platforms were retained. For external validation, all classifiers were retrained on the harmonized GSE44076 data and validated on the harmonized GSE106582.

Machine learning approach

We evaluated four classification algorithms (Random Forest (RF), k-Top Scoring Pairs (KTSP), Support Vector Machine (SVM (linear)), and Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM)) to predict tissue type (tumor, normal, mucosa) within each age group and gene category. For comparative benchmarking, we implemented Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM), and linear-kernel Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifiers in addition to the KTSP approach. To ensure consistency, we applied identical fivefold × 10-repeat stratified cross-validation for all models and evaluated both top-10 and top-3 RF-derived feature subsets per age group and gene category. Multiclass discrimination performance was quantified using macro-averaged one-vs-rest AUC (OvR AUC) following the scikit-learn implementation and reported as mean ± standard deviation across outer folds. For SVM, absolute coefficient weights were used to rank feature contributions, while RF and GBM used standard impurity-based feature importance scores. Accuracy and AUC distributions across classifiers were then summarized and compared, with results visualized using bar plots contrasting top-10 vs. top-3 signatures. All comparisons were performed separately within each gene category (Therapeutic, Immune, Glycosylation) and for younger (< 70 years) and older (≥ 70 years) subgroups. We used RF because it performs competitively on high-dimensional data when model capacity is controlled and overfitting is routinely audited. In the present work we paired RF with explicit capacity constraints and diagnostics (learning curves, permutation tests, Out-of-Bag (OOB), and fold-to-fold feature-rank stability), rather than assuming immunity to overfitting10,12,18. In parallel, a linear SVM and a GBM classifier were trained as complementary approaches to benchmark performance. In addition, we implemented a KTSP classifier, which uses relative gene expression rankings rather than absolute values and has been shown to be particularly robust in cross-platform transcriptomic analyses30.

Random forest

Considering our age-stratified transcriptomic analysis using Random Forest classification, the work provides a valuable theoretical and practical framework for applying Random Forests (RF) to high-dimensional genomic data13. Their formulation emphasizes that RF is built from an ensemble of \(T\) decision trees, each grown on a bootstrap sample of the training data. A classifier that consists of a group of tree-structured classifiers \(\{h \left(x, {\Theta }_{k}\right), k=1,\dots \}\) is called a random forest10. Each tree casts a unit vote for the most popular class at input \(x\), and the \(\Theta k\) are independent, identically distributed random vectors10. For a classification problem with classes \(\{c1,c2,\dots ,cm\}\), the prediction for a new sample \(x\) can be written as

where \({h}_{k}\) is the class predicted by the \(kth\) tree, and \(\text{I}[\cdot ]\) is the indicator function. In practice, if we have \(T\) trees, each tree \({h}_{k}\) predicts a class label for a given input \(x\).

To limit variance and make overfitting detectable, RF hyperparameters were capacity-controlled and tuned only within the inner loop of the nested CV: n_estimators = 300; max_depth ∈ {1, 2}; min_samples_leaf ∈ {1, 2}; max_features ∈ {‘sqrt’, ‘log2’, 0.2}. Bootstrap sampling and default class weights were used. All feature selection (Top-3 / Top-10) and hyperparameter tuning occurred inside the inner loop of the 5 × 10 nested CV. The configuration and complete tuning grid are reported in Sup. Table 1. To get OOB scores, we used getattr() function.

Support vector machine (linear)

We benchmarked a linear-kernel support vector machine (SVM) as a margin-based classifier suited to high-dimensional, low-sample gene-expression settings. Within each outer fold of the 5 × 10 nested cross-validation, feature selection (top-10 and top-3 genes) was performed strictly on the training split; the linear SVM (C-SVC with probability = True) was then fit and evaluated on the held-out fold. Multi-class decisions used the one-vs-one strategy implemented in scikit-learn, and probabilities were obtained by Platt scaling before macro-AUC computation. We favored the linear kernel over nonlinear alternatives to preserve interpretability (signed coefficients as feature weights), reduce tuning burden, and because the small top-N panels were empirically separable without additional kernels. Results are reported as mean ± SD of outer-fold accuracy and macro-AUC across repeats (Table 8)31.

K-top scoring pairs (KTSP; rank-based rules)

To provide a transparent and platform-robust baseline, we implemented KTSP using relative expression orderings of gene pairs rather than absolute expression levels. For each class (one-vs-rest) within the training split of the inner loop, we restricted the candidate space to the top-50 RF-ranked genes (to control combinatorics without leakage), then selected K = 10 highest-scoring pairs whose within-class ordering best distinguished that class from the others. A sample’s class score is the fraction of that class’s K rules satisfied, and prediction selects the class with the highest score; scores were normalized and used as probabilities for macro-AUC. In the With-Age representation we excluded the Age covariate from pair mining to avoid non-biological “Age vs gene” rules. KTSP complements tree ensembles by offering simple decision rules that are resilient to monotone transformations and cross-platform effects32.

Gradient boosting (GBM; scikit-learn)

As a complementary ensemble to Random Forest, we used scikit-learn’s gradient boosting classifier, which builds an additive model of shallow decision trees trained stage-wise to minimize the empirical loss. Within each outer fold, after inner-loop feature selection on the training split (top-10 or top-3 genes), a GBM with 200 estimators (default learning rate and depth unless otherwise noted) was fit, and class probabilities were used to compute macro-AUC alongside accuracy; stratified folds mitigated class imbalance. GBM provides a different inductive bias from bagged forests, enabling robustness to check that the discovered signatures are not model-specific, while still allowing feature-level importance summaries from split usage33.

