Abstract

Spinel ferrites represent a versatile class of compounds extensively utilized across various applications, particularly valued for their distinctive magnetic properties. Beyond their conventional uses, these materials have emerged as effective magnetic catalysts in organic synthesis for the production of diverse molecular structures. Herein, an alternative synthetic pathway is presented for obtaining CuFe2O4 through the thermal decomposition of Cu+ 2 and Fe+ 3 chelates, employing 8-hydroxyquinoline (8-HQ) as the coordinating ligand. The chelates were characterized by XRD, FTIR, XRF and SEM/EDS. A systematic study of their thermal decomposition was conducted by TGA, DTG, and DTA, under both oxygen and nitrogen atmospheres, varying the heating rate. Subsequently, the chelates were calcinated at different temperatures (750, 850, 950, and 1050 °C), yielding CuFe2O4 in powder form. The resulting CuFe2O4 was further characterized by XRD, SEM, TEM, and VSM analysis. The synthesized CuFe2O4 nanoparticles demonstrated excellent catalytic performance in the condensation reaction between 1,8-diaminonaphthalene and various aldehydes, producing a series of 2-substituted 2,3-dihydro-1H-perimidines in excellent yields. Finally, the CuFe2O4 nanoparticles were successfully recovered magnetically and efficiently employed in gram-scale reactions, demonstrating their practical recyclability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Magnetic copper ferrite nanoparticles (CuFe2O4MNPs) have garnered significant attention due to their diverse applications, including electronic components1, sensors2, wastewater treatment3, biomedical application4, photocatalysis5 and catalysis6,7. Spinel ferrites with the general formula MFe2O4 (where M = Mg, Mn, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn) are a prominent class of magnetic nanocatalysts, valued for their structural stability and facile magnetic recovery8. While members like CoFe2O4and NiFe2O4exhibit strong magnetism, and ZrFe2O4 shows high surface area, each has limitations such as cost, toxicity, or weaker magnetic response9,10,11. Among them, copper ferrite (CuFe2O4) stands out due to the unique redox activity of copper, which can access Cu⁺/Cu²⁺ states to facilitate electron transfer in catalytic cycles12. This redox versatility, combined with the Lewis acidity of its metal sites, makes CuFe2O4 exceptionally effective for activating organic substrates like aldehydes and imines, leading to superior performance in various organic transformations under sustainable conditions13.

Various synthetic routes are available in the literature for their synthesis, such as Pechini14,15sol-gel synthesis16, hydrothermal synthesis17,18, co-preciptation19,20, sonochemical methods21,22, and combustion synthesis23. Each approach enables precise control over physical, chemical, and magnetic properties of the material3.

Methodological parameters such as stoichiometry, pH, calcination temperature, presence of doping agents, and other factors directly influence the magnetic properties, morphological characteristics, particle size distribution, and overall composition of synthesized spinel ferrites3,24. Consequently, developing simpler, faster methodologies that allow rigorous control over the synthetic process is highly desirable.

In this context, thermal decomposition of chelates from 8-hydroxyquinoline (8-HQ) presents an attractive alternative25. This approach has already been successfully applied to the synthesis of magnetic cobalt ferrite nanoparticles (CoFe2O4 MNPs)26 and magnetic nickel ferrite nanoparticles (NiFe2O4MNPs)27, where the use of 8-HQ is advantageous from a synthetic point of view, since it is possible to form stable quinolates with well-defined stoichiometry, as well as the capacity to coordinate with metal ions with thermal and chemical stability. In this way, the choice of 8-HQ as a chelating agent is justified by its ability to form stable, stoichiometrically defined metal quinolinate complexes, which promote a controlled thermal decomposition pathway.

Moreover, CuFe2O4MNPS demonstrated remarkable catalytic performance in various transformations, including the formation of propargylamines and triazoles28, diaryl ethers29, bis(indolyl)methanes30, diaryl selenides31, tetrazoles32, dipyrimidines33 and pyridines34. For comprehensive review, see Liandi et al. (2023)7, Ghobadi (2022)6 and Sharma (2023)13.

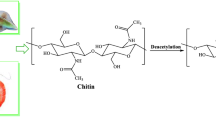

2-Substituted 2,3-dihydro-1H-perimidines constitute a class of heterocyclic compounds synthesized via condensation reactions between aldehydes and 1,8-diaminonaphthalenfe35,36. These reactions typically employ Lewis37,38 or Brønsted-Lowry39acids as catalysts. This class of compounds exhibits significant pharmaceutical potential due to their broad spectrum of biological activities, including antimicrobial40, anti-inflammatory41, antioxidant42, and anticancer properties43. Recently, magnetic catalysts have been explored for perimidine synthesis due to their magnetic behaviour, which allows for easy recovery and reuse, making them a more sustainable alternative34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46. Furthermore, the recent adoption of solvent-free systems for diverse organic transformations significantly advances the field of sustainable chemistry47,48,49,50.

Therefore, in connection with our continuing interest in designing functional materials51,52 and developing sustainable cross-coupling reactions53,54,55,56,57 as well as biologically relevant N-heterocyclic cmpounds58,59,60,61, herein we present a novel synthetic route for the preparation of CuFe2O4and its catalytic evaluation in the condensation reaction to synthesize 2-substituted 2,3-dihydro-1H-perimidines, including an assessment of catalyst recyclability.

Materials ad methods

Reagents and equipment for synthesis and characterization of 8-hydroxyquinoline chelates and CuFe2O4 MNPs

All reagents were commercially acquired for the synthesis of iron and copper chelates and, consequently, copper ferrite. The crystalline structure of chelates were analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a Rigaku® SmartLab SE diffractometer with CuKα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å), operating at 30 mA and 40 kV. The scanning conditions were set to a speed of 2° min⁻¹ (2θ), a step size of 0.02°, and a scanning range from 5° to 100° (2θ). The Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was performed using a PerkinElmer® Frontier FT-IR spectrometer in the range of 4000 to 400 cm⁻¹, with a resolution of 2 cm⁻¹ and 16 accumulations. The samples were prepared as KBr pellets. Subsequently, the elemental composition was determined by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) using a Shimadzu® EDXRF-7000 spectrometer equipped with a Rh tube, operating in air atmosphere with an SDD detector. Measurements were performed with a 5 mm and 10 mm collimator, under the following conditions: 1–40 keV for the Al–U channel and 1–20 keV for the Na–Sc channel. The chelate’s morphology in powder form was characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a TESCAN VEGA3. The operated software was VEGA3 Control Sofware (ver. 4.2.37.0 build 1695, http://tescan.com/). The sample was deposited on carbon tape and sputter-coated with gold for 3 min prior to analysis. The elemental analysis was performed using an Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy Analysis (EDS) were performed in a TESCAN VEGA3 LMU electron microscope using a silicon drift detector (SSD) of 80 mm². The operated software was VEGA3 Control Sofware (ver. 4.2.37.0 build 1695, http://tescan.com/). Furthermore, thermal behavior was evaluated through thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential thermal analysis (DTA) using a TA Instruments SDT Q600 system. The analyses were carried out under an oxygen atmosphere (flow rate of 50 mL min⁻¹) with heating rate 10 °C min⁻¹. All experiments were performed from room temperature up to 1200 °C using alumina crucibles.

