Abstract

Barriers can affect the movement, migratory patterns, and demographic rates of ungulates. Even in highly remote areas with relatively little development, like northwest Alaska, isolated roads can alter the movements of ungulates such as caribou (Rangifer tarandus). Here, a solitary, 80-km long industrial road connecting a large zinc and lead mine to a port affects caribou migrations. Using location and survival data from 366 GPS collared, adult female caribou representing > 850 caribou-years from 2010 to 2023, we assessed whether caribou whose fall movements were altered by the road experienced higher mortality risk compared to those whose movements were unaltered. Of the 101 caribou-years that came within 20 km of the road, 58% displayed altered movements. The survival rate of caribou whose movements were unaltered by the road was 20% higher than those caribou whose movements were altered by it, though difference was not significant (p > 0.05). Increased movements, delayed migration, and/or changes in habitat selection related to altered movements could still have energetic and demographic consequences. Caribou that crossed or circumvented the road had significantly higher survival rates (78.5% survived until calving) than caribou that did not cross or circumvent the road (i.e., it acted as an impermeable barrier and the caribou wintered north of it; 57.9%). Given our results, we posit that enhancing the permeability of roads could improve the survival of caribou in the region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Migration is a widespread adaptation that helps maximize seasonal access to forage resources and/or reduce mortality risk1,2. By facilitating access to higher-quality and more abundant forage resources while also potentially reducing predation pressure, migration has allowed many populations to increase numerically far beyond the size of resident (non-migratory) populations1. The greater the resource gradient (and relative reward), the greater the likelihood that migrations will occur1,3,4. However, for terrestrial ungulates, migrations are imperiled globally5,6,7. Habitat loss, degradation, and fragmentation are primary drivers of the declines in migrations, though changes in climate have also been implicated4,8,9. Human development, such as roads, railroads, and fences, have been identified as the greatest threat to ungulate migrations9.

The degree to which anthropogenic barriers may decrease connectivity between essential habitats for migratory species can vary, from completely impermeable to highly permeable barriers. Impermeable barriers fully disrupt connectivity between critical habitats for migratory species, resulting in functional habitat loss that can impact individual behavior, fitness, and potentially population demographics1,8,10,11,12. Semi-permeable barriers, where a degree of connectivity is maintained between critical habitats, can also impact the behavior and movement patterns of migratory ungulates. Some individuals may attempt to circumvent the barrier, adding distance to their total movements and potentially reducing the efficiency of their habitat use9,13, which could impact their energetic dynamics. In other cases, individuals attempting to cross semi-permeable barriers may be killed (e.g., vehicle collisions) or migration to critical habitats may be significantly delayed14,15,16,17. In many instances, both increased anthropogenic activity (e.g., higher traffic volumes) on roads and more dense road networks have been found to elicit stronger reactions by migratory ungulates and to increase mortality13,18,19.

Caribou (Rangifer tarandus) are the most abundant large mammal in the circumpolar north20,21. They undertake the longest terrestrial migrations on the planet due to the extremely seasonal environment they inhabit22. During fall, migratory movements appear to be triggered by declining ambient temperatures and accumulating snow23. Fall migration of large continental caribou herds to their winter ranges is motivated by the pursuit of areas with greater abundance of their primary winter forage, lichens24,25,26. The abundance and migratory patterns of caribou have made them an integral part of northern cultures, including being a primary subsistence resource for remote villages in the Arctic27,28.

While the Arctic is among the least developed regions in the world, development is increasing29,30. Roads and large-scale infrastructure can affect the movements of caribou causing general avoidance, delays in crossing, altered behaviors and, in some cases, prevent caribou from reaching their wintering grounds and fragment populations16,17,19,31,32,33. The ability to move freely and widely is one of the most important adaptations caribou have for navigating a highly seasonal and low-productivity environment31,34. However, little work has been done to directly assess the effects that encountering a road may have on caribou survival.

Our goal was to assess whether caribou interactions with the DeLong Mountain Transportation System, a singular, isolated industrial road in northwest Alaska, were related to subsequent survival outcomes. The road may be lengthened and its lifespan extended if nearby mineral deposits are mined35. We predicted that the permeability of the road would be related to survival rate up to calving (i.e., through May 31), such that if caribou were able to cross or circumvent the road, their mortality risk would not be significantly impacted, regardless of whether their movements were altered. However, for caribou that did not cross or circumvent the road (i.e., it acted as an impermeable barrier preventing them from migrating further south), we predicted that survival would be lower.

