Abstract

Coastal areas are dynamic, shaped by natural processes and human activities, making accurate prediction of shoreline and land use changes crucial for sustainable management. This study presents a hybrid modeling framework that combines CA–Markov and machine learning to enhance land use/land cover (LULC) and shoreline change projections in Oman’s vulnerable coastal regions. Coastlines were delineated using multi-temporal Landsat images (1997–2006-2015-2024) and the Normalized Difference Water Index, while erosion and accretion rates were quantified using End Point Rate and Linear Regression Rate analyses. Results from 1997 to 2024 show substantial spatial variability, with urban localities such as Rakhyut experiencing significant erosion (-1.81 m/year) and areas like Bawshar showing accretion (1.41 m/year). Coastal LULC changes reveal rapid urban expansion, as seen in Muscat’s built-up area, which increased from 10.31 km² in 1997 to 116.41 km² in 2015. Four models—CA–Markov, CA–Markov + XGBoost, CA–Markov + CART, and CA–Markov + RF—were evaluated for future LULC prediction. The hybrid CA–Markov + RF model achieved the highest predictive performance, increasing overall accuracy from 0.905 (CA–Markov) to 0.935 (CA–Markov + RF) on the test dataset, highlighting the capability of machine learning models. Projections for 2033 indicate continued urban growth, particularly in Salalah and Sohar, alongside reductions in vegetation in arid regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coastal areas have been at the center of human advancement over the last few decades due to their geographical advantage, adaptability, and economic potential, which support activities such as fishing, commerce, tourism, and port facilities1. As of 2005, approximately 23% of the world’s population resided within 100 km of the coast; by 2030, this is projected to increase to 50%2. However, the increasing pressure of population, combined with the natural dynamism of tidal, wave, and sediment transport-designed coast systems, makes such systems extremely sensitive to environmental change3. Urbanization, particularly for developing countries like Oman, has completely altered coastal systems through the process of infrastructure construction, land reclamation, and hard engineering, a tendency to cut off natural sediment flows and allow erosion and habitat degradation to increase4. The Omani low-coastal plains are also highly vulnerable, with urbanization gradually spreading into flood-prone and environmentally sensitive areas5. Also, coastal processes like erosion, sediment accretion, and land-use conflict are of growing significance with the impacts of climate change, thus making sustainable coastal management more complicated. This therefore demands the need to have sustainable planning and viable monitoring in an attempt to balance development with the preservation of the environment.

Given this context, the present study emphasizes the necessity to understand and monitor coastline and land cover change along the coastline of Oman, where rapid development comes with mounting environmental concerns. Remote sensing and GIS-based methods have become the prominent shoreline extraction methodology and spatial-temporal change analysis during the past decades. Aladwani (2022) employed satellite imagery to map stable coastal segments along a 70 km coastline length in Kuwait, measuring shoreline change through the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) and End Point Rate (EPR) and Linear Regression Rate (LRR) models6. Shamsuzzoha and Ahamed (2023) performed a 30-year record of coastal accretion and erosion in Bangladesh through remote sensing and GIS techniques, noting considerable changes over the decades7. Hastuti et al. (2024) in a recent paper employed NDWI coupled with the EPR model to evaluate shoreline change along Bali Province, Indonesia, where coastal erosion acceleration was a spotlight concern7. More recently, Dahy et al. (2025) employed multi-temporal Landsat imagery to track two decades of coastal evolution in the Arabian Gulf, map extensive shoreline retreat and land reclamation associated with accelerated urbanization and anthropogenic activities8. Among all the techniques used for shoreline detection, NDWI has been one of the most widely used and essential techniques due to its simplicity in computation and speed. Du et al. (2016) confirmed that NDWI outperforms traditional indices for mapping inland and coastal water bodies, as long as the appropriate thresholding methods are used9. Rokni et al. (2014) demonstrated that NDWI yielded more stable and accurate shoreline extraction results compared to edge detection and other spectral indices10. Iacobucci et al. (2025) applied NDWI to extract shoreline from multi-sensor satellite time series and highlighted its efficiency in coastal change detection along the central-eastern border of the Tyrrhenian Sea11. Precise shoreline detection not only helps in understanding the natural dynamics of the coast but also provides the indispensable foundation for the assessment of human-induced changes, such as urbanization of the coastal zones.

To quantify coastal urban sprawl, the distance between land and the coast must be accounted for. Once the coastal zone is mapped, satellite images can then be derived to obtain Land Use and Land Cover (LULC) maps using different methods of classification, such as supervised and unsupervised methods, object-based image analysis, and machine learning algorithms. LULC maps are useful in identifying the temporal change of urbanization, particularly in the coastal urbanizing areas. Satellite high-resolution imagery, such as Landsat, Sentinel (Copernicus Programme), and MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer), is used extensively for this analysis so that urban sprawl and its environmental impacts can be measured. The usability of this approach has been established through numerous studies. For example, Zhang (2023) applied Landsat images to study spatiotemporal patterns of urban sprawl along the Xiamen seashore and evaluated changes with time12. Lodato et al. (2023) used Google Earth Engine (GEE) and Random Forest (RF) algorithms on Landsat to monitor 40 years of coastal urbanisation off Rome, demonstrating the power of cloud platforms and machine learning for monitoring coastal urbanisation13. Dahy et al. (2024) used remote sensing techniques to study half a century of urbanization along the Persian Gulf coastline and derived the environmental effects of the intense urbanization within the region14. Manikandababu et al. (2025) analyzed LULC transformations in Mexico’s Centro Region from 2000 to 2020 using multi-temporal Landsat imagery and the Random Forest classifier, demonstrating the effectiveness of remote sensing in monitoring urban expansion and its environmental impacts15.

The significance of the present research lies in the connection of shoreline change with LULC change for a better conceptualization of coastal evolution. Monitoring coastal urbanization is key to using machine learning to understand and predict land use and land cover (LULC) changes. Studying past LULC helps us understand urban growth, while predicting future LULC supports climate resilience and sustainable coastal planning. Predicting the future changes in urban and natural environments allows policymakers and planners to foresee likely environmental and socio-economic impacts16. One of the advanced ways of doing this, the Cellular Automata–Markov (CA–Markov) model has gained extensive interest due to the fact that it is capable of integrating spatial processes and temporal probabilities of change. This hybrid approach improves LULC prediction by both the pattern (via Cellular Automata) and rate (via Markov chains) of LULC change. Ikegwuoha et al. (2021), for example, used the CA–Markov model to simulate LULV in the Lepelle River Basin17. Likewise, Aksoy and Kaptan (2021) applied the CA–Markov model in predicting future LULC changes of the northern Ulus district of Turkey18. More recently, Khodaei et al. (2025) applied the model in projecting future LULC changes of the Kashkan Watershed of Iran with particular emphasis on its suitability in flood risk analysis and watersheds management19.

