Abstract

The transition towards cleaner fuels is very important due to its potential to reduce greenhouse emissions and favor the decarbonized engine operation. Recently, Ammonia (NH3) has emerged as a promising carbon-free energy carrier and alternative fuel, which can replace traditional fossil fuels. This study aims to showcase the procedure of using NH3 as a primary fuel with 20% Jatropha biodiesel and 80% diesel, designated as JME20 as a pilot fuel in dual-fuel mode. Hence, a single-cylinder DI diesel engine was retrofitted to induct NH3 into the intake manifold, whereas JME20 is being injected and sprayed into the engine cylinder to initiate the combustion. NH3 was inducted at different proportions, such as 8, 10, 12, and 16 lpm, which are designated as DFX, DFX1, DFX2, and DFX3, respectively. Experimentation was carried out at different engine loading conditions, such as 0%, 25%, 50%, 75% and 100%. At each load, the corresponding engine characteristics, namely combustion, performance, and emissions, were measured, compared with standard diesel fuel and given in the paper. Results reveal that a maximum of 24.3% NH3 was replaced for the DFX3 test fuel at full load. Increasing NH3 share will extend the delay period from 10.9°CA to 12.6°CA for 12 lpm (DFX2); and lengthen the combustion duration (CD) from 43.3°CA to 48.3°CA for the same fuel at full load. Moreover, the peak cylinder pressure increased from 55.4 bar to 58.6 bar, also a 6.7% rise in maximum heat release rate and 4.2% improvement in BTE at 12 lpm. A percentage increase in CO & HC emissions by about 54.3% and 51.8% respectively, than diesel at full load. These findings confirm that 12 lpm (DFX2) is the most balanced and optimum condition, validating NH3-JME20 as a promising strategy as a sustainable pathway for agricultural engines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The ever-growing global demand for energy, together with the faster depletion of fossil fuel reserves, has escalated the search for a sustainable and clean source of energy. Traditional fossil fuels are not only limited in nature but also significantly contribute to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and other harmful pollutants, which leads to deteriorate the climate and quality of air. As a result, the agricultural and transportation sectors, which rely heavily on internal combustion (IC) engines, are under tremendous pressure to transition towards cleaner and renewable fuel alternatives1,2,3,4.

In recent decades, several liquid and gaseous alternative fuels like biodiesel, ethanol, biogas, hydrogen, and natural gas have received wide research attention for their utilization in IC engines. Though these fuels have recorded mixed levels of achievements in enhancing combustion efficiency and reducing some emissions, issues like storage, cost, volumetric energy density, and necessity for engine modifications still restrain their large-scale use. Among gaseous fuels, hydrogen has received wide attention owing to its relatively high flame speed and zero carbon emission5,6,7,8. However, the difficulties like low volumetric energy density and storage, necessitate the exploration of other gaseous energy carriers9.

NH3 has recently emerged as a promising carbon-free energy carrier and alternative fuel. High hydrogen content and the ability to release no carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions upon combustion are the most unique characteristics of NH3 to use as a fuel for IC engines. In addition, NH3 can be synthesized using renewable energy via the Haber-Bosch process, making it as an attractive option for future low-carbon energy systems. However, its high auto-ignition temperature, low flame speed, and narrow flammability limits pose significant challenges for its use in conventional engines. To overcome these challenges, strategies such as dual-fuel operation, pilot ignition have been proposed10,11.

Recent research has highlighted the growing potential of using ammonia (NH₃) as an alternative fuel in internal combustion engines. One key investigation12 explored the performance of NH₃ in spark-ignition (SI) engines and demonstrated that while the peak cylinder pressure (PCP) decreased slightly due to NH3’s relatively low flame speed, the overall engine power improved notably. The study also indicated that direct ammonia injection effectively reduced carbon monoxide (CO) emissions but led to higher levels of nitrogen oxides (NOx) and hydrocarbons (HC). These outcomes confirm NH3’s suitability for SI engines, provided that the injection timing and pressure are carefully optimized to control emissions.

In compression-ignition (CI) engines, NH₃ shows even greater promise, largely due to its high energy content and near-zero carbon emissions. Several investigations13 have examined dual-fuel strategies, where NH3 is introduced through the intake while diesel or biodiesel is used as the pilot fuel for ignition. In one such study, Niki et al.14 observed that increasing the ammonia fraction in the intake resulted in a corresponding rise in NH3 emissions. Similarly, Yousefi et al.15 reported a slight drop in thermal efficiency with higher NH₃ substitution but also noted a reduction in NOx emissions, particularly when advanced pilot injection strategies were employed to lower greenhouse gas output. Nadimi et al.16 further showed that up to 84.1% of the engine’s total energy input could be replaced by NH3, leading to a substantial improvement in thermal efficiency and a marked decline in carbon-based emissions, although they emphasized the need for strategies to mitigate increased NOx levels. Complementing these findings, experiments by Kaiyuan Cai et al.17 revealed that incorporating NH3 into diesel combustion prolongs both ignition delay and overall combustion duration.

A significant contribution in this field was made by Liang Zheng and co-workers18, who analyzed the performance behavior of a diesel engine operated with varying ammonia (NH3) blending ratios. Their findings indicated that at higher NH3 shares (around 60%), the engine achieved a peak thermal efficiency of approximately 43.5%, reflecting enhanced combustion quality and lower carbon-based emissions. However, they also emphasized that determining the most suitable NH3 proportion is essential to achieve an effective compromise between NH3 utilization and engine performance. In a related investigation, Liu and Liu19 focused on identifying the optimal NH3 share in a dual-fuel configuration using NH3 and diesel.

Further insight into emission behavior from blended fuels was provided by Reiter and Kong20, who examined the co-combustion of diesel and NH3. In their experiments, vaporized NH3 was introduced through the intake manifold, while diesel was injected into the combustion chamber to initiate ignition. The study employed a constant engine power output while varying the NH3-diesel energy fractions. The most efficient operating condition was observed at diesel/NH3 energy ratios between 40 and 60% and 60–40%. Compared to conventional diesel-only operation, dual-fuel combustion resulted in lower hydrocarbon (HC) and carbon monoxide (CO) emissions. Moreover, when NH₃ contributed less than 40% of the total energy, NOX formation decreased significantly due to the lower combustion temperature. Conversely, when NH3 became the dominant fuel, the nitrogen content contributed to a marked increase in NOx emissions. The use of NH3 also suppressed soot formation because of its carbon-free nature. Cylinder pressure analysis revealed that increasing NH3 content reduced peak pressure and extended the ignition delay period. Overall, the dual-fuel strategy showed lower CO2 and CO emissions than conventional diesel, although high NH3 concentrations (above 60%) were associated with a sharp rise in NOx emissions.

