Abstract

The in situ conversion process (ICP) is one of the most developed technologies to recover oil from fined grained, low thermally matured shale. However, mathematical models capable of predicting the production profile of oil and gas under the constraints of heating rate and temperature remain underdeveloped. Therefore, pyrolysis experiments with different heating rates (2 °C /d, 5 °C /d, 10 °C /d and 20 °C /d) were performed on shales from the seventh member of the Triassic Yanchang Formation (Chang 7 shale), a representative target for ICP implementation. The effects of heating rate and temperature on the production yields of oil, hydrocarbon gas, and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) were investigated, and mathematical prediction models to predict their production profiles were established. The results show that the influence of heating rate on oil production yield at fixed pyrolysis temperature exhibits stage-dependent characteristics across different temperature regimes: below 380 °C, the cumulative production yield decreases with increasing heating rate. However, above 380 °C, the cumulative yield increases with higher heating rates. In contrast to oil production, hydrocarbon gas production shows consistent inverse correlation with heating rate across all temperatures, and H₂S production shows positive correlation with heating rates. The mathematical models predict that when reaching the same thermal maturation of EasyRo = 2.3% (before complete oil cracking into gas), the maximum oil production yields reach 40.67 mg/g rock at 1 °C/d and 37.74 mg/g rock at 0.5 °C/d. Corresponding peak hydrocarbon gas production yields are 10.61 ml/g rock and 9.43 ml/g rock, respectively. Due to the formation mechanisms of H₂S, the predictive model is only applicable within heating rates of 5–20 °C/d. At rates below 2 °C/d, its production may become negligible. When designing optimized temperature program for ICP, the competing factors of oil production, hydrocarbon gas production and H2S yield should be carefully balanced.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although the global pattern of energy is transitioning toward low-carbon energy, oil and gas resources remain indispensable in the near term, continuing to serve as the primary source of global energy supply. The widespread implementation of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing has enabled hydrocarbon recovery from fine-grained, tight, and thermally matured shale formations, contributing to the rapid growth of oil and gas production. Beyond those recoverable resources, low to medium-matured shales (or oil shales) also contain substantial potential energy resource that could yield a trillion barrels of oil and gas equivalent1. However, these petroleum resources are not producible through drilling, as they predominantly exist as kerogen or viscous heavy bitumen. Artificially thermal maturation (retorting/pyrolysis) is required to break long-chain kerogen/bitumen molecules into smaller mobile oil, gas, and water molecules that are recoverable. The in-situ conversion technology is increasingly recognized as a promising approach for kerogen conversion and heavy oil upgrading, owing to its efficiency and environmental benefits. According to heating method, the in-situ conversion can be classified into three categories: conduction, convection, and radiant2,3. The classic conduction methods include Shell’s In-Situ Conversion Process (ICP) and ExxonMobil’s Electrofrac (electrically conductive fracturing) technology. The representative examples of convection methods include a process proposed by the Mining Technology Institute (MTI) of the Taiyuan University of Technology (TYUT) and Chevron CRUSH technology, and the superheated air technology of Petro-Probe process. The radiant method is exemplified by Schlumberger’s Raytheon-CF radio frequency (RF) technology. The majority of the abovementioned technologies are at the field-pilot stage, and none have yet reached commercial deployment. Shell (ICP) is one of the most developed technologies4. Shell has conducted numerous in-house experiments and began field pilots as early as 1980s5,6. Both laboratory experiments and field tests have demonstrated that ICP can yield high quality oil that require minimal upgrading7,8.

During ICP, as the temperature increases, solid kerogen and preexisting bitumen will gradually decompose into volatile oil and gas. The yield and composition of the produced hydrocarbons are governed by both the intrinsic properties of the shale and the pyrolysis conditions, including heating time, temperature and pressure etc. Laboratory pyrolysis experiments can effectively simulate true subsurface ICP within a shortened timeframe, providing critical references for target zone selection and temperature–pressure optimization in field applications. Numerous laboratory pyrolysis experiments have been performed in previous researches to (1) establish mathematical models describing the hydrocarbon generation-retention-production behaviors of shales with varying organic matter contents during ICP9, and (2) investigated the temperature–pressure dependent trade-offs between product quality and quantity6,10,11,12,13. These data are needed to develop kinetic models to predict field production processes. Pyrolysis temperature and pressure affect portioning of the generated oil between that retained in the rock and that produced from the rock, which further affects the partitioning between oil and gas14. The heating rate also plays a role by affecting the relative reaction rates and volatilization of various compounds6. Previous studies have proven that the increasing heating rate can lead to decreasing API oil gravity6,11. However, there is a lack of mathematical models to quantitatively predict the evolution of the products at various heating rates throughout the entire ICP production history.