Methods

Study area

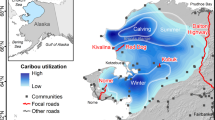

Western Arctic Herd (WAH) caribou range over about 363,000 km2 of northwest Alaska36. Barren-ground caribou populations, like the WAH, exhibit large, natural fluctuations in abundance37,38. The WAH has ranged from a low of approximately 75,000 in 1976 to a high of 490,000 in 2003 when it was one of the largest herds on the planet36. Since then, the herd has declined to 152,000 caribou in 2023 (A. Hansen, Alaska Department of Fish and Game, unpublished data). Fall migration routes for the WAH vary within and among years, but, on average, about 10% of the herd uses the far western side of their range during the southward fall migration to their various winter ranges [33,39; but see Results]. This route often takes WAH caribou in proximity of the Red Dog Mine (68.1o N, 162.9o W) in the DeLong Mountains, one of the world’s largest open-pit zinc and lead mines39. The mine is connected to its port site on the coast of the Chukchi Sea by an approximately 80 km-long road officially called the DeLong Mountain Transportation System (DMTS, Fig. 1) but known locally as the Red Dog Road (henceforth ‘the road’). Construction of the road started in 1987 and became operational in 1989. It remains unconnected to any other road system. The area adjacent to the road is dominated by tussock tundra (Eriophorum spp.) with hills supporting shrubs (Salix spp., Betula nana) that transition into alpine habitat. Snow covers much of the region from October through May, except in wind swept areas40,41. Fall temperatures often drop below freezing but can reach 10o C. During the winter months, temperatures can drop below − 40o C.

Map of the study area in northwest Alaska. The solid black line is the DeLong Mountain Transportation System (DMTS) road connecting the Red Dog Mine to its port site. The white polygon is the range of the Western Arctic Herd. The dashed green lines are movements of adult Western Arctic Herd female caribou that successfully crossed or circumvented the road in fall and wintered to the southeast of it. The solid orange lines are movements of adult female caribou that did not cross or circumvent the road and wintered northwest of it. Movements are from September 1 – November 30, 2010–2023. Map created using ArcGIS Pro 3.4 (ESRI, Redlands, CA, USA, https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro/overview).

Caribou location and survival data

From 2009 to 2019, adult female caribou were hand captured and instrumented with GPS collars (Telonics, Mesa, AZ, USA) as they swam across the Kobuk River during their fall migration. From 2019 to 2023, caribou were captured via aerial net gunning during spring due to changes in migration patterns and timing33. In total, 419 caribou were captured. WAH caribou have low fidelity to wintering areas but high fidelity to the calving grounds; thus, newly collared animals become representative of the herd just prior to calving42,43. All capture protocols were authorized by the State of Alaska Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (permits 2012-031R, 0040-2017-40, and 0040-2019-23). We investigated data from all collared caribou that came within 20 km of the road [sensu 44] during fall (September 1 – November 30) each year (2010–2023). GPS data were standardized to approximately 8-hour relocation intervals44. We only analyzed fall movements as the sample size of caribou encountering the road was the greatest during this season and most (~ 60%) WAH caribou migrate south during fall33,44. Caribou mortalities were determined by the collar not moving for an extended time and biologists visiting the mortality location to collect the collar and any related information. Due to logistical and financial constraints limiting access to our very remote study area, most mortality locations were visited months after the mortality event occurred. Thus, while we know causes of caribou mortalities include predation, hunting, starvation, disease, and vehicular collisions, it was difficult or impossible to determine the ultimate cause of death. Therefore, we did not use mortality cause as a factor in our analyses.