A new combustion strategy for utilizing ammonia in compression ignition (CI) engines was proposed by Lee and Song21 with the objective of lowering NO emissions. Through a series of parametric studies, they validated and analyzed the behavior of an ammonia–diesel dual-fuel engine under different operating conditions. Their work highlighted how variations in the ammonia injection quantity and start of injection (SOI) timing directly influenced NOx formation. It was found that, for fixed ammonia and diesel quantities, NOx emissions were more sensitive to SOI than to engine load, with measured NOx levels dropping from 8500 ppm to 3040 ppm when SOI was optimized. In a related study, Yousefi et al.22 examined the combined effects of ammonia energy fraction and diesel injection timing. They observed a 58.8% reduction in NOx emissions when the ammonia energy share increased from 0% to 40%, though this was accompanied by higher N2O emissions a potent greenhouse gas.

Several investigations have consistently shown that increasing the NH3 substitution fraction reduces peak in-cylinder pressure and shifts the heat release rate (HRR) peak later in the cycle due to slower combustion kinetics. For example, Nadimi et al.16 reported that increasing ammonia substitution to 84% lowered peak cylinder pressure by several bar and lengthened ignition delay by more than 3°CA. These effects were partially countered by advancing pilot injection timing to around 16°CA. Similarly, Reiter and Kong23 found that using 80% ammonia (by energy) significantly delayed HRR and prolonged combustion duration, highlighting the inherently low reactivity of ammonia. Ma et al.24 reported analogous behavior in marine diesel engines, whereas Niki et al.25 observed higher combustion temperatures and reduced N2O emissions during ammonia fumigation though they cautioned that improper dosing could lead to NH3 slip.

Injection strategies and pilot fuel proportions have been identified as key parameters for improving overall performance. Sivasubramanian et al.26 demonstrated that applying a 45% biodiesel pilot injection advanced HRR by approximately 20% toward TDC, shortened ignition delay by 23%, and increased brake thermal efficiency (BTE) to 36.22%, representing a 12.33% gain compared to single injection. Brake specific energy consumption (BSEC) was also reduced by 19.31%. Similar findings were reported by Nadimi et al.27, who achieved over 33% reductions in HC, CO, and smoke emissions, though accompanied by a 36% rise in NOx levels. Furthermore, Jayabal et al.28 observed that moderate ammonia enrichment (6 L min⁻¹) enhanced BTE from 31.1% to 34.8%, largely due to improved mixing and more stable combustion.

Additive-assisted strategies have also been investigated to enhance engine performance with ammonia-based dual fueling. For instance, Pugazhendhi et al.29 observed that introducing 75 ppm of CeO2 nanoparticles into a castor biodiesel–ammonia blend reduced the combustion duration by approximately 3°CA and advanced CA50. This modification led to a 22.2% rise in thermal efficiency for B10 blends and a 26% decrease in brake specific fuel consumption (BSFC), accompanied by a slight increase in NOx emissions of about 4.3%. The catalytic behavior of CeO2 promotes improved oxidation, thereby counterbalancing the efficiency penalties typically associated with high ammonia substitution.

Across multiple studies, emission trends consistently indicate lower CO, HC, smoke opacity, and CO₂ levels when ammonia is used as a co-fuel. This is largely attributed to the absence of carbon in ammonia. For example, Sivasubramanian et al.26 reported reductions of 34% in HC, 39% in CO, and 34% in smoke emissions. However, a recurring issue in these investigations is the increase in NOx emissions, which in some cases reached up to 36%, as highlighted by Jamrozik et al. and Reiter, and Kong13,23. To address this trade-off, advanced control strategies such as optimized injection timing, split injection techniques, and exhaust aftertreatment have been recommended.

A closer examination of the literature on ammonia-fueled diesel engines provides further insights. Numerous researchers30 have employed either diesel or biodiesel as a pilot fuel with ammonia as the main energy source. Findings indicate that cylinder pressure tends to decrease due to ammonia’s lower combustion reactivity and broader flammability range, resulting in a prolonged ignition delay31,32. During this extended delay, a larger quantity of fuel accumulates and undergoes improved vaporization, which eventually increases peak cylinder pressure31,32,33. Studies also show an increase in CO and HC emissions under these conditions34. While some reports noted a significant reduction in NO emissions35, others observed a rise in NO levels36. In contrast, smoke emissions generally exhibited a declining trend with ammonia induction37.

Research gap and objective of this investigation

Although several studies have explored ammonia as a supplementary fuel in SI and CI engines, the majority have focused on automotive applications using diesel as a pilot fuel. Very limited research has addressed NH3 induction in agricultural engines, which are crucial for rural energy security and operate under distinct load profiles. Furthermore, the potential of biodiesel as a sustainable pilot fuel in NH3-assisted dual-fuel engines has not been fully explored. As per the author’s understanding, Jatropha biodiesel (B20) as a pilot fuel was not explored in NH3-fueled diesel engines. To address this gap, the present study investigates the effect of NH3 induction at varying flow rates (8–16 lpm) on the combustion, performance, and emission characteristics of a 4-stroke, DI agricultural diesel engine using JME20 as the pilot fuel. The results are compared against baseline diesel operation to assess the viability of NH3 as a renewable gaseous fuel for agricultural applications.

Methodology and details of the test rig

Test fuels

Diesel was purchased from a retail station of Indian Oil Pvt. Ltd, located near the premises of our campus. On the other hand, Jatropha Methyl Ester (JME) was purchased from Biofuzel International Limited, Madhya Pradesh, India. The properties of JME were measured and compared with the standard diesel fuel, presented in Table 1. The primary fuel (NH3) was also purchased from Sri Varadayini Enterprises, Visakhapatnam, India. JME20 was chosen as the pilot fuel because numerous studies have proved that B20 is the optimum blend that compromises combustion quality and engine compatibility without requiring major modifications.

Experimentation facility

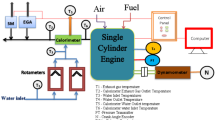

The experimental investigations were performed on a 4-stroke, single-cylinder, naturally aspirated, DI diesel engine that was operated at a constant speed of 1500 rpm. The engine was suitably modified to function in DFO, retrofitted to induct gaseous NH3 through the intake port while injecting JME20 as pilot fuel. An external NH3 supply line also connected to the intake port through a calibrated control valve. A multi hole (venturi based) gas mixing unit was also mounted on the intake port to ensure proper mixing. No alteration was made to the injector, fuel pump, injection timing. This retrofit allows simultaneously NH3 + air during the intake stroke of the engine, enabling DFO. A schematic arrangement of the test facility is illustrated in Fig. 1, and the key specifications of the engine are summarized in Table 2. The complete test rig was procured from M/s. Legion Brothers, Bengaluru, India. Loading was applied and monitored by means of an electrical alternator coupled to the crankshaft through a load cell.

