Abstract

WDR83 (WD Repeat Domain 83), also known as MORG1 (Mitogen-activated protein kinase Organizer 1), functions as a scaffold protein regulating diverse cellular processes, including cell signaling, proliferation, protein degradation, cell polarity, and autophagy. Through whole-exome sequencing, we identified a novel de novo WDR83 variant [NM_001099737; c.653 T > C,p.(L218P)] in a Japanese female patient presenting with global developmental delay, intellectual disability, and dysmorphic features. As the p.L218P variant was suspected to exert a dominant-negative effect, we investigated its impact on neuronal development. In vivo, acute expression via in utero electroporation promoted premature cell cycle exit of neural stem cells, impaired cortical neuron migration, and disrupted dendritic arborization, whereas axonal projections to the contralateral hemisphere remained unaffected. Additionally, cortical neurons expressing WDR83-L218P exhibited reduced spine head diameter. In vitro, WDR83-L218P expression inhibited axon elongation in primary cultured hippocampal neurons. Collectively, these findings suggest that WDR83 is a novel gene associated with neurodevelopmental disorders. Based on expression profiles and functional analyses, we conclude that WDR83 plays a crucial role in regulating neuronal morphology during brain development, and that the p.L218P variant disrupts this function, contributing to the patient’s phenotype.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

WDR83 (WD Repeat Domain 83), also known as MORG1 (Mitogen-activated protein kinase Organizer 1), is a member of the WD-40 protein family and acts as a scaffold for various proteins. It was initially identified as a binding partner of MP1 (MEK Partner-1), also known as LAMTOR1 (Late endosomal/lysosomal adaptor, MAPK and mTOR activator 1)1,2. The WDR83-MP1 complex has been shown to further associate with ERK1/2 (extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2) and their upstream serine/threonine kinases, Raf-1 and MEK1/2 (MAPK/ERK kinase 1/2), thereby enhancing Raf1-MEK1/2-ERK1/2 signaling2.

Meanwhile, p14, an adaptor protein localized to late endosomes, was identified as a binding partner of MP13. p14 recruits MEK1 and ERK1 via MP1 and spatiotemporally regulates ERK signaling, facilitating endosomal trafficking and cellular proliferation. WDR83 is thought to contribute to this process by stabilizing the larger signaling complex including Raf-14.

Another well-characterized binding partner of WDR83 is PHD3, a prolyl hydroxylase that targets HIF-1α, a transcription factor responsive to hypoxia5,6. Under normoxic conditions, HIF-1α is continuously degraded to maintain low cellular levels7,8,9. PHD3 hydroxylates specific prolines within HIF-1α, initiating its degradation. Through its interaction with PHD3, WDR83 activates or stabilizes PHD3 and promotes HIF-1α degradation10. Furthermore, WDR83 contributes to the establishment of cell polarity in renal epithelial cells by recruiting the Par6-aPKC complex to the apical membrane via interaction with Crumbs311. It also supports basal autophagy by binding to and inhibiting Rag GTPases (RagA-D), leading to suppression of mTORC1, a negative regulator of autophagy12. Thus, WDR83 plays multiple cellular roles depending on its interacting partners.

Homozygous Wdr83 knockout (KO) mice die around embryonic day 11 (E11) due to severe defects in cell proliferation and massive apoptosis. In contrast, heterozygous Wdr83+/- mice display a normal phenotype, with no apparent abnormalities in brain structure or cerebral vascular architecture13,14. Interestingly, these heterozygous mice have been reported to be partially protected from cerebral ischemia compared with wild-type animals15.

Given the multiple functions of WDR83, variants in this gene are presumed to be pathogenic in neurodevelopmental disorders. To date, however, only one variant, p.G127A, has been reported in a proband with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)16, and the pathogenic roles of WDR83 variants remain largely unknown.

In this study, we identified a novel de novo WDR83 variant, c.653 T > C,p.(L218P), in a Japanese female patient presenting with global developmental delay (GDD) and intellectual disability (ID). Based on the hypothesis that this variant represents a gain-of-function mutation, we overexpressed WDR83-L218P in the developing brain. In vivo, WDR83-L218P disrupted the cell cycle of neural stem cells, impaired cortical neuron migration, and compromised dendritic spine formation. In vitro, WDR83-L218P overexpression attenuated neurite outgrowth in cultured hippocampal neurons. Taken together, these findings indicate that WDR83 plays a crucial role in brain development and that its dysfunction can lead to GDD and ID.

Results

Clinical description

The patient is a 7-year-old female who was born prematurely at 36 weeks and 2 days of gestation via cesarean section due to intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). At birth, her anthropometric measurements were as follows: weight 1,142 g (-4.2 SD), length 38 cm (-3.1 SD), and head circumference 27.5 cm (-3.1 SD). She was diagnosed with an atrial septal defect, which was surgically repaired with a patch at 14 months of age. Postoperatively, pulmonary hypertension persisted, necessitating continued oxygen therapy until the age of 15 months. Due to poor weight gain, she required tube feeding until she was 1 year and 4 months old. Developmentally, she exhibited motor delay, and achieved independent walking at 2 years of age. She began speaking meaningful words at 2 years and 9 months. Currently, her developmental delay is mild; she is able to converse in sentences and perform simple addition calculations. She has mild paralysis of the right upper and lower limbs and difficulty extending her right middle finger. Because of asymmetry in the length of her upper limbs, imprinting abnormalities were investigated, but none were found. Dysmorphic features noted on physical examination included hypertelorism, epicanthal folds, short neck, down-slanting eyebrows, and a low hairline.