Testing for effects of barrier permeability on mortality risk

The Barrier Behavior Analysis (BaBA) is a method for classifying behaviors of animals in proximity to linear barriers45. Fullman et al.44 modified and validated the approach for WAH data to accommodate the longer time interval of caribou relocation data and the larger scale of caribou movements compared to pronghorn (Antilocapra americana) and mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus)45. Following Fullman et al.44, we defined a caribou ‘encounter’ with the road as all movements from when a caribou came within a 20-km buffer of the road (the validated buffer distance) until it exited the buffer. The BaBA classified within-buffer movement into one of five behaviors by comparing movement statistics (e.g., straightness of movement, movement heading) within the buffer to fall migration movements outside of the buffer44. Two behaviors, ‘normal’ and ‘quick cross’, were considered unaltered, reflecting unhindered behavior (e.g., movements indistinguishable from caribou movements outside the road buffer)44. Movements classified as altered included: ‘back-and-forth’ (where a caribou changed direction repeatedly within the road buffer, resulting in more circuitous movement than average for the season and use of a constrained area on one side of the road), ‘bounce’ (where a caribou approached and then reversed direction away from the road), and ‘trace’ (where a caribou paralleled the road without crossing)44. Detailed descriptions of parameters underlying each movement behavior along with a classification flowchart are contained in Supplementary Information 1 of44. Code to run the modified BaBA method is available at https://github.com/tfullman/BaBA. For caribou with multiple road encounters in a given year, we combined responses into a single indication of altered or unaltered behavior for that caribou-year (unique individual caribou, year combinations), with any observations of altered movement resulting in a classification of ‘altered’ for the caribou-year.

We analyzed the influence of the road on caribou survival (using each caribou-year as the sampling unit) in two ways. We assessed whether (1) altered movement behavior and (2) the effect of barrier impermeability on wintering area selection were associated with individual mortality from buffer encounter date until May 31 (the start of calving). For our first analysis, we compared the mortality risk of caribou exhibiting altered movements at any point during the fall to those whose movements were unaltered. For our second analysis assessing the effects of barrier permeability on mortality risk, we assigned each caribou that entered the buffer during fall of each year a binary indicator of (1) did not cross or circumvent the road and wintered northwest of it, or (2) crossed or circumvented the road and wintered southeast of the road (Fig. 1). These binary classes were not dependent on whether the caribou’s movements were altered by the road. We then modeled mortality risk as a function of whether the caribou crossed/circumvented the road or not (i.e., if they wintered northwest or southeast of the road). For all survival analyses, we used staggered entry Cox proportional hazards models46 fitted with the ‘survival’ package47 in R48. We estimated survival rates and hazard ratios from when the individual first encountered the buffer through the approximate start of calving (May 31)49. All of our analyses and results account for the proportion of the herd using this section of the range.

Estimating overall mortality associated with road impermeability

We were interested in estimating how many additional caribou might have died (the surplus mortality, \(\:{M}_{s}\)) due to failing to cross or circumvent the road to winter southeast of it. \(\:{M}_{s}\) was calculated using the following equation:

Here, \(\:{N}_{t}\) is the total number of caribou (250,000 caribou, the average herd size calculated from the starting year [2009; 348,000 caribou] and the ending year [2023; 152,000 caribou]). The proportion of caribou-years that encountered the road but did not cross or circumvent it and wintered northwest of it, \(\:{p}_{a}\), was calculated as \(\:{p}_{a}=\:{n}_{a}/{n}_{c}\), where \(\:{n}_{a}\) represents the observed number of collared caribou-years that did not cross or circumvent the road and \(\:{n}_{c}\) represents the total number of collared caribou-years. \(\:{p}_{a}\) was multiplied by the difference in the mortality rate of caribou-years that encountered but wintered northwest of it, \(\:{m}_{a}\) and the mortality of rate of caribou-years that crossed or circumvented the road and wintered southeast, \(\:{m}_{0}\).

There was uncertainty in the quantities used to estimate surplus mortality, primarily from the probabilities (\(\:{p}_{a}\), \(\:{m}_{0}\) and \(\:{m}_{a}\)). To account for this, we sampled from binomial distributions with the corresponding estimated probabilities and total sample sizes 10,000 times to obtain 95% confidence intervals for each of these probabilities.

To obtain a confidence interval around \(\:{M}_{s}\), we followed a three-stage sampling process: first, we randomly sampled the number of caribou-years that encountered the road \(\:\left({N}_{r}\right)\) from a binomial distribution with probability \(\:{p}_{r}\) and population size \(\:{N}_{t}\). Here, \(\:{N}_{r}={p}_{r}{N}_{t}\) and \(\:{p}_{r}=\:{n}_{r}/{n}_{c}\), with nr as the number of caribou-years that encountered the road. Second, for each random sample, we allocated how many crossed or did not cross the road by drawing from another binomial distribution with probability of not crossing \(\:{p}_{a}/{p}_{r}\) and sample size \(\:{N}_{r}\). Third, we randomly sampled how many of each of these caribou-years were expected to die based on the respective probabilities of death, \(\:{m}_{a}\) and \(\:{m}_{0}\). We reported the 0.025 and 0.975 quantiles of the 10,000 simulations as the 95% confidence intervals. Note that our surplus mortality estimate is based solely on adult female data and assumes comparable mortality risk for adult males and juveniles. This is likely a conservative estimate as adult males and juveniles typically have lower survival rates than adult females50,51,52,53.