The generation kinetics can be established by integrating pyrolysis curves obtained at different laboratory heating rates, allowing for reliable extrapolation to subsurface conditions. Although hydrocarbon production under ICP condition is a direct consequence of generation, the production itself involves complex physical mechanisms. In this study, a representative low thermal maturity, organic-rich shale sample from the seventh member of Triassic Yanchang Formation in the Ordos basin (abbreviated as Chang 7 shale) that was suitable for ICP was subjected to non-isothermal pyrolysis at multiple heating rates. Based on the experimental data, predictive production models for the main products of concern, including oil, hydrocarbon gas and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) were established. These models aim to provide technical support and references for optimizing in-situ heating development strategies.

Materials and experiments

Samples

The samples were collected from the Ordos Basin, the second-largest petroliferous basin in China. The Chang 7 shale exhibits the following distinctive characteristics: (1) extensive distribution spanning approximately 3 × 104 km2, (2) high thickness, (3) dominance of Type-I and Type-II kerogen, (4) exceptionally high total organic carbon (TOC) content averaging 13.8%, and (5) relatively low to moderate thermal maturity with vitrinite reflectance (R₀) values less than 1.0% 15. Because of its favorable geological characteristics, the Chang 7 shale is one of the most promising and representative shale reservoirs for the application of ICP.

The core samples were obtained from the Well Z75GC1, located in the southern region of the Ordos Basin (Fig. 1). The sampled intervals were in the 3rd sub-member of Chang 7 shale (Chang73), spanning a burial depth range of 1240.6–1258.2 m. The sample preparation procedure was conducted as follows: First, the 17.6-m-long core was bisected longitudinally. From one half of the core, 99 closely spaced samples were systematically collected for detailed analysis. The other half was uniformly crushed and sieved to a particle size range of 50–80 mesh, and the resulting powder was thoroughly homogenized. The homogenized samples were used for pyrolysis experiments.

Location of the sample and the lithology of the selected core interval. The TOC (Total Organic Carbon) contour map was generated using GeoMap4.0 software based on well-logging-derived TOC data (using ΔlogR method) from the target interval. The average TOC values were calculated and then interpolated using GeoMap’s built-in algorithms to construct the final map.

Table 1 and Fig. 2 present the basic geochemical parameters of the 99 samples. The samples are organic-rich (average TOC of 14.17%), low thermal matured (Ro = 0.61%) and characterized by Type-I and Type-II organic matter. Table 1 also provides a comparative analysis of the geochemical characteristics between the homogenized samples and the averaged parameters derived from the 119 discrete samples. The results show that they share similar basic geochemical characteristics, confirming the representativeness of the homogenized samples.

Experiments

Pyrolysis experiments

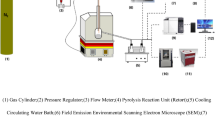

The pyrolysis experiments were performed using a self-designed hydrocarbon generation and expulsion apparatus. The schematic diagram of the apparatus is shown in Fig. 3. The high-pressure autoclave was made by special alloy resistance to corrosive gases including hydrogen sulfide (H2S), carbon dioxide (CO2). After sample loading (about 150 g), the system was pressurized to 4 MPa using nitrogen (N2) from a gas cylinder, with this pressure maintained for 24 h to confirm the tightness of the autoclave and all connected pipelines. During the experiment, a constant lithostatic pressure of 20 MPa was maintained using a hydraulic pressure system. The autoclave was maintained at a constant fluid pressure of 2 MPa. The lithostatic pressure was set at 20 Mpa, referring to the actual formation pressure of the Chang 7 shale16. The fluid pressure was set at 2 MPa as an exploratory configuration to facilitate fluid expulsion. When the internal fluid pressure exceeded this threshold, the solenoid valve automatically opened, initiating hydrocarbon expulsion. Following the pressure release, the system pressure decreased, causing the valve to automatically closed. The liquid products expelled during the experiments were collected by a sealed container immersed in a 5 °C constant-temperature cooling water bath, and the gaseous products were collected by a vacuum gas bag.

Schematic diagram of the pyrolysis apparatus. (1) gas charge cylinder, (2) gas charge valve, (3) electric heater, (4) hydraulic device, (5) autoclave, (6) upper hydrocarbon expulsion pipe, (7) lower hydrocarbon expulsion pipe, (8) sample, (9) thermocouple, (10) temperature controller (11) electromagnetic valve, (12) back pressure valve, (13) back pressure pump, (14) liquid hydrocarbon collector, (15) condensation circulating water bath, (16) gas expulsion pipe, (17) gas collection bag.

