Abstract

Liquefaction is a severe earthquake-induced ground failure that reduces soil strength and foundation stability. This study examined the influence of fines content (FC) on soil liquefaction behaviour through field case histories and laboratory tests. According to many earthquake case histories of standard penetration test (SPT) blow counts, FC has an important significant effect on the liquefaction behaviour of soil. The SPT blow count was determined through 114 cyclic triaxial tests (CTT) and 37 cyclic hollow cylinder tests (CHCT) on Monterey Sand and Leyden Clay with varying FC (0%–45%), a method named “Conversion of Laboratory Test Results to SPT N-Blow Count” (LTRC-SPT) was developed to convert laboratory results into equivalent SPT blow counts. Results show that pure sand has the highest critical SPT N-value, which decreases as FC increases, but rises again after a threshold of about 25%. This highlights the special sensitivity of soils with 20%–30% FC in liquefaction analysis. Utilizing the results from CTT and CHCT tests, a back propagation neural network (BPNN) was employed to forecast SPT blow counts. This BPNN model demonstrates excellent accuracy, achieving a mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of just 1.95%. Additionally, it aids engineers in gaining a deeper insight into the liquefaction potential of soil samples with varying fines content.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soil liquefaction is a unique phenomenon in which soil loses its shear strength because the excess pore pressure of soil simultaneously increases under earthquake-induced dynamic loading. Seed, H.B. and Idriss, I.M. (1981)1 and Seed et al. (1985)2 evaluated the field liquefaction potential of soil with fines using a method correlating standard penetration test (SPT) N-blow counts with cyclic stress ratio (CSR).

During the 1976 Tangshan earthquake, the liquefaction resistance of silty soils in China was observed to rise as the fines content (FC) increased. According to Seed et al. (1985)2, there is a correlation between increased FC and enhanced liquefaction resistance, as evidenced by the relationship between cyclic stress ratio (CSR) and normalized standard penetration test (SPT) N-blow count.

The idea of the critical SPT N-value originated from the field test findings following the 1964 Niigata earthquake. The SPT results can be used to characterize the liquefaction behavior of soil in the field through the cyclic resistance ratio (CRR). Thereafter, the SPT N-value can express the resistance of sands to liquefaction. Seed and Idriss (1971)3 indicated that the relative density of soil samples can be derived from SPT results.

FC significantly influences the SPT N-value during the evaluation of the liquefaction resistance of soils (Seed, H. B., Idriss, I. M., and Arango, I., 19854; Ishihara, K., and Koseki, J. 19895; Koester, 19936; Hussain, M. and Sachan, A., 2019, 20207,8; Seed and Idriss, 19679, Polito et al. 202010, Gobbi et al. 202211.

Based on the values of SPT (N1)60, Idriss, I. M. (1999)12 noted that soil samples from case histories with fines content (FC) greater than 35% tend to increase the potential for soil liquefaction. Additionally, when the FC is below 5%, it has no significant impact on the liquefaction behavior of soils. Based on the relationships of CSR with (N1)60,CS, Cetin et al. (2018)13 showed that the values of the factor of safety (FS), corresponding to five different percentages of plastic limit (PL) (5%, 20%, 50%, 80%, 95%), were 1.5, 1.2, 1.0, 0.8, and 0.7.

Laboratory studies have been conducted to assess the impression of FC on the liquefaction potential of soil specimen. Many researchers assessed the liquefaction resistance of both undisturbed clean sands and soils containing fines in the laboratory (Liu H.C. and N.Y. Chang 199414,15; Park and Kim 201316; Ece E. Eseller-Bayat et al. 201917; Karakan E., Sezer A., Tanrinian N. 201918; Jungang Liu 202019; Ecemis, Nurhan 202020; A. F. Cabalar, S. Demir, and M. M. Khalaf 202121. Laboratory test results indicated that increases in FC either reduce the liquefaction resistance of soil until an FC threshold, after which the resistance increases.

Several early researchers were studied on the effects of standard penetration resistance (Gibbs and Holtz 195722; Meyerhof G.G. 195723; Skempton A.W. 198624; Schultze E & Menzenbach E. 196125; Cubrinovski.M. and Ishihara K, 199926, Polito et al. 202010, Gobbi et al. 202211. In the past few decades, the impact of FC on sand-fines’liquefaction resistance has sparked more interest in studies. Many field and laboratory test data are available worldwide. However, many data and associated conclusions in the technical literature are contradictory and how FC affects sand-fines’ liquefaction resistance remains unclear.

In this study, by analyzing field data from SPT-based case histories, including the studies of Idriss and Boulanger, (2008, 2010, 2014)27,28,29, SPT blow count was found to decrease with increasing FC, until reaching the lowest N-value, after which it increases with increasing FC.

