Abstract

In this study, we have performed first-principles calculations based on density functional theory (DFT), semi-classical Boltzmann theory, and full-potential linearized augmented plane wave (FP-LAPW) method with generalized gradient approximation (GGA) and Modified Becke–Johnson approach to investigate the structural, electrical, magnetic, optical, and thermoelectric properties of quaternary Heusler alloys CrZCoSn (Z=Zr, Hf). Our study reveals that both alloys are stable in the Type-1 (LiMgPdSn-type, space group F-43 m) structure, which is ferromagnetic in nature. The thermodynamic stability and ferromagnetic (FM) ground state of these HAs are confirmed by relative total energies and by calculated cohesive and formation energies, respectively. The existence of a band gap between the energy bands is elaborated with the hybridization of d-d orbitals among the constituent transition metals of HAs. The calculated magnetic moments of CrZrCoSn and CrHfCoSn alloys are 4.97 and 4.84 µB, respectively, while the specific heat (Cv) of these alloys is 92.1 and 93.36 J/mol− 1K, respectively. These alloys exhibit bulk modules of 117.43 and 118.73 GPa, respectively. Optical characteristics reveal that absorption of electromagnetic radiation takes place across the near UV and visible ranges of the spectrum. The static values of refractive index n(ω) for CrZrCoSn and CrHfCoSn HAs are 5.5 and 5.7, respectively. Results suggest that narrow bandgap (Eg), high ZT, and spin polarization make our HAs promising candidates for various spintronic, optoelectronic, and thermoelectric applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heusler alloys (HAs) are a diverse collection of intermetallic compounds known for their adjustable physicochemical properties and ordered crystal structures1. Depending on their crystal arrangement and chemical composition, they can be categorized as binary2, ternary3, or quaternary alloys (QHAs) and exhibit a large scale of functionalities, from semiconducting to ferromagnetic4, ferrimagnetic5, and antiferromagnetic behaviour6. Among these HAs, QHAs, along with the Y-type (LiMgPdSn-type) atomic configuration, have recently gained momentous research attention due to their high Curie temperature7, spin-dependent electronic behaviour8, flexible structure9, and compatibility with modern semiconductor technology10. These aspects make QHAs optimistic aspirants for magnetic tunnel junctions (MTJs)11, magneto-resistive random-access memory (MRAM) devices12, spin injectors13, and other spintronic applications where strong magnetic ordering and high spin polarization are required14. The idea of half-metallicity (HM)15, where one spin channel is semiconducting and the other displays a metallic behaviour, is particularly dominant for spintronic applications16. Many HAs displayed this behavior, and their electronic and magnetic characteristics can be tuned through doping or atomic substitution17, facilitating the design of materials with high magnetic anisotropy18, low damping constants19, and stable spin polarization20. Consequently, designing new HM Heusler compounds remains an active and vital domain of research for advancing next-generation energy and spintronic technologies21. First-principles simulations based on density functional theory (DFT)22 offer a methodical path to predict and optimize such multifunctional HAs in advance of their experimental synthesis23. DFT faithfully explains magnetic, mechanical, optical, and thermoelectric behavior through commanding material selection for technological applications24. Despite deep studies on Co, Mn, and Fe-based HAs, Cr-based QHAs remain considerably undiscovered, even though Cr provides strong magnetic exchange and the potential for tough HM25. Selectively, CrZCoSn (Z = Zr, Hf) HAs have gained very finite research attention. Hf and Zr-based HAs are known to furnish enhanced structural stability and tunability of electronic band gap (Eg), making them appropriate for the design of multifunctional compounds26,27. Nevertheless, no explicit computational work exists that investigates the optical, electrical, magnetic, and thermoelectric characteristics of these two Cr based QHAs simultaneously, leaving a clear research gap in the literature.

To address this gap, the present work presents a panoramic first-principles study of CrZCoSn (Z = Zr, Hf) HAs. We evaluate their thermodynamic stability, thermoelectric performance, magnetic ordering, and optical response. Our results show that both HAs are stable in the Type-I phase, with CrZrCoSn showcasing semiconducting nature and CrHfCoSn displaying HM.

Computational details

To investigate the structural, electrical, optical, and thermometric properties of our HAs, we have used the full-potential linearized augmented plane wave method (FP-LAPW)28 implemented in WIEN2k software29, which is one of the most precise, robust, and accurate tools within the framework of DFT. The accuracy of our calculated band structures has been improved by employing generalised gradient approximation (GGA)30 along with modified-Becke-Johnson (mBJ) correlational functions31. The mBJ potential is incorporated to achieve an enhanced description of the exchange potential, allowing more accurate prediction of the bandgap and spin-resolved electronic structure compared to standard GGA. This is essential for reliably verifying possible half-metallicity and the spintronic suitability of CrZrCoSn and CrHfCoSn. GGA in the form of Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof functional is the most reliable and widely used approach utilized in first-principles-based studies, as it provides a good balance between accuracy and computational time and cost32. Since, GGA method underestimates the electronic band gap of the insulators and semiconductors, we have incorporated the mBJ potential in all our calculations. mBJ is a semi-local potential that mimics the optical dependent behaviour and leads to more reliable outcomes of spin-polarized and electronic properties. It also offers accuracy comparable to various expensive methods, such as GW33 and hybrid (HSE) functionals34. In the FP-LAW method, the unit cell of our HAs is classified into two regions: the interstitial region and the non-overlapping muffin-tin spheres. The radius of the muffin-tin sphere is chosen precisely to avoid charge leakage outside the tin spheres. Geometrical optimization/relaxation is performed until the charge and energy criteria are reached up to 10− 3 and 10− 7 eV/atom, respectively. To ensure the self-consistency, we have used a 22 × 22 × 22 k-point mesh, along with 328 k-points in the Brillouin zone. Semi-classical Boltzmann theory35 implemented in the Boltz Trap code36 is employed to determine the thermoelectric properties. A highly dense k-point mesh of 100,000 points is opted for calculating various transport coefficients. Within the constant relaxation time approximation (CRTA), which is valid when the relaxation time does not vary strongly at the energy scale of kBT37, the value of τ is fixed at 2 × 10− 15 s. This value is consistent with the theoretical estimate based on the Heisenberg uncertainty principle τ ≈ ℏ/(2kB T)38 and falls within the experimentally validated range of 10− 15 to 10− 14 s39,40. This approach has been extensively validated for thermoelectric property calculations in similar material systems41,42. The Seebeck coefficient is determined by Eq. (1).

