Abstract

In the context of industrial hot-rolled strip steel surface defect detection, where the demands for real-time performance and classification accuracy are paramount, we present EAF-DenseNet121–a lightweight, enhanced model that incorporates edge-entropy attention mechanisms. At the inception of the DenseNet121 architecture, we incorporate a learnable Sobel-based edge extraction branch, which is designed to adaptively delineate defect contours with precision. We have designed an Entropy-Attention Fusion (EAF) module to further refine the model’s performance. This module constructs a four-dimensional tensor, integrating the primary feature map, edge map, and their corresponding local entropy maps. By applying dual-path channel-wise and spatial attention, we achieve a weighted fusion of information, thereby enriching the feature representation. The EAF module replaces three pivotal convolutional layers within the DenseNet framework–immediately following the initial convolution and subsequent to the first and second Transition layers. This replacement enhances feature representation with a negligible increase in additional parameters, leading to a substantial improvement in defect recognition and classification accuracy. Our experimental results, obtained on the NEU-DET dataset, reveal that the enhanced model achieves a classification accuracy of 99.17%, representing an improvement of 2.78% over the baseline. Furthermore, on the GC10-DET dataset, the model achieves a classification accuracy of 82.89%, further validating its strong generalization capabilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hot-rolled steel strips and other industrial metal materials have seen increasingly widespread applications1. However, defects such as surface cracks, oxidation, scratches, and inclusions generated during their production processes2 severely limit product quality and production efficiency, while also driving up operational costs for enterprises. Consequently, achieving precise classification and identification of surface defects in metal steel strips has become a critical challenge urgently facing the manufacturing industry3.

Industrial defect classification technology has evolved from manual visual inspection, traditional image processing, machine learning4, to the current stage dominated by deep learning5. Traditional machine learning methods, such as those combining SVM and HOG features6 or PCA for dimensionality reduction, rely on manually designed features and classifiers. For example, Alloghani and others7 have conducted research on unsupervised and supervised learning in machine learning, utilizing PCA (principal components analysis) for dimensionality reduction8 to remove the correlation between feature data, retaining the necessary information of defects. However, their expressiveness and generalization capabilities are limited in complex backgrounds or scenarios with subtle defects.

With the rise of deep learning, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) such as DenseNet, LeNet-5, AlexNet9, VGGNet, and ResNet have continuously innovated and iterated10. Convolutional neural networks have significantly improved defect classification accuracy through their powerful feature learning capabilities. Yuan et al.introduce an innovative deep learning model GDCP-YOLO11 for multi-class steel defect detection. It combines channel attention from the DCNV2 module and C2f with adaptive receptive fields to enhance the YOLOv8n architecture. Multi-convolutions are used to reduce computational load and generate more feature maps. The algorithm exhibits saturation phenomena and has issues with gradient vanishing. Xie et al.12 propose an advanced framework based on YOLOv10 , which utilizes the SDMS module based on attention-focused aggregation to enhance the backbone network’s feature extraction capabilities. This makes the model more focused on fine-grained13 defect feature information, further improving the performance of detecting steel strip surface defects in high-class similarity and complex backgrounds, while reducing gradient issues.

However, there is less correlation between feature maps14, and although Transformer15 can capture global dependencies, it faces challenges of high computational cost and insufficient attention to local edges. To enhance the utilization of edge map, researchers have proposed various strategies. For instance, Xu et al.16 have introduced a method that fuses traditional edge operators (such as Sobel, Canny17) with ResNet18 features, which increases edge information. While this approach can filter out key features, it lacks adaptability and is prone to interference from edge noise in complex scenarios, making it difficult to match the diverse characteristics of defect edges18. Additionally, some researchers have attempted to improve performance on specific tasks through multi-scale feature extraction or specific network improvements19, yet they still face bottlenecks such as weak correlation between feature maps or the ineffective synergy between shallow detail information and deep semantic information20. In response to this issue, we propose the EAF-DenseNet121 method, which integrates learnable edge detection with entropy attention. This method allows the model to focus on defect edges while maintaining an overall grasp of the image. After embedding it into the deep network, it enhances the model’s ability to identify defect regions, reduces interference from complex backgrounds, and ultimately improves classification performance.

The contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

-

A learnable Sobel edge branch is embedded into the front end of DenseNet121, replacing manual operators, to adaptively extract defect contour features.

-

A four-dimensional tensor is formed by combining the main feature map, edge map, and local entropy map. The EAF module is constructed by dynamically adjusting the fusion weights of edge features and deep semantic features through channel-space dual attention, achieving an optimal balance between relevant details and global information.

-

Three key convolution layers in DenseNet (after the initial convolution and after the first and second Transition) are replaced by EAF, which effectively correlates shallow high-resolution details with deep strong semantic information and strengthens feature representation.

-

The accuracy of the proposed method is approximately 3% higher than that of the state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods. It has been validated on the complex background GC10-DET dataset, highlighting the excellent learning ability and generalization performance of the model.

Methods

Dataset

This study employs NEU-DET21, an open-source dataset of surface defects on hot-rolled steel strips provided by Northeastern University, which includes six categories: cracks, inclusions, scratches, pits, spots, and scale, as shown in Fig. 1. Subsequently, Class1 to Class5 are used to represent each type of defect. Each category contains 300 images. To rigorously evaluate the model’s performance and prevent overfitting, the dataset is stratified and randomly divided into three mutually exclusive subsets: the training set, validation set, and test set, with proportions of 70%, 20%, and 10%, respectively, as detailed in Table 1.

Furthermore, to ensure the model’s generalization capability, we evaluated its performance on the GC10-DET22 public dataset. This dataset consists of surface defect images collected from real-world industrial applications, comprising 10 categories as shown in Table 2. The complex backgrounds of the images, along with the challenges posed by intercategory similarity and imbalanced sample distribution, present significant challenges for defect classification algorithms.All images in the NEU-DET and GC10-DET datasets are resized to 224 \(\times\) 224 pixels and normalized using ImageNet statistics (mean = [0.485, 0.456, 0.406], std = [0.229, 0.224, 0.225]) prior to model input during both training and evaluation.

Model structure

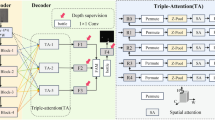

The proposed image classification framework, as illustrated in Fig. 2, is constructed around edge map enhancement and deep feature fusion, with its core components including a learnable edge detection module, an EAF module mechanism, an improved DenseNet121 main network, and a classification prediction module. These components work in synergy to achieve an efficient integration of edge structural information and semantic features. Initially, a portion of the feature maps is processed through the learnable edge detection module, while another portion is passed through the DenseNet main network. The convolutional layers within this main network simulate edge detection capabilities, with the parameters of the convolutional kernels adapting autonomously during training to enhance edge extraction precision in complex scenarios. Subsequently, the edge intensity maps are fused with the primary features via the EAF mechanism, which strengthens the edge perception of the initial features. Channel compression and downsampling are then employed to continuously integrate edge features, reinforcing the structural expression of hierarchical features. The final features are globally averaged and flattened into a one-dimensional tensor, after which Dropout is applied to mitigate overfitting. This tensor is then input into the fully connected layer to complete the classification task.

EAF module

In feature fusion tasks the main features and edge features exhibit strong complementarity. This complementarity is crucial for enhancing the performance of the fusion. However, directly concatenating these two types of features can easily lead to information redundancy, and even result in the suppression of key features, thereby failing to fully exploit the advantages of both. To address this issue, we have designed the EAF (Entropy Attention Fusion) module,As shown in Fig. 3. which utilizes an edge entropy attention mechanism to adaptively enhance key features, thereby achieving efficient and robust feature fusion. Initially, the edge features undergo a Resize operation to adjust their size, aligning them with the subsequent processing or the main feature . Subsequently, they enter the Edge Expanded section, where they are processed and expanded to meet the subsequent fusion requirements. At the same time, the main feature participates in the calculation of entropy, which is one of the core aspects of the EAF module. This entropy calculation can measure the uncertainty and other characteristics contained within the main feature, leading to entropy-related features H1 and H2 associated with the main feature.

