Abstract

Waste dumps generated during open-pit mining directly affect operational safety, and their hazards increase with dump height. During the stacking of high-bench dumps composed of soil-rock mixtures, particle rolling along the slope commonly produces particle-size grading, yielding gradation patterns that differ markedly from those of conventional dumps. Based on a field case, an improved cellular automaton (CA) was coupled with the finite difference method (FDM) to clarify how spatially disordered particle arrangements influence the distribution of shear-strength parameters in soil-rock mixtures. A slope-stability analysis framework tailored to high-bench dumps was developed, and the effect of particle grading on stability was assessed. Owing to spatial variability in particle distribution, strength parameters exhibited significant scatter even for identical overall gradation; both cohesion and internal friction angle were found to follow normal distributions. Particle grading along the slope was shown to reduce the deformation and volume of the tensile plastic zone, raise the slip-surface position, and increase the factor of safety. These findings advance the understanding of soil-rock mixture mechanics and provide a practical reference for slope stability analysis of complex particulate materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Open-pit mining inevitably generates waste materials, primarily soil and crushed rock. The collective deposition of these materials forms large accumulations of loose sediment known as waste dumps1. To optimize management and minimize the required footprint, mining operations increasingly utilize high-bench dumps, which feature progressively greater heights. For instance, the Jiangshan dump at the Zijinshan Mine (Fujian, China) exceeds 450 meters in height. As large-scale, artificially accumulated geotechnical bodies, these high-bench dumps present significant geological hazard risks. Their stability is paramount, directly influencing operational safety and the well-being of nearby personnel2.

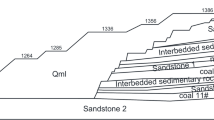

High-bench waste dumps formed by single-bench dumping typically exhibit particle size grading along the slope. This occurs as loose, granular soil-rock mixtures are discharged from the crest, allowing particles of varying sizes to roll freely downslope. Owing to differences in mass and momentum, larger particles possess greater kinetic energy and tend to accumulate in the lower sections of the slope. Conversely, smaller particles are more likely to be arrested in the upper portions. Consequently, the dump’s profile becomes segregated, with upper, middle, and lower sections predominantly composed of fine, medium, and coarse particles, respectively. This phenomenon, known as particle size grading3, results in both vertical segregation along the slope face and distinct horizontal stratification within the overall dump body. This internal structure is a key characteristic distinguishing high-bench dumps from conventional, lower-height dumps.

While slope stability analysis for dump sites is well-researched4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13, the unique particle size grading phenomenon in high-bench dumps has received limited attention. This internal heterogeneity is a critical differentiator from conventional dump slopes. Therefore, developing a stability analysis method that explicitly accounts for this grading characteristic is essential for accurate geotechnical assessment.

Particle arrangement in soil-rock mixtures is inherently random and heterogeneous14,15,16,17, meaning each prepared sample possesses a unique configuration. Because this arrangement critically influences shear strength, parameters derived from a limited number of mechanical tests may lack representativeness, yet extensive testing is often cost-prohibitive18. Numerical simulations can effectively supplement physical experiments, offering high efficiency and low cost. The discrete element method (DEM)19 is frequently applied, as it accurately captures the mechanical behavior of granular materials20,21,22. However, DEM is computationally expensive and requires significant resources. Furthermore, its particle-scale contact parameters necessitate careful calibration. In contrast, the fast Lagrangian analysis (FLAC), based on the finite difference method (FDM), provides rapid computation using parameters obtainable from conventional geotechnical tests23,24,25,26. Despite the utility of FDM, establishing a continuum model that adequately captures discrete particle arrangement and complex gradation remains challenging.

Cellular automata (CA) offer a framework for modeling the complex patterns and emergent behaviors seen in such systems. CA, originally proposed to simulate cellular self-replication, is a spatially and temporally discrete dynamic system27. In this system, cells evolve based on predefined local rules, where the state of each cell at a given time step is determined by the states of its neighbors in the previous step. Its discrete nature in time, space, and state makes CA well-suited for simulating the spatiotemporal evolution of complex systems, including the mechanical behavior of soil-rock mixtures28,29,30,31. However, existing CA applications typically use only two or three cell states. This simplification is insufficient to capture the broad-graded particle size distribution or the non-uniform, disordered particle arrangements found in these materials. To address this limitation, this study developed a Stochastic Evolution Program of Heterogeneous Materials (SEPHM). SEPHM is based on CA but expands the traditional two-state framework to five cell states. This extension allows the model to characterize soil-rock mixtures across five distinct particle groups, thereby more accurately reflecting field conditions.