The liquefaction potential for soils containing fines can be evaluated using CTT and CHCT. Based on the results of 114 CTTs and 37 CHCTs, a “LTRC-SPT” method was applied to calculate the SPT blow count. Its procedure involves deriving SPT N-values from laboratory parameters such as relative density, overburden pressure, and void ratio ranges, applying energy and stress corrections to obtain N60, and normalizing to (N1)60. By enabling laboratory results to be expressed in terms of equivalent SPT blow counts, the LTRC-SPT method bridges laboratory and field observations, enhances the reliability of liquefaction assessment for soils with fines contents of 5%−35%, and provides the analytical basis for subsequent statistical modeling presented in this paper.

In this research, 114 CTTs and 37 CHCTs were run for evaluating the impression of FC on the liquefaction behaviors of soil. This study presents a method for calculating the critical SPT blow count of soil samples with FC based on the results of the 151 laboratory tests. The liquefaction potential of sand with FC were compared against SPT blow counts from 325 global field case histories with the laboratory test results. Moreover, two statistical models are presented for predicting the liquefaction resistance of soils containing fines content. The goal is to develop a BPNN model that can predict the liquefaction resistance of soils with varying percentages of this delicate content.

Laboratory methods and test materials

All 151 laboratory tests were run to assess the influence of FC on liquefaction potential of soil, which is indicated by SPT blow count. Two different soil types, namely Monterey Sand and Leyden Clay (M-L), were used in both CTT and CHCT. To study the influence of FC on the calculation of the SPT blow count of soils, soil samples with different FC percentages (ranging from 0% to 45%) were used.

Figure 1 shows the applied stresses on a typical triaxial sample. At a selected CSR under the frequency at 0.5 Hz, cyclic stress, strain, and pore pressure were recorded in 114 laboratory tests. In a CTT, a cylindrical soil sample wrapped in a rubber membrane was positioned inside a chamber. It was then subjected to confining fluid and back pressure, followed by axial loading until it failed. Each soil sample was saturated using back pressure. The sample was considered fully saturated when the Skempton pore pressure parameter, B, was equal to or exceeded 0.95.

The hollow cylinder testing equipment was developed and built based on the design of the hollow cylinder cell from Imperial College (Hight, D.W. 198330, Jing-When Chen, 198831, Jungang Liu, 201932, Jungang Liu and Geng Chen, 202233 at the University of Colorado Denver (UCD). Figure 2 shows the schematic illustration of the CHCT device. At a selected CSR under the frequency at 0.5 Hz, cyclic shear stress, cyclic strain, and excess pore pressure were recorded in 37 CHCT tests.

A hollow cylindrical soil sample was surrounded by both an inner and outer membrane. This setup allows for effective stress to be applied independently to each of the inner and outer chambers, enabling control over the inner and outer pressures, whether equally or unequally. Axial load and torque were applied to the top of the specimen, transmitted through either a top cap or a pedestal.

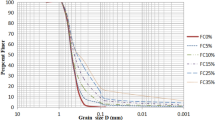

The soil sample in the CHCT was prepared with FC (5%, 10%, 15%, 25%, and 35%) and a constant plastic index (20%). The grain size allocation splines for soil samples with five diverse FC are shown in Fig. 3. The CTT test was conducted with six different FC percentages (5%, 10%, 15%, 25%, 35%, and 45%) and 20% of the plastic index.

The control of soil sample density is the most important and difficult process in the laboratory method. During sample preparation, void ratios were used for checking soil sample density. The Monterey sand sample, categorized as SP according to the Unified Soil Classification System, is a consistent research sand sourced from Monterey, California. Several properties of this sand were assessed and are detailed in Table 1. Laboratory testing was conducted in general accordance with ASTM International (ASTM) designations D3080-04(2012)34, D698 (2012b)35, and D854 (2014)36.

Leyden Clay from Golden, Colorado, which is classified as medium clay (CL) under USCS, was used for CTT and CHCT. Some properties of Leyden Clay were assessed, and the test results are presented in Table 2. Leyden clay was passed through a #200 sieve to eliminate any impurities. Laboratory testing was run in agreement with ASTM International (ASTM) designations D3080-04(2012)34, D698 (2012b)35, and D854 (2014)36.To clearly distinguish the independent effects of fine particle content (FC) and fine particle type/plasticity on the liquefaction resistance, in all the re-prepared samples, the plasticity index (PI) was consistently controlled at 20 (as shown in Table 2). The purpose of this control variable was to separately examine the influence of FC on the pore structure, permeability and pore pressure generation behavior of the samples under as consistent plastic conditions as possible.

Laboratory test results

In this study, the results of all 151 laboratory test results were used to calculate the SPT (N1)60 blow count by following the steps described in the previous section.

Calculation of (N1)60 by using CTT and CHCT results

The calculation of (N1)60 using soil samples with fines from laboratory test results involves six steps.

Step 1: Calculate N values.

(a) For sandy soil:

Meyerhof G.G. (1957)23 noted that the SPT N value is associated with the relative density of sand and the effective overburden pressure

where N denotes the SPT blow count, σ’v refers to the effective overburden pressure in kilopascals (kPa), and Dr is the relative density expressed as a ratio instead of a percentage.

