Abstract

Ceria is a wide bandgap semiconductor oxide, however, by introducing oxygen vacancies (Vo), the electronic structure of ceria can be precisely tuned, resulting in a narrowed band gap and improved charge transport. Doping with lower-valent cations introduces Vo to maintain charge neutrality, thereby imparting robust chemiresistive and semiconducting properties. These vacancies act as active sites for analyte adsorption and are crucial for enhancing sensing performance. In this study, samaria-doped ceria was synthesized using a modified co-precipitation method. Structural analysis such as XRD, Raman spectroscopy, and HR-TEM confirm the formation of cubic fluorite-type structure in all samples. PL and UV–Vis spectroscopy show the enhanced defect levels with increase in Sm doping. XPS validated the presence of Vₒ and the oxidation states of Ce4+ and Sm3+. I-V characterization confirmed the ohmic conductance behaviour, while chemiresistive measurements show selectivity and sensitivity towards acetone. Additionally, kinetic parameters were extracted via Langmuir–Hinshelwood modeling, confirms the importance of oxygen vacancies in acetone sensing. Additionally, DFT based calculation shows that Sm-doping in ceria modulates its electronic structure by Fermi level shifting towards conduction band causing substantial availability of electrons inducing the formation of Vo.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction:

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) have diverse applications, ranging from use in everyday household products to their role in environmental processes and even as indicators of health conditions. They are commonly found in paints, cleaning products, adhesives, and other materials. Beyond their practical uses, VOCs also play a role in plant communication, insect defense, and can serve as markers for various biological and environmental processes. Moreover, daily life problem can be solved by monitoring VOCs1. Several types of electrical VOC sensors, such as chemiresistive, electrochemical, field-effect transistor, and chemocapacitive sensors, are commercially available, each offering distinct advantages and limitations2. Chemiresistive sensors, favored for their simplicity and cost-effectiveness, rely on changes in the electrical resistance of the sensing material caused by the interaction with analyte molecules, enabling straightforward and sensitive VOC detection. Their ability to operate at relatively low power, ease of fabrication, rapid response, and compatibility with miniaturized electronics make them particularly suitable for portable and real-time VOC sensing applications3,4.

In chemiresistive sensors, the materials serve as the core component. Materials commonly used for the fabrication of sensors include conductive polymers, metal oxides, metal nanoparticles, semiconductors, and nanocomposites5. The sensing reaction predominantly occurs at the surface of the materials, which makes the surface properties crucial for the sensor functionality. Therefore, introducing surface defects can significantly enhance the chemical and physical properties. This defect can be engineered intentionally by introducing deviations of oxygen atom arrangement from ideal stoichiometry, which leads to generate the oxygen vacancy (Vo) within the material6. However, further studies are required to fully comprehend the role of Vo in metal oxides for gas sensing7,8,9,10,11.

Vo are critical surface defects in metal oxides that not only increase carrier concentration by introducing additional charge carriers but also enhance electron mobility. Also, act as active sites for analyte adsorption, Vₒ play a dual role in modulating charge transport and facilitating surface reactions12,13,14. Vo in metal oxides can be generated through several key approaches15,16. Thermal treatment in reducing or inert atmospheres removes lattice oxygen, while chemical reduction with agents such as H2 or CO increases vacancy concentration17,18. Aliovalent doping introduces a charge imbalance19,20,21,22 compensated by vacancy formation, and irradiation techniques (UV, electron beam, microwaves) create localized defects23,24. Electrochemical methods can also drive oxygen ion removal, particularly in thin films and nanostructures25,26. These strategies enable precise control of vacancy concentration and distribution, thereby tuning catalytic, electronic, and sensing properties.

Ceria (CeO2) is a wide bandgap semiconductor with an optical bandgap of approximately 6 eV and localized Ce 4f states within this gap, often described as an effective transition around 3.5 eV. The remarkable oxygen storage capacity and redox flexibility exhibited by ceria are caused by the reversible transition between Ce3+ and Ce4+ oxidation states. This characteristic makes CeO2 highly valuable for applications in solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) and catalysis. Structurally, CeO2 crystallizes in a cubic fluorite lattice, where each cerium ion is coordinated by eight oxygen ions. When doped with lower-valence cations, ceria becomes non-stoichiometric, leading to the formation of Vo in order to maintain charge neutrality. Fig. S-1 of the supporting information (SI) explains the crystal structure of doped ceria. The defect generation process can be expressed using the Kröger-Vink notation19,27.

Cations such as Sm3+, Gd3⁺, and Dy3⁺ are utilized to create the Vo. Usually, this replacement takes place during the synthesis process. The Kröger-Vink notation is a way to express the balance between M3+ (Ce ¢), Ce4+ (Cex), and Vo.

Another factor, which plays a crucial role in achieving a non-distorted structure, is the ionic radius of the dopant. The ionic radii of Sm3+ (1.08 Å) and Gd3+ (1.05 Å) are comparable to that of Ce4+ (0.96 Å), ensuring excellent compatibility within the crystal lattice. Due to this compatibility, both Sm3+ and Gd3+ have been extensively studied as dopants in ceria-based electrolytes.

In the present work, a metal oxide-based chemiresistive sensor was fabricated for VOCs sensing, where cerium oxide was doped with different concentrations of Sm3+ ions, which generates Vo into the ceria lattice for charge neutrality in the crystal structure. This VO acts as a surface defect, improving the receptor site and transducer response to VOCs in the sensor. It is further hypothesized that optimizing Sm3+ doping level can fine-tune the structural and electronic properties of ceria, which enables efficient VOC detection across an extended temperature range. A first-principle based density functional formalism has been employed finally to understand the role of Sm-induced electronic environment in the CeO2, which is responsible for enhanced VOCs under optimal doping ranges.

Experimental

Sample preparation

To synthesize the samaria doped ceria (SDC), cerium nitrate hexahydrate (Ce(NO3)3·6H2O, 99.9%) and samarium nitrate hexahydrate (Sm(NO3)3·6H2O, 99.9%, (Sigma-Aldrich, India) were used as the precursors for cerium and samarium, respectively. Triethylamine (N(C2H5)3) served as the precipitating agent (Fisher Chemicals) and ethanol (CH3CH2OH) 99.9% (Fisher Chemicals) was utilized as a solvent. Cerium and samarium salts were mixed and diluted in anhydrous ethanol to make stock solutions with a concentration of 0.1 M. This procedure was used to ensure that the final compositions of the samples match with Ce1-xSmxO2-δ (where x = 0, 0.10, 0.20, and 0.30). Similarly, triethylamine was added to anhydrous ethanol to create a 0.4 M stock solution. The samples were labelled as 0SDC, 10SDC, 20SDC, and 30SDC as per the mole concentration of Sm in the samples.

