Abstract

Cardiac arrest in nonagenarian and centenarian ICU patients carries high mortality, yet the prognostic role of early blood pressure (BP) parameters remains unclear. While most studies have examined nadir or average values, the clinical significance of the highest very early systolic (SBP), diastolic (DBP), and mean arterial pressure (MAP) has not previously been investigated. This study aimed to evaluate whether these peak values within the first 24 h carry prognostic importance in this vulnerable population. We conducted a retrospective multicenter cohort study using data from the ANZICS Adult Patient Database (2010–2024), including 219 patients aged ≥ 90 years admitted to the ICU following in-hospital cardiac arrest. The highest SBP, DBP, and MAP values recorded within the first 24 h were analyzed. Piecewise Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for age, sex, and SOFA score assessed the association between BP parameters and 30-day and 1-year mortality. 30-day and 1-year mortality were 58.0% and 65.8%, respectively. Lower SBP, DBP, and MAP were consistently associated with higher mortality. Each 1 mmHg decrease below SBP 140 mmHg, DBP 74 mmHg, and MAP 100 mmHg decreased the hazard of 30-day mortality by 2.2% (HR 0.978; 95% CI 0.966–0.991), 2.9% (HR 0.971; 95% CI 0.948–0.994), and 2.1% (HR 0.979; 95% CI 0.964–0.994), respectively (all p < 0.05). These associations persisted at 1 year: SBP (HR 0.980; 95% CI 0.968–0.993), DBP (HR 0.980; 95% CI 0.960–1.000), and MAP < 98 mmHg (HR 0.983; 95% CI 0.971–0.995). BP values above these thresholds showed no significant protective effect. SBP and DBP demonstrated a moderate positive correlation (r = 0.553, p < 0.001). In patients ≥ 90 years old admitted to ICU after cardiac arrest, early hypotension—particularly SBP < 140 mmHg, DBP < 74 mmHg, and MAP < 98 mmHg—was independently associated with increased short- and long-term mortality. As SBP and DBP represented the highest recorded values within the first 24 h, these findings highlight that even peak pressures below these thresholds carry prognostic significance, underscoring the value of early BP assessment and vigilant haemodynamic management in the oldest ICU population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiac arrest in the intensive care unit (ICU) is a critical event with substantial morbidity and mortality implications, occurring in approximately 40 per 1,000 ICU admissions1,2. As the global population ages, nonagenarians and centenarians represent a growing subset of ICU patients experiencing these events3. Prognosis in this group remains particularly poor, with ICU mortality ranging from 54% to 88% and in-hospital mortality nearing 100% in some cohorts3,4. Even among those who achieve return of spontaneous circulation, 1-year survival rarely exceeds 23%4.

Although blood pressure parameters have been linked to outcomes after cardiac arrest in general populations5,6,7, their specific association with mortality in nonagenarian and centenarian ICU patients remains largely unknown. Prior evidence shows that both hypotension and specific blood pressure thresholds significantly influence neurological outcomes and survival after cardiac arrest6,7, yet these findings were derived predominantly from younger or mixed-age cohorts5,7,8,9,10 and may not be generalisable to very elderly patients. Advanced age is often accompanied by cardiovascular disease, altered vascular compliance, and greater blood pressure variability—factors that may modify the prognostic value of haemodynamic parameters post resuscitation11,12.

The clinical importance of investigating early blood pressure parameters in this vulnerable population lies in the potential to optimise post-resuscitation care strategies and improve risk stratification accuracy, particularly given the substantial healthcare resource utilisation and the complexity of family decision-making surrounding end-of-life care in nonagenarians13. Furthermore, the identification of potentially modifiable haemodynamic targets might inform age-specific, evidence-based guidelines, reducing futile interventions while maximising the potential for meaningful recovery in carefully selected cases.

To our knowledge, no prior studies have specifically examined the relationship between early blood pressure management and both short- and long-term mortality in nonagenarian and centenarian patients after in-hospital cardiac arrest, highlighting a key gap in geriatric critical care. Therefore, this study aimed to address this gap by evaluating the associations between early blood pressure parameters and mortality outcomes in this unique and vulnerable ICU population.