Then, the processed edge features and the entropy-related features derived from the main feature are input into the CBAM (Channel-Spatial Weight) module, as shown in Fig. 4. This module learns weights for different channels and spatial positions, which reflect the importance of each channel and spatial location in the fusion process. Finally, utilizing the learned channel-spatial weights, the main feature and edge feature are weighted fused to obtain the final Fusion Feature. Throughout this process, through the entropy attention mechanism, the module can adaptively identify and enhance the features that are critical to the fusion task, suppressing redundant or irrelevant information. This results in the fused features containing both the high-level semantics of the main feature and the detailed contours of the edge features, thereby providing superior feature support for subsequent tasks such as defect detection.

Densenet with EAF

DenseNet consists of two core components: dense blocks and transition layers. The dense blocks define the cascading pattern between input and output, while the transition layers regulate the number of channels to prevent over-saturation. This design significantly reduces computational load without compromising feature extraction capabilities, making network training more efficient. The structural details of these key components are illustrated in Fig. 5.

In DenseNet, each layer is connected to all preceding layers in a feedforward manner, with each layer’s input originating from the outputs of all preceding layers. DenseNet primarily has several architectural configurations, and in this study, we have chosen the DenseNet-121 architecture. We replaced the original model’s three convolutional layers with our three EAF fusion layers, while the rest of the model remains unchanged, maintaining the total number of layers. The EAF module is a lightweight yet highly effective plug-in that injects entropy-weighted cross-feature attention into DenseNet121 with only 0.639 M extra parameters and 10.43 G FLOPs. It selectively amplifies edge-aware defect patterns by computing per-channel Shannon entropy and using it as dynamic attention weights, yielding the entire +2.78 pp accuracy gain while keeping inference at 58.9 FPS (>30 FPS industrial real-time). Meanwhile ,Analysis of the computational overhead introduced by the EAF module and overall model efficiency.(In complexity and computational cost) The edge intensity map and the main feature are enhanced for edge perception through the first EAF fusion (fusion1). Subsequently, EAF fusions (fusion2 and fusion3) are inserted after the transition1 and transition2, respectively, to continuously integrate edge features and reinforce the structural expression of hierarchical features. These features are then input into the fully connected layer to complete the classification. This approach enables more accurate recognition of minor features, as illustrated in Fig. 6.

Learnable edge detection module

Traditional edge detection methods rely on fixed, hand-designed operators (such as Sobel, Canny, etc.), which perform stably when processing images in conventional scenarios. However, they face numerous challenges in the field of industrial inspection. Defects in industrial casting images often exhibit complex and variable characteristics: cracks may extend in arbitrary directions, surface defects like scale may appear with blurred boundaries, and there may also be issues such as uneven illumination and surface texture interference. These factors lead to insufficient generalization of the edge detection results from fixed operators, making it difficult to effectively capture the features of industrial defects. To address this issue, we have designed a learnable edge detection module, as shown in as shown in Fig. 7(a).

This module employs parameterized convolutional layers in place of traditional hand-designed operators, which can adaptively learn edge features of industrial defects through training. It introduces Sobel operator priors to accelerate model convergence. The initial weights are alternately initialized to the x-direction (vertical edges) of the Sobel operator, as shown in Equation 1, and the y-direction (horizontal edges) of the Sobel operator, as shown in Equation 2. This alternating initialization strategy enables the model to be sensitive to multi-directional edges from the early stages of training, effectively covering a variety of possible defect directions and enhancing the correlation between image features. During the forward propagation process, the input image first undergoes conv1 to extract edge features in 8 directions, followed by batch normalization with BatchNorm2D to normalize the feature distribution, which accelerates the training process and stabilizes the feature distribution. Subsequently, a ReLU activation function is applied to introduce non-linearity, enhancing the model’s ability to express complex edges.

To prevent overfitting introduced by the additional edge detection branch, we apply dropout (p = 0.5) before the final classifier and L2 weight decay (\(\lambda = 1 \times 10^{-4}\)) during optimization.The Sobel-initialized learnable edge detector, combined with batch normalization after every convolutional layer, acts as a structured regularizer. This design reduces the train–validation accuracy gap by 4.2%, demonstrating its role as an effective implicit regularizer.

