Abstract

The recent boom in the spread of false information on social media and web platforms has emerged as a worldwide threat to public opinion, social coherence, and democratic establishments. Traditional fact checking strategies are not sufficient to address the scale and speed of disinformation spreading. So, scalable, automatic, and intelligent fake news detection systems are now in high demand. In this paper, we present a new hybrid model named Graph-Augmented Transformer Ensemble (GETE) for efficient and scalable fake news detection. The primary objective of GETE is to leverage both linguistic and relational features of news spreading by integrating transformer-based language models with graph neural networks (GNNs) with a meta-learned ensemble strategy. The proposed architecture combines the semantic strength of transformer-based models such as BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) and RoBERTa (Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach) with the structure understanding provided by GNNs constructed from user-news interactions and source credibility graphs. The fusion module based on meta-learning is used to train the fusion of these heterogeneous modalities to allow dynamic weighting based on the characteristics of the input data. The combination of deep contextual language understanding and graph-based relational modeling produces synergistic advantages in detection accuracy and generalization. Experimental evaluations on benchmarking datasets FakeNewsNet and LIAR demonstrate GETE’s better performance than existing state-of-the-art methods. Specifically, GETE achieves 96.5% accuracy, 96.5% F1-score, and ROC-AUC of 97.3%, boosting F1-score by 4.2% and AUC by 5.6% over high-performing baseline methods. Additionally, proposed model demonstrates enhanced scalability, explainable predictions, and robustness across diversified domains and source distributions. The integration of the meta-ensemble module facilitates adaptive decision-making, hence enabling enhanced detection performance in real-world noisy situations. “With its high performance, explainability, and scalability, the GETE framework presents a solid foundation for the next generation of reliable and adaptive fake news detection systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The age of the internet has revolutionized information creation, dissemination, and consumption, offering both great opportunities and significant challenges1. Social media platforms and online news sources have democratized information flow to the extent that anyone can publish2. However, this openness has also facilitated the rapid spread of fake news, a term used for information that is fabricated or false and deliberately shared with the intent to mislead3. Fake news has had serious consequences, ranging from influencing political elections to aggravating public health emergencies, such as the COVID-19 crisis4,5. Although COVID-19 datasets (e.g., CoAID, FakeCovid) have been introduced and studied in prior research, in this work we focus our experiments exclusively on the LIAR and FakeNewsNet datasets. Misinformation, especially fake news, can manipulate public opinion, trigger societal conflict, and erode trust in institutions6,7.

In this work, we define fake news more precisely to avoid ambiguity. Specifically, we focus on two primary categories of misinformation: (i) completely fabricated content created with no factual basis, and (ii) misleading or partially manipulated information that distorts, exaggerates, or selectively presents facts to influence public perception. These categories reflect the real-world patterns of misinformation observed in both the LIAR and FakeNewsNet datasets. By clearly defining the scope of fake news, our model is designed to capture both linguistic deception and relational spreading behaviors in social networks. The amount and speed with which false news spreads make it difficult for traditional fact-checking processes to keep pace. Human fact-checking can only verify a limited number of articles at a time and is typically outrun by the viral spread of untruths8,9. Automated processes that can detect fake news at scale have therefore become a necessity, although devising such solutions remains a challenging task10,11. Fake news stories do not typically have apparent, recognizable signs of inaccuracy. The problem is not just with the content of the article but also with how the article is disseminated through networks, depending on user interaction and the perceived credibility of sources12,13. It is therefore important that any automatically generated system for detecting fake news takes into account both the content of the news story and the relational context in which it is disseminated14,15. Decades of research have witnessed a number of machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL)16,17,18 techniques that have been applied in various ways to solve social issue of identifying fake news. Traditional models such as SVM and Logistic Regression used content features from text to find dishonest pattern within written content19,20. However, these models depend heavily on manually engineered linguistic features and fail to model the social dynamics through which fake news spreads, limiting their generalization across platforms. The models showed excellent performance at first but they failed to achieve consistent results across different datasets and struggled with the social dynamics that drive fake news distribution21,22. The transformer models BERT and RoBERTa23 have significantly improved contextual text understanding through self-attention mechanisms.Yet, these models analyze each article in isolation and lack awareness of user interactions or source credibility, making them less effective for capturing relational cues in misinformation propagation. The attention-based models achieve top results in all natural language processing tasks including fake news detection because they extract deep semantic features from text while handling contextual information24,25. The transformer models evaluate articles independently without understanding how social network dynamics because they lack awareness of how information spreads through social networks based on user behavior and source trust and social connections26,27. The solution to this problem could be found through the study of graph neural networks (GNNs). Graph Neural Networks (GNNs)8,15 model users, articles, and sources as graph nodes to study information diffusion. They effectively capture relational structures but overlook detailed semantic nuances in text, which limits their standalone accuracy. Therefore, combining transformer-based semantic models with graph-based relational models4,28 offers a holistic solution—leveraging transformers for deep textual semantics and GNNs for diffusion dynamics—to overcome the weaknesses of each individual approach.The combination of transformer-based networks with GNNs presents a more holistic solution towards detecting fake news by integrating relational dynamics with semantic understanding29,30. Building on this insight, we introduce a novel framework that integrates the deep semantic capabilities of transformer models with the relational representation learning of GNNs. The integrated technique leverages a meta-learned ensemble approach to learn adaptively how information from each of the models is combined such that optimal features of each modality are weighted appropriately1,31. It is made precise and scalable to the dynamic and complex nature of fake news dissemination3,32. Figure 1 illustrates the different types of false information categories commonly encountered in fake news scenarios.

Despite these advances, fake news detection continues to face several technical bottlenecks that limit the effectiveness of existing approaches. A key challenge is data sparsity, where user–article interactions are often incomplete, noisy, or unavailable, reducing the ability of models to fully capture dissemination patterns2,13. Another issue is cross-domain generalization, since models trained on one platform (e.g., Twitter) or event (e.g., elections) often fail to perform reliably on another (e.g., health misinformation), revealing poor adaptability10,29. Furthermore, the dynamic and large-scale nature of social media networks presents scalability and noise-handling challenges for both graph-based and text-based methods5,6. These limitations underscore the need for hybrid approaches that can integrate semantic understanding with relational modeling while remaining adaptable to diverse domains and evolving misinformation strategies. Unlike existing hybrid approaches such as GETAE31 and related methods21,33, which primarily rely on fixed or validation-tuned ensemble weights, our framework introduces a meta-learned ensemble mechanism where the weight parameter α is directly optimized via backpropagation during training. This enables GETE to dynamically adapt the balance between semantic features (from Transformers) and relational features (from GNNs) depending on dataset characteristics, thereby enhancing robustness and generalization across domains. The rapid expansion of fake news on the internet has also emerged as one of the most urgent issues of contemporary society4,5. The spread of false information has the potential to have a significant impact on public opinion, destroy reputations, destabilize political regimes, and undermine trust in institutions and media6,7. While fake news spreads around the globe quicker than ever, often spurred by social media algorithms, fake news prevention and detection have emerged as a pressing issue11,20. The ability to automatically detect fake news at scale has thus emerged as a necessity for the safeguarding of public debate and trust in information1,8. Current methods2,6,21,33 of identifying false news are primarily content-based and involve analysing the content of news stories in text form for the presence of some attributes like sensationalism, emotional appeals, or unsubstantiated assertions.

