Abstract

Can language be a valuable predictor of genetic diversity even at the level of extremely circumscribed areas of linguistic diversity? We report on the analysis of mtDNA and NRY variation extracted from the whole-genome sequencing of 27 natives of Grecìa Salentina, a geographic area in southern Italy home to a historic Greek-speaking community. With respect to mtDNA, we found similarities with samples from Central Italy and Eastern Balkan, mainly because of the high haplogroups N, K and J1 frequencies. Detailed phylogeographic analyses of these haplogroups reveal instances of Grecìa Salentina-specific lineages. With respect to the NRY, we find similarities with other samples from southern Italy, Anatolia and the Middle East, because of the overwhelming frequency of haplogroup J2a. The new J2a lineages, many of which are specific to Grecìa Salentina, greatly expand the phylogeny of the haplogroup. Haplogroup R1a is also overrepresented, with a new lineage belonging to the GML6 subclade, which is common in the Western Balkans. All the above haplogroups were long recognized as markers of post-Neolithic East-to-West movements through the Balkan Peninsula by land or off its coasts by sea. We conclude that the peculiar component detected in the Grecìa Salentina gene pool is the result of past immigration. Specifically, there was a demic contribution of both sexes, which foreshadows the build-up of an entire community, and subsequent dilution in the surrounding gene pool by admixture occurred only to a limited extent. These results add a genomic dimension to our knowledge of the identity of the Greek-speaking community settled in Grecìa Salentina. To date, the peculiarity of the Grecìa Salentina population was only its linguistic identity, but we now show that it is also supported by a genetic component. The more general hypothesis of a connection between the demic and linguistic structure of the area can now be tested by comparing the genetics of Grecìa Salentina to those of other linguistic enclaves of Balkan origin in southern Italy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

‘Grecìa Salentina’ (henceforth GS) is the label assigned to a geographic area in Apulia [Southern Italy (SI), 43,000 inhabitants] (Figs. 1, S1), where a Greek dialect (usually labelled Griko, see Supplemental text) has historically been spoken (and still is, although it is now less widespread than it was in the past).

Map of Italy and detail of southern Apulia with the position (red) of the 10 Greek-speaking municipalities belonging to Grecìa Salentina. Additional details are provided in Fig. S1.

The linguistic origins of the Greek-speaking communities of SI (traditionally located in GS and southern Calabria1 are controversial and essentially unsolved issues. Traditionally, two major hypotheses have been proposed in the literature2. One hypothesis is that the currently spoken Greek dialects are direct descendants of the Medieval Greek varieties introduced in SI during Byzantine rule, especially between the 9th and 11th centuries CE, when waves of Greek-speaking settlers, soldiers, monks, and administrators are believed to have migrated to the region3. According to this view, these dialects are essentially “Modern” Greek dialects, that originate from the same linguistic source as most present-day Greek varieties (i.e., the so-called Hellenistic Koiné). The other hypothesis is that these dialects derive from the Greek-speaking communities that settled in SI as a consequence of the First Great Colonization started in the 8th century BCE4. Linguistically, this would imply that they originate from ancient Greek varieties that were spoken before the “linguistic unification” brought about in Hellenistic times through the Koiné. Although the debate in the literature has been intense, no unambiguous evidence has thus far emerged to support the direct descent of the present-day Greek varieties of SI from ancient rather than medieval Greek dialects. In fact, the Greek language left multiple layers of influence across SI, which have interacted and blended with other languages (especially Latin and its descendant Romance dialects) at various diachronic stages5, making it almost impossible to determine whether the current dialect represents a continuation of earlier Greek linguistic components or results from later transplants6,7.

The uniparentally transmitted portions of the genome [mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and the nonrecombining portion of the Y chromosome (NRY)] are each inherited as single loci and, as far as they are carried in a haploid state, cannot be reshuffled with homologs by recombination. With the advent of genome-wide analyses of diversity, the information conveyed by variants in mtDNA and the NRY is diluted among millions of autosomal variants. Nevertheless, they continue to be considered markers of choice to clarify the formation of gene pools in human locales, in Italy and elsewhere8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. This is because (i) they inform specifically on female- and male-borne contributions to the gene pools and (ii) the descent of the particular arrangements of variants carried by each subject can be reconstructed as a strict phylogeny, in which the appearance of each branch (node) can be confidently dated assuming a molecular clock. This power is further enhanced when the full array of variants is characterized by complete resequencing, reaching the maximal density of markers. This enables the detection of recent affinities, revealed by the sharing of derived alleles in the most terminal branches. The geographical positioning of populations in which samples displaying such phylogenetic closeness are found, can be compared with known historical events to infer when separation from a common ancestor may have occurred. Assuming a monophyletic origin, if the shared derived alleles can be supposed to be younger than a given date, the timing of the migration responsible for their spread can be given an upper bound in the past. In this way one can distinguish more recent from more ancient dispersal events, even if they impacted the same area.

The GS community was already the subject of uniparental genetic surveys, using pre-defined lists of known SNPs. For both mtDNA15 and the NRY15,16 diversity indexes similar to other non-linguistically isolated Italian samples were obtained. Onto an haplogroup frequency background similar to other SI samples, an increase of Y-chromosome haplogroups J2a15 and R1b-M412* were reported. This latter was considered compatible “with the early Hellenistic colonization and/or the more recent Byzantine domination”16.

In this work, we report on the analysis of mtDNA and NRY variation extracted from the whole-genome sequencing of a sample of native GS (Table S1), with the aim of clarifying some questions about the sources of the biological legacy of GS. The first and foremost question refers to the presence of a signal that distinguishes it from the general SI background in the GS gene pool. It is to be expected that this appears as the presence of a minority of genetic types attributable to distinctive ancestral sources. Should such a signal be found, subordinate questions would have to refer to the particular population sources and the time frame for a genetic input to GS, and whether both sexes contributed it. We then searched for GS-specific mtDNA and NRY molecular types (Tables S2, S3) and analysed them in the context of phylogenies resulting from studies carried out at the same level of resolution.

Bearing in mind that the history of a population does not necessarily coincide with the history of its language, our description of the genetic endowment of the GS community could represent a valuable step towards more directly investigating the mechanisms underlying the historical transmission of the Greek in SI within a conceptual framework that integrates insights from both genetics and linguistics.