Differentiable entropy module

To accurately capture the local information uncertainty in industrial defect regions, we design a Differentiable Entropy Module, as shown in Fig. 7(b). Its core idea is to quantify the information disorder of local regions in feature maps through the process of local neighborhood extraction, probability distribution conversion, and entropy calculation, providing a basis for subsequent defect feature fusion and recognition. The specific process is as follows:

For the input feature map \(X \in \mathbb {R}^{B \times C \times H \times W}\) (where \(B\) is the batch size, \(C\) is the number of channels, and \(H, W\) are the height and width of the feature map), the entropy module first extracts local neighborhood vectors \(P_{i,j}\) through a sliding window operation (Equation 3). Each vector \(P_{i,j} \in \mathbb {R}^{K^2}\) represents the intensity distribution within a \(K \times K\) region centered at position \((i,j)\). Then, these vectors are converted into probability distributions \(Q_{i,j}\) through a temperature-scaled softmax operation, where the learnable parameter \(\tau\) controls the sharpness of the distribution, as shown in Fig. 3(b). The final entropy value \(E_{i,j}\) (Equation 4) is calculated as the Shannon entropy of \(Q_{i,j}\), which is used to measure the uncertainty of local information. Here, \(\epsilon = 10^{-8}\) is a smoothing term to avoid numerical instability caused by \(Q_{i,j,k} = 0\) in logarithmic operations. A higher entropy value \(E_{i,j}\) indicates that the intensity distribution of the local region is more irregular, and the possibility of defects existing is greater.

Local window extraction:

Entropy calculation:

where \(\epsilon = 10^{-8}\) is a smoothing term to avoid numerical instability caused by \(Q_{i,j,k} = 0\) in logarithmic operations. A higher entropy value \(E_{i,j}\) indicates that the intensity distribution of the local region is more irregular, corresponding to a greater possibility of the existence of defects.

Basic model

The Transition module, as depicted in Fig. 7(c), employs batch normalization and ReLU activation to ensure feature stability. Thereafter, a 1\(\times\)1 convolution is applied to compress the channels to the specified output dimension, followed by a 2\(\times\)2 average pooling to halve the spatial resolution.

Figure 7(d) illustrates the structure of the Bottleneck module23. Initially, the input feature channels are compressed to 4\(\times\)growthrate via a 1\(\times\)1 convolution. After batch normalization and ReLU activation, a 3\(\times\)3 convolution is used to generate new features with a dimension of growthrate channels. Finally, the new features are fused with the original input by concatenating along the channel dimension, thereby achieving feature reuse and growth. The input feature dimensions are denoted as (C, H, W), while the output feature dimensions are (C + growthrate, H, W), with growthrate controlling the rate of feature growth.

Model complexity and computational cost

In order to assess the practical applicability of our method in industrial inspection settings, we have evaluated the computational complexity of both the baseline model and our proposed model under the same input resolution of 224 \(\times\) 224. The baseline DenseNet-121 (adapted for 6-class classification) involves 7.978 M trainable parameters and requires approximately 91.671 G FLOPs per forward pass. In contrast, our proposed EAF-DenseNet-121 increases the parameter count to 8.617 M(+8.01%) and the FLOPs to 102.098 G(+11.37%). The inference speed is 58.9 FPS, compared to 68.2 FPS for the baseline (−13.6%), which remains suitable for real-time industrial inspection.

Although this represents a moderate increase in computational cost, we believe it remains acceptable for real-world industrial visual inspection systems–especially given the observed precision improvement of 2.78% (refer to Ablation experiments). Furthermore, we discuss the trade-off between accuracy and complexity and highlight that the added modules (learnable Sobel-based edge extraction branch and Entropy Attention Fusion module) contribute significantly to feature richness with only a modest additional load.

Experiments and results

Experimental details

Experiments were conducted using Python 3.7 and the PaddlePaddle 2.4.0 deep learning framework. The runtime environment was a Linux system equipped with a Tesla V100 GPU, 32GB of GPU memory, a 4-core CPU, and 32GB of RAM. The Adam optimizer was selected for model parameter optimization, with a learning rate set to 0.001. The number of training epochs was set to 100, and the batch size was configured to 32.

