Abstract

This study addresses the clinical challenge of nonunion in spinal interbody fusion by developing a novel composite implant: a porous tantalum (PTa) cage loaded with concentrated growth factors (CGF). The CGF-PTa cage synergistically combines the mechanical strength and osteoconductivity of chemically vapor-deposited PTa with the sustained release of angiogenic (VEGF) and osteogenic (TGF-β and IGF-1) factors from CGF. Using a rat extreme lateral interbody fusion (XLIF) model, the research systematically evaluates the efficacy of this composite in promoting bone regeneration and spinal fusion. Results from radiography, micro-CT, biomechanical testing, histological staining, and immunohistochemistry consistently show that CGF-PTa significantly enhances bone ingrowth, fusion rate, and mechanical stability compared to PTa alone. The findings also reveal that CGF facilitates angiogenesis and osteogenesis by modulating the local healing microenvironment and promoting vascular–osteogenic coupling. Importantly, the CGF-PTa system demonstrated excellent biocompatibility and biodegradability in vivo, with no observed systemic toxicity. This work highlights the potential of combining bioactive factors with porous metallic scaffolds to overcome the limitations of inert implants in avascular environments, offering a promising strategy for functional optimization of interbody fusion devices and their future clinical application.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the accelerating global trend of population aging, the incidence of lumbar degenerative diseases such as lumbar disc herniation, spinal stenosis, and spondylolisthesis has significantly increased, posing major challenges to healthcare systems worldwide1. These conditions are often accompanied by persistent low back pain and progressive neurological dysfunction. When conservative treatments fail, surgical intervention becomes necessary2. Interbody fusion, a key surgical technique for managing degenerative spinal disorders, aims to restore spinal stability and relieve nerve compression. However, its long-term efficacy remains limited by complications such as pseudarthrosis and nonunion3. Currently, autologous bone grafting is considered the gold standard for interbody fusion due to its superior osteoconductive and osteoinductive properties. Nevertheless, its clinical application is restricted by donor site pain, infection, and limited bone availability4. Moreover, the surgical approach significantly influences the feasibility of harvesting autologous bone.

Unlike traditional posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF), lateral approaches such as XLIF avoid extensive resection of posterior bony structures, making it difficult to obtain sufficient autologous graft material. Surgeons often resort to harvesting bone from distant sites such as the iliac crest, which increases operative time and the risk of donor-site complications. Under such circumstances, allogeneic bone grafting is also widely used as an alternative approach, but it carries risks of immune rejection and disease transmission, and generally exhibits weak osteoinductive properties5. These clinical limitations have spurred the development of biomaterials for spinal fusion. Among them, PTa has emerged as a promising candidate owing to its excellent biocompatibility, corrosion resistance, and an elastic modulus similar to that of cancellous bone6. The elastic modulus of PTa is approximately 3–4 GPa, closely matching cancellous bone and thus mitigating issues such as stress shielding and implant subsidence commonly observed with conventional titanium-based implants7. Furthermore, PTa fabricated via CVD can achieve a porosity of 75–80%, and its interconnected three-dimensional structure facilitates cellular adhesion and bone tissue ingrowth8,9,10. In fact, osteoconduction and osteoinduction are two essential characteristics of bone implants11. While CVD-derived PTa possesses excellent osteoconductivity due to its structural and material properties, its bioinert nature limits its capacity to actively induce bone formation. Studies suggest that ideal porous implants should incorporate bioactive cells or growth factors to promote both angiogenesis and osteogenesis12. Therefore, enhancing the osteoinductive capacity of PTa is crucial for its application in interbody fusion, especially given the avascular and complex microenvironment of the interbody space.

Concentrated Growth Factor (CGF), representing the third generation of autologous platelet concentrates, are enriched with multiple growth factors such as VEGF, PDGF, TGF-β, and IGF-1, which play essential roles in angiogenesis and osteogenic differentiation13,14. Produced via a variable-speed centrifugation process, CGF forms a dense, cross-linked fibrin matrix with a three-dimensional network structure. This matrix acts as an ideal biological carrier for growth factors, allowing for sustained, sequential release during degradation15. Previous studies have shown that CGF’s fibrin network enables a controlled release of growth factors for up to 14 days, thereby maintaining a stable local concentration gradient essential for tissue regeneration16,17. This “high-concentration reservoir–programmed release” mechanism makes CGF a highly effective autologous biomaterial for promoting tissue regeneration and vascularization18,19. Previous studies have quantitatively analyzed the concentrations of major growth factors in CGF. Qiao et al. (Platelets, 2017) reported that CGF contains significantly higher levels of PDGF-BB (175.10 ± 57.09 ng/mL), TGF-β1 (584.89 ± 292.50 ng/mL), IGF-1 (321.42 ± 150.30 ng/mL), and VEGF (238.14 ± 149.89 pg/mL) compared with platelet-poor plasma20. As a result, CGF has been widely applied in oral and maxillofacial surgery, plastic and reconstructive procedures, wound healing, and bone defect repair21,22,23.

In theory, the combination of CGF’s osteoinductive potential with PTa’s osteoconductive structure can provide a physical cage for cell adhesion while delivering bioactive factors that promote angiogenesis and bone healing, thereby enhancing interbody fusion. However, such a strategy remains underexplored in the context of spinal fusion. In particular, the regulation of the “angiogenesis–osteogenesis coupling” mechanism to improve fusion outcomes warrants further investigation. We hypothesize that the biological activity of CGF can complement the bioinertness of PTa to synergistically enhance osteogenesis and vascularization, ultimately improving fusion rates and reducing the time required for spinal fusion.Therefore, this study proposes an innovative approach by combining PTa and CGF to fabricate a dual-functional composite cage capable of simultaneously promoting bone regeneration and neovascularization. The efficacy of this cage in facilitating interbody fusion was systematically evaluated in a rat XLIF model (Fig. 1), offering a novel strategy for optimizing interbody fusion cage design and advancing the treatment of degenerative spinal diseases.

Preparation process and biological functional mechanism of the CGF-PTa cage. Whole blood was centrifuged through a variable-speed program to obtain three distinct layers: platelet-poor plasma (PPP), concentrated growth factors (CGF), and red blood cells (RBCs). The CGF gel was then vacuum-perfused into the porous tantalum (PTa) cage to form a composite structure (CGF-PTa). After implantation into the intervertebral space, CGF gradually degraded and continuously released angiogenic and osteogenic growth factors (e.g., VEGF, TGF-β, IGF-1), promoting vascular ingrowth and osteogenesis within the PTa scaffold. This synergistic effect enhanced the coupling of angiogenesis and osteogenesis, thereby facilitating interbody fusion. Abbreviations: PPP, platelet-poor plasma; RBC, red blood cell; CGF, concentrated growth factors; PTa, porous tantalum.

Materials and methods

Animal source, care, ethics statement, and euthanasia

In this study, 48 male Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats (3 months old, weighing 350 ± 50 g; sourced from the Animal Experiment Center of Hebei Medical University, China) were used. The rats were housed individually in an enriched environment under a 12-hour light/dark cycle with free access to food and water. After 2–3 days of acclimatization, all experiments were performed at the Animal Experiment Center of the Third Hospital of Hebei Medical University and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Third Hospital of Hebei Medical University (approval number: Z2024-057-1). All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health, USA) and relevant institutional, national, and international regulations. The reporting of animal experiments adhered to the ARRIVE guidelines (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments). The animals were randomly assigned to experimental groups using a computer-generated randomization method to minimize selection bias. They were divided into two groups: the PTa group (n = 24) and the CGF-PTa group (n = 24). Each group was further evaluated at two postoperative time points (4 weeks and 8 weeks), with 12 rats per group at each time point. At each time point, all 12 rats underwent radiographic (X-ray) examination and manual palpation to assess interbody fusion. Six rats were randomly selected for micro-CT analysis, three rats were randomly selected for non-destructive biomechanical testing, six rats were randomly selected for undecalcified hard-tissue sectioning with Van-Gieson staining, and six rats were randomly selected for immunohistochemical analysis. The biomechanical testing was non-destructive, allowing these specimens to be reused for subsequent histological and IHC analyses without affecting the total sample size. At the end of the study, all rats were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital and phenytoin sodium (100 mg/kg).

