Abstract

Electrocardiograms (ECGs) are widely used for cardiac monitoring but are often affected by noise that degrades signal quality. Conventional preprocessing applies the same filters regardless of noise level, which can distort clean segments. We introduce a noise-presence framework that identifies whether noise is present, determines its type and then applies filtering suited to the specific contamination. This approach aims to reduce unnecessary distortion and preserve clinically important features. We evaluate the framework by measuring changes in QT and QRS intervals under noise-agnostic, noise-presence and noise-profile filtering. We also examine how sampling frequency influences noise detection and classification using kernel density estimation (KDE) and find that 500 Hz offers the best performance. A hierarchical Adaboost model outperforms support vector machine (SVM), random forest (RF), and ExtraTree classifiers, reaching \(99.82\%\) accuracy in noise detection and \(97.15\%\) in noise classification across seven datasets. Noise-profile filtering achieves the smallest mean QT difference at 2.50 ms compared with noise-presence at \(-16.37\) ms and noise-agnostic filtering at \(-38.23\) ms. QRS differences improve from \(-10.33\) ms with noise-agnostic filtering to \(-2.43\) ms with noise-presence and 4.28 ms with noise-profile filtering. The results show that adapting the filtering strategy to noise presence and type offers clear advantages in preserving clinical ECG parameters, which supports more reliable interval measurements in diagnostic settings. The main limitation is that the model is trained with synthetic noise, which may not capture the full range of real-world artefacts. This limitation remains, but the framework is still suitable for portable ECG systems and can be extended to other physiological signals by retraining on data from the target modality. The results indicate that adapting the filtering strategy to noise presence and type provides clear benefits in preserving clinical ECG parameters, supporting more reliable interval measurements in diagnostic settings. While the model was trained using synthetic noise, which may not fully represent all real-world artefacts, this does not diminish its practical applicability. The framework remains well-suited for portable ECG systems and can be extended to other physiological signals by retraining on data from the target modality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electrocardiogram (ECG) signals are widely used for monitoring heart health and detecting cardiovascular abnormalities. The increasing availability of lightweight, IoT-enabled ECG monitoring devices allows for remote and continuous signal acquisition. However, ECG signals collected from such devices are often corrupted by various noise sources, including baseline wandering, motion artifacts, power-line interference, and muscle artifacts. Daily activities such as walking, running, or sleeping can further distort signals, reducing the reliability of downstream diagnostic or decision-making systems.

Existing ECG denoising methods typically rely on predefined filters with fixed parameters. For example, stochastic computing–based digital filters1 focus on hardware efficiency rather than preserving signal morphology, while data suppression frameworks in wireless sensor networks2 aim to reduce communication overhead but do not address noise-specific filtering. Real-time IIR filter implementations on microcontrollers3 remove specific noise types but apply filters indiscriminately, potentially distorting clean signals. Sparse signal decomposition methods have been used to remove muscle artifacts4 and baseline wander5, but they are optimised for single noise types and cannot adapt to the diverse noise encountered in real-world conditions. In all these approaches, the key limitation is that filters are applied blindly, without first assessing whether noise is present or identifying its type, which can compromise signal integrity and the accuracy of clinical biomarkers.

Block diagram of the proposed framework for knowledge-based ECG noise filtering using a machine learning (ML) model and the evaluation of possible filtering options. The raw ECG signal is passed to the feature extraction module, and noise-agnostic filtering is applied simultaneously. A ML model is used for detecting noise based on extracted features, and then noisy segments are simultaneously filtered (noise-presence filtering) and passed to the noise classification module. The ML-based noise classification module classifies ECG segments and feeds them into the noise-profile filtering module. Finally, the benefit of the proposed framework is evaluated by extracting biomarkers (QRS complex and Q-T interval) after three different filterings: (i) noise-agnostic filtering, (ii) noise-presence filtering, and (iii) noise type-based filtering.

To address these limitations, we propose a knowledge-based ECG noise detection and classification framework as shown in Fig. 1. Our method first detects whether noise is present and then classifies its type using supervised Machine learning (ML), including Random forest (RF), Support vector machine (SVM), ExtraTree, and AdaBoost. By identifying the specific noise profile, the framework selects the most appropriate filtering strategy from three options: noise-agnostic, noise-presence, and noise-profile filtering. This adaptive approach ensures that clean signals are preserved while noisy signals are effectively denoised, minimising distortion of critical ECG features.

The contributions of this study are summarised as follows:

-

Propose a knowledge-based ECG noise detection and classification framework that identifies the presence and type of noise before applying traditional filters, ensuring that clean signals are not unnecessarily distorted and improving the quality of clinical biomarkers in cardiovascular disease detection.

-

Investigate the scalability of the noise detection and classification framework across multicentric settings, considering different sampling frequencies and acquisition conditions.

-

Evaluate the generalisation capability of the framework using large and diverse publicly available ECG datasets to assess robustness and adaptability across varying data sources and noise conditions.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. Section 6.1.2 describes the Performance of ECG noise detection for unified sampling frequency across the datasets. Section “Experimental results” illustrates the experimental results and “Discussion” presents the discussion on experimental results and finally, “Conclusion” concludes the paper.

Related work

This section provides a critical review of the state-of-the-art methodologies in ECG noise analysis, focusing on their respective advantages and inherent limitations. The review is structured into two main subsections: existing approaches for ECG noise detection (“Existing ECG noise detection techniques”, and methods developed for ECG noise classification (“Existing ECG noise classification techniques”).

