Abstract

Klebsiella pneumoniae, a common gut colonizer, has become a major opportunistic pathogen, especially with the rise of multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains. This study aimed to characterize two lytic bacteriophages against MDR K. pneumoniae strains isolated from hospital associated infections in Senegal. Among 28 MDR K. pneumoniae strains tested, phage vKpIN31 effectively lyse 15 strains encompassing 12 distinct K locus types. While phage vKpIN32 lysed 12 strains with 9 different K locus types, demonstrating broad host range activity. The isolated phages exhibited thermal and pH stability. One-step growth analysis revealed a latent period of 25 and 20 min and burst sizes of 281 and 246 PFU/cell for vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 respectively. The in vitro lytic activity of phages vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 at different multiplicity of infection (1, 10−1, and 10−3) revealed variable lysis efficacy against three K. pneumoniae strains (KP6, KP7, and KP17), with the highest effectiveness observed at an MOI of 10−3 for both phages. Combination of both phages as cocktail led to improved efficacy against the targeted strains Also, both phages significantly reduced biofilm levels, from 18.6% to 67.9% for 24-hour mature biofilms and from 18.1% to 58.7% for 48-hour mature biofilms. Genomic analysis identified both phages as linear dsDNA viruses belonging to the Caudoviricetes class, and Sugarlandvirus sugarland species. No genes associated with a temperate life cycle, integrases, transposable elements, antibiotic resistance, or bacterial virulence were detected in their genomes. These findings highlight vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 as promising candidates for phage therapy. Additionally, their potential extends to serving as sources for antibacterial and antibiofilm agents, signifying their clinical relevance and therapeutic potential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) poses a critical threat to global health, anticipated to surpass cancer in mortality rates by 2050 without substantial intervention1,2. Notably, the ESKAPE-E group comprising Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacter spp and Escherichia coli show increasing resistance to known antibiotics.

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a Gram-negative bacterium found in diverse ecological niches such as soil, plants, and water, and commonly colonizes the human gut. As an opportunistic pathogen, it commonly causes healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) like septicemia, pneumonia, urinary tract infections, surgical site infections, and catheter-related infections3. Hospital-acquired K. pneumoniae infections, particularly due to multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains, pose life-threatening risks, intensifying infection severity and duration4. Globally, K. pneumoniae accounts for 11% of hospital acquired infections5, varying between 8% and 12% in France and USA6,7, and from 6.8% to 13.6% in Senegal8,9,10,11,12.The increased use of carbapenems and fluoroquinolones has accelerated the global spread of resistant strains. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales, identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as an urgent threat13, prominently include carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CRKP), an emerging pathogen14 linked to bloodstream infections and pneumonia with a mortality rate exceeding 40%15. A characteristic feature of K. pneumoniae is the secretion of a polysaccharide capsule that envelops each bacterial cell16. The capsular polysaccharide plays a crucial role in K. pneumoniae capacity to form biofilms and pathogenic K. pneumoniae demonstrated robust biofilms formation, adhering firmly to both living and non-living surfaces17. Biofilms act also as a physical barrier that hinders antibiotic penetration. Moreover, biofilm-associated genes expression upregulates efflux pumps and stress response mechanisms18. These adaptations promote the acquisition of resistance traits and the development of MDR phenotypes17,18. In hospital settings, this is particularly concerning, as biofilm can colonize medical devices and hard surfaces, leading to biofilms acquired infections19,20.MDR K. pneumoniae strains are a warning sign for the post antibiotic crisis and novel alternative therapies and strategies are urgently needed21. One such alternative is phage therapy.

Bacteriophages, commonly referred as phages, are natural predators of bacteria and have been considered for over a century as a means to combat bacterial infections. However, their clinical use was overshadowed for many decades by the dominance of antibiotics. In recent years, phage therapy is regaining interest owing to it’s specificity, capacity for replication, and coevolution with hosts. Phages binds to bacterial surfaces, inject their genetic material, replicate within the bacterial host, and induce lysis. Increasingly explored as an alternative to antibiotics, phage therapy has shown success in numerous reported clinical cases22,23,24, supporting its potential as a safe and promising strategy for combating MDR infections25. Nowadays, more than 80 K. pneumoniae capsular types (K types) have been identified26,27. Phage-encoded depolymerase enzymes, which specifically target capsular polysaccharides (CPS), lipopolysaccharides, or components of the extracellular matrix, facilitate phage access by degrading these structures, thereby enabling the phages to reach and bind to specific receptors on the bacterial surface18. Depolymerases can also render bacteria susceptible to phages, host immunity, and antimicrobial agents28,29. Various Klebsiella phages have demonstrated therapeutic efficacy against K. pneumoniae30,31,32 particularly in reducing biofilm formation30,33.

In this study, we isolated two phages from influent sewage that we further characterize. The biological properties of the potential therapeutic phages vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 were evaluated. The tests include host range, stability, burst size, and activity against both planktonic and biofilm-associated bacteria. We further conducted comprehensive genomic characterization of the phages through whole-genome sequencing to provide insights for their potential therapeutic development and application for phage therapy.

Materials and methods

Bacterial isolates, antibiotic susceptibility testing and culture conditions

Twenty-eight K. pneumoniae isolates were collected from clinical specimens (urine [n = 7], blood [n = 7], and wound [n = 14]) obtained from hospitalized patients at Hospital Aristide Le Dantec and Children’s Hospital Center Albert Royer of Fann between 2018 and 2021. The identification of bacterial isolates as K. pneumoniae was conducted using standard methodologies, including Gram staining, cultivation on selective media, and standard biochemical reactions.

