Abstract

Thin Film Lithium Niobate (TFLN) is a promising platform for applications at 1064 nm, including spectroscopy, metrology, and space communications through free space optics links, enabling high throughput wireless communication. However, compared with the 1550 nm optical window, TFLN waveguide cross-section optimization around 1 μm is more complex and lacking. Here, numerical simulations are carried out to compare etched and rib-loaded waveguides with an etched rib-loaded geometry, focusing on phase modulator performance in terms of optical losses and modulation efficiency, through the parameter \(V_\pi L\). Absorption and scattering losses are considered, with the latter more severe at 1064 nm compared to 1550 nm, and calculated via the Payne-Lacey model, where waveguide roughness is estimated via atomic force microscopy and visible spectrum measurements. Polarization mixing, affecting both etched geometries, is also assessed in 90 degree curves by simulating the refractive index variation of the fundamental TE and TM modes and through FDTD simulations. Results indicate that while the fabrication of etched rib-loaded guides is more complex, the polarization mixing effect is reduced and lower losses are exhibited at high EO modulation efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Compared to the decades of development of components for operation at the 1550 nm wavelength, components for use around 1 μm have seen little, despite recent interest in this window for space communications, spectroscopy, and metrology1,2,3,4. Free space optical communications (FSO) offer several advantages over RF systems, including higher bandwidth, with terabit/s data rates over km distances5, lower beam divergence and high directivity, allowing for better security, reduced interference, and smaller receiver size6. Generally, FSO systems are useful wherever laying optical fiber is not practical7, such as high data rate inter-satellite communications; in this regard, 1064 nm systems were selected for the European Space Agency’s European Data Relay Satellite (EDRS) program8, which allows fast data transmission between low earth orbit satellites and geostationary satellites, and from the latter to ground stations. Recently, the Consultative Committee for Space Data Systems confirmed the wavelength as suitable for this program9. Furthermore, a global quantum key distribution satellite network has been proposed10, where satellite-ground applications are made feasible by advances in adaptive optics correction systems11. Regarding other applications, comb generation centred at 1 μm has been exploited for stellar spectroscopy12, laser frequency noise characterization13 and molecular fingerprinting14. These applications currently employ bulk optics systems and do not benefit from the advantages offered by integrated photonics: small footprint, low power consumption, and increased thermal and mechanical stability.

Although silicon photonics offers the most mature integrated photonics platform, leveraging the decades of development of CMOS processes for integrated electronics, it is not transparent at 1064 nm. Thin Film Lithium Niobate (TFLN) is an ideal material due to its transparency in this window and with modulators that exhibit high linearity and bandwidth. At 1550 nm, there has been years of dedicated research effort, allowing the development of fast CMOS driven modulators at 70 Gbit/s15 with a recent demonstration of a fully packaged 100 GHz-bandwidth modulator16. Some of the challenges faced by TFLN include unwanted effects produced by the mobile charge carriers, leading to DC bias drift; this effect has been known for years in bulk LN17. The drift is generally corrected in TFLN by feedback loops and thermo-optic phase shifters18, with recent alternative correction strategies involving a pre-processing of the TFLN with an Ar+ milling19. At 1064 nm, the platform still has lots of room for development20, where fabricated modulators with thin electrodes and DC-only characterizations were reported in21, and RF characterization up to 5 GHz was reported in22. A recent fabrication of a >38 GHz bandwidth modulator was realized with etched waveguides and an optimized travelling wave electrode (TWE) design23, here the measurement was bandwidth limited by the photodiode, the modulator was simulated to have 1.7 dB of roll-off in EO response at 80 GHz. When considering platform development for use at a new wavelength, there are many geometrical parameters that affect performance, notably the waveguide type, its cross section and the starting thickness of the LN which undergoes etching.

