Abstract

With the large-scale construction and long-term operation of underground reservoirs in coal mines, the problem of surrounding rock stability under long-term water immersion has become increasingly prominent. Therefore, clarifying the dynamic response of rocks under long-term immersion and impact loads is of great theoretical significance for ensuring the safe operation of coal mine reservoirs throughout their entire life cycle. In this study, sandstone samples were immersed in water for 0, 3, 30, 90 and 180 days respectively. The microstructure characterization and dynamic tests were carried out by using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), computed tomography (CT), and an improved separated Hopkinson compression bar (SHPB) system. The results show that: (1) The combined results of SEM, NMR and CT tests indicate long-term impregnation reduces the proportion of micropores and increases the proportion of mesopores and macropores. The total dissolved solids (TDS) concentration in the impregnating solution increases with time, and the pH value of the solution first rises and then decreases with the extension of the immersion time. (2) The faster the impact velocity, the greater the frequency and amplitude of the stress wave generated. The water saturation gradually increases with immersion, weakening the discontinuity of acoustic impedance and reducing the reflection coefficient at the interface. (3) The increase in impact velocity intensifies fragmentation and promotes the development of complex fracture networks. With the extension of immersion time, the expansion of clay minerals such as montmorillonite will generate expansion stress, thereby creating micro-cracks, which leads to a higher fractal dimension of the crack network and eventually stabilizes over time. (4) Under the action of impact loads, the proportion of intergranular fractures increases with the extension of immersion time. However, at high impact speeds, the relative strength contrast between the cementing material and quartz particles leads to an increase in transgranular fracture. Overall, this study provides guidance for the safe design and operation of underground reservoirs in coal mines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to China’s medium- and long-term energy development strategy, coal will remain the dominant energy source in the foreseeable future. Underground water reservoirs in coal mines, serving as a key technology for the integrated utilization of coal and water resources, have become an essential guarantee for safe and efficient extraction in deep mining areas1,2,3,4. With the large-scale construction and long-term operation of such reservoirs, the stability of surrounding rock under hydro-mechanical coupling has become a critical concern. As shown in Figure 1 (created with Rhino 8 software), reservoir rocks are continuously immersed in groundwater, where water-rock interactions lead to mineral dissolution, weakened cementation, and the propagation of fracture networks, significantly altering the mechanical properties of the rock mass5,6,7. Under impact loading, rocks subjected to prolonged water immersion are prone to time-dependent damage, which may trigger engineering hazards such as reservoir leakage and rock instability, posing serious risks to mine safety8,9,10. Therefore, elucidating the dynamic response mechanisms of rocks under the coupled effects of long-term water immersion and impact loading holds important theoretical significance for ensuring the safe lifecycle operation of underground water reservoirs in coal mines.

The dynamic behavior of rocks under impact loading has long been a central topic in rock mechanics. Early studies primarily focused on dynamic stress–strain responses and strength criteria. For example, Lu et al.11 and Du12 employed split Hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) tests to systematically analyze sandstone and granite under varying strain rates, confirming a strong positive correlation between rock strength and strain rate. Li et al.13 showed that how energy is distributed (as reflection, transmission, and absorption) is closely linked to microcrack growth and how fractures form. Du et al.14 used SHPB tests and fractal theory to study the particle size distribution of broken rocks at high strain rates, suggesting a failure mechanism explained by energy. In general, research on impact loading has moved beyond just strength analysis to more complete studies looking at energy dissipation, fractal patterns, and damage models.

Moisture content is another critical factor influencing rock mechanics. Liu et al.15 showed that water-saturated sandstone exhibits greater damage and reduced strength in uniaxial compression tests. Liang16, through direct shear tests on rocks immersed for different durations, found that reduced fracture energy, lower friction coefficients, and chemical corrosion drive the decline in shear strength. Wang et al.17 systematically analyzed the influence of water on coal rock stress–strain behavior, peak strain, and elastic modulus, and proposed a corresponding damage constitutive model. Feng18, using true triaxial tests, found that the peak strength of saturated sandstone decreases markedly with water saturation. In general, increased water content weakens cementation, promotes mineral dissolution, and accelerates crack propagation, thereby reducing rock strength and stiffness—a phenomenon widely validated in experiments19.

More recently, research has begun to investigate the coupling effects of dynamic loading and water saturation. Chen et al.20 reported that a higher water content significantly reduces the dynamic compressive strength of sandstone in SHPB tests, while also highlighting differences between static and dynamic failure mechanisms. Xu et al.21 investigated the dynamic responses of sandstone under varying strain rates and water contents, developing a constitutive model for saturated rocks under dynamic loads. Kong et al.22 observed that water may enhance the dynamic toughness of saturated sandstone and explored the underlying mechanisms. Yin et al.23 proposed an energy calculation method for water-bearing rocks under dynamic loading and analyzed the influence of water on energy dissipation. Collectively, these studies suggest that the coupling of impact loading and water saturation induces complex changes in strength, energy absorption, and fracture patterns24,25. However, most existing research remains confined to experimental observations and empirical modeling, with limited insights into the systematic evolution of energy, microscopic fracture processes, or numerical back-analysis.

In summary, while previous research has advanced the understanding of impact loading and water effects individually, and partially in combination26,27, challenges remain. Current studies are often limited by simplified models, narrow test conditions, and insufficient mechanistic explanations. In particular, the energy evolution, damage progression, and hazard mechanisms of rocks subjected to long-term water immersion and high strain-rate impact are still not fully understood. Addressing these gaps is crucial not only for advancing rock dynamics theory but also for ensuring the safe operation of underground water reservoirs and deep mining projects.

Sampling and sample preparation

As shown in Figure 2 (Figure 2c was drawn by myself using visio software), the sandstone specimens used in this study were collected from a mining area in Inner Mongolia. The map was created using ArcGIS 10.8 software. URL: https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/resources. For more information about Esri software, please visit www.esri.com. During sampling, preference was given to structurally intact cores without visible fractures to ensure representativeness and integrity28. After collection, the initial mass of each specimen was recorded. The samples were then dried in an oven at 100 °C for 24 h to remove natural moisture, and the dry mass was subsequently measured.