Methods

Ethics approval and study design

This study was approved by the Alfred Ethics Committee (project No. 253/24). The requirement for informed consent was waived by (The Alfred Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee) because this study was retrospective and based on de-identified data. Data analysis commenced only after ethics approval was obtained. The study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines14. The study was conducted in compliance with the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data sources, study population, and variables

De-identified patient-level data were obtained from the ANZICS Adult Patient Database, which includes demographic characteristics, clinical variables, interventions, and outcomes for patients admitted to 98% of ICUs in Australia and 68% of ICUs in New Zealand15. Data collection was coordinated by the ANZICS Centre for Outcome and Resource Evaluation. This study included nonagenarian and centenarian patients admitted to the ICU between 2010 and 2024 after in-hospital cardiac arrest, who were identified according to ICU admission source and APACHE III-J diagnostic codes. The extracted demographic variables included age, sex, admission source, admission type, discharge destination, and dates of ICU and hospital admission. For each patient, the highest recorded systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and mean arterial pressure (MAP) within the first 24 h after ICU admission were analyzed. The clinical data included frailty status, which was assessed with the Clinical Frailty Scale, and illness severity, which was evaluated with the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) III-J score, and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score. These measures were documented at the time of ICU admission. Relevant comorbidities (such as immunosuppression; malignancy; and chronic respiratory, cardiovascular, hepatic, or renal conditions) were also recorded. All variables had less than 5% missing data and were analyzed with complete-case methods without imputation.

Study outcomes

The primary outcomes were as follows:

(1) the association between SBP and DBP, assessed with Pearson’s correlation coefficient and simple linear regression to quantify the strength and direction of the relationship;

(2) the independent association between each blood pressure parameter and mortality risk, estimated with piecewise Cox proportional hazards models at each time point.

Mortality status and dates of death were ascertained from hospital electronic medical records and verified with linked national death registry data.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted in R software, version 4.4.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Data management, descriptive summaries, and all regression modeling were performed with validated, peer-reviewed R packages, including survival, rms, pROC, dplyr, and ggplot2. Continuous variables are reported as means with standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges, as appropriate, and categorical variables are summarized as counts and percentages.

The relationship between SBP and DBP was examined with Pearson’s correlation coefficient and simple linear regression. Linearity was assessed through residual versus fitted value plots and partial residual plots. Regression coefficients, p-values, and the coefficient of determination (R²) were determined to quantify the strength and significance of the associations. Additionally, for descriptive visualization, blood pressure values were grouped into clinically relevant intervals to generate histograms depicting bin-wise mortality proportions for both 30-day and 1-year outcomes.

To assess the assumption of linearity between each blood pressure parameter and the log hazard, we fitted restricted cubic splines with four knots with the rms package. Linearity was assessed both visually, through inspection of the spline plots (ggplot2 package), and formally, with likelihood ratio tests comparing the spline models to models with a single linear term. Both approaches consistently indicated evidence of non-linearity for each parameter.

To determine whether each blood pressure parameter could be reasonably modeled with a piecewise linear function, we used a data-driven grid search implemented in base R and the rms and survival packages. For each parameter, we tested a range of clinically plausible cut-points (for example, 100–140 mmHg for SBP) by fitting Cox proportional hazards models that allowed the slope to differ below and above each candidate threshold. We calculated the Akaike information criterion for each model to compare relative fit and selected the cut-point with the lowest Akaike information criterion as the best threshold. This search was repeated for three model specifications: one unadjusted; one adjusted for age and sex; and one further adjusted for SOFA score. The data driven cut-point was then compared with the inflection point identified through visual inspection of the spline plots, and no meaningful difference was observed between approaches. To assess the robustness of the data-driven thresholds and reduce the risk of overfitting, internal validation was undertaken using bootstrap resampling with 200 iterations to derive optimism-corrected estimates of model performance, and restricted cubic spline models without dichotomisation were fitted as a sensitivity analysis to confirm the robustness of the main inferences.