The air flow rate into the engine was quantified using a U-tube manometer in combination with a sharp-edged orifice plate. Fuel consumption was determined by a vertical burette of 30 cm³ capacity, which was fitted with two optical sensors at the upper and lower ends; the effective measurement volume was 20 cm³ between the sensors.

Temperatures at critical points, namely the intake air, exhaust gases, and ammonia line, were monitored with K-type thermocouples. Engine speed was recorded by a non-contact type sensor positioned adjacent to the flywheel. In-cylinder pressure data were acquired at an interval of 0.5° crank angle (°CA) using a piezoelectric transducer (Kistler, Model 5395 A) mounted on the cylinder head. A high-resolution crank angle encoder was employed to detect crank position and the top dead center (TDC). At each operating point, approximately 1050 data points of pressure and volume were recorded per cycle, and the heat release rate (HRR) was obtained by averaging over 20 successive cycles. The output signals from the encoder and pressure sensor were routed through a charge amplifier and subsequently fed into a computer-based data acquisition system (DAS) for analysis and storage.

Exhaust gas emissions were analyzed in accordance with ASTM D6522. During steady operation, the exhaust stream was drawn through a sampling probe, passed through filters, and dehumidified using a condensation trap. The dried sample was then analyzed with a nondispersive infrared (NDIR) analyzer for CO, CO₂, and HC, while NO concentrations were measured with an electrochemical detector. Smoke opacity in the exhaust was determined using an AVL 437 C diesel smoke meter.

Ammonia handling & leakage prevention measures

To prevent NH3 leakage during the experimentation, the NH3 cylinder was equipped with a dual-stage pressure regulator with a check valve. Chemical-resistant PTFE gas lines with compression fittings were employed, and all the joints were tested for leaks before each test using an NH3-detection spray. The test lab was also equipped with a mechanical ventilation system and an NH3 warning sensor. During operation, pressure stability was observed in the induction line, while the purging of the system with fresh air was done before shutdown of the NH3 supply.

Details of the instruments & uncertainty analysis

The assessment of uncertainty analysis is crucial for measuring the accuracy of an instrument, and was carried out using the formulae as given in38. Table 3 portrays the list of uncertainties in the instruments used for this study.

Where, UR refers to the uncertainty of the estimated parameter at 95% confidence level. While AR indicates the systematic and BR refers to random uncertainties.

In the above relation, R is the estimated parameter that relies on the variable Xi. The symbols Ai and AR represent the measurement level and uncertainty in R, respectively.

By performing the repeatability of the experiments, the uncertainty for the parameters EGT, BSFC, BTE, HC, CO, NO, and smoke density was calculated as,

Ammonia energy share

In DFO, the energy share of gaseous fuel is an important parameter when analysing the impact of premixed combustion. In order to produce some power, both the gaseous fuel or primary fuel (NH3) and the pilot fuel (JME20) should contribute energy. It is also noted from the figure that the pilot fuel consumption varies with the load, whereas the primary fuel remains unchanged with the change in load. It is also understood that the energy share is a strong function of rate of fuel consumption and calorific value. The below formulae shown the calculation of energy share, where mpilot fuel, CVpilot fuel and \(\:{\text{m}}_{{NH}_{3}}\), \(\:\text{C}{\text{V}}_{{NH}_{3}}\) represent the mass of fuel consumption and calorific value of pilot and primary fuels, respectively. The energy ratio of NH3 at different engine loads is given in Table 4 for the test fuels such as DFX, DFX1, DFX2, and DFX3.

The energy share of \(\:{NH}_{3}\) was calculated using the following formulae39;

Where;

Also, the excess air ratio can be defined as;

Figure 2 displays the relation between NH3 energy share and λ (lambda) at different engine loads. The energy share values of NH3 range from 54.6% to 6.7% (no load to full load). The energy share was high at no load and low at full load. Combustion might not be as effective, particularly at no load, which would mean the air-fuel mixture won’t burn properly, and hence more amount of fuel is required to produce the power. As the NH3 energy share increases, the λ value decreases, indicating a transition towards a richer air-fuel mixture. At load 0%, λ starts at its highest value, around 2.0, and decreases to 1.0 as the NH3 energy share approaches 50%. At load 25%, λ drops from 1.8 to approximately 1.2, and at Load 50%, it continues to decline from 1.5 to around 0.8. For load 75%, the decrease in λ becomes less pronounced, indicating a reduced sensitivity to ammonia energy share at higher loads, and at load 100%, λ reaches its lowest point, from 0.7 to 0.4, corresponding to the highest ammonia energy share. This trend highlights the effect of NH3 fumigation on combustion characteristics, with higher ammonia flow rates leading to a richer fuel-air mixture and optimized combustion at higher engine loads. The figure demonstrates the decreasing λ values across all loads, signifying the influence of ammonia energy share on the combustion process, particularly under varying engine load conditions. During the entire engine operation, the DFX3 shows the maximum energy share when compared to other flow rates used for this study. The energy share in % for different flow rates was found to be 6.7%, 12.3%, 18.2% and 24.3% for DFX, DFX1, DFX2, and DFX3 respectively, at full load.

Results and discussions

Assessment of combustion parameters

P-Ɵ analysis

Cylinder pressure when measured as a function of crank angle (P-Ɵ curve) gives the real-time behavior of combustion inside the engine. It enables the determination of ignition delay, combustion phasing, and heat release rate (HRR) characteristics, which are very essential for evaluating engine performance. Figure 3 portrays the P-Ɵ curve for different test fuels used in this study. It is observed from the figure that diesel exhibits a higher peak pressure than the other test fuels used in this study. This might be due to the higher calorific value of diesel. It can be noted that the commencement of ignition for diesel is at 348.5°CA, whereas for B20, the ignition occurs 1.5°CA earlier. This is due to the presence of O2 bounded molecule in the biodiesel, which favors for earlier combustion. The PCP of diesel and B20 at full load are 62.8 bar and 61.7 bar, which occur at 10.08°CAaTDC and 7.7°CAaTDC, respectively. The lower peak value of B20 is due to the lower heating value of the fuel. In DFO, with an increase in the flow rate of ammonia, the peak pressure also increases. The lower combustion rate and slow flame speed of NH3 favors the ignition delay to prolong, which results in higher cylinder pressure in the premixed phase of combustion. PCP of DFX, DFX1, DFX2, and DFX3 are 61.8 bar, 55.41 bar, 56.56 bar, 58.72 bar, and 56.47 bar, occurred at 10.6°CAaTDC, 11.8°CAaTDC, 13.04°CAaTDC, and 15.42°CAaTDC, respectively, at full load.

The presence of ammonia did not significantly affect the peak pressure, but a variation in ignition delay and peak pressure shift towards the expansion process is observed. The reason stated here is in good agreement with the reason explained by Nadimi et al.16 in the experimentation conducted using different proportions of NH3 in a diesel engine.

