Abstract

Community-based tuberculosis screening using mobile X-ray units can effectively increase case detection rates by reducing barriers to accessing services. This study evaluated the multi-armed bandit (MAB) framework, a machine learning approach, for optimizing mobile screening locations. Using simulations, we compared two MAB algorithms—Exp3 and LinUCB—with strategies based on historical case rates and random placement. The MAB algorithms continually updated site selection based on observed screening yields, and LinUCB additionally incorporated local socioeconomic indicators associated with tuberculosis rates. Over three years, assuming two mobile units serving 95 sites in Lima, Peru, 1,000 simulations demonstrated the MAB algorithms significantly reduced the average number of screenings needed to detect one individual with tuberculosis: 112 (standard deviation [SD]: 10) for Exp3 and 79 (SD: 12) for LinUCB, versus 152 (SD: 11) for random placement and 143 (SD: 11) for historic case-rate-driven placement. LinUCB performed best, achieving a 20% increase in detection efficiency by week 16 and 50% by week 40 compared to case-rate-driven placement. Overall, both MAB algorithms improved tuberculosis screening yields, emphasizing the value of data-driven approaches for optimizing mobile screening interventions. Incorporating adaptive models into screening programs may enhance targeting efficiency and offers a promising direction for policymakers and implementers seeking to optimize resource allocation in high-burden setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over 10 million people are estimated to fall ill with tuberculosis (TB) each year, with 24% going undetected by health systems in 20231. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated this case-detection gap, leading to an increase in undiagnosed TB, excess disease, and mortality2,3,4. Because most people with active TB disease do not know they have the disease, targeted active screening is crucial for enhancing TB detection and breaking transmission cycles globally5. Community-based screening via mobile X-ray units is an effective strategy, facilitating convenient access to screening within local communities6.

As mobile TB screening units are deployed in low- and middle-income countries with high TB burdens, understanding their optimal placement within communities to maximize TB detection and making real-time decisions on screening locations is critical. While these mobile units have improved local TB detection7, there has been limited evidence generated about their effective implementation in high-burden settings8. Additionally, studies have identified that targeting mobile screenings toward geographic TB “hotspots” or areas previously found to have a high rate of TB can be efficient, but open questions remain as to how to identify and prioritize these areas, particularly in the context of a long-term or ongoing screening9,10,11,12.

The Multi-Armed Bandit (MAB) framework13 is well-suited for real-time decision-making regarding mobile unit placement. MAB algorithms dynamically determine how to allocate a resource among a set of competing options, updating recommendations as new information is learned. These algorithms have been considered for use in health research for decades, originally proposed as a model for allocating patients to arms of a clinical trial and more recently for targeting mobile and digital health interventions14,15,16,17,18. In our context, MAB algorithms continuously refine their predictions of emerging TB burdens based on ongoing screening yields, solving a classic problem in this field of decision-making science of balancing the need to exploit known areas and explore less-intervened locations. This dynamic decision-making process, informed by continuously collected data, is referred to as an adaptive strategy, which enables targeted interventions for more efficient TB identification.

MAB algorithms have been previously explored as a strategy for directing placement of mobile screening units17. Previous studies have shown MAB’s potential in directing screening locations for HIV19 and TB20 using simulations, as well as directing pop-up COVID-19 screening stations in a feasibility study conducted in Columbus, Ohio21,22. Another simulation study demonstrated improved efficiency in using MABs to conduct active screening for COVID-19 in New York City23. These studies suggest that use of MAB to guide mobile health intervention placement could significantly improve TB screening yields20. However, these studies have focused on a specific MAB algorithm, Thompson Sampling, which relies heavily on prior knowledge of local disease incidence14. In particular, these prior simulations have used either hypothetical data on underlying disease prevalence in a geographic area of interest or estimates of local disease prevalence from prior studies. Because such tailored priors for each local area can be burdensome to obtain or may not be available, we explored two alternative MAB algorithms—Exponential-weight algorithm for Exploration and Exploitation (Exp3)24 and Linear Upper Confidence Bound (LinUCB)25—that rely less on prior knowledge.

We explored the performance of these algorithms in the context of an ongoing mobile TB screening program in Lima, Peru, developing a simulation based on the screening yields observed from the operation of the mobile screening program over the course of a year. We compared simulated yields of mobile TB screening units using four placement strategies: (1) random placement, (2) historic case-rate-driven placement, (3) Exp3, and (4) LinUCB, specifically in the Carabayllo district of Lima, Peru.

Methods

Study setting and population

Our study focuses on a mobile TB screening program, called TB Movil, that operated in the Carabayllo, Comas, and Independencia districts of Lima, Peru7. These districts, home to approximately 1.1 million individuals, are among the most impoverished areas in Lima, with many residents living in informal dwellings on steep hillsides lacking basic infrastructure26. High rates of TB are prevalent in these regions27. As of the 2017 census, the Carabayllo district had around 212,000 residents26. From 2013 to 2017, prior to TB Movil’s launch, the annual TB case rate was 124 cases per 100,000 population, with significant geographic variation across neighborhoods9.

