Abstract

Nickel (Ni) use in agriculture has expanded, especially the foliar application of this micronutrient, which has had positive effects on the health and grain yield of several crops. Thus, critical levels of the element in the leaves and the optimal dose for the maize crop need to be identified. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of foliar application of Ni doses on gas exchange, nutrition, biochemistry, physiology and grain yield of maize plants. Field experiments were carried out in randomized block design with four replicates and five doses of foliar Ni fertilizing: 0; 20; 40; 80 and 160 g ha- 1, divided into two applications, totaling 20 plots. A single application of Ni increased the total chlorophyll content by 38% with 70 g ha- 1 Ni in year I and 44% in year II when 80 g ha- 1 Ni was applied. Photosynthesis also improved, increasing by 46% in year I and 45% in year II. Ni content in the leaves varied from 1.02 to 3.35 mg kg- 1 in year I and from 0.33 to 6.32 mg kg-¹ in year II, while the content in the grains increased from 0.68 to 1.03 mg kg-¹ Ni in year I and from 0.13 to 1.05 mg kg- 1 in year II. Yield peaked at 46.50 g ha- 1 Ni in year I and 92.50 g ha- 1 in year II, increasing grain yield by 15.62% and 5%, respectively, compared to the control (no Ni). The appropriate range of Ni in the leaves was 1.29 to 1.86 mg kg-¹ in year I and 1.40 to 3.60 mg kg-¹ in year II, with toxic levels above 2.43 mg kg-¹ and 5.80 mg kg-¹, respectively, reducing grain yield by approximately 32% in year I and 6% in year II. Overall, foliar Ni fertilization improved photosynthesis and grain yield when applied within moderate ranges, although the magnitude of the response varied substantially between years. These results indicate that Ni use in maize should not rely on a single fixed dose but should instead be calibrated according to environmental conditions and crop responses. Grain Ni levels remained within acceptable limits, reinforcing that moderate foliar Ni application can be used safely when properly managed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nickel (Ni) is the most recent element recognized as essential for higher plants1. It plays a pivotal role in nitrogen (N) metabolism and can enhance crop yield2,3. In maize, Ni has been associated with improved photosynthetic activity and electron transport in chloroplasts4. Its importance in plant mineral nutrition is firmly established through its role as the metal cofactor of the enzyme urease5. Urease contains two Ni²⁺ ions in its active site and catalyzes the hydrolysis of urea to ammonia (NH₃) and carbon dioxide (CO₂), enabling plants to utilize both internally and externally derived urea as an N source.

Nickel deficiency compromises central metabolic processes and may depress crop productivity. In soybean, supplying small amounts of Ni increased urease activity and translated into yield gains across genotypes under greenhouse and field conditions6. In barley, Ni deficiency prevented grain formation and caused severe losses7. Beyond its metabolic role, adequate Ni supply can contribute to crop health, reducing pesticide needs and supporting performance8. Field evidence also associates Ni fertilization with yield gains9,10; in barley, foliar Ni increased both grain yield and tissue Ni accumulation8. Because Ni is mobile within plant tissues but often sparingly available in the soil, foliar fertilization is an efficient strategy to meet plant demand11.

While optimal Ni supply supports ureide metabolism and photosynthesis, excess Ni disrupts key biochemical and physiological processes, lowering photosynthetic rate and pigment levels12. In maize, Ni toxicity has been reported to decrease total chlorophyll and gas-exchange variables via enzyme inhibition, impaired stomatal function, disruption of photosynthetic electron transport, and chlorophyll degradation, ultimately reducing photosynthesis and biomass production13,14. These contrasting responses highlight the need to define agronomically effective yet safe Ni rates.

Despite its recognized importance, practical guidance for Ni fertilization under field conditions remains limited. Critical information on sources, timing, rates, application methods, and physiological thresholds is still scarce. Evidence indicates that soil application of micronutrients can show low plant recovery due to losses by leaching, erosion, or immobilization, often demanding higher inputs15. Consequently, foliar Ni fertilization has gained prominence in experimental studies16 and is already adopted by farmers for micronutrient management, typically requiring lower doses than soil application and thereby reducing the risk of toxicity17. In maize, foliar application of nickel sulfate (NiSO₄) has been reported to enhance nutrient uptake and promote growth, increasing biomass accumulation and grain yield18.

From a food-safety perspective, Ni is a heavy metal, and excessive intake poses risks to human and animal health19,20,21. Thus, agronomic recommendations should balance the physiological benefits of Ni with environmental and food-chain safety, avoiding rates that could elevate grain Ni to undesirable levels.

We hypothesized that appropriately dosed foliar Ni increases gas exchange and grain yield in maize, whereas higher rates induce toxicity that compromises physiological variables, yield, and grain Ni concentrations.

This study aimed to (i) evaluate the effects of foliar Ni fertilization on gas exchange and grain yield in maize and (ii) identify an agronomically appropriate Ni rate that optimizes plant nutrition, biochemistry, and physiology while avoiding toxicity.

Materials and methods

Location of the experimental area and climate

Field experiments were carried out in the second harvest of 2022 and 2023 at the experimental area of the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS), campus of Chapadão do Sul, located between the geographical coordinates 18°46’16” S latitude and 52°37’22” W longitude and average altitude of 820 m. According to the Köppen classification, the predominant climate in the region is tropical humid (AW), with a rainy season in summer and a dry season in winter.