Fabrication of the PTa interbody fusion cage

The PTa interbody fusion cages were fabricated using the classical CVD technique developed by Implex-Zimmer. Based on the anatomical data of rat lumbar vertebrae, customizedcages were designed and manufactured. The fabrication process included the following steps: open-cell polyurethane foam with pore sizes ranging from 400 to 600 μm and a total porosity of ~ 80% was first degreased and resin-infiltrated, then pyrolyzed at 950 °C in an inert atmosphere to form a three-dimensional reticulated vitreous carbon (RVC) skeleton. Tantalum sponge was chlorinated at ~ 330 °C in a Cl₂ atmosphere to produce volatile TaCl₅. The reduction reaction 2TaCl₅ + 5 H₂ → 2Ta + 10HCl was carried out at 980–1030 °C, 2–8 Torr, and ≥ 92 vol% H₂. Tantalum atoms were uniformly deposited along the pore walls for 60 min, forming a pure tantalum layer (~ 80 μm thick). This process resulted in a trabecular-like architecture, resembling the sponge-like structure of cancellous bone, with a dodecahedral lattice topology, which refers to a repeating three-dimensional pattern made up of twelve interconnected faces. The structure consists of 98 wt% Ta and 2 wt% RVC. After deposition, the samples were cooled under inert gas, ultrasonically cleaned to remove residual chlorine, and subjected to vacuum annealing at 300 °C for 30 min and 1000 °C for 60 min to release residual stress and densify the tantalum layer. Final cleaning was performed sequentially using acetone, anhydrous ethanol, and ultrapure water. The qualified PTa blocks were provided by Zimmer Biomet and subsequently cut using Wire-cut machining into rectangular shapes (3.5 mm × 1 mm × 1 mm) suitable for implantation in the rat spine.

Preparation of CGF

CGF was prepared according to a previously established protocol. Approximately 7 mL of whole blood was collected from the hearts of rats under isoflurane anesthesia into sterile glass tubes without anticoagulants. A specialized centrifuge with a variable-speed program was used for separation: initial acceleration for 30 s, followed by 2 min at 2700 rpm (600 g), 4 min at 2400 rpm (500 g), another 4 min at 2700 rpm, and 3 min at 3000 rpm (800 g), ending with deceleration over 36 s. The resulting layers were: top—platelet-poor plasma (PPP), middle—CGF gel, and bottom—red blood cells (RBCs). It is important to note that in clinical practice, CGF is typically derived from autologous blood to avoid immunological incompatibility and ensure safety. However, in this study, due to the limited blood volume in rats, we used allogeneic blood for CGF preparation, as it was not possible to obtain sufficient peripheral blood from individual rats.

Preparation of CGF-PTa interbody fusion cage

To ensure uniform distribution and surface coverage of gel-form CGF within the PTa cage, the following procedure was performed. The cage was first ultrasonically cleaned in acetone, anhydrous ethanol, and ultrapure water for 15 min each. Surface hydrophilicity was then enhanced using low-temperature oxygen plasma treatment (50 W, 5 min). During vacuum perfusion, the pretreated PTa cage was placed in a sterile chamber. An initial vacuum of − 0.03 MPa was applied for 10 s to remove air from the pores, followed by the slow addition of CGF gel. The vacuum was increased to − 0.06 MPa and maintained for 10 min to promote deep infiltration. Finally, the cage was tilted at a 45° angle under atmospheric pressure and slowly rotated to ensure even distribution of excess surface CGF. The construct was left undisturbed for 10 min to allow stable deposition within the cage.

Characterization of the CGF-PTa interbody fusion cage

The surface morphology and porous microstructure of PTa and CGF-PTa cages were observed under a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Hitachi SU-8100, Japan) after gold sputter-coating, with accelerating voltage set at 20 kV and magnifications ranging from ×50 to ×20,000.To evaluate the sustained release profile of the CGF-PTa cage, ELISA was used to detect the concentrations of growth factors released over time. Cages loaded with CGF were immersed in 3 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and samples were collected and replaced at predefined time points (days 1, 3, 5, 7, and 14). Concentrations of VEGF, IGF-1, and TGF-β were measured, and release curves were plotted accordingly.

Animal model and surgical procedures

This study employed the novel rat XLIF interbody fusion model that our team has successfully established24. A total of 48 male SD rats (3 months old, 350 ± 50 g) were randomly assigned to the PTa group or the CGF-PTa group. Anesthesia was induced with 5% isoflurane at a flow rate of 300 mL/min and maintained at 2% isoflurane. Anesthetic depth was monitored and adjusted by assessing tail, ear, and limb responses to pinch stimuli. After successful anesthesia, the rats were placed in the right lateral decubitus position, and the lumbar region was shaved and disinfected. The L4–L5 interbody space was located based on the iliac crest level, approximately corresponding to the surface projection of the sixth lumbar vertebra. A 4 cm arcuate skin incision was made approximately 3–4 cm lateral to the midline on the left flank. The external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis muscles were sequentially dissected to expose the quadratus lumborum and retroperitoneal fat. The retroperitoneal space was bluntly dissected to reach the dorsal side of the psoas major and the iliolumbar vessels, which were ligated. The retroperitoneal fat was retracted using saline-soaked gauze to expose the anterior-lateral border of the L4–L5 disc along the level of the L5 vertebral body. The annulus fibrosus was incised, and the nucleus pulposus was thoroughly removed. The cartilaginous endplates were scraped until punctate bleeding was observed. The PTa or CGF-PTa cage was then implanted, followed by lateral fixation of the L4–L5 segment using a titanium plate. After confirming adequate hemostasis, the surgical layers were closed in sequence, and the wound was covered with sterile dressing. Postoperative care included intraperitoneal injection of penicillin sodium (8U) for three consecutive days. Rats were monitored closely for neurological function and wound healing.

Radiography

Lateral radiographs of the lumbar spine were obtained postoperatively to assess implant displacement or subsidence. Fusion status was evaluated radiographically using a modified Bridwell grading system based on postoperative X-ray images. All grading was performed independently by two blinded spinal surgeons. The criteria were as follows: Grade 0, No new bone formation; no visible bone bridging across the disc space; Grade 1, New bone formation present, but no continuous bone bridge; Grade 2, Partial but evident bone bridging, with clear fusion progression; Grade 3, Continuous and uniform bone bridge formation between adjacent vertebral bodies, indicating complete radiographic fusion.

Manual palpation examination

At postoperative weeks 4 and 8, rats were euthanized, and surrounding muscles and ligaments were removed to harvest spinal segments. After removing all internal fixation hardware, the L4–L5 fusion segment and adjacent levels were manually assessed for mobility by two blinded spinal surgeons. Flexion, extension, lateral bending, and rotation were performed to evaluate motion between segments. Segments exhibiting no obvious movement were classified as fused; Segments with visible mobility were classified as non-fused. Manual palpation results were used as a supplemental assessment of fusion and were analyzed in conjunction with radiographic scoring.