The final piecewise linear functions were formally compared with the original restricted cubic spline models with likelihood ratio tests (via the anova.rms function in the rms package) to confirm that the simplified piecewise representation did not result in a significant loss of model fit. Residual plots and diagnostic checks (rms and survival packages) confirmed that the piecewise linear specification provided an adequate approximation of the non-linear relationships identified in the spline analyses.

The proportional hazards assumption was assessed for each blood pressure parameter and globally with Schoenfeld residuals (cox.zph function in the survival package) and log-minus-log plots. The assumption was satisfied for all three parameters and for the overall models at both 30-day and 1-year time points.

After verifying that the proportional hazards assumption was not violated for model III (modified for sex, age, SOFA score), we estimated model III’s hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals for each blood pressure parameter, with the piecewise linear terms fitted in the rms and survival packages. For each parameter, separate hazard ratios were calculated for values below and above the data-driven cut-point within the same Cox proportional hazards model. This procedure was applied consistently for both 30-day and 1-year mortality outcomes, with models adjusted for age, sex, and SOFA score where specified.

All tests were two-sided, and a p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 219 nonagenarian and centenarian patients admitted to the ICU after in-hospital cardiac arrest were included; 58.0% died within 30 days, and 65.8% died within 1 year (Tables 1 and 2).The median age was similar between survivors and non-survivors (91.3; 2.8 vs. 91.8; 2.0 years; p > 0.4). Patients who died within 30-day or 1-year had significantly higher APACHE III and SOFA scores at ICU admission (all p < 0.001), reflecting more severe multi-organ dysfunction and physiological backgrounds.

Non-survivors, compared with survivors, consistently showed lower maximum and minimum SBP, DBP, and MAP (all p < 0.01); had higher lactate levels (30-day: 4.1 vs. 2.0 mmol/L; 1-year: 3.6 vs. 2.0 mmol/L; both p < 0.001); had higher maximum heart rates; and had greater metabolic acidosis (lower pH and bicarbonate, all p < 0.01). Poorer markers of renal impairment were observed among non-survivors, who had higher maximum and minimum creatinine and urea concentrations and lower urine output than survivors (all p < 0.001). Blood glucose levels were also higher in non-survivors than survivors (maximum glucose: 11.5 vs. 9.0 mmol/L for 30-day; p = 0.001).

Overall, patients with elevated risk of short-term and long-term mortality in this oldest ICU population were characterized by diminished early blood pressure parameters, elevated lactate, perturbed acid–base status, and impaired renal and metabolic profiles.

Association between systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure

Among the study cohort, SBP and DBP showed a moderate positive linear relationship (Fig. 1). The Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.553 indicated a statistically significant direct association between measures. Linear regression analysis indicated that for each 1 mmHg increase in SBP, DBP increased by an estimated 0.328 mmHg (95% CI (0.260–0.400); p < 0.001), with an intercept of 20.74 mmHg. The proportion of variance in DBP explained by SBP alone was modest (R² = 0.306). Linearity was confirmed through visualization of residual plots (Supplementary Fig. 1).

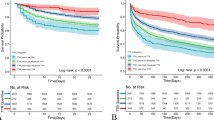

Associations between blood pressure parameters and short-term mortality

A simple visualization of the association between blood pressure parameters and 30-day mortality (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 2,3) suggested that lower SBP was associated with a higher risk of death within 30 days. Mortality decreased as SBP increased to moderate levels, and showed a slight increase thereafter at very high blood pressures. DBP demonstrated a similar non-linear trend, with higher mortality at lower DBP values and more stable mortality at intermediate and higher ranges. The mortality risk was greatest at lower MAP values and steadily declined with increasing MAP, and no clear evidence of rising mortality with higher MAP values was observed. Overall, these findings indicated that lower SBP, DBP, and MAP were associated with higher short-term mortality in this cohort.

The associations of SBP, DBP, and MAP with 30-day mortality were further evaluated with piecewise Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for age, sex, and SOFA score (see Table 3).For SBP, a clear nonlinear relationship was observed. Each 1 mmHg decrease in SBP below 140 mmHg was associated with a 2.2% decrease in the hazard of 30-day mortality (adjusted HR, 0.978; 95% CI, 0.966–0.991; p = 0.001). Above 140 mmHg, although the association was not statistically significant (adjusted HR, 0.991; 95% CI, 0.975–1.012; p = 0.256), the spline curve demonstrated a continued gradual downward trend in hazard, thus indicating that higher SBP remained weakly protective within the observed range.