where e, T, Ω, σαβ, ε, µ, and f0 are the electronic charge, temperature, volume of unit cell, electrical conductivity tensor, energy, chemical potential, and Fermi-Dirac distribution, respectively. The optical properties43 of the considered HAs are studied through linear response formulism implemented in WIEN2k code. Frequency-dependent dielectric function is studied by Eq. (2).

where ε1(ω) and ε2(ω) are the real and imaginary parts of the dielectric functions. Furthermore, for thermodynamic properties, we have used the Gibbs244 package integrated with the WIEN2k code. It is based on the quasi-harmonic Debye model to calculate pressure and temperature-dependent properties. The lattice thermal conductivity was determined by Slack’s method45.

where, A = 3.1 × 10− 6, γ is Grüneisen parameter, \(\:{\theta}_{D}\) represents Debye temperature, n is the number of atoms in the unit cell, V is volume per atom, and m is the average mass of all atoms in the lattice. The spin polarization (P) at the Fermi level (Ef) is calculated by Eq. (2).

where ρ↑ (Ef) and ρ↓(Ef) are the density of states depending on spin (up and down).

Results and discussion

Structural properties

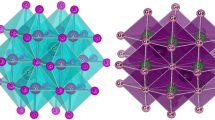

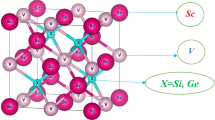

For X2Y′Z Heusler alloys, the constituent atoms crystallize in the cubic L21 space group, where the X atoms are situated at 8c (1/4, 1/4, 1/4) position (Wyckoff position) while Z and Y′ atoms occupy 4a (0, 0, 0) and 4b (1/2, 1/2, 1/2) sites respectively. Both Z and Y′ atoms are the most electronegative atoms, and exhibit NaCl (rock salt) type crystal structure [46]. They coordinate octahedrally due to ionic interaction. X atoms, with electronegativities between those Z and Y′ atoms, fill the voids of tetrahedral space. These crystal structures can be easily understood by the zinc-blende type sub-lattice, made up of one Z and X atoms, forming covalent chemical bonding between them, and the remaining X and Y′ atoms occupy tetrahedral and octahedral shapes, respectively (Fig. 1). In this step, we have explored the stability of the crystal structures of our HAs. We started from the relaxation of the crystal structure to achieve relaxed cell parameters and determine magnetic and electrical properties. The variation of total energy with cell volume for the investigated halide antimonates (HAs) is listed in Table 1 for each phase, and the relaxed crystal geometries are shown in Fig. 2. The energy–volume data were fitted to the third-order Birch–Murnaghan equation of state to obtain the equilibrium volume \(\:{V}_{0}\), equilibrium energy \(\:{E}_{0}\), bulk modulus \(\:{B}_{0}\), and its pressure derivative \(\:{B}_{0}^{{\prime\:}}\).

Table 1. Calculated equilibrium volumes \(\:{V}_{0}\)(Å3), equilibrium energies \(\:{E}_{0}\)(eV), bulk moduli \(\:{B}_{0}\)(GPa) and pressure derivatives \(\:{B}_{0}^{{\prime\:}}\)for the studied HAs obtained from third-order Birch–Murnaghan fits to the DFT energy–volume data. Our findings confirm that the Type 1 phase possesses minimum energy, as shown in Fig. 2. Thus, our studied HAs are energetically stable and Type 1 phase.

Further, to check the possible experimental realization and chemical stability of proposed HHs47,48. we have determined their cohesive energy (Ec) and formation energy per unit cell (Ef). Cohesive (Ec) and formation energies (Ef) are determined by equations (ii) and (iii), respectively.

Here, \(\:{E}_{CrZCoSn}^{total}\) is total energy the CrZCoSn molecule/ unit cell. \(\:{E}_{Cr}^{Bulk}\) \(\:{E}_{Zr/Hf}^{Bulk}\), \(\:{E}_{Co}^{Bulk}\) and \(\:{E}_{Sn}^{Bulk}\)are the total energies of bulk Cr, Z(Zr, Hf), Co and Sn atoms respectively. \(\:{E}_{Cr}^{iso}\), \(\:{E}_{Zr/Hf}^{iso}\), \(\:{E}_{Co}^{iso}\:\)and \(\:{E}_{Sn}^{iso}\) are the isolated atomic energies of Cr, Zr/Hf, Co and Sn atoms, respectively, and \(\:{E}_{CrZCoSn}^{total}\) is the total energy per unit of HAs. The formation energies of CrZrCoSn (− 0.263 eV/atom) and CrHfCoSn (− 0.259 eV/atom) are evaluated using ground-state energies of all constituent atoms. The negative values confirm the thermodynamic stability of both Heusler alloys against decomposition into elemental phases49. Also, the magnitude of EC, which determines the bond strength between the constituent atoms, is very high (20.41 eV) for the Type-2 phase. This confirms the stronger bond strength between the constituent atoms high chemical stability of HAs. Ef from our study are in good agreement (Table 1) with extracted data from the Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD). The minor differences between our and OQMD values are due to the implementation of different DFT methods.

