Abstract

At present, urban greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from different wastewater treatment stages are attracting increasing attention. Based on the Guidelines of the China Greenhouse Gas List Compilation (Trial) and the IPCC National Greenhouse Gas List Guidelines in 2006, this paper evaluated urban GHG emissions from wastewater treatment in China from 2011 to 2020. The contribution rates of GHG emissions to the total GHG emissions were calculated for the different wastewater treatment stages. The variations in annual GHG emissions and differences in GHG emissions among different regions and provinces were also analyzed. The total amount of equivalent CO2 emissions reaches 1478.51 million tons, and the annual average amount of equivalent CO2 emissions from 2011 to 2020 is 147.9 million tons, which shows a trend of decreasing first and then increasing. The distribution of GHG emissions from wastewater treatment is uneven among provinces and regions; Guangdong Province has the highest emission, while the Xizang autonomous Region has the lowest. The correlation and contribution rate analysis revealed that paper production and chemical and side food production could discharge a large amount of wastewater with a high COD content, which may have an important impact on GHG emissions during the wastewater treatment stages. According to the study results, CH4 accounts for the largest proportion (63.08%) of the total GHG emissions. The most important source of CH4 comes from the industrial wastewater treatment stage. The annual average CO2 emissions account for 22.24% of the total GHG emissions, which are mainly from the power and chemical consumption stage. The annual average N2O emissions account for 14.68% of the total GHG emissions and are mainly from the wastewater collection and discharge stage. Therefore, in the future, GHG emission reduction strategies should focus on CH4 emissions in the industrial wastewater treatment stage and develop CH4 recycling and utilization technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the greenhouse effect has led to global warming, sea level rise, and frequent natural disasters such as extreme climate and forest fires. The main greenhouse gases (GHG) that cause greenhouse effects are carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O). To mitigate the impact of global warming, many countries around the world have launched active actions1,2. At the 75th session of the United Nations General Assembly, China proposed the goal of achieving a carbon emission peak by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 20603.

During recent years, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (MOHURD) jointly issued series of documents on promoting the synergy of pollution reduction and carbon emission reduction in sewage treatment4,5. GHG emissions from urban wastewater treatment are among the most important sources6. In the process of wastewater collection, treatment and discharge, carbon and nitrogen in wastewater can generate GHG such as CH4, N2O and CO2 due to microorganism action. With the development of economic construction and urbanization, the number of wastewater treatment plants is increasing. By the end of 2020, 2,618 wastewater treatment plants had been put into operation in China, with wastewater treatment capacity of 55.7 billion tons and a 97.53% treatment rate.

Therefore, it is highly important to carry out urban GHG emission evaluations and obtain GHG emission data at different wastewater treatment stages to formulate relevant national energy conservation and emission reduction policies.

The National Greenhouse Gas Inventories (IPCC) is a current international GHG accounting method that enjoys high authority in the field of global GHG emission analysis and calculation7. At present, many scholars worldwide have studied urban GHG emissions by using IPCC guidelines and achieved desirable results. In 2023, Yongmu Li et al. studied the carbon accounting of the C2O process based on the carbon footprint in a full-scale municipal wastewater treatment plant8. In 2022, Yi-Ming Wei et al. studied the policy and management of carbon peaking and carbon neutrality9. The authors considered that there is a research gap in the literature in terms of studies that systematically identify opportunities to achieve carbon neutrality. In 2020, Monserrat et al. analyzed empirical methods for the quantification of N2O emissions in wastewater treatment plants10. In 2018, Yan Xu et al. calculated the GHG emissions of China’s urban sewage treatment plants in 2014 according to the method provided by the IPCC11. Unfortunately, data from only one year cannot represent the general trend.

In 2023, Du Wenjie et al. evaluated the greenhouse gas emission characteristics of the sewage industry and studied future emission reduction potential technical paths based on big data analysis of the operation and carbon emissions of municipal sewage treatment facilities from 2009–201912. The results showed that different sewage quality characteristics and sewage plant operations are the main reasons for the regional differences in discharge intensity. In 2023, Yang Mengjie et al. used the population equivalent method to calculate GHG emissions in China’s municipal sewage treatment plants from 2005 to 2020 and analyzed the characteristics of historical emission variation13. The results showed that greenhouse gas emissions from China’s municipal sewage treatment plants increased by 232% in 2020 compared with those in 2005. The increase in greenhouse gas emissions can be attributed to rapid urbanization, improved living standards and a large increase in wastewater treatment capacity. In 2023, Shaoqing Chen et al.(2023) examined the nexus of urban water stress and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions resulting from expanding wastewater infrastructures across over 300 cities in China14. Qu, S. et al. (2024) carried out study on carbon footprint drivers in China’s municipal wastewater treatment plants. In this study, GHG emissions are systematically accounted for, and the driving factors of carbon footprint growth in China ' s MWWTPs are explored15.

As mentioned above, although some scholars worldwide have studied the carbon emissions of sewage treatment, they have focused mostly on the final (or total) carbon emissions from wastewater treatment, which lacks GHG emissions at different stages from wastewater collection to treatment and discharge. In addition, there are still few studies on GHG regional distributions; GHG classification (such as CH4, N2O and CO2); and important influencing factors on GHG emissions and relevant classified GHG reduction strategies in China.