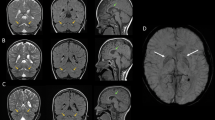

Brain MRI performed on 7 months revealed enlarged bilateral ventricles (Fig. 1). Routine laboratory investigations and metabolic screening were unremarkable. Both standard karyotyping and chromosomal microarray (array-CGH) analyses showed no abnormalities.

At 7 years and 7 months of age, her growth parameters were: height 107.5 cm (− 2.6 SD), weight 15.1 kg (− 3.5 SD), and head circumference 48.0 cm (− 2.5SD).

Molecular diagnosis

The present research protocol was approved by the local institutional board review. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents. We performed trio-based WES analysis. A de novo missense variant in WDR83 was revealed [NM_001099737 Exon9: c.653 T > C,p.(L218P)]. This variant was predicted to be “Probably damaging” with a score of 1.000 by PolyPhen-2 and “Pathogenic Supporting” with a score of 0.001 by SIFT. CADD score was 27.1. This variant was not registered in the Genome Aggregation Database (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org) or Human Genome Mutation Database (http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/). Based on the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics standards and guidelines, these variants were classified as likely pathogenic (PS2, PM1, PM2, PP3).

Expression analyses of WDR83 in the developing mouse brain

High expression of WDR83 in the neuroepithelium of the mouse neural tube at embryonic day 12.5 (E12.5) has been previously reported14. To determine the spatial and temporal distribution of WDR83 during middle and late cortical development, we performed immunohistochemical analyses on paraffin sections using diaminobenzidine staining. At E15, strong immunoreactivity was observed in subplate (SP) neurons and cortical neurons of the deep layers (Fig. 2a, b). Although expression levels varied among individual cells, WDR83 was primarily localized to the nucleus, with moderate signals in the perinuclear region (Fig. 2b, right). Notably, immunostaining was nearly undetectable in the intermediate zone (IZ), suggesting limited expression in axons. Within the ventricular zone (VZ), punctuated signals were found at the apical surface (Fig. 2c). Similar dotty signals were observed using fluorescent immunohistochemistry on frozen sections at E14 (Fig. 2d), suggesting that these signals are not artifacts. At P0, moderate WDR83 signals were observed in the neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and piriform cortex (Fig. 2e). No detectable staining was seen in major axon fascicles, including the corpus callosum, anterior commissure, and internal capsule. By P7, immunohistochemical signal intensity had markedly declined (Fig. 2d). Nevertheless, weak but discernible expression persisted in the upper cortical plate (CP), hippocampal pyramidal cell layer, and piriform cortex. Taken together, these findings indicate that WDR83 is expressed in the cell bodies of postmitotic neurons and the apical surface of neural stem cells during embryonic development, with its expression being most prominent at early developmental stages.

Immunohistochemical analysis of WDR83. Coronal sections of E15 (a-c), E14 (d), P0 (e), and P7 (f) brains were stained with anti-WDR83 using diaminobenzidine (a-c, e, f) or a fluorescent dye-conjugated antibody (d, green) and DAPI (counterstaining, blue). A high magnification view of the boxed area in (a) was shown in (b, left) and (c). Further magnification views of the boxed areas in (b, left) were shown on the right (i-iii). A high magnification view of the boxed area in (d, e, f, left) was shown on the right. MZ, marginal zone; CP, cortical plate; SP, subplate; IZ, intermediate zone; Ctx, cerebral cortex; CC, corpus callosum; CA1-3, hippocampal CA1-3 area, DG, dentate gyrus; Str, striatum; AC, anterior commissure; PC, piliform cortex, Scale bars: 200 µm (a), 50 µm (b-left, d-left), 20 µm (b-right, c, d-right), 500 µm (c, d).

Overexpression of WDR83-L218P causes impaired proliferation of neural stem cells and migration of cortical neurons