This study utilized soil-rock mixtures from a high-bench dump in Jiangxi, China, as a case study. First, laboratory tests were conducted to obtain the mechanical parameters for the five distinct particle groups. Next, these parameters were used in numerical triaxial tests, conducted using the SEPHM-FDM coupled method, to determine the strength parameters for eight distinct soil-rock mixture layers identified within the dump. The statistical variation in these parameters, arising from discrete particle arrangements, was analyzed. A three-dimensional numerical model of the full-scale dump was then established to investigate the specific effects of particle size grading on slope stability. Based on these analyses, a novel framework for the stability analysis of high-bench dumps is proposed. This framework is intended to enhance the reliability of current slope stability assessment methods by incorporating the effects of material heterogeneity.

The high-bench dump

Overview of the dump

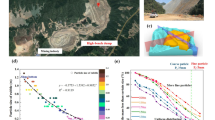

The soil-rock mixtures at a copper mine dump site in Jiangxi, China, consist primarily of materials from blasting excavation. The mixture is dominated by micro-weathered phyllite, with minor components of metamorphic tuffaceous siltstone and Quaternary topsoil. The dump, constructed via the single-bench dumping method, reaches a maximum slope height of 160 m.

Non-uniform settlement of these mixtures can cause internal deformation and crack development. As shown in Fig. 1, numerous visible cracks have formed on the dump’s top platform, accompanied by slippage at the slope shoulder. Owing to the dump’s recent construction, these cracks are incipient and relatively narrow. However, the potential for landslides triggered by external forces persists, posing significant safety hazards to nearby populations.

Particle size distribution

A survey line was established along the slope’s midline to determine the particle size distribution (PSD) of the soil-rock mixtures. Along this survey line, eight measurement points were designated at 20-meter intervals, as shown in Fig. 2.

The PSD curves for the soil-rock mixtures at each elevation, obtained via sieve analysis, are presented as the “original gradation curves” in Fig. 3. The curvature of the PSD curves indicates the coarse-grain content. As shown in Fig. 3, the coarse particle content (defined as particle size \(d > 5\) mm) decreases with increasing elevation, confirming the particle size grading phenomenon. To evaluate this phenomenon’s impact on stability, the numerical model was vertically stratified into eight 20-meter-high soil layers, corresponding to the measurement points.

The coefficient of uniformity (\(C_u\)) and the coefficient of curvature (\(C_c\)) are standard parameters used to characterize the gradation of soil-rock mixtures. These coefficients can be calculated from the gradation curves using Eq. 1. Generally, mixtures are considered well-graded if \(C_u \ge 5\) and \(1< C_c <3\); otherwise, they are classified as poorly graded. The \(C_u\) and \(C_c\) values for the mixtures at each elevation are presented in Table 1.

where \(d_{10}\), \(d_{30}\), and \(d_{60}\) are the particle diameters (mm) corresponding to 10%, 30%, and 60% finer by mass, respectively.

As shown in Table 1, the \(C_c\) values for mixtures in the upper part of the dump (\(H \ge 80\) m) are all less than 1. This is primarily attributed to the high fine-particle content in these layers, which reduces the skeletal support from coarse particles, resulting in a poorly graded mixture in this zone.

Scale of soil-rock mixtures

Given the large particle size of the mixtures (maximum particle size exceeding 300 mm), testing requires a large-scale triaxial apparatus. The testing principle is consistent with conventional triaxial tests, and the mechanical behavior is described by Eq. 2:

where \(\sigma _1\) and \(\sigma _3\) denote the maximum and the minimum principal stress (kPa), respectively; c is the cohesion (kPa); and \(\varphi\) is the internal friction angle (\(^{\circ })\). The subscript f represents the limiting state of failure.

