Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) remains endemic in Oman, with incidence exceeding 5 per 10⁵ population since 2016 and a rising proportion of cases among expatriates (> 40% of the population). This study investigated the spatiotemporal diversity and structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) in Oman between 2008 and 2022. A total of 735 MTB isolates from nationals and expatriates across provinces were genotyped by spoligotyping and 17-locus MIRU-VNTR; 96 underwent whole-genome sequencing (WGS). Genetic diversity (expected heterozygosity, h) and differentiation (FST) were estimated, and phylogenetic analyses performed. Four major lineages and seven sub-lineages were identified, with similar distributions between nationals and expatriates but temporal variation in spoligotype clades. MIRU-VNTR showed high allelic diversity, with most dominant alleles (76.5%) stable over time, though 32.5% fluctuated. FST values (< 0.05) indicated minimal temporal or local differentiation, except for slightly higher values between Dhofar and other regions. WGS revealed close genetic relatedness between Omani and expatriate isolates and strains from expatriates’ countries of origin, suggesting recent cross-border transmission. MTB in Oman exhibits high genetic diversity with a stable temporal structure. Shared lineages between nationals and expatriates underscore the role of migration, supporting the need for integrated genomic surveillance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is an ancient human disease and remains a global health issue, with its burden ranging from > 500 to < 5 cases per 105 people. In 2021, there were an estimated 10.6 million TB cases and 1.6 million deaths1. Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB), the causative agent, is believed to have co-evolved with humans over centuries2. Molecular studies have shown that MTB is structured into distinct lineages, each with varying geographic specificity, revealing the potential origins of a strain’s ancestry3. This geographic connection is -particularly important in low-incidence countries such as The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, where many TB cases are imported, reflecting how human migration influenced MTB’s genetic diversification4.

The five GCC countries are well positioned to pursue TB eradication as three of them (Oman, UAE and Saudi Arabia) belong to the low incidence category of < 10 per 105 population5,6. Resurgence, however, was observed in recent years in Qatar (34 cases per 105 population) and Kuwait (19 cases per 105 population), and in Oman the incidence hovers below 10 cases per 105 population exceeding the national control target of less than 1 case per 105 population7,8. There is a trend of increasing prevalence of drug- resistant TB among patients with comorbid conditions such as renal failure and HIV, emphasizing the vulnerability of immunocompromised individuals9. The above reflects hidden obstacles to the prospect of TB elimination in the region10. The persistence of TB transmission, in the GCC countries, has been attributed to the common demographic feature of a large proportion of expatriates, from high TB burden countries; comprising > 40% of the total population. The majority of them are often latently infected with TB (LTB), representing a potential source of transmission7,11.

The above hypothesis is supported by the observation of studies that revealed a similar prevalence among non-nationals in different GCC countries9,12. Additional supportive data includes the highly diverse MTB lineages in the GCC countries, and shared genotypes between nationals and expatriates (clusters)8,13,14. These findings indicate a high influx of MTB strains and potential transmission between groups. Similar studies in other regions suggest that human migration drives the diversification of local MTB strains into distinct lineages. Consequently, changes in the expatriate population may lead to shifts in the distribution of MTB genotypes over time.

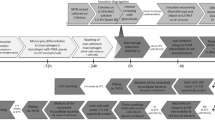

The proportion of expatriates in Oman increased steady between 2008 and 2018, driven by economic growth and labour demand (Fig. 1). Large groups of Asian workers primary, Indian, Bangladeshi, Pakistani, and Sri Lankan, often live overcrowded, occupational-based residential clusters15, representing high risk for TB transmission. The influx of workers from high TB burden countries drives sustained importation of diverse MTB strains, potentially reintroducing transmission chains. Expatriates may carry distinct genetic lineages, including drug-resistant strains uncommon in Oman.

Temporal MTB lineages distribution in Oman, 20,019 − 2018. Figure shows the proportion of spoligotypes categories across each year. No clade data were available for 2008. CAS: The 735 isolates were classified into four major phylogenetic lineages (Lineage 1 – Indo-Oceanic, Lineage 3 – East-African Indian [EAI], Lineage 4 – Euro-American, and Lineage 2 – East-Asian [Beijing]) and assigned to Shared International Types (SITs) using the SITVIT2 database. The most prevalent SIT families were SIT26 (CAS1-Delhi) and SIT11 (EAI3-IND), with fluctuating yearly prevalence. Other less common SIT families included SIT1 (Beijing), SIT42 (LAM9), SIT50 (Haarlem3), and SIT53 (T1). No significant variation in SIT distribution was observed by patient nationality.