We identified a novel de novo WDR83 variant, p.L218P, in a Japanese female patient with neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) (Fig. 3a). When pCAG-Myc-WDR83-L218P was transfected into COS7 cells, its expression level was comparable to that of wild-type (WT) WDR83 (Fig. 3b), indicating that the amino acid substitution does not affect protein stability. We hypothesized that the p.L218P variant may exert a gain-of-function effect, based on the following observations: the variant was confirmed to be de novo by trio-based sequence analysis, and heterozygous Wdr83 KO mice show no obvious phenotype, whereas homozygous KO mice are embryonic lethal13,14. Therefore, we investigated the impact of WDR83-L218P overexpression on neuronal development in the cerebral cortex. A previous study reported strong WDR83 expression in the neuroepithelium at E12.5, and a reduction in Ki67-positive proliferative cells in the neural tube of Wdr83 KO mice at E8.514. Additionally, we observed WDR83 localization at the apical surface of VZ cells. Based on this, we examined the effect of WDR83-L218P on neural stem cell proliferation (Fig. 3c, d). pCAG-Myc-WDR83 (WT) or pCAG-Myc-WDR83-L218P was co-electroporated with pCAG-EGFP into embryonic cortices at E12 via in utero electroporation. EdU was administered at E13 to label S-phase cells, and embryos were fixed at E14. Cortical sections were stained for Ki67 and EdU, and the cell cycle re-entry index (the percentage of EdU/GFP/Ki67 triple-positive cells among EdU/GFP double-positive cells) was calculated. This index was significantly lower in WDR83-L218P–expressing cells compared with WT, suggesting that the variant impairs cell cycle progression and/or promotes premature differentiation. We next assessed the effect of WDR83-L218P on cortical neuron migration. The same plasmid constructs were electroporated at E14, and the distribution of GFP-positive neurons was analyzed at P2. In WT-expressing neurons, most cells successfully migrated to the upper CP (uCP). In contrast, WDR83-L218P overexpression caused a significant reduction in the neuron population reaching the uCP and resulted in stacking some population in the IZ (Fig. 3e, f). Although defects in nucleus–centrosome coupling have been implicated in impaired neuronal migration17,18, we observed no significant change in the distance between the nucleus and centrosome in migrating neurons at E18 (Supplementary Fig. S1a, b). Considering that WDR83 is predominantly expressed in postmitotic neurons within the CP from E15 to P0 (Fig. 2), the migration deficits might be a secondary result of reduced neuronal output in the VZ due to impaired cell cycling19,20 (Fig. 3c, d). However, the possibility cannot be ruled out that WDR83 directly regulates neuronal migration through a yet unidentified molecular mechanism. Taken together, these results demonstrate that WDR83-L218P overexpression disrupts both the production and migration of cortical neurons.

Effects of WDR83-L218P overexpression on neural stem cell proliferation and neuronal migration. (a) Schematic representation of the domain structure of WDR83 protein and the position of the p.L218P variant. The previously reported p.G127R variant is also shown. (b) Expression of Myc-tagged WDR83 (WT) or WDR83-L218P in COS7 cells. Western blotting was performed using anti-Myc. Molecular weight markers (kDa) are shown on the right. Note that protein bands cropped from different regions of the same gel have been grouped for presentation. (c, d) Overexpression of WDR83-L218P reduced cell cycle reentry in neural stem cells. E12 mouse embryos were co-electroporated with pCAG-Myc-WDR83 (WT, 0.5 µg) or pCAG-Myc-WDR83-L218P (0.5 µg), together with pCAG-EGFP (0.5 µg), and administrated EdU. Coronal brain sections were stained with anti-GFP (c, green), Ki-67 (white), and DAPI (blue). EdU-positive cells were detected on the same sections (red). Scale bar: 50 µm. The frequency of cell cycle re-entry (defined as the proportion of GFP/EdU/Ki-67 triple-positive cells among total GFP/EdU double-positive cells) was quantified (d). Statistical significance was assessed using Student’s t-test (WT, 7 brains; L218P, 6 brains from two independent experiments; WT vs L218P; *P = 0.0216; error bars = SD). (e) E14 mouse embryos were co-electroporated with pCAG-Myc-WDR83 (WT, 0.5 µg) or pCAG-Myc-WDR83-L218P (0.5 µg), together with pCAG-EGFP (0.5 µg). Fluorescent images of GFP (white) and DAPI (blue) of coronal sections at P2 were acquired. Scale bar: 100 µm. (f) The proportion of GFP + cells in each area (upper, medial, lower CP, IZ, and VZ) (e) was counted. Statistical significance was assessed using two-way ANOVA (interaction between areas and transfected plasmids, P < 0.0001) followed by Fisher’s LSD test for each area (WT, 6 brains; L218P, 5 brains from two independent experiments; WT vs L218P; uCP, ****P < 0.0001; mCP, P = 0.4131; lCP, P = 0.2710; IZ, *P = 0.0152; VZ, P = 0.0532. Error bars = SD).