During the synthesis, triethylamine solution was added dropwise to an Erlenmeyer flask containing a mixed metal nitrate solution. The reaction mixture was continuously stirred at a regulated rate of 2–3 mL/min. On completion of the precipitation, stirring was maintained for an additional hour to ensure thorough mixing. The precipitated solutions were filtered by suction filtration. To verify the completion of the precipitation, 10 mL of filtrate was mixed with a 1 M NaOH solution. The precipitates were thoroughly cleaned with anhydrous ethanol and repeatedly washed to remove unreacted triethylamine and other related byproducts. The samples were air-dried at ambient temperature for 24 h. The dried powders were then calcined in air at 400 °C for 4 h with a controlled heating rate of 5 °C/min. The particle formation mechanism is explained in section S-1, and a schematic representation is shown in Fig. S-9 of the SI. The powders were compressed under a pressure of 40 kPa to form uniform pellets. Each pellet was prepared using 250 mg of calcined powder, pressed into a disk of 12 mm diameter and 2 mm thickness for further studies.

Characterization

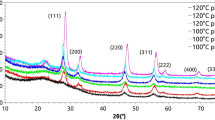

The crystallographic analysis was performed using X-ray diffraction (XRD) (Panalytical X’Pert Pro) equipment with CuKα radiation (λ = 1.540598 Å) over a 2θ range of 10°–80°. The crystallite size was calculated employing the Debye–Scherrer equation, D = Kλ/ꞵcosθ, where λ is the wavelength of the incident radiation, θ is the diffraction angle, and β is the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the diffraction peak, and K represents the Scherrer constant (0.98). The optical analyses were done in the range of 200–800 nm using Raman spectrometer (InVia Renishaw, UK) (532 nm laser). The band gap was found out by analysing the absorption data obtained from UV spectroscopy (PerkinElmer LAMBDA 365 +). It was determined by using Tauc plot equation: (αhν)n = A(hν-Eg), where α represents absorption coefficient, h is Planck’s constant (6.626 × 1034 m2kg/s), ν represents frequency (Hz), A is energy energy-independent constant, Eg is optical bandgap (eV), and n is the nature of transmission (n = 2 for direct bandgap material). Photoluminescence (PL) spectrophotometer (Horiba) was used to analyse the defect level in the sample. High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) (JEOL JEM-2100) technique was used to study the structure and composition of materials. To analyse the oxidation states and Vo, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were carried out using the ESCA + system (Omicron NanoTechnology). Impedance measurements (Metrohm AutoLab FRA32M) were performed to analyse the oxygen ion conductivity. The electrodes were made by applying a silver paste coating on both sides of the pellet to establish electrical contact, ensuring proper connectivity for the analysis. The temperature range for the analysis was 200–300 °C, with intervals of 25 °C with a heating rate of 5 °C/min between 0.1 Hz to 1 MHz frequency range.

VOC sensing

For the sensing study, the electrodes were symmetrically drawn on both edges of one side of the pellet. The study was carried out over a temperature range of 200 to 300 °C with an interval of 25 °C using a digital source meter (KEITHLEY, Model No. 2450, Specification: 200 V, 1A, 20W). A steady potential of 10 V was applied to the sample throughout the measurements.

Computational methods

The theoretically predicted electronic structures, including the calculated band structure, total and projected density of states (TDOS/PDOS), electron density as well as Bader charge analysis and electron localization were determined by density functional theory (DFT) based formalism. The details of computation may be found elsewhere28. The computation was performed under Atomistic Tool Kit (ATK) platform of Virtual Nanolab®. The supercells of CeO2 and Sm-doped CeO2 were built and calculations were performed on the strain relaxed optimized structures. The supercell of CeO2 was built from cubic unit cell with lattice constants a = b = c = 5.47 Å (mp-20194) with space group Fmm. The PDOS for all the cases were determined on the set of 4 × 4 × 4 optimized Monkhorst -Pack k-points. The density mesh cut-off energy was 750 eV, and the Fermi level was set at 0 eV in all calculations.

Result and discussion

Crystallographic Study

Figure 1 represents the Raman spectra of both pure and Sm-doped CeO2 samples. CeO2 crystallizes in an FCC structure (Fm-3 m space group), featuring one Raman-active phonon (T2g symmetry). This Raman-active phonon has one stretching vibration (F2g) mode typically appears around 461 cm-1, as observed in Fig. 1, where it is prominent between 460–465 cm-129. The F2g mode represents the symmetric vibration of the tetrahedrally coordinated oxygen ions at the unit cell. If bond length between the oxygen ion and cation get changed or any defect is present in the crystal, it influences the oscillation frequency and it reflected in the Raman spectrum30. As the Sm3⁺ concentration increased, a red shift and peak broadening were observed in the F2g mode, indicating alterations in the metal-anion bond vibration, which may be due to the substitution of Ce4+ ions with Sm3+19. Along with the F2g peak, a band is observed between 550 cm⁻1 and 600 cm-1, attributing to the presence of Vo, while the later arises due to the differences in ionic radii between Sm3⁺ and Ce4⁺19 The absence of characteristic Sm2O3 bands (around 375 cm⁻1) of 0-20SDC in Raman spectra indicates that no separate Sm2O3 phase was formed19 consistent with the result obtained in XRD, which is discussed in Section S-2 in Fig. S-2.1 of the Supporting Information. In the 30SDC sample, the characteristic oxide vibrational mode of Sm2O3 was detected at around 375 cm⁻1. The appearance of this distinct peak indicates the formation of a separate samarium oxide (Sm2O3) phase, rather than the creation of a uniform CeO2-Sm2O3 solid solution. This observation suggests partial segregation of Sm2O3 at higher doping levels, which hinders the complete lattice incorporation of Sm2O3 into the CeO2 fluorite structure.