(b) For soil species with FC:

For soil samples with fines, emax and emin can be used to describe the FC percentage. The correlation between the SPT N value and Dr is derived using the following equation by Cubrinovski M. and Ishihara K. (1999)26.

where Dr is defined as a ratio and σ ‘v is given in kPa. SPT blow count is equal to the percentage energy of 78%.

Step 2 (for soil species with FC): Determine connection between max&min values of void ratio and FC:

Cubrinovski M. and Ishihara K. (1999)26demonstrated the association between the void ratio range (emax and emin) and FC, as shown in Fig. 4. The equation they proposed describes the relationship among the maximum void ratio (emax), minimum void ratio (emin), and FC.

Relationship between void ratio range and fines content for soil samples. (Cubrinovski M. and Ishihara K. 199926.

Step 3: Calculate N60.

The equation, which ERr is stand for rod energy ratios, below shows that N60 is calculated by using the values of N.

Step 4: Calculate (N1)60.

Liao and Whitman (1986) indicated that (N1)60 can be determined by using overburden pressure. The (N1)60 blow count can be calculated as:

where σv’ is vertical effective stress.

Calculating (N1)60 by using CTT results

A total of 96 CTTs were performed on the uniform Monterey Sand, utilizing six different percentages of FC: 5%, 10%, 15%, 25%, 35%, and 45%, along with a plasticity index 20. Additionally, 18 CTTs were carried out on the consistently clean Monterey Sand. CSR can be calculated as in

Where σdc is deviator stress, σa is normal stress.

As shown in Fig. 5, the soil sample prepared in a CTT at a 30% relative density had the highest calculated (N1)60 when the percentage of fine material was zero. When FC reached the threshold level of 25%, the calculated (N1)60 began to decline. However, the calculated (N1)60 began to increase at 35% FC. Figures 6 and 7 show the decrease of calculated (N1)60 with increasing FC under relative densities of 45% and 60% in the CTT.

The calculation of (N1)60 vs. CSR in a CTT with Dr = 30% and a consolidation pressure of 103 kPa with varying FC is shown in Fig. 8 (a). In the CTT, three distinct CSRs of 0.2, 0.3, and 0.4 were used. Under these CSRs and a consolidation pressure of 103 kPa, clean sand exhibited the highest calculated (N1)60. For all laboratory testing under the applied CSR of 0.2, 0.3, and 0.4, the soil specimens reached liquefaction, with the number of cycles to liquefaction varying depending on CSR and fines content. Correspondingly, excess pore water pressure developed at different rates across the tests. In Fig. 8 (a), the line representing a 25% FC is situated on the right side of the curve. However, the line of 35% FC appeared between the lines of 15% and 25% FC. This indicates that under the three CSRs, the lowest (N1)60 occurred at 25% FC.

The calculation of (N1)60 vs. CSR in the CTT at Dr = 30% under the consolidation pressure of 207 kPa with various FCs is shown in Fig. 8 (b). All lines with various FCs are located in positions similar to those in Fig. 8(a). In the CTT, the lowest calculated (N1)60 was observed at 25% FC. The calculated (N1)60 vs. CSR at Dr = 45% in consolidation pressures (103 kPa and 207 kPa) with various FCs is shown in Figs. 9(a) and 9(b). Samples with 5% FC are consistently distributed on the right aspect of splines and produced the highest (N1)60. Both data points show that calculated (N1)60 decreased as the FC percentage increased. According to these findings, calculated (N1)60 increases with increasing relative density.

Figures 10(a) and 10(b) show the calculated (N1)60 vs. CSR at Dr = 60% in consolidation pressures (103 kPa and 207 kPa) with varying FCs. The results of soil samples, which prepared under two difference relative densities of 30% and 45%, were the same. In Figs. 8, 9 and 10, the CSR-(N1)60 curves for a given fines content appear nearly constant across different CSR levels. This is because all soil specimens reached liquefaction under the applied CSRs, but the number of cycles to liquefaction varied with CSR and fines content. Higher CSR values led to faster pore pressure buildup and fewer cycles to liquefaction, while lower CSR values required more cycles. Thus, the calculated (N1)60 remained similar for different CSR levels at the same fines content, which explains the apparent flatness of the curves.

Calculating (N1)60 by using CHCT results

On the homogeneous Monterey Sand with five different FC percentages (5%, 10%, 15%, 25%, and 35%) and plasticity index 20, twenty CHCTs were carried out. On the consistent clean Monterey Sand, seventeen CHCTs were conducted. CSR can be calculated as in

Where τh is cyclic shear stress, σv’ is effective stress.

The findings of the CHCT were used to calculate (N1)60, which showed a correlation between (N1)60 and various FC percentages. Figure 11 shows a trend that resembles the results of the CTT with relative density set at 30%. The greatest values for the calculated (N1)60 in Fig. 12 were about 20 at 0% FC. After increasing the FC, the value of the calculated (N1)60 began to decline.