For multiclass performance, we computed macro-averaged one-vs-rest (OvR) AUC scores, following the scikit-learn implementation. In this procedure, a binary OvR AUC is calculated for each class against all others, and the results are averaged unweighted across classes to yield the macro-AUC. This protocol was applied uniformly to Random Forest, GBM, and SVM classifiers using probability outputs and to KTSP classifiers by normalizing class scores (fraction of satisfied rules) to [0,1] and treating them as probabilities. We report the mean macro-AUC across outer folds and its standard deviation as an empirical confidence interval (Table 8). This uniform approach ensures comparability of AUC values across all algorithms and age groups.

For each model, hyperparameters were optimized within the training folds via nested cross-validation (5 outer folds × 10 repeats). Each classifier was trained and evaluated separately for the younger (< 70) and older (≥ 70) cohorts in each gene category, thereby preserving the age-stratified design.

To compare classifier performance across age groups and gene categories, we applied a two-stage evaluation strategy. First, each classifier was trained using all genes in the category to assess overall classification capability (nested CV accuracy, macro-AUC, and permutation-based significance). Second, we computed feature/importances within each fold, extracted the top 10 genes, and retrained the model using only the top 3 genes to assess whether accurate classification could be achieved with limited features. A permutation test with 100 label shuffles was applied to each final RF model to confirm that the observed performance exceeded that expected by chance (p < 0.01 in all cases).

Importantly, the same evaluation procedure was applied to the age-regressed and gene × age interaction datasets to test whether performance differences were driven by chronological age or by genuine tumor-related biology. Final RF and KTSP models from the batch-harmonized GSE44076 dataset were subsequently applied to the external validation dataset (GSE106582) to quantify generalizability.

All machine learning and classification parameters used in this study are detailed in Sup. Table 1, including hyperparameter configurations for each classifier, cross-validation settings, feature selection thresholds, and age-interaction modeling strategies. Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM), and k-Top Scoring Pairs (KTSP) classifiers were implemented using Python’s scikit-learn library or equivalent R-based logic. The same cross-validation and selection framework was applied across all gene categories and age-stratified versions to ensure fair comparison.

Age-interaction terms were computed using raw (uncorrected) GSE44076 data to preserve biological variance that would otherwise be removed during batch correction. Batch effect correction was exclusively applied during the external validation phase. Specifically, we harmonized the GSE44076 training dataset with the independent GSE106582 validation dataset using ComBat, ensuring alignment of shared gene expression distributions across platforms. Only genes common to both platforms were retained. All models (Random Forest and KTSP) were then trained on the batch-corrected version of GSE44076 and externally validated on the corrected GSE106582 dataset.

In contrast, age-stratified classification, age-regressed interaction modeling, volcano plots, and classifier comparisons across RF, GBM, SVM, and KTSP were conducted on the raw GSE44076 data, uncorrected GSE44076 dataset to preserve native biological variation, particularly age-associated expression patterns that may be masked by batch correction. This distinction was critical to preserve age-dependent signal integrity during discovery and to ensure comparability during cross-dataset validation.

Considering our age-stratified transcriptomic analysis using Random Forest classification, the work by Chen and Ishwaran13 provides a valuable theoretical and practical framework for applying Random Forests (RF) to high-dimensional genomic data. Chen and Ishwaran’s article highlight how RF excel in the genomic contexts, owing to their ability to model complex, nonlinear interactions between genes, to incorporate correlation structures, and to handle high-dimensional data without severe overfitting13. These strengths dovetail with our approach of filtering genes into Therapeutic, Immune, and Glycosylation categories, since each functional pathway can contain dozens to hundreds of correlated features.

By averaging predictions across many trees, our final classifier not only reduces variance but also allows for a feature-importance ranking. This aligns with the theoretical underpinnings from Chen and Ishwaran’s paper13, where the authors discuss the importance of bootstrap aggregation and random splitting in minimizing bias and decorrelating individual trees, respectively. In our setting, this framework underpins the top 10 and top 3 gene selection for each category and age group. After computing importance scores, we retained only the most discriminative genes, confident that their combined effect would yield accurate classification even in a large search space of gene expression data.

Feature selection, model validation and statistical controls

Permutation testing was performed by randomly shuffling the sample labels (tumor, normal, mucosa), thereby disrupting any true association between gene expression and class labels13. After each shuffle, the Random Forest classifier was retrained using identical parameter settings, and the model was evaluated using the same 5 × 10 nested stratified cross-validation framework applied in the main analyses, including inner-loop feature selection and hyperparameter tuning34. This procedure was repeated 100 times, generating a distribution of cross-validation accuracies under the null hypothesis of no biological association. The original classification accuracy was then compared to this null distribution, and a p-value was computed as the proportion of permuted models that achieved an accuracy equal to or higher than the observed accuracy19.

To obtain stable performance estimates and minimize overfitting, we employed nested, stratified cross-validation (5 outer folds × 10 repeats) across all models and gene categories. Outer folds were used for model evaluation, while feature selection and hyperparameter tuning (including KTSP pair selection, RF feature ranking, and SVM/GBM parameter optimization) were confined strictly to the inner folds. This procedure was carried out for each of the three functional gene categories (Therapeutic, Immune, Glycosylation) and separately for younger (< 70) and older (≥ 70) patient subgroups.

We first trained each model using the full set of category-specific genes. Next, the genes were ranked according to Random Forest feature importance, and the top 10 genes in each category were selected to construct a more interpretable and biologically tractable classifier13. To assess the stability of the predictive signal, we additionally generated a top-3 gene panel by selecting the most highly ranked genes from the top-10 list and re-trained the model using only these three features.