In this paper, in order to inform process design choices for operators wishing to work with TFLN at 1064 nm, various waveguide geometries at 1064 nm are simulated and the relative propagation loss and electro-optic (EO) phase shifter performance is compared. The waveguides correspond to the often reported etched and rib-loaded geometries24, an additional waveguide is considered for the first time for the TFLN platform, combining etch and rib-loading process steps. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) scans and visible spectrum measurements are used to estimate the roughness in order to calculate the optical scattering losses via the Payne-Lacey model; compared to telecom wavelengths this is particularly critical at 1064 nm due to Rayleigh scattering scaling with the inverse of the wavelength to the fourth power, the effect is usually not considered in simulative work. Problems with the polarization mixing are also investigated for the first time at the 1064 nm wavelength, and the behaviour is compared among the geometries. The effects of changing the waveguide width and thickness of the LN substrate are then investigated for the etched geometry.

Waveguiding structures in TFLN

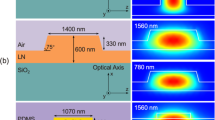

TFLN optical modulators rely on efficient, fast, and precise phase shifting; in X-cut TFLN, they are commonly realized in the form of a straight rib waveguide placed between two electrodes, which modulate the effective refractive index through the linear Pockels EO effect present in the LN crystal25. Within this structure, the design of the waveguide and electrode cross section is critical: electrodes that are closer to the waveguide will result in higher field intensity and therefore more efficient modulation, but also in higher optical loss due to the interaction of the optical mode with the metal. In the following we introduce three cross-sections of interest for a TFLN platform operating at 1064 nm, illustrated in Fig. 1, aimed at realizing etched waveguides, rib-loaded waveguides, as well as the combined etched rib-loaded waveguides.

For etched geometries, a wider waveguide becomes multimode for a shallower etch depth; for this comparison, the upper width of waveguides, illustrated in Fig. 1c, was selected to be w = 600 nm, ensuring mono-mode operation at etch depths which strike a compromise between modulator efficiency and electrode losses, concurring with what was found in23. The substrate was simulated as X-cut LNOI, with propagation along the ordinary axis and the cladding assumed to have a refractive index of 1.5 at 1064 nm. The Lumerical MODE and CHARGE suites were used to estimate the mode-field profiles and properties, considering the perturbation introduced by an external electric field. The electrodes were assumed to be gold deposited with a height of 800 nm, facilitating lift-off while mitigating microwave losses23, and to be separated by gaps between 3 and 5 μm. The boundary conditions in the simulators were considered to be perfectly matched layer.

Etched

Rib waveguides can be produced mechanically with diamond blade dicing26, or by chemical mechanical polishing27. Here, we will focus on dry etching, which is the preferred technique for integrated photonics due to its compatibility with other process steps and the ability to achieve complex patterning. Compared to other materials, LN is difficult to dry etch. Notably, redeposition causes the sidewalls to become non-vertical and rough, which limits the minimum feature size and introduces optical loss. Additionally, the etch depth is limited by the high consumption of the lithography resists24. An example of an etched geometry is shown in Fig. 1a, where \(\alpha\) indicates the etch angle, s and e indicate the slab thickness and etch depth, respectively. The original thickness of the LN substrate was assumed to be 600 nm, common for TFLN23,28, and the etch depth e was varied. The etch angle, \(\alpha\), was assumed to be 25°, dictated by the etching process for LN waveguide fabrication at the James Watt Nanofabrication Centre of the University of Glasgow. It is generally favorable to have mono-mode operation in order to avoid cross-talk and excessive losses29. Because of the trapezoidal shape of the waveguide, the waveguide width of 600 nm allows mono-mode operation up to an etch depth of 350 nm.

Rib-loaded

To avoid the problems with etching, a common solution is to deposit a different, easier-to-etch, material onto the LN slab, thereby creating an effective rib waveguide by the variation in the effective refractive index perpendicular to the light propagation axis. The deposited material has vertical facets after etching, and less surface roughness than LN etched guides. Various materials have been investigated, including SiN30,31,32 (considered in this paper due to compatability with the fabrication processes at the James Watt Nanofabrication Centre), amorphous Si33, and TiO234. SiN-loaded waveguides in TFLN were fabricated for green light sources using a pump laser at 1062 nm via second harmonic generation35. The corresponding geometry is schematized in Fig. 1b, where r indicates the thickness of the deposited SiN. Due to a reduced confinement, these waveguides can exhibit a higher EO efficiency than the etched geometry at the expense of higher loss due to the increased interaction with the metal electrodes, as later discussed. The LN slab was assumed to have a thickness of s = 300 nm, and the SiN thickness was varied between r = 100 nm and 300 nm, for which the geometry remained monomode for the chosen w. Larger thicknesses tend to result in crack formation in the SiN rib.

