Abstract

Fluorescence-based optical techniques have significantly advanced our comprehension of living systems, providing invaluable insights into cellular intricacies and facilitating fundamental research and practical diagnostic applications. To explore intracellular environments and the communication among intracellular organelles, we utilized fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy with exogenous fluorophores of Oregon Green 488 BAPTA-1 AM and Fluovolt and endogenous fluorophores of NAD(P)H and FAD in breast carcinoma MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 and normal MCF10A cells. Fluorescence lifetime images have uncovered a characteristic triangular interrelationship among intracellular calcium ion concentration (Ca2+), mitochondrial function, and membrane electric potential in cancerous and normal cells. To delve deeper into the effects of electric field stimulation on intracellular conditions, the nanosecond pulsed electric field (nsPEF) was applied to the breast cancerous and normal cells. Our findings revealed a unique electric field modulation pattern across breast cells; MCF7 cells exhibited initial modulation in cytosolic Ca2+ levels, followed by changes in mitochondrial function, whereas MDA-MB-231 and MCF10A cells mostly remained unaffected, demonstrating that intracellular conditions and the effect of nsPEF are different not only between cancerous and normal cells but also between subtypes of cancerous cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cells rely on intricate signaling pathways to coordinate their functions within and between themselves, maintaining the health of an organism1,2. In normal cells, these signaling processes are precisely regulated through the communication among plasma membrane electric potential (Vm), Ca2+ ion flow, and cellular metabolism. The Vm controls the flow of ions to maintain the cell’s electrical balance. Ca2+ acts as a secondary messenger, and its intracellular levels are tightly controlled3,4. Ca2+ ions are released through specific channels to orchestrate cellular processes, including metabolic function. Emerging evidence indicates that cancerous cells often exhibit disrupted Ca2+ homeostasis, leading to abnormal Ca2+ distribution and signaling5,6. Additionally, altered mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in cancerous cells contributes to their metabolic rewiring and increased reliance on glycolysis7,8,9. The different Ca2+ regulation between normal and cancerous cells profoundly impacts critical cellular functions, including proliferation, survival, and metastasis.

In recent decades, one of the active research areas has been to elucidate the mechanism of “Cell Competition”, a process where cells with varying fitness levels compete for resources and space within a tissue, resulting in the elimination of less fit cells. Studies have hypothesized that multiple communication channels, such as Ca2+ signaling imbalance, differences in the local electric field, mechanical stress due to the different growth rates, and activation of specific proteins and reactive oxygen species (ROS), can take place to eliminate the loser cells during cell competitions10,11,12,13,14,15. The metabolic state of a cell can also influence its ability to send and receive signals during cell competition or might produce molecules that disrupt the cell metabolism in loser cells or induce stress that triggers self-destruction16,17. Therefore, monitoring Vm, intracellular Ca2+ distribution, and intracellular environmental differences induced through metabolic changes between cancerous and normal cells can provide valuable insights into the cellular dynamics of these cells. Such knowledge is crucial for comprehending underlying communication mechanisms and developing innovative cancer therapies.

The triangular relationship among Ca2+, Vm, and NAD(P)H is fundamental to cellular energy regulation and signaling both in cancerous and normal cells. The Vm is a critical determinant of Ca2+ movement across membranes. Depolarization of the plasma membrane activates voltage-gated calcium channels, leading to an influx of extracellular Ca2+ into the cytosol, and this process can also be controlled by the release of Ca2+ from intracellular storage. Changes in cellular activity lead to an increase and a decrease in cytosolic Ca2+ level, which also influences the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and metabolism5,8,11,18. The increase of mitochondrial Ca2+ beyond the threshold levels can further activate the apoptotic mode of cell death by increasing the ROS level in mitochondria19. Controlling this triangular interplay is therefore of significant biomedical importance, particularly in cancer therapy. In this study, we introduced a nonthermal drug-free biophysical method of nanosecond pulsed electric fields (nsPEFs) to modulate cellular functions, including Vm, Ca2+ dynamics, and mitochondrial function. The electric field with a 50 ns ultrashort pulsewidth, which is much shorter than the membrane charging time, can directly interact with intracellular organelles, by passing the cellular membranes without affecting them20,21,22,23.

Multiple intensity-based methods have been employed to independently assess cellular Vm changes, Ca2+ distribution and mobilization, and mitochondrial function in various cancer cell lines24,25,26,27. In these studies, the changes in Vm and Ca2+ were identified by monitoring the relative changes in absorption and/or fluorescence intensities, as well as spectral shifts, of respective sensor probes following the Vm and Ca2+ changes. While these approaches have yielded valuable insights, a thorough understanding of the complex and heterogeneous nature of cancer necessitates a more integrated approach. In the present study, Vm and Ca2+ dynamics, and metabolic functions have been investigated by using a time-correlated single photon counting fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy in two genetically different breast cancerous MCF7 (ER+, PR+, and HER2−) and MDA-MB-231 (ER−, PR−, and HER2−) cells, and normal breast epithelial line MCF10A (ER−, PR−, and HER2 (low)), with special attention to identify the difference between normal and cancerous cells, as well as in subtypes of cancerous cells. We utilized exogenous fluorophores of Fluovolt and Oregon Green 488 BAPTA-1, AM (OGB), i.e., the membrane voltage-sensitive fluorophore and the intracellular Ca2+ sensor, respectively, to assess the difference in Vm and Ca2+ dynamics. To explore mitochondrial function, autofluorescence lifetime images and spectra of the endogenous fluorophores NAD(P)H and FAD, key metabolic coenzymes, were measured. To investigate the role of electric fields in intracellular organelle intercommunication and functional and dynamic changes induced by electric fields, we developed the 3D microelectrode devices and integrated them with a fluorescence lifetime imaging system. This device allows us to monitor the real-time effects of applied electric field on intracellular Ca2+ dynamics, Vm, and mitochondrial function in vitro without changing the adherent cell culture conditions. Mostly, the electric field effects on cellular systems were investigated in cancerous cells with electroporation cuvettes under non-adherent cell culture conditions. Accumulating research suggests that electric field effects on cancerous cells vary, depending on the culture conditions, and nonadherent cells are more vulnerable to nsPEF compared to adherent cells23. The present approach is to identify the effects of nsPEF on living cells without changing cell culture conditions. Furthermore, this strategy enables us to distinguish the difference between normal and cancerous breast cells, as well as among different breast cancer subtypes.