Importantly, the same feature reduction strategy (full, top-10, top-3) was also applied to the age-regressed and age-interaction datasets to evaluate whether the predictive signal was driven primarily by age or by age-independent tumor biology. After cross-validation, the final RF and KTSP models were re-trained on the full GSE44076 training matrix and evaluated on an independent 30% hold-out set as well as the external GSE106582 test cohort, both of which confirmed high accuracy and generalizability of the sparse models. While a top-10 and top-3 threshold was chosen for interpretability, we note that systematic methods such as recursive feature elimination or stability selection could be used in future studies to further optimize feature subset size35,36.

Collectively, this tiered feature-reduction and validation strategy demonstrates that a small set of genes is sufficient to achieve high tumor classification accuracy and provides a framework for clinically feasible diagnostic signatures suitable for translation into precision medicine initiatives.

Overfitting diagnostics

We quantified potential overfitting with three complementary approaches, which are also reported in Table 5.

(i) Learning curves (Figs. 4E, F, Suplemetary Figs. 1E, F, 3E, F ): Within each outer-fold training split we trained RF on stratified subsamples of increasing size and recorded training balanced accuracy and cross-validated balanced accuracy (fivefold CV within the training split). Curves were averaged across outer folds; the shaded band indicates ± 1 SD.

Top 10 Differentially Expressed Genes (Tumor) Across Therapeutic, Glycosylation, and Immune Categories by Age Group. This figure presents heatmaps showing the expression levels (Tumor) of the top 10 differentially expressed genes across different functional categories: Therapeutic, Glycosylation, and Immune, stratified by age groups (Young vs. Old). The values are used to highlight and visualize clear differences in gene expression between younger (< 70) and older (≥ 70) colorectal cancer patients, illustrating potential age-related transcriptional variations across these critical biological pathways. (A) Top 10 Differentially Expressed Genes (Therapeutic (Tumor)). (B) Top 10 Differentially Expressed Genes (Glycosylation (Tumor)). (C) Top 10 Differentially Expressed Genes (Immune (Tumor)).

(ii) Feature-rank stability: For each age stratum and gene set we computed Spearman rank correlations (ρ) of RF importances across outer folds; the distribution of ρ values summarizes how stable the selected genes are to data perturbation (Table 5 under “Rank Stability MedianRho”).

(iii) Permutation tests: The full 5 × 10 nested CV was repeated with permuted class labels (N = 100 permutations). The empirical p-value from this null distribution is reported in Table 5 under “Permutation PValue.” In addition, OOB(Out-of-Bag)-CV differences are reported as a direct measure of RF’s generalization stability.

(iv) Cross-validated AUC (OvR Macro): Multiclass discrimination performance was quantified as the mean macro-averaged one-vs-rest AUC (CV AUC OvR Mean), calculated across outer folds using scikit-learn’s implementation. For each class, a binary OvR AUC was computed against all others, and values were averaged unweighted across classes. The mean and standard deviation across outer folds are reported in Table 5 as CV AUC OvR Mean and CV AUC OvR SD.

Univariate vs. multivariate analysis

To complement the multivariate machine learning framework and better understand the individual contribution of specific genes, we also performed traditional univariate differential expression analyses. Whereas the RF and KTSP multivariate classifiers simultaneously evaluate gene–gene interactions, nonlinear effects, and age-dependent correlations to classify tumor, normal, and mucosa samples, the univariate analysis independently tested each gene for differential expression between age groups (< 70 vs ≥ 70). The results were visualized using volcano plots (log₂ fold change vs. -log₁₀ p-value), enabling the identification of genes that exhibit individual age-associated differences17,37.

Overall, the multivariate approach revealed gene sets whose collective behavior drives accurate tissue classification in an age-stratified manner, including interaction effects that would not be detected in isolated, single-gene tests. In contrast, the univariate analysis highlighted individual genes with statistically significant expression differences between younger and older patients. Integrating both approaches allowed us to prioritize genes that were individually significant and contributed to multigene interaction networks underlying colorectal cancer progression12.

This dual perspective is particularly important for age-focused studies, where interactions between age and gene expression can be biologically meaningful even when main effects are modest38.

Pathway enrichment and circular bar plot visualization

For each gene category, we focused on tumor tissue data only (excluding normal and mucosa for this analysis). We took the top 10 differentially expressed genes in tumors (by highest absolute log₂ fold-change between age groups) for each category to assess their concentration in specific sub-pathways. These genes were not selected based on machine learning feature importance and thus provide an independent biological summary of age-related expression changes. These probe IDs were converted to gene symbols (using a custom platform file), and duplicates were removed to yield a unique gene list per category.

We performed pathway enrichment on these gene lists using g:Profiler, to check if the age-associated genes clustered in specific biological pathways. The enrichment used default g:Profiler parameters (organism Homo sapiens, data sources Gene Ontology Biological Processes (GO:BP), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), Reactome (REAC)), with significance threshold FDR < 0.05. We selected the top 20 enriched pathways for each category using a circular bar plot (created in Python 3.12 with Pandas, NumPy, and Matplotlib). In this plot, bar height corresponds to pathway significance (− log₁₀ FDR), and pathway names are arranged around the circle. Overlapping gene symbols are annotated on the outer ring of the plot to show which genes contribute to each pathway. Although we selected 20 genes in the code, because of our threshold, in each category, the plots do not represent a total of 20 pathways.

Results

Age-driven gene expression shifts in crc: therapeutic, immune and glycosylation insights

To explore whether aging influences the molecular landscape of colorectal cancer (CRC), we first examined the age distribution and sample composition of both the discovery dataset (GSE44076) and the independent validation dataset (GSE106582). As shown in Fig. 2A and 2D and summarized in Table 1, tumors were predominantly found in older patients (median age ≈71 years), whereas mucosal samples represented a broader age range. Importantly, the median age of normal and tumor samples in GSE44076 was identical (71 years), confirming that no systematic age bias would confound subsequent group comparisons39. Principal component analysis (PCA) of the raw GSE44076 (before batch effect correction) expression matrix (Fig. 2B) revealed that the first principal component (PC1; 16.1% of variance) clearly separated tumor from normal/mucosa, whereas the second component (PC2; 8.0%) captured subtle age-related variation within tissue types.