This study represents the first application of a dynamic hybrid ensemble framework along Oman’s coastline—a region characterized by arid climatic conditions, sparse vegetation, and rapid coastal urbanization—distinct from the humid, vegetated, or deltaic environments explored in previous research. Whereas earlier studies have examined LULC change along coastlines, most have not simultaneously analyzed shoreline dynamics and land use transitions. In this work, we develop a comprehensive coastal modeling framework that jointly investigates shoreline change rates—including the End Point Rate (EPR) and Linear Regression Rate (LRR)—together with LULC dynamics to provide an integrated understanding of coastal evolution. To more accurately capture the spatial extent of historical shoreline change, dynamic buffer zones were generated for past shoreline maps, ensuring precise spatial correspondence between shoreline movement and LULC transformations. The proposed approach extends the traditional CA–Markov model by integrating multiple tree-based algorithms—Random Forest (RF), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and Classification and Regression Trees (CART)—to create an ensemble hybrid framework that improves spatio-temporal prediction accuracy. Although the CA–Markov model has been widely used for LULC projection, its memoryless nature—relying solely on the most recent cell states—limits its ability to capture long-term dependencies, nonlinear spatial transitions, and complex contextual relationships among neighboring cells. Consequently, it may fail to accurately represent dynamic land use processes in heterogeneous or rapidly changing landscapes. To address this limitation, our hybrid framework incorporates tree-based machine learning algorithms capable of utilizing the full historical behavior of each cell. In particular, they allow the framework to capture complex, nonlinear relationships between LULC transitions and their driving factors, thereby enhancing spatial prediction accuracy. These models have shown strong performance in hydrological and environmental studies, including water quality modeling20, flood forecasting21, flood hazard mapping22, and groundwater level estimation23; however, their application within a shoreline-integrated and dynamically buffered LULC modeling framework remains limited, particularly along Oman’s coast. The objectives of this study are therefore:

-

To analyze the EPR of shoreline change in Oman at 10-year intervals: 1997–2006, 2006–2015, and 2015–2024, as well as to calculate the LRR over the entire period from 1997 to 2024.

-

To evaluate and compare the performance of five methods—CA–Markov, CA–Markov + XGBoost, CA–Markov + CART, and CA–Markov + RF —for LULC classification, and to apply the most accurate method for projecting LULC for the year 2033.

Materials and methods

The methodology of the current study is shown in Fig. 1. Satellite images acquired in 1997, 2006, 2015, and 2024 are initially used to demarcate shorelines using the NDWI. Erosion and accretion rates are quantified through EPR and LRR analyses within each 30-meter transect. Second, a buffer area around the coastline is created, and LULC maps are produced via supervised classification. Four models—CA–Markov, CA–Markov + XGBoost, CA–Markov + CART, and CA–Markov + RF—are trained on 70% of the data for training and 30% for testing to predict the 2024 LULC, after which the best-performing model projects the 2034 LULC distribution.

Study area

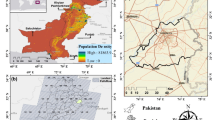

Oman, located in the Arabian Peninsula to the southeast between latitudes 17.01° and 26.17°N and longitudes 54.09° and 59.52°E (Fig. 2), has been geographically demarcated into three general regions: coastal plains, mountains, and desert interiors. Administratively, the country is divided into 11 governorates—Muscat, Al Batinah South, Al Batinah North, Dhofar, Al Dakhiliyah, Al Sharqiyah South, Al Sharqiyah North, Al Buraymi, Al Wusta, Musandam, and Al Dhahirah—each of which comprises many wilayats or states. The coastal areas, particularly those by the Sea of Oman and Arabian Sea, are densely populated and economically vital, and they feature large cities like Muscat, Sohar, and Salalah. Oman’s climate is arid to semi-arid, with hot summers and mild winters, and highly irregular rainfall, while the population is focused on the coastal plains as well as urban centers, and uneven demographic distribution. Industrialization, infrastructure development, and population expansion have greatly transformed the country’s coastal areas during the last few decades. This.growth has indeed expanded the coastal risk of natural hazards such as storm surges, caused by sea-level rise and saltwater intrusion, particularly with climate change pressures. As such, promoting sustainable urban development along the Omani coast emerged as a key development strategy priority in Oman.

The geographic location of Oman, along with its 11 governorates [the map was generated by QGIS 2.18 (https://qgis.org/)].

Among the 61 officially recognized wilayats in Oman, 30 have cities and towns within the coast. The coastal cities, including Muscat—the capital city—and Salalah, hold a large proportion of the nation’s population, where Muscat alone accounts for over one-third of the population. These areas are the most densely populated areas in the country, reflecting intense urbanization and dense migration to the coastal regions. The coastal population is the key to the nation’s economy and infrastructural growth, and hence such cities are essential administrative, economic, and cultural centers. Figure 3 illustrates the geographical distribution and locations of such cities in Oman.

Dataset

We processed Landsat imagery using the GEE platform to obtain high-quality data for analysis. The pre-processed, atmospherically and geometrically corrected Landsat datasets were organized into multi-temporal spectral bands for further analysis. Landsat was chosen for its long-term, consistent, and freely available record with suitable spatial and temporal resolution, enabling reliable monitoring of coastal LULC, erosion, and accretion trends. This technique offered spatial consistency across the time series as GEE internal corrections preserve accurate image matching. Multi-temporal Landsat imagery was employed within this study, as detailed in Table S1 in the Supplementary Material. Satellite images at regular intervals covering the entire coast of Oman were processed. Coastline extraction was carried out as per the procedure outlined by Parthasarathy and Deka (2021)24.

Coastline detection

The shoreline can be defined by choosing a relevant threshold separating water from land. One of the most common measures utilized in this context is the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI). It is a reflection-absorption band-based index described as follows:

In the NDWI, the Green band is chosen as the reflection band, and the near infrared (NIR) is selected as the absorption band25. The range of the NDWI is between − 1 and + 1, with generally negative values indicating land and positive values indicating water bodies. In this study, a threshold value of 0.2 was selected, and values below this value were classified as land, which was determined by trial and error and is consistent with the suggestion of Ihsan et al. (2023)26.

In order to estimate coastal change detection, we applied two statistical methods: EPR and LRR. The LRR method applies all the shoreline data covering 1997–2024 and draws a least-squares regression line to the entire time series of shorelines. The slope of the line is employed to compute the rate of change and provides a long-term means of coastal change. However, LRR does not exactly quantify short-term changes that may occur between individual time intervals due to various factors of influence. In contrast, EPR focuses on short-term trends by quantifying the rate of change between groups of shoreline positions at individual time intervals: 1997–2006, 2006–2015, and 2015–2024. These values are calculated by taking the difference in shoreline position and dividing it by the time difference between the two dates, yielding coastal behavior information for more short-term and time-sensitive coastal processes.