Overexpression of WDR83-L218P impedes neurite outgrowth and dendritic spine formation

We next investigated the effects of WDR83-L218P overexpression on neuronal morphogenesis. Although axon elongation tended to be delayed in vivo, no statistically significant differences were observed in the formation of callosal axons from layer II/III neurons when either pCAG-Myc-WDR83 (WT) or pCAG-Myc-WDR83-L218P was electroporated at E14 and analyzed at P2 (Supplementary Fig. S1c, d). To further examine the cell-autonomous effects of the variant on axon development, dissociated hippocampal neurons were transfected with either WT or pCAG-Myc-WDR83-L218P together with pCAG-EGFP and cultured for 3 days in vitro. As a result, both axon length (defined as the longest neurite) and total neurite length were significantly shorter in WDR83-L218P–transfected neurons than in those transfected with WT (Fig. 4a–c). Finally, we evaluated the impact of WDR83-L218P on dendritic spine development in vivo. In utero electroporation was performed at E14 with either WT or WDR83-L218P, and brains were fixed at P15. As previously shown (Fig. 3e, f), WDR83-L218P-expressing neurons exhibited migration defects. Therefore, we focused our analysis on neurons that had successfully reached layer II/III. As a result, although the dendritic arborization of WDR83-L218P–expressing neurons and the spine density on basal dendrites were comparable to that of WT neurons (Supplementary Fig. S2a, b, Fig. 4d, e), the spine head diameter was significantly smaller in WDR83-L218P–expressing neurons than in WT controls (Fig. 4f), indicating that the p.L218P variant impairs spine maturation. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that overexpression of WDR83-L218P impairs neuronal morphogenesis, including neurite outgrowth and dendritic spine formation.

Effects of WDR83-L218P expression on neuronal morphology. (a–c) Effects on neurite outgrowth in cultured hippocampal neurons. Neurons were transfected with pCAG-Myc (empty vector), pCAG-Myc-WDR83 (WT), or pCAG-Myc-WDR83-L218P (0.6 µg), together with pCAG-EGFP (0.2 µg). Neurite length was measured at 3 days in vitro. The longest neurite was defined as the axon. (a) Representative images of GFP-positive neurons. Scale bar: 50 µm. (b, c) Violin plots showing axon length (b) and total neurite length (c). Statistical analysis was performed using Kruskal–Wallis test (P < 0.0001 for both), followed by Dun’s post hoc test (b, empty vs WT, *P = 0.0475, empty vs L218P, ***P = 0.0005, WT vs L218P, *****P < 0.0001; c, empty vs WT, P = 0.1279, empty vs L218P, ****P < 0.0001, WT vs L218P, **P = 0.0041). (d-f) Effects on dendritic spine formation in vivo. E14 mouse embryos were co-electroporated with pCAG-Myc-WDR83 (WT) or pCAG-Myc-WDR83-L218P (1 µg each), together with pCAG-M-Cre (0.5 ng) and pCALNL-EGFP (0.5 µg). Coronal sections were prepared at P15, and basal dendrites of layer II/III neurons in the somatosensory cortex were imaged. (d) Representative images of basal dendrites from GFP-positive neurons. Scale bar: 5 µm. (e) There was no significant difference in spine density between WT and L218P transfected neurons (Student’s t-test, WT, 9 dendrites; L218P, 13 dendrites; P = 0.1933). (f) Spine head diameters were shown in bar graphs with dot plots. Horizontal lines indicate the median. Statistical significance was assessed using the Mann–Whitney test (WT, 709 spines; L218P, 1142 spines; **P = 0.0095).

Discussion

WDR83 is known to play crucial roles in various functions, including signaling, proliferation, autophagy, and cell polarity, depending on its binding partners. Given its high expression in the embryonic central nervous system14, defects in WDR83 were hypothesized to cause NDDs. In this study, we identified a novel de novo variant in a Japanese patient with GDD and ID. Together with a previously reported variant identified in a patient with ADHD16, our findings support the pathogenic role of WDR83 variants in NDDs.

Because the p.L218P variant was hypothesized to exert a gain-of-function effect, we performed overexpression studies both in vitro and in vivo. These experiments revealed impairments in neural stem cell proliferation, migration of layer II/III cortical neurons, and dendritic spine formation in vivo. In addition, neurite outgrowth was significantly reduced in cultured hippocampal neurons, although elongation of axon bundle was not affected by the variant expression in vivo. These phenotypes may be related to clinical features observed in the patient, such as GDD and ID.

In this study, we did not investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of the p.L218P variant in detail. Perturbation of ERK/MAP-kinase signaling was one of the hypothesized mechanisms. However, we did not observe significant differences in ERK phosphorylation levels in cell lysates from COS7 cells transfected with either wild-type WDR83 or WDR83-L218P (Supplementary Fig. S3). Nevertheless, we cannot exclude the possibility that the subcellular localization of phosphorylated ERK1/2 is altered due to impaired binding of WDR83-L218P to certain anchoring proteins. MP1 is a potential candidate, although its exact binding site on WDR83 has yet to be clearly determined.

While the base substitution c.653 T > C,p.(L218P) is located within the WD5 domain (Fig. 3a), no binding partners specific to this domain have been identified to date. PHD3 and RegA-D are known to bind to the N-terminus of WDR83, whereas the binding sites for Raf-1, MEK, and ERK remain undetermined. Notably, L218 and its surrounding amino acid sequence are highly conserved from Drosophila to mammals, suggesting the presence of an as-yet unidentified protein that interacts with this region.