The trend line (R2 = 0.9531) in Fig. 13 shows the correlation between (N1)60, computed from the results of tests using cyclic hollow cylinders and cyclic triaxial materials, with varying FC levels. Figure 13 shows the results of two laboratory tests using soil samples that were treated at Dr = 30% and had varying FC percentages. Although the two datasets were derived from two separate sets of laboratory test results, the curves indicate the same general pattern. Both datasets showed that the computed (N1)60 value was the highest for clean FC. Both splines indicated that the calculated (N1)60 decreases with increasing FC, however passing 25% FC, the SPT blow count begins to rise.

Figure 14 (R2 = 0.9669) shows the results of CTT and CHCT conducted on soil samples which were prepared at Dr = 60% with varying FC percentages. Similar to Fig. 13, both curves exhibit the same pattern. Both datasets showed that the computed (N1)60 value was the highest for clean FC. Both splines indicated that (N1)60 decreases with increasing FC, whereas passing 25% FC, the SPT blow count begins to rise. In the Fig. 15, it shows that soil sample, prepared at Dr = 30% and 60%, have a relationship between (N1)60 and CSR from CHCT under a Consolidation Pressure (103 kPa and 207 kPa) with Different fines contents.

Fines content versus SPT blow count based on case histories

Idriss and Boulanger, (2008, 2010, 2014)27,28,29 showed that out of 230 case histories based on individual SPT-based liquefaction data, 115 cases involved liquefaction and 112 cases did not involve liquefaction. It is noteworthy that correction factors CE, CR, CB, and CS and Nm, σv, σv’, and crucial depth were applied. They further analyzed 115 instances with surface signs of liquefaction and revealed a connection compare corrected (N1)60 with different FC, as shown in Fig. 16. The figure shows the considerable propensity for soil liquefaction when (N1)60 is less than 30. In general, the particulate fines content of the soil was less than 35% and the SPT blow count was less than 25. In particular, only 11 instances of liquefaction were observed in soil with a fine concentration of 50–90%.

Table 3 presents averages of (N1)60 and CSR for FC percentages ranging from 0% to 25%. The average of (N1)60 and various FC percentages in the case history database are related.

The trend line in Fig. 17 illustrates the correlation between FC and an average of (N1)60 (R2 = 0.8673). As shown in the figure, the maximum (N1)60 was found in clean FC, and (N1)60 decreased with increasing FC. Beyond 15%, a rise in FC results in an average of (N1)60.

Tokimatsu K. and Yoshimi Y. K., (1983)37 analyzed 95 case history datasets, which included more than 70 from Japan and about 20 from outside of Japan, including SPT N1 (energy rod ratio of 78%), calculated CSR, FC, and ten other parameters. Among them 52 cases involved liquefaction, 33 cases involved no liquefaction, and 10 cases involved a state between liquefaction and no liquefaction. Figure 18 presents the decrease of SPT blow count N1 with FC ranging from 0% to 65% across all 52 case datasets, indicating the occurrence of liquefaction at an N1 < 20. Additionally, in 80% of the databases, the particulate content of the soil was less than 35% and the SPT blow count was less than 20. The figure also shows that liquefaction occurred in only 7 examples where soil with particle concentrations ranged from 40% to 65%. It should be noted that only liquefied cases were considered in Figs. 16 and 18, because the scope of this study is limited to liquefaction-triggering conditions. Non-liquefaction cases were not included in the present analysis and will be addressed in future work to provide a more comprehensive assessment.

Table 4 displays the mean values of N1, mean (no highest and lowest values) of N1, mean values of CSR, and mean (no highest and lowest values) of CSR for four various FC percentages (0%, 5%, 10%, and 20%).

Figure 19 shows two sets of data: one is the average values of N1 with varying FC percentages, and the other is the average values of N1 (no highest and lowest values). Both datasets showed similar curves. The curve in Fig. 19 resembles the track in Fig. 17 by Idriss and Boulanger, (2008)27 in terms of form. The trend line (R2 = 0.9503) in Fig. 19 depicts the correlation between FC and average N1. The largest N1 value was observed for clean FC at 13.5. N1 decreases with increasing FC until reaching 10% FC. Thereafter, N1 is anticipated to increase with increasing FC. According to Figs. 20 and 21, the clean FC has the highest SPT N value, and soil with 10% FC has the smallest SPT N value.

Average values of (N1), average values (nohighest&lowest) of (N1) versus FC (ranged from 0% to 20%) from case histories by Tokimatsu and Yoshimi37.

The link between the averages values of CSR and the mean values of (N1) with FC (0%, 5%, 10% and 20%) is shown in Fig. 22. Similar results can be observed between Figs. 23 and 24, in that the SPT blow count attributable to earthquakes and the average of earthquake-induced CSR are both reduced at 10% FC.