Assessment indicators

In classification tasks, accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score24 are the core metrics used to evaluate the quality of a model’s prediction results. They reflect the model’s performance from different perspectives and are more intuitive than mere loss (LOSS) when focusing on “category prediction accuracy” and “category coverage completeness.” Among them, TP (True Positive) refers to cases where the actual instance is positive and the prediction is also positive (correctly identified)25. FP (False Positive) refers to cases where the actual instance is negative but the prediction is positive (false alarm). TN (True Negative) refers to cases where the actual instance is negative and the prediction is also negative (correctly excluded). FN (False Negative) refers to cases where the actual instance is positive but the prediction is negative (false omission). Their mathematical definitions are as follows: Accuracy: The proportion of global correct predictions (including positive and negative cases), as shown in the following formula.

Through what has been stated above, these metrics can be utilized to specifically analyze experimental results.

Model recognition results

On the simple background dataset NEU-DET, after 100 epochs of training, the model stabilized around the 73rd batch, as shown in Fig. 8(a) with a training loss of approximately 0.045 and an accuracy of about 99% on the validation set. The training progress is illustrated in Fig. 8(b).

This performance is considered excellent. On the complex background dataset GC10-DET, the model achieved effective classification of all categories after 150 epochs of training, with a training loss of about 0.509, as depicted in Fig. 9(a),and the validation accuracy reached about 83%. As shown in Fig. 9(b), this result indicates that the proposed model is suitable for datasets with more complex backgrounds, a larger number of defect categories, and uneven category distribution. This demonstrates the strong adaptability and learning capability of the improved model under these conditions.

In the context of the NEU dataset (confusion matrix as depicted in Fig. 10(a)), the model has demonstrated precise identification of the majority of steel belt defect categories, revealing its robust category differentiation capabilities. However, there are instances of misclassification within category “2,” which is attributed to the insignificant sample features and small intra-class variability of this category, reflecting the impact of sample intrinsic characteristics on the classification outcomes. In the face of the complex defect distribution of the GC-10 dataset (confusion matrix as shown in Fig. 10(b)), the model maintains a high accuracy rate in recognizing the core categories, yet minor errors occur during the cross-classification between categories “3” and “4.” This phenomenon underscores the challenge posed by complex scenarios to the model’s feature differentiation ability, and it also delineates a direction for subsequent model optimization, namely, the need to further enhance the extraction and discrimination of features in easily confused categories.

Under the scenario of the NEU dataset, the 2D visualization of the T-SNE features25 from Fig. 11 reveals that the raw image features (left figure “t-SNE Visualization of Raw Image Features”) are distributed in a scattered and mixed manner, with points from different categories intertwining, indicating that the original features are not conducive to effectively distinguishing between various types of steel defects. In contrast, the features extracted by the model (right figure “t-SNE Visualization of Model Extracted Features”) exhibit a clear clustering trend, with points from different categories relatively concentrated, suggesting that the model is capable of uncovering more discriminative features, effectively enhancing the distinction between different categories of steel defects, and thereby laying the foundation for accurate classification. From Fig. 12, the improved model maintains a satisfactory ability to aggregate under the visualization of T-SNE features, even when faced with the complex defect distribution of the GC-10 dataset and an uneven distribution of categories.

Ablation experiments

To validate the effectiveness of each component within the model, we conducted ablation experiments for each module. These experiments included DenseNet121 without any component, DenseNet121 with Edge, DenseNet121 with EAF, and DenseNet121 with both Edge and EAF. The results are presented in Table 3. Based on the outcomes of the ablation experiments, we observed that the addition of Edge increased the accuracy from 96.39% to 97.52%, while the inclusion of EAF further elevated the accuracy to 97.94%. Simultaneous addition of both Edge and EAF resulted in an accuracy of 99.17%. Each component contributes to enhancing the model’s performance, with the combination of multiple components yielding more significant improvements.