The researchers have investigated alternative methods in addition to these approaches. The paper Veracity-Oriented Context-Aware LLM Prompting Optimization34 demonstrates the effectiveness of using large language models with context-aware prompting methods to improve fake news veracity judgment in few-shot detection tasks. The Courtroom-FND system35 implements a debate framework which allows three roles (prosecution, defense and judge) to conduct courtroom-style argumentation to improve fake news detection interpretability and robustness. The methods provide useful insights but they mainly concentrate on either prompting techniques or adversarial debate approaches. The GETE framework proposed by us combines semantic modeling through Transformers with relational modeling through GNNs by using a meta-learned ensemble approach to achieve domain adaptation.

Earlier approaches, such as traditional ML methods like SVMs and Naive Bayes, primarily relied on content-based features3,19. However, these methods were often overly simplistic in their assumptions and lacked the ability to generalize effectively across datasets or handle the nuanced and evolving nature of modern misinformation9,15. As the tactics and formats of fake news continue to evolve, there is a growing need for more advanced, adaptive detection techniques22,24. Recent developments in deep learning, especially with the creation of transformer models such as BERT and RoBERTa, have greatly enhanced the capacity to understand the context and meaning of text2,23. The models use attention mechanisms to enable them to capture subtle patterns within text, which has resulted in great performance improvement10,25. Nonetheless, the models commonly aim to analyse text in isolation, without an understanding of the larger context within which information flows12,31. This is a limitation that is important since the dissemination of fake news is not just a matter of the content but also of the way it is spread through social networks13,14,26,29. GNNs is another complementary method by encoding the interactions and relations of entities like users, articles, and sources8,27. GNNs are capable of encoding the dynamics of information diffusion over networks and have a special advantage in encoding the diffusion of misinformation4,28. GNNs also have their own disadvantages. Although they excel in relational modeling, they cannot understand the content of the articles in depth15,30. State-of-the-art hybrid models attempted to integrate transformers with GNNs but are based on static ensemble methods that are unable to cope with the dynamic nature of disinformation1,9. These models are unable to dynamically learn the weight to be given to each modality, text content and relational signals, depending on the specific feature of the fake news to be detected6,8,12,31. Furthermore, the majority of existing systems are unable to incorporate multimodal features, i.e., user behaviour, temporal propagation patterns, and source credibility20,26. In order to overcome these limitations, we introduce a dynamic fusion model using meta-learning to learn how to adapt the fusion of information within each modality to enhance the adaptability and robustness of the model towards detecting fake news across various scenarios22,29. Existing hybrid architectures such as GETAE31 merge transformer-based semantic embeddings with graph-based relational embeddings using static weighting strategies. In contrast, our proposed GETE framework introduces a meta-learned ensemble mechanism, where the ensemble weight α is learned during training via backpropagation. This dynamic adaptation enables GETE to responsively balance semantic and relational cues depending on dataset-specific features, enhancing generalization and robustness compared to fixed-weight fusion methods.

Research Questions. This study is guided by the following research questions:

RQ1

How can transformer-based semantic modeling and GNN-based relational modeling be effectively combined to improve fake news detection?

RQ2

Can a meta-learned ensemble mechanism dynamically balance semantic and relational features better than static fusion strategies (e.g., in GETAE31?

RQ3

How robust and generalizable is the proposed GETE framework across multiple benchmark datasets (FakeNewsNet, LIAR) compared to existing methods?

Novel scientific contributions

The hybrid fake news detection framework presented in this paper provides an effective and scalable solution to the emerging problem of misinformation, especially in high-speed, high-volume scenarios. The key contribution is listed as follows:

-

a.

We introduce a new hybrid architecture integrating transformer-based models (i.e., BERT2, RoBERTa8 with GNNs23 to represent deeply context-rich semantics along with relational dependencies among news entities simultaneously. This joint modeling mechanism strengthens fake news detection by effectively using textual content as well as social-contextual relations.

-

b.

We integrate a meta-learned ensemble technique1,12 that dynamically weights and aggregates outputs from transformer and GNN models, enabling adaptive and resilient fake news detection across varying input patterns and tasks.

-

c.

The proposed framework is meticulously tested over large-scale benchmarking corpora, LIAR3 and FakeNewsNet4. The results show that proposed approach surpasses state-of-the-art methods, yielding 96.5% accuracy, 96.5% F1-score, and 97.3% ROC-AUC25. The findings indicate that our framework possesses interpretability and transparency in the decision-making process as well as robustness, accuracy, and scalability in real-scenario applications.

As opposed to several black-box-style structures, our framework provides transparency in decision-making. Explainable design makes users able to track the model’s predictions back to specific trust indicators and feature contributions, hence enhancing user trust and confidence in the system’s output11,32. The design is lightweight and scalable, supporting real-time usability in high-throughput systems. Its low-latency architecture makes it possible to process huge amounts of data with little latency and computation, supporting viable deployment in systems with the need to rapidly detect misinformation and react20,26.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Sect. Related work reviews related work on fake news detection, highlighting gaps in transformer- and GNN-based methods. Section Proposed framework describes the proposed GETE framework, including the transformer modeling, GNN modeling, and the meta-learned ensemble mechanism. Section Results and discussion presents the experimental setup, baseline comparisons, and results with detailed discussions. Section Conclusion and future work concludes the paper and outlines future research directions. To address these gaps in prior studies, we propose the Graph-Augmented Transformer Ensemble (GETE), which dynamically learns to balance semantic and relational information through a meta-learned ensemble mechanism. By clearly distinguishing fabricated content from misleading content, our framework is able to leverage both semantic cues and relational propagation dynamics, which are essential for addressing these two core forms of misinformation.