To eliminate sample size effects on mechanical behavior, the sample diameter must be at least five times the maximum particle size32. Standard large-scale triaxial apparatuses typically have a 300 mm sample diameter, limiting the maximum testable particle size to 60 mm. Since the dump’s mixtures contain particles exceeding this limit, scaling is required for accurate mechanical property evaluation. In this study, the mixtures were scaled using the parallel grading method. This method proportionally reduces the original material to meet the apparatus’s particle size constraints while maintaining geometrically equivalent constraints, as expressed in Eq. 3. Notably, this method may increase the fine particle content to maintain consistent \(C_u\) and \(C_c\) values. The resulting scaled gradation curves are also shown in Fig. 3.

where \(d_{omax}\) is the maximum particle size of the original gradation (mm); \(d_{max}\) is the maximum particle size after scaling (mm); \(d_{oi}\) is a certain particle size of the original gradation (mm); \(d_{ni}\) is a certain particle size after scaling (%); \(P_{do}\) is the particles content smaller than a certain particle size in the original gradation (%); \(P_{dn}\) is the particles content smaller than a certain particle size after scaling (%).

SEPHM: an improved cellular automaton

Cellular automata (CA) models evolve cells through various states within a defined space according to local rules. These models consist of a cellular space and associated transformation functions. CA inherently exhibits both state discreteness (coexistence of multiple cell states) and spatial discreteness (cells generated on a discrete lattice). To leverage these characteristics, this study developed the cellular automata program Stochastic Evolution Program of Heterogeneous Materials (SEPHM). SEPHM utilizes these discrete features to approximate the heterogeneous particle distribution found in soil-rock mixtures.

SEPHM is implemented using five cell states, periodic boundary conditions, and an eight-neighbor configuration. The numerical model grid serves as the cellular space for cell evolution, with each grid element corresponding to one cell. The five states represent five distinct particle groups within the soil-rock mixture. Cell states are assigned using pseudo-random numbers generated by the linear congruential equation (Eq. 4). An example of the SEPHM evolution process is shown in Fig. 4. Initially, four cell types are randomly seeded at various positions within the cellular space. These cells then evolve and expand until each type reaches its predefined proportion. Finally, the fifth cell type is generated to fill all remaining unoccupied spaces.

where a, b, and m are integer constants, seed is the initial seed value, which depends on time, \(s_i\) is the state of the i-th cell, mod is the remainder operation, \(\equiv\) is the identity symbol.

The five cell states are used to represent the five particle groups within the soil-rock mixtures, enabling SEPHM to characterize the spatial distribution of each particle size.

The evolution results are illustrated for a case where each of the five cell states comprises 20% of the total. As shown in Fig. 5, despite this uniform proportion, the resulting spatial distribution is highly disordered and inhomogeneous.

Numerical triaxial test

This section investigates the influence of particle size grading on the shear strength of the dump’s soil-rock mixtures. Extensive numerical triaxial tests were conducted using the coupled SEPHM-FDM method, simulating the specific gradation of each dump layer. This approach also allowed for an examination of how disordered particle distribution (i.e., random spatial arrangement) impacts shear strength parameters.

In the coupled SEPHM-FDM methodology, the numerical model grid serves as the SEPHM cellular space. The cell state at each lattice point is assigned to its corresponding FDM element. Each state represents a specific particle group: State 1 (\(d \le 5\) mm), State 2 (\(5 < d \le 10\) mm), State 3 (\(10 < d \le 20\) mm), State 4 (\(20 < d \le 40\) mm), and State 5 (\(40 < d \le 60\) mm). This method establishes a numerical triaxial sample that accounts for the heterogeneous spatial distribution of particles.

Numerical triaxial sample

The numerical sample was a cylinder (300 mm diameter, 600 mm height). The model applied a fixed constraint at the bottom, a radial confining pressure (\(\sigma _c\)), and a constant downward velocity (\(v = 5 \times 10^{-7}\) m/s) at the top, as illustrated in Fig. 6a

Figure 6b illustrates how samples with identical gradation can exhibit different internal structures due to random particle distributions, which in turn leads to strength parameter deviations. The generated samples effectively capture this random and heterogeneous distribution.

Eight groups of numerical triaxial samples were prepared, with gradations corresponding to the eight dump layers, as illustrated in Fig. 7. As noted, fine particle content increased with elevation. To account for the influence of random particle arrangement on strength, 50 unique samples (identical gradation but varied particle distributions) were generated for each of the eight groups, totaling 400 samples.

Using the material parameters in Table 2 and the Mohr-Coulomb model, consolidated drained triaxial compression tests were simulated for each sample.