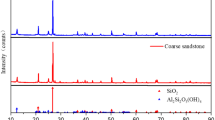

To characterize the fundamental mineral composition of the sandstone and its potential changes during long-term immersion, X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed. The results indicate that the bulk mineralogy is dominated by quartz (54.7%), followed by potassium feldspar (16.3%), calcite (5.2%), and dolomite (3.8%). In addition, the samples contain notable amounts of clay minerals, including montmorillonite (6.1%), illite (6.9%), and kaolinite (7.0%).

For consistency and comparability of the impact tests, all specimens were prepared in accordance with International Society for Rock Mechanics (ISRM) standards, with dimensions of Φ50 mm × 50 mm (diameter × height)29,30,31. Microscopic and visual inspections confirmed that the samples contained no obvious pre-existing cracks or macroscopic defects, providing a reliable basis for subsequent mechanical testing. The XRD results not only revealed the mineralogical composition of the sandstone but also offered key insights into the clay mineral content and microstructural features relevant to its mechanical behavior.

Experimental program and principles

Experimental scheme

This study aims to quantitatively investigate the microstructural evolution and dynamic mechanical response of sandstone from coal mine underground reservoirs under long-term water immersion and dynamic loading. As illustrated in Figure 3, a multi-scale experimental approach was adopted. First, sandstone specimens were immersed in a simulated groundwater environment for five durations: 0 days (dry reference), 3 days (short-term), 30 days (mid-term), 90 days (medium–long term), and 180 days (long-term), in order to replicate time-dependent seepage damage during reservoir operation.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) was employed to quantify pore distribution and crack propagation across immersion stages, supplemented by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to observe mineral dissolution (e.g., feldspar hydrolysis pores) and secondary mineral deposition (e.g., clay filling along fractures). In addition, leachates collected at each stage were analyzed for major ions (Ca2⁺, Mg2⁺, K⁺) to clarify water–rock chemical interactions, such as calcite dissolution leading to peak Ca2⁺ concentrations, and their role in weakening the rock structure.

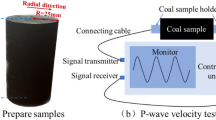

To assess the effect of dynamic loading, split Hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) tests were conducted at three impact velocities—5 m/s (low), 10 m/s (medium), and 15 m/s (high)—to capture stress wave propagation, fragmentation energy dissipation, and strength degradation. to ensure the reliability and repeatability of the experimental results, at least three parallel samples were prepared for each group of experimental conditions for testing. On this basis, a quantitative model linking “immersion-induced damage–impact velocity–dynamic strength” was established, providing theoretical support for the safe operation of coal mine underground reservoirs. Figure 4 shows the experimental apparatus.

Experimental principles

Sandstone specimens subjected to varying water immersion durations were tested under dynamic impact loading at different projectile velocities (5, 10, and 15 m/s). The objective was to investigate the effects of dynamic loading on the mechanical behavior of sandstone under different saturation conditions. Stress, strain, and strain rate of the sandstone under each immersion condition were calculated using the following formulas32,33:

where \(A \text{and}\) \({l}_{s}\) is represent the cross-sectional area and length of the specimen, respectively; \({c}_{0}\), \({A}_{0}\) and \(E\) denote the longitudinal wave velocity, cross-sectional area, and elastic modulus of the bars. \({\varepsilon }_{i}(t)\), \({\varepsilon }_{r}(t)\) and \({\varepsilon }_{t}(t)\) correspond to the incident, reflected, and transmitted strain waves, respectively.

Results and analysis

Porosity analysis of rock

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) technology characterizes the structure of porous media by quantifying differences in proton relaxation behavior within pore fluids. Initially, randomly oriented protons are magnetized along the static magnetic field (B0B_0B0). After excitation by a radio-frequency pulse, the protons deviate from equilibrium, and upon removal of the excitation field, they relax back to the ground state through precessional motion. This process is captured by the CPMG sequence as an exponentially decaying train of spin echoes. Multi-component fitting of the echo data generates the transverse relaxation time (T2) distribution.

The relaxation of pore fluids is governed by three mechanisms: bulk relaxation (intrinsic fluid properties), surface relaxation (interactions at solid–liquid interfaces), and diffusion relaxation (molecular motion in magnetic field gradients). These mechanisms are collectively expressed as34:

Here, T2 represents the transverse relaxation time of pore fluid; T2bulk denotes the transverse relaxation time in a large container (bulk relaxation); and T2surfacand T2diffusion correspond to relaxation due to surface interactions and diffusion, respectively.

For water-saturated pores measured with short echo spacing (TE), surface relaxation dominates, and T2 is proportional to the pore size, expressed as follows:

Where \(\rho_{{2}}\) denotes the surface relaxation rate and \((\frac{S}{V})_{\begin{subarray}{l} {\text{pore}} \\ \end{subarray} }\) represents the specific surface area of the pores. By introducing a simplified model, the rock pores can be approximated as cylindrical capillaries with a radius rrr. Based on this assumption, the relationship between the T2 spectrum and the pore size distribution can be expressed as:

The T2 relaxation time reflects the chemical environment, binding state, and mobility of hydrogen protons within a sample, and is therefore closely associated with its internal structure. In porous media, water molecules in larger pores exhibit longer relaxation times, whereas those in smaller pores experience stronger confinement and thus shorter relaxation times. Consequently, the position of a T2 peak is related to pore size, while its area corresponds to the abundance of pores of that size.