While the base substitution c.653 T > C, p.(L218P) is located within the WD5 domain (Fig. 3a), no binding partners specific to this domain have been identified to date. Known interactors such as PHD3 and RegA-D bind to the N-terminus of WDR83, whereas the binding sites for Raf-1, MEK, and ERK remain undetermined. Given that L218 and its surrounding amino acid sequence are highly conserved from Drosophila to mammals, it is plausible that this region mediates interaction with as-yet unidentified proteins. Alternatively, although further investigation is required, the WD5 domain may interact with components of the evolutionarily conserved Raf-1–MEK–ERK signaling pathway, whose binding sites on WDR83 remain to be determined.

Microcephaly was observed in the present patient. A previous study reported that WDR83 was highly expressed in the mouse neuroepithelium at E12.5, and that proliferation of neuroepithelial cells is reduced in homozygous Wdr83 KO mice, whereas no abnormal phenotype is observed in heterozygous mice13,14. In our study, we found that the expression of WDR83-L218P reduced neural stem cell proliferation. If the p.L218P variant acts in a dominant-negative manner, this may account for the microcephaly observed in the patient. Some variants of genes encoding scaffold proteins are known to exert dominant-negative effects. For example, protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) is a heterotrimeric protein complex composed of A-, B-, and C-subunits, in which the A-subunit functions as a scaffold for the regulatory B and catalytic C-subunits21. Certain variants in the PPP2R1A gene, which encodes the A-subunit, disrupt its ability to bind the B-subunit, leading to the trapping of the limited available C-subunits, thereby resulting in insufficient formation of functional PP2A complexes22. Similarly, it is possible that WDR83-L218P exerts its effects through a dominant-negative mechanism. Further studies, including the identification of relevant binding partners, are required to elucidate the molecular pathogenesis of WDR83 variants.

Conclusions

We report a novel de novo pathogenic variant of the WDR83 gene, c.653 T > C,p.(L218P), in a Japanese female patient presenting with GDD and ID. In mice, WDR83 protein is highly expressed during early brain development and is subsequently downregulated after birth. Within the developing cerebral cortex, WDR83 is predominantly expressed in a subset of differentiated neurons. The p.L218P variant was predicted to confer a gain-of-function effect. Overexpression of WDR83-L218P in mice via in utero electroporation led to reduced proliferation of neural stem cells (as evidenced by decreased cell cycle re-entry at E12–E14), impaired migration of layer II/III cortical neurons at P2, and diminished dendritic spine maturation at P15. In vitro, transfection of WDR83-L218P into dissociated hippocampal neurons inhibited neurite outgrowth. These phenotypes may partially recapitulate the clinical manifestations observed in the patient, including GDD, ID, and microcephaly. Although the precise molecular mechanisms underlying these effects remain to be elucidated, this study provides new insights into the pathological significance of WDR83 variants in NDDs.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Research involving human subjects was approved by the Central Ethics Committee at Tohoku University (Institutional Review Board approval number: 34742), and informed consent was obtained from the parents of participating individuals. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org) and complied with the institutional regulations under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan. All animal experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute for Developmental Research, Aichi Developmental Disability Center (approval number: 2024–002).

Animals

All animals were housed at 22–24 °C with 40–60% humidity under a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 a.m., off at 7:00 p.m.), with free access to food and water. Noon on the day a vaginal plug was observed was designated as E0.5.

Plasmids

Human WDR83 cDNA was isolated by RT-PCR from an mRNA pool from human glioblastoma U251 cells, and then cloned into pCAG-Myc vector23 to construct pCAG-Myc-WDR83. Expression vector for WDR83-L218P was constructed by introducing a one-base substitution to pCAG-Myc-WDR83 using KOD-Plus Mutagenesis kit (Toyobo Inc., Tokyo, Japan). pCAG-PACT-mKO (a monomeric Kusabira-Orange fused with centrosome localization signal-expression vector) was provided by Dr. F. Matsuzaki24. To construct pCAG-mNeptune2, the mNeptune2 cDNA was amplified by PCR from pcDNA3-mNeptune2-N, a gift from Dr. Michael Lin (Addgene plasmid #41,645; http://n2t.net/addgene:41645; RRID: Addgene_41645)25, and inserted into pCAGGS. To achieve sparse labeling of neurons, the Cre-LoxP system was used. pCAG-M-Cre was from Dr. S. Miyagawa26. The construction of pCALNL-EGFP, a Cre-dependent EGFP expression vector under the control of CAG promoter, was described previously27. pCALNL-DsRed was a gift from Connie Cepko (Addgene plasmid #13,769; http://n2t.net/addgene:13769; RRID: Addgene_13769), and its DsRed was swapped with EGFP cDNA from pEGFP-N1 (Clontech Inc., Palo Alto, CA).