The heating rates for pyrolysis experiments were 2 °C /d, 5 °C /d, 10 °C /d and 20 °C /d. Before programmed heating, the samples were heated from room temperature (~ 20 ℃) to 270 ℃ in 72 h. The maximum temperature for the four experiments was 450 ℃. In each experiment, expelled products were collected corresponding to the following temperature intervals: 20–320 °C, 320–350 °C, 350–380 °C, 380–410 °C, 410–440 °C, and 440–450 °C. After collecting the products at each stage, the pipelines were flushed with dichloromethane (DCM) to gather the residual expelled oil adhering to the pipelines.

Products quantification

The expelled oil included both the main portion collected in the sealed collector and the additional amount recovered through DCM rinsing. The oil yield in the collector was determined by the weight change before and after collection. The DCM flushed out oil yield was quantified via gas chromatograph, through peak area comparison between the oil and the internal standard (Tetracosane-D50). The expelled gaseous products were measured by gas chromatograph. Before analysis, the chromatograph was calibrated using a standard gas mixture containing C1 ~ C5 n-alkanes, H2S, CO2, CO, H2, O2 and N2.

Experimental results and modeling

Oil production

Table 2 presents the interval yields of oil productions under different heating rates. The cumulative oil yields were obtained by summing up all the interval yields before certain temperature point. In all four experimental series, peak oil production occurred within the temperature range of 320–410 °C (Fig. 4a). In addition, the main oil production zone at slower heating rate shifts to lower temperature range (Fig. 4b). The cumulative oil production increased with increasing temperature.

Gas production

The interval yields of hydrocarbon gas production under different heating rates are shown in Table 2. The cumulative hydrocarbon gas yields were also obtained by summing up all the interval yields before certain temperature point. The peak hydrocarbon gas production occurred within the temperature range of 320–440 °C (Fig. 5a), slightly wider than the peak oil production range. Consistent with oil production trends, cumulative hydrocarbon gas production increased with temperature. However, in contrast, the main hydrocarbon gas production zone at higher heating rate shifts to lower temperature range (Fig. 5b).

The peak generation rates of non-hydrocarbon gas H2S consistently occurs within the temperature range of 320–440 °C across different heating rates (Table 2 and Fig. 6a). The cumulative production yield H₂S is highly dependent on the heating rate (Fig. 6b). At a slow heating rate of 2 °C/day, almost no H₂S is generated, but as the heating rate increases, the cumulative H₂S production rises sharply (Fig. 6b).

Mathematical modeling

Currently, most existing kinetic models are specifically designed for oil and gas generation, employing Nth-order parallel first-order reactions with rate constants following the Arrhenius equation. A fundamental assumption in constructing generation kinetic models is that the maximum hydrocarbon gas and oil yields converge to approximately the same value at the maximum experimental temperature, independent of the heating rate17,18.

For expulsion/production modeling in this study, the maximum yield of oil production did not vary greatly with heating rate. However, the maximum hydrocarbon gas showed strong heating rate dependency. The maximum yield of hydrocarbon gas of 2 °C/d series experiments is 45% higher than that of 20 °C/d. Notably, the maximum yield of non-hydrocarbon gas H2S exhibited the highest sensitivity to heating rate variations. The maximum yields of H₂S in the 20 °C/d series exceed those in the 2 °C/d series by 221%. For H2S, its generation is not solely attributed to organic matter decomposition; the decomposition and transformation of inorganic minerals pyrite play a more significant role19. Therefore, existing method of generation kinetic models may not be suitable for hydrocarbon gas, particularly for H2S. The presence of H2S poses a challenge for optimizing the pyrolysis scheme of ICP. Specialized facilities are required for product recovery, and additional treatment of the oil and gas—particularly the removal of corrosive H₂S—can significantly increase costs. Therefore, when establishing the kinetic model, non-hydrocarbon gases should also be considered. Considering these factors, this study utilizes an experimental data-driven numerical fitting approach to develop mathematical models predicting cumulative production of various components during ICP of shale.

Mathematical models characterizing cumulative production yield of various components including oil, hydrocarbon gas and H2S were established. They followed the same procedure. A stepwise modeling approach for numerical fitting analysis was adopted. Initially, single-parameter regression analysis was performed with temperature and heating rate as independent variables (single-factor analysis) and cumulative production of different products as dependent variables. Then, based on the IBM SPSS Statistics 26 software platform, multifactorial numerical fitting was conducted by simultaneously coupling both temperature and heating rate parameters to evaluate their synergistic effects on production yields.