HRR analysis

HRR analysis for diesel, B20, and all the dual fuel operations was calculated by using the first law of thermodynamics, which is given below40;

From the above equation, all the right-hand terms can be easily derived with the pressure history data. The left-hand terms represent the net heat release rate in J/°CA. The HRR is a vital tool to find out the combustion duration and the delay period, which are the two basic parameters through which the combustion phenomenon can be easily identified41.

The HRR in the premixed phase of combustion depends on several factors like ignition delay, mixture formation, and combustion rate. Figure 4 depicts the variation of HRR with respect to crank angle for different test fuels. At full load, the HRR for diesel is 56.4 J/°CA, whereas for B20 it is 54.4 J/°CA. In single fuel operation (Diesel and B20), a sharp HRR peak is noticed, which is a characteristic of rapid premixed combustion. It is observed from the figure that diesel exhibits a higher peak due to its high volatility and calorific value. Though B20, an oxygenated fuel, shows a slightly lesser HRR peak due to its lower heating value and slower vaporization. However, the HRR curve for the ammonia/biodiesel dual fuel mode differs because of the high premixed NH3-air ratio. Therefore, as the NH3 flow rate increases from 8 to 12 lpm, a rise in the HRR peak is observed. Specifically, the peak HRR values are 51.1 J/°CA, 52.7 J/°CA, and 54.4 J/°CA for 8 lpm, 10 lpm, and 12 lpm, respectively, at full load. This increase in peak HRR corresponds to the higher amount of fuel available in the combustion chamber due to prolonged ignition delay, allowing more premixing and a more intense premixed combustion phase. Further, the combustion in dual fuel operation is retarded due to the lower combustion rate of ammonia. However, at DFX3 operation (16 lpm), the HRR peak drops back to 51.7 J/°CA. This reduction is attributed to the excessive presence of NH3 in the combustion chamber, which suppresses the overall combustion rate. On the other hand, the expansion pressure is slightly higher for the DFM case due to the late combustion of NH3.

The earlier mentioned reason was documented by Nadimi et al.16 in their experimentation while pointing out HRR. It is also noticed that DFX2 exhibits a higher HRR of about 3.8% than DFX, 0.8% than DFX1, and 2.4% than DFX3 at full load.

Ignition delay

The variation of ignition delay (ID) with engine load for diesel, JME20, and all DFOs is shown in Fig. 5. ID is the time or crank angle period calculated in degrees crank.

angle between the start of injection (SOI) and the start of combustion (SOC) of the mixture.

42,43. The factors which affect ID are fuel properties, in-cylinder pressure and temperature, air-fuel ratio and charge composition, injection timing, and pressure42,44,45. For all test fuels, ID decreases with increasing load due to a rise in in-cylinder temperature, which accelerates fuel-air reactions. At full load, the ID for diesel and B20 was measured as 11.5°CA and 10.5°CA, respectively. The shorter ID of B20 compared to diesel is attributed to its higher cetane number and oxygenated nature.

In DFO, ID was consistently higher than the baseline diesel operation across all loads. For example, at 50% load, the ID for DFX3 was approximately 0.7°CA longer than diesel. This extension is primarily due to the high autoignition temperature, slow flame speed, and dilution effect of NH3, which reduces the O2 concentration in the charge. Another reason might be due to the known ignition-resistant nature of NH3, which demands higher temperatures and longer residence time to initiate combustion. This reason was mentioned by46 in the experimentation carried out using NH3. The ID increased progressively with an increase in NH3 flow rates, with DFX3 showing the maximum ID across the load spectrum. At full load, ID values of DFX, DFX1, DFX2, and DFX3 are 10.9°CA, 11.2°CA, 11.4°CA, and 11.8°CA, respectively at full load.

Combustion duration (CD)

Figure 6 shows the variation of combustion duration with engine load for diesel, JME20, and dual-fuel (NH3 + JME20) operations. CD refers to the crank angle interval between the SOC and the end of combustion (EOC). It reflects how long the fuel-air mixture takes to release most of its chemical energy and is a key parameter affecting engine performance, efficiency, and emissions. From the figure, it is observed that CD generally increases with load for all test fuels. At higher loads, more fuel is injected, leading to increased mixing and combustion phases that take a longer time to complete, thus extending the combustion duration. Among the fuels tested, JME20 exhibits the shortest CD across all load conditions. This can be attributed to its higher O2 content and better combustion reactivity, which support faster flame propagation and more complete combustion in a shorter period. In contrast, diesel shows slightly longer CD than JME20 due to its relatively slower burning rate and lack of inherent O2 content in the fuel.

In DFM, CD is significantly longer than both diesel and JME20. This is due to the presence of NH3, which has a low flame speed, high ignition resistance, and requires higher energy for sustained combustion. As NH3 concentration increases (i.e., from 8 to 16 lpm), the combustion process becomes slower and more diffused, resulting in a longer duration. The reduced O2 availability in the intake mixture, because NH3 displaces part of the intake air, also contributes to slower combustion kinetics. This reason mentioned here is aligned with the reason documented by18 in the experimentation carried out using NH3 fueled diesel engines. At full load, the CD for the test conditions of diesel, JME20, DFX (8 lpm NH3), DFX1 (10 lpm NH3), DFX2 (12 lpm NH3), and DFX3 (16 lpm NH3) are 43.3°CA, 42.1°CA, 45.2°CA, 46.1°CA, 47.2°CA, and 48.3°CA respectively. It is seen that the longest CD occurs at the highest NH3 flow rate (16 lpm), confirming the retarding effect of NH3 on flame propagation.

Assessment of performance parameters

Brake thermal efficiency (BTE)

Figure 7 depicts the variation of BTE with engine load at different test fuels used in this study. It is obvious that BTE increases with the load, due to an increase in the cylinder temperature at higher loads. B20 exhibits slightly lower BTE when compared to diesel at all engine loading conditions due to higher viscosity, low calorific value, and slower evaporation46,47. The BTE values of sole diesel and B20 operations are about 29.8% and 27.2% at full load. In the case of DFM, BTE tends to reduce with a higher NH3 share at all engine loads.

For the same pilot fuel (B20), a drop in BTE is observed in the DFM of about 3.5% for DFX2 when compared to diesel operation at full load. This decrease in BTE in DFO is due to the induction of more amount of NH3 into the intake manifold, replacing some part of the O2 concentration and resulting in a decrease in fuel conversion efficiency. Another reason might be that of lower combustion speed and lower flame propagation velocity of NH3 lead to higher heat loss to the cylinder walls and cooling system before all the fuel is completely burned. This reduces the amount of heat available to do useful work on the piston, decreasing the BTE in DFO. These observations agree with earlier findings46, where NH3 is being substituted with biodiesel in a diesel engine. The BTE of diesel is 29.8%, whereas it is 26.5%, 25.3%, 24.2% and 21.1% for DFX, DFX1, DFX2, and DFX3, respectively, at full load. In DFM, a drop in BTE of about 6.6%, 10.9%, 14.7% and 25.7% for DFX, DFX1, DFX2, and DFX3, respectively, than that of diesel operation at full load.