Related work

The study of fake news detection emerged as a new field because web media misinformation has grown more prevalent4,5. The detection of fake news has become more sophisticated through the development of ML, DL and hybrid models which appeared in21 and33. The identification of fake news during its initial stages depended on traditional Machine Learning (ML) methods which included Naive Bayes, SVM and Logistic Regression3,19. Although effective on small datasets, these models rely on shallow lexical cues and do not capture network-level dependencies. The researchers employed hand-designed features through n-grams and Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) and bag-of-words (BoW) to determine the authenticity of articles. DL became the essential solution because ML methods failed to deliver so models needed to learn text representations independently without human involvement for feature engineering23. The first method for fake news detection used Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs)24. The study showed that CNNs achieved success in finding local patterns in text information but RNNs with LSTM networks outperformed them in processing sequential word connections and contextual information7,25. While CNNs detect local textual patterns and RNNs model sequences, both fail to learn global dependencies and contextual semantics. The CSI (Content-User-Interaction) model used LSTMs to combine user interaction data with textual content for fake news detection5. DL models showed superior performance than other models but researchers could not find solutions to overcome their existing limitations. RNNs often suffered from vanishing gradients when modeling long dependencies26, while CNNs lacked the ability to capture the global context of an article9. The introduction of transformer architectures including BERT and RoBERTa solved these problems through self-attention mechanisms which brought a revolution to NLP2,23. Despite their success, transformers treat articles as independent units, overlooking propagation and user-source relations critical for fake news dynamics. Transformers process distant word relationships through their ability to detect contextual word dependencies and their bidirectional encoding system which enables deeper semantic understanding1,6. The pretraining process on extensive datasets allows models to learn general knowledge which they can apply to fake news detection tasks10. However, while transformers excel at semantic modeling, they are less effective at capturing the relational nature of misinformation, which often propagates through social networks11,31. To fill this gap, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have been applied to fake news detection8,30. GNNs process graph-structured data and model relationships among entities such as users, articles, and sources27,29. By treating users, articles, and sources as nodes and their interactions as edges, GNNs can capture diffusion dynamics in social networks4. Variants such as Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) and Graph Attention Networks (GATs) aggregate neighbourhood information or focus attention on influential nodes, respectively15,28,32. GNNs are powerful for modeling relational cues and propagation but lack the deep linguistic understanding that transformer models provide20,30. Recognizing these complementary strengths, hybrid models emerged to combine transformer-based semantics with GNN-based relational reasoning12,13,21,24. One approach involves using transformers to encode news text while GNNs model relations between sources, articles, and users25,26. For example, Khattar et al. fused BERT features with graph properties via attention mechanisms, showing improvements in detection accuracy36. Truică et al.31 proposed GETAE as a hybrid ensemble model which combines transformer and graph features in their research. Unlike these static-weight fusion methods, our GETE framework employs a meta-learned adaptive weighting mechanism to dynamically balance semantic and relational cues. While related in spirit, GETAE differs from our work, as our proposed GETE framework employs a meta-learned adaptive weighting strategy to dynamically balance semantic and relational signals during training. Research now investigates meta-learning as a technique to enhance adaptability that allows models to adapt to new datasets and tasks through the optimization of their learning processes6,22. The detection of fake news benefits from meta-learning because it enables ensembles to modify their component model weights based on domain information and source and social context data9,28,33. The system reaches improved operational performance and enhanced reliability because it learns to handle different operational settings29. The proposed GETE framework combines transformer-based semantic encoders with GNN-based relational modeling through a meta-learned ensemble mechanism to create an adaptive system that handles different datasets and changing misinformation tactics20. Praseed et al. [The research provides a detailed evaluation of GNN-based disinformation detection which includes essential methods and necessary datasets and structural modeling obstacles. The surveys contain vital information about graph-based methods yet these concepts remain theoretical because they lack operational frameworks for practical implementation. Building on these observations, our proposed model (GETE) integrates transformer-based language modeling6,23, graph-based relational reasoning8,14, and a meta-learned ensemble paradigm1,12, to provide a unified framework for fake news detection. The adaptive weighting mechanism in GETE represents an advancement over previous static and hybrid fusion models21,23,30,31 because it enables better performance across multiple datasets. Research studies from recent times have investigated multimodal extensions as part of their analysis. The authors Wang et al. present their research findings through an illustrative example in their paper. 6] A multimodal transformer system was developed by 6] to combine text information with visual data for better fake news detection results. The researchers showed that uniting image signals with language produced positive results but their approach failed to handle extensive relationships between news entities and users and their propagation routes. Our GETE framework integrates semantic encoders with graph-based modeling8,14 to leverage both structural features and text semantic information. GETE uses a unique ensemble mechanism which learns to combine outputs from different sub-models through adaptive fusion whereas previous multimodal approaches relied on fixed fusion methods24. Other directions in the literature include the use of large language models (LLMs). Table 1 provides the comparative analysis of selected fake news detection models based on key features and accuracy.

Papageorgiou et al.33, for instance, investigated LLMs and deep neural networks for counterfeit news detection, highlighting the strength of transfer learning for semantic representation. While their approach focused primarily on text-based modeling, our framework extends this line of work by pairing semantic encoders with graph-based cues8,13, allowing joint exploitation of content and relational information. Beyond hybrid architectures, researchers have begun exploring innovative paradigms. Courtroom-FND simulates adversarial debate between roles (prosecution, defense, judge) to improve interpretability and veracity judgment35. Other work has investigated few-shot detection through adversarial and contrastive self-supervised learning37. The field has seen the development of new methods which include context-aware LLM prompting for veracity inference34 and multi-task prompting for consistency reasoning38. The methods require systematic thinking and flexible approaches which work together with ensemble-based frameworks such as GETE. Various studies on online information analysis research different aspects of this subject domain. These include figurative language detection in social media39, satire detection40, sarcasm detection41, hate speech42, and financial misinformation43,44. The research demonstrates particular problems in specific domains yet our system provides a universal framework which unites semantic and relational data for misinformation identification. Fake news detection has also progressed through multiple technical paradigms. Early approaches employed machine learning classifiers with handcrafted features19,20, later enhanced by word embeddings such as Word2Vec and GloVe45. With the success of deep learning, transformer architectures such as BERT and RoBERTa achieved state-of-the-art performance on benchmark datasets23,24,25,46. Sentence transformers47 and document embeddings48 further enriched representation learning for text-based misinformation detection.More recent works emphasize ensemble and mixture-of-expert (MoE) models, where specialized expert networks capture different aspects of the data and gating mechanisms dynamically combine their outputs49. Network-aware ensemble frameworks that incorporate propagation features have also been proposed50,51, showing that modeling how news spreads in social networks can enhance classification performance. Beyond detection, mitigation strategies have gained attention. Proactive immunization52, tree-based blocking53, and community-focused methods54 seek to reduce misinformation spread by targeting influential nodes or dense clusters. Real-time detection frameworks55,56 address the need for streaming analysis, combining scalable pipelines with fast inference. Additionally, virality prediction models57 aim to anticipate which content is likely to spread widely, enabling early interventions. Together, these diverse strands of work underline the growing sophistication of fake news detection research. Our contribution, GETE, is positioned within this landscape as a framework that adaptively integrates semantic and relational learning through a meta-learned ensemble mechanism, complementing prior approaches and addressing challenges of adaptability and robustness across domains.

Problem formulation

Fake news refers to either fully fabricated narratives or partially manipulated statements designed to mislead, both of which require combined semantic and relational modeling to detect effectively. In the text content area, fictional news reports have subtle linguistic characteristics that make them different from real news reports. They may include sensationalized tone, emotional tone, or manipulative tone24,32. It is difficult to identify these characteristics as fake news stories may appear as real news from superficial appearance33. This is also compounded by the fact that the meaning of words and phrases is highly context-dependent. To mitigate this, transformer models like BERT6 and RoBERTa33 have fared well as they are able to learn the fine-grained dependencies as well as contextual word relations. These models lack the capacity to process individual articles in isolation of the rest, constraining their capacity to learn the global context of article dissemination within social networks as well as the source credibility26. Alternatively, GNNs provide another choice in that they represent the dissemination of news in a social network by users, articles, and sources as nodes and the interaction between them as edges8,27. GNNs are better suited to represent how the information is disseminated in the network according to what the users do and the authenticity of the sources29. They are lacking in representing the fine-grained linguistic semantics to figure out if the news content itself is deceptive15,30. One of the greatest challenges in identifying fake news, then, is how to effectively combine textual and relational features12. The conventional approaches that summarize only the latter may not necessarily be able to make their best use of their interactions11. An ensemble model that can leverage transformer-based models and GNNs1,9. The model is intended to be able to learn adaptively the relative ranking of textual and relational features based on the particular context of the news article and network it belongs to13. The solution of meta-learning provides flexible adaptation capabilities for handling environments that undergo changes. The model will learn to process different types of data and new fake news distribution patterns through its ability to combine text and relational signals20,22,28. Reducing the problem to learning to create a classifier with maximum accuracy by fusing the features of the two modalities in the appropriate manner, learning to update the transformer and GNN model weights according to the task, makes the detection system not only accurate but also robust and adaptive to changing misinformation tactics7.