We used the mortality rate of the caribou that crossed or circumvented the road as the baseline of comparison to those that did not cross in our estimate of surplus mortality. An alternative baseline could have been all the caribou that did not enter the road buffer. However, these caribou did not encounter the road and used a wide array of wintering areas across the herd’s range33,42, raising questions about comparability. Thus, we believe using the mortality of the caribou that crossed or circumvented the road was the most robust baseline. Ultimately, the mortality rate of those caribou that crossed or circumvented the road was nearly identical to caribou that did not encounter the road (see Results below), and so the choice of baseline would not meaningfully alter the estimate of surplus mortality.

Results

Altered movements

A total of 82 out of 366 caribou (22.4%) encountered the road (i.e., entered the 20-km road buffer) in fall from 2010 to 2023. This rate of road encounter is more than twice as high as previous estimates due to methodological differences and additional years of data33,42. Some of the caribou entered the buffer in two different years (19 caribou or 23.2%) but none for more than two years (average post-collaring life expectancy was < 3.4 years)53. This resulted in 101 caribou-years of encounters out of a total of 852 caribou-years of data. Of the 101 encounters, 58.4% were classified as having altered movements based on Fullman et al.44. The altered movements were nearly equally split among trace (33.4%), bounce (33.3%), and back-and-forth (33.3%) behaviors. A greater percentage of caribou with altered movements (32.2%) died before calving as compared to those with unaltered movements (23.8%). The mortality risk for caribou whose movements were unaltered by the road was 20% lower than the risk of those caribou whose movements were altered by it (i.e., the risk was lower and so survival was greater); but this difference was not statistically significant (hazard ratio = 0.80 for unaltered caribou, p = 0.57).

Impermeability

We excluded three of the 101 caribou-years of data for our analysis of the effects of barrier impermeability on survival because they did not fall neatly into one of the binary indicators (see above) and thus the sample size was 98 for this analysis. Of these caribou, 19 (19.4%) did not cross or circumvent the road and wintered northwest of it (Table 1). Mortality of those that wintered northwest of the road was high; 8 of 19 (42.1%) died before calving (alternatively, 57.9% survived until calving). The other 79 caribou (80.6%) that entered the buffer either crossed or circumvented the road and wintered southeast of it (Table 1). Mortality was lower for these caribou; 21.5% died before calving (i.e., 78.5% survived; Table 1; Fig. 2). Mortality risk was significantly higher for animals that did not cross or circumvent the road and wintered northwest of it (i.e., the impermeable scenario) compared to those that crossed or circumvented the road and wintered southeast of it (semi-permeable scenario; Fig. 3; hazard ratio = 0.41 for caribou wintering in the southeast, p = 0.04). Mortality before calving was very similar between caribou that did not encounter the road (21.1%) and those that crossed or circumvented the road.

Outcomes for adult female Western Arctic Herd caribou that came within 20 km of the DeLong Mountain Transportation System in northwest Alaska during fall (beginning September 1), 2010–2023 (n = 98 caribou-years from 82 unique individuals). Bars show the percentage of caribou-years that survived (lighter colors) until calving (May 31) or died (darker colors) before then. Orange colors indicate individuals that did not cross or circumvent the road and wintered northwest of it, while green colors indicate individuals that either crossed or circumvented the road and wintered southeast of it. Black bars indicate +/- one standard error.

Survival rates, plotted daily, of adult female Western Arctic Herd caribou that encountered (came within 20 km of) the DeLong Mountain Transportation System in northwest Alaska, and either did not cross or circumvent it and wintered to the northwest of it (North, orange line and shading) or encountered the road but either managed to cross or circumvent it and wintered to the southeast of it (South, green line, light green shading). Shading in darker green is the area of overlapping variability for the two survival rates.