Results

Mitochondrial DNA

The results of the haplogroup assignment of the 27 mitogenomes are reported in Tables 1 and S2. In agreement with a previous report15, typical western Eurasian branches (H, HV, I, J, K, N1, R0a, T, U, W, and X) largely predominate, with the possible exception of a single representative of haplogroup U6, for which a western Eurasian origin has been proposed, followed by reintroduction in northern Africa17,18. Haplogroups of either sub-Saharan (L) or Northern African (M) origin, not represented in our population sample, are instead found at low (0.01–0.03) frequencies in Central-Southern Italy and Iberia, increasing to 10% in some Middle Eastern populations (Table S4).

To determine the haplogroup distribution of GS in the context of European and Mediterranean mtDNA diversity, we summarized data from the literature with principal component analysis (PCA). The results (Figure S2) clearly separate North Africans from the rest of populations on PC1. PC2 clearly summarizes an east/south-east to north gradient, with populations from the Arabian Peninsula and southern Asia at the bottom centre and those of northern Europe at the top right. The projected GS sample falls in an area of the plot together with Central Italy and the Eastern Balkan samples of Bulgaria, Ukraine, Romania and North Macedonia, mainly because of the high frequencies of haplogroups K, J1 and H.

An Fst analysis based on the complete set of haplogroup distributions (Table S4) at this level of classification, revealed the least nonsignificant differentiation between the GS and all the Italian samples, plus Greece and Macedonia. Nonsignificant differences are also observed with several populations from the Middle East and the Balkan Peninsula and north of it, up to Lithuania and Ukraine. On the other hand, significant differentiation is observed with North Africa, northwestern Europe and the Arabian Peninsula.

Haplogroups N, K, and J1 accounted for 37% of all the haplogroups in GS, a value exceeding the aggregated frequency of the same haplogroups in any other sample. We then asked whether a finer phylogenetic analysis of the types recovered in GS could provide clues regarding their geographic origins.

N1b1a

Haplogroup N has frequencies less than 6% among the 53 populations represented in Fig. S2, with the exception of the Lebanese, Georgian and Syrians (0.06–0.09) and the outlying Sudanese. The two mitogenomes in our series belong to the N1b1a clade. Many N1b1a branches are shared between Europeans and Near Easterners, and the Near East, as the likely homeland of N1b1a, has been favoured on the basis of ancient specimens19. A tree including modern and ancient N1b1a mitogenomes is shown in Fig. S4.

Among the GS mitogenomes, one (16 as numbered in Table S1) carries the 195 C variant but neither the 1406 C nor the 16,126 C and is thus to be classified as a representative of a sister clade of both N1b1a7 and N1b1a8 (Fig. 2). This mitogenome is also derived at five different positions (723T, 2223G, 9336G, 9525 A, and 16249 C), which is consistent with the average length of the other sequences in the 195 C clade. It thus qualifies as a GS-specific haplogroup.

The second subject (24) belongs to a clade (N1b1a5b in HRAS) characterized by 12,007 A, together with samples from Italy and Northern Europe (Fig. 2). Within this clade, subject 24 shares the 143 A variant with only two other sequences sampled in the USA in a clinical screening (not shown). N1b1a5 was dated to 2 Kya19, but it appears to be more widespread and deeper here.

In our analysis, we also included N1b1a9 (four sequences sampled in Sardinia and one in Serbia) whose basal node (14323 A) was dated to 9.39–7.25 Kya. This figure thus serves as a reference for the fast radiation within N1b1a, evident in our tree. Two sequences, from the Turkish Neolithic (I0708) and Danish Middle Ages (MK059572) are basal in the radiation.

In conclusion, the two GS mitogenomes appear to be quite recent and likely postdate the entry of Neolithic farmers through the Balkans20.

K1b1c

K1b1c appears to be grossly overrepresented in GS, with 5 (18.5%) carriers noted out of the 27 fully sequenced subjects and 3 (23%) carriers of the three founding variants among 13 additional subjects. This compares to the limited observations among modern samples from the Caucasus, Turkey and southern Balkans and a few instances of ancient sequences in the Ancient mtDNA database (amtDB)21. In particular, K1b1c accounts for a small portion of K, whose overall frequency is less than 10% in Europe. This haplogroup was claimed to track the demic movements responsible for the Neolithic transition in Europe22 with a dual route through the Balkans by land and the Mediterranean by seafaring20,23.

Our K1b1c mitogenomes belong to the K1b1c7 subclade (Fig. S5). Three of them (4, 12 and 20) are identical, whereas one carries the 11,137 C variant and one the 7754 A variant. These two mutations are never observed except in other haplogroups. All of our K1b1c mitogenomes share the 14,258 A variant, which is not found in any of the rest of the K1b1c sequences. In the overall tree, the three sequences from ancient samples (PCA0053, I10866, I3582) map outside all modern K1b1c7 sequences. Downstream of the node defined by the 94 A variant the tree has a markedly star-like structure. The age of this radiation is between 12.4 and 7.0 Kya for the basal node of K1b1c6 and K1b1c7, and between 5.0 and 2.5 Kya for a small group of Sardinian representatives of K1b1c19 (Fig. 2). Note that the radiation is also strongly geographically structured, with sequences forming small clades sharing sampling locations near each other, indicating that parallel processes occur independently locally. Only two sequences sampled in Serbia are basal, tracking the route to Central Europe.

We used TaqMan assays to search for K1b1c among 69 subjects from Greek-speaking communities in Calabria (Grecanici) and found a null frequency (AN, VS in prep).

In conclusion, the particular K1b1c subtypes reported here qualify as a GS-specific subhaplogroup, which possibly persisted in the GS community undergoing recent and limited radiation. In the absence of other observations, whether the 14,258 A variant arose outside or within GS remains to be determined (see Supplemental text).

J1

We found three mitogenomes affiliated with different clades within haplogroup J1 (Fig. S6). Overall, J1 accounted for < 10% in the 53 populations shown in Fig. S2, with the exception of the Lebanese, Ukrainian and North Central European populations. An extremely star-like structure for J1 among 28 mainly European representatives was already reported24 and attributed to a Paleolithic matrilineal expansion.

