Abstract

Precise displacement monitoring is essential for evaluating the safety and dynamic response of bridge structures under service loads. Conventional techniques, such as displacement gauges and GPS, are often constrained by installation complexity, limited accuracy, and sensitivity to environmental factors. To overcome these limitations, this study introduces a novel non-contact monitoring system based on a 60.25 GHz millimeter-wave radar chip. The system achieves high measurement precision and rapid deployment without direct attachment to the structure. Target indication using mean cancellation and hamming windowing, combined with advanced displacement identification algorithms based on ap-FFT, further enhances measurement precision. Additionally, a customized MATLAB graphical user interface (GUI) was further developed to facilitate real-time data collection and analysis. Rigorous testing commenced with controlled laboratory experiments, followed by validation against measurements from a fixed-action camera for displacement. The system’s practicality was validated through field experiments on the Phoenix bridge subjected to live loading, emphasizing its efficacy in real-world scenarios. In field applications, the system demonstrated reliable accuracy, achieving a root mean square error (RMSE) of just 0.02 mm compared to validated measurements. In conclusion, this innovative radar-based system effectively addresses the need for accurate, non-intrusive, and easily deployable methods for evaluating bridge structural behavior. By seamlessly integrating modified radar technology with sophisticated displacement identification algorithms, this system proves its effectiveness across controlled environments and practical field applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Engineering infrastructures, such as bridges, consistently endure stress from vehicle loads and environmental factors, posing significant threats to their structural integrity. Consequently, implementing effective structural inspection and monitoring is crucial for ensuring engineering safety, maintaining structural stability, and guaranteeing operational performance1,2. Structural health monitoring (SHM) plays a pivotal role in assessing structural responses and integrity under varying loads and environmental conditions, providing critical data for the maintenance and management of aging infrastructure3,4. Recently, sensors like accelerometers and strain gauges are widely utilized for measuring bridge responses5,6,7. However, recent years have seen a growing interest in using displacement measurements to evaluate bridge performance8,9,10,11. This shift in focus indicates a recognition of the nuanced insights that displacement data can provide, complementing traditional sensing methods and enhancing our understanding of structural behavior.

Displacement measurement techniques can be broadly categorized into indirect and direct methods. Indirect methods estimate displacement using parameters such as acceleration, strain, angular displacement, and curvature12,13,14. However, these methods often face challenges such as data drift caused by low-frequency noise during acceleration integration. Similarly, techniques involving inclinometers or strain gauges may accumulate errors due to reliance on local derivatives of inclination or curvature. In contrast, direct methods are divided into contact-based and non-contact approaches. Contact-based techniques, such as Linear Variable Differential Transformers (LVDTs) and dial indicators, require direct interaction with the bridge structure, which may be impractical or unsafe in certain scenarios15,16. GPS-based systems, with centimeter-level measurement accuracy, are commonly applied to long-span bridges17,18. Non-contact approaches, such as laser sensors, are constrained by range limitations, making them suitable only for short-range measurements19,20. Computer vision-based displacement measurement techniques, gaining attention and applied in practical engineering applications21,22,23,24, extract displacement information between frames by installing targets or utilizing natural features. However, these methods have limitations as their measurement accuracy can be influenced by environmental factors like wind, ground vibrations, temperature, and the employed image processing algorithms.

In recent years, microwave radar techniques have emerged as promising tools in SHM25,26,27. This radar-based system emits frequency-modulated signals towards structures, capturing the reflected signals for analysis. The frequency difference between transmitted and received signals facilitates determining the distance of the structure along the radar’s line-of-sight (LOS). Moreover, extracting the phase difference related to the target frequency enables displacement measurement along the LOS of the radar. Importantly, the radar-based system remains unaffected by weather or lighting conditions, making it valuable for monitoring displacement in large-span bridges, pedestrian overpasses, traffic signal support structures, and similar constructions28,29,30. Early research in this field primarily employed centimeter-wave radar (< 30 GHz), but these systems struggled with range resolution when monitoring medium and small-sized bridges31,32. To address this limitation, some researchers explored multiple synchronized radar systems or two-dimensional imaging radar33,34,35. However, these approaches remained expensive and cumbersome, lacking the flexibility of measurement available in conventional visual systems. Consequently, there is growing interest in more flexible, cost-effective solutions.

With the continuous progress in microwave technology, the emergence of robust and economically viable radar chips has led to the development of millimeter-wave radar. This technology has found diverse applications in areas such as smart automobiles and smart healthcare36,37,38. Simultaneously, owing to its shorter wavelength, millimeter-wave technology holds significant promise for measuring minute displacements. For example, Xiong et al.39 highlights this potential, exploring the use of millimeter-wave technology for close-range vital sign monitoring in humans. Moreover, millimeter-wave radar systems offer several advantages, including compact dimensions, lightweight construction, low power consumption, and cost-effectiveness, making them suitable for operation under various extreme weather conditions.