Results and discussion

Mapping of intracellular Ca 2+ ion concentration and distribution

Ca2+ ion dynamics was traditionally assessed by measuring the change in fluorescence intensity26,27. However, this method is limited by factors such as the spectral overlap of Ca2+ sensor probes with intracellular endogenous fluorophores, which exhibit emission in the same wavelength region, fluctuation of dye concentration, and excitation light power. Therefore, comparing the results in one biological system with others by using the fluorescence intensity measurements remained a challenge. Fluorescence lifetime image (FLIM) offers a more robust approach28,29,30,31,32. Unlike fluorescence intensity (FI), fluorescence lifetime (FL) is independent of the probe concentration, excitation light intensity, and photobleaching, enabling faithful detection of the difference in cellular function and dynamics, based on the altered fluorescence lifetime33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45. Moreover, FLIM overcomes challenges associated with spectral overlap in conventional multiplexing techniques.

In the present study, we employed the FI along with FLIM of exogenous fluorophore OGB to demonstrate the difference in cytosolic Ca2+ level and distribution in cancerous (MCF7 and MDA-MB-231) and normal MCF10A cells (Fig. 1). Besides, OGB exhibits distinct FL components corresponding to Ca2+-free and Ca2+-bound states41,42,43,44,46, which give shorter and longer FL of OGB, respectively. OGB FL calibration in a buffer solution, which demonstrates a dependence on increasing the free Ca2+ concentration (Fig. 1d)42,43,46, further validates the lengthening of the OGB lifetime upon Ca2+ ion binding. The change in Ca2+ concentration led to a variation in the relative contribution of the fast and slow decaying components with a biexponential decay analysis. Consequently, the OGB decay profiles observed via FLIM in the respective cells could be analyzed by assuming a biexponential decay model (Table S1). By quantifying the contribution of the longer lifetime component and its distribution, the intracellular Ca2+ concentration and distribution can be estimated precisely in the cells.

MCF7 cancerous cells exhibited widespread Ca2+ distribution, including the nucleus, and MDA-MB-231 cells primarily showed cytosolic localization of Ca2+ ions with a small presence in the nucleus. MCF10A normal cells also showed a localized Ca2+ distribution, which resembled MCF7 (Figs. 1a–c). The intracellular Ca2+ distribution, particularly within the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and nucleus, was further examined using high-contrast black-and-white images (Fig. S1). While it was difficult to directly distinguish the different Ca2+ distribution in cancerous cells from normal cells simply based on the OGB fluorescence intensity, the amplitude weighted average lifetime (AWAL) of OGB revealed distinct profiles in MCF10A cells, with longer lifetime on the plasma membrane compared to other intracellular space, which is very different from the cancerous cells (Figs. 1a’–c’, e, f, and S2). Moreover, the large ratio of the preexponential factor of the long lifetime component (i.e., Ca2+-bound component), relative to the short lifetime component (i.e., free OGB component), which leads to a long average lifetime, implied substantially high intracellular Ca2+ levels in cancerous cells, compared to their normal counterparts. A similar difference in Ca2+ concentration between cancerous and normal cells was also observed in lung cells (i.e., H661 carcinoma vs. MRC-5 normal cells), as shown in Supporting Information (Fig. S3). The longer OGB fluorescence lifetime was found in H661, referring to the higher intracellular Ca2+ levels in cancerous cells compared to their normal counterparts, irrespective of the cell’s origin.

Color-coded FI images (a–c) and AWAL FLIMs (a’–c’) of OGB in MCF7 (a, a’), MDA-MB-231 (b, b’), and MCF10A (c, c’) cells (scale bar = 20 μm). Panel (d) shows the fluorescence decay profiles of OGB in buffer at the indicated [Ca2+] concentration; (e) histogram of the OGB AWAL distribution in the respective images (a’–c’), and (f) statistically analyzed differences in OGB AWAL among cells with the significance ***p < 0.001. Each dot presented in (f) represents one experiment.

Autofluorescence lifetime images (AFLIMs) of NAD(P)H and FAD

It has been recognized that tuning mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis is important to control cell viability. There is also a possibility that Ca2+-dependent metabolic reprogramming alters the autofluorescence AWAL and distribution of NAD(P)H and FAD in the intracellular space of living cells and their interactions with the surroundings, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) and proteins. Autofluorescence of NAD(P)H is emitted not only from mitochondria, but also from other intracellular compartments, while FAD autofluorescence is primarily produced by mitochondrial flavins47. NAD(P)H and FAD play essential roles as electron donors and acceptors, respectively, during ATP generation. AFLIMs and autofluorescence spectra of NAD(P)H and FAD have been employed not only to identify the differences between normal and cancerous cells but also to distinguish oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis, as well as to detect cell death15,36,37,38,39,40.

Color-coded intensity (a–c) and AWAL (a’–c’) images of autofluorescence of NAD(P)H (left) and FAD (right) in MCF7 (a, a’), MDA-MB-231 (b, b’) and MCF10A (c, c’) cells (scale bar = 20 μm). (d) Fluorescence spectra of NAD(P)H (left) and FAD (right), (e) histograms of the distribution of autofluorescence AWAL of NAD(P)H (left) and FAD (right), and (f) statistically analyzed data of AFL of NAD(P)H (left) and FAD (right) for different cells with significance ***p < 0.001. Each dot presented in (f) represents one experiment.