Therefore, based on the Guidelines for the Compilation of the Provincial GHG Inventory (Trial) of China16 and the Guidelines for National GHG List of the IPCC in 20067, this paper calculated GHG emissions from different wastewater treatment stages in China from 2011 to 2020, analyzed the GHG contribution rate in the different wastewater treatment stages, and compared the main reasons for annual GHG variation in the different provinces. The paper may have the following novelties compared with the previous works: •Applying life cycle assessment (LCA) to comprehensively evaluate greenhouse gas emissions throughout the entire life cycle of urban wastewater treatment, from raw water intake to sludge disposal. This is more comprehensive than traditional methods that only focus on the treatment process itself. •Using dynamic methods to calculate and reveal the change law of greenhouse gas emissions under different operating conditions and influent water quality. This can help optimize the operation of the treatment plant and reduce emissions. •Integrating data from multiple sources, such as monitoring data of treatment plants, and urban economic and social data, to more accurately evaluate greenhouse gas emissions. • The study covers all of the provinces (regions) of China, which can visually display the emission status of different regions and their impact on the surrounding environment, and is conducive to formulating regional emission reduction strategies. •In addition to the traditional carbon dioxide, more attention is paid to the evaluation of other greenhouse gases such as methane CH4 and nitrous oxide N2O in the process of urban wastewater treatment. The study results can support important references for formulating relevant national wastewater treatment planning, energy conservation and emission reduction strategies.

Methods and materials

Evaluation scope and methods

In this paper, we combined both the China GHG List Compilation Guidelines and 2006 IPCC Guidelines to strengthen the credibility (such as clear alignment and priority of guidelines, emission factor selection and justification, boundary and scope definition, etc.).

Evaluation scope

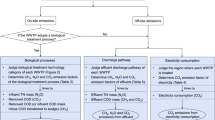

Both direct and indirect GHG emissions could be generated during the different stages of wastewater collection, treatment and drainage. Based on the main wastewater treatment technologies in China, a schematic diagram of GHG emissions during the process of wastewater treatment was constructed (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 shows that wastewater first flows into collection pipelines and then flows to wastewater treatment plants. In this stage, direct CH4 and N2O could be generated. After the wastewater flows into the plant, the suspended pollutants in the wastewater are first removed during the first treatment. Then, the activated sludge method and biological treatment method are used to remove most of the organics, nitrogen and phosphorus. In this phase, direct GHG could be generated. Moreover, indirect GHG could also be generated from power use and chemical product consumption. To achieve higher effluent standards, some wastewater treatment plants adopt advanced treatment systems to remove nitrogen and phosphorus from wastewater.

When the water quality reaches the required standard, the treated wastewater is discharged into the surface water, and direct GHG emissions can be generated during this stage17.

To simplify the calculation, we divided wastewater treatment into four stages; wastewater collection and discharge, domestic wastewater treatment, industrial wastewater treatment, and power and chemical product consumption. Direct GHG (CO2, CH4 and N2O) could be generated in the first 3 stages, and indirect GHG (CO2) could be generated in the power and chemical product consumption stage. Because most wastewater treatment plants have a service life of 30~50 a, GHG emissions during the construction process are low and can be neglected18. Moreover, the IPCC defines CO2 generated by biodecomposition as biogenic CO2, which is not included in the GHG calculation list. According to the IPCC guidelines, the direct emissions of N2O in the wastewater treatment stage are low and can also be neglected19.

For convenient comparison, in this paper, we converted CH4 and N2O emissions to carbon emission equivalents (CO2-eq.). The warming capacities of 1 ton of CH4 and 1 ton of N2O are equivalent to 25 tons and 298 tons of CO2, respectively. The scope of GHG emissions accounting in this study is shown in Table 1.

The evaluation methods of GHG emissions in the different wastewater treatment stages

The methods for calculating different components of GHGs based on IPCC

The IPCC provided methods and equations for calculating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs). The main GHGs from WWTPs are methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O) and carbon dioxide (CO2). The followings are the calculation methods based on IPCC equations:

-

(1)

(CH4) Emissions.

The first-order kinetic model to calculate methane emissions from anaerobic treatment processes in wastewater treatment plants is used. The basic formula is;

where QCH4 is the methane production rate (m3/d), k is the first-order kinetic constant (d-1), V is the volume of the anaerobic reactor (m3), S0 and S are the influent and effluent substrate concentrations (kg/m3) respectively, and θ is the hydraulic retention time (d).

In actual situations, factors such as temperature and the type of substrate need to be considered. The formula is adjusted as follows:

where k(T) is the temperature-corrected first-order kinetic constant, and fsubstrate is the correction factor for the type of substrate.

-

(2)

Nitrous Oxide (N2O) Emissions

$$\:{E}_{{N}_{2}O}={N}_{in}\times\:EF\times\:\frac{44}{28}$$(3)where \(\:{E}_{{N}_{2}O}\) is the nitrous oxide emission amount (kgN2O-N/d), \(\:{N}_{in}\) is the total nitrogen input amount (kgN/d), EF is the emission factor, and \(\:\frac{44}{28}\) is the conversion factor from nitrogen to nitrous oxide.