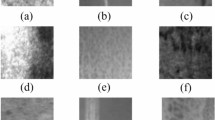

Feature map visualization

The heatmap visualization technique is employed to convert the 64-channel output of the model into a visual heat map. The color distribution of the heat map reflects the response intensity of the model’s weighted parameters in different regions of the image, with darker and brighter colors indicating more significant parameter responses26. As shown in Fig. 13, two sets of experiments are set up for comparison: one for the training phase of the model without the EAF module (referred to as stage a), corresponding to the left part of the heat map in the figure; and another for the training phase after the introduction and optimization of the EAF module (referred to as stage b), corresponding to the right part of the heat map. The experiments cover 6 categories of images, with each category consisting of 6 images in a group, resulting in a total of 6 rows and 6 columns of heat map data.

Without the EAF module (stage a), the heat map (on the left) shows a scattered response of the weighted parameters, distributed across different regions of various image categories, without forming distinct and concentrated feature attention areas. The extraction of image features lacks specificity, as in some images, the parameter responses are chaotic and cover both the internal and edge regions of the image, making it difficult to focus on key information. After the introduction and optimization of the EAF module (stage b), the heat map (on the right) clearly shows that the model’s weighted parameters significantly concentrate on the edge regions of the image. In the heat maps of different categories of images, the edge regions exhibit high response features, with bright and concentrated colors, indicating that the EAF module guides the parameters to more accurately capture the edge features of the images, enhancing the specificity and effectiveness of feature extraction.

To evaluate the performance of the proposed model, 6 types of typical rolling mill defect samples were selected for predictive analysis, as shown in Fig. 14. Corresponding to the original defect images (a), the attention mechanism differences between the baseline model without the Edge Attention Fusion (EAF) module and the model integrated with the EAF module are compared experimentally: the model without the EAF module is prone to focusing on background features (as shown by the heatmap in Fig. (b)), leading to the neglect of key defect information and significant bias in feature extraction; whereas the model combined with the EAF module, its heatmap (c) precisely focuses on the defect regions, enhancing the discriminability of different defect types. Through the visualization comparison of heatmaps, it can be observed that the EAF module can optimize the model’s attention distribution, strengthen the extraction of key defect features, effectively suppress background noise interference, and significantly improve the model’s ability to distinguish defect features under complex scenarios. This provides more reliable feature recognition and classification support for the rolling mill surface defect detection task, demonstrating the application value of the EAF module in industrial visual defect detection.

Comparative experiment

With the advancement of convolutional neural networks, models such as VGG1627, YOLOv1012, and ResNet18 have demonstrated stable performance in various image classification tasks. We conducted comparative experiments using classical models and state-of-the-art (SOTA) models. Experiments were conducted on the NEU dataset, comparing classical models (VGG16, ResNet18), efficient models (EfficientNet-B3, DenseNet121), deep residual models (ResNet-101), and our proposed method (Our work). The comparison results are summarized in Table 4. Classical lightweight models, due to their insufficient network depth and feature expression ability, achieve low scores across the four metrics, making it difficult to distinguish defects from the background. Efficient models, after optimizing feature utilization, see an increase in Accuracy but the F1-score does not exceed 97%, failing to achieve an optimal balance between false positives and false negatives. Deep residual models have overall strong classification capabilities but exhibit biases in subtle scenes. Although the model’s accuracy is 0.05% lower than ResNet50, it improves by 5.92% compared to ResNet18, thus narrowing the performance gap. This result indicates that even with a shallower network structure, the integration of edge enhancement features can still contribute to performance improvement. Our proposed method, through targeted feature enhancement strategies, accurately captures defect details, demonstrating strong consistency between Precision and Recall, and is well-suited to industrial needs. It demonstrates excellent performance, comparable to ResNet-50 in terms of precision under shallow architectures, proving the effectiveness of feature enhancement.

On the challenging GC10-DET dataset with complex backgrounds, all comparative experiments were conducted under identical conditions. As shown in Table 5, our EAF-DenseNet-121 achieves an accuracy of 82.89%, surpassing ResNet18 and YOLOv7 28, but falling 1.32% behind YOLOv10 (84.21%)12. Despite this, our model demonstrates superior precision of 86.57%(vs. 81.32% for YOLOv10), effectively reducing false positives–a key advantage in industrial inspection where misclassification incurs high costs. This result highlights the model’s robustness to noise and complex scenes, suggesting strong potential for cross-dataset generalization and practical deployment in real-world defect classification.