Autofluorescence decay profiles, color-coded AFLIMs and photon intensity images of NAD(P)H and FAD obtained with excitation at 370 nm and 450 nm, respectively, by monitoring the emission in the 400–480 nm and 500–580 nm wavelength region show remarkable differences in the average value of AWAL (τav) and in intensity distribution among MCF7, MDA-MB-231, and MCF10A cells, as shown in Figs. 2a–c, a’–c’, e, f. The histograms of the AFLIMs clearly show that τav is longer in normal cells MCF10A than in cancerous cells MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 (Fig. 2e). The autofluorescence shows a nonexponential decay (Fig. S4). The profiles were analyzed by assuming a biexponential decay with fast and slow decaying components (Tables S2 and S3). Compared to MCF10A cells, MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cells exhibited shorter average lifetime of NAD(P)H and FAD by ~ 30 and 40% (Fig. 2f (left) and Table S2 and S3). This is caused by the longer lifetime of both fast and slow components, as well as the large preexponential factor of the slow component in MCF10A, compared with cancerous cells MCF7 and MDA-MB-231. These differences between normal and cancerous cells may come from the reliance on oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis35,36,37,38, which may also change their binding nature to respective proteins. The obtained difference in NAD(P)H lifetime between normal and cancerous cells follows a similar trend to that reported in other normal and cancerous cells35,38,39,40. Nevertheless, the FAD lifetime shows complex behavior depending on experiments and time-detection limits38,39. Because the FAD itself exists in multiple forms, such as closed, semistacked, and open, with different electron transfer properties48. These different species of FAD may also have different interactions with surrounding proteins and exhibit different lifetimes in the range of ps – ns time scale.

It is also noted that not only the AWAL but also the fluorescence spectra of FAD are significantly different between normal and cancerous cells; fluorescence spectra of FAD in normal cells show a blue shift, compared with the spectra in cancerous cells (Fig. 2d (right)). The oxidized form of flavin mononucleotide (FMN) exhibited a blue shift in emission spectra compared to the pure FAD49. The blue shift of the FAD spectra in MCF10A cells, in comparison with the cancerous counter parts, may come from a large spectral spectra of FMN and FAD emissions in MCF10A cells. This emission overlap in normal cells might result in the lengthening of FAD lifetime in normal breast cells, compared to cancerous counterparts. The differences in FMN and FAD emission overlap in cancerous and normal cells may be limited to breast cells, since FAD fluorescence spectra remained the same in both normal and cancerous lung cells46. This is different from NAD(P)H; the fluorescence lifetimes of NAD(P)H are different between normal and cancerous cells, but fluorescence spectra are very similar to each other (Fig. 2d (left)).

It is found that the AWAL of NAD(P)H and FAD depend on cellular conditions. In contrast with the adherent state, autofluorescence of both NAD(P)H and FAD was significantly quenched in suspensions, regardless of cell types (Fig. S5). The decay profiles of NAD(P)H and FAD observed for suspension cells were analyzed by assuming a triexponential decay; an example of triexponential decay analysis in NAD(P)H is shown in Fig. S6. The lifetime and preexponential factor of each decaying component, as well as the average lifetime, are shown in Tables S4 and S5. Usually, autofluorescence decays of NAD(P)H and FAD are considered to consist of two components, i.e., fast and slow components, which are assigned to the free and protein-bound NAD(P)H, vice versa in FAD38,39. However, it should be stressed that a three or four-component model was necessary in some cases to analyze the fluorescence decay of NAD(P)H and FAD35,40,50,51, indicating that the two-component model is too simplistic. This complexity is likely due to the presence of different molecular forms of fluorophore and the presence of different kinds of protein-bound species.

The contribution of the very slow component identified in the decay in suspension, whose lifetime is given as τ3, is very small, as known from the small preexponential factor of this component (see Tables S4 and S5). Fluorescence decay profiles in adherent cells were analyzed by assuming a biexponential decay, but the slow component whose lifetime corresponds to τ3 in suspension may also exist in adherent cells, though this component was not identified in the observed decay profiles, because of the experimental limitation of the time scale of the decay measurements in adherent cells.

The AWAL of NAD(P)H in suspension cells was shorter in normal cells than in cancer cells, which was opposite to that in adherent cells. In contrast with NAD(P)H, the AWAL of FAD is longer in normal cells than in cancerous cells both in suspension and in adherent cells. These cellular and environment-dependent AWAL of NAD(P)H and FAD may be related to the difference in ROS generation and the difference in the local electric field among the cells52,53,54,55. The local electric fields may have significantly contributed to regulate the interplay between cell metabolism and Ca2+ homeostasis in both cancerous and normal cells. One example of the different local fields among the cells may be the existence of different Vm.

Mapping of Vm through the FLIMs of Fluovolt

Membrane potential Vm maintained by ionic gradients across the plasma membrane reflects the electrical property of cells. The presence of positive and negative charges in intracellular and extracellular space may affect Vm. To estimate the Vm of the cells, the patch clamp technique is generally used, but it is invasive and cannot be implemented for longer periods. Then, we employed Fluovolt, which is a membrane voltage-sensitive dye56, to enable noninvasive monitoring of Vm under different physiological changes not only in an individual cell but also in a group of cells.

FL of Fluovolt depends on positive and negative charges located between the cytoplasm and extracellular space57. In the depolarized state of cells, where more positive charges are located in the cytoplasm, the FL of Fluovolt becomes longer, and vice versa in the hyperpolarized state of cells56. The color-coded photon distributions and FLIMs, fluorescence decay profiles, and the histograms of the distribution of FL of Fluovolt in respective cells revealed that the FL of Fluovolt is longer in MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 than in their counterpart normal MCF10A cells (Figs. 3a–c, a’–c’, d, e, f, and S7), irrespective of the experimental conditions, suggesting the presence of a depolarized state in cancerous cells56,57. This finding is well correlated with higher intracellular Ca2+ levels in breast cancerous cells. The degree of depolarization is also different among subtypes of breast cancerous cells. The MDA-MB-231 cells exhibited a more depolarized state than MCF7 cells. This observation is consistent with the higher intracellular Ca2+ concentration in MDA-MB-231 cells, compared to MCF7 cells.