-

(3)

Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Emissions

$$\:{Q}_{C{O}_{2}}=r\times\:V\times\:X\times\:Y$$(4)where \(\:{Q}_{C{O}_{2}}\) is the carbon dioxide production rate (kgCO2/d), r is the specific oxygen uptake rate (kgO2/MLSS.d), V is the volume of the aeration tank (m3), X is the mixed liquor suspended solids concentration (kgMLSS/d), and Y is the conversion factor from oxygen consumption to carbon dioxide production.

The specific oxygen uptake rate refers to the amount of oxygen consumed per unit mass of mixed liquor suspended solids (MLSS) in a unit of time. It is used to quantitatively describe the rate at which microorganisms in the activated sludge system take up and utilize oxygen during the biochemical reaction process.

Indirect carbon dioxide emissions mainly come from the consumption of electricity and chemicals in the operation of the wastewater treatment plant. The calculation formula is:

where ECO2,indirect is the total indirect carbon dioxide emissions (kgCO2), Ei is the consumption of the i-th energy or material ( kWh or kg), and EFi is the corresponding carbon emission factor.

The dynamic structure models for the different components of GHGs

where E refers to the annual total CO2 − eq. emissions, kg/a; \(\:{\text{E}}_{\text{d}(\text{C}{\text{O}}_{2}-\text{e}\text{q})}\) refers to the annual CO2 − eq. direct emissions, kg/a; and \(\:{\text{E}}_{\text{i}\text{n}\text{d}(\text{C}{\text{O}}_{2}-\text{e}\text{q}.)}\) refers to the annual CO2 − eq. indirect emissions, kg/a.

where \(\:{\text{E}}_{\text{p}\text{o}\text{w}\text{e}\text{r}}\) refers to the total CO2-eq. emissions indirectly generated by power consumption, kg/a; \(\:{\text{E}}_{\text{c}\text{h}\text{e}\text{m}\text{i}\text{c}\text{a}\text{l}\:\text{p}\text{r}\text{o}\text{d}\text{u}\text{c}\text{t}\text{s}}\) refers to the total amount of CO2-eq. emissions indirectly generated by chemical consumption, kg/a; \(\:{\text{E}}_{\text{p}\text{o}\text{w}\text{e}\text{r}-\text{w}\text{t}}\) refers to the CO2-eq. emissions indirectly generated by power consumption in the domestic and industrial wastewater treatment stages, kg/a; \(\:{\text{F}}_{\text{E}}\) refer to the wastewater discharge factor of China’s regional power grid baseline20; \(\:{\text{T}}_{\text{C}\text{O}\text{D}}\) refers to the annual COD reduction in wastewater, tons/a; \(\:{\text{U}}_{\text{p}\text{o}\text{w}\text{e}\text{r}-\text{C}\text{O}\text{D}}\) refers to the power consumption to reduce 1 ton of COD in wastewater, kW·h/t; and 0.02 refers to the proportion of the CO2-eq. emissions generated by chemical product consumption to the total CO2-eq. emissions from wastewater treatment21.

where \(\:{\text{E}}_{{\text{d}(\text{C}\text{H}}_{4})}\) refers to the annual direct CH4 emissions in the whole stage of wastewater treatment, kg/a; \(\:{\text{E}}_{{\text{d}(\text{N}}_{2}\text{O})}\) refers to the annual direct N2O emissions in the whole stage of wastewater treatment, kg/a; \(\:{\text{E}}_{\text{d}\left(\text{C}{\text{H}}_{4}\right)}\) refers to the annual direct CH4 emissions in wastewater treatment, kg/a; \(\:{\text{E}}_{\text{d}\left(\text{C}{\text{H}}_{4}\right)\text{W}.\text{C}}\) refers to the annual direct CH4 emissions in the wastewater collection stage, kg/a; \(\:{\text{E}}_{\text{d}\left(\text{C}{\text{H}}_{4}\right)\text{W},\text{D}}\) refers to the annual direct CH4 emissions in the wastewater discharge stage, kg/a; and \(\:{\text{E}}_{\text{d}\left(\text{C}{\text{H}}_{4}\right)\text{W}.\text{T}}\) refers to the annual CH4 emissions from domestic and industrial wastewater treatment, kg/a.

where \(\:{\text{E}}_{\text{W}.\text{T}}\:\)refers to the annual CH4 emissions from domestic and industrial wastewater treatment stage, kg/a; \(\:{\text{E}}_{\text{d}\text{o}\text{m}\text{e}\text{s}\text{t}\text{i}\text{c}}\) refers to the annual CH4 emissions from domestic sewage treatment stage, kg/a;\(\:{\text{E}}_{\text{i}\text{n}\text{d}\text{u}\text{s}\text{t}\text{r}\text{y}}\) refers to the annual CH4 emissions from industry sewage treatment, kg/a༛TOW is the total amount of BOD in domestic wastewater, kg; EF refers to the discharge factor from wastewater treatment; R refers to the annual CH4 recovery, kg/a. In the formula (13), the discharge factor (EF) can be calculated by using formula (14).