In this study, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) was applied to measure the transverse relaxation time (T2) distribution curves of water-immersed sandstone samples. According to NMR theory, the T2 value of sandstone is positively correlated with the pore-throat radius, and both the amplitude and position of peaks in the T2 distribution quantitatively characterize pore development. A peak shift toward longer T2 times indicates enlarged pore sizes, while an increase in peak amplitude reflects a higher pore abundance. As shown in Figure 5, all samples exhibited a typical bimodal T2 distribution, confirming the coexistence of micropores (short-T2 peak) and medium-to-large pores (long-T2 peak). With prolonged immersion, the overall T2 spectrum broadened and peak intensity markedly increased (e.g., the 150-day sample showed a ~32% higher peak amplitude than the 0-day sample), clearly revealing that water–rock interaction promotes pore expansion and enhances structural connectivity. The evolution of the pore structure of rocks observed after long-term water immersion from "dominated by micropores" to "an increase in medium and macropores" mainly stems from the physicochemical process of water-rock interaction. The core mechanisms include: (1) Dissolution of minerals and collapse of micropores: Pore water, especially when it contains CO₂, can dissolve calcite and other cementing substances as well as unstable minerals. This process preferentially occurs on the inner walls of micropores with a huge specific surface area, leading to thinning of the pore walls and structural weakening. Eventually, they collapse under internal stress, causing adjacent micropores to merge into larger pores. (2) Weakening effect of expansive minerals: If expansive minerals such as montmorillonite exist, their water absorption and expansion will exert local stress on the surrounding microporous framework, accelerating the destruction of the microporous structure in a synergistic manner. These two processes jointly weaken the intergranular bonding force of the rock, leading to the loosening and reorganization of the microscopic framework. Ultimately, the coarsening and penetration of pores directly lead to the deterioration of macroscopic mechanical properties and the enhancement of permeability. To quantify pore evolution, the pores were divided into three categories based on T2 peak characteristics, with detailed classification provided in Table 1. These NMR results elucidate the deterioration mechanism of water-immersed sandstone at the pore scale and offer key theoretical insights for evaluating rock mass stability in underground coal mine reservoirs.

Analysis of rock microstructure

In this study, the microstructural evolution of sandstone under varying immersion durations was investigated using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Fig. 6). At 0 days, the samples exhibited a compact matrix with smooth and continuous surfaces, containing only a few isolated micropores and microcracks (Fig. 6a). After 3 days of immersion, surface roughness increased significantly, accompanied by a rise in the proportion of large pores and a reduction in micropores. This phenomenon is attributed to the swelling of clay minerals upon water absorption, which compresses pore space and highlights the key role of clay constituents in weakening the rock structure (Fig. 6b). With a prolonged immersion of 30 days, mineral particle boundaries became more distinct, and local detachment of fragments generated flocculent loose structures, indicating a decline in cementation strength (Fig. 6c). By 90 days, feldspar particles developed evident dissolution pits with residual skeletal edges, reflecting the destructive effect of hydrolysis on the mineral framework (Fig. 6d). After 180 days, dissolution-induced pores expanded and interconnected, forming a macropore network with intensified surface irregularities (Fig. 6e), suggesting a complete reorganization of the microstructure.

These observations demonstrate that clay mineral swelling and feldspar dissolution are the dual driving mechanisms behind pore structure evolution. The former physically reduces micropores through expansion, whereas the latter chemically enlarges macropores via dissolution, collectively shifting the pore size distribution toward larger scales. Such microstructural deterioration directly undermines the macroscopic mechanical behavior of sandstone: enhanced pore connectivity diminishes load-bearing capacity, while surface fragmentation promotes stress concentration, ultimately influencing rock fracture modes. These findings provide a micro-mechanical basis for predicting the long-term stability of coal mine underground reservoir banks and offer critical insights for assessing engineering risks under coupled seepage–damage conditions.

CT scanning test

To characterize the mesostructural distribution of sandstone under different immersion durations, CT scanning tests were performed (Fig. 7). Figure 7 shows the CT three-dimensional reconstruction results of the sample at different stages. With the increase of the action time, the internal structure of the sample gradually transforms from the initial layered structure to a complex network of fragmentation and enhanced connectivity. CT images reveal the process of the increase in pore volume fraction at the meso scale and the evolution of pore morphology from regular bands to irregular blocks and connected shapes, reflecting the deterioration mechanism and microstructure evolution law of rock masses under external influences. The images show that, consistent with SEM observations, the unsoaked sandstone exhibits an intact internal structure with low porosity and almost no visible cracks. After 3 days of immersion, local mineral swelling induced microcracks and slightly increased porosity. At 30 days, cementing materials began to detach, and an initial pore network formed. By 90 days, porosity increased significantly with more interconnected pores. After 180 days of immersion, the pore network became more extensive, accompanied by particle detachment, indicating substantial microstructural degradation.

From a microscale analysis, the pores in the early samples were mainly distributed along the bedding planes or weak cementation interfaces, indicating that there was a coupling relationship between the stress and the structural plane direction. In the later samples, the pores expanded into the interior of the overall structure, locally forming connected channels, showing the phenomenon of micro-fissure penetration and pore aggregation. This change in pore connectivity directly affects the permeability and mechanical properties of the medium.

To improve the quantitative analysis accuracy of CT data, this study combines multiple image processing and voxel-level analysis techniques. Firstly, the median filtering and non-local mean denoising (NLM) algorithm are adopted to eliminate the scanning noise points and retain the true pore boundaries. Subsequently, the solid phase and the pore phase are distinguished through a segmentation algorithm based on the Otsu adaptive threshold, achieving the phase classification of grayscale voxels. Then, the three-dimensional connected domain labeling algorithm is utilized to extract the characteristic parameters of the pore network, such as pore size distribution, porosity, morphological factor and connectivity. The specific parameters are shown in Table 2.

Analysis of rock chemical properties

To elucidate the weakening mechanism of sandstone mechanical properties induced by water–rock chemical interactions during long-term immersion, systematic hydrochemical analyses were conducted on the leachates. Cation concentrations were measured using ion chromatography, SiO₂ content was determined via the molybdenum blue spectrophotometric method, and pH values were monitored to track solution acidity. Table 3 presents the ion release data for immersion durations from 0 to 180 days, and the temporal evolution of ion concentrations is illustrated in Figure 8. The results indicate that total dissolved solids (TDS) increased monotonically with immersion time (validated by TDS measurements), directly confirming the continuous migration of mineral components from sandstone into the liquid phase. Mechanistically, water infiltrates the pore network, promoting mineral dissolution and hydrolysis, which releases soluble ions (e.g., Ca2⁺, K⁺) and colloidal SiO₂. This process induces a dual effect. (1) Pore structure evolution – mineral dissolution enlarges pore volume and enhances pore connectivity. (2)Framework strength reduction – loss of active components (clay minerals, cementing materials) weakens interparticle bonding. The combined action of these effects ultimately governs the macroscopic mechanical behavior of sandstone. These findings provide a chemical–kinetic basis for predicting the long-term stability of water-immersed rock masses.