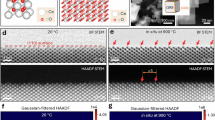

Figure 2a, d present the high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) images of pure ceria (0SDC) and 20SDC particles, with corresponding selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns in Fig. 2b, e respectively. The lattice fringes with an interplanar spacing of approximately 3.10 Å for 0SDC, and around 3.09 Å in 20SDC. All the measured fringes correspond to (111) plane and are consistent with the d-spacing values obtained from X-ray diffraction31. Additionally, Fig. 2c, f represent the elemental mapping and overall microstructure of 20SDC, as determined by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). The EDS analysis confirms the homogeneous distribution of Ce, Sm, and O in the sample. The carbon (C) signal originates from the usage of carbon tape during the experiment. The Panoramic view and grain size distribution analysis of 20SDC shown in section S-2 in Fig. S-2.2 of the Supporting Information.

(a) and (b) HRTEM image of the 0SDC powder calcined at 400 °C, along with the SAED pattern (scale bar is 1 nm and 5 nm for the inset). (c) EDX mapping for Ce, Sm, and O. (d) and (e) HRTEM image of the 20SDC powder calcined at 400 °C, along with the SAED pattern (scale bars are 2 nm and 5 nm for the insets). (f) EDX spectra of the 20SDC sample.

Defect analysis

Rare earth ions exhibit 4f–4f intra-configurational transitions, which is parity forbidden. Tetravalent cerium ions (Ce4⁺) possess an empty 4f configuration, shows a strong UV absorption due to the ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) transitions, where electrons move from O2- ligands to Ce4+ ions, making it a highly promising luminescent material32. In this study, the PL spectra of 0-30SDC samples have been taken at room temperature in ethanol from 265–485 nm range, which is shown in Fig. 3a. The peak corresponds to ethanol observed at 320 nm and LMCT transitions (O2- → Ce4+) in pure and doped ceria at 352 nm. Additionally, there are a few peaks observed at 366, 375, 395, and 420 nm. The asymmetric nature of these LMCT absorption bands can be associated with variations in Ce4+–O2- distances and the presence of Vo within the lattice, which result in LMCT transitions at different energy levels32,33,34,35.

In UV–Vis spectroscopy, a prominent absorption band was observed at around 331 nm in all the samples, as shown in Fig. 3b. The absorption spectra show a shift towards higher wavelength, which may be due to the incorporation of the Sm3+ ion, resulting in a change in electronic band structure36. The band gap was calculated using the Tauc plot, by fitting the absorption data to the direct transition equation, (αhν)2 = A(hν-Eg), as shown in Fig. 3c. It is determined by inducing the linear portion of the plot of (αhν)2 as a function of the photon energy hν. The band gap of pure ceria obtained is at 3.4 eV, which is observed to be reducing from 2.9 to 2.8 eV as Sm concentration increases from 10 to 20 mol%. However, at 30SDC, the band gap slightly increases to 3.0 eV. The decrease in band gap with increasing concentration of Sm3+ could be because of several important reasons37 such as doping with Sm3⁺ introduces partially filled 4f orbitals, which reduces the conduction band energy level38. Also, in order to maintain the charge balance, it generates Vo, resulting in an increase in the density of defect states. This Vo generates new defect states above the valence band, thereby creating localized electronic states and effectively narrowing the band gap, as illustrated in Fig. 3d.37,38 This facilitates the easy movement of electrons between the valence and conduction bands, resulting in the enhancement of ionic conductivity of SDC. At lower concentrations of Sm3+, these defect states reduce the band gap, however, at higher dopant concentrations, structural distortions and defect state density alters the electronic structure, leading to a slight increase in the band gap36.

The results obtained from UV–visible spectroscopy are consistent with the findings from photoluminescence studies, where both analyses indicate a clear correlation between Sm3+ concentration and the defect level37.

XPS investigation showed the presence of Ce 3d, Sm 3d, and O 1 s oxidation states39,40,41. A Gaussian shape fitting model was used for analysis and deconvolution of the peaks. Figure 4a represents the survey spectrum of 20SDC. It is observed that the peaks are shifted due to the presence of Ce3⁺, Ce4⁺, and Sm3⁺ ions, having different ionic radii may lead to the generation of strain42. Fig. 4d–f represent the Ce 3d spectrum analysis of 0SDC, 20SDC and 20SDC after sensing for 6 months. Ce 3d spectrum revealing two primary sets of peaks. The first set, corresponding to the Ce 3d5/2 level, consists of five distinct peaks labelled as v₀, v, v′, v′′, and v′′′. The second set, associated with the Ce 3d3/2 level, includes four peaks denoted as u₀, u, u′′, and u′′′43. The peaks labeled v₀, v′, u′, and uo correspond to Ce3+, while the peaks v, v ′′, v ′′′, u, u′′, and u′′′ correspond to Ce4+ binding energy44. In Fig. 4 (e), the Ce 3d spectrum exhibits noticeable binding energy shifts compared to pure ceria. The observed shifts in binding energy indicate that substitution alters the electronic environment of the ceria lattice39. XPS deconvolution revealed a Ce3+/Ce4+ ratio of 0.639 (39%/61%) for 0SDC, which increased to 1.35 (57.4%/42.5%) for 20SDC. This modest rise indicates that higher Vo formation in the doped sample, correlating with improved acetone sensing performance through increased reactive surface sites. The calculation has been shown in section S-3 of the Supporting Information. After six months of sensing operation, the Ce3+/Ce4+ ratio decreased to 0.748 (42.8%/57.2%), as shown in Fig. 4f. This slight reduction reflects a decrease in the number of Vo within the ceria lattice. Since Vo act as active sites for gas adsorption and charge transfer, their decline suggests a partial passivation or consumption of these sites during prolonged cycling. Importantly, the modest change in Ce3+ concentration (detected in XPS) indicates that the overall redox flexibility of the material is largely preserved, highlighting the structural stability of the doped ceria system. Similar trends have been reported in long-term studies of doped ceria, where Ce3+ fractions typically fall in the range of 35–50% after extended thermal or electrochemical aging (e.g., Sm, Gd, and Zr-doped CeO2 systems), compared to 45–60% in fresh samples45,46,47,48. The present results are therefore consistent with the literature, demonstrating that while prolonged operation reduces surface Vo, the fundamental Ce3+/Ce4+ framework remains intact. This stability is essential for sustaining baseline electronic properties, though a slight decrease in defect mediated activity may influence catalytic and sensing performance with time. Figure 4j, k reveals two distinct peaks in the Sm 3d region for 20SDC before and after sensing. These peaks correspond to the Sm3+ 3d5/2 and Sm3+ 3d3/2 levels. The successful replacement of Sm3+ into the CeO2 lattice is confirmed by measuring the peak positions, which correspond to values reported in the literature38. Similarly, Fig. 4g–i represents the XPS spectra of O 1 s in 0SDC, 20 SDC before and after sensing, where the two peaks corresponding to lattice oxygen (OL) and vacancy-related oxygen (Ov), from which one can analyse the presence of Vo. Lattice oxygen typically appears at a lower binding energy due to under-coordinated oxygen, while Vo are observed at a higher binding energy.49 Fig. 4h shows a distinct secondary peak of Ov, indicating the presence of Vo in 20SDC sample. The relative contribution of Vo is 73% in 20SDC, compared to 40% in 0SDC, confirming that Sm doping enhances defect formation in the ceria lattice. After six months of operation, the Vo contribution in 20SDC decreases to 30%, indicating a gradual reduction in vacancy concentration over the long term. This trend is consistent with the Ce 3d XPS analysis, where a decrease in the Ce3+/Ce4+ ratio was observed after aging, reflecting the direct correlation between the Ce3+ content and oxygen vacancy density in the lattice, the calculation of which has been shown in section S-3 in the Supporting Information. The shifting of the peaks and lattice oxygen in 20SDC sample confirm the presence of Vo40,42,50. The increased amount of Vo in doped ceria directly influences both the transducer and receptor sites of the sensor by providing a higher density of charge carriers and augmenting the number of available active sites for analyte adsorption14,16.