Existing ECG noise detection techniques

In recent years, ECG noise detection has drawn tremendous attention in the healthcare system. In the early days of noise detection work, researchers were focused on ECG amplitude to detect noise-free (less than 15 mV or more than 0.2 mV) and noisy ECG (more than 15 mV or less than 0.2 mV) signals6,7, and had tested their proposed methods on the Computing in Cardiology (CINC) 2011 dataset with accuracy between 90.80 to \(98.07\%\). However, the amplitude of an ECG signal depends on the data acquisition devices. Therefore, the amplitude-based ECG noise detection method is unreliable and difficult to generalise over diverse datasets where the recorded signal amplitude ranges differ. To overcome the drawback of amplitude-based ECG noise detection, researchers introduced the use of ECG-derived markers (R-R intervals) for detecting noise in the ECG signal8,9. In this approach, after measuring different biomarkers, a predefined threshold is used for classifying ECG signals as noisy and noise-free. Orphanidou et al.9 detected noisy signals from average heart rate (HR) using the Hamilton and Tompkins algorithm, and if the average HR is within \(40-180\) BPM, then it is considered a noise-free signal; otherwise noisy. Similar to8, Orphanidou et al.9 used ECG signals from CINC 2011, and reported very high specificity (\(97.00\%\)) and sensitivity (\(93.00\%\)). Although these studies showed high accuracy in detecting noisy ECG signals, the accuracy of the R-peak detection algorithm directly affects the performance of these noise detection algorithms. In addition, if we just compare studies8,10 and9, it is obvious that two different BPM threshold values were used for the same dataset (CINC 2011). Thus, it is obvious that this kind of empirical threshold selection can hinder the generalisation of such a method. A decomposition-based ECG noise detection technique (Complementary ensemble empirical mode decomposition (CEEMD), wavelet) has been published in several articles11,12,13. Satija et al.11 divided ECG data into various intrinsic mode functions using the CEEMD approach, then applied predefined threshold values to each decomposed level to distinguish between noisy and noise-free ECG signals. They claimed \(98.90\%\) accuracy for detecting ECG noise. Mohahmad abdelazez et al.12 proposed an SNR-based signal quality assessment for ECG signal and achieved \(90\%\) accuracy. However, SNR-based SQI often cannot detect the good and poor quality of the ECG signal mentioned in14. The discrete wavelet transformation (DWT) is one of the popular decomposition methods, where noise intensity is divided into low-frequency and high-frequency bands. Similar to11, the authors applied thresholds in each sub-band for noise detection. This method was tested on multiple datasets (MIT-BIH arrhythmia database, CINC 2011, and real-time recorded ECG signals) and achieved \(99.49\%\) accuracy. Although these methods showed high accuracy (\(>98\%\)), the use of fixed threshold values limits their usability on diverse datasets. Another limitation of decomposition-based methods is determining the number of decomposition levels since it depends on the data acquisition characteristics15. To address those limitations, researchers have also been exploring the use of ML models for noise detection in ECG signals. The most important benefit of using ML is that this approach does not require any predefined threshold values for detecting noise. There are several studies regarding ECG noise detection using SVM and linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) models with an accuracy range between 88.07 to 96.79, sensitivity \(97.47\%\) and specificity \(96.67\%\)16,17. Although existing ECG detection performance is higher, some key points are missing, which are required to design a complete and generalised framework. Diverse dataset evaluation is necessary for model generalisation and the impact of different ECG sources with different sampling frequencies. In addition, it is worth justifying the necessity of ECG noise detection and classification in clinical decision-making systems, which is missing in existing studies.

Based on the literature, it is evident that a ML based approach is the future of ECG noise detection. Although there are many research papers supporting this direction, multiple unresolved questions about designing a generalised model (applicable to diverse datasets) need to be addressed. For example, when we are considering multiple independent datasets, there will be variations in the data-collecting process, which includes instruments, environment as well as sampling frequency. Since the classical ML model uses extracted features, in some cases, sampling frequency can affect the quality of those features. Therefore, in this study, we aim to study the impact of sampling frequency on the developed noise detection framework. In addition, although there is a general perception that ECG noise detection is beneficial, to date, no study has quantified such a benefit with respect to commonly used biomarkers. In this study, we quantify the benefit of noise detection using two biomarkers, the QT interval and the QRS complex. Finally, we have explored the ensemble classifier family in this study, since this was never explored in ECG noise detection, and based on the previous study, it can be summarised that no single model (SVM or LSTM) are adequate to provide a clear generalised performance.

Existing ECG noise classification techniques

There are only a few studies about ECG noise classification compared to detection, which may have contributed to the challenge of proving the benefits of ECG noise classification. Satija et al.11 proposed a CEEMD-based ECG noise classification model based on the specific threshold, such as baseline wander noise when the number of zero-crossings is less than 10, and the power line interference when the R-R interval is more than 300 ms or less than 50 ms. They created their dataset by mixing noise with a clean ECG signal for creating ground truth, and their accuracy rate is \(97.38\%\), and the sensitivity rate is \(98.93\%\). This threshold-based classification depends on specific experimental datasets, and changing them requires selecting another threshold. Thus, it is challenging to build a generic model using this approach. Satija et al.18 also proposed another rule-based classification model based on wavelet decomposition. Model dependency on specific threshold values and decomposition depth hinders the model’s generalisation capabilities. In17, the authors have proposed a Multi-class (SVM) MSVM-based noise classifier for MA, PLI and EMG noise classification and achieved \(84.35\%\) accuracy for private datasets. From the above reviews, it is obvious that although the classification accuracy \(97.38\%\) reported by Satija et al.11 is acceptable, they suffer from the generalisation capacity of the model. On the other hand, studies that are more generalisable from a design perspective suffer from low accuracy17. In addition, none of these methods was validated against a wide range of publicly available datasets.

Therefore, further research is necessary to develop an accurate and generalised ML model for classifying various ECG noises.

Overview of the proposed knowledge-based ECG noise filtering framework. The framework consists of five main stages: (1) dataset preparation using noise-free and synthetic noisy ECG signals from publicly available databases; (2) feature extraction, (3) selected models for evaluation, (4) Performance Evaluation Metrics for ECG noise detection and classification and (5) Filtering performance evaluation. The pipeline ensures improved ECG signal quality for downstream analysis such as QRS and QT interval measurements.

Problem definition

Reliable ECG interpretation depends on signal quality. Noise originating from patient movement, baseline drift, or electrode instability can distort waveform morphology and reduce the reliability of automated analysis systems. In many clinical environments, particularly during ambulatory monitoring or continuous bedside observation, noise levels vary over time and are not uniform across recordings. A fixed filtering approach may remove some noise but can also distort clinically relevant segments of the ECG, such as the QRS complex or ST segment. Therefore, a knowledge-based filtering strategy that responds to the specific noise characteristics present in the signal is needed.

This work introduces a knowledge-based ECG filtering framework that detects when noise is present, identifies the type of noise, and applies a targeted filtering method. The goal is to improve signal clarity while preserving diagnostic features, supporting both real-time monitoring and downstream clinical interpretation. The input signal \(X_{ECG}\) is a single-lead ECG segmented into 10-second windows for consistent evaluation.

Knowledge-based filtering framework

The framework operates in three stages: (1) determine whether the ECG segment contains noise, (2) classify the noise type if present, and (3) apply a noise-specific filtering method. This structure allows the filtering process to adapt dynamically to changing recording conditions, reducing unnecessary signal distortion. In the first stage, the system determines whether the ECG segment contains noise:

If noise is detected, the segment is further classified to identify the dominant noise type:

Based on the classification result, a noise-specific filtering function is selected:

where \(f_{det}\) and \(f_{cla}\) are the noise detection and classification function. \(\lambda ^{ML}\) is the proposed different ML model for noise detection and classification mentioned in “Selected models for evaluation”. The filtering functions \(f_{BW}\), \(f_{MA}\), and \(f_{EM}\) are designed for the selective removal of baseline drift, motion artefacts, and electrode motion noise, respectively. This adaptive decision structure aims to enhance ECG signal usability in clinical monitoring workflows, reducing noise-induced misinterpretation without compromising waveform integrity.