Etched rib-loaded

The etched waveguides are prone to scattering losses due to sidewall roughness, which is enhanced as the operation wavelength decreases, and the rib-loaded guides have high EO efficiency with poor mode confinement. Hence, we explored the idea of combining the two techniques aiming to reduce the etch depth, and resulting scattering losses of the LN film while maintaining the modulator performance. This can be achieved by depositing an alternative material, again considered to be SiN, on top of the etched waveguide. The geometry is schematized in Fig. 1c. In order to limit the scattering losses, additional processing steps may be required, potentially increasing the complexity of fabrication: while a single mask could be used to simultaneously etch both the SiN and the LN with Ar+ based inductively coupled plasma reactive ion etching (ICP-RIE), this could produce non-vertical waveguides in the SiN layer due to the lateral component of the ion etch; as a second option, a single mask could be used with a double etch, one chemical etch to produce the vertical SiN waveguides, then an additional etch for the LN below, which could lead to an increase in the SiN sidewall roughness; the third option is to perform lithography and etch on the LN then deposit the SiN and perform a separate lithography and etch, increasing process complexity and requiring a precise alignment of two separate masks. This kind of waveguide has already been realized in silicon photonics, where the SiN is used as a hard mask, and the problems associated with the lateral component of the etching were partially addressed with a tri-layer hard mask etching process36.

Despite the additional complexity, this geometry generally requires a smaller LN etch depth to achieve good mode confinement, while allowing closer electrodes compared to a simple rib-loaded waveguide. Furthermore, as will be discussed, the addition of SiN could reduce the effects of polarization mixing, present at 1064 nm. The geometry was again varied by changing the LN etch depth, e, starting from a 600 nm thick substrate, with a SiN loading of r = 200 nm. Again, as for the etched geometry, mono-mode operation is possible up to an etch depth of 350 nm.

Methods

The coupling between the evanescent guided mode and the electrodes (hybrid plasmon-waveguide mode) causes optical loss in the phase shifter, which is strongly dependent on the waveguide mode confinement and its interaction with the electrodes. Another source of optical loss arises from the surface roughness of the various interfaces, which causes scattering. To model the scattering losses, the Payne-Lacey analytical model was employed37, which required the calculation of the line integral of the simulated electric field intensities along the interfaces and an estimation of material roughness. For each surface, the roughness was extracted through AFM scans of previously fabricated waveguides, not designed for use at 1064 nm, based on the available technology at the James Watt Nanofabrication Centre; this allows an estimation of the scattering losses at any wavelength. Here, both SiN and LN waveguides were patterned by e-beam lithography in hydrogen silsesquioxane resist, taking care to use a multipass exposure to minimize sidewall roughness. The pattern was then transferred to the waveguide core layer via an ICP-RIE process, and a silica upper cladding was deposited by plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition. The slanted sidewalls of the LN waveguides allow for AFM characterisation of their surface roughness, as visible in Fig. 2, with a corresponding roughness root mean square value of 1.48 nm. This is not possible for the SiN waveguides, due to the verticality of their sidewalls; in this case the roughness was estimated through SiN waveguide loss measurements across the visible spectrum, with a resulting estimated value of 1.12 nm.

To evaluate the efficiency of EO modulation the \(V_\pi L\) parameter was analyzed, with lower values indicating better modulation efficiency. As there is generally a compromise between \(V_\pi L\) and optical propagation loss, both of these parameters were simulated and plotted as a contour map in Fig. 3 as a function of the waveguide geometry and electrode gap; the LN slab thickness, s, below which the waveguide becomes multimode is shown as a green vertical line. Note that here the \(V_\pi L\) calculated is that of the structures illustrated in Fig. 1, for MZI modulators in TFLN the \(V_\pi L\) would be reduced by a factor of two due to push-pull operation.