For DBP, each 1 mmHg decrease below 74 mmHg was associated with a 2.9% increase in the hazard of short-term mortality (adjusted HR, 0.971; 95% CI, 0.948–0.994; p = 0.012). Above 74 mmHg, the association was not statistically significant (adjusted HR, 1.010; 95% CI, 0.975–1.050; p = 0.522), and the hazard ratio curve remained generally stable without evidence of a clear upward or downward trend.

For MAP, a robust association was observed for values at or below 100 mmHg: each 1 mmHg decrease was associated with a 2.1% increase in the hazard of 30-day mortality (adjusted HR, 0.979; 95% CI, 0.964–0.994; p = 0.006). Above this threshold, although the association was not statistically significant (adjusted HR, 1.000; 95% CI, 0.980–1.030; p = 0.753), the spline curve showed a subtle upward trend in hazard ratio suggesting a mild increase in risk with higher MAP values during the short-term period. However, this pattern did not reach statistical significance in the piecewise estimate.

Overall, these findings demonstrated that lower SBP, DBP, and MAP values were associated with higher short-term mortality risk, particularly below clinically accepted consensus thresholds16. The stable or only mildly increasing hazard trends observed above these cut-points, despite being statistically non-significant, highlighted that hypotension was the dominant predictor of short-term mortality in this cohort.

Associations between blood pressure parameters and long-term mortality

A simple visualization of the association between blood pressure parameters and 1-year mortality is shown in Fig. 3 and Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5. Patterns for 1-year mortality were generally consistent with those observed for 30-day mortality. Lower SBP was associated with higher long-term mortality, and the risk decreased at moderate SBP levels and slightly increased at very high blood pressures. DBP also exhibited a non-linear association, with elevated mortality at lower DBP values and relatively stable risk across moderate to higher ranges. Higher mortality was observed at lower MAP values, and a gradual decline in risk was observed with increasing MAP; however, no substantial increase was observed at higher MAP levels. These trends suggested that lower SBP, DBP, and MAP were each associated with higher risk of death at 1 year.

The associations of SBP, DBP, and MAP with long-term (1-year) mortality were further evaluated with piecewise Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for age, sex, and SOFA score (Table 4).For SBP, a clear nonlinear association was identified. Below 140 mmHg, each 1 mmHg decrease in SBP was associated with a 1.6% increase in the hazard of 1-year mortality (adjusted HR, 0.984; 95% CI, 0.974–0.994; p = 0.003). Above 140 mmHg, the association was not statistically significant (adjusted HR, 0.991; 95% CI, 0.970–1.013; p = 0.381); however, the relatively flat hazard ratio curve indicated minimal additional risk with higher SBP values, in agreement with the short-term pattern.

For DBP, similar nonlinearity was observed. For values ≤ 74 mmHg, each 1 mmHg decrease corresponded to a 2.0% decreased hazard of 1-year mortality (adjusted HR, 0.980; 95% CI, 0.960–1.000; p = 0.046). Above 74 mmHg, the association was not statistically significant (adjusted HR, 1.010; 95% CI, 0.980–1.040; p = 0.411); however, a slight upward trend in hazard (Fig. 3b) suggested a modest increase in risk at higher DBP over the longer term, which was not observed in the short-term analysis.

For MAP, each 1 mmHg decrease below 98 mmHg was associated with a 1.7% decreased hazard of 1-year mortality (adjusted HR, 0.983; 95% CI, 0.971–0.995; p = 0.007). Above 98 mmHg, the association was not statistically significant (adjusted HR, 1.010; 95% CI, 0.980–1.050; p = 0.458); nonetheless, a mild upward trend in the spline curve indicated a subtle increase in long-term mortality risk at higher MAP values, in contrast to the stable trend seen for short-term outcomes.