Electronic properties

The electrical properties of the considered HAs have been studied by spin-projected electronic band structures (refer to Fig. 3) and total (TDOS) (Fig. 3) and projected density of states (PDOS) (see Fig. 4). Figure 3 represents the band structure plots of optimized CrZrCoSn HAs. Since the PBE-GGA method underestimates Eg, we have also analyzed the electronic band structure via the mBJ method. Figure 3 also suggests that our HAs have an indirect Eg near the Fermi level in the up-spin channel. Both HAs been found to exhibit HM nature. HM is characterized in opposite spin channels. Eg was studied through the lowest unoccupied and highest occupied energy bands of majority or minority spin channels. HM Eg is the lowest energy required to flip an electron from the minority spin channel to the majority spin channel. Eg and HM energy gaps (EHM) in both spin-channels are listed in Table 2. To assess the improvement obtained beyond the PBE-GGA functional, we compared the calculated electronic band gaps using both GGA and the mBJ potential. For CrZrCoSn, the band gap changes only slightly from 0.84 eV (GGA) to 0.85 eV (mBJ), indicating a minor correction. However, for CrHfCoSn, the GGA band gap of 0.15 eV increases significantly to 0.77 eV with mBJ, clearly correcting the strong underestimation produced by GGA. These results show that while GGA provides reasonable trends, mBJ offers a much more reliable description of the conduction and valence band edges, especially for systems where GGA markedly underestimates the gap. Notably, these corrections do not affect the total magnetic moments, confirming that the improvements mainly refine the electronic structure near the Fermi level. A high magnitude of Eg in the minority spin channel shows the robustness of HM against the distortion of the crystal lattice. TDOS and PDOS under the mBJ-GGA technique are also plotted in Figs. 3 and 4. The major contribution to TDOS at the Fermi level arises due to strongly hybridized d-d orbitals of Co-3d, Cr-3d, and Zr-4d states. The 100% spin polarization, contributed in both spin-channels, is the confirmation of HM characteristics of our HAs. The reasons for the origin of Eg in HM can be explained by three methods: hybridized d-d orbitals, charge transfer, and formation of a covalent bond. Here, we had considered the d-d hybridization of atomic orbitals between the transition metal (TM) elements to figure out the origin of HM Eg in our HAs. Figure 4 shows the schematic of the hybridization of d-d orbitals among TM elements of our HAs. Orbitals of Z atoms site can only overlap with the orbitals at Co/Cr sites, and the same for the t2g orbitals. In our HAs, hybridization of 4d orbitals of Z and Co atoms has formed 5 non-bonding bands (2eu and 3t1u) and 5 bonding bands (3t2g and 2eg). Also, 3d orbitals of Ti atom hybridize with 4d orbitals (3t2g and 2eg) of Zr–Sn and form bonding and anti-bonding energy bands, while 5 non-bonding and hybridized 4d atomic orbitals (2eu and 3t1u) are still left unhybridized. Furthermore, the contribution of 5d orbitals in spin channels is determined as 3t2g, 2eg, 2eu, 3t1u, 3t2g, 2eg, and these are distributed from upper to lower energy levels. The main group of Z atoms creates 1s and 3p atomic orbitals that are completely occupied by HAs and are below the hybridized d orbitals. Triple-degenerate t1u states are unoccupied in both spin channels, and Eg is formed between t1u and t2g orbitals in the spin channels of HAs. Eg, decrease by a small amount compared to that of the mBJ and PBE-GGA methods. In CrZrCoSn, we reported a similar distribution of orbitals as that of mBJ- GGA. On the other hand, for CrHfCoSn, the Fermi level slightly moves towards the negative energy region and tends to decrease HM. Sn atoms had a negative magnetic moment (MM); therefore, these atoms exhibit a ferrimagnetic arrangement with neighboring atoms. Spin-dependent energy bands are crucial to study magnetic and electric characteristics. The spin-dependent characteristics tell whether the HAs can be utilized in spintronic (especially spin filter) devices or not. The degree to which the spin of electrons is aligned in a particular direction gives the measurement of spin polarization. Mathematically, spin polarization (P) can be calculated by using Eq. (6). Figure 5 represents the charge density plots of our HAs, in which the bright regions around the atoms are regions of high charge density. The region of low charge density between pairs of atoms represents weaker metallic bonds. The overlapping of charge density between Co-Cr, Hf-Cr, and Hf-Sn indicates the hybridization50.

We see that for the CrZrCoSn compound, the conduction band in spin up and spin down channels is primarily of hybridized states of d orbitals of Zr, Co, Cr, and 5p states of Sn atoms, while in the valence band, major contribution arises from d orbitals of Cr and Zr and p-orbitals of Sn atoms. On the other hand, for the CrHfCoSn compound, the contribution of the d orbital of the Hf atom majorly contributes to the conduction band in the spin up channel, and its contribution is almost equal in valence as well as conduction band in the spin down channel. In both channels, the d orbital of the Cr atom majorly dominates in the valence band. The distribution of the p orbital of the Sn atom in both bands is almost uniform for both spin channels.

Magnetic moment and Slater-Pauling rule

In Table 2, the magnetic moments (MMs) of CrZCoSn (Z = Zr, Hf) HAs calculated by PBE-GGA and mBJ method are presented. The obtained value of MM aligns with the Slater-Pauling rule as described below;

where, Mt and Zt are the total MM and total valence electrons. HM alloys exhibit an integral value of MM. To understand why considered HAs adhere specific Slater–Pauling rule, we have analyzed the occupied energy levels in both spin channels that possess a gap between the energy bands. Mt can be calculated as;

where N↑ and N↓ denote majority and minority spins, respectively. The relationship between valence electrons and spin imbalance can be described by the origin of Eg in one spin channel of HAs. Any disorder present in the compound results in a deviation from the Slater-Pauling rule. MM and the total no. of valence electrons possess a direct relation. Magnetic properties are described by PDOS calculated from the mBJ GGA + U method. An increase in the degree of exchange splitting results in Mt. From Table 2, it is clear that for both HAs, the maximum MM is found for the Cr atom. In the CrZrCoSn alloy, Zr and Sn atoms have negative moments while Co and Cr atoms exhibit positive MMs. Thus, the MMs of Zr and Sn atoms are aligned in opposite directions to Co and Cr atoms. While in compound CrHfCoSn HA, Sn atoms have positive MM (determined by PBE and mBJ study). Mt for CrZrCoSn alloy, determined by PBE and mBJ studies, are 4.97 and 5.00 µB, respectively. Similarly, for the CrHfCoSn alloy, Mt determined by PBE and mBJ studies are 4.84 and 4.99 µB, respectively. Even after the introduction of the U parameter, no significant change is found in Mt. Thus, both HAs had almost the same magnitude of total MM. Therefore, both HAs had similar magnetic ordering and net spin. Thus, the HM nature in our HAs is the result of spin-dependent hybridization of Cr(d) and Co(d) orbitals. In the minority spin channel, crystal field effects and the interaction between d-d orbitals are responsible for band gap opening between antibonding and bonding states. On the other hand, the majority spin channel maintains its metallic character near the Fermi level. These factors confirm the half-metallic nature of alloys as only one spin channel is responsible for conduction, which is the key requirement of all spintronics devices51,52. Furthermore, the integral magnetic moment of our HAs is in accordance with the Slater–Pauling rule. It arises from the alignment of unpaired spins within the alloys. Since Hf and Zr are less magnetic, the substitution of these atoms only affects the hybridization and band structure of alloys. Also, the L21 space group of these alloys promotes a well-arranged magnetic ordering in which magnetic moments arrange in such a manner that they sum to an integer value of µB.