Average Values of Earthquake-induced CSR vs. Average Values of N 1 with FC (ranged from 0% to 20%) from Case Histories by Tokimatsu and Yoshimi37.

Figure 20 shows two SPT-based case history datasets from Idress et al. (2008, 2010, 2014)27,28,29 and Yoshimi et al. (1983)37. Although the threshold FC differed between the two databases (10% in one and 15% in the other), both curves follow the same pattern. In both databases, clean fine material consistently had the highest SPT blow count values. Case studies by several researchers revealed that (N1)60/N1 decreased as the proportion of particulate fines content increased. After the threshold FC, (N1)60/N1 began to rise as FC rose.

Predicting SPT blow counts using back propagation neural network (BPNN)

The diagram illustrating the machine learning model is depicted in Fig. 23, featuring Back Propagation Neural Networks (BPNNs) that consist of input, hidden, and output layer components, as represented in Fig. 25.

The input layer included four parameters closely related to SPT blow counts: Relative Density (Dr in %), Fines Content (Fc in %), Deviator Stress (Ds in kPa), and the Number of Cycles to Liquefaction (No.).

The BPNN model developed in this study was based on a detailed database comprising 108 instances. The soil samples are classified into three different target relative densities (Dr%): 30%, 45%, and 60%. Each sample consists of Monterey No. 0/30 Sand mixed with varying percentages of fine content (Fc%): 0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, 25%, and 35%. The number of cycles to liquefaction (No.) varies between 3 and 1500, while the deviator stress (Ds) ranges from 4.5 kPa to 24 kPa.

The dataset was split into two parts: a training set for developing the BPNN model and a validation set for evaluating its performance. In this study, 80% of the data was designated for the training set, with the remaining 20% reserved for validation. The BPNNs were generated using a MATLAB program, and the program page is shown in Fig. 21.

This study explored various configurations for the number of neurons in model training, specifically using 1, 2, 4, and 8 neurons. Figure 24 displays the regression plots for the training, test, and overall datasets, along with their respective R-squared values.

It was noted that using four neurons in the hidden layer resulted in a highly accurate trained model that closely approximated the true values, with R-squared values nearing one. When the number of neurons was increased from 1 to 2, the R values for the validation set decreased from 0.97459 to 0.99379. Additionally, the R value for the test set was 0.99885 (Fig. 24(c)), demonstrating that the BP neural network model performed well on unseen data. However, when the number of neurons increased from 4 to 8, the R values for the validation set dropped from 0.99885 to 0.99375, indicating issues with overfitting. Therefore, the optimal choice was to utilize four neurons in the hidden layer.

The plot depicting the validation performance of the BP neural network model with mean squared error (MSE) is shown in Fig. 26. Initially, both the training and validation sets exhibited high MSE values throughout the early stages of training. However, these values progressively decreased, suggesting that the BPNN model effectively learned the correlation between inputs and outputs. The optimal training performance was achieved by the BPNN at the ninth epoch, yielding an MSE of 0.0043665.

The anticipated SPT blow counts, derived from the results of CTT and CHCT tests, are shown in Fig. 27, reflecting a strong correlation with the actual values. To assess the effectiveness of the BPNN model, we calculated the root mean squared error (RMSE) and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) as evaluation metrics for this study, using the following formulas:

Where n represent the total numbers of the samples, ei and pi denote the actual and predicted outputs, respectively.

It is important to note that any developed or proposed model is only effective within the constraints of the input parameters defined by the limitations of the database. This underscores the necessity of ensuring that input data used in practical applications stays within these defined boundaries. Additionally, the BPNN model developed in this study is primarily aimed at predicting SPT blow counts, utilizing four neurons in the output layer, without considering the complete testing results curves.

The testing results curves provide valuable insights, particularly regarding the connection between fine content and calculated SPT blow counts, as well as the cyclic stress ratio with these counts. Therefore, it is crucial to incorporate BP neural network and random forest algorithms in future research to predict the complete testing results curve.

Discussion

In this research, two sets of field case history data were selected. One set was from Idriss and Boulanger, (2008, 2010, 2014)27,28,29, which contains 230 case histories from many earthquakes worldwide. The other was from Yoshimi et al. (1983)37, which includes 95 case histories, with more than 70 from Japan and about 20 from outside of Japan. The two sets of field test data indicated that the clean sand had the highest value of (N1)60 /N1(Fig. 28). The value of (N1)60 decreased with increasing FC percentage, but after passing the threshold FC, it tended to increase.

All laboratory test results indicated that calculated (N1)60 decreases with increasing FC up to a threshold. Based on four different sets of SPT N-blow counts, two sets from earthquake histories and another two sets from laboratory test results, Fig. 28 shows that the largest SPT blow counts were observed in soil without fines. According to case histories, the threshold FC ranges from 10% to 25%. Regarding to soil specimens prepared at Dr = 30% and 60% in the laboratory results of CTT and CHCT, calculated (N1)60 decreases with increasing FC until the threshold, ranging from 25% to 35%.

