Abstract

Research on the association of metal mixtures with glucose-insulin homeostasis is limited, and previous studies have typically focused on single metals. This study utilized data from 3110 adult subjects in the NHANES survey (2011–2018). Generalized linear models (GLM), logistic regression (LR), and restricted cubic splines (RCS) were employed to assess the associations of blood and urine metals with insulin resistance (IR) and glucose-insulin homeostasis. The Bayesian kernel machine regression (BKMR) and Bayesian weighted quantile sum (BWQS) models were further used to explore the independent and combined effects of metal exposures. In single-metal analyses, manganese (Mn) was positively correlated with insulin resistance (IR); cadmium(Cd), lead(Pb), mercury(Hg), and arsenic (As) were negatively correlated with the homeostasis model assessment of beta-cell function (HOMA-β); manganese and selenium (Se) were positively correlated with fasting plasma insulin (FPI); Se and cobalt (Co )were positively correlated with fasting plasma glucose (FPG); molybdenum (Mo) was positively correlated with HbA1c. In addition, both BWQS and BKMR models consistently showed that overall metal co-exposure had a positive effect on insulin resistance in the general population. Manganese was the most heavily weighted metal across all subgroups, with this association being more pronounced in males and individuals over 60 years of age. A negative association of metal mixtures with HOMA-β was observed in BWQS models. Furthermore, the analysis of BKMR models revealed possible interactions between insulin resistance and some components of metal mixtures in glucose homeostasis. The RCS model also identified nonlinear relationships between urinary Mo and HOMA-β, as well as between Co and both FPG and HbA1c. Our results suggest that metal mixtures may have adverse individual or combined effects on insulin resistance and glucose homeostasis in different population subgroups. These findings highlight the need for targeted interventions to mitigate the adverse effects of metal exposure on insulin-glucose homeostasis, which may provide new ideas for preventing and controlling the risk of type 2 diabetes due to metal exposure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The high prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)1 poses a serious threat to healthcare systems around the world, resulting in a heavy economic burden, and therefore a more comprehensive prevention and management of T2DM is urgently needed. Characteristics of glucose dysregulation in patients with T2DM include chronic hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction2. Therefore, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and insulin resistance (IR) are often considered as important biomarkers in the pathogenesis and progression of diabetes. IR is also an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD)3. In particular, insulin resistance and impaired β-cell function as a pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes usually precede the onset of type 2 diabetes by one to two decades4,5. Therefore, early diagnosis and management of insulin resistance and glycemic biomarkers can reduce the risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease, thereby significantly benefiting those at risk of diabetes and being important in the prevention and control of diabetes.

Although it has been shown that obesity6, genetic predisposition7, diet and lifestyle8 may cause disturbances in insulin sensitivity, however, the impact of environmental factors on disorders of glucose metabolism and diabetes mellitus is of increasing concern, and heavy metal pollution in particular has become an increasingly worrying public health problem. The main routes of human exposure to heavy metals in daily life are soil contaminated with heavy metals or inhalation of contaminated dust and exhaust gases9. Studies have shown that higher blood lead levels are associated with increased FPG10, and another prospective study showed a significant increase in FPG with increasing cadmium exposure11. However, this study found a negative correlation between Cd and fasting glucose and the risk of developing diabetes12. The debate on the effects of metal exposure on glucose-insulin homeostasis continues, however, most of the existing studies on the association between metal exposure and glucose homeostasis or risk of insulin resistance have focused on single metal exposure models13,14. However, the possible interactions of metal mixtures can attenuate the actual effects of individual metals15, and conventional models simply introduce interaction terms, which cannot deal with complex nonlinear interaction relations16. Therefore, it is necessary to consider new approaches to multi-pollutant modeling, in order to accurately assess the health effects of multi-pollutant statistical mixtures.

To date, multi-pollutant models have been used to investigate the relationship between metals and glucose-insulin homeostasis17; however, it is still not fully understood how these mixtures affect specific populations. Wang et al. used Bayesian kernel machine regression to identify a negative linear relationship between Mo and HOMA-IR, simultaneously reporting that zinc was inversely correlated with HOMA-β and that this association was strengthened at lower zinc levels18. Ge et al. reported a significantly negative overall effect of six metal mixtures (magnesium, iron, cobalt, selenium, strontium, and barium) on FPG levels in a Chinese occupational population study using BKMR modeling19. In contrast, Li et al. found no overall beneficial or detrimental effect of mixed metals on HbA1c using a model of BKMR20. There are also weighted quantile sum (WQS) regression models, which are commonly used in environmental health studies to assess the mixture effects of multiple co-occurring exposures and to identify important components of the mixture effect, However, WQS regression models21 also require an a priori selection of the directionality (positive or negative) of the coefficients associated with the mixture, so we used a new Bayesian extended WQS regression (BWQS)22to overcome its limitations and elucidate the joint effect of metal mixtures on glucose-insulin homeostasis. In addition, gender and age heterogeneity of the associations were less often assessed in previous studies. Therefore, more studies are urgently needed to investigate the relationship between exposure to metal mixtures and glucose-insulin homeostasis.

The aim of this study was to examine the association between co-exposure to single metals and mixtures of metals and glucose-insulin homeostasis in the general population using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) dataset using new contaminant analysis method.

Materials and methods

Study population

All research data for this study came from the NHANES database, a two-year research program designed to assess the health and nutritional status of adults and children in the U.S. All NHANES cycles were approved by the Ethical Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics and written consent was obtained from participants. For further information about NHANES, please visit https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.

This study included findings from four investigative cycles (2011–2018) involving 39,156 participants, excluding subjects under 20 years of age, missing metal level variables, missing HbA1c, FPG, insulin, urinary creatinine, and participants with FPG data less than 3.5 mmol/l were excluded because the HOMA-β index was to be calculated23, and the missing data for the other covariates were filled in by multiple interpolation, and a total of 3110 subjects were finally were included in this cross-sectional study. Details of participant selection are shown in Fig. 1.

Measurement of metals

In this study, blood samples were collected from participants by trained physicians. Whole blood and urine samples were stored at -30 °C until transported to the National Center for Environmental Health Laboratory for centralized analysis using inductively coupled plasma dynamic reaction cell mass spectrometry (ICP-DRC-MS). Five heavy metals (cadmium, lead, mercury, manganese, selenium) were measured in plasma, and two metals (cobalt, molybdenum) and one metalloid (arsenic) were measured in urine. We focused on plasma cadmium, lead, and mercury data reflecting recent exposure levels. Considering urinary dilution, urinary metal concentrations were expressed as creatinine-adjusted values (µg/g), calculated by dividing metal concentration by creatinine concentration. Detection rates exceeded 70% for all metals. Concentrations below the limit of detection were imputed according to NHANES guidelines (by dividing the limit of detection by the square root of 2), with results presented in Table S1. Prior to statistical analysis, all metal concentrations underwent logarithm (log10) transformation to satisfy normality assumptions.