Our previous WGS analysis of isolates from Omanis and expatriates provided evidence for cross-transmission between the two groups, though at a limited rate14. This study expands on those findings, conducting a more comprehensive genetic analysis to assess the impact of expatriates on spatiotemporal dynamics on MTB population structure. Such insights are essential for TB control in low-incidence settings like Oman, where a significant share of cases is imported12.

Materials and methods

MTB isolates

The present study examined 735 MTB isolates collected from Omanis (n = 406) and expatriates (n = 329), between 2008 and 2018, from patients in different provinces, in Oman, and processed in the Central Public Health Laboratories (CPHL), Ministry of Health of Oman, which serves as the national center for diagnosis of TB.

During the study period Oman population expanded from 2,867,428 in 2008 to 4,601,706 in 2018 (NCSI, 2024). The proportion of expatriates saw a steady increase between 2008 and 2014 (from 31.4% to 43.7%) (P < 0.001, Spearman’s rho 0.897). However, it remained stable between 2014 and 2018, hovering around 42–45% 16 (Fig. 1).

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Medical Research and Ethics Committee (MREC) of The College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sultan Qaboos University, Oman, under the reference SQU-EC/075/18.

MTB isolates used in the study were obtained from the CPHL. Consent for obtaining and processing the samples was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s). The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical oversight and regulatory framework governing the use of anonymized diagnostic samples for research.

All laboratory works were conducted in Oman, adhering to relevant guidelines and regulations.

Spoligotyping and MIRU-VNTR genotyping

The MTB isolates of both populations were examined for Spacer Oligonucleotide Typing (Spoligotyping) (the classical 43-spacer format) was performed as previously described8.

We queried all spoligotype patterns against the SITVIT2 database to determine their corresponding Shared International Types (SITs)17.

In addition, 17 of the standard 24 MIRU-VNTR18 were analysed. All 24 MIRU-VNTR loci were initially targeted, but only 17 consistently amplified across all isolates; the remaining seven showed weak or sporadic amplification and were excluded from analysis. PCR fragments for each VNTR loci were generated individually, using a fluorescently labelled primer. The size of each PCR product was determined using Applied Biosystems 3130xL Genetic Analyzer, and GeneMapper V-6.0 software (Life Technologies) was used for allele calling. Alleles sizes of each locus were defined in reference to the size of the tandem repeat defined in standard allele-calling table http://www.miru-vntrplus.org.

Whole genome sequencing

MTB lineages in Oman

To explore the hypothesis of gene flow via expatriates from high TB burden countries, we analyzed whole genome sequencing (WGS) of a sub-set of 96 randomly selected MTB isolates from Omanis (n = 23) and expatriates (n = 73) obtained between 2018 and 2022. Library preparation, sequencing, and analysis were performed by Novogene (UK) Company Limited. Library preparation was performed using the NEBNext DNA Library Prep Kit (New England BioLabs, MA, USA). Index codes were added to each sample. The genomic DNA is randomly fragmented to a size of 350 bp. DNA fragments were end polished, A-tailed, ligated with adapters, size selected, and further PCR enriched. Then, PCR products were purified (AMPure XP system), followed by size distribution determination by Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA), and quantification using real-time PCR. The library was then sequenced on a NovaSeq 6000 S4 flow cell with PE150 strategy. The quality of the raw data was assessed with FastQC software version 0.11.8 (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/), and cleaning was performed with Trimmomatic (version 0.39) (Bolger et al., 2014) using the options ILLUMINACLIP with the proper adapter set, and SLIDINGWINDOW:4:20, TRAILING:20, and LEADING:20. Alignment of the cleaned reads to the downloaded reference genome (GCF_000195955.2) was performed with BWA (version 0.7.17)19. SAMtools (version 1.13)20 was used to convert the alignments from SAM to BAM files. SAMtools was also used to calculate the coverage of each sample using the option –coverage. And finally, bcftools (version 1.19)21 was employed to perform the variant calling in all samples using the option --call. Variant calls in VCF format were filtered using VCFtools (version 0.01.16)22to retain only high-quality biallelic. SNPs. Variant subsampling was performed using the vcf random sample function from VCFtools (Danecek et al., 2011). When necessary, format changes were made using the software PGDspider (version 2.1.1.5)23. TB lineages were assigned using TB-Profiler (version 2.8.12) software24.