Mobile screening program

TB Movil was initiated in February 2019 through a partnership between the non-governmental organization Socios En Salud, municipal governments, and community organizations7. The program employed two mobile screening units equipped with X-ray machines, providing free chest radiography and TB screening services to community members, regardless of symptoms.

Mobile units were strategically placed in areas with high prior TB notification rates and high foot traffic, such as markets and transit terminals7. Before the program’s launch, maps defining the spatial boundaries of 74 neighborhoods in Carabayllo were created in consultation with community leaders. A community engagement strategy was implemented in each neighborhood to raise awareness and encourage attendance.

All attendees were registered, providing demographic information including age, sex, and neighborhood of residence. Following registration, chest radiography was performed by a technician and scored using CAD4TB V6.0 (Delft Imaging, Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands). If an abnormality was detected, a clinician conducted a physical examination and requested a sputum sample for rapid GeneXpert MTB/RIF (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, California, USA) testing. TB diagnosis was confirmed either by a positive GeneXpert result or clinician assessment based on clinical and radiologic findings. Individuals diagnosed with TB were subsequently referred to their local health facility for treatment. Details of TB Movil logistics and implementation have been described previously7,28,29.

Following an initial evaluation of TB Movil’s first year, 29,943 individuals were screened in Carabayllo and 173 were diagnosed with TB, resulting in a case rate of 496 cases per 100,000 population—four times higher than previously estimated28. Additionally, prior analysis indicated that neighborhood-level socioeconomic factors were more predictive of TB screening yields than historic case notification rates28.

Data sources

This study utilizes primary data sources:

-

1)

TB Movil screening data:

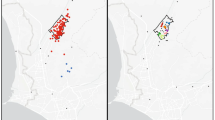

Data from the first year of TB Movil implementation (February 2019–February 2020) were used, referred to as ‘TB Movil data.’ During this period, two mobile screening units operated in 95 locations across 74 neighborhoods in Carabayllo, with each location visited for one to eight days (Fig. 1). A map of the screening sites was overlaid onto neighborhood-level maps to assign each site a neighborhood ID.

Individual-level data included patient characteristics (age, sex, TB history, and residential neighborhood), screening and diagnosis details (X-ray result, TB test type and results, and symptoms), and screening location information (neighborhood ID and site type, such as health facility, markets, or transport terminals). These data were aggregated by screening site and neighborhood for analysis.

Map of study area in Lima, Peru and distribution of mobile screening locations. Panel a: Lima Peru, with the Carabayllo district highlighted in blue, and the 74 screening neighborhoods visited by TB Movil from 2019–2020 (study area) within Carabayllo outlined in black. Panel b: zoomed-in view of the 74 screening neighborhoods (black outlines) and the 95 unique TB Movil screening locations (red dots). Maps were generated using the tmap package in R version 4.5.1 (https://cran.r-project.org).

-

2)

Historic case notification rates:

Data on notified TB patients and their residential locations from January 2013 to December 2017 were collected from nine contiguous health facilities in Carabayllo9—referred to as ‘historic TB rate data.’ Residential locations were geocoded, overlaid onto neighborhood maps, and the number of TB patients per neighborhood was calculated.

-

3)

Census data:

The 2017 Peruvian census data for Carabayllo was obtained from the National Institute of Statistics and Information in Peru26—further referred to as ‘census data.’ Conducted every ten years, this was the most recent census available, providing demographic figures, socioeconomic indicators (e.g., ownership of items such as computers, cars, or microwaves), educational status, and household crowding. Census data were aggregated by block-level census tract, while the TB Movil data and historic TB rate data were aggregated by neighborhood.

Since the census data were aggregated by block, whereas the TB Movil data and historic TB rate data were aggregated by neighborhood, we processed the census data to match the neighborhood boundaries to combine these three datasets. Since blocks are substantially smaller than neighborhoods and could cross boundaries into more than one neighborhood, we calculated the proportion, by area, of each block-level census tract that fell into each neighborhood, allowing for a weighted sum of relevant population measures to derive neighborhood-level census characteristics. Using the historic TB rate data, we calculated annual average case notification rates for each neighborhood from 2013 to 2017, using neighborhood-level census population estimates as the denominator. Age- and sex-stratified case notification rates were also calculated for each neighborhood.

Model development

We developed a simulation model to estimate the TB screening yields obtained from sending mobile screening units to sites throughout Carabayllo. This model was designed with parameters based on the TB Movil data. This was achieved by first modelling a neighborhood-level TB case rate from TB Movil data and then incorporating additional parameters to capture the movement patterns of residents who attended TB Movil in a different neighborhood than their home residence. We note that this model was developed to reflect observations from the mobile screening program only, and does not incorporate observations of other TB diagnoses from other venues in this area. We used this model to compare the effectiveness of four different mobile unit placement strategies by simulating screening yields obtained from each strategy over a three-year period. Detailed methodology is included below, with additional implementation details included in Appendix A. Table 1 summarizes parameter values used in the simulation model.

-

1)

Modeling neighborhood-level TB case rates from TB Movil.