One GS subject (1) carries a subtype of J1c9 characterized by the 951 A variant (J1c9b in HRAS), shared with JQ797871 sampled in Apulia (Fig. 2). The GS subject, however, also carries the 6050 C variant, which is not present in JQ797871. One subject (21) carries a J1c10 mitogenome (Fig. 2), which is very rare throughout Southeastern Europe. The closest relative is KF451147, which was sampled in the Near East (HGDP Bedouins). However, subject 21 has the 16527 T variant, whereas KF451147 has the 5563 A and 9554 A variants. A third subject (9) carries a J1d mitogenome, which is typical of the Arabian Peninsula, although at low frequencies. The affinity of this mitogenome with sequences from the Middle East, but also North Africa and Sicily is confirmed (Fig. 2), but it departs from a basal node and is characterized by 5 private variants.

In conclusion, the particular J1c9 subtype reported here qualifies as a GS-specific subhaplogroup, with a geographically close molecular relative. On the other hand, the J1c10 mitogenome is also GS-specific but its closest relative is from the Eastern edge of the Ancient Greek world. Also the J1d GS mitogenome is GS-specific and may represent a possible direct link with the Middle East, though not recent (Fig. 2).

Other haplogroups

Two subjects carried a Hg W mitogenome. In particular, the W1c mitogenome had the 16193 T variant and was more precisely classified as W1c3. Among the 11 mitogenomes in this clade in HRAS, 10 were from the Balkan Peninsula and one was from Turkey. The V mitogenome shares the 11404G variant with a sequence from Iran (KC911406) but has four additional derived variants.

We found nine mitogenomes belonging to haplogroup H (32%), a frequency consistent with the declining pattern from Western Europe towards the Near East and the Caucasus25. In Italy, frequencies ranging from 33% to 55% have been reported15,26. A precise reconstruction of the origin of haplogroup H is still lacking. Conservatively, we consider the assemblage of GS haplogroup H mitogenomes a signal of the general Italian mtDNA background into the GS gene pool (see Supplemental text).

Y chromosome

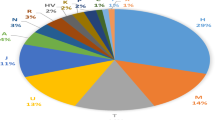

Among the 20 GS males, we identified 16 different haplogroups (Tables 2 and S3) using a coarse level of identification to allow immediate comparisons with the literature.

The results of PCA based on a classification into 34 haplogroups are shown in Figure S3. PC1 clearly summarizes a longitudinal east-to-west gradient, spanning from Iran and Anatolia to North Central Europe and the Iberian Peninsula. Despite living at similar longitudes, the Balkan and SI populations are widely separated on PC2, as this is dominated by the differential occurrence of haplogroups I-P37 and R1a (Fig. S3, inset). The projected GS sample falls in an area of the plot populated by Italian samples, closer to the Apulian and Ionian Calabrian samples. More northerly, Italian samples lie towards Central European samples. Note that in the data entered in the PCA, only the haplogroup J2 subclades J2-M410 and J2-M12 are considered, i.e., an insufficient classification to faithfully describe the diversity recovered in GS (see below).

An Fst analysis based on the full set of haplogroup distributions (Table S5) at this classification level revealed a greater proportion of significant (p < 0.05) pairwise contrasts compared with mtDNA, consistent with the well-known stronger Y chromosome structuring. The least nonsignificant differentiation was found between the GS and all the SI samples, including Sicily, plus Crete and Anatolia. Significant differences were observed between GS and both Northern Italy (Fst’s > 0.08) and Western Europe (Fst’s > 0.20 for France and > 0.14 for Spain). In line with the PC plot, comparisons with Balkan samples revealed significant Fst values, because of the contribution of haplogroup I.

Haplogroups J2 and R1a account for more than 50% of all the haplogroups in GS, a value exceeding the aggregated frequency of the same haplogroups in any other population. Also in this case, we performed a finer phylogenetic analysis of the types recovered in GS, searching for clues to their geographic origins. However, in view of the large number of variants resulting from complete sequencing, we limited our analysis to those enabling immediate comparisons with the published literature.

Hg E

The two observations of haplogroup E refer to the E-M78 lineage, with one falling into the E-V13 subclade. The frequencies of this latter peak among Macedonians, Continental and Aegean Island Greeks (but not Cretans), Bulgarians and Albanians27 and account for approximately 90% of all E-M78 males. Conversely, in Italy, this proportion is only approximately 50%. The phylogeography of these two E clades suggests that Western Asians carrying E-V13 reached the Balkans after 17.0 Kya but expanded into Europe no earlier than 5.3 Kya.

Hg J

Within haplogroup J, we did not observe representatives of J1, a lineage that would testify to immediate connections with the Middle East and the Arabian Peninsula28,29. Conversely, J2 is the clade with the greatest number of observations (8/20 = 40%), doubling the average reported for Italian regions30 and higher than previous reports in GS15,16. None of the 20 males carried J2b-M12. Interestingly, 7 of our 8 cases lacked the M67 variant and fell into the heterogeneous J2a-M410(xM67) lineage group (Fig. 3). This is rather unexpected, as J2-M67 accounts for a relevant proportion of all J2 in Italy, Turkey, Bulgaria, and Greece11,12,16,31,32,33,34,35. In the Western Balkans, strong heterogeneity has been reported across populations and studies, with the contribution of J2a-M67 to the overall frequency of J2a ranging from 0% to 57%, which is occasionally accounted for entirely by the subclade J2a-M9236,37. Medieval movements in the area may be responsible for such heterogeneity38. No M67 carriers were reported among 28 haplogroup J2a males from Lebanon39.

Approximate positions of the eight J2 Y-chromosomes recovered in GS (numbered as in Table S1) on the maximum parsimony tree of the haplogroup by Finocchio et al. (2018). Branch-defining markers are boxed in grey. The provenance of each branch-defining subject in the original tree is reported. The estimated ages of relevant nodes are also shown. The depth of the newly added branches is arbitrary.

Two of the J2a observations (1 and 6) fall into the J2a-L397 clade, which is also identified by the peculiar 6-repeat allele at DYS445 in some studies. This clade was considered a marker of population movements from Anatolia to Greece12 and from here to the rest of the western Mediterranean40. The frequency of this clade in our sample greatly exceeds that reported previously12,33,39. We confirmed the high frequency of this variant in GS (13%) by directly typing it in an expanded series of 36 males.