During the year I experiment, the average temperature was 16.14 °C. Minimum and maximum precipitation was 4.0 mm and the 40 mm, respectively, with a total of 370.5 mm distributed over 22 days, an amount below that required for the proper development of maize plants, which varies between 380 and 550 mm2. In the year II experiment, the minimum rainfall was 0.20 mm and the maximum was 107 mm, which totaled 578.53 mm over 51 days of rain, more than the amount needed for the proper development of maize plants.

Soil in the experimental area and chemical properties

The experiment was carried out on a dystrophic red-yellow Latossolo22. Before setting up the experiment, the soil was sampled in the 0 to 0.2 m depth layer using a Dutch auger, a standard approach established to soil analysis in crops such as maize23. Twelve simple samples were collected at random points in the experimental area to make up a composite sample. Chemical analysis was then carried out for fertility and granulometric purposes (sand, silt and clay)12,24. The results of the granulometry analysis were: 465, 50 and 485 g kg- 1 of clay, silt and sand, respectively, which means that the soil has a sandy clay texture.

Data obtained from the chemical analysis showed the following results: pH CaCl2 = 5.1; Al = 0.07 cmolc dm- 3. Macronutrients: Ca = 4.30 cmolc dm- 3; Mg = 1.00 cmolc dm- 3; K = 0.31 cmolc dm- 3; P (mel) = 39.6 mg dm- 3; S = 14.2 mg dm- 3. Micronutrientes: B = 0.28 mg dm- 3; Cu = 1.4 mg dm-3, Fe = 53 mg dm- 3, Mn = 14.9 mg dm- 3, Zn = 4.8 mg dm- 3; Organic matter (OM) = 31.9 g dm- 3; organic carbon (CO) = 18.5 g dm- 3; cation exchange capacity (CEC) = 11.7 cmolc dm- 3; Base saturation = 47,9%. Ratio between bases: Ca/Mg = 4.3; Ca/K = 13.9; Mg/K = 3.2. Ni content in the soil was low: < 1.0 mg kg-1 by the EPA 3050B method and < 0.2 mg kg- 3 in Mehlich125.

Experimental design, establishment, and crop management

A randomized block design was established with five foliar Ni rates (0, 20, 40, 80, and 160 g ha-¹ Ni, applied in two equal splits), with four replications, totaling 20 plots. Each plot consisted of six 6-m rows spaced 0.50 m apart, with the useful area defined as the four central rows, excluding 1.0 m at both ends. The inclusion of the upper rate (160 g ha-¹ Ni) ensured that the experimental gradient encompassed the full physiological response spectrum of maize to foliar Ni, allowing the identification of both beneficial effects and early signs of stress. This wide dose range reflects current recommendations for studies aiming to characterize diagnostic thresholds for Ni in crops17.

The hybrid ‘P3858PWU’ was sown in the year I experiment (February 24, 2022) and the year II experiment (February 10, 2023), and the seeds were treated with the fungicide Ipconazole 450 g L- 1 or 45% (rate of 0.056 mL ha- 1 per kg of seeds), Fludioxonil 25 g/L - Metalaxyl-M 10 g/L (rate of 1.5 mL ha- 1 per kg of seeds), and the insecticides Deltamethrin 25 g/L (rate of 0.08 mL kg- 1 per kg of seeds) and Pirimiphos-methyl 500 g L- 1 (rate of 0.016 mL ha- 1 per kg of seeds).

500 kg ha- 1 of formulated 08-28-16 (N, P, K) was applied in the planting furrow + 2 kg ha- 1 of boron (borax 15%) was applied in the total area after sowing. Two top dressings were applied, one at phenological stage V4 (four fully expanded leaves with visible collars) and the other at stage V6 (six fully expanded leaves with visible collars), using urea as the nitrogen source and potassium chloride (KCl) as the potassium source.

At V4 and V6, 90 kg ha- 1 of N and 45 kg of K2O per ha- 1 were applied26. Still at V4, a 0.5% solution of Zn sulphate and Mn sulphate was applied by foliar application, with a spray volume of 300 L ha- 1. After the first top-dressing nitrogen fertilization, a foliar molybdenum fertilization was carried out using 100 ml ha- 1 of sodium molybdate (15.5% Mo) in 100 L of water as the spray volume. These micronutrients were supplied as a supplement to soil fertilization because maize has a high demand for Zn and Mn, which are essential for N metabolism, photosynthesis, and antioxidant defense. They were applied uniformly across all plots, including the control, to avoid confounding Ni effects. After the first nitrogen topdressing, molybdenum (Mo) was applied as a foliar spray (100 mL ha⁻¹ sodium molybdate, 15.5% Mo, in 100 L of water), with sodium serving only as the counter‑ion of the source. Molybdenum was likewise applied uniformly to all plots to enhance nitrogen use efficiency, ensuring that only the Ni treatments remained as the variable factor.

Ni sulphate (NiSO₄(H₂O) ₆) was used as a source of Ni by foliar application 5 days after each nitrogen top dressing. Thus, each rate of Ni was divided into two applications, half at phenological stage V4 and the other half at V6. For this purpose, a backpack sprayer was used with an aluminum cylinder with a 2 kg CO2 capacity, pressure regulator, pressure gauge, from 0 to 100 psi, safety valve, and an application bar with 4 nozzles, calibrated for a flow rate of 150 L ha- 1, using a pressure of 2.5 bar and TTI60-110025 TeeJet® tips. 1 ml/L of vegetable oil was added to all applications.