Current status and limitations of existing methods

Existing approaches to fake news detection can be broadly categorized into three groups: (i) traditional machine learning models (e.g., SVM, Logistic Regression) that rely on handcrafted linguistic and statistical features19,20, (ii) transformer-based models such as BERT and RoBERTa that excel at semantic comprehension but process articles in isolation23,24,25, and (iii) graph-based models (e.g., GCN, GAT) that model propagation structures and social interactions but often underutilize textual semantics4,8,15. While these methods have advanced the field, they face notable limitations, including poor cross-domain generalization, vulnerability to data sparsity, and lack of adaptability across different misinformation contexts21,28,33. The proposed GETE framework addresses these limitations by introducing a meta-learned ensemble strategy that dynamically integrates semantic representations from transformers with relational dependencies captured by GNNs. Unlike prior static ensembles, GETE adaptively adjusts its reliance on each modality based on validation feedback, thereby improving robustness, scalability, and cross-domain applicability.

Proposed framework

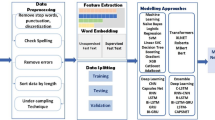

This section presented our hybrid fake news detecting system that combines transformer technology for semantic analysis with graph learning, connected by an adaptive process. This adaptive learning process is referred to as a meta-learned ensemble and has been explored in1 and31. This suggested method is designed to exploit the best features of each approach. Specifically, it combines two distinct techniques, deep semantic analysis provided by transformer models and relational reasoning enabled by graph neural networks (GNNs). The overall framework architecture consists of three core components: a transformer, a GNN, and an additional GNN module. We begin by employing a transformer (BERT or RoBERTa) model. They are responsible for extracting semantic features from the articles’ textual content6,23. The transformer models are especially good at learning how elements of a text interrelate with each other, and aiding the revelation of meaning behind each word, each sentence, each paragraph10. This capability is especially useful for detecting the nuanced wording and deception often used by misinformation32. To complement this, we also employ a GNN which captures the relationship between the users, the articles and the sources, following the precedent set by prior research8,14. In the modern online era, how fake news propagates frequently relies upon user actions and the character of the sources which are propagated4,27. Organizing this data as a graph, with the users and articles as the nodes, and the interactions between them as the edges, the GNN may learn trends in the spread of information and the level of user interaction with it15. This matters since false news often propagates as a coherent unit over a set of networks, and this sort of dynamic understanding holds the key to successful detection28,30. But whereas GNNs excel at modeling relations, they don’t completely encode the deeper meaning of language, this is rectified by transformer models, which come into play and cover the gap29. The system also makes use of the meta-learned ensemble module as the third constituent. The module self-adjusts the weight of each model’s output, depending on how the models perform on the validation set9,31. Instead of just blending the models with fixed weight, as is standard for traditional ensembles, the meta-learned ensemble makes use of a unique technique for picking the optimum mix of the models3. Owing to the dynamic weight, the system can cope better with data change and also get tougher22. For instance, when textual features significantly suggest fake news, the ensemble places more emphasis on the transformer model; when relational cues from user interaction prove more informative, the GNN constituent gets the focus11. This adaptability makes the ensemble generalize into different elements of fake news in other applications20. The combination of the three elements, transformer-based textual analysis, graph-based relational learning, and weighting of the ensemble aided by metalinguistic knowledge forms a successful and transferrable framework used for determining fabricated material1,12. Through the use of the content as well as the context, the approach may distinguish deception from non-deception material with increased efficiency compared with methods directed at each specific class of signals singly21,24. Further, the meta-learning aspect of our ensemble allows for the possibility of continued fine-tuning and improvement, and the system may thus appear as a part of real global applications wherein false trends of news continuously change and evolve7,25. The architecture starts with preprocessing where text as well as features based on graphs are extracted from the input data33. Figure 2 depicts the overall architecture of the Graph-Augmented Transformer Ensemble (GETE) framework. The textual data is pre-processed using a standard pipeline23. The preprocessing steps include lowercasing, removal of punctuation and special characters, elimination of stopwords, tokenization, and lemmatization. Additionally, URLs, mentions, and hashtags are normalized to maintain consistency. This preprocessing ensures that the textual input is clean, semantically meaningful, and ready for feature extraction using word, sentence, or document embeddings.

Transformer-Based text embedding

The suggested framework combines the semantic strengths of transformer models with the relational insights of GNN, all integrated through an adaptive, meta-learned ensemble. It consists of three core components: A transformer model (BERT or RoBERTa) that extracts contextual features from the text2,23. A Graph Neural Network (GCN or GAT) that models the structural relationships within user-article-source interaction graphs. A meta-learned ensemble layer that dynamically adjusts the weighting of each model’s output to optimize overall performance through validation-based learning. Transformers use self-attention to learn long-range word dependencies6. For a tokenized input sequence x = {x1,x2,.,xn}, each token is transformed into a contextual embedding: hi = Transformer(xi) for i∈[1,n]23.

Graph neural network module

The GNN module we propose helps the model understand how users, news articles and sources are related to each other. By being shared, liked, commented on and linked to by users, this type of news can spread very quickly. Just looking at the text is not enough, as these interactions involve the connections between many actors. In our framework, the heterogeneous graph is formally defined as G = (V, E), where nodes V represent entities {users, news articles, sources}, and edges E capture different types of relationships. Specifically, user nodes encode behavioral features such as posting or sharing histories, article nodes contain semantic embeddings extracted from the Transformer model, and source nodes encode metadata such as domain credibility scores4,8. Edges are created by (i) user–article interactions (e.g., sharing, liking, commenting), (ii) user–source subscriptions or follows, and (iii) article–source references (e.g., citations or publishing links)2,28. To assign meaningful weights to user–article interaction edges, we combined engagement indicators using a weighted scoring scheme. Specifically, the edge weight was computed as: 0.60 × normalized shares + 0.30 × normalized comments + 0.10 × normalized likes. Shares were given the highest importance because they typically indicate stronger endorsement and contribute more directly to misinformation spread. All engagement features were min–max normalized to the range [0,1] before combining them, and the final weight was again scaled to [0,1] to maintain uniformity across interaction types. Relationship extraction is automated from the raw dataset logs. User activity fields (shares, likes, comments) define user–article links, while metadata tables define article–source mappings. Source credibility scores are derived from third-party credibility databases or annotated subsets, ensuring that the graph captures both behavioural and credibility-based relationships21,26. Processing such graphs at social media scale introduces challenges such as high sparsity, skewed degree distributions, and memory bottlenecks. To mitigate these, we employ mini-batch training with neighbour sampling (GraphSAGE-style) and sparse adjacency storage14,15. Additionally, edge-type normalization ensures fair contribution across heterogeneous relations, while GPU-based batching enables scalability across millions of nodes6,7.