Surplus mortality estimation

Our estimate of surplus mortality (Ms) related to road impermeability was 1148 (95% C.I. = 1050–1247) caribou per year. Parameters for the surplus mortality estimation were 852 total caribou-years of data (\(\:{n}_{c}\)), 98 caribou-years in which collared adult females encountered (i.e., came within 20 km) the road (\(\:{n}_{r}\)), and 19 caribou-years in which collared adult females encountered the road but did not cross or circumvent it and wintered northwest of the road (\(\:{n}_{a}\)). The proportion of collared adult female caribou that encountered the road \(\:({p}_{r}=\:{n}_{r}/{n}_{c})\) was 0.115 (95% CI = 0.097–0.137) and the proportion of adult female caribou that encountered the road but did not cross or circumvent the road and wintered northwest of it (\(\:{p}_{a}=\:{n}_{a}/{n}_{c}\)) was 0.022 (95% CI = 0.014–0.033). Parameters used for the mortality estimates are found in Table 1.

Discussion

We found a lower survival rate for caribou for which an industrial road appeared to act as an impermeable barrier to fall migration than for those that managed to cross or circumvent the road. Specifically, the proportion of animals that died was nearly twice as high for those caribou which never made it across or around the road (42.1%) as for those caribou which did make it past the road (21.5%). Miller et al.54 predicted that altered caribou movements could lead to increased mortality risk. The mortality hazard ratio for caribou that were able to cross or circumvent the road, regardless of whether their movements were altered, was only 41% of that for caribou for which the road acted as an impermeable barrier and wintered to the northwest of it (i.e., a 59% reduction in mortality hazard for crossers). This statistically significant result confirms Miller et al.’s54 prediction of increased mortality risk associated with movements affected by human infrastructure. Notably, it was not the presence of the road that drove the association with reduced survival but that it acted as an impermeable barrier for some migratory caribou, presumably keeping those caribou from accessing higher-quality habitat or areas more conducive to survival.

Previous studies of ungulates have found that the level of impact, including mortality risk, is positively associated with the density or intensity of development13,18,19. The road in our study (the DeLong Mountain Transportation System) is not connected to any other road and is primarily used for mining operations (limited and controlled use by All Terrain Vehicles for subsistence hunting by the nearest village is permitted; data on vehicle traffic volume were not available). The road also occurs in one of the most remote, undeveloped regions in North America29. To our knowledge, this is the first study to document that the barrier impermeability of a solitary, isolated road is associated with an increased mortality risk for a migratory ungulate. Despite the relatively infrequent use of the westernmost fall migration pathway that intersects the road by the WAH (~ 10–22% of the herd annually), we estimated the absolute number of additional mortalities associated with road impermeability to be > 1100 caribou/year, on average.

More than 58% of caribou that encountered the road displayed altered movements during fall migration, which supports Miller et al.’s54 prediction that human development would alter caribou movements and previous research on the subject [e.g., 16,17,19]. However, our results did not indicate that road-associated changes in adult female caribou movements significantly increased mortality risk (p = 0.57). Despite being one of the largest studies of caribou, lack of statistical power may be an issue here. The mortality hazard risk for caribou with unaltered movements was 20% lower than those caribou with altered movements which may be a biologically meaningful difference, even if not statistically conclusive55. Given the relatively high percentage (> 58%) of caribou that displayed altered movement, the 20% difference in survival could potentially affect thousands of caribou. Even relatively small changes in demographic rates can have consequential population-level impacts. Therefore, we recommend researchers revisit the impacts of infrastructure on migratory caribou survival with longer-term studies using data across their global range. Along with critical potential demographic effects, there may be important sub-lethal impacts. Altered movements could result in increased energy expenditures, lost foraging opportunities, and/or physiological stress that could reduce body condition56,57,58. Fall is a critical period for adult female caribou as it is during this time that body condition largely determines pregnancy rates59,60. Investigating the potential impacts of altered movements on energetic dynamics, body condition, and pregnancy rates is an important topic for future research.