Modeling results and discussion

Oil

Figure 7a presents the heating rate-dependent behavior of cumulative oil production yields at fixed temperature. At the same temperature, they demonstrate a nearly linear correlation with heating rate. At six temperature points of 320 °C, 350 °C, 380 °C, 410 °C, 440 °C, and 450 °C, the correlation between cumulative production yield and heating rate always follows Eq. (1):

where Ot is cumulative production yield of oil at certain temperature (t), hr is heating rate, and a1o and b1o are empirical coefficients. The values of a1o and b1o at different temperatures are shown in Table 3. The correlation coefficients (R2) of the six fitting curves range from 0.504 to 0.987.

(a) Heating rate-dependent behavior of cumulative oil production at fixed temperature, the dashed lines are fitted lines. (b) Temperature-dependent behavior of cumulative oil production at fixed heating rate, the dashed lines are fitted lines, and the blue and red solid lines represent prediction curves constrained by both temperature and heating rate.

The influence of heating rate on oil yield during pyrolysis exhibits stage-dependent characteristics across different temperature regimes. Below 380 °C, the cumulative oil production exhibits obvious negative correlation with the heating rate. In contrast, above 380 °C, oil production shows slightly positive correlation with the heating rate (Fig. 7a). This is mainly due to the dependence of apparent activation energy and the competition between liquid-phase oil cracking/coking and oil vaporization affected by heating rate20. In conventional kinetic models, the activation energy is typically treated as a constant. However, many pyrolysis study reveals that the apparent activation energy dynamically shifts with variations in heating rates21,22,23. Under slow heating rates, the system remains at lower temperatures for extended periods, leading to prolonged retention of heavier components in the liquid phase. This facilitates cracking/coking reactions, which necessitate higher apparent activation energies and consequently reduce the effective oil yield.

However, before 380 °C, the calculated EasyRo values for the four heating rates (from fastest to slowest) were 1.2%, 1.3%, 1.4%, and 1.6%, respectively. Therefore, slow heating rates prolonged thermal exposure of kerogen and bitumen, promoting the generation of volatile oil, and the effect of volatile oil cracking and coking reactions may not yet exceed its generation. Chang 7 shale in this study contains lacustrine Type-II kerogen. Previous studies have shown that its highly branched and cross-linked kerogen structure provides sufficient weak bonds that can be broken in parallel during peak hydrocarbon-generating stage (0.6–1.09%Ro), leading to the simultaneous peak generation of liquid oil and bitumen24,25. Above 380 ℃, cracking/coking reactions become increasingly dominant. Under slow heating rate conditions, prolonged liquid-phase oil residence times significantly enhance coking/cracking reactions, thereby facilitating the conversion of oil fractions to gaseous products and solid coke, which ultimately diminishing total oil yields26,27.

Figure 7b shows the temperature-dependent behavior of cumulative oil production yields at fixed heating rate. The cumulative oil production with temperature under different heating rates can be fitted by Eq. (2):

where Ohr is cumulative production yield of oil under certain heating rate (hr), a2o, b2o, c2o and k2o are empirical coefficients. Their values under different heating rates are shown in Table 4. The R2 of the four fitting curves are all greater than 0.997.

By integrating Eq. 1 and Eq. 2, the cumulative oil production curve under dual constraints of heating rate and temperature can be derived, as shown by Eq. (3):

where O is cumulative production yield of oil under the constraints of pyrolysis temperature and heating rate, hr is heating rate, t is temperature, a3o, b3o, c3o, d3o, and k3o are empirical coefficients.

Based on the heating rate and temperature data from Table 2 (as independent variables) and the cumulative oil production (as the dependent variable), the empirical coefficients in Eq. (3) can be derived via numerical simulations using SPSS Statistics 26 software. Equation (3) is finally presented as Eq. (4):

where O is cumulative production yield of oil under the constraints of pyrolysis temperature and heating rate, hr is heating rate, and t is temperature. The correlation between measured oil production and fitted oil production and their mean squared error were presented in supplementary material.

Hydrocarbon gas

Following the methodology for oil production calculation, a mathematical model for hydrocarbon gas was developed. Under the same pyrolysis temperature, the cumulative production yield of hydrocarbon gas as a function of heating rate is given by Eq. (5) (Fig. 8a). At a fixed heating rate, the correlation of cumulative production yield of hydrocarbon gas versus pyrolysis temperature is expressed by Eq. (6) (Fig. 8b). By integrating Eq. (5) and Eq. (6) and the data from Table 2, the cumulative production yield of hydrocarbon gas can ultimately be described by Eq. (7).

where Gt is cumulative production yield of hydrocarbon gas at certain temperature (t), Ghr is cumulative production yield of hydrocarbon gas under certain heating rate (hr), G is cumulative production yield of hydrocarbon gas under the constraints of pyrolysis temperature and heating rate, and a1g, b1g, a2g, b2g, c2g, k2g are empirical coefficients. Their values are presented in Tables 3 and 4. The correlation between measured hydrocarbon gas production and fitted hydrocarbon gas production and their mean squared error were presented in supplementary material.