The recommended rate of 500 kg ha- 1 08-28-16 was applied. Applications were carried out at the V4 phenological stage with the herbicide Glyphosate (588 g L- 1); at V4 and V8 with the insecticides Thiamethoxam (141 g L- 1) and Lambda-Cyhalothrin (106 g L- 1); and at V6 with the insecticide Methomyl (215 g L- 1). Furthermore, fungicides were applied as follows: 300 mL ha- 1 of Azoxystrobin (200 g L- 1) and Cyproconazole (80 g L- 1) at 40 days after sowing, and 500 mL ha- 1 of Azoxystrobin/Flutriafol (125 g L- 1) at 60 days after sowing.

Analysis of photosynthesizing pigments

The chlorophyll cha + b content was determined by sampling 6 leaves per plot. The pigment contents were determined by taking 0.04 g of fresh leaf samples, adding them to test tubes with 5 mL of acetone (80%) for the extraction of photosynthetic pigments, and leaving them to cool for around a week. Afterwards, the extracts were measured using a spectrophotometer (model TU-1810) 27. All the physiological evaluations were carried out at the same phenological stage as the VT (tasseling), on the first fully developed leaf with a visible sheath.

Gas exchange

At full flowering, net photosynthesis (A, µmol CO₂ m-² s-¹) was measured using a portable photosynthesis system (Infrared Gas Analyzer-IRGA, LI-6400XT; LI-COR Inc., Lincoln, Nebraska, USA). Before each measurement period, the instrument was calibrated according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, including zero and span calibration of the CO₂ and H₂O analyzers, adjustment of airflow to 500 µmol s-¹, and verification of chamber sealing to avoid leaks. The photosynthetically active photon flux density was set at 1200 µmol m-² s-¹, and the reference CO₂ concentration was maintained at 372 ± 10 µmol mol-¹, following procedures commonly used for gas exchange measurements in maize28.

In both growing seasons, measurements were performed between 08:00 and 11:00 a.m. on cloudless days, with air temperature ranging from 24 to 28 °C and relative humidity between 50 and 80%. One plant per experimental unit (n = 20 per season) was evaluated, using the fully expanded flag leaf, which is widely recognized as the diagnostic leaf for physiological assessments in maize.

Leaf diagnosis

The first leaf opposite the base of the main ear of each plant was collected at full bloom. Leaves were washed in running water with 0.1% neutral detergent solution, 0.3% HCl solution, and deionized water29. The leaves were dried in a forced-air oven (65 ± 5 °C) until constant weight, and the dry matter of the maize leaves was obtained. The methodology 30 was used to determine leaf Ni content.

Foliar Ni diagnosis was carried 29 by considering grain yield as a function of Ni content in plant tissue. Four response ranges to foliar Ni application were established, i.e., the deficiency range (foliar Ni levels equivalent to grain yields of less than 95%), the adequate range (foliar Ni levels between 95% and 100% of maximum yield), the critical toxicity level (foliar Ni levels equivalent to 5% yield loss) and the toxicity range (foliar Ni levels resulting in yield losses exceeding 5%). Data was fitted using the Lorentz equation (three parameters)31. Appropriate Ni levels were plotted on the grain Ni content graph to identify the respective levels and check whether they did not reach toxic levels for food, based on reference values in the literature.

Grain yield and nutritional analyses

At the end of the maize cycle, grain yield was assessed by harvesting and threshing the useful sampling area of each plot. Moisture content of the grains was corrected to 13% and impurities were deducted, and then the yield results were expressed in kg ha- 1.

After estimating the yield per plot, the harvested grains were dried in a forced-air oven (65 ± 5 °C) until they reached a constant weight to determine the dry mass of the grains. The methodology 30 was used to determine Ni content in the grain.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Rbio software. Data normality was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk W-test. Regression models were fitted using the least-squares method, and the significance of both models and coefficients was assessed by ANOVA (p ≤ 0.05). Before model fitting, the assumptions of normality, homoscedasticity, and independence of residuals were verified. Significant variables were further analyzed using regression at the 5% probability level, and the corresponding plots were generated. The standard error of the mean (± SE) was used to construct the error bars displayed in the figures. Canonical discriminant analysis was performed to assess the association patterns between treatments and the evaluated variables.

Results

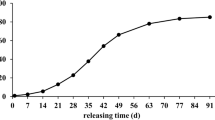

All fitted regression models were statistically significant (p < 0.05) and exhibited adequate model fit, as indicated by their R² values. These metrics are displayed directly in each figure together with the corresponding regression equations. The results for total chlorophyll, photosynthesis, Ni content in the leaf, Ni content in the grain, and grain yield in both years (2022 and 2023) were significant. By means of regression analysis, data were adjusted to the quadratic model as Ni levels increased. For total chlorophyll (mg g- 1 Fresh mass) in year I, Ni content had a significant influence on increase in cha + b, reaching the maximum point at 70 g ha- 1 Ni, which represents an increase of up to 37% compared to the control (Fig. 1a). In year II, the best treatment was 78.5 g ha-¹ Ni, which increased grain yield by 43% compared with the control (Fig. 1b).

Net photosynthesis (A) (µmol CO2 m- 1 s- 1) in year I increased to a maximum at 84.10 g ha- 1 Ni, which corresponded to a 46% increase over the control (Fig. 1c). A means increased up to a maximum at 83.69 g ha- 1 Ni in year II, which represented a 45% increase over the control (Fig. 1d).