Recent studies have further explored the application of millimeter-wave radar in structural monitoring. For instance, Murakami et al.40 developed a high-sensitivity millimeter-wave radar imaging system for non-destructive testing, demonstrating its potential for industrial applications. However, their focus on imaging systems differs from the present study, which targets bridge displacement monitoring. Similarly, Pagnini et al.41 investigated the use of multi-monostatic multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) radar for transversal displacement detection in arched bridges, highlighting the potential of MIMO radar in SHM. While their work provides valuable insights into MIMO radar applications, the present study focuses on a single radar system with advanced signal processing techniques for vertical displacement measurement. Additionally, Xu42 proposed a machine vision-based approach for vehicle load identification using displacement influence lines, offering a complementary perspective to radar-based methods. However, the present study distinguishes itself by leveraging millimeter-wave radar technology for non-contact displacement measurement, providing a robust alternative to vision-based methods in environments with challenging lighting and weather conditions.

This paper explores the field by demonstrating the efficacy of consumer-grade millimeter-wave radar chips in monitoring bridge structure displacements. The radar chip chosen is a commercial off-the-shelf option recognized for its high range resolution and durability, distinguishing it from custom-designed alternatives. The study encompasses the development and field testing of a novel displacement measurement system that leverages nano millimeter-wave radar technology. It provides an evaluation of the system’s suitability for real-world deployment, focusing on its ability to capture dynamic behavior under live loading conditions. The effectiveness validation involves a comparison of radar-based measurements with measurements from fixed-action cameras for displacement.

The paper is structured as follows: The section "The proposed methodology" details the proposed method, including target indication techniques, a high-precision phase measurement approach, and specifications of the radar system. The sections "Laboratory experimental verification" and "Field experimental validation" present the experimental setup and validation tests conducted in both laboratory and field environments. Finally, the section "Conclusions" summarizes the conclusions and discusses implications for future research.

The proposed methodology

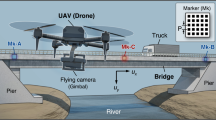

The concept of millimeter-wave radar displacement measurement is visually depicted in Fig. 1. In this configuration, a nano millimeter-wave radar is strategically positioned on a stationary tripod, observing the dynamic loadings on the bridge. The radar captures both the frequency variations induced by the bridge’s target and the phase alterations resulting from structural vibrations. One notable advantage of this system is its capability to assess displacement at any location across the bridge span, all from a single, fixed radar position. The advancement of radar-based systems relies on sophisticated post-processing algorithms adept at accurately converting microwave phase changes into precise measurements of bridge displacements. The processing framework of the millimeter-wave radar measurement system developed in this study encompasses three essential modules. Initially, a method that integrates mean cancellation and Hamming windowing is employed for precise target indication. Subsequently, the all-phase FFT (ap-FFT) method is applied to achieve high-precision measurement of the phase corresponding to the target’s range bin. Finally, the measurement of bridge displacement is realized through the implementation of the phase interference method.

Target indication using mean cancellation and hamming windowing

The operational principle of millimeter-wave radar revolves around initiating measurements of echoes from targets within the radar line of sight by modulating the frequency. Subsequently, the time-domain I/Q signals obtained after AD sampling undergo processing. These I/Q signals are then converted into the frequency domain, and measurement targets are identified by detecting the frequency peaks. In the realm of bridge displacement measurement, targets within the radar line of sight fall into two categories: measurement targets (such as the bridge structure) and non-measurement targets (such as people, vehicles, the ground, or other structures). Due to the limited beam angle of the millimeter-wave radar chip, the target selection is susceptible to the influence of frequency peak selection. In situations where the echo energy of each distance unit is relatively high and frequency peak points lack distinctiveness, the identification of targets becomes more challenging.

Assuming non-measurement targets are stationary and maintain a constant distance relative to the radar, the echo delay received in each chirp remains unchanged. This phenomenon results in a mere increase in the signal’s amplitude without affecting the phase, primarily influencing the identification of measurement targets. Therefore, by introducing mean cancellation-entailing averaging the echo signals from all chirps to obtain a reference echo signal-and subsequently subtracting the reference signal from each chirp signal, the target echo signal can be derived, as follows:

where \(\:m\:\)and \(\:i\) is the number of sampled points in fast time and slow time, respectively. Therefore, mean Cancellation can be expressed as:

The mean cancellation algorithm mentioned earlier effectively mitigates the echo energy from stationary targets, simultaneously improving the signal-to-noise ratio for subtle dynamic targets. The process of identifying targets involves converting the measured time-domain I/Q signals into the frequency domain for analysis. In traditional FFT algorithms, the finite length of the signal can lead to leakage phenomena in the frequency spectrum, resulting in noticeable distortions, initial values, harmonics, and other non-ideal characteristics. Additionally, the selection of the radar chip with a relatively large beam angle leads to high sidelobe levels, making targets susceptible to confusion in the presence of strong interference or multipath effects. Therefore, considering the introduction of a Hamming window \(\:(w\left(n\right)=0.54-0.46\text{cos}\left(\frac{2\pi\:n}{N-1}\right)\)) for smooth weighted processing of the signal in the time domain proves beneficial, suppressing endpoint leakage and reducing sidelobe levels. Signal truncation is employed to minimize the impact of non-target signals on the target signal.

Phase measured using ap-FFT

In comparison to traditional FFT, the all-phase fast Fourier transform (ap-FFT) is an FFT optimization method, which not only excels in suppressing spectrum leakage but also demonstrates phase invariance. The specific method for high-precision measurement of target phase based on ap-FFT is as follows.