Subgroup analysis

In subgroup analyses stratified by sex, the associations between systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial blood pressure and mortality remained consistent across sexes. For 30-day mortality, both male and female patients demonstrated similar non-linear trends, with higher mortality at lower blood pressure values and a plateau or slight increase at higher values (Supplementary Fig. 6). These patterns were preserved for 1-year mortality, with no substantial sex-based effect modification observed (Supplementary Fig. 7). Overall, these findings suggest that the prognostic value of blood pressure parameters did not differ meaningfully between males and females. In subgroup analyses excluding patients with a treatment limitation order at admission, as well as subgroup analyses stratified by limitation status, the overall non-linear associations between blood pressure parameters and mortality were preserved. Curve shapes and effect estimates were consistent across groups, with only minor variations in hazard ratio magnitude (Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9).

Sensitivity analysis

When the models were repeated using the lowest blood pressure within the first 24 h instead of the highest, the associations with mortality were broadly consistent with the primary findings. For both 30-day (Supplementary Fig. 10) and 1-year mortality (Supplementary Fig. 11), risk was greatest at low pressures, declined towards moderate ranges, and showed little evidence of excess hazard at higher pressures, mirroring the overall pattern observed in the main analysis.

When models were additionally adjusted for APACHE III-J (Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13), the overall non-linear associations between systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial pressures with both 30-day and 1-year mortality remained consistent with our primary analyses. The curve shapes were largely unchanged, with lower pressures associated with increased mortality risk and risk attenuation at moderate pressures.

Discussion

Key findings

This study identified several clinically important findings regarding blood pressure parameters and outcomes in nonagenarian and centenarian ICU patients after in-hospital cardiac arrest. First, lower SBP, DBP, and MAP within the first 24 h after ICU admission were significantly associated with higher short-term (30-day) and long-term (1-year) all-cause mortality. Second, specific thresholds for each parameter were identified: an SBP below 140 mmHg, DBP below 74 mmHg, and MAP below 98 mmHg were consistently associated with elevated mortality risk; these non-linear associations demonstrated the greatest risk at the lower extremes. Third, a moderate positive linear relationship between SBP and DBP confirmed their physiological interdependence.

Relationship of the findings to the literature

This study’s findings align with and extend existing evidence of the prognostic importance of early blood pressure parameters in critically ill patients, and particularly emphasize their significance in nonagenarian and centenarian populations after in-hospital cardiac arrest. Numerous studies have established the adverse outcomes associated with hypotension in critically ill populations. Vincent et al. have systematically reviewed the literature and demonstrated a significant correlation between lower mean MAP and higher mortality across various critically ill patient groups17. Similarly, Dünser et al. have identified persistent hypotension as a key predictor of elevated mortality risk in patients with shock and severe infections, thus reinforcing the clinical significance of maintaining adequate arterial pressures18.

Prior studies specifically focusing on populations with cardiac arrest have highlighted the critical influence of early haemodynamic instability on outcomes. In a retrospective analysis by Kilgannon et al., early hypotension after cardiac arrest was independently associated with elevated hospital mortality, thus emphasizing the importance of careful haemodynamic management in these patients19. These findings are consistent with our observations, and underscore the need for vigilant monitoring and timely interventions in managing blood pressure after cardiac arrest.

Regarding age-specific implications, our study notably highlighted blood pressure-related mortality risks specifically within the oldest ICU patients, a population traditionally underrepresented in critical care research. Previous studies in younger cohorts have identified critical blood pressure thresholds for optimal outcomes. Lamontagne et al. have reported that individualized blood pressure targets significantly influence survival outcomes in general critically ill populations, particularly in septic shock20. Asfar et al., in a randomized controlled trial, have further demonstrated that targeting higher MAP in patients with septic shock might potentially benefit specific subpopulations, particularly older adults or patients with chronic hypertension21. Our study expanded on those findings by identifying distinct blood pressure associations in nonagenarians and centenarians, and suggesting tailored haemodynamic targets for this demographic.