Figure 28 shows that soils with FC from 10% to 15% had the smallest number of (N1)60 / N1. For assessing the field liquefaction potential of soils with fines content, Fig. 28 had to be suggested. This figure incorporates not only SPT blow counts from more than 300 case history datasets covering over 100 earthquakes from all around the world, but also (N1)60 calculation results from 114 CTTs and 37 CHCTs.

This paper indicates that 77 additional CTTs are required compared to CHCTS to assess the liquefaction potential of soils with fines content. The distribution of stresses and strains in the CHCT sample is generally more uniform than that in the cyclic triaxial test (CTT), making CHCT a superior method for assessing soil liquefaction resistance. Nonetheless, CTT is more commonly used due to its ease of implementation. CHCT can also calibrate the liquefaction resistance obtained from CTT and determine the reduction factor needed to translate CTT results into cyclic simple shear conditions. While CTT is favored for production purposes, CHCT is utilized for quality control. Both testing methods offer unique advantages for evaluating the liquefaction resistance of soils.

The case history results from Niigata City exhibit similarities to those depicted in Fig. 22. However, they have limitations, as they do not present the liquefaction resistance of samples with FC percentages ranging from 15% to 35%. Karakan E., Sezer A., and Tanrinian N., (2019)18 indicated that volume changes in silt due to the reconsolidation after cyclic loading with an induced pore water pressure ratio (Ru) less than 50% leads to limited liquefaction.

Geotechnical engineers should always take field testing and laboratory testing results to make go/no-go decisions for many practical problems and also determine the suitability of soil models. Therefore, the proposed “Conversion of Laboratory Test Results to SPT N-Blow Count (LTRC-SPT)” method for calculating SPT N-blow count has high potential applicability as a bridging method for determining liquefaction resistance from laboratory test results to field test results. This procedure should be used to assess liquefaction potential of soil with FC ranging from 5% to 25%. In particular, more attention should be paid to soil with different FC percentages for evaluating liquefaction potential.

This paper details the process of calculating SPT blow count (N1)60, which is related to the effective overburden pressure, soil relative density, FC, and maximum and minimum void ratios of soil samples. This method is based on the results of CHCT and CTT.

In Fig. 29, the linear equation can describe the six curves based on data from SPT case histories and laboratory test results. The linear equation is

The linear equation can be used to not only predict the relationship between FC and SPT blow counts, but also forecast the liquefaction resistance of soil samples with FC. By using the SPT (N1)60 calculation method, deeper engineering knowledge on the liquefaction potential of soils containing fine particles can be gained. R²=0.94 of linear equation demonstrated that the empirical relationship between FC and (N1)60 can be well represented, enabling improved prediction of liquefaction resistance across both laboratory and field conditions.

Although two distinct types of soils were employed in the calculation of SPT blow count (N1)60, Monterey sand is still a fairly common research soil sample in liquefaction resistance investigations. The SPT N-blow count is a popular parameter for evaluating the liquefaction resistance of soils, especially for the field liquefaction potential. One of reasons is that data on SPT N-blow counts are easier and less expensive to obtain in the field tests, compared to laboratory methods. However, the classification of soil specimens from SPT tests remains slightly difficult and less accurate, especially regarding the FC percentages of specimens. The laboratory method for evaluating soil liquefaction potential is the most significant approach because soil types and resistances can be described more accurately in the laboratory. Although the results of SPT N-blow counts may provide basic soil information, field and laboratory methods can be combined to achieve suitable predictions for assessing soil with fines’ liquefaction potential, as presented in this paper (Fig. 28).

This study introduces a BPNN model that provides more accurate predictions of SPT blow counts and evaluates the liquefaction potential of soil samples. It takes into account various factors, including relative density (Dr in %),fines content (Fc in %), deviator stress (Ds in kPa), and the number of cycles to liquefaction (No.).

The plasticity index (PI) significantly modulates the above mechanisms by altering the deformation and drainage properties of fines. On the one hand, fines with higher PI (more clay-like) generally exhibit lower permeability, higher cohesion/plastic resistance, and greater volumetric constraint, all of which help suppress rapid pore pressure accumulation during earthquakes and thereby enhance liquefaction resistance. On the other hand, fines with low PI are more prone to particle rearrangement and provide limited resistance under cyclic loading, thus accelerating pore pressure buildup and reducing resistance. Since all specimens in this study were prepared with PI fixed at 20, the reported trends reflect the influence of FC under moderate-plasticity conditions. Different PI values could shift the threshold position and alter the slope of the resistance curve. The process can be viewed in Fig. 28.

This study is based on a limited range of soil types, relative densities, and laboratory conditions. The correlations proposed herein should be further validated using additional field data and a broader range of soil compositions.