Conclusion

This paper proposes an improved DenseNet121 model that can achieve higher precision predictions for the detection of surface defects on steel strips, meeting the actual application needs of industrial production. During the industrial manufacturing process of steel strips, small defects such as crazing, rolled-in scale, and inclusions are frequently observed. Many fault categories have minor overall defects that are difficult to detect and can impact detection accuracy. Our technology has significantly improved the accuracy of identifying these minor defects.

Firstly, the edge detection module is designed to enhance the model’s ability to identify subtle edge features in feature maps, thereby improving prediction accuracy across various sizes. Secondly, the EAF block based on attention-focused aggregation enhances the backbone network’s feature extraction capabilities, making the model more focused on fine-grained defect feature information, thereby further enhancing its performance in detecting surface defects on steel strips under high inter-class similarities and complex backgrounds. Finally, extensive comparative experiments with advanced models were conducted on the steel strip surface defect detection datasets NEU-DET and GC10-DET to confirm the performance advantages of the proposed model. The experimental results indicate that the method performs well in classifying surface defects on steel strips, achieving high detection accuracy. The proposed model may be useful in industrial production as it can successfully address issues related to complex backgrounds and high inter-class similarities within defects.

Despite the promising performance of the proposed EAF-DenseNet121 model in steel surface defect classification, it still has certain limitations. For instance, while the model’s feature fusion strategy is effective, it may fail to fully capture the fine-grained differences between some highly similar defect categories, leading to occasional misclassifications. Additionally, although the computational cost of the current architecture meets the real-time requirements of industrial scenarios, it can be further optimized for deployment on resource-constrained edge devices. For future work, we plan to explore more advanced attention mechanisms to enhance the discrimination ability between categories. We also intend to investigate lightweight network designs and model compression techniques, such as knowledge distillation, to reduce computational overhead while maintaining classification accuracy, thereby expanding the model’s applicability in various industrial inspection scenarios.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are publicly available. Two steel surface defect detection datasets were utilized: The NEU-DET dataset can be accessed at https://aistudio.baidu.com/projectdetail/9393414. The GC10-DET dataset is available at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/alex000kim/gc10det. These links provide open access to the datasets used for the experiments in this manuscript.

References

Cutler, C. P. Use of Metals in Our Society. In Chen, J. K. & Thyssen, J. P. (eds.) Metal Allergy, 3–16 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2018).

Jinlong, T., Lijie, H. U. O., Yu, X. I. E., Xueyan, Y. & Guopeng, T. U. Cause analysis of black spot defects on coating surface of non-oriented silicon steel. Electrical Steel 3, 25 (2021).

Zongyou, L. I., Chunyan, G. A. O., Xiaoling, L. V. & Minglu, Z. A review of surface defect detection for metal materials based on deep learning. Manuf. Technol. & Mach. Tool 2023, 61–67 (2023).

Xunxun, G. U., Jianping, L. I. U., Jialu, X. & Haiyu, R. E. N. Text Classification: Comprehensive Review of PromptLearning Methods. J. Comput. Eng. & Appl. 60, 23–25 (2024).

Zhang, R., Li, W. & Mo, T. Review of Deep Learning. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1804.01653 (2018).

Hu, D., Lyu, B., Wang, J. & Gao, X. Study on HOG-SVM detection method of weld surface defects using laser visual sensing. Transactions China Weld. Inst. 44, 57–62 (2023).

Alloghani, M., Al-Jumeily, D., Mustafina, J., Hussain, A. & Aljaaf, A. J. A Systematic Review on Supervised and Unsupervised Machine Learning Algorithms for Data Science. In Berry, M. W., Mohamed, A. & Yap, B. W. (eds.) Supervised and Unsupervised Learning for Data Science, 3–21 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2020).

Roweis, S. EM algorithms for PCA and SPCA. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 10, 7–8 (1997).

Alom, M. Z. et al. The History Began from AlexNet: A Comprehensive Survey on Deep Learning Approaches. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1803.01164 (2018).