Moreover, our observation of a moderate positive linear correlation between SBP and DBP aligns with established cardiovascular physiology literature. Gavish et al. have described the physiological interdependence of SBP and DBP, driven primarily by cardiac output and peripheral vascular resistance22. This correlation is physiologically expected, as both SBP and DBP reflect the combined influences of cardiac output, vascular tone, and arterial compliance. Evaluating their association provides internal validation of haemodynamic data integrity and offers insight into whether changes in one parameter parallel changes in the other in this elderly post–cardiac arrest ICU population.

Despite a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis by Niemelä et al23. finding no clear benefit of higher MAP targets after cardiac arrest in predominantly younger cohorts, our results demonstrate that hypotension below identified thresholds (SBP 140 mmHg, DBP 74 mmHg, MAP 98–100 mmHg) was strongly associated with both short- and long-term mortality in the oldest-old. Current guidelines recommend only avoiding hypotension, typically with MAP ≥ 60–65 mmHg or SBP > 100 mmHg23. The markedly higher thresholds observed in our study therefore highlight a potentially distinct haemodynamic profile in very elderly patients, for whom even the highest recorded pressures below these levels were linked to poor outcomes. Given the physiological differences and increased baseline vulnerability of this population, further investigation is required to clarify whether age modifies the effect of BP targets and to determine whether clinically meaningful benefits might be achieved at higher BP levels.

Overall, our findings reinforce the importance of precise blood pressure management in critically ill older patients, particularly after cardiac arrest, and provide valuable data that might inform clinical practice and guide future research aimed at improving survival and functional outcomes in this vulnerable patient population.

Clinical implications

This large multicenter analysis provided compelling evidence that routinely recorded blood pressure parameters within the first 24 h after ICU admission have important prognostic value for the oldest patients who survive in-hospital cardiac arrest. This study is clinically significant because it directly addresses a major gap in evidence: how to interpret and act on early haemodynamic signals in nonagenarian and centenarian survivors of cardiac arrest—a demographic that is expanding rapidly yet remains underrepresented in cardiac critical care trials.

The observed trends consistently linking lower SBP, DBP, and MAP to higher risk of short-term and long-term mortality equip bedside clinicians with practical, objective information to identify patients likely to deteriorate, even when other clinical signs are subtle or non-specific. In real-world ICU practice, in which decisions about escalation or de-escalation of organ support must often be made quickly and in collaboration with families, these blood pressure trends might serve as early, easily measurable markers of physiological vulnerability and limited reserve.

By highlighting these associations, this study has potential to empower intensivists, cardiologists, and ICU nursing teams to use a more proactive and vigilant approach to haemodynamic monitoring in older patients post-arrest. Our results underscore that modest hypotension should not be dismissed as benign in this cohort but should instead prompt careful reassessment for reversible causes, optimization of fluid balance, and timely adjustment of vasopressor or inotropic support. Importantly, the absence of a clear protective effect at higher blood pressure levels may reflect the influence of vasopressor therapy, where elevated values represent treatment intensity rather than intrinsic cardiovascular reserve. This nuance highlights the difficulty of disentangling treatment effects from patient physiology in observational datasets and underscores the importance of interpreting haemodynamic signals in their clinical context.

At the bedside, blood pressure values below the identified thresholds should serve as a red flag, prompting clinicians to reassess for reversible contributors to hypotension (e.g. volume depletion, arrhythmia, sepsis), optimise fluid balance, and consider early titration of vasopressor or inotropic therapy. In addition, these findings support closer haemodynamic monitoring, particularly in the first 24 h, and may justify earlier multidisciplinary discussions about prognosis and goals of care in very elderly postarrest patients.

From a hospital systems perspective, the prognostic value of these early blood pressure patterns might inform better resource allocation and care planning. Patients with persistently low blood pressure might benefit from closer haemodynamic surveillance, higher nurse-to-patient ratios, or earlier palliative care consultation when the goals of care must be clarified in light of realistic survival prospects. This evidence provides a strong rationale for integrating simple, trend-based blood pressure monitoring into routine post–in-hospital cardiac arrest care pathways and incorporating these parameters into hospital-level early warning systems or ICU triage protocols for older patients.