As illustrated in Fig. 1, the millimeter-wave radar functions by transmitting and receiving linearly modulated continuous waves, undergoing subsequent frequency mixing. Following this process, the signals are sampled by the AD converter, resulting in the acquisition of in-phase (I) and orthogonal (Q) signals with a length of \(\:N\).

where \(\:{A}_{I}\) and \(\:{A}_{Q}\) are the amplitudes of the \(\:I\) and \(\:Q\) signals, respectively. \(\:{\theta\:}_{0}\:\)is a constant phase shift due to the detection distance and the reflection at the surface of the target, and \(\:{\Delta\:}{\phi\:}_{i}\) is the phase information corresponding to the target movement, and \(\:{\phi\:}_{noise}\) is the phase noise of the radar.

Next, the I/Q signals are merged to create the intermediate frequency (IF) signal, denoted as \(\:IF\left({t}_{i}\right)=I\left({t}_{i}\right)+j\times\:Q\left({t}_{i}\right)\). Subsequently, the previously mentioned target indication method is employed to perform a frequency domain transformation on the IF signal, determining the range bin index \(\:k\) corresponding to the target’s location. Let \(\:M=N-k\), designating the range bin linked to the target as the center, a new intermediate frequency signal \(\:\widehat{IF}\left({t}_{i}\right)\) is created by selecting \(\:2M+1\) data points from the IF signal. Then, with \(\:n=-M+1,-M+2,\dots\:,M-1\), preprocess the newly formed IF signal by enumerating all signals of length \(\:M\) that include the signal center point, expressed as,

Sequentially shift the above signals to the left, generating \(\:M\) signals with \(\:\widehat{IF}\left(0\right)\) positioned at the beginning of each signal, that is,

Combine with the data at corresponding positions in the \(\:\overline{\overline{{IF}}} \left( n \right)\) signals to form a signal of length \(\:M\), denoted as \(\:\stackrel{-}{IF}\left(n\right)\), which can be expressed as:

Subsequently, perform FFT transformation on the result of full-phase preprocessing to obtain the ap-FFT result. Extract the phase information corresponding to the target distance unit \(\:k\). Through the utilization of the phase interference method, measuring the displacement of the target becomes feasible.

where \(\:\lambda\:\) is the wavelength of the electromagnetic signal. It is worth underlining that the interferometric technique, represented by Eq. (3), provides a measurement of the radial displacement of all the range bins of the structure illuminated by the antenna beam; hence, the evaluation of the actual displacement requires the prior knowledge of the direction of the actual motion. For many bridges, the displacement under traffic loads can be assumed as vertical and it can be easily evaluated by making straightforward geometric projections.

Hardware configuration

As shown in Fig. 2, the IWR6843ISK radar chip from Texas Instruments43,44 is selected for displacement capture in this project due to its high resolution, portability, and user-friendly design as a millimeter-wave sensor evaluation module. The radar is controlled by a standard USB communication interface from a control PC. Utilizing complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor technology, the radar module integrates various components, including signal sources, mixers, multipliers, low-noise amplifiers, filters, analog-to-digital converters (ADCs), memory, signal processing, and control units onto a single chip. The antennas of the module are etched on the packaging, forming the radar front-end board, which incorporates four receiving antennas and three transmitting antennas. This configuration results in a 6 dB beam-width with a corresponding azimuth angle of 80 degrees and an elevation angle of 30 degrees.

Operating with a starting frequency of 60.25 GHz, a maximum frequency slope of 64.985 MHz/us, and a maximum range bandwidth of 3.25 GHz, the module achieves a maximum range resolution of 0.04615 m, supported by 200 ADCs sampling points and a maximum sampling rate of 4 MHz. Furthermore, the module boasts a working temperature range of −20 °C to 60 °C, enabling long-term deployment in harsh environmental conditions such as heavy fog and rain. While the module has demonstrated success in smart healthcare applications, monitoring respiratory and heartbeat rates at close distances, its relatively large beam-width poses challenges in long-range bridge displacement measurements due to interference from static clutter. The commercial software’s filtering methods may not effectively eliminate this interference, and the module’s design for short-range measurements may render the working range settings unsuitable for bridge structure displacement measurements.

It should be noted that the IWR6843ISK chip used in this study supports a maximum of 200 sampling points per chirp, with a maximum sampling time of 40 µs and a slow-time sampling interval of 10 ms. In terms of computational complexity, while the traditional FFT has a complexity of \(\:O\left(N{\text{log}}_{2}N\right)\) and the proposed ap-FFT exhibits a higher theoretical complexity of \(\:O\left({N}^{2}{\text{log}}_{2}N\right)\), the actual computation time difference between the two is negligible in practice due to the limited sample size. Under identical computing conditions, the additional processing time introduced by ap-FFT does not materially affect software integration or real-time performance.

To address these challenges, the DCA1000EVM data acquisition board was used for developing and refining the chip’s low-level programs. Initially, to extend the working distance of the radar chirp, the sampling rate for individual snapshots was reduced while retaining the number of ADC sampling points, effectively enhancing its capability for long-range monitoring. Additionally, our focus was on optimizing the gain of both transmitting and receiving antennas, elevating it from the reference design’s 6dBi to 10dBi.The TX3 and RX1 antenna combination with maximum spacing was selected to enhance channel isolation. Additionally, a Graphical User Interface (GUI) software tool was created in MATLAB to control the system, leveraging the methods and radar principles discussed earlier. This software enhanced project management by streamlining creation, ensuring seamless radar connectivity, and automating data storage, as discussed in later sections.