(a) Heating rate-dependent behavior of cumulative hydrocarbon gas production at fixed temperature, the dashed lines are fitted lines. (b) Temperature-dependent behavior of cumulative hydrocarbon gas production at fixed heating rate, the dashed lines are fitted lines, and the blue and red solid lines represent prediction curves constrained by both temperature and heating rate.

The production yield of hydrocarbon gas exhibits an inverse correlation with heating rate (Fig. 8a). Faster heating rates result in lower gas production when reaching the same pyrolysis temperature. This is mainly due to the longer liquid-phase residence time at slower heating rate. As has mentioned in section "Oil", Chang 7 shale can generate liquid oil during primary decomposition, which serves as precursor material for subsequent hydrocarbon gas formation. The adequate cracking of liquid-phase products can yield a greater number of gaseous components.

Hydrogen sulfide

The detail establishment procedure of mathematical models of H2S follows the same way as that of oil and hydrocarbon gas. Under the same pyrolysis, the cumulative production yield of H2S as a function of heating rate is given by Eq. (8). At a fixed heating rate, the correlation of cumulative production yield of H2S versus pyrolysis temperature is expressed by Eq. (9). By integrating Eq. (8) and Eq. (9) and the data from Table 2, the cumulative production yield of H2S can ultimately be described by Eq. (10).

where St is cumulative production yield of hydrogen sulfide at certain temperature (t), Shr is cumulative production yield of hydrogen sulfide under certain heating rate (hr), S is cumulative production yield of hydrocarbon gas under the constraints of pyrolysis temperature and heating rate, and a1s, b1s, a2s, b2s, c2s, k2s are empirical coefficients. Their values are presented in Tables 3 and 4. The correlation between measured H2S production and fitted H2S production and their mean squared error were presented in supplementary material.

As evident from Eq. (8) and Fig. 9, H₂S production demonstrates a positive correlation with heating rate, a trend distinct from hydrocarbon gas. This is primarily attributed to the formation mechanism of H₂S. In the sample of this study, the sulfur of H₂S is not derived from direct cracking of organic compounds in shale, but rather originates from the decomposition of inorganic pyrite. Previous studies have confirmed that the organic sulfur content in Chang 7 shale is limited, while pyrite is exceptionally abundant19,28. The transformation of pyrite to pyrrhotite and subsequently to troilite (FeS2 → Fe1−xS → FeS) generates active nascent sulfur radicals, which can combine with hydrogen from organic components to form H2S29,30. Pyrite by itself is stable to above 500 °C. However, when it is in contact with organic matter, its decomposition temperature is decreased significantly20. The sulfur generated by pyrite decomposition not only can form H2S, but also can incorporate into the organic matrix of solid residue19,31. The production of H2S depend on both sulfur availability and hydrogen supply. Under the current experimental conditions, the increased H₂S production yield observed at faster heating rates is likely attributed to hydrogen availability. The cracking of heavy oil into light oil or hydrocarbon gases consumes hydrogen. This implies that under fast heating conditions, decreased cracking of crude oil consumes less hydrogen. Consequently, more hydrogen remains to react with elemental sulfur, resulting in reduced H2S generation. As indicated in Table 2, a higher H₂ production rate accompanies rapid heating, suggesting enhanced hydrogen supply promotes H₂S formation. In addition, short residence time resulting from fast heating rate limits sulfur incorporation into solid residue, thereby enhancing its release as volatile sulfur compounds.

(a) Heating rate-dependent behavior of cumulative hydrogen sulfide production at fixed temperature, the dashed lines are fitted lines. (b) Temperature-dependent behavior of cumulative hydrogen sulfide production at fixed heating rate, the dashed lines are fitted lines, and the blue and red solid lines represent prediction curves constrained by both temperature and heating rate.

It needs to clarify that the mathematical models developed in this study were based on experimental data from the specific Chang 7 shale sample. Therefore, while the fundamental trends regarding heating rate effects are likely broadly applicable, the absolute yields predictions may need calibration when applied directly to other shales with different kerogen types and TOC content. Sulfur content and mineralogy is the most critical factor for H₂S prediction. The model here is highly dependent on the abundant pyrite in our sample. For shales with low or no pyrite content, the H₂S generation model would need scaling down or removal. For shales rich in organic sulfur or sulfates, the H₂S generation model presented in this study is not applicable due to fundamentally different reaction pathways. In organic sulfur-rich shales, H₂S is primarily generated through cleavage of C–S bonds in organic matter, a process that occurs predominantly during the early stages of shale maturation32. In sulfate-rich shales, H₂S is produced mainly via thermochemical sulfate reduction (TSR) at high maturation stages, where sulfate minerals are reductively converted into H₂S33. Both mechanisms differ significantly from the pyrite-dominated H₂S formation pathway described in our model. Therefore, new kinetic models suitable for specific sulfur species and reaction pathways would be required to accurately predict H₂S generation.