Zhao, Q. et al. A review of deep learning methods for the detection and classification of pulmonary nodules. Sheng wu yi xue gong cheng xue za zhi= Journal of biomedical engineering= Shengwu yixue gongchengxue zazhi 36, 1060–1068 (2019).

Yuan, Z., Ning, H., Tang, X. & Yang, Z. GDCP-YOLO: Enhancing Steel Surface Defect Detection Using Lightweight Machine Learning Approach. ELECTRONICS 13, 1388. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13071388 (2024).

Xie, H., Zhou, H., Chen, R. & Wang, B. SDMS-YOLOv10: improved Yolov10-based algorithm for identifying steel surface flaws. Nondestruct. Test. Eval. 2025, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10589759.2025.2474103 (2025).

Wenqi, Y. U. et al. MAR20: A benchmark for military aircraft recognition in remote sensing images. Natl. Remote. Sens.Bull. 27, 2688–2696 (2024).

Xia, X., Wen, M., Zhan, S., He, J. & Chen, W. An increased neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio is an early warning signal of severe COVID-19. Nan fang yi ke da xue xue bao= Journal of Southern Medical University 40, 333–336 (2020).

Kulkarni, S. & Khaparde, S. Transformer Engineering: Design, Technology, and Diagnostics (CRC Press, 2017), 2 edn.

Xu, X. et al. Real-Time Belt Deviation Detection Method Based on Depth Edge Feature and Gradient Constraint. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland) 23, 8208. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23198208 (2023).

Wang, J.-B. & Ji, Y.-B. Image edge-detection based on mathematical morphology of multi-structure element algorithm. J.Liaoning Univ. Petroleum & Chem. Technol. 26, 79 (2006).

Liu, J.-W., Liu, J.-W. & Luo, X.-L. Research progress in attention mechanism in deep learning. Chin. J. Eng. 43, 1499–1511 (2021).

Liang, M., Yutao, G., Tao, L. E. I., Lei, J. & Yixuan, S. Small object detection based on multi-scale feature fusion using remote sensing images. Opto-Electronic Eng. 49, 210363–1 (2025).

Ferrández, R. M., Terol, Muñoz, R., Martínez-Barco, P. & Palomar, M. Deep vs. Shallow Semantic Analysis Applied to Textual Entailment Recognition. In Advances in Natural Language Processing (eds Hutchison, D. et al.) vol. 4139, 225–236 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2006).

Bao, Y. et al. Triplet-graph reasoning network for few-shot metal generic surface defect segmentation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 70, 1–11 (2021).

Lv, X., Duan, F., Jiang, J.-J., Fu, X. & Gan, L. Deep metallic surface defect detection: The new benchmark and detection network. Sensors 20, 1562 (2020).

Yan, Y., Liu, J. & Zhang, J. Evaluation method and model analysis for productivity of cultivated land. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 30, 204–210 (2014).

Jonckheere, S. et al. Evaluation of different confirmatory algorithms using seven treponemal tests on Architect Syphilis TP-positive/RPR-negative sera. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 34, 2041–2048. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-015-2449-z (2015).

Platzer, A. Visualization of SNPs with t-SNE. PLoS ONE 8, e56883. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056883 (2013).

Antoniou, I. E. & Tsompa, E. T. Statistical Analysis of Weighted Networks. Discrete Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2008, 375452. https://doi.org/10.1155/2008/375452 (2008).

Lv, X., Duan, F., Jiang, J.-J., Fu, X. & Gan, L. Deep metallic surface defect detection: The new benchmark and detection network. Sensors 20, 1562 (2020).

Song, H. RSTD-YOLOv7: a steel surface defect detection based on improved YOLOv7. Sci. Rep. 15, 19649 (2025).

Funding

This work was supported by the Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2025TSGCCZZB0083) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. U24A20277).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors contributed extensively to the manuscript. Y.W. contributed to study design, software experiments and manuscript drafting. Z.L. and G.D. provided scientific guidance and modification suggestions. Y.L. and F.Z contributed to the data analysis, proofreading, and editing of the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Lu, Y., Zhu, F. et al. High precision classification of hot rolled strip steel surface defects using dual path features and entropy attention fusion. Sci Rep 16, 5351 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31683-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31683-x