They are particularly advantageous at learning how different entities are connected which is shown graphically with nodes for each item and edges for the relationships (e.g., users sharing an article, following a user or citing a source)4,29. Our model views the fake news detection problem as a heterogeneous graph, with data nodes represented by V and data edges represented by E. Users, articles and sources are some of the most common entities in the graph of Facebook. The edges stand for anything users or articles do, for example, commenting on an article, sharing a source, following a source platform or linking an article to a different source28. Every node v∈V contains a feature vector xv that collects the characteristics and properties of its related entity. A typical user node could hold their recent activity details, but an article node might contain information in the textual format provided by the transformer model11. Due to the aggregation process, the GNN propagates updates from neighbouring nodes to refine node properties. The model retains both node features as well as the inherent interactions between the nodes, which matters for detecting the diffusion of misinformation through networks25. In the workflow described by us, this aggregation uses either Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) or Graph Attention Networks (GATs). GCNs effectively learn structural features of local neighbourhoods1. In some scenarios, though, GATs employ an attention model which pays more importance to particular connections, like those between influential users, compared to others32. Updated node embeddings provide a useful summary of entities in the graph, showing what a node is and how it interacts with others. Nodes that often share information from a reputable source are more likely to be trusted and considered important in the network, as discovered in this study7,20. An article that many reliable sources have shared and referred to may be judged more trustworthy by parliamentary libraries13. Seeing things with graphs is very useful for learning the ways in which misinformation is shared. A lot of the time, fake news is spread further by some users, sources or groups and this spread is caught by the GNN model using amplification patterns27. Articles that have been shared by people with a record of misleading information or by sources with a poor track record may be designated as fake news. Using input from different areas of a network, GNNs have been shown to excel at finding such propagation patterns, something transformers might have a difficult time spotting31. The GNN module functions together with the transformer-based text embedding module in parallel. While the transformer pays attention to the meaning of the articles, the GNN studies how the network’s components are related12,21. Semantic analysis and relational modeling are merged in the ensemble module, with the former adding extra weight to the approach that performs best1,9. As a result, the GNN module improves the framework’s identification of fake news by studying the relationships between users, articles and sources2,26. The DeepMoji model can generate new insights by using relationships among data which, once integrated with the deep text learning from transformers, makes the fake news detection system work more accurately and steadily22. Equation (1) expresses the core message-passing mechanism of a GNN layer. Its primary purpose is to define how a node in the graph updates its representation (feature vector) based on information from its neighbours.

Where \(\:{h}_{v}^{\left(l+1\right)}\)denotes the feature vector of node v at layer l + 1, while \(\:{h}_{u}^{\left(l\right)}\) represents the feature vector of a neighbouring node u at layer l. The set N(v) includes all neighbours of node v in the graph. The weight \(\:{W}^{\left(l\right)}\) is a learnable parameter that transforms the features from the current layer. The term cvu is a normalization constant, often computed based on the degrees of the nodes v and u, which ensures that feature aggregation remains stable and unbiased across nodes with varying degrees. The non-linear activation function σ(⋅), often ReLU, introduces non-linearity to the model. The encoding allows the GNN to iteratively aggregate and transform neighbour node information, thus preserving local structure as well as context of features.

In our framework, the heterogeneous user–news–source graph is constructed with three distinct types of edges that capture various interaction dynamics within the social media ecosystem. The User–Article edges are established when a user interacts with an article, such as by sharing, liking, or commenting on it, reflecting direct behavioral engagement. The User–Source edges represent a user’s subscription or follow relationship with a particular news outlet, capturing long-term trust or interest patterns. Finally, the Article–Source edges connect news articles to their respective publishing domains or cited sources, thereby encoding the credibility and provenance of the information.

Each edge is assigned a weight that reflects the strength and importance of the relationship. For User–Article links, weights are computed based on the frequency and intensity of interactions, while for User–Source and Article–Source links, the weights are derived from source credibility scores obtained from annotated or external databases. These raw weights are further normalized into the range [0,1] to ensure a balanced influence among heterogeneous edge types and to prevent any single relation from dominating the learning process.To mitigate the impact of graph sparsity—a common issue arising from incomplete or uneven user engagement—we employ mini-batch neighbor sampling inspired by the GraphSAGE framework, along with sparse adjacency matrix storage for computational efficiency. Moreover, edge-type normalization is applied to balance the contribution of dense and sparse relations, preventing the model from overemphasizing frequently occurring node types. This heterogeneous graph structure enables the GNN to effectively learn relational dependencies among users, articles, and sources while maintaining balanced representation even under sparse social interactions.

Meta-Learned ensemble module

Rather than relying on fixed weights or simple averaging of the outputs from the Transformer and GNN models, our approach employs a meta-learning strategy22 to dynamically learn the optimal combination of these outputs for improved robustness and adaptability. Let the result1,12 from the Transformer model be defined as pT = Softmax(Linear(Tx)) and from the GNN be defined as pG = Softmax(Linear (Gx)). For the result of the final prediction, we use y^=α⋅pT+(1 − α)⋅pG, where α is a learnable parameter in range [0, 1]. This is optimised with validation to enable the ensemble to adaptively vary its dependency on each model’s result in order to enhance robustness and flexibility20. These probability distributions are combined to form the final prediction is made, but not statically or rigidly. Rather, a meta-learned weight α determines how much weight each of the forecast should have31. The overall prediction is generated with a combination of the outputs of the Transformer and GNN models, denoted as pT and pG respectively. The weight α for this combination is learned using meta-learning. This weight reflects the relative confidence of the Transformer and GNN models in their predictions9,11. A validation set is used to optimize α, with the goal of minimizing the loss function and thereby improving the ensemble’s performance3. The output of the Transformer model is defined as T(x), a transformed feature vector extracted from the input text, with the predicted class probabilities represented by pT. Similarly, the output of the GNN model is represented asG(x), a feature vector capturing the relationships among various nodes (e.g., users, articles, and sources) in the social graph4,8. Equation (2) illustrates how the meta-learned ensemble combines these outputs:

In the proposed GETE framework, the ensemble weight α is implemented as a learnable model parameter and is optimized end-to-end along with the Transformer and GNN components. Rather than relying on a separate external validation loop, α is updated directly through backpropagation during training. It is initialized within the interval [0,1] and its gradients are computed from the same cross-entropy loss used for optimizing the remaining model parameters. This mechanism enables α to dynamically adjust the relative contribution of semantic features (from the Transformer) and relational features (from the GNN), based on their effectiveness during training. To ensure generalization and avoid overfitting, we monitor α using validation performance through early-stopping and learning-rate scheduling. This provides a stable and reproducible optimization process.