Methodology overview

The proposed methodology consists of five main stages. First, dataset preparation is performed using noise-free and synthetically generated noisy ECG signals derived from publicly available databases. Second, a comprehensive set of time-domain, frequency-domain, and non-linear features is extracted to characterise the ECG signals. Third, multiple classical ML models are trained and evaluated to detect and classify different types of noise. Fourth, model performance is assessed using unified evaluation metrics, including sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and F1-score. Finally, based on the classification results, a noise-profile filtering strategy is applied, and its effectiveness is evaluated using clinically relevant ECG biomarkers such as the QRS and QT intervals. An overview of the entire framework is illustrated in Fig. 2, where the output of noise classification informs the adaptive filtering process to improve ECG signal quality.

Datasets preparation

A large number of ECG datasets are available in the open-source Physionet database19. However, noise labelling (noisy or noise-free) of all these signals are not available, which is essential for developing supervised ML models for noise detection and classification. In this study, we prepared our datasets pursuing the process that is illustrated in Fig. 3 and described as follows:

The process of dataset preparation for the proposed ECG noise detection and classification model. Firstly, raw noise-free ECG signals and different types of noise, such as BW, MA, and EM, are Minmax normalised to make the same amplitude as noise-free ECG signals. Secondly, all the ECG signals are split into \(4 \times N_s\) subjects to stop data leakage across the subjects. Finally, the total noise-free ECG \(4 \times N_s\) is divided into four groups: one for noise-free and the other three groups for combining (\(3 \times M_s\)) noisy data to generate noisy ECG segments.

-

Noise-free ECG segmentation: In this study, we consider publicly available datasets ECG-ID20, BIDMC21, CINC-201120, CINC-201420, TeleECG22 and MIT-BIH arrhythmia23 for selecting noise-free segments. These datasets were manually annotated based on the unified definition of noisy and noise-free ECG11,24,25. According to that definition, an ECG segment is defined as noisy when the ECG signal is contaminated with any one of the noises, such as baseline wander (BW) and muscle artefact (MA). In addition, an ECG segment is labelled as noise-free when the QRS complex and T wave are clearly visible. We have previously developed a semi-automatic tool for labelling all ECG segments in this study, as mentioned in14. The segment is labelled noise-free if there is no noise in the whole segment, i.e., all peaks (P, Q, R, S, and T) of the ECG signal are visually identifiable in that segment based on the definition published by Satija et.al.11.

ECG signals are also Minmax normalised to make all the ECG signals into the same amplitude range from 0 to 1. Large scales of segments are always better for developing ML models since they can cover different signal patterns that help the model-learning process. Therefore, we get \(4 \times N_s=1338\) ( \(N_s\) is the number of 10s ECG noise-free segments) subjects of noise-free ECG signals from diverse datasets summarised in Table 1.

-

Noise signal segmentation: We have used a publicly available MIT-BIH noise stress database for extracting noise signals26. This dataset has three different types of noise signals, which are electrode motion (EM), muscle artefact (MA), and baseline wander (BW), where SNR is -6,0,6,18,24 dB (page 6). The total number of noisy signals is \(3\times M_s=12919\), equal to the total number of segments (12919) from \(3\times N_s\) subjects collected from diverse datasets (Fig. 3).

-

Preparation of datasets for ECG noise detection and classification: The total number of noise-free ECG signals from \(4\times N_s\) subjects from seven different datasets is split into four groups. One group of subjects for noise-free ECG, and the other three groups of (\(3\times N_s\)) subjects for noisy data generation. We have combined 12919 raw noise-free ECG segments (10s) with \(3\times M_s=12919\) ( \(M_s\) is the number of 10s noisy ECG segments) noisy segments (10s) to create different types of noisy ECG signals such as ECG+BW, ECG+EM and ECG+MA with randomised SNR for noise level. Our subject-wise data combination removes the data leakage across the different subjects and datasets. The total number of 10s ECG segments with corresponding recording length is summarised in the Table 1.

Feature extraction

Feature extraction plays a pivotal role in classical ML frameworks, as it captures discriminative characteristics that differentiate noise types and distinguish noisy from noise-free ECG signals. These features form the basis for training the ML model for both noise detection and classification. In this study, 13 dynamic and statistical features were extracted, as summarised in Table 2. The limited size of this feature set mitigates issues associated with the “curse of dimensionality”27, while still providing high performance, as reflected by model performance exceeding 90%. Employing a compact, well-defined feature set reduces redundancy and the risk of incorporating irrelevant or noisy features, and smaller feature spaces often achieve strong results without requiring additional feature selection or feature importance analysis28,29. Consequently, no feature selection methods were applied in this experiment.

Selected models for evaluation

The proposed ECG noise detection and classification framework utilises four widely used ML models: RF, SVM, ExtraTree, and AdaBoost. Each model has been successfully applied in various ECG-based applications25,30,31, demonstrating strong performance in classification tasks. An overview of each model, including its key parameters, physical interpretation, and role in the framework given below:

-

Support vector machine (SVM) is a supervised learning model that constructs an optimal separating hyperplane between classes in a transformed feature space32. When the data are not linearly separable, kernel functions map the original input space into a higher-dimensional space where separation becomes possible. In this work, we evaluated Gaussian (rbf) and polynomial (poly) kernels, as no single kernel generalises best for all signal classification problems33. The performance of the SVM depends on two main parameters. The regularisation parameter \(C\) controls the trade-off between margin width and classification error: a high value of \(C\) forces the model to correctly classify more points, potentially reducing generalisation. The kernel scale parameter \(\gamma\) in the RBF kernel influences the smoothness of the decision boundary: higher \(\gamma\) leads to more complex boundaries34. Both parameters were optimised to enhance ECG noise detection performance.

-

Random forest (RF) is an ensemble classifier composed of multiple decision trees trained on different subsets of the data35. Each tree is built using a random selection of features and samples, and final predictions are obtained through majority voting. The key parameters include the number of trees (n_estimators), the maximum depth of each tree (max_depth), and the minimum number of samples required to split a node (min_samples_split). Using multiple trees helps reduce overfitting and improves robustness, especially when noise is present in the input signals.

-

ExtraTree follows a similar ensemble approach but introduces additional randomness during training36. Unlike Random Forest, where the best split point is selected, ExtraTree chooses split thresholds at random. This reduces training time and model variance by preventing the trees from becoming too closely fitted to the training data. The parameters controlling model complexity (e.g., max_depth, min_samples_leaf) function similarly to those in Random Forest.

-

AdaBoost is an ensemble model based on boosting, where weak learners (typically decision stumps or shallow trees) are combined sequentially37. After each iteration, misclassified samples are assigned higher weights so that subsequent learners focus on correcting these errors. The number of weak learners (n_estimators) and the learning rate determine how quickly the model adapts to classification errors. This approach helps reduce bias and is well-suited for refining classification performance in cases where signal quality varies.

Section “Optimised hyper-parameter of ML model for noise detection and classification” and Table 3 summarise the hyper-parameters considered during optimisation for all models and list the final values selected for ECG noise detection and classification.