The copper ferrite calcination process was carried out in a tubular horizontal furnace (Sanchis®) with a quartz tube under pure oxygen (flow rate of 300 mL min⁻¹) and a heating rate of 20 °C min⁻¹. An isothermal step of 30 min was applied at temperatures of 750, 850, 950, and 1050 °C. Approximately 2.9 g of the pH08-CuFe sample was placed in an α-alumina crucible for each thermal treatment and characterization. Additionally, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis was performed using a JEOL JEM-1200EXII microscope operating at 80 kV. The powder sample was dispersed in ethanol, ultrasonicated for 5 min, and three drops of the suspension were deposited onto a copper grid for observation. Finely, the magnetic behavior of the material was evaluated by Vibrating Sample Magnetometer (VSM), using a superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) magnetometer with a ± 70 kOe superconducting coil, and an AC susceptometer operating in the frequency range of 0.1 to 1000 Hz.

Reagents and equipment for synthesis and characterization of 2,3-dihydro-1H-perimidines

The reagents 1,8-diaminonaphtalene, aldehydes and solvents were commercially acquired. The Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectra of Hydrogen and Carbon (1H and 13C NMR) were obtained on a Bruker DPX-300 Avance spectrometer and a Bruker Ascend 400 MHZ using CDCl3 as the solvent. All chemical shifts were reported in parts per million (ppm), with the 1H spectrum referenced to 0.00 ppm (TMS) and the 13C spectrum referenced to 77.16 ppm (CDCl3). The infrared data were acquired with a Perkin Elmer infrared spectrometer, model Frontier, from 4000 to 650 wave number (cm− 1), in ATR mode. The thin layer chromatography (TLC) plates utilized were GF254 silica with a thickness of 0.20 mm, from the brand Macherey-Nagel, and the visualization methods utilized were iodine chamber and ultraviolet light (254 nm). UV-Vis analysis were carried out in a Shimadzu UV-1900 spectrometer, using 1 cm quartz cuvettes, in the region 200 to 800 nm. A stock solution of 0.5 × 10− 3 mol.L− 1 in ethanol was prepared to perform the dilutions of the different concentrations of the perimidines 3a-m.

CuFe2O4 MNPs synthesis from 8-hydroxyquinoline chelates

To obtain the quinolinates precipitate, two solutions were prepared (A and B). Solution A was prepared by dissolving 24.3642 g of 8-HQ in 150 mL of propanone and transferring the mixture to a 1 L beaker. Solution B was prepared by dissolving16.895 g of ferric nitrate nonahydrate (Fe(NO3)3.9H2O) and 5.048 g of copper nitrate trihydrate (Cu(NO3).3H2O) in 80 mL of distilled water in a 250 mL beaker. Solution B was then transferred to the 1 L beaker containing solution A, followed by pH adjustment to 1 using nitric acid (HNO3).

The mixture was left under constant stirring at ambient temperature. After the reaction medium was stable, NH4OH 10% (v/v) was added slowly until the pH reached 8,3 and then was left under stirring for 2 h. The solution was allowed to digest for 24 h. Finally, the precipitate was washed with distilled water, filtrated, and dried in stove at 55 °C for 24 h to obtain the 8-hydroxyquinoline chelate, which was named pH08-CuFe chelate.

The synthesis of CuFe2O4 MNPs was carried out by adding approximately 2.9 g of sample pH08-CuFe chelate in a crucible, and then calcination at temperatures of 750, 850, 950, or 1050 °C with 30 min of holding time in pure oxygen atmosphere with gas flow of 300 mL min− 1. Thereafter, the solids were macerated in mortar and pistil and identified as CuFe2O4 MNPs pH08-750, pH08-850, pH08-950 and pH08-1050, respectively.

The pH08-CuFe chelate was characterized by XRD, SEM/EDS, FTIR, SEM and XRF analysis and also the thermic behaviour was analyzed by TGA, DTG, and DTA. While the CuFe2O4 MNPs was analysed by XRD, SEM, TEM, and VSM in powder form.

General procedure for the synthesis of 2-substitued 2,3-dihydro-1H-permidine

In a 5 mL test tube, containing a magnetic bar, 79.1 mg (0.5 mmol) of 1,8-diaminonaphtalene 1 and CuFe2O4 MNPs (1 mol %, 1.2 mg) were added and heated until 70 °C. Then, after the mixture had fused into a reddish liquid the respective aldehyde 2a-m (0.5 mmol) was added. The reaction progress was monitored by TLC until complete consumption of starting materials.

Following the reaction completion, the CuFe2O4 MNPS catalyst was separated from the mixture within the magnetic bar surface using an external magnet. Afterwards, the organic phase was solubilized in ethanol (10 mL) and the product was recrystallized in cold water bath (15 mL). Finally, the precipitate was filtered and dried at an ambient temperature.

IR spectra indicated the key connections (functional groups) in the synthesized compounds. The presence of the band around 3360–3380 cm-1 refers to the stretching of the ν(NH) bonds, just as the weak band around 3040–3050 cm-1 is attributed to aromatic carbons, due to their axial deformations of the ν(C-H) bonds of the CHs, while the bands around 1580–1620 and 1450–1490 cm-1 are due to the stretching of the ν(C = C) bonds of the unsaturation of the aromatic ring. In the 1HNMR, a distinct singlet was noticed in the range 5.0–5.5.0.5 ppm, which is the characteristic peak of C-H for the 2,3-dihydro-1 H-perimidines. Except for the methyl or methoxy or hydroxy group, the rest of the signals were observed in the aromatic range. In the 13CNMR, a characteristic peak for the 2,3-dihydro-1 H-perimidines carbon was observed in the range of 62.0–69.0 ppm. Similar to 1HNMR, for the 13CNMR, except for the methyl or methoxy group, the rest of the signals were observed in the aromatic range. The spectral data for all compounds are presented below and the NMR (Figures S1-S26) and IR (Figures S27-S39) spectra are available in the Support Information.

2-phenyl-2,3-dihydro-1 H-perimidine (3a)62: ¹H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 7.60 (d, 2 H), 7.42 (m, 3 H), 7.22 (m, 4 H), 6.49 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 2 H), 5.42 (s, 1 H), 4.49 (s, 2 H). ¹³C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 142.23, 140.20, 135.01, 129.72, 128.96, 128.04, 127.00, 118.00, 113.57, 105.95, 68.51. IR: ̃/cm⁻¹: 3383, 3358, 3040, 1913, 1833, 1723, 1595, 1481, 1457, 1414, 1380, 1258, 1162, 1129, 1070, 1023, 810, 754, 706.

2-(p-tolyl)−2,3-dihydro-1 H-perimidine (3b)62: ¹H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 7.48 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 2 H), 7.27–7.16 (m, 6 H), 6.46 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2 H), 5.38 (s, 1 H), 4.46 (s, 2 H), 2.38 (s, 3 H). ¹³C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 142.33, 139.59, 137.31, 135.01, 129.57, 127.89, 126.98, 117.90, 113.56, 105.88, 68.28, 21.40. IR: ̃/cm⁻¹: 3365, 3045, 2981, 1601, 1486, 1418, 1382, 1267, 1167, 1072, 814, 766, 708.

(E)−2-styryl-2,3-dihydro-1 H-perimidine (3c)64: ¹H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 7.48–7.02 (m, 9 H), 6.76 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1 H), 6.51 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2 H), 6.42–6.34 (dd, J1 = 15.9, J2 = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 5.05 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 4.43 (s, 2 H). ¹³C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 141.22, 135.77, 134.90, 134.76, 128.86, 128.64, 128.12, 127.04, 126.94, 117.92, 113.59, 106.18, 67.15. IR: ̃/cm⁻¹: 3381, 3041, 2982, 2793, 1916, 1820, 1717, 1593, 1483, 1412, 1380, 1244, 1127, 962, 813, 752, 696.