Western blotting

For detection of Myc-tagged WDR83-WT and -L218P expression (Fig. 2b), COS7 cells, a cell line derived from green monkey kidney, were transfected with expression plasmids (pCAG-Myc-WDR83-WT or -L218P, 0.5 µg/35 mm dish each) using polyethyleneimine (PEI MAX, Polysciences Inc., Warrington, PA, Cat#24,765–1). Lysates of COS7 cells 2 days after transfection were subjected to SDS-PAGE (15% acrylamide) and transferred onto PVDF membranes. After blocking with 2% skim milk, the membranes were incubated with anti-Myc (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, Cat#2276, RRID: AB_331783, 1:1000) or anti-β-Tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich Inc., St. Louis, MO, Cat#T4026, 1:2000) antibody at 4 °C overnight, and then reacted with horse-radish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Dallas, TX, Cat#sc-2314, 1:2000) for 1 h. The chemiluminescent reaction was conducted using Western Lightning Plus ECL (Perkin Elmer Inc., Waltham, MA), and the signals were captured by LAS 4000 mini (Fuji Film Inc., Tokyo, Japan).

For ERK phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. S3), COS7 cells were co-transfected with pCAG-Myc-WDR83-WT or -L218P and pCAG-FLAG-ERK (0.3 µg/35 mm dish each). Cells were serum-deprived one day after transfection in serum free DMEM for 20 h. Cells were either lysed without serum stimulation (0 min) or with stimulation with 10% FBS in DMEM for 5, 10, 20 min. Lysates were analyzed with Western blotting as described above. The membranes were incubated with anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat#9101, RRID:AB_331646, 1:1000), total ERK1/2 antibody (New England Biolabs, Cat#9102, 1:1000), or anti-β-Tubulin (described above).

Immunohistochemistry

Mice in different stages were perfused with 4% PFA and the brains were dissected out. For diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining, the brains were embedded in paraffin, and sectioned coronally in 4-µm thickness. After deparaffinization, sections were incubated at 70 °C for 20 min in Histo-VT One (Nacalai Tesque Inc., Tokyo, Japan) for antigen retrieval. After blocking with 0.1% BSA, sections were incubated with anti-WDR83 (ATLAS Antibodies Inc., Stockholm, Sweden, Cat#HPA042629, 1:200) at 4 °C overnight. Secondary antibody reaction and signal enhancement were performed using Takara POD Conjugate for Tissue kit (Takara Bio Inc., Tokyo, Japan, Cat#MK204) with DAB substrate (Takara Bio Inc., Cat#MK210). Images were captured using a bright field microscope (Keyence Inc., Osaka, Japan, BZ-X800). For fluorescent immunohistochemistry, the brains were cryoprotected with 30% sucrose in PBS, embedded in O.C.T compound (Tissue-Tek Sakura Inc., Torrance, CA), and cut coronally into 14 µm sections using a cryostat (CM-3000, Leica). Sections were blocked and incubated with anti-WDR83 as described above. After washing, sections were incubated with anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) and DAPI (0.2 µg/mL). Fluorescent images were obtained using a confocal microscope (LSM880, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

In utero electroporation

The method for in utero electroporation was described previously28,29. Pregnant mice at E14 (at E12 for cell cycle analysis, which is described in another section) were deeply anesthetized with medetomidine-midazolam-butorphanol anesthetic at a dose of 0.3 mg/kg, 4 mg/kg, and 5 mg/kg body weight (40–65 g), respectively30. Plasmid solution was injected into one of the lateral ventricles of the embryos and electronic pulses (35 V, 5 times) were applied using a tweezer-type electrode (5 mm diameter, NEPA gene Inc., Chiba, Japan, or BEX Inc., Tokyo, Japan) connected to an electroporator (NEPA gene, NEPA21). After the surgery, dams were quickly administered anti-anesthetic (atipamezole 0.3 mg/kg body weight). The manipulated embryos were allowed to grow, and fixed with 4% PFA at appropriate stages (E17 for centrosome-nuclear coupling, P2 for migration and axon analyses, P14 for dendritic branching and spine morphology). To collect E17 brains, dams were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane and euthanized by cervical dislocation. Embryos were then removed and placed in ice-cold PBS. P2 and P14 pups were deeply anesthetized with 2% isoflurane; P2 pups were placed on ice due to reduced anesthetic efficacy at this age. Embryos and pups were subsequently perfused with 4% PFA, and their brains were dissected for further analysis.

Cell cycle analysis

The cell cycle re-entry index was essentially determined according to a previous study27,31. Plasmids described in the figure legend were electroporated in utero at E12. Twenty-four hours after electroporation, 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU, Invitrogen Inc., Carlsbad, CA) was applied intraperitoneally at 25 mg/kg body weight. Twenty-four hours after the EdU injection, brains were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, cryoprotected with 30% sucrose in PBS, embedded in O.C.T compound (Tissue-Tek Sakura Inc., Torrance, CA), and cut coronally into 14 µm sections using a cryostat (CM-3000, Leica). The sections around the level of the interventricular foramen were stained with anti-Ki67 (Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA, Cat# ab15580, 1:500) and anti-GFP antibodies (Aves Labs Inc., Tigard, OR, Cat# GFP-1010, RRID: AB_2307313, 1:3000) overnight, followed by secondary antibody (anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa Fluor 647, Invitrogen) and anti-chicken IgY-Alexa Fluor 488 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, Cat# 703–545-155) and DAPI (nuclear staining, 0.2 µg/mL). The sections were subsequently processed for EdU detection using Click-iT™ EdU imaging kit with Alexa Fluor 555 (Invitrogen). Images were captured using a confocal microscope (LSM880, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). EdU-GFP double-positive cells and Ki67-EdU-GFP triple-positive cells were counted manually by using the “cell counter” plugin of ImageJ software ver. 2.14.0.