where \(\:{\text{B}}_{\text{m}\text{a}\text{x}.\text{C}{\text{H}}_{4}}\) refers to the maximum CH4 production capacity, tons; \(\:\text{M}\text{C}\text{F}\) refers to the CH4 verification factor; and the average MCF in China is 0.16522.

where \(\:{\text{E}}_{\text{i}\text{n}\text{d}\text{u}\text{s}\text{t}\text{r}\text{y}}\) refers to the annual CH4 emissions from industrial wastewater treatment (kg/a), \(\:\text{T}\text{O}{\text{W}}_{\text{i}}\) refers to the total amount of BOD in the ith industrial wastewater (kg/a), \(\:{\text{S}}_{\text{i}}\) refers to the total amount of COD removed by sludge mode (kg/a), \(\:\text{E}{\text{F}}_{\text{i}}\) is the emission factor23, and \(\:{\text{R}}_{\text{i}}\) refers to the amount of CH4 recovery (kg/a).

The N content discharged into the wastewater is

where \(\:{N}_{E}\) refers to the N content discharged into the wastewater, kg/a; P refers to the total population; \(\:{P}_{r}\) refers to the protein consumption per capita; and \(\:{F}_{NPR}\) refers to the N content in the protein, kg. N/kg; \(\:{F}_{NON-CON}\) refers to non-consuming protein factors in wastewater; \(\:{F}_{IDN-COM}\) refers to industrial and commercial protein emission factors; and \(\:{N}_{S}\) refers to the N content reduction during sludge treatment, kg/a.

where i refers to the different kinds of foods; \(\:{Q}_{i}\) refers to average food consumption per capita, kg/(person·a); and \(\:{C}_{i}\) refers to the protein content in the food products.

Correlation analysis methods among GHG emissions and relevant factors

The correlation coefficient of key industrial production and wastewater treatment was analyzed by using the Pearson correlation analysis method, as shown in formula (18).

where r is the correlation coefficient; \(\:\text{X}\)i is the ith GHG emission; \(\:{\text{Y}}_{\text{i}}\:\)is the relevant factor affecting GHG emission; \(\:\stackrel{-}{{\text{X}}_{\text{i}}},\:\stackrel{-}{{\text{Y}}_{\text{i}}}\:\)is the mean of the Xi, Yi series; and n is the number of calculated series. The larger the r is, the closer the correlation between the indicators is. When r \(\:\ge\:\)0.8, there is a significant correlation between the indicators.

Data sources

The relevant data and criteria used in this study were derived from the latest officially published information (Table 2).

The regional differentiation (e.g., industrial structure, treatment technology types) was factored into the calculations through considering industrial structure differences, considering treatment technology types differences, etc.

Analysis of GHG emissions from urban wastewater treatment in China

CO2-eq emissions from urban wastewater treatment

The calculated results of CO2-eq emissions from urban wastewater treatment in China from 2011 to 2020 are shown in Table 3; Fig. 2.

The total CO2 − eq emissions generated by urban wastewater treatment in China from 2011 to 2020 can be seen in Table 3; Fig. 2, which show a trend of decreasing first and then increasing. The lowest CO2 − eq emissions (133.1 million tons) were found in 2018, and the highest CO2 − eq emissions (171.94 million tons) were found in 2011. The initial decline reflected coordinated decarbonization efforts, while the subsequent increase highlighted economic priorities and climate goals.

The CO2-eq emissions per capita exhibited the same trend, with the lowest occurring in 2018 (94.81 kg per capita) and the highest occurring in 2011 (110.92 kg/per capita).

Table 2 shows that eastern regions, such as Guangdong, Shandong, Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces have higher CO2-eq emissions, while western provinces, especially Tibet, have lower CO2-eq emissions.

The annual average CO2-eq emissions in Guangdong Province total approximately 17 million tons, accounting for 11.5% of the country’s total CO2-eq emissions from urban sewage treatment, ranking first in the country. The annual average CO2-eq emissions in Shandong Province total approximately 15 million tons, accounting for 10.1% of the total CO2-eq emissions from urban sewage treatment, ranking second in the country. The annual average CO2-eq emissions from urban wastewater treatment in Jiangsu Province account for 9.3% of the total CO2-eq emissions in the country; those in Zhejiang account for 8.4%, those in Henan account for 4.8% and those in Sichuan account for 3.5%. Gansu, Hainan, Ningxia, Qinghai and Tibet are the five provinces with the lowest CO2-eq emissions, accounting for 1.4%, 1.15%, 0.8%, 0.38% and 0.19%, respectively, of the country’s total CO2-eq emissions from wastewater treatment.

Analysis of GHG emissions in the different urban wastewater treatment stages

General characteristics

The contribution rate (i.e., the ratio of GHG emissions in the different stages to the total GHG emissions) was calculated for each province, and the results are shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3 shows that the contribution rates of GHG emissions during the different stages of urban wastewater treatment differ among the different provinces. For different wastewater discharge levels, a higher GHG emission contribution rate occurred in the direct wastewater discharge stage in Tibet, Guangxi and Jiangxi Provinces, which may be due to the lower wastewater collection rate and lower wastewater treatment rate. For different wastewater treatment stages, a higher GHG emission contribution rate can be observed in the industrial wastewater treatment stage in Zhejiang, Jiangsu and Fujian provinces, which may be due to the greater degree of industrialization.