2-(2-bromophenyl)−2,3-dihydro-1 H-perimidine (3d)62: ¹H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 7.84 (dd, J1 = 7.8, J2 = 1.7 Hz, 1 H), 7.62 (dd, J1 = 8.0, J2 = 1.11 Hz, 1 H), 7.40 (td, J1 = 7.8, J2 = 0.9 Hz, 2 H), 7.26–7.22 (m, 5 H), 6.59 (dd, J1 = 7.0, J2 = 1.2 Hz, 2 H), 5.94 (s, 1 H), 4.63 (s, 2 H). ¹³C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 141.70, 137.70, 133.91, 133.15, 130.70, 129.56, 128.42, 127.08, 123.41, 120.74, 118.21, 106.25, 66.53. IR: ̃/cm⁻¹: 3379, 3350, 3042, 2846, 1597, 1484, 1474, 1417, 811, 759.

2-(3-bromophenyl)−2,3-dihydro-1 H-perimidine (3e)62: ¹H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 7.86 (t, J = 1.7 Hz, 1 H), 7.59 (m, 5 H), 7.34 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.29–7.24 (m, 5 H), 6.57 (dd, J1 = 6.6, J2 = 1.6 Hz, 2 H), 5.47 (s, 1 H), 4.54 (s, 2 H). ¹³C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 141.81, 135.24, 132.88, 131.32, 130.57, 127.05, 126.73, 123.04, 120.77, 118.35, 106.20, 67.89. IR: ̃/cm⁻¹: 3391, 3353, 3063, 2839, 1599, 1473, 1473, 1417, 814, 766.

2-(4-bromophenyl)−2,3-dihydro-1 H-perimidine (3f)62: ¹H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 7.51 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2 H), 7.41 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2 H), 7.25–7.17 (m, 4 H), 6.46 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 2 H), 5.31 (s, 1 H), 4.40 (s, 2 H). ¹³C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 141.83, 139.17, 134.90, 132.04, 129.69, 126.99, 123.62, 118.15, 113.44, 106.06, 67.73. IR: ̃/cm⁻¹: 3364, 3334, 2981, 1929, 1908, 1599, 1482, 1414, 1377, 1262, 1070, 1011, 816, 762, 718.

2-(4-chlorophenyl)−2,3-dihydro-1 H-perimidine (3 g)62: ¹H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 7.65–7.04 (m, 8 H), 6.50 (s, 2 H), 5.39 (s, 1 H), 4.43 (s, 2 H). ¹³C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 141.78, 138.64, 135.38, 134.85, 129.31, 129.02, 126.90, 118.10, 113.40, 105.98, 67.66. IR: ̃/cm⁻¹: 3389, 3036, 2798, 1908, 1596, 1484, 1418, 1402, 1381, 1259, 1164, 1130, 1088, 1014, 812, 756.

3-(2,3-dihydro-1 H-perimidin-2-yl)phenol (3 h)63: ¹H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 7.37–7.10 (m, 8 H), 6.90 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1 H), 6.53 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 2 H), 5.41 (s, 1 H), 4.54 (s, 2 H). ¹³C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 156.27, 142.67, 130.26, 127.04, 120.30, 118.13, 116.76, 114.68, 106.08, 68.24. IR: ̃/cm⁻¹: 3402, 3287, 3048, 2791, 1599, 1454, 1413, 1262, 1162, 1070, 928, 868, 803, 752, 742, 704.

4-(2,3-dihydro-1 H-perimidin-2-yl)phenol (3i)63: ¹H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 7.52 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2 H), 7.29–7.17 (m, 5 H), 6.89 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2 H), 6.52 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2 H), 5.42 (s, 1 H), 4.54 (s, 2 H). ¹³C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 156.76, 142.40, 135.08, 132.65, 129.57, 127.03, 117.99, 115.72, 113.39, 105.91, 68.08. IR: ̃/cm⁻¹: 3365, 3301, 2822, 1599, 1489, 1411, 1380, 1239, 1171, 1039, 987, 819, 768.

2-(4-methoxyphenyl)−2,3-dihydro-1 H-perimidine (3j)62: ¹H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 7.52 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 2 H), 7.22 (m, 4 H), 6.94 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 2 H), 6.46 (s, 2 H), 5.36 (s, 1 H), 4.44 (s, 2 H), 3.80 (s, 3 H). ¹³C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 160.64, 142.41, 135.04, 132.44, 129.24, 126.98, 117.87, 114.22, 113.56, 105.83, 68.01, 55.49. IR: ̃/cm⁻¹: 3365, 3040, 3002, 2969, 2838, 1920, 1900, 1597, 1484, 1409, 1299, 1238, 1182, 1114, 1025, 847, 814, 762, 665.

4-(2,3-dihydro-1H-perimidin-2-yl)−2-methoxyphenol (3k)63: ¹H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 7.26–7.20 (m, 5 H), 7.06 (dd, J1 = 8.0, J2 = 1.9 Hz, 1 H), 6.95 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 6.53 (dd, J1 = 7.0, J2 = 1.2 Hz, 2 H), 5.75 (s, 1 H), 5.41 (s, 1 H), 4.51 (s, 2 H), 3.94 (s, 3 H). ¹³C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 147.19, 144.02, 142.39, 138.40, 127.05, 121.35, 118.04, 114.17, 113.58, 109.99, 105.91, 68.53, 56.26. IR: ̃/cm⁻¹: 3369, 3354, 2863, 1596, 1510, 1408, 1241, 1029, 814, 744.

2-(2-nitrophenyl)−2,3-dihydro-1H-perimidine (3 L)63: ¹H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 8.04 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1 H), 7.93 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.64 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.51 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.36–7.15 (m, 4 H), 6.57 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 2 H), 5.92 (s, 1 H), 4.83 (s, 2 H). ¹³C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 149.53, 140.78, 136.24, 134.80, 134.04, 129.78, 129.76, 127.19, 124.44, 117.23, 112.97, 106.20, 62.47. IR: ̃/cm⁻¹: 3358, 3230, 3044, 2839, 1915, 1598, 1516, 1412, 1332, 1278, 1166, 1125, 1072, 979, 875, 822, 758, 739, 704.

2-(pyridin-2-yl)−2,3-dihydro-1H-perimidine (3 m)64: ¹H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 8.62 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.76–7.70 (td, J₁ = 7.7, J₂ = 1.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.63 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.29–7.21 (m, 5 H), 6.62–6.60 (dd, J₁ = 6.7, J₂ = 1.2 Hz, 2 H), 5.60 (s, 1 H), 4.95 (s, 2 H). ¹³C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl₃): δ = 159.42, 149.52, 141.10, 137.42, 134.88, 127.05, 123.78, 120.96, 118.25, 114.16, 106.85, 67.87. IR: ̃/cm⁻¹: 3693, 3047, 2984, 2924, 1902, 1594, 1414, 1265, 1154, 1089, 997, 812, 748, 690.

CuFe2O4 MNPs recycling and leaching test

The recyclability of CuFe2O4 MNPs was evaluated using the same procedure described above for the synthesis of 2,3-dihydro-1H-perimidines. The standard reaction between 1,8-diaminonaphthalene 1 (0.5 mmol) and benzaldehyde 2a (0.5 mmol) was conducted using 1 mol % of catalyst (1.2 mg) to synthesize product 3a. After completion of the reaction in 3 min, confirmed by TLC, the catalyst adhered to the magnetic stir bar was recovered and washed five times with ethanol, then dried for a minimum of 12 h at room temperature under air atmosphere. Subsequent reactions were performed using the same magnetic stir bar with CuFe2O4 magnetically bound to its surface. This recovery and reuse process was repeated for successive catalytic cycles.