Total chlorophyll content (Cha + b) in year I (a), total chlorophyll content (Cha + b) in year II (b), photosynthesis (A) in year I (c) and photosynthesis (A) in year II (d) of maize plants grown under foliar-applied Ni doses divided into two applications. Ni content in leaf and grain. Vertical bars represent the standard error of the mean (± SE).

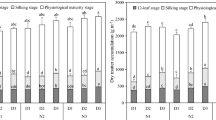

Using regression analysis, data were fitted to a linear model as Ni doses increased. Leaf Ni concentration increased significantly (p < 0.05) with Ni application, reaching 3.35 mg kg-¹ in year I and 6.32 mg kg-¹ in year II at the highest rate (160 g ha-¹) (Figs. 2a, b). Similarly, grain Ni concentration increased significantly (p < 0.05), from 0.68 to 1.03 mg kg-¹ in year I and from 0.13 to 1.05 mg kg-¹ in year II (Figs. 2c, d).

Ni content in leaves for the year I (a), Ni content in leaves for the year II (b), Ni content in grain for the year I (c), and Ni content in grain for the year II (d) of maize plants grown under foliar-applied Ni doses divided into two applications. Vertical bars represent the standard error of the mean (± SE).

Grain yield in year I peaked at a dose of 46.50 g ha− 1 Ni, with a 15% increase compared to the control (Fig. 3a). In year II, the peak was at 92.50 g ha− 1 Ni, with a 5% increase compared to the control (Fig. 3b).

Ni foliar diagnosis

Four areas of response to the foliar Ni application were established 29. Firstly, for the deficiency range, in which foliar levels are interpreted as deficient, Ni doses increased grain yield, even though the plants did not show deficiency symptoms for this micronutrient. The second range was that in which the levels are interpreted as adequate, in which the plants have reached their maximum yield. Lower limit was set at 95% of the maximum yield and the upper limit at 100% of the maximum yield. At the appropriate range in the first year (Fig. 4a), Ni content ranged from 1.29 to 1.86 mg kg− 1, corresponding to foliar application from 14.6 to 57.7 g ha− 1 Ni. In the second year (Fig. 4b), still at the appropriate level, the Ni concentration in the leaves ranged from 1.40 to 3.60 mg kg− 1, corresponding to foliar application from 35.0 to 92.5 g ha− 1 of Ni.

The third range, considered to be the critical level of toxicity, was that which led to a 5% decrease in grain yield, where the Ni content is interpreted as high. The fourth area corresponded to the toxicity range, where Ni levels are interpreted as toxic and caused a decrease exceeding 5% in grain yield, i.e., values higher than 2.43 mg kg− 1 in the first year and 5.80 mg kg− 1 in the second year, corresponding to 100.8 g ha− 1 and 150.5 g ha− 1 Ni, respectively. This finding indicates that, within this range of leaf Ni content, the maize plants uptake a sufficient amount of Ni to maximize their grain yield, without entering deficiency or toxicity ranges (Fig. 4a). In the second year, the plants demonstrated a higher tolerance to higher leaf Ni contents (Fig. 4b).

Relationship between leaf Ni content and grain yield of maize plants grown under different foliar fertilizer doses (0, 20, 40, 80 and 160 g ha[- [1 Ni, divided into two applications), for visual Ni diagnosis. Vertical bars represent the standard error of the mean (± SE).

The canonical discriminant analysis showed that Can1 accounted for 85.2% of the total variation, while Can2 explained 12.7% (Fig. 5). The treatment with 160 g ha⁻¹ was clearly separated in the positive direction of Can1 and was associated with higher nickel concentrations in both leaf and grain. The treatments 0 and 20 g ha-¹ remained near the origin of the axes, indicating similar responses. The treatment with 40 g ha⁻¹ was positioned in the negative direction of Can1 and showed the strongest association with grain yield (PROD), as indicated by the vector oriented in this direction. The treatment with 80 g ha-¹ grouped in the lower-left quadrant and was primarily associated with the photosynthetic rate (A). These results indicate consistent differences among foliar Ni doses in the physiological and nutritional responses of maize.

The canonical discriminant analysis revealed that Can1 accounted for 66.7% of the total variation, and Can2 explained 28.2% (Fig. 6). The treatment with 160 g ha−¹ was clearly separated on the positive side of Can1, strongly associated with higher nickel concentrations in the leaf (Nifolha) and grain (Nigrao). The treatments 0 and 20 g ha−¹ clustered on the negative side of Can1 and in the positive region of Can2, indicating similar responses and a stronger association with the variables positioned in this direction. The treatment with 40 g ha−¹ was located near the origin of the axes, indicating an intermediate response pattern. The treatment with 80 g ha−¹ formed a distinct cluster in the lower-left quadrant, showing a closer association with photosynthesis (A), total chlorophyll content (Chab), and grain yield (PROD), as indicated by the orientation of the respective vectors. Overall, the analysis demonstrates clear differentiation among the foliar Ni doses, highlighting that 160 g ha−¹ is primarily linked to Ni accumulation, whereas 80 g ha−¹ shows greater association with physiological performance.

Discussion

The present study provides field-based evidence that foliar Ni fertilization, when applied within a relatively narrow range of doses, can simultaneously enhance photosynthetic performance and grain yield in maize while defining physiologically meaningful diagnostic thresholds for Ni deficiency and toxicity. Rather than focusing solely on yield responses, our results integrate gas exchange, pigment status, leaf and grain Ni accumulation, and canonical discriminant analysis to characterize how maize plants functionally respond to increasing foliar Ni supply under contrasting climatic conditions. This integrated approach helps to bridge the gap between mechanistic studies on Ni metabolism and the practical need for agronomic guidelines on Ni use in cereal-based production systems.