The susceptibility of these K. pneumoniae isolates to different antibiotics was determined using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method, as previously outlined34 and detailed in an earlier study35. Stock cultures were preserved in Luria Bertani (LB) medium (Difco Laboratories, USA) supplemented with 20% glycerol at − 20 °C. Re-identification and characterization of Sequence Types (STs), K locus type (KL), and O locus type (OL) were accomplished through whole genome sequencing and subsequent bioinformatic analysis using Kaptive 2.036 (Supplementary Table S1). Bacterial culture was carried out in Luria Bertani (LB) broth or on LB agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI, USA) at 37 °C. Bacterial growth was monitored turbidimetrically by assessing the optical density at 600 nm (OD600), where an OD unit of 1.0 corresponded to 3 108 cells/mL.

Phages isolation, purification, host range and efficiency of plating (EOP)

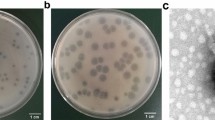

A total of sixteen sewage samples were collected between June and August 2022. These included hospital wastewater from Hôpital Militaire Ouakam, Hôpital Idrissa Pouye, Hôpital Aristide Dantec, and Hôpital Fann. Community wastewater samples were collected from Canal 4 and Point E. Additionally, samples were taken from wastewater treatment facilities at Cambérène, Station de Relèvement UCAD, and Zone de Captage. (Fig. 1). Each sample underwent centrifugation (5000 g, 10 min at 4 °C) and the supernatants were filtered through a 0.22-µm-pore-size membrane (Millex, Syringe Filter). The filtered supernatants were assessed for phage presence using the double-layer agar method on each of the 28 strains. In this method, 10 µL of the sample was added to a freshly formed lawn of the bacterium in soft LB agar (0.7%) over double concentrated LB agar (1.4%). Clear plaques were picked and subjected to three rounds of purification. Purified phages were then stored at 4 °C and − 80 °C in 20% (v/v) glycerol until further experimentations.

To determine the host range, the isolated phages were tested using a spot test on the 28 clinical K. pneumoniae strains. Briefly, the spot test method in which a bacterial lawn was spread on the top agar, and 4 µL of serially diluted phage solution (2 × 1010 PFU/mL) were spotted onto the bacterial lawn. Following a 24-hour incubation period, we examined whether or not any lysis plaque was present. Interestingly, two phages, vKpIN31 and vKpIN32, display a broad host capsular type range. Strains exhibiting clearance zones for vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 phages were selected for EOP analysis using spot test assay. The ratio of plaques formed on the test strain to those formed on the host strain was reported as the EOP. The experiments were performed independently in triplicate, with each assay conducted in triplicate.

Phage stability

To evaluate the thermal stability of phages vKpIN31 and vKpIN32, 100 µL of phage solutions (2 × 1010 PFU/mL) was incubated at temperatures of 25, 40, 55, 60, 65, and 70 °C for 1 h. Subsequently, 50 µL of the samples were drawn to determine phage concentrations. These samples were then 10-fold diluted, and 4 µL of each dilution was spotted onto LB agar with host bacteria, followed by overnight incubation. Incubation at temperatures of 37 °C used as control condition. Subsequently, plates were examined to ascertain phage titers. For the pH stability assessment, 10-fold diluted aliquots were done after 1 h of incubation in SM buffer with various pH values (3, 5, 9 and 12) or pH 7.5 (control), and phage titers (PFU/mL) were determined. All experiments were performed independently in triplicate, with each assay conducted in triplicate.

In vitro evaluation of bacteriolytic activity and one step growth

The in vitro bacteriolytic activity of phages vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 against their respective bacterial host was assessed at different MOIs37. A volume of 200 µL of overnight culture was diluted in 10 mL of fresh LB and incubated at 37 °C until the bacterial OD600 reached 0.2. Bacterial suspension and phages at different MOI (1, 10−1, 10−3) were added in microplates followed by incubation at 37 °C with agitation. As a control sample, K. pneumoniae isolates were incubated with LB without phages. Bacterial growth was monitored by measuring OD600 every 10 min using a spectrophotometer for 16 h. Each experiment was independently conducted in triplicate with triplicate assays performed for each replicate.

For one-step growth (OSG) experiments, a previous described method38 was used. Following phage adsorption with the host strain (MOI 0.01) at room temperature for 5 min, the mixture underwent centrifugation at 10,000 g for 30 s at 4 °C, and the supernatant was removed. The pelleted cells were then resuspended in 20 mL of preheated (37 °C) LB broth and centrifugate at 10,000 g for 30 s at 4 °C (repeated 3 times). Final resuspended pellet was incubated at 37 °C. Samples were collected at 5-minutes intervals over 60 min. Phage titer was determined using the double-layer agar method and expressed as PFU/mL. The burst size was established following the formula: burst size = (average of free phage after burst average of free phage before burst) / (phage administered– unattached phages). Experiments were repeated three times.

Effect of phage treatment on bacterial biofilm formation

We assessed the impact of phages vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 on pre-existing biofilms formed by different strains using a previously documented method39. An overnight culture of each strain was 10-fold diluted into fresh LB and incubated at 37 °C until reaching 0D600 0.2. A volume of 100 µL of the culture were transferred to a 96-well microtiter plate and incubated at 37 °C for 24 and 48 h. The plates were then emptied and cleaned three times with a sterilized Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) (pH 7.4). Each well was then treated with either 100 µL of the phage solution in SM buffer (pH 7.4) at various MOIs (1 and 10) or supplemented with LB media (control condition). The plates were incubated for an additional 24 h at 37 °C.

After the incubation period, the wells were emptied again, cleaned twice with sterilized PBS, and subsequently stained with 150 µL of 1% crystal violet per well. The plates were left standing for 15 min at room temperature. Following this, the wells were rinsed with sterile water, and any remaining bound stain was solubilized in 150 µL of 100% ethanol for 10 min. A volume of 100 µL was transferred into a fresh 96-well plate. The reduction in biomass was determined by measuring the absorbance difference at 600 nm between the control (untreated) and phage-treated wells. Each experiment was replicated three times.