PCA on the raw external dataset GSE106582 (before batch effect correction) (Fig. 2C) showed a comparable pattern, suggesting that age‐associated transcriptomic shifts are present in both studies. After applying stratified ComBat batch correction (based on age group and tissue type), the integrated PCA plot (Fig. 2E–F) demonstrated that samples clustered primarily by biological condition rather than by dataset source, confirming successful technical harmonization. We next investigated age‐dependent transcriptional shifts in tumor samples, stratified by functional gene category. In the Therapeutic gene panel (Fig. 3A and Table 2), several genes involved in signaling, apoptosis, and epithelial differentiation showed strong age-related differences. NPSR1, a neuropeptide receptor previously linked to inflammation and CRC progression40, was significantly lower in older tumors (mean log₂ expression: 3.44 in < 70 vs. 2.56 in ≥ 70; log2FC = -0.319, p = 0.0038). Similarly, CXCL5 (a chemokine that promotes angiogenesis and metastasis) displayed marked downregulation in older patients (-0.30; p = 0.020), suggesting an attenuated CXCL5-driven signaling axis in aged tumors41. Conversely, PPP2R2C, a regulatory subunit of PP2A that modulates cell-cycle signaling, was upregulated in older tumors (log2FC = + 0.27; p = 0.0047). This upregulation may reflect an age-dependent activation of kinase/phosphatase signaling cascades in tumor cells42. A similar increase was observed for GPR37, a G-protein-coupled receptor implicated in stress responses (log2FC = + 0.23; p = 0.0099), which may indicate remodeling of stress response pathways during tumor progression in older individuals.

The Immune gene panel (Fig. 3B, Table 3) showed consistent downregulation of several innate immune mediators in older tumors. CXCL5 again exhibited the largest negative fold change (− 0.30), further underscoring the loss of pro-inflammatory signaling with advancing age. SAA1/SAA2, serum amyloid proteins involved in acute phase response43, were also downregulated (log2FC = − 0.24; p = 0.014). In contrast, C8orf84, which has been associated with immune activation and improved CRC prognosis44, showed a positive log2FC of 0.25 (p = 0.017). These results support an age-related reconfiguration of immune gene activity, with reduced chemokine expression and compensatory induction of immune‐regulating pathways in older tumors.

Age-related patterns were also detected in the Glycosylation gene panel (Fig. 3C, Table 4). Several genes involved in glycan synthesis or modification (MAMDC2, ST6GALNAC3, RENPP1) were upregulated in older tumors (log2FC values between 0.08–0.10), suggesting enhancement of glycosylation-related pathways with age. Notably, B3GNT6, a glycosyltransferase involved in core 3 O-glycan biosynthesis, showed higher expression in older tumors (log2FC = + 0.12; p = 0.069), consistent with emerging evidence linking O-glycan remodeling to age-related changes in the tumor microenvironment45. In contrast, the key sialyltransferase ST6GALNAC1 demonstrated reduced expression in older tumors (log2FC = -0.09), potentially affecting immune recognition and cell–cell adhesion in aged tissues46. Among all Glycosylation genes, MAMDC2 reached statistical significance (p = 0.0488) and may represent a novel age‐associated modulator of extracellular matrix organization in CRC.

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that aging has a category‐specific impact on transcriptional profiles in CRC tumors. Whereas younger tumors show stronger expression of chemokines and inflammatory mediators (CXCL5, SAA1/SAA2), older tumors display a shift toward kinase/phosphatase signaling (PPP2R2C), adaptive immune modulators (C8orf84) and glycosyltransferase activity (MAMDC2, B3GNT6). These age-dependent alterations highlight biologically meaningful pathways that should be considered when designing age-informed biomarker panels and therapeutic strategies in CRC.

Therapeutic gene signatures in younger CRC patients (< 70)

The Random Forest (RF) classifier using the top therapeutic genes achieved near-perfect discrimination of tumors vs normal tissue in younger patients. Cross-validation accuracy reached ~ 98% (permutation test P ≈ 0.01), indicating a highly significant model. The top-ranked features included THBS2, LRP8, and COL6A3 (Fig. 4A, Table 5). THBS2 encodes thrombospondin-2, an extracellular matrix glycoprotein that regulates angiogenesis, cell motility, and TGF-β activation47. High THBS2 expression is linked to colorectal tumor progression and poor prognosis47. LRP8 (ApoER2) is a lipoprotein receptor that can modulate Wnt and Reelin signaling, potentially influencing CRC cell migration and survival (as suggested by related LDL receptor family studies48). COL6A3 (Collagen VIα3) and other collagen genes (e.g. COL11A1) were also top features; these stromal components are frequently upregulated in CRC and enriched in pro-metastatic pathways (ECM-receptor interaction and focal adhesion)47. Additional important genes included DKC1 and APOLD1. DKC1 (dyskerin) is essential for telomerase and ribosome function, and it is often overexpressed in CRC, correlating with worse survival and angiogenesis via HIF-1α activation49. APOLD1 is an endothelial cell regulator of angiogenesis; notably, it is enriched in tumor vasculature, and its loss impairs neovascularization and tumor growth50. The inclusion of these genes suggests that younger CRC tumors are distinguished by a signature of extracellular matrix remodeling, telomere maintenance, and angiogenic signaling.