Color-coded fluorescence intensity distributions (a–c) and FLIMs (a'-c') of Fluovolt in MCF7 (a, a’), MDA-MB-231 (b, b’), and MCF10A (c, c’) cells (scale bar = 20 μm). (d) Fluorescence decay profiles of Fluovolt collected at multiple positions at the cell membrane, (e) the histogram of the distribution of Fluovolt FL, and (f) statistically analyzed data of Fluovolt FL for each of the different cell lines with significance ***p < 0.001. Each dot presented in (f) represents one experiment.

Modulation of the intracellular Ca 2+, NAD(P)H, and Vm by applied electric field

Along with identifying the functional differences among breast cancerous and normal cells through the FLIM and AFLIM measurements of OGB, NAD(P)H, FAD, and Fluovolt, we also sought a physical method to identify the role of the local electric field in intercommunications among organelles and modulating cellular functions in cancerous cells for improved treatment. It has been identified that the rectangular pulses shorter than the membrane charging time (~ 150 ns) can pass through the plasma membrane and induce multiple functional and dynamical changes both in space and time15,20,21,22,23. To investigate the electric field effects on intracellular environments, herein, we applied the 50 nanoseconds rectangular-shaped electric pulses with a strength of 20 kVcm− 1 (nsPEF) in all of the cells through 3D microelectrode device, whose structure has shown elsewhere15,58, under two different conditions: (1) application of 120 pulses with a frequency of 1 Hz (2-min application), and (2) application of 2 × 104 pulses with a frequency of 2 kHz (10-sec application) (Fig. S8). The field-induced changes were found to be essentially the same in both applied field configurations, as confirmed through the FLIM (AFLIM) measurements of OGB, NAD(P)H, and Fluovolt, and the FI imaging of OGB and MitoSox™ before, during, and after nsPEF application.

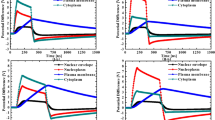

As mentioned above, the AWAL of OGB increased with increasing Ca2+ ion concentration. The application of nsPEFs on MCF7 cells revealed the initial increase of cytosolic [Ca2+], followed by a decrease, regardless of pulse number or application mode (Figs. 4a, b and S9 and S10). Since the pulse width of nsPEF (50 ns) is considered to be shorter than the plasma membrane charging time22,23, it is unlikely that Ca2+ influx from the outside of cells was caused by electroporation. The initial increase in cytosolic Ca2+ level upon nsPEF application probably owing to the Ca2+ efflux from the ER as a result of the direct interaction of nsPEF with ER. The Ca2+ release from ER may have subsequently activated calcium release-activated channels, located on the plasma membrane, leading to a gradual decrease in the Ca2+ level59. The real-time intensity measurements of OGB also confirmed these observations (Fig. S11). The field-induced change in cytosolic Ca2+ level was not significant in MDA-MB-231 and MCF10A cells, in contrast to MCF7 cells.

The application of nsPEF also induced an increase of AWAL of NAD(P)H by about 30 % in MCF7 cells, regardless of the applied electric field conditions, while AWAL of NAD(P)H was not significantly influenced by nsPEF in MDA-MB-231 and MCF10A cells, as shown in Figs. 4c, d, and Figs. S12 and S13. The field-induced increase in AWAL of NAD(P)H, along with the initial increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration, is a characteristic feature of the mitochondrial-mediated apoptotic cell death19,58,60 with a significant elevation of superoxide anion (O2−) in mitochondria at later stages. As can be seen in Fig. S14, the fluorescence intensity of MitoSoxTM was significantly increased in MCF7 cells under both the electric field configurations. On the other hand, in MCF10A and MDA-MB-231 cells, the field-induced changes in fluorescence intensity of MitoSoxTM were not significant. No change in AWAL of NAD(P)H by nsPEF in MDA-MB-231 and MCF10A cells may be attributed to either mitochondrial nonactivation or the initiation of necrotic cell death60. With nsPEF having a strength of 20 kVcm−1, frequency of 2 kHz, and application time of 2 min, it was reported that the modes of cell death induced by application of nsPEF differed among different cell types: MCF7 cells underwent caspase-dependent cell death, whereas MDA-MB-231 showed caspase-independent cell death60. MCF10A cells exhibited significantly higher survivability than the cancerous cell types upon nsPEF application, and MCF10A cells that did not survive under the nsPEF treatment experienced a caspase-independent death process58. Mitochondria may remain unaffected by the application of nsPEF in MCF10A and MDA-MB-231 cells, in contrast with MCF7. The ER/PR/HER2 statuses may play an important role in controlling cell death when exposed to nsPEF. Earlier studies reported that MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cells, which differ in their ER/PR/HER2 statuses, undergo different modes of cell death: apoptosis in MCF7 and necroapoptosis in MDA-MB-231. At the same time, MCF10A cells showed higher survivability under electric field applications, though the field configuration in those studies differed from the current one. In addition to the ER/PR/HER2 statuses, MCF7 cells may also have a lower dielectric constant compared to MCF10A and MDA-MB-231 cells61,62. This could mean that, even though the external electric field strength is the same for all cell lines, the actual electric field strength reaching targeted intracellular organelles in MCF7 cells is higher than that in MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 cells. Another possibility is a difference in the local electric field, whose strength can reach up to MVcm−163,64, in the intracellular space, which might have also impacted the properties of the externally applied electric field in the respective cells. The field-induced changes both in Ca2+ distribution and in AWAL of NAD(P)H in MCF7 indicate an intercommunication between the ER and mitochondria in MCF7 with a flow of Ca2+ ions19. Such an intercommunication was not observed in MDA-MB-231 and MCF10A cells, potentially due to the inability of nsPEF to effectively release Ca2+ from ER or engage with other intracellular organelles. The effects of nsPEF on Vm differed among MCF7, MDA-MB-231, and MCF10A cells. As shown previously, nsPEF application severely influenced MCF7 cells on intracellular Ca2+ level and AWAL of NAD(P)H, and exhibited a more depolarized state, i.e., longer lifetime of Fluovolt upon nsPEF application in MCF7 cells (Figs. 4e–f, and S15 and S16). The depolarization, i.e., an increase of Vm, may serve as one of the signatures of early events of apoptotic cell death, leading to the loss of cell volume and membrane integrity65. The cell viability data presented in Fig. S17, which were obtained before and after application of 120 pulses of nsPEF having a strength of 20 kVcm−1 and frequency 1 Hz in respective cells, further confirm that cell death occurred significantly in MCF7 cells, and MDA-MB-231 and MCF10A cells remained viable. It is noted that MDA-MB-231 also showed a cell death with application of nsPEF with a frequency of 2 kHz, field strength of 20 kVcm−1 and 2 min application time, though MCF10A didn’t show a cell death under the same condition58,60.

