Abstract

This study looks at how likely landslides are to happen in Souk Ahras, eastern Algeria. This area is known for having unstable slopes and landslides that damage property and crops and move people out of their homes. The study uses remote sensing and Geographic Information System (GIS) methods along with two predictive models, the Frequency Ratio (FR) and the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP), to find and map locations that are likely to have landslides. Nine things that could have caused the problem were looked at, such as slope, rock type, height, rainfall, and how far away it was from faults, rivers, and roadways. There were 248 historical landslide incidents found, and 60% of them were utilized to train the model and 40% to check its accuracy. Using ArcGIS 10.8, the landslide susceptibility index (LSI) was divided into five classes of susceptibility. IDRISI Selva 17.0 was used to figure out the weights of the factors. The FR model said that 26.03% of the region was very likely to be affected, while the AHP model noted that 9.06% was very likely to be affected and 4.63% was highly likely to be affected. The FR and AHP models were found to be 77% and 68% accurate, respectively, according to the validation analysis. The FR model did a better job of predicting what would happen because it used data from past landslides. On the other hand, subjective weight allocations affected how well the AHP model worked. These maps of landslide susceptibility are essential for managing land and preventing disasters. They help people in Souk Ahras make wise choices by showing them where areas are most in danger.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Landslides, defined as the downslope movement of rocks, soil, or debris under the influence of gravity, are among the most destructive geological hazards on Earth 1,2,3,4,5. They pose significant threats to human life, infrastructure, cultural heritage, and natural ecosystems 2,6,7,8. Landslides result from complex interactions between natural factors such as climate, terrain, soil, and vegetation cover, as well as anthropogenic activities including inadequate slope management, industrial operations, and deforestation 2,4,9 Areas with steep slopes, high rainfall, and seismic activity, such as the Americas, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and parts of Africa, are particularly vulnerable 3,10,11,12. Unsustainable land use, deforestation, and rapid urban expansion further increase landslide risk, which not only damages infrastructure but also disrupts livelihoods and economic activities. Climate change is expected to exacerbate both the frequency and intensity of these events 13,14,15,16,17. In Algeria, landslides occur frequently and cause significant damage to railways, roads, bridges, buildings, drainage systems, and agricultural lands. They also represent a major cause of human and animal fatalities 16,18,19,20,21. The northern, northeastern, central, and northwestern highlands are especially prone to landslides due to their rugged rocky topography, high relief energy, diverse slope materials, and intensive human activity 2,4,7,22. These highlands are home to nearly 70% of Algeria’s population 2,3,22. Landslide susceptibility is further aggravated by tectonic fractures, faults, colluvial–alluvial deposits at slope bases, and heavy rainfall, which can trigger both rapid and slow-moving events 4,12,23,24. Notable cases include the 2018 Souk Ahras landslide, which injured 30 people, displaced 200 families, and caused widespread damage to cultivated and uncultivated land 1,25, as well as the September 4, 2021, railway landslides affecting 13 sites in the same region. Previous studies have primarily focused on localized landslide monitoring and mapping in Souk Ahras, particularly in Zaarouria and Taoura. This study aims to overcome these limitations by developing a landslide susceptibility map for the entire province. Slope stability and ground displacement are critical to landslide initiation. Steeper slopes are inherently less stable under gravitational forces. Lithology, soil texture, and cohesion strongly influence slope resistance, soils with high clay content or low cohesion are particularly vulnerable. Similarly, weak or fractured rocks are highly susceptible to failure, and slope stability is further affected by rock strength, fracture density, proximity to rivers, and weathering processes 12,24,26,27. Water plays a key role, as increased saturation raises pore pressure and reduces shear strength, especially during heavy or prolonged rainfall 28,29,30. Loss of vegetation through deforestation or urban development further destabilizes slopes, amplifying landslide risk 31,32,33. Topographic zoning based on instability factors supports the identification of high-risk areas and facilitates targeted mitigation strategies 12,34,35. Recent advances in Earth Observation Systems (EOS), remote sensing, and GIS provide precise data acquisition and improve geohazard assessments 36. Statistical and multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) approaches are widely applied in landslide susceptibility mapping. Bivariate methods, including Frequency Ratio (FR), Weighted Overlay Model (WoM), Weights of Evidence (WoE), and Information Value (IV), quantify the relationship between past landslides and conditioning factors 37,38. Multivariate approaches, such as the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), assign weights to factors based on expert judgment supported by consistency checks 39,40,41,42. Hybrid models combining AHP with machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) methods including Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), Decision Trees, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Random Forests (RF), and Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM) have further improved predictive accuracy by capturing nonlinear interactions among conditioning factors 28,31,32,43,44,45. This study seeks to identify the primary factors contributing to landslides in Souk Ahras, Algeria, including slope, lithology, soil type, distance to faults, distance to rivers, elevation, rainfall, NDVI, land use/land cover (LULC), and distance to roads. The FR and AHP models are applied to evaluate landslide probability, delineate susceptibility zones, validate predictions against historical events, and identify areas of high to very high risk. The FR model directly links past landslide occurrences to conditioning factors, while the AHP model provides a structured framework for weighting multiple factors using expert knowledge 46,47,48,49. Both methods have demonstrated reliability in Algerian highlands, even under conditions of limited data availability 12,50,51,52,53,54,55. The novelty of this study lies in integrating FR and AHP within a single susceptibility assessment for Souk Ahras Province an approach not previously undertaken at the provincial scale. By combining the statistical rigor of FR with the structured decision-making of AHP, the research bridges the gap between data-driven and expert-driven methodologies. This dual framework not only enhances predictive accuracy but also provides a more comprehensive understanding of factor interactions in a region characterized by complex lithology, active tectonics, and significant anthropogenic pressure. The approach carries both scientific and practical relevance, as it improves methodological robustness, informs disaster risk management strategies, and supports land-use planning in one of Algeria’s most landslide-prone regions. Furthermore, the findings offer a methodological reference for other vulnerable regions in North Africa and beyond, where integrating statistical and decision-analytic techniques can significantly advance geohazard assessments.

Area of study

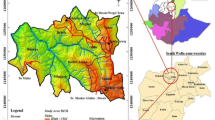

The Souk Ahras Province lies in northeastern Algeria and covers an area of 4,360 square kilometers. The province’s terrain is predominantly mountainous, forming part of the Tellian mountain belt that extends across the region. Steep slopes are widely distributed throughout the landscape, with elevations ranging from 675 to 1,283 m above sea level. Elevation decreases gradually from the northeast toward the southwest 1,2,6,56,57. Souk Ahras has a Mediterranean climate of the sub-humid type. Winters are cold and wet, whereas summers are hot and dry. The region receives an average annual rainfall of 428 to 460 mm, which contributes to a high probability of intense precipitation events. Due to its geomorphology, climate, and geological setting, Souk Ahras is highly susceptible to landslides. These events occur frequently in the province, particularly in areas with unstable slopes (Fig. 1).

Geology of study area

Souk Ahras lies within the Tellian region and is characterized by diverse lithological units and significant tectonic activity 1,2,58. The province is part of the North African Alpine ranges, which developed through the convergence of the African and European plates a few million years ago (Fig. 2). According to 1, 6 the sedimentary strata underlying Souk Ahras range from the Mesozoic to the Cenozoic. The western mountains are primarily composed of Jurassic limestone and dolomite, producing a highly irregular relief. Cretaceous marl and clay occur across both flat and steep areas, however, their weak cohesion makes them highly susceptible to erosion and landslides. In parts of the south and east, Miocene sandstones and conglomerates are present, whereas Quaternary deposits dominate the plains and riverbeds. These deposits, consisting mainly of alluvial and colluvial formations, provide evidence of the geomorphological changes that have shaped the region over time 1,6,59,86,88. The complex tectonic processes associated with the Alpine orogeny have significantly influenced the region’s geological structure. Reverse faults and thrusts, oriented predominantly in a NE–SW direction, indicate strong compressional forces resulting from plate interactions. Well-developed anticlinal and synclinal folds in the mountainous sectors further demonstrate the impact of tectonic stresses on rock deformation 1,6. The Oued Medjerda River, a major hydrographic system in the province, forms the central axis of the drainage network. Interactions between this fluvial system and weak geological units, such as marl and clay, frequently give rise to erosion and landslide processes 1,6.