For the leaching test, a standard reaction between the compounds 1 and 2a was carried out during 1.5 min and the reaction was filtered using 14 μm filter paper with hot ethyl acetate. The filtrate was used again for another 1.5 min at 70 °C and was observed that the condensation reaction does not proceed further as the catalyst was removed by filtration and the quantity of the product 3a did not change. Furthermore, for copper leaching test the Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometer (ICP-OES) measurements were carried out on a Perkin Elmer Optima 7.000 DV ICP-OES. The calibration curve was carried out from copper concentrations of 1.0, 5.0, 10.0, 20.0 and 30.0 ppm, which obtained an r2 of 0.999923. The digestion of organic matter sample was performed with hot sulphuric acid.

Scale up synthesis

In a 50 mL round bottom flask containing a magnetic stir bar, 1,8-diaminonaftalene 1 (4.065 mmol, 643 mg) and 1 mol % of CuFe2O4 MNPs (0.04065 mmol, 9.7 mg) were added, then after the medium was fused in a reddish liquid and under stirring the benzaldehyde 2a (4.065 mmol, 414 µL) was added. After completion of the reaction in 3 min, confirmed through TLC, the crude product was dissolved in ethanol (10 mL) and recrystallized in cold water (15 mL) to afford product 3a.

Results and discussion

Structural characterization of the chelate

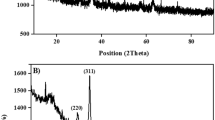

The crystallographic behaviour of 8-HQ and the sample pH08-CuFe chelate is shown in the diffractogram in Fig. 1A. Peak indexing was performed using crystallographic charts n.º 00–027-1692 for the iron chelate Fe(C9NH6O)3, JCPDS n.º 00–019-1869, for the copper chelate Cu(C9NH6O)2, and JCPDS nº 00–039-1857 for 8-HQ.

Analysis of the diffractogram (Fig. 1A) revealed no characteristic peaks of 8-HQ in the pH08-CuFe chelate. However, peaks corresponding to iron and copper chelates were identified, demonstrating that 8-HQ effectively formed chelates with metal ions and confirming successful removal of excess 8-HQ during the washing procedure. The chemical composition of the pH08-CuFe chelate was determined by XRF (Fig. 1B). The major elements detected in the spectrum were copper and iron, which corroborate the expected composition of this compound, given its chemical formula CuFe2(C9H6NO)8. The emissions of silicon, argon and sulfur can be attributed to the cellophane paper, while the rhodium signal originates from the background radiation of the tube. Although the analysis was not quantitative, peak intensity indicates that iron concentration exceeds that of copper. Furthermore, the chelates synthesis was carried out using 1:2 molar ratio of copper to iron, which supports this difference in concentration and further confirms the formation of the iron and copper chelates.

Moreover, the EDS spectrum in Fig. 1C demonstrates the presence of copper and iron in different proportions in the pH08-CuFe chelate sample, reinforcing the chelating effect of 8-HQ on metal nitrates and corroborating the XRF analysis.

Vibrational spectroscopy analysis of the chelate

FTIR spectra of 8-HQ and the pH08-CuFe chelate sample (Figure S40, Supporting Information) show distinct differences attributed to the chelating effect of 8-HQ with metal ions65. For example, the vibrational band carbon-oxygen (C-O) at 1108 cm− 1 is reported to increase when the 8-HQ is in its chelate form25,66,67.

Additional spectral features include bands at 405 and 504 cm− 1, which can be assigned to M-N bonds or the stretching vibrational mode of M-O bonds. These bands are sensitive and dependent on the metal ion66. For instance, M-O stretching has been reported at 455 cm−1for calcium quinolinates68, below 400 cm−1 for gallium69, at 559 cm− 1for cobalt70, at 643, 599 and 559 cm−1for manganese71, and at 505 cm−1 for nickel67. In this study, M-O stretching was identified at approximately 521 cm−1 for both the iron (Fe(C9H6NO)3) and copper(Cu(C9H6NO)2) chelates.

Morphological analysis of the chelate and CuFe2O4 MNPs

The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of the pH08-CuFe chelate sample with an elongated prism-like morphology (Fig. 2 (A)). The thermal annealing (1050 °C) and under an oxidative atmosphere enable the obtainment of CuFe2O4 (Fig. 3). Although the nanosized particles can be noticed in TEM analysis (Figure S41, Supporting Information), the SEM image (Fig. 2 (B)) reveals that the synthesized powder has a porous morphology, demonstrating a significant degree of coalescence. This characteristic can be attributed to the sintering process, which, combined with magnetization, results in the formation of large agglomerates in the sample under analysis, a phenomenon also observed in other studies72.

Thermal analysis of the chelate

Figure S42 (Support Information) shows the TGA and DTA curves of the pH08-CuFe chelate. The sample under heating of 10 °C/min and oxygen flow showed a 4% mass loss between 105 and 200 °C, which is attributed to dehydration.

Afterwards, the most significant mass loss of 78,5% occurred between 220 and 470 °C, corresponding to the oxidative decomposition of the anhydrous compound. This process was exothermic, as evidenced by the DTA curve (Figure S42 (B) Support Information). The decomposition temperature of the compound is approximately 400–430 °C.

Phase formation study of the CuFe2O4 MNPs

The calcination temperature for synthesizing pure copper ferrite was studied by varying the temperatures to 750, 850, 950, and 1050 °C, respectively, with the heating rate of 20 °C min− 1 and an isotherm hold for 30 min.

The samples were nominated as CuFe2O4 MNPs pH08-750, pH08-850, pH08-950 and pH08-1050, and their peaks were indexed using the crystallographic chart JCPDS n.º 01–072-1174 for copper ferrite, which has a tetragonal crystalline structure and unit cell parameters of a and b equals 5,8100 Å and c equal to 8,7100 Å, with the angles α, β and γ equals to 90,0000°, as presented in Fig. 3.

The effect of the temperature on phase formation is evident in the XRD patterns of samples CuFe2O4 MNPs pH08-750, pH08-850, and pH08-950 (Fig. 3). At 750 and 850 °C, the presence of secondary phases was identified, with peaks corresponding to hematite (Fe2O3) and copper oxide (CuO). The hematite phase was indexed to the rhombohedral crystal system (space group R-3c) with unit cell parameters a = b = 5,0325 Å, c = 13,7404 Å, and interaxial angles α = β = 90° and γ = 120°, based on JCPDS n.º 01–073-2234. The CuO phase was assigned to the monoclinic crystal system (space group C2/c), exhibiting unit cell parameters a = 4,6870 Å, b = 3,4220 Å, and c = 5,1300 Å, and angles α = 90,0000°, β = 99,5000° and γ = 90,0000°, according to JCPDS n.º 01–089-5897. Notably, at 950 °C, no secondary phases were detected, indicating the formation of phase-pure CuFe2O4.

In addition, the presence of Fe2O3and CuO has been reported in various synthetic routes, including the Pechini method at 700 °C 8, sonochemical synthesis at 800 °C22, sol-gel at 750 and 950 °C72, and co-precipitation at 400, 500 and 600 °C73.