Markov chain states

We employed Markov Chains to model the TB case rates from the TB Movil screening program in each of the 74 neighborhoods in Carabayllo. Each neighborhood-level Markov Chain included five possible states to represent the neighborhood residents: State 1: TB positive and eligible for mobile screening (TB+, status unknown); State 2: TB negative and eligible for mobile screening (TB-, status unknown); State 3: screened at a mobile unit and diagnosed with TB (TB+, status observed); State 4: screened at a mobile unit and not diagnosed with TB (TB-, status observed), and State 5: no longer eligible for screening (e.g. already screened TB + previously, or individuals assumed to never seek screening). See Fig. 2 for a graphical representation of this model.

Five-state Markov chain model of tuberculosis states, applied at the neighborhood level. The states represent (1) TB positive (TB+) and eligible for mobile screening (TB + unobserved), (2) TB negative (TB-) and eligible for mobile screening (TB- unobserved), (3) screened at a mobile unit and diagnosed with TB (TB + observed), (4) screening at a mobile unit and not diagnosed with TB (TB- observed), and (5) those no longer considered eligible for screening at the mobile units. Individuals in the community develop TB disease at a rate of \(\gamma\); when the screening van is available (at = 1), TB + individuals are screened at a rate of s+, and TB negative individuals at a rate of s-. d represents the rate at which TB + individuals transition directly into State 5 and are no longer expected to present at a screening location. See Table 1 for a descriptive list of these model parameters along with their estimated values.

Model assumptions

Transition rates

Individuals transition from State 2 (TB-) to State 1 (TB+) at a rate of \(\:\gamma\:,\) estimated per neighborhood using a least squares process to minimize the difference between the Markov chain predictions and observed screening yields from the TB Movil data. Individuals in the same neighborhood share a common transition matrix. The optimization procedure is detailed in Appendix B, with calculated \(\:\gamma\:\) values summarized in Fig. 3; Table 1. Of the 74 neighborhoods, there were 40 in which TB cases were diagnosed and \(\:\gamma\:\) could be estimated. The remaining 34 neighborhoods that had no TB cases identified are given \(\:\gamma\:\) = 0.

Estimated neighborhood-level rate of development of TB disease, \(\gamma\). \(\gamma\) was estimated for each of the 74 included neighborhoods as a weekly rate of the population transitioning from the TB negative to TB positive states (i.e. development of TB disease). Of these neighborhoods, 34 had no TB cases identified and therefore were estimated as \(\gamma =0.\) This figure shows \(\gamma\) for the remaining 40 out of 74 neighborhoods ranked from low to high, with the first 34 neighborhoods where \(\gamma =0\) being omitted.

Mobile screening unit availability

The availability of a mobile screening unit in a neighborhood for week \(\:t\) is indicated by \(\:{a}_{t}\), where \(\:{a}_{t}\:=1\) if available and 0 if not. Individuals are only observed in weeks when a mobile unit is present (\(\:{a}_{t}\:=1\)). The Markov Chain used to model individuals in a neighborhood is a Conditional Markov Chain with transition matrix conditioned on \(\:{a}_{t}\).

Attendance rates

In weeks when the unit is present, a proportion of eligible TB+ (State 1) and TB- (State 2) individuals will attend the screening. The weekly attendance rate for TB- individuals (\(\:{s}^{-}\)) is set at \(\:0.25\%\), derived from an overall population attendance rate of \(\:13\%\) in Carabayllo during TB Movil’s operation (2019–2020, i.e. one year). The attendance rate for TB + individuals (\(\:{s}^{+}\)) is conservatively estimated at \(\:0.5\%\), as these individuals are more likely to seek screening due to the presence of symptoms or known contact with someone with TB. The proportion of TB + and TB- individuals attending screenings is assumed to be constant.

Assumptions on TB status and screening

It is assumed that individuals in States 1 and 2 had not been tested for TB recently elsewhere and therefore did not already know their TB status before being screened by TB Movil. Individuals in State 1 (TB+, unobserved) are assumed to never self-cure during the three-year study simulation period. A proportion of individuals in State 1 are assumed to never attend screening, moving directly to State 5 at a rate of d. This assumption is based on the observation that a substantial proportion of TB cases globally are missed by health systems annually1. As there was no local prevalence survey available for reference, we based our estimate of d on the 2022 WHO estimate that only 57% of individuals with TB in Peru were diagnosed23, and therefore set d to 43%.

Simulation duration and treatment

We use a simulation duration of three years. Individuals in State 3 are assumed to be informed of their TB status, linked to treatment, and do not return for subsequent screenings. Individuals in State 4 remain eligible for future screenings.

Diagnosis accuracy

It is assumed that TB diagnosis is performed with 100% accuracy. Although real-world diagnosis may not achieve this level of accuracy, the TB Movil program utilized a combination of sensitive diagnostic tests (GeneXpert), X-ray results, symptoms, and clinical examination to enhance diagnostic accuracy. This assumption is made within the context of the modeling without investigating the relative performance of diagnostics.

-

2)

Incorporating an inter-community effect.

Attendees of TB Movil were frequently screened in neighborhoods different from their home residences. Consequently, the screening outcomes at each of the 95 sites do not solely depend on the TB incidence of the neighborhood where the screening takes place. To address this, we implemented a sampling procedure to simulate the sites accommodating attendees from multiple neighborhoods.