Thermoelectric properties

To gain insights into the thermoelectric (TE) behaviour of our Has53,54,55,56,57, we have determined different thermoelectric parameters, including Seebeck coefficient (S), power factor, electrical conductivity (κe), and thermal conductivity (σ). For efficient TE materials, low κe/τ with large values of S and σ/τ are expected. A material with high S means that the material can generate high electric voltage at a certain temperature difference. Thermal conductivity (κ) of metallic materials has two main components: electronic thermal conductivity (κe) and lattice thermal conductivity (κL). κe is due to the movement of charge carriers or electrons, while κL is due to phonon vibrations. κe is directly related to the electrical conductivity of the materials. Higher electrical conductivity indicates higher κe. Although these parameters are interconnected. For the TE performance of our HAs, we had computed the S, σ/τ, κe/τ, ZT, and power factor (PF). Boltzmann theory has been utilized to study the electronic transport properties. Since the PBE functional underestimates Eg between bands, the thermoelectric properties are studied through TB-mBJ methods. Transport properties are studied and plotted within the temperature range of 200–1200 K, as shown in Fig. 6. Seebeck coefficient (S) of HAs is depicted in Fig. 6. S is calculated by the electronic DOS obtained from DFT calculations. For CrZrCoSn and CrHfCoSn, S is positive up to 450 K and 300 K, respectively. Thus, within this temperature range, holes are the primary charge carriers in both HAs. Thus, on applying temperature up to these values, holes move from the hot to the cold side of HAs, and a positive voltage arises across the HAs. Therefore, CrZrCoSn and CrHfCoSn HAs act as p-type materials up to 450 K and 300 K temperature values. Beyond a 450 K temperature value, CrZrCoSn behaves as an n-type material while CrHfCoSn suffers a shift from n-type to p-type nature beyond a temperature of 900 K. While for CrHfCoSn HA, S decreases gradually with increasing temperature. This decrease in S is mainly due to an increase in carrier concentration. The temperature rise generates more electron-hole pairs, resulting in a higher scattering effect and reducing the value of S. The negative value of S confirms that both HAs are n-type, and the majority charge carriers are electrons. Figure 6a depicts the S of CrZCoSn (Z = Zr, Hf) HAs. As the applied temperature increases, the electrical conductivity of both HAs also increases due to high charge carrier density, which is the most general trend in materials. Near 700 K temperature, both HAs exhibit the same value of electrical conductivity. At room temperature, the electrical conductivity of CrHfCoSn is higher than that of CrZrCoSn HA. The electronic thermal conductivity (κe) of CrZCoSn (Z = Zr, Hf) HAs are plotted in Fig. 6d. According to Wiedemann–Franz law electronic thermal conductivity and electrical conductivity of the materials are related as

Thus, it is logical to expect the same trend of electronic thermal and electrical conductivity. From Fig. 6, it is clear that as the applied temperature increases, electrical thermal conductivity increases linearly and becomes maximum at 1200 K. A reverse trend is observed for lattice thermal conductivity (κL). Dissimilar to κe, κL decreases with rising temperature. This decrease in κL is due to growth in phonon population, resulting in more phonon scattering. This increased phonon intensity disturbs the heat flow, leading to a reduction in thermal conductivity. Also, at higher temperatures, phonons of higher frequency and shorter lifetime become excited. These phonons have a short mean free path, due to which the thermal conductivity decreases. Another important parameter for measuring the efficiency of a thermoelectric material is the power factor (PF), expressed as

PF is a balance between electrical conductivity and Seebeck coefficient. From Fig. 6, it is clear that as the temperature increases, PF for CrHfCoSn increases gradually. While for the CrZrCoSn alloy, it decreases initially within a temperature range of 500–600 K and then increases from 600 K to 1200 K temperature range. Up to 300 K, PF for CrZrCoSn remains higher than that of CrHfCoSn, but after 280 K, PF for CrHfCoSn becomes higher than CrZrCoSn. Also, both HAs exhibit the same value of PF near room temperature (300 K). The dip in the S of CrHfCoSn near 500 K originates from the temperature-driven change in the dominant charge carriers. At lower temperatures, electron transport prevails, resulting in a strongly negative S value. With increasing temperature, additional carriers are thermally activated, and states near the valence-band edge begin to contribute, leading to the onset of bipolar conduction. Around ~ 500 K, the growing hole contribution partially offsets the electron contribution, giving rise to the observed minimum in S. Beyond this temperature, hole involvement becomes increasingly significant, which decreases the absolute magnitude of the negative S and causes the curve to rise. Such a trend is typical for narrow-gap semiconductors and half-metallic materials where electron–hole asymmetry governs the thermoelectric response58,59,60.

Optical properties

The investigation of the optical properties of materials is crucial in materials research. A comprehensive understanding of the optical and dielectric properties of the materials is required for improvements in different photonic devices for optical communications61,62,63,64,65. The optical characteristics of CrZCoSn (Z = Zr and Hf) HAs are studied through the FP-LAPW and mBJ, along with random phase approximation (RPA). The frequency-dependent dielectric matrix in RPA is given as

where, G and Gʹ represent the reciprocal lattice vectors, χ° (q, ω) is the irreducible polarizability matrix within scf approach, and q denotes the Bloch vector of the incident wave. ε1(ω) is related to the dispersion relation of EM waves, while ε2(ω) is the difference of wave functions of unoccupied and occupied energy states, calculated by the elements of the momentum matrix. The real part ε1(ω) of the dielectric function is determined by the Kramer-Kroning relation

where e is the electronic charge and P is the principal integral. The imaginary part ε2(ω) is derived from RPA as

According to the Drude model, intra-band transitions contribute to IR absorption of free electrons. Figure 7 shows the ε1(ω) for CrZCoSn (Z = Zr and Hf) HAs, plotted against incident photon energy within the energy range 0–10 eV. Both HAs exhibit peak values at almost the same energy of incident photon (near 1 eV) (Fig. 7a). Furthermore, we see that ε1(ω) of CrZrCoSn and CrHfCoSn becomes zero near 2.3 eV and 4 eV energy values, respectively. Beyond 4 eV, ε1(ω) of both HAs becomes negative, which suggests that beyond 4 eV, both HAs opposed the propagation of the electric field and exhibit plasmonic behaviour. Also, beyond the 4 eV energy region, HAs reflect light rather than transmit it. Figure 7b is the plot of ε2(ω) of CrZCoSn (Z = Zr and Hf) HAs with photon energy of 0–10 eV. It confirms the metallic nature of both HAs. For both HAs, ε2(ω) becomes maximum at 1.5 eV photon energy, and beyond 1.5 eV energy value, it rapidly decreases. It again indicates plasmon oscillation of incident energy. To further analyse the optical properties of CrZCoSn (Z = Zr and Hf) HAs, we have computed the refractive index N(ω), which is a dimensionless physical quantity that gives the velocity of light through any material. It also possesses two components: real component n(ω) and imaginary component k(ω). n(ω) is the phase velocity of the photon within the material, and k(ω) shows the absorption behavior of light.

