Abstract

In the current work, Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) were developed using copper ferrite as the primary anode material. Due to its high resistivity and low eddy current loss, copper ferrite is suitable for high-frequency applications. Pure and Eu-doped CuFe2O4 nanocomposites have been successfully synthesized by the hydrothermal method. The synthesized nanomaterials were comprehensively characterized to evaluate their structural, morphological, and elemental properties utilizing various advanced analytical techniques. X-ray diffraction analysis was employed to determine the materials’ crystallographic structure and phase purity. The observed reflections in the XRD pattern confirm the successful formation of the tetragonal phase of copper ferrite, with no detectable secondary phase and impurity peaks. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was conducted to investigate the surface morphology and topographic features, while Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), coupled with SEM, enables qualitative and quantitative elemental analysis. As revealed by SEM, the surface morphology exhibits a beaded architecture characterized by vertical stacking of nanorods arranged in sequential, overlapping manners. The charge storage capacity, cyclic stability, and redox behavior of synthesized nanomaterials as an anode in lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) were systematically evaluated using galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) measurements and cyclic voltammetry (CV). The CuFe₂O₄ nanocomposites doped with 3 mol% Eu (CuFe₂O₄-3 mol% Eu) exhibited a high specific discharge capacity of 850 mAh g−1 and demonstrated an excellent cyclic stability, retaining 97% of its capacity over 100 cycles at 0.1 Ag-1. This study indicates that the EuxCu1-xFe₂O₄ nanocomposite exhibits an optimal balance between high initial energy storage and long-term electrochemical stability, highlighting its potential as an efficient anode material in lithium-ion batteries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Today, clean energy production is a vital issue globally, and researchers increasingly focus on renewable energy sources in response to the global energy problem1. Efficient and cost-effective energy storage is crucial to overcoming the intermittent nature of renewable energy, ensuring a reliable supply during fluctuations, and minimizing energy waste as production scales2. Batteries have undergone significant advancements in recent years, making remarkable progress and becoming a focal point of interest in the sustainability of various technologies such as vehicles, renewables, wearables, and portables3. Innovations in battery research and development are enhancing energy storage systems, producing higher energy densities, improved performance, longer lifespans, and faster charging times4. Rechargeable lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) have emerged as the leading energy storage technology prized for their superior charge density (100 to 265 Wh/kg), long cycle life (400 to 1200 charge cycles), low self-discharge rate, and fast charging, making them indispensable across a range of modern applications5,6. These batteries are widely used in portable electronics, electric vehicles, and renewable energy storage systems. Due to their superior energy density, longer cycle life, lack of memory effect, and higher voltage output, lithium-ion batteries outperform other rechargeable technologies such as lead-acid, nickel–cadmium, and sodium-ion batteries, making them the most advanced and suitable choice for modern energy storage applications7,8,9.

In lithium-ion batteries, the materials used for electrodes are crucial for performance metrics. The common cathode materials used are lithium cobalt oxide (LiCoO₂), lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO₄), and various oxides of nickel, cobalt, and manganese (NCM). The LiCoO₂ suffers from poor thermal stability, high cost, and toxicity10. LiFePO₄ is limited by its lower energy density and poor inherent electronic conductivity, which can significantly constrain its rate performance11. NCM offers an optimal balance between energy density, structural stability; however, their reliance on cobalt continues to pose challenges related to cost, sustainability, and sourcing12.

For anodes, graphite is the most used material due to its low price, good cycle stability, and relatively low volume change after alloying with lithium; it suffers from only limited capacity and can form lithium dendrites at rapidly high charge rates as a safety risk13. Silicon-based materials and metal oxides have been evaluated as complementary alternatives with higher capacity, but generally experience mechanical volume expansion and poor cycle stability at these levels14.

Despite their many advantages, lithium-ion batteries still face several challenges. These include aging, capacity fading, and safety concerns, primarily due to the degradation of electrode materials during repeated charge and discharge cycles. Furthermore, the limited availability and high cost of essential raw materials, such as lithium, cobalt, and nickel, create further difficulties.

To solve these problems, researchers are actively investigating advanced electrode materials and nanocomposites that can enhance battery performance and improve the stability of electrochemical reactions. Recent studies have explored strategies such as neutral doping and creating defects in materials to improve the structural and electrochemical properties of LIBs.

Among various materials being studied, copper ferrite (CuFe₂O₄) has attracted significant interest. Due to its unique spinel structure, excellent thermal and chemical stability, and promising electrochemical behavior. Its potential has also been demonstrated in other fields, including memory storage systems and microwave devices.