Micro-CT measurement

At postoperative weeks 4 and 8, six samples from each group were randomly selected for high-resolution micro-CT imaging (SkyScan 1176, Bruker, Germany). The scanning parameters were set as follows: resolution of 18 μm, X-ray tube voltage of 65 kV, current of 385 µA, and exposure time of 340 ms per projection for a complete 360°rotation scan.Reconstruction was performed using Dataviewer and 3D visualization using CTvox. The interbody fusion region was defined as the region of interest (ROI), and 3D bone microstructural parameters were quantified using CTAn software: Bone volume to total volume (BV/TV), Bone surface to total volume (BS/TV), Trabecular number (Tb.N), Trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), Trabecular separation (Tb.Sp) and Bone mineral density (BMD).

Biomechanical evaluation

The biomechanical testing was conducted following a modified protocol based on Reference25. Spinal segment stiffness was evaluated by measuring displacement distance using an Instron 5543 mechanical testing system (INSTRON, Norwood, MA, USA) equipped with a cantilever loading setup. Following micro-CT scanning, three specimens per group were selected and prepared by removing surrounding soft tissues, titanium plates, and screws, while preserving discs, ligaments, and joint capsules. Screws were inserted into the cranial and caudal vertebrae and fixed in polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA). A PMMA loading block was adhered to the superior surface of L4 and connected to the testing apparatus. The loading parameters were set at 22 N·mm torque with a 22 mm moment arm, and a 1 N load was applied to the cement block through the loading head. Flexion, extension, and left/right lateral bending were tested with 30 s relaxation between cycles. Each specimen underwent three loading cycles; stiffness values were calculated from the final cycle and reported as N·mm/°.

Histological analysis

To evaluate bone regeneration within the fusion zone, undecalcified sections of bone were prepared and stained with Van-Gieson. At weeks 4 and 8 postoperatively, spinal specimens were harvested and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated, and embedded in resin. Sections (~ 30 μm thick) were prepared using a cutting-grinding system and stained with Van-Gieson. Digital microscopy (DSX 500, Olympus, Japan) was used for imaging. ImageJ software was used for semi-quantitative analysis of new bone area within the cage (defined ROI). A uniform color threshold was set to identify mineralized bone and calculate its area fraction within the ROI.

Immunohistochemistry

Bone tissues surrounding the interbody fusion cage were harvested at 4 and 8 weeks post-operation. Immunohistochemical staining was performed to detect the relative expression of CD31, VEGF, OCN, and RUNX2 in bone tissues at the interbody fusion sites, evaluating osteogenic activity and angiogenesis in each group. Tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, decalcified in 10% EDTA for 3 weeks, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned at 5 μm. Sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies (Servicebio, China), followed by HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG as the secondary antibody. Immunoreactive cells were identified by brown cytoplasmic staining and counterstained with hematoxylin. Positive cell counts were recorded under a light microscope.

Degradability and local biocompatibility of CGF

Twelve 3-month-old male SD rats were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane and subcutaneously injected with 0.5 g of gel-form CGF in the dorsal region. Rats were randomly divided into four groups (n = 3 per time point) and euthanized at days 0, 3, 7, and 14. Residual CGF was harvested and weighed (Wt) to calculate degradation rate: Degradation rate (%) = (Wa − Wt)/Wa×100%, where Wa = initial CGF weight (0.5 g). Adjacent skin tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histological examination to assess local biocompatibility.

Biocompatibility assay

At 8 weeks post-surgery, rats were euthanized, and major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lungs, kidneys) were collected. Tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with H&E. Histological evaluation was performed to detect any systemic toxicity or pathological alterations resulting from cage implantation.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 26.0 software (IBM, USA). Normality of data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. For normally distributed data, parametric tests (t-test) were used; otherwise, the Mann–Whitney U test was applied. For categorical variables, group comparisons were conducted using Fisher’s exact test. All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), with statistical significance defined as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

Results

Characterization of the CGF-PTa interbody fusion cage

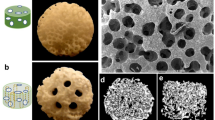

As shown in Fig. 2a, centrifugation of autologous rat blood resulted in three distinct layers: the upper layer was PPP, the middle layer was CGF, and the bottom layer consisted of RBCs. The extracted CGF gel appeared translucent. SEM revealed that CGF exhibited a dense fibrin matrix interwoven with platelets and red blood cells.

Figure 2a displays the macroscopic view of the CVD-fabricated porous cage prepared according to rat lumbar anatomical measurements. The prepared PTa fusion device demonstrates intact overall architecture and surface morphology without observable manufacturing defects or cracks. SEM imaging confirmed that the porous cages exhibited a trabecular-like, dodecahedral lattice topology derived from RVC composite, with a porosity of approximately 80% and an average pore diameter of 440 μm. The cage columns showed uniform, continuous 3D interconnected pores, morphologically resembling cancellous bone, and featured micron-to-nanoscale surface roughness (Fig. 2b). No unmelted particles or structural irregularities were observed, and the pore sizes matched macroscopic measurements. It is generally accepted that pore diameters of 300–500 μm and porosity of 75–90% are optimal for bone ingrowth. In this study, the pore size and porosity of the PTa metal cage were 440 μm and 80%, respectively. As shown in the Fig. 2b, the CGF gel can uniformly fill the pore structure of the PTa metal cage. The local magnified SEM image shows that under negative pressure perfusion conditions, the CGF gel can penetrate deep into the internal pores of the cage and still maintain a dense and uniform fibrous network structure in the deep area.

The ELISA results indicated that the angiogenic and osteogenic-related factors VEGF, TGF-β, and IGF-1 were continuously released within 14 days (Fig. 2c). This indicated that CGF provides sustained delivery of bioactive factors, aligning with the prolonged and complex process of bone regeneration. Previous studies have described a biphasic release pattern from CGF: an initial burst release due to platelet activation and free diffusion, followed by a sustained release governed by gradual fibrin network degradation26. To further elucidate the release behavior of key growth factors (VEGF, TGF-β, and IGF-1) from the CGF-PTa scaffold, we additionally analyzed the daily release curves and the total release data for each factor (Fig. S1, Table S1).

Characterization of the CGF-PTa cage. (a) Photographic and SEM images of CGF gel, along with the interbody fusion cage (3.5 mm × 1 mm × 1 mm) used for in vivo experiments. (b) Scanning electron microscopy images of the PTa cage and the CGF-PTa cage. (c) Cumulative release profiles of TGF-β, IGF-1, and VEGF from the CGF-loaded PTa cage (n = 3).

X-ray imaging and assessment of interbody fusion

To evaluate fusion efficacy, lateral X-ray imaging was performed at predefined time points in all 48 SD rats (Fig. 3a). No signs of cage displacement or subsidence were observed in any animals, and the titanium plates and screws remained intact without evidence of fracture, deformation, or loosening. Over time, both the PTa and CGF-PTa groups exhibited progressive formation of new bone bridging anterior and posterior to the cage, integrating with adjacent vertebral bodies (Fig. 3b). According to the modified Bridwell scoring system, at 4 weeks postoperatively, the mean fusion scores were 0.92 ± 0.63 in the PTa group and 1.42 ± 0.63 in the CGF-PTa group. Although the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.164), the CGF-PTa group showed a trend toward higher fusion grades. At 8 weeks, fusion scores increased to 2.25 ± 1.11 in the PTa group and 2.75 ± 0.35 in the CGF-PTa group; however, the difference remained statistically non-significant (p = 0.182) (Table 1).