Further, the impedance analysis was done to confirm the presence of Vo. Fig. (S-3) in section S-4 of Supporting Information displays the typical Nyquist plot for all SDC samples measured at 300 °C, where lowest resistance is observed in 20SDC sample.

Sensing study

In this study, the impact of varying Vo concentrations, generated by doping Sm3+ in CeO2, on the sensing performance of SDC samples has been explored at different temperatures. Ohmic conductance was confirmed by performing I–V characteristic measurements, as shown in Fig. S-4 in section S-5 of Supporting Information. The sensing behavior and selectivity toward the analyte have been performed on all the doped ceria samples at 250–300 °C. These experiments were performed using a digital sourcemeter (Keithley) to ensure precise and reliable data acquisition.

Sensing mechanism

The sensing mechanism of the material is explained in Fig. 5. SDC acts as a p-type gas sensor, where the sensing mechanism primarily involves chemisorption followed by physisorption. Initially, oxy-ion-species from the surrounding air are chemisorbed onto the surface of the semiconductor, which alters its conductivity by taking electron and generates hole within the material. The adsorption of oxy-ion-species depends on temperature: O2- (< 300 °C), O- (100–300 °C), and O2- (> 100 °C)51.

The reducing gas interacts with the oxy-ion-species after being absorbed by the sensor surface. This interaction leads to the reduction of the oxy-ion-species, and the resulting reaction products are subsequently removed from the surface.

When acetone molecules interact with the SDC surface, the carbonyl group facilitates electron transfer to SDC, a process that is mediated by Vo. This electron transfer leads to the pairing of electrons with holes, resulting in a reduction in hole concentration, an increase in the hole accumulation layer (HAL), which causes a subsequent decrease in conductivity. The change in electrical resistance provides a measurable indication of the presence and concentration of acetone. During the sensing process, acetone molecules react with surface-adsorbed oxygen and produce carbon dioxide (CO2), which then desorbs from the sensor surface during the recovery phase and restore the sensor to its baseline state. The reactions of acetone with chemisorbed atomic oxygen are presented in Eq. 510,52.

While the interaction between adsorbed reducing gas and the chemisorbed oxygen species happens more slowly, oxygen and the reducing gas adsorb quickly. It is proposed that this reaction may be the rate-determining step in the response kinetics of the sensor. Furthermore, we hypothesize that once the reducing gas flow is halted and the sensor is purged with air, the desorption of the reaction products from the sensor surface takes place.

(0–30) SDC sensing for acetone

In this study, four samples (0-30SDC) were tested at 250–300 °C with 25 °C interval for their ability to detect acetone, focusing on response times, response values, and recovery times, which are shown in Fig. 6. The 20SDC sample exhibited the highest sensitivity among all, with a response value of ~ 38%, which may be due to its increased Vo content, thereby enhancing the interaction with acetone. The 10SDC sample exhibited moderate sensitivity and shorter response and recovery times. However, the lower Vo concentration may limit its overall effectiveness. The 0SDC and 30SDC samples demonstrate almost similar sensitivity and long recovery time. Overall, the 20SDC sample is the most effective one for acetone sensing, although its recovery time may restrict its use in applications needing quick measurement cycles.

Further studies were conducted using the 20SDC sample, focusing on its response to acetone under specific conditions shown in Fig. 6. Several experiments were performed at 300 °C to evaluate the effect of varying acetone concentrations, specifically at 1000 ppm, 500 ppm, 250 ppm, and 100 ppm, which are displayed in Table 1, which shows the sensing response, and both response and recovery times of 20SDC at different acetone concentrations.

Reproducibility study

Fig. S-6 in section S-6.1 of the Supporting Information highlights the sensing transients obtained from three different pellets for each material. SDC is valued for its high oxygen ion conductivity and stable redox properties. In sensor applications, reproducibility is a crucial parameter, as it reflects the consistency of performance across pellets and repeated measurements. Across all SDC doping levels, replicate pellets showed only minor variations in response, response time, and recovery time, with standard deviations of ± 0.32 and coefficients of variation typically below 1%. All statistical parameters are listed in Table 2, which were obtained from the results in section S-6.1 of the Supporting Information. Low standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variation (CV %) values indicate stable and consistent sensing behaviour. The narrow statistical spread confirms reliable performance during repeated measurements in the samples.