In the current work, copper-ferrite (CuFe₂O₄) is proposed as an alternative electrode material based on its spinel structure to provide high resistivity with low eddy current loss for high-frequency applications. However, CuFe₂O₄ also suffers from drawbacks such as low electrical conductivity and capacity loss during cycling. To address these issues, this research introduces europium (Eu) doping to improve the structural stability, enhance electrical conductivity, and boost the overall electrochemical performance of CuFe₂O₄-based electrodes in lithium-ion batteries.

Experimental work

Material

Iron (III) chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3 · 6H2O), Copper (II) chloride-2-hydrate (CuCl2·2H2O), Sodium hydroxide (NaOH), Ethanol (C2H5OH), and Europium (III) nitrate pentahydrate (Eu (NO3)3·5H2O) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. The distilled water was used to prepare the required solutions.

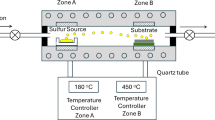

Synthesis of CuFe2O4 and its nanocomposites

A hydrothermal technique was performed to prepare the CuFe2O4 NPs—the stoichiometric amount (2:1) of FeCl3. 6H2O and CuCl2·2H2O were dissolved in 30 mL of distilled water under constant magnetic stirring. When the precursor was dissolved, 16 mL of 1 M sodium hydroxide was added, and the mixture was agitated for 30 min. Then, a particular amount of Eu (NO3)3·5H2O was added to the above solution. After that, the solution was transferred to a Teflon-lined autoclave and heated for two hours at 200 °C. Once the liquid had cooled to room temperature, the contaminants were eliminated by washing with distilled water and ethanol. The final product was then allowed to air dry in an oven set at 60 °C for 12 h. The catalyst was produced by calcining at 700 °C for seven hours. The schematic prestation of synthesis of CuFe2O4 is shown in Fig. 1.

After calcination, CuFe2O4 NPs and their nanocomposites were subjected to characterization. Fourier transform infrared spectra were employed to analyze chemical bonds and functional groups. An X’Pert X-ray diffractometer acquired XRD patterns using Cu-Kα radiation for composition and crystal characteristics. Morphological analysis and elemental mapping were captured using a scanning electron microscope and an energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscope. UV–Vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (UV–Vis DRS) was employed to examine the optical absorption and determine the bandgap energy of the samples. The surface chemical composition, oxidation state, and electronic structure were analyzed using X-ray photoelectron microscopy.

Results and discussion

Characterization of synthesized materials

The FT-IR spectra recorded for the CuFe2O4 nanoparticles ranged from 400 to 4000 cm−1. Figure 2(a) illustrates the FTIR examination of pure CuFe2O4 and CuFe2O4-Eu nanocomposites. Ferrites typically exhibit two infrared (IR) modes within the 400 to 600 cm⁻1 range, which correspond to the metal–oxygen ion vibrations in two distinct sub-lattices termed tetrahedral and octahedral15,16. Two absorption bands are observed in the Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectra. The band near 585 cm⁻1 is associated with the stretching vibration of (Fe–O) in the tetrahedral site, while the band around 426 cm⁻1 is attributed to the octahedral site of the stretching vibration of (Cu–O). These FTIR spectra confirm the existence of a spinel structure17. The FTIR results did not alter when Eu was added. As is well known, FTIR can identify polar bonds, and metallic Eu lacks them. Therefore, the FTIR results are unaffected by the addition of Eu.

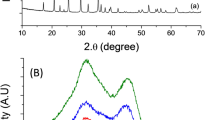

Figure 2(b) depicts the XRD pattern for pure CuFe2O4 and CuFe2O4–Eu samples. The XRD results verified that the sample was successfully transformed into the desired ferrite. The spectrum confirms the creation of a spinel ferrite in a single phase characterized by the space group Fd-3 m. The XRD analysis of CuFe2O4 nanoparticles displayed peaks at 35.61°, 54.08°, 57.57°, 62.47°, and 72.04°, which correspond well to the crystal planes (211), (312), (321), (224), and (332) hkl planes. All diffraction peaks can be attributed to the tetragonal structure of CuFe2O4 (space group 141/amd), which closely aligns with the literature values (JCPDS No. 00–034-0425, with lattice parameters a = b = 5.844 Å and c = 8.630 Å)17.