Outcome ascertainments and definitions

Participants who underwent measurements for fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and insulin were required to fast overnight. FPG was measured using the hexokinase method, HbA1c was analyzed with a Tosoh HLC-723G8 automated analyzer. Serum insulin and triglycerides (TG) levels were determined by radioimmunoassay and enzymatic methods, respectively. The insulin resistance index (HOMA-IR) was calculated by [FPG × FPI ÷ 22.5]24, higher HOMA-IR values indicate an increased risk of insulin resistance, which is defined as HOMA-IR > 2.5 in adults25. Pancreatic β-cell function index ( HOMA-β) was calculated by [ (20 × FPI) ÷ ( FPG − 3.5) ]23, FPG is mmol / L and FPI is µIU / mL, and lower HOMA -β values suggest a decrease in pancreatic β-cell function.

Covariable

The selection of covariates in this study was guided by prior literature and included established potential confounders for insulin resistance, blood glucose levels, and body metabolism. Included were age(20 ≤ age ≤ 59,age ≥ 60), gender (male/female), race (Mexican American, Other Hispanic, Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Other), educational attainment (less than 9th grade, 9-11th grade, high school grade, college and above, some college or AA degree), smoking status (never, former, current), average number of drinks per day in the past year (0, < 5, 5–10, > 10), physical activity (none, moderate, vigorous, both moderate and vigorous), household income poverty ratio (PIR), body mass index (BMI, kg/m2, ≤25, 25.1–29.9, ≥ 30 kg/m2), use of glucose-lowering medication (for glucose homeostasis) (yes or no), hypertension was defined as an individual with a self-reported physician, or a three-measurement average of blood pressure 140/90 mm Hg, or current use of antihypertensive medication, hypertension (yes or no). Hyperlipidemia was defined if any of the following criteria were met ① TG ≥ 150 mg/dL, ② TC ≥ 200 mg/dL (5.18mmol/L), ③ LDL-C ≥ 130 mg/dl (3.37mmol/L), ④ HDL-C < 40 mg/dL (1.04mmol/L) (male) or 50 mg/dL (1.3mmol/L) (female), ⑤ Taking lipid-lowering drugs or a diagnosis of hyperlipidemia (yes or no).

Statistical analysis

The data in this study were analyzed using the programming language R (version 4. 2. 3, R Core Team, Vienna, Austria). We used the mice package to perform multiple imputation of missing values via chained equations (all variables had a missing rate < 10%). Categorical variables are expressed in terms of sample size (n) and frequency (%), and continuous variables that are not normally distributed are expressed in terms of median (IQR = Q75 - Q25). For between-group comparisons of unbalanced variables, we used the Wilcoxon rank-sum test to examine rates of change in categorical variables between groups, a two-sided test of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Logarithms (log10) were applied to FPG, HbA1c, insulin, HOMA-IR, and HOMA-β to improve normality. Spearman’s correlation analysis was employed to determine correlations between concentrations (log10-transformed) of eight metals and metalloids. Correlation coefficients were categorized as weak (≤ 0.3), moderate (> 0.3 and ≤ 0.8), or strong (> 0.8). The variance inflation factor (VIF) was used to assess multicollinearity among independent variables. A VIF greater than 10 indicates severe multicollinearity.

Generalized linear regression model (GLM)

Generalized linear models (GLMs) were employed to independently assess the associations of individual metals and metalloids with continuous outcomes, including HOMA-IR, HOMA-β, FPG, HbA1c, and FPI. First, metal concentrations were transformed into quartiles and included as categorical variables to explore potential nonlinear trends. Subsequently, logistic regression models were used to examine the relationship between metal quartiles and insulin resistance, with the first quartile (Q1) serving as the reference group. P-values for trend were calculated by treating the quartiles as continuous variables in the models. Additionally, metal concentrations were ln-transformed and modeled as continuous variables to quantify the strength of linear associations. To explore potential differences by genders and age, we analyzed the relationships between metals/metalloids and insulin resistance and glucose homeostasis indicators separately in each sex and in the two age groups (20–59 years, ≥ 60 years), each model included an interaction term, with the interaction effect estimated using likelihood ratio tests. Furthermore, threshold effects were examined using piecewise regression analysis.

Bayesian kernel machine regression (BKMR) model

Bayesian kernel machine regression (BKMR) modelling is a novel approach to assessing mixture effects without the need to set up parametric expressions, allowing for non-linear effects and interactions, and performing both variable selection and health effect estimation15,26. In this study, we screened variables and constructed Gaussian functions for all BKMR models using a Monte Carlo algorithm with 25,000 iterations to assess the individual and joint effects of metal exposure on insulin resistance and glucose homeostasis, including potential non-linear relationships and interactions, and to estimate a posteriori inclusion probabilities (PIPs), with probabilities closer to 1 representing a greater contribution of the pollutant, which provide for each exposure a measure of variable significance.

Bayesian weighted quantile sum (BWQS) regression model

The BWQS model regression22 is a new and efficient method for assessing the effects of mixture exposure without the need to a priori select the directionality of the association, thus improving the statistical efficiency, flexibility and stability of the model. The estimated coefficients mapped to the mixture in the BWQS model (Beta1) identify the association between the overall mixture and the outcome, while the estimated coefficients mapped to the weights identify the relative contribution of the corresponding components to the mixture. We used the Hamilton-Monte Carlo algorithm to compute all posterior probability distributions, with the refinement parameter set to 1, and 2 Markov chains, each with 5000 bootstrap iterations to determine the effect weights for each metal.

Sensitivity analysis

In order to validate the robustness of our findings, First, we applied restricted cubic spline RCS regression, selecting four nodes (corresponding to the 5th, 35th, 65th, and 95th percentiles) to examine the dose-response relationship of individual metal exposure in relation to IR and glucose-related indicators, then linear and logistic regression modelling was performed in a non-type 2 diabetic population, and finally, due to the complexity of the NHANES sampling design, we adjusted for sampling weights to statistically describe the population by race. We then performed weighted logistic and linear regression including all metals in the model to adjust for potential confounders. Simultaneously, a directed acyclic graph (DAG) was constructed using the online tool DAGitty (URL: www.dagitty.net)27 to determine whether potential covariates should be adjusted for in the model. From the DAG (Fig.S1), a minimal set of adjustment variables (age, education, sex, smoking, and PIR) was retained. Finally, given the low detection ratest of metals Cd and Hg, we conducted a sensitivity analysis after imputation using the limit of detection (LOD).