Finally, these findings provide a robust evidence base that might inform future interventional studies examining whether actively preventing downward blood pressure trends, rather than reacting to overt hypotension, could meaningfully improve outcomes in this high-risk group. This study therefore directly supports more precise, age-appropriate, and ethically informed cardiac critical care in the oldest ICU patients, thereby ensuring that treatment decisions are aligned with both physiological realities and patient values.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several notable strengths. First, its use of a large high-quality, binational ICU database including nearly all adult ICUs in Australia and a substantial proportion of ICUs in New Zealand provided robust multicenter coverage and enhanced the generalizability of the findings within these health systems. Second, it specifically examined nonagenarian and centenarian patients who survived in-hospital cardiac arrest. Because this group is highly vulnerable and underrepresented in critical care research, our study fills an important evidence gap. Third, the study’s rigorous data quality, including systematically collected physiological measures and verified mortality data linked through national registries, strengthened the reliability of outcome assessments and survival analyses.

However, this study has several limitations. Firstly, our analysis may be subject to survivor bias, as patients who died before a maximum blood pressure could be recorded within the first 24 h were not represented, potentially underestimating the impact of very early hypotension. Moreover, this was a retrospective observational study, and causality cannot be inferred. Although we adjusted for illness severity using SOFA scores, unmeasured confounders may remain. Third, we used the highest BP values within the first 24 h, which may not reflect cumulative exposure to hypotension or short-term fluctuations. Fourth, our findings may not generalize to ICU populations in other countries or settings with different resuscitation practices. Fifth, key resuscitation variables such as initial cardiac rhythm, time to return of spontaneous circulation, and total duration of resuscitation efforts were unavailable, which may limit interpretation of the associations observed. Furthermore, as the blood pressure thresholds were identified through data-driven spline and grid search methods rather than prespecified a priori, there remains a potential for data-driven bias, which we sought to mitigate through internal validation. Finally, some non-significant findings at higher blood pressure ranges may reflect limited sample sizes in these subgroups, leading to unstable effect estimates and wide confidence intervals, rather than a true absence of association.

Future directions

A large multicenter randomized controlled trial is currently underway comparing lower versus higher mean arterial pressure targets after cardiac arrest and resuscitation (MAP-CARE)6. However, despite this important work, age-related physiological differences mean that results from predominantly younger cohorts may not be directly generalizable to nonagenarian and centenarian ICU patients, underscoring the need for age-specific evidence.

Conclusion

In ICU patients aged ≥ 90 years who survived in-hospital cardiac arrest, early hypotension defined by SBP < 140 mmHg, DBP < 74 mmHg, and MAP < 98 mmHg was independently associated with higher short- and long-term mortality. These findings highlight the prognostic value of early haemodynamic parameters in the oldest ICU population and underscore the importance of close monitoring and avoidance of hypotension, while recognising that causal relationships cannot be inferred and that prospective studies are needed to determine optimal management strategies.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Cook, J. & Thomas, M. Cardiac arrest in ICU. J Intensive Care Soc. 18(2): 173. https://doi.org/10.1177/1751143716674227. Epub 2017 Apr 25. PMID: 28979566; PMCID: PMC5606409. (2017).

Zajic, P. et al. Incidence and Outcomes of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in ICUs: Retrospective Cohort Analysis. Crit Care Med. 50(10): 1503–1512. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000005624. Epub 2022 Jun 14. PMID: 35834661 (2022).

Haar, M. et al. Intensive care unit cardiac arrest among very elderly critically ill patients - is cardiopulmonary resuscitation justified? Scand. J. Trauma. Resusc. Emerg. Med. 32 (1), 84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-024-01259-1 (2024). PMID: 39261863; PMCID: PMC11389322.

Roedl, K. et al. Long-term neurological outcomes in patients aged over 90 years who are admitted to the intensive care unit following cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 132, 6–12 (2018). Epub 2018 Aug 23. PMID: 30144464.

McGuigan, P. J. et al. The effect of blood pressure on mortality following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a retrospective cohort study of the United Kingdom Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre database. Crit Care. 27(1): 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-04289-2. (2023) Erratum in: Crit Care. 2023 May 4; 27(1): 169. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-023-04458-x. PMID: 36604745; PMCID: PMC9817239.