Phage DNA extraction and whole genome sequencing

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was isolated from high-titer stocks (> 1010 PFU/mL). Initially, 1 mL of phage lysate was treated with 10 µL of DNase I (20 U) and 4 µL of RNase A (20 mg/mL), followed by incubation for 30 min at 37 °C. DNA extraction was then performed using the phenol-chloroform method40. To assess the quality of the samples, nucleic acid concentrations were quantified using a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Thermos Fisher Scientific). For library preparation, 1 ng of DNA was used with Nextera XT DNA library preparation kits (Illumina®, San Diego, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. WGS was performed on Illumina® iSeq100 sequencers utilizing the 300-cycle i1 Reagent V2 Kit (Illumina®, San Diego, CA, USA).

Bioinformatic analysis

We conducted quality assessment of reads using FastQC v0.12.141, followed by adapter trimming with trim-galore v0.6.1042. Trimmed paired-end reads underwent de novo assembly with SPAdes v3.15.543 in careful mode. Assembled contigs were pre-visualized using Bandage v0.9.044. Coverage per contig and assembly validation were performed using BBMap v35.8545. The assembled whole-genome sequences were compared with other phages for sequence similarities using Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLASTN) (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PAGE_TYPE=BlastSearch (accessed on 21 September 2023)). Top hits with scores and identity ≥ 90% were compared to the phage genomes, and Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) based on BLAST+ (ANIb) was calculated by JSpeciesWS46. Ragtag47 was used to identify and correct potential misassemblies by comparing with the closest identified phage. Further, the input genome, sorted and indexed with Samtools v1.1848 was submit to assembly errors corrections using Pilon v1.2449. Phage termini were identified with PhageTerm50. Predicted coding sequences (CDS), transfer RNAs (tRNAs), transfer-messenger RNAs (tmRNAs), virulence factors (VFs), antimicrobial resistance genes (AMRs), clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPRs) and functional annotation for CDS using the PHROGs database were done using Pharokka v1.3.051. The pharokka_plotter option was used for circular genome visualization. Whole genome alignment with the closely relative phage were completed using Clinker v0.0.2852.

Statistical analyses

Graphs and statistical analysis of significance were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism program (GrapPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess statistical significance, with a p-value < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

Phage isolation, purification, host range and EOP assay

Phages vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 were isolated from influent sewage samples collected from Canal 4 and Station de relèvement (UCAD), using K. pneumoniae KP7 as the host. Both phages produced clear plaques, 0.5–1 mm in diameter, without surrounding halos. Through phage purification methods, concentration, and titration, a pure high-titer stock (2 × 1010 PFUs/mL) was obtained. Host range analysis against 28 MDR K. pneumoniae strains revealed that phage vKpIN31 effectively targeted 15 strains with 12 distinct K locus types, while phage vKpIN32 infected 12 strains with 9 different K locus types. Specifically, vKpIN31 demonstrated infectivity against K. pneumoniae strains expressing capsules types K2, K7, K14, K15, K17, K22, K25, K27, K30, K37, K57, K102. Meanwhile, vKpIN32 showed infectivity toward strains with capsule types K2, K7, K14, K15, K22, K25, K27, K37, K102 capsules.

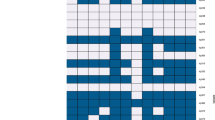

To further evaluate phage infectivity, EOP was determined for each susceptible strain. Serial dilutions of the phage lysate (2 × 1010 PFU/mL) were spotted onto lawns of susceptible strains and compared to the reference host KP7. EOP experiments on the susceptible strains panel illustrated that vKpIN31 generally demonstrated higher plating efficiency on its susceptible hosts compared to vKpIN32 (Fig. 2). Notably, strains KP2, KP6, KP7, KP9, and KP17 demonstrated high susceptibility to both vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 phages (Fig. 2).

Thermal and pH stability studies

The stability of vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 was assessed under varying pH and temperatures for 1 h, followed by determining the phage titers.

Thermal stability was evaluated at temperatures of 25, 40, 55, 60, 65 and 70 °C. Phage titers post-treatment at various temperatures were compared with those of phage stored at 4 °C (control) (Fig. 3a,b). For vKpIN31, there was no significant reduction in phage stability after incubation at 25 °C (p-value = 0.5253) and 40 °C (p-value = 0.0943). However, a marked reduction in phage viability was observed at 55, 60, and 65 °C (p-value < 0.0001). Similarly, vKpIN32 exhibited no significant reduction in stability at 25 °C (p-value = 0.1871), but a decline in viability was notable at 40, 55, 60, and 65 °C (p-value < 0.0001). Incubation at 70 °C resulted in the absence of viable phages for both vKpIN31 and vKpIN32. Phage titers under different pH conditions were compared to those at pH 7.5, considered as neutral (Fig. 3c,d). Both phages exhibited robust stability at pH 3, 5, and 9, while a significant reduction in phage titer was observed at pH 12 (p < 0.0001).

Stability of phages vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 under diverse Conditions. (a,b) Effects of temperature on the stability of phages: Incubation of phages vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 at various temperatures for 1 h (c,d) Effects of pH on the stability of phages: Incubation of phages under different pH values for 1 h. The experiments were independently conducted in duplicate with triplicate assays. The data are presented as the means ± standard errors from three replicates. ‘ns’ means no significant difference, ‘*’ means P < 0.05, ‘**’ means P < 0.01, ‘***’ means P < 0.001, ‘****’ means P < 0.0001.

In vitro evaluation of bacteriolytic activity and burst size

The lytic in vitro activity of phages vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 was investigated against three distinct host bacteria: KP6, KP7 and KP17, monitored by changes in OD600 nm over 16 h incubation period (Fig. 4a, b and c). Bacterial growth in the absence of phage served as the control and showed a steady increase in OD over time (KP6: OD 0.168 ± 0.041 to 0.990 ± 0.232; KP7: 0.174 ± 0.049 to 0.988 ± 0.186; KP17: 0.163 ± 0.039 to 0.857 ± 0.132). In contrast, cultures treated with phages at various MOIs (MOI 1, 10−1, and 10−3) showed consistently lower OD values compared to untreated controls (Fig. 4d–f). The experiment highlighted varying lysis efficacy of both phages, depending on the MOI, with MOI 10−3 showing the highest efficacy against the three hosts, minimizing phage resistance compared to MOI 1 and 10−1. Additionally, the combination of both phages resulted in improved bacterial clearance, indicating a potential synergistic effect (Fig. 4g–i).