Additionally, certain secondary impurities, such as Fe2O3, were still detected, likely due to the insolubility of FeO. Secondary phases exhibited peaks at 2θ = 24.13°, 33.15°, 40.86°, 49.46°, 64.03°, and 75.45°, corresponding to (012), (104), (113), (024), (300), and (220) crystal planes. The diffraction peaks can be attributed to the rhombohedral structure of the Fe2O3 phase (JCPDS file 00–033-0664 with lattice parameters a = b = 5.035 Å and c = 13.748 Å)18. The presence of secondary phases in the XRD pattern may result from interaction between the raw materials during the formation of copper ferrite, leading to metal oxide impurities. Also, the XRD patterns showed no identifiable diffraction peaks for the Eu dopant. The absence of Eu diffraction peaks in the as-synthesized copper ferrite could be due to low doping concentration or their incorporation into interstitial positions or substitution for existing cation sites.

Using the Debye–Scherrer formula, the width at half height (FWHM) of the synthesized CuFe2O4 spinel ferrite was used to determine the crystallite size.

In this formula, λ is the wavelength of the X-ray source (0.154 nm), β is the line broadening measured at FWHM in radians, θ is the peak position in radians, D is the average crystallite size of CuFe2O4 spinel ferrite in nanometers, and k is the shape factor (set at 0.94). The mean crystallite size for CuFe2O4 NPs was 38, 38, 41, 33, and 40 nm, respectively. The detailed lattice parameters are given in the supporting information (Table S1-S5).

UV–visible absorption spectra reveal the optical characteristics of CuFe2O4 and CuFe2O4-Eu nanocomposites. Figure 3a presents the absorption spectra for CuFe2O4 and CuFe2O4-Eu samples. For the pure CuFe2O4 nanoparticles, distinct UV absorption peaks are detected at 380 and 575 nm19. As we add dopant Eu with a concentration of 1 mol %, peaks are seen at 372, 378, and 581 nm. As the europium concentration is increased to 3 mol %, peaks are observed at 380 and 576 nm. At a europium concentration of 5 mol %, a broad peak at 379 nm and another at 577 nm. The CuFe2O4 composite with 3 mol% dopant and NiO as electrode material shows peaks at 379 and 573 nm.

By using the absorption spectra, the direct energy band gap was determined. The band gaps (Eg) were calculated using the equation (αhυ)2 = A( hυ − Eg ). In the equation, Eg is the optical bandgap of the samples, hv is the photon energy, A is a constant, α is the absorbance level, and n is a variable that varies according to the kind of electronic transition. The band gap energies are determined by graphing (αhν) against eV and extending the straight section of the graph to intersect the x-axis (Fig. 3b). The pure CuFe2O4 nanoparticles have a bandgap (Eg) of 2.43 eV20, while the Eg for the composite samples was around 2.49 eV, 2.27 eV, 2.35 eV, and 2.39 eV.

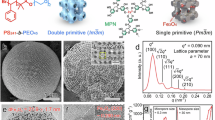

The SEM images of pure and Eu-doped CuFe2O4 nanoparticles are shown in Fig. 4(a-d). SEM images show that pure CuFe2O4 and Eu-doped CuFe2O4 NPs exhibit a spherical shape with irregular and spherical shapes, a beaded structure, and a high surface area Fig. 4(a-d). They have varying particle sizes and arrangements, with larger particles interspersed among smaller ones. The surface morphology remains unchanged after doping, and the compact structure indicates a large surface area Fig. 4(c-d). Europium addition alters CuFe2O4 structure 21,22. Elemental mapping suggests a homogeneous dispersion of europium, copper, iron, and oxygen throughout the sample matrix. This uniform elemental distribution is crucial for ensuring consistent magnetic and optical properties across the material.

Figure 5a-b shows the EDS spectra of the synthesized CuFe2O4 Eu-doped CuFe2O4 sample. The EDS spectra of the prepared sample show the presence of Cu, Fe, and O elements. Besides the previously mentioned elements, the presence of Eu is also detected in the composite samples. These findings confirm the successful formation of CuFe2O4 and Eu-doped CuFe2O4 with a little impurity.