Niemelä, V. H. et al. Higher versus lower mean arterial blood pressure after cardiac arrest and resuscitation (MAP-CARE): A protocol for a randomized clinical trial. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 69 (6), e70040. https://doi.org/10.1111/aas.70040 (2025).

Beekman, N. et al. Petersen, and Emily j Gilmore. Blood Press. Matters after Cardiac Arrest: Is our Target. Too Low? Circulation, 148: Suppl_1, A184 (2023).

Skrifvars, M. B., Ameloot, K. & Åneman, A. Blood pressure targets and management during post-cardiac arrest care. Resuscitation 189, 109886 (2023).

Roberts, B. W. et al. Association between elevated mean arterial blood pressure and neurologic outcome after resuscitation from cardiac arrest: results from a multicenter prospective cohort study. Crit. Care Med. 47 (1), 93–100 (2019).

Jakkula, P. et al. Targeting low-normal or high-normal mean arterial pressure after cardiac arrest and resuscitation: a randomised pilot trial. Intensive Care Med. 44 (12), 2091–2101 (2018).

Laurikkala, J. et al. Mean arterial pressure and vasopressor load after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: associations with one-year neurologic outcome. Resuscitation 105, 116–122 (2016).

Gardner, M. M. et al. Identification of post-cardiac arrest blood pressure thresholds associated with outcomes in children: an ICU-Resuscitation study. Crit. Care. 27 (1), 388 (2023).

Department of Economic and Social Affairs UN. World Population Prospects 2024 (In: United Nations, editor., 2024).

von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Epidemiology 18 (6), 800–804 (2007).

Secombe, P. et al. Thirty years of ANZICS CORE: A clinical quality success story. Crit. Care Resusc. 25 (1), 43–46 (2023).

James, P. A. et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the eighth joint National committee (JNC 8). JAMA 311 (5), 507–520. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.284427 (2014).

Vincent, J. L. et al. Mean arterial pressure and mortality in critically ill patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care. 22 (1), 158. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-018-2095-9 (2018).

Dünser, M. W. et al. Arterial blood pressure during early sepsis and outcome. Intensive Care Med. 35 (7), 1225–1233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-009-1427-2 (2009).

Kilgannon, J. H. et al. Early arterial hypotension is common in the post-cardiac arrest syndrome and associated with increased in-hospital mortality. Resuscitation 79 (3), 410–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.07.019 (2008).

Lamontagne, F. et al. Pooled analysis of higher versus lower blood pressure targets for vasopressor therapy in shock. Intensive Care Med. 44 (1), 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-5016-5 (2018).

Asfar, P. et al. High versus low blood-pressure target in patients with septic shock. N Engl. J. Med. 370 (17), 1583–1593. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1312173 (2014).

Gavish, B., Ben-Dov, I. Z. & Bursztyn, M. Linear relationship between systolic and diastolic blood pressure monitored over 24 h: assessment and correlates. J. Hypertens. 26 (2), 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282f25b5a (2008).

Niemelä, V. et al. Higher versus lower blood pressure targets after cardiac arrest: systematic review with individual patient data meta-analysis. Resuscitation 189, 109862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2023.109862 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Je Min Suh contributed to study conception, data analysis, interpretation of analysis, manuscript drafting and revisions; Jiaying Ye, Stephen Woodford, Anoop N Koshy, Dharshi Karalapillai, contributed to interpretation of analysis and manuscript revisions; Alexandre Joosten and David Pilcher contributed to study conception, interpretation of analysis and manuscript revisions; Dong-Kyu Lee and Laurence Weinberg contributed to study conception, interpretation of analysis, manuscript drafting, revisions and supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Alfred Ethics Committee (project No. 253/24). The requirement for informed consent was waived because this study was retrospective and based on de-identified data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Suh, J.M., Weinberg, L., Ye, J. et al. Highest early blood pressure within 24 hours and mortality after in-hospital cardiac arrest in the oldest ICU patients: A binational cohort study. Sci Rep 16, 1937 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31676-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31676-w