LULC extraction and projection

After extracting the coastline of each year, a 9 km buffer zone has been used for the extraction of Land Use and Land Cover (LULC) using QGIS. The distance of the buffer zone has been deduced through field observations, historical extensions along the coasts, and outcomes of similar studies that have employed such buffer zones for coastal land-use analysis. As an example, Yang et al. (2021) enumerate the importance of determining proper buffer zones as a function of historical information and site conditions to effectively manage coastlines27. Before using maximum-likelihood, the original LULC maps contained eight classes. To improve classification accuracy and reduce spectral overlap, some classes with similar spectral characteristics or extremely small spatial coverage were merged. Specifically, bare rock and land were combined into a single “Bare Land” class, and shrub and sparse vegetation into “Vegetation.” The water, urban, and agriculture classes were maintained separately based on their unique spectral and spatial characteristics. Highly fragmented or small classes (e.g., wetlands) were excluded from the modeling process as their spatial extent was below the mapping threshold (< 1% of the total area). Five broad LULC classes were used in the final model: Urban, Vegetation, Bare Land, Agriculture, and Water. The maximum-likelihood classifier operates under the assumption that each class within each spectral band follows a normal distribution28. This supervised classification technique is based on Bayes’ theorem, which defines the posterior probability P(i∣ω)—that is, the likelihood that a pixel with the feature vector ω belongs to class i.

In this context, \(P\left( {C_{i} \left| x \right.} \right)\) denotes the posterior probability, representing the likelihood that a pixel \(\:x\:\)belongs to class \(\:{C}_{i}\); \(P\left( {x \left| C_{i} \right.} \right)\) is the conditional probability of observing the pixel \(\:x\) given that it belongs to class \(\:{C}_{i}\); \(\:P\:\left({C}_{i}\right)\) refers to the prior probability, indicating how probable class i is before considering the data; \(\:P\left(x\right)\) is the total probability of observing pixel \(\:x\) across all classes; \(\:{C}_{i}\) represents a particular class, and \(\:x\) is the observed pixel or feature vector.

The accuracy of the generated map was evaluated using the Kappa coefficient, a statistical index of agreement between two nominal datasets, calculated as shown in Eq. 3:

Here, \(\:{P}_{o}\) represents the observed agreement, and \(\:{P}_{e}\) denotes the expected agreement by chance.

Once the LULC classification is verified for accuracy, changes in the area per land cover class over different periods can be calculated. To project future LULC patterns, the process starts with generating a 2024 LULC map using the CA–Markov model. This is followed by the development of hybrid models that combine CA–Markov with various tree-based algorithms, including CA–Markov + XGBoost, CA–Markov + CART, and CA–Markov + RF. The design and implementation specifics of these hybrid approaches are elaborated in the next section.

CA–Markov

Cellular Automata–Markov (CA–Markov) model is a widely used approach to simulate and forecast LULC changes by integrating the Markov Chain’s time predictive power and the Cellular Automata (CA)’s spatial modeling power. The Markov chain module forecasts the land cover change probability according to past maps through a transition probability matrix:

Where \(\:{P}_{ij}\) is the probability of transition from class i to class j, and \(\:{n}_{ij}\:\)is the number of pixels that changed from class i to class j. The projected land cover distribution at a future time t + n is calculated as:

Where \(\:{S}_{t}\) is the land cover state vector at time t29. In this study, the CA–Markov simulation was implemented in Python, integrating both Markov chain and Cellular Automata modules. All LULC maps were reprojected to a spatial resolution of 30 m, consistent with the Landsat data used for classification. The CA–Markov model was executed in Python using a Markov chain and the Cellular Automata module. All LULC maps were resampled at a spatial resolution of 30 m to be the same as the original Landsat data. Suitability maps that controlled CA transitions were produced from the most significant environmental and anthropogenic driving parameters, which included distance to coast, elevation, slope, NDVI, and proximity to roads and built-up zones. These variables were normalized to a consistent scale and summed to represent the spatial fit of every potential land-cover transition. A 5 × 5 contiguity filter was applied to preserve spatial dependence and diffusion impacts, lending realism to the simulated LULC processes.

Hybrid models

In order to increase the spatiotemporal precision of LULC maps for the future, a hybrid modeling framework with XGBoost, CART, and Random Forest (RF) was employed. Following this framework, the CA–Markov model was first applied to simulate the 2024 LULC map between the 2006–2015 periods based on the transition probabilities. The derived CA–Markov projection, along with the actual LULC maps of 2006 and 2015, was then used as input to the hybrid machine learning models. To remove spatial autocorrelation and prevent data leakage during model training, the LULC data were split into a training (70%) and testing (30%) set via the application of spatially stratified sampling, in a way that close-by pixels ended up in the same subset and not scattered around at random. This technique allows the models to train on both the observed past dynamics and the initial CA–Markov estimation with the spatial independence of training and test data, therefore improving spatial and temporal patterns. The CA–Markov temporal transition model and sophisticated machine learning algorithms were subsequently employed to train XGBoost, CART, and Random Forest with these data to get the final predicted map of LULC in 2024. The hybrid approach utilizes the strength of the CA–Markov temporal transition model and sophisticated machine learning algorithms to generate stable and spatially consistent predictions of LULC. Additional algorithmic and mathematical details of XGBoost, CART, and RF are shown in the Supplementary Material.

Hyperparameter tuning and accuracy assessment

The dataset was split into training and testing sets using a 70:30 ratio. GridSearchCV was applied in hyperparameter tuning, a process also employed in earlier research studies30,31,32. Its popularity reflects its effectiveness in searching exhaustively within a predefined range of hyperparameter values, which is useful when the complex interactions among the hyperparameters are not clearly understood32. For XGBoost, the tuned parameters included tree depth, number of trees, learning rate, minimum loss reduction, and fractions of features and samples used per tree. For CART, the focus was on tree depth, number of features considered at each split, and minimum samples for splits and leaves. For Random Forest, the optimized parameters were tree depth, number of trees, feature selection per split, and minimum samples for splitting and forming leaves.

Accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score were used to evaluate the comparison among models. They are derived from the number of True Positives (TP), True Negatives (TN), False Positives (FP), and False Negatives (FN) and provide a general indication of the performance of the classifier. Accuracy is a count of the correctly predicted positive and negative cases concerning the total number of predictions, as presented in Eq. (10).

Accuracy, as provided by Eq. 11, is the proportion of true positives (TP) to the total number of cases that the model estimated positively and is a major measure of global classification accuracy.

Recall represents the proportion of correctly identified positive cases out of the total actual positive instances (TP + FN), as shown in Eq. 12. It highlights how effectively the model can detect positive cases.

The F1-Score, which integrates both precision and recall, provides a comprehensive measure of the model’s overall effectiveness, as depicted in Eq. 13.

Results

Coastal change detection

EPR

Between 1997 and 2006, EPR at the wilayat level fluctuated dramatically (Fig. 4a). For example, Rakhyut (2.9 m/year) and Jaalan Bani Bu Ali (2.08 m/year) showed major accretion along the coast, likely due to sedimentation. However, the cities of Barka (−0.95 m/year) and Mutrah (−0.95 m/year) showed widespread coastal erosion, implying that there is evidence of shoreline retreat to have a result of coastal factors such as erosion or sea-level rise. Salalah exhibited accretion at 1.83 m/year and Sur at 1.88 m/year, suggesting an equilibrium of natural and human-induced factors along their coastlines.