Numerical triaxial test results

First, a large-scale laboratory triaxial test was conducted to validate the numerical method. The physical sample was taken from the 0 m \(\le H < 20\) m layer. Figure 8 compares the stress-strain curves from the numerical simulation and the laboratory test under 400 kPa confining pressure. An axial strain of 15% was adopted as the failure criterion, as the stress-strain curve exhibited a hardening behavior32.

Figure 8 shows that the numerical simulation effectively reproduces the stress-strain response of the actual soil-rock mixture and accurately captures the bulging deformation and failure modes. A discrepancy exists in the initial stage, where the simulated tangent slope is greater. This is attributed to the physical test’s initial compaction phase (particle dislocation before significant stress increase), a process the constitutive model does not fully represent, leading to a more rapid initial stress increase in the simulation.

Numerical triaxial tests were then conducted on all 400 samples. The resulting cohesion (c) and internal friction angle (\(\varphi\)) values are presented in Fig. 9. Both c and \(\varphi\) decrease with increasing elevation (i.e., higher fine particle content). Significant dispersion is evident within each sample group. The coefficients of variation (CV) for c (0.60–1.07%) were greater than for \(\varphi\) (0.19–0.30%). This is likely because \(\varphi\) is primarily governed by inter-particle friction, whereas c is closely related to particle interlocking. Since the random spatial distribution directly influences interlocking, it has a more pronounced effect on c.

To characterize the variability of the shear strength parameters, the distributions of c and \(\varphi\) within each group were statistically analyzed. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test was employed to determine the best-fitting distribution among three common models: normal, log-normal, and Weibull33,34,35,36. The K-S statistic quantifies the maximum discrepancy between the empirical data and a fitted theoretical distribution; consequently, a smaller statistic indicates a better fit. Furthermore, a p-value greater than 0.05 is typically required to confirm that the data is compatible with the tested distribution. Based on a comparison of the K-S statistics, the normal distribution was found to provide a superior fit over the log-normal and Weibull models. As shown in Table 3, all p-values were significantly greater than the significance level (\(\alpha =0.05\)), indicating that c and \(\varphi\) for each dump layer follow a normal distribution.

The mean (\(\mu\)) and standard deviation (\(\sigma\)) of the normal distribution describe the central tendency and dispersion, respectively, and are summarized in Table 3. As shown, with increasing elevation and fine particle content (\(d \le 5\) mm), the mean cohesion decreases from 62.87 to 53.58 kPa (a 14.8% reduction). The mean friction angle decreases from 24.88\(\phantom{0}^{\circ }\) to 21.51\(\phantom{0}^{\circ }\) (a 13.5% reduction). The standard deviations for both parameters also generally decrease with elevation, albeit with some fluctuations.

Figure 10 provides an example using the 60m \(\le H < 80\) m layer, plotting the frequency histograms for c and \(\varphi\) against their fitted normal distribution curves. The fitted curves show a strong alignment with the frequency histograms for both parameters.

Slope stability analysis of the high-bench dump

Although previous analyses revealed shear strength variations in soil-rock mixtures at different elevations due to particle size grading, incorporating these variations into the stability analysis framework remains challenging. A simple horizontal stratification of the dump fails to capture the anisotropy induced by the heterogeneous particle distribution. Therefore, this section proposes a numerical stability analysis method for high-bench dumps, integrating SEPHM with FDM to address this limitation.

Numerical modeling of dump considering particle size grading

A three-dimensional numerical model was established based on the dump’s actual conditions. The particle distribution, evolved using SEPHM to represent the actual gradation in each layer, was then incorporated into the model. As shown in Fig. 11, the fine particle content (\(d \le 5\) mm) increases with elevation. The model effectively captures the heterogeneous particle distribution across the dump’s layers.

The model (1200 m \(\times\) 1200 m \(\times\) 300 m) consists of 730,898 tetrahedral elements and 135,605 nodes. Normal constraints were applied to the lateral surfaces, fixed constraints to the bottom, and the upper surface was a free boundary. The model computed displacement under gravity, and the slope safety factor was determined using the strength reduction method.

Stability analysis results

Figure 12 presents the Z-direction displacement contour. Displacement is concentrated in the upper dump slope, forming enclosed contours. A distinct, high-gradient concentration zone is evident at the highest slope section (corresponding to the Fig. 2 survey line), with maximum displacement at the crest. These results indicate deformation is predominantly shear deformation in the upper regions. The potential slip surface extends from the top platform, propagates downward, and exits through the slope face. This behavior is consistent with the field-observed crack development (Fig. 1), validating that the proposed analysis method captures actual site conditions.