Figure 6(a-d) presents TEM micrographs of 3 mol% Eu-doped CuFe₂O₄ at varying magnifications, revealing the nanostructured morphology of the synthesized ferrite. The TEM micrograph of the nanoparticles shows that the synthesized nanoparticles are nearly spherical, tend to form soft agglomerates due to magnetic interactions, range in size from 0.5–2 µm, and exhibit a smooth surface texture due to proper dispersion. A clear lattice fringe was observed in the HRTEM image (Fig. 6(e–g), indicating its high crystallinity. The sharp and continuous fringes confirm the highly crystalline nature of the nanoparticles. These observations on structure match the XRD results, which indicate Fd3̄m symmetry of the spinel and crystallite sizes (30–40 nm), as estimated through Scherrer analysis. The STEM images show a very large, almost spherical nanoparticle; the overall morphology is relatively uniform, though the surface appears slightly textured or crystalline at the edges (Fig. 6h–l)23,24,25. The TEM images of 3 mol% Eu-doped CuFe2O4 composite with NiO at different magnifications are given in S.14 of the supplementary information.

The XPS survey spectra of Eu-doped CuFe2O4 nanocomposites indicates the presence of oxygen (O), copper (Cu), iron (Fe), europium (Eu), and carbon (C) peaks, as illustrated in (Fig. 7). The peaks located at 932.8 eV and 952.9 eV are associated with Cu 2p3/2 and Cu 2p1/2, indicating the presence of Cu (II) species and confirming that the oxidation state of Cu in CuFe2O4 is + 2. Additionally, two notable strong satellite peaks were observed at 940.9 eV and 961.0 eV, corresponding to the Cu2p3/2 and Cu2p1/2 spin–orbit components26. The Fe spectrum exhibited two main peaks at 721.3 eV (Fe 2p1/2) and 714.9 eV (Fe 2p3/2), aligning with iron’s presence in its + 3 oxidation state27. The O peak at 529.3 eV reflects the metal oxides’ typical lattice oxygen peak28. All measured binding energies for Cu, Fe, and O indicate that these elements are chemically bonded. Additionally, a minor satellite peak for C was noted at 284.8 eV, originating from the XPS instrument, due to unintended hydrocarbons29. The introduction of europium resulted in two peaks, specifically Eu 3d3/2 and Eu 3d5/2, consistent with the presence of Eu in the + 2 oxidation state. The two prominent asymmetric peaks are located at 1134.2 eV (Eu 3d3/2) and 1125.2 eV (Eu 3d5/2)30. We have added the XPS results in a newly added table in the manuscript in Table S6, showing the atomic ratios of all detected elements, including Eu, for each doping concentration.

Electrochemical performance

The electrochemical performance of CuFe2O4 was evaluated using a series of electrochemical testing. The electrochemical performance of Eu-doped copper ferrite was assessed using a galvanostatic discharge charge within a voltage range of 0.01–3.0 V relative to Li/Li+.

The electrochemical performance of CuFe2O4 at different concentrations of europium is shown in Fig. 8. Figure 8a presents the discharge and charge profiles for pure CuFe2O4 synthesized by the hydrothermal method at 200 °C, with a voltage range of 0.01–3.0 V, for the 1st, 2nd, 10th, 50th, and 100th cycles. The initial discharge capacity was 780 mAh g–1, and the subsequent cycles showed discharge capacities of 656, 622, 518, and 510 mAh g–1 for the 2nd, 10th, 50th, and 100th cycles, respectively. Figure 8b shows the performance for the 1% Eu-doped CuFe2O4, with discharge capacities of 950, 766, 716, 672, and 624 mAh g–1 for the respective cycles. Figure 8c shows the discharge and charge profiles for the 3% Eu-doped CuFe2O4, where the discharge capacities were 1076, 845, 800, 756, and 710 mAh g–1. Figure 8d shows the discharge and charge profiles for the 5% Eu-doped CuFe2O4, with discharge capacities of 964, 789, 734, 611, and 590 mAh g–1 across the cycles. These results highlight the variations in performance as europium concentrations change. The detailed values are also given in Table S7.

The cycling performance of the pure CuFe2O4 and its nanocomposites with varying europium concentrations is shown in Fig. 9a. The pure CuFe2O4 exhibited a discharge capacity of 665 mA h g−1 and a Coulombic efficiency of 98% in the 100th cycle. With the addition of different concentrations of Europium, the discharge capacity of CuFe2O4 increased. At 1 mol% Eu, the discharge capacity was 770 mA h g−1 with a Coulombic efficiency of 97.7%. At 3 mol% Eu, discharge capacity was 850 mAh g−1 with a Coulombic efficiency of 99%. At 5 mol% Eu, discharge capacity was 795 mAh g−1 with a Coulombic efficiency of 97.2%.