Experimental design of the SD rat interbody fusion model and X-ray based fusion score analysis. (a) Schematic illustration of the surgical and analytical procedures for the rat interbody fusion model. (b) Representative X-ray images obtained immediately postoperatively and at 4 and 8 weeks after surgery. (c) Modified Bridwell scoring analysis of interbody fusion outcomes at 4 and 8 weeks postoperatively in SD rats.

Despite the lack of statistical significance, the CGF-PTa group exhibited a higher proportion of Grade 3 fusions (complete bony bridging) at both time points, indicating a more robust fusion trend (Fig. 3c). The non-significant results may be attributed to factors such as limited sample size (n = 12 per group), inter-animal variability in healing, and the semiquantitative nature of radiographic scoring, which can be subjective. Nevertheless, the CGF-PTa group consistently outperformed the PTa group in radiographic fusion scores, suggesting that CGF may facilitate enhanced spinal fusion. To further validate this observation, additional assessments, including manual palpation, micro-CT, biomechanical testing, and histological analysis, were conducted.

Manual palpation of interbody fusion

Manual palpation was performed at 4 and 8 weeks postoperatively to assess spinal segment stability. At week 4, the complete fusion rate in the PTa group was 0.0% (0/12), whereas the CGF-PTa group showed a higher rate of 16.7% (2/12). By week 8, the fusion rate increased to 41.7% (5/12) in the PTa group and reached 91.7% (11/12) in the CGF-PTa group (Table 1). The trend observed in manual palpation results was consistent with the radiographic fusion scores, both showing time-dependent improvement in fusion status. Moreover, at both time points, the CGF-PTa group exhibited higher fusion rates than the PTa group. At week 4, the difference was not statistically significant, as determined by Fisher’s exact test (p = 0.478). However, at week 8, the intergroup difference reached statistical significance (p = 0.027), indicating that CGF loading significantly enhanced interbody fusion during the later stage of healing.

Micro-CT scanning and analysis

To further evaluate the osteogenic performance of the CGF-PTa cage in vivo, micro-CT was performed on harvested spinal segments at 4 and 8 weeks postoperatively. As shown in Fig. 4a, representative sagittal and coronal slices, along with 3D reconstructions, demonstrated new bone formation at the L4–L5 interbody fusion site in both groups. At 4 weeks, preliminary bone ingrowth was observed in both the PTa and CGF-PTa groups, with the CGF-PTa group showing a more robust bone healing trend, although continuous fusion had not yet been achieved. At 8 weeks postoperatively, both groups demonstrated more evident new bone formation compared to the 4-week time point, and a stable bridging union across the interbody space had formed. Notably, the CGF-PTa group exhibited significantly superior bone tissue regeneration than the PTa group. To quantify the micro-CT findings, bone microarchitectural parameters including BV/TV, BS/TV, Tb.Th, Tb.N, Tb.Sp, and BMD were analyzed (Fig. 4b). The results showed that both groups exhibited a general trend of improvement in bone structural parameters as the healing process progressed over time. Statistically significant enhancements were observed in BV/TV (PTa: 4w, 5.06 ± 0.59% vs. 8w, 9.54 ± 0.85%, p < 0.001; CGF-PTa: 4w, 7.04 ± 0.55% vs. 8w, 14.99 ± 0.83%, p < 0.001), Tb.Th (PTa: 4w, 0.02 ± 0.01 mm vs. 8w, 0.04 ± 0.01 mm, p < 0.001; CGF-PTa: 4w, 0.03 ± 0.01 mm vs. 8w, 0.05 ± 0.01 mm, p < 0.001), Tb.N (PTa: 4w, 1.26 ± 0.08 1/mm vs. 8w, 2.86 ± 0.26 1/mm, p < 0.001; CGF-PTa: 4w, 1.56 ± 0.16 1/mm vs. 8w, 3.24 ± 0.28 1/mm, p < 0.001), Tb.Sp (PTa: 4w, 0.43 ± 0.03 mm vs. 8w, 0.35 ± 0.03 mm, p < 0.001; CGF-PTa: 4w, 0.43 ± 0.04 mm vs. 8w, 0.30 ± 0.03 mm, p < 0.001) and BMD (PTa: 4w, 0.36 ± 0.03 g/cm³ vs. 8w, 0.90 ± 0.10 g/cm³, p < 0.001; CGF-PTa: 4w, 0.51 ± 0.04 g/cm³ vs. 8w, 1.11 ± 0.06 g/cm³, p < 0.001). For BS/TV, a significant increase was observed in the PTa group from 12.00 ± 0.68 1/mm at 4 weeks to 14.65 ± 0.76 1/mm at 8 weeks (p < 0.001). In contrast, no statistically significant change was found in the CGF-PTa group, where BS/TV increased from 11.27 ± 1.00 1/mm to 12.12 ± 0.71 1/mm (p = 0.121).

To further determine whether the CGF-PTa group exhibited an improving trend in bone fusion quality over time, intergroup comparisons between the PTa and CGF-PTa groups were conducted at different time points. At 4 weeks, although both groups showed similar trends in BV/TV, Tb.Th, and BMD, the CGF-PTa group demonstrated significantly greater improvements in all three parameters (p < 0.001). In addition, Tb.N in the CGF-PTa group (1.56 ± 0.16 1/mm) was significantly higher than that in the PTa group (1.26 ± 0.08 1/mm, p < 0.01). In fact, these differences became more pronounced by week 8. Compared to the PTa group, the CGF-PTa group exhibited significantly higher values in BV/TV, BS/TV, Tb.Th, Tb.N, Tb.Sp, and BMD (p < 0.001). Notably, BMD remained significantly elevated in the CGF-PTa group (p < 0.01), further supporting the enhancement of bone quality. Even for parameters such as Tb.N (p < 0.05) and Tb.Sp (p < 0.05), which showed smaller absolute differences, the CGF-PTa group still demonstrated statistically significant improvements. Taken together, these results suggest that the CGF-PTa cage significantly promotes new bone formation in vivo and exhibits progressively enhanced osteogenic performance over time. One limitation of this study is the potential influence of beam-hardening artifacts caused by the high-density PTa cage during micro-CT reconstruction, which may partially affect bone visualization despite the application of artifact-reduction algorithms.

Micro-CT evaluation of interbody fusion at 4 and 8 weeks postoperatively. (a) Representative µCT images of the L4–L5 segment, including sagittal CT slices, 3D reconstructed coronal views, 3D reconstructions of the cage region (gray indicates the PTa cage), and binarized images illustrating bone ingrowth within the cage. (b) Quantitative analysis of trabecular bone microarchitectural parameters, including BV/TV, BS/TV, Tb.Th, Tb.N, Tb.Sp, and BMD, in each group at 4 and 8 weeks postoperatively. (n = 6; data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Intergroup comparisons (PTa vs. CGF-PTa) and intragroup comparisons between different time points (4 W vs. 8 W) were both analyzed using independent-samples t-tests, as all data were normally distributed and based on independent samples. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.* indicates intergroup comparisons: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; # indicates intragroup comparisons between time points: #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001).