MTB lineages in related countries

To examine the relatedness of MTB lineages in Oman with those in the country of origin of expatriates, we created a database of publicly available isolates representative of MTB diversity in Bangladesh, Tanzania, the Philippines, India, Egypt, Ethiopia, and Pakistan. We downloaded the raw FASTQs from the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) (Supplementary Table 2) using the software fastq-dump25. Quality control, assembly, and SNP calling were performed as mentioned before.

WGS genomes generated in this study and isolates downloaded from SRA were used to generate a multisample VCF file containing SNP data was converted into FASTA format using PGDSpider v2.1.1.523, with the “VCF to FASTA” option. The resulting FASTA was imported into MEGA X26 and the alignment was performed using the ClustalW algorithm with default parameters. Positions with missing data or SNPs present in only a small subset of samples were excluded after alignment in MEGA. The final alignment was exported to nexus format and imported into SplitsTree4 software (version 4.15.1)25 to generate a Median Network based on the alignment of positions using the uncorrected p-distance and 1000 replicates with SplitsTree4 The robustness of the network splits was evaluated using 1,000 bootstrap replicates, where the alignments were resampled with replacement to estimate support for each split within the network. We applied a ≤ 12 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) difference threshold to infer potential recent transmission, consistent with established cut-offs used in previous M. tuberculosis genomic epidemiology studies27.

Data analysis

Descriptive analysis

Non-parametric correlation was used to assess the correlation between population numbers and time. Wald Chi Square was used to assess the variation in the distribution of spoligotype clades over the years between 2008 and 2018.

Generalized linear binomial regression with a logit link was used to examine temporal variation in MIRU allele proportions between 2008 and 2018, with “year” included as a continuous explanatory variable. The analysis presents as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each year.

Population genetic analysis

The allelic diversity (h) for each MIRU-VNTR was calculated as (h) = n / (n-1) x [1-∑p2], where n is the number of isolates analysed and p is the frequency of an allele at a locus.

We constructed a ‘multi-locus genetic (MLG) profile’ encompassing the entire allelic profile of all MIRUs of MTB isolates, in order to demonstrate genetic relationships between MTB populations from different geographical region.

The genetic differentiation of MTB infecting Omanis and expatriates was then estimated using Wright’s fixation index (FST). To examine whether allele frequencies differ between MTB isolates in different provinces and between MTB collected from Omanis and expatriates, FST indices were calculated using Weir and Cockerham’s method28, estimator of Wright’s F-statistics using the computer package GENEPOP v.4.7.5 web version https://genepop.curtin.edu.au/29,30. A permutation test (n = 10,000) was applied (permuting alleles over populations) to test whether FST indices were significantly different from zero. Low pairwise FST, typically below 0.05, is generally indicative of low genetic differentiation and high gene flow between populations31. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was carried out to examine the genetic similarities between MTB isolates in different provinces using GenALEx Version 6.51b232. The two-dimensional PCoA plot shows the relationships between the multi-locus variants found in the examined populations.

Results

Demographic characteristics of TB cases

We examined MTB isolates collected from expatriates (n = 329, 45%) and nationals (n = 406, 55%) in Oman between 2008 and 2018. The majority of patients were male with a mean age of 40.4yrs, The majority of patients from whom MTB isolates were obtained from patients in three provinces, Muscat (n = 301, 41%), Batinah (n = 159, 22%) and Dhofar (n = 95, 13%) (Table 1).

Diversity and structure of MTB

Spoligotypes diversity

The examined MTB isolates (n = 735) comprised 4 main lineages, including lineage 1 (Indo-Oceanic), lineage 3 (East-African–Indian, EAI), lineage 4 (Euro-American), and lineage 2 (East-Asian, Beijing). Spoligotypes were queried against the SITVIT2 database (Couvin et al., 2019) to determine corresponding Shared International Types (SITs). The distribution of SIT-defined sub-lineages varied significantly across the study years (Wald Chi-Square = 21.043, DF = 9, P = 0.012).