Application

The comparisons of oil and hydrocarbon gas production between the experimental data and the predicted data based on temperature-heating rate constrains are shown in Fig. 10a, b. The predicted data are shown in supplementary material. The high agreement (R2 > 0.96) between experimental and predicted data confirms that the proposed mathematical model reliably predicts cumulative oil and hydrocarbon gas production for Chang 7 shale under in situ heating conditions at heating rates of 2–20 °C/d and final temperatures of 320–450 °C.

The peak oil generation window for the majority of source rocks typically spans vitrinite reflectance (Ro) values of 0.5–1.3%34. At higher thermal maturity, liquid hydrocarbons undergo significant cracking, with near-complete conversion to gaseous hydrocarbons occurring at approximately 2.3% Ro35. Therefore, when predicting production yields under different heating rates, the maturity should not exceed 2.3% Ro. According to calculations performed with Kinetics 2000 software, thermal maturation to EasyRo = 2.3% by heating rates of 1 °C/d and 0.5 °C/d will be achieved at 406 °C and 397 °C, respectively. The predicted cumulative production yields of oil and hydrocarbon gas under the heating rates of 1 °C/d and 0.5 °C/d heating rates are shown in Figs. 7b and 8b. Both predicted curves fall within the range of experimental data, demonstrating the validity of the established mathematical model. The maximum production yields of oil under 1 °C/d (reaching 406 °C) and 0.5 °C/d (reaching 397 °C) heating rates are 40.67 mg/g rock and 37.74 mg/g rock. The maximum production yields of hydrocarbon gas under 1 °C/d (reaching 406 °C) and 0.5 °C/d (reaching 397 °C) heating rates are 10.61 ml/g rock and 9.43 ml/g rock. With decreasing heating rates, both the maximum oil production and hydrocarbon production increase.

The comparisons of H2S production between the experimental data and the predicted data based on temperature-heating rate constrains are shown in Fig. 10c. The predicted data are shown in supplementary material. The R2 between the experimental data and the predicted data is only 0.76, which is lower than the fitting accuracy for oil and hydrocarbon gases. Notably, three negative values appear at 320 °C and 350 °C under heating rates of 2 °C/d and 5 °C/d. Based on Eq. 10, the predicted production rate curves for 1 °C/d and 0.5 °C/d are shown in Fig. 9. The two curves exhibit significant deviation, with negative values occurring at low temperatures. This indicates that the mathematical model for H2S is only applicable within a limited temperature range of 350–450 °C and a heating rate range of 5–20 °C/d. This discrepancy is attributed to the formation mechanism of H2S. As discussed earlier, under slow heating rates, the interconversion between organic and inorganic sulfur reduces H2S generation, leading to the failure of the production model prediction. It is reasonable to predict that the cumulative production yield of H2S may increase at heating rates exceeding 20 °C/d. However, the maximum achievable cumulative H2S yield remains uncertain and requires further experimental investigation. During ICP, minimizing H2S production is generally desirable. The experimental results demonstrate that slower heating rates effectively reduce H2S production (Fig. 9b). From this perspective, slow heating rate is recommended. However, lower heating rates also lead to a slight decrease in maximum oil and hydrocarbon yields at 2.3% EasyRo, while requiring prolonged heating duration and higher energy consumption, ultimately increasing shale oil/gas production costs. Therefore, process optimization must carefully balance the competing factors: hydrocarbon production, H2S yield, and operational cost.

It is important to note that the mathematical models developed in this study are derived from non-hydrous pyrolysis experiments. In steam-assisted in-situ conversion processes, substantial H2S are also generated from kerogen shales under similar temperature conditions (300–380C)36,37. But the kinetics of H2S generation was not considered. We hypothesize that controlled heating rates could be a key operational parameter to manage H₂S production even in hydrous systems. For instance, a slower heating rate might allow for more complete sulfur incorporation into the solid residue or alter the reaction pathways between pyrite, water, and organic matter, potentially reducing the net yield of volatile and corrosive H₂S. This hypothesis requires future validation through dedicated hydrous pyrolysis experiments.