Figure 7c,d are the plots of n(ω) and k(ω) of CrZCoSn (Z = Zr, and Hf) HAs with photon energy. The static values of n(ω) for CrZrCoSn and CrHfCoSn HAs are 5.5 and 5.7, respectively. From Fig. 7c, it is clear that the photon of energy 1.5 eV travels through both HAs with the minimum velocity due to maximum values of refractive index n(ω). Light absorption behaviour of materials is measured by the extinction coefficient k(ω). Therefore, ε2(ω) and extinction coefficient k(ω) exhibit the same profiles. However, as the energy of the incident photon increases, the value of the extinction coefficient rapidly decreases to 2 eV at 10 eV photon energy from its maximum value. Figure 7e consists of the optical conductivity σ(ω) of HAs with respect to incident photon energy. We found that our HAs are promising candidates for optoelectronic applications because of their excellent visible-range optical conductivities and high absorption coefficients. The primary peak for both HAs is found in the IR region, suggesting that these HAs could be used in IR sensors and detectors. The rest of the peaks are in the UV and beyond the UV range, which makes these HAs suitable for UV applications. The conductivity decreases drastically in the IR region, yet the absorption saturates in the UV region. Figure 7f shows the variation of absorption coefficient α(ω) of our HAs with respect to the energy of the photon, ranging from 0 to 10 eV. The α(ω) is determined as

where c is the velocity of light. As expected, these HAs exhibit metallic behaviour, and the absorption of photons starts at very low photon energies. Absorption curve rapidly ascends in the visible range and becomes maximum at 8 eV photon energy. A sufficient amount of the light is found in the visible and IR ranges, and it significantly contributes to the electronic transitions. To study the amplitude and intensity of the reflected wave, we have plotted the reflectivity R(ω) of CrZCoSn (Z = Zr, Hf) HAs in Fig. 7g, which is calculated by Eq. (18).

R(ω) of both HAs is determined by the ratio of the reflected amount of energy to the incident energy at the surface of HAs. Both HAs exhibit zero-band gap character along with a static value of reflection index 0.47 and 0.49, respectively. Notably, for all graphs in the IR, visible, and UV ranges, CrZrCoSn and CrHfCoSn respond more quickly to incident photons than CrZCoSn (Z = Zr and Hf). Finally, the loss function L(ω) of our HAs is plotted in Fig. 7h. It is determined by Eq. (19).

Optical Excitations in optical spectra caused by fast-moving electrons are defined by the incident photon energy. L(ω) arises due to electron excitations and originates when a fast-moving electron passes through a material. As the energy of the incident photon increases, energy loss also increases.

Thermodynamic properties

To study the behavior of our HAs towards pressure and temperature, we have used the quasi-harmonic Debye model employed in the Gibbs program44. Variation of bulk modulus (B), heat capacity at fixed volume (CV), Debye temperature (θD), entropy (S), and thermal expansion (α) are determined within a pressure and temperature range of 0 to 101 GPa and 0 to 1200 K, respectively. First, B exhibits an increasing trend with pressure at constant temperature. Next, a minor change in this parameter is found within a 0–100 K temperature range. Beyond 100 K, it displays a decreasing trend with temperature rise. However, B decreases slowly at high pressure. Our findings suggest that the hardness of our HAs will increase at high pressure values, while a rise in temperature causes a contrary trend. Also, at 0 K and 0 GPa situations, the calculated values of B for CrZrCoSn and CrHfCoSn HAs are 121.84 and 122.74 GPa, respectively, which match well with the earlier determined ones through elastic and structural properties66. Moreover, at zero pressure and ambient temperature (see Table 3), the values of B are 117.43 and 118.73 for CrZrCoSn and CrHfCoSn, respectively. Thus, CrHfCoSn exhibits strong hardness and crucial compressibility.

The Debye temperature (θD), which is related to many useful physical characteristics, including elasticity, melting temperature, lattice vibration, and specific heat, is the necessary parameter in the QHDM. The curves of θD with temperature at different pressures are plotted in Fig. 8. At a fixed pressure, as the temperature rises, θD decreases linearly. However, at a fixed temperature, θD rises with increasing pressure. Also, one can see that θD plots show the same features as compared with those of B, as both parameters indicate the hardness of the material67.

CV of any material is an important factor that gives information about the phase transition and lattice vibration. Figure 8 represents the effect of temperature on Cv at different pressures. The outcomes confirm that the rise of pressure does not affect Cv. It increases rapidly with the initial 0–300 K temperature range, and at low temperatures, Cv obeys the T3 law. At 0 GPa and 300 K conditions, Cv has 93.6 and 92.21 J/mol− 1 K− 1 values for CrHfCoSn and CrZrCoSn, respectively. In the 300 to 1000 K temperature range, Cv rises slowly with an increase in temperature. At a temperature value (T = 1100 K), no more change is found, and its value approaches approximately 99.3 and 99.3 J mol− 1 K− 1 for CrZCoSn (Z = Hf and Zr) HAs. As a result, Cv is quite close to the Dulong-Petit classical limit, which is a common phenomenon in all solids68.

Furthermore, we have checked the change in thermal expansion coefficient (α) with temperature at different pressure values. It is clear from Fig. 8, α increases sharply within a temperature span of 0–300 K, followed by a regular rise, and after room temperature, particularly in high high-pressure range; it increases linearly with a small slope. At room temperature, α increases (from 22.14 to 5.62 × 10− 5/K for the CrZrCoSn compound), whereas it also increases from 0 to 78.5 × 10− 5/K for CrHfCoSn when the temperature is increased from 0 to 1200 K at 0 GPa pressure.