The most prevalent SIT families were SIT26 (CAS1-Delhi) and SIT11 (EAI3-IND), which fluctuated in prevalence from 17.9% in 2015 to 40.0% in 2013, and from 22.2% in 2010 to 41.7% in 2016, respectively (Fig. 2). Other detected SIT families included SIT1 (Beijing), SIT42 (LAM9), SIT50 (Haarlem3), and SIT53 (T1), representing less frequent but globally recognized spoligotype families. No significant change in the distribution of SITs was observed with respect to patient nationality (Wald Chi-Square = 3.268, DF = 1, P = 0.071). The predominance of SIT26 (CAS1-Delhi) and SIT11 (EAI3-IND) corresponds to strain families commonly circulating in South and Southeast Asia, regions that represent major expatriate source populations in Oman.

MIRU-VNTR diversity

A total of 735 MTB isolates, collected between 2008 and 2018, from Omanis (n = 406) and expatriates (n = 329), in different provinces in Oman were successfully typed for 17 MIRU-VNTR loci. Supplementary Table 1 shows the distribution of alleles of the 17 loci. High allelic diversity of MTB was noted in all years (h > 0.5), among isolates obtained from both Omanis (average h = 0.5885) and expatriates (average h = 0.5847).

Binomial regression models were used to assess temporal trends in the common 40 alleles (prevalence of ≥ 10%) of the 17 MIRUs between 2008 and 2018. Overall, 13 (32.5%) alleles exhibited significant fluctuation over time, with 5 alleles (e.g., MTUB39-388, OR = 1.125, 95% CI = 1.068–1.185) increased prevalence, whereas 8 alleles (e.g., MIRU20-584, OR = 0.676, 95% CI = 0.634–0.720) decreased. However, the majority of the remaining alleles (27, 67.5%) showed no temporal fluctuation (Fig. 3). These findings suggest a variable fluctuation in the prevalence of MIRU loci over the observed period.

Effect of time on the MIRU loci proportions. Forest plot of odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals for individual MIRU alleles, derived from binomial regression models assessing temporal trends in allele proportions from 2008 to 2018, with “year” being a continuous explanatory variable. Each point represents the estimated OR for a specific allele, with vertical lines showing the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). ORs < 1 (orange) indicate decreasing frequency over time, ORs > 1 (green) suggest increasing trends, and ORs ≈ 1 (blue) indicate temporal stability.

Temporal and spatial dynamics of MTB

MIRU-VNTR analysis

To investigate temporospatial dynamics of MTB in Oman, FST was estimated using MLG data from the 17 MIRU-VNTR to assess whether the MTB populations, across different years, provinces and between Omanis and expatriates were genetically distinct or homogenously mixed.

A low pairwise FST (< 0.05) was obtained between MTB in different years, 2008–2018, indicative of low genetic differentiation over time. The very low or negative FST value (e.g. -0.0061, -0.0114, -0.0019), indicative of minimal genetic changes over the study period (Table 2). Similarly, very low or negative FST (-0.0002 to 0.0236) was seen between MTB isolated from Omanis and expatriates (Table 3), indicative of minimal variation and gene flow between the two groups.

Moreover, no spatial variation was observed between provinces, FST ranged from − 0.0066 to 0.0187, indicative of homogeneous MTB population in different provinces. The highest FST values were noted between Dhofar (southern Oman, near the Yemen border), and other provinces, such as Dhofar and Sharqiya (FST = 0.0187), Dhofar and Al-Dhahira (FST = 0.0149), Dhofar and Muscat (FST = 00074), suggesting slight divergence of MTB in Dhofar (Table 4).