Conclusions

Pyrolysis experiments of four heating rates were performed on a typical shale that is suitable for ICP. By characterizing the products produced in different temperature intervals, the effects of heating rate and temperature on the production yields of oil, hydrocarbon gas, and H2S were investigated. Then, mathematical prediction models for oil, hydrocarbon gas, and H2S production during ICP constrained by temperature-heating rate were established by adopting stepwise modeling approach. The results contribute to the optimization process of ICP design for shale. The main results are as follows:

-

(1)

The production yields of oil, hydrocarbon gas, and H2S are affected by both heating rate and temperature during pyrolysis. For oil, when pyrolyzed to the same temperature below 380 °C, the cumulative production yield decreases with increasing heating rate. However, above 380 °C, the cumulative yield increases with higher heating rates. For hydrocarbon gases, the cumulative yield consistently decreases with increasing heating rate when pyrolyzed to identical temperatures across the entire pyrolysis temperature range (room temperature to 450 °C). For hydrogen sulfide, its cumulative production yield consistently increases with increasing heating rate when pyrolyzed to identical temperatures across the entire pyrolysis temperature range.

-

(2)

Mathematical prediction models were developed to predict the production behavior of oil and hydrocarbon gas during ICP at the heating rates of 1 °C/d and 0.5 °C/d. The models demonstrate that when reaching the same thermal maturation of EasyRo = 2.3%, both oil and hydrocarbon gas yields are higher at the 1 °C/d heating rate compared to the 0.5 °C/d rate. Due to the formation mechanisms of H₂S, the predictive model is only applicable within heating rates of 5–20 °C/d. At rates below 2 °C/d (the minimum rate tested in this study), its production may become negligible.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Burnham, A. K. Then and now: An EMD perspective on oil shale. AAPG Explorer. 36(5), 69–70 (2015).

Chen, B., Cai, J., Chen, X., Wu, D., Pan, Y. A review on oil shale in-situ mining technologies: Opportunities and challenges. Oil Shale. 2024;41(1).

Kang, Z., Zhao, Y. & Yang, D. Review of oil shale in-situ conversion technology. Appl. Energy 269, 115121 (2020).

Speight, J. G. Shale oil production processes (Gulf Professional Publishing, Houston, 2012).

Fowler, T.D., Vinegar. H.J. Oil shale ICP-Colorado field pilots. In: Conference Oil shale ICP-Colorado Field Pilots. SPE, p. SPE-121164-MS.

Ryan, R.C., Fowler, T.D., Beer, G.L., Nair, V. Shell’s in situ conversion process− from laboratory to field pilots. Oil shale: A solution to the liquid fuel dilemma: ACS Publications; 2010. p. 161–83.

Crawford, P. M., Biglarbigi, K., Dammer, A.R., Knaus, E. Advances in world oil shale production technologies. Conference Advances in World Oil Shale Production Technologies. SPE, 2008 p. SPE-116570-MS.

Shen, C. Reservoir simulation study of an in-situ conversion pilot of Green-River oil shale. In: Conference Reservoir simulation study of an in-situ conversion pilot of Green-River oil shale. SPE, 2009 p. SPE-123142-MS.

Hou, L., Ma, W., Luo, X. & Liu, J. Characteristics and quantitative models for hydrocarbon generation-retention-production of shale under ICP conditions: Example from the Chang 7 member in the Ordos Basin. Fuel 279, 118497 (2020).

Burnham, A. K. & McConaghy, J. R. Semi-open pyrolysis of oil shale from the garden gulch member of the green river formation. Energy Fuels 28(12), 7426–7439 (2014).

Burnham, A. K. & Singleton, M. F. High-pressure pyrolysis of green river oil shale (ACS Publications, Washington, 1983).

Le Doan, T. V. et al. Green river oil shale pyrolysis: Semi-open conditions. Energy Fuels 27(11), 6447–6459 (2013).

Zhang, X., Guo, W., Pan, J., Zhu, C. & Deng, S. In-situ pyrolysis of oil shale in pressured semi-closed system: Insights into products characteristics and pyrolysis mechanism. Energy 286, 129608 (2024).

Burnham, A. K. Kinetic models of vitrinite, kerogen, and bitumen reflectance. Org. Geochem. 131, 50–59 (2019).

Zhao, W., Hu, S. & Hou, L. Connotation and strategic role of in-situ conversion processing of shale oil underground in the onshore China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 45(4), 563–572 (2018).

Yang, X. et al. Stress sensitivity and its influence factors of tight oil reservoir in Chang 7 member, Ordos Basin. China Pet Explor. 22(5), 64 (2017).

Hill, R. J., Zhang, E., Katz, B. J. & Tang, Y. Modeling of gas generation from the Barnett shale, Fort Worth Basin. Texas. AAPG bulletin. 91(4), 501–521 (2007).