S provides necessary information about vibrational characteristics of HAs, leading to the information of the various applications such as refrigerators, heat engines, and heat pumps. Figure 8 is the plot of entropy with temperature at different values of pressure. From plots, it is clear that the stable equilibrium phase corresponds to S = 0 at 0 K temperature and 0 GPa pressure conditions. Moreover, the determined entropy values of 124 and 113 J/mol− 1 K − 1 for CrHfCoSn and CrZrCoSn, respectively. It indicates that CrZrCoSn is more ordered than CrHfCoSn at 0 GPa and 300 K. Finally, as the temperature crosses 800 K, S gains high values due to the atomic vibrations for our HAs. Figure 8i,j show a continuous and monotonic rise in entropy with temperature for both HAs. Starting from low-temperature values of approximately 10–20 J/mol K near 100 K, the entropy increases sharply up to 150–180 J/mol K around 600 K, and ultimately exceeds 220–240 J/mol K at temperatures approaching 1200 K. This substantial variation is highly relevant for caloric applications. In barocaloric materials, the magnitude of the pressure-induced entropy change governs the achievable thermal effect during compression–decompression cycles. Materials displaying a large ∂S/∂T slope, such as observed here, particularly in the lower-to-mid temperature region (100–600 K), are known to possess enhanced barocaloric strength. The relatively steep entropy increase below 400 K suggests potentially significant ΔS under moderate applied pressures69, which is desirable for efficient near-room-temperature cooling. Furthermore, the smooth, non-anomalous behavior of S across the entire range indicates structural and thermodynamic stability, a key requirement for cyclic operation in solid-state refrigerators, heat engines, and heat pumps. Therefore, the thermodynamic trends observed in these HAs provide strong indications that these HAs may exhibit measurable and technologically relevant barocaloric responses.

Conclusion

In summary, we have explored the structural, electronic, and magnetic properties of CrZCoSn (Z = Zr, Hf) with the help of a technique utilizing PBE-GGA, and mBJ methods along with PBE exchange correlation functional. The occupation of atoms at different sites in Type I, II, and III configurations confirms that Type I is the most stable arrangement across all HAs. The negative Ef and Ec values confirm that these HAs are stable and can be synthesized experimentally. Therefore, further characteristics along with the magnetic stability of the Type 1 configuration are discussed. These HAs are HM in nature, with Eg of 0.84 and 0.85 eV for CrZrCoSn; and 0.15 and 0.77 eV for CrHfCoSn from PBE-GGA and mBJ methods, respectively. Magnetic characteristics arise due to hybridized d orbitals of Z, Co, and Cr and satisfy the Slater-Pauling 18-electron rule. Also, calculated Tc for CrZrCoSn and CrHfCoSn HAs are 1482.77 and 961.16 K, respectively. Optical spectra reveal that absorption of EM energy occurs in the near UV and visible regions of the spectrum. According to current research, spin polarization, a narrow Eg, and high ZT values are all desirable parameters for thermoelectric and spintronic applications. The transport and magneto-electronic properties may inspire the synthesis of these HAs in future experiments for applications in spintronics, magnetic materials, and thermoelectricity. The strong HM properties make them suitable for spintronic applications. Here, we want to highlight that the Curie temperature has been calculated using mean-field approximation, which typically gives slightly higher values; still, this approach is widely used for qualitative comparison. More accurate results can be achieved through Monte Carlo simulations as this method better captures temperature-related spin fluctuations43,44. Our results collectively indicate that both HAs are thermodynamically stable, whereas the experimental synthesis of these alloys could be challenging. Moreover, recent progress in synthesis and deposition techniques has opened the possibilities of synthesizing the metastable Heusler alloys through various synthesis techniques, including pulsed laser deposition, molecular beam epitaxy (MBE), and sputtering. For instance, Gabor et al. studied the growth of Co and Pt-based Heusler alloys through MBE and achieved ultrathin films of various HAs with strong perpendicular magnetic anisotropy45. Furthermore, Grunin et al. formed thin films of Ni-Mn-In-based Heusler alloy using pulsed laser deposition46. These studies confirm that the experimental realization of our alloys is possible by appropriate synthesis and deposition techniques.

Data availability

Data will be available on the reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Tavares, S., Yang, K. & Meyers, M. A. Heusler alloys: Past, properties, new alloys, and prospects. Prog. Mater. Sci. 132, 101017 (2023).

Zhou, Y., Zhang, J. M., Huang, Y. H. & Wei, X. M. The structural, electronic, magnetic and mechanical properties of d0 binary heusler alloys XF3 (X = Be, Mg, Ca, Sr, Ba). J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 138, 109246 (2020).

Hayashi, K., Eguchi, M. & Miyazaki, Y. Structural and thermoelectric properties of ternary full-Heusler alloys. J. Electron. Mater. 46, 2710–2716 (2017).

Galanakis, I., Dederichs, P. H. & Papanikolaou, N. J. P. R. B. Origin and properties of the gap in the half-ferromagnetic heusler alloys. Phys. Rev. B. 66, 134428 (2002).

Nayak, A. K. et al. Design of compensated ferrimagnetic heusler alloys for giant tunable exchange bias. Nat. Mater. 14, 679–684 (2015).

Hirohata, A. et al. Development of antiferromagnetic Heusler alloys for the replacement of iridium as a critically raw material. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 50, 443001 (2017).

Bose, S. K., Kudrnovský, J., Drchal, V. & Turek, I. Pressure dependence of curie temperature and resistivity in complex heusler alloys. Phys. Rev. B—Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 84, 174422 (2011).

Hu, J., Granville, S. & Yu, H. Spin-dependent thermoelectric transport in Cobalt‐Based heusler alloys. Ann. Phys. 532, 1900456 (2020).

Ling, Y. et al. Strain control of phase transition and exchange bias in flexible heusler alloy thin films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 13, 24285–24294 (2021).

Farshchi, R. & Ramsteiner, M. Spin injection from heusler alloys into semiconductors: A materials perspective. J. Appl. Phys. 113 (2013).

Kämmerer, S., Thomas, A., Hütten, A. & Reiss, G. Co2MnSi heusler alloy as magnetic electrodes in magnetic tunnel junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 85, 79–81 (2004).