For each week of the simulation, we consider a fixed number of potential attendees, A, from the 74 neighborhoods in Carabayllo. The residential origins of these attendees were assigned using weighted sampling based on a probability distribution, \(\:\pi\:\). Parameters A and \(\:\pi\:\) were calculated for each screening site to reflect actual attendance rates and the residential origins of attendees in the existing TB Movil data. Each of the 95 screening sites could accommodate up to 200 attendees per session (day). Detailed derivations and visualizations of \(\:A\) and \(\:\pi\:\) can be found in Appendix C. Figure S1 depicts the distribution of the number of potential attendees (\(\:A\)) across all 95 sites, as well as a heat map showing the probability distribution \(\:\pi\:\) of the residential origins of attendees at each site.

After sampling the A potential attendees along with their neighborhood of origin, each individual’s decision to attend the screening and the corresponding outcome were determined using weighted sampled based on the neighborhood-level Markov Chains described earlier.

Model validation

Our simulation model was designed to replicate the screening outcomes observed in the 2019–2020 TB Movil data. To evaluate overall model performance, we conducted 1,000 simulations, maintaining the same site placements, order, and timing as in the original TB Movil operation and compared the simulated screening yields to the actual observations from TB Movil.

Mobile unit allocation strategies

We employed four strategies for placing mobile TB screening units throughout the Carabayllo community:

Strategy 1—Random: Mobile units are assigned to screening sites at random using uniform sampling.

Strategy 2—Historic Rates: Screening sites in neighborhoods with historically higher case notification rates are prioritized. This strategy uses weighted sampling based on the historic TB rate data and serves as the baseline comparator, reflecting common practice.

Strategy 3—Exponential-weight algorithm for Exploration and Exploitation (Exp3)24: Exp3 adapts to fluctuations in TB incidence at screening sites. The algorithm maintains weights for each site, increasing the likelihood of selecting high-yield sites based on observed outcomes. If a decline in TB incidence is noted, Exp3 reduces the site’s weight, reallocating resources to potentially higher-yield areas. This allows for responsive adaptation as ongoing interventions may lower new TB screening yields.

Strategy 4—Linear Upper Confidence Bound (LinUCB)25: LinUCB is a “contextual” bandit algorithm: it utilizes predictive indicators associated with TB incidence (the “context”) to inform placement decisions. A prior analysis of the TB Movil data revealed that neighborhood-level socioeconomic indicators obtained from the census data were associated with TB screening yield28. For the indicators we selected to use with LinUCB, the full selection process and list of indicators are outlined in Appendix E. Briefly, we used binomial regression modeling to assess an initial list of 65 neighborhood-level factors, including many of the same indicators from the census identified previously, in relation to the TB Movil screening data. Variables were narrowed down based on an initial statistical significance threshold of p = 0.25 and through visual inspection of collinearity between remaining variables. The final indicators identified included neighborhood population size, the proportion of residents aged 15–44, historic TB case notification rates, and the percentage of households owning blenders (i.e. an indicator of socioeconomic status, representing disposable income28. LinUCB refines its predictions continuously as more data are collected, directing units to predicted high-risk areas.

Strategies 1 and 2 are non-adaptive; they do not adjust based on program outcomes. Strategies 3 and 4 are adaptive, adjusting unit placement based on data gathered during the screening program. Detailed algorithmic implementations can be found in Appendices D, F, and H.

Screening yield simulation

We conducted 1,000 simulations of four mobile unit allocation strategies, described earlier, using between one to four available units assigned to one of 95 possible screening sites each week for a duration of seven days over a three-year study period. To summarize the results, we calculated the cumulative number of individuals screened and diagnosed with TB for each strategy, along with their standard deviations. The primary outcome of interest was the number of individuals needed to screen to identify one individual with TB disease, referred to as screening efficiency. Additionally, we computed the average total number of individuals screened and diagnosed by each strategy. We compared the performance of the two MAB algorithms by assessing the time it took for each to exceed the Historic Rates strategy in screening efficiency and the point at which each algorithm achieved peak performance relative to the Historic Rates strategy.

Sensitivity analysis

To test the sensitivity of our results, we altered the values of two model parameters: \({s^+}\)and d (the attendance rate of TB+ individuals and the proportion who never attend screening, respectively). For s+, we assessed a range of values in relation to our set rate for s- of 0.25%. We assume that s+ will be no smaller than s- and tested \({s^+}=r{s^ - }\) for \(r~ \in \left\{ {1,~2,3,4,5} \right\}\). For d, we used the 2022 WHO estimate from Peru of d = 43%23 as a starting point and tested a 10% and 20% reduction in this rate (d = 33% or 23%), assuming the 2022 estimate may be an overestimate given both the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic on health systems and the fact that TB Movil should reduce barriers to TB screening. With this range of values for these parameters, we recalculated the remaining model parameters. We then assessed how well the model generated screening yields compared to the observations from the TB Movil data, using the same method described in the “Model validation” section. Finally, we conducted screening yield simulations (per earlier section) to evaluate screening efficiency across the different mobile unit placement strategies. Detailed parameter ranges and results are provided in Appendix G.