Brake specific fuel consumption (BSFC)

BSFC is a measure of the fuel efficiency of an engine in terms of fuel consumption per unit of power produced. It is typically expressed in units like kilograms per kilowatt-hour (kg/kWh). The factors affecting BSFC are like engine design and type, operating temperature, type of fuel, and quality, etc. The variation of BSFC with engine load for diesel, JME20, and dual fuel operations is shown in Fig. 8.

For all test fuels, BSFC decreased as the load increased because of better combustion temperature and reduced relative heat losses. At full load, diesel achieved the minimum BSFC of about 0.29 kg/kW-hr, whereas B20 showed 0.33 kg/kW-hr, reflecting its lower heating value. BSFC for dual-fuel cases was consistently higher than that of diesel. At 50% load, DFX3 (16 lpm NH3) recorded 0.54 kg/kW-hr, approximately 58.8% higher than diesel. This increase is mainly due to NH3 having a lower energy density than diesel fuel. As the proportion of NH3 increases, the overall energy density of the fuel blend decreases. This can lead to higher BSFC because more fuel is needed to produce the same amount of work. The other reason is due to low calorific value and poor auto-ignition quality of NH3, which lengthens ID and displaces part of the intake air. At higher loads, elevated cylinder temperature improved NH3 oxidation, slightly reducing the BSFC relative to diesel. At full load, the BSFC values for diesel, DFX, DFX1, DFX2, and DFX3 are 0.29 kg/kW-hr, 0.35 kg/kW-hr, 0.38 kg/kW-hr, 0.41 kg/kW-hr, and 0.45 kg/kW-hr, respectively.

Exhaust gas temperature (EGT)

EGT in a diesel engine refers to the temperature of the gases exiting the combustion chamber and entering the exhaust system. It is a critical parameter because it reflects the efficiency of the combustion process and has implications for engine performance, emissions, and the durability of engine components. The trend of EGT with respect to engine load for diesel, B20, and dual fuel operations is shown in Fig. 9. For all test fuels, EGT steadily increased with load due to higher in-cylinder temperatures and greater energy release at higher engine loads. B20 exhibited the highest EGT at all loads, followed closely by diesel, owing to pre-bonded O2 molecules in biodiesel. At full load, the EGT of diesel and B20 is 335℃ and 355℃, respectively.

In dual-fuel operation with NH3 consistently resulted in slightly lower EGT compared to both diesel and B20 at all loads. This behavior is attributed to ammonia’s lower adiabatic flame temperature, slower burning rate, and its dilution of the intake charge, which together reduce peak gas temperatures. In other words, the combustion temperature decreases with higher NH3 content; thus, the temperature of the exhaust gases exiting the engine is also likely to decrease. The EGT values of DFX, DFX1, DFX2, and DFX3 are 338℃, 327℃, 311℃, and 285℃, respectively, at full load. It is worthwhile to note that the EGT for DFX3 is 14.9% lower than for pure diesel operation.

Assessment of emission parameters

Carbon monoxide emissions

CO emissions from a diesel engine refer to the amount of CO2 gas released into the atmosphere as a byproduct of the incomplete combustion of diesel fuel. CO is a colorless, odorless gas that is harmful to human health and contributes to air pollution. The prominent factors affecting CO emission are air-fuel ratio, fuel injection parameters, compression ratio, type of fuel/fuel properties, and O2 availability, etc. Figure 10 depicts the variation of CO emission with respect to engine load for diesel, B20, and dual-fuel operations. For all test fuels, CO emissions decreased steadily with increasing load, owing to high in-cylinder temperatures. Notably, B20 consistently emits lower CO levels than diesel at all loads; this improvement is attributed to the inherent O2 content of JME, which enhances oxidation of intermediate species.

In DFO, with an increase in the NH3 share, CO emissions tend to increase at all engine loading conditions. The rise in CO emission is a strong function of ignition-resistance and slower kinetics of NH3, which hinders the oxidation of CO species. NH3 induction into the intake port also reduces part of local O2 availability, forming a fuel-rich regions around the pilot spray. Hence, these regions experience an incomplete combustion, results to a rise in CO emissions48. Among all the DFOs, the DFX3 (16 lpm NH3) exhibited the highest CO levels. The CO emission values for diesel, B20, DFX, DFX1, DFX2 and DFX3 are 2.28 g/kWh, 2.12 g/kWh, 2.47 g/kWh, 2.91 g/kWh, 3.3 g/kWh, and 3.5 g/kWh respectively at full load. A percentage increase in CO emission of about 8.3%, 27.6%, 44.7% and 53.5% for DFX, DFX1, DFX2, and DFX3 operations, respectively, when compared to diesel at full load.

Unburnt hydrocarbon emissions

HC emissions from a diesel engine refer to the release of unburned or partially burned hydrocarbons into the atmosphere. Hydrocarbons are organic compounds composed exclusively of carbon and hydrogen atoms, and their emission from diesel engines contributes to air pollution and can have adverse effects on human health and the environment. The parameters that affect HC emission are incomplete combustion of fuel, fuel properties, and fuel injection parameters, etc49. Figure 11 depicts the variation in CO emissions with engine load for diesel, B20, and dual-fuel operations. For all the test fuels, HC emission decline as load increases because of higher combustion temperature and turbulence enhance oxidation of unburned fuel. Diesel consistently exhibited the higher HC levels when compared to B20; this improvement in B20 is attributed to the oxygenated nature of B20, which promotes more complete combustion and hence reduces HC emissions.

The HC emissions values for diesel and B20 are 0.027 g/kWh and 0.019 g/kWh respectively at full load. In contrast, DFO exhibits higher HC emission when compared to diesel at all engine loading conditions. The increase in HC emissions is mainly due to key characteristics of NH3 such as lower flame temperature, slow flame speed, narrow flammability limits. This can be explained by the fact that, when NH3 replaces part of pilot fuel, the overall mixture temperature is reduced, preventing from complete oxidation. Moreover, the lower reactivity and narrow flammability limits also leads to a partial combustion, leaving a larger portion of crevice hydrocarbons unoxidized. The latter reason was documented by46 in the experimentation on a diesel engine using NH3 as a primary fuel. The HC emission values for DFX, DFX1, DFX2 and DFX3 are 0.024 g/kWh, 0.029 g/kWh, 0.035 g/kWh, 0.041 g/kWh respectively at full load.