In vitro planktonic cell lysis assay. Evaluation of phage vKpIN31 against strains (a) KP6, (b) KP7, (c) KP17; phage vKpIN32 against strains (d) KP6, (e) KP7, (f) KP17; and the combination of phages vKpIN31-vKpIN32 against strains (g) KP6, (h) KP7, (i) KP17 over a 16-hour period using spectrophotometer. Each phage was studied at multiplicities of infection (MOI) 1, 10− 1, and 10− 3. The data represent the means and standard errors from three biological and technical triplicate experiments for single phage treatment and duplicate experiments for phage cocktail treatment.

The OSG (One Step Growth) experiment was performed to assess the latent period and average burst size of the phages. Phages vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 exhibited latent periods of 25 and 20 min, respectively, while the estimated average number of new phage particles released per infected cell (burst size) was 281 and 246 PFU/cell, respectively (Fig. 5).

Effect of phage treatment on bacterial biofilm formation

The potential of phages to degrade established biofilms, reflecting its invasion efficiency, can be valuable in phage therapy. Mature biofilms aged 24 h and 48 h were exposed to either phage vKpIN31 or vKpIN32 at varying MOIs (10 and 1) (Fig. 6).

Biofilm inhibition of phages vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 for strains (a) KP6, (b) KP7, and (c) KP17. Static 24-hour and 48-hour preformed biofilms in 96-well plates were treated with phages at two different MOIs (1 and 10) and incubated for an additional 24 h. Following staining with 0.1% crystal violet, OD600 measurements were taken. The results are presented as a violin plot, showing the median and quartiles, based on biological triplicates with technical triplicates. Statistical significance is denoted as “*” for p-value < 0.05, “**” for p-value < 0.01, “***” for p-value < 0.001, and “****” for p-value < 0.0001.

Both phages, vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 demonstrated the ability to reduce biofilm biomass, with reductions ranging from 18.6% to 67.9% for 24 h old biofilms and from 18.1% to 58.7% at 48 h old biofilms. With strains KP6 and KP7, treated cultures with phages exhibited significantly lower ODs compared to untreated cultures (p-value < 0.05) at 24 h. However, for strain KP17, vKpIN31 did not significantly reduce biofilm formation at 24 h for MOI 1 (p-value = 0.306), though it was effective at MOI 10 (p-value = 0.040). Phage vKpIN32 didn’t reduce biofilm biomass for both MOIs at 24 h. Nonetheless, a notable reduction in pre-formed biofilm was observed for both phages at 48 h (p-value < 0.01).

Genome features and comparative genome analysis of phages vKpIN31 and vKpIN32

The phages vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 were sequenced and analyzed to determine their structural and functional characteristics. Both phages are not permutated and feature redundant ends which suggest linear dsDNA. The genome sizes are 77.175 bp for vKpIN31 and 107.104 bp for vKpIN32, with GC contents of 45.01% and 45.26%, respectively. Both phages exhibit high coding density, reaching 90.67% for vKpIN31 and 91.98% for vKpIN32.

Annotation of the vKpIN31 phage genome revealed the presence of 109 coding sequences (CDS), of which 46.7% showed functional homologies to known proteins, while 53.2% were classified as hypothetical proteins. The functional CDS were predicted to encode proteins involved in host cell lysis, structural components (head, tail, connector, and packaging proteins), along with proteins linked to DNA, RNA, nucleotide metabolism, transcription regulation, morons, auxiliary metabolism. Additionally, 22 tRNA-encoding regions were also identified in the vKpIN31 genome.

Conversely, the vKpIN32 genome contained 174 CDS, with 64.3% predicted as hypothetical proteins. Similar to vKpIN31, the predicted functional CDSs in vKpIN32 were implicated in host cell lysis, DNA/RNA/nucleotide metabolism, structural components, and specific functional proteins. A total of 20 tRNA-encoding regions were also detected. Circular representations of phages vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 are illustrated in Fig. 7a. Notably, both phages did not encode any genes associated with lysogeny, toxins, or AMR, and a detailed description of the CDS is available in Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Table S3.

Genomic features. Predicted coding sequences (CDSs) of phages (a) vKpIN31 and (b) vKpIN32 with transfer RNAs (tRNAs), transfer-messenger RNAs (tmRNAs), virulence factors (VFs), antimicrobial resistance genes (AMRs), clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPRs) and functional annotation of the CDSs. Clinker gene cluster comparison of the whole genome of phages (c) vKpIN31 and (d) vKpIN32 with per cent amino acid identity represented by grayscale links between genomes. Each similarity group is assigned a unique colour.

The nucleotide-level genome comparison of vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 with closely related phages was conducted with the BlastN search to assess their novelty. As reported by the International Committee on the Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV), a nucleotide divergence of at least 5% is required to classify phages as distinct species53. The average nucleotide identity for vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 ranged from 97.50% to 93.39% with phages such as Klebsiella phage KpGranit (Accession: MN163280.1), Kpn02 (Accession: OQ790079.1), vB_Kpn_IME260 (Accession: NC_041899.1), vB_KppS-Storm (Accession: LR881112.1), and Sugarland (Accession: NC_042093.1), all belonging to Caudoviricetes class, Demerecviridae family, and Sugarlandvirus genus. Both vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 were classified within the Sugarlandvirus sugarland species, with closely related, Klebsiella phage Sugarland and vB_KppS-Storm (Supplementary Table S4, Fig. 7b).