From 1997 to 2006, at the Governorate level, Dhofar and Ash Sharqiyah South had the strongest positive mean EPRs (1.57 m/year and 1.89 m/year). Both of these areas are experiencing net coastal progradation, most likely due to either better sedimentary conditions on the coast or due to the redirection of erosive energy. Muscat has negative EPRs of −0.31/m-year, showing that widespread coastal erosion is occurring, with Muscat being impacted significantly by the loss of the coastline. Al Batinah South and Musandam also produced negative EPRs, indicating erosion of their governorate coastlines that can presumably be explained by natural and human-induced changes. The variable EPRs of the governorates indicate the variability of the coastal processes that include human-induced modifications like coastal development, wave energy, and sediment transport.

Between 1997 and 2006, various ports opened or expanded significantly, resulting in an appreciable increase in maritime traffic. Salalah Port in the Dhofar Governorate, for example, has expanded significantly, with an EPR of over 50 m per annum. Smaller-scale ports around the city of Sur in the Ash-Sharqiyah Governorate range from 10 to 30 m per year. Whereas the Liwa Fishery Port within the Governorate of Al Batinah North, which is smaller in size, has an EPR of around 3 m per year. Between 2006 and 2015, at the wilayat level, the 2006 to 2015 shoreline change exhibits a composite trend of erosion and progradation in coastal wilayats of Oman (Fig. 4b).

Severe erosion was encountered in urban localities like Rakhyut (−2.14 m/year) and Salalah (−1.53 m/year), indicating active recession of the shore due to high wave activity, weak sediment supply, or coastal pressure for development. Similarly, the cities of Mutrah and Sohar also showed clear indications of erosion. Nevertheless, willayats like Barka (3.21 m/year), Bawshar (2.36 m/year), and Daba (1.56 m/year) indicated notable progradation, suggesting natural sedimentation. The general trend indicates that even though there is widespread erosion, localized extension of the coast has taken place in some cities. At the governorate level, from 2006 to 2015, Dhofar (−0.9 m/year) and Ash Sharqiyah South (−0.4 m/year) lost the most to erosion during this period, with all but one of their coastal cities showing negative values of EPR.

Al Wusta appeared to show net accretion of the shoreline surface (0.08 m/year), although to a lesser extent. The Muscat governorate, which likely includes erosional sites like Mutrah, observed the mean EPR being comparatively low at 0.54 m/year, despite the presence of progradation on shorelines like Bawshar and As Seeb. Al Batinah South measured the maximum net progradation of the shoreline at 1.95 m/year, and Musandam measured net progradation of the shoreline at 0.38 m/year, which indicates more stable or accreting coastal shorelines. The models presented highlight the geographic variability of coastal processes and the impacts of both natural coastal processes and anthropogenic modifications along the shoreline.

Between 2006 and 2015, large coastal developments were witnessed in most parts of Oman. In the Dhofar Governorate, the expansion of Salalah Port extended more than 5 km offshore, resulting in an erosion or accretion trend with a calculated EPR of 500 m per year. Two breakwaters were also constructed along the Arabian Sea in Taqah, with an average EPR of 60 m per year. Breakwaters are man-made structures particularly designed to protect coastlines, harbors, and ports by spreading the energy of waves traveling to these areas. In Oman, these structures have been in charge of guarding maritime facilities as well as contributing to coastal communities. In As Seeb, there existed a prominent breakwater, which brought shoreline changes at a rate of approximately 80 m per year. Off Ad Duqm’s coast, a small port and two breakwaters were created, contributing to an EPR of more than 360 m per year. Breakwaters also appeared in Al Musanaah and As Suwayq with EPRs of 45 and 50 m per year, respectively.

During 2015 to 2024, Oman coastal wilayats’ EPR analysis shows an irregular trend of changes with both accretion and erosion patterns (Fig. 4c). All the recorded large-scale erosions in Dalkut (−1.88 m/year), Shinas (−1.63), Mahawt (−1.95), and Sohar (−1.52) are those that are sensitive to coastal withdrawal due to suspected vulnerability to high-energy waves, sediment loss, or insufficient coastal facilities. However, the majority of wilayats exhibited progradation, of which Jaalan Bani Bu Ali (0.99), Bawshar (1.95), and Khasab (1.21) are the fastest accreting shorelines, reflecting sedimentation or effective coastal protection. Cities like Masirah (−0.94) and Salalah (−042) exhibit mixed behavior, showing moderate erosion. The data overall suggests that localized factors—like geomorphology, human intervention, and sediment dynamics—firmly influence coastal behavior in different cities.

From 2015 to 2024, Muscat (0.91 m/year), Ash Sharqiyah South (0.05 m/year), and Musandam (0.36 m/year) experienced the highest net progradation at the governorate scale, which was likely due to a combination of natural coastal geometry and urban coastal policy controlling the shoreline. Al Wusta also had a small positive trend (0.1), despite localized erosion near Mahawt. Al Batinah North (−0.04) had a mixed performance; however, it continued to generally trend toward erosion. On a more negative note, Dhofar had a small net erosion (−0.45), with coastal cities Dalkut and Mirbat exhibiting the negative trend. Regional trends from this dataset highlight how governance, coastal development, and natural coastal processes shape coastal stabilization in Oman.

Throughout 2015–2024, there had already been extensive development of coastal infrastructure, with several ports and breakwaters fully constructed or in the process of completion. However, other types of new coastal engineering structures were also constructed within this time frame, contributing to noted changes in shoreline processes. For instance, a major breakwater that appeared in Liwa was associated with a broad shoreline progradation having an EPR of approximately 60 m/year. Similarly, the formation of a small port in Shinas was associated with an EPR of approximately 20 m/year, indicating a moderate shoreline trend. Furthermore, a different new breakwater appearing in the same region indicated a rate of change of approximately 35 m/year.

LRR

LRR from 1997 to 2024 presents a generalization of the long-term shoreline change tendencies along the coastal governorates and wilayats of Oman (Fig. 5). At the Wilayat scale, Dalkut (−1.67 m/year), Rakhyut (−1.81 m/year), and Salalah (−1.12 m/year) exhibited negative values of LRR, meaning that the wilayat continued to lose area year by year, with Rakhyut showing the maximum loss. Other Dhofar Wilayats, such as Sadh (−0.92 m/year) and Mirbat (−0.61 m/year), also showed erosion but at a slower rate. Bawshar (1.41 m/year) in Al Wusta showed a very high positive trend, with the city gaining area throughout the time frame. Meanwhile, Mahawt (−0.25 m/year) had minimal erosion, while Ad Duqm (0.08 m/year) was marginally stable. Wilayats, including Bawshar (1.45 m/year) and Dabl Al Bayah (0.96 m/year), experienced accretion, reflecting sedimentation or coastal maintenance works promoting shoreline advancement. Wilayats such as Mutrah (0.82 m/year) and As Seeb (0.51 m/year) showed positive values. Further, wilayats such as Barka (0.53 m/year) accreted, and Al Musanaah (0.27 m/year) was nearly stable. Cities such as Al Khaburah (0.18 m/year) and Saham (0.91 m/year) of Al Batinah North showed moderate accretion, and Shinas (−0.76 m/year) showed erosion.