Ethics

This study was conducted in accordance with the U.S. Health and Human Services regulations for the protection of human subjects (HHS 45CFR 46). The TB Movil screening intervention and evaluation were approved by the ethics committee of the Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia (protocol 18004). A waiver of informed consent for screening procedures and data collection was granted by the Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia ethics committee on the basis that procedures posed minimal risk to participants and that informed consent could not feasibly be administered in the context of a high-volume community screening program. This study was also given a non-human subjects research determination from the Boston University Medical Campus Institutional Review Board.

Results

We first assessed the results of our model validation, in which we compared the output from simulated screenings that followed the exact site visit strategy of the true TB Movil screening to the real-world observed output. The results from this model validation comparison are summarized in Fig. 4. Approximately 66% of the real-world observations (red dots) fell within one standard deviation of the mean screening yields from the simulations (black lines), while 96% fell within two standard deviations of the simulated mean.

Results of model validation exercise. Results of running 1,000 simulations allocating one mobile screening unit to the same locations in the same order as the actual TB Movil screening that took place between 2019–2020, in comparison to the actual screening results. Blue dots represent the simulated TB screening yields (i.e. proportion diagnosed TB + of those screened), black diamonds represent the mean simulated yield, black lines represent one standard deviation of the mean yield, and red dots represent the observed TB yields. 67.9% of the observed data fell within one standard deviation around the simulated mean, and 96.2% of the observed data fell within two standard deviations.

Results from the 1,000 simulations using one to four vans guided by the four allocation strategies are presented in Fig. 5; Tables 2 and 3. In Fig. 5, the primary outcome is the number of individuals needed to screen to identify one individual with TB, with lower values indicating better detection efficiency. The strategies ranked in effectiveness from highest to lowest are: LinUCB, Exp3, Historic Rates, and Random. Notably, the Historic Rates strategy consistently outperformed the Random strategy, although their confidence bounds overlapped. Among the two MAB algorithms, LinUCB demonstrated a significant advantage over the non-contextual Exp3. On average, with two screening units, the number of individuals needed to screen to detect one individual with TB was 152 (standard deviation, SD: 11) for Random, 143 (SD: 11) for Historic Rates, 112 (SD: 10) for Exp3, and 79 (SD: 12) for LinUCB.

Comparative simulation model performance for one to four mobile screening units. Results of running 1,000 simulations of each of the four van allocation strategies using one to four vans over the course of three years. Lines represent the cumulative average number of individuals needed to screen to identify one person with tuberculosis. Shaded area represents one standard deviation.

As the number of screening units increased, detection efficiency for Random and Historic Rates remained relatively stable, while both Exp3 and LinUCB showed significant improvements. This is evident from the widening performance gaps and the earlier weeks in which they surpassed the other methods. For instance, Exp3 began outperforming Historic Rates at 106 weeks with one unit, but this decreased to 25 weeks with four units (see Table 2). The peak performance of Exp3 over Historic Rates also improved with more units, achieving a maximum of 32–33% improvement in the weekly screening efficiency with three or four units, and 22% with two units. LinUCB quickly outperformed all strategies within six to twelve weeks, demonstrating dramatic improvement in the first year. It achieved a maximum weekly screening efficiency improvement of 49% with three units.

Across all unit specifications, screening efficiency for Random and Historic Rates initially improved but then gradually declined within about a year. LinUCB showed a slight decline in efficiency starting around the second year with one or two units, but this was minimal, especially with three or four units. The Exp3 algorithm exhibited a decline only with four units, beginning around the two-year mark.

In sensitivity analyses in which we altered the parameters s + and d, the overall pattern of the model results remained unchanged across all specifications, with model performance declining in order from LinUCB, Exp3, Historic Rates, and Random (see Appendix G, including Figures S2 and S3 showing results for the 2-unit specification). Across these analyses, the peak performance of LinUCB over the Historic Rates strategy ranged from 42 to 54% with two screening units, demonstrating the durability of these findings across the spectrum of assumptions about screening attendance among the TB + group and rate of missed cases.

Discussion

Our analysis demonstrated that using a MAB framework to direct the placement of mobile screening units may improve TB screening yields over routinely used non-adaptive strategies such as targeting areas previously observed to have high case rates. Through simulations, we found that two MAB algorithms, LinUCB and Exp3, consistently outperformed placing mobile units either randomly or based on historic case rates over a three-year period. Our simulations yielded three key findings regarding the screening efficiency of the four mobile screening unit allocation strategies tested: consistent ranking in detection efficiency, varying responses to the number of screening units, and diverging trends between adaptive and non-adaptive strategies. Each finding underscores the practical implications of using adaptive strategies in TB screening efforts.

Consistent ranking in detection efficiency: The results demonstrated that the MAB adaptive strategies (Exp3 and LinUCB) consistently outperformed non-adaptive approaches (Random and Historic Rates) in terms of screening efficiency over the three-year simulation. Regardless of the number of screening units deployed, the ranking of strategies from most to least effective was: LinUCB, Exp3, Historic Rates, and Random. LinUCB, in particular, rapidly surpassed Exp3, highlighting the advantages of incorporating contextual features, such as local demographics and socioeconomic factors, into the allocation strategy. These findings emphasize the robustness of adaptive strategies in optimizing TB screening efforts and the critical role that contextual factors play in enhancing decision-making.