Discussion

The global rise of AMR in K. pneumoniae, particularly in hospital environments, presents a significant public health concern. Hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) caused by MDR strains are associated with increased morbidity, extended hospital stays, and limited treatment options. Main resistance mechanisms of MDR K. pneumoniae include the production of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) and carbapenemases54. In this study, 35.71% of the K. pneumoniae isolates were classified as extensively drug-resistant (XDR), with higher resistance profiles than previously reported11,55,56. All isolates demonstrated resistance to β-lactams (ampicillin, piperacillin, ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, cefepime). Moreover, over 35.7% displayed resistance to carbapenem; 82.1% to aminoglycosides; 96.4% to fluoroquinolones; 100% to cyclins; 28.5% to Fosfomycin; and 92.8% to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole35. These findings are especially concerning as carbapenems are among the last-resort antibiotics for treating infections caused by resistant Enterobacterales57.Given the rising burden of AMR, alternative therapeutic strategies, such as bacteriophage therapy, are gaining renewed attention. In this context, two lytic phages were isolated from influent sewage samples and subsequently characterized for their efficacy against these K. pneumoniae strains.

Whole-genome sequencing and bioinformatic analysis of 28 K. pneumoniae strains revealed 20 distinct capsular locus (K-locus) types, suggesting a high diverse profiles in K. pneumoniae involved in HAIs in Senegal58. The two isolated phages, vKpIN31 and vKpIN32, demonstrated broad capsule host ranges by effectively targeting 12 and 9 strains, respectively, with different K locus types. Phages infectivity relies on their ability to bind to bacterial surfaces., which require a high level of specificity for surface structures59. In K. pneumoniae, the primary external structure is the polysaccharide capsule (CPS or K antigen), which forms a dense protective layer over the bacterial cell and shields surface structures such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) or exopolysaccharide (EPS)59. Currently, serological methods have identified 77 unique K-types (ranging from K1 to K82), while genome sequencing has unveiled 86 capsular polysaccharide synthesis (CPS) loci, suggesting the potential for further distinct capsular structures59.

The broadest host ranges reported to date were observed in phages vB_Kpn_K7PH164C4 and vB_Kpn_K30λ2.2, both belonging to the Sugarlandvirus genus which successfully infected strains representing 23 different K-types from a complete panel of 77 Klebsiella K-types60. Although vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 have not yet been tested against the full capsular diversity, their performance in this study positions them as promising broad-host-range candidates. Phage infectivity is further enhanced by the presence of depolymerases enzymes associated with virion tail fibers or tail spikes that degrade specific capsule polysaccharides, thereby enabling access to LPS or EPS layers61. Phages harboring multiple depolymerases are rare but critical for targeting a broader range of Klebsiella capsular types62,63,64.

The persistence and efficacy of phages rely significantly upon external environmental factors, notably temperature and pH, which directly affect replication and stability. Our investigations revealed the robust resilience of both phages within a temperature range of 25 °C to 40 °C, with optimal performance at 37 °C, the average human body temperature. Temperature plays a key role in phage viability, attachment, and genome injection into the host cell65. Optimal temperatures are essential during phage replication and influence phage attachment and successful genome insertion into the host65. Additionally, both vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 remained stable across a broad pH spectrum (pH 3 to 9). However, their viability was significantly reduced at extreme alkaline conditions (pH 12). The adaptability of phages to variable environmental conditions is crucial for therapeutic applications, especially considering diverse administration routes66.

Phage life cycle parameters play a critical role in their therapeutic efficacy, as phage-induced bacterial killing largely depends on replication dynamics67. In this study, the isolated K. pneumoniae phages, vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 have latent periods of 25 and 20 min, respectively. Klebsiella phages have been reported to exhibit a latent period of approximately 20 min68,69,70 extending up to 40 min71,72. The burst size of vKpIN31 (281 PFU/cell) and vKpIN32 (246 PFU/cell) were comparatively high. For reference, other Klebsiella phages such as K14-2 (32.9 PFU/cell)68. vB_Kpn_ZCKp20p (100 PFU/cell)39, vB_KpnM_Kp1(126 PFU/cell)73 have reported lower burst sizes. However, certain phages demonstrate even greater productivity, including vB_Kp_XP4 (387 PFU/cell)74 vB_kpnP_KPYAP-1 (473 PFU/cell)69 and vB_Kpn_ZC2 (650 PFU/cell)32. Phages exhibiting short latent periods and high burst sizes are particularly well-suited for the acute phase of infection, rapidly reducing bacterial loads and enhancing the effectiveness of host immune responses and adjunct therapies75,

Biofilm formation represents a critical pathogenicity factor in various bacterial species, significantly impacting antibiotic effectiveness by impeding bacterial penetration and evading host immune responses. Thus, we evaluated the impact of vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 at different MOIs on biofilms producer K. pneumoniae strains. Both phages significantly disrupted 24 and 48 h biofilms, with reductions ranging from 18.6% to 67.9% and 18.1% to 58.7%, respectively. This activity is likely mediated by phage-associated enzymes, particularly depolymerases, which not only degrade the bacterial capsule but also target the extracellular polysaccharide matrix of biofilms76. Phages have shown efficacy in reducing bacterial biofilms on medical devices and in preventing biofilm formation77. Furthermore, combination therapies involving phage and antibiotic have demonstrated synergistic effects in eradicating biofilms, enhancing antibiotic penetration and efficacy78.