A fine dissection of the J2a-L397 lineage41 attributed its presence in SI to Greek colonizers. A basal branch was defined by a total of 9 SNP variants, including L397. Here, one of the J2a-L397 chromosomes (subject 1) splits this basal branch (Fig. 3), as it carries the ancestral state at 3 of the 9 SNPs, i.e., rs768053437 (Z423), rs769850957 and rs775324890. The new lineage carried by this subject thus defines a Grecìa-specific haplogroup. The other J2a-L397 chromosome (6) is further derived and is related to a single chromosome sampled in Greece, belonging to a rare terminal branch otherwise found almost exclusively in SI [branch 58, defined by rs775512766, (Fig. 2 in ref41)]. Here, this terminal branch is split, as the new subject carries the derived state only at 3 [rs752917236 (PH2725), rs777859510 (F801) and rs770808691] of the nine positions that previously defined the branch.

Two subjects (12 and 24) were located on the J2a-M319 branch, sharing 13 of the 45 variants with a previously identified Turkish subject. Many of the same variants are shared with 9 of 28 Lebanese J2a39, one (EGAN0001235049) of 11 Greek J2a42, one (APPG7555919) of 3 Iraqi J2a43 and one (Y21100000492520) of 25 Central Asian J2a44.

The J2-M92 chromosome falls downstream of branch 9841, defined by the derived state at rs1039640322, a variant not yet catalogued by ISOGG. Furthermore, this same subject does not carry any of the variants defining the four downstream branches; thus a fifth branch is identified. One subject (17) was located in a small subclade downstream of the PF5007 node. Here, a long branch defined by 25 variants, none of which are reported by ISOGG, leads to an additional node. Only a single Italian and Turkish subject were previously found to belong to this small clade41. The closest relatives of this lineage (sharing the variants rs1013856758, rs926847533, and rs915578291) were found among Lebanese (ERS617422) and Greeks (EGAN00001235017). One subject (2) belonged to a second clade undescribed by ISOGG. This subject carried derived alleles at all 22 sites defining this branch but did not match any of the two downstream branches previously found in a Greek and a Turkish subject41. Closely related lineages, sharing a majority of the 22 variants, were found in the Lebanese (ERS617415) and Greek data (EGAN00001235025, EGAN00001235028). Finally, subject 8 was assigned a basal position in the J2a-L26 clade, as he carries the derived allele at the immediately downstream marker Z6064 and other markers defining J2a1a2a1~ in ISOGG. He thus differs from both sister lineages departing from L26 (Fig. 3). This lineage is characterized, among others, by the derived state at Y32713, Y32714 and Y33274. Only three Saudis carrying the same markers are recorded at www.yfull.com/tree/J-Y32707.

In summary, in addition to their increased frequency, the J2a chromosomes found here rewrite the phylogeny of internal branches of J2a and serve as representatives of a novel and poorly known quota of diversity in a lineage strongly implicated in the movements of people in the Mediterranean space. With the caveat of the particular sampling scheme for the tree noted in Fig. 3, the GS chromosomes show closer affinities with previous specimens sampled in Greece, Turkey and Lebanon than in Italy. In particular, phyletic affinities with both Lebanon and Greece were found in two cases (J2-M410xL26, J2-L26xM67), with Greece and SI in two cases (J2-L397) and with the Middle East in three cases (J2-M319, J2-L26*); the J2-M92 was uncertain. The node ages set an upper bound of 6.3 Kya41,45 for the appearance of at least 4 of the 8 J2a chromosomes. Altogether, the 8 J2a chromosomes are compatible with a radiation that may have occurred at least in part in GS.

R1a

We found three R1a chromosomes (3/20 = 15%), in line with a previous report16. All these chromosomes belong to the terminal branch R1a-M558, which currently occupies Central-Eastern Europe with frequencies of up to 40%46,47. This clade was dated to 4.0 Kya (C.I. 3.4–4.7 Kya)45 and is currently considered a signal from the present-day Slavic population in Central Europe47. In more detail, the three chromosomes carry the derived state at three markers (rs556726425, rs763333432 and rs566690499), which correspond to branch GML6 in the R1a1 tree48. Conversely, they lack the markers further downstream in this clade, as well as the marker (rs770125881) corresponding to GML7, thus defining a novel branch within the GML6 clade. The most closely related chromosomes, among those entirely sequenced here surveyed, were found in a Greek (EGAN00001235046)42 and a Central Asian (Y21100000492573)44 subjects, sharing the GML6 markers.

Inferences on the origins of the three GS chromosomes must consider that R1a1-GML6* is the predominant R1a1 subtype in Slovenia, Hungary, Romania and Belarus, where R1a1 accounts for up to 25% of all Y chromosomes. In Italy, where the overall frequency of R1a1 is less than 10%, one-third of the chromosomes were reported to belong to R1a1-GML6*48.

R1b

We found five representatives of haplogroup R1b, each belonging to a different subclade. Among these, R1b-L23(xM412) is present at low frequencies in the Balkan Peninsula and east49. R1b-U152 is prevalent (20%) in France and sharply decreases in frequency along the Italian Peninsula, reaching 8.8% in Apulia16. The remaining three branches are all prevalent in extreme Western Europe. Considerably discrepant dates for R1b-L23(xM412) and R1b-S116(xU152, M529) were obtained using different methods45,49. A date of 6.5 Kya was reported recently for L2350 in a founder population that is yet to be identified. As with mtDNA haplogroup H, we conservatively consider the assemblage of R1b chromosomes a signal of the general Italian background into the GS gene pool.

Discussion

The idea of coinheritance of genes and languages through generations has long inspired human population genetics research50,51. By analysing the complete variation in the two uniparentally transmitted portions of the genome, we generated information that adds a genomic dimension to our knowledge of the Greek speaking community in Grecìa Salentina.