Age-stratified feature importance, differential expression, learning curves, and permutation tests for the Therapeutic gene set. (A, B) Top 10 Random Forest (RF) features ranked by impurity-based importance in the Young (< 70) and Old (≥ 70) age strata. Gene symbols correspond to RF-selected probes with the highest predictive contribution. (C, D) Volcano plots showing age-associated differential expression (log2 fold-change Old/Young vs. -log10(p)) across the transcriptome within each age group. The top 10 RF-selected genes are highlighted. (E, F) Learning curves for RF models trained on the top three features (RF Top-3) in each age stratum. Curves show mean balanced accuracy across outer folds (orange, ± SD) versus training set size, alongside training performance (blue), based on fivefold × 10-repeat nested stratified cross-validation. (G, H) Permutation testing results for the RF Top-3 models in each stratum. Histograms display the null distribution of balanced accuracies obtained from 100 label-shuffled permutations, with the observed score (red dashed line) plotted for comparison. P-values were calculated as the fraction of permuted accuracies equal to or exceeding the observed value, confirming statistical significance.

The volcano plot comparing gene expression between older and younger tumors (Fig. 4B) showed that most top features did not differ drastically by age. Points representing THBS2, COL6A3, and others lay near log2 fold-change 0 with P > 0.05, indicating similar expression in younger vs older patient tumors. A few genes (e.g. GAL, a neuropeptide, and PPP2R2C, a phosphatase subunit) showed modest age-related differences in expression (log2 FC ~ ± 0.2–0.3, P < 0.05), but these were not among the primary features. Thus, the predictive power of the therapeutic gene panel in young patients does not appear to be driven by age-biased expression.

Across all tasks, the RF learning curves showed training accuracy near ceiling and cross-validated accuracy that increased and then plateaued without divergence as sample size grew (Fig. 4E,F; Supplemetary Figs. 1-3E,F). This pattern, together with shallow trees and small leaves, is consistent with controlled capacity rather than memorization. Fold-to-fold feature ranks were stable (median Spearman ρ across outer folds reported in Table 5), indicating that the most informative genes recur across resamples. Finally, permutation tests that replicated the full nested pipeline yielded empirical p-values of 0.01 (N = 100), with the observed accuracies lying far to the right of the null distributions (Fig. 4G-H; Supplementary Figs. 1-3G-H). Collectively, these diagnostics support that the reported RF performance is not driven by overfitting. In addition to accuracy, Table 5 reports the mean macro-averaged OvR AUC (CV AUC OvR Mean), which reflects discrimination across all three classes simultaneously. This measure provides a balanced multiclass evaluation independent of class size differences.

Confusion matrix analysis confirmed excellent classification precision for younger patients (Fig. 4D). For the RF Top-10 model, normal mucosa samples were almost never misclassified as tumor, and vice versa. Specifically, 320/320 mucosa and 392/410 normal tissues were correctly identified, with only rare cross-labeling between normal and tumor classes. Tumors were identified with 98% sensitivity (401/410 correct, with 9 miscalled as normal). Using only 3 genes slightly reduced accuracy (more normal-tissue samples were mislabeled as tumor or mucosa, and tumor samples as normal) but overall performance remained high. The KTSP classifier (k-top scoring pair algorithm) achieved similarly high accuracy (~ 99% (Table 5)) with a different approach. Notably, the KTSP model even showed zero false tumor calls for normal tissue in this cohort, at the cost of a few more false-normal calls among tumors, effectively balancing sensitivity and specificity. In summary, for younger CRC patients the therapeutic gene signature yields outstanding diagnostic performance. A 10-gene RF model or KTSP model provides near-perfect classification, while a minimalist 3-gene model, including key drivers like THBS2, still generalizes well albeit with slight loss of precision. The involvement of genes tied to TGF-β signaling, apoptosis, and telomerase support the biological relevance of this signature in distinguishing colorectal tumors49.

Therapeutic gene signatures in older CRC patients (≥ 70)

In older patients, the therapeutic gene RF models also performed strongly, though with a slight decrease in accuracy relative to younger cohorts. The RF Top-10 model reached ~ 96% cross-validated accuracy (P = 0.01), whereas the top-3 gene model dropped to ~ 87% accuracy (Table 5). The top features for older patients (Fig. 4B) differed somewhat from younger ones, reflecting potential biological and microenvironmental differences in tumors arising later in life. The three highest-ranked genes were NR4A1, CDK4, and MACF1. NR4A1 (Nur77) is an orphan nuclear receptor and immediate-early gene that is overexpressed in multiple tumors including CRC; it can regulate apoptosis and T-cell exhaustion, for example by modulating PD-L1 expression51. Its prominence here may indicate that older tumors rely on immune-evasion pathways (NR4A1-mediated) more strongly. CDK4, a cell-cycle kinase, is a known oncogenic driver frequently dysregulated in CRC and a target of selective inhibitors. High CDK4 activity promotes unchecked G1/S cell cycle progression, consistent with the aggressive proliferation in tumors52.

MACF1 (Microtubule actin cross-linking factor 1) was another top feature unique to older patients. MACF1 is a cytoskeletal linker that plays a crucial role in Wnt/β-catenin signaling by facilitating the translocation of the Axin complex to the cell membrane48. Loss of MACF1 disrupts Wnt signaling and impairs β-catenin nuclear transport48, suggesting that high MACF1 levels in tumors support active Wnt signaling, a pathway central to CRC development48. The importance of MACF1 in older patients’ classifiers might reflect an accumulated reliance on Wnt pathway activation with age. Other notable genes in the older-top10 panel included EDN3 (Endothelin-3), a vasoactive factor possibly influencing tumor angiogenesis; CYR61 (CCN1), a matricellular protein that promotes angiogenesis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in CRC53; ITGA2 (Integrin α2), a collagen-binding integrin subunit that is often overexpressed in colon tumors and has been linked to invasion, 5-FU chemoresistance and upregulation of immune checkpoint ligand PD-L1 via STAT3 signaling52; and NONO, a DNA/RNA-binding protein implicated in DNA repair and androgen receptor signaling (its role in CRC is less defined but may involve regulating transcriptional responses). DKC1 and APOLD1 also appeared among the top 10 for older patients, similar to the younger group, indicating telomerase activity and pathological angiogenesis are consistently important across ages49.