Data and methods

The first step in landslide susceptibility analysis is the construction of a landslide inventory 17,47,55,60. The initial task of this study was to produce an inventory map for the province of Souk Ahras. Data were compiled through interpretation of Google Earth imagery and by conducting field surveys along the rail network. The study considered nine primary conditioning factors: slope, lithology, distance to faults, distance to rivers, elevation, precipitation (rainfall), NDVI, land use/land cover (LULC), and distance to roads. These conditioning factors affect slope stability and can increase the likelihood of mass movement 55,61,62,94. Thematic layers were generated for each factor and combined using weights derived from the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to produce the landslide susceptibility map 62. Subsequently, a weighted linear combination was performed within the GIS environment to integrate all factor layers into the final susceptibility model 47,55.

Data and sources

This study employed a broad set of data sources and methodologies to map and analyze landslide susceptibility in the Souk Ahras region. To ensure reproducibility, detailed descriptions of the datasets, their quality, and preprocessing steps are provided. Primary data were derived from Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) at 12.5 m resolution obtained from the Alaska Satellite Facility and from Sentinel-2 imagery at 10 m resolution provided by the European Space Agency (ESA). These datasets were used to extract key topographic variables, including slope, elevation, and river (drainage) networks. Additional geological and thematic information was obtained from the Geological Survey of Algeria (ASGA), while climatic data were supplied by the Regional Meteorological Agency (RMA). Land use/land cover (LULC) and NDVI indices were produced from Sentinel-2 imagery, road networks were digitized from Google Earth, fault and lithology data were extracted from ASGA geological maps, and historical landslide locations were compiled from detailed field surveys. These heterogeneous datasets required careful preprocessing, including reprojection, resampling to a common spatial resolution, and normalization of factor layers prior to model integration. The preprocessing workflow comprised DEM-derived factor extraction (slope, elevation, river networks), atmospheric correction and classification of Sentinel-2 imagery for LULC and NDVI, and digitization of linear features (roads, faults). Rainfall and lithological data were georeferenced and integrated into the GIS environment, and data harmonization ensured consistent coordinate reference systems and spatial resolution across all factors. For analysis, the following software tools were employed: ArcGIS 10.8 for spatial analysis and mapping, ENVI 5 for image preprocessing and classification, Geomatica 2015 for lineament extraction, and IDRISI Selva 17.0 for Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) weight computation. This systematic workflow enabled consistent factor mapping and reproducible landslide-susceptibility modeling for Souk Ahras.

Landslide inventory data

There are two significant steps in evaluating landslide susceptibility. First, it is necessary to identify and assess areas prone to landslides. Second, detailed maps must be produced to document both past and present events, providing a reliable foundation for future analysis. This structured approach involves a combination of field surveys, interpretation of satellite imagery, and examination of historical records. Such methods are essential for constructing accurate landslide inventories, which form the basis of reliable susceptibility mapping. In this study, a comprehensive field survey was conducted to generate a detailed landslide inventory map for Souk Ahras. Data were collected from 248 landslide sites, of which 148 (60%) were used for model training and 100 (40%) for validation. Fieldwork was complemented by high-resolution Google Earth imagery, GPS-based mapping of landslide boundaries, and interviews with local residents to integrate historical knowledge. Areas most susceptible to landslides such as steep slopes, river valleys, and zones of severe soil degradation were carefully inspected to ensure a representative dataset. However, the landslide inventory is subject to certain limitations. Historical records often lack precise spatial and temporal information, creating uncertainty in the exact location and timing of events. Variability in image resolution and interpretation from Google Earth can also introduce positional inaccuracies. Furthermore, landslides in remote or inaccessible areas may remain undocumented, resulting in heterogeneity within the dataset. These limitations may affect the completeness and reliability of the inventory. Despite these challenges, the integration of field-based observations, satellite image interpretation, and community knowledge provided a sufficiently robust dataset to support statistical modeling. The inventory data were systematically organized and analyzed in ArcGIS using the geostatistical analysis toolkit. Approximately 60% of the data were used to calculate Frequency Ratio (FR) values for each causative factor class, while the remaining 40% were reserved for validation in both FR and Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) models. This division ensured balanced model development and reliable performance evaluation, while also highlighting the importance of addressing inherent limitations in landslide inventory data (Fig. 3).

Methods

This study followed a systematic workflow that integrated data collection, preprocessing, factor mapping, and implementation of the Frequency Ratio (FR) and Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) models (Fig. 4). Landslide data were compiled through a combination of field surveys, analysis of Google Earth imagery, and review of official records. By merging field observations with high-resolution imagery, a comprehensive landslide inventory was constructed and divided into two subsets: 70% for model training and 30% for validation, ensuring an unbiased assessment of model performance. A detailed literature review, field investigations, and expert consultation identified nine causal factors strongly influencing slope stability in the study area: elevation, slope, distance from rivers, distance from faults, lineaments, lithology, soil type, land use/land cover (LULC), Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), and rainfall. These factors were selected because they represent the geomorphological, hydrological, geological, and anthropogenic drivers of landslides, and their significance has been demonstrated in previous studies. Preprocessing and mapping of conditioning factors were carried out using multiple geospatial and remote sensing tools. Topographic factors (elevation, slope, and distance from rivers) were derived from DEM data in ArcGIS 10.8. Geological data, including faults and lithology, were obtained from the Souk Ahras geological map, while lineaments were extracted using the Geomatica 2015 LINE module. LULC and NDVI maps were generated by classifying Sentinel-2B imagery with 10 m resolution, and rainfall data were collected from the Souk Ahras meteorological station. Lithology layers were digitized from existing geological maps. All datasets were standardized to a common projection (UTM Zone 32N) and resampled to a uniform pixel size of 12.5 × 12.5 m to ensure spatial consistency. Each factor was then classified into subclasses using natural breaks, manual classification, and expert judgment, which formed the basis for calculating statistical values, factor weights, and spatial distributions. The FR model was implemented by calculating the frequency ratio for each subclass of conditioning factors using the training landslide dataset. This quantified the relationship between landslide occurrence and each factor. In parallel, the AHP model was implemented in IDRISI Selva 17.0 and ArcGIS 10.8. Pairwise comparison matrices were constructed by experts, consistency ratios were verified, and factor weights were derived to represent the relative contribution of each parameter to landslide occurrence. For both models, a Landslide Susceptibility Index (LSI) was calculated, and the resulting maps were classified into five susceptibility zones (very low to very high) using statistical thresholds and expert evaluation. The predictive accuracy of both models was evaluated using the validation subset of the landslide inventory. Although hybrid machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) techniques are increasingly applied in recent studies, FR and AHP were selected in this research because they are robust, transparent, and interpretable in data-scarce environments such as the Algerian highlands. These models require fewer computational resources, are less data-intensive than ML/DL approaches, and provide clear insights into the contribution of each factor. Furthermore, previous research has shown that FR and AHP perform reliably for regional-scale susceptibility mapping, making them a practical and scientifically rigorous choice for landslide hazard assessment in Souk Ahras (Table 1).

Frequency ration (FR) model

The Frequency Ratio (FR) method has been used a lot by scientists to find places where landslides are likely to happen. This method is suitable for finding out how landslides are connected to critical factors, which include slope, lithology, and distance from faults 63,64. The FR model is helpful in places where there is not much data. Based on data from prior landslides, these factors are given varied levels of importance. This helps make predictions more precise 28,29,30. The strategy is based on the assumption that landslides are likely to happen again in sites where they have happened previously. This makes it a valuable way to locate places that are in danger 36. The model demonstrates how the location of landslides, the items that trigger them, and the number of landslides in different groups are all connected. Using the equation below (Eq. 1) 62.