The observed depolarization by nsPEF in MCF7 cells (i.e., the field-induced increase of Vm) seems to be strongly linked to the increase of intracellular Ca2+ ion concentration, though the movement of Na+ and K+ ions may also have to be considered65. Alternatively, the results that the FL of Fluovolt, i.e., Vm, did not show a significant change in MDA-MB-231 and MCF10A cells upon nsPEF application somehow implied that these cells are not susceptible toward nsPEF. The intracellular Ca2+ level, AWAL of NAD(P)H, and O2− generation thus remained relatively unaltered. These findings clearly indicate that the effects of nsPEF on intracellular function depend on the cell types, and such an electric field effect is more effective in cancerous cells than in normal cells15,57,66,67.

The statistically analyzed differences in field-induced changes in AWAL of OGB, i.e., intracellular Ca2+ level, (a, b), AWAL of NAD(P)H (c, d), and FL of Fluorovolt, i.e., Vm, (e, f) in MCF7, MDA-MB-231, and MCF10A cells with significance ***p < 0.001. Upper figures (a, c, e), represent the effects of the application of 120 pulses of nsPEF with a frequency of 1 Hz, and lower figures (b, d, f), represent the effects of 10 s application of nsPEF with a frequency of 2 kHz (application of 2 × 104 pulses). Note, each dot shown in the figures represents one experiment. The image acquisition time for OGB and Fluovolt in all the conditions was 120 s. The image acquisition time for NADH was 300 s.

Conclusion

The present results of FLIMs (AFLIMs) of OGB, NAD(P)H and FAD, and Fluovolt, which reflected the Ca2+ ion concentration, mitochondrial functionality, and membrane electric potential, show distinctive profiles among cancerous (MCF7, MDA-MB-231) and normal (MCF10A) cell types and the different susceptibility toward the electric field treatment. These differences, based on ER/PR/HER2 statuses and cellular responses to the electric field, indicate that the electric properties of cells depend on their genetic status. This reinforces the role of the local electric field, whose strength may reach MVcm− 1 in the cellular space and time, varying with biophysical and biochemical changes. Such a strong local field may also influence the structure and dynamics of neighboring or associated molecules. The present findings could open new avenues for harnessing the bioelectric field for drug-free, electric field-based therapies.

Methods

Cell line and culture

The breast cancerous MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cells were obtained from the Bioresource Collection Research Center (BCRC), Taiwan, and grown in Minimum Essential Medium Eagle (MEMα, 1256-056; Gibco Thermo Fisher) and Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F12, 11320-033; Gibco Thermo Fisher), respectively. Both media were supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Pen Strep, 15140-122; Gibco Thermo Fisher) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, 26140-079; Gibco Thermo Fisher). The breast normal cells MCF10A were obtained from Blossom Biotechnologies Inc., Taiwan, and grown in MCF10A cells culture medium (NM3326645090; Elabscience). All cell lines were maintained in an incubator with a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C.

Intracellular Ca2+ imaging

The intracellular Ca2+ concentration and distribution were evaluated by using OGB (2518921, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a concentration of 3 µM in cell imaging media. The OGB-stained cells were incubated in the dark for 20 min in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37 °C. After incubation, the cells were washed twice with PBS, and fresh cell imaging media were added before the optical experiments. To calibrate the OGB fluorescence lifetime change following the increase in free Ca2+ concentration (0 to 39 µM), a Ca2+ calibration buffer kit (C3008MP, Thermo Fisher Scientific), which is a combination of zero free Ca2+ buffer and 10 mM CaEGTA, was used. The free Ca2+ concentrations were increased by increasing the relative molar concentration of CaEGTA in the buffer. A high-definition color camera (DS-Ri2, Nikon) was used to detect the field-induced change in OGB fluorescence intensity.

Membrane potential imaging

The Vm was measured using Fluovolt (F10388, ThermoFisher Scientific) at 1X concentration in cell imaging media. The Fluovolt-stained cells were incubated in the dark for 15 min in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37 °C and then washed twice with PBS, followed by the replacement of cell imaging media before the optical experiments.