The volcano plot for therapeutic genes (Fig. 4D) suggested a few age-related expression shifts: for instance, MACF1 and NR4A1 showed modest upregulation in tumors from older patients compared to younger (P < 0.05, log₂ fold-change > 0.2 favoring older), aligning with their increased feature importance in the older cohort. However, many top genes (e.g. CDK4, THBS2) were not significantly differentially expressed by age. This indicates that the classifier’s lower accuracy in older patients is not simply due to reduced gene expression differences, but perhaps due to greater phenotypic heterogeneity or overlap between normal and tumor samples in older individuals. Indeed, the confusion matrix for the RF Top-10 model in older patients (Fig. 4D) showed excellent overall accuracy (~ 96% (Table 5)), but with a slight increase in confusion between normal mucosa and adjacent normal tissue. Specifically, a subset of normal mucosa samples (∼14%) were misclassified as normal epithelium, and vice versa, more frequently than in the younger group. This trend could reflect age-related morphological changes in colonic mucosa that blur the distinction between “normal mucosa” and “normal-adjacent” tissue in gene expression profiles. Nonetheless, tumor samples in older patients were still identified with high sensitivity (~ 97%, only 19/570 tumors miscalled as normal in RF Top-10). The Top-3 gene model, in contrast, struggled with more confusion: e.g., ~ 41% of mucosa samples were misclassified when only NR4A1, CDK4, MACF1 were used, indicating that additional genes (like ITGA2, CYR61, etc.) are needed to capture the full spectrum of tumor-normal differences in older patients.

Comparing model variants, the KTSP classifier again matched the RF Top-10 performance in older patients, achieving ~ 99% accuracy (Table 5). Notably, the KTSP model appeared more adept at distinguishing mucosa from normal: only 1 mucosa sample was miscalled as normal (vs 25 in RF Top-10), yielding fewer false positives for tumor. This suggests that the pairwise expression logic of KTSP might capture subtle expression ratios that are consistent in older tissues even when absolute expression shifts with age. Meanwhile, the RF Top-3 model’s under-performance on external validation was pronounced (balanced accuracy ~ 81% in an independent cohort), underscoring that relying on just three genes can reduce diagnostic generalizability in older patients. In summary, the therapeutic gene signature remains highly effective for older CRC classification, but optimal performance requires a broader panel or robust algorithms. Age-related alterations in pathways like Wnt/β-catenin (MACF1) and immune signaling (NR4A1) may necessitate these additional markers. Importantly, many top genes in older patients (integrins, matricellular proteins) are involved in tumor-stroma interactions and inflammation, highlighting that the tumor microenvironment in elderly CRC plays a key role in distinguishing malignant from benign tissue52,53.

Immune gene signatures in younger CRC patients (< 70)

Using immune-related genes, we observed that young CRC patients’ tumors are well distinguished by an inflammation- and immune-signaling signature. The RF Top-10 immune-gene model achieved ~ 97% CV accuracy with permutation PValue = 0.01 (Table 5), comparable to the therapeutic results. However, in stark contrast to therapeutic genes, a model using only the top 3 immune genes dropped substantially in performance (CV accuracy ~ 87% (Table 5)). This suggests that immune signatures are highly multi-dimensional, and a broader panel is needed for robust classification. The most important features for young patients (Sup. Figure 1A) included CXCL12, IL6R, and C7, among others. CXCL12 (SDF-1) is a chemokine critically involved in tumor-stromal interactions; signaling through its receptors (CXCR4 and CXCR7) promotes tumor cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastasis in CRC54. Notably, CXCR7 (ACKR3) itself appeared in the therapeutic gene list for younger patients, reflecting the overlap between immune chemokine pathways and therapeutic targets. IL6R (Interleukin-6 receptor) mediates IL-6/STAT3 inflammatory signaling. This pathway is a known driver of colitis-associated colon tumorigenesis and cancer cell survival, inducing gene programs for proliferation and inhibition of apoptosis55. The prominence of IL6R in the young immune signature underlines the role of tumor-associated inflammation, younger patients may mount strong inflammatory responses that distinguish tumor tissue (with high IL-6 signaling) from normal mucosa. C7 (Complement C7) was also top-ranked, indicating complement cascade components differ between tumor and normal (potentially due to immune activation in tumor microenvironment). Additional top features were SECTM1 (Secreted and Transmembrane 1), a cytokine that costimulates T cells (through CD7) and is often upregulated in cancers; CEBPB and JUN, transcription factors that coordinate inflammatory and stress responses (AP-1 complex), which are activated downstream of cytokine signaling; CLDN1 (Claudin-1), a tight junction protein whose overexpression in CRC is linked to loss of barrier function and immune evasion; and EGR1, an immediate-early gene responsive to growth factors/stress. The inclusion of GAL (galanin) and GEM in the top 10 was noteworthy as well (GAL encodes a neuropeptide that can modulate intestinal motility and perhaps tumor) nerve interactions, while GEM encodes a small GTP-binding protein linked to calcium signaling; their exact roles in CRC are less characterized, but they may reflect the neuroimmune crosstalk in the tumor milieu.