Figure 3a–c correspond to etched, rib, and etched-rib respectively. The units of \(V_\pi L\) are \(\text {V}\cdot \text {cm}\) and those of optical losses dB/cm. As expected, for all the waveguides the losses decrease for increasing electrode gap while \(V_\pi L\) increases. For decreasing slab thickness (etched geometries) or increasing SiN thickness, the electrode losses generally decrease while the EO performance worsens due to better mode confinement, less concentrated in the LN slab. However, the scattering losses increase with a deeper etch (shallower slab), the balancing effect of these two sources of loss as a function of slab thickness is observed in Fig. 3a,c, creating the “islands” of loss lower than 0.5 dB/cm and 0.8 dB/cm respectively. This effect is not observed for the rib-loaded waveguides as the SiN is smoother than the LN, and the scattering losses caused by the surface roughness are negligible compared to those from electrode absorption.

For the SiN loaded geometry much higher losses are exhibited due to the wider mode, predominantly confined to the slab, which simultaneously results in better EO performance. For the etched rib-loaded geometry, before considering the effects of scattering loss, we observed significantly lower optical losses for equivalent values of \(V_\pi L\) when compared to the etched geometry, but since there are multiple interfaces that cause scattering, each with a characteristic roughness, the benefit is reduced and the lowest losses are limited to around 0.8 dB/cm.

Note that here the static \(V_\pi L\) for DC operation was analyzed, yet one of the advantages of LN-based modulators is high bandwidth. The geometries involving an etch step permit reasonable losses (< 2 dB/cm) at an electrode gap of 3 \(\upmu\)m, which allow for a low \(V_\pi L\); however a compromise must be struck between the microwave loss, which influences the bandwidth, and the \(V_\pi L\), as discussed in38.

An effect that is present at 1064 nm, which is less relevant at 1550 nm, is polarization mixing. By simulating the waveguides in MODE, the effective refractive indices, \(n_{eff}\), were found along the ordinary and extraordinary axis for the TE0 and TM0 modes. These values were assumed to correspond to the maxima and minima of a sinusoidal dependency on the propagation angle, as in39, where polarization mixing was predicted at 1310 nm. The results are plotted in Fig. 4, with TE0 modes represented in black, TM0 modes in red. Fig. 4a corresponds to the s = e = 300 nm geometry. Along the ordinary axis, the TM0 mode is better confined than the TE0 mode and, as the angle of propagation changes, the effective index of the former decreases while that of the latter increases. Thus at a certain angle of propagation, around 46°, the two modes share the same refractive index, and polarization mixing occurs. In Fig. 4b, the refractive indices are plotted as a function of propagation angle for the rib-loaded waveguide with SiN thickness of 200 nm, which constitutes a balance between optical loss and EO performance while not risking the crack formation possible with thick SiN deposition. Here, the refractive indices of the TE and TM modes do not cross for any angle of propagation and the behaviour is similar to what is observed at 1550 nm for etched waveguides39. The absolute values of \(n_{eff}\) are lower, indicating that the mode is less well confined and closer to that of the slab. In Fig. 4c, the s = 300 nm, e = 300 nm, r=200 nm case is analyzed, allowing low \(V_\pi L\) and losses, while maintaining mono-mode operation. The observed behaviour is similar to Fig. 4a, though the refractive indices of the modes cross for a steeper angle of 58°. To investigate the effect of polarization mixing, FDTD simulations were performed with results displayed in Fig. 5, the intensity in the y and x directions are plotted during a 90° bend, which correspond to the post-bend polarization directions of TE0 and TM0 respectively (light is injected into the TE0 mode from the top left of each curved section of waveguide). The bend radius was chosen to be large enough to avoid excess radiative loss while containing the FDTD simulation time, 50 μm for etched LN and 200 μm for rib-loaded geometries due to the weaker mode confinement associated with the latter. For the rib-loaded guide, no component of intensity in the x direction is observed throughout the curve, as expected from the rectangular symmetry of the waveguide and no crossing between the refractive indices of the TE0 and TM0 modes. The effect of the polarization mixing in the waveguides involving an LN etch step is observed as a non-zero intensity component \(I_x\) developing throughout the curve which increases after the angle at which the refractive indices of TE0 and TM0 cross, highlighted in the figure. The maximum value of \(I_x\) throughout the bend is around 10\(\%\) of the final TE0 intensity both for etched and etched-rib geometries, with the polarization mixing occurring at a shallower bend angle for the etched geometry.