All analyses were performed using R software (version 4.2.3) for BWQS regression, BKMR analysis of RCS regression, and threshold effect analysis using the BWQS, bkmr, rms, and segmented packages, respectively. p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of all participants. The total number of participants was 3,110, of which 1,574 were men and 1,536 were women. The overall age distribution was 20–59 years (65.76%) and ≥ 60 years and over (34.24%). For both men and women, non-Hispanic whites and those with Some College or AA degree education were the most dominant racial and educational groups. The gender distribution across different BMI categories showed significant differences (p < 0.001). The overweight group (25.1–29.9 kg/m²) was predominantly male (36.09%), while the obese group (≥ 30 kg/m²) was predominantly female (42.38%). The results also showed that the intensity of physical and work activities, the number of drinking and smoking status were significantly higher in men than in women, with statistically significant differences between the two groups. The prevalence of hypertension is higher in men than in women, while the prevalence of hyperlipidaemia is slightly higher in women than in men. Men had higher FPG levels, whereas women had a higher HOMA-β index (both p < 0.001). However, no significant differences were observed between gender in the prevalence of IR, HOMA-IR, and FPI (all p > 0.05).

Distribution and correlation of metallic substances in blood and urine

We characterised the distribution of metal elements by different population groups and the results are shown in Table 2. The concentrations of Cd and Mn in plasma were significantly lower in male than in female, while the concentration of Hg also showed a tendency to be lower in male, though this did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.07). In contrast, plasma concentrations of Pb and Se were significantly higher in male than in female, and urinary concentrations of Co, Mo and As were higher in female than in male. Plasma Cd, Pb and Hg concentrations were significantly higher in the elderly group than in the 20–59 years group, whereas plasma Mn concentrations were significantly lower, urinary concentrations of Co, Mo and As were higher in the elderly group than in the 20–59 years group, the difference was statistically significant (p < 0.001). The spearman correlation matrix analysed the correlation between the eight metal concentrations (log10-transformed) (Fig. S2), As was moderately correlated with Hg (r = 0.57), Cd with Pb (r = 0.35), and the other metals were less correlated. All variance inflation factors (VIF) were less than 5 (results not shown), indicating low multicollinearity between the respective variables.

Correlation of individual metals in plasma/urine with HOMA-IR, HOMA-β, FPG, HbA1c, FPI and IR

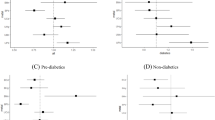

Fig. 2 shows the results of univariate linear regression and logistic regression models after adjusting for all covariates.

Linear regression results indicate that compared with Q1, HOMA-IR was significantly positively correlated with Mn and Se in Q4, with β values (95% CI) of (β = 0.066, 95% CI: 0.034, 0.099) and (β = 0.047, 95% CI: 0.015, 0.079), respectively. For HOMA-β, Mn showed a significant positive correlation (β = 0.076, 95% CI: 0.045, 0.107), while metals Cd, Pb, Hg, and As all showed significant negative correlations. Insulin showed negative correlations with Cd, Pb, and Hg, and positive correlations with Mn (β = 0.071, 95% CI: 0.041, 0.100) and Se (β = 0.037, 95% CI: 0.008, 0.065). FPG was positively correlated with Se (β = 0.011, 95% CI: 0.002, 0.019) and Co (β = 0.013, 95% CI: 0.004, 0.022). HbA1c was positively correlated with metal Mo (β = 0.010, 95% CI: 0.005, 0.015). Logistic regression results for Mn indicated that the odds of insulin resistance were significantly higher for individuals in quartile Q4 than for those in Q1 (OR = 1.376, 95% CI: 1.071, 1.770). Table S2 presents the results of incorporating eight metals as continuous variables into fully adjusted models. HOMA-IR and HOMA-β demonstrated consistent associations in continuous analyses (all P values < 0.05). Notably, the association between Co and FPG differed from the others, shifting from a positive correlation to non-significance.

Subgroup analysis of the association between urine/plasma metal and HOMA-IR, HOMA-β, FPG, HbA1c, FPI

To evaluate potential interaction effects, we performed stratified analyses by age (20–59 and ≥ 60 years) and sex. The results (Tables S3-S7) demonstrated that plasma Se showed a significant sex interaction with HOMA-IR (P-interaction = 0.046); urinary Co exhibited a significant sex interaction with HOMA-β (P-interaction = 0.049); and plasma Pb displayed significant age interactions with both FPG (P-interaction = 0.016) and HbA1c (P-interaction < 0.001). Additionally, urinary Mo consistently showed positive correlations with HbA1c across all subgroups (all P-trend < 0.05). Both plasma Cd and Hg were associated with decreased FPI, with Cd affecting the < 60 years subgroup and females, while Hg affected the < 60 years subgroup and males.

Subgroup analysis of metals and insulin resistance in urine/plasma and threshold effect analysis of Mn levels and IR.

Logistic regression subgroup analyses (Table 3) showed that insulin resistance was significantly and positively associated with Mn in the male (OR = 1.465, 95% CI: 1.000, 2.149) and ≥ 60 years (OR = 1.749, 95% CI: 1.140 2. 695) subgroups and with Se in the ≥ 60 years subgroup (OR = 1.609 95% CI: 1.070, 2.425).

In addition, we focused on the effects of the levels of these eight metals on insulin resistance (HOMA-IR ≥ 2.5). Table S8 showed that plasma Mn and Se concentrations were higher in IR patients than in non-IR patients, and Cd, Pb, and Hg concentrations were lower than those in non-insulin-resistant patients; whereas urinary Co and As concentrations were lower than those in non-insulin-resistant patients. The RCS curve showed (Fig. S10) that there was no non-linear relationship between Mn and IR (P-overall = 0.029, P-non-linear = 0.296; we further performed the analysis of the threshold effect of Mn on IR by two-stage linear regression (Table S9). In the overall population, when plasma manganese levels were below the inflection point (logMn = 1.17, Mn = 14. 94ug/l), each unit increase in manganese concentration was associated with an elevated risk of insulin resistance (OR = 3.072, 95% CI: 1.443–6.537). However, when manganese levels exceeded this inflection point, the association was no longer statistically significant (P > 0.05). Although the overall likelihood ratio test for the segmented model did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.147), the significant association observed below the inflection point suggests the potential existence of a critical concentration for the effect of manganese on insulin resistance. Additionally, restricted cubic splines were used to examine the dose-response relationships between plasma manganese levels and insulin resistance across sex and age subgroups (Fig. 3.A-B). In the age subgroup analysis, individuals over 60 years old appeared more susceptible to insulin resistance risk, which is consistent with the results from the logistic regression models.

The dose-response relationship in different people between Mn and the IR: (A) Sex, (B) Age. In total the model was adjusted for covariates including age, gender, race/ethnicity, education level, poverty income ratio, body mass index, smoking status, drinking status, physical activity, use of antidiabetic medication, hypertension and hyperlipidemia. In the sex group models adjusted for the same as total with the exception of sex. In the age group models adjusted for the same as total with the exception of age.