Correlation analysis of GHG emissions

(1) Justification of the correlation between greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and industrial sectors.

Justifying the correlation between greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in key industrial sectors and wastewater treatment involves several aspects, such as Industrial growth and wastewater treatment expansion, supply-chain effects, policy-driven correlations, etc.

As key industrial sectors grow, the volume of industrial wastewater also increases. This necessitates the expansion or construction of new wastewater treatment facilities. The construction and operation of these additional facilities require energy and materials, both of which are associated with GHG emissions.

Government policies aimed at reducing industrial pollution often require industries to improve their wastewater treatment. In some cases, industries may invest in more efficient wastewater treatment technologies to meet regulatory requirements. These new technologies may have different energy consumption patterns and GHG emission profiles. For example, if a government enforces stricter environmental regulations on the leather-tanning industry, the industry may adopt cleaner production technologies and more advanced wastewater treatment methods. These changes can either increase or decrease GHG emissions depending on the nature of the new technologies, thus creating a correlation between industrial policies, wastewater treatment, and GHG emissions.

(2) The correlation of GHG emissions between key industrial sectors and wastewater treatment.

The correlation coefficient of GHG emissions between key industrial production and wastewater treatment were analyzed by using the Pearson correlation analysis method (Table 4).

Table 4 shows that the production of paper, chemical products and side food industries is significantly and positively correlated with GHG emissions in the wastewater treatment stage.

(3) Correlation analysis of GHG emissions in the domestic wastewater treatment stage.

From 2011 to 2020, GHG emissions from domestic wastewater treatment steadily increased from 20.72 million tons in 2011 to 26.5 million tons in 2020. Table 5 shows that the wastewater treatment rate, capacity, population and urbanization are significantly positively correlated with domestic wastewater treatment and wastewater collection and discharge.

With the continuous growth of the population and urbanization rate, wastewater discharge continues to increase, and GHG emissions from domestic wastewater treatment also increase.

There are great differences in GHG emissions from domestic wastewater discharge and treatment stages in different provinces; Guangdong, Shandong, Jiangsu, Henan and Sichuan are the five provinces with the highest GHG emissions in the domestic wastewater discharge and treatment stage, and Tibet, Qinghai and Ningxia have the lowest GHG emissions in these two stages. The main reasons may be the large population, high urbanization rate, high wastewater treatment capacity and high GHG emissions in the eastern region, while Tibet, Qinghai and other provinces have a small population, low wastewater treatment capacity and low GHG emissions.

(4) GHG emissions in the wastewater collection and discharge stage.

From 2011 to 2020, GHG emissions during the stage of wastewater collection and discharge showed a decreasing and increasing trend, decreasing from 45.6 million tons in 2011 to 23.74 million tons in 2016 and then increasing to 25.47 million tons in 2020. GHG emissions during the wastewater collection and discharge stages are mainly CH4 and N2O. The analysis revealed that during these stages, GHG emissions are related mainly to the length of pipeline construction.

The correlation analysis revealed that the CH4 concentration in the collection and discharge stage was negatively correlated with the length of the pipeline and the wastewater treatment rate (Table 6). There could be several possible reasons for the negative relationship. The main affected factors include physical and chemical processes, dilution effect, biological activities etc., during the collection and discharge process.

In contrast to those of CH4, the N2O emissions show an overall increasing trend. According to formula (15), N2O emissions were significantly and positively correlated with total household protein intake. The higher the total protein intake is, the more nitrogen is present in the wastewater, and the more N2O can be produced. Therefore, improvements in resident dietary habits can affect N2O emissions.

Some provinces (such as Hunan, Gansu, Xinjiang and Tibet) had the highest GHG emissions in the collection and discharge stages, which may be related to inadequate pipeline construction and high protein consumption (such as population and dietary consumption habits).

(5) GHG emissions in the power and chemical product consumption stage.

From 2011 to 2020, GHG emissions in the power and chemical consumption stage showed a trend of decreasing, increasing and then decreasing. The Pearson correlation analysis revealed that there was a significant positive correlation between GHG emissions from power and chemical consumption and between COD discharged from domestic and industrial wastewater treatment (Table 7).

The average CH4, N2O and CO2 emissions in the wastewater treatment stages

The contribution rates of CH4, N2O and CO2 during the different stages from wastewater collection to treatment were analyzed (Fig. 4(a)).

From 2011 to 2020, the annual average CH4 emissions were the highest and had the largest contribution (63.08%) among the three major greenhouse gases, which was equivalent to approximately 93.3 million tons of CO2-eq emissions. The annual average N2O emissions are approximately equivalent to 21.71 million tons of CO2-eq emissions, accounting for 14.68% of the total GHG emissions, which are mainly from the wastewater collection and discharge stages. The The analysis results (see Fig. 4 (b)) reveal that CH4 is produced during all wastewater treatment processes, including industrial and domestic wastewater treatment, as well as during wastewater collection and discharge. The CH4 contribution rate ranks the largest among the three major GHG elements; therefore, reducing GHG emissions is a future focus.