Conclusion

In this study, field and laboratory methods for analyzing liquefaction potential and the influence of FC on the liquefaction resistance of soils were investigated. The standard penetration test (SPT) blow counts not only include more than three hundred case histories from over 100 earthquakes, but could also be used to calculate SPT blow counts using laboratory test results. One hundred fourteen isotropically consolidated undrained CTTs and thirty-seven CHCTs were performed on soil samples with different FC percentages to investigate the liquefaction resistance of soil samples.

The following conclusions can be drawn from the results of this study:

-

(1)

The analysis of earthquake histories and laboratory test results revealed that pure sand has the highest number of (N1)60, and (N1)60 decrease with increasing FC. After passing the threshold FC, the (N1)60 begins to increase. The threshold FC is anticipated to occur when soil behavior transitions from sand-dominated to fine-dominated. In this study, the threshold FC based on case history data ranged from 10% to 25%, and that based on laboratory tests ranged from 25% to 35%.

-

(2)

This study presents a LTRC-SPT method based on CTT and CHCT for calculating (N1)60, which is related to the effective overburden pressure, relative density, FC, and maximum and minimum void ratios.

-

(3)

For assessing the liquefaction potential of soils with fines content in the field, the results from SPT case histories and laboratory tests should be recommended. In particular, soils with FC ranging from 10% to 35% should be used in field and laboratory methods to evaluate liquefaction potential.

-

(4)

The applicability of existing codes provisions and models was evaluated through an experimental database. To enhance accuracy, a BPNN model was developed for predicting cyclic stress ratio leading to initial liquefaction after cyclic loading cycles. The findings demonstrated that this BPNN model exhibited superior precision and efficiency compared to conventional models, with MAPE values of 1.95%, respectively.

Data availability

All data, models, and code generated or used during the study appear in the submitted article.The data was accessed on the website https://kdocs.cn/l/ceU8cy1qCAnm.

References

Seed, H. B. & Idriss, I. M. Evaluation of Liquefaction Potential Sand Deposits Based on Observation of Performance in Previous Earthquakes 481–544 (ASCE National Convention (MO), 1981).

Seed, H. B., Tokimatsu, K., Harder, L. F. & Chung, R. M. Influence of SPT procedures in soil liquefaction resistance evaluations. J. Geotech. Engrg ASCE. 111 (12), 1425–1445 (1985).

Seed, H. B. & Idriss, I. M. Simplified procedure for evaluating soil liquefaction potential. J. Soil. Mech. Found. Div. ASCE. 97 (9), 1249–1273 (1971).

Seed, H. B., Idriss, I. M. & Arango, I. Evaluation of liquefaction potential using field performance data. J. Geotech. Engrg ASCE. 109 (3), 458–482 (1985).

Ishihara, K. & Koseki, J. Cyclic shear strength of fines-containing sands. Earthquake and Geotech. Engrg., Japanese Society of Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering, Tokyo, 101–106 (1989).

Koester, J. P. Effects of fines type and content on liquefaction potential of low-to-medium plasticity fine-grained soils. Proc., 1993 Nat. Earthquake Conf., Central United States Earthquake Consortium, Memphis, Tenn., 1, 67–75 (1993).

Hussain, M. & Sachan, A. Dynamic characteristics of natural Kutch sandy soils. Soil. Dynamics Earthq. Eng. Elsevier. 125, 105717 (2019).

Hussain, M. & Sachan, A. Dynamic behaviour of Kutch soils under Cyclic triaxial and Cyclic simple shear testing conditions. Int. J. Geotech. Eng. Taylor Francis. 14 (8), 902–918 (2020).

Seed, H. B. & Idriss, I. M. Analysis of soil liquefaction: Niigata earthquake. J. Soil. Mech. Found. Div. ASCE. 93, 83–108 (1967).

Polito, P. et al. Threshold fines content and the behavior of sands with Non-Plastic silts. Can. Geotech. J. 57, 462–465 (2020).

Gobbi et al. Liquefaction assessment of silty sands: experimental characterization and numerical calibration. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 159, 107349 (2022).

Idriss, I. M. An update of the Seed-Idriss simplified procedure for evaluating liquefaction potential. Presentation notes for Transportation Research Board Workshop on new approaches to liquefaction analysis, Washington, D.C (1999).

Cetin, K. O. et al. S SPT-based probabilistic and deterministic assessment of seismic soil liquefaction triggering hazard. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 115, 689–709 (2018).

Liu Hsing-Cheng and Nien-Yin Chang. Statistical Modeling of Liquefaction Resistance of a uniform Fine Sand Containing Plastic Fines Fifth U.S. National Conference on Earthquake Engineering, 251–260. (1994).

Nien-Yin & Chang Liu Hsing-Cheng and A Procedure for Evaluating IN-SITU Liquefaction Resistance of a uniform Fine Sand with Plastic Fines Inclusion Fifth U.S. National Conference on Earthquake Engineering, 261–270 (1994).