FLIM, AFLIM, and decay measurements

FLIMs and AFLIMs were measured by using an inverted microscope (TE2000E, Nikon) through a 60X water immersion objective lens (NA 1.2, Nikon) coupled with a Becker & Hickel TCSPC system (GmbH, SPC-830) and a Ti: sapphire laser (Tsunami, Spectra-Physics, 80 fs pulse width and a repetition rate of 81 MHz) as an excitation light source. In the FLIM measurements of OGB and Fluovolt, a Ti: sapphire laser was tuned to 920 nm and frequency doubled to 460 nm through an ultrafast harmonic system (Model 5–050, Inrad). Similarly, to excite NAD(P)H and FAD, the second harmonic generation light at 370 and 450 nm, respectively, was obtained by tuning a Ti: sapphire laser light to 740 and 900 nm, respectively. The excitation laser power was controlled to be ~ 1 mW at the fiber tip with a neutral density filter. The fluorescence from OGB, Fluovolt, and FAD in the region of 500–580 nm, and the NAD(P)H fluorescence in the 400–480 nm region was detected by a photomultiplier tube (R3809U, Hamamatsu). The TCSPC image collection time was 120 s, with a pixel dwell time of 10 µs/pixel. Fluorescence decay profiles of OGB in a buffer solution containing various concentrations (0 to 39 µM) of free Ca2+ were measured by a homemade TCSPC system with a photomultiplier tube (R3809U-52, Hamamatsu) with a laser repetition rate of 5.7 MHz, the detailed development processor has been reported elsewhere68, with which autofluorescence spectra of NAD(P)H and FAD in bulk suspension were also measured by accumulating the ~ 106 cells in a 2 mm quartz cuvette with excitation at 370 and 450 nm, respectively, with a 2 nm step through a monochromator (G-250, Nikon).

Mitochondrial O2 − detection

The mitochondrial O2− was examined through MitoSOX™ (M36008, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a 2 µM concentration in cell imaging media. The MitoSOXTM-stained cells were incubated in the dark for 10 min in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37 °C and then washed twice with PBS, followed by replacing the cell imaging media before the optical measurements. Fluorescence intensity images shown in Fig. S14 were measured systematically by monitoring the emission at ≥ 590 nm with a 15 s time interval for 300 s through a high-definition color camera (DS-Ri2, Nikon) with excitation at 525/25 nm by a xenon lamp.

Cell viability detection

Cell viability was detected with a LIVE/DEAD Viability/Cytotoxicity assay (L3224, Thermo Fisher Scientific), a molecular probe containing a green fluorescent calcein AM and a red fluorescent ethidium homodimer (EthD-1). All cells were loaded with 0.1 µM calcein AM and incubated in the dark for 10 min in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37 °C and then washed twice with PBS. After that, 10 µM EthD-1 was added. The fluorescence from calcein AM was detected with a combination of excitation and emission filters, 475/35 and 540/40 nm, respectively, and fluorescence from EthD-1was detected with a combination of excitation and emission filters, 525/35 and 590 nm, respectively, before and after applying the nsPEF. The decrease and increase of green and red fluorescence in the intracellular space, respectively, indicates the cell death.

Microchamber electrode fabrication and pulse application

A UV photolithography technique was employed to fabricate 3D microelectrode chips on a microscopic quartz substrate. Microchamber arrays, measuring 10 mm in length, 200 μm in width, and 20 μm in depth, were created by spin coating of SU-8 2015 negative photoresist (Micro Chem) following the UV light exposure through a specially designed mask. A positive photoresist, ZEP520 (ZEONREX Electronic Chemical), was then spin-coated over the developed microchamber arrays and exposed to UV light again using the same mask to cover the areas outside the microchamber arrays. Subsequently, titanium (Ti, 10 nm) and gold (Au, 30 nm) layers were deposited twice at angles of + 45° and − 45°. The excess Ti and Au films were removed by baking the ZEP520 at 120 °C, followed by a 10–15 min ultrasonic treatment in acetone. This non-invasive movable device enables the measurements of the electric field effects while preserving the cellular conditions. The cells were cultured on the microchamber electrodes for 24 h before conducting electric field optical experiments. The pulsed voltage (50 ns, 400 V) was applied through a 50 Ω load using a pulse generator (AVL-5-B-TR, AVTECH) with a repetition rate of 1 Hz or 2 kHz.

Software and statistics

The FLIM analysis was performed using SPCImage 8.6 software (Becker & Hickl), and the data figures were plotted using IgorPro 6.2 software. Intensity analysis was conducted using NIS-Elements D (Nikon) software. The results are presented as mean ± SD. For statistical analysis, one-way ANOVA was performed using GraphPad Prism 10, with p-values stated in the figure captions.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request to Nobuhiro Ohta at nohta@nycu.edu.tw.

References

Buddingh, B. C., Elzinga, J. & van Hest, J. C. M. Intercellular communication between artificial cells by allosteric amplification of a molecular signal. Nat. Commun. 11, 1652 (2020).

Kholodenko, B. N. Cell-signalling dynamics in time and space. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Boil. 7, 165–176 (2006).

Carafoli, E. & Krebs, J. Why calcium? How calcium became the best communicator. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 20849–20857 (2016).

Clapham, D. E. Calcium signaling. Cell 14, 1047–1058 (2007).

Zheng, S., Wang, X., Zhao, D., Liu, H. & Hu, Y. Calcium homeostasis and cancer: insights from endoplasmic reticulum-centered organelles communications. Trend Cell. Biol. 33, 312–323 (2023).

Monteith, G. R., Prevarskaya, N. & Roberts-Thomson, S. J. The calcium-cancer signalling nexus. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 17, 373–380 (2017).

Rizzuto, R., Stefani, D. D., Raffaello, A. & Mammucari, C. Mitochondria as sensors and regulators of calcium signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13, 566–578 (2012).

Dejos, C., Gkika, D. & Cantelmo, A. R. The two-way relationship between calcium and metabolism in cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8, 573747 (2020).

Contreras, L., Drago, I., Zampese, E., & Pozzan, T. Mitochnodria: The calcium connection. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 1797, 607–618 (2010).

Baker, N. E. Emerging mechanisms of cell competition. Nat. Rev. Gen. 21, 683–697 (2020).