Effects of Ni on photosynthesis and pigments

In our study, a typical biphasic response pattern to foliar Ni supply was observed, in which intermediate doses stimulated chlorophyll accumulation and photosynthesis, whereas higher doses were associated with marked declines in both variables. This bell-shaped behavior reflects the dual role of Ni as an essential cofactor at low concentrations and as a potential pro-oxidant when supplied in excess. Similar patterns have been reported in soybean, barley, rice and maize, where low to moderate Ni inputs promote urease activity, N metabolism and pigment maintenance, while excessive Ni triggers oxidative stress, degradation of chlorophyll and inhibition of gas exchange4,6,13,18,31,32. Such contrasting responses highlight that the beneficial-toxic window for Ni in plants is intrinsically narrow and strongly influenced by environmental and management conditions.

Ni acts on enzymes that participate in the photosynthetic pathway, such as Rubisco and Aldolases32. Rubisco is responsible for carboxylating the carbon dioxide molecule during photosynthesis and is considered a key enzyme in this process, because it is responsible for fixing atmospheric carbon and hence synthesizing carbohydrates. In short, Ni can affect the carboxylation efficiency and consequently the carbohydrate synthesis in plants, which in turn can have a significant impact on yield and agricultural sustainability.

It is known that high Ni levels in plant tissues can inhibit photosynthesis and respiration33. Ni toxicity symptoms can be related to tissue lesions, growth retardation, and chlorosis. An excess of this micronutrient in plant leaves leads to changes in the photosynthetic pigment concentration, which results in leaf necrosis and chlorosis18, as well as effects on mitotic and enzymatic activity34.

Although adequate foliar Ni can enhance physiological performance and yield, as observed in our study, these positive effects are not universal across environments and crops. Evidence from soybean and barley indicates that the magnitude of Ni responses varies widely depending on soil properties, background Ni availability, and climatic conditions, with some studies reporting modest or inconsistent yield effects even under low-Ni scenarios6,8,17. This variability underscores the need to interpret Ni responses in maize within an environmental and physiological context rather than relying solely on numerical dose-response estimates.

Recent studies of Ni fertilization in soybean reinforce that the physiological benefits of Ni are not consistently accompanied by gains in growth or yield. In a multi-environment study comparing seed, soil and foliar Ni applications, a previous study17 showed that leaf-applied Ni increased chlorophyll status, photosynthesis and N metabolism but did not enhance plant height or grain yield, concluding that reported benefits of Ni in the literature may or may not translate into productivity gains.

Similar behavior was observed in a previous study34, which found that soil-applied Ni strongly increased leaf urease activity in lettuce grown on a Ni-deficient Oxisol without affecting shoot dry matter, indicating that Ni can correct metabolic constraints while leaving biomass unchanged. Genotype-dependent responses are also evident: in a two-environment trial with 15 soybean cultivars, another study35 reported that soil Ni fertilization enhanced grain yield in most genotypes under greenhouse conditions but in only a small subset in the field, even though N metabolism improved broadly. From the edaphic perspective, a separate investigation35 demonstrated that in intensively cultivated alluvial soils the water-soluble plus exchangeable and organically bound fractions represent only a minor portion of total Ni, yet these are the fractions most closely related to plant uptake, while residual and Mn-oxide-bound Ni remain largely unavailable. Another study37 further highlighted that soil pH, texture and organic matter, through their control of Ni sorption and leaching, strongly modulate Ni availability to crops. Together, these studies support the view that Ni fertilization tends to produce context-dependent responses, in which improvements in physiological traits are common but robust yield gains occur only under specific combinations of genotype, soil and climate.

Altogether, current evidence shows that crop responses to Ni are highly variable rather than uniformly positive. Although improvements in biochemical and physiological traits are frequently reported, consistent yield gains occur only under specific combinations of soil, climate and genotype. This broader pattern reinforces that the contrasting responses observed between the two years in our study are aligned with the environment-dependent nature of Ni behavior in crop systems.

Beyond these numeric differences in optimal rates and critical thresholds, it is important to understand the physiological and environmental drivers underlying the contrasting responses observed between the two growing seasons. The contrasting optimal Ni rates and critical leaf thresholds observed between year I and year II can be mechanistically explained by the differences in water availability and the resulting physiological status of the plants in each season. In year I, cumulative rainfall (370.5 mm across 22 rainy days) was slightly below the range considered adequate for maize, indicating moderate water limitation during crop development. Under such conditions, reduced stomatal conductance and limited CO₂ diffusion make photosynthesis more vulnerable to additional stress factors, so that higher foliar Ni levels more rapidly shift from beneficial roles in ureide metabolism and pigment maintenance to inducing oxidative stress and pigment degradation. This explains the lower optimal rate (46.5 g ha-¹ Ni) and the lower critical toxicity threshold in the leaves (2.43 mg kg-¹), above which yield losses became pronounced. In contrast, in year II, cumulative rainfall was higher (578.53 mm over 51 rainy days), providing more favorable conditions for biomass accumulation, transpiration, and metabolic detoxification of Ni through dilution and compartmentalization in leaf tissues. As a result, maize plants tolerated higher foliar Ni concentrations without major yield penalties, which is reflected in the higher optimal rate (92.5 g ha-¹ Ni) and the broader adequate and sub-toxic leaf Ni ranges (up to 5.80 mg kg-¹ Ni). Therefore, the year-to-year differences in Ni diagnosis ranges and optimal doses are best explained by the interaction between foliar Ni supply, seasonal water availability, and the plants’ physiological resilience.