The comparison between CuFe2O4 MNPs pH08-750 and pH08-850 reveals that higher calcination temperatures favors the formation of phase-purer CuFe2O4. This is evidenced by the reduction in intensity of the hematite peak at 24° (2θ), and the copper oxide peak at 38,7° (2θ), indicating a decrease in impurities phases. Similar trends have been reported in literature for comparable calcination conditions72.

Although no secondary phases were detected in pH08-950, when the synthesis was scale up, CuO was identified as an impurity. To address this, the calcination procedure was repeated at 1050 °C, yielding a phase-pure CuFe2O4 MNPs even in larger-scale synthesis.

Magnetic properties of CuFe2O4

The magnetic properties of CuFe2O4 MNPs were investigated using a Vibrating Sample Magnetometer (VSM). Figure 4 presents the magnetic hysteresis curves recorded at room temperature for CuFe2O4 MNPs calcined at 1050 °C. The nanocrystals exhibited weak ferromagnetic behavior, with a coercive force (Hc) of 30.49 Oe, a saturation magnetization (Ms) of 21.62 emu/g, and a remanent magnetization (Mr) of 11.34 emu/g, values comparable to those reported by S. Anandan et al.74

Synthesis of 2-substituted 2,3-dihydro-1H-perimidines

Reaction parameters were optimized using a model reaction between 1,8-diaminonaphtalene 1 and benzaldehyde 2a. Given the melting point of 1,8-diaminonaphtalene 1 at 65 °C, the reaction temperature was set to 70 °C, ensuring a homogenous reaction medium in absence of solvents. Under these conditions, a viscous reddish liquid was formed, facilitating efficient mixing.

To evaluate the influence of calcination temperature on catalytic performance, CuFe2O4 synthetized at 750, 850, 950, and 1050 °C was investigated. Initially, 1.0 mol % of CuFe2O4 calcined at 1050 °C (sample CuFe2O4 MNPs pH08-1050) was employed, and reaction progress was monitored by thin layer chromatography (TLC). The product 3a was obtained in 99% yield within 3 min (Table 1, entry 1). A similar efficiency was observed for ferrite calcinated at 850 and 950 °C (Table 1, entry 2 and 3). However, when CuFe2O4 calcined at 750 °C was used under identical conditions, the yield decreased to 64% (Table 1, entry 4), suggesting incomplete phase formation and reduced catalytic activity as lower calcination temperatures.

Further optimization involved reducing the catalyst loading to 0.5 mol %, which led to a decrease in yield from quantitative (entry 3) to 68% (entry 4), demonstrating a dependence on catalyst concentration.

The correlation between calcination temperature and the catalytic performance of CuFe2O4 can be attributed to the purity of material, as discussed in the previous section on the characterization of the copper ferrites. The results indicate that higher calcination temperatures favour the formation of more phase-pure CuFe2O4, which in turn enhances its catalytic efficiency. Thus, the absence of secondary phases directly contributes to the improved catalytic activity.

With the optimal reaction conditions established, the robustness of the synthetic route was evaluated using aldehyde bearing different substituents at various positions on the aromatic ring, as presented in Fig. 5.

As previously described, benzaldehyde 2a led to the formation of product 3a with a quantitative yield (99%). The introduction of methyl group in para position 2b resulted in product 3b with an 89% yield. The use of a vinylic aromatic aldehyde, such as the trans-cinnamaldehyde 2c, yielded perimidine 3c in 84% yield.

Additionally, when used bromo substituent at the ortho, meta and para position of the aromatic ring (2d-f), the desired products 3d, 3e and 3f were obtained in 55%, 75% and 97% yields, respectively. Likewise, the use of para-chloro benzaldehyde 2 g affording the corresponding product 3 g in 79% yield.

The aldehydes containing methoxy and hydroxyl substituents at the meta and para position (2 h-j) proved to be suitable substrates for the synthesis of products 3 h, 3i and 3j in 85, 86, and 99% yield, respectively. In addition, the perimidine 3k, synthesized from vanillin 2k was obtained in 80% yield.

Notably, the presence of a nitro group at the ortho position formed the product 3 L with a high yield of 90%. Lastly, when employing a heteroaryl aldehyde 2 m, the desired perimidine 3 m was obtained in 88% yield.

CuFe2O4 MNPs recycling

The reusability of the catalyst was evaluated through the model reaction between 1,8-diaminonaphtalene 1 and benzaldehyde 2a to synthesize the product 3a (Fig. 6). Thanks to its magnetic properties, the catalyst was easily recovered using an external magnet, since it remained attached to the magnetic bar.

The catalyst efficiency demonstrated stability for up to six cycles. In the first two cycles, the yield was quantitative (99 − 98%). However, a gradual decline in yield (74–81%) was observed over the next four cycles.

To prove that the catalysis is heterogeneous was performed the hot filtration test. To that end, was carried out the standard reaction between the compounds 1 and 2a during 1.5 min and the reaction was filtered with hot ethyl acetate. The filtrate was used again for another 1.5 min at 70 °C and was observed that the condensation reaction does not proceed further as the catalyst was removed by filtration and the quantity of the product 3a did not change. This result indicate that the catalyst is indeed heterogeneous. Furthermore, was performed the ICP-OES analysis of the solid obtained after the reaction and the analysis shows no leached copper in the sample.

Furthermore, the catalytic performance of CuFe2O4 MNPs was further benchmarked by comparing its efficiency and reactions conditions, such as reaction time, recyclability and yield against recently reported magnetic catalyst employed in the synthesis of 1H-perimidines or 2,3-dihydro-1H-perimidines, as shown in Table 2.

While CuFe2O4 MNPs achieved comparable yields in the synthesis of 2,3-dihydro-1H-perimidine, it outperformed other catalysts in recyclability and reaction time. Another advantage of the CuFe2O4 is the simplicity of the synthesis, also described in this present work, when compared to the synthetic route of the other magnetic catalysts.

‘To our knowledge, this is the first report of the application of CuFe2O4 MNPs in the synthesis of 2,3-dihydro-1H-perimidines. Furthermore, it demonstrates a superior catalytic profile compared to other magnetic catalysts reported in the literature. As summarized in Table 2, our CuFe2O4 system operates under exceptionally mild, solvent-free conditions and achieves quantitative yields in remarkably short reaction times (3 minutes). Furthermore, it exhibits outstanding recyclability, maintaining high activity over six consecutive cycles, surpassing the stability of most comparable catalysts. This combination of exceptional activity, rapid kinetics, and robust reusability, coupled with a simple and scalable synthesis protocol for the catalyst itself, presents a significant advancement in the sustainable synthesis of this privileged heterocyclic scaffold.

Proposed mechanism

The common proposed mechanism of catalysis reported in literature for perimidines is the activation of the aldehyde by an acid catalyst35. Accordingly, we propose a similar approach for the CuFe2O4 catalysis mechanism.

Copper ferrite has been employed as a catalyst in the synthesis of -aminonitriles77 and chromeno[4,3-b]pyrrol-4(1H)-one derivatives78, where both mechanisms initiate with aldehyde activation by copper ferrite. Additionally, the initial steps in chromeno[4,3-b]pyrrol-4(1H)-one synthesis involve imine formation followed by nucleophilic addition, which are analogous to the reported perimidine mechanism35,44. Therefore, the proposed catalytic mechanism starts with the coordination of Fe+3 active site to the aldehyde oxygen, followed by stabilizing coordination of Cu+2 metal center to the imine double bond78. This highlights the synergistic role of both Fe+3 and Cu+2 sites in the catalytic performance.