Based on a comprehensive analysis of Table 2 and Figure 8, the reactions occurring in sandstone during immersion in water can be summarized as follows:

Calcite (CaCO₃) and dolomite (CaMg(CO₃)₂) undergo dissolution, releasing Ca2⁺ and Mg2⁺ ions. The reactions can be expressed as follows35,36:

With prolonged immersion, the amount of dissolved substances in the leachate continuously increases, potentially promoting the formation of additional pores and weakening the bonding between mineral grains. Moreover, hydrochemical reactions may cause partial dissolution or transformation of minerals, gradually altering the sandstone’s internal structure. These changes significantly affect the rock’s strength, toughness, and deformation behavior. Feldspar minerals, for example, generate illite and kaolinite, with potassium feldspar producing clay minerals (kaolinite) during the early stages of corrosion. The reaction can be represented as follows:

When the K⁺ concentration in the pore fluid reaches the saturation level of potassium feldspar, the excess K⁺ gradually transforms into illite within illite and kaolinite. Conversely, when the K⁺ concentration is below the saturation point of potassium feldspar, the corrosion of potassium feldspar produces illite. The reaction can be expressed as follows36:

From Table 2 and Figure 8(a), it can be observed that the pH of the leachate initially increases and then decreases with prolonged immersion time, indicating that the dissolution of calcite and dolomite predominantly occurs during the early stage. Additionally, the HCO₃⁻ produced by these reactions contributes to the initial rise in pH. As shown in Figure 8, after 40 days of soaking, Mg2⁺ and Ca2⁺ concentrations continue to increase, while K⁺ reaches its peak. At this stage, potassium feldspar begins to undergo corrosion, producing OH⁻ and further elevating the pH of the leachate. With continued immersion, Figure 8(c) shows that both K⁺ concentration and pH first rise and then decline. This trend is likely due to K⁺ levels exceeding the saturation point of potassium feldspar in the solution, prompting the conversion of kaolinite to illite, which releases H⁺ and consumes part of the K⁺ (Eq. 8). Throughout the soaking process, part of the released SiO₂ dissolves into the leachate as colloidal matter, while the remainder adheres to pore walls or precipitates. Overall, hydrochemical analyses of sandstone leachates reveal the water–rock interactions occurring during long-term immersion, leading to changes in microstructure and mineral composition that affect macroscopic mechanical properties.

NMR and SEM observations, combined with hydrochemical data, indicate significant evolution of the pore structure under prolonged water exposure. Specifically, micropore numbers decrease while macropore numbers increase substantially, reflecting a complex microstructural transformation: closure of micropores is accompanied by the expansion and interconnection of larger pores and cracks, forming an intricate pore–fracture network. These microstructural changes critically influence sandstone’s macroscopic mechanical behavior, as the development of pores and fractures reduces rock integrity and markedly diminishes its load-bearing capacity.

Peak stress

Peak stress represents the ultimate load-bearing threshold of rock and is fundamentally governed by its microstructural properties, including pore distribution, cementation strength, and particle arrangement. SHPB tests shown in Figure 9 indicate a positive correlation between projectile velocity (5→15 m/s) and sandstone peak stress. Mechanistically, under low-velocity impacts, cracks preferentially propagate along pre-existing weak planes (e.g., clay layers, grain boundaries), reducing load-bearing efficiency. In contrast, high-velocity impacts promote rapid transgranular crack propagation, limiting growth along weak planes and effectively enhancing apparent strength—an effect attributable to the rate-dependent behavior of dynamic crack propagation.

Figure 9 further demonstrates that longer water immersion reduces sandstone strength. This weakening likely arises from multiple water–rock interaction pathways: pore water pressure, chemical corrosion, reduction in intergranular cohesion, decreased fracture energy, and swelling mineral transformations. Combined evidence from NMR, SEM, and hydrochemical analyses reveals that long-term water exposure induces dual microstructural deterioration—pore enlargement (with macropores accounting for up to 65%) and mineral softening (e.g., potassium feldspar alteration to kaolinite)—resulting in a 35–50% reduction in dynamic peak stress after 150 days compared with 0 days. This damage sequence confirms that structural reorganization caused by immersion (pore network expansion plus mineral alteration) is the primary driver of reduced dynamic load-bearing capacity. Although no new constitutive relationship was established in this study, our experimental observation, namely the nonlinear decreasing trend of strength with the increase of water immersion time, is qualitatively consistent with the prediction results of the damage constitutive model proposed by Han et al. (2024)35. This, from the side, verifies our view that the damage mainly occurred during the period of water immersion. Based on the experimental data of this study, an important task in the future will be to establish a constitutive damage model that can comprehensively consider the interaction between water immersion time and dynamic load, in order to achieve precise prediction of the mechanical behavior of materials and life assessment.

Peak strain

Under dynamic loading, as shown in Figure 10 and Table 4., the peak strain of sandstone increases with rising impact velocity. This indicates that the sandstone can endure larger deformations before failure. The phenomenon is primarily attributed to the strain-rate effect, which reflects the material’s high sensitivity to loading rate or strain rate (strain per unit time), affecting its strength, deformability, and failure mode. At low impact velocities, microcracks within the sandstone have sufficient time to initiate, propagate, and coalesce at stress concentration sites such as grain boundaries and pore edges, forming dominant macroscopic cracks that lead to relatively “brittle” failure and smaller peak strains.

In contrast, at high impact velocities, the loading occurs too rapidly for microcracks to fully extend and merge. Stress waves propagate quickly, distributing the stress more evenly (or generating complex stress fields), which induces deformation over a wider area and the formation of additional microcracks rather than concentrating damage along a few cracks. Consequently, greater overall deformation (i.e., higher peak strain) is required to accumulate sufficient damage to trigger macroscopic failure. Moreover, at high velocities, inertial effects become significant, hindering rapid crack opening and localized deformation (e.g., shear band formation). The material must undergo a longer acceleration process to reach the critical condition for failure, resulting in larger macroscopic deformability. In essence, inertia “holds back” fragments that are about to separate, allowing the structure to sustain higher deformation while still bearing load.