Tissue preparation and morphological analyses

Electroporated brains fixed at E17, P2, or P14 (see above) were embedded in 3% agarose in PBS and coronally sliced using a vibrating microtome at 100 µm thickness (VT1000, Leica Biosystems Inc., Wetzlar, Germany). As to the analyses of neuronal migration, slices of P2 brains at the level of the interventricular foramen were stained with DAPI (0.2 µg/mL) and the fluorescence of GFP, DAPI (for investigating the distribution of GFP positive cells), or with mKO and mNeptune2 (for centrosome-nucleus coupling assay32) were imaged by confocal microscopy. The radial distribution of GFP+ cells and the distance between the centrosome and nucleus were measured using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). To assess the callosal-axon elongation in vivo, slices of P2 brains at the level of the septum were immunostained with anti-GFP antibody (Aves Labs, Cat# GFP-1010, RRID: AB_2307313, 1:3000) overnight followed by secondary antibody (anti-chicken IgY-Alexa Fluor 488, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, PA, Cat# 703–545-155) and DAPI. Fluorescent images were captured using a fluorescent microscope (Keyence, BZ-X800), and the intensity of Alexa Fluor 488 was measured with ImageJ software (NIH). For the investigation of dendrite and spine morphology, coronal slices of P14 brains were incubated in Epitope Retrieval Solution pH 9 (Leica Biosystems, Cat# RE7119-CE) at 50 °C for 3 h, followed by immunohistochemistry with anti-GFP antibody and its secondary antibody as described above. Fluorescent images of dendrites and dendritic spines of layer II/III neurons in the somatosensory area were obtained using LSM880, and processed with the Filament Tracer function of Imaris software (version 9.2.0, Bitplane Inc., Zurich, Switzerland). The traced images were analyzed further using Sholl and spine morphology analyses, both of which were performed using Imaris software.

Morphological analysis of cultured hippocampal neurons

Hippocampal neurons were cultured according to the standard protocol33. Neurons were prepared from E16 mouse embryos, electroporated with pCAG-Myc-WDR83 or other expression plasmids of the variants (0.6 µg) together with pCAG-EGFP (0.2 µg) using Neon™ transfection system (Invitrogen), and cultured on poly-L-lysine coated coverslips in Neurobasal medium supplemented with B27 (Invitrogen). The images of the GFP-positive neurons at 3 days in vitro were captured using a fluorescent microscope (Keyence, BZ-X800). Neurites were traced by using ImageJ software.

Data availability

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files). The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the LOVD repository (https://www.lovd.nl/, accession number #0,001,047,568).

References

Schaeffer, H. J. et al. MP1: A MEK binding partner that enhances enzymatic activation of the MAP kinase cascade. Science 281, 1668–1671 (1998).

Vomastek, T. et al. Modular construction of a signaling scaffold: MORG1 interacts with components of the ERK cascade and links ERK signaling to specific agonists. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 6981–6986 (2004).

Teis, D. et al. p14–MP1-MEK1 signaling regulates endosomal traffic and cellular proliferation during tissue homeostasis. J. Cell Biol. 175, 861–868 (2006).

Kolch, W. Coordinating ERK/MAPK signalling through scaffolds and inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6, 827–837 (2005).

Bruick, R. K. & McKnight, S. L. A conserved family of Prolyl-4-hydroxylases that modify HIF. Science 294, 1337–1340 (2001).

Ivan, M. et al. Biochemical purification and pharmacological inhibition of a mammalian prolyl hydroxylase acting on hypoxia-inducible factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 13459–13464 (2002).

Bruick, R. K. Oxygen sensing in the hypoxic response pathway: regulation of the hypoxia-inducible transcription factor. Genes Dev. 17, 2614–2623 (2003).

Wang, G. L., Jiang, B. H., Rue, E. A. & Semenza, G. L. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 5510–5514 (1995).

Wenger, R. H. Cellular adaptation to hypoxia: O2 -sensing protein hydroxylases, hypoxia-inducible transcription factors, and O2 -regulated gene expression. FASEB j. 16, 1151–1162 (2002).

Hopfer, U., Hopfer, H., Jablonski, K., Stahl, R. A. K. & Wolf, G. The Novel WD-repeat protein morg1 Acts as a molecular scaffold for hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase 3 (PHD3). J. Biol. Chem. 281, 8645–8655 (2006).

Hayase, J. et al. The WD40 protein Morg1 facilitates Par6–aPKC binding to Crb3 for apical identity in epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 200, 635–650 (2013).

Abudu, Y. P., Kournoutis, A., Brenne, H. B., Lamark, T. & Johansen, T. MORG1 limits mTORC1 signaling by inhibiting Rag GTPases. Mol. Cell https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2023.11.023 (2023).