Comparative WGS analysis of MTB lineages

WGS analysis

To explore the impact of gene flow via expatriates from high TB burden countries, we examined genome sequence of 96 MTB strains collected between 2018 and 2022 in Oman together with publicly available MTB sequences from home countries of expatriates. The number of reads per sample ranged from 295,857 to 42,760,643 sequences, with a mean of 5,486,388 and a median of 2,766,511. Sample coverage ranged from 94.3% to 99.6%, with a mean of 99.05% and a median of 99.50%. Mean depth ranged from 14.03 to 835.63, with a mean of 93.71 and a median of 163.32. A total of 216,465 variants were identified remaining 154,581 after the INDELS removal. From those10% (15421) were randomly selected for perform the phylogenetic analysis. The selected variants were imported into MEGA X26 to generate a multiple sequence alignment using the ClustalW algorithm. Uninformative SNPs and positions containing excessive missing data were removed from the alignment. The resulting dataset, comprising 11,094 high-quality SNPs, was subsequently imported into SplitsTree4 software for phylogenetic network reconstruction.

The phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 4) shows relationships based on SNP distances of MTB isolates collected in Oman (from Omanis n = 23 and expatriates 73) and from expatriate countries (e.g., India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Tanzania, Philippines, Ethiopia, Egypt).

SplitsTree network, estimated with the Median Network method (Huson DH and Bryant D 2006), illustrates the relationships of MTB stains in Oman and countries of origin for expatriates. Samples from Oman are in bold black. Red colors correspond to Asian origins; green colors correspond to African origins. IN denotes India, PK denotes Pakistan, BD indicates Bangladesh, PH denotes Philippines, EG indicates Egypt, TZ designated Tanzania and ET represents Ethiopia. Samples labeled “ind” were produced specifically for this project. To reduce clutter, some labels were omitted for countries with multiple samples in the same n.

Most isolates form a dense central cluster, suggesting a high degree of genetic similarity (differing by ≤ 12 SNPs), with a mix of isolates from Oman and multiple expatriate countries, pointing to shared strains or recent introductions. However, some isolates (e.g., ET_1, IND_6389, H5661.19) appear on long branches, indicating they are genetically distinct from the central population. These may represent more divergent lineages or recently imported strains.

Isolates from some countries (e.g., India, Pakistan, Bangladesh) are spread across the tree, indicating genetic diversity within those populations, while others (e.g., Tanzania, Philippines) appear in more tight-knit clusters, suggesting either clonal expansion or localized strain evolution.

Discussion

MTB in Oman exhibits a high and stable level of genetic diversity revealed by spoligotyping and MIRU-VNTR (h = 0.591), with comparable diversity among both nationals (h = 0.5885 for both). The examined MTB isolates comprised four lineages and seven sub-lineages MTB, with fluctuating prevalence, the common clades, over time. The dominance of SIT26 (CAS1-Delhi) and SIT11 (EAI3-IND) lineages mirrors findings from neighboring Gulf countries and from South and Southeast Asia, reflecting the genetic continuity of MTB strains imported through expatriates from high TB burden countries8. These findings underscore the influence of population mobility on the genetic landscape of MTB in Oman and highlight the value of integrating SIT-based classification for typing MTB strain for global comparability of molecular epidemiological data.

Across 17 MIRUs, multiple alleles were detected, some showing temporal changes, while most remained stable, consistent with low pairwise years FST values between years, indicating a largely homogeneous MTB population. This genetic homogeneity was reflected in similar pairwise FST values between provinces, although slightly elevated differentiation was observed in Dhofar, the southernmost region. Phylogenetic analysis revealed shared clades between Omani and expatriate isolates, suggesting cross-strain circulation and gene flow across demographic groups.

Increasing the resolution from spoligotyping to MIRU-VNTR and WGS reinforced the finding of a genetically diverse but stable MTB population. While isolates initially grouped into seven spoligo clades, each contained unique multi-locus MIRU profiles (Supplementary Table 1), indicating infections stem from multiple unrelated sources rather than clonal expansion or localized outbreaks. These findings align with prior studies14 and reflect the continual influx of individuals from TB-endemic regions and reactivation of latent TB among expatriates12. Similarly high levels of MTB diversity have been reported in other Gulf countries, including Saudi Arabia33, the UAE34, and Kuwait35, characterized by large expatriate populations from high TB-burden countries. The demographic flux across these countries likely contributes to the observed diversity.