Unlike prior hybrid architectures such as GETAE21,33, which employ fixed or heuristically tuned ensemble weights, the proposed GETE framework introduces a dynamically learned ensemble mechanism. The ensemble weight α functions as a trainable parameter which backpropagation optimizes end-to-end to determine the optimal balance between Transformer-based semantic features and GNN-based relational features during training. The dynamic weighting strategy produces better results for robustness and generalization across different domains. GETE achieves both real-world scalability and avoids static fusion limitations through its end-to-end training approach which uses validation feedback11,28,31. The ensemble weight α is optimized jointly with the Transformer and GNN parameters during end-to-end training. Specifically, the final prediction y^=α⋅pT+(1 − α)⋅pG is compared against the ground-truth labels using the standard cross-entropy loss. Gradients with respect to α are computed via backpropagation, ensuring that α dynamically adjusts to balance semantic (Transformer) and relational (GNN) contributions. Unlike meta-learning frameworks such as MAML or Reptile, which require inner/outer optimization loops across multiple tasks, our approach directly treats α as a trainable parameter within the classification objective. Conceptually, this resembles a stacked ensemble or mixture-of-experts gating mechanism1,6,22, where α functions as an adaptive weight that minimizes classification error.

Here, y^ shows the equation’s prediction which comes from adding transformed versions of both the transformer’s output probability distribution and the GNN’s output probability distribution. Each model receives a dynamic weight of α ∈ [0,1] which is trained to influence the contribution from the ensemble22. In this case, α is a tweakable parameter between 0 and 1, obtained as a result of validation optimization. To be exact, pT is the distribution made by the transformer model, pG is the distribution generated by the GNN and α controls how strongly the models’ results are blended. Equation (3) outlines how the objective for optimization works when finding the right weight α on validation data:

In Eq. (3), L(⋅) denotes the loss function, typically cross-entropy, which measures the discrepancy between the combined prediction α⋅pT+(1 − α)⋅pG and the true labels yval from the validation set. The optimization seeks the value of α\alphaα that minimizes this loss, thereby learning the most effective way to weigh the transformer and GNN predictions for improved generalization and accuracy. Equation (4) expresses the final prediction after the ensemble weight α has been optimized:

For reproducibility, we emphasize that α is trained as part of the network parameters during end-to-end learning, and no nested meta-optimization loop is required. The optimization follows standard gradient descent, ensuring a transparent and easily implementable training process. It is important to note that while hybrid Transformer–GNN frameworks such as GETAE31 have been previously proposed, they typically employ static or validation-based weighting strategies. In contrast, GETE treats the ensemble weight α as a trainable parameter, optimized end-to-end with the classification objective. This dynamic optimization allows α to adapt continuously during training, making GETE more flexible and resilient than earlier approaches21,33. Unlike fixed fusion strategies used by GETAE31, which apply static or pre-defined weights to combine transformer and graph embeddings, GETE treats the ensemble weight α as a trainable parameter that is optimized jointly with all model components via backpropagation. The model achieves performance stability across different datasets and adapts to changing fake news patterns through its dynamic weighting system which adjusts the influence between semantic and relational modules. Here, ypred is the ensemble’s result that is used to make predictions. It reuses the optimized weight α∗ previously obtained from Eq. (3). It is both the relational dependencies learned by the GNN and the semantic features learned by the transformer, leading to powerful and robust prediction. The meta-learned ensemble module offers several key advantages. The model achieves optimal performance by dynamically adjusting the weight of each sub-model prediction to match different datasets and scenarios which results in improved robustness and accuracy6,26. The model achieves effective generalization across different types of misinformation because it can modify its use of transformer-based or graph-based methods according to validation feedback21,25. By leveraging the complementary strengths of transformers and GNNs, the ensemble model achieves higher predictive performance than models based on a single modality2,29. The model adjusts to fake news evolution by determining the best weight distribution for each ensemble component. The method combines the advantages of both architectures through their unique capabilities which address the limitations of each other. The learned ensemble weights enable the model to handle different and new challenges in fake news detection according to13 and15.

The end-to-end pipeline of Algorithm 1 uses natural language processing and graph learning and ensemble modeling to detect fake news according to best practices. The first step involves collecting raw news feeds which need preprocessing to standardize text content and divide them into separate tokens while removing unnecessary symbols and noise10,19. After cleaning, the input is fed through strong feature extractors such as transformer-based language models (e.g., BERT, RoBERTa) that extract strong contextual semantic long-range dependencies23,31. The social network activity patterns and information spread dynamics of users are modeled through GNNs which require both relational network structures and diffusion mechanisms to detect disinformation. For strong decision making, the resultant of these diverse feature representations is combined through inter-modal or multi-modal approaches blending textual, visual, and relational signals6,24. The model becomes able to detect fake content characteristics that individual modalities cannot detect on their own through this combination. Then, a meta-learning ensemble mechanism pools the predictions from several base learners like CNNs, LSTMs, GNNs, and transformers1,12,22. The model applies this layer to change output weights during execution based on confidence levels and contextual reliability for enhanced performance on new data. The system produces two classification results for real and fake content with their respective confidence levels. The system design contains independent modules which enable adaptable operation with various datasets for deployment across various platforms and media types. In practice, α is optimized through gradient descent as part of the model’s learnable parameters, and no separate outer optimization loop is required. Validation metrics are used only for monitoring and early-stopping purposes, not for explicit gradient-based optimization.

Final architecture

the final architecture of framework combines the transformer, the GNN and the meta-learned ensemble into a system that can efficiently search and identify fake news. Due to the transformers and the GNNs, the system can model the text in messages and the rumours spreading in social networks2,8. The system operates on news articles and the underlying graph that indicates how users, articles and sources are related to each other in the first phase. The preprocessing phase determines useful features from the text content and from the graph networks. The layer then operates on the text into a form that serves the purpose of the transformer model and the graph is structured in a way as to store any interactions and connections to serve the purpose of identifying fake news. Then the structure performs two workflows simultaneously: one for the transformer model and another for the graph neural network. Most of the applications of this methodology rely on the transformer model to enable the system to derive deep meanings from the content of the news article23. The self-attention of the transformer allows it to view the deep relationships between various words in the text10. The disadvantage is that the GNN module discovers how the users, articles, and sources are connected to one another within the network by using the graph data29. Being a graph model, the GNN is able to view how misinformation is spreading and identify any patterns that seem to exist because of social media connectivity4,13. Both models, once trained, generate outputs which are input to the meta-learned ensemble module. The module adapts itself as new data gets published. scales each model’s output by a learned weight, α. meta-learning is applied on the validation set in order to discover it3,9. If the ensemble weight is learned optimally, the method effectively combines the most informative features from both models while minimizing the overall prediction error. This ensures that the final prediction, derived from the weighted combination of outputs, is as accurate and reliable as possible11,20. The output of the ensemble module is the predicted label, either real or fake. The system makes use of the right and standard evaluation metrics like accuracy and the F1-score. ROC-AUC clearly shows the capability of our system to identify fake news against other approaches. using systems12, and7. Figure 3 shows the workflow of the GETE system for fake news detection, integrating text, graph, and ensemble modules. The integration layer optimizes α jointly with all network components, allowing the model to balance semantic and relational cues without requiring any external optimization loop.

Datasets

We tested our proposed hybrid method using two broadly recognized datasets (LIAR, FakeNewsNet) that are commonly used in fake news detection research10,24. These datasets allowed us to assess both the semantic content of the text and the relational patterns in how fake news spreads13,27. Below, we provide a more detailed explanation of the two datasets used.