Software tool development

A MATLAB-based graphical user interface (GUI) program was developed to control the system, leveraging the methods and radar principles discussed earlier. The GUI was developed using MATLAB version R2023a (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA). This software enhanced project management by streamlining creation, ensuring seamless radar connectivity, and automating data storage. The key features are detailed below:

Window A. Functions as the target indication window, integrating the developed target indication method for selecting measurement targets.

Window B. Displays real-time displacement-time curves of the chosen targets, incorporating the high-precision phase measurement method. Users can adjust the displayed displacement duration through a ruler at the bottom of the interface.

Window C. Showcases the frequency spectrum information corresponding to the displacement-time curves of the selected targets. It employs sliding window techniques, selecting a specified length (1024 points) for FFT transformation of the measured target displacement, facilitating real-time display and updates of the target frequency spectrum information.

On the right side of the software, a software logo is positioned at the top. To enhance user-friendliness, parameters related to real-time target display and storage are provided, including the selection of target ranges, storage duration, and conversion factors for radial-to-vertical displacement conversion.

At the bottom of the software, the primary functions include Universal Asynchronous Receiver/Transmitter (UART), configuration, run/stop, record, and playback. These functions streamline device debugging, installation position determination, and pitch angle selection at the test’s outset, aligning with the displayed interface.

Laboratory experimental verification

To validate the effectiveness and performance of the proposed radar-based displacement measurement system, a series of controlled laboratory experiments were conducted. These experiments were designed to evaluate the system’s precision, robustness, and ability to measure both static and dynamic displacements under various conditions. Comparative analyses were also performed to assess the radar measurements against those obtained from a vision displacement sensor, ensuring the reliability and accuracy of the proposed system.

Sliding table experiment

The sliding table experiments were divided into single-target and multi-target tests to evaluate the system’s precision and robustness in different scenarios. The single-target tests focused on the system’s performance under varying radar ranges, while the multi-target tests assessed its capability to measure multiple displacements simultaneously.

Single-target sliding table test

The experimental setup for the single-target test is illustrated in Fig. 3(a). The radar sensor was mounted on a tripod, and an aluminum corner reflector (\(\:200\times\:200\times\:200\:mm\)) served as the measurement target, aligned at the same height as the radar. The reflector was attached to a slider mounted on a guide rail. The detailed experimental conditions were as follows: (1) Incrementally adjusting the distance between the radar and the corner reflector by 10 m intervals, ranging from 10 m to 60 m; (2) In each experiment, the controller directed the slider through 10 movements towards the radar, with predetermined step lengths of 0.2 mm, 0.5 mm, 1.0 mm, and 2.0 mm. As a benchmark value, the theoretical resolution \(\:\varDelta\:L\) of the slider’s guide rail could be calculated as a function of the rail’s screw length \(\:L\) and the step angle \(\:{\Delta\:}\theta\:\) of the guide rail’s stepper motor, formulated as: \(\:{\Delta\:}L=(L\times\:\varDelta\:\theta\:)/(N\times\:{360}^{^\circ\:})\).

Multi-target sliding table test

Figure 3(b) depicts the scenario of a multi-target slider experiment. In this experiment, the corner reflectors were affixed to tripods, arranged in a line with approximately 6 m spacing. The radar sensor, mounted at the same height on a slider affixed to a tripod, was positioned 4 m from the line of corner reflectors, forming an angle \(\:{18.5}^{^\circ\:}\) of with the line of corner reflectors. The step sizes of the slider were set to 5 mm, 2 mm, and 1 mm, respectively, advancing 10 steps toward the direction of the corner reflectors each time. To enhance the precision of displacement measurement, especially considering the influence of target echo intensity observed in the previous single-target experiment, five strategically placed corner reflectors (\(\:300\times\:300\times\:300\:mm\)) were positioned at a distant location. Simultaneously, in the close-range configuration, four corner reflectors of dimensions identical to those used in the single-target test were employed. It’s important to note that, due to the radar sensor being mounted on a slider for movement, the target indication method discussed earlier cannot be validated in this experiment.

Results and analysis

To validate the proposed target indication method’s effectiveness, Fig. 4 illustrates the target range spectrum in fast time from the radar-based system, capturing displacements of a single target (target range: 20 m) and multiple targets. The results demonstrate the method’s capability to mitigate static clutter energy effectively, eliminating interference from static targets, such as buildings approximately 66 m away. This enhancement significantly improves target indication during on-site radar measurements. Additionally, the target range spectrum of multi-targets shows that the developed radar-based system efficiently measures nine corner reflectors within a distance range of 7.5 m to 60 m. Notably, Corner reflector No. 3, positioned in the radar’s line of sight, exhibits the highest echo intensity, while the target at the farthest distance (Corner reflector No. 9) shows the weakest echo intensity.