To conserve large populations of migratory ungulates (such as caribou in the Arctic), and the cultural, spiritual, and subsistence practices that rely upon them, it is vital that we understand the impacts of development to inform mitigation measures that reduce harmful impacts8,9,54. While we were able to document fitness-level effects of permeability of a solitary mining road, the mechanism which alters movement remains a potent avenue for future research and an important knowledge gap to fill. This information will also prove valuable in the planning and design of new development that may arise9,61. While this will benefit migratory species directly, it also will benefit humans as these species are the primary food source in many remote areas, especially the Arctic. Migratory species can also have substantial impacts on vegetation, especially those that are slow growing such as lichens, the primary winter forage of caribou1,24. Unimpeded flow of migratory species will allow them to utilize the landscape in the most efficient manner and respond to the dynamic environmental conditions they experience. Based on our results, we suggest that future migratory species management plans, including those for caribou, prioritize habitat connectivity by mitigating factors that influence barrier permeability (e.g., vehicle traffic levels, road dust, noise, visual impacts, accessibility).

Data availability

Survival data used for this analysis will be made available in the NPS’ publicly-accessible database (IRMA; https://irma.nps.gov) upon manuscript acceptance.

References

Fryxell, J. M. & Sinclair, A. R. E. Causes and consequences of migration by large herbivores. Trends Ecol. Evol. 3, 237–241 (1988).

Avgar, T., Street, G. & Fryxell, J. M. On the adaptive benefits of mammal migration. Can. J. Zool. 92, 481–490. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjz-2013-0076 (2014).

Mariani, P., Krivan, V., MacKenzie, B. R. & Mullon, C. The migration game in habitat network: the case of tuna. Theoretical Ecol. 9, 219–232 (2016).

Van Moorter, B. et al. Consequences of barriers and changing seasonality on population dynamics and harvest of migratory ungulates. Theoretical Ecol. 13, 595–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12080-020-00471-w (2020).

Berger, J. The last mile: how to sustain long-distance migration in mammals. Conserv. Biol. 18, 320–331 (2004).

Wilcove, D. S., Wikelski, M. & Going, going, gone: is animal migration disappearing? PLoS Biol. 6, 1361–1364 (2008).

Harris, G., Thirgood, S., Hopcraft, J. G. C., Cromsigt, J. P. G. M. & Berger, J. Global decline in aggregated migrations of large terrestrial mammals. Endanger. Species Res. 7, 55–76 (2009).

Ito, T. Y. et al. Fragmentation of the habitat of wild ungulates by anthropogenic barriers in Mongolia. PLoS ONE. 8, e56995. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056995 (2013).

Kauffman, M. J. et al. Mapping out a future for ungulate migrations. Science 372, 566–569. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abf0998 (2021).

Klein, D. R. Reaction of reindeer to obstructions and disturbances: experience in Scandinavia May aid in anticipating problems with caribou in Canada and Alaska. Science 173, 393–398 (1971).

Sawyer, H. et al. A framework for Understanding semi-permeable barrier effects on migratory ungulates. J. Appl. Ecol. 50, 68–78 (2013).

Beyer, H. L. et al. You shall not pass!’: quantifying barrier permeability and proximity avoidance by animals. J. Anim. Ecol. 85, 43–53 (2016).

Xu, W., Gigliotti, L. C., Royauté, R., Sawyer, H. & Middleton, A. D. Fencing amplifies individual differences in movement with implications on survival for two migratory ungulates. J. Anim. Ecol. 92, 677–689. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13879 (2023).

Harrington, J. L. & Conover, M. R. Characteristics of ungulate behavior and mortality associated with wire fences. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 34, 1295–1305 (2006).

Rey, A., Novaro, A. J. & Guichón, M. L. Guanaco (Lama guanicoe) mortality by entanglement in wire fences. J. Nat. Conserv. 20, 280–283 (2012).

Wilson, R. R., Parrett, L. S., Joly, K. & Dau. J. R Effects of roads on individual caribou movements during migration. Biol. Conserv. 195, 2–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2015.12.035 (2016).

Boulanger, J. et al. Estimating the effects of roads on migration: a barren-ground caribou case study. Can. J. Zool. 102, 476–493. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjz-2023-0121 (2024).

Eacker, D. R., Jakes, A. F. & Jones, P. F. Spatiotemporal risk factors predict landscape-scale survivorship for a Northern ungulate. Ecosphere 14, e4341. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.4341 (2023).

Severson, J. P., Vosburgh, T. C. & Johnson, H. E. Effects of vehicle traffic on space use and road crossings of caribou in the Arctic. Ecol. Appl. 33, e2923. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.2923 (2023).

Bråthen, K. A. et al. Induced shift in ecosystem productivity? Extensive scale effects of abundant large herbivores. Ecosystems 10, 773–789 (2007).