% a is the percentage of landslides that happen, % b is the percentage of pixels in each subclass, and FRv is the frequency ratio value.

Analytical hierarchy process (AHP) model and landslide susceptibility index (LSI)

We employed the AHP method to find out how significant each factor and sub-factor was in generating landslides in Souk Ahras province 65,66,67,68,69,70. AHP is a means to make judgments that help with problems that have more than one goal and more than a single criterion. It does this by offering you a scale instead of making you choose from a list of options 71,72,73,74. researchers commonly use this method to figure out how probable a landslide will occur since it helps them understand problems and identify the best way to fix them. The AHP method has some critical steps. Some of these are building a hierarchical structure for the analysis, comparing the criteria to the goal in pairs, making a comparison matrix, finding the most significant vectors, and figuring out the random index (RI), the average value (λmax), the consistency index (CI), and the consistency ratio (CR). The following steps are to create a comprehensive comparison of the chart for the criteria, set up sub-criteria, create a comparison table for sub-criteria, figure out the value that each criterion adds, add up the project values, evaluate alternatives in pairs, and create a complete comparison table for the alternatives 3,10,11,12. The total of all the project values is what the final decision is based on, as shown in Table 2. We used the random index (RI) values in Eq. (1) to find the consistency ratio (CR), which showed that the results were reliable (see Table 3). This phase makes sure that the weights given to the criteria are correct 65. The goal of figuring out the CR is to find any differences in the comparisons of pairs of criteria. According to Eq. (1), the CR is a significant mathematical measure for judging how reliable the decision-making process is.

where (RI) is the random coherence index and (CI) is the coherence index expressed in Eq. (2).

The value (λmax) represents the principal eigenvalue of the matrix, which is calculated from the matrix itself, while (n) denotes the matrix’s order. As per Saaty, the consistency ratio should not exceed 10% or have an imprecision greater than 10%. This approach relies on comparing judgments against randomly assigned weights for the elements. Ultimately, the calculated weights have been consolidated into various triggered classes to form a single landslide susceptibility index, using Eq. (3).

where (Ri) is the rating classes for each layer and (Wi) is the weights for each landslide conditioning factor.

The resulting landslide susceptibility map was classified into five classes (very low, low, moderate, high and very high) based on natural discontinuities to define the class intervals in the landslide susceptibility map.

Preparation of landslide causative factors

The study evaluates several key factors contributing to landslide occurrences, including Slope, lithology, distance from faults, distance from river, elevation, rainfall, NDVI, land use/land cover, and distance from roads. Each of these factors is discussed in detail in the following sections.

Slope

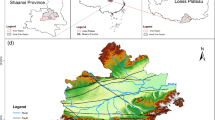

It is well established that the steeper the slope, the higher the probability of landslide occurrence. This is because steep slopes impose greater gravitational stress on slope materials, making them more prone to instability 15,16,17. In the study area, steep slopes significantly increase the likelihood of landslides, as gravitational forces more effectively mobilize soil and rock, particularly where friction and cohesion are low. The ALOS PALSAR Digital Elevation Model, with a high spatial resolution of 12.5 × 12.5 m, was employed to calculate slope steepness across the research region. Slope values were classified into six categories 16,19: extremely gentle slopes (< 10°), gentle slopes (10–20°), moderately steep slopes (20–30°), steep slopes (30–40°), very steep slopes (40–50°), and cliffs (> 50°). The slope distribution map of the study region is presented in Fig. 5.

Lithology

Lithology plays a critical role in determining landslide susceptibility 50. The lithological data used in this study were obtained from the 1:50,000-scale geological map of Souk Ahras province. This map revealed a wide variety of lithological units within the study area. As illustrated in Fig. 6, these units were classified into 21 distinct groups. Landslides were observed to occur predominantly in zones characterized by clay and marl formations, particularly along the railway corridor in the eastern and central parts of the study region.

Distance from faults

In geology, fault zones are areas where rocks and soils exhibit mechanical weakness, making them highly susceptible to landslides. Tectonic discontinuities reduce the overall strength of these materials, thereby increasing instability7,47,89. In this study, faults were classified into five groups to generate a fault distance map at 500 m intervals using the Euclidean distance method (Fig. 7). The classification was based on the geological map of Souk Ahras76. Five classes of fault distances were identified. The first class (< 50 m) represents the most affected zones, where faults are closely spaced, with separations of less than 50 m. The second class (50–200 m) includes areas with a high density of faults, while the third class (200–500 m) contains a moderate number of faults. The fourth class (500–1000 m) indicates sparse faulting, whereas the last class (> 1000 m) represents areas with no mapped faults (Fig. 7).

Distance from rivers

It is essential to consider drainage density and proximity to rivers when assessing slope stability and erosion processes 4,23,24. Areas with high drainage density often experience greater surface runoff, which increases pore-water pressure and reduces the shear strength of slope materials. This process makes slopes more susceptible to failure and instability 1,6. In this study, ArcGIS was used to extract drainage networks from the ALOS PALSAR DEM. The procedures included sink filling, flow direction and accumulation analysis, and stream network delineation, resulting in the generation of a detailed drainage system. Drainage density was then calculated by dividing the total length of the river network by the size of the study area 23,24. The study area was classified into five distance zones based on proximity to rivers. The very high susceptibility class included areas located within 50 m of rivers, where slope instability is most pronounced. The high-density class covered areas between 50 and 150 m, indicating relatively close proximity to rivers. Moderate-density zones extended between 150 and 250 m, while low-density areas ranged from 250 to 500 m. Very low-density areas were located more than 1000 m from rivers. The Drainage Density Map (Fig. 8) illustrates the influence of hydrological processes on erosion and slope stability across the study area.

Elevation

Elevation has a significant effect on slope instability, even though it does not directly cause it. This is because weathering, erosion, and moisture accumulation vary with altitude 28,29,30. In this study, we used ALOS PALSAR DEM data with a spatial resolution of 12.5 × 12.5 m to generate elevation maps for the investigation area. The elevation was divided into five groups based on the geomorphological and lithological characteristics of the terrain. The first group (200–500 m) represents lower altitudes with relatively stable geological features. The second group (500–700 m) corresponds to moderate elevations where erosion processes are more likely to occur. The third group (700–1000 m) includes steeper terrains where weathering effects become more evident. The fourth group (1000–1200 m) reflects higher altitudes where slope dynamics are more pronounced. Finally, the fifth group (1200–1500 m) combines steep slopes with a high potential for weathering, which significantly affects slope stability. In the research region, Fig. 9 shows the distribution of the different elevation classes.

Rainfall

The study area receives between 400 and 800 mm of rainfall annually, depending on the specific location. Variations in rainfall influence the soil moisture content, which directly affects the likelihood of landslides. In the northern part of the region, higher rainfall contributes to increased soil instability on slopes, while in the southern part, lower precipitation reduces the risk of landslides (Fig. 10). This spatial variability is crucial for accurately assessing landslide susceptibility, as it allows for a more precise identification of potential hazard zones 34,35.

Normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI)

The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) in the study region, derived from Sentinel satellite imagery, ranges from 0.40 to 0.86 (Fig. 11). This indicates considerable variation in vegetation cover 37,38. Negative values correspond to bare surfaces, whereas higher positive values represent dense and healthy vegetation. This variation is critical for assessing landslide susceptibility, as areas with dense vegetation help stabilize slopes, while sparsely vegetated areas are more prone to failure and sliding 43.