Under impact loading, stress waves propagate through the material, and higher impact velocities generate waves with greater amplitudes and steeper wavefronts. The material experiences elevated stress and strain gradients along the wavefront. When these waves encounter defects such as pores, cracks, or interfaces, complex interactions like reflection and refraction occur, leading to localized stress concentrations and more dispersed energy dissipation zones. This intricate stress state and the more distributed energy dissipation promote broader, relatively uniform plastic deformation and micro-damage accumulation prior to failure, thereby increasing the overall peak strain.

As shown in Figure 10, with prolonged water immersion, the peak strain of sandstone also increases (i.e., it can endure greater deformation before failure), but the underlying mechanism differs from the strain-rate effect under impact loading. Extended water exposure primarily affects sandstone through physicochemical degradation resulting from water–rock interactions. Observations in Figures 9 and 10 indicate that short-term immersion (hours to a few days) slightly increases peak strain, while medium- to long-term immersion (months) leads to a significant rise in peak strain alongside a notable reduction in peak stress.

The mechanisms behind this increase in peak strain include: Clay mineral expansion and hydration softening: The sandstone contains hydrophilic clay minerals (e.g., montmorillonite, illite, kaolinite) within the cement or detrital particles. Over time, these minerals absorb water and swell, especially montmorillonite, generating significant expansion stresses at particle interfaces or cemented zones. Simultaneously, water molecules weaken inter-particle bonds (hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces), reducing strength and stiffness. The combined effect lowers overall sandstone rigidity, facilitating plastic deformation at lower stress levels, thus increasing peak strain and making the material macroscopically “softer” and more ductile.

Cement dissolution: Minerals such as calcite, dolomite, gypsum, and portions of siliceous or iron oxides dissolve in water over time. Prolonged immersion enhances dissolution, weakening inter-particle cementation and enlarging existing pores. This degradation reduces sandstone strength and elastic modulus, allowing particles to slide, rotate, and rearrange more easily, which enhances macroscopic plastic deformation and elevates peak strain. Consequently, failure transitions from brittle fracture to a more gradual, particle-adjusted mode.

Pore water pressure effects: In saturated and poorly drained conditions, internal pore water pressure suppresses microcrack propagation and reduces inter-particle friction, promoting yield and plastic flow at lower stress levels. Extended immersion ensures full saturation, enabling this effect, while potential changes in pore structure may further influence the distribution and transmission of pore pressures. Water lubrication: Water at particle contacts, microcrack surfaces, and mineral cleavage planes reduces friction and facilitates sliding. With longer immersion, water penetrates these interfaces more thoroughly, promoting wider non-elastic deformation and further increasing peak strain. In summary, prolonged water immersion enhances peak strain by combining microstructural softening, cement dissolution, pore pressure effects, and interfacial lubrication, fundamentally altering sandstone’s mechanical response under dynamic loading.

Analysis of energy evolution characteristics

As previously mentioned, variations in soaking duration inevitably alter the mineral composition of the rock25. Consequently, under dynamic loading, the energy conversion process is influenced by the soaking time. Accordingly, this study investigates the energy transformation of sandstone using the following equations37:

Here, \({W}_{I}\), \({W}_{R}\), and \({W}_{T}\) represent the incident, reflected, and transmitted energies, respectively, while \({W}_{S}\) denotes the energy absorbed by the specimen. Using the above equations, the energy characteristics of the sandstone were calculated, as summarized in Table 5.. It can be seen from Table 5. that the energy evolution of sandstone varies significantly under different projectile velocities and soaking durations.

As shown in Figures 11(a) and Figures 11(d), an increase in impact velocity leads to a decrease in the ratio of reflected energy to incident energy and an increase in the ratio of transmitted energy to incident energy in sandstone. The underlying reason is that higher impact velocities generate stress waves with higher frequencies and stronger amplitudes. High-frequency waves are more easily scattered and absorbed by microcracks, pore fluids, and mineral grain interfaces during propagation through rock, resulting in significant attenuation of reflected wave energy. Conversely, a portion of the high-frequency energy is more readily transmitted into the rock mass at interfaces, thereby reducing the proportion of reflected energy. High-velocity impacts may alter the state of contact interfaces (e.g., probe-rock or rock-air/water interfaces), such as causing local compaction or instantaneous increases in pore water pressure. These changes reduce the acoustic impedance contrast, leading to a decrease in the instantaneous reflection coefficient and an increase in the transmission ratio. As shown in Figure 11(c), higher impact velocities result in greater incident energy, with a larger proportion of this energy entering the rock mass to drive wave propagation and damage, rather than being reflected. This thereby causes the ratio of reflected to incident energy to decrease, while the ratio of transmitted to incident energy concurrently increases.

As shown in Figures 11(a) and Figures 11(d), an increase in water immersion time leads to a decrease in the ratio of reflected energy to incident energy and an increase in the ratio of transmitted energy to incident energy in sandstone. This is because prolonged immersion causes the pores of sandstone to gradually fill with water, increasing its pore water saturation. When air in the pores is replaced by water, the overall acoustic impedance discontinuity of the rock is reduced, resulting in a lower reflection coefficient at interfaces. Consequently, reflected energy decreases, and more energy is transmitted into the rock mass. Water immersion induces the hydration, dissolution, or softening of cementing materials (e.g., calcite, dolomite, and clay minerals) between mineral grains, resulting in a reduced elastic modulus and slight density changes. As elastic waves propagate through this deteriorated medium, their reflection at interfaces is weakened, while internal energy dissipation increases. This reduces the amplitude and proportion of reflected waves while increasing the amplitude and proportion of transmitted waves. The hydration process can also generate microcracks, enhancing wave scattering and absorption. Particularly under saturated conditions, the viscous damping of pore fluids significantly attenuates high-frequency energy, making the loss of reflected wave energy more pronounced.