Performance evaluation metrics for ECG noise detection and classification

The following parameters evaluate the performance of the ML models:

The rate of sensitivity (Sen.) defines the successful separation of noise-free segments using the proposed model and is measured by (4).

The Specificity(Sp.) is the rate of correctly detected noisy segments using the proposed model, and it can be calculated by (5).

Accuracy (Acc.) is the relationship to the true value of the measured results, and it can be calculated by (6).

F1 score is a harmonic mean of positive predictive value and sensitivity. F1 score defines the bias towards the noise-free ECG or noisy ECG, and it can be calculated using (7).

-

True positives (TP): The number of ECG segments (10s) detected as a noise-free signal.

-

False positives (FP): The number of ECG segments (10s) incorrectly detected as a noise-free signal.

-

True negative (TN): The number of ECG segments (10s) correctly detected as a noisy signal.

-

False negatives (FN): The number of noise-free ECG segments (10s) detected as noisy signals.

Filtering performance evaluation

The effectiveness of noise detection and classification for filtering ECG signals has been assessed using QRS and QT biomarkers. We have annotated 15050 out of 17127 ECG segments for Q, S and T locations using NeuroKit2 application38, and visually confirmed Q, S, and T locations. A total 2077 segments are left out in the filtering performance evaluation since the NeuroKit2 application could not detect a single peak in those segments. After detecting Q, S and T, we measure the QRS and QT intervals for ground truth (\(QRS_G\), \(QT_G\)), noise-agnostic (\(QRS_{NA}\), \(QT_{NA}\)), noise-presence (\(QRS_{NP}\), \(QT_{NP}\)), and noise-profile (\(QRS_{NPF}\), \(QT_{NPF}\)) filtering. Finally, we have used the Bland-Altman plot for ground truth vs noise-agnostic (\(QRS_G\) vs \(QRS_{NA}\)), noise-presence (\(QRS_G\) vs \(QRS_{NP}\)) and noise-profile (\(QRS_G\) vs \(QRS_{NPF}\) ) filtering for QRS interval and ground truth vs noise-agnostic (\(QT_G\) vs \(QT_{NA}\)), noise-presence (\(QT_G\) vs \(QT_{NP}\)) and noise-profile (\(QT_G\) vs \(QT_{NPF}\) ) filtering for QT interval.

where meanDiff is the proportional mean difference after Bland-Altman analysis. This mean difference shows the ECG signal distortion value compared to the proposed and traditional noise-agnostic filter. In this study, we have used the Bland–Altman plot to compare the effect of noise-agnostic, noise-presence, and noise-profile filtering approaches on biomarker extraction. Bland–Altman plot evaluates the agreement between two medical measurement techniques based on the mean-difference between the ground truth and the proposed method. utilised39. This plot explains the benefit of ECG noise detection and classification in selecting appropriate filtering methods.

Hierarchical ECG noise detection and classification algorithm

The proposed framework for ECG noise detection and classification consists of a hierarchical, multi-stage pipeline, as outlined in Algorithm 1. The input is an ECG signal \(X\) from one of seven publicly available datasets, each with varying sampling frequencies (\(Fs_{rand}\)). The goal is to predict the signal type \(\hat{y}\), categorised as noise-free ECG, or ECG corrupted with baseline wander (BW), electrode motion (EM), or muscle artifact (MA).

Step 1: Feature Extraction: A diverse set of handcrafted features is extracted from the ECG signal. These include signal quality indices (SQIs) such as temporal SQI (\(tSQI\)) and interval-based SQI (\(iSQI\)); entropy measures like Distribution Entropy (\(\overline{DistEn}\)), Fuzzy Entropy, and Sample Entropy (SamEn); and complexity measures such as Petrosian Fractal Dimension (PFD), Katz Fractal Dimension (KD), and Higuchi Fractal Dimension (HFD). Additional statistical and physiological features include kurtosis, higher-order statistics (HOS), signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), \(QRScomplex_{relativepower}\), and detrended fluctuation analysis (DFA).

Step 2: Feature Scaling: The extracted features are normalised using Z-score standardisation:

Step 3: Kernel Density Estimation (KDE): Kernel Density Estimation is applied to visualise feature distribution overlaps across classes at both DSSF (\(Fs_{DSSF}\)) and the unified rate (\(Fs_{500} = 500\)Hz). KDE helps assess the separability of feature spaces post-resampling. KDE plots demonstrated that resampling to 500 Hz compared to o improved the discriminability between noise classes and clean segments, providing better-defined boundaries in feature space. This indicates that 500 Hz preserves critical morphological features necessary for robust classification, and thus was chosen as the unified sampling frequency for further analysis.

Step 4: Model Training and Hyperparameter Optimisation : Four classical ML models are optimised using grid search: SVM, RF and AdaBoost and ExtraTree. Each model is trained on the extracted features for noise detection.

Step 5 and 6: Cross-Dataset Validation: A leave-one-dataset-out cross-validation scheme is employed to ensure generalizability. In each iteration, seven datasets are used for training and validation (90% training, 10% validation), while the remaining dataset is used for testing.

Step 7 and 8: Noise Detection and Classification: The best-performing model is selected based on evaluation metrics and used to detect noisy ECG signals. Detected noisy signals are then passed to a second-stage classifier to predict the specific noise type.

Step 9: Filtering Performance Evaluation: Finally, the framework’s impact is evaluated by comparing key clinical biomarkers, QRS complex duration and QT interval before and after applying the noise detection and classification pipeline.

Experimental results

This section presents the performance evaluation of the proposed ECG noise detection and classification framework. Multiple classifiers were compared using both DSSF and a unified frequency of 500 Hz, with optimised hyperparameter tuning applied to each model. Key performance metrics, including Acc., Sen., Sp., and F1 score, are reported for all classifiers. In addition to quantitative results, confusion matrices and kernel density estimation (KDE) plots are provided to illustrate classifier performance. The KDE plots show the distribution of classifier outputs, providing insights into class separability and supporting the selection of a unified frequency of 500 Hz.

Optimised hyper-parameter of ML model for noise detection and classification

Hyper-parameter tuning is essential for optimising the performance of ML models. Common techniques include trial-and-error, random search, Bayesian optimisation, and grid search. While each method has inherent trade-offs in terms of computational cost and convergence efficiency, we adopted grid search in this study due to its systematic and exhaustive evaluation of the hyper-parameter space, which ensures consistent and reproducible outcomes40. Our ML models were developed using the scikit-learn library. For each model, we defined a discrete set of hyper-parameters and value ranges to be explored during the optimisation process. These are detailed in Table 3, which also includes the final optimised parameters under the “Optimised Hyper-parameters” column. Regarding the sampling frequency, experiments were conducted on ECG signals using both the original sampling frequencies of individual datasets and a unified frequency of 500 Hz. To justify the selection of 500 Hz as the unified sampling frequency, we applied KDE to assess the class separability under different sampling rates. KDE plots demonstrated that resampling to 500 Hz improved the discriminability between noise classes and clean segments, providing better-defined boundaries in feature space. This indicates that 500 Hz preserves critical morphological features necessary for robust classification, and thus was chosen as the unified sampling frequency for further analysis. The subsequent sections present classification results across multiple models and datasets, evaluated under both sampling conditions, along with comparative performance metrics and statistical validation to support the effectiveness and generalizability of the proposed approach.