Nitric oxide

NO formation in a CI engine can be greatly affected by cylinder temperature, O2 concentration, residence time. Figure 12 portrays the variation of NO emission with respect to engine load for diesel, B20, and dual-fuel operations. For all the test fuels, NO emissions steadily decline as load increases because the higher fuel-to-air ratio lowers the O2 availability per unit fuel and reduces peak flame temperature. But, B20 exhibits higher NO emission compared to diesel, reflecting its O2 content that enhances combustion temperature. The values of NO emissions for diesel and B20 are 2.9 g/kWh, 3.4 g/kWh respectively, at full load.

Though NH3 contains fuel-bound N2, NO emissions are found to be decreased with increase in NH3 flow rate. This trend is primarily due to NH3’s strong charge-dilution effect, which reduces the O2 percentage in the cylinder, thereby reduces the adiabatic flame temperature. Further, this trend can also be proven by the two dominant factors of thermal NO formation, suggested by Zeldovich mechanism. The slower reactivity and lower flame temperature of NH3 delayed the combustion process and shifted the heat release towards the expansion side. Because of this, the residence time and temperature are not sufficient for significant NO formation. The values of NO emission for diesel, B20, DFX, DFX1, DFX2 and DFX3 are 2.9 g/kWh, 3.4 g/kWh, 3.1 g/kWh, 2.8 g/kWh, 2.4 g/kWh, and 1.9 g/kWh respectively at full load.

Smoke opacity

Smoke emission from a diesel engine refers to the visible particulate matter (PM) that is released into the atmosphere as a result of the incomplete combustion of fuel. The variation of smoke emission with respect to engine load for diesel, B20, and dual-fuel operations is shown in Fig. 13. Smoke emission increases steadily with an increase in load for all test fuels, because higher load enhances fuel quantity and rich zones, favouring soot formation. However, B20 exhibits slightly lower values owing to its inherent O2 content that improves oxidation of soot precursors.

In DFM, introducing NH3 further suppresses smoke emissions across all load range, with the maximum reduction observed at DFX3. This can be explained by the carbon-free nature of NH3, which lowers the amount of carbon available for soot nucleation and to better premixing at higher flow rates. In other words, due to the induction of gaseous NH3 by premixed combustion and reducing the amount of carbon in the mixture decreases the soot formation. The latter reason mentioned here is in good accordance with the reason mentioned by. Cheng et al.46. However, the further decrease in smoke emission from DFX2 to DFX3 is minimal, implying that most of the benefit is achieved at moderate induction levels.

Conclusion

This study systematically evaluates the effect of NH3 induction on combustion, performance, and emission characteristics of a DI diesel engine operated on DFM using JME20 as a pilot fuel. The following key conclusions are drawn from this study;

-

As the NH3 energy share increases, the λ value decreases, indicating a transition towards a richer air-fuel mixture. A maximum of 24.3% pilot fuel replacement was found for DFX3 at full load.

-

With an increase in the flow rate of NH3, the peak pressure also increases. The lower combustion rate and slow flame speed of NH3 favours the ignition delay to prolong, which results in higher cylinder pressure in the premixed phase of combustion. PCP of DFX, DFX1, DFX2, and DFX3 are 61.8 bar, 55.41 bar, 56.56 bar, 58.72 bar, and 56.47 bar, occurred at 10.6°CAaTDC, 11.8°CAaTDC, 13.04°CAaTDC, and 15.42°CAaTDC, respectively, at full load.

-

HRR also increases with an increase in the flow rate of NH3. Interestingly, at DFX3 operation (16 lpm), the HRR peak drops back to 51.7 J/°CA. This reduction is attributed to the excessive presence of NH3 in the combustion chamber, which suppresses the overall combustion rate.

-

BTE decreases steadily with the increase in flow rate of NH3. A drop in BTE of about 6.6%, 10.9%, 14.7% and 25.7% for DFX, DFX1, DFX2, and DFX3, respectively, then that of diesel operation at full load.

-

Both the ID and CD increase continuously with an increase in the flow rate of NH3. This is due to the presence of NH3, which has a low flame speed, high ignition resistance, and requires higher energy for sustained combustion.

-

As the NH3 flow rate increases, it displaces part of the pilot fuel, and because of its low reactivity, the premixed NH3-air charge may not burn completely, leading to a reduction in the effective quantity of diesel undergoing combustion. Hence, both the CO and HC emissions increase. A percentage increase in CO & HC emission of about 44.7% and 29.6% for DFX2 test fuel, respectively, when compared to diesel at full load.

-

NO emissions decreased progressively till DFX3, suggesting that the dilution and cooling effects of ammonia outweighed the additional fuel-bound nitrogen across the test range.

In summary, the test results indicate that NH3-JME20 operation is technically feasible for agricultural diesel engines, provided the NH3 replacement is carefully optimized. Among the test fuels, DFX2 (12 lpm) exhibited the most favorable combustion stability. Though NH3 flow rates resulted in longer delay and reduced efficiency, future work may also be explored at considering optimization of injection timing (to compensate for NH3’s slow reactivity), aftertreatment for CO/HC control, and real-time monitoring of NH3 slip. Additionally, the emission insights presented in this study provide qualitative environmental relevance. Future work will focus on quantitative environmental and enviro-economic assessment, incorporating CO–HC–NO–CO₂–PM impact factors, monetary damage cost functions, and ammonia-slip diagnostics based on methodologies reported in the literature50,51,52,53. This will extend the present combustion-emission baseline toward sustainability-level evaluation.

Data availability

The data will be made available upon request to the corresponding authors.

Abbreviations

- BTE:

-

Brake Thermal Efficiency

- BSFC:

-

Brake Specific Fuel Consumption

- CI:

-

Compression Ignition

- CD:

-

Combustion Duration

- CO:

-

Carbon monoxide

- CV:

-

Calorific Value

- CO2 :

-

Carbon Dioxide

- DF:

-

Dual Fuel

- DFO:

-

Dual Fuel Operation

- GHG:

-

Greenhouse Gas

- HC:

-

Hydrocarbon

- HRR:

-

Heat Release Rate

- IC:

-

Internal combustion

- ID:

-

Ignition Delay

- JME:

-

Jatropha Methyl Ester

- lpm:

-

Liter per minute

- MCP:

-

Maximum Cylinder Pressure

- MHRR:

-

Maximum Heat Release Rate

- NO:

-

Nitric oxide

- NH₃:

-

Ammonia

- PCP:

-

Peak Cylinder Pressure

- SI:

-

Spark-Ignition

- SOI:

-

Start of Injection

- TDC:

-

Top Dead Centre

- Λ:

-

Equivalence ratio

References

Sharifishourabi, M., Dincer, I. & Mohany, A. An innovatively designed community-based hybrid energy system to generate its needs of electricity, heat, hot water and hydrogen in a sustainable manner. Sustain. Cities Soc. 129, 106489. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SCS.2025.106489 (2025).

Reddy, V. J., Hariram, N. P., Maity, R., Ghazali, M. F. & Kumarasamy, S. Sustainable Vehicles for Decarbonizing the Transport Sector: A Comparison of Biofuel, Electric, Fuel Cell and Solar-Powered Vehicles. World Electr. Veh. J. 15, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/WEVJ15030093 (2024).