To validate the efficacy of the proposed high-precision phase measurement method, Fig. 5 presents the displacement measurement results of the single-target sliding table test. In this test, the target is positioned at 20 m, with sliding table step sizes of 0.5 mm and 0.2 mm, respectively. Results show that under the 0.5 mm step condition, the maximum standard deviation of the proposed ap-FFT phase measurement method during displacement stabilization phases was 0.029 mm, whereas the conventional FFT method yielded 0.189 mm. When the step size was reduced to 0.2 mm, the proposed method achieved a further reduced maximum standard deviation of 0.017 mm, compared to 0.26 mm for the conventional FFT. These comparative results confirm the significantly superior measurement accuracy of the proposed ap-FFT approach over the conventional FFT method.

Furthermore, Fig. 6 illustrates the displacements of different corner reflectors under the multi-target sliding table test with a step size of 5 mm. The results demonstrate that the proposed ap-FFT phase measurement method achieves satisfactory agreement between measured and theoretical values in synchronous multi-target monitoring scenarios. Nevertheless, it should be noted that with increasing radar detection range and corresponding reduction in angular variations, discernible displacement fluctuations emerge in long-distance target measurements.

Figure 7 shows the target range spectrums in slow time of the corner reflector for the single-target sliding table test at different radar ranges. The results show that the proposed target indication method can efficiently mitigate interference from static clutter when the radar range is less than 50 m. However, the effectiveness of the method diminishes as the target range increases, and the echo intensity weakens.

To further clarify this issue, Fig. 8 compares the mean echo intensities between the corner reflector and static clutter under the single-target sliding table test at different radar ranges. The results indicate that under the same measurement conditions, as the radar range increases, the echo intensity of the corner reflector decreases, while the echo intensity of static clutter increases. Specifically, when the range exceeds 50 m, the echo intensities of both become essentially identical, posing a challenge for the proposed method to effectively mitigate static clutters and ensure accurate target indication.

Relative error and root mean square error (RMSE) were used to evaluate the ap-FFT method’s accuracy. Figure 9(a) shows that for single-target tests, ap-FFT produces lower relative errors and RMSEs compared to traditional FFT under different conditions. Notably, as the radar range increases, there is a corresponding upward trend in both displacement RMSEs and relative errors. Interestingly, the impact of the slider step size on this trend was found to be insignificant. This observation leads to the conclusion that the accuracy of radar-measured target displacement is primarily influenced by radar range, and it remains independent of the measurement range of the target displacement. Furthermore, Fig. 9(b) presented the displacement relative errors and RMSEs of different targets with varied step sizes. The study results demonstrated that, within the specified experimental conditions, the maximum relative error between radar measurements and theoretical values stays below 5%, and the maximum RMSE is less than 0.05. However, it’s noteworthy that with the increase in the radar’s effective range, resulting in smaller angular changes, both the displacement relative errors and RMSEs exhibit an upward trend. This observed pattern aligns with the findings from the previously mentioned single-target slider experiment.

Simply supported beam experiment

To evaluate the capability of the proposed radar-based system in measuring both static and dynamic displacements, experiments were carried out using a rigid aluminum beam. The beam, featuring a scaled, simply supported rectangular section measuring approximately \(\:300\times\:20\times\:6\:cm\), was securely affixed to steel supports at its ends using F-type clips. The experimental setup involved loading and unloading three mass blocks, each weighing 30 kg, at the 1/4 position of the beam’s length (1/4L) to induce beam displacements. And the process repeated three times to ensure measurement repeatability and statistical reliability. Figure 10(a) provides a visual representation of this setup. To capture the beam’s displacements accurately, a fixed camera was deployed, and markers were strategically placed. Both the radar and the fixed camera operated at a sampling rate of 20 Hz. Figure 10(b) details the experiment’s configuration, and the procedure is outlined as follows:

Case 1. The radar sensor was placed on the ground to vertically measure the target at the 1/4L position.

Case 2. The radar sensor was positioned at the 1/2L position, measuring the displacement of 1/2L with the laboratory floor serving as a fixed reference target.

These two scenarios, representing distinct measurement approaches, were conducted in a staged loading manner to assess the performance of the radar-based system.

Results and analysis

Figure 11 presents the target range spectrum in fast time for the two aforementioned cases. A comparison between the FFT method and the proposed ap-FFT method revealed the latter’s effectiveness in mitigating static clutters, thereby significantly improving the identification of the target. Notably, when contrasting Case 1 (where the radar irradiates targets in open space) with Case 2 (where the radar irradiates the ground), the latter showcases multiple targets within the 0.8–0.9 m range. This observation is primarily attributed to the radar’s wide inherent beam angle, which segments the ground into distinct targets. Opting for the nearest target during the target selection process proves to be a viable approach. Figure 12 presents the target range spectrums in slow time for both scenarios. The results indicate that static clutter maintains a stable energy distribution along the slow-time dimension. By applying the proposed target indication method to each chirp’s range spectrum, the technique effectively removes distant static clutter interference while significantly suppressing nearby static clutter around the target. These findings collectively demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed methodology.

The displacements of the 1/4L and 1/2L sections of the simply supported beam during load tests are shown in Fig. 13. These displacements were derived by extracting phase information from the radar measurements and applying the phase interference method for calculations. When compared to the displacements measured by the fixed camera, the radar-based results show a significant degree of agreement. Figure 14 depicts the relative error in the displacements of the 1/4L and 1/2L sections during stable loading phases. Across all stable loading phases, the maximum relative error remains below 4%, demonstrating the reliability of the radar system for displacement measurement.