Zhang, E., Hill, R. J., Katz, B. J. & Tang, Y. Modeling of gas generation from the Cameo coal zone in the Piceance Basin Colorado. AAPG Bull. 92(8), 1077–1106 (2008).

Ma, W., Hou, L., Luo, X., Liu, J. & Han, W. Thermal transformation of sulfur species and hydrogen sulfide formation in high-pyrite-containing lacustrine type-II shale during semiopen pyrolysis. Energy Fuels 35(9), 7778–7786 (2021).

Burnham AK. Global chemical kinetics of fossil fuels. How to model maturation and pyrolysis Springer International Publishing AG. 2017.

Al-Harahsheh, M. et al. Effect of demineralization and heating rate on the pyrolysis kinetics of Jordanian oil shales. Fuel Process. Technol. 92(9), 1805–1811 (2011).

Burnham, A. K. A simple kinetic model of oil generation, vaporization, coking, and cracking. Energy Fuels 29(11), 7156–7167 (2015).

Burnham, A. K. & Braun, R. L. Global kinetic analysis of complex materials. Energy Fuels 13(1), 1–22 (1999).

Hou, L. et al. Chemical structure changes of lacustrine Type-II kerogen under semi-open pyrolysis as investigated by solid-state 13C NMR and FT-IR spectroscopy. Mar. Pet. Geol. 116, 104348 (2020).

Ma, W. et al. Role of bitumen and NSOs during the decomposition process of a lacustrine Type-II kerogen in semi-open pyrolysis system. Fuel 259, 116211 (2020).

Dieckmann, V., Schenk, H. J. & Horsfield, B. Assessing the overlap of primary and secondary reactions by closed-versus open-system pyrolysis of marine kerogens. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 56(1), 33–46 (2000).

Lewan, M. D. & Ruble, T. E. Comparison of petroleum generation kinetics by isothermal hydrous and nonisothermal open-system pyrolysis. Org. Geochem. 33(12), 1457–1475 (2002).

Zhao, W., Zhu, R., Hu, S., Hou, L. & Wu, S. Accumulation contribution differences between lacustrine organic-rich shales and mudstones and their significance in shale oil evaluation. Pet. Explor. Dev. 47(6), 1160–1171 (2020).

Bakr, M. Y., Yokono, T., Sanada, Y. & Akiyama, M. Role of pyrite during the thermal degradation of kerogen using in situ high-temperature ESR technique. Energy Fuels 5(3), 441–444 (1991).

Ma, X. et al. Influence of pyrite on hydrocarbon generation during pyrolysis of type-III kerogen. Fuel 167, 329–336 (2016).

Kelemen, S. R., Sansone, M., Walters, C. C., Kwiatek, P. J. & Bolin, T. Thermal transformations of organic and inorganic sulfur in Type II kerogen quantified by S-XANES. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 83, 61–78 (2012).

Nelson, B.C., Eglinton, T.I., Seewald, J.S., Vairavamurthy, M.A., Miknis, F.P. Transformations in organic sulfur speciation during maturation of Monterey shale: Constraints from laboratory experiments. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, MA (United States). Dept. of Marine …; 1995.

Machel, H. G. Bacterial and thermochemical sulfate reduction in diagenetic settings: Old and new insights. Sed. Geol. 140(1–2), 143–175 (2001).

Tissot, B. P. & Welte, D. H. X. Petroleum formation and occurrence (Springer Science & Business Media, Berlin, 2013).

Hill, R. J., Tang, Y. & Kaplan, I. R. Insights into oil cracking based on laboratory experiments. Org. Geochem. 34(12), 1651–1672 (2003).

Kapadia, P. R., Wang, J. & Gates, I. D. On in situ hydrogen sulfide evolution and catalytic scavenging in steam-based oil sands recovery processes. Energy 64, 1035–1043 (2014).

Mukhina, E. et al. Sustainable hydrocarbon recovery from immature organic-rich shales: Large-scale thermal experiment and field application. Chem Eng J. 512, 162713 (2025).

Funding

This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No, 42172170).and CNPC key project of Science and Technology (Grant No, 2021DJ52).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hou Lianhua: Writing-original draft, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Revision, Software. Weijiao Ma: Writing-original draft, Revision,Data curation,Conceptualization. Jingkui Mi: Conceptualization, Experiment. Xia Luo: Supervision, Resources. Xingzhi Ma, Fengrong Liao, and Senhu Lin: Resources, Experiment.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hou, L., Ma, W., Mi, J. et al. Multi-heating-rate pyrolysis study for modeling hydrocarbon production from in-situ conversion of Chang 7 shale. Sci Rep 16, 2106 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31784-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31784-7