This result demonstrates that the reversible capacity of the Eu-doped CFO electrodes is higher than that of pure CFO, and the most stable cycling performance is observed for the 3 mol% Eu-CFO sample. Enhanced performance can be ascribed to Eu2⁺ doping, which improves lithium-ion diffusion kinetics and electrical conductivity by creating oxygen vacancies and altering the electronic structure. Furthermore, moderate Eu doping (3 mol%) optimizes defect generation, enhancing Li⁺ transport and electrical conductivity, whereas excessive doping (5 mol%) may induce structural disorder, reducing performance. Thus, the superior electrochemical behavior of 3 mol% Eu-CFO compared to other doping levels can be attributed to these considerations.

The cycling performances of the CuFe₂O₄ electrodes were also evaluated under varied current densities: 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, and 5 A g⁻1. The performance rate of the CuFe₂O₄ electrode and its nanocomposites at varied current densities: 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, and 5 A g⁻1 is shown in Fig. 9b. At 0.1 A g⁻1, the capacities of pure CuFe₂O₄ and Eu-doped samples (1%, 3%, and 5% Eu) were 658, 766, 844, and 790 mAh g⁻1, respectively. As the current density increased, the capacities decreased but remained higher in the Eu-doped samples than in pure CuFe₂O₄. For instance, at 5 A g⁻1, the capacities were 478 mAh g⁻1 for pure CuFe₂O₄, 615 mAh g⁻1 for 1 mol% Eu, 665 mAh g⁻1 for 3% Eu, and 748 mAh g⁻1 for 5 mol% Eu. After 100 cycles, the capacities stabilized at 486 mAh g⁻1 for pure CuFe₂O₄, 630 mAh g⁻1 for 1 mol% Eu, 786 mAh g⁻1 for 3 mol% Eu, and 685 mAh g⁻1 for 5 mol% Eu at 0.1 A g⁻1. Notably, when the current density was reduced, the cell capacity returned to its initial values, indicating that the CuFe₂O₄ nanorod structure was maintained even after high-rate cycling (Table S7-S8).

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) analysis of the CuFe₂O₄ anode, conducted at a scan rate of 0.1 mV s⁻1 within a potential window of 0.01–3.0 V (Fig. 10), reveals comparable CV profiles across three cycles, with minor positional shifts and variations in peak intensities. The CV curves corresponding to pristine CuFe₂O₄ exhibit broad and diffuse redox peaks, indicative of sluggish and less defined electrochemical processes. In contrast, the incorporation of europium at increasing concentrations results in the emergence of sharper and more pronounced redox peaks, reflecting enhanced electrochemical kinetics and a more reversible redox behavior. This improved electrochemical response is associated with a more gradual and controlled lithium insertion/extraction mechanism, which contributes to mitigating electrode volume fluctuations during cycling, thereby suppressing mechanical degradation such as cracking and pulverization of the active material.

For the CuFe₂O₄ electrode without europium doping (Fig. 10a), the first cycle exhibits cathodic peaks at approximately 1.3 V and 0.7 V, and an anodic peak centered around 1.6 V. In subsequent cycles, the cathodic peaks shift to 0.9 V, while the anodic peaks shift to 1.7 V and 2.1 V, indicating enhanced electrochemical reversibility and good cycling stability. In the case of CuFe₂O₄ doped with 1 mol% europium (Fig. 10b), the initial CV profile displays cathodic peaks at 1.3 V and 0.6 V, accompanied by an anodic peak at 1.6 V. With continued cycling, the reduction peaks shift to 0.8 V, while the oxidation peaks appear at 1.7 V and 2.1 V, confirming improved redox reversibility.

For the sample containing 3 mol% europium (Fig. 10c), initial cathodic peaks are observed at 0.9 V and 0.5 V, with a corresponding anodic peak at 1.6 V. After cycling, the reduction peaks migrate to 0.7 V, while the oxidation peak remains at 1.6 V, demonstrating consistent electrochemical behavior and excellent cycling stability. In the case of 5 mol% Eu-doped CuFe₂O₄ (Fig. 10d), the initial CV cycle reveals three cathodic peaks located at 1.5 V, 1.1 V, and 0.5 V, along with an anodic peak at 1.5 V. Upon further cycling, the reduction peaks converge at approximately 0.7 V, and the oxidation peak shifts to 1.6 V, exhibiting minimal positional variation, which reflects good electrochemical reversibility and structural integrity (Table S9).

The observed shifts in redox peak positions across the cycles are primarily attributed to the changes in electrode kinetics and redox potential due to Eu doping, the structural reorganization of the electrode materials during the lithiation and delithiation processes. These electrochemical features affirm the beneficial role of Eu doping in enhancing the reversibility, kinetics, and overall cycling stability of the CuFe₂O₄ anode. The comparison of current research work with literature using different electrodes is shown in Table S11.