Hirohata, A., Sagar, J., Fleet, L. R. & Parkin, S. S. Heusler Alloy Films for Spintronic Devices 219–248 (Properties, Growth, Applications, 2015).

Farshchi, R. & Ramsteiner, M. Spin injection from heusler alloys into semiconductors: A materials perspective. J. Appl. Phys., 113, (2013).

Bainsla, L. et al. Y. K., High spin polarization in cofemnge equiatomic quaternary heusler alloy. J. Appl. Phys., 116 (2014).

Galanakis, I., Dederichs, P. H. & Papanikolaou, N. J. P. R. B. Slater-Pauling behavior and origin of the half-metallicity of the full-Heusler alloys. Phys. Rev. B. 66, 174429 (2002).

Hillebrands, B. & Felser, C. High-spin polarization of heusler alloys. J. Phys. D. 39, E01 (2006).

Galanakis, I., Özdoğan, K., Aktaş, B. & Şaşıoğlu, E. Effect of doping and disorder on the half metallicity of full Heusler alloys. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89 (2006).

Hirohata, A., Frost, W., Samiepour, M. & Kim, J. Y. Perpendicular magnetic anisotropy in heusler alloy films and their magnetoresistive junctions. Materials. 11, 105 (2018).

Mizukami, S. et al. T low damping constant for Co2FeAl heusler alloy films and its correlation with density of States. J. Appl. Phys. 105 (2009).

Hu, X. et al. Searching high spin polarization ferromagnet in Heusler alloy via machine learning. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 32, 205901 (2020).

Hirohata, A. & Lloyd, D. C. Heusler alloys for metal spintronics. MRS Bull. 47, 593–599 (2022).

Geerlings, P., De Proft, F. & Langenaeker, W. Conceptual density functional theory. Chem. Rev. 103, 1793–1874 (2003).

Li, S., Zhao, H., Li, D., Jin, S. & Gu, L. Synthesis and thermoelectric properties of half-Heusler alloy YNiBi. J. Appl. Phys. 117 (2015).

Ahmad, R. & Mehmood, N. A density functional theory investigation of half-Heusler compounds RhVZ (Z = P, As, Sb). J. Supercond. Novel Magn. 31, 1577–1586 (2018).

Korzhavyi, P. A., Ruban, A. V., Odqvist, J., Nilsson, J. O. & Johansson, B. Electronic structure and effective chemical and magnetic exchange interactions in Bcc Fe-Cr alloys. Phys. Rev. B—Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 79, 054202 (2009).

Mentefa, A. et al. First-principles calculations to investigate structural, electronic, elastic, magnetic, and thermodynamic properties of full-heusler Rh2MnZ (Z = Zr, Hf). J. Supercond. Novel Magn. 34, 269–283 (2021).

Wei, J., Guo, Y. & Wang, G. Exploring structural, mechanical, and thermoelectric properties of half-Heusler compounds RhBiX (X = Ti, Zr, Hf): A first-principles investigation. RSC Adv. 13, 11513–11524 (2023).

Petersen, M. et al. Improving the efficiency of FP-LAPW calculations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 126, 294–309 (2000).

Blaha, P., Schwarz, K., Madsen, G. K., Kvasnicka, D. & Luitz, J. Wien2k. An augmented plane wave + local orbitals program for calculating crystal properties. 60, 155–169 (2001).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Tran, F. & Blaha, P. Accurate band gaps of semiconductors and insulators with a semilocal exchange–correlation potential. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 226401 (2009).

Madsen, G. K. Functional form of the generalized gradient approximation for exchange: the PBEα functional. ArXiv Preprint cond-mat/0609365 (2006).

Reining, L. The GW approximation: content, successes and limitations. Wiley Interdiscipl. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 8, e1344 (2018).

Henderson, T. M., Paier, J. & Scuseria, G. E. Accurate treatment of solids with the HSE screened hybrid. Phys. Status Solidi (b). 248, 767–774 (2011). (2011).

Park, S., Woo, S., Mele, E. J. & Min, H. Semiclassical Boltzmann transport theory for multi-Weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. B. 95, 161113 (2017).

Madsen, G. K. & Singh, D. J. BoltzTraP. A code for calculating band-structure dependent quantities. Comput. Phys. Commun. 175, 67–71 (2006).

Mili, I., Latelli, H., Charifi, Z., Baaziz, H. & Ghellab, T. A simple formula for calculating the carrier relaxation time. Comput. Mater. Sci. 213, 111678 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Thermodynamic and electron transport properties of Ca 3 Ru 2 O 7 from first-principles phonon calculations and Boltzmann transport theory. Phys. Rev. B. 107, 035118 (2023).

Ricci, F. et al. An Ab initio electronic transport database for inorganic materials. Sci. Data. 4, 1–13 (2017).

Katsura, Y., Takagi, H. & Kimura, K. Roles of carrier doping, band gap, and electron relaxation time in the Boltzmann transport calculations of a semiconductor’s thermoelectric properties. Mater. Trans. 59, 1013–1021 (2018).

Hasan, S. et al. First-principles calculations of thermoelectric transport properties of quaternary and ternary bulk chalcogenide crystals. Materials 15, 2843 (2022).

Jayaraj, A., Siloi, I., Fornari, M. & Nardelli, M. B. Relaxation time approximations in PAOFLOW 2.0. Sci. Rep. 12, 4993 (2022).

Ambrosch-Draxl, C. & Sofo, J. O. Linear optical properties of solids within the full-potential linearized augmented Planewave method. Comput. Phys. Commun. 175, 1–14 (2006).

Alberto Otero-de-la-Roza & Luaña, V. Robust treatment of the static data in a new version of the quasi-harmonic model code (Gibbs2). Comput. Phys. Commun. 182, 1708–1720 (2011).

Slack, G. A. Nonmetallic crystals with high thermal conductivity. Phys. Rev. A 139, A507–A515 (1965).

Manzoor, M., Abraham, J. A., Aslam, M., Al-Asbahi, B. A. & Sharma, R. A comprehensive DFT study on the physical attributes of Li-based half-Heusler compounds LiYXZ (X = Pt, Pd; Z = Si, Ge). Solid State Commun. 400, 115875 (2025).

Dey, A., Sharma, R., Dar, S. A. & Raza, H. H. A computational investigation on structural, mechanical, electronic, magnetic, thermoelectric and optical properties of CrX Pb (X = Sc, Ti) half-Heusler alloys. J. Supercond. Novel Magn. 34, 781–796 (2021).