Whole-genome analysis revealed that both vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 belong to the Sugarlandvirus genus, Sugarlandvirus sugarland species and are closely related to phage Sugarland and phage vB_KppS-Storm, respectively. The genome annotation revealed that 45.01% (vKpIN31) and 45.26% (vKpIN32) of predicted proteins were hypothetical, underscoring the need for further functional characterization. The presence of numerous tRNA-encoding genes in both genomes may enhance translational efficiency and facilitate infection of diverse hosts, as reported in other studies79,80. Additionally, both phages encode 12 tail-related proteins, including tail spikes and fibers, which are crucial for host recognition and binding. Phages encoding a wide array of tail structures typically exhibit enhanced binding versatility, presence of multiple depolymerases and an expanded host range81. The vKpIN31 genome harbors an endolysin, while vKpIN32 contains spanin, holin, and endolysin, crucial for facilitating bacterial lysis. Importantly, in silico analyses of vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 genomes revealed an absence of bacterial virulence or AMR genes, thereby posing no risk of transmitting resistance or virulence genes, which ensures its safety and promise as candidates for clinical applications.

Conclusion

In this study, two lytic phages vKpIN31 and vKpIN32, infecting MDR K. pneumoniae were isolated from two influent sewage water in Dakar. Both phages showed high lytic activity against different K. pneumoniae strains and remained stable under varied environmental conditions. They demonstrated a broad host range and cocktail of the two phages was more effective than individual phages in eradicating planktonic cells. Both phages also showed notable antibiofilm activity. Genomic analysis confirmed that both phages belong to the Sugarlandvirus sugarland species and do not harbor any bacterial virulence or AMR genes. Given their favorable physiological and genetic characteristics, vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 represent promising candidates for phage therapy. The phages vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 hold significant potential for clinical and public health applications, particularly in the fight against MDR K. pneumoniae infections. Future work will include broader host range testing across diverse CPS types and other Enterobacterales, as well as evaluation of phage-antibiotic synergy. Functional studies on depolymerases that may reveal additional therapeutic value. Next steps include preclinical trials to assess safety and efficacy of phages, with the goal of advancing to clinical testing and exploring their use in varied healthcare settings in Senegal.

Data availability

The genome assemblies and annotations were deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) under the project number PRJEB72148 and SRA and assembly accession numbers ERR12535901 and ERR12535902 for vKpIN31and vKpIN32respectively.

References

O’Neill, J. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations (2016).

Murray, C. J. et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet (2022).

Wyres, K. L. & Holt, K. E. Klebsiella pneumoniae as a key trafficker of drug resistance genes from environmental to clinically important bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 45, 131–139 (2018).

Paczosa, M. K. & Mecsas, J. Klebsiella pneumoniae: going on the offense with a strong defense. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 80, 629–661 (2016).

Ashurst, J. V. & Dawson, A. Klebsiella pneumonia (2018).

SPF. Enquête Nationale de prévalence des infections nosocomiales et des traitements anti-infectieux En établissements de santé, mai-juin 2017. Santé Publique France 270 (2019).

Magill, S. S. et al. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. N Engl. J. Med. 370, 1198–1208. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1306801 (2014).

Dia, N. et al. Résultats de l’enquête de prévalence des infections nosocomiales Au CHNU de Fann (Dakar, Sénégal). Med. Mal Infect. 38, 270–274 (2008).

Fall Infections Nosocomiales à La réanimation Du Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Aristide Le Dantec. Etude Prospective De Novembre 2005 à Octobre 2007, Thèse De Doctorat (Unversité Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar, 2008).

Sene, M. V. T. Aspects épidémiologiques Et bactériologiques Des Infections Nosocomiales Au Service De Réanimation Du Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Aristide Le Dantec: étude rétrospective De Janvier 2013 à Décembre 2014. Thèse De Doctorat (Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar, 2017).

Bourzama, S. Aspects épidémiologiques et bactériologiques des infections nosocomiales à la réanimation du Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Aristide Le Dantec. Etude prospective du 1er Janvier au 30 juin Thèse de doctorat, Faculté de Médecine, Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar (2018).

Taoussi, N. Contribution À L’étude Des Infections Nosocomiales à bactéries Multirésistantes À L’hôpital Principal De Dakar Enquête Prospective Sur 6 Mois. Thèse De Doctorat (Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar, 2011).

CDC. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States. (US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, 2019). (2019).

Band, V. I. et al. Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae exhibiting clinically undetected colistin heteroresistance leads to treatment failure in a murine model of infection. MBio 9, 02448–02417. https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio (2018).

De Oliveira, D. M. et al. Antimicrobial resistance in ESKAPE pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 33, 00181–0119. https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr (2020).

Wang, H., Wilksch, J. J., Lithgow, T., Strugnell, R. A. & Gee, M. L. Nanomechanics measurements of live bacteria reveal a mechanism for bacterial cell protection: the polysaccharide capsule in Klebsiella is a responsive polymer hydrogel that adapts to osmotic stress. Soft Matter. 9, 7560–7567 (2013).

Wang, G., Zhao, G., Chao, X., Xie, L. & Wang, H. The characteristic of virulence, biofilm and antibiotic resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 17, 6278 (2020).

Kochan, T. J. et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates with features of both multidrug-resistance and hypervirulence have unexpectedly low virulence. Nat. Commun. 14, 7962 (2023).

Wu, Y. et al. A novel polysaccharide depolymerase encoded by the phage SH-KP152226 confers specific activity against multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae via biofilm degradation. Front. Microbiol. 10, 2768 (2019).

Rao, V., Ghei, R. & Chambers, Y. Biofilms research—implications to biosafety and public health. Appl. Biosaf. 10, 83–90 (2005).

Mah, T. F. C. & O’Toole, G. A. Mechanisms of biofilm resistance to antimicrobial agents. Trends Microbiol. 9, 34–39 (2001).

Nick, J. A. et al. Host and pathogen response to bacteriophage engineered against Mycobacterium abscessus lung infection. Cell 185, 1860–1874 (2022).

Petrovic Fabijan, A. et al. Safety of bacteriophage therapy in severe Staphylococcus aureus infection. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 465–472 (2020).

Bao, J. et al. Non-active antibiotic and bacteriophage synergism to successfully treat recurrent urinary tract infection caused by extensively drug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Emerg. microb. infect. 9, 771–774 (2020).