In the entire northern Mediterranean, the superimposition of multiple migratory pre- and historical east-to-west movements has led to a genetic landscape referred to as the “Mediterranean genetic continuum”52. Markers with the appropriate age and geographic distribution may be able to resolve at least some of these layers. For example, in GS, this is key for distinguishing between Greek colonial and Byzantine migrations by checking whether the most derived lineages are shared with mainland/Aegean Greece or other areas under past Byzantine domination.

Our Fst analyses (Tables S4, S5) confirm a general similarity between GS and other SI samples15,16. The novelty of the present work lies in the identification of rare, phylogenetically defined lineages that detect peculiar components of the gene pool that are useful for tracking at least a fraction of a population’s ancestry. Such signals may be easily missed when whole population samples are examined exclusively in a frequentist fashion or when potentially useful autosomal markers are diluted into large, often preselected, arrays. The uniparental signals we detected in the GS population allow a first set of firm conclusions concerning the development of its gene pool, along with others that await further testing.

First, we found clear instances (in N1b1a, K1b1c and J1 for mtDNA and in J2 and R1a1 for the NRY) of GS-specific lineages that distinguished this community from the current surrounding genetic landscape of SI. A likely explanation is that people from external population(s) of the Mediterranean space settled in, leaving a distinctive genetic legacy that survived until today. Data from the literature on complete mitogenomes or NRY sequences for the Aegean area (on the opposite side of the Greek peninsula, with respect to Italy) are scarce. Given that Eastern Aegean coasts were a relevant stepping stone in the Western expansion of the Greek world in the 1 st millennium BCE, such information would help in discriminating between a contribution from an area directly involved in the foundation of Magna Graecia (i.e., Anatolia) and a later contribution from elsewhere.

Second, the observation that both maternally and paternally transmitted portions of the genome provided signals of admixture denotes a contribution of both sexes, which foreshadows the build-up of an entire community and not, e.g., a military conquest or the settlement of sailors only. However, one can suppose that it is possible that male and female movements were not synchronous, with one sex being more involved in the initial settlement, followed by the fetching of other societal components. This scenario implies the possibility of different geographical areas as sources for female- and male-borne lineages. With the caveat of the different population samples in the two PCA plots (Figs. S2, S3), a very general sense of affinity with Balkan populations emerges for mtDNA but is not so evident for the NRY.

Third, the very presence of the particular haplogroups that reveal these contributions (see above) suggests that dilution in the surrounding gene pool by admixture occurred only to a limited extent; i.e., the community likely retained a closed marriage structure that hindered the massive entry of genes from the outer population. Previous studies28,53 have shown the role of sex-biased cultural processes in the distribution of intra- and intergroup diversity for uniparental markers, and a variegated pattern of social and reproductive segregation of Greek colonists in some locations emerged from the analysis of ancient specimens related to the colonial period of the 8th to 6th centuries BCE38. On the other hand, our knowledge about the history of the GS municipalities (Fig. 1) testifies that they have experienced minimal isolation from each other over time54,55. Their proximity and the lack of natural barriers probably facilitated movement and communication, solidifying the bonds between municipalities within the Greek-speaking community.

Fourth, the frequencies of the particular haplogroups that reveal these contributions may not directly mirror those in the group of immigrants that contributed them, as the small population size and ensuing genetic drift likely modified the frequency of the surviving haplogroups and caused the extinction of other, unrecognized ones56, both in GS and in the source areas (see Supplemental text). The effects of drift can be captured in extant populations of SI13,57,58. Additionally, strong between-group heterogeneity has been shown in at least two of the candidate source regions, namely northern Greece59 and the Peloponnese60.

In summary, although the major questions of “wherefrom” and “when” the admixture began are largely open, there are now working hypotheses to address them analytically, lineage by lineage. For example, at least two mtDNA lineages (J1c10 and J1d) found their closest relatives in the Middle East. For the Y chromosome, haplogroup R1a provides a signal of affinity with Greece and the Balkans. At the same time, haplogroup J2 provides diverse signals of affinity, in some cases with Greece while in others with Lebanon, Iraq, the Arabian Peninsula and Central Asia. In these latter instances, the available phylogeographic data favour direct Near East-to-GS connections, with little evidence for intervening colonization of mainland Greece. Thus, based on molecular similarity alone, at the present stage, the results are compatible with both immigration in the Greek colonial (supposedly from mainland Greece) and Byzantine (supposedly from the easternmost fringes of the empire) periods. Historical accounts can be scanned for hints on pushes for the supposed displacement of people (e.g. the repeated earthquakes that destroyed the densely populated city of Antioch in the early Middle Ages).

The finding of an external demic contribution to GS is a major discovery because it ultimately highlights unprecedented genetic parallelism to the evident linguistic diversity of the area from the Romance-speaking surroundings: now, one needs to take into account the possibility that the arrival of the Greek language to Salento may have been the product of a recognizable fully demic and possibly double-gendered colonization. Although it is still possible that the arrival of the people and the language to GS were two coincidental processes along similar routes, the other linguistic enclaves of Balkan origin in SI provide some ground to test the hypothesis of a single causal event for both language and population replacement. Specifically, further evidence at the finest possible genetic resolution must be compared to ascertain how many of the peculiar genetic lineages of GS are shared with Grecanico speakers in Calabria, although not with the Albanian-speaking Arbereshe52. Additionally, speakers of South-Slavic in Molise may represent a useful benchmark to address this question. The possible sharing of lineages between the two Greek-speaking communities, in contrast to the others, would favour the view of a cause-effect relationship between genetic and language diversity at such a small geographic and population-size scale.

Methods

Sampling

Sampling was performed in two temporally distinct campaigns. The first one was performed in 1994. The use of these samples, collected decades ago, in genomic studies was approved by the Ethical Committee Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo (protocol number 0028298/22). The results regarding Y chromosome variation in this series, obtained by typing individual markers, were previously presented [labelled GS, n = 82 in ref16. The second one began in 2019, is still ongoing and currently consists of 75 subjects. This design was applied to control for gross shifts among localities and across generations. In both cases, written informed consent was obtained after the aims and scopes of the project were illustrated to the participants and their communities. Research procedures and the form for informed consent were approved by the local Ethics Committee (Comitato etico ASL Lecce, verbali n. 34 4/7/2019; n. 35 del 25/7/2019; n. 41 14/1/2020).