At the governorate level, Muscat (0.65 m/year) had the highest positive shoreline change rate with wide accretion across the area, headed by Wilayat Bawshar. Musandam (0.4 m/year) also had overall shoreline augmentation, the largest being that of Dabl Al Bayah (1.87 m/year). Al Batinah South (0.4 m/year) experienced mixed trends but overall net progradation, and Al Batinah North (0.08 m/year) had a lower accretion rate of the coast. Dhofar (−1.01 m/year) experienced complete erosion, as did the majority of the negative trends of cities there. Al Wusta (0.02 m/year) experienced an overall stable to slightly accreting coast. These trends reflect varied coastal processes in Oman due to natural, man-made, and regional disparities in shore management.

LULC change analysis

After applying a 9 km buffer to the obtained shoreline, the 1997 and 2006 LULC data—with Kappa coefficients of 0.801 and 0.825, respectively—were generated (Figures S1 and S2 in the Supplementary Material). The study of urban expansion in Omani cities between 1997 and 2006 reveals significant transformations (Fig. 6a), particularly in built-up areas, driven by ongoing urbanization. In 1997, Muscat’s built-up area was 10.31 km² and was 23.43 km² in 2006, showing a rise of 13.12 km². Similarly, in Sur, the built-up area went up from 1.31 km² in 1997 to 5.71 km² in 2006, showing an increase of 4.4 km². Similar built-up growth is evident in the other wilayats of Sohar and Salalah, where urbanization has taken hold of these regions. The increase in urban land, particularly in the coastal wilayats, is proportional to the reduction in bareland and vegetation cover in the majority of the areas. Bareland, which was a major portion of the area in 1997, primarily in Muscat (48.67 km²), had drastically reduced by 2006 to 0.79 km², losing 47.88 km². This reduction in bareland is also evident in other municipalities, like Dalkut, where bareland fell from 88.56 km² to 48.67 km², a reduction of 39.89 km².

The decrease in bare land corresponds with increases in built-up and vegetated areas. An example of this is in Muscat, where it was significant as the previously listed bareland areas were developed. Built-up space, although more susceptible to decrease than vegetation space, had different tendencies in cities. In wilayats like Mirbat and Masirah, vegetation decreased by an insignificant percentage. Mirbat decreased from 847.0 km² to 718.8 km², decreasing by 128.2 km², and Masirah lost its vegetation from 1459.1 km² to 1380.0 km², decreasing by 79.1 km². At the same time, other areas like Sohar had more vegetation cover, from 1169.7 km² in 1997 to 1129.6 km² in 2006, pointing to a direction of natural land cover conservation or even expansion. Urbanization is connected to vegetation since most cases of bareland are converted to urban or agricultural use, leaving less space for natural vegetation cover. This urbanization trend with fewer bareland and plant cover puts more and more dense populations of land assets in the forefront as the city populations continue to swell.

The produced 2015 LULC map (Figure S3 of the Supplementary Material) resulted in a Kappa coefficient of 0.844. Between 2006 and 2015, built-up expansion persisted in almost all the cities (Fig. 6b), highlighting the persistent trend of urbanization in Oman. Muscat exhibited a staggering expansion of built-up area from 70.13 km² in 2006 to 116.41 km² in 2015 — an increase of 46.28 km², for instance. In the same way, As Seeb expanded from 121.59 km² to 213.66 km² (an increase of 92.07 km²), and Barka expanded from 250.22 km² to 257.56 km². Sur experienced one of the largest changes in the data, expanding from 43.99 km² to 155.07 km²—an increase of 111.08 km². The effect of urbanization was observed on bareland in Qurayyat—trending down from 563.69 km² to 450.03 km² (113.66 km² decline). Even in Muscat, bareland decreased from 172.13 km² to 101.05 km² (71.08 km² decline). The urban footprint is also encroaching on vegetated lands, but locality differences are heterogeneous.

Changes in vegetation demonstrate a more complex relationship. While some places had a positive increase in vegetation (e.g., Sohar from 30.59 km² to 49.62 km²), a greater number of places had a sudden decline in vegetation caused by urban development. Taqah’s vegetation decreased from 25.43 km² to as low as 8.10 km² (a loss of 17.33 km²), and Sadh’s vegetation decreased from 30.81 km² to 2.48 km² (a loss of 28.33 km²). This means there are large gains in the built-up category as vegetated land is being changed to built-up (urban). Even though bareland is decreasing in most places (e.g., As Seeb decreased by 103.48 km²), not much changed in places like Shalim and Al Jazer, indicating local demand for development. The trend illustrates that urban spread in Oman is expanding and encroaching on vegetated and wasteland, altering ecological kinship and creating long-term sustainability problems for vegetated ground cover conservation and development planning.

The Kappa coefficient for the LULC map created for 2024 (Figures S4 in the Supplementary Material) was 0.852. Figure 6c indicates there was a dynamic spatial change in land use/land cover between 2015 and 2024 out of a total of 31 cities across Oman. The imagery clearly shows a dramatic increase in built-up areas across several cities, most notably in Masirah, Taqah, and Sadh, indicating accelerated urban development. For example, the built-up area of Sadh increased from 92.27 km² to 148.74 km², and for Masirah increased from 51.10 km² in 2015 to 203.20 km² in 2024. At the same time, bareland— which once was the dominant land cover—had slightly decreased in most areas like Dalkut and Al Jazer, but is still the dominant land cover in the urbanized desert cities of Shalim and Ad Duqm.

Meanwhile, water bodies and vegetation have shown mixed patterns. Water cover has grown remarkably in coastal cities such as Masirah (from 6.13 to 17.26 km²) and Sur (from 0.06 to 3.20 km²), perhaps due to improved satellite observation or genuine increases attributed to climatic variations or urban landscaping. Vegetation has increased in urban cities such as Sohar and Salalah, pointing to green initiatives or spontaneous recovery. However, in the majority of inner cities like Shalim and Ad Duqm, coverage has continued to be scarce or reduced, pointing to the continuation of arid conditions. These LULC trends show speeding-up urbanization, low ecological change, and possibly new water management approaches across the Omani landscape.