Optical losses and \(V_\pi L\) as a function of electrode gap and etch depth for different waveguide widths and total LN substrate thickness. Widths of 400 nm in (a) and 800 nm in (b) at 600 nm of total LN substrate thickness and LN substrate thickness of 400 nm in (c) and 300 nm in (d) for 600 nm of waveguide width. The green vertical lines mark the approximate boundary between mono-mode and multi-mode behaviour.

To summarize, although the geometries which involve a LN etching step offer higher confinement of optical modes, care must be taken in order to avoid polarization mixing by keeping the angle of propagation with respect to the ordinary axis as low as possible. Of the geometries analyzed, the rib-loaded waveguide exhibits high electrode loss, which limits flexibility in the RF design. The etched rib-loaded geometry has performance similar to the etched geometry, with lower losses for high EO efficiency, but the lowest attainable loss is limited by the scattering of the various interfaces. This geometry is also more complex to fabricate, as previously discussed. In Table 1, a comparison between the three analyzed waveguides is offered. The mode confinement here relates to the trade-off between electrode absorption loss and EO modulation efficiency, to quantify this, the percentage of the total electric field intensity integrated in the rectangular region between the top of the waveguide (width w) and the buried oxide is reported in the table for the same geometries considered for the polarization mixing analysis; the scattering loss for these geometries are also reported. Among the geometries analyzed in this paper, for a high level of mode confinement a low absorption loss and modulation efficiency are observed and vice versa.

Two additional methods of realizing waveguides in TFLN are present in the table for context, which have not been simulated in this paper and have not currently been fabricated for use at 1064 nm. Proton exchange based waveguides have a mature fabrication process, based on immersion in a liquid source of hydrogen, with low scattering losses due to no etching step, however they suffer from low mode confinement and reduced EO and non-linear coefficients40. Heterogenous bonding involves adhering TFLN to a wafer fabricated in a different material, giving access to the unique properties of TFLN combined with those of different photonic material technologies, and allowing compatibility with CMOS processes, this forms effective rib-loaded waveguides but with LN as the secondary material. SiN is an ideal material for heterogenous bonding due to a wide transparency window and low propagation losses41, recently micro transfer printing has been used to place LN modulator coupons onto PICs fabricated in SiN with modulator operation above 50 GHz at 1550 nm42, here mode converters must be designed to ensure a low-loss transition between the host material and LN.

The effects of changing the waveguide widths (for \(s+e\) = 600 nm LN substrate thickness) and LN substrate thickness, \(s+e\) (for a w = 600 nm waveguide) are investigated in Fig. 6 for the etched geometry. From Fig. 6a, w = 400 nm, compared to the 600 nm width, we observe a worse mode confinement resulting in higher electrode losses, and also increased scattering loss due to the larger interaction of the mode with the sidewalls; however, the waveguide becomes multimode for a shallower slab thickness of 200 nm. Fig. 6b, w = 800 nm, demonstrates in general better loss and EO performance than w = 600 nm but the waveguide becomes multimode at a larger slab thickness of 350 nm. From Fig. 6c,d, we observe that changing the LN substrate thickness does not have a large effect on the optimum loss (< 1 dB/cm) value of \(V_\pi L\), and the waveguides become multimode for a similar aspect ratio of \(e/(e+s)\) , however when the substrate thickness is smaller this generally increases the scattering losses as the mode is closer to the sidewalls. Additionally, for the 300 nm thickness, a larger etch depth (thinner slab), proportional to the substrate thickness, is required in order to mitigate the electrode-coupling losses.

One of the key advantages of TFLN is a large modulator bandwidth, here travelling wave electrodes must be designed such that the impedance of the electrodes matches the terminating load, the microwave refractive index matches the optical group refractive index, and the microwave losses are minimized. An ideal structure for achieving this is the capacitively loaded travelling wave electrode, where for use at 1064 nm a TFLN modulator with a silicon substrate was simulated to have a 0.33 dB EO bandwidth roll-off at 80 GHz23.