As shown in Figures 11(b) and Figures 11(e), an increase in impact velocity leads to higher energy utilization and energy density in sandstone. High-impact velocities generate stress waves with higher amplitudes and richer high-frequency components, allowing wave energy to more easily enter the rock mass rather than being reflected at interfaces. The propagation of high-frequency waves in rock excites responses from more microscopic defects, promoting microcrack propagation and slip between mineral grains, thereby converting more incident energy into internal damage energy.

Fractal dimension analysis

The macroscopic failure characteristics of rock alone cannot adequately quantify the degree of sandstone fragmentation. In recent years, fractal theory has been shown to more effectively describe rock damage under impact loading, as well as the initiation and propagation mechanisms of internal fractures. In this study, the Gate-Gaudin-Schuhmann (G-G-S) fractal dimension model was employed to quantitatively characterize sandstone damage under impact loading. The model is expressed as follows38:

In the formula, \(r\) represents the size of a specific fragment, \(R_{1}\) is the maximum fragment size, and \(b\) is the sandstone distribution parameter. Let \(M_{r}\) denote the cumulative mass of fragments smaller than a given size \(r\) \(M_{r}\); then the ratio of the cumulative fragment mass \(M_{r}\) to the total fragment mass \(M\) also follows the G-G-S function. Accordingly, Equation (14) can be rewritten as:

By taking the derivative of Equation (15), one can obtain:

Since the relationship between block size and incremental mass satisfies:

According to Turcotte’s study, the fractal dimension D, the fragment size r, and the number of fragments corresponding to an equivalent particle size N at that fragment size satisfy:

According to the definition of fractals, the fractal dimension D can be expressed as:

Here, N represents the number of fragments with a particle size of r.

By combining Equations (14) through (19), we can derive:

By taking the logarithm of both sides of Equation (20), we obtain:

Based on Equation (21), using the experimentally obtained fragment mass and particle size data, a double-logarithmic plot of \({\text{ln}}\left( {{\raise0.7ex\hbox{${M_{r} }$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{M_{r} } M}}\right.\kern-0pt} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$M$}}} \right) - {\text{ln}}\left( {{\raise0.7ex\hbox{$r$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {r {R_{1} }}}\right.\kern-0pt} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{${R_{1} }$}}} \right)\) is drawn and linearly fitted. The slope \(3 - D\) of the fitted line is then used to determine the fractal dimension \(D\).

As shown in Fig. 12, th \({\text{ln}}\left( {{\raise0.7ex\hbox{${M_{r} }$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{M_{r} } M}}\right.\kern-0pt} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$M$}}} \right) - {\text{ln}}\left( {{\raise0.7ex\hbox{$r$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {r {R_{1} }}}\right.\kern-0pt} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{${R_{1} }$}}} \right)\) curves of sandstone under different impact loads indicate that the degree of fragmentation increases with rising impact velocity. The correlation coefficients R2 all exceed 0.85, demonstrating a strong linear relationship and confirming that the mass distribution of sandstone fragments under impact loading follows fractal scaling.

As shown in Fig. 12, the fractal dimension of sandstone increases significantly with rising impact velocity (or strain rate), indicating more severe fragmentation and a more intricate crack network. This trend is closely linked to energy input, fracture mechanisms, and microscopic responses. The main reasons are:

Energy input escalation: Higher impact speeds lead to an exponential increase in incident energy. At low speeds, energy mainly drives the propagation of a single dominant crack, whereas at high speeds, it is dissipated through multiple crack branches and frictional heating.

Fracture mechanism transition: Low-speed impacts primarily induce tensile failure along mineral boundaries, resulting in smooth fracture surfaces (lower fractal dimension). High-speed impacts increase the proportion of transgranular fractures, enhancing complexity.

Enhanced microscopic response: The strain-rate effect accelerates crack nucleation and propagation while suppressing healing. The interaction between pores and microcracks generates local tensile stress at pore sites, promoting the detachment of small particles.

Additionally, Fig. 12 shows that the fractal dimension of sandstone generally rises with longer water immersion and tends to stabilize after 180 days. This evolution is dominated by microstructural changes induced by water–rock interactions, specifically:

Clay expansion: Hydrophilic minerals such as montmorillonite absorb water, swell, and generate expansion stresses, which compress surrounding mineral grains and form microcracks.

Cement softening: Water weakens the bonding between mineral particles, reducing elastic modulus and facilitating microcrack propagation. Post-immersion, primary cracks exhibit larger branching angles, and secondary cracks increase in number.

These mechanisms collectively enhance the complexity of the crack network, reflected in the increase of the fractal dimension.

Analysis of microscopic fracture mechanisms

Based on the above research, the failure mode of sandstone under impact loading is primarily brittle fracture, which can be classified into transgranular and intergranular fractures. The main differences between these two types are as follows: Transgranular fracture occurs through the interior of mineral grains, with clearly defined grain boundaries. The cracks tend to be linear and often radiate outward from the center of larger grains.Intergranular fracture propagates along the grain boundaries, where the boundaries appear less distinct. The cracks are generally more radial or branching, often originating from the edges of smaller grains. In terms of appearance, transgranular cracks usually have lighter-colored grain boundaries, while intergranular cracks show darker boundaries. Intergranular fracture occurs because, after failure, the cementing material within the sandstone is weaker than the crystal itself, causing cracks to propagate along the grain boundaries under impact. Typically, intergranular fracture surfaces exhibit pronounced grain structures with a three-dimensional texture, often resembling a “sugary” or crystalline pattern.