Performance of ECG noise detection for DSSF

The performance of four classifiers, SVM, Random Forest (RF), AdaBoost, and ExtraTree was evaluated using accuracy (Acc.), sensitivity (Sen..), specificity (Sp.), and F1 score. The results are summarised in Table 4. ExtraTree achieved the highest performance across all metrics with Acc. = 98.11%, Sen. = 98.64%, Sp. = 96.07%, and F1 = 98.88%. SVM and RF demonstrated comparable results (SVM: Acc. = 98.03%, Sen. = 98.34%, Sp. = 96.58%, F1 = 98.83%; RF: Acc. = 97.51%, Sen. = 97.86%, Sp. = 96.01%, F1 = 98.47%). AdaBoost achieved lower performance (Acc. = 95.95%, Sen. = 97.31%, Sp. = 91.26%, F1 = 97.51%). Figure 4a–d present the confusion matrix for AdaBoost, RF, SVM and ExtraTree model, showing the number of ECG segments correctly and incorrectly classified as noisy or noise-free. Based on its consistently superior performance across all metrics, ExtraTree was selected as the final model for ECG noise detection.

Performance of ECG noise detection for unified sampling frequency across the datasets

In this experiment, we have also analysed the unified sampling frequency at 500 Hz across the datasets to compare with DSSF. Our ECG detection system achieves a \(100\%\) score in all the metrics for AdaBoost corresponding to the individual dataset’s sampling frequency. Therefore, it is essential to identify how ML model performance improves across the datasets. In Fig. 6, the kernel density estimation (KDE) plot shows that DSSF splits the noise-free ECG into three parts, while unified sampling frequency (500 Hz) keeps it as one part. As a result, it is easy to separate the two classes for the ML model and improve the performance of ECG noise detection. This is because finer temporal resolution enhances the delineation of subtle waveform components, such as the P, Q, and T waves, which are often distorted by specific types of noise41

Performance comparison for ECG noise detection between dataset-specific sampling frequency (DSSF) and 500 Hz unified sampling frequency using an AdaBoost classifier. AdaBoost shows \(97.92\%\) in all the metrics at sampling frequency 500 Hz compared to the DSSF. It is evident that sampling frequency has a significant influence on ECG noise detection.

Feature response between dataset-specific sampling frequency (DSSF) and unified sampling frequency 500 Hz. (a) DSSF; (b) unified sampling frequency (500Hz) across the ECG datasets. From the kernel density estimate plot, it is clear that DSSF created three scatter points for noise-free ECG, while sampling frequency at 500 Hz shows only one point for noise-free ECG. So, it is easy for the model to separate two classes at 500Hz compared to the DSSF.

In summary, the unified sampling frequency (500Hz) reduces the influence of the DSSF in the feature sets and improves the ML model classification capabilities.

Selection of ML model for noise classification

Performance of ECG noise classification for DSSF

The second step of the proposed hierarchical model is noise classification. After detecting noisy ECG signals, those signals are passed through trained noise classifiers (SVM, AdaBoost, RF and ExtraTree) for noise classification. Based on the performance of these classifiers, we select the best one for building our final noise detection and classification model.

The experimental results are presented in Table 5. From Table 5 we can see that the Adaboost exhibits superior performance across all metrics compared to SVM, ExtraTree and RF. Further, from Table 5, we also observe that the performances of RF and ExtraTree are relatively close to each other.

The AdaBoost classifier showed the highest accuracy for classifying muscle artefact noise (\(94.038\%\)), and the accuracy dropped by 2–4% for classifying baseline wander (\(92.558\%\)) and electrode motion (\(89.046\%\)) noises. Thus, we have selected the AdaBoost classifier for the noise classification task of the proposed hierarchical model.

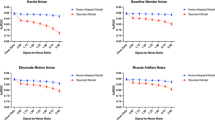

Performance of ECG noise classification for unified sampling frequency across the datasets

As we mentioned in Sect. 6.1.2, the effect of DSSF and unified sampling frequency on ECG noise detection, we have also inspected this for ECG noise classification. The performance of the AdaBoost classifier for ECG noise classification \(4\%\) increases compared to DSSF shown in Fig. 7. We also observe that from the KDE plot presented in Fig. 8, the overlapping of features decreases in unified sampling frequency compared to DSSF, especially ECG+EM noise type. In addition, all the segments of the datasets for different ECG noise types are shrinking to the centre of the KDE plot, which indicates that 500Hz throughout the datasets diminishes the feature overlapping across the ECG noise types.

Performance comparison for ECG noise classification between dataset-specific sampling frequency (DSSF) and 500Hz unified sampling frequency using AdaBoost classifier. The performance of the 500Hz sampling frequency is higher than DSSF. AdaBoost shows \(95.412\%\) (Acc.), \(91.215\%\) ( Sen.), \(97.348\%\) ( Sp.), \(92.560\%\) (F1) for ECG+BW. ECG+EM achieved \(94.962\%\) (Acc.), \(93.508\%\) ( Sen.), \(95.692\%\) ( Sp.), \(92.475\%\) (F1). ECG+EM achieved \(94.962\%\) (Acc.), \(93.508\%\) ( Sen.), \(95.692\%\) ( Sp.), \(92.475\%\) (F1). In addition, ECG+MA achieved \(98.385\%\) (Acc.), \(97.962\%\) ( Sen.), \(98.602\%\) ( Sp.), \(97.667\%\) (F1).

Feature response between dataset-specific sampling frequency (DSSF) and unified sampling frequency 500Hz. (a) DSSF sampling frequency across the ECG; (b) unified sampling frequency (500Hz) across the ECG datasets. For DSSF sampling frequency, ECG+EM class is scattered into two parts, whereas 500Hz shows only one part across the segments. In addition, ECG+BW and ECG+MA are also concentrated in the middle of the plot compared to the DSSF frequency. Therefore, 500Hz achieves better performance in ECG noise classification compared to the DSSF.