To quantify the impact of grading, a comparative analysis was performed. When grading is neglected, the dump is treated as a homogeneous (non-stratified) mass. In this non-stratified case, the mid-slope gradation is typically adopted. Accordingly, parameters were based on the mean values from the 60m \(\le H < 100\)m elevation range.

Calculation results under two conditions: (a) Displacement of dump considering particle size grading (unit: m); (b) Displacement of dump without considering particle size grading (unit: m); (c) Tension plastic zone of dump considering particle size grading; (d) Tension plastic zone of dump without considering particle size grading; (e) Slip surface of dump considering particle size grading; (f) Slip surface of dump without considering particle size grading.

Figure 13 compares the simulation results. Accounting for grading substantially impacts the results. The Z-direction displacement contours (Fig. 13a, b) show displacement is concentrated in the upper dump, decreasing in a fan-shaped pattern. The displacement in the non-graded model is significantly larger and more widespread. Specifically, the maximum displacement increases by 90.3% (from 0.175 to 0.333 m) when grading is ignored.

The tensile plastic zones (Fig. 13c, d) are concentrated near the crest. Considering particle size grading reduces the tensile zone volume by 61.5% (from \(103.6 \times 10^3\) to \(39.9 \times 10^3 m^3\)). This indicates that grading reduces the potential tensile cracking zone.

Particle size grading, therefore, reduces dump deformation and mitigates the extent of damage at the limit state. Neglecting this phenomenon results in an overestimation of both displacement and the plastic zone extent.

Figure 13e and f show the calculated slope stability. In the limiting state, a landslide-type failure occurs along the maximum-height slope. Particle size grading shifts the slip surface upward, reducing the slip volume. The safety factor for the graded model (1.43) is 6.7% higher than for the non-graded model (1.34). These results indicate that the horizontal stratification induced by grading enhances slope stability. Neglecting this effect underestimates the true safety factor.

Discussion

The proposed stability analysis method offers significant practical and engineering advantages. First, it addresses the economic and logistical challenges of parameter acquisition for heterogeneous soil-rock mixtures. Conventional methods require extensive large-scale triaxial tests (e.g., one for each of the eight layers). In contrast, our method characterizes only the five constituent particle groups, reducing the laboratory testing requirement by 37.5%. Second, it provides a more realistic stability assessment for engineering design. The results show that homogeneous models, which neglect particle size grading, are overly conservative safety factor compared to the proposed stratified model. This underestimation can lead to costly over-design, such as unnecessarily gentle slopes or excessive reinforcement. By accounting for the stabilizing effect of stratification, our method provides a scientific basis for optimizing dump design, thereby maximizing capacity and reducing land use while ensuring safety.

The proposed numerical approach has two primary limitations, inherent to its continuum-based framework. First, it cannot fully capture micro-scale behaviors (e.g., particle rolling, compaction) during initial loading, leading to inaccuracies in the early-stage stress-strain response. However, as Fig. 8 indicates, the model accurately reproduces the critical peak strength and strain-hardening characteristics. Given that stability is governed by material strength, not initial stiffness, this limitation has a negligible impact on the final stability analysis. Second, a disparity exists between the numerical grid element volume and the actual particle size, a result of the ”homogenization” that assigns continuum properties to each element. This issue is mitigated in this large-scale application, as the 5–7 m grid elements are voluminous enough to represent a multi-particle aggregate of a given size class. Thus, the model validly captures macroscopic heterogeneity and failure mechanisms. Future research could focus on addressing these issues to achieve a more refined simulation of high-bench dumps.

Conclusions

Based on an engineering case study, this study proposed a stability analysis method for high-bench dumps that integrates SEPHM and FDM. The method was used to investigate the influence of particle spatial distribution on the strength of soil-rock mixtures and to evaluate the effect of particle size grading on dump stability. The primary conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

The particle size distribution curves of the soil-rock mixtures at different elevations within the high-bench dump indicate that the content of fine particles (\(d \le 5\) mm) increases with elevation, demonstrating a clear particle size grading phenomenon. The soil-rock mixtures in the upper sections of the dump exhibit poor gradation characteristics due to the excessive content of fine particles.