Critical ranges of Ni in maize

When Ni was supplied via the foliar route, there was a higher Ni content in the leaves and grains. The values considered toxic to plants are above 10 mg kg- 1 in sensitive species, above 50 mg kg- 1 in moderately tolerant species, and above 1.000 mg kg- 1 in Ni hyperaccumulator plants38,39. Usually, standard Ni content in plant dry matter ranges from 0.05 to 10 mg kg[- 1,39. Meanwhile, adequate leaf Ni content in cultivated plants generally ranges from 0.05 to 5 mg kg-140.

Overall, the diagnostic approach adopted here allowed us to delimit four functional ranges of foliar Ni in maize: deficiency, adequacy, critical toxicity and toxicity. Within the adequate range, leaf Ni concentrations were associated with 95–100% of maximum yield, whereas values above the critical toxicity threshold led to yield losses greater than 5%. Notably, the critical leaf Ni levels that signaled the onset of yield decline (≈ 2.4–5.8 mg kg-¹, depending on the year) were lower than the generic toxicity thresholds often cited for many cultivated species, which are typically above 10 mg kg-¹ dry matter38. This suggests that maize grown on sandy Oxisols under foliar Ni supply may express toxicity at comparatively modest foliar Ni concentrations, emphasizing the need for crop- and site-specific diagnostic ranges rather than relying solely on broad sufficiency intervals proposed for diverse species and environments.

Ni accumulation in grains and yield implications

Regarding Ni content in grains, variations can be observed between plant species and even between hybrids of the same species. These variations are mainly related to differences in uptake, transport, and redistribution of Ni between genotypes41. Accumulation occurs differently between tissues and throughout the plant life cycle and is higher in grains and leaves42. There are reports in the literature on Ni levels from 0.22 to 0.34 mg kg- 1 in maize grains grown in uncontaminated soil19. These findings support those previous studies20, in which the Ni content in food plants such as grains is from 0.39 to 2.07 mg kg- 1.

Critical Ni levels in animal diets vary according to species and feed type. Exposure to Ni in compound feed can reach elevated levels, particularly in complementary feed for fattening cattle and pigs, and continuous monitoring of Ni concentrations in feed is recommended14. In ruminants, Ni concentrations in feed may range from 0.36 to 3.91 mg kg-¹, depending on the nature of the feed43. For poultry, values typically range between 0.1 and 0.3 mg kg-¹ 14,3, while for pigs the range is 0.1 to 0.5 mg kg-¹43.

Taken together, the grain Ni concentrations measured in this study (approximately 0.4-1.0 mg kg-¹) fall within, or slightly above, the ranges reported for cereals grown on uncontaminated soils and are compatible with current recommendations for animal feeding19,43. Nevertheless, recent risk assessments have emphasized that dietary exposure to Ni can approach or exceed tolerable intake levels in sensitive human populations when multiple dietary sources are considered14. In this context, the fact that foliar Ni applications increased grain Ni, even while remaining within acceptable ranges, underscores the importance of continuous monitoring of Ni in cereal-based diets, especially in regions with naturally elevated soil Ni or intensive use of Ni-containing inputs.

Environmental and food safety considerations are also relevant, since foliar Ni supply may lead to the transfer of the metal to edible tissues. Previous studies indicate that Ni present in the soil or added through fertilizers can be translocated to grains, thereby contributing to human and animal dietary exposure44. Because grains, seeds and leguminous crops naturally contain measurable amounts of Ni, further increases can be particularly important for sensitive populations44. In addition, sustained accumulation of Ni in agricultural soils may alter microbial community structure and decrease enzymatic activity,45,46 with potential consequences for nutrient cycling and long-term soil functioning47. In the present study, however, the Ni concentrations measured in grains remained within the ranges reported for cereals grown under non-contaminated conditions, indicating that moderate foliar Ni applications can enhance physiological processes without compromising food safety or generating immediate environmental risks. These findings emphasize the need to define appropriate application ranges to ensure agronomic benefits while maintaining safe Ni levels in grain48,49,50,51.

Conclusions

Foliar nickel fertilization improved maize physiological performance, but the magnitude and consistency of responses varied between years, demonstrating that Ni effectiveness is strongly dependent on environmental conditions. Within moderate application ranges, Ni supported photosynthesis and crop functioning, whereas higher doses induced early signs of physiological stress. The contrasting optimal rates between years highlight that Ni recommendations should not rely on a fixed numerical value but instead be calibrated according to seasonal conditions, soil characteristics, and crop performance indicators.

Although grain Ni concentrations remained within acceptable limits for animal feed, the increases observed highlight the need for continued monitoring to prevent potential accumulation along the food chain. Future investigations should address multi-year and multi-environment datasets, interactions with other micronutrients, and the long-term environmental consequences of repeated foliar Ni application. Together, these results help refine safer and more context-dependent guidelines for the agronomic use of Ni in maize. Limitations of this study include the evaluation of a single hybrid and two growing seasons in one soil type, which constrains broader generalization. Additional research should therefore include a wider range of maize hybrids and soil types to strengthen the applicability of Ni fertilization recommendations.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abia - Associação Brasileira de Indústrias de Alimentação. Compêndio da Legislação de Alimentos. São Paulo. 1. (1985).