Bernes, C., Bråthen, K. A., Forbes, B. C., Speed, J. D. M. & Moen, J. What are the impacts of reindeer/caribou (Rangifer Tarandus L.) on Arctic and alpine vegetation? A systematic review. Environ. Evid. 4, 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-014-0030-3 (2015).

Joly, K. et al. Longest terrestrial migrations and movements around the world. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-51884-5 (2019). Article 15333.

Cameron, M. D., Eisaguirre, J. M., Breed, G. A., Joly, K. & Kielland, K. Mechanistic movement models identify continuously updated autumn migration cues in Arctic caribou. Mov. Ecol. 9, 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40462-021-00288-0 (2021).

Joly, K. & Cameron, M. D. Early fall and late winter diets of migratory caribou in Northwest Alaska. Rangifer 38, 27–38. https://doi.org/10.7557/2.38.1.4107 (2018).

Webber, Q. M. R., Ferraro, K. M., Hendrix, J. G. & Vander Wal, E. What do caribou eat? A review of the literature on caribou diet. Can. J. Zool. 100, 197–207. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjz-2021-0162 (2022).

Joly, K., Cameron, M. D. & White, R. G. Behavioral adaptation to seasonal resource scarcity by caribou (Rangifer tarandus) and its role in partial migration. J. Mammal. 106, 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmammal/gyae100 (2025).

Gordon, B. C. 8000 years of caribou and human seasonal migration in the Canadian barrenlands. Rangifer Special Issue. 16, 155–162 (2005).

Borish, D. et al. Relationships between Rangifer and Indigenous well-being in the North American Arctic and subarctic: a review based on the academic published literature. Arctic 75, 86–104 (2022).

Watson, J. E. M. et al. Catastrophic declines in wilderness areas undermine global environment targets. Curr. Biol. 26, 2929–2934 (2016).

Bartsch, A. et al. Expanding infrastructure and growing anthropogenic impacts along Arctic Coasts. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 115013. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac3176 (2021).

Panzacchi, M. et al. Predicting the continuum between corridors and barriers to animal movements using step selection functions and randomized shortest paths. J. Anim. Ecol. 85, 32–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.12386 (2016).

Smith, A. & Johnson, C. J. Why didn’t the caribou (Rangifer Tarandus groenlandicus) cross the winter road? The effect of industrial traffic on the road-crossing decisions of caribou. Biodivers. Conserv. 32, 2943–2959. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-023-02637-4 (2023).

Joly, K. & Cameron, M. D. Caribou vital sign annual report for the Arctic Network Inventory and Monitoring Program. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.36967/2306687 (2024).

Joly, K. et al. Caribou and reindeer migrations in the changing Arctic. Anim. Migrations. 8, 156–167. https://doi.org/10.1515/ami-2020-0110 (2021).

Graham, M. Feds approve key step towards expansion at major Northwest Alaska zinc mine. Northern J. https://www.adn.com/business-economy/2024/12/14/feds-approve-key-step-toward-expansion-at-major-northwest-alaska-zinc-mine/ (2024).

Dau, J. Western Arctic herd. In Caribou Management Report of Survey and Inventory activities, 1 July 2000–30 June 2002. Study 3.0 (ed. Healy, C.) 204–251 (Alaska Department of Fish and Game, 2003).

Gunn, A. Voles, lemmings and caribou-population cycles revisited? Rangifer Special Issue. 14, 105–111 (2003).

Joly, K., Klein, D. R., Verbyla, D. L., Rupp, T. S. & Chapin, F. S. III Linkages between large-scale climate patterns and the dynamics of Alaska caribou populations. Ecography 34, 345–352. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2010.06377.x (2011).

Teck Resources Limited. Red Dog. https://www.teck.com/operations/united-states/operations/red-dog/ (2024).

Macander, M. J., Swingley, C. S., Joly, K. & Raynolds, M. Landsat-based snow persistence map for Northwest Alaska. Remote Sens. Environ. 163, 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2015.02.028 (2015).

Swanson, D. K. Trends in greenness and snow cover in alaska’s Arctic National Parks, 2000–2016. Remote Sens. 9, 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs9060514 (2017).

Joly, K., Gurarie, E., Hansen, D. A., Cameron, M. D. & M D Seasonal patterns of Spatial fidelity and Temporal consistency in the distribution and movements of a migratory ungulate. Ecol. Evol. 11, 8183–8200. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.7650 (2021).