Piddini, E. & Vishwakarma, M. Outcompeting cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 20, 187–198 (2020).

Norman, M. et al. Loss of scribble causes cell competition in mammalian cells. J. Cell. Sci. 125, 59–66 (2012).

Clavería, C. & Torres, M. Cell competition: Mechanisms and physiological roles. Ann. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 32, 411–439 (2016).

Kuromiya, K. et al. Calcium sparks enhance the tissue fluidity within epithelial layers and promote apical extrusion of transformed cells. Cell Rep. 40, 111078 (2022).

Awasthi, K., Chang, F. L., Hsu, H. Y. & Ohta, N. Cancer specific apoptosis induced by electric field: A possible key mechanism in cell-competition and photodynamic action. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 347, 130635 (2021).

Esteban-Martinez, L. & Torres, M. Metabolic regulation of cell competition. Develop. Biol. 475, 30–36 (2021).

Coloff, J. & Brugge, J. Metabolic changes promote rejection of oncogenic cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 19, 414–415 (2017).

Huang, D. X. et al. Calcium signaling regulated by cellular membrane systems and calcium homeostasis perturbed in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 19, 834962 (2022).

Awasthi, K., Chang, F. L., Wu, T. E., Hsu, H. Y. & Ohta, N. Modulation of calcium signaling by nanosecond electric pulses and cell death through apoptosis in A549 lung cancerous cells. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 369, 132348 (2022).

Beebe, S. J., Sain, N. M. & Ren, W. Induction of cell death mechanisms and apoptosis by nanosecond pulsed electric fields (nsPEFs). Cells 2, 136–162 (2013).

Nuccitelli, R. et al. Nanosecond pulsed electric fields cause melanomas to self destruct. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 343, 351–360 (2006).

Awasthi, K., Nakabayashi, T. & Ohta, N. Effects of nanosecond pulsed electric fields on the intracellular function of HeLa cells as revealed by NADH autofluorescence microscopy. ACS Omega 1, 396–406 (2016).

Beebe, S. J., Joshi, R., Schoenbach, K. H. & Xiao, S. Ultrafast Electric Pulse Effects in Biology and Medicine (Springer, 2021).

Peterka, D. S., Takahashi, H. & Yuste, R. Imaging voltage in neurons. Neuron 69, 9–20 (2011).

Ross, W. N. & Reichardt, L. F. Species-specific effects on the optical signals of voltage-sensitive dyes. J. Membrane Biol. 48, 343–356 (1979).

Wendt, E. R., Ferry, H., Greaves, D. R. & Keshav, S. Ratiometric analysis of Fura red by flow cytometry: A technique for monitoring intracellular calcium flux in primary cell subsets. PLoS ONE 10, e0119532 (2015).

Raffaello, A. & Reane, D. V. Calcium Signalling: Methods and Protocols (Springer, 2019).

Ohta, N. et al. Fluorescence lifetime imaging study of a single cell: Stress-induced environmental change and electric field effects on fluorescence. SPIE 7190, 71900R (2009).

Williams, G. O. S. et al. Full spectrum fluorescence lifetime imaging with 0.5 nm spectral and 50 ps temporal resolution. Nat. Commun. 12, 6616 (2021).

Shcheslavskiy, V. I. et al. Fluorescence lifetime imaging techniques-a review on principles, applications and clinical relevance. J. Biophotonics. 0, e202400450 (2025).

Becker, W., Su, B. & Bergmann, A. Spatially resolved recording of transient fluorescence-lifetime effects by line-scanning TCSPC. SPIE 8226, 82260C (2012).

Becker, W., Shcheslavkiy, V., Frere, S. & Slutsky, I. Spatially resolved recording of transient fluorescence-lifetime effects by line-scanning TCSPC. Microsc. Res. Techne. 77, 216–224 (2014).

Blacker, T. et al. Separating NADH and NADPH fluorescence in live cells and tissues using FLIM. Nat. Commun. 5, 3936 (2014).

Bowman, A. J., Huang, C., Schnitzer, M. J. & Kasevich, M. A. Wide-field fluorescence lifetime imaging of neuron spiking and subthreshold activity in vivo. Science 380, 1270–1275 (2023).

Awasthi, K., Moriya, D., Nakabayashi, T., Li, L. & Ohta, N. Sensitive detection of the intracellular environment of normal and cancer cells by autofluorescence lifetime imaging. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 165, 256–265 (2016).

Mah, E. J., Lefebvre, A. E. Y. T., McGahey, G. E., Yee, A. F. & Digman, M. A. Collagen density modulates triple-negative breast cancer cell metabolism through adhesion-mediated contractility. Sci. Rep. 8, 17094 (2018).

Karrobi, K. et al. Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) reveals spatial-metabolic changes in 3D breast cancer spheroids. Sci. Rep. 13, 3624 (2023).

Skala, M. C. et al. In vivo multiphoton microscopy of NADH and FAD redox states, fluorescence lifetimes, and cellular morphology in precancerous epithelia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 19494–19499 (2007).

Yakimov, B. et al. Simultaneous assessment of NAD(P)H and flavins with multispectral fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy at a single excitation wavelength of 750 nm. J. Biomed. Opt. 29, 106501 (2024).

Awasthi, K., Chang, F. L., Hsieh, P. Y., Hsu, H. Y. & Ohta, N. Characterization of endogenous fluorescence in nonsmall lung cancerous cells: A comparison with nonmalignant lung normal cells. J. Biophotonics 13, e201960210 (2020).

Zheng, K. et al. Time-resolved imaging reveals heterogeneous landscapes of nanomolar Ca2+ in neurons and astroglia. Neuron 88, 277–288 (2015).

Sagolla, K., Löhmannsröben, H. G. & Hille, C. Time-resolved fluorescence microscopy for quantitative Ca2+ imaging in living cells. Anal. Bioanal Chem. 405, 8525–8537 (2013).