-

i)

LIAR Dataset: LIAR dataset is a common dataset used in fake news detection and consists of 12,836 short political statements taken from fact-checking websites like PolitiFact15. The statements are described as in one of six truth levels, ranging from “false” to “pants-fire,” “barely-true,” “mostly-true,” and “true”26. This definition aligns with the LIAR dataset’s labeling scheme, where fabricated and highly inaccurate statements fall under “False,” while partially true or misleading statements fall under intermediate labels. The metadata also contains information regarding the speaker, the subject matter of the statement, as well as the context in which the statement is being made. Such metadata can be helpful in determining how effective it is in terms of context as well as topic-based disinformation22,30. For instance, accusations concerning various public figures or parties can activate some linguistic tendencies or biases that can impact the model’s performance14. The information enables us to examine the extent to which the method handles sentences that have no evidently perceivable symptoms of falsehood but need greater linguistic and situational awareness23,29. We transform the dataset into a binary classification task in a manner such that it approaches real-world situations as closely as possible, where disinformation will be labeled as neat “True” or “False” containers33. The simplification categorizes the groups “mostly-true,” “half-true,” and “true” in “True,” and barely pants-fires, false and true under “False”5. LIAR dataset is a good test for measuring how well the model can detect fine misinformation in short messages which have been characteristic of political disinformation. It is especially good at evaluating transformer models like BERT and RoBERTa for text understanding capacity4.

-

ii)

FakeNewsNet Dataset: FakeNewsNet dataset is one of the biggest and most comprehensive datasets capable of identifying fabricated news4,8,27. It supports both content-based and relational (graph) data. Thus, making it appropriate for measuring hybrid models containing text and network variables6,13,30. FakeNewsNet integrates news articles from two reputable fact-checking sites, PolitiFact and GossipCop, and a set of metadata, including publisher name, user interaction (likes, retweets, etc.), and social propagation measures15,26. This social interaction information is accumulated in the form of graphs, with nodes as sources, articles, and users, and edges as relationships between them entities14,29. The most significant advantage of the FakeNewsNet dataset is that it contains propagation graphs, which are representations the sharing of articles through social networks31. This functionality allows us to study the graph-based aspect of our hybrid method, i.e., the ability of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to learn the social dynamics of false news dissemination22. The temporal features are also present in the dataset, i.e. we can see how the dynamics of spreading fake news evolve over time20. This is particularly key to the identification not just of false news, but of developing or adapting misinformation that circulates between different user groups28. FakeNewsNet is helpful in ascertaining how much the proposed model makes use of text information (from the articles) with relational signals (of user interaction and source trustworthiness) in an evolving social environment21,23,30,31. It also provides a varied collection of articles of varying levels of reliability, which helps in measuring the extent to which the model generalizes to other news content19.

The two datasets present different testing scenarios which help us evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed model. The LIAR dataset is particularly concerned with text-based disinformation within the framework of a controlled, political context2,23, while FakeNewsNet offers a realistic environment to learn how news stories propagate and change over time with social media networks7,8,29. The model receives testing from both text-based and relationship-based evaluations which enables us to measure its ability to detect false news effectively1,3,9. They also form a good basis for comparing different fake news detection methodologies. Although LIAR emphasizes the work of textual semantics and political bias10,24, FakeNewsNet emphasizes the role of social dynamics and user actions in the diffusion of misinformation4,22,31. Table 2 summarizes the LIAR and FakeNewsNet datasets including article count, average length, and graph details.

It is important to note that in this work we restrict the LIAR dataset to a binary classification setup (‘True’ vs. ‘False’), following prior studies such as Wang (2017) and Bhatt et al. (2021). The original six-class labels were merged into two groups to better reflect real-world misinformation detection settings. Experiments on the full multiclass setup are beyond the scope of this paper.

Preprocessing

Preprocessing is required before feeding the raw data to the model and involves a series of transformations actions that are aimed at processing text and graph data30. At the text processing phase, the text data is tokenized using the BERT tokenizer2,6. The tokenizer divides the text into tokens and transforms it into a form that is compatible with the BERT model. Since BERT models are case-sensitive, the uncased version of BERT is employed, i.e., all the characters are lower case10,23. In a try to have fixed input size throughout different documents, a token length constraint of 256 is utilized24,32. After tokenization, non-ASCII characters are removed to avoid any interference in model processing so that the text is readable and understandable. Also, stopwords that are common, and are normally not required for understanding the core meaning of a sentence, are removed using the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK)33. For stop-word removal, we used the standard NLTK English stop-word list, supplemented with an additional set of platform-specific tokens such as “rt”, “via”, and common URL fragments (e.g., “http”, “https”, “www”). This combined stop-word list helps remove non-semantic artifacts common in social-media text. The maximum token length for each article was set to 256 tokens, and the BERT uncased tokenizer was employed for consistent text normalization. This assists in reducing noise within the data in a way that the model can concentrate on more significant terms7. Simple text cleaning, such as removing special characters and unwanted punctuation, is also done to enhance the quality of the input data20,25. In the construction step, a graph is built to illustrate the relationships between various entities, as model uses GNNs13. The graph has three types of nodes: users, articles, and sources. They are connected with edges that represent interactions, i.e., user-shares-article or source publishes-article15. The figure is plotted using the NetworkX library, a Python library that is meant for construction and manipulation of complex networks. PyTorch Geometric is also used for processing the graph data in deep learning such that the model can handle graph-based data structures27,29. Extracting features is the most important aspect of enhancing the ability of the model to distinguish between genuine and artificial information4,22. User-level characteristics consider the age of the account, as this is utilized in the determination of the credibility of a user based on how long they have been active on the site. The user’s number of followers is another important feature, providing an indication of their dissemination and influence in the network19,31. Tweeting activity, which tracking the frequency at which a user tweets or interacts with material, is also present, as it may indicate a user’s frequency of influence or credibility15,28. For articles, various features are extracted that aid in the assessment of their trustworthiness. Text length is one of them features, because longer, more detailed articles will be read as more authoritative than short, sensationalized ones9,11. Subjectivity of the articles is also assessed, since extremely subjective language may be evidence of fraudulent or biased content3,26. Publisher bias is also an important feature, since the political orientation of the publisher may affect the validity of the article5,20. In treating the data in this manner, both textual and relational features are accurately captured, such that the hybrid model can effectively identify false news1,12. Table 3 provides an overview of different fake news detection approaches highlighting their strengths, limitations, use cases, complexity, interpretability, scalability, and performance. The datasets became more understandable through our exploratory data analysis (EDA) which included topic modeling and community detection and contextual cue analysis. We tested different weighting techniques for topic modeling30 to identify the most suitable method for extracting vital topics. The researchers used community detection methods9 to group documents into clusters which exposed hidden patterns in the social network structure. The researchers used entity mentions and hashtags and temporal patterns from the context to enhance topic representation which led to improved results4. The EDA provides researchers with knowledge about document topic distribution patterns and document relationships which guides the creation of models and evaluation techniques.