Notably, the simply supported beam’s relatively low stiffness resulted in abrupt changes in load (loading or unloading), inducing free vibrations within the beam. Figures 15 and 16 present the time-frequency domain information of the free vibration displacements at the 1/4L and 1/2L sections during various phases. The time-domain data of free vibrations during loading and unloading were recorded, and a subsequent time-frequency domain analysis was conducted. When compared to measurements from the fixed camera, differences in the time domain were observed, albeit following similar trends. These variances were primarily attributed to accumulated errors. However, in the frequency domain, a high degree of consistency is evident.

Field experimental validation

To validate the developed radar-based system in real-world scenarios, field tests were conducted on the Phoenix Bridge, a medium arch bridge, specifically for displacement measurement.

Description of the bridge and the field test

The Phoenix Bridge, situated in Jiangsu province, China, is a half-through arch bridge with a span of approximately 30 m. It features a box cross-section for both the arch and the arch tie, with ties suspended from the arches using 13 pairs of steel hangers. The bridge incorporates a ballasted deck, crossbars made from double-tee plate girders, and a reinforced concrete slab floor.

Figure 17 presents the measured diagram and the scene during the tests, conducted under normal traffic loading conditions. Section 1/5L and 1/2L of the right-side span were selected for examination. The same fixed camera used in previous laboratory experiments operated at a sampling rate of approximately 20 Hz. The proposed radar-based system was employed for measurements, demonstrating the proposed method, while the fixed camera validated the accuracy and robustness of the system. The distances between the radar and the targets were approximately 1.18 m and 3.46 m for Sect. 1/5L and 1/2L, respectively.

Experimental results

Target identification and range spectrum analysis

Figure 18 shows the target range spectrum in fast time of the 1/5L and 1/2L sections, respectively. During on-site testing of the 1/2L section in an open field environment, target echo intensities were more pronounced compared to the laboratory simply supported beam experiments. In this scenario, the proposed target indication method did not show significant improvements over traditional FFT method. However, when measuring the 1/5L section, with a substantial height difference between the bridge deck and the bottom of the main girder, the range spectrum obtained directly using FFT effectively reflected this relationship. The application of the proposed method, including mean removal and windowing techniques, proved effective in highlighting the measurement points on the main girder.

To further evaluate the proposed method’s effectiveness in target indication across the complete measurement cycle, Fig. 19 displays the slow-time target range spectra for the 1/2L and 1/5L sections, respectively. The results indicate that the radar-captured echo energy maintains a stable distribution across the complete measurement cycle. The proposed method yields clearer results in the 1/5L section than in the 1/2L section, which demonstrates its stronger capability in near-field scenarios for suppressing non-target clutter energy. This effectively enhances the energy peak of target echoes, thereby improving the accuracy of target detection and extraction.

Displacement measurement under traffic loading

By separately extracting the phase information from the range spectrum lines corresponding to the 1/5L and 1/2L sections and applying the phase interference method, the displacements of these two sections under daily operational conditions were calculated. As shown in Fig. 20, it is found that the amplitude of the bridge’s vibration is less than 1 mm, revealing that in situations involving minor structural deformation, the proposed radar-based system effectively measures structural displacement information and aligns well with imaging results. Notably, compared to the fixed camera, the proposed radar-based system exhibits higher sensitivity.

Discussion of field test results

The field tests on the Phoenix Bridge demonstrated the radar system’s capability to accurately measure bridge displacements under real-world conditions. The system successfully captured subtle deformations in the bridge structure under daily operational loads, achieving a reliable measurement precision of 0.02 mm. These results highlight the system’s potential as a reliable, non-contact solution for bridge displacement monitoring in practical applications.

The proposed radar-based system offers several advantages over traditional methods, including its ability to operate in diverse environmental conditions, its high sensitivity to small displacements, and its cost-effectiveness. The system’s performance in the field tests further validates its applicability for SHM of medium-span bridges, providing a robust alternative to conventional contact-based sensors.

Conclusions

This study presents a novel displacement measurement system based on a nano millimeter-wave radar, offering a non-contact, high-precision solution for bridge monitoring. Comprehensive testing was carried out in both controlled laboratory settings and real-world environments, with the experimental results compared against data collected from a fixed camera system. The key findings are summarized as follows:

-

(1)

The radar-based system is founded on the TI radar chip, offering notable advantages such as non-contact operation, lightweight design, and low power consumption. To ensure accurate displacement measurements from multiple points on bridge structures, a custom-developed method for target indication and precise phase measurement has been implemented. Moreover, the control software, featuring a MATLAB-based GUI, allows for real-time display and personalized storage of displacement data, significantly enhancing user convenience.

-

(2)

Extensive validation of the proposed radar-based system was conducted through laboratory slider experiments, showcasing its effective operating range of 60 m and the capability to simultaneously measure a minimum of 9 targets. These experiments establish a clear correlation between the measurement accuracy of each target and the reflected energy at that specific point. Additionally, simply supported beam experiments affirm the effectiveness of the developed target indication and high-precision phase measurement methods, showing good agreement with the results obtained from fixed camera measurements.