The composition of industrial wastewater is complex and includes, for example, paper production, chemical products (chemical pesticides, chemical fibers, synthetic detergents, chemical drugs), side food production (such as sugar, edible vegetable oil, canned food) and other industries. Additionally, wastewater contains large amounts of organics, which can generate a large amount of CH4 during anaerobic treatment.

Figure 4(b) shows that the CH4 contribution rate from industrial wastewater treatment is 68.43%. Organic and oil waste substances in domestic wastewater are also rich in a large amount of organic carbon and can also generate a large amount of CH4 (with a contribution rate of 27.15%) during the process of anaerobic treatment. According to the statistics, the COD production of domestic wastewater in 2015 was approximately 16.37 million tons. In addition, CH4 can also be generated under anaerobic conditions during wastewater collection and discharge, but the CH4 contribution rate (only 4.42%) is far less than that in industrial and domestic wastewater treatment processes.

Although the greenhouse effect of CO2 is much less than that of CH4 (approximately 1/25 of CH4), because a wastewater treatment plant consumes a large amount of energy, a large amount of CO2 could be generated during the power and chemical product consumption stages. For example, wastewater treatment power consumption was approximately 19.2 billion kW.h in China in 2018. Therefore, CO2 can also make an important contribution to GHG emissions throughout the wastewater treatment process.

The contribution of N2O to GHG emissions is lower than that of CH4 and CO2, but its greenhouse effect capacity is 298 times that of CO2; hence, N2O emission control cannot be ignored. N2O is generated mainly from nitrogen nitrification and denitrification during the process of wastewater collection and discharge.

Discussions

GHG emissions at different wastewater treatment stages

Different study results indicate that GHG emissions vary at different stages of wastewater treatment. In the United States, a large amount of methane leaks through the gaps in digestion tanks and pipeline interfaces during the anaerobic digestion process, which is the main source of emissions. In China, some researchers sampled and analyzed each structure of a wastewater treatment plant in Nanjing and found that the oxidation ditch, anaerobic zone, rotating grit chamber, secondary sedimentation tank, and anoxic zone were the main methane-releasing structures.

According to the study results in this paper, industrial wastewater treatment is the wastewater treatment stage with the largest contribution to total GHG emissions. Regions with high industrial wastewater treatment capacity, such as Guangdong and Shandong provinces, have high GHG emissions in the power and chemical product consumption stages. Therefore, optimizing the industrial structure and reducing the pollutants produced by the industrial wastewater treatment stage in such regions are the focus of future GHG emission reduction strategies.

GHG emission variation in the industrial wastewater treatment stage may be an important factor causing total GHG emission differences among different years and different provinces. In addition, the GHG emissions from the power and chemical products stage are closely related to those from the industrial wastewater treatment stage. Therefore, reducing GHG emissions during the industrial wastewater treatment stage is a focus of future GHG emission reduction strategies, especially in eastern provinces with high economic development. Due to the large population, high urbanization rate, high industrial level and large load of industrial wastewater treatment, GHG emissions are high in each wastewater treatment stage in the eastern provinces.

Paper production, chemical products (such as chemical pesticides, chemical fibers, synthetic detergents, chemical drugs), side foods (such as sugar, edible vegetable oil, and canned food) and other production sectors could drain wastewater with high COD content in the production process25, which has a significant impact on GHG emissions.

The main impact factors on CH4, CO2, and N2O emissions and mitigation of impact factors for reducing GHG during wastewater collection and discharge stage

The present study discovered that the different factors would impact the components of GHG during wastewater collection and discharge stage. The impact factors on CH4 emissions include organic matter concentration, temperature, hydraulic retention time. The impact factors on CO2 Emissions include energy consumption, biological activity. The impact factors on N2O emissions include nitrogen content in wastewater, pH and Oxygen conditions. The mitigation of impact factors for reducing GHG emissions include reducing organic matter load, temperature control, optimizing hydraulic retention time, energy efficiency improvements, managing biological activity, etc.

In wastewater treatment process, these impact factors interact in complex ways. For example, a change in the organic matter concentration can affect the energy consumption and biological activity, which in turn can impact the CO2 emissions. The design of the wastewater treatment process needs to consider these interactions. Therefore, a holistic approach is needed to optimize the treatment process to minimize all three types of greenhouse gas emissions.

Reduction strategies for GHG emissions (CH4, CO2, N2O)

Implementing greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction strategies—targeting CO2, CH4, and N2O—faces complex, interconnected challenges spanning economics, technology, policy, and behavior.

To control GHG emissions, we recommend optimizing wastewater treatment technologies during the industrial and domestic wastewater treatment stages.

In traditional wastewater treatment technology (such as A2/O), a large amount of carbon must often be added, which increases the input of carbon sources26. Therefore, optimizing the technology of wastewater treatment plants or using low CO2 emission agents is an effective strategy for controlling CO2 emissions. For instance, rationally using CH4 generated during the wastewater treatment stage is an important method for effectively controlling CO2 emissions.