Land use and land cover (LULC)

Changes in land use and land cover (LULC) are driven by human activities, leading to the conversion of agricultural and forested areas into urban environments 44,45. In this study, supervised classification of Landsat 8 OLI imagery was performed using ArcGIS 10.8 and ENVI 5.0 software to generate the LULC map. The final classification identified six categories: water bodies, built-up areas, forest, agricultural land, low vegetation, and bare ground. These categories are critical for evaluating landslide susceptibility, as land cover strongly influences slope stability. The LULC distribution in the study area is shown in Fig. 1239,40.

Distance from roads

Distance to roadways is one of the main human-made variables that cause landslides 16,17,47,77,78. In fact, we saw that some landslides caused by road-building activities were found during the fieldwork. For this study, we constructed six zones with a distance of 300 m between them (Fig. 13).

Validation landslide susceptibility mapping

We used the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and the Area Under the Curve (AUC) method to evaluate the accuracy of the Frequency Ratio (FR) and Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) models in predicting landslide susceptibility. For validation, 100 past landslide events were reserved, representing 40% of the total recorded incidents. Using GIS tools, both models generated susceptibility maps that classified landslide-prone areas into zones ranging from very low to very high risk, depending on their spatial distribution 79,80,90. The ROC curve was constructed by plotting the false positive rate against the true positive rate. The true positive rate represents the proportion of landslide sites correctly predicted to fall within moderate to high susceptibility zones 63,64. The false positive rate represents the proportion of non-landslide sites incorrectly classified as high risk. The AUC was then calculated to quantify the overall predictive performance of each model. Values close to 1 indicate stronger predictive capability 42. This evaluation approach provided a reliable assessment of the models’ performance, allowing clear differentiation between landslide-prone and stable areas. Similar methodologies have been highlighted in previous studies 46,47,49. The results confirmed that the susceptibility maps are practical and can serve as valuable tools for landslide risk preparedness and hazard management.

Results

Landslide susceptibility mapping using FR model

The Frequency Ratio (FR) model quantitatively evaluates the relationship between conditioning factors and observed landslide occurrences by comparing the areal proportion of landslides in a given class with the proportion of that class within the entire study area. An FR value greater than 1 indicates a positive correlation between the factor class and landslide occurrence, whereas values less than 1 indicate a negative correlation. Lithological units display distinct contrasts in susceptibility. Alluvium (FR = 0.52), marlstone (FR = 0.70), and conglomerate (FR = 1.04) show limited association with landslides, while sandstone (FR = 1.28), limestone (FR = 1.92), and gypsum (FR = 3.67) exhibit high susceptibility. The gypsum and limestone units, in particular, correspond to 23.64% (53 landslides) and 18.24% (27 landslides) of the total inventory, reflecting their structural weakness and dense fracturing. By contrast, marlstone, concentrated in the southern sector of the study area, records the lowest FR value (0.52).

Topographic slope is also a critical parameter. The lowest slope class (< 10°) covers 71.37% (3012.79 km2) of the study area and has an FR of 0.72, indicating low susceptibility despite some recorded landslides, owing to the generally stable plateau conditions. The 20°-30° interval, although covering only 4.61% (194.81 km2) of the terrain, records the highest FR value (1.80), confirming slope gradient as a key driver of instability. Rainfall exerts a marked influence, with FR values increasing alongside precipitation: 0.22 (300–400 mm), 0.22 (400–500 mm), 0.47 (500–600 mm), 2.07 (600–700 mm), and 2.56 (700–800 mm). The spatial distribution of training landslides shows that 74.32% (110 out of 148) occurred on northeast- and centrally-facing slopes, where concentrated rainfall and drainage enhance instability. Hydrological and structural factors also reveal consistent statistical patterns. Proximity to rivers shows the highest susceptibility within 0–50 m (FR = 0.56) and 50–150 m (FR = 0.32), consistent with erosional undercutting and slope destabilization. Similarly, the distance-from-faults parameter yields increasing FR values with closer proximity, peaking at 1.26 in the 50–200 m class, which represents 30.41% of the study area and reflects weak slope materials coupled with dense lineament networks. Land use/land cover (LULC) classes further confirm anthropogenic influence. Built-up areas (FR = 2.75), forests (FR = 1.82), and agricultural zones (FR = 1.23) exhibit higher susceptibility, whereas bare terrain (FR = 0.47) and water bodies (FR = 0.54) correspond to stable conditions. Vegetation root reinforcement and water-saturated environments contribute to stability in these latter categories. The Landslide Susceptibility Index (LSI) was derived using Eq. (2) in the ArcGIS 10.8 raster calculator, producing values between 2.26 and 24.31. Following the classification scheme of Hadji et al. (2013) and Mehadadi et al. (2018), five susceptibility zones were identified: very low (23.42%, 988.21 km2), low (22.72%, 958.92 km2), moderate (22.30%, 941.27 km2), high (26.03%, 1098.56 km2), and very high (5.50%, 232.26 km2). In total, 46.14% (1947.13 km2) of the study area falls within very low or low susceptibility zones, concentrated mainly in the southern, southwestern, and southeastern regions. Conversely, 31.53% (1330.82 km2) lies within high to very high zones, predominantly along the Medjarda River, NE–SW lineament corridors, and gypsum–limestone–sandstone outcrops, where geomorphological and geological conditions combine to amplify landslide risk (Table 4).

Landslide susceptibility mapping using AHP model

The Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) was applied using the same conditioning factors as those employed in the FR model. A pairwise comparison matrix was constructed, and weights were derived through the eigenvalue method (65). The resulting factor weights (FW) were as follows: slope (0.30), lithology (0.22), distance from faults (0.16), distance from rivers (0.11), elevation (0.08), rainfall (0.06), NDVI (0.03), LULC (0.02), and distance from roads (0.02) (Table 5). The consistency of the matrix was verified by calculating the maximum eigenvalue (λmax), the consistency index (CI), and the consistency ratio (CR), confirming that the derived weights were logically consistent. Slope was identified as the most influential parameter. Areas with gradients exceeding 50° were classified as “very high” susceptibility due to the strong gravitational driving forces, whereas slopes below 10° were classified as “very low” (Das et al., 2023). Lithology ranked second in importance, with weak formations such as limestone and sandstone assigned “very high” susceptibility, while more stable formations like alluvium and marlstone were categorized as “very low.” Distance from faults also contributed significantly, as zones within 50 m of lineaments were rated “very high” owing to structural weaknesses (31, 32). Hydrological and environmental factors also played important roles. Proximity to rivers (< 50 m) was associated with “very high” susceptibility due to saturation and toe erosion, while areas located > 500 m away were rated “very low.” Elevations between 1200–1500 m were classified as “very high” because of enhanced gravitational stress and erosion, whereas low elevations (200–500 m were considered “very low.” Rainfall intensities between 700–800 mm corresponded to “very high” susceptibility due to soil saturation (Table 5). With respect to NDVI, sparsely vegetated areas were identified as “very low,” while densely vegetated zones provided greater stability. LULC analysis indicated that bare land increased instability (“very high”), whereas forests and agricultural land reduced susceptibility. Road proximity also exerted an influence, with areas < 50 m rated “very high” due to cut-and-fill operations, while those > 500 m were classified as “very low” 41,42,85. The Landslide Susceptibility Index (LSI) was computed using Eq. (3) in the ArcGIS raster calculator (Fig. 14). The results classified the study area into five zones: very low (1850.1 km2, 43.84%), low (1270.02 km2, 30.10%), moderate (521.2 km2, 12.35%), high (382.5 km2, 9.06%), and very high (195.4 km2, 4.63%) (Table 6). Approximately 73.94% (3120.12 km2) of the area falls within the very low and low susceptibility zones, concentrated in the southern, southwestern, and southeastern regions. In contrast, 13.69% (577.9 km2) lies in the high and very high zones, mainly distributed in the northern, northwestern, and northeastern sectors. These highly susceptible areas are associated with steep slopes, dense fault networks, and lithological units dominated by gypsum, limestone, and sandstone (Fig. 15).