Park, S. S. & Kim, Y. S. Liquefaction resistance of sands containing plastic fines with different plasticity. J. Geotech. GeoEnviron. Eng. 139 (5), 825–830 (2013).

Ece, E., Eseller-Bayat, M. & Murat Monkul Özge akin & Senay Yenigun the coupled influence of relative Density, CSR, plasticity and content of fines on Cyclic liquefaction resistance of sands. J. Earthquake Eng. 23 (6), 909–929 (2019).

Karakan, E., Sezer, A. & Tanrinian, N. Evaluation of effect of limited pore water pressure development on cyclic behavior of a nonplastic silt . Soils and Foundations 59(5), 1302–1312 (2019).

Jungang Liu. Influence of fine contents on Soil Liquefaction Resistance in Cyclic Triaxial Test Geotech Geol Eng. 38:4735–4751 (2020). (2020).

Ecemis, N. Effect of Soil-Type and fine content on liquefaction Resistance—Shear-Wave velocity correlation. J. Earthquake Eng. 24;8, 1311–1335 (2020).

Cabalar, A. F., Demir, S. & Khalaf, M. M. Liquefaction resistance of different Size/Shape Sand-Clay mixtures using a pair of Bender Element–Mounted molds. J. Test. Eval. 49, 1509–1524 (2021).

Gibbs, H. J. & Holtz, W. G. Research on Determining the Density of Sands by Spoon Penetration Testing Proceedings, 4th International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, Vol1, pp129-132 (1957).

Meyerhof, G. G. Discussion on research on determining the density of sands by penetration testing. Proc. 4th Int. Conf. on Soil Mech. and Found. Engrg. 1, 110 (1957).

Skempton, A. W. Standard penetration test procedures and the effects in sands of overburden pressure, relative density, particle size, ageing and over consolidation. Geotechnique 36 (3), 425–447 (1986).

Schultze, E. & &Menzenbach, E. Standard penetration test and compressibility of soils.. Proc. 5th Int. Conf. Soil Mech. Fdn Engng. 1, 527–532 (1961).

Cubrinovski, M. & Ishihara, K. Empirical correlation between SPT N-value and relative density for sandy soils. Soils Found. 39 (5), 61–71 (1999).

Idriss, I. M. & Boulanger, R. W. Soil liquefaction during earthquakes. Monograph MNO-12 (Earthquake Engineering Research Institute, 2008).

Idriss, I. M. & Ross, W. Boulanger. SPT-based liquefaction triggering procedures, Report No. UCD/CGM-10-02 University of California Davis, California December (2010).

Idriss, I. M. & Boulanger, R. W. CPT and SPT based liquefaction triggering procedures. In Report No. UCD/CGM-14/01, Center for Geotechnical Modeling 134 (Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of California, 2014).

Hight, D. W. Laboratory investigations of sea bed clays PH.D. Thesis, University of London (1983).

Jing-Wen & Chen Stress Path Effect on Static and Cyclic behavior of Monterey No. 0/ 30 Sand Ph.D dissertation, University of Colorado Denver (1988).

Jungang, Liu & Thesis Liquefaction Resistance of Monterey No. 0/30 Sand Containing Fines under Cyclic Triaxial and Cyclic Hollow Cylinder Tests PH.D. University of Colorado, Denver (2019).

Jungang Liu and Geng Chen The correction factor of Monterey No. 0/30 sample with fine content liquefaction resistance between Cyclic triaxial and Cyclic Hollow cylinder tests. Sci. Rep. 12, 15927 (2022).

ASTM International. Standard Practice for Thin-Walled Tube Sampling of Soils for Geotechnical Purposes (D1587-08 (Reapproved 2012) (ASTM International, 2012).

ASTM International. standard test methods for laboratory compaction characteristics of soil using standard effort (D698-12). West Conshohocken (ASTM International, 2012b).

ASTM International. standard test methods for specific gravity of soil solids by water pycnometer (D854) (ASTM International, 2014).

Tokimatsu, K. & Yoshimi, Y. K. Empirical Correlation of Soil liquefaction Based on SPT-N-Value and fine content. Soil. Foundation JSSMFE 23, 56–74 (1983).

Funding

This paper is supported by Guangxi Science and Technology Program (Project No. AD25069101); Hubei Provincial Department of Housing and Construction (202341); Research Program of Hubei Polytechnic University (Grant Nos. 23xjz01A, KY2024-139); the General Projects of Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant Nos. 2025AFB935); Hubei Talent Project of Chutian Scholars, Hubei Key Talent Plan“Hundred People Plan”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kongjian Li: writing and revision, and data analysis; Jungang Liu: methodology and conceptualization; Chunmei Mu: writing—original draft, and result interpretation; Yi Zhang: formal analysis and data collection Lingxin Ge.:software and experiment execution;

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, K., Liu, J., Mu, C. et al. Effect of fines content on liquefaction resistance of soil using laboratory test and SPT. Sci Rep 16, 2135 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31917-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31917-y