Albuquerque, P. E. P. Manejo de irrigação na cultura do milho (6ª ed., Sistema de Produção, 1). Embrapa Milho e Sorgo. (2010).

Baloš, M. Ž., Ljubojević, D. & Jakšić, S. The role and importance of vanadium, chromium and nickel in poultry diet. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 73, 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043933916000842 (2017).

Barcelos, J. P. Q. et al. Effects of foliar nickel (Ni) application on mineral nutrition status, urease activity and physiological quality of soybean seeds. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 11 (2), 184. https://doi.org/10.21475/ajcs.17.11.02.p240 (2017).

Dixon, N. E., Gazzola, C., Blakeley, R. L. & Zerner, B. Jack bean urease (EC 3.5. 1.5). Metalloenzyme. Simple biological role for nickel. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 97 (14), 4131–4133. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00847a045 (1975).

Freitas, D. S. et al. Hidden nickel deficiency? Nickel fertilization via soil improves nitrogen metabolism and grain yield in soybean genotypes. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 614. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.00614 (2018).

Brown, P. H., Welch, R. M. & Cary, E. E. Nickel: A micronutrient essential for higher plants. Plant Physiol. 85 (3), 801–803. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.85.3.801 (1987).

Kumar, O., Singh, S. K., Patra, A., Latare, A. & Yadav, S. N. A comparative study of soil and foliar nickel application on growth, yield and nutritional quality of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) grown in inceptisol. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 52 (11), 1207–1223. https://doi.org/10.1080/00103624.2021.1879119 (2021).

Tabatabaei, S. J. Supplements of nickel affect yield, quality, and nitrogen metabolism when Urea or nitrate is the sole nitrogen source for cucumber. J. Plant Nutr. 32, 713–724. https://doi.org/10.1080/01904160902787834 (2009).

Ameen, N. M. et al. Biogeochemical behavior of nickel under different abiotic stresses: toxicity and detoxification mechanisms in plants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26 (11), 10496–10514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-04540-4 (2019).

Rabinovich, A., Di, R., Lindert, S. & Heckman, J. Nickel and soil fertility: review of benefits to environment and food security. Environments 11 (8), 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments11080177 (2024).

Donagema, G. K., de Campos, D. V. B., Calderano, S. B., Teixeira, W. G. & Viana, J. H. M. Manual de métodos de análise de solo. Embrapa Solos. (2011).

Drążkiewicz, M. & Baszyński, T. Interference of nickel with the photosynthetic apparatus of Zea Mays. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 73 (5), 982–986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2010.02.001 (2010).

EFSA Panel On Contaminants In The Food Chain (CONTAM). Scientific opinion on the risks to animal and public health and the environment related to the presence of nickel in feed. EFSA J. 13, 4074 (2015).

Rodak, B. W. et al. Short–term nickel residual effect in field–grown soybeans: Nickel–enriched soil acidity amendments promote plant growth and safe soil nickel levels. Arch. Agron. Soil. Sci. 68 (11), 1586–1600. https://doi.org/10.1080/03650340.2021.1912325 (2021).

Hall, D. O. & Rao, K. K. Coleção Temas De Biologia: Fotossíntese (Editora Pedagógica e Universitária Ltda, 1980).

Rodak, B. W. et al. A study on nickel application methods for optimizing soybean growth. Sci. Rep. 14 (10556). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58149-w (2024).

Hassan, M. U. et al. Nickel toxicity in plants: reasons, toxic effects, tolerance mechanisms, and remediation possibilities a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26, 12673–12688 (2019).

Kabata-Pendias, A. & Pendias, H. Trace Elements in Soils and Plants 3 edn (CRC, 2001).

Kabata-Pendias, A. & Pendias, H. Trace Elements from Soil and Plant 4 edn (CRC, 2011).

Kamran, M. A. et al. Bioaccumulation of nickel by E. sativa and role of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPRs) under nickel stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 126, 256–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2016.01.002 (2016).

Santos, H. G.et al. Sistema Brasileiro de Classificação de Solos (5 ed.). Embrapa Solos. (2018).

Coelho, A. M. (ed) Cultivo Do Milho 9th edn (Embrapa Milho e Sorgo, 2015).

Raij, B. V. Análise química Para avaliação Da Fertilidade De Solos Tropicais (Instituto Agronômico, 2001).

Rodak, B. W. et al. Methods to quantify nickel in soils and plant tissues. Revista Brasileira De Ciência Do Solo. 39, 788–793. https://doi.org/10.1590/01000683rbcs20140542 (2015).

Sousa, D. M. G. & Lobato, E. Cerrado: correção Do Solo E adubação 2. edn (Embrapa Cerrados, 2004).

Lichtenthaler, H. K. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. Methods Enzymol. 148, 350–382 (1987).

Mathur, S., Sharma, M. P. & Jajoo, A. Improved photosynthetic efficacy of maize (Zea mays) plants with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) under high temperature stress. J. Photochem Photobiol B. 180, 149–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.02.002 (2018).

Prado, R. M. Nutrição De Plantas 2 edn (Editora UNESP, 2021).

Silva, F. C. Manual De análises químicas De solos, Planta E Fertilizantes 2 edn (Embrapa Informação Tecnológica, 2009).

Freitas, D. S., Rodak, B. W., Carneiro, M. A. C. & Guilherme, L. R. G. How does Ni fertilization affect a responsive soybean genotype? A dose studies. Plant. Soil. 441, 567–586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-019-04146-2 (2019).