-

(3)

Field tests on bridges validated the radar system’s effectiveness in real-world scenarios. The system successfully captured subtle deformations in bridge structures under daily operational loads, achieving a reliable measurement precision of 0.02 mm. These results highlight the system’s capability to provide accurate and non-contact displacement measurements in practical applications.

Future research will focus on extending the system’s range and resolution, integrating multi-sensor fusion techniques, and exploring applications in other infrastructure monitoring scenarios, such as suspension bridges and high-rise buildings.

Data availability

The data used to support the finding of this study are included within the article.

References

Wu, Y. Q., Huang, Z. R., Zhang, J. & Zhang, X. Y. Grouting defect detection of Bridge tendon ducts using impact echo and deep learning via a two-stage strategy. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 235, 112955 (2025).

Wu, Y. Q., Cai, D. Q., Gu, S., Jiang, N. & Li, S. L. Compressive strength prediction of sleeve grouting materials in prefabricated structures using hybrid optimized XGBoost models. Constr. Build. Mater. 476, 141319 (2025).

Bas, S., Apaydin, N. M., Ilki, A. & Catbas, F. N. Structural health monitoring system of the long-span bridges in Turkey. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 14 (4), 425–444 (2018).

Wu, Y. Q., Wang, Y. P., Li, D. & Zhang, J. Two-step Detection of Concrete Internal Condition Using Array Ultrasound and Deep Learning Vol. 139, 102945 (NDT & E International, 2023).

Hu, X. Y., Wang, B. W. & Ji, H. A wireless sensor network-based structural health monitoring system for highway bridges. Computer-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 28, 193–209 (2013).

Bedon, C., Berganmo, E., Izzi, M. & Noè, S. Prototyping and validation of MEMS accelerometers for structural health monitoring-the case study of the Pietragliata cable-stayed Bridge. J. Sens. Actuator Networks. 7, 30 (2018).

Guzman-Acevedo, G. M. et al. Accelerometer, and smartphone fused smart sensor for SHM on real-scale bridges. Adv. Civil Eng., 6429430. (2019).

Pan, B., Tian, L. & Song, X. L. Real-time, non-contact and Targetless Measurement of Vertical Deflection of Bridges Using off-axis Digital Image Correlation Vol. 79, 73–80 (NDT&E International, 2016).

Chen, Q. S. et al. Vertical deformation monitoring of the suspension Bridge tower using GNSS: a case study of the forth road Bridge in the UK. Remote Sens. 10, 364 (2018).

Liu, X. L., Lu, Z., Yang, W. X., Huang, M. & Tong, X. H. Dynamic monitoring and vibration analysis of ancient bridges by Ground-based microwave interferometry and the ESMD method. Remote Sens. 10, 770 (2018).

Zhang, Q. Z. et al. Galileo augmenting GPS single-frequency single-epoch precise positioning with baseline constrain for Bridge dynamic monitoring. Remote Sens. 11, 438 (2019).

Xia, Y., Zhang, P., Ni, Y. Q. & Zhu, H. P. Deformation monitoring of a super-tall structure using real-time strain data. Eng. Struct. 67, 29–38 (2014).

Yu, J. Y., Fang, Z., Meng, X. L., Xie, Y. L. & Fan, Q. Measurement of quasi-static and dynamic displacements of footbridges using the composite instrument of a smart station and an accelerometer: case studies. Remote Sens. 12, 2635 (2020).

Ma, Z. X., Chung, J., Liu, P. P. & Sohn, H. Bridge displacement Estimation by fusing accelerometer and strain gauge measurements. Struct. Control Health Monit. 28, e2733 (2021).

Moreu, F. et al. Dynamic assessment of timber railroad bridges using displacements. J. Bridge Eng., 20(10). (2014).

Nasimi, R. & Moreu, F. Development and implementation of a laser-camera-uav system to measure total dynamic transverse displacement. J. Eng. Mech., 147(8). (2021).

Shen, N. et al. Chen, R. Z. A review of global navigation satellite system (GNSS)-based dynamic monitoring technologies for structural health monitoring. Remote Sens. 11, 1001 (2016).

Wang, H. N., Dai, W. J. & Yu, W. K. BDS/GPS multi-baseline relative positioning for deformation monitoring. Remote Sens. 14, 3884 (2022).

Li, X. Y. & Li, F. Y. Displacement monitoring requirements and laser displacement monitoring technology of bridges with short and medium spans. Appl. Sci. 12 (19), 9663 (2022).

Kim, K. H. & Jung, H. K. Development of a remote displacement measuring laser system for bridge inspection. Sensors, 22(5), 1963. (2022).

Fukuda, Y., Feng, Q. M. & Shinozuka, M. Cost-effective vision-based system for monitoring dynamic response of civil engineering structures. Struct. Control Health Monit. 17, 918–936 (2010).

Khuc, T. & Catbas, F. N. Computer vision-based displacement and vibration monitoring without using physical target on structures. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 13, 505–516 (2017).

Xu, Y., Brownjohn, J. & Kong, D. A non-contact vision-based system for multipoint displacement monitoring in a cable-stayed footbridge. Struct. Control Health Monit., 25(5). (2018).