Recent studies have shown that CH4 can be used as a carbon source and electron donor to drive the denitrification process to remove nitrate and other pollutants in wastewater, which provides a new idea for recycling carbon sources in wastewater treatment. The anammox process has been a new auto-growth denitrification skill in recent years. In the anammox process, special functional microorganisms can remove ammonia nitrogen, nitrite nitrogen and other nitrogen without additional carbon sources, which can result in the advantages of low sludge production and low energy consumption27.

For CH4 emission control in the wastewater collection and discharge stage, we found that CH4 emissions are significantly negatively correlated with the length of pipeline networks; hence, the construction of a wastewater pipeline network should be further improved in the future to realize the objective of CH4 emission reduction.

Implementing GHG reduction strategies requires addressing interconnected challenges with “systemic, equitable solutions”—combining policy certainty, technological innovation, financial support, and inclusive engagement. No single approach will suffice, success depends on aligning short-term needs (e.g., energy affordability, job creation) with long-term climate goals. By prioritizing collaboration across governments, businesses, communities, and international bodies, the global community can accelerate the transition to a low-carbon future.

Comparison of the study results with the previous findings

Comparison of the study results with the previous findings would include emission quantity and trend, Emission composition (CH4 and N2O), and regional distribution characteristics.

Comparing with the previous studies on the similar topics, some similarities, specific findings, and differences could be found. The similarities mainly include methodological basis and research focus. Many studies likely share common methods for measuring and estimating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from wastewater treatment plants.

The specific findings in this paper include specific data insights, influence of regional factors, emission profiles by provinces (regions), policy-relevant insights, policy-driven technology adoption. The differences include data coverage, treatment technology mix, etc. The study explored how factors like regional climate, population density, and economic structure interact with wastewater treatment to affect emissions.

Conclusions

In this paper, the total amounts of GHG and CO2-eq emissions generated by urban wastewater treatment, the GHG (CO2-eq) emissions in the different wastewater treatment stages, and the contribution rates of GHG emissions in the different stages were calculated for China from 2011 to 2020. The annual GHG emission variation and the reasons for the differences among the 31 provinces were discussed. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

From 2011 to 2020, the total CO2-eq emissions generated by urban wastewater treatment were 1478.51 million tons in China. The annual average CO2-eq emissions are 147.9 million tons. The GHG variation trend first decreased and then increased. GHG emissions are high in the eastern regions of China, such as Guangdong and Shandong, while GHG emissions are low in the western regions of China. The GHG emission contribution rates are the highest in the industrial wastewater treatment stage, during which the production of paper and chemical products and side food production have important impacts on GHG emissions due to the high COD content during wastewater discharge. GHG emissions from power and chemical product consumption are closely related to industrial and domestic wastewater treatment. GHG emissions from the domestic wastewater treatment stage show a significant positive correlation with the population and the urbanization rate. CH4 emissions in the wastewater collection and discharge stage exhibited a significant negative correlation with pipeline length.

-

(2)

CH4 emissions account for the largest proportion of all GHG emissions (63.08%). The most important CH4 source is from the industrial wastewater treatment stage. The annual average CO2 emissions account for 22.24% of the total GHG emissions and are mainly generated during the power and chemical consumption stages. The annual average N2O emissions account for 14.68% of the total GHG emissions and are mainly generated during the wastewater collection and discharge stages.

In the future, GHG emission reduction strategies should focus on CH4 emissions in the industrial wastewater treatment stage and develop CH4 recycling and utilization technologies.

-

(3)

By combining technology specificity (tailored to industrial wastewater types) and regional targeting (aligned with emission hotspots), CH4 recovery becomes a scalable mitigation strategy. For example, a chemical plant in Jiangsu using UASB + biogas upgrading can reduce CH4 emissions by 60–80% while generating 50,000–100,000/year in energy savings—creating a “win-win” for emissions reduction and industrial cost-cutting. Regional prioritization ensures limited resources are directed to areas where impact is greatest, strengthening the applied value of the original research conclusion.

-

(4)

Future research should prioritize in the field of technology-specific emission factor development (Targeted Factor Calibration, cross-technology comparison), life-cycle assessment (LCA), cross-sectoral synergies (synergy with renewable energy systems, synergy with industrial symbiosis, as well as long-term monitoring and adaptive management.

Data availability

All the data and materials in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Çapa, S., Özdemir, A., Günkaya, Z., Özkan, A. & Banar, M. An environmental and economic assessment based on life cycle approaches for industrial wastewater treatment and water recovery. J. Water Process Eng. 49, 103002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2022.103002 (2022).

Yang, R. & Yuan, L. Generation, emission reduction/utilization, and challenges of greenhouse gas nitrous oxide in wastewater treatment plants–A review. J. Water Process Eng. 53, 103871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2023.103871Rui (2023).

China CPPCC Network. Xi Jinping Speech at the General Debate of the 75th Session of the UN. General Assembly. March, 3, 2022. http://www.rmzxb.com.cn/2022/3062746 (2022).

The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (MOHURD), and the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE). Implementation Opinions on Promoting the Synergy of Pollution Reduction and Carbon Emission Reduction in Sewage Treatment" (NDRC and ERPC〔2023〕No. 1714) (2023).