Landslide susceptibility model validation

The ROC curve analysis was applied to evaluate the predictive performance of the AHP and FR models in forecasting landslide susceptibility. The FR model achieved a higher AUC value of 0.770, indicating superior predictive capability (Fig. 16). In comparison, the AHP model produced an AUC value of 0.687, demonstrating moderate performance in identifying areas prone to landslides while minimizing false positives (Fig. 17). The SDM (Spatial Data Modeler) extension in ArcGIS was used to generate the ROC curves. This tool compares the predicted susceptibility ratings (landslide susceptibility index) with the actual landslide occurrences to assess model accuracy 63,64. The analysis employed sensitivity (true positive rate) and 1-specificity (false positive rate) across various thresholds to construct the ROC curves. Results confirm that the FR model, with its higher AUC value, provides more reliable predictions of landslide susceptibility compared to the AHP model. This finding suggests that the FR model offers a more effective framework for assessing landslide likelihood in the studied region 46,47,48,49.

Discussion

Landslide susceptibility zones

The study area was classified into five degrees of landslide susceptibility: very low, low, moderate, high, and very high. The FR model identified 232.26 km2 (5.50% of the area) as a very high-risk zone. These locations are primarily characterized by steep slopes, weak lithological formations, and dense lineament networks. The AHP model also delineated very high-risk areas, but they covered only 195.4 km2 (4.63% of the total area), which is smaller than that identified by the FR model. These zones are of critical importance as they represent areas with the greatest likelihood of landslide occurrence. They are defined by steep topography, unstable rock units, numerous faults, complex drainage systems, and elevated terrain, all of which collectively increase the probability of slope failure.

Influence of contributing factors

Both the FR and AHP models identify critical factors influencing landslide susceptibility, however, they differ in methodology and interpretability. The FR model is purely data-driven, quantifying the statistical relationships between past landslide occurrences and conditioning factors, whereas the AHP model incorporates expert judgment by assigning relative weights to each factor 50,51,52,53,54,55. In both models, slope emerged as the dominant parameter. Steep slopes (20–30°) recorded high FR scores (1.80) and the highest AHP weight (0.30), reflecting the strong influence of gravitational stress. Lithology, particularly weak formations such as gypsum, was also critical, with the highest FR score (3.67) and a substantial AHP weight (0.22). Proximity to faults increased susceptibility at < 200 m (FR scores 1.12–1.26) and corresponded to an AHP weight of 0.16, highlighting the structural control exerted by tectonic discontinuities. Hydrological influences were evident through high FR scores (1.32) and an AHP weight of 0.11 for areas within 50 m of rivers, where erosion and saturation processes destabilize slopes. Elevation (200–500 m) also exhibited significant vulnerability (FR = 1.40, AHP weight = 0.08). Overall, the FR model provides an objective statistical evaluation of factor landslide relationships, although it may be constrained by data sparsity or uneven inventory distribution. By contrast, the AHP model offers greater flexibility through expert-driven weighting, which enhances factor prioritization and supports decision-making in high-risk regions. However, the potential influence of expert bias requires careful validation. Beyond these models, landslide susceptibility is increasingly shaped by anthropogenic drivers (road construction, deforestation, and urban expansion), climatic variability (intensified rainfall events linked to climate change), and interactive effects among factors (deforestation combined with heavy rainfall on steep slopes near fault zones). Future research should incorporate these dynamic influences to improve predictive accuracy and ensure that susceptibility maps more accurately reflect real world hazard conditions.

Validation of models

Validation of the susceptibility models was conducted using the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and the associated Area Under the Curve (AUC) metric, which are widely applied to evaluate classification performance. The AUC value represents the probability that the model will correctly differentiate between landslide and non-landslide locations, with values closer to 1.0 indicating stronger predictive capability. The AHP model achieved an AUC of 0.687, reflecting a moderate ability to discriminate landslide-prone areas from stable zones. By contrast, the FR model yielded a higher AUC of 0.770, demonstrating superior predictive performance. This improvement stems from the FR model’s statistical formulation, which directly measures the relative frequency of landslide occurrence within each factor class, thereby capturing nonlinear relationships between conditioning variables. In comparison, the AHP model relies on expert-driven pairwise comparisons and assumes independence among factors. Although this structured weighting approach is valuable in data-scarce contexts, it may not fully account for higher-order interactions among variables, which could explain its comparatively lower predictive accuracy in this study 44,45. Overall, the ROC–AUC validation confirms that the FR model outperforms AHP for susceptibility mapping in Souk Ahras, offering a more reliable tool for hazard assessment and land-use planning in regions where understanding the combined influence of environmental and geological factors is critical43.

Comparative discussion with previous studies

The findings of this study are consistent with previous research conducted in Algeria’s highlands and in comparable mountainous regions worldwide. As reported in earlier studies 3,16,81, slope gradient, lithology, and proximity to faults were identified as the most influential conditioning factors 87. The high AUC values obtained for both the FR and AHP models confirm their reliability in data-scarce contexts, supporting previous works that emphasized their effectiveness for susceptibility mapping 30,91. In particular, the FR model demonstrated stronger predictive accuracy in this case study, echoing the findings of 16,82 and 17, whereas the AHP model provided a more transparent framework for expert driven weighting and factor prioritization. Classical approaches were selected over advanced AI/ML techniques because of the limited availability of comprehensive landslide inventories and socioeconomic data in the study area. Statistical models such as FR and semi-quantitative approaches like AHP remain more robust under such constraints, offering interpretable outcomes and ease of application for planners and decision-makers. Nevertheless, these methods also present limitations: FR depends heavily on historical landslide records and may underperform where inventories are incomplete, while AHP is subject to expert bias in weight assignment. Both approaches may oversimplify the complex interactions among geomorphological, climatic, and anthropogenic drivers 92,93. This study also aligns with research emphasizing the influence of human activities such as road construction and land-use change on slope instability 3,47,83,84. Climatic variability, particularly extreme rainfall events linked to climate change, further intensifies hazard levels when combined with weak lithologies or deforested slopes. These interactions highlight the need for adaptive, multidisciplinary models that integrate geophysical, climatic, and socioeconomic dimensions. From a practical perspective, the susceptibility maps generated in this study provide a reliable foundation for regional land-use planning and disaster risk reduction. They can support authorities in prioritizing monitoring and mitigation efforts in high-risk zones. However, their application should remain cautious given the inherent simplifications of classical models. Future research should focus on integrating advanced machine learning methods (Random Forest, SVM, and deep learning) to improve predictive accuracy, incorporate temporal forecasting of rainfall-triggered events, and embed socioeconomic and infrastructural variables to better capture anthropogenic influences. Extending these frameworks to other mountainous regions would further assess the transferability and scalability of the models.

Conclusions

This study proposes a comprehensive approach to mapping landslide susceptibility in Souk Ahras, Algeria. The methodology integrates the Frequency Ratio (FR) and Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) models with GIS and remote sensing technologies. The analysis focuses on critical criteria such as slope, lithology, and proximity to faults, which strongly influence landslide occurrence. Given the limited prior research in this area, the results provide essential insights into landslide hazards, an increasingly important field of study. Identifying highly susceptible zones offers local authorities and decision-makers valuable guidance for land-use planning, infrastructure development, and disaster management. Regular monitoring and proactive management in these regions can significantly mitigate the impacts of landslides on populations and local economies. The findings also led to targeted recommendations for the province of Souk Ahras. Routine monitoring and preventive measures should be concentrated in high-risk areas characterized by steep slopes, fragile lithological formations, and dense fault networks. Local authorities are encouraged to adopt soil stabilization techniques, implement reforestation programs, and reinforce vulnerable slopes to enhance overall stability. Furthermore, community-based educational initiatives that raise awareness about landslide risks, early warning indicators, and evacuation procedures can substantially improve public safety, particularly in zones with high susceptibility. Despite the robustness of the results, certaine limitation are acknowledged. The dataset contained a limited number of documented landslides, which complicated the validation process. Expanding the landslide inventory over time would improve model accuracy and predictive capability. Moreover, the AHP method depends on expert judgment, which introduces a degree of subjectivity. Incorporating automated weighting techniques could reduce this limitation. Future research in Souk Ahras should prioritize the development of real-time monitoring systems that combine satellite observations with ground-based sensors to track slope stability. Additionally, investigating the socioeconomic consequences of landslides on local populations could help design more effective, community-centered mitigation strategies that directly benefit residents in affected areas.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from [Noah Rebouh]. Still, restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study and are not publicly available. However, data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of [Noah Rebouh].