Model comparison

The CA–Markov model used data from LULC for the years 2005 and 2014 to simulate the 2024 map, while the machine learning models made use of all historic LULC maps. Machine learning models were also grid-search optimized, and results are reported in Table S2 in the Supplementary Material. The performance results for the evaluation criteria are presented in Table 1. The results confirm that all models performed well, with the same accuracy and F1-scores both in training and test stages, indicating that they have good predictive power. The basic CA–Markov model also showed good baseline performance (accuracy: 0.918 train, 0.905 test; F1-score: 0.921 train, 0.905 test). The addition of machine learning techniques improved performance, with CA–Markov + XGBoost showing slight improvements in precision, recall, and F1-score, though CA–Markov + CART resulted in further gains, particularly in accuracy (0.935 train, 0.925 test) and F1-score (0.937 train, 0.924 test). CA–Markov + RF obtained optimal results with maximal accuracy (0.956 train, 0.935 test) and F1-scores (0.951 train, 0.942 test), reflecting greater generalization, stability, and predictive performance overall. This trend implies that the combination of CA–Markov with ensemble-based approaches, particularly Random Forest, greatly improves model credibility.

The Fig. 7 confusion matrices reveal that all hybrid models outperformed the baseline CA–Markov model in terms of classification. The confusion matrices were generated by assigning 1,000 validation points at random to the simulated maps, with 30% of them assigned a positive class proportion at random in order to quantify how well each model approximated observed land cover change. The CA–Markov model performed relatively well both in the training (675 TP, 278 TN) and test (672 TP, 272 TN) periods, though it did show marginally more misclassification. The use of machine learning algorithms made a significant difference: the CA–Markov + XGBoost model reduced both false negatives and false positives and had a greater generalization capacity. The CA-Markov + CART model provided greater prediction accuracy with less misclassification and an excellent balance between sensitivity and specificity. The best performances among all models were delivered by the CA–Markov + RF model. This model produced the lowest number of errors (17 and 21 false positives for training and testing, respectively) and the highest true positives (683 and 679). This indicates that this model has greater stability and is less likely to overfit. In general, the combination of CA–Markov and machine learning significantly improved classification accuracy and homogeneity for both training and test sets.

Future projection

The LULC for the year 2033 was projected using the CA–Markov + RF model (Fig. 8). However, it is important to note that projecting the shoreline for 2033 was not feasible. This is because, in areas where shoreline advancement is expected beyond the 2024 boundary, there is no historical data available to accurately predict the type of LULC that may develop. In other words, the accelerated expansion from the shoreline cannot be classified due to the lack of reference data. Therefore, for the purpose of this projection, we assumed that the 2033 shoreline remains the same as in 2024. A 9 km buffer was applied from this assumed shoreline, and the LULC for 2033 was projected within this defined area. The LULC analysis between 2023 and 2033 across 31 cities in Oman reveals several notable transitions (Fig. 9).

Urban areas are expected to increase, particularly for wilayats like Salalah, Ad Duqm, and Sohar, reflecting continuing urbanization and infrastructure development. The urban area for Salalah, for example, increases from 89.39 to 96.15 km2. Other wilayats, such as Qurayyat and Muscat, decrease slightly, indicating there was either densification or a change in land reclassification. Most coastal and inland urban areas still have a significant amount of Bareland, especially Shalim, Al Jazer, and Ad Duqm, with a net slight increase expected by 2033. The persistence and increase in bareland may indicate aridification, deforestation, or possibly prohibitions of land reclamation. Seeb and Bawshar are exceptions with a decrease in bareland, which may indicate increased vegetation or possible urbanization.

Vegetation and water cover show similar trends, as most of the cities in the United Arab Emirates have lost considerable amounts of vegetation cover, for instance, complete loss in all of Dalkut and Mirbat. This is generally characterized by larger scales of land degradation. Meanwhile, some cities, including Sohar and Saham, show minimal recovery of vegetation cover; however, they are likely the result of successfully initiated afforestation and improved environmental conditions. The water class, though small in total area covered, is also showing declining coverage except in some locales (i.e., Al Jazer and Masirah), likely due to either natural hydrological drying trends and/or land cover class conversion. Overall, these LULC trends lead to calls for adaptive land management practice in Oman, notably in ecologically sensitive or rapidly developing areas.

Projected LULC for year 2033 [the map was generated by QGIS 2.18 (https://qgis.org/)].

Discussion

In the present study, shorelines were delineated from satellite imagery using the NDWI, and erosion and accretion rates were calculated by utilizing the EPR and LRR methods. These rates reflect the underlying coastal processes, including sediment transport, wave action, and tidal dynamics, which control the variability in shoreline change across regions33. Next, a 9 km buffer along the shoreline was established, and LULC maps were generated. Four models—CA–Markov, CA–Markov + XGBoost, CA–Markov + CART, and CA–Markov + RF—were trained to predict LULC for 2024. The best-performing model was then used to predict LULC change for 2034.

Our findings showed a high range of EPR amongst coastal Wilayats in Oman, with Rakhyut at + 4.2 m/yr, and Bawshar at + 3.8 m/yr, and erosion as the dominant process is found at Duqm at −2.7 m/yr. Variations observed are in keeping with natural coastal processes, such as differential sedimentation and wave energy, as well as anthropogenic influence on sediment transport. Port development and breakwaters, for instance, locally modified rates of accretion or erosion as described in Oman’s coastal research34. This finding aligns with Teillet et al. (2025), who reported shoreline change rates ranging from − 3.0 to + 4.5 m/yr, suggesting that our results fall within the regional range identified by previous studies35. As highlighted, this study confirms a quantitative relationship between large-scale infrastructural development, sediment availability, and natural coastal processes, specifically how increased port activity influences coastal dynamics.

Land Use/Land Cover changes, especially urban LULC changes, have exhibited significant shifts over recent decades, largely due to urbanization. During 1997–2006, the change in urban LULC across Omani municipalities shows Muscat’s urban land cover increased by 13.2 km2, Salalah by 4.7 km2, and Sohar by 3.1 km2. This aligns with Al-Awadhi et al. (2017) projection of large-scale systematic urbanization of Muscat over similar time periods, of agricultural and arid land transitioned to residential, commercial, and industrial land36. Overall, it is indicative of the rapid urbanization trends and subsequent changes in coastal and interior areas in Omani cities. The loss of vegetation and bareland is indicative of increased land-sourced pressure and the impetus for effective land management measures. These relative measures show that trends of urbanization in Oman coastal cities are parallel with regional and globally-based urbanization trends. For example, the population in Al Buraimi Governorate has grown twofold since 1993, marking it as unsustainable urban development with associated land use changes37. This is a phenomenon that is consistent with worldwide urban sprawl, which has resulted in the spread of natural areas outward on urban land, leading to the loss of bareland and vegetation38. Urbanization has been ongoing in Oman, and, as bareland and vegetation continue to decline, the perceived land pressure and Earth’s need for sustainability in terms of land resource management are also increasing. These results support the assertion that planning must be carried out in the urbanization process, especially in coastal areas, to avoid further harm to the environment, as suggested by multiple studies on urban growth and environmental decline39.