Biomechanical evaluation

Biomechanical testing of spinal specimens at 4 and 8 weeks postoperatively further demonstrated that with the progression of the fusion process, bone fusion quality was markedly improved by week 8. Moreover, the incorporation of CGF into the PTa cage significantly enhanced the interbody fusion strength compared to PTa alone (Fig. 5). At 4 weeks, compared with the PTa group, the PTa-CGF group exhibited a 54.74% increase in flexural stiffness. (13.37 ± 1.05 Nmm/Deg vs. 8.64 ± 1.37 Nmm/Deg, p < 0.01); An improvement of 39.45% in extension stiffness was also observed. (11.67 ± 1.18Nmm/Deg vs. 8.37 ± 1.06 Nmm/Deg, p < 0.05); During lateral bending, stiffness was improved by 18.54% (14.26 ± 1.00 N·mm/deg vs. 12.03 ± 1.42 N·mm/deg, p = 0.09) on the left side and by 23.92% (14.41 ± 1.13 N·mm/deg vs. 11.63 ± 1.30 N·mm/deg, p < 0.05) on the right side.At 8 weeks, compared with the PTa group, the PTa-CGF group exhibited a 32.45% improvement in flexion stiffness (26.46 ± 2.46 N·mm/deg vs. 19.97 ± 2.60 N·mm/deg, p < 0.05), and a 14.73% improvement in extension stiffness (21.27 ± 2.49 N·mm/deg vs. 18.54 ± 1.71 N·mm/deg, p = 0.192). During lateral bending, stiffness increased by 23.67% on the left side (25.52 ± 2.41 N·mm/deg vs. 20.63 ± 2.22 N·mm/deg, p = 0.061) and by 23.38% on the right side (25.34 ± 2.15 N·mm/deg vs. 20.54 ± 2.47 N·mm/deg, p = 0.064).

Biomechanical stiffness analysis to evaluate segmental stability of the operated lumbar spine at 4 and 8 weeks postoperatively. Comparison of stiffness between the CGF-PTa and PTa groups in (a) flexion/extension and (b) left/right lateral bending. (n = 3; data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical comparisons between experimental and control groups at each time point were performed using independent-samples t-tests. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.).

Osseointegration assessment by histomorphometry analysis

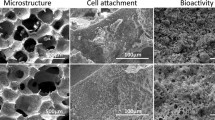

To assess the osteogenic performance of CGF-PTa, Van-Gieson staining was performed on bone tissue within the interbody fusion region (Fig. 6a). During the early phase of bone formation, new bone tissue began to grow along the surface of the tantalum cage from the surrounding bone. As the healing process progressed, bone gradually infiltrated the inner pores of the cage. Compared to the PTa group without CGF, the CGF-PTa group exhibited more rapid and evident bone ingrowth. At 4 weeks postoperatively, partial new bone formation was observed along the outer surface of the cage in the PTa group, while in the CGF-PTa group, early bone ingrowth into the internal pores of the cage was already evident. By 8 weeks, both groups showed substantial bone ingrowth into the porous structure, suggesting a continuous and progressive bone regeneration process. The CGF-PTa group exhibited denser and more continuous mineralized bone, consistent with the micro-CT results shown in Fig. 4, indicating that CGF-loaded PTa significantly promotes bone growth within the interbody fusion region.

Subsequent quantitative analysis of bone area fraction within the cage (defined as the region of interest, ROI) showed that at 4 weeks postoperatively, the CGF-PTa group exhibited a bone area fraction of 8.73 ± 1.81%, representing an approximately 59.9% increase compared to 5.46 ± 0.84% in the PTa group (p < 0.01). By 8 weeks, the bone area fraction increased to 41.38 ± 5.17% in the CGF-PTa group and 25.65 ± 2.79% in the PTa group. Notably, the CGF-PTa group demonstrated a significantly stronger trend in bone formation, with a 61.3% increase in bone area compared to the PTa group (p < 0.001) (Fig. 6b). It should be emphasized that due to the limited interbody space in rats, the volume of the tantalum scaffold was relatively small, allowing only one histological section per sample. Due to the limitation in the number of sections, we chose a single Van-Gieson staining to assess bone formation. This limitation may affect the representativeness of the data, and future studies could provide more comprehensive insights by increasing scaffold size or using other staining methods.

Histological analysis of the interbody fusion region at 4 and 8 weeks postoperatively. (a) Representative Van-Gieson stained images of the interbody fusion region in the PTa and CGF-PTa groups at 4 and 8 weeks after cage implantation. Red indicates newly formed bone, black representscage pores, and yellow denotes surrounding background tissue. (b) Quantitative analysis of bone area fraction within the cage based on Van-Gieson staining. (n = 6; Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Intergroup comparisons at each time point were performed using independent-samples t-tests. * indicates significant difference between groups: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.).

Immunohistochemistry

To evaluate the effects of CGF-PTa on angiogenesis and osteogenesis, immunohistochemical analysis was performed on bone tissue from the interbody fusion region (Fig. 7a). CD31 and VEGF were selected as representative markers for angiogenesis. CD31 is a typical endothelial cell marker involved in maintaining vascular integrity and permeability, while VEGF is a key mediator of angiogenesis, capable of significantly promoting the formation and expansion of new capillaries, thereby improving local blood supply27. In parallel, Runx2 and OCN were selected as osteogenic markers reflecting early and late stages of bone formation, respectively. Runx2 is a core transcription factor required for osteoprogenitor cell differentiation, with increased expression indicating activation of osteogenesis. OCN, a late-stage matrix protein secreted by osteoblasts, reflects ongoing matrix maturation and mineralization28.

As shown in Fig. 7b, at 4 weeks postoperatively, the proportions of CD31 and VEGF positive cells in the CGF-PTa group were significantly higher than those in the PTa group (both p < 0.001), indicating that the involvement of CGF notably enhanced local angiogenic activity in the early stage of bone healing. By 8 weeks, although the difference between the two groups had decreased, the expression levels of CD31 and VEGF in the CGF-PTa group remained higher than in the PTa group (p < 0.05, p < 0.01), suggesting a sustained angiogenic effect in the mid-to-late healing stage. As shown in Fig. 7c, at 4 weeks postoperatively, the proportions of OCN and Runx2 positive cells in the CGF-PTa group were also higher than those in the PTa group (p < 0.05), indicating that CGF application not only activated osteoblast differentiation early but also promoted the expression of bone matrix proteins. This trend further increased by 8 weeks, with a significant increase in OCN-positive cells (p < 0.01), and Runx2 expression reaching statistical significance (p < 0.001), suggesting that CGF-PTa continued to enhance osteogenic activity and bone remodeling in the mid-to-late healing stage. Overall, the pro-angiogenic effect of CGF-PTa became evident in the early postoperative period and provided a favorable microenvironment for subsequent bone repair. Over time, its osteogenic-promoting effect gradually increased, showing stronger tissue regeneration capacity during the later phase of bone healing. This synergistic enhancement of angiogenesis and osteogenesis reveals a potential mechanism by which CGF promotes angiogenic–osteogenic coupling during interbody fusion.

Immunohistochemical analysis of the interbody fusion region at 4 and 8 weeks postoperatively. (a) Representative immunohistochemical staining images showing the expression of CD31, VEGF, OCN, and RUNX2 at 4 and 8 weeks after surgery. Cytoplasmic staining of positive cells appears brown, while nuclei are stained dark blue. (b) Quantitative analysis of the proportions of CD31 and VEGF positive cells. (c) Quantitative analysis of the proportions of OCN and RUNX2 positive cells. (n = 6; Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Comparisons between PTa and CGF-PTa groups were performed using independent-samples t-tests. * indicates significant difference between groups: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Degradation and local biocompatibility evaluation of CGF

The degradation process of the CGF gel is shown in the Supplementary Fig. S2. The results indicated that the subcutaneously implanted CGF gel gradually decreased in size on days 0, 3, 7, and 14, with no visible signs of inflammation observed on the skin surface at any time point. The degradation curve showed that the initial mass of the CGF gel was 0.50 ± 0.01 g, which decreased to 0.35 ± 0.02 g on day 3, 0.20 ± 0.01 g on day 7, and further to 0.05 ± 0.01 g on day 14. This degradation process is likely associated with the gradual absorption and breakdown of fibrin components in CGF by host tissues. Overall, the CGF gel showed a continuous degradation trend after implantation, with a cumulative degradation rate of 90.6% by day 14.