Post-cyclic analysis

Post-cyclic analysis was done to check the morphological stability of CuFe₂O₄ electrodes after 100 cycles. Both XRD and FESEM were used, and the results are presented in Figures S12 & SS13 of the supporting information. The FESEM images in Figure S12(a) and (b) clearly illustrate the impact of Eu doping on the morphological stability of CuFe₂O₄ electrodes after 100 cycles. The pristine CuFe₂O₄ electrode (Figure a) exhibits pronounced particle agglomeration and severe structural pulverization, suggesting considerable morphological degradation following cycling. In contrast, the 3 mol% Eu-doped CuFe₂O₄ sample (Figure b) retains a much finer, more uniform distribution of particles with minimal agglomeration. The improved microstructural integrity observed in the Eu-doped sample is indicative of enhanced cycling stability and better preservation of the electrode architecture, which can be attributed to the stabilizing effect imparted by Eu incorporation. These morphological improvements will likely contribute positively to electrochemical performance metrics such as capacity retention and long-term durability.

After extensive electrochemical cycling, CuFe₂O₄ electrodes typically experience significant structural changes, often leading to a partial or substantial loss of their long-range crystalline order. Post-cycling XRD patterns for undoped CuFe₂O₄ (Figure S13) tend to show greatly diminished or broadened diffraction peaks, reflecting a transition towards a more amorphous state due to pulverization, agglomeration, and repeated volume changes during cycling. This behavior is consistent with the observed FESEM morphology, where severe agglomeration and particle breakdown are apparent.

For Eu-doped CuFe₂O₄, the XRD patterns of post-cycled doped samples typically retain sharper diffraction peaks compared to undoped ones, suggesting a partial preservation of the spinel structure and delayed amorphization. However, even in doped samples, some peak broadening and reduced intensity may still occur, indicating that while crystallinity is better preserved, a transition towards a more disordered, possibly nanocrystalline or amorphous state can still take place, especially after prolonged cycling.

Mechanism for improved electrochemical performance

The stability of electrode material is a crucial factor for the long-term performance of devices and the commercial viability of electrochemical devices. A stable material should be able to retain its structure and chemical integrity during multiple charge/discharge cycles so that capacity is uniformly sustained and aging is avoided over time. Structural stability is the primary focus of our study on the synthesized europium-doped copper ferrite nanoparticles, as it serves as an indicator of their electrochemical potential. Rare-earth-doped compounds have been investigated due to their high oxygen-ion mobility and strong catalytic properties, which play a crucial role in chemical sensing31.

As observed in our X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern (Fig. 2b), the material has a complex structure. The pattern shows prominent diffraction peaks related to the cubic spinel structure of CuFe2O4 (JCPDS No. 00–034-0425). However, further minor peaks were seen. These peaks are due to a secondary phase, named as Fe2O3 phase (JCPDS file 00–033-0664). The doped samples did not show significant changes in the crystal structure. The presence of dopant ions could not be detected. These results confirm that the europium doping process does not disrupt the copper ferrite crystal structure but maintains its characteristic morphology and crystallinity. The formation of a multi-phase system indicates that the concentration of Europium dopant exceeds the copper ferrite lattice’s solubility limit under our given synthesis parameters. The development of a multi-phase system suggests that the concentration of the Europium dopant was greater than the solubility limit of the copper ferrite lattice under our given synthesis conditions. Such behavior is common in rare-earth-doped ferrites and provides a foundation for understanding the material’s electrochemical properties32,33.

The cyclic stability of Eu-doped copper ferrite was evaluated over long-term cycling at various current densities (mA g⁻1). As shown in Fig. 9a, the electrode provided an initial discharge capacity of 850 mAh g⁻1 and retained 97% of its capacity after 100 cycles. This stability is mainly because of the composite’s robust structural framework. Although the material does not exist as a single phase, the stable coexistence of two phases effectively accommodates the volume fluctuations during cycling, thereby suppressing pulverization and abrupt capacity fading. These findings confirm the promise of Eu-doped copper ferrite composites as durable anode materials34,35.