Response to number of screening units: Increasing the number of mobile units significantly improved the screening efficiency for adaptive strategies while having minimal impact on non-adaptive strategies. Adaptive strategies can dynamically adjust their mobile unit placements based on ongoing data, allowing them to efficiently target high-yield screening sites. This was particularly evident when increasing the number of units from one to two, in which Exp3 reduced the time it took to outperform non-adaptive strategies by almost 50% and LinUCB achieved close to its overall peak performance compared to non-adaptive strategies, with more incremental gains from adding additional units (Table 2). This result is encouraging given that two mobile units aligns with how TB Movil was typically operated. With two units, it took Exp3 56 weeks outperform the non-adaptive strategies and took LinUCB 11 weeks, which was further reduced to 25 weeks for Exp3 and 6 weeks for LinUCB with four units.

Screening efficiency over time: Over the three-year simulation, non-adaptive strategies exhibited a consistent increase in the number of individuals needing screening per TB case detected, regardless of the number of mobile screening units used. In contrast, adaptive strategies showed no such trend; in most scenarios, the number needed to screen either gradually declined, plateaued, or increased slightly in the final year. This indicates that adaptive strategies maintained greater screening efficiency by continuously identifying and targeting high-burden areas. By contrast, non-adaptive strategies, which lacked the ability to incorporate new information, often revisited neighborhoods with lower TB prevalence, diminishing their effectiveness. Adaptive strategies not only improved screening efficiency but also potentially contributed to mitigating TB spread, enhancing community health outcomes.

The results of our study are largely consistent with prior assessments of adaptive strategies for targeting infectious disease screenings, generally demonstrating that adaptive strategies may improve screening yields over non-adaptive strategies. There have been few prior analyses of using spatially targeted strategies for directing community-based TB screening, and only one prior analysis that assessed an adaptive spatial strategy in the context of TB screening10. Similar to our analysis, this prior adaptive modeling study by de Villiers et al. conducted a simulation of an adaptive strategy (Thompson sampling) to target digital chest X-ray screening for TB in communities with varying TB burden in South Africa and Zambia in comparison to random screening placement or placement based on past case detection rates using four screening units. The adaptive strategy demonstrated substantial improvements in case detection compared to both random sampling or targeting on past case rates, with 86% and 63% improvement in the case detection rate, respectively20. In our study, we found similar improvement in case detections, with LinUCB and Exp3 increasing case detections by 79% and 25% over random placement, respectively, using two screening units, and 59% and 43% using four screening units.

Other studies have examined spatially-targeted TB screening without adaptive methods. Two studies conducted in the United States, a low-burden setting, have demonstrated that geographically targeting screening efforts can improve efficiency in detecting cases30,31. A modeling study of a spatially-targeted screening approach in Ethiopia, a high-burden setting, also demonstrated that the spatial approach could significantly improve case detection over an untargeted approach11. One other modeling study has been conducted examining spatially-targeted TB screening in Lima, using data from 2009 to 2012 from a district neighboring Carabayllo12. This individual-level modeling study demonstrated that targeted screening of household contacts was relatively efficient for detecting cases and that adding a spatially targeted community-based screening approach only incrementally improved results, but that neither method demonstrated substantial improvements in the overall TB incidence rate in the district over the course of 5 years. However, this study assessed a highly targeted screening using limited resources, in comparison to TB Movil and other studies that examined a mass screening context. Additionally, there is currently a prospective trial taking place in Pakistan, a high-burden setting, using a step-wedge design to conduct active case finding, in which treatment communities will have screening targeted based on MATCH-AI software to determine “hotspots”. This software uses a Bayesian modelling approach in an adaptive manner to predict TB prevalence and incorporates contextual factors (similar to LinUCB)32. This study will provide critical insights into the real-world application and utility of such adaptive approaches.

As highlighted by the trial currently taking place in Pakistan, we note that LinUCB is able to be adapted to other settings. While the variables that we selected for our model as contextual features may not be available or may not be the most appropriate for describing the TB dynamics elsewhere, inputs to LinUCB will be driven by availability of contextual data and local context and can be selected by using simple relatively simple regression analyses as we have employed in this study. In settings where contextual features may not be available, use of a non-contextual algorithm, such as Exp3 in our study, may be more appropriate. Even without the contextual features, Exp3 demonstrated superior performance over non-adaptive strategies over the full course of the simulation. Though it took longer than LinUCB to achieve these results, the performance of Exp3 nonetheless demonstrated the utility of these models in other high-burden settings that may have limited socioeconomic data available, particularly in an ongoing or long-term screening context.

In using data-driven algorithms for informing screening locations, it is important to consider the potential for structural biases that can become built in to these models. For example, in our context, the MABs can only recommend locations to screen at that are available to the model, which are generally provided by programmatic staff. As we discussed in the context of non-adaptive strategies, sites may be preferentially selected where a high rate of TB had been observed previously. Of course, some areas may have had few TB cases diagnosed previously due to a systematic lack of healthcare access—if such areas are not incorporated into the list of potential sites to visit, the adaptive strategies will not improve screening of those communities and could have the unintended consequence of further entrenching disparities. Screening interventions employing MAB algorithms should consider setting explicit strategies and incorporating regular reviews of program data to ensure equity in the distribution of resources.