Osseointegration assessment by histomorphometry analysis

Tissue sections of major organs were prepared and stained with H&E to assess whether the implantation of the fusion cage caused any pathological changes (Supplementary Fig. S3). At 8 weeks postoperatively, no obvious pathological abnormalities were observed in the CGF-PTa group compared with the non-operated control group. These results indicate that the PTa cage loaded with CGF, as well as any potential degradation products, did not induce significant toxicity in the major organs of SD rats, demonstrating good in vivo biocompatibility.

Discussion

Delayed bone healing and pseudarthrosis are common complications following interbody fusion surgery, primarily attributed to the limited vascularity within the intervertebral space and the complex mechanical environment29,30. Although conventional fusion cages can provide essential mechanical stability, their limited bioactivity hampers optimal osseointegration under hypovascular conditions31. Therefore, strategies that not only maintain sufficient mechanical support but also enhance the local biological microenvironment to stimulate angiogenesis and osteogenesis have become a major focus in spinal fusion research. In this study, a rat XLIF model was employed to systematically investigate the osteogenic and fusion-promoting effects of CGF-PTa cages. Evaluations were conducted at 4 and 8 weeks postoperatively using manual palpation, radiographic imaging, biomechanical testing, and histological analysis. The results demonstrated that, compared with the PTa group, the CGF-PTa group achieved earlier interbody fusion, exhibited accelerated bone formation, higher fusion rates, and superior segmental stability.

Tantalum metal has been widely adopted in clinical implant applications due to its elastic modulus similar to that of cancellous bone, high porosity, and excellent biocompatibility32,33. Its porous architecture not only mitigates stress shielding but also provides an ideal three-dimensional scaffold for cellular adhesion and bone ingrowth34,35. Leveraging these advantages, Ta-based materials have been extensively used in joint arthroplasty, traumatic fracture repair, post-tumor bone reconstruction, and interbody fusion procedures33,36. However, the intrinsic bioinertness of tantalum metal limits its osteoinductive potential37. CGF, enriched with multiple pro-angiogenic and osteogenic cytokines, can continuously release growth factors such as VEGF, TGF-β, and IGF-1, thereby promoting angiogenesis and inducing the osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells20,38. The integration of CGF with PTa cages is therefore expected to establish a composite system that combines mechanical robustness with biological activity within the intervertebral space, ultimately accelerating bone regeneration and interbody fusion.

In this study, PTa metal cages were fabricated using a CVD technique and subsequently loaded with gel-form CGF through negative pressure infusion. The cages were characterized by SEM. The struts of the PTa cages were uniform and structurally intact, exhibiting an interconnected pore architecture similar to that of cancellous bone, with a highly regular dodecahedral geometry in terms of pore size and shape. The surface morphology demonstrated micro- and nanoscale roughness. The CGF, prepared from allogeneic rat cardiac blood, displayed a uniform and dense fibrin network structure, within which platelets, red blood cells, and white blood cells were visibly embedded. In the CGF-PTa composite cage, SEM imaging revealed that the porous structure was extensively coated with dense fibrin matrix. Fibrin fibers of varying sizes adhered to and penetrated deeply into the cage’s internal pore network. High-magnification observations of the gel-filled pores showed a complex internal structure composed of densely woven fibrin networks, platelets, and red blood cells. Previous studies have demonstrated that high-viscosity fibrin scaffolds can act as temporary “nesting” matrices for platelets, erythrocytes, leukocytes, and CD34⁺ cells, enabling their initial retention and the gradual release of growth factors39,40. This controlled release mechanism helps to avoid early-stage burst release and instead delivers cytokines in a more physiologically regulated manner41,42. “On-demand” release not only holds the potential to amplify biological effects but also reduces the risk of tissue edema and inflammation caused by high local concentrations of growth factors43. Subsequent ELISA results further confirmed that angiogenic and osteogenic growth factors, including VEGF, TGF-β, and IGF-1, were continuously and gradually released from the CGF-PTa composite cage over a period of 14 days, supporting the feasibility of the proposed release mechanism.

To evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of CGF-loaded tantalum cages fabricated via CVD in spinal fusion procedures, the selection of an appropriate animal model is critical. In spinal fusion research, small animal models have become ideal tools for high-throughput screening and mechanistic studies due to their short observation periods, low cost, and high reproducibility44. Therefore, rat models of spinal fusion are widely used in related research45,46,47,48. However, due to the small body size of rats and technical limitations in surgical procedures, commonly employed spinal fusion models are primarily limited to intertransverse process fusion and coccygeal interbody fusion46,47. It is important to note that the applicability of these two models has long been a subject of debate. Some researchers argue that intertransverse process fusion more closely resembles conventional bone defect models and does not adequately reflect the biological processes of interbody fusion49,50. Others contend that coccygeal interbody fusion fails to accurately replicate the axial loading and shear stress experienced during the interbody fusion process51. To address this issue, our research team developed a rat lumbar interbody fusion model based on the anatomical characteristics of rats, utilizing a lateral extraperitoneal approach(XLIF technique). This model more accurately simulates the biomechanical conditions of human interbody fusion24. X-ray results showed that no evident loosening or displacement of the implants or internal fixation devices was observed in either the PTa or CGF-PTa groups during the postoperative follow-up period. At both 4 and 8 weeks postoperatively, interbody fusion scores in the CGF-PTa group were consistently higher than those in the PTa group. Manual palpation findings were consistent with the radiographic fusion scores, showing higher fusion rates in the CGF-PTa group at both time points. Notably, at 8 weeks postoperatively, the fusion rate in the CGF-PTa group reached 91.7%, which was significantly higher than the 41.7% observed in the PTa group. Micro-CT assessments at 4 and 8 weeks revealed initial bone ingrowth in both groups at the 4-week time point, with the CGF-PTa group demonstrating superior bone healing, particularly in terms of new bone formation and tissue ingrowth, despite the absence of complete interbody fusion. As healing progressed to 8 weeks, more pronounced new bone formation and the establishment of stable bony bridging across the interbody space were observed in both groups. Bone structural parameters, including BV/TV, BS/TV, Tb.Th, Tb.N, Tb.Sp, and BMD, generally improved over time, indicating ongoing bone regeneration. Although both groups showed favorable healing trends, the CGF-PTa group consistently exhibited superior outcomes, suggesting greater potential for CGF-PTa in promoting bone regeneration and interbody fusion.