As discussed in the optimization section, the catalytic activity of CuFe2O4 MNPs is related to its purity. The impurities identified as Fe2O3 and CuO, which were indexed with rhombohedral and monoclinic crystal lattice, may disrupt the proximity of copper and iron active sites. This detachment could be responsible for the observed decrease in catalytic efficiency in samples containing such impurities. Hence, this further indicates the participation of both copper and iron sites in the catalytic pathway.

The proposed mechanism for 2,3-dihydro-1H-perimidine synthesis (Fig. 7) proceeds as follows: Initially, the aldehyde is activated by coordination to Fe³⁺ tetrahedral sites of the catalyst (I). Subsequently, 1,8-diaminonaphthalene acts as a nucleophile, attacking the activated aldehyde to form a Schiff base imine with concomitant water elimination (II). The resulting imine is then stabilized by coordination to Cu²⁺ octahedral sites of copper ferrite and undergoes intramolecular nucleophilic addition with the remaining amine group (III). Finally, following proton loss, the 2,3-dihydro-1H-perimidine product is formed and the CuFe2O4 catalyst is regenerated for the next catalytic cycle (IV).

Scaled up synthesis of perimidine

In order to evaluate the scalability and practical applicability of the methodology, the standard reaction was scaled up using 1,8-diaminonaphthalene 1 (4.065 mmol, 643 mg) and benzaldehyde 2a (4.065 mmol, 414 µL) with 1 mol % of CuFe2O4 MNPs catalyst (0.04065 mmol, 9.7 mg), as shown in Fig. 8. The reaction afforded product 3a in 91% yield (910 mg), demonstrating the effectiveness of the method at larger synthetic scales.

Determination of molar absorption for all compounds (3a-m)

Finally, due to highly conjugated π electron system and the characteristic coloration of the perimidines, was calculated the molar absorptivity coefficient (ε) of the main absorption bands for all compounds (Table 3). Therefore, UV-vis analysis of all compounds at different concentrations was performed and calculated the molar absorptivity coefficient (ε) from the Lambert-Beer equation.

The UV-Vis spectra and the absorbance plotted against perimidine concentration, to determine the molar absorptivity of the products 3a-m at different wavelengths, are found in the Support Information (Figures S43-S55).

Conclusions

The present study shows that CuFe2O4 can be successfully synthesized through thermal decomposition of Fe+ 3 and Cu+ 2 with 8-HQ, in oxidative atmosphere and the heating rates of 5, 10 and 20 °C min− 1. This novel synthetic route provides an alternative to conventional preparation methods. However, XRD analysis revealed that pure copper ferrite formation requires calcination temperatures of 850 °C or higher; lower temperatures result in the formation of Fe2O3 and CuO impurities. Also, the scale up process demonstrated that the temperature needed for pure copper ferrite in bulk synthesis is 1050 °C.

The synthesized CuFe2O4 nanoparticles exhibited excellent catalytic performance in the condensation reaction to produce 2-substituted 2,3-dihydro-1H-perimidines. With the exception of the ortho-bromo derivative, which yielded 55%, all other substrates produced moderate to high yields (79–99%). The gram-scale reaction achieved an impressive yield of 91%, confirming the effectiveness of the catalyst at synthetically relevant scales. The catalyst demonstrated exceptional recyclability, maintaining catalytic activity through six consecutive cycles with yields decreasing from 99% to 80%. This performance is comparable to other magnetic catalysts reported in the literature. The magnetic properties of CuFe2O4 enabled facile recovery and reuse, highlighting its practical advantages for sustainable catalysis. A plausible catalytic mechanism was proposed by integrating established copper ferrite mechanisms for imine formation with the commonly accepted pathway for perimidine synthesis, providing insight into the mode of action of the catalyst in this transformation. Finally, a study of the perimidines electronic properties by UV-Vis analysis was carried out in order to obtain the molar absorptivity coefficients of all synthesized compounds.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information file.

References

Silveyra, J. M., Ferrara, E., Huber, D. L. & Monson, T. C. Soft magnetic materials for a sustainable and electrified world. Science 362, 418 (2018).

Ranga, R. et al. Ferrite application as an electrochemical sensor: A review. Mater. Charact. 178, 111269 (2021).

Masunga, N., Mmelesi, O. K., Kefeni, K. K. & Mamba, B. B. Recent advances in copper ferrite nanoparticles and nanocomposites synthesis, magnetic properties and application in water treatment: review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 7, 103179 (2019).

Ansari, M. A., Baykal, A., Asiri, S. & Rehman, S. Synthesis and characterization of antibacterial activity of spinel Chromium-Substituted copper ferrite nanoparticles for biomedical application. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 28, 2316–2327 (2018).

Sharma, R. & Singhal, S. Photodegradation of textile dye using magnetically recyclable heterogeneous spinel ferrites. J. Chem. Tech. Biotechnol. 90, 955–962 (2015).

Ghobadi, M. Based on copper ferrite nanoparticles (CuFe2O4 NPs): catalysis in synthesis of heterocycles. J. Synth. Chem. 1, 84–96 (2022).

Liandi, A. R. et al. Recent trends of spinel ferrites (MFe2O4: Mn, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn) applications as an environmentally friendly catalyst in multicomponent reactions: A review. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 7, 100303 (2023).

Kefeni, K. K. & Mamba, B. B. Magnetic spinel ferrite nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization and catalytic application. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 19, 751–778 (2020).

Gingasu-Choghamarani, D., Mohammadi, M., Shiri, L. & Taherinia, Z. Structural and magnetic properties of MFe2O4 (M = Co, Ni, Zn) nanoparticles. J. Mater. Sci. 54, 12553–12571 (2019).

Sharma, R. et al. MgFe2O4 nanoparticles: A reusable catalyst for the synthesis of Hantzsch dihydropyridines and polyhydroquinolines. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 15, 2479–2490 (2018).

Borzooei, M., Norouzi, M. & Mhammadi, M. Nanomagnetic ZrFe2O4-Decorated porous silica sulfuric acid as an inorganic solid acid catalyst for synthesis of N-Heterocycles. Langmuir 41, 22419–22432 (2025).

Gharib, A., Pesyan, N. N., Fard, L. V. & Roshani, M. Catalytic Synthesis of α-Aminonitriles Using Nano Copper Ferrite (CuFe₂O₄) under Green Conditions. Org. Chem. Int. 1–8 (2014). (2014).

Sharma, S., Jakhar, P. & Sharma, H. CuFe2O4 nanomaterials: current discoveries in synthesis, catalytic efficiency in coupling reactions, and their environmental applications. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 70, 107–127 (2023).

Costa, A. F. et al. Síntese e caracterização de espinélios à base de ferritas com gelatina Como agente direcionador. Cerâmica 57, 352–355 (2011).

Swatsitang, E. et al. Characterization and magnetic properties of Cobalt ferrite nanoparticles. J. Alloys Compd. 664, 792–797 (2016).

Wang, X. W., Zhang, Y. Q., Meng, H., Wang, Z. J. & Zhang, Z. D. Perpendicular magnetic anisotropy in 70 Nm CoFe2O4 thin films fabricated on SiO2/Si(1 0 0) by the sol-gel method. J. Alloys Compd. 509, 7803–7807 (2011).

Qiu, W. et al. Efficient removal of Cr(VI) by magnetically separable CoFe2O4/activated carbon composite. J. Alloys Compd. 678, 179–184 (2016).

Zan, F. L. et al. Giant exchange bias and exchange enhancement observed in CoFe2O4-based composites. J. Alloys Compd. 581, 263–269 (2013).