Strengths and limitations

This study uniquely explored the application of adaptive algorithms to optimize mobile TB screening interventions. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to incorporate socio-economic factors alongside spatial information of specific screening site locations. Our model is based on historical case data from Carabayllo, accounting for variability in attendance across screening sites. Furthermore, the small-scale model developed here potentially offers a foundation for future analyses and strategic active screening program simulations within Carabayllo and can be translated to other settings.

However, this study also has limitations. To determine the neighborhood-level case rates and incorporate indicators of socioeconomic status into our models, we relied on data from the 2017 census, as the census is conducted decennially. Therefore, the population denominators may not accurately reflect the underlying population in 2019–2020, when our study data was collected. The model we developed may not fully capture the complexities of TB transmission. There was no underlying data available to estimate some of the parameters included in our model of TB dynamics, including s + and d (the rate of screening attendance and proportion who will never seeking screening among TB + individuals, respectively). For both of these parameters, we fit a range of plausible estimates in a sensitivity analysis and found no substantive change to our results interpretation.

In all analyses, we assumed that individuals with TB were at least as likely as those without TB to attend mobile screening units, given higher likelihood of symptoms or exposure. However, the strength of this assumption is uncertain, as stigma or other factors may reduce attendance. We also modeled a constant screening attendance rate among TB-negative individuals, which does not capture neighborhood-level heterogeneity or unmeasured influences33. Given these data limitations, we chose a simpler model to compare performance rather than introduce additional, potentially unsupported assumptions.

The mobile unit screening sites included in our simulation were based on previous screening locations, which might not represent all potential high-yield areas. Moreover, the model’s structure relies on a mixture of Markov chains, which may not be the most appropriate for describing the long-term evolution of TB in a community. Although the model was well-calibrated, its long-term predictive power remains uncertain, though initial results with adaptive strategies were promising. Despite these limitations to our model of the neighborhood-level TB dynamics, we stress that the primary objective of this study was to assess the effectiveness of different mobile unit allocation strategies given underlying dynamic changes in TB rates, rather than to perfectly model the underlying TB prevalence. Importantly, our algorithms do not depend on this model as they are agnostic to the underlying dynamics of TB.

Conclusions

Adaptive algorithms like LinUCB and Exp3 could substantially improve TB detection efficiency in resource-limited settings by prioritizing high-yield screening sites and adapting to changing epidemiology. Their ability to rapidly process data enables responsive, evidence-based decision-making, which is critical for TB control. Implementing these strategies could transform screening practices, particularly in high-burden areas, by improving diagnosis of patients often missed by traditional systems and ultimately reducing transmission. Adaptive algorithms can also scale efficiently in data-sparse settings by leveraging routine programmatic data and adapting as outcomes accrue. Yet, without explicit attention to equity, they risk reinforcing disparities, underscoring the need to integrate bias mitigation and equity-focused objectives alongside efficiency. The next step is to move beyond simulations and rigorously evaluate these methods in real-world screening programs—both for TB and for other infectious diseases like HIV—to establish their feasibility, efficiency, and impact.

Data availability

Data are available upon reasonable request. Please contact the corresponding author for a data request form.

References

Global Tuberculosis Report 2024. (World Health Organization, (2024).

McQuaid, C. F., Vassall, A., Cohen, T., Fiekert, K. & White, R. G. The impact of COVID-19 on TB: a review of the data. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 25, 436–446 (2021).

Pai, M., Kasaeva, T. & Swaminathan, S. Covid-19’s devastating effect on tuberculosis care — a path to recovery. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 1490–1493 (2022).

Migliori, G. B. et al. Worldwide effects of coronavirus disease pandemic on tuberculosis Services, January–April 2020 - 26, number 11—November 2020 - Emerging infectious diseases journal - CDC. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2611.203163 (2020).

Yuen, C. M. et al. Turning off the tap: stopping tuberculosis transmission through active case-finding and prompt effective treatment. Lancet (Lond. Engl.) 386, 2334 (2015).

Hoog, A. H. et al. Screening strategies for tuberculosis prevalence surveys: the value of chest radiography and symptoms. PLOS ONE. 7, e38691 (2012).

Yuen, C. M. et al. Identifying barriers and facilitators to implementation of community-based tuberculosis active case finding with mobile X-ray units in Lima, peru: a RE-AIM evaluation. BMJ Open. 11, e050314 (2021).

Cobelens, F., van Kampen, S., Ochodo, E., Atun, R. & Lienhardt, C. Research on implementation of interventions in tuberculosis control in Low- and Middle-Income countries: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 9, e1001358 (2012).

Brooks, M. B. et al. Mapping local hot spots with routine tuberculosis data: a pragmatic approach to identify Spatial variability. PLOS ONE. 17, e0265826 (2022).

Cudahy, P. G. T. et al. Spatially targeted screening to reduce tuberculosis transmission in high-incidence settings. Lancet Infect. Dis. 19, e89–e95 (2019).