Geleta, T. A. et al. A. Exploring the mechanical, vibrational, optoelectronic, and thermoelectric properties of novel half-Heusler fetax (X = P, As): a first-principles study. RSC Adv. 14, 4165–4178 (2024).

Kumari, M. et al. Theoretical insights into the structural, optoelectronic, thermoelectric, and thermodynamic behavior of novel quaternary LiZrCoX (X = Ge, Sn) compounds based on first-principles study. RSC Adv. 13, 29522–29535 (2023).

Azam, A. et al. First-principles study of magneto-electronic and thermoelectric properties of quaternary CoZrMnSb for spintronics and waste-heat recovery applications. Opt. Quantum Electron. 56, 1001 (2024).

Kumari, A. et al. Ab initio investigations of the structure-stability, mechanical, electronic, thermodynamic and optical properties of Ti₂FeAs heusler alloy. RSC Adv. 14, 6762–6775 (2024).

Azam, A. et al. Insight into the structural, optoelectronic, and thermoelectric properties of Fe₂HfSi heusler by DFT investigation. RSC Adv. 13, 15437–15447 (2023).

Abraham, J. A., Sharma, R., Dar, S. A. & Dey, A. DFT investigation on the electronic, optical and thermoelectric properties of novel half-Heusler compounds ScAuX (X = Si, Ge, Sn, Pb). Eur. Phys. J. Plus 136 (2021).

Dey, A., Sharma, R. & Dar, S. A. A computational investigation on structural, mechanical, electronic, magnetic, thermoelectric and optical properties of Bi-based half-Heusler alloys. Mater. Today Commun. 25, 101647 (2020).

Iram, N., Sharma, R., Ahmad, J., Khalid, S. & Alanazi, M. M. Theoretical investigation on the multifunctional attributes of RhHfX (X = P, As) half-Heusler semiconductor for advanced technological applications. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 206, 112829 (2025).

Arquam, H. et al. An examination of the vibrational, mechanical, thermoelectric features and stability of novel half-Heusler XVIn (X = Pd, Pt) by density functional theory computation. Phys. Status Solidi B. 261 https://doi.org/10.1002/pssb.202300571 (2024).

Manzoor, M. et al. Optoelectronic and thermoelectric properties of zirconium half-Heusler alloys RhZrX (X = P, As, Sb, Bi): an ab-initio investigation. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 35, 1845–1864 (2025).

Nazir, A., Raza, H. H., Ali, H. S., Yousaf, M., Qamar, F., & Khan, N. A DFT insight on the physical, optoelectronic and thermoelectric characteristics of half-Heusler NaZn(N/P) compounds for power generation applications. Solid State Commun. (2025).

Peng, Q. et al. B.Unveiling physical properties of LaMnSb and LuMnSb half-Heusler compounds for green energy applications: a DFT exploration. J. Rare Earths 43, 2461–2469 (2025).

Nazir, A., Khera, E. A., Manzoor, M., Al-Asbahi, B. A. & Sharma, R. High spin polarization and half-metallic ferromagnetism in novel half-Heusler FeCrX (X = S, Se and Te) alloys using first-principles calculations. Solid State Commun. 397, 115803 (2025).

Arquam, H. et al. Control of spin on structural stability, mechanical, magneto-optoelectronic and thermodynamic properties of RbTaX (X = P and As) materials: emerging candidates for opto-spintronics and spin filter applications. Solid State Commun. 391, 115632 (2024).

Dixit, A., Saxena, A., Abraham, J. A., Dubey, S., Sharma, R., Qaid, S. M. H., Štich, I., Aslam, M. & Zetsepin, A. Hydrostatic pressure-tuning of opto-electronic and thermoelectric properties of half-Heusler alloy RhTiP: a first-principles study. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 124, e27482 (2024).

Peng, Q., Iram, N., Sharma, R., Kumar, A., Saad Alsubaie, A., & Rehman, J. Ab-initio investigation of structural, electronic, thermoelectric and optical properties of full-Heusler X₂MnB (X = Ti, Zr) for energy-harvesting applications. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 170, 113240 (2024).

Nazir, A., Khera, E. A., Manzoor, M., Al-Asbahi, B. A. & Sharma, R. Tunable opto-electronic and thermoelectric response of alkali-based half-Heusler semiconductors AMgN (A = Rb, Cs) for sustainable energy: a computational approach. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 303, 117338 (2024).

Abraham, J. A. et al. E. K. Insight into the structurlastic, lattice-dynamical, optical, and thermoelectric properties of novel Heusler alloy LiCaBi by first-principles approach. Chin. J. Phys. 89, 859–870 (2024).

Behera, D., Al-Qaisi, S., Manzoor, M., Sharma, R., Srivastava, V., Al-Anazy, M. M., El Shiekh, E., & Mukherjee, S. K. First principles studies on optoelectronics and transport properties of KSrY (Y = Sb, Bi) for renewable energy application. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 303, 116765 (2023).

Kaur, N., Sharma, R., Al-Douri, Y., Srivastava, V. & Abd El-Rehim, A. F. Thermodynamic, thermoelectric and optoelectronic performances of Co₂MB (M = Nb, Ta) full-Heusler compounds for solar cell and UV-absorber applications. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 165, 107676 (2023).

Kaur, N., Sharma, R., Srivastava, V. & Chowdhury, S. Thermodynamic and thermoelectric properties of fecrtiz (Z = Si, Ge) quaternary heusler compounds. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 184, 107089 (2023).

Behera, D. et al. Theoretical insight on the electronic band structure, mechanical, vibrational and thermodynamic characteristics of antiperovskites RE₃InN (RE = Y, La). Mater. Today Commun. 35, 105618 (2023).

Funding

There is no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All persons who meet authorship criteria are listed as authors, and all authors certify that they have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for the content, including participation in the concept, design, analysis, writing, or revision of the manuscript. K.K., A.D., A.K.M.—Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, software, writing-original draft preparation, supervision. S.M., R.S.—Writing original draft preparation, visualization, investigation. writing- reviewing and editing, funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kumar, K., Dixit, A., Mishra, A.K. et al. Effect of spin polarization on multifunctional physical properties of the quaternary Heusler alloys CrZCoSn (Z = Zr, Hf) for energy technologies: A comprehensive DFT study. Sci Rep 16, 2284 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32151-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32151-2