-

(2)

The SEPHM effectively characterizes the heterogeneity and random distribution of particles within soil-rock mixtures. The combined SEPHM-FDM method proposed in this study enables the particle size grading characteristics and random particle distribution to be accurately incorporated into the numerical stability analysis of high-bench dumps, providing a closer representation of actual dump conditions.

-

(3)

Even under identical gradation conditions, the cohesion c and internal friction angle \(\varphi\) of soil-rock mixtures exhibit notable interval dispersion due to variations in particle arrangement, with both parameters following a normal distribution. The coefficient of variation for c is higher than that for \(\varphi\), indicating a greater degree of variability in c. Additionally, the mean values of both c and \(\varphi\) decrease as the fine particle content increases.

-

(4)

The stability analysis results of high-bench dumps are significantly affected by whether the particle size grading phenomenon is considered. Compared to analyses that disregard this phenomenon, incorporating particle size grading results in a 47.5% reduction in maximum slope displacement (from 0.333 to 0.175 m) and a 61.5% reduction in the volume of the tension zone (from \(103.6 \times 10^3\) to \(39.9 \times 10^3 m^3\)). Additionally, the safety factor is increased by 6.7% (from 1.34 to 1.43), and the slip surface shifts upward. These results indicate that the effects of particle size grading should be fully accounted for in the stability analysis of high-bench dumps.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zevgolis, I. E. et al. Geotechnical characterization of fine-grained spoil material from surface coal mines. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 147, 04021050. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0002550 (2021).

Liu, S., Zhao, H. & Wang, M. Research on the acoustic emission characteristics and instability correlation effect of the dynamic response of waste dump slopes. Sci. Rep. 15, 947. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85110-2 (2025).

Wang, G., Kong, X. & Yang, C. Research on the representation of granular vertical size grading and numerical simulation method with the typical waste rock site. Tehnički vjesnik 22, 677–683, https://doi.org/10.17559/TV-20150428103311 (2015)

Bao, Y. et al. Numerical assessment of failure potential of a large mine waste dump in Panzhihua City, China. Eng. Geol. 253, 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2019.03.002 (2019).

Wang, Y., Sun, S., Pang, B. & Liu, L. Base friction test on unloading deformation mechanism of soft foundation waste dump under gravity. Measurement 163, 108054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2020.108054 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. Stability of inner dump slope and analytical solution based on circular failure: Illustrated with a case study. Comput. Geotech. 117, 103241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2019.103241 (2020).

Wei, T. et al. Shear strength and microstructure of silty clay subjected to caso4 solution and stability effect on a gypsum dump. Bull. Eng. Geol. Env. 80, 4143–4157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-021-02196-4 (2021).

Bharati, A. K., Ray, A., Rai, R. & Shrivastva, B. A stability classification system for the dragline dump slope. Min., Metall. & Explor. 38, 1095–1109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42461-019-0097-z (2021).

Dong, J., Jiang, H., Yang, D. & Gao, K. Safety assessment of slope on in-service dump under severe dry-wet cycles at high-altitude. Sci. Rep. 13, 16992. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-44002-z (2023).

Liang, Z. et al. Three-dimensional stability calculation method for high and large composite slopes formed by mining stope and inner dump in adjacent open pits. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 34, 507–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2024.04.007 (2024).

Cui, B., Bi, Y., Gu, T. & Han, K. Study on the characteristics particles of coarse grain material in high bench dump. Sci. Rep. 14, 23847. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75255-x (2024).

Chen, C. et al. Quasi-3d slope stability analysis of waste dump based on double wedge failure. Sci. Rep. 14, 6887. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56637-7 (2024).

Mu, H. Research on the disaster mechanism and control technology of large section high waste dump slope in open pit mines. Sci. Rep. 15, 8909. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93268-y (2025).

Gao, S. et al. Mechanical properties of material in a mine dump at the Shengli #1 surface coal mine, China. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 27, 545–550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2017.03.014 (2017).

Cui, Y. Mechanical behaviour of coarse grains/fines mixture under monotonic and cyclic loadings. Transp. Geotech. 17, 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trgeo.2018.09.016 (2018).

Chen, X., Xie, K., Li, T. & Zhang, Q. Investigation on the coarse-grained rearrangement of vibratory compaction in the high-speed railway graded aggregate materials. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 19, e02385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02385 (2023).