Pandey, P. KK, KhayumN & ShaikJH Comparison of machine learning algorithms on a low heat rejection diesel engine running on ternary blends. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy. 16 https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0230274/3315184 (2024).

Khayum, N., Anbarasu, S. & Murugan, S. Optimizing waste heat recovery in a dual-fuel diesel engine through thermoelectric generation and heat pipe integration. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy. 16 https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0237606/3328429 (2024).

Falfari, S., Cazzoli, G., Mariani, V. & Bianchi, G. M. Hydrogen application as a fuel in internal combustion engines. Energies 16, 2545. https://doi.org/10.3390/EN16062545 (2023).

Khayum, N., Anbarasu, S. & Murugan, S. Experimental investigation of a Biogas-Fueled diesel engine at different. Biogas Flow. Rates 2021:913–921. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-5955-6_87

Sateesh Kumar, C. et al. Performance and Emission Analysis of a Diesel Engine Fueled with Cashew Nut Shell-Derived Biodiesel and Its Blends. Eng. Proc. 114, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ENGPROC2025114016 (2025).

Shaik, J. H., Khayum, N. & Pandey, K. K. Analysis of combustion characteristics of a diesel engine run on ternary blends using machine learning algorithms. Environ. Prog Sustain. Energy. 44, e14582. https://doi.org/10.1002/EP.14582 (2025).

Hossain Bhuiyan, M. M. & Siddique, Z. Hydrogen as an alternative fuel: A comprehensive review of challenges and opportunities in production, storage, and transportation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 102, 1026–1044. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJHYDENE.2025.01.033 (2025).

Awad, O. I., Zhou, B., Harrath, K. & Kadirgama, K. Characteristics of NH3/H2 blend as carbon-free fuels: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 48, 38077–38100. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJHYDENE.2022.09.096 (2023).

Alnajideen, M. et al. Ammonia combustion and emissions in practical applications: a review. Carbon Neutrality. 3, 1–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/S43979-024-00088-6/FIGURES/38 (2024).

Sharma, V., Panesar, A., de Sercey, G. & Begg, S. A review of ammonia combustion and emissions characteristics in spark-ignition engines and future road map. Energies 2025 18, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/EN18010041 (2024).

Jamrozik, A., Tutak, W., Pyrc, M. & Grab-Rogaliński, K. Experimental study on ammonia-diesel co-combustion in a dual-fuel compression ignition engine. J. Energy Inst. 115, 101711. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JOEI.2024.101711 (2024).

Niki, Y. Experimental investigation of effects of split Diesel-Pilot injection on emissions from Ammonia-Diesel dual fuel engine. Proc. ASME 2021 Intern. Combust. Engine Div. Fall Tech. Conf. ICEF 2021. https://doi.org/10.1115/ICEF2021-66341 (2021).

Yousefi, A., Guo, H., Dev, S., Lafrance, S. & Liko, B. A study on split diesel injection on thermal efficiency and emissions of an ammonia/diesel dual-fuel engine. Fuel 316, 123412. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FUEL.2022.123412 (2022).

Nadimi, E., Przybyła, G., Lewandowski, M. T. & Adamczyk, W. Effects of ammonia on combustion, emissions, and performance of the ammonia/diesel dual-fuel compression ignition engine. J. Energy Inst. 107, 101158. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JOEI.2022.101158 (2023).

Cai, K. et al. Combustion Behaviors and Unregular Emission Characteristics in an Ammonia–Diesel Engine. Energies, 16, 7004. (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/EN16197004

Zheng, L. et al. Experimental study on the combustion and emission characteristics of ammonia-diesel dual fuel engine under high ammonia energy ratio conditions. J. Energy Inst. 114, 101557. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JOEI.2024.101557 (2024).

Liu, J. & Liu, J. Experimental investigation of the effect of ammonia substitution ratio on an ammonia-diesel dual-fuel engine performance. J. Clean. Prod. 434, 140274. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2023.140274 (2024).

Reiter, A. J. & Kong, S. C. Demonstration of compression-ignition engine combustion using ammonia in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Energy Fuels 22, 2963–2971. https://doi.org/10.1021/EF800140F;CTYPE:STRING:JOURNAL. (2008).

Lee, D. & Song, H. H. Development of combustion strategy for the internal combustion engine fueled by ammonia and its operating characteristics. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 32, 1905–1925. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12206-018-0347-X/METRICS (2018).

Yousefi, A., Guo, H., Dev, S., Liko, B. & Lafrance, S. Effects of ammonia energy fraction and diesel injection timing on combustion and emissions of an ammonia/diesel dual-fuel engine. Fuel 314, 122723. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FUEL.2021.122723 (2022).

Reiter, A. J. & Kong, S. C. Combustion and emissions characteristics of compression-ignition engine using dual ammonia-diesel fuel. Fuel 90, 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FUEL.2010.07.055 (2011).

Ma, Y. et al. Combustion and emission characteristics of ammonia-diesel marine high pressure direct injection low-speed dual-fuel engine. Sci. Rep. 15, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-025-04997-Z;SUBJMETA=166,4063,4077,4082,4107,639,988;KWRD=DIESEL+FUEL,MECHANICAL+ENGINEERING,THERMOELECTRIC+DEVICES+AND+MATERIALS (2025).

Niki, Y., Nitta, Y., Sekiguchi, H. & Hirata, K. Diesel fuel multiple injection effects on emission characteristics of diesel engine mixed ammonia gas into intake air. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power. 141. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4042507/726638 (2019).

Sivasubramanian, R., Sajin, J. B. & Omanakuttan Pillai, G. Effect of ammonia to reduce emission from biodiesel fuelled diesel engine. Int. J. Ambient Energy 43, 661–665. https://doi.org/10.1080/01430750.2019.1663367;CSUBTYPE:STRING:SPECIAL;PAGE:STRING:ARTICLE/CHAPTER (2022).

Nadimi, E. et al. Effects of using ammonia as a primary fuel on engine performance and emissions in an ammonia/biodiesel dual-fuel CI engine. Int. J. Energy Res. 46, 15347–15361. https://doi.org/10.1002/ER.8235;REQUESTEDJOURNAL:JOURNAL:1099114X;PAGE:STRING:ARTICLE/CHAPTER (2022).

Jayabal, R., Lionus Leo, G. M., Chrispin Das, M., Sekar, S. & Arivazhagan, S. Impact of ammonia energy fraction on improving thermal efficiency and emissions of ammonia/biodiesel in dual fuel diesel engine. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 188, 1398–1410. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PSEP.2024.06.016 (2024).