Bayesian kernel machine regression (BKMR) model

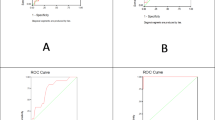

This study employed the BKMR model to evaluate the combined effects of eight metal mixtures on glucose homeostasis indicators (Fig. 4). Results showed that across all subgroups, insulin resistance risk increased with rising metal mixture exposure. Specifically, when all metal concentrations exceeded the 50th percentile, the metal mixture showed significant positive associations with both FPG and HbA1c in the total population. The relationship between the metal mixture and HOMA-β exhibited a biphasic trend: decreasing below the 50th percentile, then increasing after the 60th percentile. Additionally, HOMA-IR and FPI levels increased consistently with higher metal mixture exposure.

The posterior inclusion probability (PIP) represents the extent to which each metal in the metal mixture contributes to glucose homeostasis, and we observed that the metals with the greatest effect on HOMA-IR, HOMA-β, and FPI in the overall population were Mn and Pb (both with PIPs approximately equal to 1), specifically, Mn showed the most prominent effects on insulin resistance-related indicators in the total population (PIP = 1), males (PIP = 0.91), and females (PIP = 0.76); Co demonstrated the greatest influence on FPG in the overall participants (PIP = 0.94), males (PIP = 0.90), and those aged < 60 years (PIP = 0.96). Meanwhile, in the subgroup aged ≥ 60 years, Pb was identified as the most significant metal affecting HbA1c (PIP = 1) (Fig. 5).

Fig S3(A-B) presents the trend of the exposure-response function of eight metals, we found that Pb, Mn and HOMA-IR showed a decreasing and then increasing relationship in the whole population when all other metals were at moderate levels, which may have a potential non-linear relationship, and Pb was negatively correlated with HOMA-IR in the subgroups of sex and age. In addition, Co showed a significant non-linear relationship with FPG in the total population and in men and subgroups younger than 60 years.

Bivariate exposure-response curves (Fig. S4), where each cell represents the exposure-response curve for the column metals when the row metals are in different quartiles 25th (red line), 50th (green line), and 75th (blue line)) and the other metals are at the median. We observed interactions between HOMA-IR, FPI, HOMA-β, IR and metal mixtures in different subgroups. Specifically, in the overall population, as Mn concentrations increased from the 25th to the 75th percentile, HOMA-IR and IR showed interactions with Pb and Se respectively, while the slope of lead’s effect consistently decreased. In the female population, all metals except Mo demonstrated interactions with Mn in relation to IR, exhibiting nonlinear response curves. For FPI, Pb interacted with Mo or Hg in the overall population and male subgroup respectively, while in the ≥ 60 years subgroup, Pb interacted with both Co and Mo. Regarding HOMA-β, Pb interacted with Hg and Mo in the overall population, and with Hg in the < 60 years subgroup. However, no significant metal-metal interactions were observed for FPG and HbA1c in any population subgroups.

Overall effect (95% CI) between metal mixtures and six indicators of glucose homeostasis based on Bayesian kernel machine regression, defined as the difference in the glucose homeostasis index when all metals are fixed at a specific percentile (between the 25th and 75th percentiles) compared to when all metals are fixed at their median (50th percentile). In total the model was adjusted for covariates including age, gender, race/ethnicity, education level, poverty income ratio, body mass index, smoking status, drinking status, physical activity, use of antidiabetic medication, hypertension and hyperlipidemia. In the sex group models adjusted for the same as total with the exception of sex. In the age group models adjusted for the same as total with the exception of age.

The relative importance of each metal on glucose homeostasis and risk of prevalent insulin resistance based on Bayesian kernel machine regression (PIP). In total the model was adjusted for covariates including age, gender, race/ethnicity, education level, poverty income ratio, body mass index, smoking status, drinking status, physical activity, use of antidiabetic medication, hypertension and hyperlipidemia. In the sex group models adjusted for the same as total with the exception of sex. In the age group models adjusted for the same as total with the exception of age.

Bayesian weighted quantile sum (BWQS) regression model

In the BWQS model we observed (Fig. 6A) that each quartile increase in the 8 metal mixtures was significantly associated with higher insulin resistance risk in the overall population, with a coefficient of 0.285 (95% CI: 0.155, 0.438), corresponding to an adjusted OR of 1.330 (95% CI: 1.168, 1.550). Stratified analyses showed that the adjusted OR for insulin resistance per quartile increase in the metal mixture was 1.365 (95% CI: 1.095, 1.705) in males, but non-significant in females, which was not statistically significant. By age subgroup, the risk of IR was significantly increased with each quartile increase in the metal mixture, with an adjusted ORs of 1.301 (95% CI: 1.051, 1.575) for individuals aged 20–59 years and 1.403 (95% CI: 1.047, 1.755) for those aged 60 years or older. In the total population, each quartile increase in metal mixture concentration was significantly associated with HOMA-IR (β = 0.041; 95% CI: 0.021, 0.060), HOMA-β (β = -0.049; CI: -0.070, -0.027), FPI (β = 0.036; CI: 0.022, 0.051), FPG (β = 0.011; CI: 0.005, 0.017) and HbA1c (β = 0.006; CI: 0.002, 0.009). Among males, metal mixtures were positively associated with HOMA-IR (β = 0.050; CI: 0.022, 0.076), FPI (β = 0.042; CI: 0.010, 0.063) and FPG (β = 0.010; CI: 0.000, 0.015); In females, metal mixtures were positively associated with FPG (β = 0. 010; CI: 0.002, 0.018) and HbA1c (β = 0.008; CI: 0.004, 0.013), but negative associations with HOMA-β (β = -0.058; 95% CI: -0.081, -0.037) and FPI (β = -0.038; 95% CI: -0.065, -0.007). Additionally, significant associations between metal mixtures and glucose homeostasis markers were observed in the 20–59 age group, but not in participants aged 60 or older.

The extent to which individual metals contributed to glucose homeostasis and insulin resistance varied by subgroup (Fig. 6B); for HOMA-IR, the top two weights in the overall population were Pb and Mn, in the male subgroup Mn and Co, in the female subgroup Pb and Cd, and the highest weights in the age subgroup were Pb and Mn; for HOMA-β, the top two metals with the highest contribution of mixtures in each subgroup were Pb and Hg. For FPI, in the total population and in the 20–59 years old, the top two contributors were Mn, Se, in the male subgroups Mn, Co, and in the female subgroups Pb, Cd. Mn had the greatest weight in the ≥ 60 years old, with the remaining mixture components contributing approximately equally. For FPG, Se and Co contributed most, except in the ≥ 60 subgroup where Pb had the greatest weight, and for HbA1c, elemental Mo had the greatest weight in the mixture component in all participants and gender subgroups, and Pb had the greatest weight in all age subgroups; for insulin resistance, Mn ranked first in terms of its contribution both in the total population and in the other subgroups,, and these results are similar to the posterior inclusion probability (PIP) in the BKMR model.