Performance of noise detection and classification

The hierarchical model proposed in this study uses the AdaBoost model (Figs. 5 and 7) for ECG noise detection and classification at 500Hz sampling frequency. The reason of 500hz sampling frequency outperforms IDSF is the class separation capability of features as shown in Figs. 6 and 8. Unified sampling frequency (500Hz) across all datasets reduces the ECG signal variation caused by their dataset sampling frequency. The classification performance of the proposed model in terms of Acc., Sen., Sp., and F1 score is shown in Table 6. The accuracy, sensitivity, specificity and F1 score for Noise-free ECG and noisy ECG i.e., ECG+BW, ECG+EM and ECG+MA are (\(99.82\%\),\(99.27\%\),\(99.938\%\) and \(99.88\%\)), (\(95.412\%\),\(91.215\%\), \(97.348\%\) and \(92.560\%\)), (\(94.962\%\),\(93.508\%\),\(95.692\%\) and \(92.475\%\)) and (\(98.385\%\),\(97.962\%\),\(98.602\%\) and \(97.667\%\)) respectively. Figure 9 shows the confusion matrix for the noise-free, BW, EM, and MA classes, illustrating the number of samples correctly and incorrectly classified by the proposed framework.

Noise-free ECG signals obtain higher score values compared to other signal types. On the other hand, the ECG signal with EM noise scores relatively lower values.

The overall performance of the proposed method is on average \(97.145\%\),\(95.489\%\),\(97895\%\) and \(95.646\%\) for all metrics, and is suitable for ECG noise detection and classification.

Benefit of using ECG noise detection and classification

Bland–Altman analysis illustrates that most of the segments were within the \(95\%\) confidence range for QRS and QT intervals, which demonstrates the degree of agreement between the ground truth, noise-agnostic (\(QRS_{NU}\), \(QT_{NU}\)), noise-presence (\(QRS_{NA}\), \(QT_{NA}\)) and noise-profile (\(QRS_{NPF}\), \(QT_{NPF}\)) filtering shown in Fig. 10.

The mean-difference of noise-agnostic filtering is \(-38.23\) ms for QRS interval (\(QRS_{NU}\)), while noise-presence (\(QRS_{NA}\)) and noise-profile (\(QRS_{NPF}\)) mean-difference drop to \(-16.37\) ms and 2.50 ms respectively. In addition, The range of \(QRS_{NU}\) is 212.43 ms, which reduced to 178.97 ms and 144.96 ms for \(QRS_{NA}\) and \(QRS_{NPF}\) respectively (see Fig. 10a–c). From mean difference and range values, it is obvious that noise-presence and noise-profile filtering show better agreement with the ground truth values than noise-agnostic filtering.

For the QT interval, the mean-difference value of noise-agnostic filtering is \(-10.33\) ms (\(QT_{NU}\)), whereas the mean-difference values of noise-presence (\(QT_{NA}\)) and noise-profile (\(QT_{NPF}\)) filtering are \(-2.43\) ms and 4.28 ms, respectively. Furthermore, the range of \(QT_{NU}\) is 414.79 ms while the ranges of \(QT_{NA}\) and \(QT_{NPF}\) are 325.34 ms and 302.49, respectively (Fig. 10d–f).

Bland–Altman analysis with \(95\%\) confidence interval for the Comparison of ground truth vs noise-agnostic (\(QRS_G\) vs \(QRS_{NA}\)), noise-presence (\(QRS_G\) vs \(QRS_{NP}\)) and noise-profile (\(QRS_G\) vs \(NPF_{QRS}\)) filtering for QRS interval (a)–(c), and (d)–(f) for QT interval (\(QT_G\) vs \(QT_{NU}\), \(QT_G\) vs \(QT_{NA}\), \(QT_G\) vs \(QT_{NPF}\)). The mean-difference of noise-presence and noise-profile filterings are \(-16.37\) ms and 2.50 ms, whereas noise-agnostic shows \(-38.23\) ms compared to the ground truth of QRS interval. For the QT interval mean-difference of noise-presence and noise-profile filtering is \(-2.43\) ms and 4.28 ms, while the noise-agnostic filtering mean-difference value is \(-10.33\) ms.

Discussion

Distortion of ECG morphology such as QRS and QT interval because of the noise-agnostic filter (\(QRS_{NU}\), \(QT_{NU}\)) without classifying the type of noise before filtration. (a) Distortion of QRS and QT interval compared to ground truth (\(QRS_{G}\), \(QT_{G}\)) with (noise-presence) and without (noise-agnostic) noise classification for baseline wander (BW) noise. (b) Distortion of QRS and QT interval compared to ground truth with (noise-presence) and without (noise-agnostic) Noise classification for muscle artefact (EM) noise. (c) Distortion of QRS and QT interval compared to ground truth with (noise-presence) and without (noise-agnostic) Noise classification for muscle artefact (MA) noise.

This paper presents a supervised classical ML framework for ECG noise detection and classification. Accurate evaluation of ECG signals is critical for clinical decision-making, as noisy signals can distort key biomarkers such as QRS and QT intervals. Unlike traditional preprocessing approaches that apply predefined filters indiscriminately, our framework detects the presence and type of noise, enabling selective, profile-based filtering to preserve signal integrity.

A major challenge is the preparation of datasets containing both clean and noisy ECG signals. We generated 17,127 unique 10-second ECG segments from seven publicly available datasets, with signal quality assessed by an ECG specialist and no overlap between training and testing sets (ECG-ID, MIT-BIH Arrhythmia, BIDMC, CINC-2011, CINC-2014, MIT-BIH noise stress and teleECG). Experiments were conducted using both the native sampling frequency of each dataset and a unified frequency of 500 Hz to evaluate the effect of sampling frequency on feature distributions and model performance. Classical ML models were compared for ECG noise detection, with ExtraTree performing best for individual dataset frequencies shown in Table 4. Standardising all datasets to 500 Hz reduces feature-space scatter presented in Fig. 6, enabling AdaBoost to achieve 100% performance across datasets shown in Fig. 5. This proves that a unified sampling frequency improves feature separability and overall model effectiveness.

ECG noise detection performance on the MIT-BIH Noise Stress dataset shows high accuracy at low and moderate SNRs (0 dB, -6 dB) but decreases at higher SNRs (18 dB) due to residual noise in “clean” signals summarised in Table 8. This highlights the importance of including realistic noise conditions during training for robust generalisation.

The performance of the proposed model is compared with popular existing approaches in16,25,42,43,44 and11 in Table 7, in terms of Acc., Sen., Sp., and F1. From Table 7, Fu et al. and Xu et al. used private data which is not accessible and F1 score not mentioned From Table 7 we can see that method in44 achieves relatively good scores for Acc and Sen, . However, the Sp. score is low compared to other parameters. On the other hand, for the technique presented in48, the accuracy and specificity rate need to improve to increase the noise detection rate. The algorithm proposed by Satija et al. shows a high-performance rate (more than \(98\%\)). In11, the authors proposed a method that depends on the CEEMD level-wise threshold value to detect noisy ECG signals. The major concern with this method is that the threshold value depends on experimental datasets. Because of this, there is a possibility of misclassifying the noisy and noise-free ECG signals when the datasets differ from experimental ones. The DL model is a breakthrough for removing threshold and handcrafted features dependency, but it needs more datasets to generalise. Liu et al. proposed a DL model for only one dataset and achieved F1 score \(84.72\%\). However, the proposed method achieves \(99.82\%\) across all the metrics after solving sampling frequency impact as mentioned in Fig. 6. Another significant contribution is that it doesn’t depend on specific threshold values because of the ML techniques used in the proposed method.