Cross-selectivity study

The selectivity of the pure and doped ceria samples towards various analytes, are shown in Fig. 7. The analytes tested included acetone, formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, methanol, ethanol, and n-butanol. This evaluation was conducted to determine the responsiveness to each analyte material, providing insight into its selectivity profile. The results revealed that acetone exhibited the highest selectivity among the tested analytes, with a response value of 21.2% for 0SDC (Fig. 7a–b) and 38% for 20SDC. This finding is illustrated in Fig. 7c, which displays the sensing response for each analyte. Further, Fig. 7a–d highlights the comparative response values, which clearly show the superior selectivity of acetone. Also, there was no significant change in the sensing response towards different analytes after doping, suggesting that the doping process did not influence the selectivity of the material.

Repeatability study

The repeatability of the 20SDC sensor was evaluated by subjecting it to multiple acetone sensing cycles under identical conditions. The response and recovery profiles across 20 repeated cycles demonstrated negligible variation in baseline current, response magnitude, and dynamic times as shown in Fig. 7f. The overlapping nature of the cycles confirms the excellent repeatability of the material, indicating that the sensing mechanism is stable and not degraded by repeated exposure.

Stability study

Figure 7e shows the stability study of 20SDC. The long-term stability of the 20SDC sensor was evaluated over six months under identical operating conditions. The response magnitude and kinetic parameters (response/recovery times) remained nearly unchanged, with only minor deviations. The calculated drift in response, from 38.3% at day 1 to 34.5% at six months, corresponds to ~ 9.9% drift over the testing period, which remains within acceptable limits for practical sensing applications mentioned in Table 3. These results confirm that the material retains both structural and functional integrity over extended use, underscoring its potential as a robust candidate for reliable long-term sensor operation.

The repeatability of the 20SDC sensor was evaluated by subjecting it to multiple acetone sensing cycles under identical conditions shown in Fig. 7h. The response and recovery profiles across 20 repeated cycles demonstrated a negligible variation in baseline current, response magnitude, and dynamic times. The overlapping nature of the cycles confirms the excellent repeatability of the material, indicating that the material is stable and not degraded by repeated exposure. Furthermore, the stability of the structure after six months was confirmed by the characterizing the sample pellets using XRD, SEM, and XPS. As shown in Fig. S-10 (XRD(d) and SEM(a-b)) in the Supporting Information and Fig. 4c, f, i, k (XPS), no significant structural degradation was observed, which indicates that the doped ceria lattice remains stable under prolonged sensing operation.

Humidity study

To further evaluate the influence of humidity on its acetone sensing behavior, conductance transients were measured under dry and humid conditions, as presented in Fig S-5(c) of the Supporting Information. The humidity level inside the sensing chamber was controlled by placing saturated NaCl salt solutions and the relative humidity was monitored using a commercial humidity sensor. The results reveal that the background humidity exerts only a minor effect on the acetone sensing response of the 20SDC sensor.

Table 4 shows a comparative analysis of the sensor data reported in this study with other pellet-type acetone sensors, which reveals that doped ceria pellets exhibit robust and reproducible performance characteristics, with mean response, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation reflecting excellent sample-to-sample consistency and sensitivity. When benchmarked against peer-referenced sensors such as CeO2 nanopowder, Ce-doped MgFe2O4, Co3O4, and BiFeO3/GO composites, the statistical parameters and operational metrics of the synthesized ceria-based sensors are comparable, confirming their technological competitiveness. The response times achieved are practical for VOC detection, and the stability of the baseline current under repeated cycles further supports the reliability of the material. Collectively, these results demonstrate that defect engineering and optimized doping strategies in ceria pellets deliver sensitivity, repeatability, and long-term stability aligned with the standards set in contemporary metal oxide sensor research.

Kinetic study

We propose that the mechanism observed in SDC is driven by the reaction pathways between the chemisorbed oxygen species and reducing gas Agas, resulting in the formation of reaction product AOad. Fig. S-7 of the Supporting Information presents an energy diagram that schematically depicts the proposed reaction pathways. The Langmuir–Hinshelwood surface reaction mechanism, which underlies Fig. S-7 depicts that the reactants are initially adsorbed onto the sensor surface, followed by collision to produce the reaction products58. Further calculations are presented in Section S-7 of the Supporting Information.

The reaction product AOad shows the maximum sensor response (Rmax) when all active sites (Sθ) are occupied. The transient response of the sensor, R(t), or its response at a specific time (t) can be calculated by using the following equation:58

where k is rate constant and Cg is concentration of analyte.

The variation of the estimated response time (τ) with acetone concentration using an SDC sensor at various temperatures (200–300 °C) has been illustrated in Fig. 8a–d and Fig. S-5 in Supporting Information and the fitted parameters are mentioned in Table 5 and Table S-1 in Supporting Information. All additional calculations are discussed in Section S-7 of the Supporting Information. The fitted graph values (Table S-2 in Supporting Information and Fig. 8b–f) clearly indicate that with increasing temperature (T), the sensor response (R) approaches its maximum value (Rmax) at the corresponding time (tmax).

The resistance transients observed in SDC sensing materials can be explained by the Langmuir–Hinshelwood reaction model. According to this model, the gas sensing response is influenced by several factors such as the test gas concentration, the measurement time, and the operating temperature of the sensor. The reaction between reducing gases and chemisorbed oxygen primarily takes place during the response cycle. The characteristic time constants for these steps exhibit a temperature dependent behaviour, as described by the relationship in Eq. (9):58

where A is pre-exponential factor, Ea is activation energy, R is universal gas constant, T is absolute temperature (in Kelvin). Taking the natural logarithm of both sides yields Eq. (10):

From this equation, activation energies (Ea) for the oxidation of acetone can be obtained from the slope of the linear plots of ln(τ) versus 1/T. The corresponding values for 0–30 SDC are presented in Table 6, where it is observed that 20SDC exhibits a higher activation energy52. A detailed explanation of the kinetic study is provided in Section S-7 and fitted parameters are mentioned in Table S-2 and Fig. S-8 in the Supporting Information.

Activation energy is an essential parameter for initiating the chemical processes that enables VOC sensors to operate effectively has been shown in Fig. 9. A higher activation energy threshold ensures that only molecules with sufficient energy can trigger a response, allowing the sensor to better distinguish between different analytes. This reduces background noise and false signals, resulting into a more accurate readings59,60. Sensors with lower activation energy exhibit both faster response and recovery times. However, the rapid recovery may limit the duration of elevated response of the sensor, which potentially reduces the overall signal amplitude61,62,63.