Sheoran, I. S., Singal, H. R. & Singh, R. Effect of cadmium and nickel on photosynthesis and the enzymes of the photosynthetic carbon reduction cycle in Pigeonpea (Cajunus Cajan L). Photosynth. Res. 23, 345–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00034865 (1990).

Levi, C. C. B. Níquel Em Soja: Doses E Formas De aplicação [Dissertação De mestrado, Instituto Agronômico, Curso De Pós-Graduação Em Agricultura Tropical E Subtropical] (Instituto Agronômico, 2013).

Oliveira, R. L., Corrêa, J. C., Binotti, F. F. S. & Cardoso, A. I. I. Effects of nickel and nitrogen soil fertilization on lettuce growth and urease activity. Revista Brasileira De Ciência Do Solo. 37 (1), 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-06832013000100011 (2013).

Freitas, L. B. et al. Hidden nickel deficiency? nickel fertilization via soil improves nitrogen metabolism and grain yield in soybean genotypes. Front. Plant Sci. 9 (614). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.00614 (2018).

Barman, M., Chakraborty, R., Bhattacharyya, P. & Maiti, D. Chemical fractions and bioavailability of nickel in alluvial soils. Plant. Soil. Environ. 61 (2), 66–72. https://doi.org/10.17221/883/2014-PSE (2015).

Macedo, F. G., Almeida, J. A. & Kampf, N. Nickel availability in soils cultivated with different crops under varying pH, texture and organic matter conditions. Pedosphere 30, 560–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1002-0160(20)60015-7 (2020).

Seregin, I. V. & Kozhevnikova, A. D. Physiological role of nickel and its toxic effects on higher plants. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 53, 257–277 (2006).

Yusuf, M., Fariduddin, Q., Hayat, S. & Ahmad, A. Nickel: an Overiew of uptake, essentiality and toxicity in plants. Bull. Environ Contam. Toxicol. 2011 (86), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00128-010-0171-1 (2011).

Liu, G., Simonne, E. H., Li, Y., Extension, I. F. A. S. & HS1191. Nickel nutrition in plants. University of Florida, Available at: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/HS1191 (2011).

Rebafka, F. P., Schulz, R. & Marschner, H. Erhebungsunter-suchungen Zur pflanzenverfügbarkeit von nickel auf böden Mit Hohen geogenen Nickelgehalten. Angewandte Botanik. 64, 317–328 (1990).

Palacios, G. & Mataix, J. The influence of organic amendment and nickel pollution on tomato fruit yield and quality. J. Environ. Sci. Health. 34, 133–150 (1999).

Spears, J. W., Hatfield, E. E., Forbes, R. M. & Koenig, S. E. Studies on the role of nickel in the ruminant. J. Nutr. 108 (2), 313–320. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/108.2.313 (1978).

Rizwan, M. et al. Nickel uptake, toxicity and detoxification mechanisms in plants. Environ. Pollut. 346, 123234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2023.123234 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Bacterial community structure and diversity in a long-term nickel-contaminated agricultural soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 22, 5280–5289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-014-3476-6 (2015).

Ma, J., Zhang, H., Duan, C., Guo, X. & Wang, R. Microbial enzymatic activity and community composition under nickel stress in soil. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 167, 36–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.09.090 (2019).

Uchimiya, M. et al. Chemical speciation, plant uptake and toxicity of heavy metals in agricultural soils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 68, 12856–12869. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.0c00183 (2020).

Rai, P. K., Lee, S. S., Zhang, M., Yiu, F. T. & Kim, K. H. Heavy metals in food crops: health risks, fate, mechanisms and management. Environ. Int. 125, 365–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.01.067 (2019).

Tóth, G., Hermann, T., Silva, M. R. & da, Montanarella, L. Heavy metals in agricultural soils of the European union with implications for food safety. Environ. Int. 88, 299–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2015.12.017 (2016).

Angon, P. B. et al. Sources, effects and present perspectives of heavy metals contamination. Heliyon 10 (7). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28357 (2024).

Islam, M. S. et al. Toxicity assessment of heavy metals translocation in maize grown in the Ganges delta floodplain soils around the Payra power plant in Bangladesh. Food Chem. Toxicol. 193 (115005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2024.115005 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS-CPCS), Fundação de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento do Ensino, Ciência e Tecnologia do Estado de Mato Grosso do Sul (FUNDECT) TO 88/2021 and SIAFEM 30478. EDITAL No. 13 of May 3, 2021, made available via SEI process No. 23455.000175/2021-15., and the Cerrado Plant Nutrition Study Group (GECENP).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Marcia Leticia Monteiro Gomes and Cid Naudi Silva Campos; Data curation, Cid Naudi Silva Campos; Formal analysis, Paulo Eduardo Teodoro and Larrisa Pereira Ribeito Teodoro; Funding acquisition, Cid Naudi Silva Campos and Ranato de Mello Prado; Visualization, Estêvão Vicari Mellis, Aryane Jesus Ferreira, Rafael Ferreira Barreto and Mayara Fávero Cotrim; Writing – original draft, Marcia Leticia Monteiro Gomes and Cid Naudi Silva Campos. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All authors of the manuscript have read and agreed to its content and are accountable for all aspects of the accuracy and integrity of the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gomes, M.L.M., Campos, C.N.S., de Mello Prado, R. et al. Foliar nickel fertilization enhances photosynthesis and defines critical leaf levels and optimal rate in maize. Sci Rep 16, 1449 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31546-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31546-5