All the research was performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations reported in the abovementioned documents and those agreed upon by the scientific community. In this respect, because the present work did not involve any issue relevant for the donor’s health, only the relevant prescriptions of the WMA Declaration of Helsinki and COE Oviedo Convention were obeyed.

Biological samples (buccal swabs) were anonymized upon collection. DNA was prepared with standard methods. Exclusively based on DNA quality, eight (7 M, 1 F) and nineteen (13 M, 6 F) out of the 82 samples from the first and 75 from the second campaigns, respectively, were entered into the whole-genome sequencing pipeline.

The project received the endorsement of the Union of the Municipalities (https://www.unionegreciasalentina.le.it/).

Library construction, alignment and variant calling

Each sample was prepared according to the Illumina TruSeq DNA sample preparation guide to obtain a final library with a 300–400 bp average insert size. Multiple indexing adapters were ligated to the ends of the DNA fragments to prepare them for hybridization onto a flow cell.

The BCL/cBCL (base call) binary files were converted into FASTQ files using the Illumina package bcl2fastq2-v2.20.0. The demultiplexing option (--barcode-mismatches) was set to perfect match (value: 0).

Paired-end sequences generated by the HiSeq instrument were mapped to the human genome using iSAAC aligner (iSAAC-04.18.11.09 (c) 2010–2017 Illumina, Inc.) with the UCSC assembly hg38 (Dec. 2013) reference sequence.

Strelka (2.9.10 (c) 2009–2018 Illumina, Inc.) was used to identify single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and short insertions and deletions (indels). Variant mitochondrial DNA positions were obtained by alignment to the rCRS61. Summary results of the sequencing effort are reported in Table S1.

Haplogroup inference

For mitochondrial haplogroup assignment, Haplogrep3 was used62, with PhyloTree 17 - Forensic Update 1.263, using the list of variants reported in Table S2. Whenever a finer classification could be obtained with some of the markers (e.g. K1b1c according to Haplogrep3, refined to K1b1c7 in the Haplogroup Research Analytical Suite, HRAS, https://hras.yseq.net/), the Haplogrep3 nomenclature was retained (compare Table 1 with Figs. S4-S6 and Supplemental text).

For the Y chromosome, haplogroup affiliation was obtained with the Y-SNP Haplogroup Hierarchy Finder64, which is based on the ISOGG tree 11 Jul 2020 Version 15.73. The most derived marker was annotated (Table S3), but information on lineage identification is also provided using markers that allow immediate comparisons with specific publications.

Additional assays

Custom TaqMan allele discrimination assays were designed to directly detect the mtDNA variants 94 A, 3337 A and 11,914 A, basal to haplogroup K1b1c in additional subjects. Additionally, for the Y chromosome haplogroup J2a, the L397 variant was directly searched in an enlarged group of males with the TaqMan assay C__61531938. Both assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The reactions were run under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, 40 cycles of denaturation at 92 °C for 15 s, and a single annealing and extension step at 60 °C for 90 s. The genotype was assigned by registering the fluorescence emission from each sample at the corresponding VIC and FAM dye wavelengths.

Tree construction

For mtDNA, accessions of complete sequences for the recognized haplogroups and those sharing derived markers were identified in HRAS and downloaded from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore. Additional sequences from related clades, dated in the relevant publications, were included. Sequences for ancient samples affiliated with the relevant haplogroups were obtained from amtDB21. To make sure that relevant closely related sequences were not missed, we performed a megaBLAST search by using as queries the GS sequences affiliated with haplogroups N, K and J1. For each haplogroup a non-redundant set of sequences with similarity above a given threshold (≥ 99.89%, ≥ 99.91% and ≥ 99.93% for N, K and J1, respectively) was assembled (Table S6). This search did not result in a major increase of representatives of clades relevant to GS. Sequences identified in clinical screenings or with more than 2% missing calls were omitted. Alignments with MUSCLE and maximum parsimony tree construction were performed with MEGA X65. In the alignment, 21 bp corresponding to positions 301–321 of the rCRS containing a (C)n stretch were excluded. For haplogroup J1, position 16,519 was not considered, following Phylotree63 (phylotree.org/tree/JT.htm). A list of sequences (Table S6) with discordant G185A and C13934T calls was also excluded, as they generated an artefactual clade not consistent with the known phylogeny.

For the Y chromosome haplogroup J2, the GS chromosomes were superimposed on the tree proposed in ref41., by considering variants falling in the bait fragments considered therein. The search for related lineages was performed on a marker-by-marker basis in the fully sequenced population samples of Middle Easterners39,43, Greeks42, Central Asians44 and the Tuscans of the 1,000 Genomes Project66.

To evaluate the population specificity of haplogroups, we refer to the conceptual scheme outlined in ref19.

Data analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed with the R program princomp. For mitochondrial DNA, the pooling of data in refs24,26 [Tables S3 and S1, respectively] at the coarser level of resolution in either of the two was used as a reference (Table S4). Populations from sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia were not considered in the analysis to avoid inflation of PC1. Populations with the same label in the two papers were combined into one. After the 27 GS mitogenomes were adjusted to the classification of the same table, the latter were projected in the PC space. Pairwise Fst values were calculated with the same data with Arlequin67 by using haplogroup affiliation as a categorical variable, without considering the mutational distance between haplogroups.

The same procedure was applied to Y chromosome haplogroups, using data reported in the literature16,68 [Tables S5 and S1, respectively]. The frequencies are reported in Table S5. The original GS frequencies were not used in the PCA to avoid pseudoreplication.

Data availability

The genotyping results, haplogroup affiliations and reference population frequencies are reported in Tables S1–S5 in the spreadsheet attached to the manuscript. The complete mitogenome sequences were submitted to GenBank and received Acc. N. PV521797-PV521823.

References

Rohlfs, G. Griechische Grammatik Von Großgriechenland (Max Niemeyer, 1977).

Manolessou, I. The Greek dialects of Southern italy: an overview. KAMPOS: Camb. Papers Mod. Greek. 13, 103–125 (2005).

Horrocks, G. Greek: A History of the Language and its Speakers 2nd edn (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010).

Rohlfs, G. Griechen Und Romanen in Unteritalien (L.S. Olschki, 1924).