Pugazhendhi, A., Ali Alharbi, S., Loganathan, K., Subbiah, G. & Nithya, S. Enhancing sustainable fuel solutions: castor oil biodiesel with nanoparticles and ammonia, utilizing as a green substitute for diesel engines. Fuel 368, 131597. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FUEL.2024.131597 (2024).

Seelam, N., Gugulothu, S. K., Reddy, R. V., Bhasker, B. & Kumar Panda, J. Exploration of engine characteristics in a CRDI diesel engine enriched with hydrogen in dual fuel mode using toroidal combustion chamber. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 47, 13157–13167. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJHYDENE.2022.02.056 (2022).

Bora, B. J. & Saha, U. K. Optimisation of injection timing and compression ratio of a Raw biogas powered dual fuel diesel engine. Appl. Therm. Eng. 92, 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APPLTHERMALENG.2015.08.111 (2016).

Barik, D., Murugan, S., Sivaram, N. M., Baburaj, E. & Shanmuga Sundaram, P. Experimental investigation on the behavior of a direct injection diesel engine fueled with Karanja Methyl ester-biogas dual fuel at different injection timings. Energy 118, 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENERGY.2016.12.025 (2017).

Khayum, N., Anbarasu, S. & Murugan, S. Combined effect of fuel injecting timing and nozzle opening pressure of a biogas-biodiesel fuelled diesel engine. Fuel 262, 116505. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FUEL.2019.116505 (2020).

Shanmuganathan, R., Chinnathambi, A., Ali Alharbi, S., Kamarudin, S. K. & Pugazhendhi, A. Nanoadditives for enhanced efficiency and reduced emissions in diesel engines powered by gaseous green ammonia and hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 142, 1113–1119. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJHYDENE.2025.03.265 (2025).

Chen, Y. et al. Effect of ammonia energy ratio and load on combustion and emissions of an ammonia/diesel dual-fuel engine. Energy 302, 131860. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENERGY.2024.131860 (2024).

Hussain, J., Mubarak, M., Boopathi, D. & Jayabal, R. A comprehensive review of production and utilisation of ammonia as potential fuel for compression ignition engines. Next Sustain. 5, 100116. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NXSUST.2025.100116 (2025).

Zaher, M. H. et al. Characterization of soot emissions formed in a compression ignition engine cofired by ammonia and diesel. Fuel 349, 128715. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FUEL.2023.128715 (2023).

Coleman, H. W. & Steele, W. G. Experimentation, validation, and Uncertainty Analysis for Engineers. n.d.

Pv, E. et al. Split injection timing optimization in ammonia/biodiesel powered by RCCI engine. Results Eng. 23, 102607. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RINENG.2024.102607 (2024).

Babu, D. & Anand, R. Biodiesel-diesel-alcohol blend as an alternative fuel for DICI diesel engine. Adv. Biofuels Appl. Technol. Environ. Sustain. 2019:337–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-102791-2.00014-3

Wu, H., Almatrafi, F., Houidi, M., Ben, Fang, T. & Roberts, W. L. A Review on Liquid-Ammonia Injection and Combustion for Engine Applications. Engineering. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENG.2025.09.008

Zhang, Y. et al. A comprehensive review on combustion, performance and emission aspects of higher alcohols and its additive effect on the diesel engine. Fuel 335, 127011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2022.127011 (2023).

Deheri, C., Acharya, S. K., Thatoi, D. N. & Mohanty, A. P. A review on performance of biogas and hydrogen on diesel engine in dual fuel mode. Fuel 260, 116337. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FUEL.2019.116337 (2020).

Enweremadu, C. C. & Rutto, H. L. Combustion, emission and engine performance characteristics of used cooking oil biodiesel—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 14, 2863–2873. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RSER.2010.07.036 (2010).

Wang, S. et al. The environmental potential of hydrogen addition as complementation for diesel and biodiesel: A comprehensive review and perspectives. Fuel 342, 127794. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FUEL.2023.127794 (2023).

Cheng, Q., Muhammad, A., Kaario, O., Ahmad, Z. & Martti, L. Ammonia as a sustainable fuel: review and novel strategies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 207, 114995. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RSER.2024.114995 (2025).

Rudolph, C., Freund, D., Kaczmarek, D. & Atakan, B. Low-calorific ammonia containing off-gas mixture: modelling the conversion in HCCI engines. Combust. Flame. 243, 112063. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COMBUSTFLAME.2022.112063 (2022).

Khayum, N., Shaik, J. H. & Nandakishora, Y. Machine learning and deep learning prediction of in-cylinder pressure and heat release rate in an NH3 – fueled diesel engine. Appl. Therm. Eng. 281, 128684. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APPLTHERMALENG.2025.128684 (2025).

Vijay Kumar, M., Veeresh Babu, A. & Ravi Kumar, P. The impacts on combustion, performance and emissions of biodiesel by using additives in direct injection diesel engine. Alexandria Eng. J. 57, 509–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AEJ.2016.12.016 (2018).

Erdi Gülcan, H., Bayindirli, C., Erol, D. & Çelik, M. Role of different type nanoparticles on exergy, thermoeconomic, exergoeconomic, environmental, and enviroeconomic indicators in a CI engine fueled with rapeseed oil biodiesel. Fuel 384, 134074. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FUEL.2024.134074 (2025).

Gülcan, H. E., Ciniviz, M., Aydın, F., Ünaldı, M. & Uyaroğlu, A. Performance assessment of amyl alcohol and titanium dioxide–dispersed 2-propanol in an SI engine operating at different compression ratios through energy, exergy, environmental, and economic parameters. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 168, 151089. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJHYDENE.2025.151089 (2025).

Özer, S., Gülcan, H. E., Çelebi, S. & Demir, U. Assessment of waste tyre pyrolysis oil and oxy-hydrogen gas usage in a diesel engine in terms of energy, exergy, environmental, and enviroeconomic perspectives. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 143, 862–881. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJHYDENE.2024.11.107 (2025).

Özer, S., Tunçer, E., Demir, U., Gülcan, H. E. & Çelebi, S. Energy, exergy, exergoenvironmental, and exergoenviroeconomic assessment of a two stroke UAV small engine using JP5 aviation fuel and hydroxy (HHO) gas. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 143, 846–861. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJHYDENE.2024.10.394 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through the Large Research Project under grant number RGP2/612/46.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.K. and S.S. conceived and designed the study. Y.N. and J.H.S. performed the experimental investigations and data collection. D.B. and M.S.D. supervised the research, validated the results, and contributed to the interpretation and manuscript refinement. A.D. and S.R. assisted in data analysis, visualization, and preparation of figures. All authors discussed the results, contributed to writing the manuscript, reviewed, and approved the final version for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khayum, N., Suraya, S., Nandakishora, Y. et al. Influence of carbon free gaseous ammonia induction on combustion, performance and emissions in an agricultural diesel engine operated on dual fuel mode. Sci Rep 16, 2572 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32413-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32413-z