ECG noise type classification performance across ML models shows that optimised AdaBoost outperforms SVM and other ensemble methods, with unified sampling frequency improving performance by approximately \(3\%\) (Table 5 and Fig. 7).

The hierarchical model combines detection and classification, separating noise-free segments with higher accuracy than specific noise types, reducing unnecessary filtering in Table 6. Electrode motion (EM) shows the lowest classification accuracy, while muscle artifact (MA) shows the highest. This hierarchy enables selective noise-profile filtering rather than blanket filters, improving clinical reliability.

Noise-presence (\(QRS_{NA}\)) and noise-profile (\(QRS_{NPF}\)) filtering reduce distortion in QRS and QT intervals compared to noise-agnostic (\(QRS_{NU}\)) filtering, shown in Fig. 10a–f. Noise-profile filtering preserves biomarkers effectively for pure noise types (ECG+BW, ECG+EM, ECG+MA), while compound noise indicates the need for additional noise classes presented in Fig. 11. These results confirm that selective filtering minimises distortion and enhances the reliability of ECG-derived clinical biomarkers.

The proposed framework offers a threshold-independent machine learning approach for ECG noise detection that generalises effectively across diverse datasets. By combining accurate noise detection with noise-type classification, the method enables selective, profile-based filtering, ensuring that ECG signals are cleaned without unnecessary distortion. This selective filtering preserves critical biomarkers such as QRS and QT intervals, enhancing the reliability of ECG-based clinical assessments. The framework’s robust performance across multiple datasets and sampling frequencies demonstrates its scalability and potential applicability in multicentric and real-world clinical settings, providing a strong foundation for improving the quality of ECG signal analysis and supporting more accurate cardiovascular disease diagnosis.

Conclusion

In this study, we proposed a knowledge-based framework for automatic detection, classification, and selective filtering of noise in ECG signals. Evaluated across seven diverse datasets, the framework identifies the presence and type of noise before applying appropriate filtering. Among classical machine learning models, AdaBoost achieved the highest performance, with 99.82% noise detection accuracy and 97.15% classification accuracy using signals standardised at 500 Hz. The selective noise-profile filtering approach effectively reduced distortion in key ECG biomarkers, minimising the mean QT interval difference to 2.50 ms and QRS interval distortion to 4.28 ms, outperforming noise-presence and noise-agnostic methods. These results show that targeting filters based on identified noise types preserves signal integrity and enhances the reliability of ECG measurements. Robust performance across multiple datasets and acquisition conditions demonstrates scalability and generalisation capability, supporting potential application in multicentric and clinical settings. While the use of synthetic noise may not capture all real-world patterns, consistent results across diverse datasets validate the framework’s practical utility. Overall, this work highlights both the methodological novelty and clinical relevance of knowledge-based ECG noise detection and filtering, offering a reliable approach to improve signal quality and preserve critical biomarkers for accurate cardiovascular disease assessment.

Future Work: Future research will address limitations by incorporating real-world noisy ECG datasets and investigating noise mixtures that occur in practice. We plan to explore sliding window and data augmentation methods to improve noise localisation and robustness. Additional efforts will focus on maintaining high detection accuracy at elevated signal-to-noise ratios. Finally, extending validation to additional ECG biomarkers and adapting the framework for other physiological signals through retraining will expand the system’s applicability across biomedical monitoring scenarios.

Data availability

The dataset used in the current research was obtained from PhysioNet (https://physionet.org/content/) in accordance with the Open Data Commons Attribution License (ODC-By) v1.0. The datasets link is given in ECG-ID: https://physionet.org/content/ecgiddb/1.0.0/; BIDMC: https://physionet.org/content/bidmc/1.0.0/; CINC-2011:https://physionet.org/content/challenge-2011/1.0.0/; CINC-2014:https://physionet.org/content/challenge-2014/1.0.0/; TeleECG:https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/QTG0EP; MIT-BIH arrhythmia:https://www.physionet.org/content/mitdb/1.0.0/; MIT-BIH noise stress:https://www.physionet.org/content/nstdb/1.0.0/.

References

Ichihara, H., Sugino, T., Ishii, S., Iwagaki, T. & Inoue, T. Compact and accurate digital filters based on stochastic computing. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. 7, 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1109/TETC.2016.2608825 (2019).

Wang, D., Liu, J., Xu, J., Jiang, H. & Wang, C. Data sweeper: A proactive filtering framework for error-bounded sensor data collection. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. 4, 487–501. https://doi.org/10.1109/TETC.2015.2411215 (2016).

Bui, N. T. et al. Real-time filtering and ecg signal processing based on dual-core digital signal controller system. IEEE Sens. J. 20, 6492–6503. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2020.2975006 (2020).

Satija, U., Ramkumar, B. & Manikandan, M. S. A unified sparse signal decomposition and reconstruction framework for elimination of muscle artifacts from ECG signal. In ICASSP, IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing - Proceedings, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP.2016.7471781 (2016).

Satija, U., Ramkumar, B. & Manikandan, M. S. A robust sparse signal decomposition framework for baseline wander removal from ECG signal. In IEEE Region 10 Annual International Conference, Proceedings/TENCON, https://doi.org/10.1109/TENCON.2016.7848477 (2017).

Moody, B. E. Rule-based methods for ECG quality control. In Computing in Cardiology (2011).

Jekova, I. C., Krasteva, V. & Abächerli, R. Threshold-based system for noise detection in multilead ECG recordings. Physiol. Meas. https://doi.org/10.1088/0967-3334/33/9/1463 (2012).

Tat, T. H. C., Xiang, C. & Thiam, L. E. Physionet challenge 2011: Improving the quality of electrocardiography data collected using real time QRS-complex and T-wave detection. In Computing in Cardiology (2011).

Orphanidou, C. & Drobnjak, I. Quality Assessment of Ambulatory ECG Using Wavelet Entropy of the HRV Signal. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. https://doi.org/10.1109/10.1109/JBHI.2016.2615316 (2017).

Joutsen, A. et al. Ecg signal quality in intermittent long-term dry electrode recordings with controlled motion artifacts. Sci. Rep. 14, 8882. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56595-0 (2024).

Satija, U., Ramkumar, B. & Manikandan, M. S. Automated ecg noise detection and classification system for unsupervised healthcare monitoring. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 22, 722–732. https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2017.2686436 (2018).

Abdelazez, M., Rajan, S. & Chan, A. D. Signal quality assessment of compressively sensed electrocardiogram. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 69, 3397–3406. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2022.3170047 (2022).

Satija, U., Ramkumar, B. & Manikandan, M. S. A robust sparse signal decomposition framework for baseline wander removal from ecg signal. In 2016 IEEE Region 10 Conference (TENCON), 2470–2473, https://doi.org/10.1109/TENCON.2016.7848477 (IEEE, 2016).