The merging of machine learning with standard CA methodologies has been revolutionary in LULC prediction. The CA–Markov model relies heavily on historical LULC data for its prediction; the CA–Markov + RF model incorporates machine learning to identify complex spatial and temporal patterns, a feature that increases predictive power and stability of the model. The hybrid approach leverages Random Forest’s ability to conduct non-linear handling as well as an understanding of spatial relationships, which are critical to accurately predicting LULC transition. The hybrid RF–CA model outperformed other combinations, such as CA–Markov + CART and CA–XGBoost, achieving higher accuracy and precision. This demonstrates the potential of hybrid models to overcome the limitations of traditional approaches in predicting land use and land cover changes. LULC projections for Oman in 2034 through a CA–Markov + RF outlook highlighted overarching trends of urbanization, vegetation cover change trends, and bareland dynamics trends. The growth of built-up area in Salalah (+ 5.3 km²) and Sohar (+ 3.8 km²) indicates that urbanization is continuing. Resilience of bareland in Shalim and Al Jazer shows locations where natural sediment trapping and coastal stability are maintaining good viability. Vegetation cover decreases in the range of 2–4 km² in Dalkut and Mirbat, representing cumulative effects of land degradation and emerging climatic patterns. These quantitative trends lead to policy reforms towards adaptive land management, especially considering urbanization impacts and the environmental sensitivity of the coastline of Oman.

The quantitative results of this work are a solid foundation for evidence-based urban planning and land management in Oman, indicating hotspots of high vulnerability and areas where interventions may be most effectively deployed to compensate for environmental impacts. Key recommendations for sustainable urban and coastal management based on observed shoreline dynamics, urban growth trends, and LULC scenarios include:

-

Targeted intervention in high-growth coastal cities to manage erosion and sedimentation.

-

Utilizing green infrastructure with protected area classification to meet the demands of city development while protecting ecosystem services.

-

Utilizing predictive LULC models to assist with influencing proactive policy and planning decisions at the local scale.

Shoreline change detection and predictions of LULC both involve uncertainties from numerous sources of uncertainty. First, the uncertainties involve the remote sensing data themselves. For instance, remote sensing data may include uncertainty from the sensor and pixel resolution, atmospheric interference, and image classification errors that would affect the accuracy of shoreline delineation and land use/land cover classification. Second, the prediction models themselves are a source of uncertainty regardless of how complex the spatial and temporal patterns are accounted for. For example, although CA–Markov and hybrid machine learning models can represent complex spatial and temporal patterns, assumptions made regarding the transition probabilities, neighborhood effects, and parameters within the prediction model can affect predictions. Third, variation inherent in coastal processes, such as episodic storms, tidal range, and sediment transport, means that erosion and accretion in these processes may be unpredictable and also introduce uncertainty. And fourth, anthropogenic processes like urbanization or industrial port expansions and land reclamation are always changing, and may not be fully recorded in archives and/or fully documented over time.

One limitation of this study is the application of satellite imagery and remote sensing techniques to detect shoreline change. While these methods are ideal for large temporal and spatial assessments, they may not be sensitive enough to capture fine-scale or short-term changes in shorelines. The EPR and LRR metrics employed are resolution-dependent, tidal-cycle dependent, and seasonally dependent, thus potentially causing inconsistencies in shoreline definition through time. In addition, the absence of ground-truth verification or in situ measurements restricts the ability to calibrate or validate the observed shoreline change. Furthermore, the extraction process of LULC maps from satellite images introduces uncertainties, particularly in shadowed areas where misclassification may occur.

Conclusion

This study combined remote sensing, statistical shoreline change analysis, and detailed land use modeling to investigate land use and land cover (LULC) change in Oman. The NDWI-based shoreline extraction and EPR/LRR approach proved useful for mapping erosion and accretion trends along the Oman coast. In terms of modeling procedures, the hybrid CA–Markov + RF model demonstrated the best performance for forecasting LULC change under complex, spatially dynamic conditions compared to the other models tested. The results highlight the importance of natural and anthropogenic processes in impacting shoreline and urban dynamics while arguing for the need for sustainable coastal and land management approaches to manage the threats presented by urbanization and environmental degradation. The research provides important data that could support coastal management activities in other arid and semi-arid areas facing similar environmental pressures and challenges. Additionally, the new methods and mixed-methods modeling approach can advance LULC prediction and planning for sustainable development goals around the world.

Future research should attempt to combine high-resolution remote sensing data and ground observations to improve the accuracy of shoreline mapping and to validate remote sensing products. Additionally, integrating socio-economic, climatic, and hydrodynamic factors into LULC and shoreline modeling, along with appropriate sensitivity analyses, can greatly improve our understanding of land cover and coastal change drivers. Each source of uncertainty should be quantified using methods such as sensitivity analysis, cross-validation, or ensemble modeling to make future LULC and shoreline change predictions more robust and reliable.

Data availability

All codes and data generated during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bahrami, N. & Siadatmousavi, S. M. Prediction of coastline evolution using remote sensing and a deep learning approach; case study of the Northwest of the Persian Gulf. Mar. Geol. 480, 107472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2024.107472 (2025).

Reimann, L., Vafeidis, A. T. & Honsel, L. E. Population development as a driver of coastal risk: current trends and future pathways. Camb. Prisms: Coastal. Futures. 1 (e14), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/cft.2023.3 (2023).

Armenio, E., De Serio, F., Mossa, M. & Petrillo, A. F. Coastline evolution based on statistical analysis and modeling. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 19, 1937–1953 (2019).

Ghaderi, D. & Rahbani, M. Shoreline change analysis along the Coast of Bandar Abbas city, Iran, using remote sensing images. Int. J. Coast Offshore Eng. 4, 51–64 (2020).

Islam, M. A., Mitra, D., Dewan, A. & Akhter, S. H. Coastal multi-hazard vulnerability assessment along the Ganges deltaic Coast of Bangladesh—A Geospatial approach. Ocean. Coastal. Manage. 127, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2016.03.012 (2016).

Aladwani, N. S. Shoreline change rate dynamics analysis and prediction of future positions using satellite imagery for the Southern Coast of kuwait: A case study. Oceanologia 64 (3), 417–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceano.2022.02.002 (2022).

Shamsuzzoha, M. & Ahamed, T. Shoreline change assessment in the coastal region of Bangladesh delta using tasseled cap transformation from satellite remote sensing dataset. Remote Sens. 15, 295 (2023).

Dahy, B., Sousa, R., Sultan, M. & Burt, J. A. Two Decades of Coastal Development across the Arabian Gulf: Insights from Remote Sensing and Machine Learning. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. https://doi.org/10.5194/isprs-archives-XLVIII-G-2025-331-2025 (2025).

Du, Y. et al. Water bodies’ mapping from Sentinel-2 imagery with modified normalized difference water index at 10-m Spatial resolution produced by sharpening the SWIR band. Remote Sens. 8 (4), 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs8040354 (2016).

Rokni, K., Ahmad, A., Selamat, A. & Hazini, S. Water feature extraction and change detection using multitemporal Landsat imagery. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 17 (2), 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrs.2014.09.003 (2014).