Although overall spatial and temporal differentiation was low (Tables 2 and 3) slightly higher FST values between Dhofar and other provinces suggest some degree of genetic differentiation in the south, likely influenced by geographic distance, border proximity, and population movement. Despite this, no clear regional sub-structuring was found, with pairwise FST values across provinces ranging from 0 to 0.0187 (Table 4). This low differentiation suggests high gene flow and large effective population sizes36, consistent with the lack of genetic distinction between MTB infecting Omanis and expatriates (Table 3).

With regard to the relatively low differentiation of MTB in Dhofar exhibited modestly elevated FST values, suggesting tendency to regional genetic differentiation. This may be attributed to geographic isolation, proximity to international borders, or unique migration patterns. Supporting this, SIT1(Beijing) and SIT26 (CAS1-Delhi) lineages, commonly found in South and Southeast Asia, were overrepresented in Dhofar8. The Beijing lineage, in particular, is associated with increased virulence and multidrug resistance37,38. These findings raise the possibility of lineage-specific importation patterns linked to particular expatriate groups or regional epidemiology39. Further longitudinal WGS studies integrating demographic and migration histories are needed to track these trends and determine their epidemiological significance.

However, temporal changes in common alleles of some MIRU-VNTR (Fig. 3) likely reflect a combination of genetic drift, selection pressures (e.g., treatment), or the introduction of new strains via migration or outbreaks. Loci that exhibit changing allele frequencies may serve as useful markers for tracking recent transmission dynamics, while stable loci are useful for lineage identification. These patterns emphasize the value of longitudinal molecular surveillance for capturing shifts in TB population structure driven by demographic changes among expatriates. For example, annual fluctuations of 3–5% in the four largest expatriate groups (Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Egyptian) have been reported16. As these populations cluster geographically, these demographic shifts likely influence local MTB genetic patterns. However, we did not integrate spatial and temporal components into a combined spatiotemporal model, which may provide additional insights into the transmission dynamics. Future studies integrating spatial and temporal data are warranted to better elucidate how regional and temporal factors jointly influence MTB population structure and transmission dynamics.

Whole-genome phylogenies further support a high level of diversity, with most isolates forming a dense central cluster, indicating strong overall similarity, and lacking distinct regional or nationality-based clustering (Fig. 4). Strains from Omanis and expatriates were interspersed across clades, consistent with frequent cross-population mixing. Additionally, phylogenetic ties between Omani strains and those from expatriates’ countries of origin highlight ongoing international transmission dynamics. These findings underscore the influence of labor migration and cross-border mobility on TB epidemiology in Oman and the Gulf region more broadly. Comparable patterns have been observed in France, where historical and modern migration shaped MTB diversity4. There, earlier connections to Eastern Europe and North Africa gave way to more persistent links with Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia, while strains from Asia and sub-Saharan Africa remained distinct indicating limited local transmission from newer migrant communities. Similar dynamics may be unfolding in Oman, emphasizing the need for coordinated regional surveillance and targeted public health strategies.

Although the MTB samples were collected from different provinces across Oman, they may not fully represent the genetic diversity of MTB strains circulating in all governorates. Out of Oman’s 11 governorates, the majority of isolates were obtained from patients in just three governorates, Muscat, Batinah, and Dhofar, which are among the most populated and have the highest TB notification rates. As a result, the spatial distribution of MTB genotypes presented in this study may not reflect the full diversity of strains circulating nationwide, particularly in less populated or more remote regions. Furthermore, the limited number of MTB isolates analyzed by WGS constrains the generalizability of these findings. While the results provide valuable insights into the diversity and transmission dynamics of MTB in the sampled regions, they should be interpreted with caution when extrapolating to the entire country. Future studies with broader geographic coverage and larger sample sizes will be necessary to capture a more comprehensive picture of the genetic structure and transmission dynamics of MTB in Oman.

This study reveals that MTB in Oman exhibits high genetic diversity and temporal stability, as demonstrated by spoligotyping, MIRU-VNTR, and whole-genome sequencing. The low genetic differentiation across years and provinces, along with phylogenetic overlap between strains from Omani nationals and expatriates, points to a largely homogeneous population shaped by diverse sources of infection rather than localized transmission. Regional variation in Dhofar, including a higher prevalence of Beijing and CAS lineages, suggests lineage-specific introductions potentially linked to migration patterns. Temporal shifts in specific MIRU loci further highlight dynamic transmission trends. These findings emphasize the impact of labor migration and regional mobility on TB dynamics in Oman and support the need for sustained molecular surveillance and cross-border public health collaboration. Further longitudinal studies Integrating patient metadata (e.g., demographics, travel history) and WGS may allow monitoring the spread and evolution of drug resistant and/or virulent strains in individual governorates.