Pirnay, J. P. et al. Personalized bacteriophage therapy outcomes for 100 consecutive cases: a multicentre, multinational, retrospective observational study. Nat. Microbiol. 9, 1434–1453 (2024).

Ørskov, I. & Ørskov, F. in Methods in microbiology Vol. 14 143–164 (Elsevier, 1984).

Pan, Y. J. et al. Genetic analysis of capsular polysaccharide synthesis gene clusters in 79 capsular types of Klebsiella spp. Sci. Rep. 5, 15573 (2015).

Latka, A., Maciejewska, B., Majkowska-Skrobek, G., Briers, Y. & Drulis-Kawa, Z. Bacteriophage-encoded virion-associated enzymes to overcome the carbohydrate barriers during the infection process. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 101, 3103–3119 (2017).

Gordillo Altamirano, F. L. & Barr, J. J. Phage therapy in the postantibiotic era. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 32, 00066-00018 (2019).

Wintachai, P. et al. Characterization of extended-spectrum-β-lactamase producing Klebsiella pneumoniae phage KP1801 and evaluation of therapeutic efficacy in vitro and in vivo. Sci. Rep. 10, 11803 (2020).

Peng, Q. et al. Characterization of bacteriophage vB_KleM_KB2 possessing high control ability to pathogenic Klebsiella pneumoniae. Sci. Rep. 13, 9815 (2023).

Fayez, M. S. et al. Morphological, biological, and genomic characterization of Klebsiella pneumoniae phage vB_Kpn_ZC2. Virol. J. 20, 86 (2023).

Rahimi, S. et al. Characterization of novel bacteriophage PSKP16 and its therapeutic potential against β-lactamase and biofilm producer strain of K2-Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae pneumonia infection in mice model. BMC Microbiol. 23, 233 (2023).

Bauer, A. W., Kirby, W. M., Sherris, J. C. & Turck, M. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 45, 493–496 (1966).

Ndiaye, I. et al. Antibiotic resistance and virulence factors of Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae involved in Healthcare-Associated infections in Dakar, Senegal. Archiv Microbiol. Immunol. 7, 65–75 (2023).

Lam, M. M., Wick, R. R., Judd, L. M., Holt, K. E. & Wyres, K. L. Kaptive 2.0: updated capsule and lipopolysaccharide locus typing for the Klebsiella pneumoniae species complex. Microb. Genom. 8, 80 (2022).

Carlson, K. Working with Bacteriophages: Common Techniques and Methodological Approaches Vol. 1 (CRCPress, 2005).

Goodridge, L., Gallaccio, A. & Griffiths, M. W. Morphological, host range, and genetic characterization of two coliphages. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 5364–5371. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.69.9.5364-5371.2003 (2003).

Zaki, B. M., Fahmy, N. A., Aziz, R. K., Samir, R. & El-Shibiny, A. Characterization and comprehensive genome analysis of novel bacteriophage, vB_Kpn_ZCKp20p, with lytic and anti-biofilm potential against clinical multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 13, 1077995 (2023).

Sambrook, J. & Russell, D. W. Identification of associated proteins by coimmunoprecipitation. Cold Spring Harb. Prot. pdb.prot3898 (2006). (2006).

Andrews, S. FastQC a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data (2010). https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc

Krueger, F. Trim Galore! A wrapper around Cutadapt and FastQC to consistently apply adapter and quality trimming to FastQ files, with extra functionality for RRBS data (2015). https://github.com/FelixKrueger/TrimGalore

Prjibelski, A., Antipov, D., Meleshko, D., Lapidus, A. & Korobeynikov, A. Using spades de Novo assembler. Curr. prot. bioinf. 70, e102 (2020).

Wick, R. R., Schultz, M. B., Zobel, J. & Holt, K. E. Bandage: interactive visualization of de Novo genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 31, 3350–3352 (2015).

Bushnell, B. BBMap short-read aligner, and other bioinformatics tools, Berkeley: University of California (2023).

Richter, M., Rosselló-Móra, R., Glöckner, O., Peplies, J. & F. & JSpeciesWS: a web server for prokaryotic species circumscription based on pairwise genome comparison. Bioinformatics 32, 929–931 (2016).

Alonge, M. et al. Automated assembly scaffolding elevates a new tomato system for high-throughput genome editing. BioRxiv 11, 18–469135 (2021).

Danecek, P. et al. Twelve years of samtools and BCFtools. Gigascience 10, giab008 (2021).

Walker, B. J. et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS One. 9, e112963 (2014).

Garneau, J. R., Depardieu, F., Fortier, L. C., Bikard, D. & Monot, M. PhageTerm: a tool for fast and accurate determination of phage termini and packaging mechanism using next-generation sequencing data. Sci. Rep. 7, 8292 (2017).

Bouras, G. et al. Pharokka: a fast scalable bacteriophage annotation tool. Bioinf 39, btac776 (2023).

Gilchrist, C. L. & Chooi, Y. H. Clinker & clustermap. Js: automatic generation of gene cluster comparison figures. Bioinformatics 37, 2473–2475 (2021).

Adriaenssens, E. & Brister, J. R. How to name and classify your phage: an informal guide. Viruses 9 https://doi.org/10.3390/v9040070 (2017).

Mohd Asri, N. A. et al. Global prevalence of nosocomial multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Antibiot 10, 1508 (2021).

Zbair, M. La résistance bactérienne dans les infections nosocomiales: aspects épidémiologiques, cliniques, thérapeutiques et évolutifs à la réanimation de l’Hopital Aristide Le Dantec (Université Cheikh Anta Diop of Dakar, 2018).

Omari, Y. Le Profil De sensibilité Des Germes Responsables Des Infections Urinaires Nosocomiales Aux antibiotiques,Thèse De Doctorat (Université Cheikh Anta Diop of Dakar, 2018).

Espinoza, H. V. & Espinoza, J. L. Emerging superbugs: the threat of carbapenem resistant Enterobacteriaceae. AIMS microbiol. 6, 176 (2020).