Associations between urinary/plasma metal and glucose homeostasis and insulin resistance using BWQS regression (A) Estimates (coefficients) of the association between mixture and glucose-insulin homeostasis.(B) Weights with 95% credible intervals for each mixture component. In total the model was adjusted for covariates including age, gender, race/ethnicity, education level, poverty income ratio, body mass index, smoking status, drinking status, physical activity, use of antidiabetic medication, hypertension and hyperlipidemia. In the sex group models adjusted for the same as total with the exception of sex. In the age models adjusted for the same as total with the exception of age.

Sensitivity analysis

To ensure the robustness of the results, an optimal 4-node restricted cubic spline (RCS) was used to analyse the dose-response relationship between metal elements and glucose homeostasis (Fig. S5-S10). We found linear dose-response relationships between gold Cd, Pb, Mn and Se (P-overall < 0.05 ,P-non-liner ≥ 0.05) and HOMA-IR increased with increasing concentrations of Mn and Se, in contrast to the decreasing trend of HOMA-IR with increasing concentrations of Cd and Pb. A possible non-linear dose-response relationship between HOMA-β and Mo (P-non-liner = 0.031) was verified, as well as a linear dose-response relationship between Se (P-non-liner ≥ 0.05) and FPG, and a significant non-linear dose-response relationship between Co (P-non-liner < 0.001) and FPG.

After excluding 703 patients with T2D (22.6%), the association of metal levels with HOMA-IR, HOMA-β, HbA1c, insulin, and IR was still observed after inclusion of the fully adjusted model with continuous variables (Table S10).

We used complex sampling design subsample weights to categorize the population by race and found that, as shown in Table S11, Mexican Americans had the highest median HOMA-IR and the highest prevalence of insulin resistance, non-Hispanic whites had the lowest median HOMA-β, people of other races had the highest median Cd, Pb, Hg and Mn, and As, and Se was as high as in non-Hispanic whites, and other ethnicities had the highest median levels of Co; non-Hispanic whites had the highest levels of Co, and levels of Mo were as high in Mexican Americans, other Hispanics, and non-Hispanic blacks. Weighted linear and logistic regression models in Table S12 showed significant associations between individual metal concentrations and glucose-insulin homeostasis, with Pb being significantly and negatively associated with HOMA-IR, HOMA-β, and FPI, and Mn remaining significantly and positively associated with insulin resistance. After adjusting for covariates selected based on a directed acyclic graph (DAG), the main results remained robust (Fig S11). After imputation using the LOD, the results for Cd and Hg were analyzed and are provided in Fig. S12.

Discussion

Our results indicate that all eight metals (Cd, Pb, Hg, Se, Mn, Co, Mo, and As) are associated with glucose homeostasis and insulin resistance. Specifically, when blood metal concentrations increased from the 25th percentile (P25) to the 75th percentile (P75) of the population distribution, Mn was associated with an increase in HOMA-IR of 0.066 units, while Cd, Pb, Hg, and As were associated with decreases in the HOMA-β of 0.088, 0.113, 0.081, and 0.122 units, respectively. Individuals at the P75 level of Mn exposure had a significantly higher risk of IR increased by 37.6% compared to those at the P25 level. Significant interaction effects were observed, plasma Se showed a significant sex interaction with HOMA-IR; urinary Co exhibited a significant sex interaction with HOMA-β; and plasma Pb displayed significant age interactions with both FPG and HbA1c. The BKMR model revealed that mixed metal exposure significantly increased the risk of insulin resistance, with Mn identified as the primary risk factor, a finding supported by the BWQS model.

This study observed significant negative correlations between plasma concentrations of Cd, Pb, and Hg and HOMA-β, suggesting that metal exposure may adversely affect pancreatic β-cell function. This finding differs from a Korean study28, which reported no significant associations between plasma Cd, Pb, and Hg exposure and HOMA-IR or HOMA-β, potentially due to differences in study populations, exposure levels, and research design. Although the mechanism underlying Cd and insulin resistance remains unclear, experimental studies have shown that Cd exposure can promote inflammatory lipid accumulation and impair β-cell function29,30 Our findings provide epidemiological evidence supporting the adverse effects of elevated Cd exposure on β-cell function. The relationship between Pb exposure and glucose homeostasis remains inconsistent in the literature10,18. Some studies have reported no association between urinary Pb and diabetes or glucose metabolism31, while notably, a nested case-control study in a Chinese population32 found that participants in the highest plasma Pb group had a significantly reduced risk of T2DM compared to those in the lowest group. The association between mercury exposure and diabetes is also unclear. Although one epidemiological study18 found no link between Hg and HOMA-IR or HOMA-β, experimental research suggests that methylmercury may induce β-cell toxicity through reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent pathways33,34. Further investigation is needed to clarify the potential metabolic impacts of mercury.

Contrary to our hypothesis, this study found that plasma levels of cadmium, lead, and mercury were inversely associated with the insulin resistance index, which contradicts most existing literature. These results should be interpreted with caution and should not be simply construed as evidence of a protective effect of metal exposure. The most plausible explanation is the presence of unmeasured or residual confounding. For example, impaired renal function is a key confounder, as it not only reduces the clearance of metals, leading to their elevated concentrations in blood35, but is also an independent risk factor for insulin resistance36. Although we adjusted for multiple covariates, we cannot fully rule out residual confounding due to renal function or other insufficiently measured factors, such as micronutrient status. Furthermore, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inference and cannot eliminate the possibility of reverse causality. These inverse associations are more likely to reflect methodological limitations rather than genuine biological effects. Another possibility is that these inverse correlations represent a statistical artifact caused by unaccounted antagonistic effects within the context of real-world co-exposure to multiple metals. Therefore, the observed inverse associations are more likely to reflect methodological limitations of the present study rather than true biological effects. Future prospective studies are needed to clarify the true relationship between these metals and glucose metabolism.

Under current environmental conditions, increased levels of pollutants such as cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb), and methylmercury (MeHg) can produce amplification effects through the food chain37. In non-industrial areas or typical urban-rural environments, metals can enter the food chain through water, soil, or processing, making certain foods (e.g., rice, fish) significant sources of exposure to metals like Pb, Cd, and As38 Residents who regularly consume specific products may face dietary exposure risks. This study primarily focuses on environmental media and does not include dietary assessments, which may underestimate total exposure levels. Therefore, subsequent research should incorporate food surveys to comprehensively evaluate health risks.

In our study, higher plasma Mn levels were significantly and positively correlated with HOMA-IR, HOMA-β, FPI, and insulin resistance, a finding consistent with prior studies39,40. Our study identifies a threshold effect of plasma Mn levels in relation to insulin resistance and provides new epidemiological evidence for the detrimental role of Mn in glucose metabolism. Studies have shown that either a deficiency or excess intake of Mn can increase reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to mitochondrial dysfunction41; on the one hand, oxidative stress impairs pancreatic β-cell function42and affects insulin secretion; on the other hand, oxidative stress also induces insulin resistance by affecting insulin signalling pathways43. We also found that the effect of Mn levels on insulin resistance was greater in men and in older populations, it has been shown that women absorb more Mn from a diet with the same Mn content than men, but women have a shorter half-life of Mn44, in this study, plasma Mn levels were higher in women than in men. A cross-sectional study showed that high plasma Mn levels were independently associated with a lower prevalence of prediabetes in older women. Moderate plasma Mn levels were independently associated with a lower prevalence of prediabetes and diabetes in older men45. Despite the fact that Mn, as an essential element, and has known health benefits related to antioxidant properties and energy metabolism, our results suggest the need to consider that excessive intake of Mn increases the risk of insulin resistance, especially in susceptible populations such as men and the elderly.