Conclusions

The performance of different waveguide geometries was compared for the development of a TFLN platform at 1064 nm, with applications in high-throughput space communications and spectroscopy. The assessed geometries are etched LN, rib-loaded where the LN is loaded with an alternative material (here SiN is considered), and a etched rib-loaded, which combines an etching step with a SiN deposition and patterning. For each geometry, the phase shifter losses, the figure of merit \(V_\pi L\), and the polarization mixing between TE0 and TM0 were analyzed. Both the electrode absorption and scattering losses due to surface roughness were considered. The latter are more significant at 1064 nm than at telecom wavelengths and are estimated via the Payne-Lacey analytical model, using AFM scans and visible light waveguide characterizations for LN and SiN respectively. Although the fabrication would be complex, the etched rib-loaded geometry offers lower losses than the etched waveguides for the lowest values of \(V_\pi L\); however, if low optical loss is targetted, it offers similar performance due to the effect of enhanced scattering losses resulting from the additional interfaces which compose the waveguide. For waveguides fabricated with an LN etch step, the propagation angles must be kept low with respect to the ordinary crystal axis to avoid polarization mixing; this effect is not present for the rib-loaded waveguide and occurs at a steeper angle of propagation for the etched rib-loaded guides, where the increased robustness to mixing comes from the addition of the SiN. In the etched geometry, a wider waveguide reduces the optical losses for equivalent \(V_\pi L\), though the etch depth at which the waveguide becomes multimode decreases; changing the LN starting substrate thickness did not have a notable effect on the low-loss EO efficiency, but a general increase in optical losses was predicted for lower thicknesses. Future work will involve fabrication and experimental verification of the reported results.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The code used for analysis is available upon request from the authors.

References

Hall, S. A survey of free space optical communications in satellites. Guggenheim School Aerosp. Eng., Georgia Inst. Technol., Atlanta, GA, USA, Rep. AE 8900 (2020).

Ivanov, H., Mejri, S., Di Mira, A., Schulz, K.-J. & Heese, C. Review of deep space optical communications. Int. J. Satellite Commun. Netw. (in press) https://doi.org/10.1002/sat.1543https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/sat.1543

Metcalf, A. J., Fredrick, C. D., Terrien, R. C., Papp, S. B. & Diddams, S. A. 30 GHz electro-optic frequency comb spanning 300 THz in the near infrared and visible. Opt. Lett. 44(11), 2673–2676. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.44.002673 (2019).

Kincaid, P.S., De Marinis, L., Contestabile, G., Pruiti, N., Sorel, M. & Andriolli, N. Thin-film lithium niobate at 1064 nm for telecommunications and sensing. In: 2025 30th OptoElectronics and Communications Conference (OECC) and 2025 International Conference on Photonics in Switching and Computing (PSC) 1–4 https://doi.org/10.23919/OECC/PSC62146.2025.11110945 (2025).

Poliak, J., Calvo, R. M. & Rein, F. Demonstration of 1.72 tbit/s optical data transmission under worst-case turbulence conditions for ground-to-geostationary satellite communications. IEEE Commun. Lett. 22(9), 1818–1821. https://doi.org/10.1109/LCOMM.2018.2847628 (2018).

Kaushal, H. & Kaddoum, G. Optical communication in space: Challenges and mitigation techniques. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 19(1), 57–96. https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2016.2603518 (2017).

Al-Gailani, S. A. et al. A survey of free space optics (fso) communication systems, links, and networks. IEEE Access 9, 7353–7373. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3048049 (2021).

Heine, F., Kämpfner, H., Czichy, R., Meyer, R. & Lutzer, M. Optical inter-satellite communication operational. In: 2010 Military Commun. Conf. (MILCOM) 1583–1587 https://doi.org/10.1109/MILCOM.2010.5680175 (2010).

Space Data Systems (CCSDS), C.C., et al. Optical high data rate (hdr) communication-1064 nm. Technical report, CCSDS 141.11-O-1, December (2018).

Günthner, K. et al. Quantum-limited measurements of optical signals from a geostationary satellite. Optica 4(6), 611–616. https://doi.org/10.1364/OPTICA.4.000611 (2017).

Marinis, L. D. et al. A silicon photonic 32-input coherent combiner for turbulence mitigation in free space optics links. IEEE Access https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3541870 (2025).

Metcalf, A. J. et al. Stellar spectroscopy in the near-infrared with a laser frequency comb. Optica 6(2), 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1364/OPTICA.6.000233 (2019).