Density functional interpretation of the sensing properties

Figure 10 represents the results of the calculated electronic structures of ceria and Sm-doped ceria using density functional theory (DFT) within the linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO). The exchange correlation used a GGA:PBE + U type functional with onsite Hubbard U potentials, for O-2p as U(p) = 4 eV and Ce-4f or Sm-4f as U(f) = 4 eV64,65. Fig. 10a shows that the CeO2 has an indirect band-gap nearly ~ 1 eV, which is smaller as compared to the experimentally observed band-gap 2.4–3.2 eV. This underestimation is obvious in the DFT calculation, due to the exchange correlation functionals used in the calculation are good for calculations such as, total energy or structural properties but less efficient in calculating quasiparticle excitation energies, such as band-gap. Moreover, the existence of plenty of delocalized electrons from the upper d- and f- orbitals lower the conduction band energies in the form of tail states as shown in the subsequent PDOS. However, the calculated band structure and PDOS shows that, the 2p-5d gap is larger than that of 2p-4f gap, that agrees well with the past report66 In case of Sm-doped ceria similar band structure can be calculated (not shown here) with additional contribution from Sm-4f delocalized electronic states. Figure 10b shows the PDOS of the undoped ceria supercell. It shows that, the top of the valence band is predominantly populated by O-2p orbitals whereas the deep valence band is contributed largely by Ce-5d orbitals. The bottom of the conduction band has Ce-4f orbital projection. Such orbital organization obviously represents that CeO2 electronic properties must be governed by the relative position of the Fermi level (dashed line) to the bottom of conduction band and it can be modulated by doping. Figure 10c shows the normalized PDOS of all relevant orbital projections in undoped (Fig. 10c-1) and Sm-doped ceria (Fig. 10(c-2, 3 & 4) corresponding to x = 0.093, 0.156, and 0.218 in SmxCe1-xO2, respectively). Upon introduction of Sm in the CeO2 lattice, Sm-4f orbital projection appears within the existing band gap as dense tail states. The Sm-4f orbitals also strongly hybridised with Ce-4f and -5d orbitals in the conduction band. This eventually shifts the Fermi level upward and the system’s electronic properties enhance. The electronic transfer from ceria valence band into the conduction band that improves the sensing behaviour based on the electronic exchange is further corroborated from a Bader charge analysis as presented in the lower panel of Fig. 10d. The average Bader charge on the Ce-sites is found to increase from 0.45e to 0.57e by Sm-doping, which represents its reduction. On the other hand, a net decrease of charges on O-sites is found from 7.8e to 7.6e, whereas no change in Sm-site charges is observed. This indicates that, the Sm-doping would largely facilitate transfer of electrons from O-2p states into the Ce-4f states in the valence band through upshifted Fermi level. The independent Sm-5f electron localization is represented in the electron localization function (ELF) heat map as shown in Fig. 10e. The ELF shows that there is no direct covalent bond formation in the system, however, the delocalized electrons from the ceria were largely responsible for creating oxygen vacancies that eventually controls the sensing properties as discussed.

Calculated electronic band structure, projected density of states (PDOS), Bader charges and electron localization of CeO2 and Sm-doped CeO2 supercells by PBE + U with U(4f) = 4 eV and U(2p) = 4 eV. (a) Band structure of pure CeO2, (b) PDOS of pure CeO2, (c) normalised PDOS of pure (c-1) and Sm-doped ceria (c-2, 3 & 4 corresponding to x = 0.093, 0.156, and 0.218 in SmxCe1-xO2, respectively), (d) Bader charges on average of all Ce, O and Sm sites, (e) Electron localization function (ELF) heatmap for undoped and doped ceria.

Conclusion

This study highlights the critical role of Vo in improving the gas sensing performance of metal oxides. Crystallinity was confirmed through XRD, Raman, and HR-TEM analyses, indicating that the material is in cubic phase with homogeneous elemental distribution. PL analysis confirms the generation of new defect energy levels in doped ceria, which are directly associated with the creation of oxygen vacancies. These defect states correlate with the UV–Vis results, where doping induces a reduction in the optical bandgap from 3.4 eV in 0SDC to 2.7 eV in 20SDC, as determined from Tauc plots. The slight increase in bandgap observed beyond 20SDC may be attributed to structural distortion and defect saturation at higher dopant concentrations. XPS analysis confirmed the coexistence of Ce4+, Ce3+, and Sm3+ oxidation states together with Vo, validating the defect‐rich electronic structure of the doped ceria system. Impedance studies at 300 °C revealed that the grain boundary resistance is reduced on increasing the dopant concentration. Among all samples, 20SDC showed the lowest resistance and highest ionic conductivity, indicating superior performance. Gas sensing studies, performed at 300 ℃, identifies acetone as the most selective analyte. 20SDC exhibits better sensitivity and response among all other samples. Kinetic studies revealed a notable increment in sensor performance as temperature is increased from 250 to 300 °C. The 20SDC sample also exhibits a highest activation energy among all the samples, which is responsible for the enhancement in the selectivity of the sensor. Collectively, these findings suggest that the 20SDC sample, with its highest oxygen vacancy concentration, exhibits superior sensing performance, as Vₒ simultaneously act as an adsorption centers for gas molecules and facilitates charge transfer through the increasing charge carrier.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Jalal, A. H. et al. Prospects and challenges of volatile organic compound sensors in human healthcare. ACS Sens. 3, 1246–1263 (2018).

Khatib, M. & Haick, H. Sensors for volatile organic compounds. ACS Nano 16, 7080–7115 (2022).

Kaushik, A. et al. Organic-inorganic hybrid nanocomposite-based gas sensors for environmental monitoring. Chem. Rev. 115, 4571–4606 (2015).

Zhang, J., Liu, X., Neri, G. & Pinna, N. Nanostructured materials for room-temperature gas sensors. Adv. Mater. 28, 795–831 (2016).

Fergus, J. W. Doping and defect association in oxides for use in oxygen sensors. J. Mater. Sci. 38, 4259–4270 (2003).

Lodahl, P. et al. Controlling the dynamics of spontaneous emission from quantum dots by photonic crystals. Nature 430, 654–657 (2004).

Miller, D. R., Akbar, S. A. & Morris, P. A. Nanoscale metal oxide-based heterojunctions for gas sensing: A review. Sens. Actuators B Chem 204, 250–272 (2014).