Exploratory data analysis (EDA)

To better understand the characteristics of the LIAR and FakeNewsNet datasets, we conducted an exploratory data analysis (EDA). Table 4 presents descriptive statistics, including the number of documents per class, average and maximum document length, and vocabulary size. LIAR consists of 12,836 short political statements, averaging only 21 words per statement, which highlights its suitability for testing transformer-based semantic models. FakeNewsNet, by contrast, contains over 22,000 articles with an average of 412 words, offering a much richer semantic space. Moreover, FakeNewsNet includes social graphs with over 1.3 M edges, which is crucial for evaluating the relational reasoning capacity of GNNs. Figure 5 shows the class distributions for both datasets. LIAR is relatively balanced between True and False labels, while FakeNewsNet exhibits a slight skew toward Fake. Length distribution histograms further show that LIAR claims are short and concentrated, while FakeNewsNet articles vary widely in length, reflecting differences between claim-level and article-level datasets.We also analyzed thedistribution of unigrams and bigrams. In LIAR, the most frequent unigrams included political entities (e.g., “president,” “congress”), while FakeNewsNet frequently contained sensational bigrams such as “breaking news” and “shocking claims.” These linguistic signals, combined with relational propagation patterns, motivated the design of our hybrid approach.Overall, EDA highlights that LIAR challenges models with very short, context-dependent statements, while FakeNewsNet demands integration of both textual semantics and social graph structures. These insights informed the architecture of our proposed GETE framework.

Evaluation metrics

The performance of proposed model was evaluated using standard classification metrics, offering a comprehensive view of how well it performs across various domains. Accuracy (Acc) is the ratio of correct predictions, illustrating how well the model performs in general3,32. Precision (P) measures the ratio of correctly classified real news among all predictions made as real news. This is important when the cost of false positives is high, especially in areas like politics or public health6,9. Recall (R) estimates the fraction of actual real news that the model picks up correctly, and this is significant in the instance where missing actual news (false negatives) is detrimental15,23. The F1-Score (F1) is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a balanced estimate in the situation of unbalanced classes because it takes into account both false negatives and false positives1,21,22. In addition to these fundamental measures, ROC-AUC is used to measure the discriminatory power of the model to classify between the classes of true and fake news14,25,31. It plots the true positive rate (recall) against the false positive rate, and the area under the curve (AUC) is a general indicator of the discrimination ability of the model12,30. In order to further analyse the performance of the model, confusion matrices are used to show the predicted against actual classes, helping to identify where the model may be failing. Precision-recall curves give more information on how the model sacrifices precision and recall at various thresholds, particularly for imbalanced datasets where accuracy can be not suitable to apply 11]. Finally, considering misclassified examples is helpful for determining the circumstances in which the model fails and for guiding future improvements11.

We compare our suggested method with some robust baseline models2,6,33 to evaluate its effectiveness and emphasize their advancements beyond current methods. These baselines2,6,33 cover classical machine learning, deep learning, graph-based models, and newer hybrid architectures. Traditional methods such as SVM and Logistic Regression are included since they are interpretable and simple to understand, although they are strongly dependent on manually built features such as TF-IDF and n-grams, and can only model shallow semantic patterns in news text20. Some of the DL baselines methods are CNNs and RNNs, specifically Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, which have extensively been applied in imitation news detection tasks5,7,24. While CNNs excel at local textual feature extraction and RNNs are well suited for sequential modelling, both have trouble with long-distance dependencies and context comprehension when compared to transformer models9,23. Transformer-based baselines include BERT and RoBERTa, which are the state-of-the-art performance on most NLP tasks as they can learn rich linguistic patterns and express them in a self-attention format2,6,10. However, these models treat individual news stories in isolation and don’t take into account social context or propagation patterns, therefore constraining their resilience to concerted disinformation assault15,30. Graph-based methods like GCN and GAT are employed due to their capability to represent relational information and user-article interactions8,13,31. They use network structures in an effort to discover propagation dynamics and user credibility, which are critical for detecting fake news14,29. They usually perform below par in text semantic comprehension4,22. Figure 4 presents the flowchart of the GETE detection pipeline, from data input to final classification. The choice of evaluation metrics is guided by dataset characteristics and task requirements7. For binary classification tasks with class imbalance, precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC are reported alongside accuracy to provide a balanced assessment. For multi-class datasets, macro- and weighted-average metrics are used to account for class distribution disparities. This selection ensures that performance evaluation reflects the true capability of the model across different data scenarios.

We also evaluate our proposed Graph-Enhanced Transformer Ensemble (GETE) model in an extensive manner with respect to a number of baseline methods2,6,33 in this section. Quantitative results are provided to support this analysis from standard classification metrics and qualitative insights are provided about model behaviour. We evaluate on accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score and ROC AUC to provide a balanced overview of the performance in fake news detection5,14,32. On both LIAR and FakeNewsNet datasets, we show that naturally evolved representations in the form of GETE out perform traditional approaches such as SVM and Logistic Regression that are restricted by their reliance on hand crafted feature and shallow text representations3,19,20. In terms of word attention, CNN and LSTM based deep learning baselines outperform classical approaches by capturing local and sequential patterns, but there are long range dependencies and contextual semantics they cannot capture, when compared to transformer-based models2,6,24. Transformer architectures such as BERT and RoBERTa have shown much stronger performance through context aware modelling afforded by self-attention mechanics2,10,23. These models work at article level and do not take into account relational structures and social propagation patterns as crucial for recognizing coordinated fake news dispersion13,26,31. However, GCN and GAT provide a powerful machinery for graph based relational structure modelling. However, these models are only effective in capturing social interaction and keeping track of node dependencies and do not excel deeply in linguistic features which results in poor understanding with the absence of semantic and contextual knowledge8,15,30. For hybrid baselines, CSI and HGCN attempt to connect the gap between textual and structural information9,12,25. Although the mechanisms of their fusion increase their robustness, the majority of them adopt fixed or shallow integration strategies which do not adaptively exploit the benefits of each individual modality11,22,33. To address this shortcoming, our GETE model uses a meta learned ensemble mechanism which adapts the relative importance of transformer and GNN component of the ensemble with respect to validation feedback1,21,28. GETE’s adaptive fusion outperforms even the best performing hybrid baselines. Owing to balanced performance, GETE exhibits the highest quantitative accuracy and F1-scores across both datasets3,5,326,29. show that with their precision-recall curves they have superior precision stability and that their ROC-AUC scores indicate strong discriminative capacity. Qualitative analysis also demonstrates that GETE is robust to processing content that is ambiguous, misleading or even coordinated by source (or users) or manipulated in some way20,27,31. We train and test this methodology relative to other state-of-the-art techniques by an exhaustive evaluation demonstrating how our strategy not only attains state-of-the-art efficiency for detecting false news but also offers a generalizable and extensible framework for taking advantage of both semantic and relational features of news articles2,22,30. To comprehensively test the proposed GETE framework, we performed ablation studies aimed at estimating the transformer, GNN, and meta-learned ensemble components’ contributions. Experimental setups used 5-fold cross-validation, and the performances were recorded as mean ± standard deviation. Grid search optimised hyperparameters over learning rates, embedding sizes, number of layers, and dropout rates for enhancing model performance. In addition, training and inference times were recorded for measuring computational efficiency. These methods ensure a comprehensive and reliable evaluation of the framework for a range of datasets and settings.

Results and discussion