In our present study it was observed that urinary levels of Co and Mo were higher in women than in men, and higher concentrations of Co and Mo were positively correlated with FPG and HbA1c, and it has been shown that adult women have higher cobalt absorption and lower cobalt excretion rates than adult men46, in this one study47, similar results were observed. Our study also showed an inverted U-shaped relationship between Co and HbA1c, a dose-response relationship between Mo levels and HOMA-β, and a U-shaped relationship between Co levels and HOMA-β. This suggests that Co and Mo may influence diabetes progression through pancreatic β-cell regulation, and further studies are needed to explore the mechanism of the role of Co and Mo in the development of T2D.

Se, an essential trace element, maintains biological functions through the action of Se proteins, which protect against oxidation and inflammation and are involved in glucose metabolism. In our current study, a significant positive correlation was observed between plasma Se levels and FPG, HOMA-IR index and insulin, this is consistent with the results of previous epidemiological studies, Cardoso et al.48showed that high plasma Se levels were still positively correlated with insulin and HOMA-IR after adjustment for confounders; Li et al.49observed that plasma Se levels had a negative effect on FPG in areas with high metal concentrations. Some in vitro experiments suggest that high levels of selenoproteins may impair insulin signalling in liver and muscle and disrupt glucose homeostasis in vivo50. Although we did not observe an association between quartile Se concentrations and insulin resistance, we found that after performing age-stratified analysis, a significant positive correlation between quartile Se concentrations and insulin resistance was observed in the elderly group. Additionally, a significant gender interaction was present between plasma Se and HOMA-IR. Our findings further substantiate the association between plasma selenium and insulin resistance. Our findings provide further evidence for the link between plasma Se and insulin resistance. These studies suggest that exposure to excess Se may affect diabetes and related markers, and further studies are needed to determine the optimal intake of Se in different populations to minimise potential adverse effects on glucose metabolism and prevent type 2 diabetes.

Our study found a trend of decreasing HOMA-β with increasing quartiles of urinary arsenic levels, consistent with the findings of this prospective study that arsenic is associated with a faster rate of HOMA-β decline18. In another experimental study it was found that diabetic mice with diabetes after exposure to inorganic arsenic had a lower HOMA-β index than that of normal mice51, whereas no significant change in the HOMA-IR index was observed. Our study did not observe a correlation between As and insulin resistance, suggesting that arsenic does not exacerbate insulin resistance, but rather impairs pancreatic β-cell function to increase gluconeogenesis, thereby exacerbating diabetes risk. Future studies need to explore the biological mechanisms underlying the association between metal As and insulin resistance.

In addition, the BWQS model suggests that the metals Mn, Se, and Mo play crucial roles in HOMA-IR, HOMA-β, FPI. Co-exposure to metals increased the risk of developing insulin resistance, with a mixed effect mainly driven by the metals Mn and Se. HOMA-IR was significantly positively correlated after the 50th percentile, again suggesting that metal exposure increases the risk of insulin resistance. Notably, a metal interaction was also observed in the BKMR model, with Mn interacting with all other metals (except Mo) in a subset of insulin resistant women, a result that emphasises the important role of Mn in insulin resistance and thus the need for further studies to elucidate the mechanism of the role of Mn in insulin resistance. In addition, interactions between plasma Pb, Hg, Mo, Mn and Se were found in insulin resistance (IR) as well as in other glucose homeostasis, a result that emphasises the role of blood Pb in glucose metabolism, but the exact mechanism is not clear and it is possible that disruption of metal homeostasis is involved52.This is one of the few current studies, therefore further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanism of blood Pb interaction with more other metals.

Our findings indicate that gender specifically modulates the relationship between different types of metal exposure and glucose homeostasis: males are more susceptible to essential metals (Mn, Se), while females exhibit greater sensitivity to non-essential toxic metals (Cd, Pb).Males and females have different effects on environmental exposures, which may be due to hormonal, genetic, anatomical, epigenetic, or metabolic gender dimorphism53. In addition, the levels of other essential elements in the body can affect the absorption and toxicity of metals and cause interactions, such as iron deficiency, which is more common in women than in men54. We also found that the concentrations of metals other than Mn and Se were higher in the older group, and we believe this may be related to ageing, which has recently been found to be a critical turning point in the ageing process around the age of 60 years55. Therefore, future studies need to be stratified by sex and age and to analyse more information on lifestyle and social status in relation to metal exposure in order to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the endocrine toxicity of environmental metals and to help develop more effective systematic risk assessment methods and exposure reduction strategies.

The BKMR model can be used not only to assess potential non-linear dose-response but also to visualise interactions between metals, thus providing a more comprehensive assessment of individual and combined effects of metals. The BWQS model allows the estimation of individual weighted indices to summarise the overall exposure to a mixture of metals, while the use of weights to take into account the individual contribution of each concentration in the mixture, without a priori specification of the direction of an individual effect on the overall mixture, overcomes the assumption of unidirectionality.

The primary strengths of this study are as follows: First, we systematically evaluated the nonlinear threshold effects and gender/age-specific relationships between plasma Mn levels and insulin resistance. Second, by integrating multiple mixture statistical models, we revealed associations between metal mixtures and glucose homeostasis. Third, correction for urinary creatinine ensured the accuracy of metal exposure assessments. However, some of its limitations should also be recognized, first, the data used in this study were derived from a cross-sectional survey and there was no longitudinal follow-up of steady-state glucose and metal concentrations, which means that causality cannot be assumed as reverse causality may exist, therefore, our findings require further validation in prospective cohort studies or mechanism studies. Second, we rely on single-measurement blood/urine metal concentrations, which primarily reflect recent exposure and are influenced by inter-individual variability. This non-differential misclassification of exposure likely leads to an underestimation of the true association between metals and health outcomes. Additionally, while the handling of non-detected values in this study involves inherent limitations, the impact on metals with high detection rates (≥99%) is negligible. The robustness of the conclusions for metals with lower detection rates (e.g., Cd and Hg) is further supported by a stress-test analys is using LOD imputation.Third, the biological half-lives of the metals we measured vary considerably, ranging from days to decades, a factor that must be considered when assessing long-term health risks. Future studies employing repeated-measurement designs or utilizing matrices reflecting long-term burden (e.g., bone lead) will help validate our findings. Fourth, although every effort has been made to adjust for potential confounding factors, residual confounding from unmeasured variables may still introduce bias into the results. The direction of this bias is complex and may not be uniform. For example, unmeasured detailed dietary patterns (such as overall health-conscious food choices) might be associated with both lower metal exposure levels and a lower risk of insulin resistance, potentially leading to an overestimation of the harmful effects of metals. Conversely, the intake of specific nutrients with chelating or antioxidant properties (e.g., selenium, vitamin E, phytochelatins) may mitigate the metabolic toxicity of metals without necessarily reducing exposure levels. If individuals with better glucose homeostasis consume more of these protective nutrients, the true harmful effects of metals could be underestimated in our analysis. Other potential unmeasured confounders include specific occupational exposures and more granular socioeconomic factors. Although the consistency of our findings across multiple models is reassuring, the influence of these unmeasured factors cannot be completely ruled out. Future studies incorporating more detailed dietary and occupational data are warranted to confirm our findings. Fifth, this study conducted multiple statistical tests, which may increase the risk of Type I errors. Although we exercise great caution in our interpretations, these findings still require replication in independent studies. Finally, this study was conducted in US adults, and the findings may not be applicable for extrapolation to children or other developing countries and still need to be explored in different study populations. Nevertheless, our study provides a new scientific basis for research on the association between combined metal exposure and glucose-insulin homeostasis.