Conclusion

This dissertation represents the initial successful synthesis of stabilized Eu-doped spinel oxide nanoparticles through the hydrothermal method. The study involved phase identification, surface morphology analysis, crystallite size measurement, and energy band gap assessment, all using various characterization techniques. The observation of Bragg reflections confirms the cubic structure of the crystal, specifically corresponding to the space group Fd3m. The crystallite size is determined using Scherrer’s method. At lower concentration levels, the surface morphology features nanoparticles with irregular shapes and sizes, while at higher doping concentrations, nanorods of varying lengths are stacked on top of each other. Variations in the energy band gap with different dopant concentrations in nanoparticles can be ascribed to alterations in the electronic structure, elemental composition, particle size, and morphology. Electrochemical studies reveal that Eu-doped spinel oxides are promising candidates for use in rechargeable battery applications. Increasing the weight percentage of Eu opens further research opportunities focused on enhancing optical properties and improving the performance of rechargeable batteries. The electrochemical properties of the electrodes show a significant reversible capacity, excellent capacity retention, impressive rate performance, and cyclic capacity and efficiency. Electrochemical tests indicate that Eu-doped spinel oxides as electrode material outperform pure components, with reduced nanopores and crystallite sizes enhancing the performance of porous electrodes.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Xie, Z., Xu, W., Cui, X. & Wang, Y. Recent progress in metal–organic frameworks and their derived nanostructures for energy and environmental applications. Chemsuschem 10(8), 1645–1663 (2017).

Tasmania, H. Battery of the nation–Tasmanian pumped hydro in Australia’s future electricity market. 2018.

Horn, M., MacLeod, J., Liu, M., Webb, J. & Motta, N. Supercapacitors: A new source of power for electric cars?. Economic Analysis and Policy 61, 93–103 (2019).

Khan, M. Innovations in battery technology: enabling the revolution in electric vehicles and energy storage. British Journal of Multidisciplinary and Advanced Studies 5(1), 23–41 (2024).

Manthiram, A. An outlook on lithium ion battery technology. ACS Cent. Sci. 3(10), 1063–1069 (2017).

Tarascon, J.-M.; Armand, M. Issues and challenges facing rechargeable lithium batteries. nature , 414 (6861), 359–367 2001

Castaldi, M. et al. Power generation systems for L-MOXIE: concept proposal and trade-off analysis. In ASCEND 2021, 4186 (2021).

Bruce, P. G., Freunberger, S. A., Hardwick, L. J. & Tarascon, J.-M. Li–O2 and Li–S batteries with high energy storage. Nat. Mater. 11(1), 19–29 (2012).

Tarascon, J.-M. Key challenges in future Li-battery research. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2010(368), 3227–3241 (1923).

Julien, C. M., Mauger, A., Zaghib, K. & Groult, H. Comparative issues of cathode materials for Li-ion batteries. Inorganics 2(1), 132–154 (2014).

Bej, B.; Boxi, S. S. A short review on electrode materials and processing of Lithium-ion battery.

Warner, J. T. Lithium-ion battery chemistries: a primer; Elsevier, 2019.

Selinis, P. & Farmakis, F. A review on the anode and cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries with improved subzero temperature performance. J. Electrochem. Soc. 169(1), 010526 (2022).

Zhang, H., Mao, C., Li, J. & Chen, R. Advances in electrode materials for Li-based rechargeable batteries. RSC Adv. 7(54), 33789–33811 (2017).

Wang, Y., Zhao, H., Li, M., Fan, J. & Zhao, G. Magnetic ordered mesoporous copper ferrite as a heterogeneous Fenton catalyst for the degradation of imidacloprid. Appl. Catal. B 147, 534–545 (2014).

Selvan, R. K. et al. Synthesis and characterization of CuFe2O4/CeO2 nanocomposites. Mater. Chem. Phys. 112(2), 373–380 (2008).

Zeynizadeh, B., Gholamiyan, E. & Gilanizadeh, M. Magnetically recoverable CuFe2O4 nanoparticles as an efficient heterogeneous catalyst for green formylation of alcohols. Current Chem. Letters 7(4), 121–130 (2018).

Amulya, M. S. et al. Evaluation of bifunctional applications of CuFe2O4 nanoparticles synthesized by a sonochemical method. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 148, 109756 (2021).

Meidanchi, A. & Ansari, H. Copper spinel ferrite superparamagnetic nanoparticles as a novel radiotherapy enhancer effect in cancer treatment. J. Cluster Sci. 32(3), 657–663 (2021).

Ramadan, R., Uskoković, V. & El-Masry, M. M. Triphasic CoFe2O4/ZnFe2O4/CuFe2O4 nanocomposite for water treatment applications. J. Alloy. Compd. 954, 170040 (2023).