Goel, N., Kunal, K., Kushwaha, A. & Kumar, M. Metal oxide semiconductors for gas sensing. Eng. Rep. 5, e12604 (2023).

Berwal, P. et al. Hybrid metal oxide nanocomposites for gas-sensing applications: A review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 62, 14835–14852 (2023).

Shah, V., Bhaliya, J., Patel, G. M. & Joshi, P. Room-temperature chemiresistive gas sensing of SnO2 nanowires: A review. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym Mater. 32, 741–772 (2022).

Al-Hashem, M., Akbar, S. & Morris, P. Role of oxygen vacancies in nanostructured metal-oxide gas sensors: A review. Sens. Actuators B Chem 301, 126845 (2019).

Yu, W. et al. Improving gas sensing performance by oxygen vacancies in sub-stoichiometric WO3−x. RSC Adv. 9, 7723–7728 (2019).

Yamazoe, N. & Shimanoe, K. New perspectives of gas sensor technology. Sens. Actuators B Chem 138, 100–107 (2009).

Gunawan, C. et al. Oxygen-vacancy engineering of cerium-oxide nanoparticles for antioxidant activity. ACS Omega 4, 9473–9479 (2019).

Yu, K., Lou, L. L., Liu, S. & Zhou, W. Asymmetric oxygen vacancies: the intrinsic redox active sites in metal oxide catalysts. Adv. Sci. 7, 1901970 (2020).

Lin, T., Lv, X., Hu, Z., Xu, A. & Feng, C. Semiconductor metal oxides as chemoresistive sensors for detecting volatile organic compounds. Sensors 19, 233 (2019).

Chen, K. H. et al. Control of oxygen vacancies of 2D-InOx fabricated by liquid metal printing via temperature modulation. J. Phys. Chem. C 128, 5355–5365 (2024).

Yang, X. et al. Research progress on the construction of oxygen vacancy defects and application in photocatalytic oxidation of elemental mercury. Fuel 355, 129440 (2024).

Vinchhi, P., Patel, R., Mukhopadhyay, I., Ray, A. & Pati, R. Effect of doping concentration on grain boundary conductivity of samaria doped ceria composites. J. Electrochem. Soc. 168, 124515 (2021).

Wang, Z., Lin, R., Huo, Y., Li, H. & Wang, L. Formation, detection, and function of oxygen vacancy in metal oxides for solar energy conversion. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2109503 (2022).

Paul, M. et al. Effect of temperature on polaronic transport in CeO2 thin-film. J. Chem. Phys. 160, (2024).

Paul, M., Karmakar, S., Sharma, J., Bhunia, S. & Chakraborty, S. Correlating the low-temperature photoluminescence with electron transport properties in cerium oxide thin film. J. Chem. Phys. 162, (2025).

Felix, S., Chakkravarthy, R. B. P. & Grace, A. N. Microwave assisted synthesis of copper oxide and its application in electrochemical sensing. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 73, 012115 (2015).

Chen, Q. et al. Microwave-assisted synthesis of a defect-rich CuO electrode for selective electrochemical CO2 reduction to C2+ products. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 12, 15134–15146 (2024).

Ahmed, M. A., Mahmoud, S. A. & Mohamed, A. A. Interfacially engineered metal oxide nanocomposites for enhanced photocatalytic degradation of pollutants and energy applications. RSC Adv. 15, 15561–15603 (2025).

Freiberg, A. T. S., Qian, S., Wandt, J., Gasteiger, H. A. & Crumlin, E. J. Surface oxygen depletion of layered transition metal oxides in Li-Ion batteries studied by operando ambient pressure X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 4743 (2023).

Gaálová, J. & Topka, P. Gold and ceria as catalysts for VOC abatement: A review. Catalysts 11, 789 (2021).

Shaikh, N. et al. Doping induced mixed polytypic interfaces of MoS2 for superior electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 649, 159195 (2024).

Chen, S. Y., Chen, R. J., Lee, W., Dong, C. L. & Gloter, A. Spectromicroscopic evidence of interstitial and substitutional dopants in association with oxygen vacancies in Sm-doped ceria nanoparticles. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 3274–3281 (2014).

Guo, M., Lu, J., Wu, Y., Wang, Y. & Luo, M. UV and visible Raman studies of oxygen vacancies in rare-earth-doped ceria. Langmuir 27, 3872–3877 (2011).

Ahmad, S. I., Mohammed, T., Bahafi, A. & Suresh, M. B. Effect of Mg doping and sintering temperature on structural and morphological properties of samarium-doped ceria for IT-SOFC electrolyte. Appl. Nanosci. 7, 243–252 (2017).

Souza, E. C. C., Brito, H. F. & Muccillo, E. N. S. Optical and electrical characterization of samaria-doped ceria. J. Alloys Compd. 491, 460–464 (2010).

Dorenbos, P. Exchange and crystal field effects on the 4fn-15d levels of Tb3+. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 15, 6249–6268 (2003).

Maslakov, K. I. et al. The electronic structure and the nature of the chemical bond in CeO2. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 16167–16175 (2018).

Vazirov, R. A. et al. Physicochemical characterization and antioxidant properties of cerium oxide nanoparticles. in Journal of Physics: Conference Series vol. 1115 (Institute of Physics Publishing, 2018).

Anwar, M. S. et al. Structural and optical study of samarium doped cerium oxide thin films prepared by electron beam evaporation. J. Alloys Compd. 509, 4525–4529 (2011).

Abdulwahab, K. O., Khan, M. M. & Jennings, J. R. Doped ceria nanomaterials: Preparation, properties, and uses. ACS Omega 8, 30802–30823 (2023).

Schmitt, R. et al. A review of defect structure and chemistry in ceria and its solid solutions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 554–592 (2020).

Kosinski, M. R., Vizcaíno, A. J., Gómez-Sainero, L. M., Carrero, A. & Baker, R. T. Methanol reforming by nanostructured Pd/Sm-doped ceria catalysts. Appl. Catal. B 286, 119935 (2021).

Wang, J., Mueller, D. N. & Crumlin, E. J. Recommended strategies for quantifying oxygen vacancies with X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. J. Eur Ceram Soc 44, 116709 (2024).