In conclusion, our study suggests that metal mixtures may have adverse individual or combined effects on glucose-insulin homeostasis, and different effects were found in subgroup analyses for different sex and age populations, suggesting that environmental metal exposures may predispose to sex- and age-dependent disturbances of glucose-insulin homeostasis in the general adult population, and identifying a significant association of Co with FPG and HbA1c, Mo The non-linear dose-response relationship with HOMA-β suggests that there is an urgent need to control our metal intake and exposure; Further research is needed to determine the causal relationship between these variables.

Data availability

The datasets used in this study are freely available from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). The data can be accessed at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- Cd:

-

Cadmium

- Pb:

-

Lead

- Hg:

-

Mercury

- Mn:

-

Manganese

- Se:

-

Selenium

- Co:

-

Cobalt

- Mo:

-

Molybdenum

- As:

-

Arsenic

- HOMA-IR:

-

Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance

- HOMA-β:

-

Homeostasis model assessment of beta-cell function

- FPI:

-

Fasting plasma insulin

- IR:

-

Insulin resistance

- FPG:

-

Fasting plasma glucose

References

Collaborators, G. B. D. D. Global, regional, and National burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet 402, 203–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01301-6 (2023).

Abdul-Ghani, M. A., Tripathy, D. & DeFronzo, R. A. Contributions of beta-cell dysfunction and insulin resistance to the pathogenesis of impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glucose. Diabetes Care. 29, 1130–1139. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.2951130 (2006).

Adeva-Andany, M. M., Ameneiros-Rodriguez, E., Fernandez-Fernandez, C., Dominguez-Montero, A. & Funcasta-Calderon, R. Insulin resistance is associated with subclinical vascular disease in humans. World J. Diabetes. 10, 63–77. https://doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v10.i2.63 (2019).

DeFronzo, R. A. Pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Med Clin North Am 88, 787–835, ix, (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2004.04.013

Warram, J. H., Martin, B. C., Krolewski, A. S., Soeldner, J. S. & Kahn, C. R. Slow glucose removal rate and hyperinsulinemia precede the development of type II diabetes in the offspring of diabetic parents. Ann. Intern. Med. 113, 909–915. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-909 (1990).

Fuchs, A. et al. Associations among adipose tissue immunology, inflammation, exosomes and insulin sensitivity in people with obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 161, 968–981 e912. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2021.05.008 (2021).

Duan, Y. Y. et al. Multi-tissue transcriptome-wide association study reveals susceptibility genes and drug targets for insulin resistance-relevant phenotypes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 26, 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.15298 (2024).

Papakonstantinou, E., Oikonomou, C., Nychas, G. & Dimitriadis, G. D. Effects of Diet, Lifestyle, chrononutrition and alternative dietary interventions on postprandial glycemia and insulin resistance. Nutrients 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14040823 (2022).

Pan, Z., Gong, T. & Liang, P. Heavy metal exposure and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res 134, 1160–1178. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.123.323617 (2024).

Wang, B. et al. Exposure to lead and cadmium is associated with fasting plasma glucose and type 2 diabetes in Chinese adults. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 38, e3578. https://doi.org/10.1016/10.1002/dmrr.3578 (2022).

Xiao, L. et al. Cadmium exposure, fasting blood glucose changes, and type 2 diabetes mellitus: A longitudinal prospective study in China. Environ. Res. 192, 110259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.110259 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. Effects of multi-metal exposure on the risk of diabetes mellitus among people aged 40–75 years in rural areas in Southwest China. J. Diabetes Investig. 13, 1412–1425. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdi.13797 (2022).

Chen, Y., Huang, H., He, X., Duan, W. & Mo, X. Sex differences in the link between blood cobalt concentrations and insulin resistance in adults without diabetes. Environ Health Prev Med 26, 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12199-021-00966-w (2021).

Chen, Y., Huang, H., He, X., Duan, W. & Mo, X. Sex differences in the link between blood Cobalt concentrations and insulin resistance in adults without diabetes. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 26, 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12199-021-00966-w (2021).

Bobb, J. F., Henn, C., Valeri, B., Coull, B. A. & L. & Statistical software for analyzing the health effects of multiple concurrent exposures via bayesian kernel machine regression. Environ. Health. 17, 67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-018-0413-y (2018).

Agier, L. et al. A systematic comparison of linear Regression-Based statistical methods to assess Exposome-Health associations. Environ. Health Perspect. 124, 1848–1856. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP172 (2016).

He, S. et al. Association of exposure to multiple heavy metals during pregnancy with the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus and insulin secretion phase after glucose stimulation. Environ. Res. 248, 118237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2024.118237(2024).

Wang, X. et al. Urinary metal mixtures and longitudinal changes in glucose homeostasis: the study of women’s health across the Nation (SWAN). Environ. Int. 145, 106109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.106109 (2020).

Ge, X. et al. Sex-specific associations of plasma metals and metal mixtures with glucose metabolism: an occupational population-based study in China. Sci. Total Environ. 760, 143906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143906 (2021).

Li, K. et al. Associations of metals and metal mixtures with glucose homeostasis: A combined bibliometric and epidemiological study. J. Hazard. Mater. 470, 134224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.134224 (2024).

Carrico, C., Gennings, C., Wheeler, D. C. & Factor-Litvak, P. Characterization of weighted quantile sum regression for highly correlated data in a risk analysis setting. J. Agric. Biol. Environ. Stat. 20, 100–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13253-014-0180-3 (2015).

Colicino, E., Pedretti, N. F., Busgang, S. A. & Gennings, C. Per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances and bone mineral density: results from the bayesian weighted quantile sum regression. Environ. Epidemiol. 4, e092. https://doi.org/10.1097/EE9.0000000000000092 (2020).