Iacobucci, G., Piacentini, D. & Troiani, F. Tracking coastal changes in the central-eastern margin of tyrrhenian sea through integrated NDWI-derived shorelines from multi-sensor satellite time series. Remote Sens. Applications: Soc. Environ. 39, 101636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsase.2025.101636 (2025).

Zhang, T. Using satellite imagery to determine Spatiotemporal patterns of built-up land use in relation to the coastline: an example from Xiamen, China. J. Coastal Res. 39 (1), 103–113 (2023).

Lodato, F. et al. Analysis of the Spatiotemporal urban expansion of the Rome coastline through GEE and RF Algorithm, using Landsat imagery. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Information. 12 (4), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi12040141 (2023).

Dahy, B. & Burt, J. A. Remote sensing of 50 years of coastal urbanization and environmental change in the Arabian gulf: A systematic review. Front. Remote Sens. 5, 1422910. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsen.2024.1422910 (2024).

Manikandababu, C., Alzaben, N., Maashi, M. & Geetha, M. Mapping coastal urbanization impacts with object-based image classification and land use/land cover change detection: A focus on sustainable development. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 161, 105559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2025.105559 (2025).

Abbasnezhad, B. & Abrams, J. B. Incorporating social and policy drivers into Land-Use and Land-Cover projection. Sustainability 15 (19), 14270. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914270 (2023).

Ikegwuoha, D. C., Weepener, H. L. & Dinka, M. O. Future land use change simulations for the lepelle river basin using cellular automata Markov model with land change Modeller-generated transition areas. F1000Research 10, 796. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.55186.2 (2021).

Aksoy, H. & Kaptan, S. Monitoring of land use/land cover changes using GIS and CA-Markov modeling techniques: a study in Northern Turkey. Environ. Monit. Assess. 193, 507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-021-09281-x (2021).

Khodaei, H., Nasiri Saleh, F., Dalir, N., Zarei, E. & A., & Future flood susceptibility mapping under climate and land use change. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97008-0 (2025).

Jena, P. K., Rahaman, S. M., Mohapatra, P. K. D., Barik, D. P. & Patra, D. S. Surface water quality assessment by random forest. Water Pract. Technol. 18 (1), 201–214. https://doi.org/10.2166/wpt.2022.156 (2023).

Schoppa, L., Disse, M. & Bachmair, S. Evaluating the performance of random forest for large-scale flood discharge simulation. J. Hydrol. 590, 125531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.125531 (2020).

Wahba, M. et al. Forecasting of flash flood susceptibility mapping using random forest regression model and geographic information systems. Heliyon 10 (13), e33982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e33982 (2024).

Osman, A. I. A., Ahmed, A. N., Chow, M. F., Huang, Y. F. & El-Shafie, A. Extreme gradient boosting (Xgboost) model to predict the groundwater levels in Selangor Malaysia. Ain Shams Eng. J. 12 (2), 1545–1551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2020.11.011 (2021).

Parthasarathy, K. & Deka, P. C. Remote sensing and GIS application in assessment of coastal vulnerability and shoreline changes: a review. ISH J. Hydraul Eng. 27, 588–600 (2021).

Wang, M. et al. Interannual changes of coastal aquaculture ponds in China at 10-m Spatial resolution during 2016–2021. Remote Sens. Environ. 284, 113347 (2023).

Ihsan, K., Harto, A., Sakti, A. Wikantika, K. Monitoring coastal areas using NDWI from landsat image Data from 1985 based on cloud computation google earth engine and apps. Int. Arch. Photogramm Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 48 109–114 (2023).

Yang, X., Bai, Y., Che, L., Qiao, F. & Xie, L. Incorporating ecological constraints into urban growth boundaries: A case study of ecologically fragile areas in the upper yellow river. Ecol. Ind. 124, 107436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107436 (2021).

Hasnaoui, Y. et al. Integrated remote sensing and deep learning models for flash flood detection based on Spatio-temporal land use and cover changes in the mediterranean region. Environ. Model. Assess. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10666-025-10035-z (2025).

Singh, S. K., Mustak, S., Srivastava, P. K., Szabó, S. & Islam, T. Predicting Spatial and decadal LULC changes through cellular automata Markov chain models using Earth observation datasets and geo-information. Environ. Processes. 2, 61–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40710-015-0007-x (2015).

Szczepanek, R. Daily streamflow forecasting in mountainous catchment using XGBoost, LightGBM and catboost. Hydrology 9 (12), 226 (2022).

Xu, K., Han, Z., Xu, H. & Bin, L. Rapid prediction model for urban floods based on a light gradient boosting machine approach and hydrological–hydraulic model. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 14 (1), 79–97 (2023).

Mishra, B. R., Vogeti, R. K., Jauhari, R., Raju, K. S. & Kumar, D. N. Boosting algorithms for projecting streamflow in the lower Godavari basin for different climate change scenarios. Water Sci. Technol. 89 (3), 613–634. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2024.011 (2024).

Ghaderi, D., Rahbani, M. A. & Long-Term Survey on the shoreline changes of Gulf of Oman Coasts (Makran). Ocean. Sci. J. 60, 11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12601-025-00208-y (2025).

Abushandi, E. & Abualkishik, A. Shoreline erosion assessment modelling for Sohar region: Measurements, Analysis, and scenario. Sci. Rep. 10, 4048. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61033-y (2020).

Teillet, T. et al. Multidecadal morphodynamic evolution of shorelines and coral reefs along the Arabian Sea coast of Oman: Bar Al Hikman Peninsula. J. Coastal. Conserv. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11852-024-01087-6 (2025).

Al-Awadhi, T., Ramadan, E. & Charabi, Y. Urban development and landuse change patterns in Muscat city, Oman. Int. J. Geoinformatics. 13 (4), 45–55 (2017).

Ansari, T. A. A., Singh, C. K. & Albawwab, W. Urbanization and its impact on land use and land cover in al Buraimi City, Oman using remote sensing and GIS. J. Landsc. Ecol. 18 (2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.2478/jlecol-2025-0009 (2025).

Ren, Q. et al. Impacts of urban expansion on natural habitats in global drylands. Nat. Sustain. 5 (10), 869–878. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-00930-8 (2022).

Mansour, S., Al-Belushi, M. & Al-Awadhi, T. Monitoring Land Use and Land Cover Changes in the Mountainous Cities of Oman Using GIS and CA-Markov Modelling Techniques. 91 (Land Use Policy, 2020).

Funding

The authors would like to thank Sultan Qaboos University for financial support under grant number CL/SQU-UAEU/CESR/24/01.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributionsThe authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of results: MRN, EZ, MA; draft manuscript preparation: MRN, EZ, MA. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nikoo, M.R., Zarei, E. & Al-Wardy, M. Mapping coastal transformations with a novel Cellular Automata–Markov–Random forest framework for land use change modeling. Sci Rep 16, 1469 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31791-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31791-8