Fanciullo, F. On the origins of modern Greek in Southern Italy. First Int. Conf. Mod. Greek Dialects Linguistic Theory. 67–77. https://doi.org/10.26220/mgdlt.v1i1.2512 (2001).

Guardiano, C. & Stavrou, M. Dialect syntax between persistence and change. The case of Greek demonstratives. L’Italia Dialettale. 81, 121–158 (2020).

Guardiano, C. & Stavrou, M. Modeling syntactic change under contact: the case of Italiot Greek. Languages 6, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6020074 (2021).

Sarno, S. et al. Shared language, diverging genetic histories: high-resolution analysis of Y-chromosome variability in Calabrian and Sicilian Arbereshe. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 24, 600–606. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2015.138 (2016).

Capocasa, M. et al. Detecting genetic isolation in human populations: A study of European Language minorities. PLoS ONE. 8, e56371. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056371 (2013).

Balanovsky, O. et al. Parallel evolution of genes and languages in the Caucasus region. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2905–2920. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msr126 (2011).

Sarno, S. et al. An ancient mediterranean melting pot: investigating the uniparental genetic structure and population history of Sicily and Southern Italy. PLoS ONE. 9, e96074. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0096074 (2014).

King, R. J. et al. Differential Y-chromosome Anatolian influences on the Greek and Cretan neolithic. Ann. Hum. Genet. 72, 205–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-1809.2007.00414.x (2008).

Sarno, S. et al. Genetic history of Calabrian Greeks reveals ancient events and long term isolation in the Aspromonte area of Southern Italy. Sci. Rep. 11, 3045. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-82591-9 (2021).

Coia, V. et al. Evidence of high genetic variation among linguistically diverse populations on a micro-geographic scale: a case study of the Italian alps. J. Hum. Genet. 57, 254–260. https://doi.org/10.1038/jhg.2012.14 (2012).

Brisighelli, F. et al. Uniparental markers of contemporary Italian population reveals details on its pre-Roman heritage. PLoS One 7, e50794 and correction in PLoS One. 52014 Jan 50717;50799(50791):50710.51371, (2012). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0050794

Grugni, V. et al. Reconstructing the genetic history of italians: new insights from a male (Y-chromosome) perspective. Ann. Hum. Biol. 45, 44–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/03014460.2017.1409801 (2018).

González, A. M. et al. Mitochondrial lineage M1 traces an early human backflow to Africa. BMC Genom. 8, 223–223. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-8-223 (2007).

Olivieri, A. et al. The MtDNA legacy of the Levantine early upper palaeolithic in Africa. Science 314, 1767–1770. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1135566 (2006).

Olivieri, A. et al. Mitogenome diversity in sardinians: a genetic window onto an island’s past. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 1230–1239. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msx082 (2017).

Hofmanová, Z. et al. Early farmers from across Europe directly descended from neolithic Aegeans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 113, 6886–6891. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1523951113 (2016).

Ehler, E. et al. AmtDB: a database of ancient human mitochondrial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D29–D32. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky843 (2018).

Isern, N., Fort, J. & de Rioja, V. L. The ancient Cline of haplogroup K implies that the neolithic transition in Europe was mainly Demic. Sci. Rep. 7, 11229. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11629-8 (2017).

Paschou, P. et al. Maritime route of colonization of Europe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 111, 9211–9216. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1320811111 (2014).

Batini, C. et al. Population resequencing of European mitochondrial genomes highlights sex-bias in bronze age demographic expansions. Sci. Rep. 7, 12086. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11307-9 (2017).

Modi, A. et al. The mitogenome portrait of Umbria in central Italy as depicted by contemporary inhabitants and pre-Roman remains. Sci. Rep. 10, 10700. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67445-0 (2020).

Colombo, G. et al. The origin of modern North Africans as depicted by a massive survey of mitogenomes. Sci. Rep. 15, 27025. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12209-x (2025).

Cruciani, F. et al. Tracing past human male movements in northern/eastern Africa and Western eurasia: new clues from Y-chromosomal haplogroups E-M78 and J-M12. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1300–1311. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msm049 (2007).

Chiaroni, J., Underhill, P. A. & Cavalli-Sforza, L. L. Y chromosome diversity, human expansion, drift and cultural evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106, 20174–20179. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0910803106 (2009).

Sahakyan, H. et al. Origin and diffusion of human Y chromosome haplogroup J1-M267. Sci. Rep. 11, 6659. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-85883-2 (2021).

Capelli, C. et al. Y chromosome genetic variation in the Italian Peninsula is clinal and supports an admixture model for the Mesolithic-Neolithic encounter. Mol. Phyl Evol. 44, 228–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2006.11.030 (2007).

Semino, O. et al. Origin, diffusion, and differentiation of Y-chromosome haplogroups E and J: inferences on the neolithization of Europe and later migratory events in the mediterranean area. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 74, 1023–1034. https://doi.org/10.1086/386295 (2004).

Onofri, V. et al. Y-chromosome genetic structure in sub-Apennine populations of central Italy by SNP and STR analysis. Int. J. Legal Med. 121, 234–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-007-0153-y (2007).

Tofanelli, S. et al. The Greeks in the west: genetic signatures of the Hellenic colonisation in Southern Italy and Sicily. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 24, 429–436. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2015.124 (2016).

Cinnioglu, C. et al. Excavating Y-chromosome haplotype strata in Anatolia. Hum. Genet. 114, 127–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-003-1031-4 (2004).

Karachanak, S. et al. Y-chromosome diversity in modern bulgarians: new clues about their ancestry. PLoS ONE. 8, e56779. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056779 (2013).

Pericic, M. et al. High-resolution phylogenetic analysis of southeastern Europe traces major episodes of paternal gene flow among Slavic populations. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22, 1964–1975. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msi185 (2005).

Battaglia, V. et al. Y-chromosomal evidence of the cultural diffusion of agriculture in Southeast Europe. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 17, 820–830. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2008.249 (2009).

Lazaridis, I. et al. A genetic probe into the ancient and medieval history of Southern Europe and West Asia. Science 377, 940–951. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abq0755 (2022).

Haber, M. et al. Continuity and admixture in the last five millennia of Levantine history from ancient Canaanite and present-day Lebanese genome sequences. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 101, 274–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.06.013 (2017).