Wallace, T. M., Levy, J. C. & Matthews, D. R. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care. 27, 1487–1495. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.27.6.1487 (2004).

Matthews, D. R. et al. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28, 412–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00280883 (1985).

Muniyappa, R., Lee, S., Chen, H. & Quon, M. J. Current approaches for assessing insulin sensitivity and resistance in vivo: advantages, limitations, and appropriate usage. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 294, E15–26. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00645.2007 (2008).

Bobb, J. F. et al. Bayesian kernel machine regression for estimating the health effects of multi-pollutant mixtures. Biostatistics 16, 493–508. https://doi.org/10.1093/biostatistics/kxu058 (2015).

Greenland, S., Pearl, J. & Robins, J. M. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology 10, 37–48 (1999).

Moon, S. S. Association of lead, mercury and cadmium with diabetes in the Korean population: the Korea National health and nutrition examination survey (KNHANES) 2009–2010. Diabet. Med. 30, e143–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.12103 (2013).

Hong, H. et al. Cadmium exposure impairs pancreatic beta-cell function and exaggerates diabetes by disrupting lipid metabolism. Environ. Int. 149, 106406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.106406 (2021).

Buha, A. et al. Emerging links between cadmium exposure and insulin resistance: Human, Animal, and cell study data. Toxics 8 https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics8030063 (2020).

Menke, A., Guallar, E. & Cowie, C. C. Metals in urine and diabetes in U.S. Adults. Diabetes 65, 164–171. https://doi.org/10.2337/db15-0316 (2016).

Yuan, Y. et al. Associations of multiple plasma metals with incident type 2 diabetes in Chinese adults: the Dongfeng-Tongji cohort. Environ. Pollut. 237, 917–925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2018.01.046 (2018).

Chen, Y. W. et al. Methylmercury induces pancreatic beta-cell apoptosis and dysfunction. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 19, 1080–1085. https://doi.org/10.1021/tx0600705 (2006).

Chen, K. L. et al. Mercuric compounds induce pancreatic Islets dysfunction and apoptosis in vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 13, 12349–12366. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms131012349 (2012).

Sanders, A. P. et al. Combined exposure to lead, cadmium, mercury, and arsenic and kidney health in adolescents age 12-19 in NHANES 2009-2014. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 131, 104993. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.104993 (2019).

Spoto, B., Pisano, A. & Zoccali, C. Insulin resistance in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 311, F1087–F1108. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00340.2016 (2016).

Abdulla, M. & Chmielnicka, J. New aspects on the distribution and metabolism of essential trace elements after dietary exposure to toxic metals. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 23, 25–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02917176 (1989).

Kowalska, J. B., Mazurek, R., Gasiorek, M. & Zaleski, T. Pollution indices as useful tools for the comprehensive evaluation of the degree of soil contamination-A review. Environ. Geochem. Health 40, 2395–2420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10653-018-0106-z (2018).

Li, K. et al. Associations of metals and metal mixtures with glucose homeostasis: A combined bibliometric and epidemiological study. J. Hazard. Mater. 470, 134224. https://doi.org/j.jhazmat.2024.134224 (2024).

Li, L. & Yang, X. The Essential Element Manganese, Oxidative Stress, and Metabolic Diseases: Links and Interactions. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2018, 7580707. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7580707 (2018).

Rao, K. V. & Norenberg, M. D. Manganese induces the mitochondrial permeability transition in cultured astrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 32333–32338. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M402096200 (2004).

Masenga, S. K., Kabwe, L. S., Chakulya, M. & Kirabo, A. Mechanisms of oxidative stress in metabolic syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24097898 (2023).

Lowell, B. B. & Shulman, G. I. Mitochondrial dysfunction and type 2 diabetes. Science 307, 384–387. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1104343 (2005).

Finley, J. W., Johnson, P. E. & Johnson, L. K. Sex affects manganese absorption and retention by humans from a diet adequate in manganese. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 60, 949–955. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/60.6.949 (1994).

Wang, X. et al. Associations of serum manganese levels with prediabetes and diabetes among >/=60-Year-Old Chinese adults: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional analysis. Nutrients 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8080497 (2016).

Tvermoes, B. E. et al. Effects and blood concentrations of Cobalt after ingestion of 1 mg/d by human volunteers for 90 d. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 99, 632–646. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.113.071449 (2014).

Yang, J., Lu, Y., Bai, Y. & Cheng, Z. Sex-specific and dose-response relationships of urinary Cobalt and molybdenum levels with glucose levels and insulin resistance in U.S. Adults. J. Environ. Sci. (China). 124, 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2021.10.023 (2023).

Cardoso, B. R., Braat, S. & Graham, R. M. Selenium status is associated with insulin resistance markers in adults: findings from the 2013 to 2018 National health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES). Front. Nutr. 8, 696024. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.696024 (2021).

Li, Z. et al. Association between exposure to arsenic, nickel, cadmium, selenium, and zinc and fasting blood glucose levels. Environ. Pollut. 255, 113325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113325 (2019).

Misu, H. et al. A liver-derived secretory protein, Selenoprotein P, causes insulin resistance. Cell. Metab. 12, 483–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2010.09.015 (2010).

Liu, S. et al. Arsenic induces diabetic effects through beta-cell dysfunction and increased gluconeogenesis in mice. Sci. Rep. 4, 6894. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06894 (2014).

Fasae, K. D. & Abolaji, A. O. Interactions and toxicity of non-essential heavy metals (Cd, Pb and Hg): lessons from drosophila melanogaster. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 51, 100900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2022.100900 (2022).

Gade, M., Comfort, N. & Re, D. B. Sex-specific neurotoxic effects of heavy metal pollutants: Epidemiological, experimental evidence and candidate mechanisms. Environ. Res. 201, 111558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.111558 (2021).

Toro-Roman, V. et al. Sex differences in cadmium and lead concentrations in different biological matrices in athletes. Relationship with iron status. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 99, 104107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etap.2023.104107 (2023).

Behr, L. C., Simm, A., Kluttig, A. & Grosskopf Grosskopf, A. 60 years of healthy aging: On definitions, biomarkers, scores and challenges. Ageing Res. Rev. 88, 101934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2023.101934 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, for providing access to the data.

Funding

This research is supported in part by the Guangxi Science and Technology Program (Grant AB20072003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DH contributed to the conception and design of the study. QW, RG and SC analyzed the data. QW wrote the first draft of the manuscript. JC and MQ contributed to data collection from different centers. All authors contributed their skills to revise the manuscript and approved the submitted version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

Our study was based on a publicly available NHANES database. No patients, the public or animals were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of our study. All data were publicly accessible (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes). Therefore, ethical approval was not applicable for our study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Q., Gan, R., Chen, S. et al. Associations of metal mixtures with insulin resistance and glucose homeostasis in U.S. adults from the NHANES 2011–2018. Sci Rep 16, 2047 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31637-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31637-3