Karlen, L., Onillon, E., Kundermann, S., Lecomte, S., Numata, K., Rodriguez, M., Yu, A., Shortt, B. & Mondin, L. LISA laser head metrology. In: International Conference on Space Optics – ICSO 2022 127773 https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2690348 (2023).

Bernhardt, B. et al. Cavity-enhanced dual-comb spectroscopy. Nat. Photon. 4(1), 55–57 (2010).

Wang, C. et al. Integrated lithium niobate electro-optic modulators operating at CMOS-compatible voltages. Nature 562(7725), 101–104 (2018).

Yamaguchi, Y., Zhu, P., Dat, P.T., Takano, S., Hirata, S., Kataoka, Y., Ichikawa, J., Shimizu, R., Akahane, K., Yamamoto, N., Kanno, A. & Kawanishi, T. Fully Packaged 100-GHz-Bandwidth EO-Equalizer- Integrated TFLN Modulator with Record-High Slope Efficiency Enabling 200-GBaud Signaling. In: Optical Fiber Communication Conference (OFC) Postdeadline Papers 2025. https://doi.org/10.1364/OFC.2025.Th4D.4 (2025).

Yamada, S. & Minakata, M. Dc drift phenomena in linbo3 optical waveguide devices. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 20(4), 733. https://doi.org/10.1143/JJAP.20.733 (1981).

Xu, M. et al. High-performance coherent optical modulators based on thin-film lithium niobate platform. Nat. Commun. 11(1), 3911 (2020).

Shi, J. et al. Alleviation of dc drift in a thin-film lithium niobate modulator utilizing Ar+; ion milling. Opt. Lett. 50(5), 1703–1706. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.549975 (2025).

Kincaid, P.S., De Marinis, L., Contestabile, G., Dubois, F., Zarebidaki, H., Sattari, H. & Andriolli, N. Design of an efficient thin film lithium niobate modulator at 1064 nm. In: 2025 30th OptoElectronics and Communications Conference (OECC) and 2025 International Conference on Photonics in Switching and Computing (PSC) 1–4 https://doi.org/10.23919/OECC/PSC62146.2025.11111384 (2025).

Jagatpal, N., Mercante, A. J., Ahmed, A. N. R. & Prather, D. W. Thin film lithium niobate electro-optic modulator for 1064 nm wavelength. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 33(5), 271–274. https://doi.org/10.1109/LPT.2021.3056913 (2021).

Yan, H., Pan, B., Xie, Y., Liu, L., Zhi, L. & Dai, D. Thin-film lithium-niobate-on-insulator modulators at a wavelength of 1064nm for high-power applications. In: 2023 Opto-Electronics and Communications Conference (OECC) https://doi.org/10.1109/OECC56963.2023.10209981(2023).

Zhang, B. et al. High-bandwidth cmos-level integrated thin-film lithium niobate electro-optic modulator at 1064 nm wavelength. Opt. Laser Technol. 191, 113335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2025.113335 (2025).

Zhu, D. et al. Integrated photonics on thin-film lithium niobate. Adv. Opt. Photon. 13(2), 242–352. https://doi.org/10.1364/AOP.411024 (2021).

Zhang, M., Wang, C., Kharel, P., Zhu, D. & Lončar, M. Integrated lithium niobate electro-optic modulators: When performance meets scalability. Optica 8(5), 652–667. https://doi.org/10.1364/OPTICA.415762 (2021).

Volk, M. F., Suntsov, S., Rüter, C. E. & Kip, D. Low loss ridge waveguides in lithium niobate thin films by optical grade diamond blade dicing. Opt. Express 24(2), 1386–1391. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.24.001386 (2016).

Wang, M. et al. Chemo-mechanical polish lithography: A pathway to low loss large-scale photonic integration on lithium niobate on insulator. Quantum Eng. 1(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1002/que2.9 (2019).

Zhang, M., Wang, C., Cheng, R., Shams-Ansari, A. & Lončar, M. Monolithic ultra-high-q lithium niobate microring resonator. Optica 4(12), 1536–1537. https://doi.org/10.1364/OPTICA.4.001536 (2017).