Data availability

All relevant data are presented as tables and figures within the main text. The sequence of MTB isolates in Oman have been deposited in SRA under BioProject accession [PRJNA977967] (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA977967) . Supplementary information, including alleles of MIRUs, is available in Supplementary Tables S1, and accession number of sequence obtain form public data bases are given in Supplementary Table 2.

References

WHO. Global tuberculosis report 2021 (2021). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240037021

Brites, D. & Gagneux, S. Co-evolution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and homo sapiens. Immunol. Rev. 264, 6–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/imr.12264 (2015).

Freschi, L. et al. Population structure, biogeography and transmissibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Commun. 12, 6099. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26248-1 (2021).

Barbier, M. et al. Changing patterns of human migrations shaped the global population structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in France. Sci. Rep. 8, 5855. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-24034-6 (2018).

Alawi, M. M. et al. Epidemiology of tuberculosis in Saudi Arabia following the implementation of end tuberculosis strategy: analysis of the surveillance data 2015–2019. Saudi Med. J. 45, 60–68. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2024.45.1.20230424 (2024).

Al Awaidy, S., Khamis, F., Al Mujeini, S., Al Salman, J. & Al-Tawfiq, J. A. Ending tuberculosis in Gulf Cooperation Council countries: an overview of the WHO end TB strategy 2025 milestones. IJID Reg. 16, 100681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijregi.2025.100681 (2025).

Al Abri, S. et al. Tools to implement the world health organization end TB strategy: addressing common challenges in high and low endemic countries. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 92S, S60–S68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.02.042 (2020).

Al-Mahrouqi, S. et al. Dynamics of Mycobacterium tuberculosis lineages in Oman, 2009 to 2018. Pathogens 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens11050541 (2022).

Mokhtar, J. A. et al. Dynamic challenges of active tuberculosis: prevalence and risk factors of Co-Infection in clinical and Microbiological characteristics at King Abdulaziz university Hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Gen. Med. 18, 627–641. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S494516 (2025).

Satista. Incidence rate of tuberculosis in the Gulf Cooperation Council in 2020, by country (2023). https://www.statista.com/statistics/681396/gcc-incidence-rate-of-tuberculosis-inhabitants-by-country

Al Yaquobi, F. & Al-Abri, S. Oman, a pathfinder towards tuberculosis elimination: the journey begins. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 22, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.18295/squmj.2.2022.019 (2022).

Singh, J. et al. Importance of tuberculosis screening of resident visa applicants in low TB incidence settings: experience from Oman. J. Epidemiol. Glob Health. 12, 281–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44197-022-00040-w (2022).

Varghese, B. et al. Admixed phylogenetic distribution of drug resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Saudi Arabia. PLoS One. 8, e55598. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0055598 (2013).

Babiker, H. A. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis epidemiology in oman: whole-genome sequencing uncovers transmission pathways. Microbiol. Spectr. 11, e0242023. https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.02420-23 (2023).

Mansour, S. Spatial concentration patterns of South Asian low-skilled immigrants in oman: A Spatial analysis of residential geographies. Appl. Geogr. 88, 118–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2017.09.006 (2017). https://doi.org/.

Population, N. National Centre for statistics and information- Enhanced Knowledge- Sultanate of Oman (2022). https://data.gov.om/OMPOP2016/population

Couvin, D., Cervera-Marzal, I., David, A., Reynaud, Y. & Rastogi, N. SITVITBovis-a publicly available database and mapping tool to get an improved overview of animal and human cases caused by Mycobacterium bovis. Database (Oxford) (2022). https://doi.org/10.1093/database/baab081

Supply, P. et al. Proposal for standardization of optimized mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit-variable-number tandem repeat typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44, 4498–4510. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01392-06 (2006).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 (2009).

Li, H. et al. The sequence Alignment/Map format and samtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 (2009).