As shown in Fig. 13, the proportion of intergranular fractures in sandstone under impact loading generally increases with prolonged water immersion. This trend is closely related to the physicochemical effects of water, which progressively weaken the grain boundaries, making cracks more likely to propagate along them. The mechanisms can be summarized as follows: Physical weakening (dominant in short-term immersion): Grain boundary lubrication: Water molecules penetrate mineral boundaries, reducing interfacial friction and facilitating stress wave propagation along grain boundaries (“lubrication effect”). Pore pressure increase: An increase in pore pressure occurs as water filling microcracks generates elevated transient pore pressure under impact loading. This pressure preferentially propagates cracks along weak grain boundaries, particularly in porous rocks such as sandstone and shale. Chemical alteration (dominant in long-term immersion): Mineral dissolution: Water dissolves cementing materials at grain boundaries (e.g., calcite, clay minerals), directly weakening cohesion. Ion exchange reactions: Active ions (K⁺, Na⁺) in feldspars react with water to form softer secondary minerals like kaolinite, further compromising grain boundary strength. Microscale damage mechanisms: Water wedge effect at crack tips: Water penetrates crack tips under impact, generating additional tensile stress. Mineral expansion: Rocks containing swelling minerals (e.g., montmorillonite) experience volume expansion at grain boundaries during long-term immersion, promoting microcrack growth. Engineering implications: A critical stability warning for rocks suggests that underground reservoirs, slopes, and tunnels in areas with fluctuating water levels are prone to impact-induced collapses after heavy rainfall, a direct consequence of water-weakened grain boundaries. Conversely, this principle can be leveraged to optimize blast efficiency in mining; pre-wetting hard rock layers deliberately weakens grain boundaries, thereby improving fragmentation and lowering explosive energy consumption. For long-term projects like nuclear waste repository siting, it is essential to avoid rock layers containing expansive minerals to prevent long-term water immersion from causing intergranular instability around the storage chambers

As shown in Fig. 14, the proportion of transgranular (through-grain) fractures in sandstone increases with rising impact velocity. This trend is mainly attributed to several factors: Stress wave intensity and strain rate effects: Higher impact velocity increases instantaneous energy: Greater impact speeds impart more energy to sandstone in a very short time, producing stress waves with higher amplitudes (stress peaks). Quartz, the main hard mineral in sandstone, will be directly fractured when the stress peaks significantly exceed its strength limit. At this stage, cracks are less likely to bypass the grains (intergranular fracture) and more likely to penetrate the strong quartz grains themselves (transgranular fracture).

Strain rate influence: High-speed impacts involve extremely high loading rates. At high strain rates: Cementing material hardening: The cements (e.g., calcite, clay, silica) in sandstone are normally softer than quartz. Under very high loading rates, these materials show significant strain rate hardening, and their dynamic strength may approach or exceed quartz’s static strength, making the cements no longer the “weakest link.”39,40 Quartz brittleness increase: Quartz itself becomes more brittle under high strain rates, favoring brittle transgranular cracking over plastic deformation or intergranular separation. Crack tip path limitation: At extreme loading rates, cracks propagate so rapidly that they cannot “choose” the energetically easier path along grain boundaries, instead extending along the direction of maximum stress, directly through the grains. Higher energy input:

Energy-intensive transgranular fractures: Compared to intergranular cracking along weaker grain boundaries, direct transgranular fractures consume more energy because breaking strong chemical bonds (Si–O bonds in quartz) requires substantial energy. The high energy input from rapid impacts is sufficient to make transgranular fracture dominant. Stress state and inertia effects: Complex dynamic stress field: High-speed impacts generate highly complex local stress states (high pressure and shear), concentrating stress within grains. Inertia effects: At extreme velocities, inertia of mineral grains hinders crack deflection along boundaries, promoting more linear or direct crack paths and increasing the likelihood of transgranular fracture. Thermal effects (at extreme speeds):

Very high impact velocities may locally generate significant heat, slightly altering sandstone’s mechanical response. Although thermal softening could reduce strength, the overwhelming effects of high pressure waves and phase transformations dominate, and the energy available still supports transgranular fracture formation. In summary, higher impact velocities favor transgranular fracture due to the combined influence of extreme stress, high strain rate, increased energy input, complex stress states, inertia, and, in extreme cases, local thermal effects.

Conclusions

-

1.

Microstructure evolution: SEM, NMR and CT analyses indicate that the internal structure of dry sandstone is intact, with low porosity and almost no cracks. As the immersion time increases, the internal structure gradually transitions from being complete to becoming increasingly porous. Correspondingly, the pH value of the soaking solution first increased and then decreased, and the total dissolved solid solution (TDS) increased over time.

-

2.

Energy transmission under dynamic loading: High impact velocities generate stress waves with higher frequencies and amplitudes. These high-frequency waves are more easily scattered and absorbed by microcracks, pore fluids, and mineral grain interfaces, causing significant attenuation of reflected energy. Long-term water immersion gradually fills sandstone pores with water, increasing pore saturation. The replacement of air by water reduces impedance contrasts within the rock, lowering the reflection coefficient of incident waves at interfaces.

-

3.

Fracture complexity and fractal characteristics: Higher impact velocities lead to more intense fragmentation and a more complex crack network. As immersion time increases, hydrophilic minerals such as montmorillonite expand, generating swelling stresses that press against surrounding mineral grains and induce microcracks. The fractal dimension of sandstone generally increases with immersion time and eventually stabilizes.

-

4.

Intergranular weakening and fracture mode evolution: Water progressively weakens grain boundaries, making cracks more prone to propagate along these boundaries. Longer water immersion leads to a higher proportion of intergranular fractures under impact loading. Under high-speed impacts, cementing materials exhibit relative strengthening; normally weaker than quartz grains, these cements resist deformation more effectively at high strain rates. Consequently, as impact velocity increases, the proportion of transgranular fractures in sandstone rises.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Reference

Amir Raza, M. et al. Global progress towards the Coal: Tracking coal reserves, coal prices, electricity from coal, carbon emissions and coal phase-out. Gondwana Research 139, 43–72 (2025).

Ren, W.-X., Guo, Q. & Yang, H.-H. Analyses and prevention of coal spontaneous combustion risk in gobs of coal mine during withdrawal period. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 10, 353–367 (2018).

Zhao, J. & Konietzky, H. An overview on flooding induced uplift for abandoned coal mines. Int. J. Rock Mech. Mining Sci. 148, 104955 (2021).

Bai, X. et al. Microscopic phase evolution mechanism of lithium slag and fiber synergistically enhancing concrete toughness: perspective of preventing coal-rock dynamic disasters through energy absorption. Int. J. Mining Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2025.06.007 (2025).

Yao, Q. et al. Mechanisms of failure in coal samples from underground water reservoir. Eng. Geol. 267, 105494 (2020).