References

Hadji, R., Limani, Y., Baghem, M. & Demdoum, A. Geologic, topographic and climatic controls in landslide hazard assessment using GIS modeling: a case study of Souk Ahras region. NE Algeria. Quaternary International 302, 224–237 (2013).

Rebouh N, Khiari A . La Cinématique et l’organisation des structures géologiques dans le Constantinois.(2022)

Najar, I. A. et al. Site-specific ground response analysis using the geotechnical dataset in moderate seismicity region. Int. J. Mech. 16(1), 37–45 (2022).

Rebouh, N., Oudni, A., Khiari, A., & Özgür, N. . Mapping of Landslide Susceptibility Using Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) in the Ain Smara and its Surrounding Areas, Algeria (Northeastern of Algeria). Studies in Science of Science| ISSN, 1003–2053.(2024a)

Fatah, K. K., Mustafa, Y. T. & Hassan, I. O. Geoinformatics-based frequency ratio, analytic hierarchy process and hybrid models for landslide susceptibility zonation in Kurdistan Region, Northern Iraq. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 26(3), 6977–7014 (2024).

Mahadadi, F. & Boumezbeur, A. Landslide susceptibility mapping using logistic regression and frequency ratio approaches, case study from Souk Ahras region, NE Algeria. Italian J. Eng. Geol. Environ. 1, 45–53 (2020).

Rebouh, N., Oudni, A., Khiari, A. & Benabbas, C. Özgür N Hydrothermal alteration mapping and structural features in the Ain Smara basin, Constantine (Northeastern Algeria): contribution of Landsat OLI8 data. AJGS 14, 1–19 (2021).

Hoa, P. V., Tuan, N. Q., Hong, P. V., Thao, G. T. P. & Binh, N. A. GIS-based modeling of landslide susceptibility zonation by integrating the frequency ratio and objective–subjective weighting approach: a case study in a tropical monsoon climate region. Front. Environ. Sci. 11, 1175567 (2023).

Barman, J., & Das, J. Assessing classification system for landslide susceptibility using frequency ratio, analytical hierarchical process and geospatial technology mapping in Aizawl district, NE India. Advances in Space Research. (2024).

Sahin EK Assessing the predictive capability of ensemble tree methods for landslide susceptibility mapping using XGBoost, gradient boosting machine, and random forest. SN Applied Sciences 2(7): 1308. (2020)

Bahrami, Y., Hassani, H. & Maghsoudi, A. Landslide susceptibility mapping using AHP and fuzzy methods in the Gilan province. Iran. Geo. J. 86(4), 1797–1816 (2021).

Najar, I. A. et al. Advancing soil-structure interaction (SSI): A comprehensive review of current practices, challenges, and future directions. J. Infrastruct. Preserv. Resilience 6(1), 5 (2025).

Azarafza, M., Azarafza, M., Akgün, H., Atkinson, P. M. & Derakhshani, R. Deep learning-based landslide susceptibility mapping. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 24112 (2021).

Nanehkaran, Y. A., Mao, Y., Azarafza, M. & Kockar, M. K. Zhu HH Fuzzy-based multiple decision method for landslide susceptibility and hazard assessment: A case study of Tabriz. Iran. Geomech. Eng. 24(5), 407–418 (2021).

Nikoobakht, S., Azarafza, M. & Akgün, H. Derakhshani R landslide susceptibility assessment by using convolutional neural network. Appl. Sci. 12(12), 5992 (2022).

Leonardi, G., Palamara, R., Manti, F. & Tufano, A. GIS-Multicriteria Analysis Using AHP to Evaluate the Landslide Risk in Road Lifelines. Appl. Sci. 12(9), 4707 (2022).

Van Duong, B., Fomenko, I. K., Nhu, H. V., Nguyen, P. H., Sirotkina, O. N., Nguyen, K. T., ... & Pham, T. Landslide hazard assessment for the Batxat area of Vietnam using GIS-based spatial prediction models. Journal of Mining and Earth Sciences Vol, 65(6), 70–81. (2024).

Bragagnolo L, da Silva RV, Grzybowski JMV . Landslide susceptibility mapping with r. landslide: A free open-source GIS-integrated tool based on artificial neural networks. Environmental Modelling & Software 123: 104565.(2020)

Bhagya, S. B. et al. Landslide susceptibility assessment of a part of the Western Ghats (India) employing the AHP and F-AHP models and comparison with existing susceptibility maps. Land 12(2), 468 (2023).

Azarafza, M., Ghazifard, A., Akgün, H. & Asghari-Kaljahi, E. Landslide susceptibility assessment of South Pars Special Zone, southwest Iran. Environmental Earth Sciences 77(24), 805 (2018).

Froude MJ, Petley DN . Global fatal landslide occurrence from (2004 to 2016) Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 18(8): 2161–2181.2018

Rebouh, N., Tout, F., Dinar, H., Benzid, Y. & Zouak, Z. Integrating Multi-Source Geospatial Data and AHP for Flood Susceptibility Mapping in Ain Smara, Constantine, Algeria. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 6(2), 245–264 (2024).

Khalil, U. et al. Comparative analysis of machine learning and multi-criteria decision making techniques for landslide susceptibility mapping of Muzaffarabad district. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 1–19 (2022).

Alamrew, B. T., Kassawmar, T., Mengstie, L. & Jothimani, M. Combined GIS, FR and AHP approaches to landslide susceptibility and risk zonation in the Baso Liben district. Northwestern Ethiopia. Quaternary Science Advances 16, 100250 (2024).

Taib, H., Benabbas, C., Khiari, A., Hadji, R. & Haythem, D. Geomatics-based assessment of the Neotectonic landscape evolution along the Tebessa-Morsott-Youkous collapsed basin, Algeria. Geomatics, Landmanagement and Landscape 3, 131–146 (2022).

Ali, Z. et al. Hybrid Fuzzy AHP and Frequency Ratio Methods for Assessing Flood Susceptibility in Bayech Basin. Southwestern Tunisia. Sustainability 15(21), 15422 (2023).

Tout, F., Rebouh, N., Dinar, H., Benzid, Y. & Zouak, Z. The Contribution of Roads to Forest Fire Protection in Tamza Municipality, Northeast Algeria. Int. J. Disaster Risk Manag. 6(2), 39–50 (2024).

Pragya, Kumar, M., Tiwari, A., Majid, S. I., Bhadwal, S., Sahu, N., ... & Avtar, R. Integrated spatial analysis of forest fire susceptibility in the Indian western himalayas (IWH) using remote sensing and GIS-based fuzzy AHP approach. Remote Sensing, 15(19), 4701.(2023).

Apu, S. I., Sharmili, N., Gazi, M. Y., Mia, M. B., & Sifa, S. F. Remote Sensing and GIS-Based Landslide Susceptibility Mapping in a Hilly District of Bangladesh: A Comparison of Different Geospatial Models. Journal of the Indian Society of Remote Sensing, 1–18.(2024).

Prapanchan, V. N., Indhiya Selvan, V. N., Vignesh, K. S., & Kumar, E. Geospatial multi-criteria assessment with fuzzy-ahp for landslide susceptibility mapping in Almora District, India. In Landslides in the Himalayan Region: Risk Assessment and Mitigation Strategy for Sustainable Management (pp. 335–366). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.(2024).