Ndiaye, I. et al. Biofilm formation and whole genome analysis of MDR Klebsiella pneumoniae strains isolated from hospital acquired infections in tertiary hospitals in Dakar, Senegal. J. Bacteriol. Mycol. 11 (2024).

Lourenço, M. et al. Phages against noncapsulated Klebsiella pneumoniae: broader host range, slower resistance. Microbiol. Spectr. e04812–04822 (2023).

Concha-Eloko, R., Barberán-Martínez, P., Sanjuán, R. & Domingo-Calap, P. Broad-range capsule-dependent lytic sugarlandvirus against Klebsiella spp. Microbiol. Spect. 11, e04298–e04222 (2023).

Broeker, N. K. et al. Time-resolved DNA release from an O-antigen–specific Salmonella bacteriophage with a contractile tail. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 11751–11761 (2019).

Pan, Y. J. et al. Klebsiella phage ΦK64-1 encodes multiple depolymerases for multiple host capsular types. J. Virol. 91, 101128jvi02457–101128jvi02416 (2017).

Pan, Y. J. et al. Identification of three podoviruses infecting Klebsiella encoding capsule depolymerases that digest specific capsular types. Microb. Biotechnol. 12, 472–486 (2019).

Hsieh, P. F., Lin, H. H., Lin, T. L., Chen, Y. Y. & Wang, J. T. Two T7-like bacteriophages, K5-2 and K5-4, each encodes two capsule depolymerases: isolation and functional characterization. Sci. Rep. 7, 4624 (2017).

Jończyk, E., Kłak, M., Międzybrodzki, R. & Górski, A. The influence of external factors on bacteriophages–review. Folia Microbiol. (Praha). 56, 191–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12223-011-0039-8 (2011).

Fernández, L., Gutiérrez, D., García, P. & Rodríguez, A. The perfect bacteriophage for therapeutic Applications-A quick guide. Antibiot. (Basel). 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics8030126 (2019).

Manohar, P., Tamhankar, A. J., Lundborg, C. S. & Nachimuthu, R. Therapeutic characterization and efficacy of bacteriophage cocktails infecting Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Enterobacter species. Front. Microbiol. 10, 574 (2019).

Kang, S., Han, J. E., Choi, Y. S., Jeong, I. C. & Bae, J. W. Isolation and characterization of a novel lytic phage K14-2 infecting diverse species of the genus Klebsiella and Raoultella. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1491516 (2025).

Natarajan, S. P., Teh, S. H., Lin, L. C. & Lin, N. T. In vitro and in vivo assessments of newly isolated N4-like bacteriophage against ST45 K62 Capsular-Type Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: vB_kpnP_KPYAP-1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 9595 (2024).

Mulani, M. S., Kumkar, S. N. & Pardesi, K. R. Characterization of novel Klebsiella phage PG14 and its antibiofilm efficacy. Microbiol. Spect. 10, e01994–e01922 (2022).

Das, S. & Kaledhonkar, S. Physiochemical characterization of a potential Klebsiella phage MKP-1 and analysis of its application in reducing biofilm formation. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1397447 (2024).

Liang, B. et al. Effective of phage cocktail against Klebsiella pneumoniae infection of murine mammary glands. Microb. Pathog. 182, 106218 (2023).

Molina-López, J. et al. Characterization of a new lytic bacteriophage (vB_KpnM_KP1) targeting Klebsiella pneumoniae strains associated with nosocomial infections. Virology 110526 (2025).

Peng, X. et al. Isolation, characterization, and genomic analysis of a novel bacteriophage vB_Kp_XP4 targeting hypervirulent and multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front. Microbiol. 16, 1491961 (2025).

Meile, S., Du, J., Dunne, M., Kilcher, S. & Loessner, M. J. Engineering therapeutic phages for enhanced antibacterial efficacy. Curr. Opin. Virol. 52, 182–191 (2022).

Kęsik-Szeloch, A. et al. Characterising the biology of novel lytic bacteriophages infecting multidrug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Virol. J. 10, 1–12 (2013).

Kovacs, C. J. et al. Disruption of biofilm by bacteriophages in clinically relevant settings. Mil Med usad385 (2023).

Verma, V., Harjai, K. & Chhibber, S. Structural changes induced by a lytic bacteriophage make Ciprofloxacin effective against older biofilm of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Biofouling 26, 729–737. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927014.2010.511196 (2010).

Delesalle, V. A., Tanke, N. T., Vill, A. C. & Krukonis, G. P. Testing hypotheses for the presence of tRNA genes in mycobacteriophage genomes. Bacteriophage 6, e1219441. https://doi.org/10.1080/21597081.2016.1219441 (2016).

Yang, J. Y. et al. Degradation of host translational machinery drives tRNA acquisition in viruses. Cell. Syst. 12, 771–779e775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2021.05.019 (2021).

Brzozowska, E. et al. Hydrolytic activity determination of tail tubular protein A of Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteriophages towards saccharide substrates. Sci. Rep. 7, 18048 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors thanks Maïmouna Mbanne Diouf for technical assistance for the Sequencing and all the members of the Pole of Microbiology, Pasteur Institute of Dakar for their precious assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IN, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing | LD, Supervision, Writing – review and editing | OS, Writing – review and editing | AC, Writing – review and editing | BSB, Writing – review and editing | MMD, Methodology, Writing – review and editing | CF, Writing – review and editing | BD, provided strains used, Writing – review and editing | AS, provided strains used, Writing – review and editing | AD, provided strains used, Writing – review and editing | YD, Writing – review and editing | ND, resources, Writing – review and editing | GCM, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review and editing | AS, Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ndiaye, I., Debarbieux, L., Sow, O. et al. Characterization of broad host range bacteriophages vKpIN31 and vKpIN32 against hospital-acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae in Dakar, Senegal. Sci Rep 16, 2587 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32351-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32351-w