Hu, Q. et al. Unveiling the synergistic effects of hydrogen annealing on CeO2 nanofibers for highly sensitive acetone gas detection: Role of Ce3+ ions and oxygen vacancies. Appl. Surf. Sci. 640, 158411 (2023).

Idriss, H. On the wrong assignment of the XPS O1s signal at 531–532 eV attributed to oxygen vacancies in photo- and electro-catalysts for water splitting and other materials applications. Surf. Sci. 712, 121894 (2021).

Kuntaiah, K., Sudarsanam, P., Reddy, B. M. & Vinu, A. Nanocrystalline Ce1-xSmxO2-δ (x = 0.4) solid solutions: Structural characterization versus CO oxidation. RSC Adv. 3, 7953–7962 (2013).

Basina, G. et al. Ultrasmall metal-doped CeO2 nanoparticles for low-temperature CO oxidation. ACS Appl. Nano. Mater. 3, 10805–10813 (2020).

Li, Y., Bian, X., Dong, H., Chang, H. & Wu, W. Enhanced light response performance of ceria-based composites with rich oxygen vacancy. Molecules 30, 127 (2024).

Baek, J. W. et al. Cobalt-doped ceria sensitizer effects on metal oxide nanofibers: Heightened surface reactivity for high-performing chemiresistive sensors. ACS Nano 18, 10 (2024).

Xu, N. et al. Unraveling the formation of oxygen vacancies on the surface of transition metal-doped ceria utilizing artificial intelligence. Nanoscale 16, 9853–9860 (2024).

Madaan, V., Bhankar, V., Singh, P., Mohan, B. & Kumar, K. Oxygen vacancies generation in Ceria via Eu(III)-doping for accelerated charge separation UV-driven photodegradation of hazardous Rose Bengal dye. Opt. Mater. (Amst) 166, 117213 (2025).

Pascu, R. V. et al. Samarium doped cerium oxide thin films deposited by pulsed laser deposition. Appl. Surf. Sci. 606, 154994 (2022).

Zhu, Y. et al. Effect of oxygen vacancy and highly dispersed MnOx on soot combustion in cerium manganese catalyst. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–13 (2023).

Gurlo, A. Interplay between O2 and SnO2: Oxygen ionosorption and spectroscopic evidence for adsorbed oxygen. ChemPhysChem 7, 2041–2052 (2006).

Karmakar, M., Mondal, B., Pal, M. & Mukherjee, K. Acetone and ethanol sensing of barium hexaferrite particles: A case study considering the possibilities of non-conventional hexaferrite sensor. Sens Actuators B Chem 190, 627–633 (2014).

Patil, J. Y., Nadargi, D. Y., Mulla, I. S. & Suryavanshi, S. S. Cerium doped MgFe2O4 nanocomposites: Highly sensitive and fast response-recoverable acetone gas sensor. Heliyon 5, e01489 (2019).

Khodadadi, A., Mohajerzadeh, S. S., Mortazavi, Y. & Miri, A. M. Cerium oxide/SnO2-based semiconductor gas sensors with improved sensitivity to CO. Sens. Actuators B Chem 80, 267–271 (2001).

Behera, B. & Chandra, S. An innovative gas sensor incorporating ZnO–CuO nanoflakes in planar MEMS technology. Sens Actuators B Chem 229, 414–424 (2016).

Choi, Y. M. et al. Ultrasensitive detection of VOCs using a high-resolution CuO/Cu2O/Ag nanopattern sensor. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1808319 (2019).

Sinha, M., Mahapatra, R., Mondal, M. K., Krishnamurthy, S. & Ghosh, R. Fast response and low temperature sensing of acetone and ethanol using Al-doped ZnO microrods. Physica E Low Dimens Syst. Nanostruct. 118, 113868 (2020).

Mukherjee, K., Gaur, A. P. S. & Majumder, S. B. Investigations on irreversible- and reversible-type gas sensing for ZnO and Mg0.5Zn0.5Fe2O4 chemi-resistive sensors. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 45, 505306 (2012).

Zhao, W. J., Ding, K. L., Chen, Y. S., Xie, F. Y. & Xu, D. Optimized low frequency temperature modulation for improving the selectivity and linearity of SnO2 gas sensor. IEEE Sens J 20, 10433–10443 (2020).

Xu, F., Zhou, C. & Ho, H. P. A rule for operation temperature selection of a conductometric VOC gas sensor based on ZnO nanotetrapods. J. Alloys Compd. 858, 158294 (2021).

Meng, F. J., Xin, R. F. & Li, S. X. Metal oxide heterostructures for improving gas sensing properties: A review. Materials 16, 263 (2022).

Xu, F. & Ho, H. P. Light-activated metal oxide gas sensors: A review. Micromachines 8, 333 (2017).

Fujimoto, A. & Ohtani, T. Effects of activation energy on transient response of semiconductor gas sensor. Electron. Commun. Jpn. 96, 11–16 (2013).

Vanpoucke, D. E. P., Bultinck, P., Cottenier, S., Van Speybroeck, V. & Van Driessche, I. Aliovalent doping of CeO2: DFT study of oxidation state and vacancy effects. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2, 13723–13737 (2014).

Huang, B., Gillen, R. & Robertson, J. Study of CeO2 and its native defects by density functional theory with repulsive potential. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 24248–24256 (2014).

Zhang, X. et al. Toward a consistent prediction of defect chemistry in CeO2. Chem. Mater. 35, 207–227 (2023).

Acknowledgements

RM and RP are thankful to Solar Research and Development Centre (SRDC), Pandit Deendayal Energy University for providing experimental and computation facilities. All authors are also thankful to Materials Research Center, MNIT Jaipur for providing the XPS facility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.M.: Methodology, acquisition of data, interpretation and drafting the manuscript, S.P.: Data collection, Validation, Writing—review & editing, P.V.: Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing—review & editing, M.K.: Methodology, Writing—review & editing, N.T.: Data curation Formal analysis, Software, Writing—review and editing, A.R.: Validation and interpretation of EIS data, Validation and interpretation of DFT data, K.M.: Conceptualization, validation, writing, reviewing and editing, R.P.: Conceptualization, validation, writing, interpretation of data, reviewing, editing, and supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mistry, R., Paine, S., Vinchhi, P. et al. Doping induced enhancement for acetone sensing in ceria. Sci Rep 16, 2462 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32242-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32242-0