Oliveira, T. P. et al. Synthesis, characterization, and photocatalytic investigation of CuFe2O4 for the degradation of dyes under visible light. Catalysts 12(6), 623 (2022).

Lee, K., Muir, H. & Catalano, E. On the magnetic and chemical properties of Europium fluoride. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 26(3), 523–526 (1965).

Abbas, M. et al. Size-controlled high magnetization CoFe2O4 nanospheres and nanocubes using rapid one-pot sonochemical technique. Ceram. Int. 40(2), 3269–3276 (2014).

Moreno-Castilla, C., López-Ramón, M. V., Fontecha-Cámara, M. Á., Álvarez, M. A. & Mateus, L. Removal of phenolic compounds from water using copper ferrite nanosphere composites as fenton catalysts. Nanomaterials 9(6), 901 (2019).

Kurian, J. & Mathew, M. J. Structural, optical and magnetic studies of CuFe2O4, MgFe2O4 and ZnFe2O4 nanoparticles prepared by hydrothermal/solvothermal method. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 451, 121–130 (2018).

Elakkiya, V., Abhishekram, R. & Sumathi, S. Copper doped nickel aluminate: Synthesis, characterisation, optical and colour properties. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 27(10), 2596–2605 (2019).

Nakhate, A. V. & Yadav, G. D. Hydrothermal synthesis of CuFe2O4 magnetic nanoparticles as active and robust catalyst for N-arylation of indole and imidazole with aryl halide. ChemistrySelect 2(8), 2395–2405 (2017).

Kulkarni, S. & Ghosh, R. Ultra-sensitive CuAl2O4 Nanoflakes for ppb level detection of Isopropanol. Ceram. Int. 50(22), 46356–46363 (2024).

Potbhare, A. K. et al. Microwave-mediated fabrication of mesoporous Bi-doped CuAl2O4 nanocomposites for antioxidant and antibacterial performances. Materials Today: Proceedings 15, 454–463 (2019).

Mariscal, A. et al. Europium monoxide nanocrystalline thin films with high near-infrared transparency. Appl. Surf. Sci. 456, 980–984 (2018).

Wang, T. et al. Preparation of Yb-doped SnO2 hollow nanofibers with an enhanced ethanol–gas sensing performance by electrospinning. Sens. Actuators, B Chem. 216, 212–220 (2015).

Zubair, A. et al. Structural, morphological and magnetic properties of Eu-doped CoFe2O4 nano-ferrites. Results Phys. 7, 3203–3208 (2017).

Jacobo, S., Duhalde, S. & Bertorello, H. Rare earth influence on the structural and magnetic properties of NiZn ferrites. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 272, 2253–2254 (2004).

Rai, A. K. et al. High rate capability and long cycle stability of Co3O4/CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as an anode material for high-performance secondary lithium ion batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C 118(21), 11234–11243 (2014).

Ding, Y., Yang, Y. & Shao, H. Synthesis and characterization of nanostructured CuFe2O4 anode material for lithium ion battery. Solid State Ionics 217, 27–33 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Fatima Jinnah Women’s University, The Mall Rawalpindi, under FJWU Research grant 2025 entitled: ‘Design of Li-Batteries using multifunctional spinel oxides decorated with quantum dots as an electrode material’, National Center for Physics, Islamabad, Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE) under the 2023 Translational Research Program for the Energy sustainability Focus Area (Project ID: MMUE/240001), the 2024 ASEAN IVO (Project ID:2024-02), and Multimedia University, Malaysia.

Funding

This research was funded by Fatima Jinnah Women’s University, The Mall Rawalpindi, under FJWU Research grant 2025, and MOHE (Project ID: MMUE/240001), the 2024 ASEAN IVO (Project ID: 2024-02), and Multimedia University, Malaysia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The whole research work was carried out by **Hafsa Yasmeen, Dr Amna Bashir**, and Dr. Noshabah Tabassum , while Anjum Hussain and Dr Syed Mustansar Abbas, Dr Rabia Bashir helped in the applications of the synthesized materials. It Ee Lee, Qamar Wali, and Muhammad Aamir, provided facilitation for the characterization of materials and funding for this research work. Dr Imtiaz Ahmad provides help in TEM characterization of samples.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yasmeen, H., Bashir, A., Tabassum, N. et al. Tailoring and boosting the charge storage capacity of Li-ion batteries using EuxCu1-xFe2O4 as an electrode material. Sci Rep 16, 1945 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31760-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31760-1