Chelariu, O. E., Minea, I., & Iațu, C. Geo-hazards assessment and land suitability estimation for spatial planning using multi-criteria analysis. Heliyon, 9(7).(2023).

Elkhrachi, I. et al. Landslide susceptibility mapping and management in Western Serbia: an analysis of ANFIS-and SVM-based hybrid models. Front. Environ. Sci. 11, 1218954 (2023).

Tout, F., Rebouh, N., Dinar, H., Zouak, Z. & Benzid, Y. The issue of using annual rainfall maps in multi-criteria analysis to identify flood-prone areas. Geomatics, Landmanagement and Landscape 4, 267–278 (2024).

Cantarino, I., Carrion, M. A., Martínez-Ibáñez, V. & Gielen, E. Improving landslide susceptibility assessment through frequency ratio and classification methods—case study of valencia region (Spain). Appl. Sci. 13(8), 5146 (2023).

Okoli, J. et al. High-Resolution Lidar-Derived DEM for Landslide Susceptibility Assessment Using AHP and Fuzzy Logic in Serdang. Malaysia. Geosciences 13(2), 34 (2023).

Mao, Y., Zhu, L., Chen, J., & Nanehkaran, Y. A.Adaptive modeling of landslide susceptibility using Analytical Hierarchy Process and Multi-Objective Decision Optimization. Advances in Space Research. (2024).

Mandal, B., Mondal, S. & Mandal, S. GIS-based landslide susceptibility zonation (LSZ) mapping of Darjeeling Himalaya, India using weights of evidence (WoE) model. Arab. J. Geosci. 16(7), 421 (2023).

Khatun, M. et al. Landslide susceptibility mapping using weighted-overlay approach in Rangamati Bangladesh. Earth Syst. Environ. 7(1), 223–235 (2023).

Huang, F., Mao, D., Jiang, S. H., Zhou, C., Fan, X., Zeng, Z., ... & Li, Y. . Uncertainties in landslide susceptibility prediction modeling: a review on the incompleteness of landslide inventory and its influence rules. Geoscience Frontiers, 101886.(2024)

Tadesse, L., Uncha, A. & Toma, T. Landslide vulnerability mapping using multi-criteria decision-making approaches: in Gacho Babba District, Gamo Highlands Southern Ethiopia. Discover Applied Sciences 6(2), 31 (2024).

Panchal, S. & Shrivastava, A. K. A comparative study of frequency ratio, Shannon’s entropy and analytic hierarchy process (AHP) models for landslide susceptibility assessment. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 10(9), 603 (2021).

Gulbet, E. & Getahun, B. Landslide susceptibility mapping using frequency ratio and analytical hierarchy process method in Awabel Woreda Ethiopia. Quarter. Sci. Adv. 16, 100246 (2024).

Zhou, W., Yan, Z. & Zhang, L. A comparative study of 11 non-linear regression models highlighting autoencoder, DBN, and SVR, enhanced by SHAP importance analysis in soybean branching prediction. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 5905 (2024).

Ali, N. et al. Integrating Machine Learning Ensembles for Landslide Susceptibility Mapping in Northern Pakistan. Remote Sensing 16(6), 988 (2024).

Singha, C., Rana, V. K., Pham, Q. B., Nguyen, D. C. & Łupikasza, E. Integrating machine learning and geospatial data analysis for comprehensive flood hazard assessment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31(35), 48497–48522 (2024).

Chen, W., Zhang, S., Li, R. & Shahabi, H. Performance evaluation of the GIS-based data mining techniques of best-first decision tree, random forest, and naïve Bayes tree for landslide susceptibility modeling. Sci. Total Environ. 644, 1006–1018 (2018).

El Jazouli, A. & Barakat, A. Khellouk R GIS-multicriteria evaluation using AHP for landslide susceptibility mapping in Oum Er Rbia high basin (Morocco). Geoenviron. Disasters 6(1), 1–12 (2019).

Beigh, I. H. & Bukhari, S. K. Assessment of GIS-based landslide susceptibility using bivariate and multivariate approach–a case study of Kashmir Himalayas. J Rock Mech Tunn Technol (JRMTT) 30(1), 39–56 (2024).

Zêzere, J. L., Pereira, S., Melo, R. & Oliveira, S. C. Garcia RA Mapping landslide susceptibility using data-driven methods. Sci. Total Environ. 589, 250–267 (2017).

Althuwaynee OF & B Pradhan . Semi-quantitative landslide risk assessment using GIS-based exposure analysis in Kuala Lumpur City. Geomatics Natural Hazards & Risk8(2): 1–27.(2016)

Swetha, T. V. & Gopinath, G. Landslides susceptibility assessment by analytical network process: a case study for Kuttiyadi river basin (Western Ghats, southern India). SN Applied Sciences 2(11), 1776 (2020).

Sur, U., Singh, P. & Meena, S. R. Landslide susceptibility assessment in a lesser Himalayan road corridor (India) applying fuzzy AHP technique and earth-observation data. Geomat. Nat. Haz. Risk 11(1), 2176–2209 (2020).

Jam, A. S., Mosaffaie, J., Sarfaraz, F., Shadfar, S. & Akhtari, R. GIS-based landslide susceptibility mapping using hybrid MCDM models. Nat. Hazards 108(1), 1025–1046 (2021).

Roy, D., Das, S. & Mitra, R. An application of geospatial-based multi-criteria decision making technique to identify landslide susceptibility zones in the Ragnu Khola River Basin of Darjeeling Himalayan region. India. Applied Geomatics 14(4), 731–749 (2022).

Wang, Y., Kang, L., & Wang, J. Landslide risk assessment combining kernel extreme learning machine and information value modeling-A case study of Jiaxian Country of loess plateau, China. Heliyon, 10(17). (2024).

Rebouh, N., Tout, F., Dinar, H., Benzid, Y., Oudni, A., Khiari, A., & Özgür, N. Identification of potential groundwater zones using the analytical hierarchical process technique: Case study of the region of Constantine–Northeastern Algeria Identification of potential groundwater zones using the analytical hierarchical process technique: Case study of the region of Constantine–Northeastern Algeria. Geomatics, Landmanagement and Landscape. (2025).

Dinar, H., Rebouh, N., Tout, F., Batouche, T. & Mansouri, Z. Development of an erosion map using geographic information systems (GIS) and based on the hierarchical analytic process (AHP) case study of Boumerdes-Zemmouri, eastern of Algiers. Analele Universităţii din Oradea, Seria Geografie 35(2), 97–110 (2025).

Oudni, A., Aouissi, R., Welton, R. K., Mazouz, E. H., Rebouh, N., & Khiari, A. First insight on macroinvertebrates of Chebket Es Sellaoua (NE Algeria): Some significant ammonites from the lower Mantelliceras mantelli Zone (lower Cenomanian). In Annales de Paléontologie (Vol. 111, No. 2, p. 102870). Elsevier Masson. (2025).

Benzid, Y., Rebouh, N., Benzagouta, Y., Seghiri, M., & Gattuso, C. The impact of environmental and climatic factors on archaeological sites: case study of the roman ruins of Lambaesis (north east Algeria). In Diagnosis for the Conservation and Valorization of Cultural Heritage XV CONVEGNO INTERNAZIONALE (pp. 304–313). Edizioni del Delfino.(2024).

Pradhan, B. Remote Sensing and GIS-based landslide hazard analysis and cross validation using multivariate logistic regression model on three test areas in Malaysia. Adv. Space Res. 45, 1244–1256 (2010).

Cengiz LD, Ercanoglu M .A novel data-driven approach to pairwise comparisons in AHP using fuzzy relations and matrices for landslide susceptibility assessments. Environmental Earth Sciences 81(7): 222.(2022)

Das, S., Sarkar, S. & Kanungo, D. P. GIS-based landslide susceptibility zonation mapping using the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) method in parts of Kalimpong Region of Darjeeling Himalaya. Environ. Monit. Assess. 194(3), 234 (2022).