Rahman, S., Karmakar, C., Natgunanathan, I., Yearwood, J. & Palaniswami, M. Robustness of electrocardiogram signal quality indices. J. R. Soc. Interface 19, 20220012. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2022.0012 (2022).

Yang, M., Sang, Y.-F., Liu, C. & Wang, Z. Discussion on the choice of decomposition level for wavelet based hydrological time series modeling. Water 8, 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/w8050197 (2016).

Fu, F. et al. Comparison of machine learning algorithms for the quality assessment of wearable ecg signals via lenovo h3 devices. J. Med. Biol. Eng. 41, 231–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40846-020-00588-7 (2021).

Abbasi, M. U., Rashad, A., Srivastava, G. & Tariq, M. Multiple contaminant biosignal quality analysis for electrocardiography. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 71, 103127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2021.103127 (2022).

Satija Udit, R. B. & Manikandanb, M. S. An automated ecg signal quality assessment method for unsupervised diagnostic systems. Biocybern. Biomed. Eng. 38, 54–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbe.2017.10.002 (2018).

PhysioBank ATM, https://archive.physionet.org/cgi-bin/atm/ATM.

Goldberger, A. L. et al. PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet. Circulation https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.101.23.e215 (2000).

Bousseljot, R., Kreiseler, D. & Schnabel, A. Nutzung der EKG-Signaldatenbank CARDIODAT der PTB über das Internet. Biomed. Tech. https://doi.org/10.1515/bmte.1995.40.s1.317 (1995).

Khamis, H. et al. Qrs detection algorithm for telehealth electrocardiogram recordings. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 63, 1377–1388. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2016.2549060 (2016).

Moody, G. B. & Mark, R. G. The impact of the MIT-BIH arrhythmia database https://doi.org/10.1109/51.932724 (2001).

Kumar, P. & Sharma, V. K. Detection and classification of ecg noises using decomposition on mixed codebook for quality analysis. Healthcare Technol. Lett. 7, 18–24. https://doi.org/10.1049/htl.2019.0096 (2020).

Liu, C. et al. Signal quality assessment and lightweight qrs detection for wearable ECG smartvest system. IEEE Internet Things J. 6, 1363–1374. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2018.2844090 (2019).

McSharry, P. E., Clifford, G. D., Tarassenko, L. & Smith, L. A. A dynamical model for generating synthetic electrocardiogram signals. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2003.808805 (2003).

Wright, E. Adaptive control processes: a guided tour. by richard bellman. 1961. 42s. pp. xvi+ 255.(princeton university press). Math. Gazette textbf46, 160–161. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400874668 (1962).

Guyon, I. & Elisseeff, A. An introduction to variable and feature selection. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 3, 1157–1182. https://doi.org/10.1162/153244303322753616 (2003).

Applied Predictive Modeling, vol. 26 (Springer, 2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6849-3.

Bahrami, M. & Forouzanfar, M. Sleep apnea detection from single-lead ecg: a comprehensive analysis of machine learning and deep learning algorithms. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 71, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2022.3151947 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Wei, S., Zhang, L. & Liu, C. Comparing the performance of random forest, svm and their variants for ecg quality assessment combined with nonlinear features. J. Med. Biol. Eng. 39, 381–392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40846-018-0411-0 (2019).

Jayaraman Rajendiran, D. K., Ganesh Babu, C., Priyadharsini, K. & Karthi, S. Certain investigation on hybrid neural network method for classification of ecg signal with the suitable a fir filter. Sci. Rep. 14, 15087 (2024).

Asl, B. M., Setarehdan, S. K. & Mohebbi, M. Support vector machine-based arrhythmia classification using reduced features of heart rate variability signal. Artif. Intell. Med. 44, 51–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artmed.2008.04.007 (2008).

Singh, P. et al. Efficient detection of myocardial infarction from single lead ECG signal. Article Biomed. Signal Process. Control https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2021.102678 (2021).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010933404324 (2001).

Geurts, P., Ernst, D. & Wehenkel, L. Extremely randomized trees. Mach. Learn. 63, 3–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10994-006-6226-1 (2006).

Hastie, T., Rosset, S., Zhu, J. & Zou, H. Multi-class adaboost. Statistics and its. Interface 2, 349–360. https://doi.org/10.4310/SII.2009.v2.n3.a8 (2009).

Makowski, D. et al. Neurokit2: A python toolbox for neurophysiological signal processing. Behav. Res. Methods 53, 1689–1696. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-020-01516-y (2021).

Bland, J. M. & Altman, D. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. The lancet 327, 307–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(86)90837-8 (1986).

Practical Guide to Hyperparameters Optimization for Deep Learning Models. https://blog.floydhub.com/guide-to-hyperparameters-search-for-deep-learning-models/.

Censi, F. et al. Which resolution for reliable ecg p-wave analysis in atrial fibrillation?. In International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing 2, 385–388. https://doi.org/10.5220/0003091603850388 (2011) ((SCITEPRESS)).

Liu, G., Han, X., Tian, L., Zhou, W. & Liu, H. Ecg quality assessment based on hand-crafted statistics and deep-learned s-transform spectrogram features. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 208, 106269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2021.106269 (2021).

Xu, H. et al. Assessing electrocardiogram and respiratory signal quality of a wearable device (sensecho): semisupervised machine learning-based validation study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 9, e25415. https://doi.org/10.2196/25415 (2021).

Hermawan, I. et al. Temporal feature and heuristics-based noise detection over classical machine learning for ecg signal quality assessment. In 2019 International Workshop on Big Data and Information Security (IWBIS), 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1109/IWBIS.2019.8935757 (IEEE, 2019).

Vijayakumar, V., Ummar, S., Varghese, T. J. & Shibu, A. E. Ecg noise classification using deep learning with feature extraction. SIViP 16, 2287–2293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11760-022-02194-3 (2022).

Tan, H. et al. Neural architecture search for real-time quality assessment of wearable multi-lead ecg on mobile devices. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 74, 103495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2022.103495 (2022).

Liu, S., Zhong, G., He, J. & Yang, C. Multi-task cascaded assessment of signal quality for long-term single-lead ecg monitoring. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 83, 104674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2023.104674 (2023).

Li, Q., Mark, R. G. & Clifford, G. D. Robust heart rate estimation from multiple asynchronous noisy sources using signal quality indices and a Kalman filter. Physiol. Meas. https://doi.org/10.1088/0967-3334/29/1/002 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Project under Grant DP190101248.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.R. Data curation, Methodology, Software, Formal Analysis, Original draft preparation. J.Y. Supervision, Review and Editing. C.K. Conceptualisation, Supervision, Review and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rahman, S., Yearwood, J. & Karmakar, C. Design and evaluation of a knowledge-based ECG noise filtering framework. Sci Rep 16, 2429 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32249-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32249-7