Tian, Y. D., Zhang, C., Jiang, S., Zhang, J. & Duan, W. H. Noncontact cable force Estimation with unmanned aerial vehicle and computer vision. Computer-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 36 (1), 73–88 (2021).

Shao, Z. L., Zhang, X. K., Li, Y. S. & Jiang, J. S. A comparative study on radar interferometry for vibrations monitoring on different types of bridges. IEEE Access. 6, 29677–29684 (2018).

Huang, Q. H. et al. Ground-based radar interferometry for monitoring the dynamic performance of a Multitrack steel truss high-speed railway Bridge. Remote Sens. 12, 2594 (2020).

Zhang, G. W., Wu, Y. L., Zhao, W. J. & Zhang, J. Radar-based multipoint displacement measurements of a 1200-m-long suspension Bridge. ISPRS J. Photogrammetry Remote Sens. 167, 71–84 (2020).

Zhang, B. C. et al. Dynamic displacement monitoring of long-span bridges with a microwave radar interferometer. ISPRS J. Photogrammetry Remote Sens. 138, 252–264 (2018).

Graves, W., Aminfar, K. & Lattanzi, D. Full-scale highway Bridge deformation tracking via photogrammetry and remote sensing. Remote Sens. 14, 2767 (2022).

Weng, J. H. et al. Fully automated and non-contact force identification of Bridge cables using microwave remote sensing. Measurement 209, 112508 (2023).

Pieraccini, M., Fratini, M., Parrini, F., Pinelli, G. & Atzeni, C. Dynamic survey of architectural heritage by high-speed microwave interferometry. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2, 28–30 (2005).

Gentile, C. Application of microwave remote sensing to dynamic testing of stay-cable. Remote Sens. 2, 36–51 (2010).

Olaszek, P., Swiercz, A. & Boscagli, F. The integration of two interferometric radars for measuring dynamic displacement of bridges. Remote Sens. 13, 3668 (2021).

Qin, X. Q. et al. A structure knowledge-synthetic aperture radar interferometry integration method for high-precision deformation monitoring and risk identification of sea-crossing bridges. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obsercation Geoinf., 103. (2021).

Zhao, Z. et al. Dynamic deformation measurement of Bridge structure based on GB-MIMO radar. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens., 60. (2022).

Zhai, Q. et al. A contactless on-bed radar system for human respiration monitoring. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 71, 4004210 (2022).

Wang, F. Y., Zeng, X. L., Wu, C. S., Wang, B. B. & Liu, K. J. R. Driver vital signs monitoring using millimeter wave radio. IEEE Internet Things J. 9, 13, 11283–11298 (2022).

Feng, X. et al. Millimeter-wave radar monitoring for elder’s fall based on multi-view parameter fusion Estimation and recognition. Remote Sens. 15, 8 (2023).

Xiong, Y. L., Li, S. X. & Meng, G. Theory and method of multi-point synchronous deformation and vibration measurement based on millimeter-wave sensing. Scientia Sinica Technologica. 51 (9), 998–1010 (2021).

Murakami, H., Fukuda, T., Otera, H., Kamo, H. & Miyoshi, A. Development of a High-Sensitivity Millimeter-Wave radar imaging system for Non-Destructive testing. Sensors 24, 4781 (2024).

Pagnini, L., Miccinesi, L., Beni, A. & Pieraccini, M. Transversal displacement detection of an arched Bridge with a multimonostatic Multiple-Input Multiple-Output radar. Sensors 24, 1839 (2024).

Xu, W. Vehicle load identification using machine vision and displacement influence lines. Buildings 14, 392 (2024).

Shi, L. F., Yin, W., Lv, Y. F. & Shi, Y. F. An improved radar echo signal processing algorithm for industrial liquid level measurement. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 71, 1008008 (2022).

Shamsfakhr, F., Macii, D., Palopoli, L., Corrà, M. & Ferrari, A. Fontanelli, D. A multi-target detection and position tracking algorithm based on mmWave-FMCW radar data. Measurement 234, 114797 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Financial Support of Science and Technology Projects of Jiangxi Provincial Department of Transportation (No. 2024ZG021, 2024YB055, 2024JT0018), the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF under Grant Number GZC20252154, and the Key Research Projects of Henan Higher Education Institutions (Grant No. 26A560021), and the Key Research and Development and Promotion Special Program of Henan Province (Grant No. 242103810071).

Funding

This research was funded by the Financial Support of Science and Technology Projects of Jiangxi Provincial Department of Transportation (No. 2024ZG021, 2024YB055, 2024JT0018), the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF under Grant Number GZC20252154, the Key Research Projects of Henan Higher Education Institutions (Grant No. 26A560021), and the Key Research and Development and Promotion Special Program of Henan Province (Grant No. 242103810071).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Zhixing Han; Data curation, Gangzong Xu and Yanqi Wu; Formal anal-ysis, Min Xiao and Zhixing Han; Investigation, Zhixing Han; Methodology, Wenju Zhao and Yanqi Wu; Resources, Jun Yu; Software, Jun Yu and Wenju Zhao; Validation, Jun Yu and Yanqi Wu; Writing – original draft, Min Xiao. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, M., Han, Z., Yu, J. et al. Development of a high-precision nano millimeter-wave radar system for non-contact bridge displacement monitoring. Sci Rep 16, 2030 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31631-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31631-9