Mengstie, L., Nebere, A., Jothimani, M. & Taye, B. Landslide susceptibility assessment in Addi Arkay, Ethiopia using GIS, remote sensing, and AHP. Quaternary Science Advances 15, 100217 (2024).

Mohammednur, R. S., Deribew, K. T., Moisa, M. B., & Gemeda, D. O. Landslide susceptibility zonation mapping using geospatial technologies and multi criteria evaluation techniques in the upper Didessa sub-basin, Southwest Ethiopia. Geology, Ecology, and Landscapes, 1–15.(2024).

Saaty, TL. A scaling method for priorities in hierarchical structures.Journal of Mathematical Psychology15: 234–281.(1980)

Arekhi, S. & Nazari, R. Zoning erosion intensity and sediment yield using MPSIAC in GIS (Case study: Ilam catchment). Iranian Water Researches Journal 2(2), 77–81 (2008).

Afsari, S., Yazdi, M., Bahrami, A. & Carnevale, G. A new deep-sea hatchetfish (Teleostei: Stomiiformes: Sternoptychidae) from the Eocene of Ilam, Zagros Basin. Iran. Bollettino della Società Paleontologica Italiana 53(1), 28 (2014).

Rostami, Z. A., Al-Modaresi, S. A., Fathizad, H. & Faramarzi, M. Landslide susceptibility mapping by using fuzzy logic: a case study of Cham-gardalan catchment, Ilam. Iran. Arabian Journal of Geosciences 9(17), 1–11 (2016).

Ahmadi, M., Mokhtari, D., Khodadadi, M. & Shahabi, H. Geodiversity evaluation and geoconservation using grid analysis: case study, north of Ilam Province. Applied Geomatics 13(4), 537–553 (2021).

Ahmadi-Molaverdi, M., Jabbari, I. & Fathnia, A. Geomorphological and Spatial Analysis of Dust sources in Ilam Province. Iran. Sedimentary Geology 436, 106168 (2022).

Sweets JF . Hold that pendulum! Redefining Fascism, collaborationism and resistance in France French Hist Stud, 731–758.(1988)

Gorsevski PV, Gessler PE, Foltz RB, Elliot WJ . Spatial prediction of landslide hazard using logistic regression and ROC analysis. Transactions in GIS10: 395–415.(2006)

Fawcett T . An introduction to ROC analysis.Pattern Recognition Letters27: 861–874.(2006)

Nandi A, Shakoor A A GIS-based landslide susceptibility evaluation using bivariate and multivariate statistical analyses.Engineering Geology110: 11–20.(2010)

Saaty TL . A scaling method for priorities in hierarchical structures.Journal of Mathematical Psychology15:59–62 (1977)

Vila JM La chaîne alpine de l’Algérie orientale et des confins algéro-tunisiens. Thèse de Doctorat-es-sciences, Université Pierre et Marie curie. (1980)

Nourani V, Baghanam AH, Adamowski J, Kisi O . Applications of hybrid wavelet–artificial intelligence models in hydrology: A review.Journal of Hydrology514: 358–377.(2014).

Yilmaz I Comparison of landslide susceptibility mapping methodologies for Koyulhisar, Turkey: Conditional probability, logistic regression, artificial neural networks, and support vector machine.Environmental Earth Sciences 61: 821–836. (2010)

Hodasová, K. & Bednarik, M. Effect of using various weighting methods in a process of landslide susceptibility assessment. Nat. Hazards 105, 481–499 (2021).

Abdo, H. G. Assessment of landslide susceptibility zonation using frequency ratio and statistical index: a case study of Al-Fawar basin, Tartous, Syria. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 19(4), 2599–2618 (2022).

He, Y. Beighley RE GIS-based regional landslide susceptibility mapping: A case study in southern California. Earth Surf. Proc. Land. 33, 380–393 (2008).

Das, J., Saha, P., Mitra, R., Alam, A., & Kamruzzaman, M. GIS-based data-driven bivariate statistical models for landslide susceptibility prediction in Upper Tista Basin, India. Heliyon, 9(5).(2023).

Manchar N, BENABBAS C, Bouaicha F, Boufaa K . APPLICATION OF THE ANALYTICAL HIERARCHY PROCESS (AHP) FOR LANDSLIDE SUSCEPTIBILITY MAPPING IN THE EAST REGION OF CONSTANTINE, NE ALGERIA. Journal of Sciences & Technology, 4(2), 23–33.(2019)

Aslam, B. et al. Evaluation of different landslide susceptibility models for a local scale in the Chitral District. Northern Pakistan. Sensors 22(9), 3107 (2022).

Badavath, N., Sahoo, S. & Samal, R. Landslide susceptibility mapping for West-Jaintia Hills district. Meghalaya. Sādhanā 49(1), 52 (2024).

Benabbas C . Évolution Mio-Plio-Quaternaire des bassins continentaux de l’Algérie nord orientale: apport de la photogéologie et analyse morpho structurale. Grands travaux d’aménagement et mouvements de versant dans la région nord de Constantine (Algérie Nord–Orientale). Doctorat d’état, Constantine, 245p.(2006)

Bui, D. T., Lofman, O., Revhaug, I. & Dick, O. Landslide susceptibility analysis in the Hoa Binh province of Vietnam using statistical index and logistic regression. Nat. Hazards 59, 1413 (2011).

Chadi M . Géologie des monts d’Ain m’lila (Algérie orientale) (Doctoral dissertation, Université Henri Poincaré-Nancy 1).(1991)

Chen W, Panahi M, Pourghasemi HR . Performance evaluation of GISbased new ensemble data mining techniques of adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) with genetic algorithm (GA), differential evolution (DE), and particle swarm optimization (PSO) for landslide spatial modelling. CATENA157: 310–324.(2017)

Cirianni, F., Fonte, F. & Leonardi, G. Scopelliti F Analysis of lifelines transportation vulnerability. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012(53), 29–38 (2012).

Dai F & Lee C . Landslide characteristics and slope instability modeling using GIS, Lantau Island, Hong Kong.Geomorphology42: 213–228.(2002)

Hanley JA & McNeil BJ A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology 148:839–843.(1983)

Hong, H., Naghibi, S. A., Pourghasemi, H. R. & Pradhan, B. GIS-based landslide spatial modeling in Ganzhou City. China. Arabian Journal of Geosciences 9(2), 112 (2016).

Tout, F., Rebouh, N., Dinar, H., Benzid, Y. & Zouak, Z. Evaluating Algeria’s Approach to Major Risk Prevention and Disaster Response. J. Geography, Politics Soc. 15(1), 50–56 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors are highly grateful to the Centre de Recherche en Aménagement de Territoire (CRAT), Campus Zouaghi Slimane, Route de Ain el Bey, 25000 Constantine, Algérie, Laboratory of Natural Resources and Management of Sensitive Environments, and Faculty of Engineering, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, 94300, Kota Samarahan, Sarawak, Malaysia, for supporting the research. The authors extend their appreciation to the deanship of research and graduate studies at King Khalid University for funding the work through a large research project under grant number RGP2/32/46.

Funding

Not Applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Nouh Rebouh, Abdeldjalil Belkendil, Faicel Tout, Haythem Dinar, Yacine Benzid, Amer Zeghmar, Ahmed Alliouche, Mand ohamed Ikbal Farah wrote the manuscript, methodology, investigation, formal analysis. Imtiyaz Akbar Najar, and Nadeem A Khan writing-review and editing, supervision, validation. All the authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

The author declares that the manuscript has not been submitted to other journals.

Consent to participate

Not Applicable.

Consent for publication

All the authors agree to publish.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rebouh, N., Belkendil, A., Tout, F. et al. Landslide susceptibility assessment using hybrid geospatial, frequency ratio, and AHP models in Souk Ahras province, Northeastern of Algeria. Sci Rep 16, 2288 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32062-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32062-2