Zheng, K., Jensen, T. & Rusakov, D. Monitoring intracellular nanomolar calcium using fluorescence lifetime imaging. Nat. Protoc. 13, 581–597 (2018).

Gest, A. M. M. et al. A red-emitting carborhodamine for monitoring and measuring membrane potential. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 121, e2315264121 (2024).

Boggess, S. C. et al. Fluorescence lifetime predicts performance of voltage-sensitive fluorophores in cardiomyocytes and neurons. RSC Chem. Biol. 2, 248–258 (2021).

Lattarulo, C., Thyssen, D., Kuchibholta, K. V., Hyman, B. T. & Bacskaiq, B. J. Microscopic imaging of intracellular calcium in live cells using lifetime-based ratiometric measurements of oregon green BAPTA-1, In Neurodegeneration: Methods and Protocols, Methods in Molecular Biology (eds Manfredi G., Kawamata H.) 377–389 Vol. 793 (Springer, 2011).

Kunz, W. S. & Kunz, W. Contribution of different enzymes to flavoprotein fluorescence of isolated rat liver mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 841, 237–246 (1985).

Awasthi, K., Wu, T. E., Hsu, H. Y. & Ohta, N. Application of nanosecond pulsed electric field and autofluorescence lifetime microscopy of FAD in lung cells. J. Phys. Chem. B 127, 5566–5575 (2023).

Kao, Y. T. et al. Untrafast dynamics of flavins in five redox states. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 13132–13139 (2008).

Ogikubo, S. et al. Intracellular pH sensing using autofluorescence lifetime microscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 115, 10385–10390 (2011).

Islam, M. S., Honma, M., Nakabayashi, T., Kinjo, M. & Ohta, N. pH dependence of the fluorescence lifetime of FAD in solution and in cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 1952–1963 (2013).

Schafer, Z. et al. Antioxidant and oncogene rescue of metabolic defects caused by loss of matrix attachment. Nature 461, 109–113 (2009).

Gorrini, C., Harris, I. & Mak, T. Modulation of oxidative stress as an anticancer strategy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 12, 931–947 (2013).

Callis, P. R. & Burgess, B. K. Tryptophan fluorescence shifts in proteins from hybrid simulations: an electrostatic approach. J. Phys. Chem. B. 101, 9429–9432 (1997).

Pokorny, J., Pokorny, J. & Kobilkova, J. Postulates on electromagnetic activity in biological systems and cancer. Integr. Biol. 5, 1439–1446 (2013).

Lazzari-Dean, J. R., Gest, A. M. M. & Miller, E. W. Optical estimation of absolute membrane potential using fluorescence lifetime imaging. eLife 8, e44522 (2019).

Berzingi, S., Newman, W. & Yu, H. G. Altering bioelectricity on inhibition of human breast cancer cells. Cancer Cell Int. 16, 72 (2016).

Awasthi, K., Huang, W. C., Wei, C. Y., Hsu, H. Y. & Ohta, N. Unveiling the susceptibility of nanosecond pulsed electric field on intracellular function in breast cancerous and normal cells using fluorescence imaging. Biosens. Bioelectron. 272, 117129 (2025).

White, J. A., Blackmore, P. F., Schoenbach, K. H. & Beebe, S. J. Stimulation of capacitive calcium entry in HL-60 cells by nanosecond pulsed electric fields. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 22964–22972 (2004).

Awasthi, K., Li, S. P., Zhu, C. Y., Hsu, H. Y. & Ohta, N. Fluorescence microscopic approach for detection of two different modes of breast cancer cell death induced by nanosecond pulsed electric field. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 378, 133199 (2023).

Ermolina, I., Polevaya, Y., Feldman, Y., Ginzburg, B. Z. & Schlesinger, M. Study of normal and malignant white blood cells by time domain dielectric spectroscopy. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 8, 253–261 (2001).

Ahmad, M. A., Natour, Z. A., Mustafa, F. & Rizvi, T. A. Electrical characterization of normal and cancer cells. IEEE Access 6, 25979–25986 (2018).

Lockhart, D. J. & Kim, P. S. Internal Stark effect measurement of the electric field at the amino terminus of an α-helix. Science 257, 947–951 (1992).

Kriegl, J. M., Nienhaus, K., Deng, P., Fuchs, J. & Nienhaus, G. U. Ligand dynamics in a protein internal cavity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 100, 7069–7074 (2003).

Bortner, C. D., Gomez-Angekats, M. & Cidlowski, J. A. Plasma membrane depolarization without repolarization is an early molecular event in anti-fas-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 4304–4314 (2001).

Awasthi, K., Nakabayashi, T., Li, L. & Ohta, N. Effects of nanosecond pulsed electric field on intracellular NADH autofluorescence: A comparison between normal and cancer cells. ACS Omega 2, 2916–2924 (2017).

Yang, W. et al. Differential sensitivities of malignant and normal skin cells to nanosecond pulsed electric fields. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 10, 281–286 (2011).

Tsushima, M., Ushizaka, T. & Ohta, N. Time-resolved measurement system of electrofluorescence spectra. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 75, 479–485 (2004).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan (NSTC 113-2113-M-A49-021, NSTC 114-2113-M-A49-013). This work was also supported financially by The Center for Emergent Functional Matter Science of National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University from The Featured Areas Research Center Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kamlesh Awasthi: Writing-original draft, Optical Measurements, Data analysis, Methodology. Wei-Chen Huang: Live cell experiments, Optical measurements, Data analysis. Hsin-Yun Hsu: Writing-review editing. Nobuhiro Ohta: Writing-review editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Awasthi, K., Huang, WC., Hsu, HY. et al. Visualizing intracellular milieu and electric field-induced cell responses by fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy. Sci Rep 16, 2268 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32020-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32020-y