Zhou, H., Zhou, Y. & Lei, L. Full grading detection method of earth-rock materials by combining preliminary screening and video image recognition. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2025.e04778 (2025).

Hao, S. & Pabst, T. Mechanical characterization of coarse-grained waste rocks using large-scale triaxial tests and neuroevolution of augmenting topologies. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 149, 04023039. https://doi.org/10.1061/JGGEFK.GTENG-10721 (2023).

Cundall, P. A. & Strack, O. D. A discrete numerical model for granular assemblies. Geotechnique 29, 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.1979.29.1.47 (1979).

Wang, Y., Zhao, M., Li, S. & Wang, J. Stochastic structural model of rock and soil aggregates by continuum-based discrete element method. Sci. China Ser. E Eng. & Mater. Sci. 48, 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1360/04zze13 (2005).

Xu, W., Hu, L. & Gao, W. Random generation of the meso-structure of a soil-rock mixture and its application in the study of the mechanical behavior in a landslide dam. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 86, 166–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2016.04.007 (2016).

Xu, W., Wang, S., Zhang, H. & Zhang, Z. Discrete element modelling of a soil-rock mixture used in an embankment dam. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 86, 141–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2016.04.004 (2016).

Li, C., Zhang, D., Du, S. & Shi, B. Computed tomography based numerical simulation for triaxial test of soil-rock mixture. Comput. Geotech. 73, 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2015.12.005 (2016).

Zou, Y., Zhang, J. & Wang, R. Seismic analysis of stone column improved liquefiable ground using a plasticity model for coarse-grained soil. Comput. Geotech. 125, 103690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2020.103690 (2020).

Khashila, M., Hussien, M. N., Chekired, M. & Karray, M. On the dynamic soil behavior under triaxial and simple shear modes. Int. J. Geomech. 21, 04021134. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GM.1943-5622.0002085 (2021).

Khashila, M., Hussien, M. N., Karray, M. & Chekired, M. Liquefaction resistance from cyclic simple and triaxial shearing: A comparative study. Acta Geotech. 16, 1735–1753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-020-01104-6 (2021).

v Neumann, J. & Burks, A. W. Theory of self-reproducing automata (University of Illinois Press Urbana, 1966).

Xu, D., Wang, B., Jiang, L. & Cao, Z. Study of methods of triaxial numerical simulation test of glacial till. Rock and Soil Mechanics 29, 3466–3470, https://doi.org/10.16285/j.rsm.2008.12.028 (2008)

Shi, C., Xu, W., Zhang, Y., Li, D. & Liu, H. Study of dynamic parameters for talus deposit based on model of cellular automata. Rock and Soil Mechanics32, 1796–1800, https://doi.org/10.16285/j.rsm.2011.06.021 (2011).

Wang, L., Xu, W. & Xu, A. Three-dimensional cellular automata based particle flow simulations of mechanical properties of talus deposit. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 4, 375–384. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1235.2012.00375 (2012).

Ai, X. et al. The scale effect of coarse-grained materials by triaxial test simulation. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 6665531. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6665531 (2021).

Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of China. Standard for geotechnical testing method GB/T 50123-2019 (China Planning Press (in Chinese), Beijing, 2019).

Burton, A., Arkell, T. J. & Bathurst, J. Field variability of landslide model parameters. Environ. Geol. 35, 100–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002540050297 (1998).

Liao, M., Lai, Y., Yang, J. & Li, S. Experimental study and statistical theory of creep behavior of warm frozen silt. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 20, 2333–2344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-015-0374-4 (2016).

Wang, Y., Liu, J., Yan, S., Yu, L. & Yin, K. Estimation of probability distribution of shear strength of slip zone soils in middle Jurassic red beds in Wanzhou of China. Landslides 14, 2165–2174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-017-0890-z (2017).

Wang, B., Liu, K., Wang, Y. & Jiang, Q. Site investigations of the lacustrine clay in Taihu lake, China, using self-boring pressuremeter test. Sensors 21, 6026. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21186026 (2021).

Funding

No financial support was received by the authors in this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiaotao Ai: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Original Draft. Yicheng Chen: Investigation, Data curation. Yuzhou Huang: Supervision, Writing—Review & Editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ai, X., Chen, Y. & Huang, Y. Stability evaluation of high-bench dumps considering the effects of disordered particle arrangements. Sci Rep 16, 2388 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32032-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32032-8