The immune gene volcano plot for younger patients (Sup. Figure 1C) showed no single gene with massive age-biased expression; instead, a broad swath of immune genes was moderately upregulated in tumors of young patients compared to normal, consistent with an “inflamed tumor” phenotype. Key cytokines and chemokines (IL6, CXCL family) were generally elevated in tumors irrespective of patient age, so age < 70 vs ≥ 70 did not yield significant differences for these top markers (P > 0.1 for CXCL12, IL6R).

The model utilizing the top 3 features achieved a strong overall accuracy of 92.2% shown in the confusion matrices (Sup. Figure 1C,D). This classifier demonstrated good predictive capability but showed notable misclassifications between classes. Specifically, it correctly identified tumor tissue with 95.6% recall but confused some tumor and normal samples in both directions. In a marked improvement, the model trained in the top 10 features yielded a superior overall accuracy of 97.0%. This classifier showed a substantial reduction in errors across all categories. Its ability to identify Tumor tissue was outstanding, with recall increasing to 98.3%. Critically, misclassifications involving the tumor class were nearly eliminated, and the confusion between normal and mucosa tissues was also significantly reduced.

The KTSP classifier using the immune gene set reached ~ 98% accuracy (Table 5), slightly outperforming RF Top-10 in the validation set (97% vs 93% accuracy). KTSP’s pairwise approach may effectively capture complex immune expression patterns (for instance, a rule comparing IL6R and C7 expression could flag tumors even if one marker alone is variable). Notably, KTSP yielded very few false negatives in young patients, it correctly identified almost all tumors, emphasizing its utility in a diagnostic setting were missing a tumor (false negative) is especially costly. Altogether, the immune gene signature in younger CRC patients highlights that tumors can be recognized by their immunological footprints: elevated pro-inflammatory cytokine signaling (IL-6/STAT3 pathway55), chemokine axes (CXCL12/CXCR4-CXCR7 54), and downstream transcriptional responses (AP-1, C/EBPβ). These pathways underscore the interplay between cancer and the immune system in younger individuals. The superior performance of broader gene panels suggests that capturing the full complexity of tumor immune evasion and inflammation requires multiple markers, aligning with the multifaceted nature of cancer immunology.

Immune gene signatures in older CRC patients (≥ 70)

In the older (≥ 70) patient group, the immune gene signature yielded even higher performance. The RF model with the top 10 immune genes was nearly perfect, with a cross-validated accuracy of about 99% and a macro-average AUC ~ 0.999 (permutation p = 0.01) (Table 5). This indicates that in older patients the immune-related expression differences between tumor and normal tissues are extremely pronounced or consistently captured by the signature. The 3-gene RF model, while still effective, had a lower accuracy (~ 93%, AUC ≈0.98, p = 0.01) in the older group, misclassifying a few samples. These misclassifications again tended to occur between normal tissue vs. mucosa or occasionally classifying a tumor as normal when using the limited 3-gene set. Nonetheless, even the top-3 gene model performed far above chance, indicating that a small subset of immune genes still carries significant signal in older patients.

The top-3 feature model achieved a strong accuracy of 93.0%, but it exhibited a critical weakness in distinguishing between Tumor and Normal tissues, notably misclassifying 44 true Tumor samples as Normal, shown in the confusion matrix (Sup. Figure 2C,D). In stark contrast, the top-10 feature model demonstrated exceptional performance, boosting the overall accuracy to 98.7%. This enhanced model achieved perfect classification for the Mucosa class and drastically reduced the number of critical errors, with the misclassification of Tumor as Normal samples dropping from 44 to 15. These results clearly indicate that the 10-feature model provides a significantly more robust and reliable classifier for this cohort, nearly eliminating the confusion between tissue types.

As with the younger cohort, the KTSP classifier on the immune signature achieved ~ 99% accuracy and a high AUC (~ 0.998) in the older group, matching the RF top-10 model’s performance. This consistency across modeling approaches underlines that the immune signature is highly predictive in ≥ 70 patients. Key genes contributing to the classifier for older patients included cytokine signaling genes such as IL6R and immediate-early response genes like FOS, among others, which may reflect age-related immune-expression patterns that distinguish tumor from normal tissue. Overall, the immune-based model maintains excellent performance in both age strata, with the 10-gene panel performing near-flawlessly (especially in older patients) and the 3-gene subset still providing substantial, albeit reduced, classification power.

Glycosylation gene signatures in younger CRC patients (< 70)

For the Glycosylation-related gene signature, the RF classifier with the top-10 genes achieved strong classification performance in younger patients, though slightly lower than the immune signature. The top-10 gene glycosylation model reached approximately 94% cross-validated accuracy (AUC ~ 0.98, p = 0.01), correctly distinguishing most tumor vs. normal samples in the < 70 cohort. Its confusion matrix indicates only a few mistakes; for example, a small number of normal tissue samples might be labeled as tumor or vice versa, but most of both classes are correctly identified (Supplementary Fig. 4A). In contrast, using only the top 3 glycosylation genes led to a more noticeable drop in accuracy (~ 89%, AUC ~ 0.96, p = 0.01). This 3-gene model still performed significantly better than randomly, but its confusion matrix reveals more frequent misclassifications compared to the 10-gene model. Some tumor samples were misclassified as normal in the younger group (and/or normal as tumor) when only three glycosylation genes were used, suggesting that these few markers did not capture the full complexity of glycosylation changes in the tumor. The KTSP classifier using glycosylation genes yielded ~ 96% accuracy (AUC ~ 0.990) in the young cohort (on par with the RF 10-gene model) indicating that the glycosylation signature is indeed informative for distinguishing tumor from normal tissues. However, the gap between the 3-gene and 10-gene performances was more pronounced for the glycosylation category (compared to the immune signature), implying that a broader panel of glycosylation-related genes is especially important for robust classification in younger patients.