Danecek, P. et al. Twelve years of samtools and BCFtools. Gigascience 10 https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giab008 (2021).

Danecek, P. et al. The variant call format and vcftools. Bioinformatics 27, 2156–2158. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr330 (2011).

Lischer, H. E. L. & Excoffier, L. PGDSpider: an automated data conversion tool for connecting population genetics and genomics programs. Bioinformatics 28, 298–299. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr642 (2012).

Verboven, L., Phelan, J., Heupink, T. H. & Van Rie, A. TBProfiler for automated calling of the association with drug resistance of variants in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One. 17, e0279644. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279644 (2022).

Team., S. T. D. SRA Toolkit: NCBI Sequence Read Archive Toolkit. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), Bethesda, MD, USA. https://github.com/ncbi/sra-tools.

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C. & Tamura, K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1547–1549. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy096 (2018).

Walker, T. M. et al. Whole-genome sequencing to delineate Mycobacterium tuberculosis outbreaks: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 13, 137–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70277-3 (2013).

Weir, B. S. & Cockerham, C. C. Estimating F-Statistics for the analysis of population structure. Evolution 38, 1358–1370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1984.tb05657.x (1984).

Raymond, M. & Rousset, F. GENEPOP (Version 1.2): population genetics software for exact tests and ecumenicism. J. Hered. 86, 248–249. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a111573 (1995).

Rousset, F. Genepop’007: a complete re-implementation of the Genepop software for windows and Linux. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 8, 103–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01931.x (2008).

Latch, E. K., Dharmarajan, G., Glaubitz, J. C. & Rhodes, O. E. Relative performance of bayesian clustering software for inferringpopulation substructure and individual assignment at low levels of population differentiation. Conserv. Genet. 7, 295–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10592-005-9098-1 (2006).

Peakall, R. & Smouse, P. E. GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research–an update. Bioinformatics 28, 2537–2539. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts460 (2012).

Al-Hajoj, S. et al. Current trends of Mycobacterium tuberculosis molecular epidemiology in Saudi Arabia and associated demographical factors. Infect. Genet. Evol. 16, 362–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2013.03.019 (2013).

Ahmad, S. & Fares, E. Genotypic diversity among isoniazid-resistant isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from Rashid hospital in Dubai, united Arab Emirates. Med. Princ Pract. 14, 16–21. https://doi.org/10.1159/000081918 (2005).

Al-Mutairi, N. M., Ahmad, S., Mokaddas, E. & Al-Hajoj, S. First insights into the phylogenetic diversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Kuwait and evaluation of REBA MTB-MDR assay for rapid detection of MDR-TB. PLoS One. 17, e0276487. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0276487 (2022).

Holsinger, K. E. & Weir, B. S. Genetics in geographically structured populations: defining, estimating and interpreting F(ST). Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 639–650. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2611 (2009).

Borrell, S. & Gagneux, S. Infectiousness, reproductive fitness and evolution of drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc Lung Dis. 13, 1456–1466 (2009).

Merker, M. et al. Evolutionary history and global spread of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing lineage. Nat. Genet. 47, 242–249. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3195 (2015).

Dou, H. Y. et al. Associations of Mycobacterium tuberculosis genotypes with different ethnic and migratory populations in Taiwan. Infect. Genet. Evol. 8, 323–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2008.02.003 (2008).

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements. We are grateful to the staff of the Central Public Health Laboratories, MOH, Oman and the Biochemistry Department, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sultan Qaboos University, Oman. The work describe in the manuscript is supported by the Research Council, Oman grant No RC/RG/MED/B/24/184.

Funding

The work describe in the manuscript is funded by the Research Council, Oman grant No RC/RG/MED/B/24/184.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HB, AJ, ABP conceived of the presented idea. LB, prepared and process MTB isolates. RAH, AZ, FG performed laboratory work. SH, AG, carried data analytical methods. ABP, LP, AB supervised genetic and bioinformatic data analysis and interpretation HB, ABP wrote the manuscript with support from AB and LP. AJ, ABK, AK, SA, FY. helped supervise the project and contributed to the design and implementation of the research. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hashim, R.A., Al Zubaidi, A., Al Ghafri, F. et al. Temporal and regional dynamics of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Oman. Sci Rep 16, 2506 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32355-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32355-6