Hosni, N., Zehani, K., Bartoli, T., Bessais, L. & Maghraoui-Meherzi, H. Semi-hard magnetic properties of nanoparticles of Cobalt ferrite synthesized by the co-precipitation process. J. Alloys Compd. 694, 1295–1301 (2017).

Wang, J., Deng, T., Lin, Y., Yang, C. & Zhan, W. Synthesis and characterization of CoFe2O4 magnetic particles prepared by co-precipitation method: effect of mixture procedures of initial solution. J. Alloys Compd. 450, 532–539 (2008).

Sreekala, G., Fathima Beevi, A., Resmi, R. & Beena, B. Removal of lead (II) ions from water using copper ferrite nanoparticles synthesized by green method. Mater. Today Proc. 45, 3986–3990 (2019).

Amulya, M. A. S. et al. Evaluation of bifunctional applications of CuFe2O4 nanoparticles synthesized by a sonochemical method. J Phys. Chem. Sol 148, 109756 (2021).

Farhadi, S. & Zaidi, M. Bismuth ferrite (BiFeO3) nanopowder prepared by sucrose-assisted combustion method: A novel and reusable heterogeneous catalyst for acetylation of amines, alcohols and phenols under solvent-free conditions. J. Mol. Catal. Chem. 299, 18–25 (2009).

Kafshgari, L. A., Ghorbani, M. & Azizi, A. Synthesis and characterization of manganese ferrite nanostructure by co-precipitation, sol-gel, and hydrothermal methods. Part. Sci. Technol. 37, 900–906 (2019).

Retizlaf, A., De Souza Sikora, M., Dias Teixeira, S., Zorel Junior, E. & Botteselle, G. H. Simultaneous synthesis and characterization of quinolinates to obtain Cobalt ferrite. Orbital: Electron. J. Chem 16, 176–181 (2024).

Retizlaf, A. et al. CoFe2O4 magnetic nanoparticles: synthesis by thermal decomposition of 8-hydroxyquinolinates, characterization, and application in catalysis. MRS Commun. 13, 567–573 (2023).

Fidelis, M. Z. et al. NiFe2O4–TiO2 magnetic nanoparticles synthesized by the thermal decomposition of 8-hydroxyquinolinates as efficient photocatalysts for the removal of As(III) from water. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 145, 114490 (2023).

Amini, M. et al. Spinel copper ferrite nanoparticles: Preparation, characterization and catalytic activity. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 32, e4470 (2018).

Yang, S. et al. An Ullmann C-O coupling reaction catalyzed by magnetic copper ferrite nanoparticles. Adv. Synth. Catal. 355, 53–58 (2013).

Nguyen, N. K. et al. Magnetically recyclable CuFe2O4 catalyst for efficient synthesis of bis(indolyl)methanes using Indoles and alcohols under mild condition. Catal. Commun. 149, 106240 (2021).

Swapna, K., Murthy, S. N. & Nageswar, Y. V. D. Magnetically separable and reusable copper ferrite nanoparticles for cross-coupling of Aryl halides with Diphenyl diselenide. Euro. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 1940–1946 (2011).

Sreedhar, B., Kumar, A. S. & Yada, D. CuFe2O4 nanoparticles: A magnetically recoverable and reusable catalyst for the synthesis of 5-substituted 1H-tetrazoles. Tetrahedron Lett. 52, 3565–3569 (2011).

Naeimi, H. & Didar, A. Facile one-pot four component synthesis of pyrido[2,3-d:6,5-d′]dipyrimidines catalyzed by CuFe2O4 magnetic nanoparticles in water. J. Mol. Struct. 1137, 626–633 (2017).

Maleki, A., Hajizadeh, Z. & Salehi, P. Mesoporous Halloysite nanotubes modified by CuFe2O4 spinel ferrite nanoparticles and study of its application as a novel and efficient heterogeneous catalyst in the synthesis of Pyrazolopyridine derivatives. Sci. Rep. 9, 5552 (2019).

Sahiba, N. & Agarwal, S. Recent advances in the synthesis of perimidines and their applications. Top. Curr. Chem. 378, 44 (2020).

Harry, N. A., Radhika, S., Neetha, M. & Anilkumar, G. A novel catalyst-free mechanochemical protocol for the synthesis of 2,3-dihydro-1H-perimidines. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 57, 2037–2043 (2020).

Mobinikhaledi, A. & Steel, P. J. Synthesis of perimidines using copper nitrate as an efficient catalyst. Syn React. Inorg. Metaorg Nanometal Chem. 39, 133–135 (2009).

Behbahani, F. K. & Golchin, F. M. A new catalyst for the synthesis of 2-substituted perimidines catalysed by FePO4. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 11, 85–89 (2017).

Khopkar, S. & Shankarling, G. Squaric acid: an impressive organocatalyst for the synthesis of biologically relevant 2,3-dihydro-1H-perimidines in water. J. Chem. Sci. 132, 31 (2020).

Abu-Melha, S. Confirmed Mechanism for 1,8-Diaminonaphthalene and Ethyl Aroylpyrovate Derivatives Reaction, DFT/B3LYP, and Antimicrobial Activity of the Products. J. Chem. 1–16 (2018). (2018).

Bassyouni, F. A. et al. Synthesis of new transition metal complexes of 1H-perimidine derivatives having antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activities. Res. Chem. Intermed. 38, 1527–1550 (2012).

Azam, M. et al. Physico-Chemical studies and antioxidant activities of transition metal complexes with a perimidine ligand. Z. Anorg Allg Chem. 638, 881–886 (2012). Syntheses.

Eldeab, H. A. & Eweas, A. F. A greener approach synthesis and Docking studies of perimidine derivatives as potential anticancer agents. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 55, 431–439 (2018).

Kalhor, M. & Zarnegar, Z. Fe3O4/SO3H@zeolite-Y as a novel multi-functional and magnetic nanocatalyst for clean and soft synthesis of imidazole and perimidine derivatives. RSC Adv. 9, 19333–19346 (2019).

Amrollahi, M. A. & Vahidnia, F. Decoration of β-CD-ZrO on Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles as a magnetically, recoverable and reusable catalyst for the synthesis of 2,3-dihydro-1H-perimidines. Res. Chem. Intermed. 44, 7569–7581 (2018).

Sadri, Z., Behbahani, F. K. & Keshmirizadeh, E. Synthesis and characterization of a novel and reusable adenine based acidic nanomagnetic catalyst and its application in the Preparation of 2-Substituted-2,3-dihydro-1H-perimidines under ultrasonic irradiation and Solvent-Free condition. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 43, 1898–1913 (2023).

Godoi, M. et al. Solvent-Free Fmoc protection of amines under microwave irradiation. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2, 746–749 (2013).

Walter, M. et al. Convenient and efficient N-methylation of secondary amines under solvent-free ball milling conditions. Sci. Rep. 14, 8810 (2024).

Rocha, M. S. T. et al. Regioselective hydrothiolation of terminal acetylene catalyzed by magnetite (Fe3O4) nanoparticles. Synth. Commun. 47, 291–298 (2017).

Tanaka, K. & Toda, F. Solvent-Free organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 100, 1025–1074 (2000).

Scheide, M. R. et al. Borophosphate glass as an active media for CuO nanoparticle growth: an efficient catalyst for selenylation of oxadiazoles and application in redox reactions. Sci. Rep. 10, 15233 (2020).

Catholico, N. et al. Waste glass tablets Cu (0) NP-Doped: an easily recyclable catalyst for the synthesis of propargylamines and nitrophenol reduction. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 13, 2943–2954 (2025).