The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (MOHURD)(2024). Notice on Launching the Selection of Green and Low-Carbon Benchmark Sewage Treatment Plants" (NDRC and ERPC〔2024〕No. 531).

Demir, Ö. & Yapicioglu, P. Investigation of GHG emission sources and reducing GHG emissions in a municipal wastewater treatment plant. J. Greenhouse Gases Sci. Technol. 2019(3), 948–964 (2019).

IPCC. IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. Vol. 2 (2006). http://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp

Li, Y. et al. Carbon accounting of A2O process based on carbon footprint in a full-scale municipal wastewater treatment plant. Journal of Water Process Engineering. 55, 104162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2023.104162 (2023).

Wei, Y.-M. et al. Policy and management of carbon peaking and carbon neutrality: A literature review. Engineering 14, 52–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2021.12.018 (2022).

Ramírez-Melgarejo, M., Reyes-Figueroa, A. D., Gassó-Domingo, S. & Güereca, L. P. Analysis of empirical methods for the quantification of N2O emissions in wastewater treatment plants: Comparison of emission results obtained from the IPCC Tier 1 methodology and the methodologies that integrate operational data. Sci Total Environ. 747, 141288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141288 (2020).

Xu, Y., Dezhi, Q. & Dongli, G. Emission inventory of greenhouse gas from urban wastewater treatment plants and its temporal and spatial distribution in China. J. Environ. Sci. 39(3), 1256–1263 (2018).

Du Wenjie, L. U. & Jiayuan, H. U. Y. Spatio-temporal pattern of greenhouse gas emissions in China’ s wastewater sector and pathways toward carbon neutrality. J. Nat. Water 2023(1), 166–175 (2023).

Mengjie, Y., Peng, M. & Wu, D. Greenhouse gas emissions from wastewater treatment plants in China: historical emissions and future mitigation potentials. J. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 190, 106794 (2023).

Chen, S., Zhang, L., Liu, B., Yi, H., Su, H., Kharrazi, A., Jiang, F., Lu, Z., Crittenden J. C. & Chen, B. Decoupling wastewater-related greenhouse gas emissions and water stress alleviation across 300 cities in China. Nature Water 1, 534–546. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-023-00087-4 (2023).

Qu, S. et al. Carbon footprint drivers in China’s Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants and Mitigation Opportunities through Electricity and Chemical Efficiency. Engineering 50, 106–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2024.01.021 (2024).

China National Development and Reform Commission (CNDRC). (2011). Guidelines for compiling the Provincial Greenhouse Gas List (Trial). Development and Reform Office climate (2011) No.1041.24, Sept, 2021.

Xie, T. & Wang, C. Greenhouse gas emissions from wastewater treatment plants. J. Tsinghua Univ. (Sci. Technol.). 52(4), 473–477 (2012).

Mingyang, Z., Changbo, Z. & Shenghao, L. Development of greenhouse gas accounting model and emission reduction potential analysis in wastewater treatment industry. J. Chin. J. Environ. Manag. 14(6), 55–64 (2022).

IPCC. Climate change 2014: Synthesis report. Switzerland 2014, 151 (2014).

The Ministry of Ecology and Environment, PRC. (2019). The annual emission reduction project in China regional Power grid baseline emission factors in 2019. https://www.mee.gov.cn/ywgz/ydqhbh/wsqtkz/202012/t20201229_815386.shtml

Zhang, Q., Nakatani, J. & Wang, T. Hidden greenhouse gas emissions for water utilities in China’ s cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 665–667 (2017).

The National Development and Reform Commission of the PRC. Guidelines for compiling the Provincial Greenhouse Gas List (Trial). Beijing 2011, 93–101 (2011).

Daiyan, L., Xinjian, L. & Jing, Y. Advance in utilization of ethanobacteria for anaerobic digestion studies. Fujian J. Agric. Sci. 23(1), 106–110 (2008).

Jiexia, L. A supply and demand analysis of Chinese residents’ dietary protein Beijing: Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, 4–7 (2018).

Lyu, P., Li, Z. & Zhao, H. (2020). Advances in water pollution control and resource recovery by membrane supported biofilm reactor. Microbiol. China 47(10), 3287–3304 (2020).

Dongdong, X., Da, K. & Leiyan, G. Research progress on Anammox granular sludge. Microbiol. China 46(8), 1988–1997 (2019).

Xiaodi, H., Xiangyang, W. & Daqi, G. Analysis of CO2 emission from fossil carbon in organics from wastewater. China Water Wastew. 34(2), 13–17 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study conception and design, material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Ke ZHOU.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Compliance with ethical standards

This article does not contain any studies performed by other authors and meets the ethical standards.

Consent to participate

The authors consented to participate in the work under the Ethical Approval and Compliance with Ethical Standards.

Ethical Responsibilities of Authors.

All authors have read, understood, and have complied as applicable with the statement on “Ethical responsibilities of Authors” as found in the Instructions for Authors of J. EMA.

Consent to publish

All the data in the paper can be published without any competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical approval

The author declares that there is no competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, K. Analysis of greenhouse gas emissions from urban wastewater treatment during recent years in China. Sci Rep 15, 45056 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31704-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31704-9