Prichard, A. K. et al. Achieving a representative sample of marked animals: a Spatial approach to evaluating post-capture randomization. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 47 (1), e1398. https://doi.org/10.1002/wsb.1398 (2023).

Fullman, T. J., Gustine, J. K., Cameron, M. D. & D. D. & Behavioral responses of migratory caribou to semi-permeable roads in Arctic Alaska. Sci. Rep. 15, 24712. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10216-6 (2025).

Xu, W., Dejid, N., Herrmann, V., Sawyer, H. & Middleton, A. D. Barrier behaviour analysis (BaBA) reveals extensive effects of fencing on wide-ranging ungulates. J. Appl. Ecol. 58, 690–698 (2021).

Therneau, T. M. & Grambsch, P. M. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model. (Springer, 2000).

Therneau, T. M. A package for survival analysis in R. Manual. https://CRAN. R-project.org/package = survival (2022).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2024).

Cameron, M. D., Joly, K., Breed, G. A., Parrett, L. S. & Kielland, K. Movement-based methods to infer parturition events in migratory ungulates. Can. J. Zool. 96, 1187–1195. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjz-2017-0314 (2018).

Kelsall, J. P. The Migratory Barren-Ground Caribou Of Canada. 339 (Queen’s Printer, 1968).

Bergerud, A. T. Rutting behaviour of Newfoundland caribou. In The Behaviour Of Ungulates And Its Relation To Management. V. Geist and F. Walther, editors. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. 395–435 (1974).

Whitten, K. R., Garner, G. W., Mauer, F. J. & Harris, R. B. Productivity and early calf survival in the Porcupine caribou herd. J. Wildl. Manage. 56, 201–212 (1992).

Gurarie, E. et al. Evidence for an adaptive, large-scale range shift in a long-distance terrestrial migrant. Glob. Change Biol. 30, e17589. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.17589 (2024).

Miller, F. L., Jonkel, C. J. & Tessier, G. D. Group cohesion and leadership response by barren-ground caribou to man-made barriers. Arctic 25, 193–202 (1972). https://www.jstor.org/stable/40508046

Bart, J., Fligner, M. A. & Notz, W. I. Sampling and Statistical Methods for Behavioral Ecologists. 330 (Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Fancy, S. G. & White, R. G. Energy expenditures for locomotion by barren-ground caribou. Can. J. Zool. 65, 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1139/z87-018 (1987).

Parker, K. L., Barboza, P. S. & Gillingham, M. P. Nutrition integrates environmental responses of ungulates. Funct. Ecol. 23, 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2009.01528.x (2009).

Wasser, S. K., Keim, J. L., Taper, M. L. & Lele, S. R. The influences of Wolf predation, habitat loss, and human activity on caribou and moose in the Alberta oil sands. Front. Ecol. Environ. 9, 546–551. https://doi.org/10.1890/100071 (2011).

Cameron, R. D. & Ver Hoef, J. M. Predicting parturition rate of caribou from autumn body mass. J. Wildl. Manage. 58, 674–679 (1994).

Gerhart, K. L., Russell, D. E., Van DeWetering, D., White, R. G. & Cameron, R. D. Pregnancy of adult caribou (Rangifer tarandus): evidence for lactational infertility. J. Zool. 242, 17–30 (1997).

Johnson, C. J., Venter, O., Ray, J. C. & Watson, J. E. M. Growth-inducing infrastructure represents transformative yet ignored keystone environmental decisions. Conserv. Lett. 13, e12696. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12696 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Hansen (Alaska Department of Fish and Game) for his ongoing collaboration that makes our long-term monitoring program possible. We also thank the many people that have helped deploy GPS collars over the years. Funding for this project was provided by the National Park Service, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, and NSF Navigating the New Arctic grant 212727 (Fate of the Caribou). We thank H. Johnson, A. Hansen, S. Karpovich, and N. Edmison for reviews of a previous draft of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Data acquisition: KJ and MDC. Data management: KJ, MDC, and CB. Conceptualization and data interpretation: all authors. Data Analysis: CB, EG, TJF, KJ, and MDC. Original draft: KJ. Manuscript review, revision, and submission approval: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Joly, K., Beaupré, C., Fullman, T.J. et al. Barrier impermeability is associated with migratory ungulate survival rates. Sci Rep 16, 152 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31911-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31911-4