Shaweno, D., Trauer, J. M., Doan, T. N., Denholm, J. T. & McBryde, E. S. Geospatial clustering and modelling provide policy guidance to distribute funding for active TB case finding in Ethiopia. Epidemics 36, 100470 (2021).

Havumaki, J. et al. Spatially-targeted tuberculosis screening has limited impact beyond household contact tracing in Lima, peru: a model-based analysis. PLOS ONE. 18, e0293519 (2023).

Slivkins, A. Introduction to Multi-Armed bandits. MAL 12, 1–286 (2019).

Thompson, W. R. On the likelihood that one unknown probability exceeds another in view of the evidence of two samples. Biometrika 25, 285–294 (1933).

Aziz, M., Kaufmann, E. & Riviere, M. K. On multi-armed bandit designs for dose-finding clinical trials. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 22, 14:686–614 (2021).

Villar, S. S., Bowden, J. & Wason, J. Multi-armed bandit models for the optimal design of clinical trials: benefits and challenges. Stat. Sci. 30, 199–215 (2015).

Tewari, A. & Murphy, S. A. Mobile Health: Sensors, Analytic Methods, and Applications (eds. Rehg, J. M., Murphy, S. A. & Kumar, S.) 495–517 (Springer International Publishing, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51394-2_25.

Figueroa, C. A. et al. Adaptive learning algorithms to optimize mobile applications for behavioral health: guidelines for design decisions. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 28, 1225–1234 (2021).

Gonsalves, G. S., Crawford, F. W., Cleary, P. D., Kaplan, E. H. & Paltiel, A. D. An adaptive approach to locating mobile HIV testing services. Med. Decis. Mak. 38, 262–272 (2018).

de Villiers, A. K., Dye, C., Yaesoubi, R., Cohen, T. & Marx, F. M. Spatially targeted digital chest radiography to reduce tuberculosis in high-burden settings: a study of adaptive decision making. Epidemics 38, 100540 (2022).

Gonsalves, G. S. et al. Maximizing the efficiency of active case finding for SARS-CoV-2 using bandit algorithms. Med. Decis. Mak. 41, 970–977 (2021).

Rayo, M. F. et al. Using bandit algorithms to maximize SARS-CoV-2 Case-Finding: evaluation and feasibility study. JMIR Public. Health Surveill. 9, e39754 (2023).

Wang, Y., Yahav, I. & Padmanabhan, B. Smart testing with vaccination: a bandit algorithm for active sampling for managing COVID-19. Inform. Syst. Res. 35, 120–144 (2024).

Auer, P., Cesa-Bianchi, N., Freund, Y. & Schapire, R. E. The nonstochastic multiarmed bandit problem. SIAM J. Comput. 32, 48–77 (2002).

Varatharajah, Y. & Berry, B. A. Contextual-Bandit-based approach for informed decision-making in clinical trials. Life 12, 1277 (2022).

Insituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. INEI - REDATAM CENSOS. In Censos Nacionales 2017: XII de población, VII de vivienda y III de comunidades indígenas Lima, 2017. https://censos2017.inei.gob.pe/redatam/ (2017).

Quispe, N. et al. The fourth National anti-tuberculosis drug resistance survey in Peru. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 24, 207–213 (2020).

Brooks, M. B. et al. A role for community-level socioeconomic indicators in targeting tuberculosis screening interventions. Sci. Rep. 12, 781 (2022).

Galea, J. T. et al. A structured community engagement strategy to support uptake of TB active case-finding. Public. Health Action. 12, 18 (2022).

Goswami, N. D. et al. Geographic information System-based screening for TB, HIV, and syphilis (GIS-THIS): a Cross-Sectional study. PLOS ONE. 7, e46029 (2012).

Moonan, P. K. et al. What is the outcome of targeted tuberculosis screening based on universal genotyping and location? Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 174, 599–604 (2006).

Zaidi, S. M. A. et al. Geographical targeting of active case finding for tuberculosis in Pakistan using hotspots identified by artificial intelligence software (SPOT-TB): study protocol for a pragmatic stepped wedge cluster randomised control trial. BMJ Open. Respiratory Res. 11, e002079 (2024).

Jenkins, H. E. et al. Geographic accessibility to health facilities predicts uptake of community-based tuberculosis screening in an urban setting. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 120, 125–131 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design of this study: M.B. Brooks, A. Cutkosky, J. Zhang, L. LindeConception and design of TB Movil program: D. Puma, L. Lecca, M.C. Becerra, S. Keshavjee, M.B. BrooksData acquisition, oversight: D. Puma, A.K. Millones, K. Tintaya, J. Jimenez, L. LeccaSimulation and data analysis: J. ZhangInterpretation of findings: M.B. Brooks, A. Cutkosky, J. Zhang, L. Linde, H.E. JenkinsDrafted the first version of the manuscript: L. Linde, J. Zhang, M.B. BrooksRevised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J., Linde, L., Puma, D. et al. Adaptive bandit algorithms increase efficiency of mobile tuberculosis screening programs. Sci Rep 16, 1497 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31829-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31829-x