Fan, K.-F., Xie, P. & Liu, Z.-C. Analytical method of reservoir capacity of underground reservoir in coal mine: a case study. Water Supply 23, 581–598 (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. Creep behavior and permeability evolution of coal pillar dam for underground water reservoir. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 10, 11 (2023).

Zhang, H. et al. Water quality characteristics and water-rock interaction mechanisms of coal mine underground reservoirs. ACS Omega 9, 28726–28737 (2024).

Wen, Z. et al. Structural model and capacity determination of underground reservoir in goaf: a case study of Shendong mining area in China. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 9, 143 (2023).

Lyu, X. et al. Experimental study of mechanical properties of artificial dam for coal mine underground reservoir under cyclic loading and unloading. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 10, 91 (2024).

Lu, H. et al. Dynamic mechanical properties and damage evolution characteristics of beishan deep granite under medium and high strain rates. Materials (Basel) 16, 5235 (2023).

Du, W., Zhang, D. & Yu, B. Mechanical and fractal characteristics of sandstone with Pre-existing fissures of different lengths under varying impact loads in SHPB tests. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 125, 103884 (2023).

Li, J. C. et al. An SHPB test study on stress wave energy attenuation in jointed rock masses. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 52, 403–420 (2018).

Du, H.-B. et al. Numerical investigation on the dynamic strength and failure behavior of rocks under hydrostatic confinement in SHPB testing. Int. J. Rock Mech. Mining Sci. 108, 43–57 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Experimental research on energy evolution of sandstone with different moisture content under uniaxial compression. Sustainability 16, 4636 (2024).

Liang, X., Tang, S., Tang, C. & Wang, J. The influence of water on the shear behaviors of intact sandstone. Bullet. Eng. Geol. Environ. 80, 6077–6091 (2021).

Wang, K. et al. Dynamic behaviour and failure mechanism of coal subjected to coupled water-static-dynamic loads. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 153, 107084 (2022).

Feng, F. et al. Influence of moisture content and intermediate principal stress on cracking behavior of sandstone subjected to true triaxial unloading conditions. Eng. Fract. Mech. 284, 109265 (2023).

Zhang, C. et al. Acoustic emission and splitting surface roughness of sandstone in a Brazilian splitting test under the influence of water saturation. Eng. Geol. 329, 107369 (2024).

Chen, Y., Kang, T. & Wu, C. Study on mechanical behavior and mechanism of sandstone under the coupling effect of water content and dynamic load. Processes 11, 2318 (2023).

Xu, J., Pu, H. & Sha, Z. Dynamic mechanical behavior of the frozen red sandstone under coupling of saturation and impact loading. Appl. Sci. 12, 7767 (2022).

Kong, F., Li, X., Peng, X. & Wang, R. Underlying mechanism behind the dynamic mechanical behavior of sandstone with varying moisture content under medium speed impact. Sci. Rep. 15, 5700 (2025).

Yin, T. et al. Dynamic mechanical response and damage constitutive model of end-jointed rock bridge with different water content states under impact load. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 130, 104255 (2024).

Zhang, A. et al. Mechanical responses in rocks with different lithologies under mining loading–unloading: an insight by energy damage and ultrasonic characterization. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 57, 10047–10069 (2024).

Wu, Z. et al. Investigation on physico-mechanical properties and microstructural evolution patterns of heated granite after liquid nitrogen cooling. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 9, 172 (2023).

Li, M. et al. Nonlinear mechanical and 3D rupture morphology of saturated porous sandstone under true triaxial stress. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 57, 6837–6859 (2024).

Li, C. et al. Anisotropic fracture evolution and size effect of the fracture process zone in laminated shales derived from digital image correlation. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 58, 203–224 (2024).

Qiao, H. et al. Evolution of pore structure and fractal characteristics in red sandstone under cyclic impact loading. Fractal Fract. 8, 437 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. Dynamic response and energy evolution of sandstone under combined dynamic and static loading. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 174, 108168 (2023).

Fan, W. et al. study on the mechanical behavior and constitutive model of layered sandstone under triaxial dynamic loading. Mathematics 11, 1959 (2023).

Fan, W. et al. Effects of layering angle and prestress on dynamic load energy conversion and damage mechanism of sandstone. Processes 11, 2641 (2023).

Fan, W. et al. Study on dynamic loading characteristics and energy evolution of sandstone with double cracks. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 125, 103893 (2023).

Fan, W. et al. Tensile fracture behaviour of stratified sandstone under static and dynamic loading. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 58, 4849–4877 (2025).

H. Zhang, W. Sun, Q. Xie, Y. Chen, Z. Tu, Y. Ban, Study on mechanical properties and damage characteristics of acid corrosion in granite based on NMR technology, Engineering Geology, 340 (2024).

Han, P., Zhang, C., Wang, X. & Wang, L. Study of mechanical characteristics and damage mechanism of sandstone under long-term immersion. Eng. Geol. 315, 107020 (2023).

Han, P., Zhao, Y., Zhang, C. & Wang, X. Progressive damage characteristic and microscopic weakening mechanism of coal under long-term soaking. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 56, 7861–7881 (2023).

Xie, H., Zhu, J., Zhou, T. & Zhao, J. Novel three-dimensional rock dynamic tests using the true triaxial electromagnetic hopkinson bar system. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 54, 2079–2086 (2021).

Zhang, JW, WB. Fan, and Yang, Y et al. Dynamic response and energy evolution of sandstone under combined dynamic and static loading. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering. 174 (1), 1-1 (2023)

Feng, Dai et al. Some fundamental issues in dynamic compression and tension tests of rocks using split hopkinson pressure bar. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 43, 657 (2010).

Zhang, Q. B. & Zhao, J. A Review of dynamic experimental techniques and mechanical behaviour of rock materials. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 47(4), 1411–1478 (2014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiaowei Gu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software; Chujian Han: Data curation, Writing- Original draft preparation. Xiaochuan Xu: Visualization, Investigation. Jianan Wang: Supervision. Zhenguo Zhu and li Chao: Software, Validation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gu, X., Han, C., Xu, X. et al. Dynamic behavior and micro–meso scale fracture mechanisms of sandstone under long-term water immersion. Sci Rep 16, 1920 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31733-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31733-4