Hammerschmidt, E., Loeffler, I. & Wolf, G. Morg1 heterozygous mice are protected from acute renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 297, F1273–F1287 (2009).

Wulf, S. et al. Targeted disruption of the MORG1 gene in mice causes embryonic resorption in early phase of development. Biomolecules 13, 1037 (2023).

Stahr, A. et al. Morg1+/− heterozygous mice are protected from experimentally induced focal cerebral ischemia. Brain Res. 1482, 22–31 (2012).

Kim, D. S. et al. Sequencing of sporadic Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) identifies novel and potentially pathogenic de novo variants and excludes overlap with genes associated with autism spectrum disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. Pt B 174, 381–389 (2017).

Shu, T. et al. Ndel1 operates in a common pathway with LIS1 and cytoplasmic dynein to regulate cortical neuronal positioning. Neuron 44, 263–277 (2004).

Tanaka, T. et al. Lis1 and doublecortin function with dynein to mediate coupling of the nucleus to the centrosome in neuronal migration. J. Cell Biol. 165, 709–721 (2004).

Lange, C., Huttner, W. B. & Calegari, F. Cdk4/CyclinD1 overexpression in neural stem cells shortens G1, delays neurogenesis, and promotes the generation and expansion of basal progenitors. Cell Stem Cell 5, 320–331 (2009).

Tsunekawa, Y. et al. Cyclin D2 in the basal process of neural progenitors is linked to non-equivalent cell fates. EMBO J. 31, 1879–1892 (2012).

Remmerie, M. & Janssens, V. PP2A: A promising biomarker and therapeutic target in endometrial cancer. Front. Oncol. 9, 462 (2019).

Haesen, D. et al. Recurrent PPP2R1A mutations in uterine cancer act through a dominant-negative mechanism to promote malignant cell growth. Can. Res. 76, 5719–5731 (2016).

Kawauchi, T., Chihama, K., Nishimura, Y. V., Nabeshima, Y.-I. & Hoshino, M. MAP1B phosphorylation is differentially regulated by Cdk5/p35, Cdk5/p25, and JNK. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 331, 50–55 (2005).

Konno, D., Kiyonari, H., Miyata, T. & Matsuzaki, F. Neuroepithelial progenitors undergo LGN-dependent planar divisions to maintain self-renewability during mammalian neurogenesis. Nat. Cell. Biol. 10, 93–101 (2007).

Zhou, X. X., Chung, H. K., Lam, A. J. & Lin, M. Z. Optical control of protein activity by fluorescent protein domains. Science 338, 810–814 (2012).

Koresawa, Y. et al. Synthesis of a new cre recombinase gene based on optimal codon usage for mammalian systems. J. Biochem. 127, 367–372 (2000).

Hamada, N. et al. Role of the cytoplasmic isoform of RBFOX1/A2BP1 in establishing the architecture of the developing cerebral cortex. Mol. Autism 6, 56 (2015).

Tabata, H., Nagata, K. & Nakajima, K. Time-lapse imaging of migrating neurons and glial progenitors in embryonic mouse brain slices. JoVE https://doi.org/10.3791/66631 (2024).

Tabata, H. & Nakajima, K. Efficient in utero gene transfer system to the developing mouse brain using electroporation: Visualization of neuronal migration in the developing cortex. Neuroscience 103, 865–872 (2001).

Kawai, S., Takagi, Y., Kaneko, S. & Kurosawa, T. Effect of three types of mixed anesthetic agents alternate to ketamine in mice. Exp. Anim. 60, 481–487 (2011).

Siegenthaler, J. A. & Miller, M. W. Transforming growth factor β1 promotes cell cycle exit through the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 in the developing cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci. 25, 8627–8636 (2005).

Hamada, N. et al. Essential role of the nuclear isoform of RBFOX1, a candidate gene for autism spectrum disorders, in the brain development. Sci. Rep. 6, 30805 (2016).

Goslin, K., Asmussen, H. & Banker, G. Rat hippocampal neurons in low-density culture. in (eds Banker, G. & Goslin, K.) 339–370 (Culturing Nerve Cells, 1998).

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Takako Nagano, Ms. Nobuko Hane, Ms. Noriko Kawamura, and Ms. Ikuko Iwamoto for technical assistance.

Funding

This work was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI Grant (grant numbers: 23K24310, 22K19498, 24K02424, and 25K02630) and Research on the Initiative on Rare and Undiagnosed Diseases from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (Grant Number: 24ek0109760h0001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.T. and H.I. performed in vivo and in vitro experiments. K.Y. and T.K. performed genetic analyses. R.S. performed immunohistochemical analyses. Y.H., E.N., and N.O. evaluated the patient and obtained clinical information. H.T., N.O., and K.N. conceived and designed the experiment and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tabata, H., Hasegawa, Y., Yanagi, K. et al. The p.L218P variant in WDR83 disrupts neuronal development, leading to neurodevelopmental disorder. Sci Rep 16, 2213 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31794-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31794-5