Li, C., Liu, D. & Dai, D. Multimode silicon photonics. Nanophotonics 8(2), 227–247. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2018-0161 (2019).

Chang, L. et al. Thin film wavelength converters for photonic integrated circuits. Optica 3(5), 531–535. https://doi.org/10.1364/OPTICA.3.000531 (2016).

Contestabile, G., De Marinis, L., Kincaid, P. S. & Andriolli, N. Lithium niobate on insulator technology for applications in the 1064 nm window. In: 2024 IEEE Photonics Conference (IPC) 2 https://doi.org/10.1109/IPC60965.2024.10799907 (2024).

Meetei, T. S., Son, S.-J., Park, B., Lee, Y.-T. & Yu, N. E. Numerical analysis of a strip-loaded silicon rich nitride-thin film lithium niobate hybrid waveguides. J. Opt. 25(3), 035801. https://doi.org/10.1088/2040-8986/acb44b (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Amorphous silicon-lithium niobate thin film strip-loaded waveguides. Opt. Mater. Express 7(11), 4018–4028. https://doi.org/10.1364/OME.7.004018 (2017).

Li, S., Cai, L., Wang, Y., Jiang, Y. & Hu, H. Waveguides consisting of single-crystal lithium niobate thin film and oxidized titanium stripe. Opt. Express 23(19), 24212–24219. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.23.024212 (2015).

Li, C.-H., Ramachandra, S. H., Faruque, I. I., Dwivedi, S. & Arafin, S. Design of green light sources using nonlinear photonics and on-chip pump lasers. IEEE J. Select. Top. Quantum Electron. 28(1: Semiconductor Lasers) https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTQE.2021.3095793 (2022).

Zhang, K. et al. High-performance and fabrication-tolerant 3 db adiabatic coupler based on ultralow-loss silicon waveguide by tri-layer hard mask etching process. Nanomaterials https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15120947 (2025).

Payne, F. P. & Lacey, J. P. A theoretical analysis of scattering loss from planar optical waveguides. Opt. Quant. Electron. 26, 977–986 (1994).

Tang, Y. et al. High performance thin-film lithium niobate modulator with suppressed slot-line mode on quartz substrate fabricated by photolithography. J. Lightwave Technol. 43(2), 636–647. https://doi.org/10.1109/JLT.2024.3453032 (2025).

Wang, J., Chen, P., Dai, D. & Liu, L. Polarization coupling of x-cut thin film lithium niobate based waveguides. IEEE Photon. J. 12(3), 2200310. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPHOT.2020.2995317 (2020).

Cai, L., Kang, Y. & Hu, H. Electric-optical property of the proton exchanged phase modulator in single-crystal lithium niobate thin film. Opt. Express 24(5), 4640–4647. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.24.004640 (2016).

Chang, L. et al. Heterogeneous integration of lithium niobate and silicon nitride waveguides for wafer-scale photonic integrated circuits on silicon. Opt. Lett. 42(4), 803–806. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.42.000803 (2017).

Vanackere, T. et al. Heterogeneous integration of a high-speed lithium niobate modulator on silicon nitride using micro-transfer printing. APL Photon. 8(8), 086102. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0150878 (2023).

Funding

We acknowledge financial support under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 1.1, Call for tender No. 1409 published on 14.9.2022 by the Italian MUR, funded by the European Union – NextGenerationEU – Project PRIN 2022 PNRR “LINUS”, by the National Quantum Science and Technology Institute (NQSTI), through the PNRR MUR project PE0000023-NQSTI, by the Italian MUR in the framework of the FoReLab project (Departments of Excellence), by the European Union under the NRRP of the NextGenerationEU partnership on “Telecommunications of the Future” (PE00000001, program “RESTART”).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Numerical analysis implementation: P.S.K.; AFM scan analysis and analytical scattering model implementation: N.G.P.; writing—original draft preparation: P.S.K., N.G.P., G.C., N.A.; Funding acquisition: G.C., N.A. All authors contributed to the assessment of the analysis and writing and review of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kincaid, P.S., Pruiti, N.G., De Marinis, L. et al. Waveguide design for a TFLN platform at 1064 nm for applications in spacecom and spectroscopy. Sci Rep 16, 1930 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31754-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31754-z