King, R. J. et al. The coming of the Greeks to Provence and corsica: Y-chromosome models of archaic Greek colonization of the Western mediterranean. BMC Evol. Biol. 11, 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-11-69 (2011).

Finocchio, A. et al. A finely resolved phylogeny of Y chromosome hg J illuminates the processes of phoenician and Greek colonizations in the mediterranean. Sci. Rep. 8, 7465. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25912-9 (2018).

Gilly, A. et al. Cohort-wide deep whole genome sequencing and the allelic architecture of complex traits. Nat. Commun. 9, 4674. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07070-8 (2018).

Almarri, M. A. et al. The genomic history of the middle East. Cell 184, 4612–4625e4614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.07.013 (2021).

Zhabagin, M. et al. Ancient components and recent expansion in the Eurasian heartland: insights into the revised phylogeny of Y-chromosomes from central Asia. Genes (Basel). 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13101776 (2022).

Karmin, M. et al. A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture. Genome Res. 25, 459–466. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.186684.114 (2015).

Underhill, P. et al. The phylogenetic and geographic structure of Y-chromosome haplogroup R1a. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 23, 124–131. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2014.50 (2014).

Šarac, J. et al. Genetic heritage of Croatians in the southeastern European gene pool-Y chromosome analysis of the Croatian continental and Island population. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 28, 837–845. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.22876 (2016).

Lall, G. M. et al. Subdividing Y-chromosome haplogroup R1a1 reveals Norse Viking dispersal lineages in Britain. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 29, 512–523. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-020-00747-z (2021).

Myres, N. M. et al. A major Y-chromosome haplogroup R1b holocene era founder effect in central and Western Europe. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 19, 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2010.146 (2011).

Lazaridis, I. et al. The genetic origin of the Indo-Europeans. Nature 639, 132–142. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08531-5 (2025).

Cavalli-Sforza, L. L. Genes, peoples, and Languages (University of California Press, 2001).

Sarno, S. et al. Ancient and recent admixture layers in Sicily and Southern Italy trace multiple migration routes along the mediterranean. Sci. Rep. 7, 1984. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01802-4 (2017).

Coia, V. et al. Demographic histories, isolation and social factors as determinants of the genetic structure of alpine linguistic groups. PLoS ONE. 8, e81704. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0081704 (2013).

Aprile, M. Grecia Salentina: lingua, identità E Cultura Tra Passato E Futuro (Edizioni Esperidi, 2015).

Romano, A. Univerity of Turin, in Contatti linguistici e dinamiche sociolinguistiche (eds S Corino, A De Angelis, & M Viale) 211–224 (2019).

Pandey, D., Harris, M., Garud, N. R. & Narasimhan, V. M. Leveraging ancient DNA to uncover signals of natural selection in Europe lost due to admixture or drift. Nat. Commun. 15, 9772. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53852-8 (2024).

Di Giacomo, F. et al. Clinal patterns of human Y chromosomal diversity in continental Italy and Greece are dominated by drift and founder effects. Mol. Phyl Evol. 28, 387–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00016-2 (2003).

Anagnostou, P. et al. Evaluating MtDNA patterns of genetic isolation using a re-sampling procedure: A case study on Italian populations. Ann. Hum. Biol. 44, 140–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/03014460.2016.1181784 (2017).

Panoutsopoulou, K. et al. Genetic characterization of Greek population isolates reveals strong genetic drift at missense and trait-associated variants. Nat. Commun. 5, 5345. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6345 (2014).

Stamatoyannopoulos, G. et al. Genetics of the Peloponnesean populations and the theory of extinction of the medieval Peloponnesean Greeks. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 25, 637–645. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2017.18 (2017).

Andrews, R. M. et al. Reanalysis and revision of the Cambridge reference sequence for human mitochondrial DNA. Nat. Genet. 23, 147. https://doi.org/10.1038/13779 (1999).

Schönherr, S., Weissensteiner, H., Kronenberg, F. & Forer, L. Haplogrep 3 - an interactive haplogroup classification and analysis platform. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, W263–W268. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkad284 (2023).

van Oven, M. & Kayser, M. Updated comprehensive phylogenetic tree of global human mitochondrial DNA variation. Hum. Mutat. 30, E386–E394. https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.20921 (2009).

Tseng, B. et al. Y-SNP haplogroup hierarchy finder: a web tool for Y-SNP haplogroup assignment. J. Hum. Genet. 67, 487–493. https://doi.org/10.1038/s10038-022-01033-0 (2022).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C. & Tamura, K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1547–1549. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy096 (2018).

Byrska-Bishop, M. et al. High-coverage whole-genome sequencing of the expanded 1000 genomes project cohort including 602 trios. Cell 185, 3426–3440 (2022).

Excoffier, L. & Lischer, H. E. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and windows. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 10, 564–567. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02847.x (2010).

Hallast, P. et al. The Y-chromosome tree bursts into leaf: 13,000 high confidence SNPs covering the majority of known clades. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 661–673. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msu327 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the donors for their enthusiastic participation in this investigation. We thank Mark Haber and Chris Tyler-Smith for providing the Y chromosome sequencing data in vcf format.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Union – Next Generation EU, Progetti PRIN 2022 PC2TSX to AN, PRIN 2022 BZYFBE to OS and National Center for Gene Therapy and Drugs based on RNA Technology, CN3 – Spoke 7 (code: CN00000041) to MHC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization of the work: AN, EdA, OS, VSWet DNA work: CJ, EM, FZAnalysed the data: FM, GC, MGManagement of computational facilities and support: GP, MH-CProvided reagents (samples): BT, FC, OS, VSWrote the paper: AN, CG, GL, OS, All authors read and approved the last version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

To obey all the prescriptions of the EU General Data Protection Regulation, we planned appropriate safeguards for processing data under the research exemption. The samples have been anonymized. Only dedicated, restricted-access bioinformatic infrastructures were used. Electronic data management was supervised by an institutional technology director.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Menato, F., Pepe, G., Mercuri, E. et al. Rare uniparental lineages reveal external ancestries in the gene pool of the Italian linguistic enclave of Grecìa Salentina. Sci Rep 16, 1528 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31756-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31756-x