At 4 and 8 weeks postoperatively, animals were euthanized, and the spinal segments were harvested after removal of the screws and titanium plates. Biomechanical testing, including flexion-extension and lateral bending, was performed on both the PTa and CGF-PTa groups. The results showed that the CGF-PTa group exhibited greater structural stiffness in all loading directions compared to the PTa group, indicating superior mechanical stability of the fused segment. Notably, although the differences between the groups were slightly reduced at 8 weeks, the CGF-PTa group continued to demonstrate a mechanical advantage. However, it should be noted that while trends toward increased stiffness were observed, the p-values for several directions at 8 weeks were not statistically significant. This highlights the limitation of the small sample size (n = 3) in biomechanical testing, which may have resulted in insufficient statistical power to detect significant differences. Future studies with larger sample sizes are necessary to confirm the observed trends and further validate the mechanical advantage of CGF-PTa in enhancing spinal fusion stability. Subsequently, hard tissue grinding sectioning combined with Van-Gieson staining was used to evaluate changes in bone volume within the fusion region. The results revealed that the bone area fraction within the scaffold in the CGF-PTa group was 8.73% at 4 weeks and 41.38% at 8 weeks, significantly higher than the 5.46% and 25.65% observed in the PTa group, corresponding to increases of approximately 59.9% and 61.3%, respectively. These findings were highly consistent with the micro-CT results, indicating that CGF loading not only facilitates early-stage adhesion and colonization of new bone tissue but also promotes more extensive and deeper bone infiltration and remodeling within the scaffold at later stages. The above biomechanical and histological findings further validate the effectiveness of CGF in enhancing the osteogenic performance of interbody fusion scaffolds. These results are also consistent with previous studies that support the osteogenic potential of CGF, highlighting its favorable regenerative capacity and promising application prospects52,53. To further investigate the underlying biological mechanisms, immunohistochemical analysis was conducted to assess the expression of angiogenesis and osteogenesis related markers in the fusion region. The results demonstrated a higher proportion of CD31 and VEGF positive cells in the CGF-PTa group at both 4 and 8 weeks, suggesting enhanced local angiogenesis that may support new bone formation. In parallel, the expression of osteogenic markers Runx2 and OCN was significantly upregulated, indicating that CGF facilitates osteoblast differentiation and extracellular matrix maturation. These findings are consistent with previous reports showing that CGF is rich in multiple growth factors, such as VEGF, TGF-β, and IGF-1, which promote both angiogenesis and osteogenesis22,54. The results provide further evidence, at the cellular and molecular levels, supporting the potential of CGF in bone tissue engineering. In addition, histological examination of the tissue surrounding the implant and major organs confirmed the favorable in vivo biocompatibility of the CGF-PTa construct, laying a foundation for its future clinical translation. In summary, the incorporation of CGF into PTa cage establishes a favorable microenvironment that synergistically promotes both neovascularization and bone formation, offering an effective strategy to enhance the bioactivity of porous metal fusion devices.

Although this study systematically evaluated the osteogenic effects and biocompatibility of the CGF-PTa system in interbody fusion, its translational relevance to human clinical conditions should be further emphasized. The rat XLIF model used in this study closely replicates the essential biomechanical and healing environment encountered in human lumbar fusion surgery, and the combination of a PTa cage with CGF directly targets two major clinical challenges—mechanical stability and insufficient vascularization within the intervertebral space. Given the established clinical application and biocompatibility of tantalum-based implants, together with the autologous nature of CGF, our findings suggest strong potential for translating this dual-functional strategy into human interbody fusion practice. Nevertheless, several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. (1) Due to the limited interbody space in rats, the tantalum scaffold volume was relatively small, allowing only one histological section per sample and restricting the number of staining methods. Future studies may adopt customized drilling techniques to enlarge the interbody space, thereby improving operability and evaluation efficiency. (2) Although CGF is ideally derived from autologous blood to ensure immunocompatibility, due to the limited blood volume in rats, allogeneic CGF was used in this study, which may have introduced potential confounding factors. Allogeneic CGF may contain foreign components that the immune system may not recognize as ‘self’, potentially triggering immune responses such as rejection or local inflammation, which could interfere with bone healing and biocompatibility. While no significant immunological side effects or rejection were observed in this study, future research should further explore the immunological differences between autologous and allogeneic CGF in larger animal models, to better understand their impact on therapeutic outcomes and to validate their clinical safety and efficacy. (3) While CGF inherently provides sustained release of bioactive factors, combining it with hydrogels or nanomaterials could further extend release duration. However, to enhance clinical translatability, this study deliberately avoided introducing exogenous materials that may pose biotoxicity risks, which may have limited sustained-release optimization. Overall, these limitations point to directions for model refinement and lay the groundwork for validation in large-animal models and eventual preclinical or clinical translation.

Conclusion

In this study, a composite system comprising PTa cage loaded with CGF was developed and systematically evaluated in a rat interbody fusion model. The results demonstrated that CGF-PTa exhibited excellent performance in terms of fusion rate, biomechanical stability, biocompatibility, osteogenic capacity, and bone integration, significantly enhancing the long-term stability of the fusion segment. The synergistic effect between CGF and the porous tantalum cage enabled coordinated promotion of both angiogenesis and bone regeneration within the interbody fusion microenvironment, highlighting its promising potential in the field of tissue engineering. This strategy offers a novel approach and theoretical foundation for the functional optimization and clinical translation of porous metal fusion devices.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and can also be accessed as supplementary information files.

References

Ravindra, V. M. et al. Degenerative lumbar spine disease: estimating global incidence and worldwide volume. Global Spine J. 8, 784–794 (2018).

Yavin, D. et al. Lumbar fusion for degenerative disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurgery 80, 701–715 (2017).

Veronesi, F. et al. Complications in spinal fusion surgery: a systematic review of clinically used cages. J. Clin. Med. 11, 6279 (2022).

Formica, M. et al. Fusion rate and influence of surgery-related factors in lumbar interbody arthrodesis for degenerative spine diseases: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Musculoskelet. Surg. 104, 1–15 (2020).

Myeroff, C. & Archdeacon, M. Autogenous bone graft: donor sites and techniques. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 93, 2227–2236 (2011).

Patel, M. S., McCormick, J. R., Ghasem, A., Huntley, S. R. & Gjolaj, J. P. Tantalum: the next biomaterial in spine surgery? J. Spine Surg. 6, 72–86 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Evaluation of biological performance of 3D printed trabecular porous tantalum spine fusion cage in large animal models. J. Orthop. Translat. 50, 185–195 (2025).

Liu, Y., Bao, C., Wismeijer, D. & Wu, G. The physicochemical/biological properties of porous tantalum and the potential surface modification techniques to improve its clinical application in dental implantology. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 49, 323–329 (2015).

Wauthle, R. et al. Additively manufactured porous tantalum implants. Acta Biomater. 14, 217–225 (2015).

Guo, Y. et al. In vitro and in vivo study of 3D-printed porous tantalum scaffolds for repairing bone defects. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 5, 1123–1133 (2019).

Lewallen, E. A. et al. Biological strategies for improved osseointegration and osteoinduction of porous metal orthopedic implants. Tissue Eng. B Rev. 21, 218–230 (2015).

Derby, B. Printing and prototyping of tissues and scaffolds. Science 338, 921–926 (2012).

Ehrenfest, D. M. D. et al. The impact of the centrifuge characteristics and centrifugation protocols on the cells, growth factors, and fibrin architecture of a leukocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF) clot and membrane. Platelets 29, 171–184 (2018).

Huang, L., Zou, R., He, J., Ouyang, K. & Piao, Z. Comparing osteogenic effects between concentrated growth factors and the acellular dermal matrix. Braz Oral Res. 32, e29 (2018).

Wang, F., Li, Q. & Wang, Z. A comparative study of the effect of Bio-Oss® in combination with concentrated growth factors or bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in canine sinus grafting. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 46, 528–536 (2017).

Lei, L. et al. Quantification of growth factors in advanced platelet-rich fibrin and concentrated growth factors and their clinical efficacy as adjunctive to the GTR procedure in periodontal intrabony defects. J. Periodontol. 91, 462–472 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. A comparative study of the effects of concentrated growth factors in two different forms on osteogenesis in vitro. Mol. Med. Rep. 20, 1039–1048 (2019).