The top features for younger patients included enzymes and proteins involved in glycan modification: GCNT2, GALNT6, and LYVE1 were among the highest-ranked (Sup. Figure 3A). GCNT2 encodes β1,6-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase 2, known as the I-branching enzyme, which creates branched I-antigen structures on glycans. I-branched glycoepitopes (catalyzed by GCNT2) are increasingly recognized as effectors of malignancy56, and GCNT2 dysregulation has been linked to cancer cell invasiveness. GALNT6 (polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 6) initiates mucin-type O-glycosylation; notably, GALNT6 is highly upregulated in colorectal adenocarcinoma tissue but absent in normal colon epithelium57, making it an excellent tumor marker. High GALNT6 activity can alter cell adhesion and has been shown to promote an aggressive phenotype in other cancers (e.g. via O-glycosylating and stabilizing pro-survival proteins57). Other top genes included GLTPD1 (glycolipid transfer protein domain containing 1), which may influence glycolipid composition of membranes; LYVE1, a lymphatic endothelial receptor for hyaluronan often found at elevated levels in tumor-adjacent stromal cells (potentially indicating increased lymphangiogenesis or altered glycosaminoglycan metabolism in tumor microenvironment); COL11A1, an extracellular matrix collagen that was also enriched in the therapeutic signature (its high expression in tumors correlates with aberrant collagen glycosylation and fiber organization47); LDLR (low-density lipoprotein receptor), which is heavily glycosylated and upregulated in many cancers to support cholesterol uptake, thereby indirectly reflecting changes in glycosylation and metabolism in tumors; and GNPDA1 (glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminase 1), an enzyme in the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway that provides substrates for N-linked glycosylation, higher GNPDA1 might signal a reprogramming of glucose metabolism toward anabolic processes in tumors. FOXC1, a transcription factor not classically associated with glycosylation, also appeared among top features, possibly because it regulates expression of certain glycosylation enzymes or interacts with Wnt signaling (FOXC1 has been linked to EMT and may modulate extracellular matrix components).

Glycosylation gene signatures in older CRC patients (≥ 70)

In older patients, the glycosylation signature classifier performed exceptionally well, similar to the immune signature results. The RF model using the top 10 glycosylation genes achieved ~ 94% accuracy in cross-validation (AUC ~ 0.994, p = 0.01) for ≥ 70 patients, indicating excellent predictive ability (Table 5).

According to the confusion matrix (Sup. Figure 4B), the model was exceptionally effective at identifying Tumor and Normal tissues. It classified the Tumor class with 98.6% recall and 99.1% precision, indicating a very low rate of both false negatives and false positives. The Normal class was also identified with high accuracy, achieving 97.9% recall. The majority of the model’s misclassifications were related to the Mucosa class, which had a lower recall of 86.1%. The primary source of error was the model misclassifying “Mucosa” samples as “Normal”.

Using the top 3 glycosylation genes in the RF model resulted in about 89% accuracy (AUC ~ 0.96, p = 0.01) for the older group, reflecting a slight decline in performance. The 3-gene model’s confusion matrix shows glycosylation features achieved an overall accuracy of 89.9% (Sup. Figure 4D). While the model retains some predictive capability, its performance is significantly compromised compared to the model using more features. The most critical issue is the substantial confusion between the Tumor and Normal classes. The model misidentified 44 true “Tumor” samples as “Normal” (a recall of 91.6%) and misidentified 48 true “Normal” samples as “Tumor”. This two-way confusion between the most critical classes indicates that reducing the feature set to only the top 3 has severely diminished the model’s clinical utility and reliability (Fig. 5).

Age‐stratified classification performance: confusion matrices for RF and KTSP models (Therapeutic gene set). Confusion matrices show the distribution of correctly and incorrectly classified samples across three sample types (Mucosa, Normal, Tumor) in the young and old age groups. (A, B, C, D, E, F) display Random Forest models trained with the top 10 and top 3 features and the multiclass KTSP model, respectively. Color intensity reflects absolute sample counts, with darker tiles representing higher counts.

Consistent with the other analyses, the KTSP method reached ~ 97% accuracy (AUC ~ 0.99) in the ≥ 70 cohort, essentially mirroring the RF’s top-10 gene performance. A summary of the glycosylation model performances is provided in Table 5. Taking together, these results demonstrate that the glycosylation-related gene signature is highly effective for classifying tumor versus normal tissue in both younger and older patients, although, as with the immune signature, the full 10-gene panel provides a noticeable boost in accuracy over the minimal 3-gene set.

External validation

In the young (< 70) group, both the RF Top-10 model and the KTSP classifier (Fig. 6I-K) were exceptionally accurate (Fig. 6A,C). The RF model achieved an AUC of 0.980 with only one misclassification, while the KTSP model was even slightly better with a near-perfect AUC of 0.989. The RF Top-3 model (Fig. 6E, G) also performed very well (AUC 0.965), though it was clearly a step behind the other two.

External validation of age-stratified classifiers using independent GSE106582 dataset. (A) Confusion matrix of the Young (< 70) RF Top-10 classifier applied to the batch-corrected GSE106582 dataset. (B) Confusion matrix of the Old (≥ 70) RF Top-10 classifier applied to the same dataset. (C) ROC curve of the Young RF Top-10 model (macro-averaged across classes). (C) Macro-averaged ROC curve of the Young RF Top-10 model. (D) Macro-averaged ROC curve of the Old RF Top-10 model. (E) Confusion matrix of the Young KTSP classifier applied to GSE106582. (F) Confusion matrix of the Old KTSP classifier. (G) Macro-averaged ROC curve of the Young KTSP model. (H) Macro-averaged ROC curve of the Old KTSP model. Dashed orange diagonal indicates performance of a random classifier (AUC = 0.5).