Tornquist, B. L. et al. Ytterbium (III) Triflate/Sodium Dodecyl sulfate: A versatile recyclable and water-tolerant catalyst for the synthesis of Bis (Indolyl) methanes (Bims). ChemistrySelect 3, 6358–6363 (2018).

Moraes, C. A. O. et al. Urea hydrogen peroxide and Ethyl Lactate, an Eco-Friendly combo system in the direct C(sp2)–H bond selenylation of Imidazo[2,1-b]thiazole and related structures. ACS Omega. 8, 39535–39545 (2023).

Sousa, J. R. L. et al. KIO3-catalyzed selective oxidation of thiols to disulfides in water under ambient conditions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 22, 2175–2181 (2024).

Doerner, C. V. et al. Versatile electrochemical synthesis of Selenylbenzo [b] furans derivatives through the cyclization of 2-alkynylphenols. Front. Chem. 10, 880099 (2022).

Godoi, M. et al. M.G.M. Rice straw Ash extract, an efficient solvent for regioselective hydrothiolation of alkynes. Environ. Chem. Lett. 17, 1441–1446 (2019).

Santo, D. C. et al. IP-Se-06, a selenylated imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine, modulates intracellular redox state and causes Akt/mTOR/HIF-1α and MAPK signaling inhibition, promoting antiproliferative effect and apoptosis in glioblastoma cells. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 3710449 (2022). (2022).

Rafique, J. et al. Selenylated-oxadiazoles as promising DNA intercalators: Synthesis, electronic structure, DNA interaction and cleavage. Dyes Pigm. 180, 108519 (2020).

Botteselle, G. V. et al. Catalytic antioxidant activity of Bis-Aniline-Derived diselenides as GPx mimics. Molecules 26, 4446 (2021).

Santos, D. C. et al. Apoptosis oxidative damage-mediated and antiproliferative effect of selenylated imidazo[1,2-a]pyridines on hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells and in vivo. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 35, e22663 (2020).

Zhang, B., Li, J., Zhu, H., Xia, X. F. & Wang, D. Novel recyclable catalysts for selective synthesis of substituted perimidines and aminopyrimidines. Catal. Lett. 153, 2388–2397 (2022).

Sahiba, N., Sethiya, A., Soni, J. & Agarwal, S. Metal free sulfonic acid functionalized carbon catalyst for green and mechanochemical synthesis of perimidines. ChemistrySelect 5, 13076–13080 (2020).

Das, K., Mondal, A., Pal, D., Srivastava, H. K. & Srimani, D. Phosphine-Free Well-Defined Mn(I) Complex-Catalyzed synthesis of amine, Imine, and 2,3-Dihydro-1 H -perimidine via hydrogen autotransfer or acceptorless dehydrogenative coupling of amine and alcohol. Organometallics 38, 1815–1825 (2019).

Magee, R. The infrared spectra of chelate compounds—I A study of some metal chelate compounds of 8-hydroxyquinoline in the region 625 to 5000 cm– 1. Talanta 10, 851–859 (2002).

Shabaka, A. A., Fadly, M., Ghandoor, E., Kerim, F. M. & M. A. & A. IR spectroscopic study of some Oxine transition metal complexes. J. Mater. Sci. 25, 2193–2198 (1990).

Wang, X., Liu, L. & Shao, M. Photoswitch of a bundle of bis(8-hydroxyquinoline) nickel nanoribbons. Optoelectron. Adv. Mat. 5, 631–633 (2011).

Nagpure, I. M. et al. Synthesis, thermal and spectroscopic characterization of Caq2 (calcium 8-hydroxyquinoline) organic phosphor. J. Fluoresc. 22, 1271–1279 (2012).

Wagner, C. C., González-Baró, A. C. & Baran, E. J. Vibrational spectra of the Ga(III) complexes with Oxine and clioquinol. Spectrochim Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 79, 1762–1765 (2011).

Cheng, M. et al. Synthesis of a facile fluorescent 8-hydroxyquinoline-pillar[5]arene chemosensor based host-guest chemistry for Phoxim. Dyes Pigm. 194, 109646 (2021).

Yang, X. D. et al. Sonochemical synthesis and electrogenerated chemiluminescence properties of 8-hydroxyquinoline manganese (Mnq2) nanobelts. J. Alloys Compd. 590, 465–468 (2014).

la Calvo-de, J. Optimization of the synthesis of copper ferrite nanoparticles by a Polymer-Assisted Sol–Gel method. ACS Omega. 4, 18289–18298 (2019).

Salavati-Niasari, M. et al. Synthesis and characterization of copper ferrite nanocrystals via coprecipitation. J. Clust Sci. 23, 1003–1010 (2012).

Anandan, S. et al. Magnetic and catalytic properties of inverse spinel CuFe2O4 nanoparticles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 432, 437–443 (2017).

Amrollahi, M. A. & Ashayeri-Harati, F. Magnetic graphene oxide bearing ZrO2 as a new composite catalyst for the synthesis of 1 H -Perimidines. Org. Prep Proced. Int. 52, 282–289 (2020).

Mirjalili, B. B. F. & Imani, M. Fe3O4@NCs/BF0.2: A magnetic bio-based nanocatalyst for the synthesis of 2,3‐dihydro‐1 H ‐perimidines. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 66, 1542–1549 (2019).

Gharib, A., Noroozi Pesyan, N., Fard, V. & Roshani, M. L. Catalytic Synthesis of 훼-Aminonitriles Using Nano Copper Ferrite (CuFe2O4) under Green Conditions. Org. Chem. Int. 1–8 (2014). (2014).

Saha, M., Pradhan, K. & Das, A. R. Facile and eco-friendly synthesis of chromeno[4,3-b]pyrrol-4(1H)-one derivatives applying magnetically recoverable nano crystalline CuFe2O 4 involving a domino three-component reaction in aqueous media. RSC Adv. 6, 55033–55038 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES).

Funding

We gratefully acknowledge CNPq, and CAPES (001), for financial support. S.S., G.V.B., and J.R. would like to acknowledge CNPq (401355/2025-0, 316687/2023-5, 309975/2022-0, 404172/2023-7, 405655/2023-1, and 04172/2023-7) for the Scholarships. S.S., and J.R. also acknowledges the following FAPEG public calls: Chamada Pública FAPEG/SES Nº 18/2025 (ARB2025191000003), Chamada Pública FAPEG Nº 05/2025 (PVE2025041000055), and Chamada Pública FAPEG Nº 21/2025 (PEE2025331000083 and PEE2025331000108).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: G.V.B. and J.R.; Methodology: C.S., G.R.B., A.R., D.B.A., and P.A.; Validation: S.S. J.F.F., R.S., and G.C.; Formal analysis C.S., G.R.B., A.R., D.B.A., and P.A.; Investigation: C.S., G.R.B., A.R., D.B.A., and P.A.; Resources: S.S., G.V.B., and J.R.; Data curation: S.S. J.F.F., R.S., and G.C.; Writing - Original draft: G.V.B; Writing - Review & Editing: J.R.; Visualization: G.V.B. and J.R.; Supervision: G.V.B. and J.R.; Project administration: G.V.B. and J.R.; Funding acquisition: G.V.B. and J.R.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Siqueira, C., Borges, G.R., Retizlaf, A. et al. CuFe2O4 nanoparticles via thermal decomposition as recyclable magnetic catalysts for perimidine synthesis. Sci Rep 16, 2219 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31916-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31916-z