Palermo, A. et al. Use of CGF in oral and implant surgery: from laboratory evidence to clinical evaluation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 15164 (2022).

Rochira, A. et al. Concentrated growth factors (CGF) induce osteogenic differentiation in human bone marrow stem cells. Biology (Basel). 9, 370 (2020).

Qiao, J., An, N. & Ouyang, X. Quantification of growth factors in different platelet concentrates. Platelets 28, 774–778 (2017).

Li, H. et al. Clinical observation of concentrated growth factor (CGF) combined with Iliac cancellous bone and composite bone material graft on postoperative osteogenesis and inflammation in the repair of extensive mandibular defects. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 124, 101472 (2023).

Herrera-Vizcaino, C. & Albilia, J. B. Temporomandibular joint biosupplementation using platelet concentrates: a narrative review. Front. Oral Maxillofac. Med. 3, 38–38 (2021).

Kabir, M. A. et al. Mechanical properties of human concentrated growth factor (CGF) membrane and the CGF graft with bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) onto periosteum of the skull of nude mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 11331 (2021).

Wu, H., Li, S., Wang, W., Li, J. & Zhang, W. Demineralized bone matrix combined with concentrated growth factors promotes intervertebral fusion in a novel rat extreme lateral interbody fusion model. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 20, 529 (2025).

Lam, W. M. R. et al. Mesenchymal stem cell exosomes enhance posterolateral spinal fusion in a rat model. Cells 13, 761 (2024).

Kobayashi, E. et al. Comparative release of growth factors from PRP, PRF, and advanced-PRF. Clin. Oral Investig. 20, 2353–2360 (2016).

Li, S. et al. Dual-functional 3D-printed porous bioactive scaffold enhanced bone repair by promoting osteogenesis and angiogenesis. Mater. Today Bio. 24, 100943 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Improved intervertebral fusion in LLIF rabbit model with a novel titanium cage. Spine J. 24, 1109–1120 (2024).

Cui, L. et al. A novel tissue-engineered bone graft composed of silicon-substituted calcium phosphate, autogenous fine particulate bone powder and BMSCs promotes posterolateral spinal fusion in rabbits. J. Orthop. Translat. 26, 151–161 (2021).

Glatt, V., Evans, C. H. & Tetsworth, K. A concert between biology and biomechanics: the influence of the mechanical environment on bone healing. Front. Physiol. 7, 678 (2016).

Hickman, T. T., Rathan-Kumar, S. & Peck, S. H. Development, pathogenesis, and regeneration of the intervertebral disc: current and future insights spanning traditional to omics methods. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 10, 841831 (2022).

Chen, Z. et al. Influence of the pore size and porosity of selective laser melted Ti6Al4V ELI porous scaffold on cell proliferation, osteogenesis and bone ingrowth. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 106, 110289 (2020).

Lu, T. et al. Enhanced osteointegration on tantalum-implanted polyetheretherketone surface with bone-like elastic modulus. Biomaterials 51, 173–183 (2015).

Kumar, G. et al. The determination of stem cell fate by 3D scaffold structures through the control of cell shape. Biomaterials 32, 9188–9196 (2011).

Zhang, Y. et al. The contribution of pore size and porosity of 3D printed porous titanium scaffolds to osteogenesis. Biomater. Adv. 133, 112651 (2022).

De Arriba, C. C. et al. Osseoincorporation of porous tantalum trabecular-structured metal: a histologic and histomorphometric study in humans. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 38, 879–885 (2018).

Yuan, K. et al. Evaluation of interbody fusion efficacy and biocompatibility of a polyetheretherketone/calcium silicate/porous tantalum cage in a goat model. J. Orthop. Translat. 36, 109–119 (2022).

Talaat, W. M., Ghoneim, M. M., Salah, O. & Adly, O. A. Autologous bone marrow concentrates and concentrated growth factors accelerate bone regeneration after enucleation of mandibular pathologic lesions. J. Craniofac. Surg. 29, 992–997 (2018).

Inchingolo, F. et al. Guided bone regeneration: CGF and PRF combined with various types of scaffolds-a systematic review. Int. J. Dent. 4990295 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. Bone regeneration facilitated by autologous bioscaffold material: liquid phase of concentrated growth factor with dental follicle stem cell loading. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 10, 3173–3187 (2024).

Rodella, L. F. et al. Growth factors, CD34 positive cells, and fibrin network analysis in concentrated growth factors fraction. Microsc Res. Tech. 74, 772–777 (2011).

Xu, F. et al. The potential application of concentrated growth factor in pulp regeneration: an in vitro and in vivo study. Stem Cell. Res. Ther. 10, 134 (2019).

Chen, J. & Jiang, H. A comprehensive review of concentrated growth factors and their novel applications in facial reconstructive and regenerative medicine. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 44, 1047–1057 (2020).

Gruber, H. E. et al. A new small animal model for the study of spine fusion in the sand rat: pilot studies. Lab. Anim. 43, 272–277 (2009).

Furuichi, T. et al. Nanoclay gels attenuate BMP2-associated inflammation and promote chondrogenesis to enhance BMP2-spinal fusion. Bioact Mater. 44, 474–487 (2025).

Findeisen, L. et al. Exploring an innovative augmentation strategy in spinal fusion: a novel selective prostaglandin EP4 receptor agonist as a potential osteopromotive factor to enhance lumbar posterolateral fusion. Biomaterials 320, 123278 (2025).

Gantenbein, B. et al. The bone morphogenetic protein 2 analogue L51P enhances spinal fusion in combination with BMP2 in an in vivo rat tail model. Acta Biomater. 177, 148–156 (2024).

Plantz, M. A. et al. Osteoinductivity and Biomechanical assessment of a 3D printed demineralized bone matrix-ceramic composite in a rat spine fusion model. Acta Biomater. 127, 146–158 (2021).

Kang, Y. et al. A novel rat model of interbody fusion based on anterior lumbar corpectomy and fusion (ALCF). BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 22, 965 (2021).

Yeh, Y. C. et al. Characterization of a novel caudal vertebral interbody fusion in a rat tail model: an implication for future material and mechanical testing. Biomed. J. 40, 62–68 (2017).

Drespe, I. H., Polzhofer, G. K., Turner, A. S. & Grauer, J. N. Animal models for spinal fusion. Spine J. 5, 209S–216S (2005).

Durmuslar, M. C. et al. Histological evaluation of the effect of concentrated growth factor on bone healing. J. Craniofac. Surg. 27, 1494–1497 (2016).

Stanca, E. et al. Analysis of CGF biomolecules, structure and cell population: characterization of the stemness features of CGF cells and osteogenic potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 8867 (2021).

Takeda, Y., Katsutoshi, K., Matsuzaka, K. & Inoue, T. The effect of concentrated growth factor on rat bone marrow cells in vitro and on calvarial bone healing in vivo. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants. 30, 1187–1196 (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Han Wu: Writing – original draft. Weijian Wang: Data curation. Shaorong Li: Writing – review & editing. Jianshi Song: Writing – review & editing. Sidong Yang: Writing – review & editing. Qiang Yang: Visualization. Liang Li: Visualization. Ruixin Zhen: Conceptualization. Haoyu Wu: Investigation. Wei Zhang: Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, H., Wang, W., Li, S. et al. Porous tantalum cage loaded with CGF promotes interbody fusion in a rat XLIF model. Sci Rep 16, 1934 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31736-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31736-1